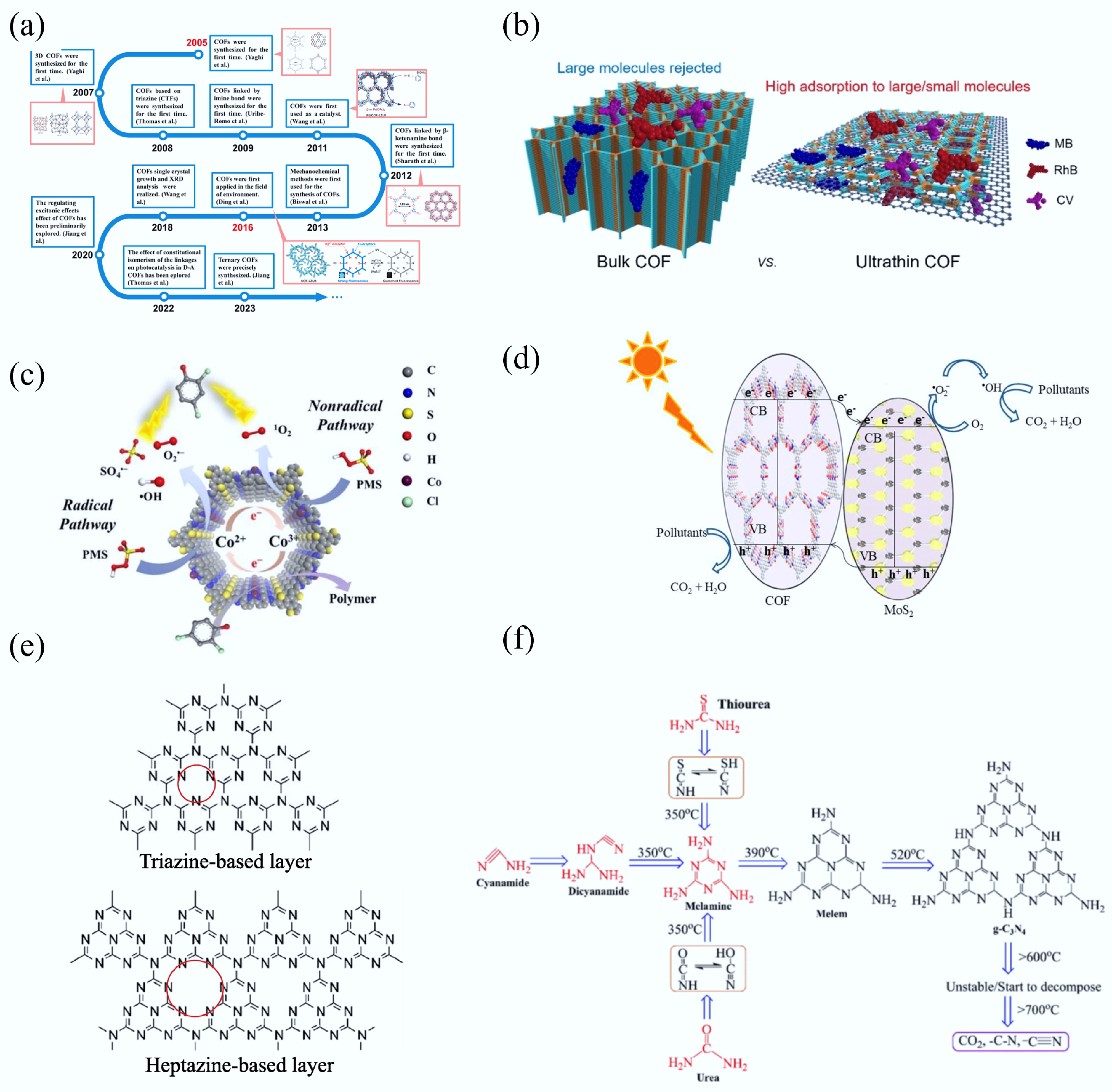

-

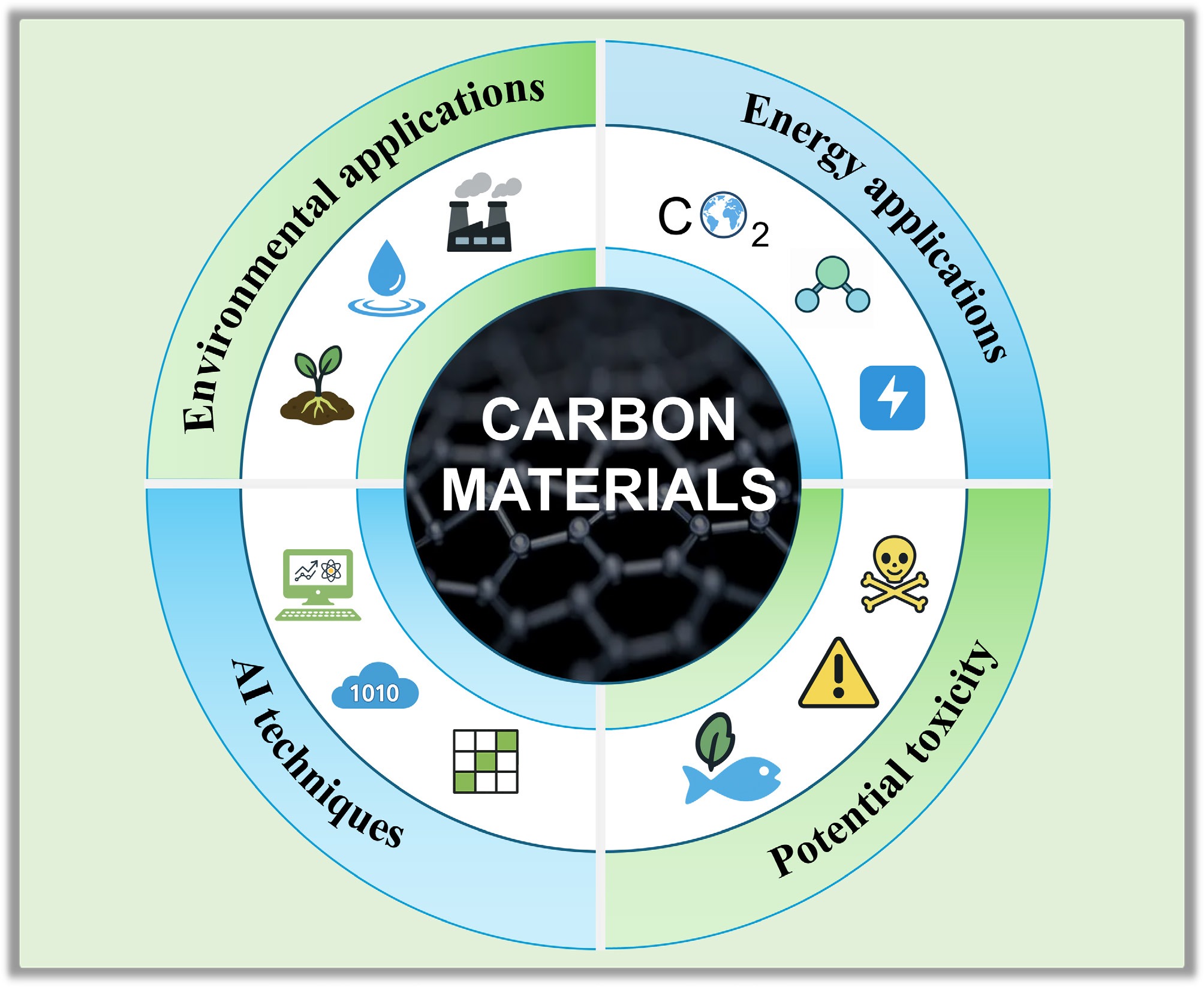

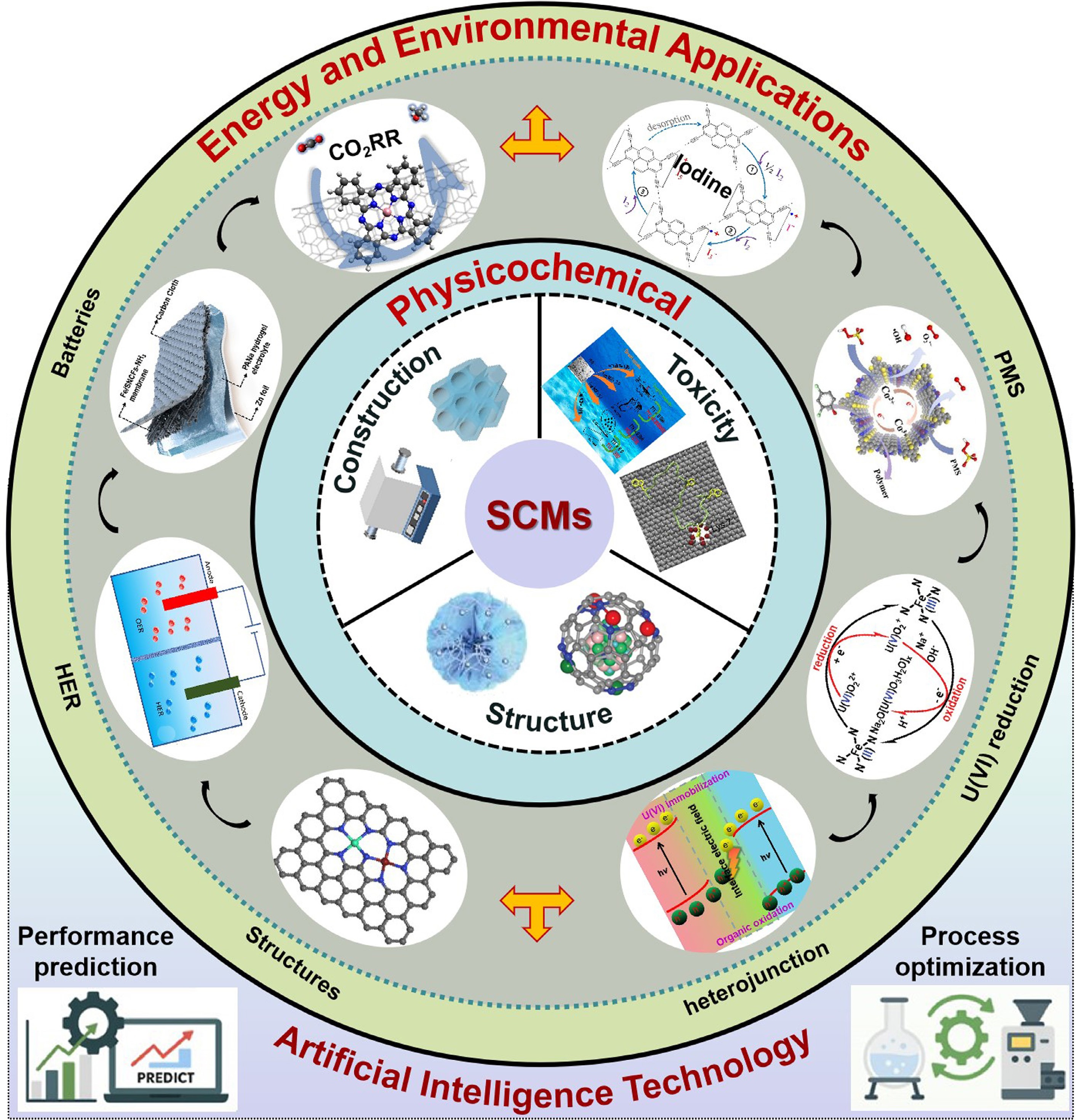

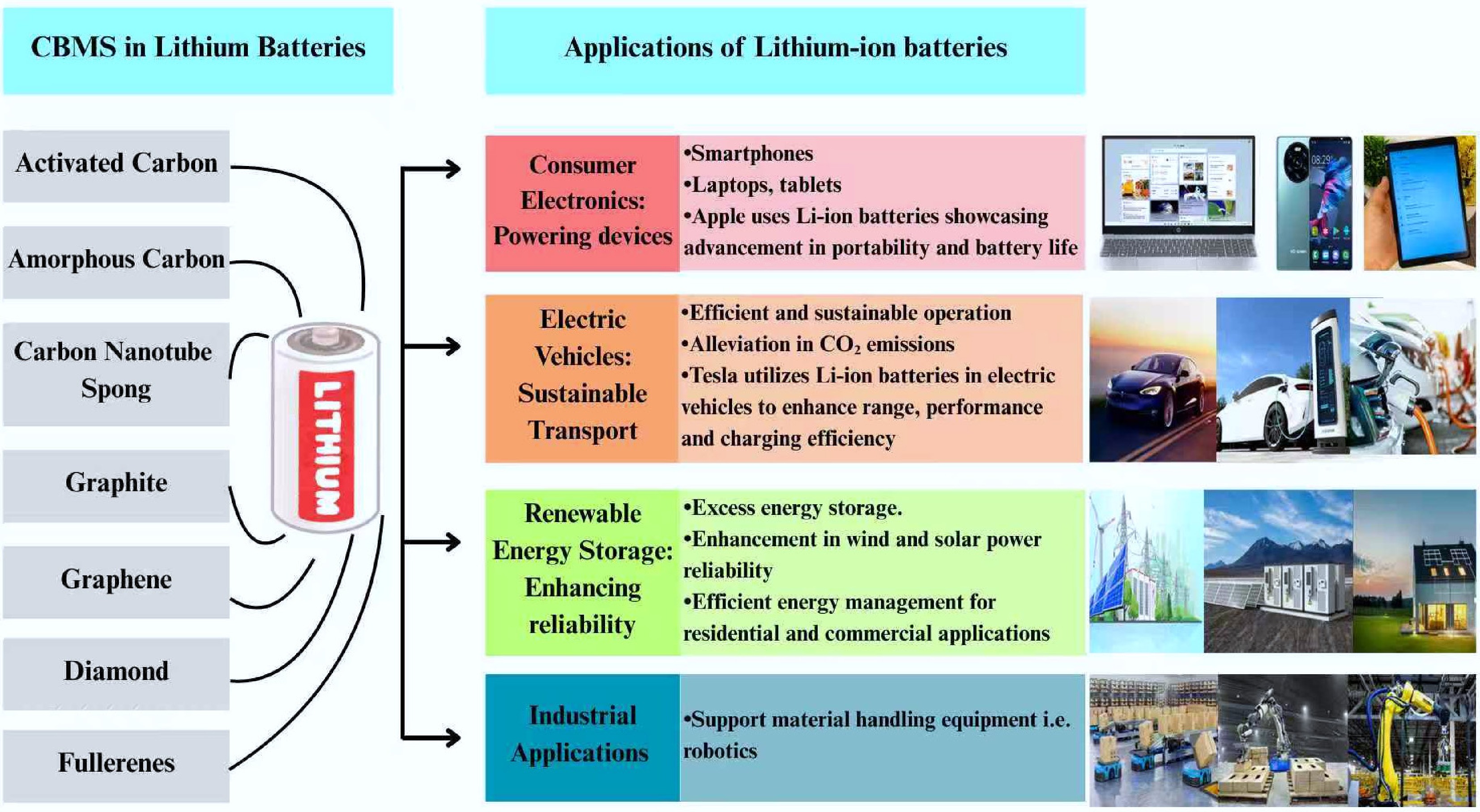

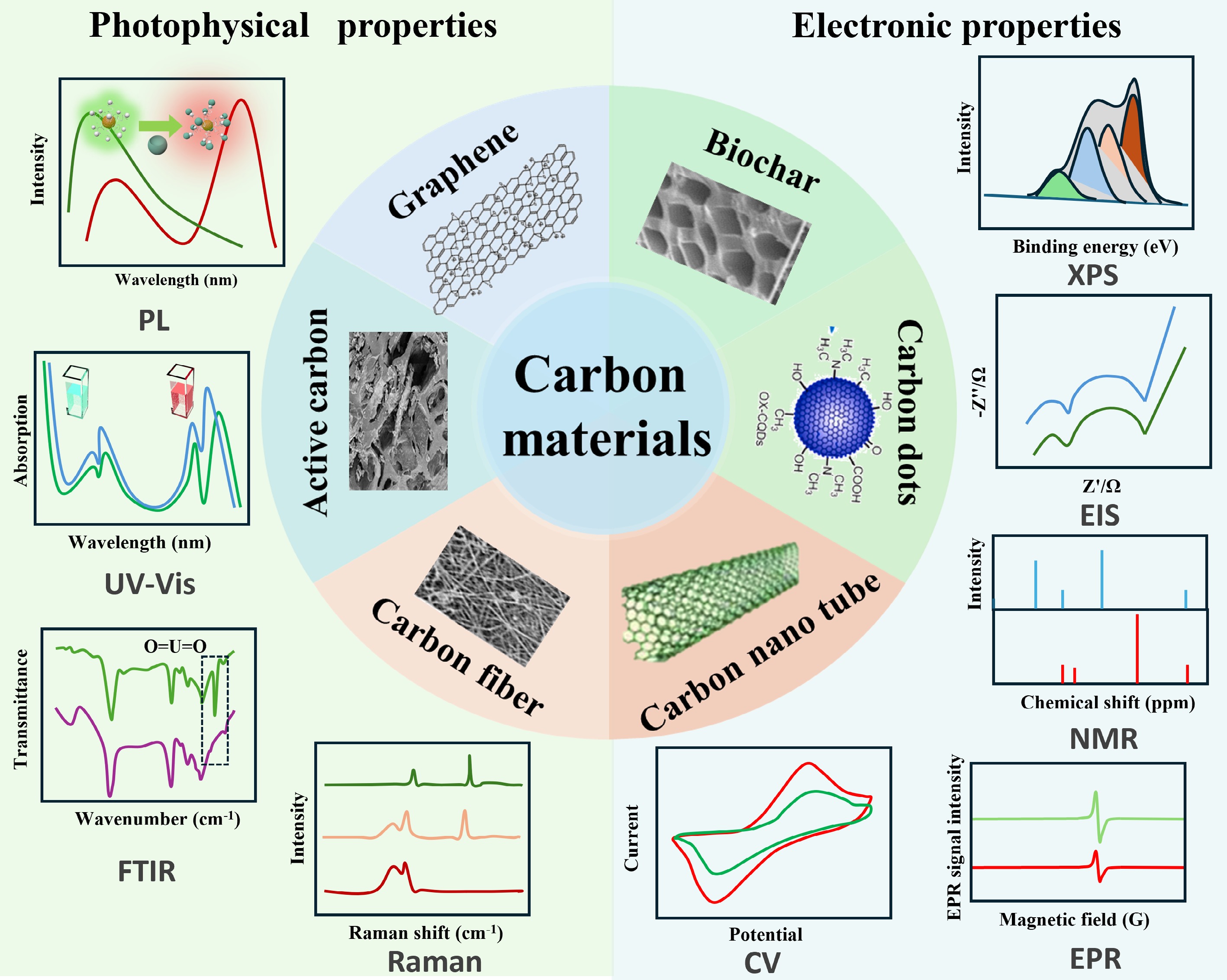

In the era of rapid globalization and industrialization, the world is confronted with unprecedented challenges in the domains of energy and environment. Therefore, the escalating energy demand, coupled with the detrimental effects of environmental pollution, necessitates the exploration of sustainable solutions[1,2]. Among the various alternatives, sustainable carbon materials (SCMs, here referring to carbon materials derived from renewable or waste sources and synthesized through low-energy, low-emission processes), such as zero-dimensional (0D) fullerenes, one-dimensional (1D) carbon nanotubes (CNTs), two-dimensional (2D) graphene, and three-dimensional (3D) activated carbon (AC) and carbon aerogels (CAs), have emerged as promising candidates due to their exceptional physicochemical attributes and multifaceted applications in environmental remediation and energy conversion systems[3−7].

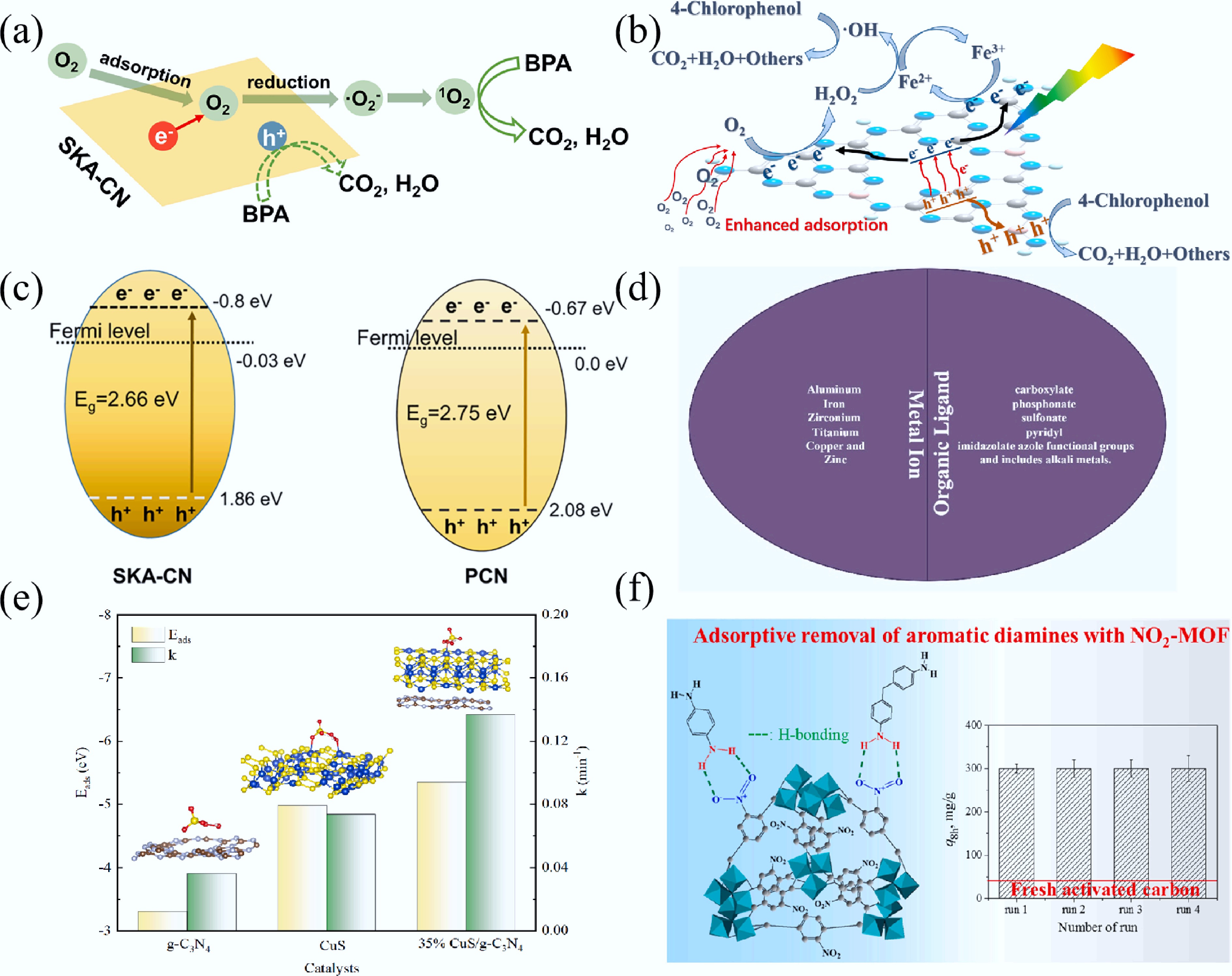

In the context of environmental pollution, organic pollutants, metal ions, and radionuclides pose severe threats to ecosystems and human health[8−12]. However, SCMs can effectively capture and eliminate pollutants in water or air through mechanisms such as physical adsorption, chemical sorption, chemical reduction, chemical complexation, etc., providing a practical and feasible solution. For instance, AC has long been utilized for water purification, while graphene-based materials have shown great potential in removing heavy metal ions and organic pollutants with high efficiency[13−15]. The ability to tailor the surface chemistry and pore structure of SCMs allows for the development of highly selective and efficient adsorbents, which can significantly improve the effectiveness of environmental remediation processes[16−18].

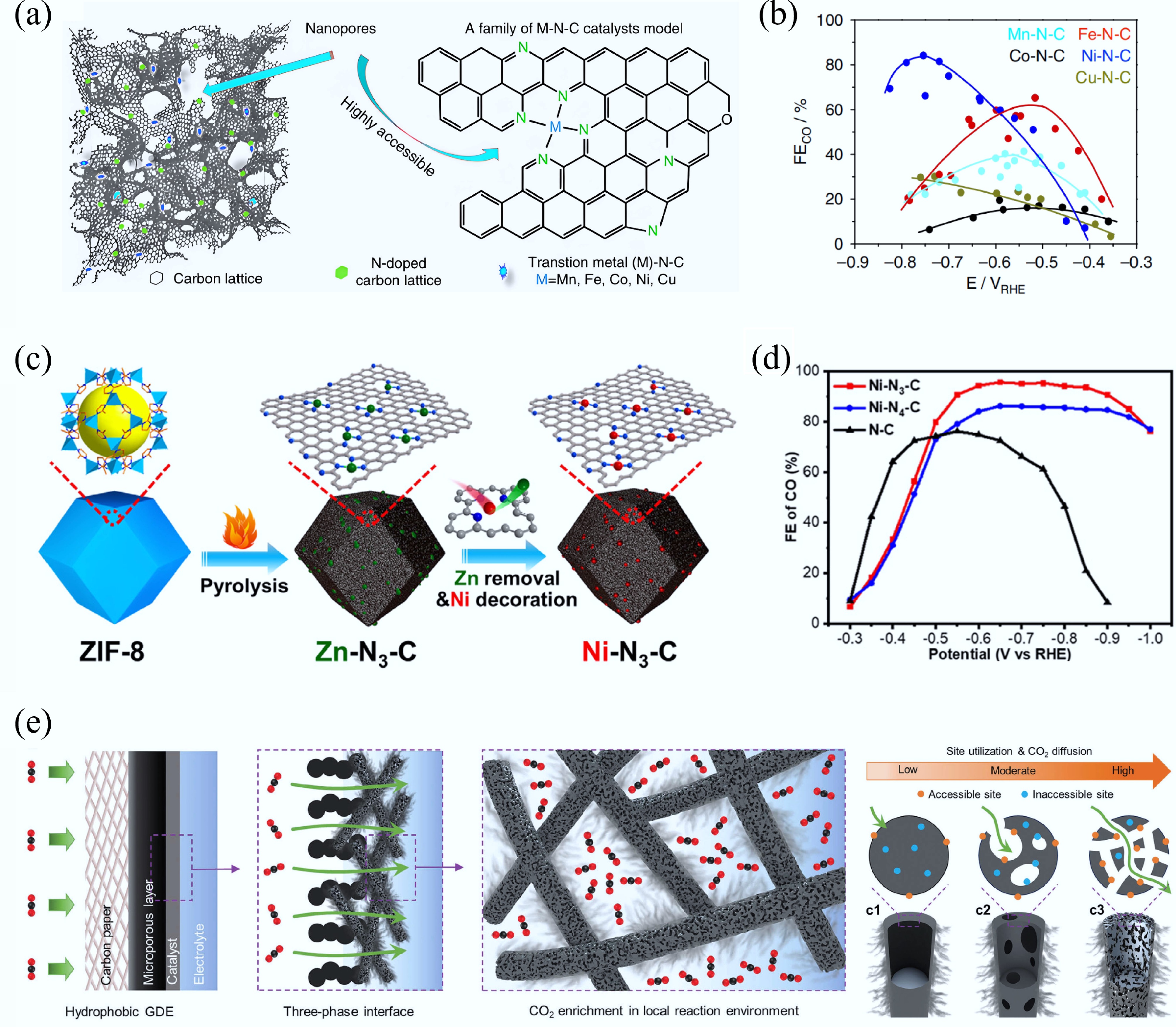

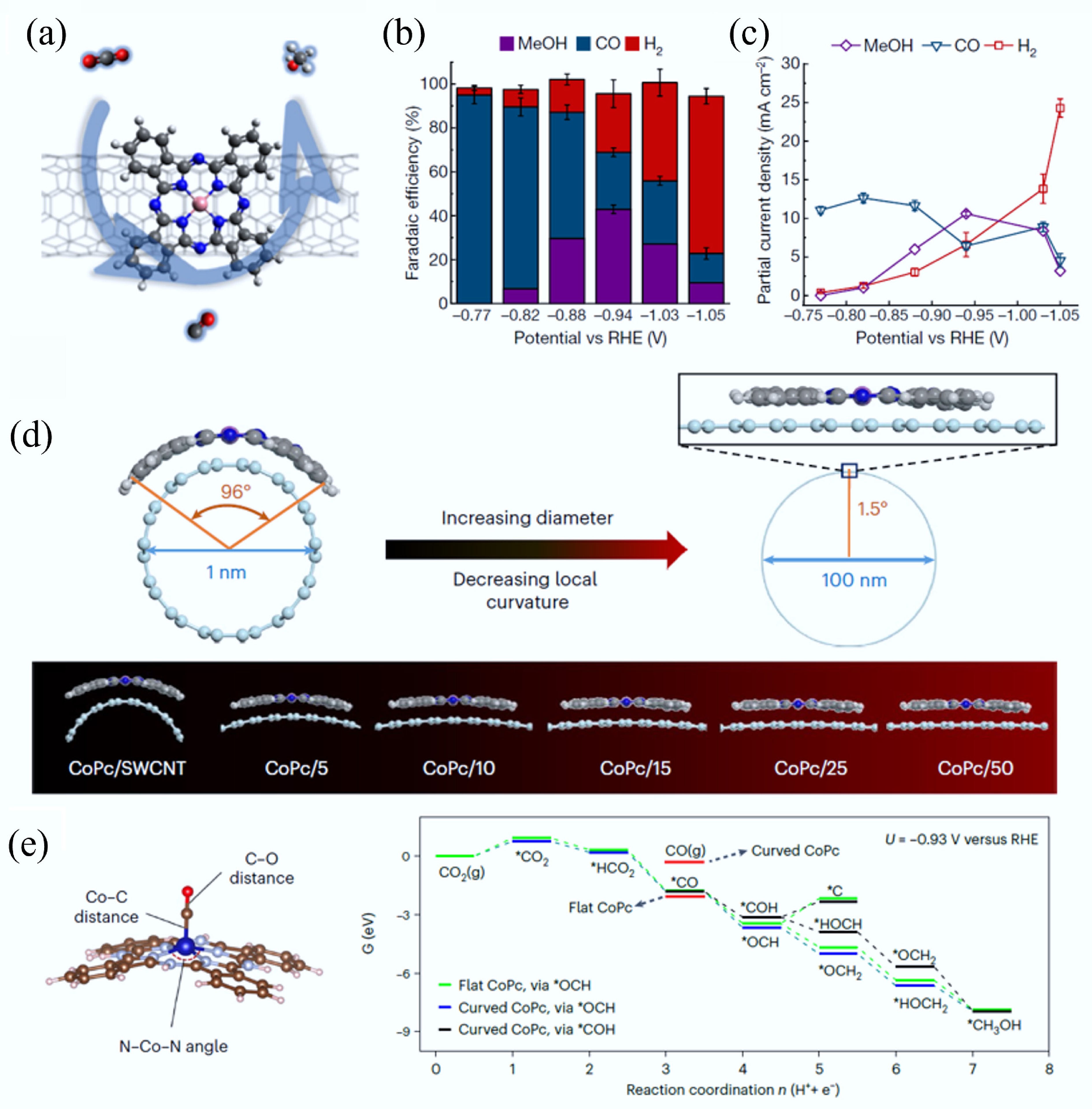

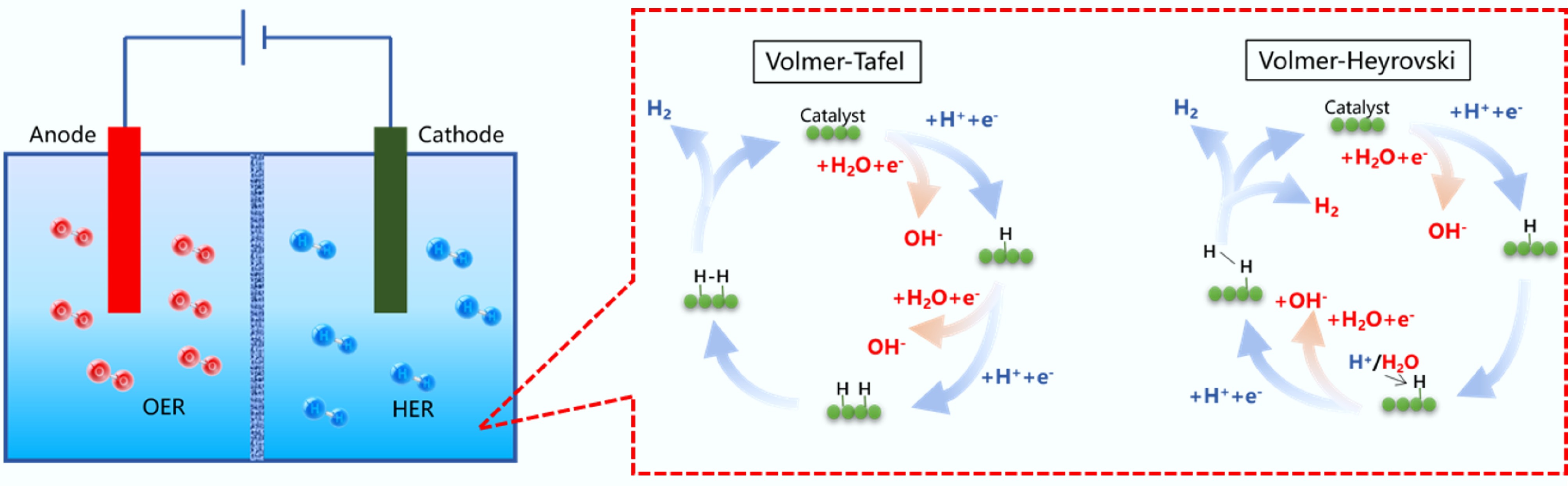

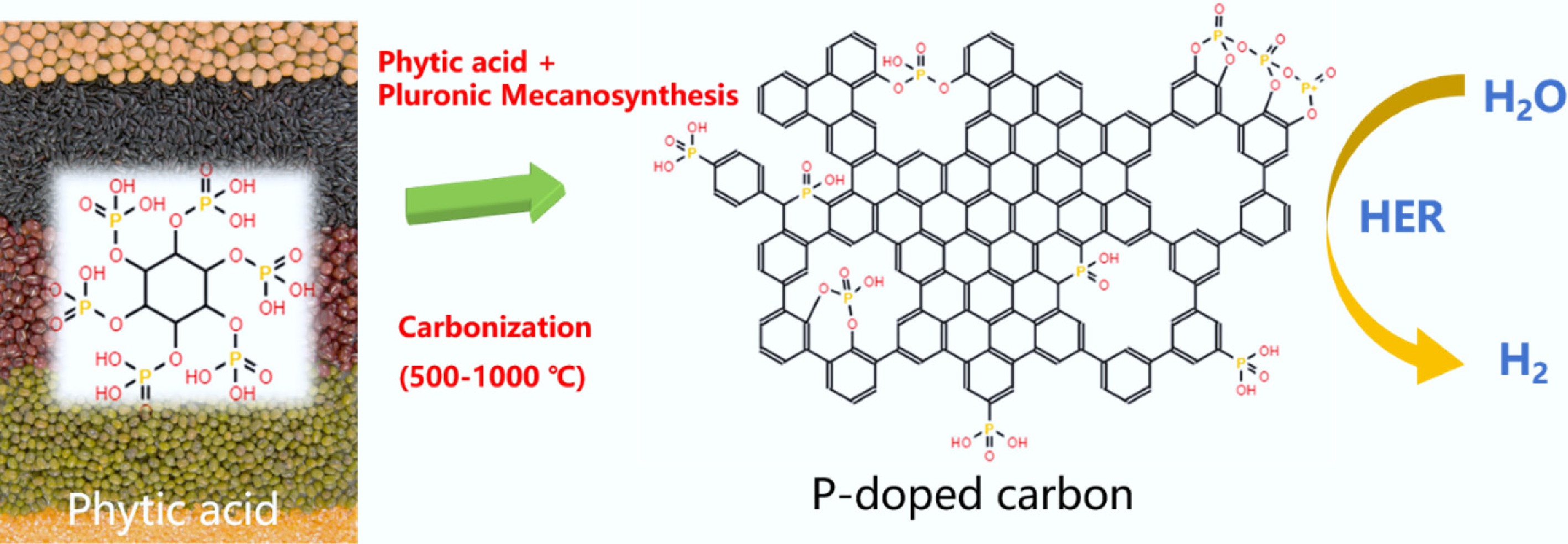

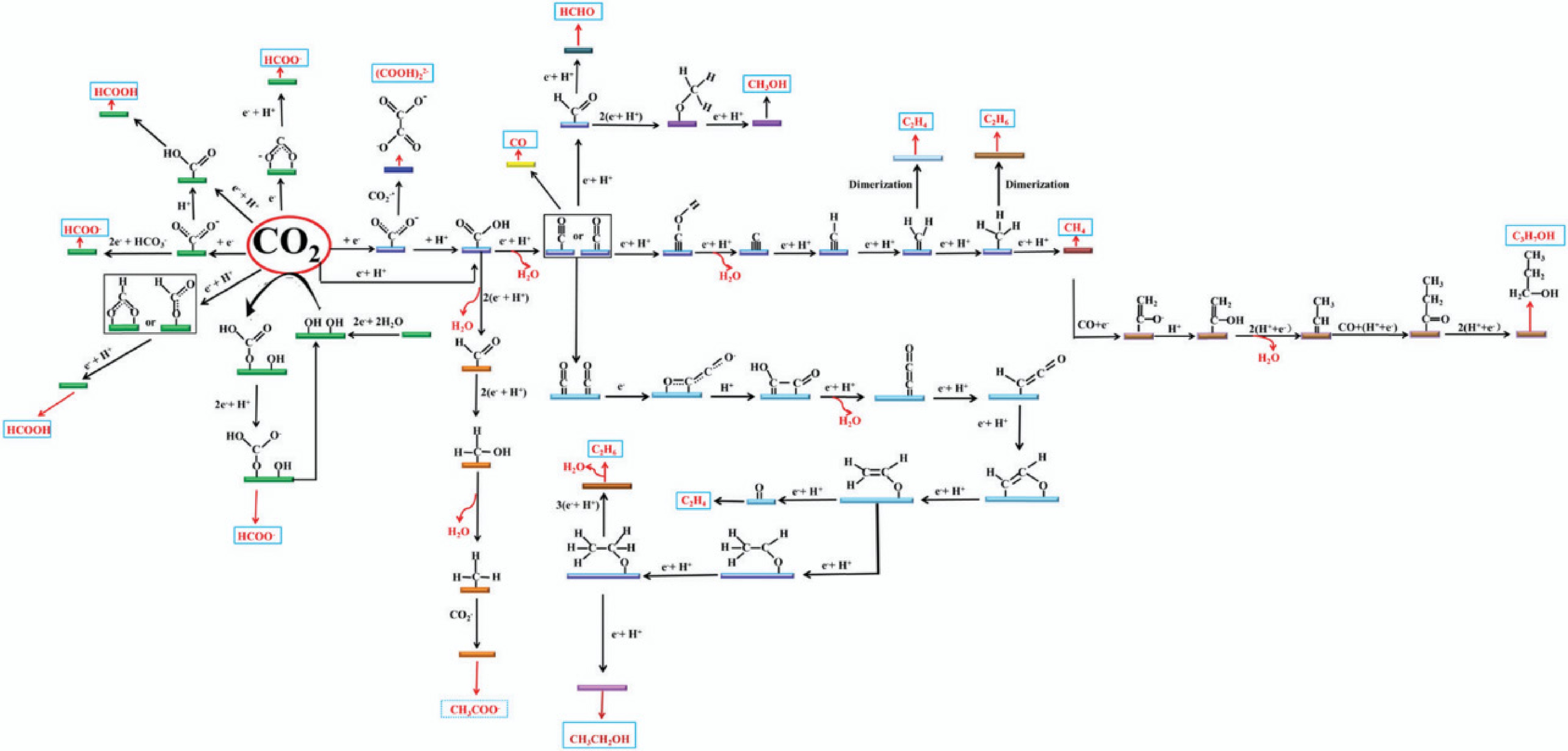

In the energy sector, the transition towards clean and renewable energy sources is imperative to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and mitigate climate change. SCMs play a crucial role in this transition, particularly in the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR), where SCMs serve as catalysts to convert carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, into valuable chemicals and fuels such as methane, methanol, and syngas[19−21]. This not only helps reduce the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere but also provides a sustainable pathway for energy production. Moreover, oxygen evolution reaction (OER), and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) are key processes in water electrolysis for hydrogen production and in metal-air batteries. Accordingly, carbon-based electrocatalysts, with their low cost, high activity, and stability, have become attractive alternatives to precious metal catalysts, thereby driving the advancement of these energy technologies[22−24].

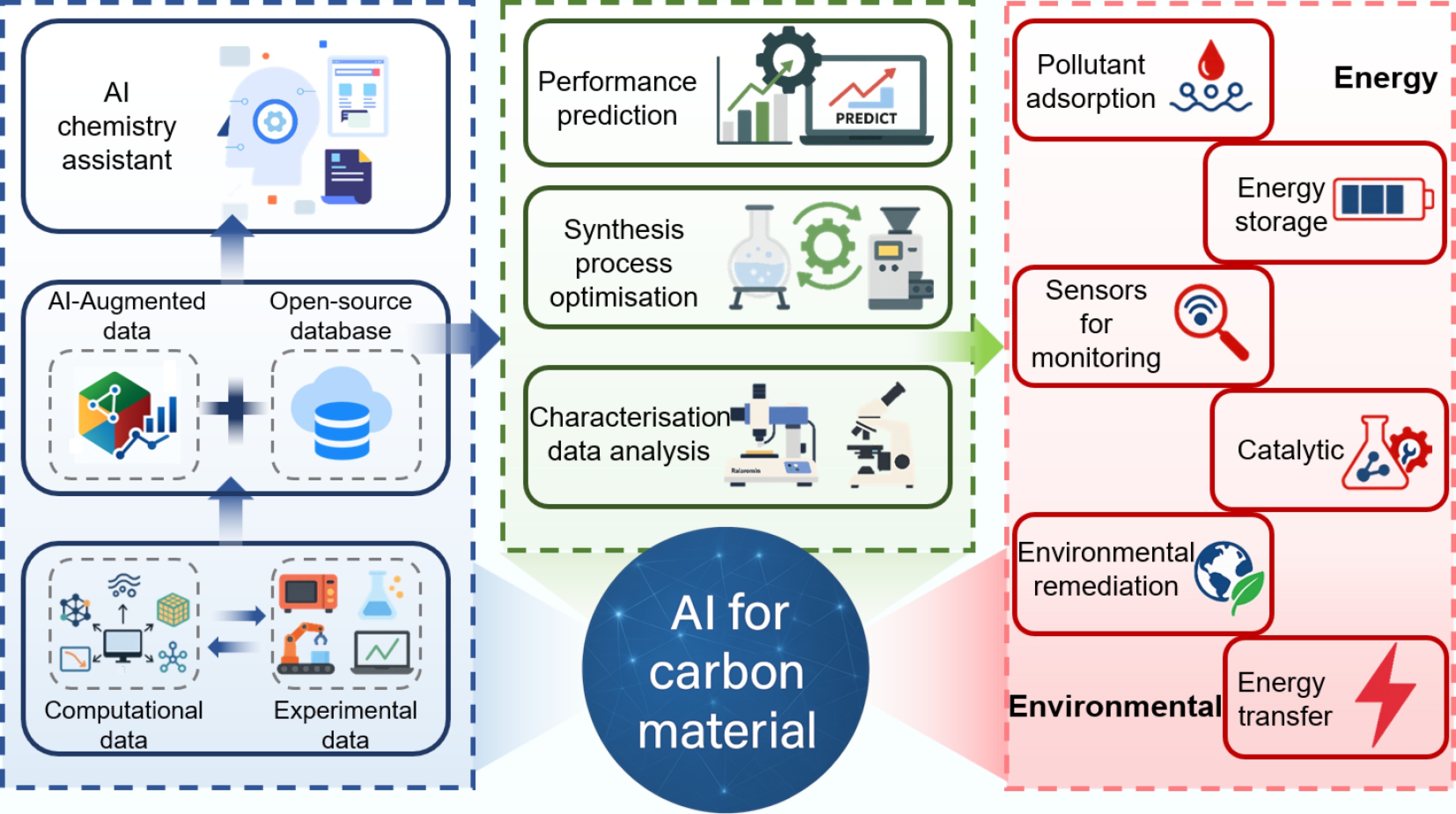

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques with carbon material research has opened new avenues for the design, synthesis, and optimization of SCMs. AI algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data to predict the structure-property relationships of SCMs, guide experimental research directions, and accelerate the discovery of novel materials with tailored properties[25−27]. This synergistic approach of combining AI with materials science can significantly enhance the development of SCMs for energy and environmental applications[28].

In this context, SCMs hold immense promise for addressing the pressing challenges in the energy and environmental fields. Their unique properties, coupled with the potential of AI technologies, make them key players in the pursuit of sustainable development. As shown in Fig. 1, this work aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the construction, toxicity, and detection, as well as the structure and application of SCMs in environmental pollution control and energy conversion, and it also explores the role of AI in advancing the field of SCMs, highlighting the current state of research, challenges, and future perspectives. By delving into these aspects, it is believed that this review seeks to contribute to the ongoing efforts towards the development and implementation of SCMs for a greener and more sustainable future.

-

Carbon materials (CMs) can be classified into 0D carbon (nanometer-sized fullerenes and carbon quantum dots [CQDs], etc.), 1D carbon (CNTs, carbon nanofibers [CNFs], etc.), 2D carbon (graphene, graphdiyne, etc.), and 3D carbon. Correspondingly, various classical strategies have been utilized for synthesizing CMs, mainly including bottom-up and top-down approaches. Bottom-up synthesis constructs CMs atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule from precursors (e.g., hydrocarbons) to achieve precise atomic control, mainly including carbonization (or pyrolysis), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), the templating methods, etc. Top-down synthesis refers to deconstructing bulk carbon sources (e.g., graphite, biomass) into smaller nanostructures to introduce defects, pores, or reduce size, mainly involving exfoliation and etching. Besides, some newly green synthetic technologies have also emerged in the synthesis of CMs very recently, such as biomass-based hydrothermal carbonization, CO2 utilization, Flash Joule heating (FJH), and so on. Each synthesis method exhibits advantages and limitations in fabricating CMs across dimensionalities (Table 1). In this section, the principles of various synthesis strategies for CMs and cutting-edge advances since 2021 are systematically introduced, followed by structural engineering strategies (e.g., pore, heteroatom doping) to enhance their performance in energy storage (e.g., CO2RR, OER, HER, etc.) and environmental remediation (e.g., pollutant removal).

Table 1. Comparison of various synthesis strategies for CMs

Methods Year developed Advantages Limitations Products Refs. Carbonization (pyrolysis) 1980s Low cost, scalable, tunable porosity via precursors (e.g., biomass, polymers) High energy input (> 600 °C), Limited crystallinity (ID/IG > 1.5), amorphous morphology AC, biochar, carbon NPs, carbon foam [42,729] Hard templating 1990s Precise pore size control (2–50 nm), ordered architectures, high surface area Toxic template removal (HF/NaOH), low yield, high cost Ordered mesoporous carbon, CNTs, 3D carbon frameworks, CAs [489,730] Soft templating 1990s Template-free, self-assembly, tunable mesopores (2–10 nm) Poor thermal stability (< 400 °C), surfactant residue contamination Mesoporous carbon spheres, CNFs [731,732] CVD 1960s

(modern: 2004)High crystallinity (ID/IG < 0.1), atomic-level thickness control High cost, slow growth rate, substrate limitations Graphene, CNTs, carbon fibers (CFs), fullerenes, graphdiyne [53,733] Mechanical exfoliation 2004 Simple (e.g., Scotch tape), minimal chemical defects, preserves intrinsic properties Low yield (< 5%), non-uniform flake sizes, labor-intensive Graphene nanosheets, few-layer graphdiyne [734] Chemical exfoliation 2008 High yield, solution-processable, scalable Defect generation (ID/IG >1.0), requires harsh oxidants (H2SO4/KMnO4), residual functional groups Graphene oxide, CQDs [735] Electrochemical exfoliation 2012 Mild conditions (room temp), tunable surface groups, high purity (> 95%) Limited to conductive precursors, low throughput, solvent dependency Few-layer graphene, fluorinated CNTs [62,736] Chemical etching 2010 Defect engineering (edge sites), hierarchical porosity, enhanced surface reactivity Over-etching risks, corrosive reagents (HNO3/KOH) Holey graphene, porous CNFs [63,65] Physical etching 2015 No chemical waste, plasma/ion beam precision (nm-scale), high reproducibility High equipment cost, slow processing, limited to thin films Patterned graphene, nanoperforated carbon membranes [66,737] HTC 2001 Eco-friendly (aqueous, < 200 °C), spherical morphology control Low graphitization (ID/IG > 1.5), limited surface area (< 500 m²/g) Carbon microspheres, hydrochar from biomass, CQDs [68,69] CO2 utilization 2015 Carbon-negative process, converts waste CO2 Energy-intensive (600–1,000 °C), low efficiency (< 30% conversion) CNTs, graphene, fullerenes, PC [70] FJH 2019 Ultrafast (< 1 s), energy-efficient (~0.1 kWh/kg), upcycles waste precursors Limited to conductive precursors, non-uniform heating in bulk samples Turbostratic graphene, 3D PC, CQDs [64] Synthesis strategies

Bottom-up synthesis

Carbonization (or pyrolysis)

-

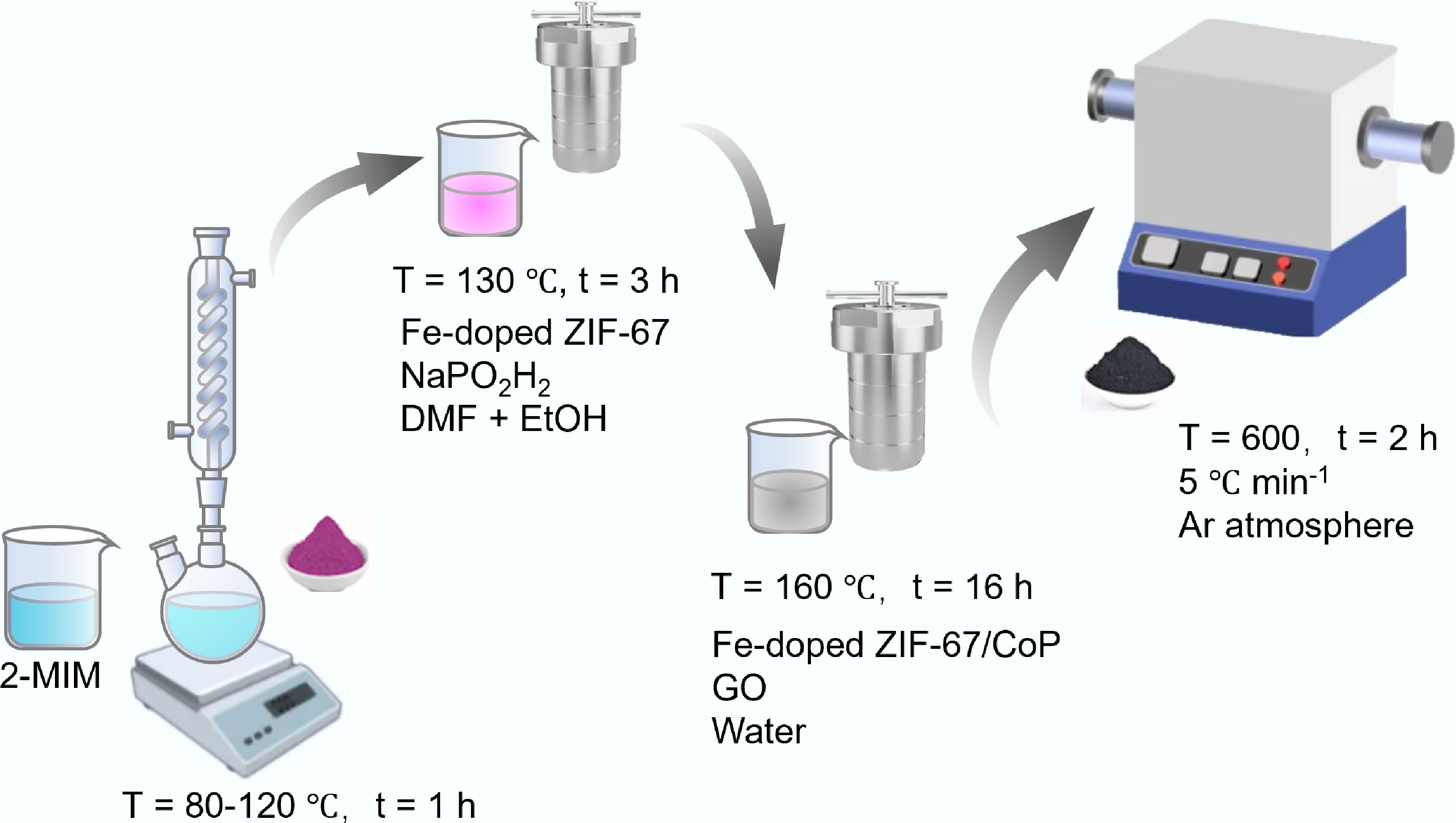

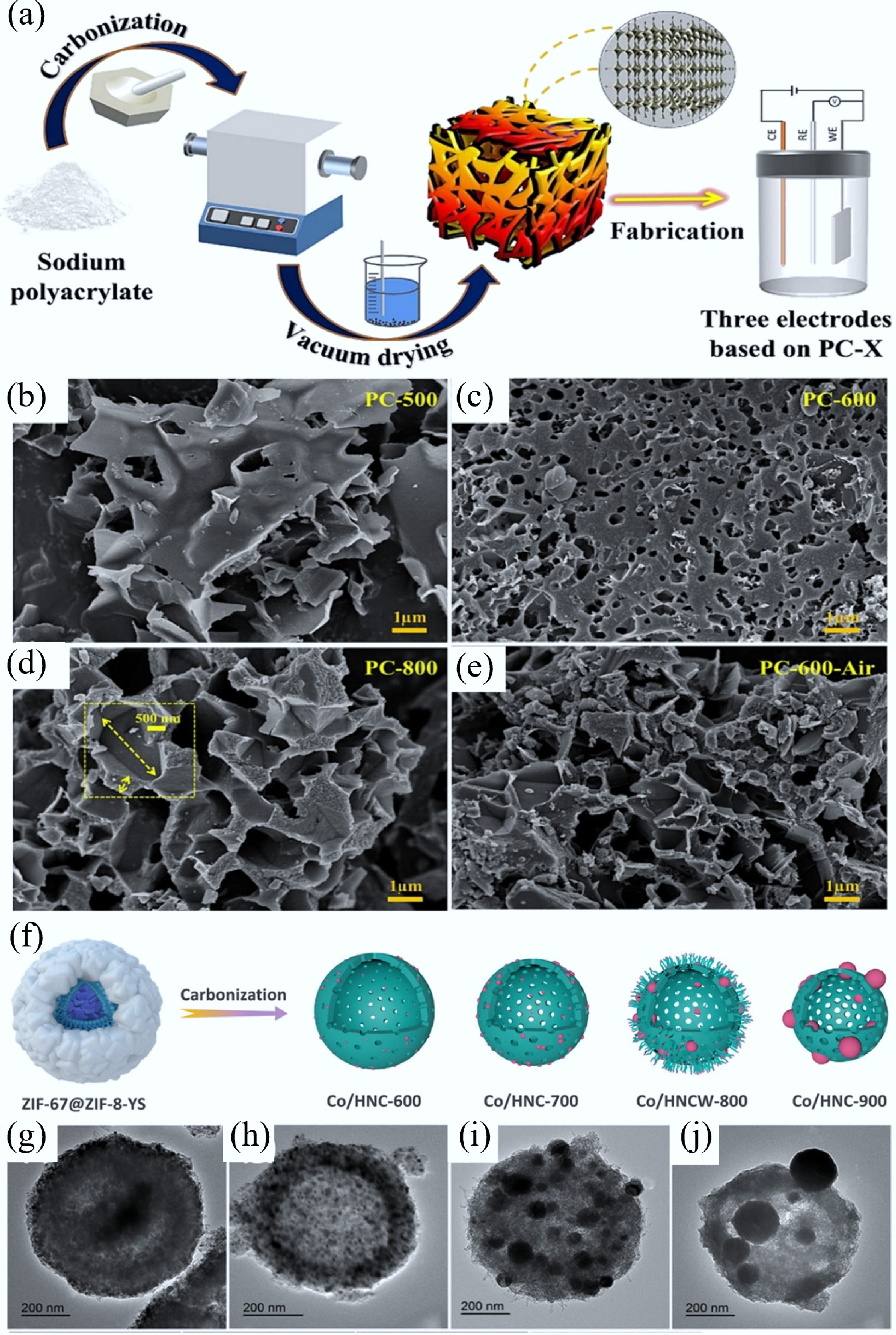

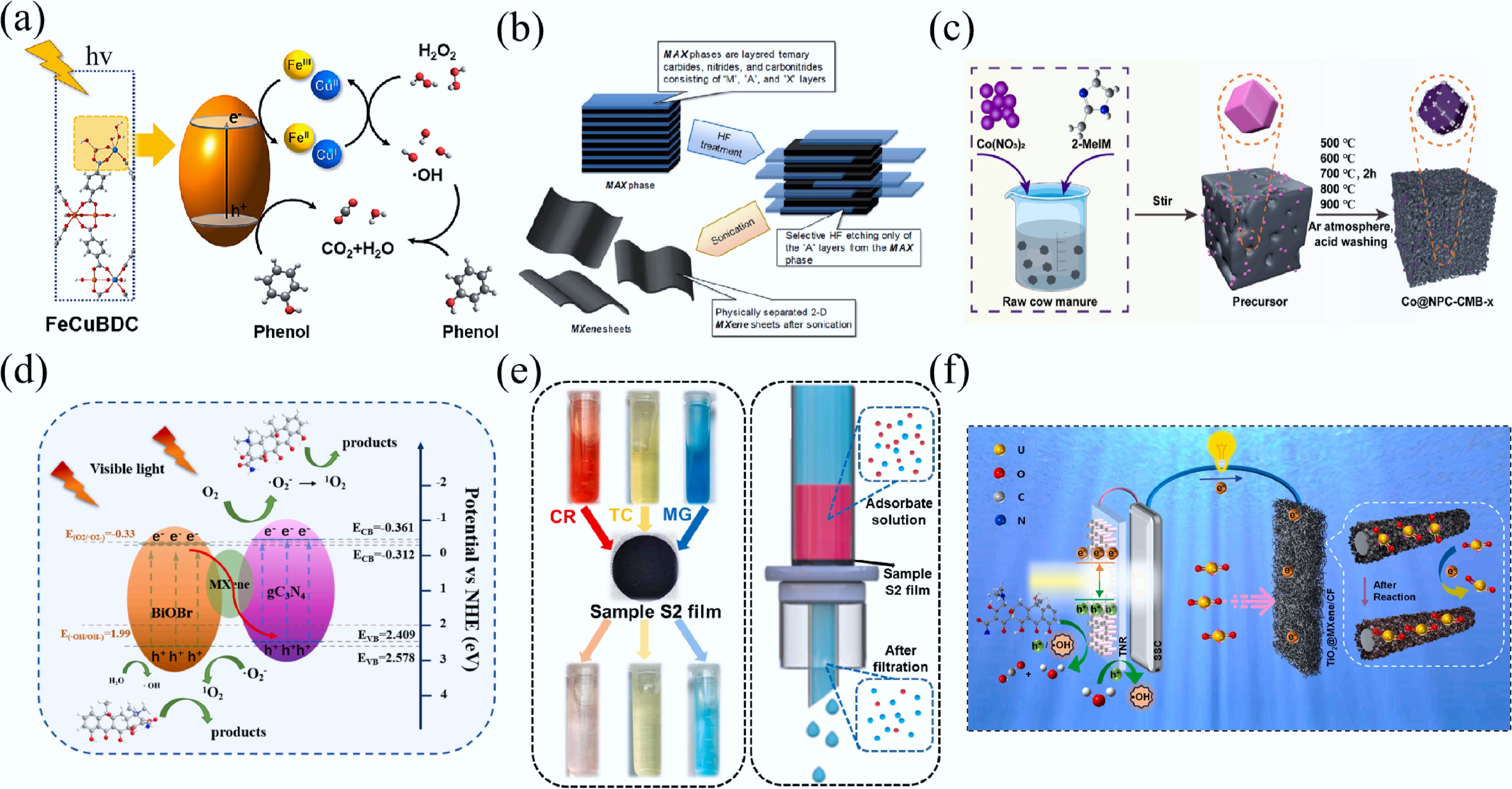

The carbonization technique, as one of the most widely used ways to produce AC, involves carbonizing carbon-rich organic precursors at high temperatures (500–1,500 °C) in an inert atmosphere. During the carbonization process, volatile molecules (e.g., CO, CO2, and alkanes) are removed to produce porous carbon (PC) structures. Many studies show that various carbon precursors (like organic polymers, biomass, metal organic frameworks (MOFs), etc.) and carbonization conditions can regulate the morphology and structure of CMs (such as porosity, doping, and nanostructure). For example, Zhang et al. fabricated a sodium polyacrylate-based PC by direct carbonization (Fig. 2a)[29]. The results showed that at the carbonization temperature of 500 °C under an Ar atmosphere, the pores of the PC exhibited irregular morphologies with many large macropores (> 1 µm), while at 600 °C, the pores became denser, with some being smaller than 500 nm (Fig. 2b, c). At the carbonization temperature above 800 °C, the pores in PC were mainly composed of large diameter pores (> 2 μm) (Fig. 2d). Additionally, they also found that compared to carbonized in Ar, the pore structure of PC in an air atmosphere exhibited more severe structural collapse (Fig. 2e). Zhu et al. synthesized a nitrogen-rich polymer and used it as a precursor[42]. After being activated with KOH, and doped with melamine and urea, the polymer precursor could produce nine carbonized derivatives by adjusting the carbonization temperature. Thanks to the synergistic effect of nitrogen- and oxygen-doped functional groups in its carbonized framework, the CMs (carbonized at 600 °C) exhibited a high adsorption capacity of 2,782 mg/g for gaseous iodine, and 1,854 and 867.55 mg/g for bromine and iodine in solution, respectively. Mo et al. synthesized nitrogen-doped porous carbon (NPC) via pyrolysis of biomass-derived carbon precursors co-treated with urea and ZnCl2 under N2 atmosphere[43]. As the carbonization temperature increased from 800 to 1,000 °C, the NPC-1000 samples exhibited significantly more medium-sized pores (~1 to 10 nm) and fine pores (< 1 nm) in microflake structures compared to NPC-800 and NPC-900. These pore characteristics induced a spatial confinement effect that favored a four-electron reduction pathway in the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Consequently, despite having the lowest contents of pyridinic nitrogen and graphitic nitrogen, the NPC-1000 sample demonstrated superior ORR activity, outperforming commercial Pt/C catalysts.

Figure 2.

(a) Synthesis process of sodium polyacrylate-based PC. SEM graphs of PC carbonized at (b) 500 °C, (c) 600 °C, and (d) 800 °C in an Ar atmosphere, and (e) PC-600 fabricated in air[29]. (f) Diagram of Co/HNC-x samples (where x denotes calcination temperatures: 600, 700, 800, and 900 °C), prepared by carbonizing the ZIF-67@ZIF-8-YS precursor for 2 h in N2, and the corresponding TEM images of (g) Co/HNC-600, (h) Co/HNC-700, (i) Co/HNCW-800, and (j) Co/HNC-900[46].

Apart from organic polymers and biomass precursors, MOFs have been recognized as superior sacrificial precursors for synthesizing CMs in environmental remediation and energy storage/conversion fields[44]. Their tunable chemical compositions and adjustable hierarchical structures enable precise control over heteroatom doping profiles (e.g., N, P, S) and porous architectures in the derived CMs, thereby providing prominent advantages for adsorption capacity, catalytic activity, and electrochemical performance[45]. Through designing the composition of MOF precursors (e.g., organic ligands, metal nodes, coordination manners, and carbonization conditions), various MOF-derived CMs, including metal-free pure carbon or heteroatom/metal/metallide-doped CMs, can be obtained. Zhu et al. constructed cobalt nanoparticles (NPs)/nitrogen-doped carbon composite materials at different carbonization temperatures using hollow ZIF-67 microspheres as precursors (Fig. 2f)[46]. With the increase in carbonization temperature, the particle size of this carbon composite decreased slightly (Fig. 2g−j). At 800 °C, a certain number of carbon nano-whiskers were anchored on the surface of the hollow sphere, forming a unique hierarchical hollow structure. After further phosphating, the cobalt metal/cobalt phosphides/nitrogen-doped carbon composites were obtained, which showed excellent OER electrocatalytic performance. Ling et al. reported a K-defect-rich PC material with 12-vacancy-type defects without N doping by direct carbonization of K+-confined MOFs at 1,100 °C[47]. Remarkably, the resulting K-defect-rich PC presented an ultrahigh CO Faradaic efficiency (FE) up to 99% at −0.45 V, much better than that of N-doped carbon for electro-catalytic CO2 reduction. Zhang et al. fabricated a hierarchical 1D/3D NPC by carbonizing a composite of Zn-MOF-74 crystals that were grown in situ on commercial melamine sponge (MS) for electrochemical CO2RR[48]. The unique spatial architecture of 1D/3D NPC enhanced CO2 adsorption capacity and facilitated electron transfer from the 3D nitrogen-doped carbon framework to the 1D carbon domains, thereby improving the reaction kinetics of CO2RR.

Generally, the carbonization method offers low-cost, scalable production of CMs with moderate to high conductivity, broadband absorption, high specific surface area (SSA, 100–3,000 m2/g), tunable porosity, and rich surface O/N groups via temperature and precursor tuning. Defects or O/N groups in CMs reduce conductivity and photoluminescence but increase active sites, enhancing catalytic activity (e.g., ORR outperforming Pt/C) and pollutant adsorption. However, this method requires high temperatures (500–1,500 °C), leading to substantial energy consumption; the products have limited crystallinity (ID/IG >1.5), limiting high conductivity. Moreover, strict dependence on inert atmospheres complicates the process, and biomass-derived carbon yields are only 47%–50%. Though CO2 conversion and other techniques mitigate environmental impact, its sustainability lags behind greener alternatives like hydrothermal methods and flash Joule heating.

Templating method

-

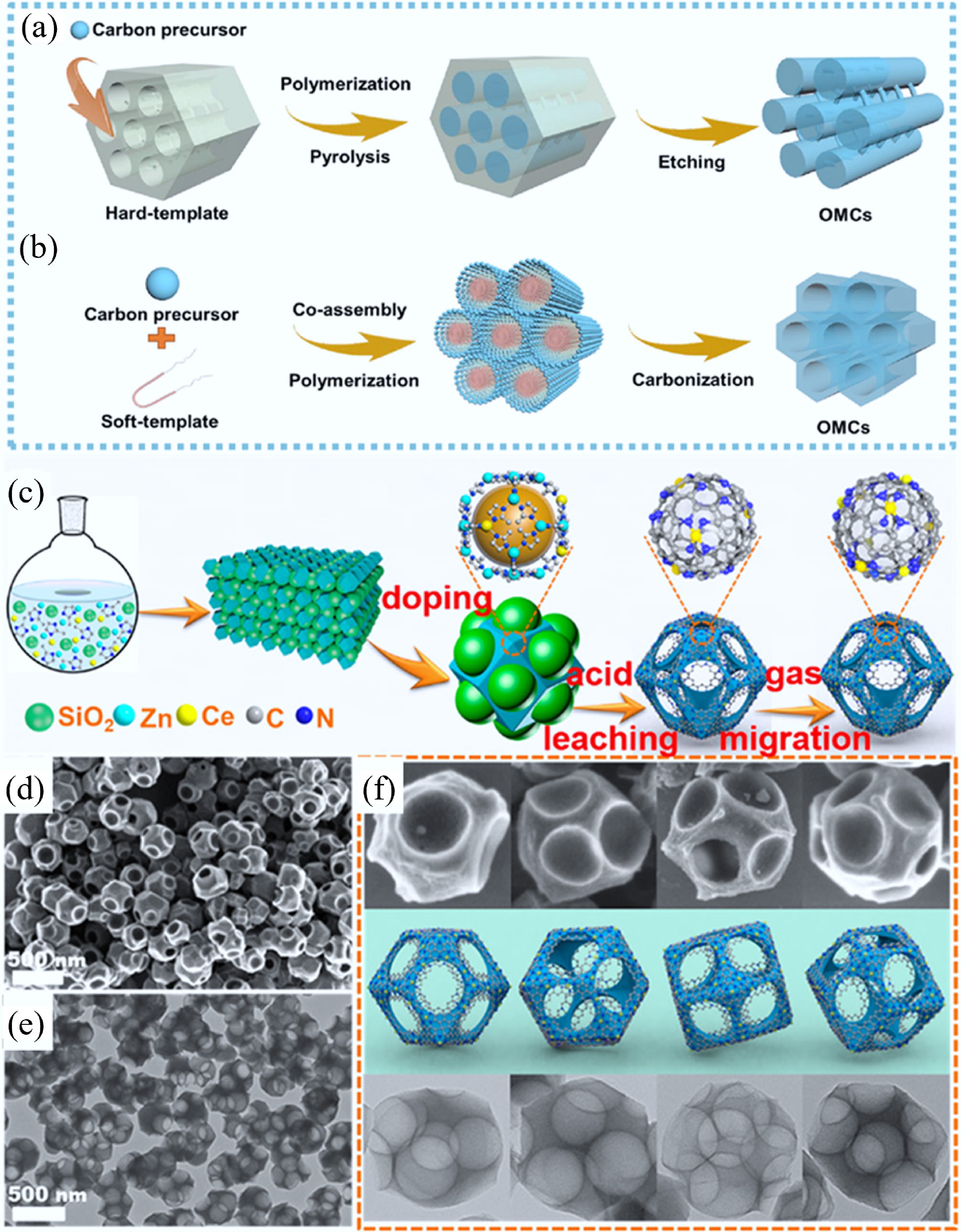

The template method, including hard templating and soft templating, was first adopted to obtain ordered mesoporous carbons (OMCs) by removing various pre-existing sacrificial templates in precursors. As early as 1999, OMCs were first prepared using ordered mesoporous silicates as hard templates (Fig. 3a)[30]. The carbon precursor was filled inside the mesopores, polymerized, and then carbonized. After removing the silica scaffold by etching, OMCs that replicated the silica meso-channels were produced. Following that, OMCs were also synthesized by a self-assembly approach, i.e., soft templating (Fig. 3b). Soft templates (e.g., supramolecular aggregates) and carbon precursors are co-assembled into 3D-ordered meso-structures. After eliminating the supramolecular aggregates by regulating the calcination temperature, meso-carbonaceous framework was preserved. In the past five years, CMs with various morphologies and pore structures have been synthesized for environmental and energy applications. For example, Zhu et al. reported atomically dispersed Ce sites embedded in a hierarchically macro–meso–microporous N-doped carbon catalyst (Ce SAS/HPNC) by a hard-template approach (Fig. 3c)[49]. During the synthesis process, Ce-doped ZIF-8 precursors with a SiO2 ball embedded in every face of the rhombododecahedron were first prepared. After carbonization and acid leaching, SiO2 was removed to produce a hierarchically macro–meso–microporous N-rich PC. At 1,150 °C in flowing N2, an atomically dispersed Ce SAS/HPNC catalyst was finally formed. As shown in Fig. 3d−f, the as-formed Ce SAS/HPNC catalyst exhibited a porous-rhombododecahedral single particle morphology with holes at an average of 167 nm. Benefiting from the atomic dispersion of Ce atoms and a unique 3D hierarchical ordered porous architecture, the Ce SAS/HPNC possessed dramatic catalytic activity due to enhanced mass transport and exposing more active sites. Through a simple soft template polymerization and activation strategy, Zhang et al. synthesized polypyrrole (PPy)-based N, S co-doped porous CNTs[50]. During the synthesis, rod-like soft templates were first formed by using methyl orange (MO) and FeCl3 as templating agents. Then, pyrrole monomer was polymerized on MO-FeCl3 template to form PPy nanotubes, while surfactant hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide was added to modify the branched PPy nanotube structure. Subsequently, the activated N, S co-doped porous CNT was produced after pyrolysis using sulfur as a dopant and ZnCl2 as an activator. As a result, this N, S co-doped porous CNT electrode exhibited high energy storage capacity, excellent rate performance, and superior cyclic stability.

Figure 3.

Scheme for the synthesis of OMCs by using (a) ordered mesoporous silicates as hard-templates and (b) supramolecular aggregates as soft-templates[30]. (c) Fabrication procedure of a hierarchically macro–meso–microporous N-doped carbon (Ce SAS/HPNC) catalyst by using SiO2 as hard-templates, (d) SEM, (e) TEM, and (f) both images of Ce SAS/HPNC corresponding to the models from different angles[49].

The hard templating approach generally enables precise pore size control and ordered architectures, while the soft templating approach creates tunable mesopores, enabling hierarchical porosity. Both templating approaches exhibit relatively low conductivity owing to their amorphous or partially graphitic structures. Compared to carbonization-derived CMs, the ordered porosity and low defect density of templated CMs reduce light scattering, thus improving optical absorption efficiency. Templated CMs typically possess high SSA and tunable surface chemistry, with soft templating allowing heteroatom doping (e.g., N, P) during synthesis to enhance surface reactivity. The ordered porosity and high SSA of templated CMs facilitate mass transfer and atomic-level active site exposure, promoting pollutant capture (e.g., heavy metals, dyes), and enhancing CO2RR electrocatalytic activity. However, the low conductivity of templated CMs limits their suitability for HER. Meanwhile, multi-step synthesis processes, high costs, high chemical waste generation, and energy-intensive procedures limit their scalability and sustainability.

CVD

-

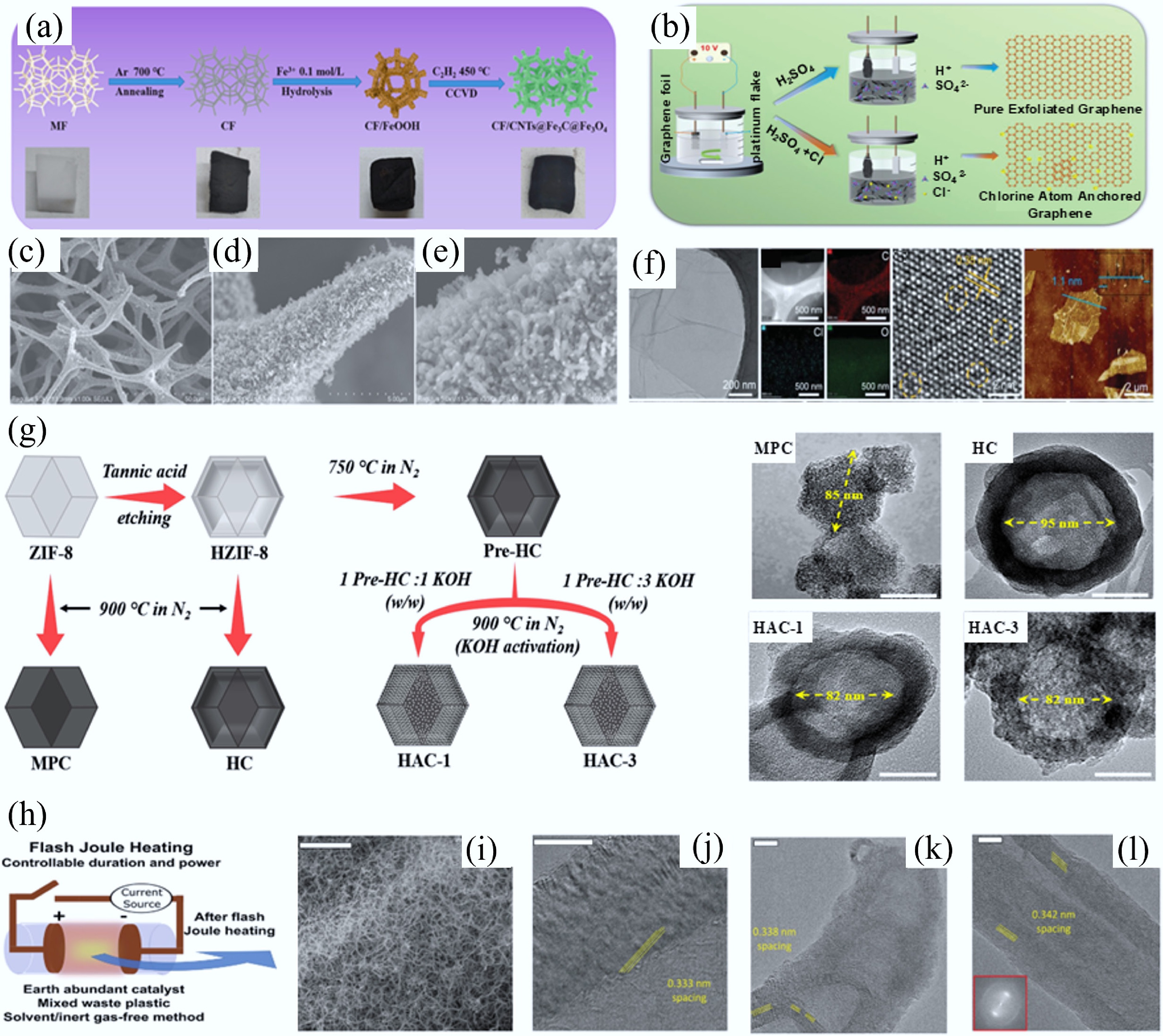

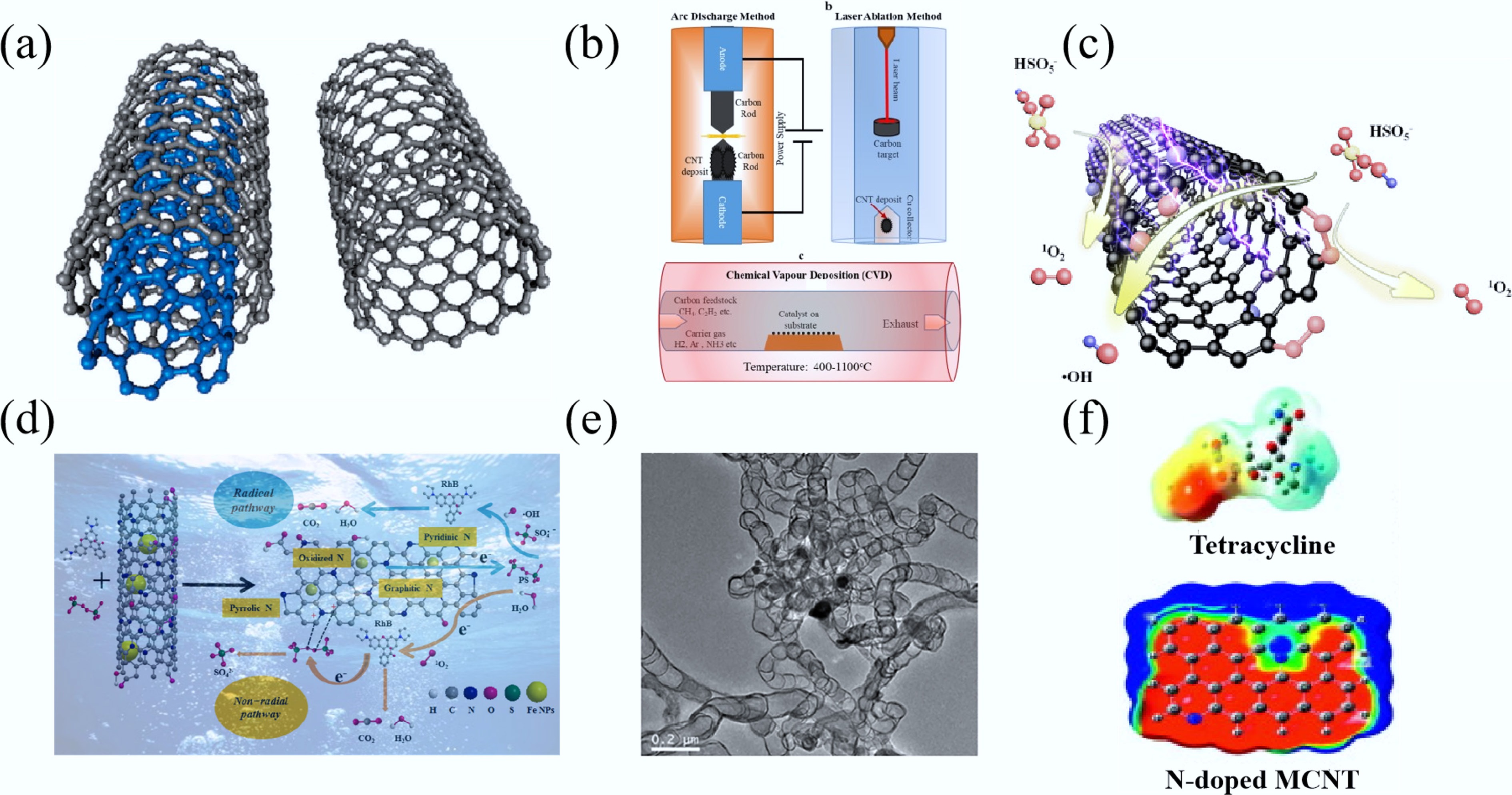

The principle of the CVD technique to synthesize CMs is that carbon source gases (i.e., methane and acetylene) decompose on the surface of catalysts (such as metal NPs) at high temperatures (700–1,200 °C), and carbon atoms grow and assemble on the substrate to form nanoscale CMs. This technique was originally developed in the 1960s and 1970s and used in the production of carbon fibers (CFs) and carbon nanofibres[51,52]. In 1996 and 2008, CVD was separately reported as a potential method for large-scale synthesis and production of CNTs[53] and graphene. Studies have shown that different carbon sources, catalyst substrates, and reaction conditions would greatly influence the types, morphology, and structure of CMs. Wang's group employed ring-rich polystyrene (PS) vapor and chain-rich polyethylene (PE) vapor as carbon precursors to study the growth mechanisms of carbon nanomaterials (CNMs) on biochar substrates[54,55]. When PS vapor was used as a carbon source, three types of CNMs, i.e., bulk amorphous carbon, monolayer amorphous carbon, and CNFs, were produced. Conversely, only bulk amorphous carbon and CNFs were found by using PE vapor. Meanwhile, they found that the substantial carbon deposition on biochar surfaces was attributed to stable C-C bonds formed between PS/PE, and biochar. The presence of aromatic rings in PS vapor resulted in the monolayer amorphous carbon growth, while the presence of sp2 carbon in PE vapor leads to CNFs growth. Chen et al. developed a space-confined-CVD method to prepare hard CMs with graphite-like carbon domains filled into the micropores of AC[55]. During the synthesis process, benzene carbon sources tended to be adsorbed onto the pore wall inside AC due to the van der Waals force between π orbital on the carbon planes and the electronic density in the benzene. At 700 °C, benzene was pyrolyzed into a flat graphene layer. Through changing the space confined-CVD residence time and the temperature of post-heat treatment, the interlayer spacing and size of graphitic carbon were facilely adjusted. Zhu et al. investigated the wrinkling/folding process of graphene by using ethylene as a carbon precursor and single-crystal Cu–Ni(111) foils as substrates[56]. They found that when the growth temperature was above 1,030 K, the folds would form during the subsequent cooling process. Through rationally controlling the growth temperature between 1,000 and 1,030 K, they successfully synthesized large-area, fold-free, single-crystal single-layer graphene films. Jia et al. fabricated a mixed-dimensional CF/CNTs@Fe3C@Fe3O4 heterostructure by a continuous process including carbonization of melamine foam (MF), synthesis of carbon foam (CF)/FeOOH, and the in-situ growth of CNTs in a C2H2 atmosphere by the catalytic chemical vapor decomposition (Fig. 4a)[57]. The SEM images showed that the as-formed material exhibited good 3D interconnected networks without the collapse of skeleton (Fig. 4b). And the closer SEM results suggested that this material possessed a rough surface and many flocculent CNTs growing around the entire skeleton (Fig. 4c–d). Especially, the content of CNTs in the CF/CNTs@Fe3C@Fe3O4 samples could be effectively enhanced by increasing the pyrolysis time of the C2H2 carbon source. It is worth noting that although CVD yields high-quality graphene/CNTs, the impacts of spatially non-uniform reactions, catalyst instability, and energy-intensive precision control on the mass production of graphene/CNTs merit serious consideration.

Figure 4.

(a) Synthesis of CF/CNTs@Fe3C@Fe3O4 via in-situ growth of CNTs via catalytic CVD of C2H2 at 450 °C. (b)–(d) SEM images of CF/CNTs@Fe3C@Fe3O4 with different magnifications[57]. (e) Preparation process of chlorine-doped graphene (working electrode: graphite flake; counter electrode: platinum foil; electrolyte: sulfuric acid with chloride salt; applied potential: +10 V) and (f) morphology and structure characterizations[62]. (g) Synthetic pathways and corresponding morphologies of MPC (microporous carbon from ZIF-8 carbonization), HC (hollow carbon from tannic acid-etched ZIF-8 carbonization), HAC-1 and HAC-3 (hollow AC from HC activated with KOH/pre-HC weight ratios of 1 and 3, respectively, at 900 °C in N2)[63]. (h) Preparation of flash 1D materials via FJH using waste polymer as starting material (~3,000 K temperatures generated in 0.05–3 s) and (i)−(l) different morphologies of flash 1D materials[64].

Unlike templated or etched CMs that have high-porosity CMs (SSA > 1,000 m2/g), the CVD CMs typically have non-porous, dense structures (e.g., graphene, CNTs) with relatively low SSA (< 500 m2/g). Notably, CVD CMs exhibit exceptional conductivity (> 104 S/m) due to high crystallinity, outperforming carbonized or templated CMs. Meanwhile, CVD CMs, with tunable band gaps (e.g., graphene quantum dots) and high transparency (e.g., atomically thin CVD graphene), are ideal for optoelectronic applications. Different from etched or templated CMs, which are featured with abundant defects and edge sites, the CVD CMs have smooth, pristine conductive surfaces with few active sites, which is beneficial for their regeneration when used as electrode materials. The high conductivity of CVD CMs makes them perfect candidates for HER. Engineered defects or heteroatom doping can effectively enhance their CO2RR/ORR/OER catalytic activity. However, the CVD method requires high temperatures (500–1,500 °C), metal catalysts, and toxic precursors (e.g., methane), restricting its scalability and sustainability.

Top-down synthesis

Exfoliation

-

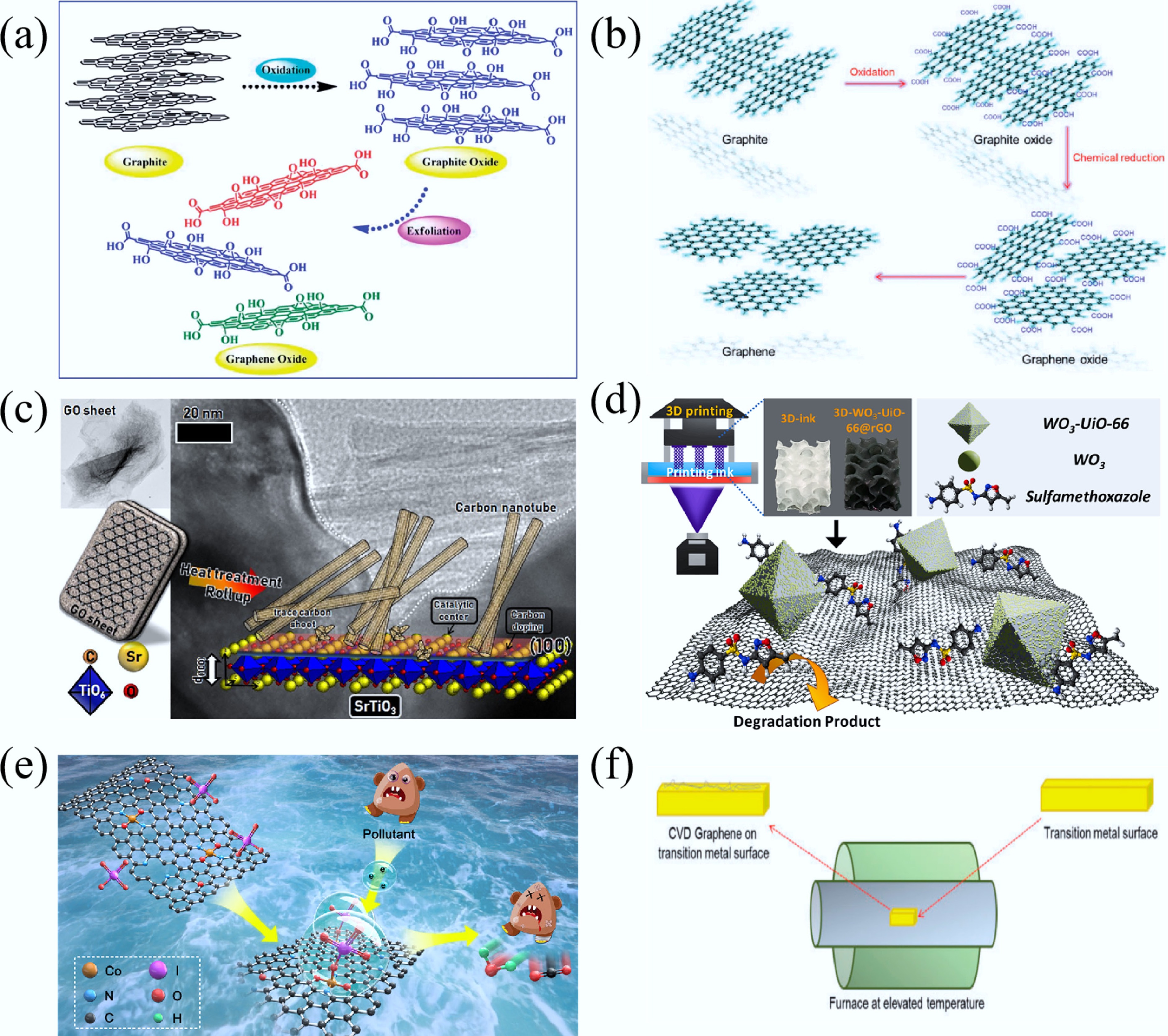

Exfoliation techniques are mainly used to synthesize graphene and its derivatives. Generally, exfoliation begins with the bulk graphite. With the help of external forces, the van der Waals forces between graphite layers can be broken, thus allowing graphene to be stripped from the graphite[58]. Based on the external force, exfoliation can be categorized into mechanical exfoliation, chemical exfoliation, and electrochemical exfoliation, etc. Mechanical exfoliation was first reported to synthesize graphene in 2004 by Novoselov and Geim, and they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010[59]. In their work, the few-layer graphene sheets were separated from graphitic flakes by repeatedly peeling bulk graphite crystals with Scotch Tape. This method is simple and reliable, but the yield is low and not suitable for reproducibility or large-scale production of graphene. Chemical exfoliation obtains graphene by using chemical reagents (such as strong acids, strong oxidants, intercalating agents, etc.) to break the interlayer bonding forces in graphite. A representative technique of chemical exfoliation is the Hummers method[58]. During the preparation process, acids and oxidizing agents intercalate into graphite to expand the interlayer spacing and form graphene oxide (GO). Under ultrasonication or mechanical stirring, GO is exfoliated into the single- or few-layer graphene. Finally, graphene is produced through the chemical reduction of GO using a reductant (e.g., hydrazine). This method is simple, convenient, and scalable for the mass production of graphene, but it may introduce structural defects and degrade its electronic properties for certain applications. Electrochemical exfoliation is another fast, cost-effective, environmentally benign, and scalable way to prepare graphene. By applying voltage to a graphite electrode, ions in the electrolyte (e.g., (NH4)2SO4) are driven to insert and expand the graphite layers. Meanwhile, the generated gas (H2/O2) further impairs interlayer bonds, thereby mechanically exfoliating graphite into few-layer graphene with low defects[60]. In 2008, Liu et al. adopted this method to obtain exfoliated product with an average length of ~700 nm, a width of 500 nm, and a thickness of 1.1 nm, demonstrating complete exfoliation from graphite to graphene nanosheets[61]. In the past five years, exfoliation techniques have been adopted to synthesize various doped graphene. For example, Liu et al. prepared the high-quality and solution-processible chlorine-doped graphene nanosheets by the electrochemical exfoliation technique[62]. In the exfoliation process, a graphite flake was used as the working electrode with dilute sulfuric acid containing chloride salt as the electrolyte (Fig. 4e). By applying a +10 V potential for 10 min, ultrathin and rugged 2D chlorine-doped graphene nanosheets with a large lateral size of ~10 µm have been synthesized. Morphological and structural characterization results indicated that chlorine-doped graphene nanosheets exhibited high structural uniformity, homogeneous distributions of carbon, chlorine, and oxygen elements, a high degree of crystallinity, abundant defects, and a topographic thickness of 1.1 nm (Fig. 4f).

Graphene prepared by the three exfoliation methods shows different structural and performance features. Mechanically exfoliated graphene has fewer pores, excellent conductivity (retaining its pristine sp2 structure), and superior optical properties from layer-dependent absorption, but lacks surface functionality. Chemically exfoliated graphene forms pores via sheet restacking, experiences significant conductivity loss due to oxidative defects, exhibits tunable optical transitions, and contains abundant surface O groups. In contrast, electrochemically exfoliated graphene exhibits moderate conductivity and porosity, fewer surface O groups, and retains decent optical absorption. For environmental remediation, chemical exfoliation outstrips mechanical exfoliation (inert surfaces) owing to rich O groups and porosity, while electrochemical exfoliation balances adsorption capacity and stability. For catalysis, mechanically exfoliated graphene with pristine basal planes excels in HER, while chemically/electrochemically exfoliated graphene, with defect-mediated activity, performs better in CO2RR/ORR/OER. Owing to aqueous processing, moderate yield, low chemical usage, and energy efficiency, electrochemical exfoliation outperforms the other two in scalability and sustainability. Overall, while superior to carbonization/templating in targeted graphene synthesis, these methods face inherent efficiency-performance tradeoffs.

Etching

-

The etching strategy, involving chemical and physical etching, mainly relies on selectively removing certain substances from the CMs, thereby regulating their microstructures (such as pore size, defects, morphology, etc.) to obtain specific properties. Chemical etching primarily employs strong acids, strong bases, or oxidants to react with CMs, selectively removing amorphous carbon or introducing pores. For example, Kim and his colleagues reported hollow ACs with a hollow nanoarchitecture and high SSA via a chemical etching strategy[63]. They first adopted tannic acid as a selective etching agent to create a hollow cavity in the center of zeolite imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) (Fig. 4g). Then, hollow carbon was obtained after a carbonization process. Furthermore, through the reaction between KOH and carbon atoms (6KOH + 2C ↔ 2K + 3H2 + 2K2CO3), hollow AC-x (where x = 1 or 3 corresponded to the KOH/pre-hydrochar weight ratio) with more nanopores and an increased SSA was generated. These well-designed hollow activated CMs, featuring a hollow nanoarchitecture and high BET SSA, show great potential in the energy storage field. Instead of the usage of traditional strong acids, Zhang et al. utilized a selenic-acid-assisted etching strategy to synthesize Co0.85Se1−x@C electrocatalysts toward OER[65]. The selenic acid, with weak acidity, can only partially etch the ZIF-67 framework and serves as a selenium source. After subsequent calcination, a carbon layer-coated Co0.85Se1−x with abundant Se vacancies was obtained under an inert atmosphere. The unique structure of Co0.85Se1−x@C improved the catalytic activity for OER through increasing the number of active sites, enhancing the conductivity, and reducing reaction barriers for the formation of intermediates.

The physical etching method utilizes high-energy particle bombardment (i.e., plasma) or gas-phase (i.e., CO2) reactions to obtain porous CMs. Liu et al. utilized the N2 plasma-etching strategy to regulate defects and N species in CNTs. By controlling the plasma-etching time, the vacancy defects, C-O, pyrrolic N, and graphitic N could be rationally designed[66]. The ID/IG (from 0.56 to 0.94) and C–O contents (from 0.07% to 0.44%) of N-CNTs rose with increasing etching time. Zheng et al. developed a mild CO2-etching and carbonization strategy to generate abundant closed pores in starch-derived hard carbon[67]. During the CO2-etching process, abundant open micropores were created in the AC matrix via the reaction (CO2 + C → 2CO). Due to CO2 etching, the pore diameter in hard carbon microspheres increased from 3.82 to 4.86 nm, with corresponding pore volume rising from 0.045 to 0.117 cm3/g.

Both chemical and physical etching generate hierarchical porosity via selective atomic removal, but chemically etched CMs typically have larger SSA than physically etched ones. Etching-induced defects reduce conductivity, yet optimized defect density accelerates charge transfer kinetics in electrocatalysis. Enhanced light scattering and absorption from increased defects and porosity in etched CMs benefit their photothermal applications. Chemical etching enriches surfaces with O/N groups and enables precise doping, while physical etching creates reactive edges with few heteroatoms. Generally, chemically etched CMs show strong affinity for organic contaminants and excel in CO2RR (O-mediated active centers) and ORR (defect sites) but underperform in HER due to low conductivity; physically etched ones show moderate ORR/HER activity via edge exposure. Both lack scalability and sustainability: chemical etching uses corrosive reagents (H2SO4/KOH), risking harm; physical etching faces energy/cost barriers. Etching excels at tailoring surface sites for specific CM catalysis but lags behind templating in pore uniformity and CVD in electrical properties.

Emerging sustainable synthetic technologies

-

Very recently, some green synthetic techniques have also emerged to synthesize CMs, involving biomass-based hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) method[5,68,69], CO2 utilization[70], FJH[64], etc. Particularly, biomass-based HTC has become a research hotspot over the past decade for synthesizing CMs from types of biomass waste due to its eco-friendliness, non-toxicity, and energy-efficiency. Considering that glucose is the most abundant sugar in biomass and the main product of lignocellulose acid hydrolysis, Ischia et al. systematically investigated the fundamentals of the HTC conversion over several operating conditions (180–270 °C and 0–8 h) by using a 1.1 M glucose solution as a carbon precursor[69]. Results revealed that hydrochar changed notably with time only at 180 °C, and the solid yield stabilized at 47%–50% with the carbon content of 67%–70% above 180 °C. Meanwhile, hydrochars were found to comprise distinctive nano/microspheres whose size distribution correlated with operating conditions. These materials mainly exhibited an amorphous structure and gradually evolved toward graphitization with intensified HTC severity. Hessien[68] adopted a microwave-assisted HTC method to prepare hydrochar from pomegranate peel waste at 200 °C for 1 h with a peel to water mass ratio of 1:10. The results confirmed that the as-formed amorphous hydrochar exhibited a porous structure, showing potential as an adsorbent for methylene blue (MB) dye removal.

HTC generates CMs with moderate porosity and amorphous nature, leading to relatively low conductivity and broad optical absorption. HTC-derived CMs inherit rich O-groups from biomass precursors, which is beneficial for polar pollutant adsorption and facilitating CO2RR via improved CO2 adsorption, but impede ORR/HER due to poor conductivity and insufficient graphitic active sites. The scalability/sustainability of HTC for CMs fabrication lies in its mild conditions (< 250 °C), use of biomass feedstocks, and minimal energy/chemical usage.

CO2 utilization has emerged as a sustainable strategy for synthesizing CMs via CO2 conversion, offering a dual benefit of resource utilization and CO2 emission mitigation. Yuan et al. reported the transformation of CO2 and ethane into CNTs using earth-abundant metals (Fe, Co, Ni) as catalysts at 750 °C[70]. Through regulating the H2/CO ratios, this strategy not only generated a rapid rate of CNTs' production, but also yielded valuable syngas. In the absence of CO2, direct pyrolysis of ethane underwent rapid deactivation, while the participation of CO2 contributed to 30% of CNT formation. Meanwhile, CNTs generated from Co- and Ni-based catalysts had a diameter of 20 nm with a micrometer length, whereas those using Fe-based catalysts were bamboo-like. This study establishes a breakthrough CO2-to-CNT conversion platform, demonstrating dual environmental and economic advantages through carbon-negative synthesis of high-performance nanotubes for energy storage applications.

CO2 utilization-derived CMs exhibit tunable porous structures via CO2 activation and moderate conductivity attributed to defect-rich frameworks. Their optical absorption is broad but less tunable due to inherent defects and porosity. Surface groups derived from CO2, such as carbonate species, enhance CO2 affinity, conferring superiority in CO2RR through a direct carbon-negative pathway and tailored active sites. However, limited graphitic domains result in modest ORR/HER activity. While this method achieves net carbon negativity by directly sequestering CO2, outperforming others in emissions mitigation, its high energy demands (600–1,000 °C) and low conversion efficiency constrain scalability compared to HTC or FJH.

Recently, FJH has emerged as a rapid, sustainable, and scalable method for solvent-free carbon production. This technique uses electricity and resistance to generate extreme temperatures (~ 3,000 K) in milliseconds (0.05–3 s), converting low-value waste into high-value products without solvents. Using the FJH technique, Wyss et al. successfully demonstrated the conversion of waste plastic into flash 1D materials and hybrid graphitic 1D/2D materials with controllable morphologies through adopting a variety of earth-abundant catalysts (Fig. 4h)[64]. Through FJH parameter tuning, fiber-like products were formed (Fig. 4i). TEM images showed that morphologies of flash 1D materials included ribbon-type and bamboo-like nanofibers, as well as multi-walled nanotubes (Fig. 4j–l). The as-produced flash 1D materials outperformed commercial CNTs in many properties.

Compared to other methods, FJH-derived CMs integrate ultrahigh processing efficiency with superior performance. Explosive degassing during synthesis generates ultrahigh SSA and hierarchical pores (micro/meso/macro), surpassing templated carbons in pore complexity. By rapidly repairing defects within the sp2 framework, FJH-derived CMs achieve near-metallic conductivity—far outperforming pyrolysis, HTC, and exfoliation methods while rivaling CVD-derived carbons. Simultaneously, tunable optical absorption/emission is enabled through in situ heteroatom doping (N, P, and S). Beyond superior pollutant capture via rapid adsorption kinetics enabled by hierarchical pores, these FJH CMs also surpass counterparts in ORR/OER/HER catalysis through balanced graphitic domains and atomic-scale active sites. Doped variants further demonstrate competitive CO2RR performance. Though templated CMs offer finer pore uniformity and CVD higher crystallinity, FJH dominates in harmonizing high SSA, extremely high conductivity, and millisecond processing—establishing it as the most scalable and energy-sustainable strategy for high-performance carbons.

Structure engineering

-

To advance the application of CMs in environmental protection and energy sectors, recent efforts have focused on modifying their physicochemical and structural properties through strategies such as pore structure and morphology optimization, heteroatom doping, surface modification, and composite formation.

Pore structure

-

The large SSA and hierarchical porosity of CMs serve as fundamental determinants for their deployment in sustainable energy and environmental remediation. Pore structures are classified into three categories based on IUPAC standards: micropores (< 2 nm) that enable molecular sieving effects and maximize active sites for small-molecule adsorption/charge storage, mesopores (2–50 nm) that accelerate ion diffusion kinetics, and macropores (> 50 nm) that act as mass transfer highways to minimize diffusion resistance[71]. Owing to the synergistic effects of multiscale porosity, hierarchically porous carbons have been established as a strategic material platform for sustainable energy and environmental remediation, thereby driving cutting-edge research in targeted pore engineering. For example, Wang & Mu constructed a hierarchically porous waste soybean meal AC via three steps of pre-curing, carbonization, and alkali activation[72]. A honeycomb-like skeleton structure was first obtained via hydrogen bonding crosslinking by pre-curing. Then, macropores were maintained by carbonizing the porous skeleton, while mesopores and micropores were created by alkali activation. The resulting material possessed an ultra-high SSA (3,536.95 m2/g), as well as a hierarchical macro–meso–microporous structure. Consequently, this hierarchical porous structure exhibited extremely high adsorption capacities for MB (3,015.59 mg/g), MO (6,486.30 mg/g), and mixed dyes (8,475.09 mg/g), and fast adsorption kinetics for MB and MO (~30 min). Its highly efficient adsorption performance for dyes was mainly ascribed to its excellent hierarchically porous structure and the synergy of multiple adsorption mechanisms containing π–π stacking, pore-filling, electrostatic interaction, and hydrogen bond interaction.

Heteroatom doping

-

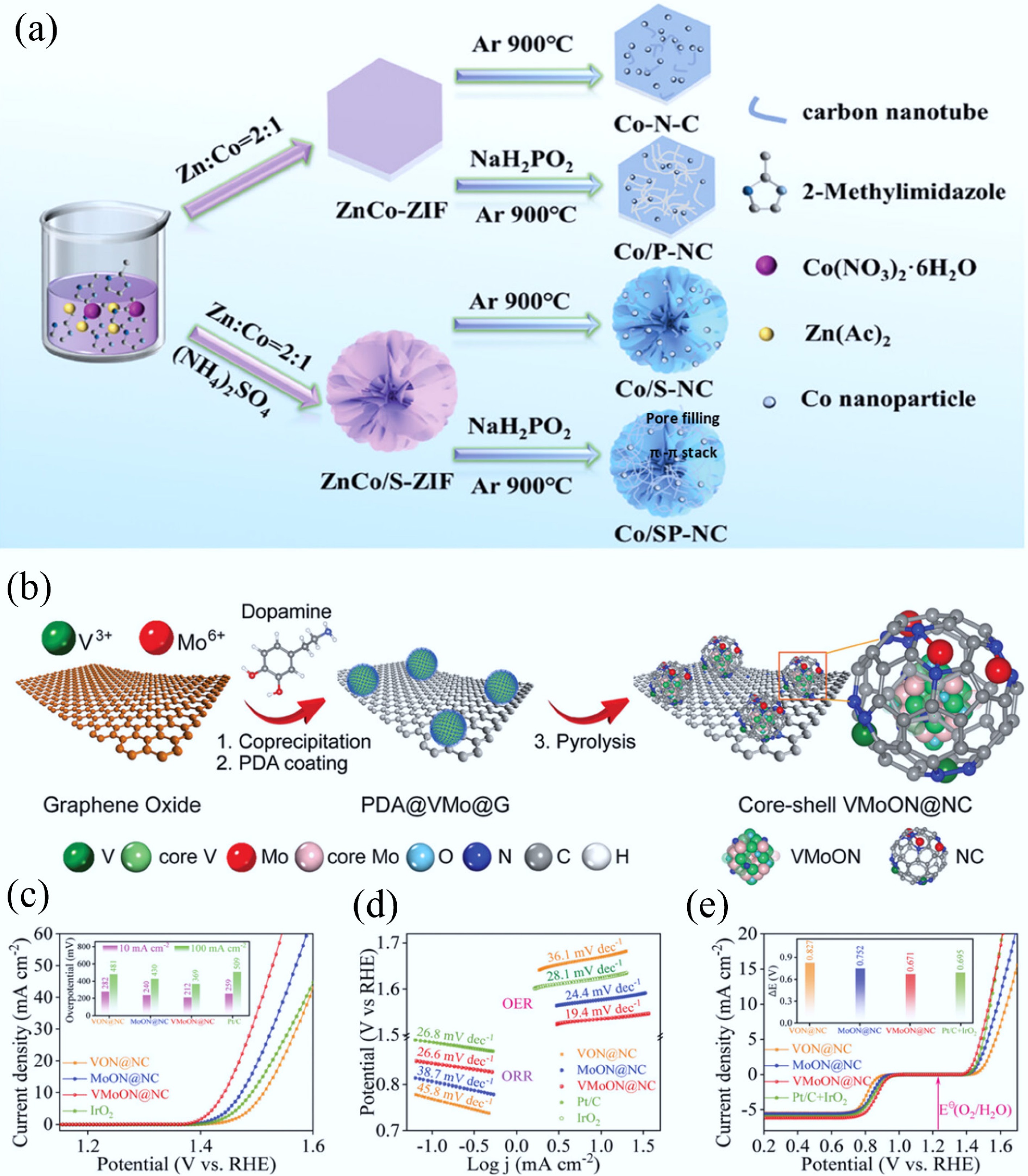

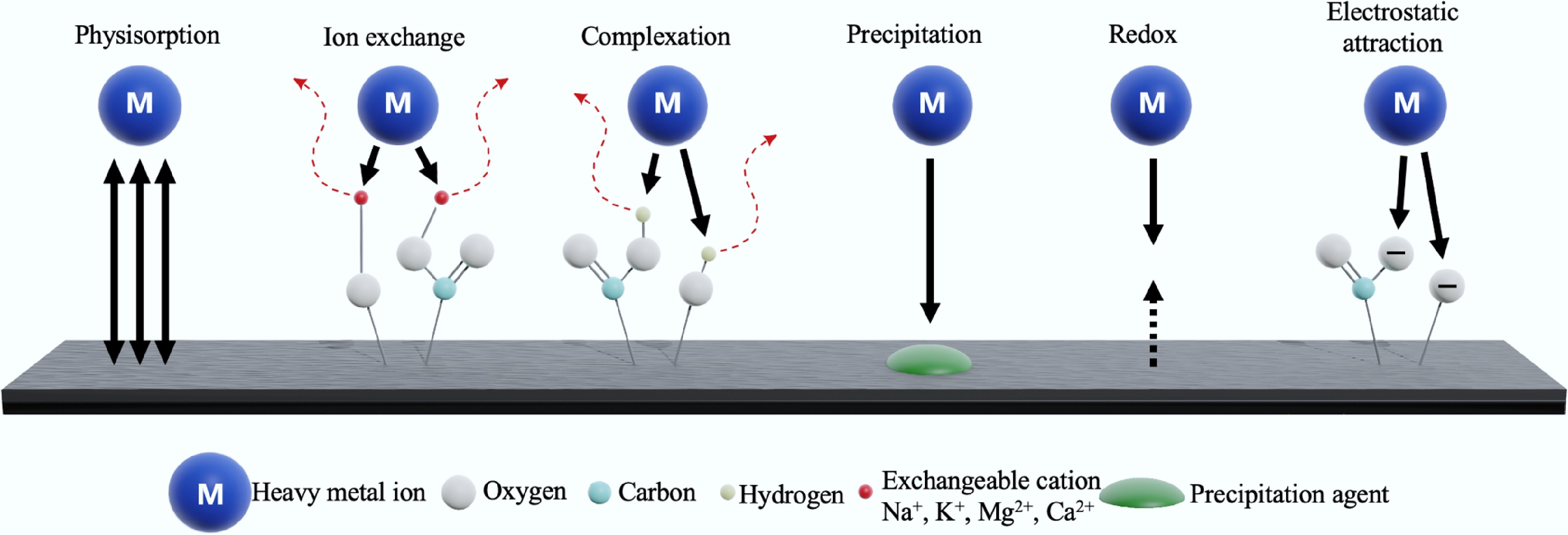

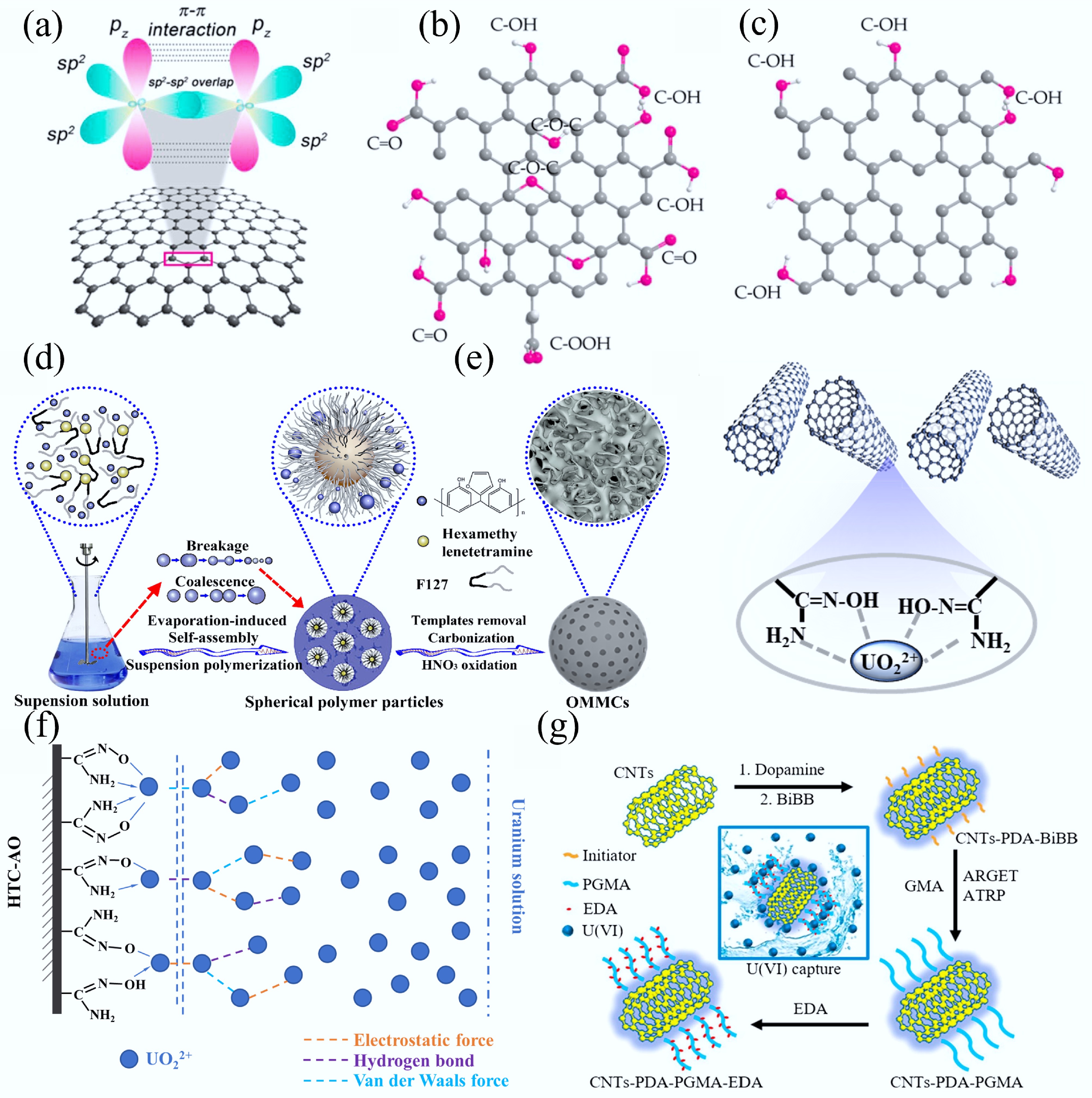

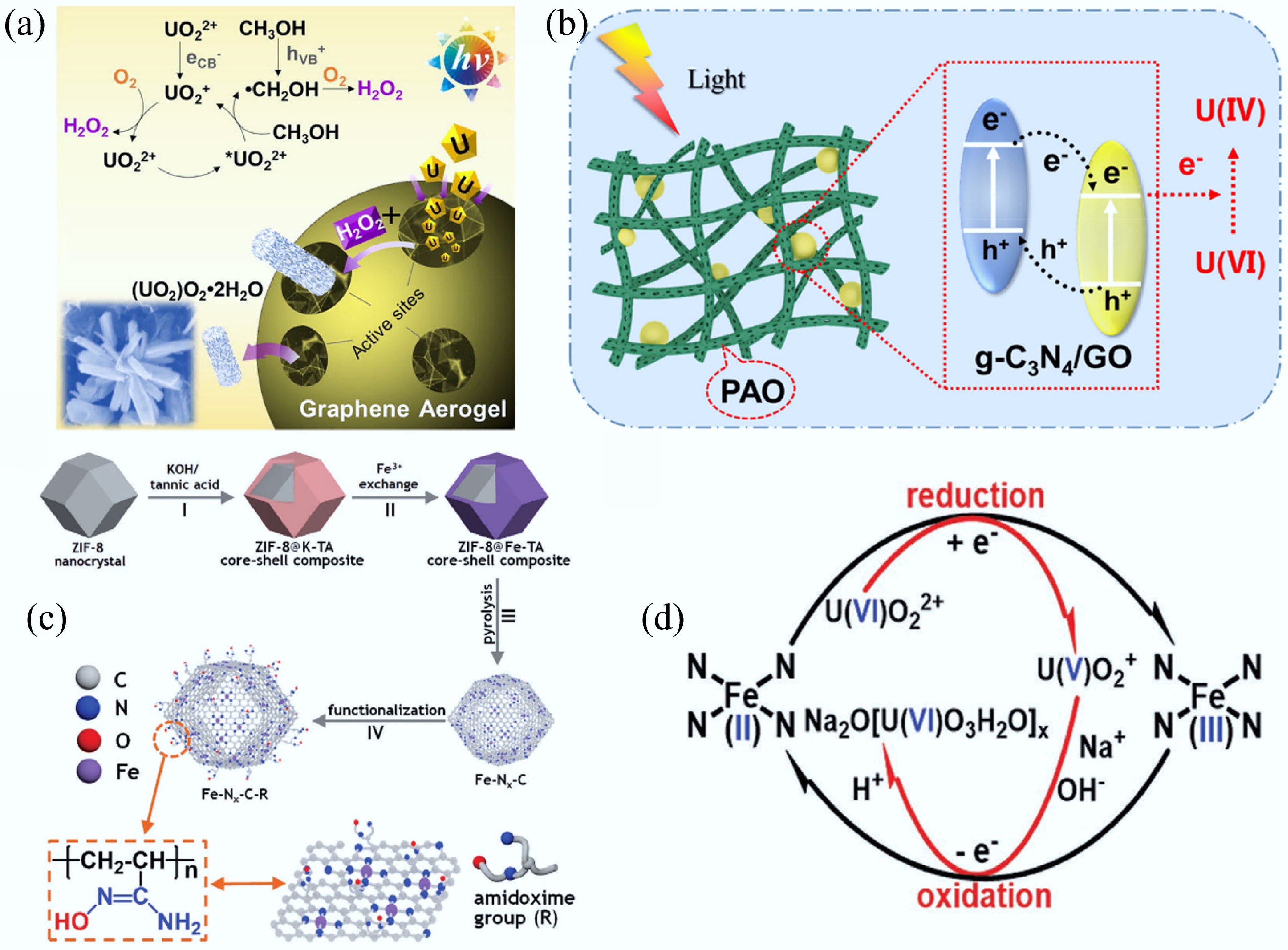

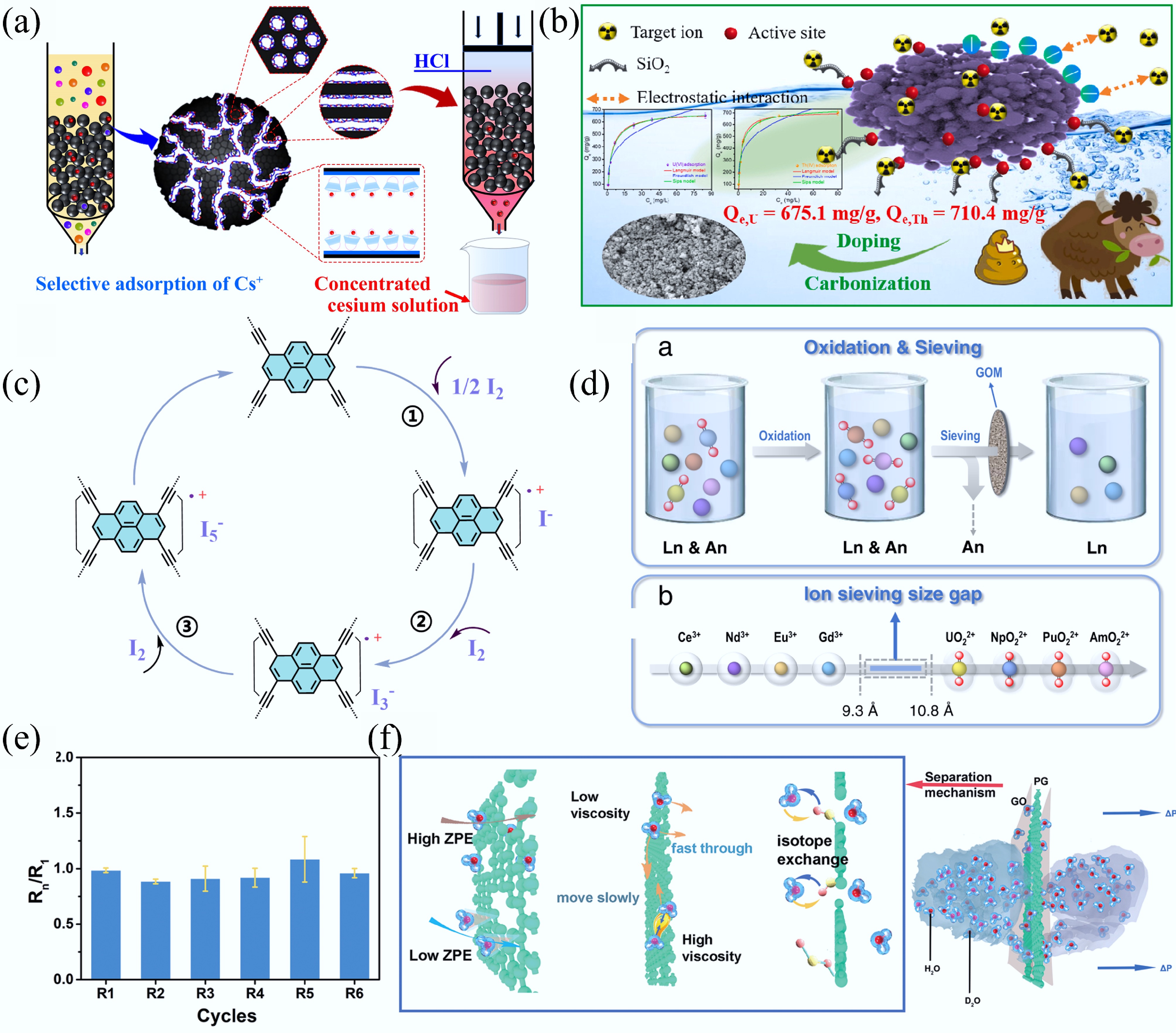

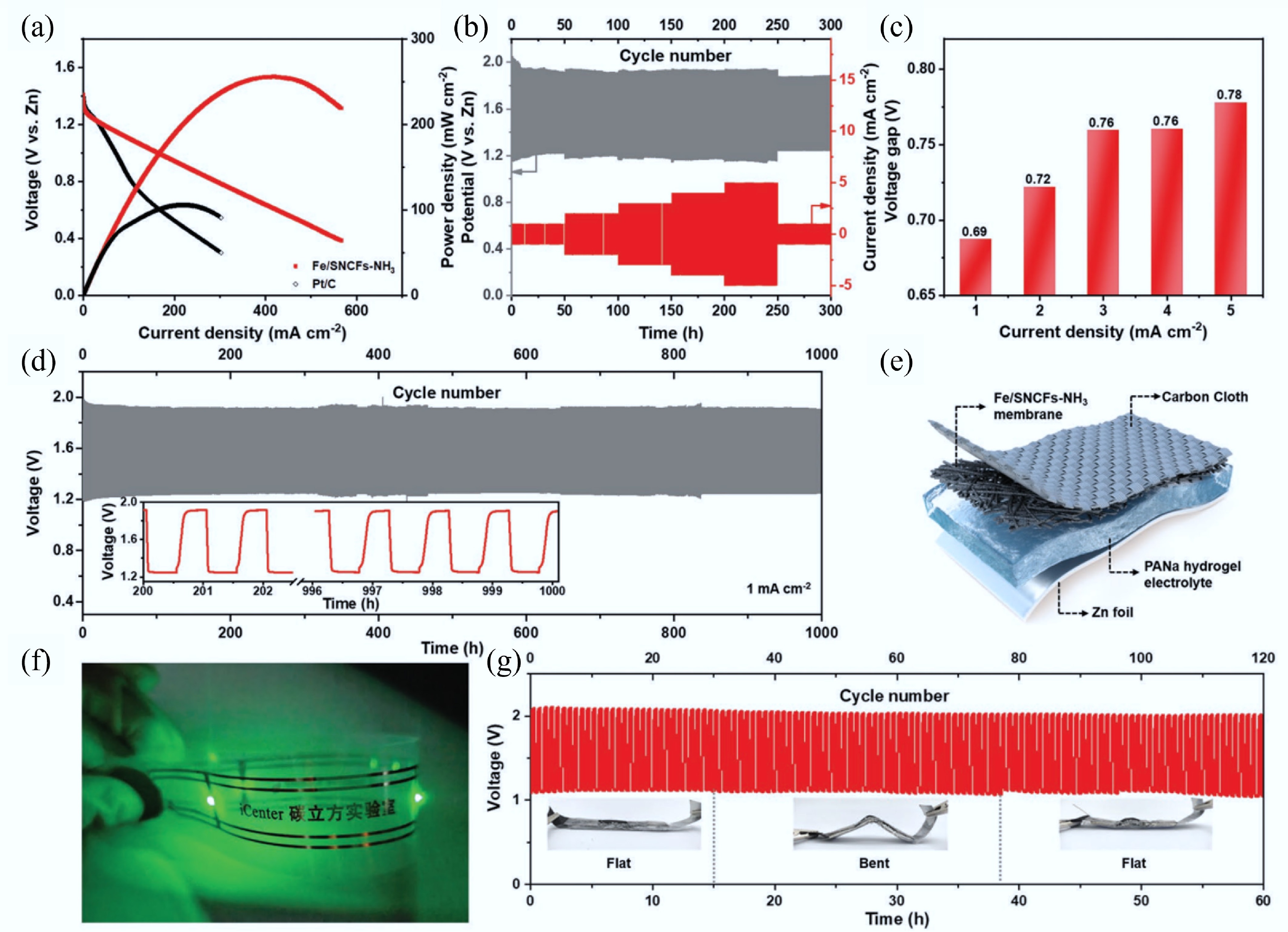

Heteroatom doping can adjust the energy band structure of CMs owing to the differences in the size and the electronegativity of carbon and heteroatoms (N, S, B, P, etc.), thereby enhancing the electron transfer ability[73]. Meanwhile, the introduction of heteroatoms can provide adsorption or catalytic active sites while enhancing hydrophilicity through polar functional groups, thus optimizing the surface chemical characteristics of CMs[74]. Hence, heteroatom-doping has been reported as a versatile modification strategy that remarkably improves the functional capabilities of carbon-based materials, particularly in environmental remediation, chemical transformation processes, and sustainable energy technologies. For example, Chang et al. reported a 3D N/P/S-tri-doped nanoflower with highly branched CNTs bifunctional catalyst by a simple self-assembly pyrolysis method (Fig. 5a)[34]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed that the synergistic effects between the heterogeneous active sites play a vital role in improving the catalytic activity of the catalyst. The simultaneous introduction of N/P/S can facilitate the redistribution of electron density at the catalyst interface. Meanwhile, the appropriate P-doping not only improves the electronic conductivity of the substrate but also promotes the charge transfer in the OER/ORR process. The accelerated durability experiments displayed that there was only a 9 mV decay in E1/2 after 5,000 cyclic voltammetry (CV) cycles for ORR and only a tiny potential change of 8 mV after 5,000 CV cycles for OER. The Co/SP-NC cathode assembled zinc-air batteries exhibited excellent cycling performance (> 280 h). Co/SP-NC showed no X-ray diffraction (XRD) peak change post ORR/OER stability tests, confirming good structural stability. Notably, strong C–Co bonds enhanced structural integrity via dopant anchoring, but higher P-doping reduced stability and cyclic performance. Recently, the enhancement of catalytic activity of CMs via the synergistic effect of heteroatom-doping and transition metal centers has been widely explored for energy and environmental applications. Specifically, Yang et al. synthesized hollow nitrogen-doped carbon capsules supporting iron single-atom sites, which were functionalized with amidoxime groups[35]. Due to the synergistic effect of amidoxime groups and site-isolated FeNx centers, this electrode material can decrease the uranium concentration in seawater to below 0.5 ppb from ~3.5 ppb with an extraction capacity of ~1.2 mg/g within 24 h.

Figure 5.

(a) The preparation process of 3D N/P/S-tri-doped nanoflower with highly branched CNTs bifunctional catalyst[34]. (b) The preparation of the core–shell VMoON@NC 3D electrode architecture. (c) OER polarization curves of the as-obtained catalysts. (d) Tafel plots for ORR and OER catalysts. (e) Overall polarization curves within the ORR and OER potential window of the Mo SACs[33].

Surface modification

-

Surface modification strategies, including functional group grafting, surface metal, or quantum dot loading, have been reported as effective approaches to enhance the properties of CMs, thus propelling their application in energy storage systems and environmental remediation. Roy et al. fabricated carboxyl and amino groups modified GO adsorbent, and its adsorption performance was evaluated for MB and methyl orange (MO)[75]. The results showed that carboxyl-functionalized GO selectively adsorbed MB at pH 9, whereas amino-functionalized GO selectively adsorbed MO at pH 2. Meanwhile, amino/carboxyl functionalized GO extracted 80.9% MO at pH 2 and 92.6% MB at pH 9 from real textile effluent. The removal efficiency of amino- or carboxyl-functionalized GO still maintained 91% MB and 88% MO after five cycles, respectively. This study demonstrated that the reasonable introduction of functional groups into CMs can effectively improve the selectivity for target pollutants.

Beyond functional group modification, the introduction of single-atom catalysts (SACs) presents unprecedented opportunities to boost the catalytic activity of CMs, thus enabling their breakthroughs in energy conversion and environmental governance. Balamurugan et al. reported a bifunctional catalyst featuring single Mo electroactive sites[33]. The catalyst comprised nanoscale (~2.3 ± 0.6 nm) vanadium molybdenum oxynitride cores encapsulated by N-doped carbon shells (Fig. 5b). During pyrolysis, single Mo atoms were released from the core and anchored to electronegative N-dopant species in the graphitic carbon shell. The resulting Mo SACs excelled as active OER sites in pyrrolic-N and as active ORR sites in pyridinic-N environments. Owing to the coexistence of both pyrrolic-N and pyridinic-N dopants in the graphene shell, these Mo SACs exhibited the lowest overpotential, the lowest Tafel slope, and the smallest potential difference in comparison with other catalysts, demonstrating their superior bifunctional (OER and ORR) responses (Fig. 5c–e). Likewise, Poudel et al. designed a unique nanostructure via the coupling of Co single-atoms and Ni NPs on a pyri-N- enriched carbon network substrate[76]. According to DFT calculations, the atomic dispersion of Co single-atoms enables optimal exposure of active sites on the pyri-N dominated multidimensional carbon skeleton, while the synergistic effects with Ni NPs substantially suppress electron delocalization near metallic centers, which promotes the adsorption of oxygen intermediates, thus giving rise to a lower charge transfer barrier. Within this system, this hybrid catalyst presents superior OER/ORR activity.

Carbon-based composites

-

Carbon-based composite materials, mainly involving carbon-carbon, carbon-polymer, and carbon-metal oxide composites, have emerged as a more versatile and efficient alternative for sustainable energy generation and environmental remediation owing to the synergistic advantages of carbon and other functional components. For instance, Jain et al. prepared a hybrid GO/CNTs aerogel of GO and waste-derived CNTs for phenol adsorption[77]. The phenol adsorption efficiency of GO/CNTs aerogel was compared with that of GO, magnetic GO, and GO aerogel. The experimental data showed that the GO/CNTs aerogel exhibited the highest phenol adsorption efficiency of 204 mg/g. The mechanism analysis indicated that the higher adsorption capacity of GO/CNTs was related to the fact that the introduction of CNTs into the GO sheets can increase the interlayer distance of GO sheets, which leads to a higher BET surface area (539.2 m2/g) and richer pores (1.39 cm3/g), and more adsorption active sites as compared to the above GO-based adsorbents.

Due to their high stability and hydrophobic surfaces, CMs are frequently utilized to prepare carbon/metal oxide hybrid catalysts for applications in harsh environments. For instance, to avoid the dissolution or inactivation of first-row transition metal oxides at high proton concentrations, Yu et al. reported a carbon-decorated Co3O4@C electrode with excellent electrocatalytic OER activity and long-term stability in acidic conditions, which was supported by a hydrophobic carbon-based matrix[78]. This robust and scalable electrode exhibited excellent OER performance in 1 M sulfuric acid solution (pH < 0.1), maintaining a 10 mA/cm current density for > 40 h without appearance of performance fatigue. Besides, CMs, owing to their high conductivity and electric double-layer capacitance, are often combined with metal oxides that exhibit high pseudo-capacitance but weak electrical conductivity, thereby forming composites with complementary electrochemical properties. Lin's group fabricated a porous graphene nanosheets-CNTs@MnO2 film by combining porous graphene nanosheets, CNTs, and MnO2 nanosheets[79]. The pores on the graphene surface shorten the diffusion path of electrolyte ions, while the CNTs@MnO2 between graphene layers serve as 'spacers' to prevent graphene aggregation, ensuring interlayer ion transport. Meanwhile, the inclusion of CNTs improved the mechanical and conductive properties, while the MnO2 nanosheets grown on the CNTs underwent redox reactions, giving rise to pseudocapacitance and increasing the specific capacitance of the composite film. Consequently, this film displayed a gravimetric specific capacitance of 320 F/g and a volumetric capacitance of 275 F/cm3 at a current density of 1 A/g in 1 M Na2SO4 solution.

By virtue of their high electrical conductivity, rapid Faraday reactions, and high theoretical capacitance, pseudocapacitive-based polymers are frequently used in combination with double-layer capacitance-based CMs to further improve the overall capacitive performance. Noh et al. reported polyaniline-capped carbon nanosheet (CS) with high conductivity and porosity via vapor deposition polymerization[80]. During the preparation process, vaporized aniline monomers were slowly polymerized on the mesoporous carbon surface and partially filled the carbon pores, improving conductivity. The resultant composite exhibited efficient hybrid energy storage mechanisms integrating electric double-layer capacitance and pseudocapacitive behaviors. In a three-electrode system, the material delivered a high specific capacitance of 469.2 F/g at a current density of 0.5 A/g, which was ~3.7 times higher than that of mesoporous carbon alone.

-

The in vivo behavior and environmental fate of CMs are fundamental aspects that determine their potential risks to both human health and ecological systems. Once released into the environment or introduced into biological systems, CMs may undergo complex processes including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within organisms, as well as transformation, migration, and accumulation in various environmental compartments[81].

The physicochemical properties of carbon nanomaterials, including surface functionalization, size, and structural defects, play a critical role in influencing these ADME profiles[82]. Surface functionalization can influence the in vivo distribution and accumulation of carbon nanomaterials by modulating their interactions with proteins. Specifically, appropriate surface modifications can reduce recognition by the reticuloendothelial system, thereby facilitating their clearance from the body[83]. Aggregation leads to a significant increase in particle size, which alters the ADME characteristics of carbon nanomaterials and results in their accumulation in key organs, exacerbating toxic effects[83]. Small-sized carbon nanomaterials typically exhibit improved dispersibility and stability, which may enhance their biocompatibility. However, their small size also facilitates cellular uptake, potentially increasing the risk of bioaccumulation. In addition, structural defects increase the susceptibility of carbon nanomaterials to attack by hydroxyl radicals, promoting oxidative degradation into smaller fragments[84]. These defect sites may also enhance their binding affinity with essential proteins, disrupting protein structure, and inducing potential toxic responses[32].

Moreover, the ability of carbon nanomaterials to enter food chains and undergo trophic transfer can lead to biomagnification and long-term ecological effects. A comprehensive understanding of these dynamic processes is essential for accurate risk assessment and the development of safer-by-design CNMs[82].

In vivo distribution and translocation

-

CNMs can be introduced into living organisms via multiple pathways, including intravenous injection for biomedical applications, as well as unintentional ingestion or inhalation resulting from environmental exposure. Once internalized, CNMs undergo a series of complex biological processes. However, due to their similarity in chemical composition to biological matrices, directly investigating their in vivo behavior remains a considerable challenge[82]. Among available techniques, labeling strategies remain the most reliable approach for tracking the biological fate of CNMs, including radiolabeling, conjugation with fluorescent probes, and doping with metal oxide NPs[82]. Radiolabeling can be achieved through skeletal incorporation of radioactive isotopes into the carbon framework, which minimizes interference with the physicochemical properties and biological behavior of the nanomaterials[85]. This approach enables long-term and trace-level tracking of their biodistribution and evaluation of their toxicological effects[85]. In addition, post-administration labeling strategies have been developed using DNA-conjugated gold NPs to selectively bind carbon nanomaterials after exposure[86]. This approach improves the accuracy of biodistribution analysis while minimizing the impact of surface modification. Notably, the exposure route of CNMs is a critical factor influencing their ADME characteristics, as different routes expose the CNMs to varying biological environments, such as protein composition and ionic strength, which may affect their initial morphology, surface charge, and colloidal stability, thereby influencing their biological behavior[81].

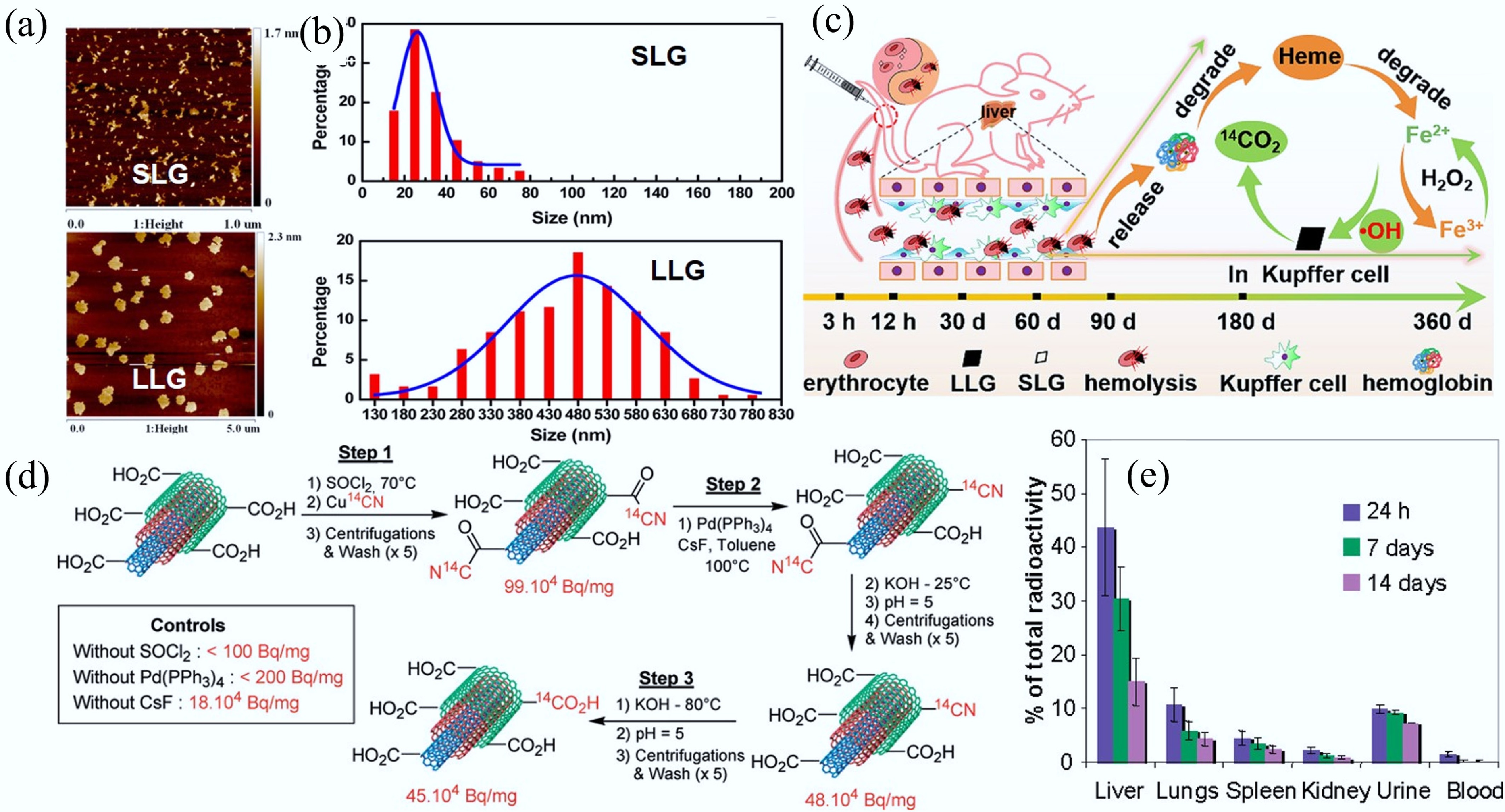

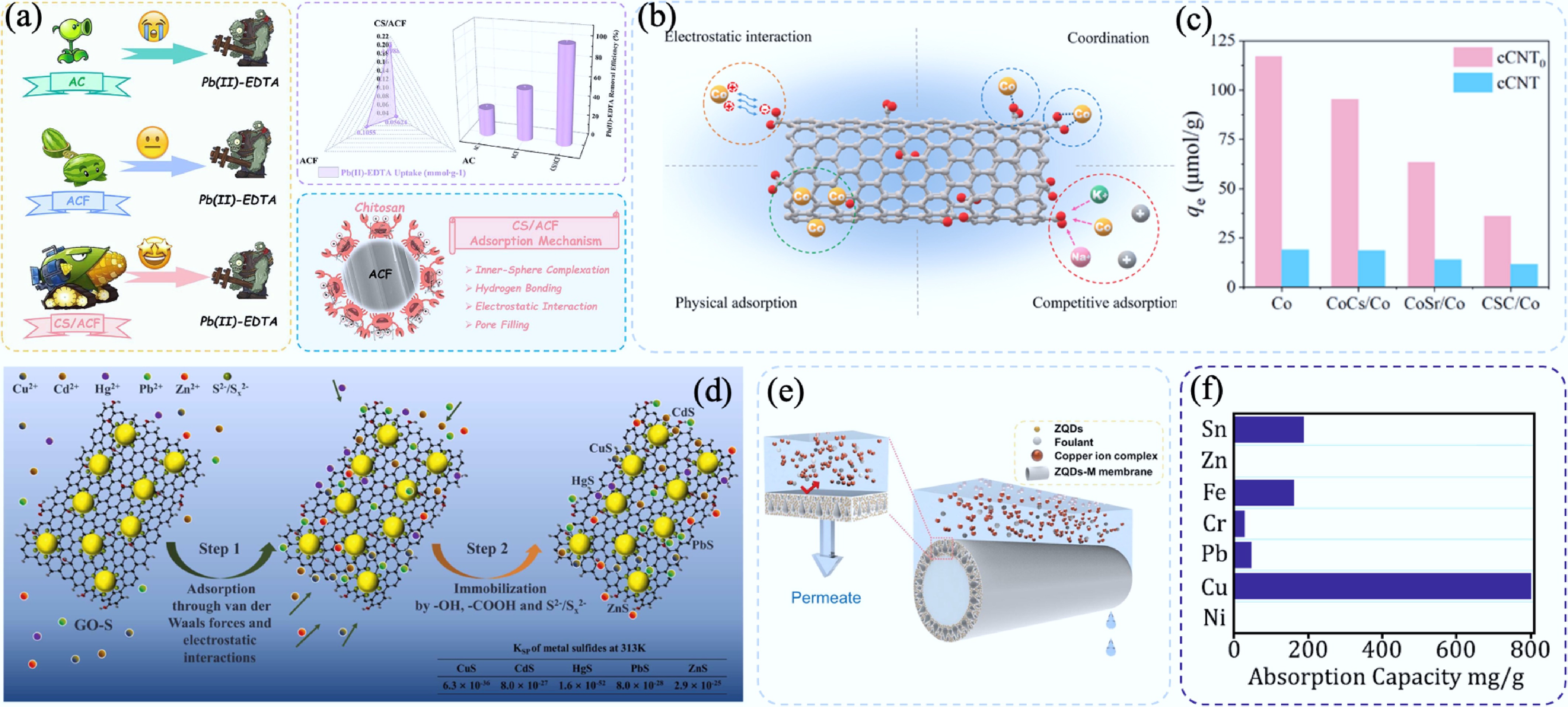

CNMs can enter biological systems through various routes, including intravenous injection, oral administration, and intratracheal instillation. These different exposure pathways can significantly influence the distribution and translocation of CNMs in vivo. For instance, CNMs administered via intravenous injection tend to primarily accumulate in the liver. As the largest solid organ in the human body, the liver receives approximately 13% of the total blood supply and features substantially reduced blood flow velocity, which allows sufficient time for the uptake and transformation of nanomaterials by hepatic cells[87]. The long-term fate of 14C-labeled few-layer graphene in mice following intravenous injection has been studied[85]. The results showed that smaller lateral graphene (SLG) primarily accumulated in the liver, whereas larger lateral graphene (LLG) enhanced the erythrophagocytic activity of Kupffer cells, leading to the elevated intracellular iron levels that initiated Fenton reactions, generating hydroxyl radicals responsible for the oxidative degradation of graphene into CO2 (Fig. 6a–c)[85]. Similarly, the biodistribution of 14C-labeled MWCNTs after intravenous administration indicated the liver as the primary organ of accumulation (Fig. 6d–e)[88]. In addition, orally administered CNMs can be absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract into systemic circulation and subsequently distributed to organs such as the kidneys, stomach, and liver. rGO delivered orally is reported to be distributed across multiple organs[89]. Furthermore, CNMs delivered through intratracheal instillation tend to accumulate in the lungs but may also be transported to the gastrointestinal tract via swallowing or mucociliary clearance, and potentially further redistributed to the blood, liver, and kidneys.

Figure 6.

(a) Representative atomic force microscope topography of SLG and LLG. (b) Histogram of SLG and LLG size distribution. (c) Schematic illustration of the process of LLG triggering the Fenton reaction in Kupffer cells[85]. (d) Preparation process of 14C-labelled multi-walled CNTs. (e) Biodistribution of intravenously administered 14C-labeled multi-walled CNTs at different time points after exposure. Each group contained six animals (n = 6)[88].

The biodistribution of CNMs is predominantly determined by their physicochemical properties, including lateral size and surface functionalization. Studies have shown that smaller graphene nanosheets demonstrate enhanced tissue penetration compared to larger nanosheets. Lu et al. investigated the distribution of graphene with different lateral sizes in zebrafish and found that large-sized graphene predominantly accumulated in the digestive tract (98.3% ± 1.3%), whereas small-sized graphene was detected in both the intestines and the liver, indicating that small-sized graphene could penetrate the intestinal wall to enter epithelial cells and blood[90]. Surface modification also significantly influences in vivo distribution. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coating on GO reduces retention in the liver, lungs, and spleen compared with uncoated GO, which is attributed to steric hindrance that facilitates clearance from these organs[91].

Environmental transport and transformation

-

Soil is a complex mixed system composed of various components and environmental substances, and serves as an important sink for CNMs. Soil properties can significantly influence the aggregation and transport of CNMs. When CNMs penetrate into the soil, they can interact with soil minerals to form nanomaterial-mineral aggregates, leading to their immobilization[92]. Under neutral conditions, GO readily binds to positively charged goethite through electrostatic attraction, promoting heteroaggregation with minerals. Dong et al. investigated the transport and transformation of 14C-labeled graphene in soil. The results showed that red soil with higher iron oxide content exhibited an adsorption capacity for graphene 10.2 times greater than that of black soil[92]. The presence of iron oxides and hydrogen peroxide triggered Fenton reactions that degraded graphene into CO2, facilitating its removal from the soil. Clay minerals can interact with CNMs, thereby affecting their mobility. Three typical clay minerals, namely kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite, inhibit the transport of GO in quartz sand primarily through positively charged edge sites, with kaolinite showing the greatest effect due to its large edge surface area[93]. In addition, ionic composition in soil can influence the transport behavior of CNMs. Xia et al. used quartz sand to study the transport behavior of rGO in porous media. They found that the retention mechanisms of rGO were highly dependent on the type of cations present. Divalent cations (Ca2+) promoted retention through cation bridging, whereas monovalent cations led to retention via deposition in the secondary energy minimum[94].

In aquatic environments, CNMs are subject to various physical, chemical, and photochemical processes that influence their environmental behavior and fate. CNMs exhibit a certain degree of hydrophobicity, and their colloidal behavior is governed by the physicochemical properties of the surrounding medium (such as pH, ionic strength, and natural organic matter), which ultimately influence their aggregation and sedimentation[95]. At lower pH levels, carboxyl groups on the edges of GO become protonated, increasing its hydrophobicity and promoting aggregation. In contrast, under alkaline conditions, the deprotonation of carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups enhances the colloidal stability of GO in solution[96]. In addition to pH, the ionic strength and valency of metal cations also affect the environmental behavior of CNMs. Wu et al. found that divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ were more effective than monovalent Na+ in promoting the aggregation of GO sheets, which was attributed to cross-linking through bridging interactions between divalent cations and edge functional groups on GO sheets[97]. The adsorption of natural organic matter onto CNMs can modify their surface chemistry by introducing hydrophilic functional groups, thereby enhancing their colloidal stability and altering their behavior in aqueous environments[96, 98]. In natural waters, photochemical transformation can be a major environmental fate pathway for CNMs. For instance, C60 exhibits strong light absorption and undergoes photodegradation with a half-life of approximately 19 h, leading to the formation of water-soluble products and eventual mineralization[99]. Similarly, carboxylated CNTs exposed to UVA irradiation undergo decarboxylation and generate surface functional groups and vacancies, which reduce surface potential and colloidal stability[100]. The behavior of CNMs in aquatic environments also influences their toxicity. Hu et al. found that hydration and visible light exposure altered the morphology of graphene, increased its surface negative charge and aggregation, and ultimately reduced its toxic effects on algal cells[101].

In atmospheric environments, CNMs are prone to aging induced by ambient air pollutants, including physical adsorption or condensation of contaminants and heterogeneous reactions with trace gases such as SO2 and NOX[102]. This aging process involves a reduction in disordered carbon and C-H functional groups in CNMs[102]. In a separate study, Liu et al. simulated atmospheric aging by examining the oxidation of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) by ozone and hydroxyl radicals, and found that oxidation facilitated carboxyl functionalization without altering cytotoxic endpoints[103].

Trophic transfer and bioaccumulation

-

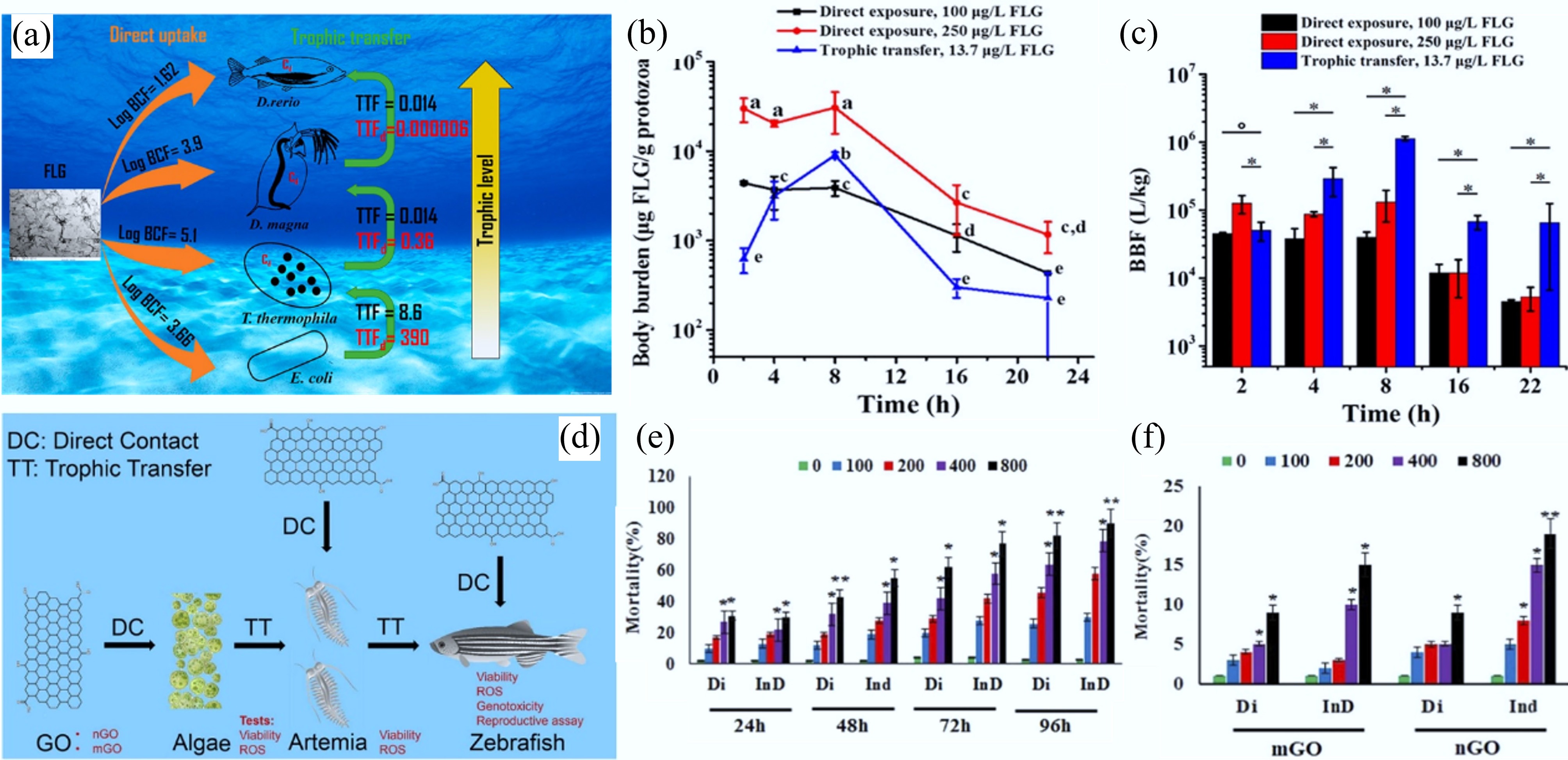

The bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of nanomaterials may pose serious risks to higher trophic level organisms and even human health. Once released into the environment, CNMs may enter biological systems. Unlike conventional chemicals, for which lipid-based accumulation is often used as a proxy for bioaccumulation potential, alternative frameworks for nanomaterials prioritize assessing whether these materials can be adsorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and translocated to other tissues[104]. Current evidence suggests that CNTs are generally not absorbed by the intestinal tract and thus exhibit low bioaccumulation potential[104]. In contrast, graphene has been shown to bioaccumulate in aquatic species such as Daphnia magna and zebrafish. Dong et al. assessed the bioaccumulation of graphene using the bioconcentration factors (BBF). The log-transformed BBF values were 3.66, 5.1, 3.9, and 1.62 for Escherichia coli, Tetrahymena thermophila, Daphnia magna, and Danio rerio, respectively (Fig. 7a), indicating that graphene accumulated in all tested organisms[31]. Notably, they further evaluated trophic transfer using the trophic transfer factor (TTF). In the food chain from E. coli to T. thermophila, the TTF value was 8.6, suggesting a high potential for trophic transfer and highlighting it as a significant pathway for graphene accumulation (Fig. 7a–c)[31]. Similarly, fullerenol NPs exhibit significant biomagnification at lower trophic levels, with a BMF of 3.2 from Scenedesmus obliquus to D. magna, while the BMF from D. magna to D. rerio was less than 1, indicating limited biomagnification at higher trophic levels[105]. In the aquatic food chain (Chlorella vulgaris-Artemia salina-Danio rerio), the toxic effects of GO on Artemia saline and D. rerio were evaluated through both direct exposure and trophic transfer pathways (Fig. 7d–f)[106]. Compared to direct exposure, trophic transfer of Nano-GO resulted in higher mortality in D. rerio, potentially due to the penetration of GO through the intestinal barrier and the subsequent disruption of reproductive function. This suggests that trophic transfer may enhance the bioavailability and toxicological impact of GO in aquatic organisms[106].

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic diagram of the bioaccumulation of 14C-labeled few-layer graphene (FLG) in an aquatic food chain through direct uptake or trophic transfer. (b) Body burden of T. thermophile during the direct exposure to FLG with concentration of 100 or 250 μg/L and trophic transfer from FLG associated E. coli. Each data point represents the mean of three independent replicates, with error bars showing the standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance is determined using Tukey's multiple comparison test. Groups labeled with the same letter do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). (c) BBFs of FLG at different time points during T. thermophila growth in the presence of FLG, administered either directly in the medium (direct exposure) or with FLG-encrusted E. coli (trophic transfer). Bars represent BBFs derived from the mean values of FLG measured in triplicate. Asterisks (*) denote statistically significant differences[31]. (d) Schematic diagram of direct contact and trophic transfer of GO nanosheets in an aquatic food chain. (e) Mortality of Artemia salina caused by Nano-GO. (f) Mortality of D. rerio caused by Micro-GO and Nano-GO (in the Figures, direct ingestion and trophic transfer pathways are denoted as Di and InD, respectively). In (e) and (f), statistical significance is indicated by (*) and (**), corresponding to p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplicate[106].

Factors influencing toxicological effects

-

During the synthesis of CNMs, considerable variation in particle size is often observed. After entering the environment, CNMs may undergo transformations such as enzymatic degradation, photodegradation, the Fenton reaction, and interactions with other substances[107]. Such processes can cause fragmentation, oxidation, and size reduction of CNMs, potentially resulting in distinct toxicological effects.

Physical characteristics

Size

-

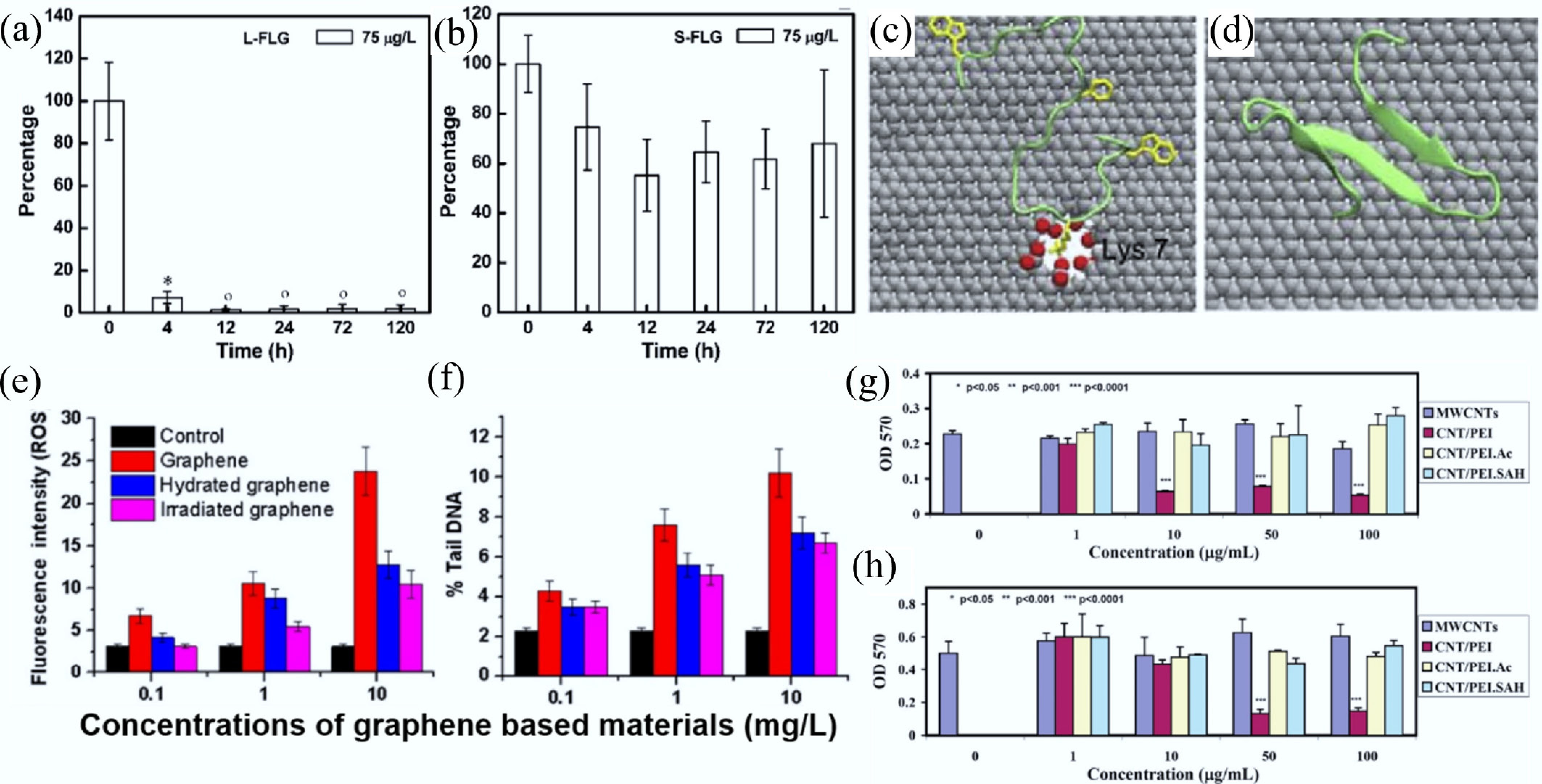

Both the synthesis process and environmental transformations can alter the size of CNMs. Smaller nanomaterials generally exhibit better dispersibility and stability, making them more suitable for intracellular delivery. Reducing the lateral sizes of GO nanosheets through oxidative treatment enhances their biocompatibility and decreases cytotoxicity compared to untreated GO[108]. However, smaller CNMs may also increase the potential for bioaccumulation. Lu et al. investigated graphene nanosheets with different lateral sizes in zebrafish. The results showed that smaller graphene nanosheets more easily crossed the intestinal wall and entered epithelial cells and the blood, which reduced their excretion efficiency (Fig. 8a, b)[90]. The toxicological behavior of CNTs is also influenced by their length[109]. Shorter CNTs (less than 1 μm) are more readily able to penetrate cell membranes[110]. Due to their fibrous nature, CNTs may induce length-dependent effects similar to those of asbestos[111]. When CNTs of varying lengths were administered into the pleural cavity, longer CNTs induced acute inflammation, whereas shorter CNTs were effectively cleared[112]. In the case of fullerenes, smaller nano-C60 particles exhibit enhanced DNA polymerase inhibition and higher cytotoxicity, indicating a size-dependent toxic effect[113].

Figure 8.

Depuration of (a) Larger few-layer graphene and (b) Smaller few-layer graphene in zebrafish. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5). Statistical significance was determined by Tukey's test (p < 0.05). Symbols (°) and (*) indicate values not significantly or significantly different from zero, respectively[90]. Representative contact configuration of YAP65WW protein adsorption onto (c) defective graphene and (d) ideal graphene surfaces (carbon, silver; oxygen, red; hydrogen, white). The critical residue Lys-7 involved in the binding process is labeled[114]. Effects of hydration and visible-light irradiation on the reduction of (e) oxidative stress and (f) DNA damage induced by pristine graphene. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and error bars represent mean ± SD[101]. MTT assay results of cell viability for (g) FRO (a human thyroid cancer cell line) and (h) KB (a human epithelial carcinoma cell line) after 24 h treatment with differently functionalized MWCNTs. Each treatment was performed in triplicate, and error bars represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using the ANOVA test and is indicated by (*), (**), and (***) for p < 0.05, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively[123].

Structural defects

-

Structural defects in nanomaterials may arise during synthesis or as a result of environmental transformation. These defects can alter the local electron density and mechanical properties of the nanomaterials. Graphene-based nanomaterials with appropriately sized defects have been applied in gas separation and seawater desalination[114]. Local defects in graphene can induce the unfolding of the YAP65WW-domain. Protein residues are tightly anchored to the defect sites through favorable electrostatic interactions, which constrain the protein conformation and ultimately lead to domain denaturation (Fig. 8c, d)[114]. In addition, Muller et al. found that the acute pulmonary and genotoxic effects of CNMs were closely associated with their structural defects. High-temperature annealing, which can repair such defects in CNMs, significantly reduces their toxicity. For MWCNTs, the extent of structural defects was positively correlated with their adhesion to cell membranes[115]. Dangling carbon bonds at defect sites served as reactive sites for cell membrane interactions, potentially disrupting membrane integrity and inducing cytotoxic effects[116].

Surface functionalization

Surface functional groups

-

When CNMs are released into the environment, they may undergo transformations through redox reactions, photochemical processes, and/or hydrolysis, resulting in the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups on their surfaces[107,117]. Such surface modifications can alter the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of CNMs and consequently affect their biological toxicity. Graphene oxidation under hydration and light irradiation introduces oxygen-containing functional groups, which increase the negative surface charge and promote aggregation, thereby significantly reducing the oxidative stress and nanotoxicity of graphene to algal cells (Fig. 8e, f)[101]. In contrast, studies on MWCNTs showed that oxidation by ROS increased surface oxygen functional groups, which enhanced cellular uptake and led to reduced cell proliferation, indicating increased cytotoxicity[117,118]. Pérez-Luna et al. further compared three types of surface-modified MWCNTs (pristine, oxidized, and alkylated) and examined their interactions with giant unilamellar vesicles. The results demonstrated that these interactions were predominantly driven by hydrophobic forces, indicating that the type of surface functional group may modulate hydrophobicity[119]. In addition to environmental transformations, intentional functionalization methods such as covalent modifications (including hydroxylation and carboxylation) and noncovalent modifications (including hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions) have been widely applied to improve the performance of CNMs. However, the potential toxicological consequences of such modifications should not be overlooked. Huang et al. investigated the toxic effects of carboxylated, aminated, and hydroxylated graphene on Daphnia magna. They found that aminated and hydroxylated graphene disrupted protein synthesis and function by interfering with transcription and translation pathways, leading to toxic effects[120]. In contrast, surface modification using biocompatible polymers (e.g., PEG and dextran) has been shown to reduce direct interactions with cell membranes and thus mitigate cytotoxicity[121].

Surface charge modification

-

The interaction between CNMs and cell membranes can induce cytotoxic effects, as nanomaterials may penetrate and be internalized through the negatively charged lipid bilayer. Therefore, the surface charge of CNMs influences their binding and internalization by the cell membranes, thereby affecting their toxicity. Studies have shown that CNMs with positive or neutral surface charges are more likely to associate with cell membranes[122]. For example, Shen et al. investigated the cytotoxicity of MWCNTs with different surface charges, and those with positive charges exhibited toxic effects even at low concentrations. This may be attributed to the strong interaction between positively charged MWCNTs and negatively charged cell membranes (Fig. 8g, h)[123]. Similarly, positively charged GO nanosheets have been reported to promote mitochondrial fission and induce cell death through apoptosis and autophagy[124].

Nanocomposite

Metal and metal oxides

-

CNMs possess a large SSA, making them excellent carriers for metals and metal oxides by providing abundant binding sites. This facilitates the formation of composite materials with enhanced catalytic, antibacterial, and electrochemical activities, thereby expanding the application scope of CNMs[125]. However, such modifications can also alter their toxicological profiles. Yin et al. investigated six rGO-based composites (rGO-Au, rGO-Ag, rGO-Pd, rGO-Fe3O4, rGO-Co3O4, and rGO-SnO2) and their toxic effects on algae. The results indicated that soluble metal ions released from the embedded metals or metal oxides could damage cell membranes and trigger oxidative stress, resulting in increased cytotoxicity[125]. Similarly, the Pb3O4@MWCNTs nanocomposite exhibited higher toxicity toward environmental bacteria compared to Pb3O4 or MWCNTs alone, likely due to the easier release of Pb2+ from the Pb3O4@MWCNTs[126]. In contrast to these findings, Valimukhametova et al. developed a series of lightly metal-doped (iron oxide, silver, thulium, neodymium, cerium oxide, cerium chloride, and molybdenum disulfide) NGQDs, which exhibited excellent fluorescence imaging capabilities under visible and near-infrared (NIR) light. Importantly, their low metal doping levels contributed to relatively low cytotoxicity[127]. Therefore, the dual impact of enhanced functionality and altered toxicity underscores the need for balanced design strategies when developing metal-modified CNMs.

Polymers

-

Polymer modification improves the dispersibility and stability of CNMs and has been widely studied in drug delivery and bioimaging. PEG, chitosan, and cellulose derivatives are commonly used for the functionalization of CNMs. It has been reported that PEGylated graphene nanosheets mainly accumulate in the liver and spleen after intravenous administration. They are subsequently excreted through the kidneys and feces. Long-term studies in mice showed no significant toxic effects[128]. Similarly, the incorporation of chitosan-functionalized CNTs into poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels result in a composite material. The results showed that the composite did not induce oxidative stress or cytotoxicity in intestinal cells, suggesting favorable biocompatibility[129]. Carboxymethyl cellulose is a cellulose derivative with tunable hydrophilicity, surface activity, and thickening properties. It has been used to modify hydrophobic carbon dots (CDs) to enhance their hydrophilicity. Due to the lipophilic nature of CDs, unmodified CDs can cross cell membranes and accumulate in lipid compartments, leading to oxidative stress and an inflammatory response. After modification with carboxymethyl cellulose, CDs were found to promote cell proliferation and increase cell viability[130]. Collectively, these findings suggest that polymer modification is beneficial for modulating the biological interactions of CNMs and enhancing their biosafety.

Mechanisms of carbon nanomaterials toxicity

Physical damage

-

Graphene-based CNMs, such as graphene, GO, and rGO, are 2D materials characterized by sharp edges. The physical interactions between graphene-based nanosheets and cell membranes are significant factors contributing to their cytotoxicity. The sharp edges of graphene-based nanosheets can insert into and cut bacterial cell membranes, causing membrane damage. Guo et al. investigated the neurotoxicity of graphene with different surface functionalizations and found that all functionalized graphene induced neurotoxic effects through physical disruption of membrane lipids[131]. In addition, the fibrous structure of CNTs enables them to directly pierce the membranes of Escherichia coli, leading to bacterial death[132]. Purified SWCNTs exhibited strong antibacterial activity, primarily attributed to membrane damage caused by direct contact between SWCNTs and bacterial cell membranes, which induced cytotoxic effects[133].

Oxidative stress

-

In addition to physical damage, a second major mechanism by which carbon nanomaterials induce toxicity is oxidative stress. Exposure to CNMs often leads to excessive ROS generation, which disrupts the antioxidant defense system and eventually induces oxidative stress responses. This oxidative imbalance results in damage to critical biomolecules such as proteins, DNA, and lipids, which can subsequently induce apoptosis, necrosis, or developmental toxicity[134,135]. The degree of oxidative stress is significantly influenced by the surface functionalization, physicochemical properties (e.g., size, metal impurities), and intracellular accumulation of CNMs[109,136]. Specifically, CNTs and graphene-based nanomaterials have been shown to induce excessive ROS generation upon interacting with cells, accompanied by reduced antioxidant enzyme activity. This can cause lipid membrane damage, DNA fragmentation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disruption of cellular metabolism[137]. Additionally, photoactive nanomaterials such as nano-C60 aggregates can further induce ROS production through light-driven photochemical reactions, resulting in lipid peroxidation and increased cytotoxicity[138]. Together, these findings underscore the central role of ROS-mediated oxidative stress as a common toxicological pathway for CNMs.

Genotoxicity of carbon nanomaterials

-

Another critical toxicological mechanism associated with carbon nanomaterials is genotoxicity, which involves damage to chromosomes or DNA. The large surface area and surface charge of CNMs may contribute to their genotoxic potential, leading to DNA damage. GO nanosheets administered via intravenous injection have been shown to induce mutations in mice[139]. Although GO cannot penetrate the cell nucleus, it may still interact with DNA during mitosis, when the nuclear envelope temporarily disassembles, thereby increasing the risk of chromosomal aberrations[137,140]. The aromatic carbon rings of GO can bind to DNA base pairs through π–π stacking interactions, causing distortion at the DNA termini and contributing to genetic instability[141]. Additionally, carbon nanomaterials may induce genotoxicity indirectly through oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and cell cycle disruption, all of which can lead to DNA damage[137] and promote the generation of ROS. For instance, CNTs can stimulate inflammatory cells to produce ROS[142], resulting in oxidative DNA damage such as oxidation of DNA bases and strand breaks, as well as lipid peroxidation-mediated DNA adduct formation, all of which are associated with genotoxic effects[109, 143].

Inflammatory response

-