-

In thermal engineering, fluids serve as the principal medium for energy transport, spanning applications from planetary climate systems to microscale cooling in electronic devices. The efficient design of radiators, heat exchangers, and microscale thermal management systems depends on the capacity of the fluid to store, transfer, and dissipate thermal energy. Advances in computational fluid dynamics have enabled modelling of flow dynamics and temperature fields, and heat transfer efficiency, thus reducing reliance on expensive and time-consuming experimental systems. The development of nanofluids, colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles in base fluids, has provided a new category of high-performance heat transfer media characterized by high thermal conductivity and low energy consumption by Zhang et al. and Doost et al.[1,2]. The evolution of nanofluids represents a remarkable leap in thermal engineering capabilities. Shah et al.[3] show their efforts in solar thermal engineering systems, utilizing the thermophysical properties of nanoparticles, and Timofeeva et al.[4] present a comprehensive description of the engineering approach to advanced heat transfer. Recent work highlights the potential for transformation in renewable energy sectors, extending to electronics cooling with nanofluids offered by Sohel et al. and Santhosh et al.[5,6].

Nanofluids are an important technological advancement in thermal engineering, engineered colloidal suspensions developed by dispersing nanoparticles in the traditional base fluids, like water, ethylene glycol, or oil. This idea, initially proposed by Choi[7], proved that the nanoscale additives could significantly improve the physical characteristics and heat conduction of the fluids regarding their thermophysical properties. The effectiveness of nanofluids depends on nanoparticle attributes, such as material type, morphology, size, and concentration, which collectively influence density, viscosity, specific heat, and thermal conductivity. The synergy of nanoparticles with the underlying fluid has led to the development of hybrid nanofluids, in which two or more species of nanoparticles are combined to enhance thermal functioning in an even larger way. These novel fluids are characterized by better energy carrier properties and have been used in a variety of applications, such as automotive cooling, petroleum processing, thermal management of electronic equipment, and renewable energy systems, particularly in the development of efficient thermoelectric performance of direct absorption solar collectors. Yasmin et al.[8] experimentally verified the use of hybrid nanofluids in thermal and solar energy storage, and Heidarshenas et al.[9] studied the stability and thermophysical behavior of two-dimensional nanomaterials. Thus, understanding and controlling aggregation is crucial in applications like cooling, biomedical systems, and heat exchangers. Subsequent research has compared aggregated and non-aggregated nanoparticles at elevated temperatures in cylindrical geometries by Ramzan et al.[10] and developed models to assess anisotropic conductivity effects by Wu et al.[11]. Mudhukesh et al.[12] studied radiation effects on magnetically aggregated nanoparticles and applied multiscale MD-LBM methods to analyze molten salt nanofluids with aggregated particles by Yang et al.[13].

Convective heat transfer on sinusoidal surfaces is well known to promote convection heat transfer by discontinuously disrupting the thermal boundary layer, which facilitates fluid mixing as well as increasing the thermal efficiency in each direction. It is widely recognized that wave or non-uniform surfaces may greatly enhance heat transfer, as they disrupt the thermal boundary layer and cause fluid mixing. This principle is the foundation of superior cooling techniques in electronics, biomedical devices, and miniature energy equipment. Recent interest has focused on the thermomagnetic effects of such geometries, which has attracted the attention of researchers[14−16] who discovered different wave structures and convection patterns. For example, Iqbal et al.[17,18] investigated the interaction of magnetic and thermal fields, and Akter et al. and Munir et al.[19,20] considered how the inclusion of a magnetic field can influence thermal performance. Practically speaking, the wavy heat exchangers have been particularly useful in augmenting circulation and heat distribution in fluids, thus decreasing thermal stresses and enhancing the overall efficiency of energy use[21−23].

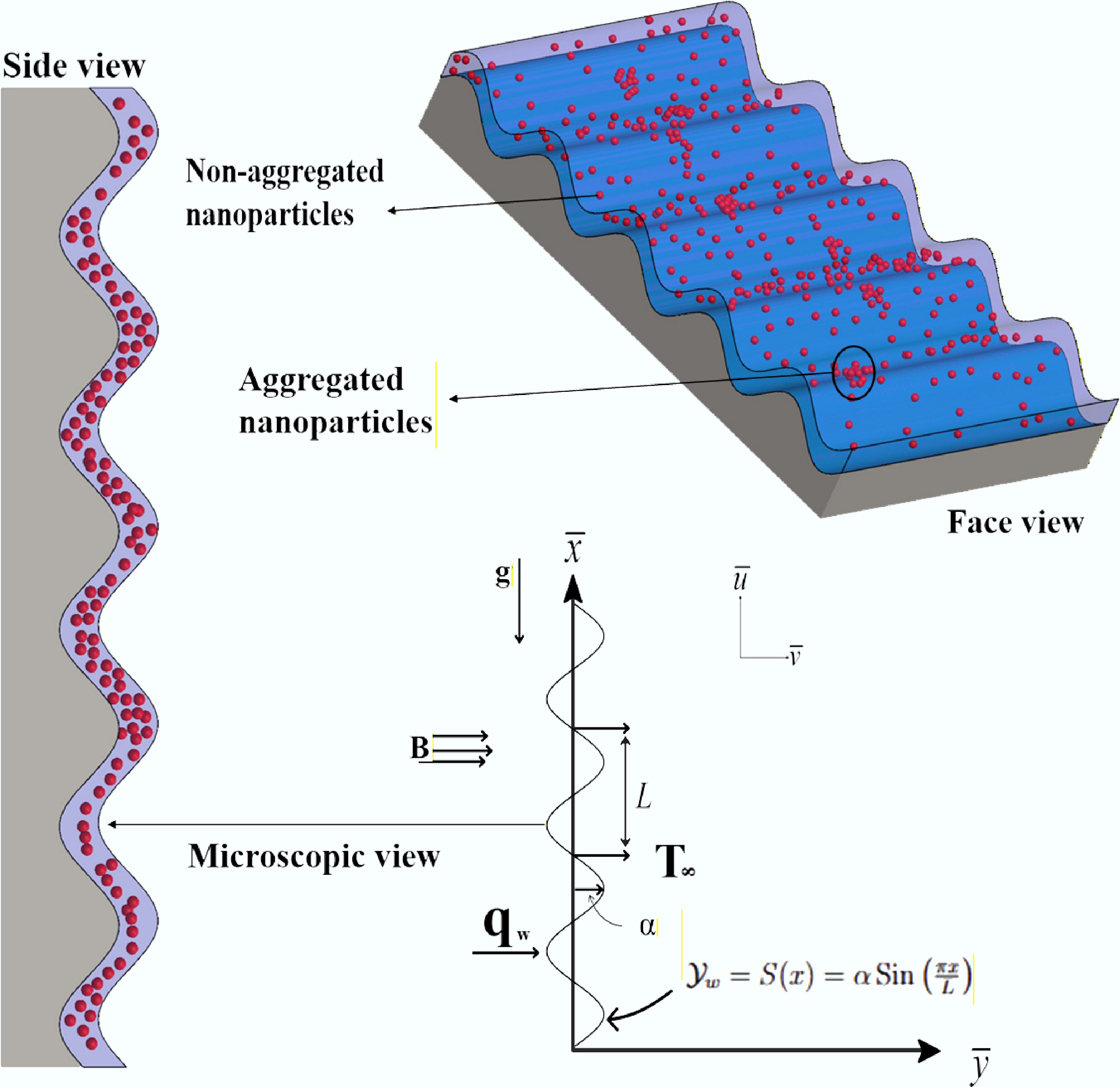

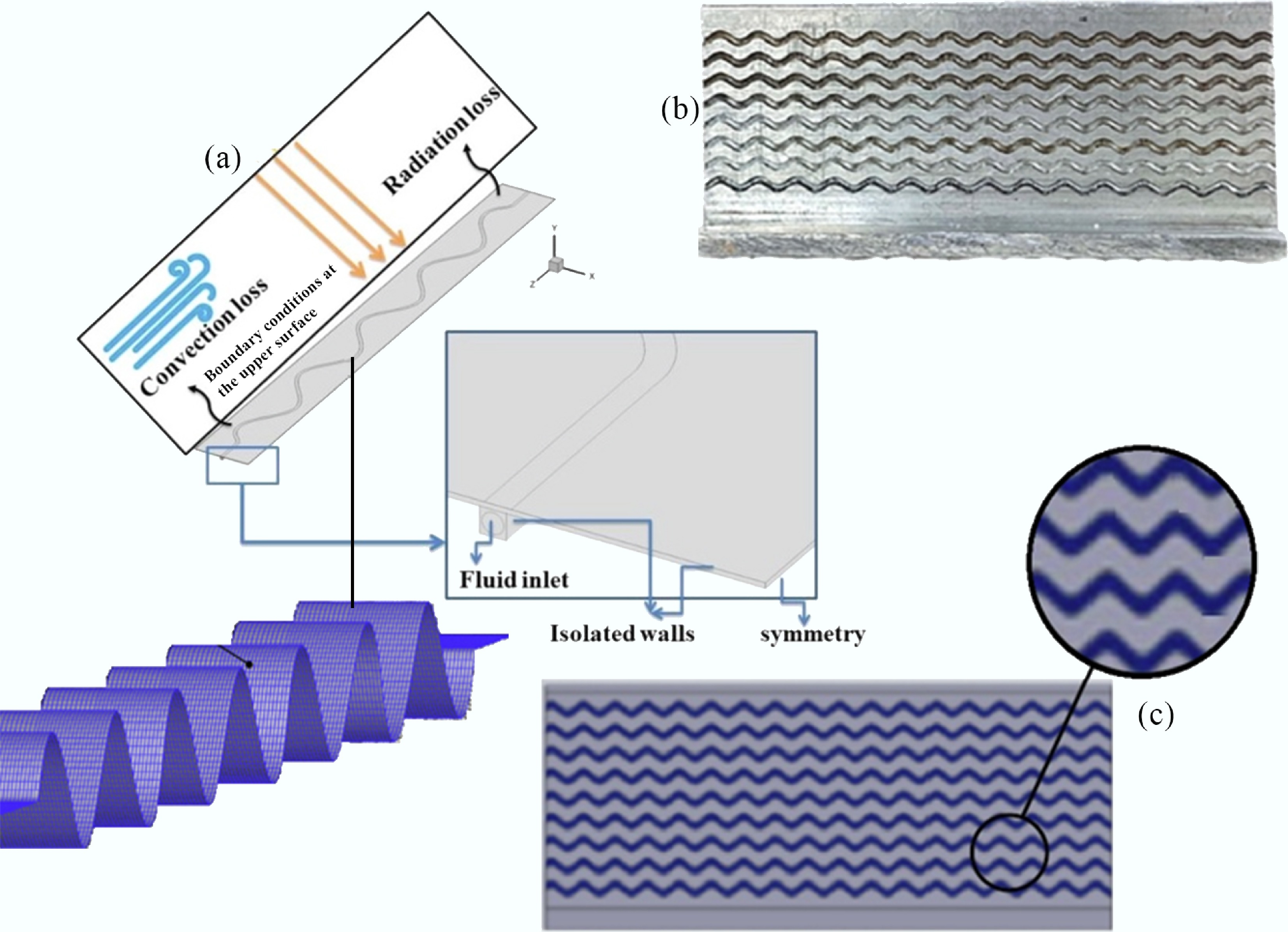

The physical configuration of the wavy-surfaced porous medium solar collector and computational mesh, and boundary conditions are depicted in Fig. 1[24−28]. In the physical model illustrated in Fig. 1a, the saturation of a wavy absorber surface with nanofluid is represented, and heat transfer is achieved by absorbing solar energy at the top and surface of the heated material, radiative cooling, and convectional exchange with the surrounding air. Figure 1b presents the wavy absorber plate used in the experimental or modeled setup, highlighting the structured surface geometry that enhances heat transfer performance. Figure 1c demonstrates the computational mesh and boundary conditions, such as an adiabatic bottom wall, symmetrical side lateral walls, a nanofluid inlet with specified velocity and temperature, and an upper surface that has convective and radiative heat losses. These sub-figures define the problem domain, mesh strategy, and thermal boundary constraints employed in the numerical analysis.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the physical model and computational domain with a sinusoidal surface. (a) Heat transfer mechanisms and loss components. (b) Boundary conditions and symmetry setup. (c) Overall system configuration.

Growing global energy demands have made the optimization of heat exchangers a critical priority in thermal system design. ANNs have become potent predictors of the behavior of heat transfer and system optimization to reduce system efficiency, providing high accuracy with minimal computational cost through their ability to learn from complex input data sets. The trend is shown by their recent research, where ANN modeling was used for hybrid nanofluids and for the optimization of polymer microchannels by Ain et al.[29] and Kamsuwan et al.[30], respectively. Other studies have analyzed radiative Jeffrey nanofluid flow by Zeeshan et al.[31], and Islam et al.[32] applied ANN to the response surface methodology. Subsequent works include those by Bilal et al.[33], which provided numerical and experimental confirmation of ANN-based models, and Ali et al.[34], which provided subsequent confirmation through numerical and experimental validation. Additional advancements highlight the versatility of machine learning in thermal systems. A study on material selection and optimization of hybrid solar-thermal plume systems to enhance passive cooling and energy efficiency was presented for materials in 2025 by Yahya et al.[35]. A methodology for the radiative heat transport of nanofluids over a vertical cylinder is presented by Mahanthesh & Thriveni[36]. The simulation-driven optimization of direct solar dryers using a combined CFD and ANN-GA approach was demonstrated by Loksupapaiboon et al.[37].

Although significant progress has been made in understanding nanofluid heat transfer phenomena, the influence of nanoparticle properties, especially Lorentz forces and clustering performance under complex wavy surfaces, has received limited attention, as most investigations examine these factors individually. To fill this gap, the current study develops a robust Keller-box numerical framework to analyze MHD flow and oscillatory heat transfer of a carbon nanofluid over a wavy surface. By systematically evaluating both aggregated and non-aggregated nanoparticles under flexible magnetic fields and sinusoidal boundary conditions, this effort delivers practical insights relevant to industrial thermal management. Motivated by the need to augment thermal performance in geometrically complex, magnetically assisted cooling classifications, the current work has direct significance for high-flux cooling of compact heat exchangers in aerospace thermal management, power electronics (e.g., CPUs, IGBTs), and advanced solar collectors. The prime objectives are: (1) to assess the coupled effects of surface waves on nanoparticle aggregation, MHD forces, and oscillatory heat transfer; (2) to analyze the trade-off between hydrodynamic penalty and thermal enhancement; and (3) to develop a fast, accurate machine learning model for predictive analysis. This work fills the existing gap by:

• Developing a viscosity model that incorporates a modified thermal conductivity model for magnetic fields and sinusoidal surface parameters;

• Leveraging the high-fidelity KBM data to train an accurate ANN surrogate model for fast performance prediction and optimization with an MSE of ~10−7).

-

This study investigates steady, laminar free convection of an incompressible nanofluid along a vertically oriented wavy surface with constant heat flux, under the influence of a transverse magnetic field. Assuming a low Reynolds number, the induced magnetic field is negligible. The formulation incorporates Lorentz forces and sinusoidal boundary conditions to represent natural convection influenced by magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effects and surface undulations. The wavy surface is defined by

$ {Y}_{w}=\overline{\alpha }\sin \left(\pi \overline{x}/L\right) $ $ \overline{\alpha } $ $ \nabla . V=0, $ (1) $ \left(V.\nabla \right)V=-\dfrac{1}{{\rho }_{nf}}\nabla p+{\nabla }^{2}V+\dfrac{{\left(\rho \beta \right)}_{nf}}{{\rho }_{nf}}g\left(T-{T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}\right)-\dfrac{{\sigma }_{nf}{B}_{0}}{{\rho }_{nf}}V, $ (2) $ V.\nabla T={\alpha }_{nf}{\nabla }^{2}T, $ (3) $ \left.\begin{array}{l} y=S\left(\overline{x}\right)\colon \;\overline{u}=\overline{v}=0,\;T={T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}+\left({T}_{w}-{T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}\right)\left[1+{\varepsilon }_{T}\sin \left(\dfrac{\pi \overline{x}}{L}\right)\right],\\ y\rightarrow \mathrm{\infty }\colon \;\overline{u}=0,\;p={p}_{\mathrm{\infty }},\;T={T}_{\mathrm{\infty }} \end{array}\right\} $ (4) where, p denotes the fluid pressure, with

$ {p}_{\mathrm{\infty }} $ $ \sigma $ $ \rho , $ $ \begin{split}&\psi \left(\xi ,\eta \right)={\xi }^{3/4}f\left(\xi ,\eta \right),\quad \xi =\dfrac{x}{l},\quad \eta ={\xi }^{-1/4}y,\\& v=\dfrac{{\rho }_{nf}}{{\mu }_{f}}G{r}^{-1/4}\left(\overline{v}-{S}_{\xi }\overline{u}\right),\quad S=\dfrac{S\left(\overline{x}\right)}{l}=\overline{\alpha }\sin \left(\pi \xi \right),\\& \Omega =\sqrt{1+S_{\xi }^{2}}, \quad \theta \left(\xi ,\eta \right)=\dfrac{T-{T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}}{{T}_{w}-{T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}},\quad u=\dfrac{{\rho }_{nf}}{{\mu }_{f}}G{r}^{-1/2}\overline{u},\\& \overline{v}=-\dfrac{\partial \psi }{\partial \overline{x}},\quad y=\dfrac{y-S\left(\overline{x}\right)}{l}G{r}^{1/4},\quad M=\dfrac{Q{l}^{2}}{{\mu }_{f}G{r}^{1/2}{\left(\rho {c}_{p}\right)}_{f}},\\&\overline{u}=-\dfrac{\partial \psi }{\partial \overline{y}},\quad P=\dfrac{{l}^{2}}{{\nu }^{2}{\rho }_{f}}G{r}^{-1/4}p,\quad Gr=\dfrac{g{\beta }_{f}\left({T}_{w}-{T}_{\mathrm{\infty }}\right){l}^{3}}{\nu _{f}^{2}}, \end{split} $ (5) The wall temperature is prescribed as Tw(x), where Tw is the mean wall temperature, and T∞ is the ambient fluid temperature, satisfying Tw > T∞ and modulated by the sinusoidal parameter

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ \alpha =\overline{\alpha }/L $ $ {\nabla }^{2} $ $ V=\left(\overline{u},\overline{v}\right) $ $\begin{split}& \dfrac{{\Omega }^{2}}{{D}_{1}}{f}^{\prime\prime\prime}+\dfrac{3}{4}f{f}^{\prime\prime}-\xi \left(\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{{\Omega }_{\xi }}{\Omega }\xi \right){\left({f}^{\prime}\right)}^{2}-{\xi }^{1/2}\left(\dfrac{M{D}_{4}}{{D}_{2}{\Omega }^{2}}\right){f}^{\prime}-\dfrac{{D}_{4}}{{D}_{2}{\Omega }^{2}}\theta =\\&\xi \left[{f}^{\prime}\dfrac{\partial {f}^{\prime}}{\partial \xi }-{f}^{\prime\prime}\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial \xi }\right],\end{split} $ (6) $ \dfrac{{\Omega }^{2}}{{D}_{3}\Pr }{\theta }^{\prime\prime}+\dfrac{3}{4}f\theta =\xi \left[{f}^{\prime}\dfrac{\partial \theta }{\partial \xi }-{\theta }^{\prime}\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial \xi }\right], $ (7) $ \begin{aligned}\left.\begin{array}{l} \eta \rightarrow 0\colon \;\;f\left(\xi ,\eta \right)=0,\;\;{f}^{\prime}\left(\xi ,\eta \right)=0,\;\;\theta \left(\xi \right)=\left[1+{\varepsilon }_{T}\sin \left(\pi \xi \right)\right],\\ \eta \rightarrow \mathrm{\infty }\colon \;\;{f}^{\prime}\left(\xi ,\eta \right)=0,\;\;\theta \left(\xi ,\eta \right)=0 \end{array}\right\}\\ & \end{aligned} $ (8) where, the Prandtl and magnetic numbers are denoted by Pr and M, respectively. The subscript

$ \xi $ $ \xi $ $ {}^{\prime} $ $ \eta $ $ \Omega $ The constants D1, D2, D3, D4, and D are nanofluid-specific parameters listed in Table 1. By employing Eq. (5), the local skin friction coefficient (Cf) and the local Nusselt number (Nu) in nondimensional form are expressed as follows. Table 2 Assumed values of physical quantities for scenario construction[37].

Table 1. Thermophysical properties of aggregated and non-aggregated nanoparticles by Mahanthesh et al.[36]

Property Constant Non-aggregation Aggregated Viscosity $ \mu $ D1 $ {\mu }_{n f}={\mu }_{f}{\left(1-\varphi \right)}^{-2.5} $ $ {\mu }_{n f}={\mu }_{f}{\left(\dfrac{{\phi }_{m}-{\phi }_{a}}{{\phi }_{m}}\right)}^{{{\phi }_{m}}} $ Density $ \rho $ D2 $ {\rho }_{n f}={\rho }_{f}\left[\left(1-\phi \right)+\phi \left(\dfrac{{\rho }_{s}}{{\rho }_{f}}\right)\right] $ $ {\rho }_{n f}={\rho }_{f}\left[\left(1-{\phi }_{a}\right)+{\phi }_{a}\left(\dfrac{{\rho }_{s}}{{\rho }_{f}}\right)\right] $ Specific heat capacity Cp D3 $ {\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{nf}={\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{f}\left[\left(1-\phi \right)+\dfrac{{\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{s}}{{\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{f}}\phi \right] $ $ {\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{nf}={\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{f}\left[\left(1-{\phi }_{a}\right)+\dfrac{{\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{s}}{{\left(\rho {C}_{P}\right)}_{f}}{\phi }_{a}\right] $ Thermal conductivity k D4 $ {k}_{n f}=\left[\dfrac{\left({k}_{s}+2{k}_{f}\right)-2\phi \left({k}_{f}-{k}_{s}\right)}{\left({k}_{s}+2{k}_{f}\right)+\phi \left({k}_{f}-{k}_{s}\right)}\right]{k}_{f} $ $ {k}_{n f}=\left[\dfrac{\left({k}_{s}+2{k}_{f}\right)-2{\phi }_{a}\left({k}_{f}-{k}_{s}\right)}{\left({k}_{s}+2{k}_{f}\right)+{\phi }_{a}\left({k}_{f}-{k}_{s}\right)}\right]{k}_{f} $ Electrical conductivity $ \sigma $ D5 $ {\sigma }_{n f}={\sigma }_{f}+{\sigma }_{f}\left[\dfrac{3\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}-1\right)\phi }{\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}+2\right)-\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}-1\right)\phi }\right] $ $ {\sigma }_{n f}={\sigma }_{f}+{\sigma }_{f}\left[\dfrac{3\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}-1\right){\phi }_{a}}{\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}+2\right)-\left(\dfrac{{\sigma }_{s}}{{\sigma }_{f}}-1\right){\phi }_{a}}\right] $ Table 2. Parameter sets for scenario construction

A. Non-aggregated B. Aggregated Scenario Case Selected parameters M $ {\boldsymbol\varepsilon }_{\boldsymbol T} $ Description I (A, B) 1 1 0.5 Weak magnetism over a wavy boundary 2 2 0.5 Moderate field, typical in electronics cooling 3 3 0.5 High-intensity field (advanced heat exchangers) II (A, B) 1 4 1 Flat surface (baseline waviness) 2 4 2 Moderate waviness boosts fluid mixing 3 4 3 High undulation resembling turbulence $ {C}_{f}={C}_{f\overline{x}}\,{\left(Gr/\overline{x}\right)}^{1/4}=\dfrac{\Omega }{{\left(1-\phi \right)}^{2.5}}{f}^{\prime\prime}\left(\xi ,0\right), $ (9) $ Nu=N{u}_{\overline{x}}\,{\left(Gr{\overline{x}}^{3}\right)}^{-1/4}=\Omega \dfrac{{k}_{nf}}{{k}_{f}}{\theta }^{\prime}\left(\xi ,0\right), $ (10) The current study uses a model of an artificial neural network (ANN) to estimate velocity and temperature distributions in different surface profiles with changing magnetic field strength, which is explained in Table 2 inspired by Kamsuwan et al.[30]. Two configurations are analyzed:

• Configuration A: Non-aggregated nanoparticles with variations in magnetic and sinusoidal parameters.

• Configuration B: Aggregated nanoparticles considering the combined influence of magnetic and sinusoidal parameters.

The study further explores two comparative scenarios:

• Scenario (I) (A, B): Cases 1–3 investigate the influence of magnetic field intensity.

• Scenario (II) (A, B): Cases 1–3 analyze the effects of sinusoidal surface parameters.

The dispersions of monodisperse diamond nanoparticles (20–50 nm) in water are due to their high thermal conductivity (1,000 W/m·K), chemical stability, and low aggregation propensity under (MHD) conditions. Diamond is also ideal because it has better heat transfer properties than metallic nanoparticles and is thus suited to high-precision uses, including aerospace cooling and power electronics.

The classical Maxwell and Brinkman models are used to compute the effective thermophysical properties, such as thermal conductivity and viscosity, with simplified results summarized in Tables 1 and 3 presents the effective thermophysical models for aggregated and non-aggregated nanoparticles by Mahanthesh et al.[36,40]. Aggregation impacts key properties such as viscosity, density, and thermal conductivity. Fractal-based models account for nanoparticle clustering, capturing irregular geometries and nanolayer effects that enhance heat transfer. Other factors like nanolayer thickness, cluster diameter, and interfacial resistance influence the overall conductivity, especially under nanoscale confinement by Prasher et al. and Evans et al.[41,42]. Additionally, viscosity decreases with rising temperature, as reported by Salahuddin et al.[43].

Table 3. Thermophysical properties of the considered nanoparticles by Sundar et al.[39]

Property Base fluid Nanoparticle Pure water Diamond $ \mu $ (Pas) 0.000803 − Density $ \rho $ (kg/m3) 997.1 3,510 Specific heat capacity Cp (J/kg·K) 6.13 × 10−1 497.26 Thermal conductivity k (W/m·K) 4,179 1,000 Average size − 30 nm Range − 20–50 nm Purity − > 95% -

An implicit finite difference scheme based on the KBM by Keller and Cebeci & Bradshaw[44,45] is used to solve the governing partial differential Eqs (6) and (7) with boundary conditions Eq. (8). It provides second-order accuracy and numerical stability in highly nonlinear systems. The computational domain is discretized via uniform steps in both the

$ \eta $ $ \xi $ • Transformation of higher-order PDEs to first-order systems through variable substitution:

• Discretization using central differences with step sizes

$ \Delta \eta =\Delta \xi =0.005 $ • Linearization of resulting algebraic equations via Newton's method

• Solution of the linear system through block tri-diagonal elimination

$ {f}^{\prime}=r,\;\; q={f}^{\prime\prime},\;\; t={\theta }^{\prime}, $ (11) By applying Eq. (11), the transformed forms of the governing Eqs (6) and (7) are derived as follows:

$ \dfrac{{\Omega }^{2}}{{D}_{1}}{q}^{\prime}+\dfrac{3}{4}fq-\xi \left(\dfrac{1}{2}+\dfrac{{\Omega }_{\xi }}{\Omega }\xi \right){\left(r\right)}^{2}-{\xi }^{1/2}\left(\dfrac{M{D}_{4}}{{D}_{2}{\Omega }^{2}}\right)r-\dfrac{{D}_{4}}{{D}_{2}{\Omega }^{2}}\theta =\xi \left[r\dfrac{\partial {f}^{\prime}}{\partial \xi }-q\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial \xi }\right], $ (12) $ \dfrac{{\Omega }^{2}}{{D}_{3}\Pr }{t}^{\prime}+\dfrac{3}{4}f\theta =\xi \left[r\dfrac{\partial \theta }{\partial \xi }-t\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial \xi }\right], $ (13) Boundary conditions and grid discretization

-

By applying Eq. (11), the transformed boundary conditions corresponding to Eq. (8) are obtained as follows.

$ \left.\begin{array}{l} f\left(\xi ,0\right)=0,\;\; r\left(\xi ,0\right)=0,\;\;\theta \left(\xi ,0\right)=\left[1+{\varepsilon }_{T}\sin \left(\pi \xi \right)\right],\\ {f}^{\prime}\left(\xi ,\mathrm{\infty }\right)=0,\;\;\theta \left(\xi ,\mathrm{\infty }\right)=0 \end{array}\right\} $ (14) The computational grid is constructed with

$ \begin{array}{ccc} {\xi }^{0}=0,\quad {\xi }^{n}={\xi }^{n-1}+{k}_{n}\\ \eta {}_{0}=0,\quad {\eta }_{j}={\eta }_{j-1}+{h}_{j} \end{array} $ (15) for

$ \eta ,j $ $ {N}_{\eta } $ $ {N}_{\xi } $ $ \begin{aligned}( )_{j}^{n-0.5}&=0.5\left[( )_{j}^{n}+( )_{j}^{n-1}\right]\\ ( )_{j-0.5}^{n}&=0.5\left[( )_{j}^{n}+( )_{j-1}^{n}\right] \end{aligned} $ (16) $ \begin{aligned}f_{j}^{i+1}&=f_{j}^{i}+\delta f_{j}^{i}\\ r_{j}^{i+1}&=r_{j}^{i}+\delta r_{j}^{i}\\ \theta _{j}^{i+1}&=\theta _{j}^{i}+\delta \theta _{j}^{i} \end{aligned} $ (17) The linearized system is solved using a block tri-diagonal algorithm with a convergence criterionof

$ {\left|\left|\delta \right|\right|}_{\mathrm{\infty }} < {10}^{-6} $ Validation and verification

-

Numerical accuracy is ensured through

• Conservation checks for mass, momentum, and energy

• A grid independence study, as detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Grid independence test for $ \phi $ = 0.0, Pr = 0.62, $ \alpha $ = 0.1, and M = 0.2

Number of grid points Output η- direction

(With fixed η = 20)ξ- direction

(With fixed ξ = 1)Cf Nu 100 10 −0.85351 0.31688 200 20 −0.85381 0.31699 400 50 −0.85392 0.31680 800 100 −0.85392 0.31680 1,600 200 −0.85382 0.31680 To guarantee that the numerical predictions are independent of spatial resolution, a grid convergence study was performed as Iqbal et al.[17]. The computational domain was discretized using progressively refined meshes ranging from 100 × 10 to 1,600 × 200 elements. Special mesh refinement was applied near the wavy wall (

$ \eta $ $ \xi $ The grid sensitivity was assessed through the skin friction coefficient Cf and local Nusselt number (Nu). Results obtained using an 800 × 100 to 1,600 × 200 mesh differed by less than 0.0001% from those computed with a 1,600 × 200 mesh, confirming grid independence. Hence, all subsequent simulations were conducted on the 1,600 × 200 grid. Table 4 presents the normalized Cf and Nu distributions for various mesh densities, reaffirming the adequacy of the selected grid resolution.

Machine learning (ANN) methodology

-

Artificial neural networks are feedforward networks trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation algorithm. This study consisted of an input layer (configuration M,

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ Table 5. Outcomes of all scenarios with ANNs and LMT

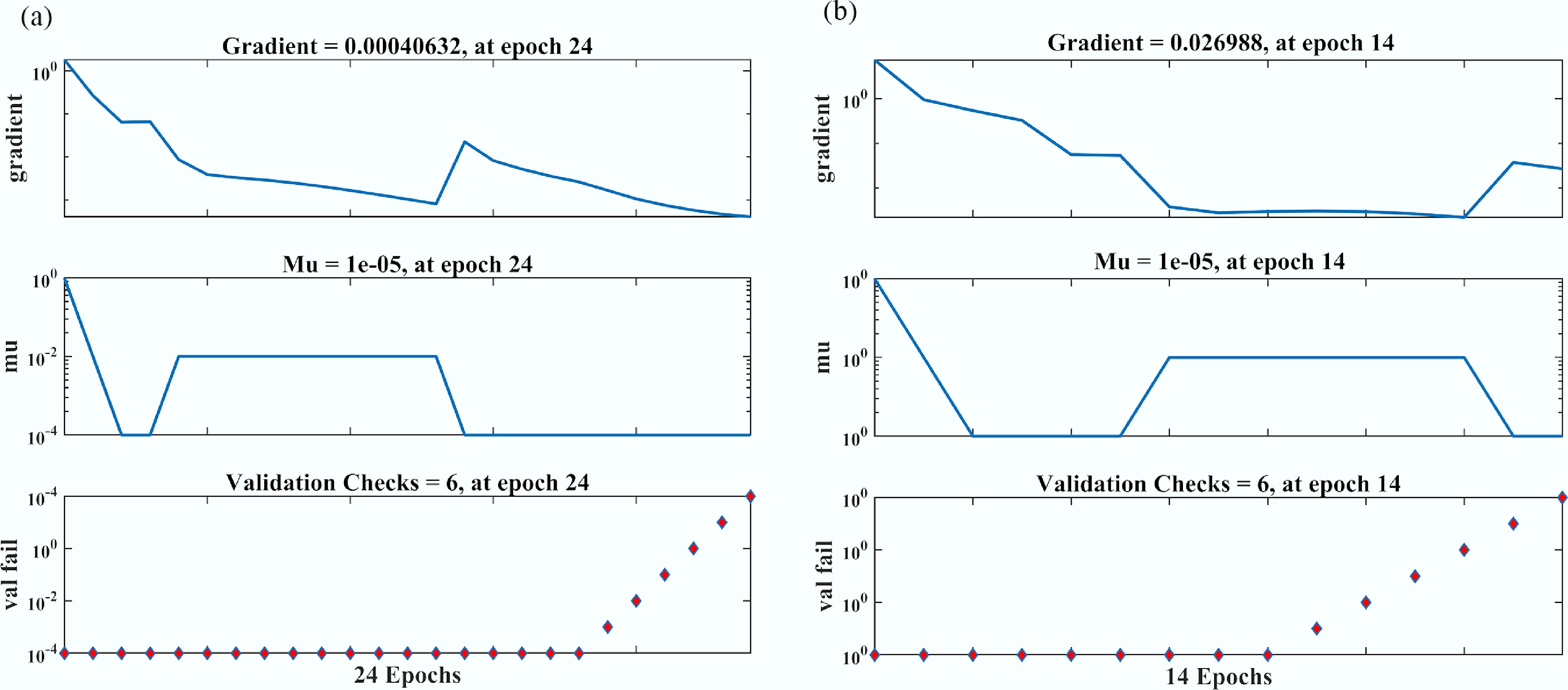

Scenario Case MSE data Performance Gradient Mu Final epoch Time (s) Training Validation Testing Non-aggregated I A 1 1.48882e–5 3.23527e–5 1.38677e–5 1.21e–5 1.00e–7 1e10 25 < 1 2 1.48550e–5 3.32879e–5 1.47673e–5 1.20e–5 1.92e–8 1e10 67 < 2 3 1.72843e–5 3.13655e–5 1.32171e–5 1.03e–5 1.98e–7 1e10 99 < 3 II A 1 4.35370e–6 4.65936e–5 4.34532e–5 4.09e–6 9.99e–08 1e–6 93 6 2 4.89685e–6 4.54796e–5 4.58981e–5 3.89e–6 9.92e–08 1e–6 104 4 3 4.52364e–6 4.85467e–5 5.41256e–5 4.89e–6 9.98e–08 1e–6 186 3 Aggregated I B 1 2.18093e−7 8.82690e−7 1.22922e−6 1.54e−7 2.50e−5 1e−10 117 3 2 2.18767e−7 8.47592e−7 1.59921e−6 1.73e−7 2.94e−6 1e−10 184 2 3 2.79081e−7 8.85570e−7 2.58671e−6 1.95e−7 3.35e−5 1e−10 220 3 II B 1 5.05758e−4 3.33414e−3 1.15199e−3 4.43e−4 7.33e−7 1e−5 14 2 2 5.05423e−4 3.53341e−3 1.15171e−3 4.55e−4 7.90e−8 1e−5 25 4 3 5.06846e−4 3.69321e−3 1.16161e−3 4.68e−4 7.94e−8 1e−5 46 3 -

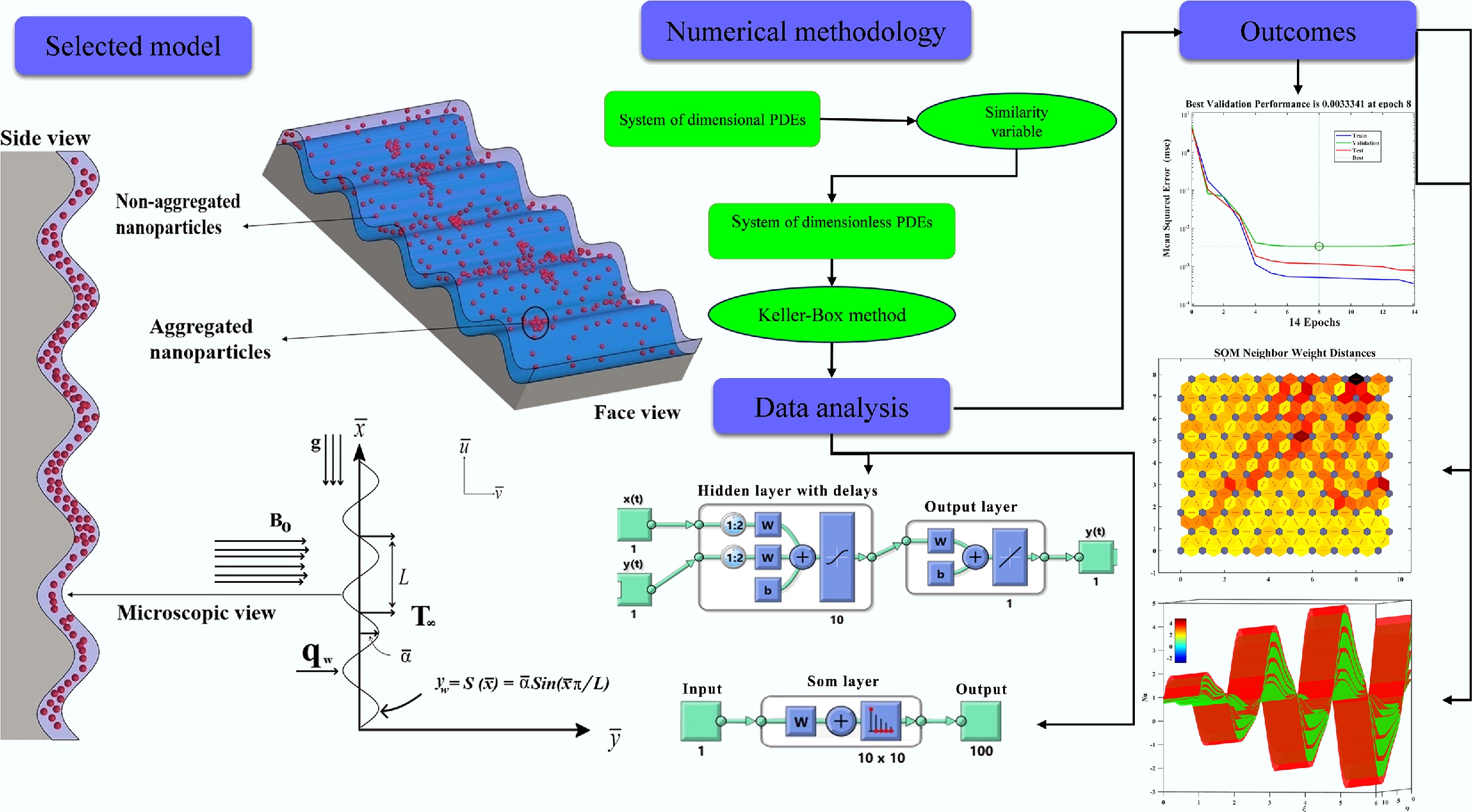

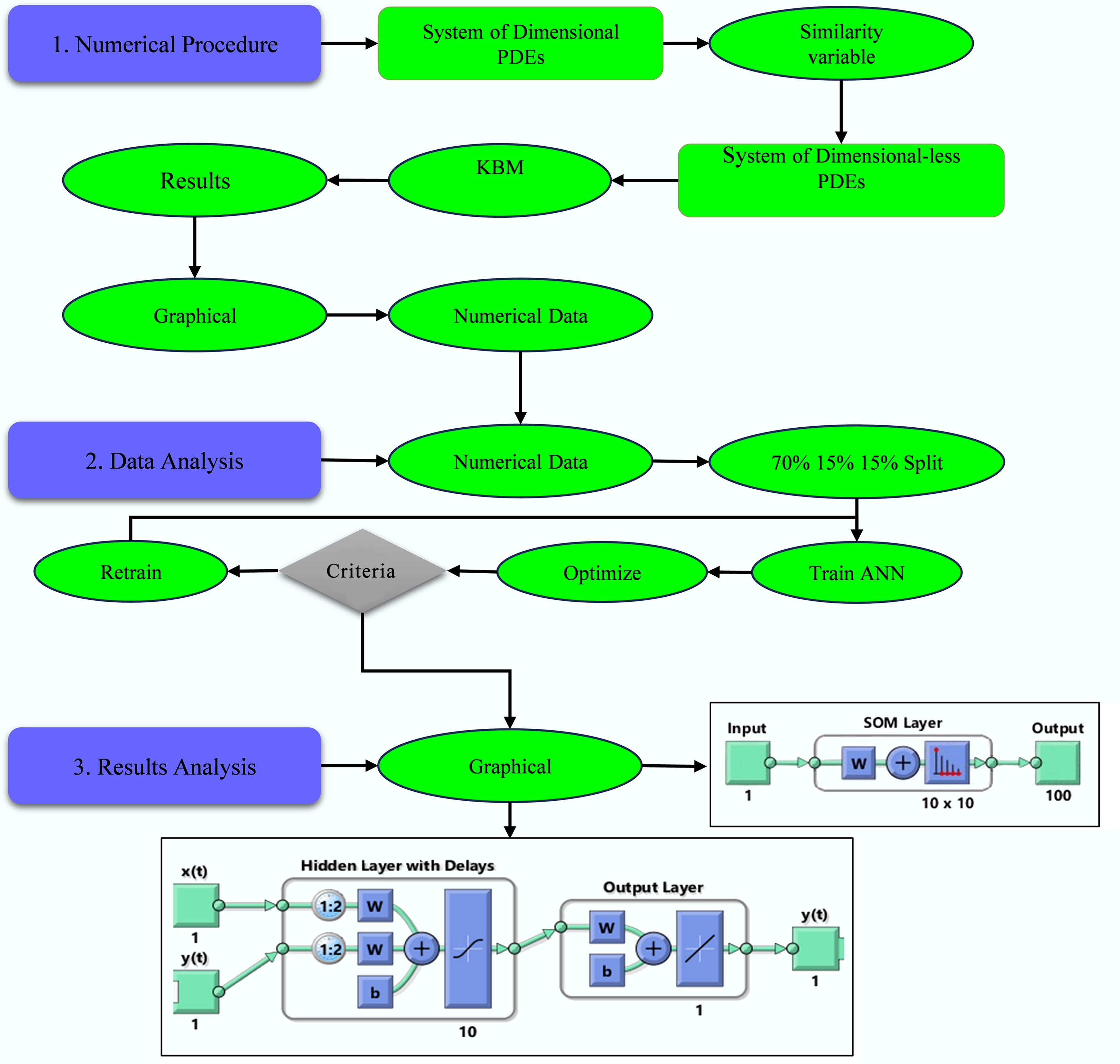

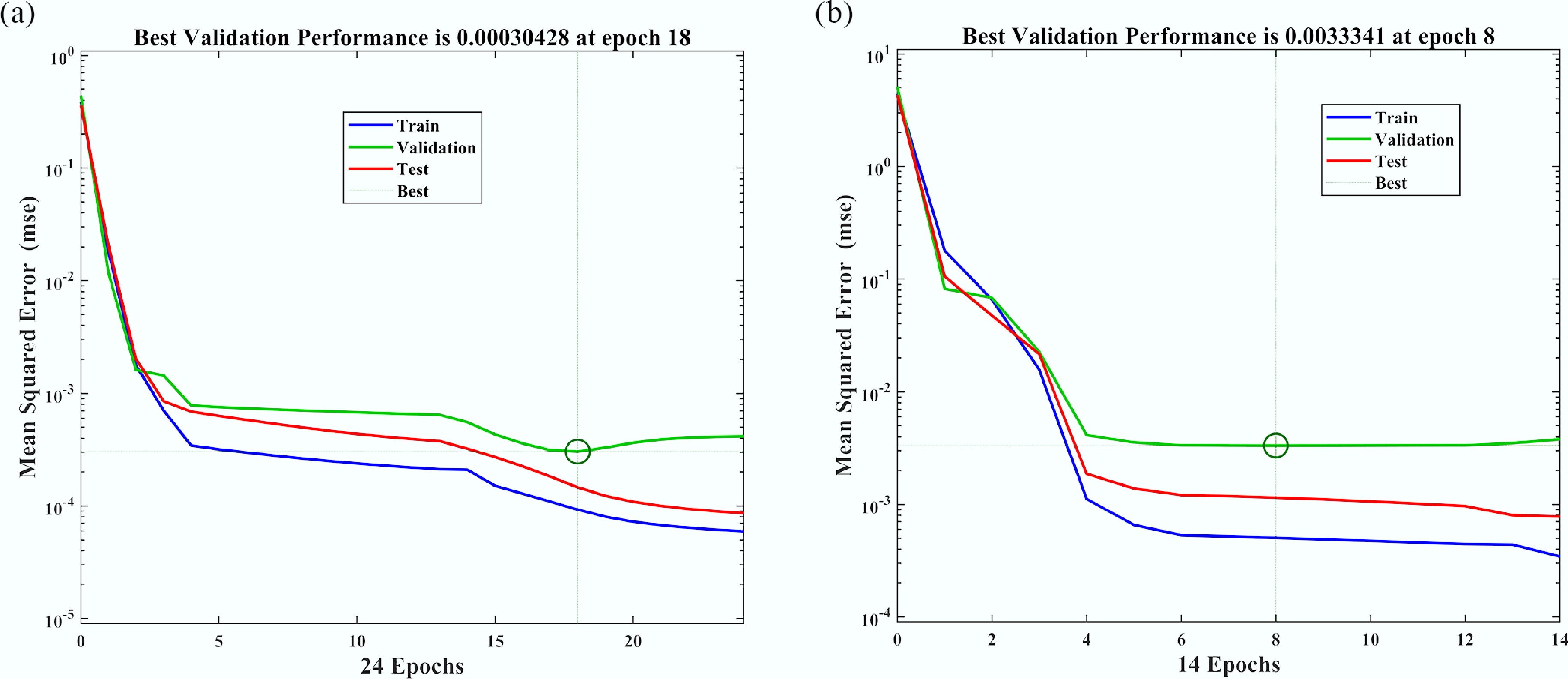

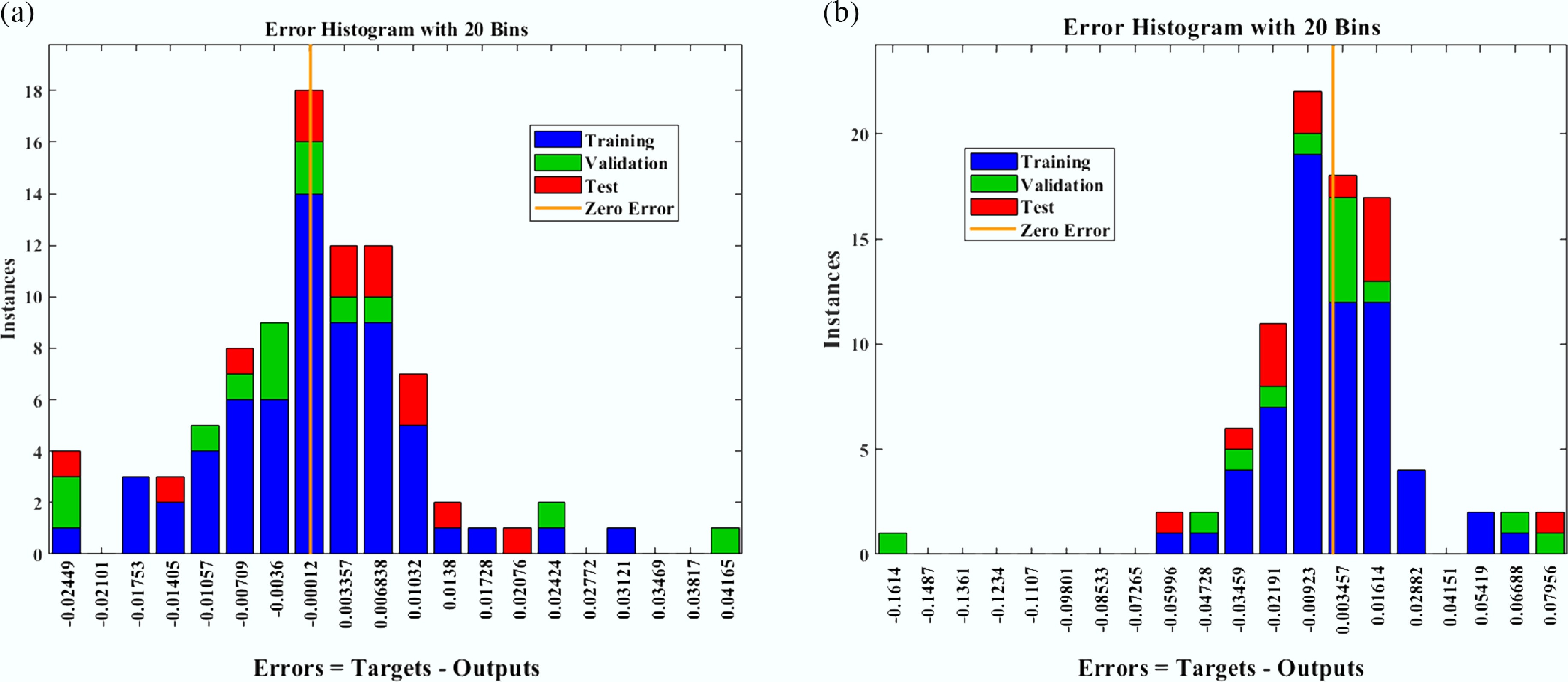

This study develops a computational framework to simulate the flow of nanofluids on a wavy surface under Lorentz forces, considering diamond clusters. Figure 3 shows the flow chart of the numerical study with machine learning patterns of ANNs. Numerical results obtained via the Keller-Box method, integrated with a machine learning (ANN), demonstrate high predictive accuracy, as summarized in Tables 2 and 5. Aggregated cases (e.g., Scenario I B) achieved superior precision (MSE ≤ 10–7) and low validation-testing deviation but required more training time (117–220 epochs) and showed moderate overfitting behavior (MSE ≈ 10–5). The most inaccurate results were obtained in Scenario II B (MSE ≈ 10–4–10–3), which was caused by an unduly small regularization parameter (

$ \mu $ $ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ {\varepsilon }_{T} $

Figure 4.

Mean squared error (MSE) analysis for Nusselt number (Nu) vs sinusoidal parameter ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $) for comparing: (a) non-aggregated, and (b) aggregated nanoparticle configurations.

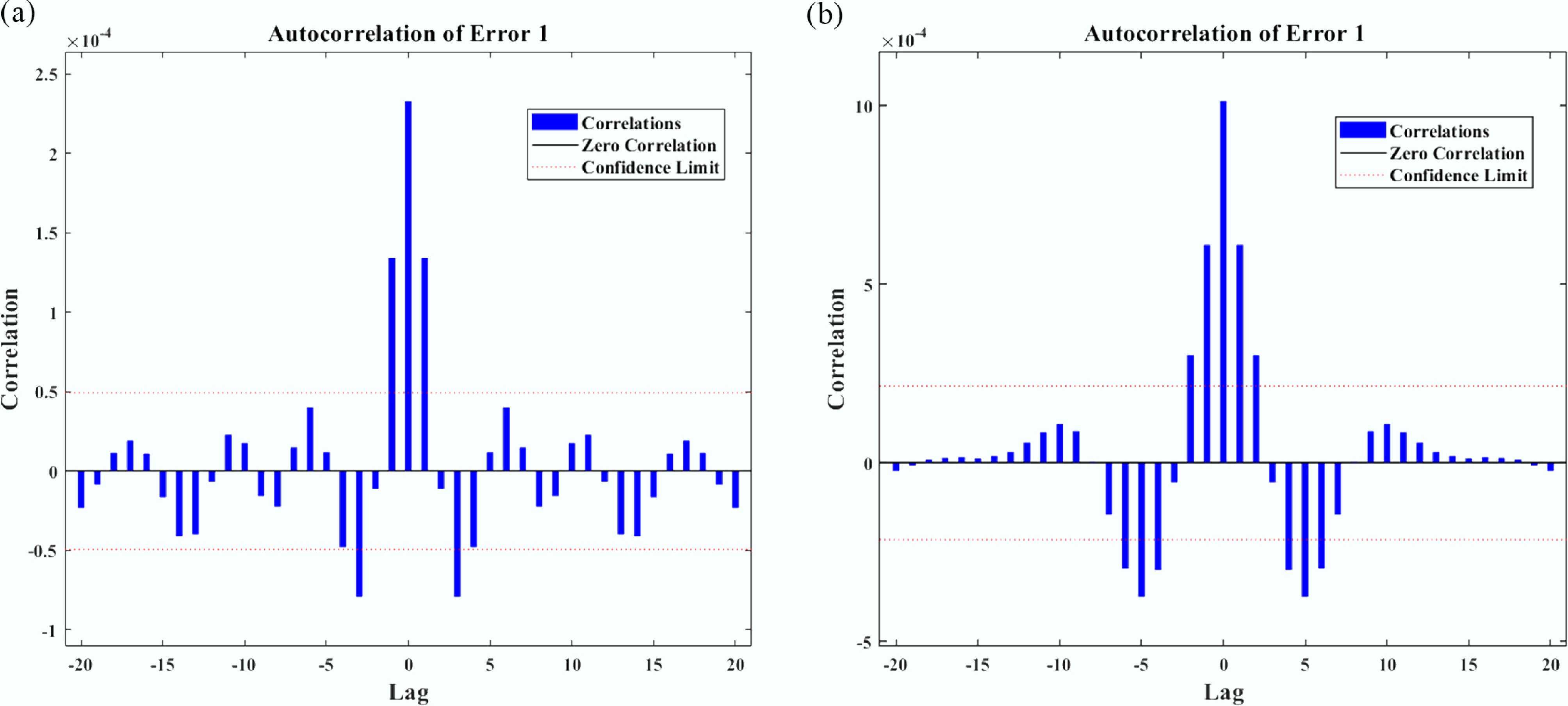

Figure 5.

Error histogram analysis for Nusselt number (Nu) vs sinusoidal parameter ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $) for comparing: (a) non-aggregated, and (b) aggregated nanoparticle configurations.

Figure 6.

Gradient validation analysis for Nusselt number (Nu) vs sinusoidal parameter ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $) for comparing: (a) non-aggregated, and (b) aggregated nanoparticle configurations.

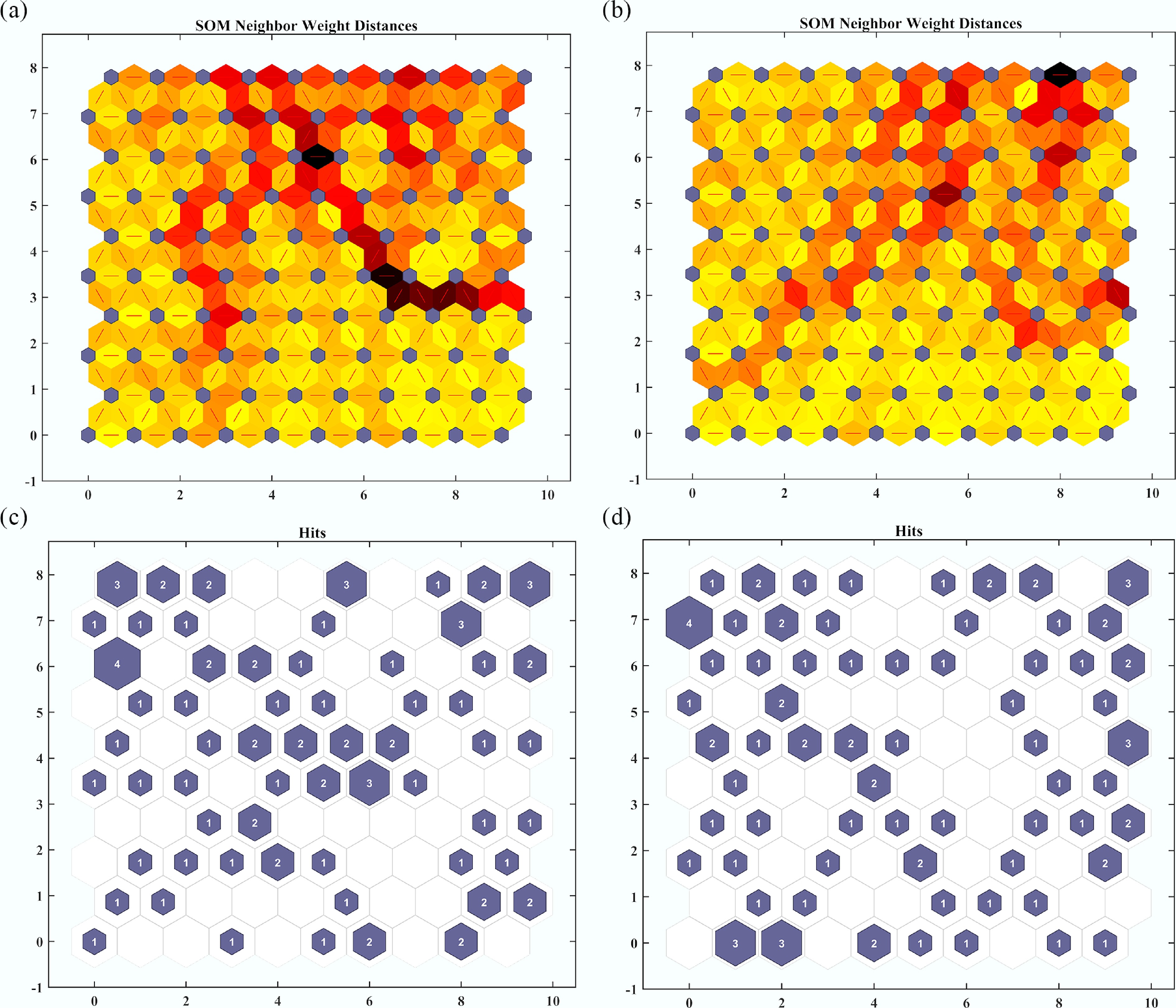

Therefore, the idea of controlled aggregation can be proposed as a useful approach to increase the accuracy, stability, and reliability of the nanofluid under variable conditions. Correlation analysis indicates that different configurations of nanoparticles and various operating conditions interact differently. In the case of the Nusselt number, as shown in Fig. 7a, b, the effect of surface waviness on each configuration is smaller, but the correlations between the geometric variants are at a higher level because aggregated nanoparticles have networked structures that can absorb the disruptions of surfaces.

Figure 7.

Correlation patterns analysis for Nusselt number (Nu) vs sinusoidal parameter ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $) for comparing: (a) non-aggregated, and (b) aggregated nanoparticle configurations.

Consequently, aggregated nanoparticles offer an improved thermal uniformity for complex geometries, whereas non-aggregated ones perform better in strong magnetic fields, which yields a useful design framework for electronic cooling systems and solar collectors in which the geometric influence and magnetic influence need to be reconciled. The clustering analysis also shows that the arrangement of nanoparticles dominates the thermal performance in wavy surfaces. In the non-aggregated nanoparticles, as shown in Fig. 8a, c, both the self-organizing map (SOM) and Hits distributions are broadly distributed, which implies that there is no regular heat transfer at different values of

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $

Figure 8.

Clustering analysis of the Nusselt number (Nu) as a function of the sinusoidal parameter ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $). (a), (b) SOM neighbor weight distance maps, and (c), (d) hit maps, comparing aggregated and non-aggregated nanoparticle configurations.

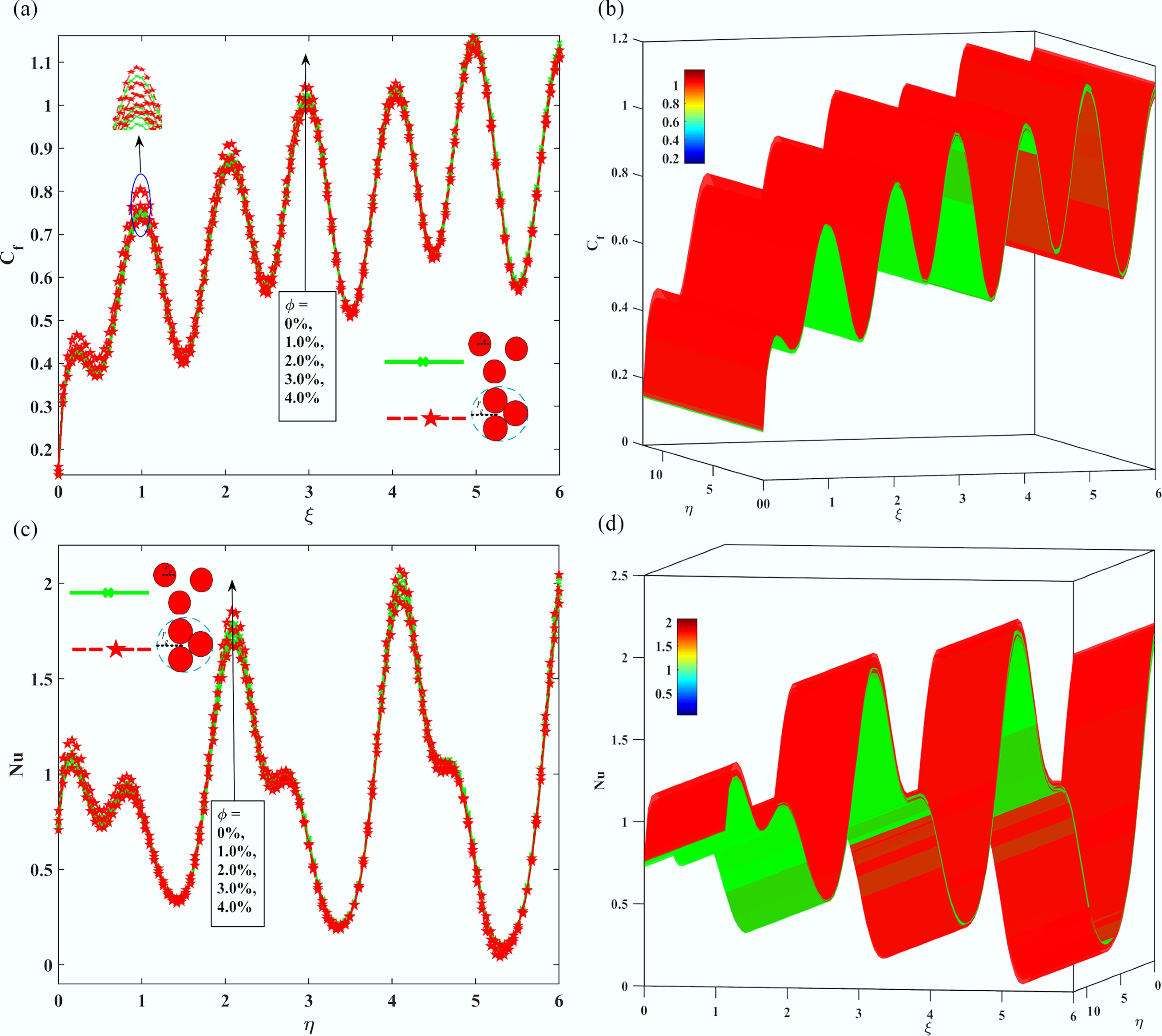

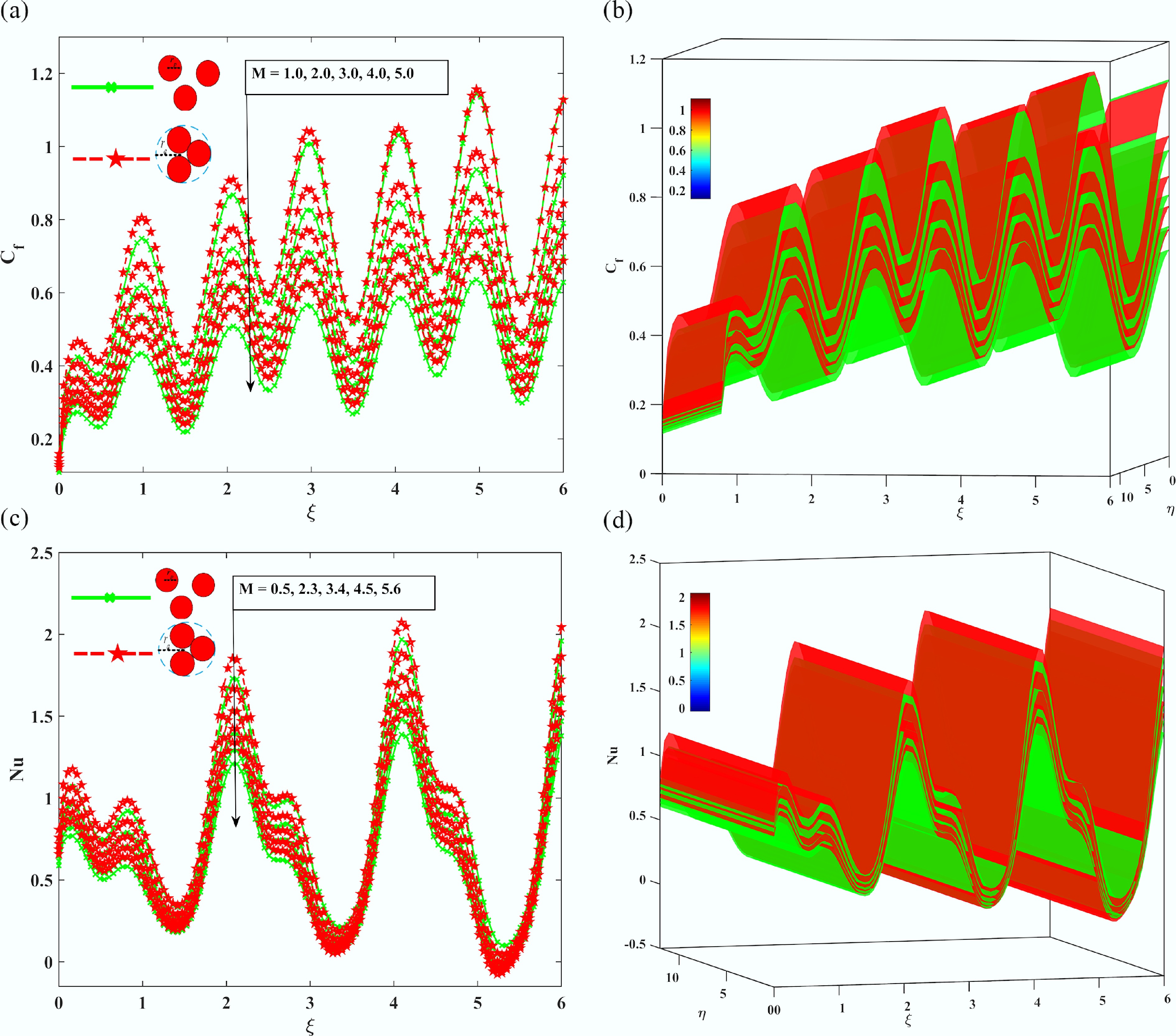

Figure 9a–d below shows how the strength of the magnetic field (M) influences the flow and thermal characteristics of non-aggregated or aggregated nanoparticle-containing nanofluids. Fig. 9a–d indicate that the skin friction coefficient (Cf) decreases significantly with increasing M and aggregated nanofluids always have higher Cf values in comparison with single phases because of increased viscosity and the higher viscosity against the Lorentz force. Aggregated nanoparticles have significantly larger (Cf) at M = 5.0 than non-aggregated nanoparticles by a factor of about 58%.

Figure 9.

The Impact of the magnetic parameter M, on (a), (b) skin friction coefficient Cf, and (c), (d) local Nusselt number Nu.

In contrast, Fig. 9c, d indicate that the Nusselt number, presented in all the cases, which is a measurement of the efficiency of heat transfer, rises and then subsequently falls, peaking in the range M = 2.0–3.0. Such a peak is more pronounced with non-aggregated nanofluids, as they have up to 22% increase in Nu because of the improved dispersion and lower isotropic viscosity. However, beyond M = 3.0, Nu in aggregated nanofluids decreases as the power of Lorentz forces overrides the convective motion. Additionally, the magnetic fields compress surface profiles, enhance Joule heating, and enhance chaining of particles, which are more pronounced in an aggregated system. Further, the initial rise in Nusselt number is due to Lorentz forces stabilizing the flow and suppressing instabilities, boosting convective heat transfer. Beyond an optimum point, the magnetic damping effect dominates, restricting fluid flow, and Joule heating becomes less effective, leading to a decline in surface heat transfer. Figure 10a–d illustrates the impact of the sinusoidal boundary parameter (

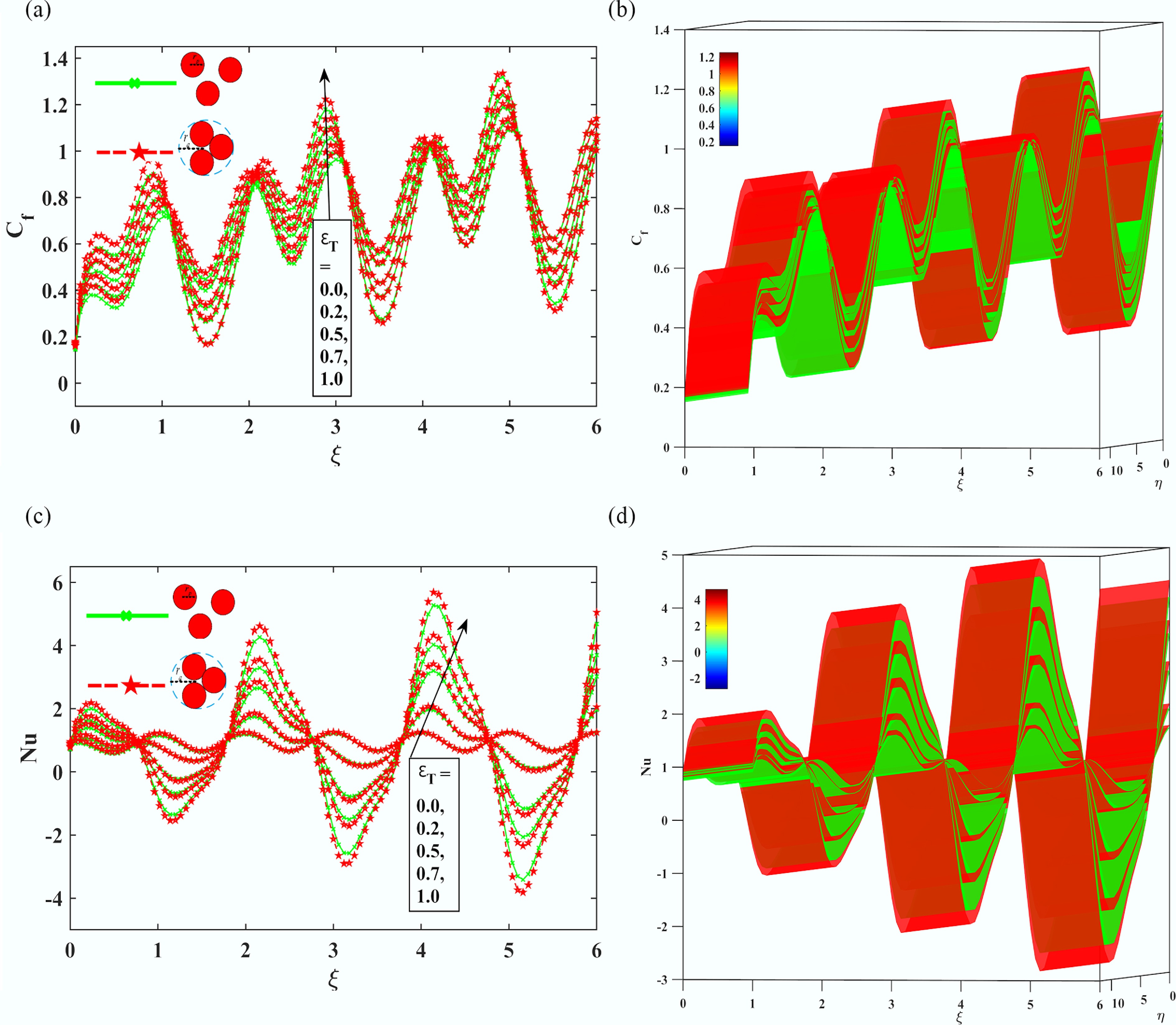

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ {\varepsilon }_{T} $

Figure 10.

The Impact of sinusoidal boundary parameter $ {\varepsilon }_{T} $, on (a), (b) skin friction coefficient Cf, and (c), (d) local Nusselt number Nu.

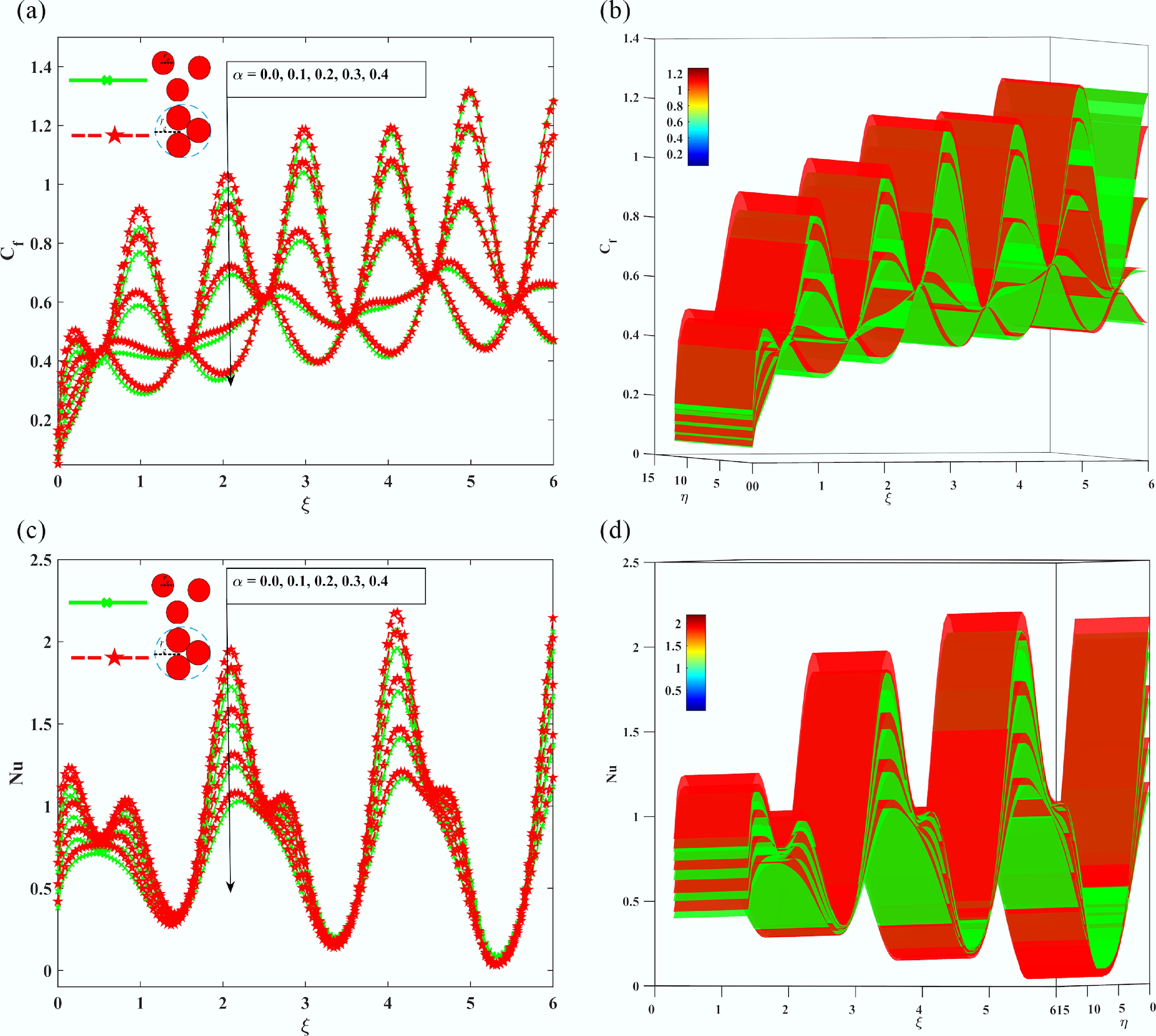

Finally, Fig. 11a–d discusses the effect of the amplitude-to-wavelength ratio (

$ \alpha $ $ \alpha $ $ {C}_{f} $

Figure 11.

The Impact of the wavelength ratio parameter $ \alpha $, on (a), (b) Skin friction coefficient Cf, (c), (d) local Nusselt number Nu.

Nevertheless, the effect of the aggregation eliminates these reductions: aggregated nanofluids have 15%–20% larger Cf because of higher viscosity and momentum diffusion, and 12%–18% larger Nu because of higher thermal conductivity and the development of conductive networks.

For example, the Nusselt number at Nu = 0.2 for the aggregated nanofluids reaches 0.75 compared to 0.6 for the unaggregated ones, representing a 17% improvement in performance, supporting the thermally favorable effect of nanoparticle aggregation. These observations indicate that non-aggregated nanofluids are better suited to systems that are drag-sensitive and need minimal surface perturbations, whereas aggregated nanofluids are beneficial in thermally sensitive systems, even when geometric constraints are present. The results are consistent with and build on prior studies conducted by Shirvan et al.[15], and by Sheremet et al.[16] by quantitatively demonstrating the trade-offs between hydrodynamic drag and heat transfer efficiency.

This research can be of great benefit to designing microfluidic cooling systems and compact heat exchangers, and in such cases, where it is necessary to optimize the balance between frictional loss and thermal performance. To alleviate the heat transfer reduction from surface waves, the set of Figs 10 and 11 suggest: (a) For systems using aggregated nanofluids, restrained waviness (

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ \alpha $ $ \alpha $ $ \phi $ $ \phi $ $ \phi $ $ \phi $ -

This study provides a numerical framework and design guidelines for optimizing thermal management systems using carbon-based diamond-water nanofluids on a wavy surface by integrating machine learning with the Keller-box method. The results indicate that carbon nano-materials clustering boosts thermal conductivity and leads to an up to 30% increase in Nusselt number, albeit a 25% increase in skin friction. Non-aggregated nanoparticles achieved a maximum improvement of 22% in heat transfer, accompanied by lower drag, at optimal magnetic field intensities (M = 2.3–3.4). The geometry of the surface had a substantial effect on the flow structure because too much waviness caused oscillatory flow, which reduced Nu by 15%–20%, and aggregated nanoparticles alleviated this issue by keeping conductive paths open. Moderate magnetic fields (M < 3.4) were found to increase the movement, but stronger fields reduced the movement. Furthermore, the results show that aggregated nanofluids can accommodate a moderate sinusoidal boundary at (

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ \alpha $ -

Future studies will focus on experimental validation of the predicted thermo-hydraulic performance based on a prototype wavy surface under controlled Lorentz force conditions, ensuring consistency with the numerical results. Additionally, a compact multivariate optimization framework will be developed to balance Nu, Cf and pumping power for targeted applications such as wavy-channel heat sinks. Further interpretable machine-learning methods, such as symbolic regression, will be pursued to increase both predictive capability and physical insight. The extension of the study will also include hybrid diamond-metallic nanofluids and turbulent flow conditions. It is planned to extend the current research by developing a more detailed optimization approach with the ANN as a rapid surrogate within algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms to find Pareto-optimal combinations of the key parameters (M,

$ {\varepsilon }_{T} $ $ \alpha $ -

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the conception and design of the study; material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Danial Habib, Caiyan Qin, and Yue Yang; Danial Habib wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52406079), General Program Funding (Grant No. JCYJ20250604145646062), and Stable Support Funding (Grant No. 20231130153633004) by the Shenzhen Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Bureau.

-

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this work.

-

Nonlinear wavy surfaces induce oscillatory heat transfer and turbulent-like dynamics in MHD carbon-based nanofluids.

Carbon-based diamond aggregated nanofluids enhance thermal conductivity, boosting the Nusselt number by 30% despite 25% higher viscous dissipation.

A machine learning analysis hybrid Keller-Box framework achieves exceptional accuracy (MSE ≈ 10−7).

Surface undulations reduce heat transfer by 15%–20%, but aggregation mitigates this through conductive networks.

Optimal performance occurs at 2%–3% nanoparticle volume fraction and moderate magnetic fields (M = 2.3–3.4).

Non-aggregated nanoparticles provide better hydrodynamic performance for flow-sensitive applications.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Habib D, Qin C, Yang Y, Zhang M, Guo Y. 2026. Machine learning analysis of oscillatory-turbulent heat transfer using carbon-based diamond nanofluids over MHD nonlinear wavy surfaces. Sustainable Carbon Materials 2: e005 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0013

Machine learning analysis of oscillatory-turbulent heat transfer using carbon-based diamond nanofluids over MHD nonlinear wavy surfaces

- Received: 11 November 2025

- Revised: 09 December 2025

- Accepted: 18 December 2025

- Published online: 29 January 2026

Abstract: This study presents a comprehensive numerical analysis of the oscillatory heat transfer and of turbulent-flow dynamics of carbon-based diamond-water nanofluids on a vertical nonlinear wavy surface under magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effects. The work highlights the pivotal role of nanodiamonds, a class of carbon nanomaterial characterized by ultra-high thermal conductivity (1,000 W/m·K) and exceptional stability, in enhancing thermal performance. The resulting governing flow model, derived using similarity transformations, is solved by the Keller-box method (KBM) and validated with exceptional accuracy (MSE ≈ 10−7) using an artificial neural network (ANN) for machine learning (ML). Aggregated (ANP) and non-aggregated nanoparticle (NANP) configurations are systematically studied under the rising magnetic field strengths (M = 1.0–5.0) and sinusoidal conditions ($ {\varepsilon }_{T} $= 0.1–0.3). The results show that the formation of ANPs leads to a substantial increase in thermal conductivity due to the formation of conductive clusters, which increase the Nusselt number Nu by 30%, albeit at the considerable cost of a 25% increase in viscous dissipation and skin friction Cf. Conversely, non-aggregated nano-diamonds promote smooth velocity profiles that yield moderate enhancement in Nu (up to 22%) and high hydrodynamic functionality. Surface undulations generate oscillatory thermal dynamics and turbulent mixing structures, resulting in a 15%–20% reduction in the overall Nu due to boundary layer discontinuity. However, this negates the reduction resulting from the increase in overall thermal bridging. An optimal nanoparticle volume fraction Cf of 2%–3% is identified, balancing the thermal enhancement against the pumping power requirements. These results provide important design insights for advanced thermal management systems, especially in the cooling of electronics and high-performance heat exchangers, where magnetic field control and surface geometry optimization are critical for operational efficiency.