-

With the continuous development of the global economy, resource scarcity and energy crises have intensified. Balancing environmental protection with sustainable development has become a critical objective for an increasing number of nations[1,2]. In addition to rapidly advancing clean energy technologies such as wind, hydro, and solar power, bioenergy demonstrates significant potential for future development[3]. Among bioenergy alternatives, biodiesel stands out for its research and industrial relevance, as it can directly substitute conventional diesel in boilers and internal combustion engines without requiring major structural modifications[4]. Biodiesel primarily consists of long-chain fatty acid monoalkyl esters, commonly referred to as fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) or ethyl esters (FAEEs). It is produced via the transesterification of vegetable oils/animal fats with short-chain alcohols (methanol/ethanol) or the esterification of long-chain fatty acids with alcohols. Key advantages include a high cetane number, excellent lubricity, biodegradability, low toxicity, minimal sulfur content, and cleaner combustion emissions. Furthermore, blending biodiesel with petroleum diesel reduces fuel viscosity and density while improving calorific value[5−9].

Although biodiesel's viability as an engine fuel has been extensively validated[10,11], its compositional complexity complicates the numerical analysis of in-cylinder combustion processes and combustion property characterization. A detailed understanding of hydrocarbon oxidation kinetics is essential for developing high-efficiency, low-emission engines that comply with stringent environmental regulations[12,13]. According to prior studies[14], biodiesels derived from diverse feedstocks universally contain four major high-molecular-weight FAMEs that accurately represent their combustion characteristics: methyl palmitate (saturated), methyl stearate, methyl oleate, and methyl linoleate. However, their high carbon numbers (C16–C18) and molecular asymmetry pose significant challenges for deriving precise chemical kinetic mechanisms. Additionally, their low volatility complicates gas-phase autoignition experiments. Consequently, short-chain esters with functional groups are widely adopted as surrogate fuels to mimic the oxidation behavior of practical biodiesel[15−17]. These small-molecule esters enable cost-effective computational studies to determine kinetic parameters while offering favorable vaporization properties for autoignition experiments. Internationally, methyl butyrate (MB) and methyl decanoate (MD) are the most commonly used small-molecule surrogates for biodiesel.

The combustion mechanism of MB was initially developed by Fisher et al.[18] to simulate biodiesel combustion. However, due to its oversimplified molecular structure, MB exhibits negligible reactivity at relatively low temperatures and fails to replicate the negative temperature coefficient (NTC) behavior characteristic of biodiesel, making it an inadequate surrogate for biodiesel characterization[19]. In contrast, MD demonstrates alkane-like reaction paths under low-temperature conditions. Specifically, during the low-temperature heat release phase, MD generates saturated and unsaturated esters—a behavior that aligns closely with biodiesel's intrinsic properties[20−23]. Consequently, MD has been established as a primary surrogate fuel for biodiesel, with extensive experimental and computational studies conducted on its oxidation and pyrolysis mechanisms across diverse flame conditions.

Significant advancements have been made in understanding the oxidation and pyrolysis mechanisms of MD at the international level. For combustion model refinement, Yang et al.[24] addressed the limitations of the Chapman-Enskog method for non-spherical molecules by employing molecular dynamic simulations to determine the binary diffusion coefficients of MD in nitrogen—a critical parameter for flame characterization. Their calculated diffusion coefficients were notably lower than Chapman-Enskog predictions, effectively modulating the slope of predicted extinction strain rates and advancing MD combustion modeling accuracy. In another advancement, Zhao et al.[25] developed a simplification strategy for MD's complex detailed mechanism. By validating the HyChem approach for oxygenated fuel modeling, they proposed a reduced high-temperature combustion mechanism for MD comprising 121 species and 817 reactions. Experimental validation confirmed the model's reliability, providing theoretical support for extending the HyChem framework to compact kinetic models of liquid biofuels, including MD and methyl palmitate. Experimentally, Hotard et al.[26] investigated the temperature-dependent spray ignition delays and derived cetane numbers (DCN) of MD and three other C10 esters under low-temperature combustion conditions (625–820 K, 2.14–4.0 MPa) using a constant-volume spray combustion chamber. Their results ranked the reactivity of the four C10 esters, identifying MD as the most reactive under these conditions and highlighting the significant influence of double-bond positioning on fuel reactivity. Complementing these efforts, Talukder & Lee[27] employed the spherical flame method in a constant-volume combustion chamber to measure the laminar burning velocity (LBV) and Markstein length of MD-air mixtures under atmospheric pressure (403 K) and various high-temperature/high-pressure conditions across typical equivalence ratios (Φ = 0.7–1.5). Shadowgraph imaging was utilized to track the temporal evolution of flame fronts. Their work enriched the combustion dataset for MD and quantified flame stretch effects on flame propagation under varying initial conditions via Markstein length calculations. For MD pyrolysis, Zhai et al.[28] investigated MD's pyrolysis behavior in a flow reactor using synchrotron radiation vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) at 773–1,198 K under different pressures, revealing that decomposition is governed by both unimolecular dissociation and hydrogen abstraction reactions. They identified that C4–C9 unsaturated esters primarily originate from β-C–C/H bond scission of methyl ester radicals, while C5–C5-C9 1-alkenes stem from β-C–C scission of MD radicals. Furthermore, 1-alkene decomposition products (e.g., aC3H5, C2H2) can form benzene and benzyl radicals via radical recombination, elucidating aromatic hydrocarbon formation mechanisms. Herbinet et al.[29] demonstrated in an isothermal and isobaric jet-stirred reactor that MD pyrolysis generates 32 products, including 1-alkenes, terminal double-bond methyl esters, and CO/CO2. Compared to n-dodecane, MD exhibits lower yields and higher stability due to its ester functional group, with unsaturated esters and alkenes competitively formed. Their EXGAS-based kinetic model confirmed that retro-ene reactions dominate alkene/ester consumption but underpredicted CO/CO2 ratios and small ester evolution, necessitating additional molecular reaction pathways for mechanism refinement. Gerasimov et al.[30] acquired laminar premixed MD flame structure data via molecular beam mass spectrometry (MBMS) and GC-MS, coupled with simulations using two detailed reaction mechanisms. Experimental and simulated results showed strong agreement, validating the rationality of primary MD decomposition pathways and the reliability of the pyrolysis reaction network.

It is evident that investigating the combustion characteristics of MD remains a prominent research topic in the bioenergy field. As a fundamental combustion property, LBV is primarily governed by the thermodynamic state of the reactive system, reflecting the net interplay of heat release, diffusivity, and chemical reactivity[31]. LBV serves as a cornerstone parameter for analyzing complex flame phenomena, including turbulent flame propagation, flame instability, flammability limits, flashback, flame quenching, and detonation[32−34]. Furthermore, LBV is critical for validating detailed chemical reaction mechanisms and global reaction models, as well as for calculating key flame parameters[32−34]. For biodiesel engines, LBV data are indispensable for analyzing in-cylinder combustion propagation dynamics. This underscores the necessity of studying the LBV of MD, a key biodiesel surrogate fuel. Quantifying MD's LBV enables optimization of its combustion behavior, thereby reducing engine emissions of soot, particulate matter (PM), and nitrogen oxides (NOx)[35]. Concurrently, LBV characterization supports the development of strategies to enhance combustion stability and dynamic response under high-load conditions, ultimately improving power output[36]. Additionally, combustion property datasets inform biodiesel formulation design and engine control strategy calibration[37], accelerating the adoption of renewable fuels, reducing reliance on fossil energy, and advancing carbon neutrality goals.

This study aims to measure the LBV of MD-air mixtures at atmospheric pressure across varying equivalence ratios using the heat flux method, thereby addressing the absence of experimental LBV data for MD under these conditions. Furthermore, the measured results will be compared with simulations from established kinetic mechanisms to identify deviations, analyze their root causes, and propose potential paths for mechanism refinement.

In this work, the LBV of MD-air premixed flames will be determined using a heat flux burner under the following conditions: atmospheric pressure (1 atm), unburned mixture temperature of 373 K, and equivalence ratios (Φ) ranging from 0.7 to 1.5. A critical experimental challenge lies in ensuring complete fuel vaporization, as incomplete vaporization may induce equivalence ratio fluctuations and compromise measurement accuracy. To mitigate this, we rigorously calculated the saturated vapor pressure of the liquid fuel mixture at operational temperatures and optimized the nitrogen (N2) carrier gas-to-fuel vapor ratio. This ensures that the partial pressure of fuel vapor remains below its saturation threshold, guaranteeing continuous and homogeneous vaporization. Subsequent sections will detail the experimental setup and procedures. Following this, numerical modeling protocols will be outlined, including the application of selected detailed combustion mechanisms to simulate LBV under identical conditions. Comparative analyses between experimental and simulated results will be conducted to identify discrepancies in mechanism predictions. Finally, sensitivity analysis and reaction path diagnostics will be performed to pinpoint critical elementary reactions influencing LBV accuracy, thereby guiding targeted improvements to the kinetic models.

-

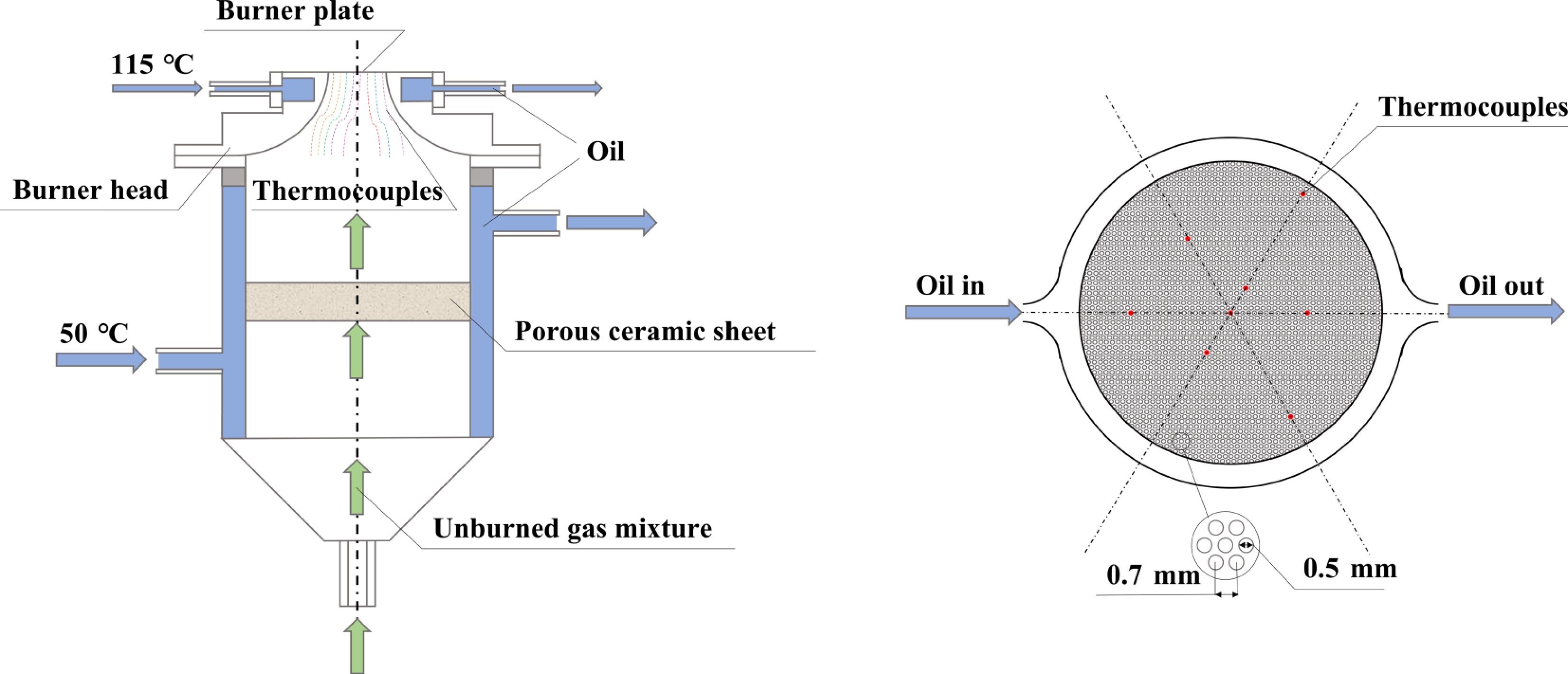

The LBV of premixed MD-air flames was experimentally determined at atmospheric pressure (1 atm) and 373 K using the heat flux method. A schematic of the heat flux burner employed in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. The unburned gas mixture, precisely regulated by Bronkhorst and Alicat mass flow controllers (MFCs)[38,39], was delivered to the premixed combustion chamber of the heat flux burner. The MFCs were interfaced with a computer via dedicated control software developed by the manufacturers, ensuring accurate flow rate calibration and mixture homogeneity.

The heat flux burner used in this study was custom-designed and fabricated in-house, building upon the original design from Lund University[40]. Key modifications include the addition of a compact premixing chamber at the lower section to enhance fuel-air mixture homogeneity and uniformity. Furthermore, the burner interior is filled with porous ceramic material to act as a flashback arrestor, improving operational safety and facilitating maintenance and component replacement, and validation confirms that this design does not compromise the fluid dynamics of the flow within the chamber beneath the burner. The upper section of the burner features a 2 mm-thick perforated copper plate with a hexagonal array of 0.5 mm-diameter holes spaced 0.7 mm apart[41,42]. A stable planar flame is anchored at a fixed height above this plate.

The principles of LBV measurement using the heat flux method and associated uncertainty analyses have been extensively documented in prior studies[42−45]; thus, a comprehensive discussion is omitted here for brevity. However, uncertainties arising from the MFCs require explicit clarification. The selected MFCs exhibit accuracies of ± 0.2% of reading and ± 0.1% of full-scale for liquid fuel and air streams, respectively[38,39]. These uncertainties propagate into equivalence ratio fluctuations, with their contribution to LBV uncertainty quantified by Eq. (1).

$ \Delta S_L^{MFC}=\left(\dfrac{\Delta\dot{m}_A}{\dot{m}_A}+\dfrac{\Delta\dot{m}_F}{\dot{m}_F}\right)\times S_L $ Here,

$ \Delta{\dot{m}}_{A} $ $ \Delta{\dot{m}}_{F} $ -

For numerical modeling, this study employs the Premix-code in Chemkin II software to simulate freely propagating premixed flames. A radiation model was considered and implemented in the calculations to obtain the burning velocity of MD-methanol/air flames. Several studies[45−51] have mentioned MD reaction mechanisms. Ultimately, three kinetic models developed by Sarathy et al.[49], Seshadri et al.[50], and Luo et al.[51]—all widely recognized—were selected. Here, the model established by Sarathy et al.[49] is a detailed mechanism, while the model developed by Seshadri et al.[50] is a simplified skeletal mechanism.

Regarding the selected combustion mechanisms: Sarathy et al.[49] developed an improved detailed chemical kinetic model for MD combustion based on MD's combustion data in a counterflow diffusion flame. This mechanism comprises 648 species and 2,998 reactions and is computationally applicable to one-dimensional flame simulations under equivalence ratios of 0.25–2.0 and pressures ranging from 101 to 1,013 kPa, while maintaining high chemical fidelity. For Seshadri et al.[50], a skeletal mechanism was derived from their original detailed MD mechanism (containing 3,036 species and 8,555 elementary reactions) using the Directed Relation Graph (DRG) method. The reduced skeletal mechanism retains only 125 species and 713 elementary reactions, significantly improving computational efficiency. Experimental validation confirms that the simplified mechanism maintains strong agreement with experimental results. The model proposed by Luo et al.[51] can also be applied to MD combustion simulations. They established a detailed Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) mechanism (3,329 species and 10,806 reactions) for a ternary surrogate mixture of MD, methyl-9-decenoate, and n-heptane, then reduced it to a skeletal mechanism (118 species and 837 reactions) suitable for simulating biodiesel combustion across diverse feedstocks. Comparisons with experimental data[23] under conditions of autoignition and perfectly stirred reactors (PSR) (pressure: 1–100 atm, equivalence ratio: 0.5–2, temperature > 1,000 K) demonstrate that despite a 30-fold reduction in mechanism size, the model accurately predicts both global parameters (e.g., ignition delay and flame speed) and detailed species concentration distributions in high-temperature applications.

-

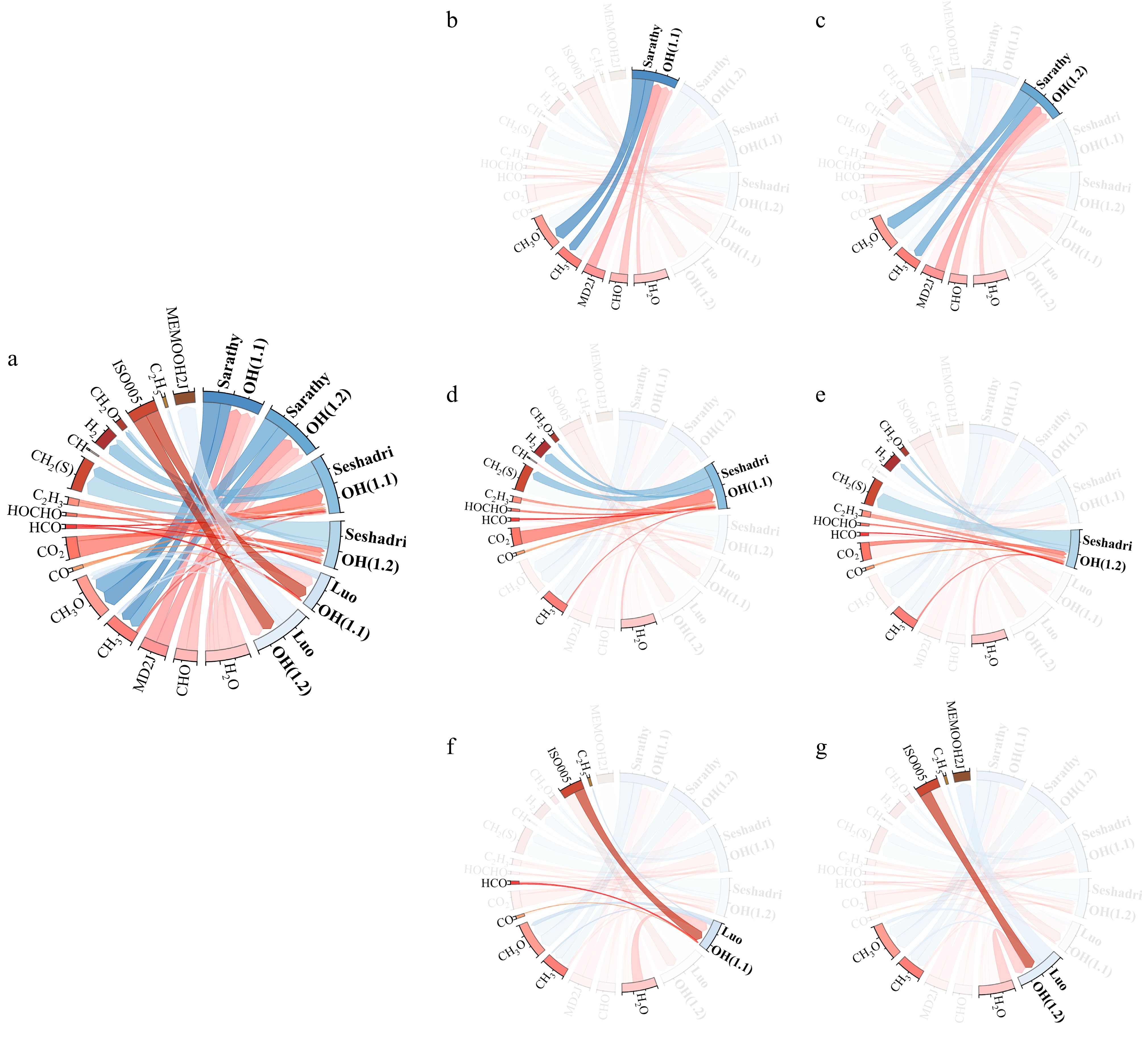

Under the experimental conditions described earlier, the laminar burning velocity (SL) of MD-air mixtures was measured using the heat flux method at an unburned gas temperature of 373 K and atmospheric pressure (1 atm) across equivalence ratios ranging from Φ = 0.7 to 1.5. Based on the methodology outlined above, the uncertainties in both burning velocity and equivalence ratio were quantified. The resulting SL values with associated uncertainties were compared against simulation data in Fig. 2. For the simulated results, uncertainties were not considered, and the values were assumed to be deterministic.

Figure 2.

Comparison of laminar burning velocity (LBV) data for methyl decanoate (MD)-air mixtures at 373 K and 1 atm. Data from Sarathy et al.[49], Seshadri et al.[50], and Luo et al.[51] were obtained using combustion kinetic mechanism models via Chemkin II simulation calculations. Error bars indicate the uncertainties in equivalence ratio and laminar burning velocity within this study.

Figure 2 demonstrates strong agreement between the experimental measurements and published model predictions. Both simulations and experimental data exhibit peak laminar burning velocities (SLmax) at Φ = 1.1. Additionally, error bars for the experimentally determined laminar burning velocities and equivalence ratios are included in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, the laminar burning velocity (SL) data predicted by three selected combustion mechanisms[49−51] are compared with the experimental data obtained in this study. The experimental and simulated data show that all three models agree on the location of the maximum burning velocity (SLmax), which aligns with the experimentally measured data, with SLmax occurring at an equivalence ratio of Φ = 1.1. However, discrepancies exist in the predicted burning velocity magnitudes among the three models and the experimental data. Visually, the results from the mechanism proposed by Sarathy et al.[49] show the best agreement with the experimental SL data. The model by Luo et al.[51] also matches the experimental data reasonably well but slightly underpredicts the values overall, while the mechanism proposed by Seshadri et al.[50] clearly overpredicts the results compared to the other two models and the experimental data. The largest deviations between experiments and simulations are concentrated in the Φ = 1.0–1.3 range. At Φ = 1.1, the laminar burning velocity predicted by the Seshadri et al.[48] model is 61.42 cm/s, whereas the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] models yield 57.86 cm/s and 57.07 cm/s, respectively. Compared to the experimentally measured value of 58.12 cm/s, the predictions from the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] models fall within the experimental uncertainty bounds, while the Seshadri et al.[50] model deviates by approximately 3 cm/s, exceeding the experimental error range. Further analysis reveals that the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism exhibits the largest deviations at Φ = 1.1 and Φ = 1.2, both outside the experimental uncertainty range. At Φ = 1.2, the deviation reaches about 5 cm/s.

It is noteworthy that the Sarathy et al.[49] mechanism (648 species, 2,998 reactions), as a detailed mechanism, naturally achieves higher prediction accuracy for MD burning velocity. In contrast, the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism (125 species, 713 reactions), being a skeletal mechanism, demonstrates reduced fidelity. Surprisingly, the Luo et al.[51] skeletal mechanism (118 species, 837 reactions), despite its simplification, shows better agreement with experimental SL values compared to the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, even though it slightly underpredicts the data. In subsequent sections, the differences between the three models' predictions and experimental data will be analyzed through sensitivity analysis and reaction path diagnostics to elucidate the root causes of these deviations. Additionally, the simplification strategies of the two skeletal mechanisms[50,51] will be comparatively evaluated to propose guidelines for constructing simplified skeletal mechanisms that maximize the fidelity of laminar burning velocity predictions.

Sensitivity analysis and reaction path analysis

-

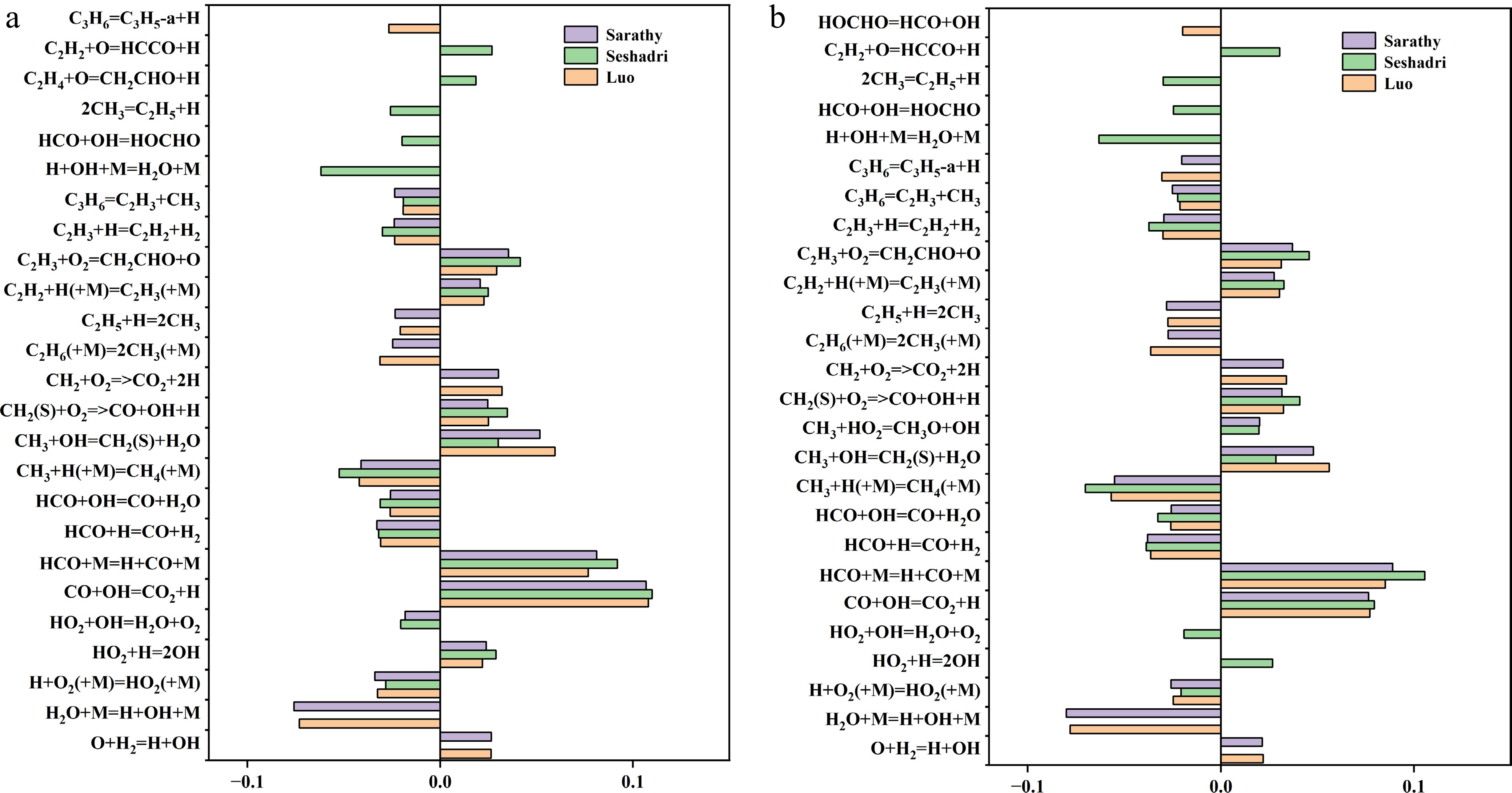

To further analyze the causes of deviations between the experimentally measured LBV of MD-air mixtures under selected conditions and the simulation results from the mechanisms proposed by Sarathy et al.[49], Seshadri et al.[50], and Luo et al.[51], it is essential to first identify the elementary reactions with the greatest influence on LBV predictions. Therefore, sensitivity analysis and reaction path analysis were performed on the three selected mechanisms using Chemkin II. Since the deviations primarily occurred in the Φ = 1.0–1.3 range, with the largest discrepancies observed at Φ = 1.1 and 1.2, the analysis focuses on these two equivalence ratios. Figure 3 displays the top 20 most sensitive reactions for LBV calculations under the selected conditions for the three mechanisms. According to the sensitivity analysis, the reaction H + O2 = O + OH exhibits the highest positive sensitivity across all three mechanisms at both Φ = 1.1 and 1.2. However, differences emerge in the most negatively sensitive reactions: at Φ = 1.1, for the mechanisms proposed by Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51], the most negatively sensitive elementary reaction is H2O + M = H + OH + M, while for the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, it becomes H + OH + M = H2O + M—the reverse of the aforementioned reaction. At Φ = 1.2, the most negatively sensitive reaction remains H2O + M = H + OH + M for the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms but shifts to CH3 + H (+M) = CH4 (+M) for the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism. Notably, at Φ = 1.1, the reaction CH3 + H (+M) = CH4 (+M) also exhibits strong negative sensitivity in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, though it ranks second to H2O + M = H + OH + M in the other two mechanisms. The negative sensitivity magnitude of this reaction in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism is significantly stronger than in the others. At Φ = 1.3, this reaction becomes the most negatively sensitive in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism. Given the substantial LBV prediction errors observed in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, it is concluded that its overestimation of the CH3 + H (+M) = CH4 (+M) reaction leads to abnormally high negative sensitivity, thereby distorting LBV calculations. Additionally, in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, the reaction 2CH3 = C2H5 + H shows strong negative sensitivity at both equivalence ratios and ranks within the top 20 sensitive reactions, whereas it exhibits negligible sensitivity in the Sarathy et al.[50] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the reaction CH3 + OH = CH2 (S) + H2O in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism is significantly lower compared to its prominence in the other two mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis of laminar burning velocity (LBV) for MD-air premixed combustion at 373 K and equivalence ratio (a) Φ = 1.1, and (b) Φ = 1.2. Top 20 most sensitive reactions (with the reaction: H + O2 = O + OH is omitted) identified in the Sarathy et al.[49], Seshadri et al.[50], and Luo et al.[51] combustion mechanisms.

The integrated analysis suggests that the allocation of CH3 radical consumption paths is a critical factor causing deviations in LBV predictions by the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, which aligns with our prior kinetic analysis results for the laminar burning velocity of MD-methanol blended fuels. Beyond the CH3 radical path issue, it is observed that the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism exhibits a significantly higher abundance of OH radical-consuming highly sensitive elementary reactions compared to the other two mechanisms. Examples include HCO + OH = HOCHO, H + OH + M = H2O + M, and HO2 + H = 2OH, which demonstrate stronger sensitivity not observed in the Sarathy et al.[50] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms. Conversely, the primary OH-consuming reactions in the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms, such as CH3 + OH = CH2(S) + H2O, also show negligible sensitivity in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism. Extensive studies have confirmed the critical influence of OH radicals on burning velocity[52−54], implying that differences in OH consumption paths across the three mechanisms may also contribute to MD laminar burning velocity (LBV) prediction discrepancies.

Based on these findings, this study concludes that the allocation of CH3 and OH radical consumption paths plays a vital role in the accuracy of MD kinetic mechanisms for LBV simulations. As methyl decanoate is a key surrogate fuel for biodiesel, the path allocations of these radicals and their associated elementary reactions also significantly impact biodiesel combustion property predictions. Subsequent sections will conduct further reaction path analyses to investigate these effects.

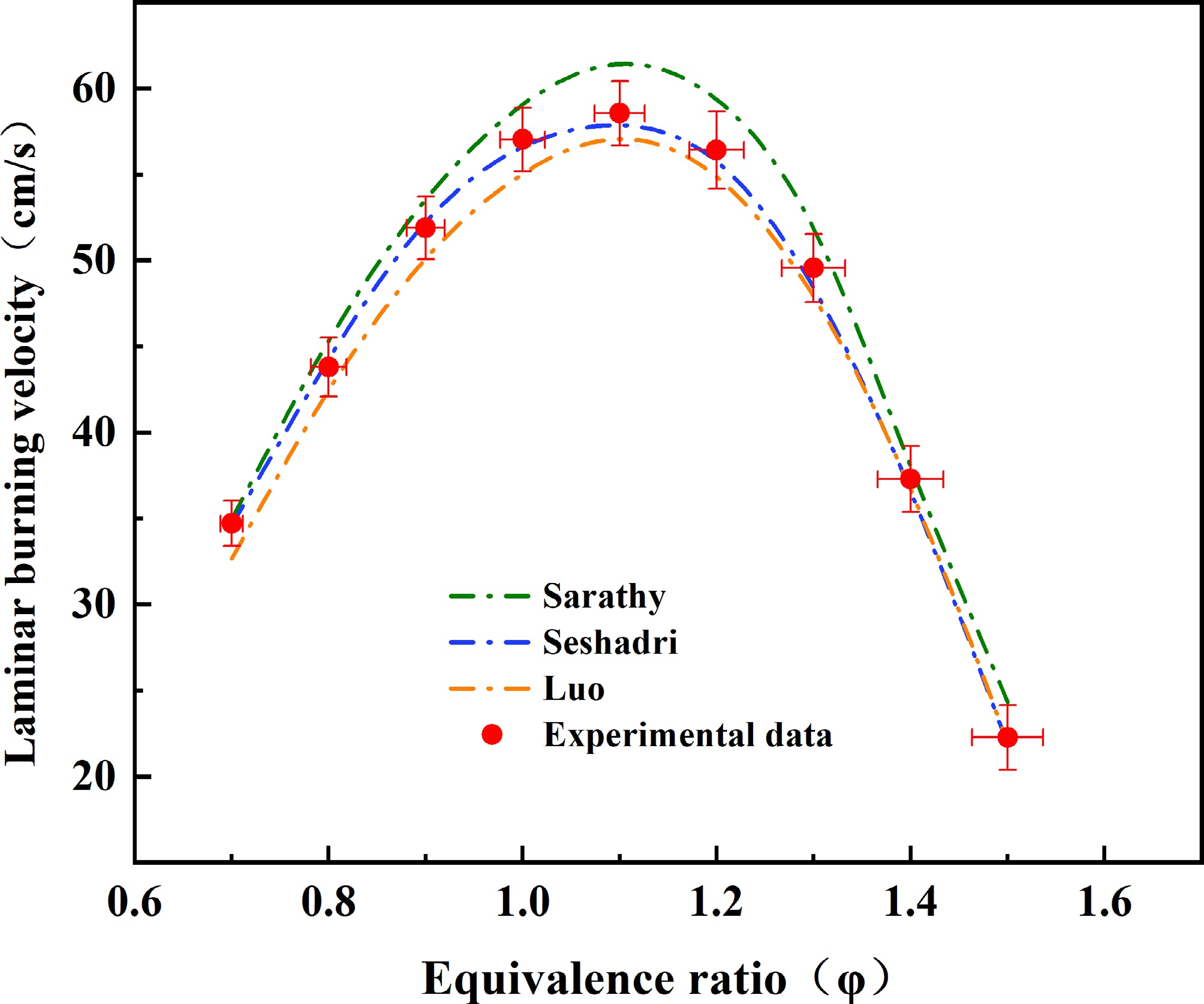

To further analyze the differences in consumption reaction paths of these two radicals across the three mechanisms and their impacts, this study conducted reaction path analyses for the three mechanisms at equivalence ratios Φ = 1.1 and 1.2. The previous sections highlighted that the allocation of CH3 radical consumption paths and the overestimated diversity of OH radical consumption paths are the primary factors affecting the computational predictions of methyl decanoate's laminar burning velocity. Therefore, the analysis here focuses on the consumption reactions of CH3 and OH radicals, with specific emphasis on the reaction paths involving CH3 conversion to CH4. Detailed reaction path analysis procedures and results are presented in the following sections.

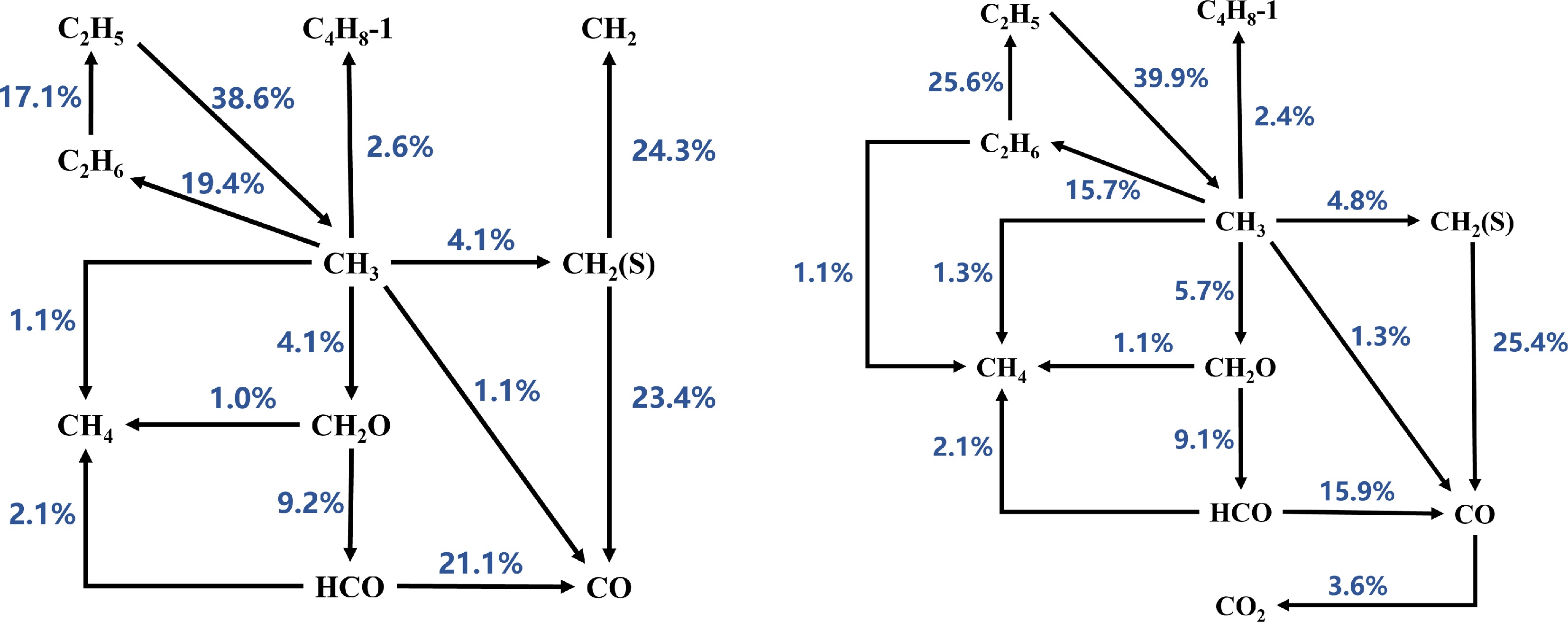

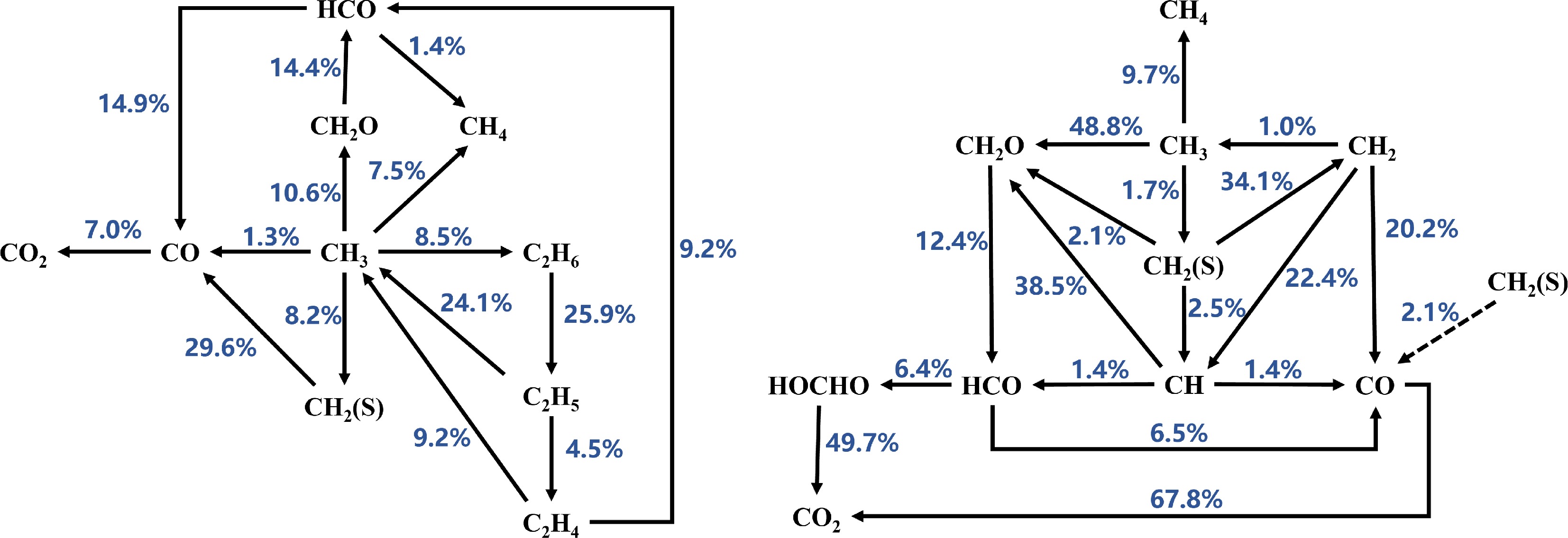

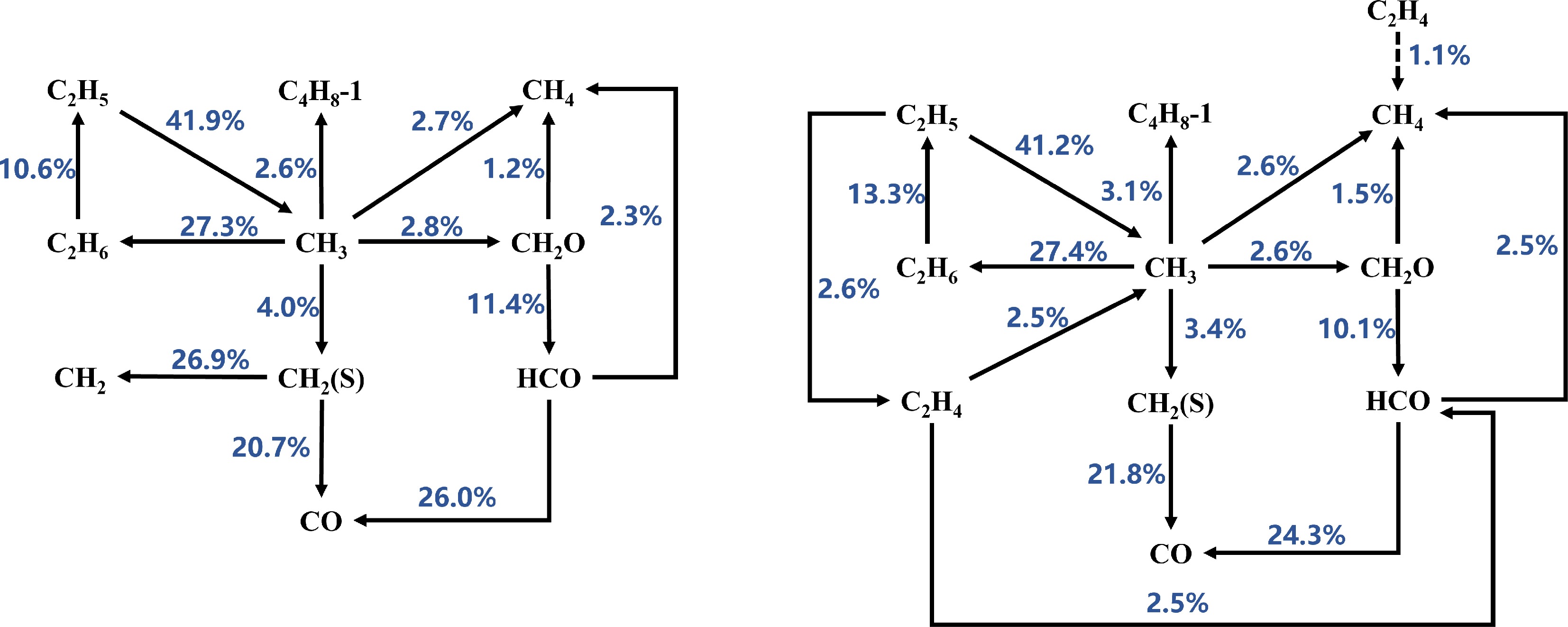

Based on the reaction path analysis results (as shown in Figs 4−6), the consumption paths of CH3 radicals in the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms are largely identical, producing CH4, C4H8-1, C2H6, CH2O, and CH2(S). However, the Sarathy et al.[49] mechanism additionally generates CO from CH3 radicals. In contrast, the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism does not produce C4H8-1 but does generate CO. Furthermore, the branching ratios of CH3 consumption paths in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism differ significantly from those in the other two mechanisms. At Φ = 1.1, the Sarathy et al.[49] mechanism allocates CH3 consumption to CH4 (1.1%), C4H8-1 (2.6%), C2H6 (19.4%), CH2O (4.1%), CH2 (S) (4.1%), and CO (1.1%). The Luo et al.[51] mechanism, which does not produce CO, shows similar path distributions: C4H8-1 (2.7%), C2H6 (27.3%), CH2O (2.8%), and CH2 (S) (4.0%). In contrast, the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism exhibits higher allocations to CH4 (7.5%), C2H6 (8.5%), CH2O (10.6%), CH2 (S) (8.2%), and CO (1.3%). These results indicate that the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism overestimates the contributions of CH4, CH2O, and CH2 (S) formation while underestimating the roles of C4H8-1 and C2H6 in CH3 consumption. This trend is consistent at Φ = 1.2 (see Figs 4−6 for details). Therefore, the mismatched branching ratios of CH3 consumption paths are identified as a critical factor causing the significant deviations in MD laminar burning velocity (LBV) predictions by the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism.

Figure 4.

Reaction path analysis based on laminar burning velocity (LBV) for MD-air combustion at 373 K using the Sarathy et al.[49] combustion mechanism, comparing equivalence ratios (left) Φ = 1.1 and (right) Φ = 1.2.

Figure 5.

Reaction path analysis based on laminar burning velocity (LBV) for MD-air combustion at 373 K using the Seshadri et al.[50] combustion mechanism, comparing equivalence ratios (left) Φ = 1.1 and (right) Φ = 1.2.

Figure 6.

Reaction path analysis based on laminar burning velocity (LBV) for MD-air combustion at 373 K using the Luo et al.[51] combustion mechanism, comparing equivalence ratios (left) Φ = 1.1 and (right) Φ = 1.2.

Divergences in OH radical consumption are also observed across the three mechanisms, primarily manifested in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism, which exhibits more diverse and complex OH consumption paths compared to the Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms. Combined with the sensitivity analysis results from earlier sections, it is evident that the OH radical consumption and generation rates in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism are significantly higher than those in the other two mechanisms. This overestimation of OH radical activity during MD laminar burning velocity (LBV) calculations contributes to the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism's tendency to overpredict LBV values. The OH reaction path analysis is visualized using chord diagrams, where all reactions involving OH consumption and generation across mechanisms and operating conditions are normalized, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7b, c illustrates the paths and proportions of OH radical generation and consumption in the Sarathy et al.[49] mechanism at Φ = 1.1 and 1.2, respectively. Similarly, Fig. 7d– g displays the OH radical dynamics for the Seshadri et al.[50] and Luo et al.[51] mechanisms at Φ = 1.1 and 1.2, with Fig. 7a providing an overview. Figure 7 reveals that the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism involves substantially more OH generation and consumption paths than the other two mechanisms. Coupled with the earlier sensitivity data, the heightened sensitivity of OH-related reactions in the Seshadri et al.[50] mechanism further confirms its overestimated reliance on OH radical dynamics during LBV calculations, underscoring OH's critical role in flame speed predictions.

Furthermore, comparative analysis of the skeletal mechanism construction processes for Seshadri et al.[50] and Luo et al.[51] is conducted to identify the root causes of their differing accuracies in MD LBV predictions.

The analysis reveals that, for the kinetic characteristics of long-chain ester isomers, Luo et al.[51] merged 10 MD radical isomers into a single pseudo-component by leveraging their thermodynamic similarity (e.g., activation energy differences < 5 kJ/mol among RO2 radicals at different positions), reducing species count by 60% while maintaining the integrity of the equivalent reaction network; in contrast, Seshadri et al.[50] relied on conventional DRG threshold screening (ε = 0.2), which eliminated coupled species like HO2-MD adducts but failed to address equivalent reactivity among isomer groups, resulting in cumulative errors in rate parameters when independently treating alkoxy radicals such as C5H11O and C7H15O. Secondly, the Luo et al.[51] mechanism employed DRG-aided global sensitivity analysis (DRGASA) with a three-stage dynamic optimization: Stage 1 targeted T > 1,200 K, focusing on high-temperature ignition core paths like C10H20O2 → C3H6 + CO2; Stage 2 supplemented mid-temperature Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) critical reactions such as RO2 → QOOH chain branching; Stage 3 validated path robustness using high-pressure samples to accurately capture secondary oxidation kinetics of C7H14O2 intermediates. Conversely, Seshadri et al.'s[50] single-stage DRG simplification over-relied on empirical thresholds, discarding competitive paths like the H-abstraction reaction MD + OH → MD-H + H2O, directly impairing OH radical concentration distribution accuracy in laminar flames—a deviation evident in sensitivity analyses during laminar burning velocity calculations. Thirdly, Luo et al.[51] enhanced model generalizability via a multi-dimensional cross-scale validation framework: in 0D reactors, MD ignition delay prediction errors were confined to ± 15% (vs ± 25% for Seshadri et al.[50]); in laminar premixed flame simulations, C1–C4 species concentration profiles correlated with detailed mechanisms at R² = 0.98 (vs 0.91 for Seshadri et al.[50]), achieved by dynamically adjusting reaction rates across 1–100 atm using a 1D conductance model (e.g., CH3O2 isomerization pre-exponential compensation factor α = 0.89–1.12), whereas Seshadri et al.[50] optimized only for specific strain rates (a2 = 50–200 s−1), causing CO oxidation path (CO + OH ⇌ CO2 + H) rate deviations under broad pressure conditions, with errors reaching 32% at high pressures. Additionally, Luo et al.[51] achieved computational efficiency gains through isomer merging and parallel computing: consolidating β-scission, keto-enol tautomerization, and concerted elimination paths of C5H10O2 into equivalent global reactions reduced MD laminar flame simulation time to 0.8 s/iteration (vs 2.3 s for Seshadri et al.[50]), with 40% fewer convergence iterations and 72% matrix dimension compression; meanwhile, Seshadri et al.[50] retained low-impact reactions (e.g., MD + HO2 → MD-OOH, contribution < 0.5%), degrading the Jacobian matrix condition number and numerical stability. In summary, Luo et al.[51] achieved high accuracy and efficiency through isomer kinetic reconstruction, multi-stage dynamic optimization, cross-scale validation, and computational innovation while preserving MD's high-temperature oxidation fundamentals, offering an advanced strategy for simplifying complex mechanisms of biodiesel and its surrogate fuels.

For detailed information, please refer to the Supplementary File 1, which includes: I: a schematic diagram of the experimental system; II: comprehensive data of the measured laminar burning velocity (LBV) for methyl decanoate (MD); III: images of the planar flame stabilized on the burner plate.

-

This study first employs the heat flux method to measure the laminar burning velocity (LBV) of MD-air premixed flames under atmospheric pressure (1 atm), unburned gas temperature of 373 K, and equivalence ratios Φ = 0.7–1.5, addressing the technical challenge of equivalence ratio fluctuations caused by incomplete vaporization of liquid fuel. By precisely regulating the carrier gas (N2)-to-fuel vapor ratio, complete fuel vaporization was ensured, yielding high-precision experimental data. Results show that MD's peak LBV (SLmax = 58.12 cm/s) occurs at Φ = 1.1, consistent with existing model predictions. Comparisons with three combustion mechanisms—Sarathy et al.[49] (detailed), Seshadri et al.[50] (skeletal), and Luo et al.[51] (simplified skeletal)—reveal minor errors (± 1 cm/s) for Sarathy et al.[49] and Luo et al.[51], while Seshadri et al.[50] overpredicts LBV by 3–5 cm/s in the Φ = 1.1–1.3 range. Sensitivity and reaction path analyses identify deviations arising from CH3 and OH radical consumption path allocations. In contrast, Luo et al.'s model[51] enhances prediction accuracy through isomer lumping and multi-stage dynamic optimization, improving fidelity to high-temperature oxidation core paths during mechanism simplification.

This work fills the experimental data gap for MD LBV under selected conditions and systematically compares kinetic models. Findings indicate that while detailed mechanisms offer high accuracy at high computational costs, simplified models with isomer kinetic reconstruction and cross-scale validation achieve a balance between efficiency and precision, advancing biodiesel surrogate fuel mechanism optimization. However, current models face limitations under broad pressure ranges and low-temperature conditions, particularly requiring refinement of secondary oxidation paths for intermediates. Future work should: (1) modify the experimental setup and upgrade the experimental device to obtain LBV data under broader temperature (e.g., 353−443 K) and pressure (e.g., 2, 4, 6 bar) ranges, aiming to further validate the model's robustness; (2) integrate machine learning techniques to streamline mechanism simplification; and (3) investigate synergistic combustion characteristics between MD and other biodiesel components to develop generalized mixed-fuel kinetic models. This study's experimental data and analytical framework establish a critical foundation for advancing biodiesel combustion mechanisms and their engineering applications.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos W2411043 and 52006141).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing - original draft: Fu W; data analysis: Fu W, Feng L; research performed: Fu W (exp and num.), Feng L (exp); research design: Qian Y, Duan X, Lu X; supervision: Qian Y, Duan X, Lu X; writing - review and editing: Qian Y, Duan X, Lu X; writing - manuscript revision: Han X, Feng L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary File 1 Detailed information of system schematic, methyl decanoate LBV data, and planar flame images.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fu W, Qian Y, Han X, Feng L, Duan X, et al. 2025. Laminar burning velocity of methyl decanoate at atmospheric pressure: experimental and reaction kinetics study. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e014 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0014

Laminar burning velocity of methyl decanoate at atmospheric pressure: experimental and reaction kinetics study

- Received: 16 April 2025

- Revised: 30 May 2025

- Accepted: 18 June 2025

- Published online: 25 August 2025

Abstract: As a critical component of renewable fuels, biodiesel combustion research is pivotal for reducing fossil energy dependence, optimizing engine performance, and mitigating emissions. This study focuses on methyl decanoate (MD), a key surrogate fuel for biodiesel. The laminar burning velocity (LBV) of MD-air premixed flames was experimentally measured under atmospheric pressure (1 atm), unburned mixture temperature of 373 K, and equivalence ratios (Φ) ranging from 0.7 to 1.5 using the heat flux method, thereby addressing the lack of experimental data under these conditions. The experimental results reveal that the peak LBV of MD occurs at Φ = 1.1, aligning with model predictions. However, certain skeletal mechanisms exhibit significant overpredictions (up to 12%) in the Φ = 1.1–1.3 range. Through sensitivity analysis and reaction path analysis, the deviations are attributed to inaccuracies in the estimated reaction rates of CH3 and OH radical paths within these mechanisms. Furthermore, we propose that isomer lumping and multi-stage dynamic optimization of high-temperature oxidation paths can enhance the fidelity of simplified kinetic models while preserving LBV prediction accuracy. This study demonstrates that the kinetic behavior of CH3 and OH radicals critically governs LBV prediction precision, providing a targeted direction for refining MD combustion mechanisms. By supplementing experimental data, validating model applicability, and introducing an isomer-resolved mechanism simplification strategy, our findings establish both experimental and theoretical foundations for designing high-efficiency, low-emission biodiesel engines.

-

Key words:

- Biodiesel /

- Laminar burning velocity /

- Methyl decanoate /

- Reaction kinetics