-

In this era of rapid industrialization and urbanization, the population has experienced an unprecedented increase, resulting in a corresponding rise in water demand[1]. Industrial activities contribute to about 20% of freshwater being withdrawn, which is either treated and reused, or disposed of in a sustainable manner. However, without proper management, wastewater containing several synthetic chemical contaminants could make their way into natural water bodies[2]. Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is one of many contaminants that have infiltrated the water bodies and soils through industrial discharge, agricultural activities, and other improper disposal practices[3]. Its presence has been detected in rainwater, surface water, drinking water, sediments, soil, and food, posing a risk of causing detrimental impacts on the environment[4]. Therefore, identifying effective strategies for its removal is imperative. Several methods have been explored to facilitate PCP remediation, such as electrocatalytic treatment[5], combined anaerobic-aerobic treatment[4], phytoremediation[6], bioaugmentation[7], and adsorption. Adsorption is one of the oldest and most widely employed methods due to its numerous benefits, including lower operational costs, sustainability, and fewer secondary pollutant productions[8]. Among the various adsorbents, activated carbon is considered the industry standard, as it can be easily modified to enhance the adsorption capacity; however, it is difficult to separate after use, and is not a cost-effective option[9]. Therefore, the application of biosorbents derived from biomass waste has gained significant attention due to their cost-effectiveness and sustainability[10]. The use of biosorbents not only addresses the immediate challenge but also promotes a circular economic approach by reducing the burden on landfills and preserving natural ecosystems[11].

Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is a thermochemical process that converts waste biomass into hydrochar (HC), which can be engineered with desirable surface and structural properties for use as a biosorbent. The characteristics of hydrochar, such as surface area, porosity, and functional groups, can be tuned by selecting appropriate biomass feedstocks, and controlling HTC conditions. Flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust, due to their abundance in nature and favorable physicochemical properties, have been extensively explored by the scientific community. Sourced from the agricultural and forestry sectors, these biomass wastes have various benefits when valorized for wastewater treatment[12]. The pore structure and lignin content of flax shives are highly favorable for the adsorption of heavy metals, dyes, and other pollutants[13]. Similarly, the hydrochar derived from eucalyptus is advantageous due to its stability and high surface area, which enables efficient adsorption of organic contaminants and heavy metals[14]. Modified hydrochar, especially those doped with metal oxides such as iron, has a higher surface area, additional reactive functional groups, enhanced porosity, easy regenerative properties, and reusability. More importantly, it also possesses magnetic properties for easy separation[15,16]. Several studies have investigated hydrochars derived from flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust due to their availability and carbon-rich composition[17,18]. These studies mainly examined non-magnetic hydrochar for the removal of pollutants such as dyes and heavy metals. However, the synthesis of magnetic hydrochar from these biomass materials remains unexplored, particularly those doped with iron, which can impart magnetic properties for easy separation, and enhance adsorption through redox-active surface functionalities.

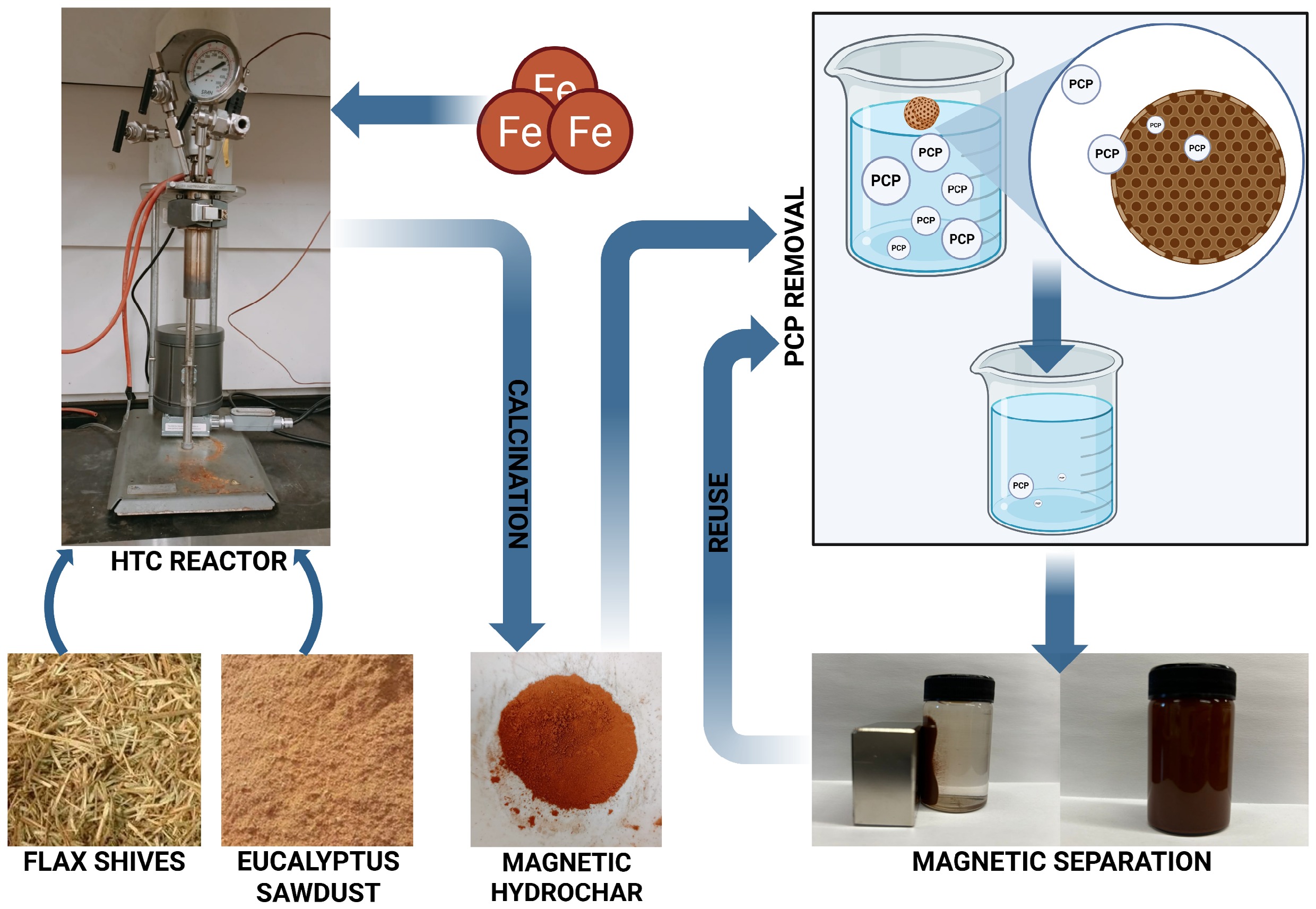

In this study, iron-based biosorbents were synthesized from flax shives, and eucalyptus sawdust through HTC. Ferrous sulphate heptahydrate (Fe2SO4•7H2O) and anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3) were incorporated to introduce magnetic properties to the hydrochar. The main objectives of this investigation were: 1) to synthesize magnetic hydrochars derived from flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust via hydrothermal processes; 2) to characterize the physicochemical properties of the resulting hydrochars; and 3) to evaluate their efficacy in removing PCP from wastewater and their reusability potential.

-

Ferrous sulphate heptahydrate (Fe2SO4•7H2O, ≥ 99%) and anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3, 98%) were purchased from Acros Organics and Thermo Scientific, respectively. NaOH pellets were acquired from Anachemia. Acetone (≥ 99.5%) and PCP (97%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All the reagents used are of analytical grade and were used as provided, without any further modifications. Flax shives were collected from TapRoot Farms, Nova Scotia, Canada, and eucalyptus sawdust was provided by the Laboratory of Solid Residues and Composites at São Paulo State University, Brazil. The obtained flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust were ground and sieved in a 125 mm mesh. The findings of proximate and biochemical analysis[19−22] of the raw materials are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Proximate and biochemical analysis of flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust

Biomass Flax shives Eucalyptus sawdust Proximate analysis (wt%) Moisture 1.04 ± 0.15 1.36 ± 0.04 Volatile 95.99 97.64 Fixed carbon 2.48 1.91 Ash 1.78 ± 0.25 0.72 ± 0.27 Biochemical analysis (wt%) Cellulose 45 ± 5.92 42 ± 5.38 Hemicellulose 29.67 ± 4.91 27 ± 5.01 Lignin 25 ± 1.82 31 ± 2.45 Hydrochar synthesis

-

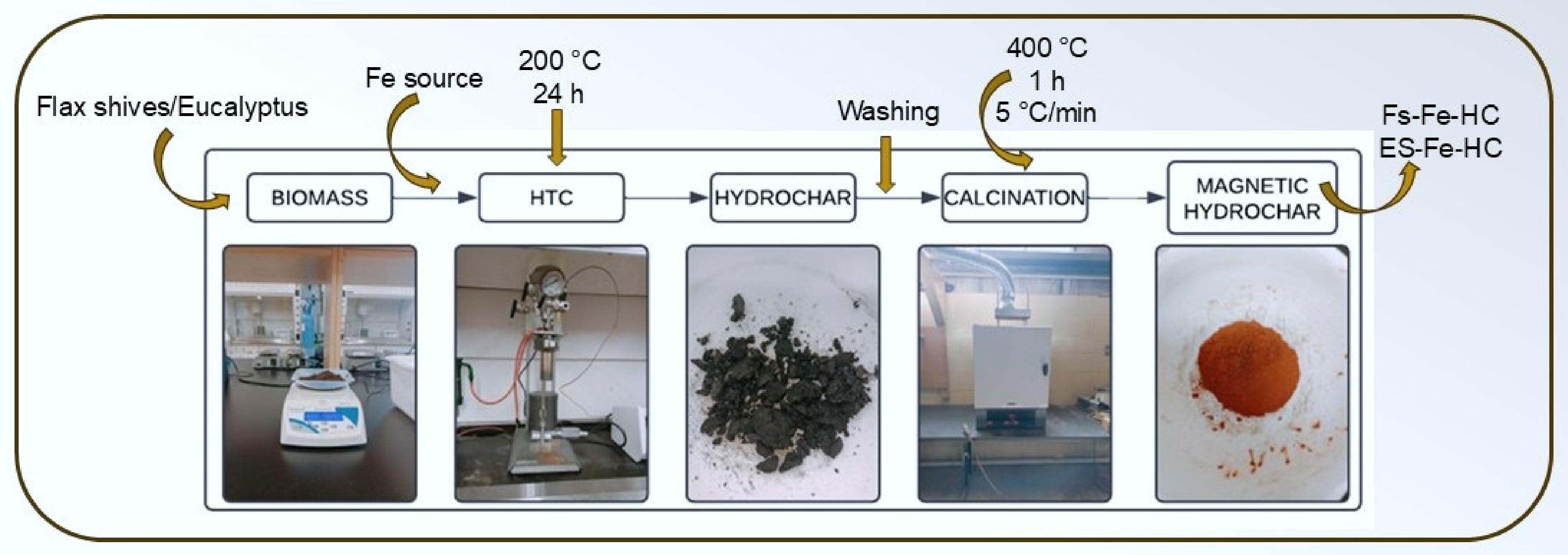

Magnetic hydrochar was synthesized using two representatives for agricultural and forestry: flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust (Fig. 1). The ground and sieved biomass was mixed with distilled water (1:8). Following this, Fe2SO4•7H2O (9.95 g/L), and anhydrous FeCl3 (19.49 g/L) were added to the mixture. After dispersing the iron salts, 0.072 mL of 1 M NaOH was introduced while the mixture was stirred using an electromagnetic stirrer for 30 min. The resulting suspension was transferred to an HTC reactor, where it was thermally treated at 200 °C for 24 h in a nitrogen-purged inert atmosphere[23]. After cooling, the obtained hydrochar was washed with distilled water and soaked in acetone for 12 h. It was then filtered, rinsed with deionized water, and dried in an oven at 105 °C for 6 h. The dried hydrochar was subsequently calcined in a muffle furnace at 400 °C for 1 h, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. The final products were labelled FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC.

Characterization of synthesis FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC

-

Several processes were employed for determining the physical and chemical characteristics of hydrochar. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, PerkinElmer Spectrum 10.5.2) was used to study the functional groups present on the surface of hydrochar before and after iron doping over a wavelength range of 400–4,000 cm–1. The crystal structure of the synthesized hydrochar was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Siemens D500, Germany) under Cu-Kα radiation at a 2θ range of 5–80°. The surface morphology and structure were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Oxford Instruments). The elemental distribution was studied by electron diffraction spectroscopy (EDS). To study the bonds formed on the surface of the hydrochar and their binding energies, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, MultiLab ESCA 2000, UK) was employed. The magnetic properties of the hydrochar were studied by a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Lakeshore, 8600). The specific surface area, pore diameter, and volume were analyzed using a Microtrac MRB BELSORP-Mini X Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analyzer. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Agilent 5110) was used to study whether any iron introduced during synthesis was leached during or after treatment.

Batch experiments

-

Experiments were performed to investigate how reaction conditions affect the removal of PCP using FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC. The adsorbent dose was varied from 0.2 to 0.8 g/L for FS-Fe-HC and from 0.1 to 0.5 g/L for ES-Fe-HC. The effect of pH was studied in the range of 4 to 10, while the initial PCP concentration varied from 4 to 14 mg/L for both hydrochars. The effect of contact time was studied at various time intervals, ranging from 5 to 1,680 min. The collected samples were filtered through a 0.45 µm pore size filter, and the concentration of PCP was measured by using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 214 nm. A study was conducted to evaluate the recyclability of both FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, involving five adsorption cycles where the same hydrochar was used for PCP removal and subsequently regenerated in 5% methanol. The point of zero charge (pHPZC) was determined using the method as described in our previous study[24]. The percentage removal (R, %) of PCP was determined by using the following Eq. (1):

$ R\left({\text{%}}\right)=\dfrac{{C}_{0}-{C}_{e}}{{C}_{0}}\times 100 $ (1) where, C0 is the initial PCP concentration in mg/L, and Ce is the equilibrium PCP concentration in mg/L.

The data collected from adsorption experiments were fitted to the non-linear pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models. Non-linearized forms of Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models were applied to the PCP adsorption data, as described in our recent study[25].

-

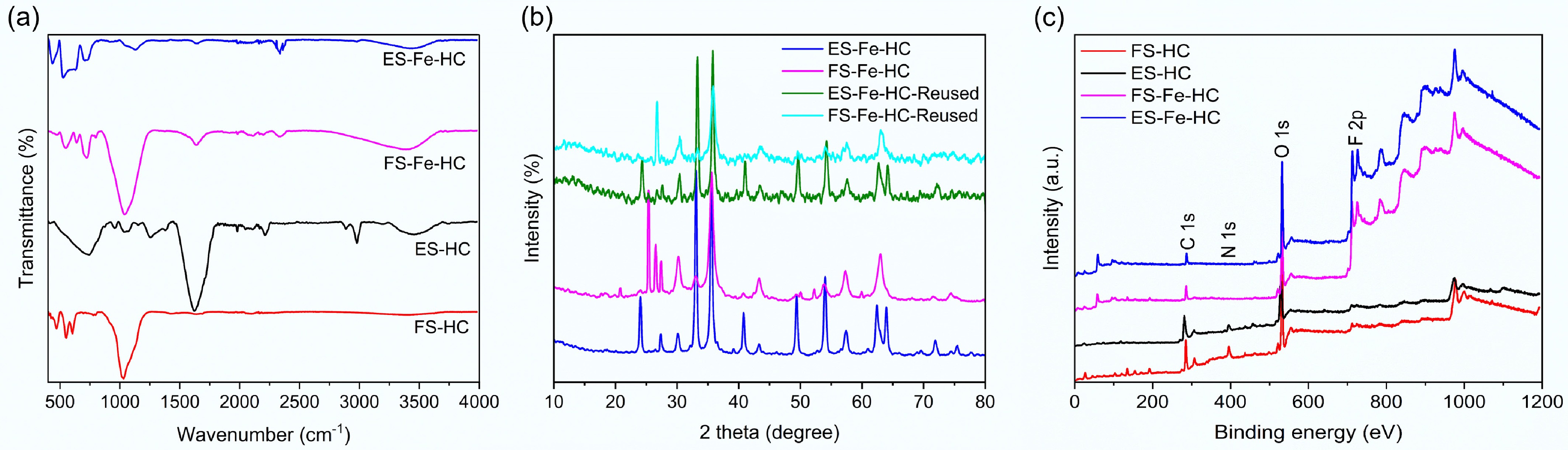

FTIR was employed to identify the surface functional groups present in the hydrochar samples. For the FS-HC sample, prominent absorption peaks were detected at 1035.29, 607.66, 553.49, and 472.23 cm−1. These peaks correspond to aliphatic C–O stretching, Fe3O4, Fe–O vibration, and Si–O–Si bonds, respectively (Fig. 2a)[25−27]. After iron doping, FS-Fe-HC samples displayed additional peaks at 3,397.54, 2,335.43, 1,637.76, and 1,044.32 cm−1, which are attributed to –OH stretching, C=O stretching (from ketones and aromatics), and –COOH functional groups[28]. Notably, Fe–O and Si–O–Si vibrations were still evident at 548.56 and 472.23 cm−1, indicating that partial original functionalities were retained after doping[26].

Similarly, the FTIR spectrum of ES-HC (Eucalyptus Sawdust Hydrochar) showed –OH stretching vibration at 3,442.68 cm−1, along with several peaks that correspond to various surface functional groups (Fig. 2a)[28]. Peaks at 2,978.93, 2,218.88 cm−1, and within the range of 1,793.09–1,696.96 cm−1 represent the aliphatic –CH2 stretches, C–N bonds, and carbonyl (C=O) groups, respectively[23,28]. Additional peaks at 1,596.96–1,411.82, 1,255.27, 1,030.37, and 594.22–503.30 cm−1 indicate the presence of aromatic C=C stretching (lignin-related), ether linkages (C–O–C), carboxylic acid groups (–COOH), and Si–O–Si bending vibrations[28]. A final band in the range of 453.70–435.14 cm−1 was assigned to alkyl halide groups. After iron doping, the ES-Fe-HC spectrum showed that the retained functional groups were similar to those of FS-Fe-HC, including –OH stretching (3,447.60 cm−1), C–N bonds (2,362.52 and 2,340.36 cm−1), Si–O–Si bending (526.40 cm−1), and alkyl halides (436.11 cm−1)[25,29]. Importantly, no new significant peaks were observed following iron doping, indicating that the major structural features remained largely unchanged.

XRD analysis was conducted to investigate the crystalline phases present in FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, with the findings presented in Fig. 2b. In FS-Fe-HC, the diffraction peaks at 25.49, 26.63, and 27.43° (2θ) correspond to graphitized or amorphous graphite-like carbon structures, which may also include contributions from residual cellulose[30]. Peaks at 30.31, 33.11, 35.56°, and within the range of 52.36–59.89° indicate the presence of crystalline Fe2O3 phases, while a peak at 63.03° confirms the presence of zero-valent iron (Fe0)[31]. In ES-Fe-HC, the peaks at 24.01 and 27.43° suggest disordered graphitic carbon with some cellulose-derived structures[30]. The peaks at 30.14, 33.03, and 35.56° are again attributed to Fe2O3, while those at 40.82 and 49.48° correspond to turbostratic carbon—a characteristic form of disordered graphite in hydrothermal carbons. Further peaks for Fe2O3 appear at 54.11, 57.53, and 62.60°, and a peak at 64.08° indicates the formation of Fe0, suggesting partial reduction during HTC[31,32]. Overall, these patterns confirm the coexistence of iron oxide and disordered carbon phases. After one adsorption cycle, the XRD patterns of FS-Fe-HC-Reused and ES-Fe-HC-Reused remained largely unchanged. The key peaks for Fe2O3, graphitic/turbostratic carbon, and Fe0 were retained, showing only minor variations in intensity. This structural stability highlights the reusability of the hydrochar without significant crystalline degradation.

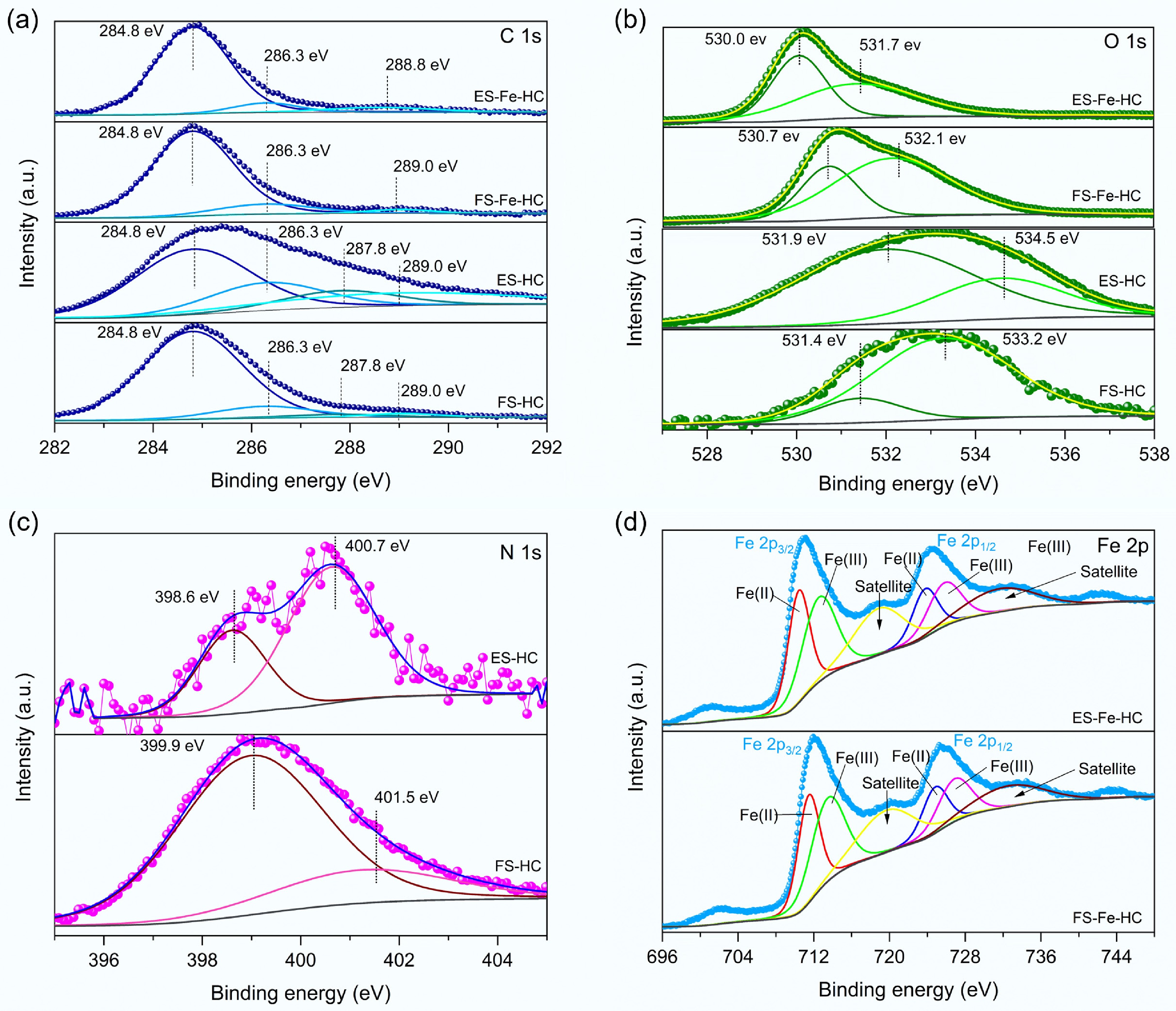

The XPS survey spectra (Fig. 2c) of the hydrochar revealed the presence of four main elements: carbon (C 1s), oxygen (O 1s), nitrogen (N 1s), and iron (Fe 2p), with binding energy features indicative of their chemical states. All samples exhibited a dominant C 1s (Fig. 3a) peak at 284.8 eV, which corresponds to non-oxygenated carbon atoms, such as C–C and C=C bonds[33]. Peaks at 286.3 and 287.7 eV were attributed to C–O–C (ether) and C=O (carbonyl) groups, respectively, while the peak at 289.0 eV was assigned to O–C=O (carboxyl) functionalities. The presence of these oxygenated groups suggests that partial oxidation of biomass occurred during the HTC process[33]. In FS-HC and ES-HC, the O 1s spectra (Fig. 3b) displayed peaks at approximately 531.4 and 533.2–534.5 eV, which were attributed to lattice oxygen and surface-adsorbed oxygen, respectively[34]. After iron doping, FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC exhibited O 1s peaks at 530.0–530.7 eV (adsorbed oxygen) and 531.7–532.1 eV (lattice oxygen), indicating interactions between oxygen and iron oxide surfaces. The slight shift towards lower binding energies indicates enhanced metal–oxygen interactions due to iron incorporation[24]. The N 1s spectra (Fig. 3c) of ES-HC displayed peaks at 398.6 and 400.7 eV, corresponding to pyridinic and pyrrolic nitrogen species, respectively. In contrast, the FS-HC showed peaks at 399.9 and 401.5 eV, aligned with pyrrolic and graphitic nitrogen configurations[35]. Although these nitrogen functionalities are present in low concentrations, they may contribute to the adsorption properties and reactivity of the hydrochar. The Fe 2p spectra (Fig. 3d) of FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC showed characteristic peaks at 712.32 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and 725.85 eV (Fe 2p1/2), confirming the presence of iron species. Deconvolution identified Fe2+ at 710.3 and 723.49 eV and Fe3+ at 718.3 and 726.13 eV, which indicates the formation of mixed-valence iron oxides, such as magnetite (Fe3O4), during the hydrothermal process. This coexistence of valence states is consistent with the enhanced redox behaviour observed in iron-doped carbonaceous materials[36].

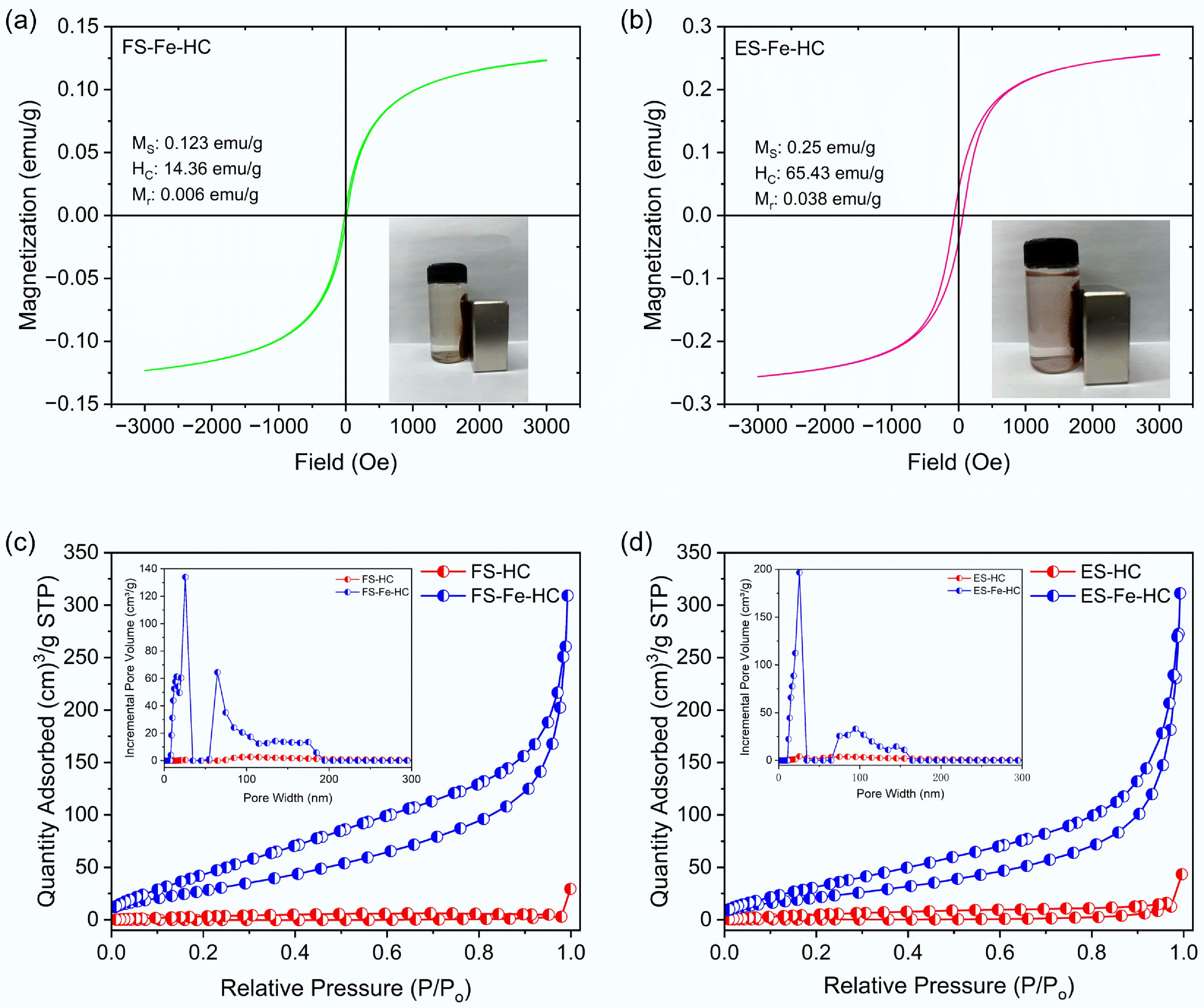

The VSM analysis was employed to analyze the magnetic properties of the synthesized hydrochar. Saturation magnetization (MS) refers to the state where FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC may attain their maximum magnetization as the external magnetic field increases[37]. MS can serve as a surrogate indicator for predicting the separability of hydrochar from the liquid phase using permanent magnetic bars[38]. For FS-Fe-HC (Fig. 4a), the calculated values of MS, coercivity (HC), and remanence (Mr) were 0.123 emu/g, 14.36 Oe, and 0.006 emu/g, respectively. For ES-Fe-HC (Fig. 4b), the calculated values of MS, HC, and Mr were 0.2555 emu/g, 65.43 Oe, and 0.038 emu/g, respectively. The low remanence values of both hydrochars indicate that FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC retain low residual magnetism when the external magnetic field is eliminated[39]. Despite the low MS values, both hydrochars were rapidly separated from the bulk liquid within a few seconds after the adsorption reaction when an external magnet was applied.

The textural properties of the hydrochar were evaluated using BET analysis, with the results summarized in Table 2. A significant increase in surface area and pore structure was noted following iron modification of the hydrochar.

Table 2. BET analysis of FS-HC, ES-HC, FS-Fe-HC, and ES-Fe-HC

Biomass BET surface area (SBET) (m2/g) Total pore volume (cm3/g) Average pore diameter (nm) FS-HC 4.3803 0.0269 12.29 ES-HC 0.8796 0.0548 125.52 FS-Fe-HC 118.49 0.4271 7.21 ES-Fe-HC 87.74 0.4393 10.01 The surface area of ES-HC and FS-HC was found to be extremely low, measuring 0.8796 and 4.3803 m2/g, respectively, with corresponding total pore volumes of 0.0548 and 0.0269 cm3/g. Their large average pore diameters of 125.52 and 12.29 nm indicate a dominance of macroporous and mesoporous structures. This observation aligns with existing literature on hydrochar derived from lignocellulosic biomass that underwent limited activation during hydrothermal carbonization[40,41]. After calcination, there was a significant enhancement in surface characteristics. FS-Fe-HC exhibited the highest BET surface area of 118.49 m2/g, followed by ES-Fe-HC with 87.74 m2/g. Correspondingly, both hydrochars showed higher pore volumes (0.4271−0.4393 cm3/g) and reduced average pore diameters (7.21−10.01 nm), which indicates the formation of well-developed mesopores (Fig. 4c, d). This enhancement can be attributed to the catalytic effect of iron salts, which promote pore formation during the carbonization process and prevent structural collapse by stabilizing intermediate carbon structures[42−44]. Such improvements in textural properties are critical for adsorption-based applications, as higher surface area and increased mesoporosity enhance the availability of active sites and facilitate mass transfer in aqueous environments[45].

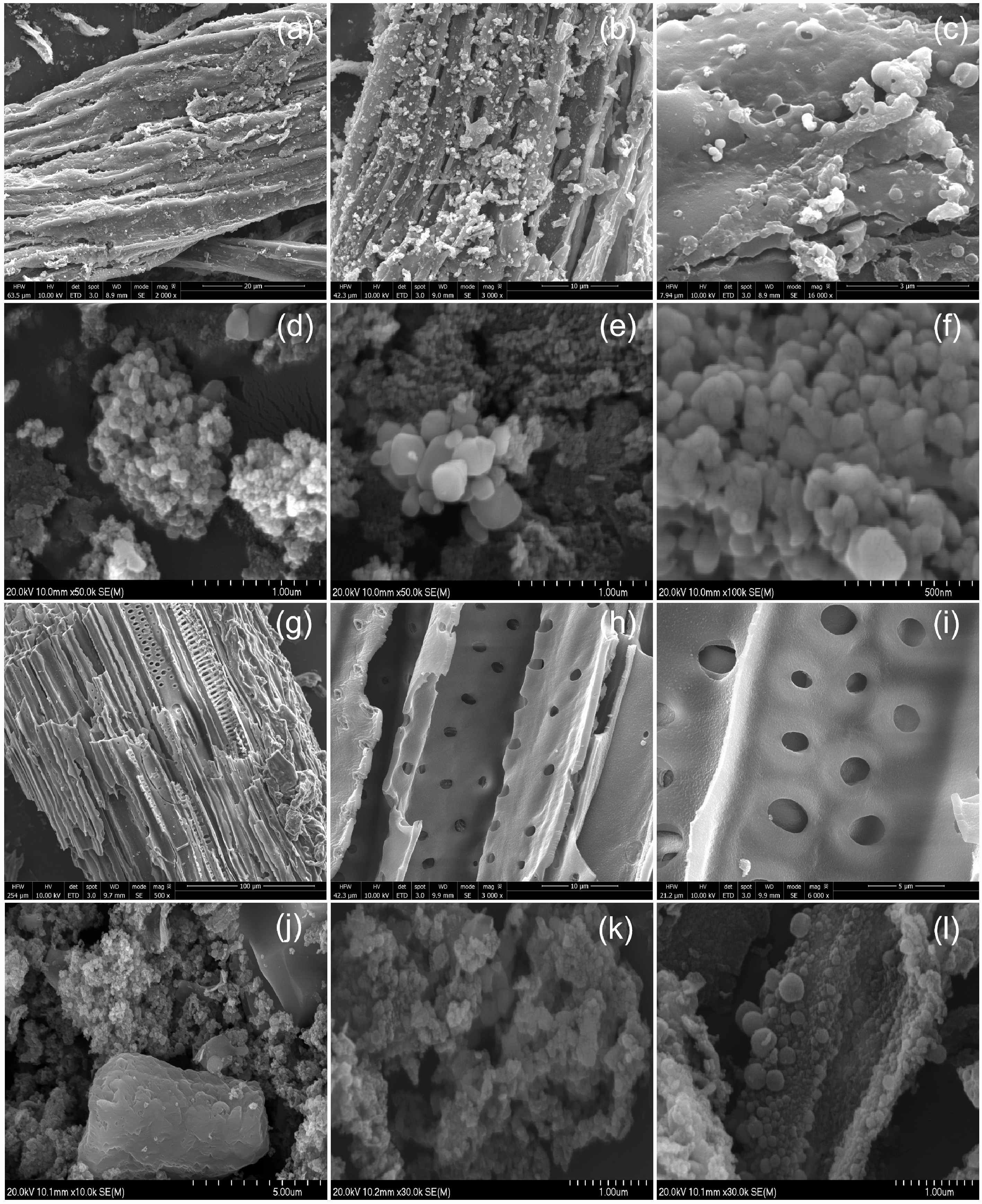

The surface morphology of the hydrochar before and after iron modification was examined through SEM analysis. Hydrochar derived from flax shives (Fig. 5a−f), and eucalyptus (Fig. 5g−l) showed irregularly shaped rough surfaces with unevenly scattered pores and asymmetrical cavities. This can be attributed to the polymerization of thermally degraded products from lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose[46]. When iron was introduced, clusters of interconnected spherical microstructures were observed on the surface of the hydrochar. Porous structures between the microspheres indicated an increase in the surface area of hydrochar, which may facilitate the adsorption process[47]. EDS analysis confirmed the presence of 30.46 and 32.8 wt% Fe in FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, respectively.

Figure 5.

The surface morphology of (a)–(c) FS-HC, (d)–(f) FS-Fe-HC, (g)–(i) ES-HC, and (j)–(l) ES-Fe-HC.

Influence of adsorbent dosage on removal efficiency

-

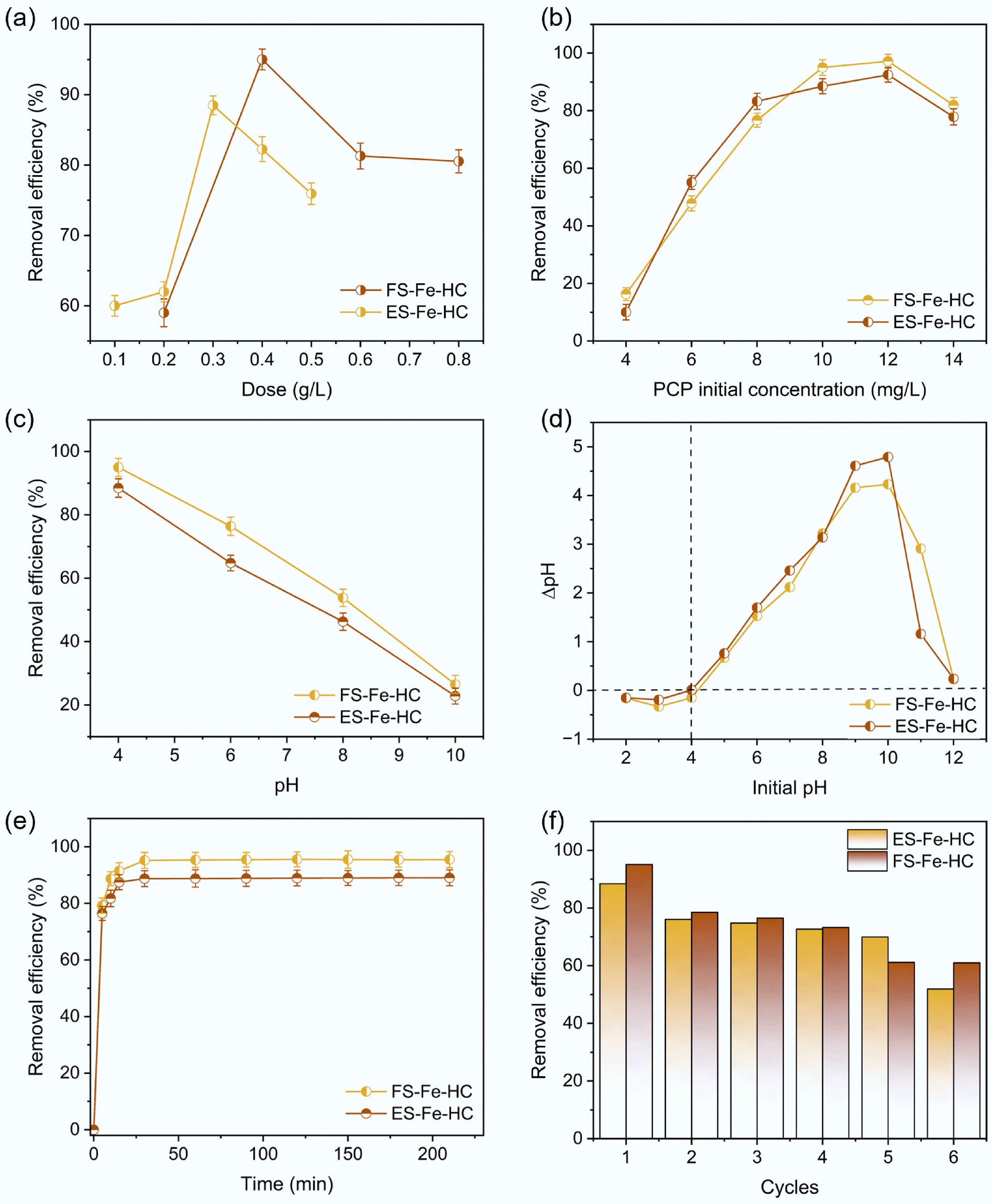

The influence of varying adsorbent dosages was investigated for FS-Fe-HC in the range of 0.2 to 0.8 g/L and for ES-Fe-HC from 0.1 to 0.5 g/L (Fig. 6a). Due to an increasing number of functional groups and active sites for adsorption in the reaction solution, an increasing trend in the removal efficiency was observed for both FS-FE-HC and ES-Fe-HC as the dosage increased[48]. However, no additional increase in efficiency was observed beyond 0.4 g/L (FS-Fe-HC) and 0.3 g/L (ES-Fe-HC). This is probably due to the availability of an excessive number of binding sites at higher dosages that cannot be fully occupied at a constant PCP concentration[49]. As a result, dosages of 0.4 and 0.3 g/L were identified as the optimized amounts, leading to 95% and 88% PCP removal within 60 and 35 min at pH 4 for FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, respectively. The slightly lower removal efficiency observed for ES-Fe-HC may be due to its comparatively lower surface area and fewer surface oxygen-containing functional groups relative to FS-Fe-HC.

Figure 6.

Removal efficiency influenced by (a) adsorbent dose, (b) initial concentration of PCP, (c) pH, (d) point of zero charge, (e) contact time, and (f) reusability.

Influence of initial PCP concentration on removal efficiency

-

For both FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, an increasing trend in removal efficiency was observed as the initial PCP concentration increased. For FS-Fe-HC, PCP removal reached 97% while for ES-Fe-HC it reached 92.4%, when the PCP initial concentration was increased from 4 to 12 mg/L (Fig. 6b). This increase is attributed to the elevated PCP concentration, which enhances the diffusion of PCP from the bulk liquid to the adsorbent surface by increasing the driving force of the concentration gradient[50]. A further increase in the PCP concentration beyond 12 mg/L results in a reduction in removal efficiency for both hydrochars, indicating the saturation of the available binding sites. It was concluded that the initial concentration of PCP influences the removal efficiency during the adsorption process.

Influence of pH on removal efficiency

-

The adsorption of PCP decreases as the pH increases for both FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC. Specifically, the removal efficiency of PCP dropped from 95% to 26.5% for FS-Fe-HC and from 88.4% to 22.8% for ES-Fe-HC when pH was raised from 4 to 10 (Fig. 6c). The two most common properties inherent to ionizable organic contaminants are solubility and distribution ratios, both of which are significantly affected by the solution's pH. As the pH value increases, the distribution ratio of PCP in water decreases, while its solubility increases, thereby affecting the adsorption[51]. The primary form in which PCP exists in nature is PCP0 at pH < pKa and PCP¯ at pH > pKa[52]. Various studies indicate that since PCP is a weak hydrophobic organic acid (pKa:4.7), which remains mostly neutral in the acidic range of pH, it shows higher rates of adsorption compared to when the pH is basic, where it exists as an anion[24]. This is attributed to the surface charge of the hydrochar becoming more negative as the pH increases, which leads to the repulsion of more pentachlorophenolate anions[53]. The higher solubility and reduced hydrophobicity of the ionized (anionic) form of PCP are responsible for the significant decrease in PCP adsorption on hydrochar as the pH rises[51].

Point of zero charge of FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC

-

The point of zero charge was investigated and found to be 4.2 for FS-Fe-HC and 3.9 for ES-Fe-HC, as shown in Fig. 6d. At a pHpzc around 4, both hydrochars have neutral surface charges. And below this pH, they acquire positive charges, which enhance the adsorption of the negatively charged PCP through electrostatic attraction. Therefore, FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC can effectively capture anionic PCP at a pH level below 4. This finding supports the observation obtained during pH optimization, where the highest removal efficiency was achieved at pH 4.

Influence of contact time

-

The study examined how contact time affects the removal of PCP using FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC under optimized conditions. The adsorption process occurred in two phases. A rapid phase lasting 10–15 min, during which more than 80% of PCP was removed, followed by a flat phase that extended up to 210 min (Fig. 6e). The quick uptake of PCP during the rapid phase was observed due to the availability of abundant vacant binding sites[54]. However, as the contact time increased, the remaining binding sites became harder to occupy due to repulsive forces between the PCP in the liquid and those on the adsorbent surface. Eventually, the hydrochar surface reached saturation, leading to the establishment of equilibrium. When the contact time was extended to 1,680 min, 11.6% and 21% desorption was observed in the case of FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC. This desorption likely occurred due to the release of loosely bound PCP and the saturation of the adsorbent's capacity to further retain adsorbed PCP[55]. Table 3 summarizes the comparative potential of different biomass waste-based adsorbents for PCP removal.

Table 3. Summary of different biomass waste-based adsorbents for PCP removal

Adsorbent Adsorbent dose (g/L) Time (h) PCP (mg/L) pH Removal efficiency (%) Ref. Flax shives hydrochar 0.1 0.33 10 3 81 [25] Fe3O4−SiO2 decorated carbon nanotubes 0.5 2 100 2.5 98 [54] Carbon nanotubes 0.35 1 1 − 88 [59] Fungal biomass 1 6 1 3 100 [53] Sunflower seed waste 40 1 5 2.5 84 [60] FS-Fe-HC 0.4 1 10 4 95 This study ES-Fe-HC 0.3 0.58 10 4 88 This study Kinetics and isotherm analysis

-

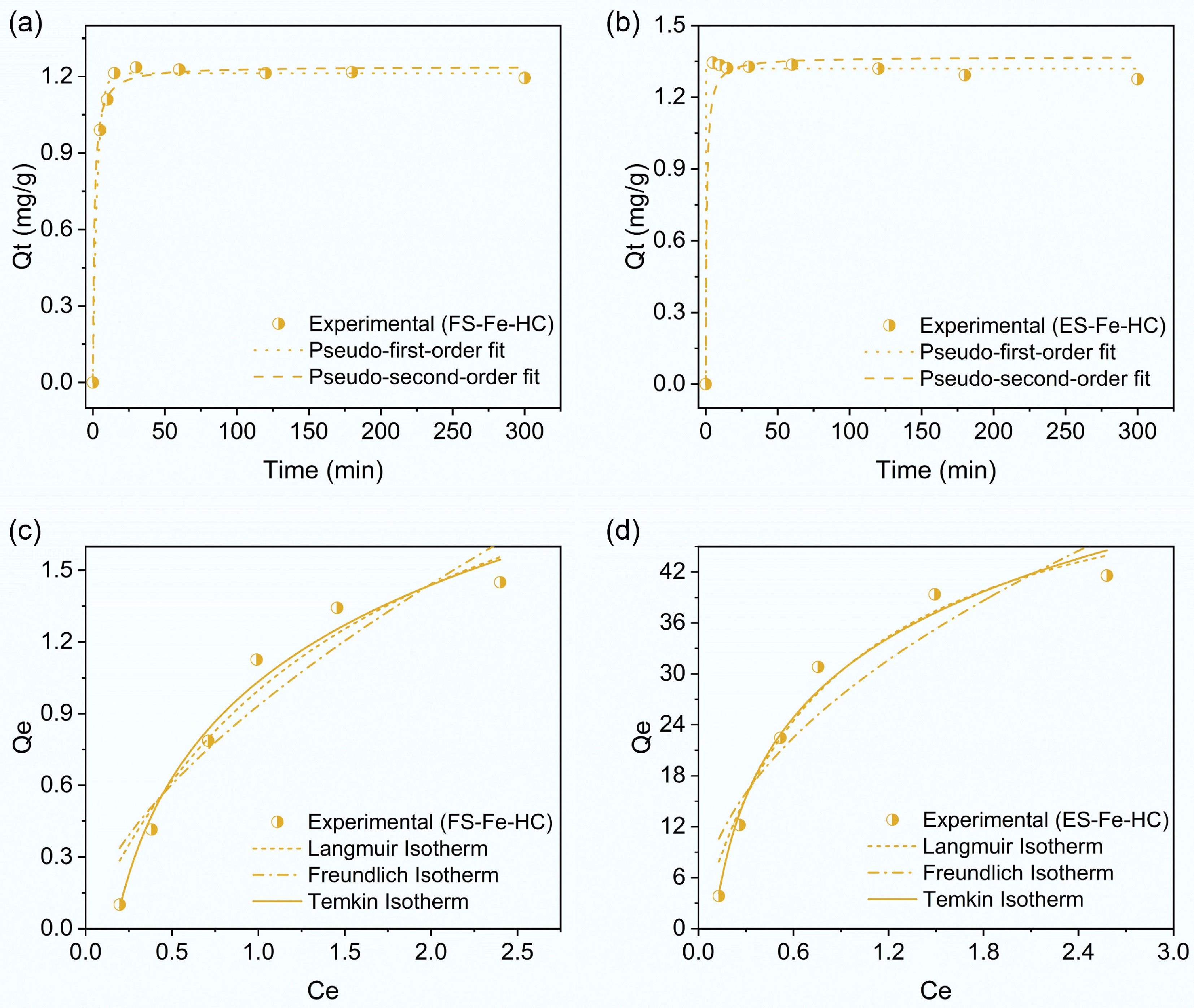

Non-linear kinetic models were applied to evaluate the effect of reaction time on PCP adsorption by FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC. Unlike linearized forms, non-linear kinetic equations do not require prior assumptions about the experimental equilibrium adsorption capacity, which makes them more accurate and reliable for data fitting. Therefore, the non-linear approach is more appropriate and preferred for determining adsorption parameters[56]. Table 4 presents the parameters obtained by fitting non-linear kinetic models to PCP adsorption data. For adsorption using both FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, the pseudo-first order kinetic model showed better fitting when compared to the pseudo-second order model (Fig. 7a, b). A higher coefficient of correlation and the lowest χ2 were observed, indicating good agreement in Qe(cal) and Qe(exp). Thus, it can be concluded that PCP adsorption was influenced by the available surface area of the hydrochar, allowing PCP molecules to form a surface layer and penetrate the adsorbent's pores[57]. To understand PCP adsorption on FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC, the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models were explored, with the non-linear fitting outcomes shown in Table 4 and Fig. 7c, d for comparing the better fitness of each model. Favorable adsorption was indicated by the RL values, which fall in the range of 0 to 1. Among the models, the Temkin model provided the best fit for both hydrochars, indicating heterogeneous surfaces where the heat of adsorption decreases linearly with increasing surface coverage. The intensity-related coefficient (n) reflects the affinity of the adsorption process, where a value of n > 1 suggests the likelihood of physisorption[58]. The pH dependency of PCP adsorption also indicated the potential involvement of electrostatic attraction forces.

Table 4. Kinetics and isotherm models for PCP adsorption using FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC

FS-Fe-HC ES-Fe-HC Kinetics Pseudo-first order model Qe(exp) (mg/g) 1.227 1.336 Qe(cal) (mg/g) 1.21 ± 0.01 1.31 ± 0.008 k1 (min−1) 0.32 ± 0.02 0.001 ± 0.01 R2 0.995 0.997 χ2 0.0006 0.0005 Pseudo-second order model Qe(cal) (mg/g) 1.23 ± 0.01 1.36 ± 0.03 k2 (g/mg/min) 0.73 ± 0.14 1.0 ± 0.55 R2 0.992 0.969 χ2 0.001 0.005 Isotherm models Langmuir model Qm (mg/g) 2.58 ± 0.64 57.99 ± 6.71 KL (L/mg) 0.63 ± 0.29 1.22 ± 0.34 RL 0.137 0.075 R2 0.928 0.957 KF 0.93 ± 0.09 28.92 ± 2.5 χ2 0.02 9.56 Freundlich model 1/n 0.628 0.492 n 1.59 ± 0.36 2.03 ± 0.44 R2 0.861 0.860 χ2 0.039 31.08 Temkin model AT (L/g) 5.88 ± 0.76 10.51 ± 1.63 bT 0.583 ± 0.04 13.49 ± 0.98 R2 0.971 0.973 χ2 0.008 5.96

Figure 7.

Kinetic analysis of PCP adsorption using (a) FS-Fe-HC, and (b) ES-Fe-HC, and isotherm model fitting for PCP adsorption using (c) FS-Fe-HC, and (d) ES-Fe-HC.

Recyclability of FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC post PCP adsorption

-

Reusing hydrochar-based adsorbents will lower operational costs and mitigate the environmental impact of the treatment process by increasing the longevity and reducing the need for additional resources[61]. The reusability potential of FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC was investigated through six treatment cycles of PCP contaminated water. It was observed that the adsorption capacity of the hydrochar gradually decreased by the end of the 6th cycle. The removal efficiency dropped from 95% to 60.98% for FS-Fe-HC and from 88% to 51.92% for ES-Fe-HC from cycle 1 to cycle 6, as shown in Fig. 6f. The results indicate that FS-Fe-HC was more efficient than ES-Fe-HC in the adsorption and desorption of PCP.

Leaching study

-

When applying magnetic adsorbents for wastewater treatment, it is crucial to evaluate the potential of iron leaching, as this could lead to secondary water pollution. To investigate the iron leaching behavior of the synthesized hydrochar, ICP spectroscopy was conducted. The results showed that there was no leaching of iron from either FS-Fe-HC or ES-Fe-HC throughout the entire PCP treatment process. Ensuring minimal to no iron leaching is vital for environmental safety as leached iron can introduce contaminants into the ecosystems, posing risks to water quality and aquatic life[62]. Moreover, iron leaching can diminish the magnetic properties of hydrochar, reducing its recyclability and efficiency in water remediation[63].

-

Magnetic hydrochar was successfully synthesized from flax shives and eucalyptus sawdust via HTC for the application in wastewater remediation. Under optimized conditions, FS-Fe-HC and ES-Fe-HC achieved PCP removal efficiencies of up to 95% and 88.5%, respectively. Comprehensive characterization through FTIR, XRD, XPS, SEM-EDS, and BET confirmed the presence of iron oxides, abundant surface functional groups, and well-developed mesoporous structures. The incorporation of iron not only provided magnetic properties, facilitating easy separation, but also significantly enhanced the specific surface area and porosity of the hydrochar, both of which are essential for efficient adsorption. The materials demonstrated strong reusability over multiple cycles with negligible performance loss and no detectable iron leaching, supporting their environmental safety and operational robustness.

This study presents a sustainable approach to valorizing agricultural and forestry biomass into functional adsorbents for removing the persistent contaminant pentachlorophenol. By aligning with circular economy principles and addressing key environmental challenges, these magnetic hydrochars show strong potential for scalable, low-cost wastewater treatment solutions.

-

All authors were involved in developing the study's concept and design. Tunnisha Dasgupta, Himadri Rajput, and Pubudi Perera were responsible for material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tunnisha Dasgupta and Himadri Rajput. Xiaohong Sun and Quan (Sophia) He provided feedback on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship program (ID: 129423), a Mitacs Elevate postdoctoral fellowship in partnership with Stella-Jones Inc. (NS-ISED IT34874), and funding from SSHRC-funded Sustainable Agriculture Research Initiative (1013-2024-0001).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Efficient PCP removal using flax shives and eucalyptus-derived hydrochars.

Well-developed mesoporous structures were observed.

Easy recovery of magnetic hydrochar using an external magnet after treatment.

No iron leaching from hydrochar was observed.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dasgupta T, Rajput H, Perera P, Sun X, He Q. 2025. Sustainable carbon materials for magnetic adsorbent-based pentachlorophenol removal from wastewater. Sustainable Carbon Materials 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0003

Sustainable carbon materials for magnetic adsorbent-based pentachlorophenol removal from wastewater

- Received: 13 June 2025

- Revised: 26 July 2025

- Accepted: 20 September 2025

- Published online: 27 October 2025

Abstract: The growing water scarcity caused by human activities and urbanization has made it essential to develop sustainable and cost-effective strategies for wastewater treatment and reuse. This study involved converting biomass waste from agricultural and forestry sources into magnetic carbon-based adsorbents through hydrothermal carbonization (HTC). During the HTC process, iron was incorporated to impart magnetic properties to the resulting hydrochar, enabling post-treatment recovery using an external magnet. Hydrochars derived from flax shives (FS-Fe-HC), and eucalyptus (ES-Fe-HC) were tested for their efficiency in adsorbing pentachlorophenol (PCP) from wastewater. The structural, morphological, and chemical characteristics of the prepared hydrochar were characterized through scanning electron microscopy-electron diffraction spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), and vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) techniques. Batch adsorption experiments revealed maximum PCP removal efficiencies of 95% for FS-Fe-HC, and 88.5% for ES-Fe-HC under optimized conditions. The adsorption performance was found to be influenced by surface functional groups, active adsorption sites, and pH-dependent surface charge. Both hydrochars exhibited excellent reusability over six consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles, with negligible iron leaching, confirming their stability and practical applicability. This study demonstrates the potential of HTC as a sustainable approach for valorizing lignocellulosic waste into effective bio-adsorbents for wastewater remediation, addressing both environmental and industrial challenges. The novelty lies in utilizing dual biomass waste, magnetic recovery capability, and high reusability with minimal iron leaching, thereby contributing to circular economy practices in water treatment.

-

Key words:

- Adsorption /

- Pentachlorophenol /

- Flax shives /

- Eucalyptus /

- Magnetic hydrochar