-

Under conditions exceeding the critical point of water (647.1 K, 22.1 MPa), its physicochemical properties undergo remarkable transformations. The density, viscosity, and dielectric constant decrease sharply, while the intermolecular hydrogen bond network becomes weakened or even disrupted. Consequently, the polarity of water is substantially reduced, and its behavior resembles that of organic solvents. This transformation endows supercritical water (SCW) with excellent solubility for a wide range of organic compounds and gases, while markedly enhancing its diffusivity, permeability, and mass transport capability, making it a promising green reaction medium[1]. Owing to these unique characteristics, SCW has been widely applied in various fields, including the treatment and valorization of waste plastics, in situ extraction of coal and petroleum, and biomass conversion[2−5]. In supercritical water gasification (SCWG) processes, aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons typically serve as key precursors or intermediates. These species coexist with SCW within nanoporous media such as coal seams, shale formations, and waste polymer matrices. Such nanoconfined environments can significantly alter the diffusion, adsorption, and reaction kinetics of fluids, thereby resulting in systems with distinctive physicochemical properties[6,7].

In recent years, extensive theoretical and experimental efforts have been devoted to understanding the structure and transport properties of nanoconfined fluids. Leoni et al. investigated fluid behavior under 2D confinement and found that the microscopic structure, dynamics, and thermodynamic properties of fluids at the nanoscale differ substantially from those of the bulk phase[8]. Compared with simple liquids or conventional organic solvents, water exhibits more complex and unique diffusion and spatial distribution characteristics in confined environments due to its strong intermolecular interactions and directional hydrogen bond network. Zhang et al. examined the structural evolution and physical properties of subcritical and supercritical water confined in one-dimensional channels, revealing the atypical physicochemical behavior of nanoconfined SCW[9,10]. These studies indicate that the transport behavior of water in nanopores is jointly influenced by thermodynamic parameters (e.g., temperature and pressure), the stability of the hydrogen bond network, and the confinement scale. Regarding organic systems, Yang et al. studied the diffusion of alkanes with varying chain lengths inside single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and found that their confined diffusion strongly depends on tube diameter and molecular flexibility[11]. Nie et al. combined experiments and simulations to explore the phase transition and diffusion characteristics of n-hexane within carbon nanotubes (CNTs). Their results demonstrated that confinement lowers the melting point and phase transition enthalpy of alkanes while enhancing molecular self-diffusion[12]. For aromatic systems, Fomin et al. reported that benzene molecules confined in small-diameter SWCNTs (6.9 Å) preferentially adopt a tilted orientation and exhibit extremely low diffusion coefficients, indicating pronounced suppression of aromatic diffusion under nanoscale confinement[13]. Moreover, Shishehbor et al. simulated the dynamics of aromatic hydrocarbons, alkanes, and asphaltenes on oxidized CNT surfaces, revealing that aromatic species become nearly immobile under oxidative modification, highlighting the critical role of strong wall–aromatic interactions in limiting molecular mobility[14].

Previous studies have demonstrated that when fluids are confined within nanoscale confinements, their diffusion, adsorption, and microscopic structural properties undergo pronounced changes, which are collectively referred to as the nanoconfinement effect[15,16]. Most existing investigations have primarily focused on the transport and phase-transition behavior of single-component fluids or individual molecules within idealized nanostructures such as CNTs and graphene sheets, revealing the significant influence of confinement on molecular orientation, diffusion, and structural evolution. In contrast, studies concerning mixed systems, particularly those involving the coexistence of SCW and organic molecules, remain relatively scarce. Current research on nanoconfined binary fluids has mainly concentrated on systems composed of SCW and small gas molecules (e.g., H2, CO, CO2, CH4)[17], whereas the transport properties of more complex organic species, such as aromatics and alkanes, under confined SCW conditions are still largely unexplored. In particular, how molecular structural differences regulate the layering structure, orientational configurations, and diffusion modes of confined SCW–organic systems, and how variations in pore size and temperature induce shifts in structure–dynamics coupling mechanisms, remain key scientific questions that have not been systematically addressed in existing literature. These knowledge gaps hinder a deeper understanding of the fundamental cooperative interactions between SCW and organic molecules and limit the mechanistic understanding, design, and optimization of SCWG and other nanoscale confined reaction processes.

Under supercritical conditions, the microscopic interactions between SCW and organic molecules play a crucial role in determining reaction pathways, product distributions, and molecular migration processes[18,19]. Moreover, within nanoscale confinement, the distinctive physicochemical characteristics of SCW can be further amplified or modified, leading to transport behaviors that differ substantially from those observed in the bulk phase[20]. Therefore, a systematic investigation of the structural and dynamical features of aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons in nanoconfined SCW systems is essential, not only for elucidating how molecular structure influences diffusion and adsorption in confined fluids, but also for providing theoretical insight into the optimization of SCW-based technologies for in situ coal extraction, plastic pyrolysis, and biomass gasification. However, traditional experimental techniques are limited by instrumentation and characterization capabilities, which makes it difficult to directly observe fluid behavior within nanoscale confined spaces under high-temperature and high-pressure supercritical conditions. As a result, it is often challenging to resolve the key microscopic mass-transfer details. In contrast, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation offers advantages such as low computational cost, high spatiotemporal resolution, and the ability to track particle trajectories at the atomic scale, allowing direct access to detailed information on diffusion, adsorption, and interaction energies of confined fluids. MD simulations have been widely demonstrated to be an effective and reliable research approach, and numerous studies have used this method to provide accurate and reliable predictions of the microstructure and transport properties of nanoscale confined systems[21−23].

In this work, MD simulations were employed to explore the cooperative mass transport and microscopic characteristics of SCW in binary mixtures with representative organic molecules, namely aromatics (benzene, naphthalene, anthracene) and alkanes (methane, ethane, propane), under nanoscale confinement. SWCNTs were selected as model one-dimensional confinement channels due to their tunable pore sizes and exceptional mechanical and thermal stability, making them ideal platforms for investigating transport phenomena in confined fluids[24,25]. The effects of confinement scale (CNT diameters ranging from 20.36 to 40.68 Å), temperature (673–973 K), solute molar concentration (1%–30%), and solute molecular size (number of aromatic rings or alkane chain length) on key transport and structural parameters, such as diffusion coefficients, hydrogen bond networks, radial distributions, and energy distributions profiles, were systematically analyzed. The simulation conditions were designed to represent typical SCWG operation parameters (T = 673–973 K, P = 25 MPa)[26−28]. Based on these considerations, this study aims to elucidate the coupled effects of solute molecular structure, pore size, and temperature on the behavior of confined SCW-organic systems. The findings not only deepen the understanding of cooperative mass transport and structural rearrangements between SCW and organic molecules under nanoscale confinement but also provide molecular-level insights to support the optimization of SCWG operating conditions, the regulation of pore-scale reaction processes, and the design of nanoscale energy materials.

-

In this study, two types of nanoconfined binary systems, SCW–aromatic hydrocarbons and SCW–alkanes, were constructed to investigate how differences in solute molecular structure affect the transport behavior of confined fluids. The solute molecules were constructed using the Materials Studio software package[29], including aromatic hydrocarbons containing one to three benzene rings (benzene, naphthalene, and anthracene) and alkanes containing one to three carbon atoms per molecule (methane, ethane, and propane), representing typical π-conjugated and saturated hydrocarbon structures, respectively. Water molecules were modeled using the classical three-site SPC/E model, with intramolecular bond lengths and angles constrained via the SHAKE algorithm (with a tolerance of 1 × 10–4) to maintain molecular rigidity during simulations[30]. This model has been extensively validated and shown to reproduce the thermodynamic and dynamic properties of SCW under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions with high accuracy[31,32]. The solute molecules were described using the OPLS-AA force field, which provides high fidelity in reproducing the thermophysical properties of organic liquids, such as density and enthalpy of vaporization, and has proven reliable in calculating diffusion and conformational energy landscapes for both aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons[33,34]. The confining channels were constructed based on the classical SWCNT model proposed by Saito et al.[35,36]. To avoid introducing additional structural factors that may influence the transport behavior of confined fluids, the CNTs were treated as ideal rigid walls without vacancies, edge defects, or other surface imperfections. This model has been widely employed to study energy and mass transport phenomena of fluids under one-dimensional confinement. Armchair CNTs with chirality indices (n, n) were generated using the Nanotube Builder module in the VMD software package[37]. The rolling geometry and topological structure of the nanotube are fully determined by its chirality index, and the wall carbon atoms form an sp2-hybridized hexagonal lattice. CNT diameter was calculated using:

$ D=\dfrac{\sqrt{3}na}{\pi } $ (1) where, α = 2.46 Å is the graphene lattice constant. Based on this relationship, CNTs with n = 15, 19, 22, 26, and 30 were selected, corresponding to diameters of approximately 2.0–4.0 nm (geometric parameters are provided in Table 1). The axial length of each CNT was determined and adjusted according to the initial density and axial pressure requirements of the system. The chosen pore sizes are sufficient to accommodate the largest solute molecule (anthracene) while covering a representative range of confinement strengths, from strong confinement to near bulk behavior[38].

Table 1. Structural parameters of the simulated CNTs, including chirality, geometric diameter (d), and effective inner diameter (deff)

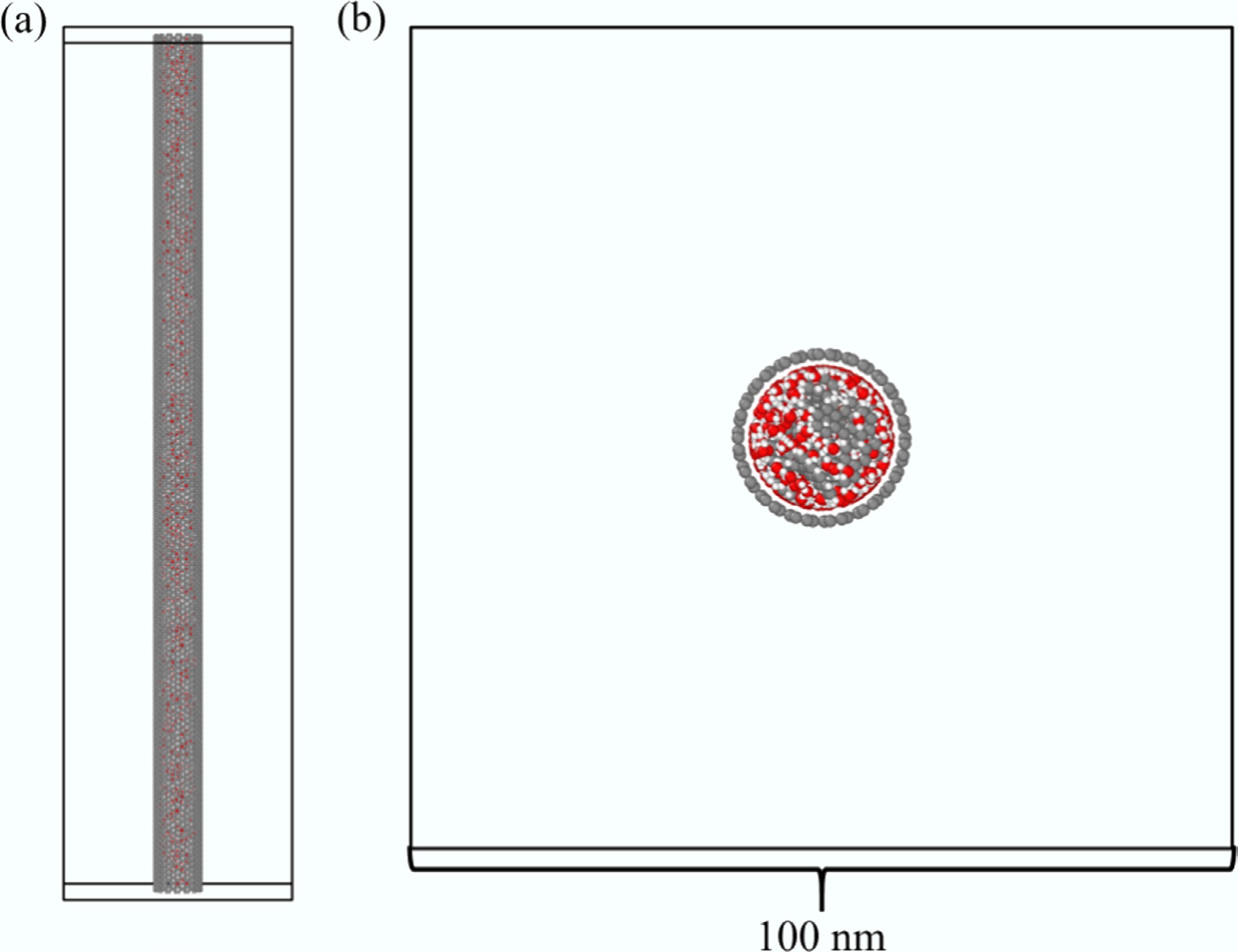

CNT d (Å) deff (Å) (15,15) 20.34 16.94 (19,19) 25.76 22.36 (22,22) 29.83 26.43 (26,26) 35.26 31.86 (30,30) 40.68 37.28 Previous studies have demonstrated that for CNTs with diameters larger than approximately 2 nm, the rigidity or flexibility of the nanotube has a negligible effect on the simulated transport properties of confined fluids[39,40]. Therefore, in this work, all CNT atoms were treated as rigid during the simulations to eliminate the influence of wall vibrations on the system dynamics. The axial length of each CNT was adjusted according to the preset density of the confined fluid. To avoid boundary artifacts such as molecular accumulation or escape near the CNT ends, three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied. The simulation box size in the x–y plane was set to 100 nm to minimize interference from periodic image interactions. To reproduce the typical operating conditions of SCWG under isothermal and isobaric environments[41,42], the axial pressure was used as a unified reference for constructing all simulation systems. During the pre-equilibration stage, the axial length of the CNT was adjusted so that the confined fluid naturally converged to a stable pressure of approximately 25 MPa, with fluctuations controlled within ±1 MPa. This approach effectively avoids non-physical density deviations caused by differences in the effective occupied volume of various solutes and concentrations, thereby enhancing the comparability among different systems. In all simulations, the number of water molecules was fixed at 3,000, while the number of solute molecules was adjusted according to the specified molar concentration. The molecules were packed into the pre-constructed CNT using the Packmol software package[43]. The initial configuration of the simulated systems is illustrated in Fig. 1.

All MD simulations were performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) package[44]. The short-range van der Waals interactions between particles were described using the Lennard–Jones (LJ) potential with a cutoff radius of 12 Å. The LJ potential is expressed as[45]:

$ {U}_{lj}=4\varepsilon \left[{\left(\dfrac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{12}-{\left(\dfrac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{6}\right] $ (2) where, Uij is the LJ potential energy, ε is the well depth, σ is the distance at which the LJ potential equals zero, and r is the interparticle distance. For interactions between different particle types, the LJ parameters were obtained using the Lorentz–Berthelot combining rules[46,47]:

$ {\varepsilon }_{ij}=\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{i}{\varepsilon }_{j}} $ (3) $ {\sigma }_{ij}=\sqrt{{\sigma }_{i}{\sigma }_{j}} $ (4) The long-range electrostatic interactions were modeled using the Coulomb potential and computed via the Particle–Particle Particle–Mesh (PPPM) algorithm. In this study, the PPPM accuracy was set to 10–4[48]. The electrostatic potential is given by:

$ {U}_{coul}=\dfrac{{q}_{i}{q}_{j}}{4\pi {\varepsilon }_{0}r} $ (5) where, Ucoul is the Coulomb potential energy, qi and qj are the charges of particles i and j, respectively, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, and r represents the interparticle distance.

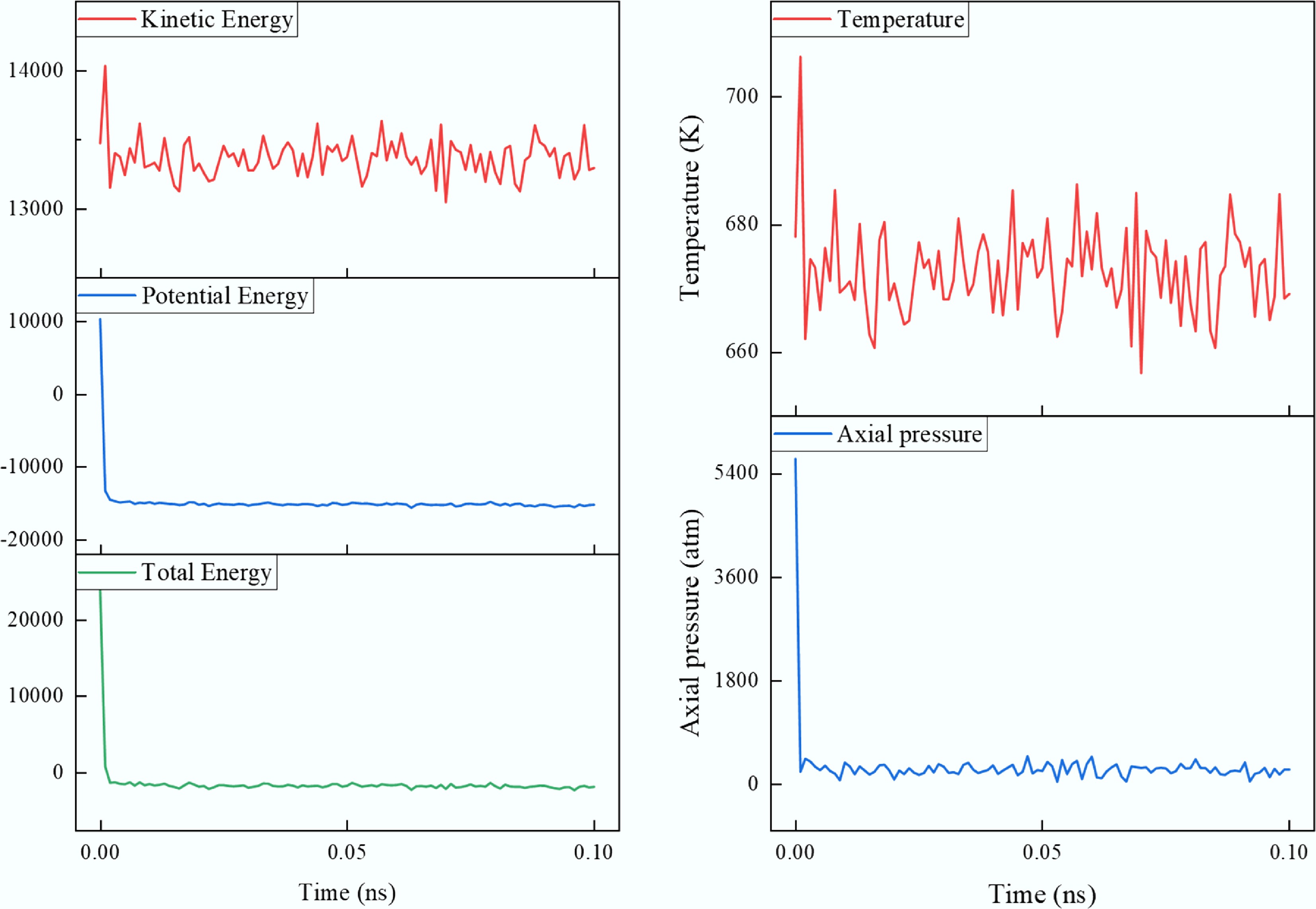

Prior to equilibration, energy minimization of all systems was performed using the conjugate gradient algorithm[49]. The force convergence criterion was set to ftol = 1.0 × 10–6, with a maximum of 10,000 iterations[50], to eliminate any unfavorable short-range contacts in the initial configurations. Subsequently, a 0.1 ns pre-equilibration was performed under the NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature), during which the system rapidly converged to a stable structure (Fig. 2). This was followed by a 10 ns production simulation under the same conditions. The system temperature was controlled using the Nosé–Hoover thermostat, with a time integration step of 1 fs. Trajectory data were recorded every 0.1 ps for subsequent structural and dynamical analyses.

The self-diffusion coefficients of fluid species were evaluated using the mean square displacement (MSD) method. Under strong confinement, molecular motion in the radial (x, y) directions is severely restricted, and diffusion predominantly occurs along the CNT axis (z). Accordingly, the center of mass of each molecule was used as the tracking reference, and only the MSD along the z-axis was calculated to characterize one-dimensional diffusion behavior within the confined channel. The axial self-diffusion coefficient Dz,i, for species i was determined according to the one-dimensional Einstein relation:

$ {D}_{z,i}=\underset{t\rightarrow \mathrm{\infty }}{\lim }\dfrac{1}{2{N}_{i}t}\left\langle \sum\limits_{j=1}^{{N}_{i}}\left({z}_{j}(t)-{z}_{j}(0)\right)\right\rangle $ (6) where, Ni is the number of molecules of species i, t is the elapsed time, and <···> denotes ensemble and time averaging over different initial configurations. The prefactor 1/2 corresponds to one-dimensional diffusion (it would be 1/6 for three-dimensional systems). To ensure statistical accuracy, the linear fitting of the MSD–t curve was performed over the 10%–90% time window of the simulation, thereby minimizing the effects of initial relaxation and statistical noise on the calculated diffusion coefficients.

-

Before performing production simulations, a validation test was conducted to verify the reliability of the selected force field parameters and the constructed molecular model. The self-diffusion coefficient was chosen as the primary evaluation metric. Specifically, the self-diffusion coefficients of bulk water and two representative solutes, benzene (aromatic hydrocarbon) and methane (alkane), in aqueous solution were calculated and compared with the corresponding experimental data reported by Lamb et al. (Table 2). Due to the limited availability of experimental data, only the diffusion coefficients of water and benzene under supercritical conditions, as well as that of methane at ambient temperature, could be used for comparison. As shown in Table 2, the deviations between the simulated and experimental values are within 7%, which falls well within an acceptable error range. This close agreement confirms that the employed force field parameters and simulation methodology can accurately reproduce the diffusion behavior of both water and organic molecules, thereby providing a solid theoretical foundation for subsequent investigations of SCW–organic binary systems under CNT confinement.

Table 2. Comparison between simulated and experimental self-diffusion coefficients of bulk water and representative solute molecules

Effect of confinement size

-

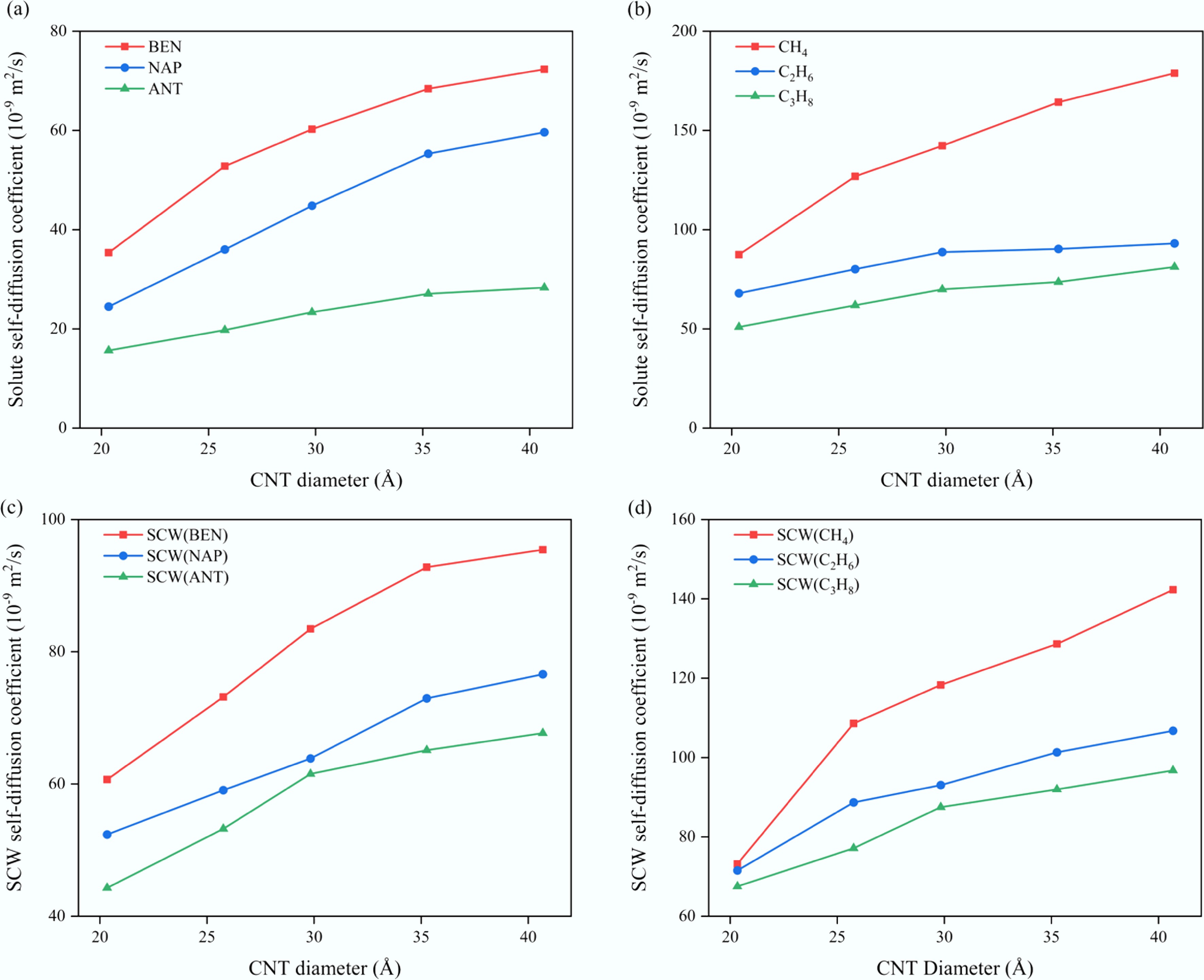

The self-diffusion coefficient is a fundamental kinetic parameter that characterizes molecular mobility and mass transport capability within a system. To investigate the effect of confinement size on transport properties, the self-diffusion coefficients of each component in SCW–organic solute systems were evaluated under typical SCWG conditions (673 K, 25 MPa) with a fixed solute molar concentration of 10% (Fig. 3). Overall, both the aromatic (Fig. 3a, c) and aliphatic (Fig. 3b, d) systems exhibit a pronounced increase in self-diffusion coefficients with the enlargement of CNT diameter. This trend indicates that as the confinement space expands, the wall-induced restriction on fluid molecules weakens, allowing enhanced molecular mobility and consequently higher diffusion rates.

Figure 3.

Variation of self-diffusion coefficients with CNT diameter for (a) aromatic solutes, (b) aliphatic solutes, (c) SCW in aromatic systems, and (d) SCW in aliphatic systems.

As shown in Fig. 3a, b, solute self-diffusion coefficients decrease with increasing molecular size, and the alkanes exhibit consistently higher diffusion coefficients than the aromatics. This difference primarily arises from the larger molecular volume of aromatics and the intermolecular attraction induced by their π-conjugated structures, which jointly promote π–π stacking and molecular clustering. These effects further suppress molecular diffusion within confined spaces[54−56]. Notably, when the CNT diameter exceeds approximately 35 Å, the growth rate of the diffusion coefficient in aromatic systems diminishes significantly, indicating a gradual attenuation of confinement effects and a transition toward bulk-like behavior. In contrast, this transition occurs at smaller diameters (25–30 Å) in the alkane systems, suggesting that different solute types exhibit distinct sensitivities to the confinement scale. Further analysis of the diffusion behavior of SCW (Fig. 3c, d) reveals that the molecular structure and size of the solute not only determine its own mobility but also substantially influence the overall diffusion characteristics of the confined fluid. Compared with the SCW–methane system (with the smallest solute molecule), the self-diffusion coefficient of the solute in the SCW–anthracene system decreases by 82.1%–84.4%, while that of SCW decreases by 39.5%–52.4% at the same CNT diameter. These results indicate that large aromatic solutes markedly inhibit molecular mobility within the confined environment, thereby reducing the overall mass transfer efficiency of the system.

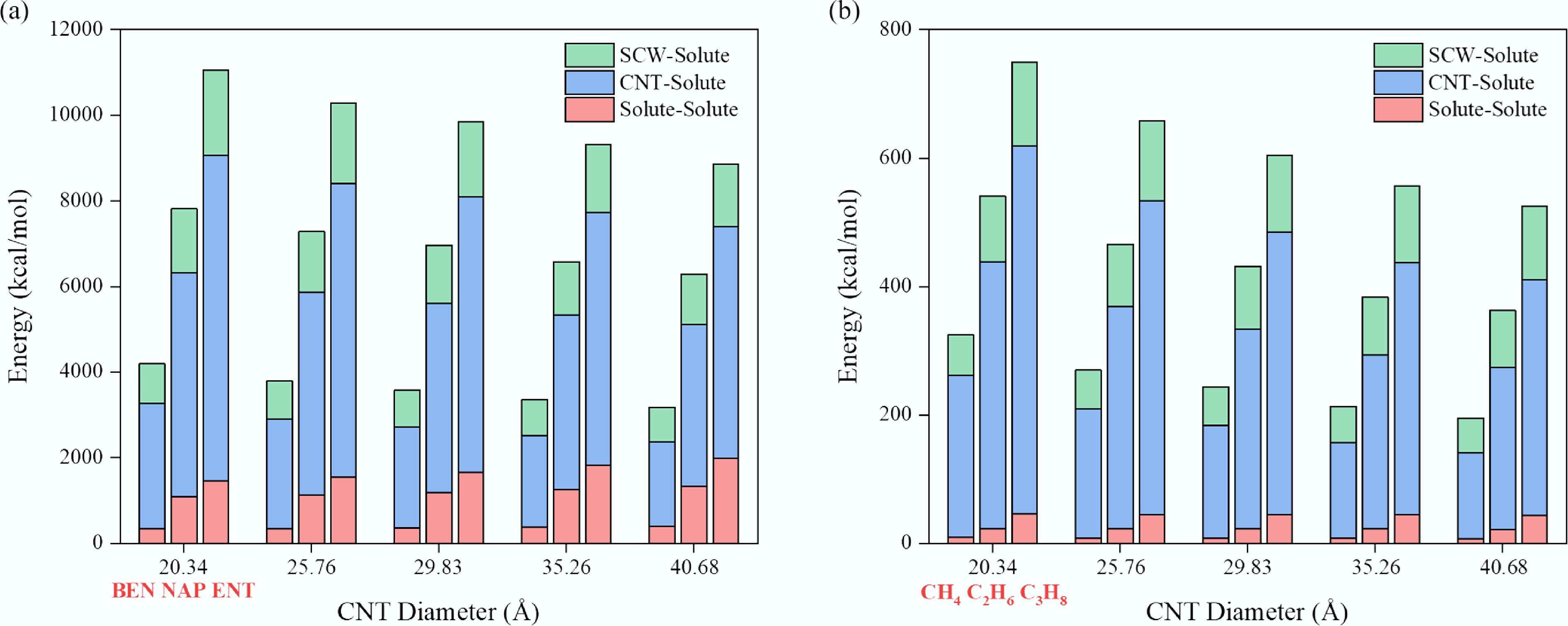

To further elucidate the microscopic origin underlying the differences in diffusion behavior induced by solute molecular structure, the interaction energies between the solute and other components (SCW, CNT, and solute molecules) were calculated as a function of CNT diameter (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4a, the total interaction energy of the SCW–aromatic systems is approximately one order of magnitude higher than that of the SCW–alkane systems (Fig. 4b). In both cases, the total interaction energy decreases progressively with increasing CNT diameter, indicating that the enlargement of the confinement space allows greater configurational freedom for the confined fluid, thereby leading to a lower-energy and more stable structural state.

Figure 4.

Variation of intermolecular interaction energies among system components as a function of CNT diameter. (a) Aromatic systems (benzene, naphthalene, and anthracene at each diameter). (b) Aliphatic systems (methane, ethane, and propane at each diameter).

In terms of energy composition, the CNT–solute interaction contributes dominantly to the total energy in both systems, accounting for approximately 60%–80%. The continuous decline of this interaction with increasing CNT diameter is the primary factor driving the overall reduction in system energy. This result highlights the crucial influence of CNT walls on the molecular dynamics of confined fluids. Moreover, the CNT–solute interaction is substantially stronger in aromatic systems than in aliphatic ones, reflecting the pronounced attraction between π-conjugated aromatic molecules and the CNT surface. Notably, as the CNT diameter increases from 20.34 Å to 40.68 Å, the solute–solute interaction energy in alkane systems exhibits only a slight decrease (less than 3 kcal/mol), whereas in aromatic systems, it shows an opposite trend—rising by 15.38%, 21.81%, and 37.59% for benzene, naphthalene, and anthracene, respectively. This counterintuitive behavior indicates that aromatic molecules undergo significant structural rearrangement under confinement. This observation is consistent with the findings of Rapacioli et al.[57], who demonstrated that aromatic molecules tend to form stable clusters through π–π stacking, and that the stability of such aggregates increases with the number of aromatic rings. Additionally, strong π–π adsorption interactions between aromatic rings and the CNT wall have been reported[58]. Consequently, in narrow CNTs, spatial confinement restricts parallel alignment and effective stacking between aromatic rings, thereby weakening solute–solute interactions. As the confinement space expands, molecular orientational freedom increases, facilitating the formation of stable π–π stacked structures among aromatic molecules.

To elucidate the configurational distribution characteristics of fluid molecules under nanoscale confinement, the radial number density profiles of solute molecules inside CNTs with different diameters were calculated. Specifically, the CNT cross section was divided into 25 concentric annular regions of equal width along the radial direction, with the CNT axis as the center (Fig. 5). Within the final 0.1 ns of the simulation, the number of solute molecules in each radial annular region was counted based on the positions of their centers of mass, and a time average was taken to obtain the radial number density distribution under equilibrium conditions. The number density, ρᵢ, was computed according to the following expression:

$ {\rho }_{i}=\dfrac{{N}_{i}}{{V}_{i}}=\dfrac{{N}_{i}}{\pi (r_{out}^{2}-r_{in}^{2})\cdot L} $ (7) where, ρi is the average number density in the i-th annular region (units: molecules/Å3), Ni is the number of solute molecules within that region, rin and rout denote the inner and outer radii of the annular region, respectively, and L represents the axial length of the CNT.

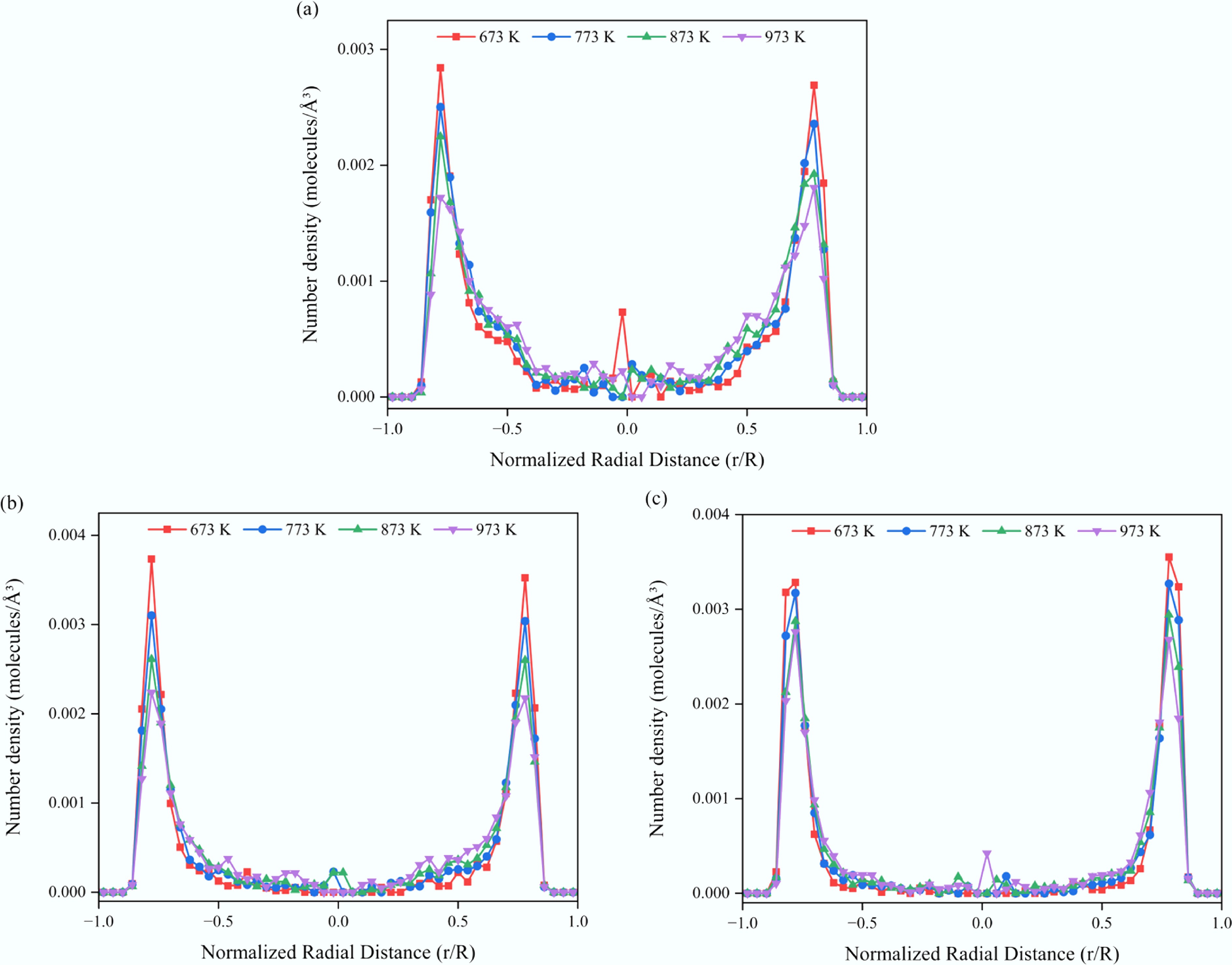

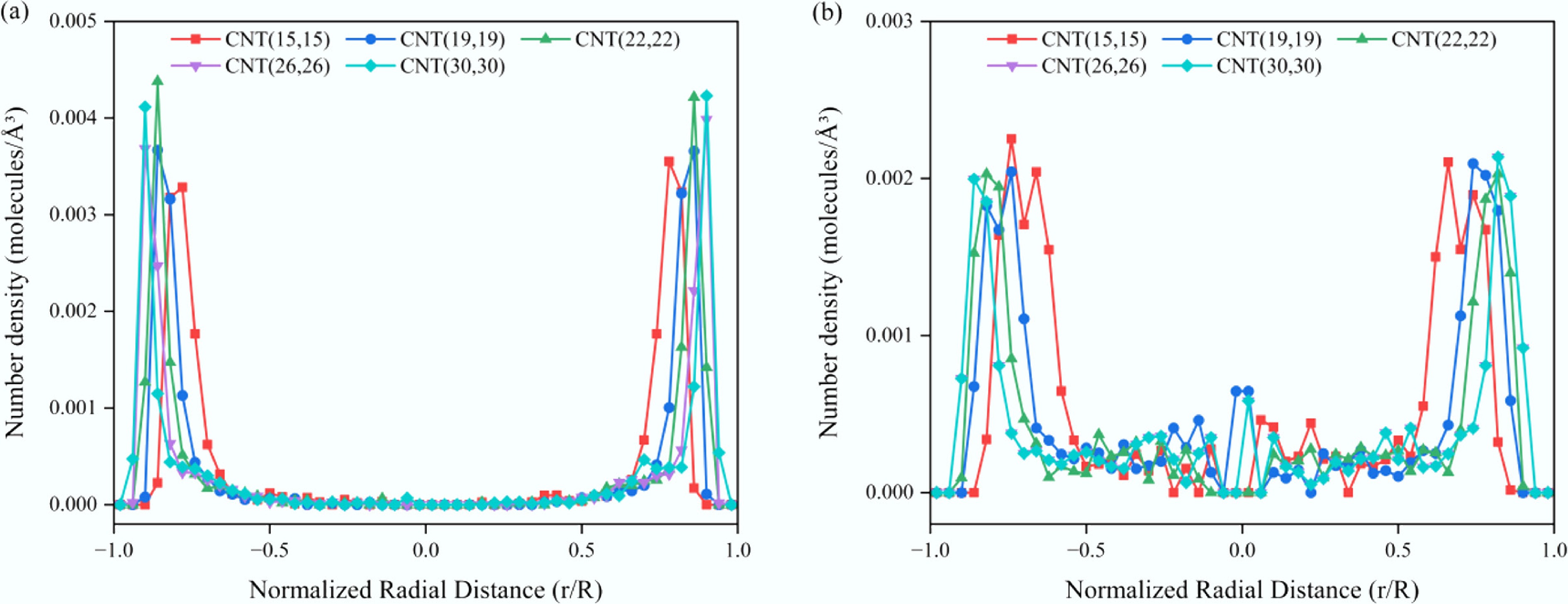

Figure 6 shows the radial number density distributions of two representative solutes, anthracene and propane, within CNTs of varying diameters, using the dimensionless radial distance (r/R) as a characteristic variable. Overall, in all systems, a distinct adsorption layer forms near the CNT inner wall, indicating preferential accumulation of solute molecules near the surface, whereas the central region of the pore remains sparsely populated. With increasing CNT diameter, the intensity of the near-wall density peak becomes sharper, suggesting that solute molecules tend to form a more well-defined adsorption layer in wider confinement spaces. A comparison between the aromatic (Fig. 6a) and aliphatic (Fig. 6b) systems further reveals that the peak density of aromatics is significantly higher and consistently located adjacent to the CNT wall. Although the orientational freedom of aromatic molecules increases with the widening of the confinement, they still exhibit a strong tendency to form a dense adsorption layer near the wall. This adsorption characteristic is consistent with the diffusion results discussed earlier: within confined CNT environments, aromatic molecules preferentially adsorb onto the wall and aggregate into local clusters, thereby substantially hindering the overall molecular mobility and mass transport efficiency of the confined fluid.

Figure 6.

Radial number density distributions of solute molecules within CNTs of different diameters. (a) SCW–anthracene system. (b) SCW–propane system.

Further analysis of the aromatic density peak shows that the primary peak is consistently located at a distance of approximately 3.27–3.56 Å from the CNT inner wall. This distance agrees well with the typical π–π stacking interplanar spacing (3.3–3.4 Å) reported for aromatic ring–graphene systems[59], confirming that aromatic molecules preferentially adsorb onto the CNT inner surface in a parallel orientation. The primary adsorption mechanism is attributed to the non-covalent π–π interactions between the aromatic rings and the CNT surface.

Effect of solute molar concentration

-

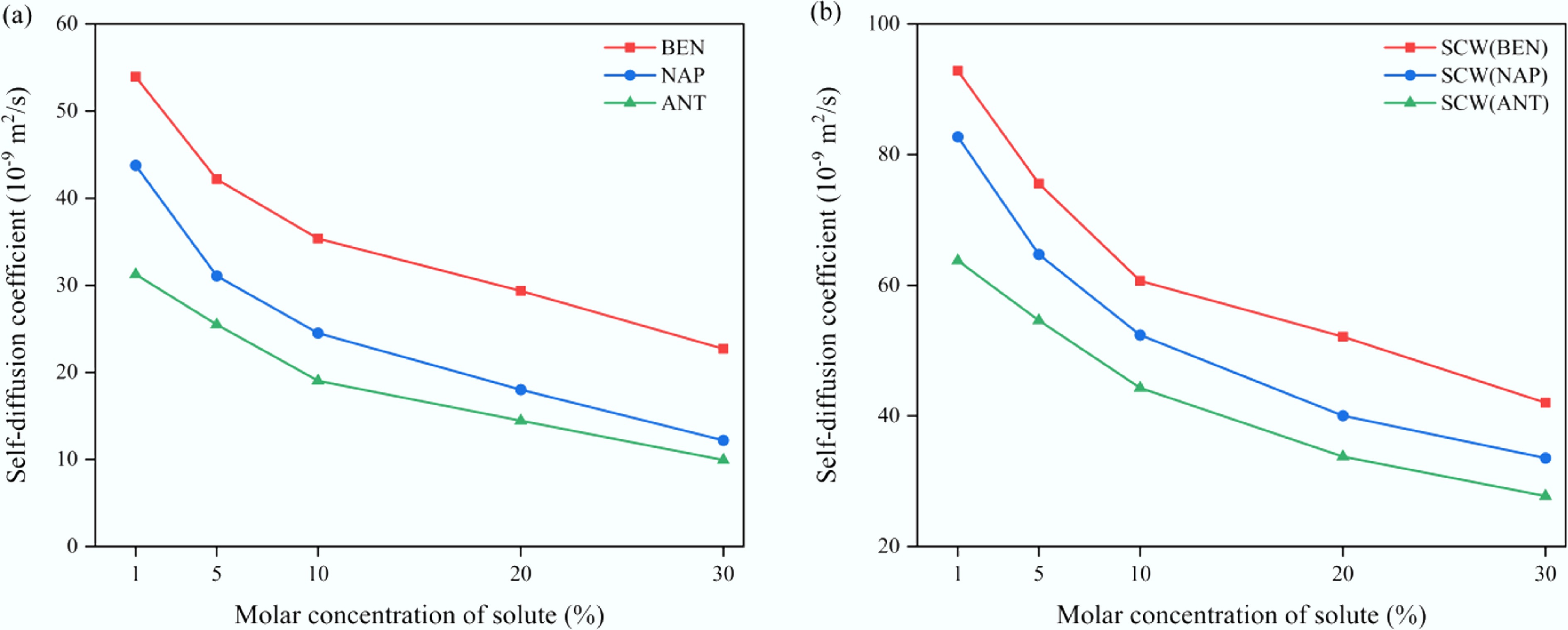

The preceding analysis indicates that solute molecules significantly affect the mass transport behavior of confined fluids, with aromatic hydrocarbons showing the most pronounced effects. To further investigate the role of solutes in regulating diffusion dynamics under confinement, SCW–aromatic hydrocarbon systems confined within CNT(15,15) were selected as representative models. Simulations were performed at 673 K with solute molar concentrations ranging from 1% to 30%. As shown in Fig. 7, both the solute (Fig. 7a) and SCW (Fig. 7b) show a marked decrease in self-diffusion coefficient with increasing solute concentration, indicating that the presence of solutes substantially suppresses overall molecular mobility. Furthermore, a comparison among different aromatic systems reveals a clear negative correlation between solute molecular size and diffusivity: as the number of aromatic rings increases, the overall mass transport capability of the confined system declines correspondingly.

Figure 7.

Variation of self-diffusion coefficients in confined SCW–aromatic hydrocarbon systems as a function of solute molar concentration. (a) Solutes. (b) SCW.

The observed differences in diffusion behavior can be explained by analyzing the underlying microscopic structural evolution. As shown in Fig. 8a, increasing solute concentration leads to a gradual substitution of water–water interaction sites by solute molecules, thereby disrupting the original hydrogen bonding network and causing a significant reduction in the overall hydrogen bond density of the system. This effect is particularly pronounced in multi-ring aromatics (e.g., anthracene) due to their stronger hydrophobicity and larger molecular volume, which impose greater perturbations on the hydrogen bond network. To further explore the energetic characteristics, the total potential energy of the system was partitioned into contributions from three components: SCW, solute, and CNT, according to their relative contributions. As shown in Fig. 8b, with increasing solute concentration, a distinct redistribution of energy contributions is observed. The SCW energy fraction decreases progressively, while that of the solute increases significantly, whereas the CNT contribution remains relatively constant. This redistribution indicates that the introduction of aromatic solutes fundamentally alters the internal energy landscape of the confined system. Moreover, this effect becomes stronger with increasing molecular size and aromatic ring number. Overall, the presence of high concentrations of aromatic solutes enhances local steric hindrance and structural disorder within the confined phase. Consequently, the overall mass transport and diffusion capacity of the SCW–solute mixtures is markedly reduced.

Figure 8.

Variation of (a) hydrogen bond density, and (b) energy distribution as a function of solute molar concentration in SCW–aromatic hydrocarbon systems confined within CNT(15,15) at 673 K.

Effect of temperature

-

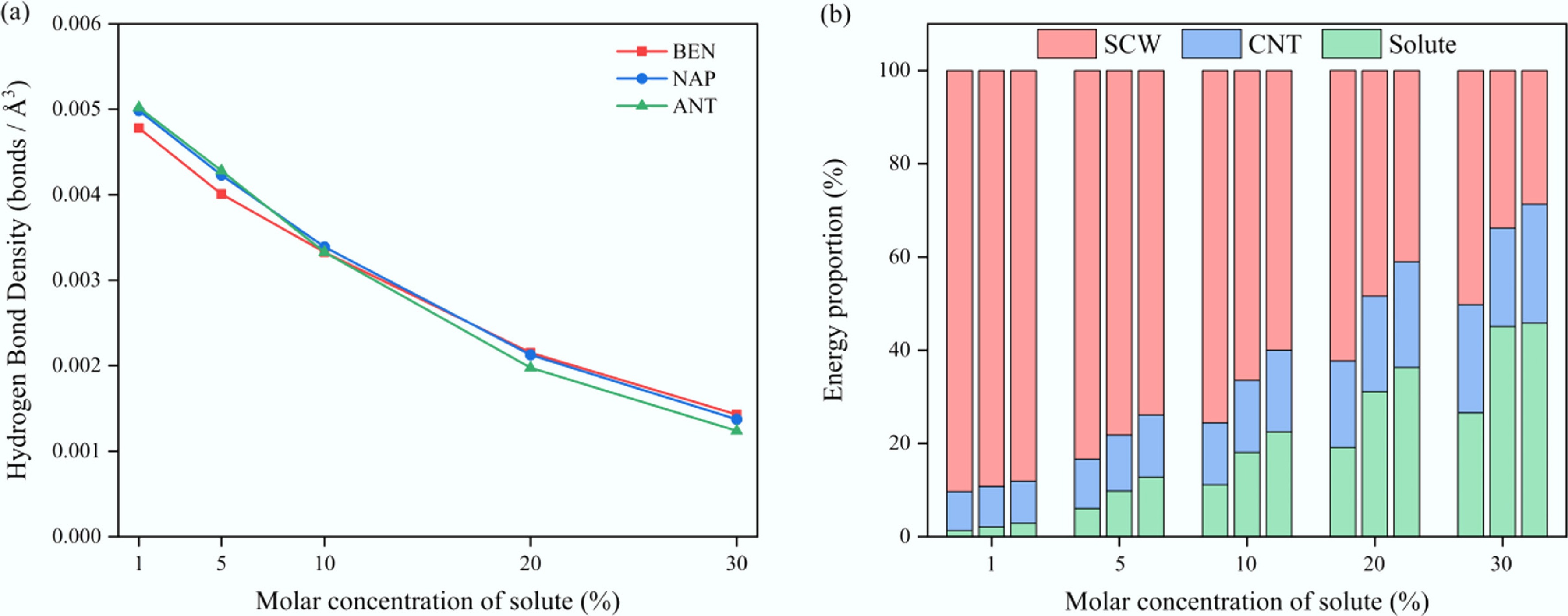

The preceding results indicate that the presence of aromatic solutes substantially reduces the molecular mobility of confined SCW systems, thus negatively affecting the efficiency of SCW-related processes, such as decreasing oil recovery or promoting undesired side reactions (e.g., coking). In practical SCWG operations, elevated temperatures are typically employed to enhance both reaction kinetics and mass transfer. To further investigate the effect of temperature on transport behavior under confinement, simulations were conducted for SCW–aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures confined within CNT(15,15) from 673 to 973 K with a fixed solute molar fraction of 10%. As illustrated in Fig. 9, the self-diffusion coefficients of both the solute (Fig. 9a) and SCW (Fig. 9b) increase significantly with rising temperature. This trend aligns with thermodynamic expectations, as higher temperatures provide more thermal energy to the molecules, enhancing molecular motion and diffusion[60]. Significant differences persist among the aromatic systems: SCW–benzene exhibits the highest diffusivity, followed by SCW–naphthalene, with SCW–anthracene exhibiting the lowest. Notably, the difference in diffusion coefficients among these systems persists within a relatively stable range of approximately 40%–50% across the entire temperature interval, indicating that the influence of solute molecular size on confined transport behavior remains robust and independent of temperature.

Figure 9.

Temperature dependence of the self-diffusion coefficients of (a) aromatic solutes, and (b) SCW in confined SCW–aromatic hydrocarbon systems.

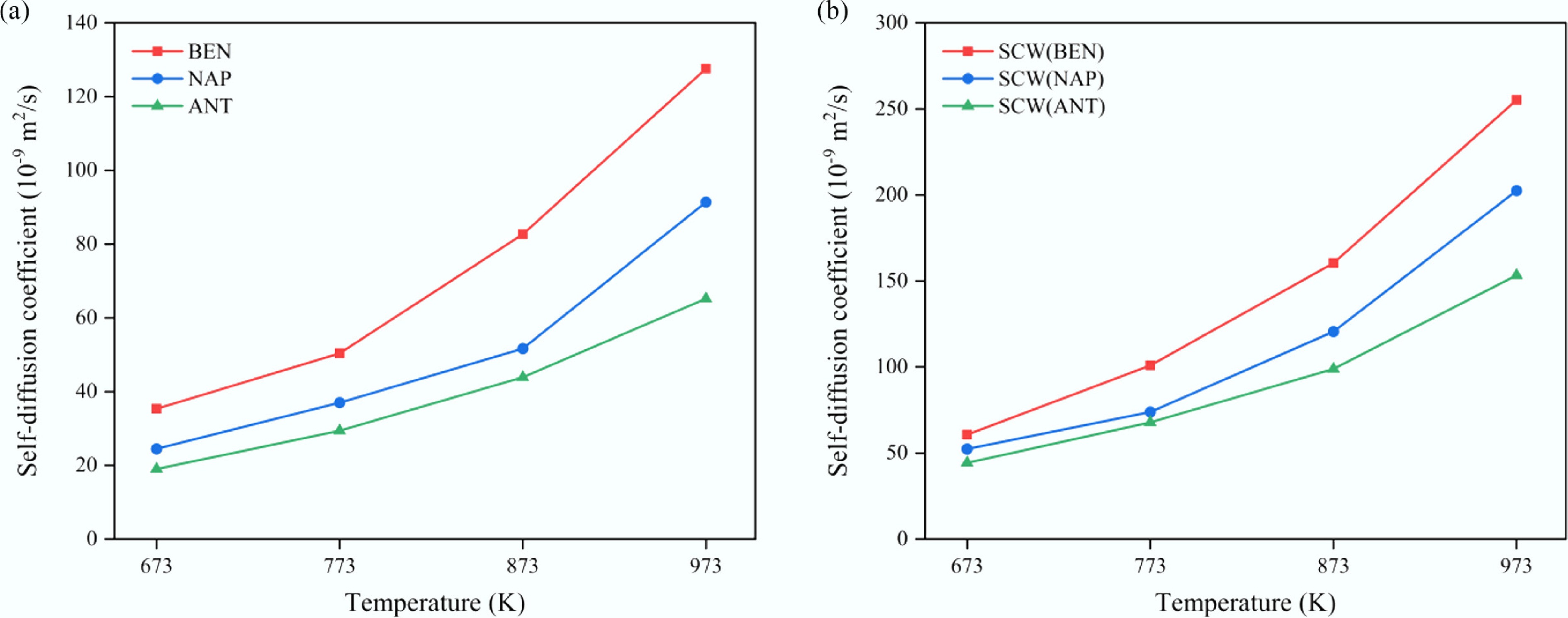

To remove the effect of density variations at different temperatures on the spatial distribution analysis, all systems were normalized to the same total density. Figure 10 illustrates the radial number density profiles of solutes in CNT(15,15) at various temperatures. The results show that, within the same system, the solute density peaks gradually broaden and decrease in intensity with increasing temperature, suggesting that solute molecules progressively desorb from the CNT wall and migrate toward the channel center. A comparison among the aromatic solutes further reveals that the extent of this temperature-induced desorption weakens as the number of aromatic rings increases, reflecting the stronger wall-binding affinity of larger aromatic molecules. To quantify the solute distribution behavior, the near-wall region was defined as the region with |r/R| > 0.7, and the fraction of solute density within this region was calculated. At 673 K, the near-wall fractions for benzene, naphthalene, and anthracene were 63.35%, 81.73%, and 90.78%, respectively. When the temperature increased to 973 K, these values decreased to 41.82%, 63.97%, and 74.32%, corresponding to an overall reduction of approximately 16%–22%. This trend clearly indicates that elevated temperatures facilitate the desorption and migration of organic molecules within nanoscale confinement. Such behavior is of great significance for enhancing mass transport efficiency in SCWG and other high-temperature supercritical processes.

-

In this study, MD simulations were employed to systematically investigate the structural evolution and dynamic behavior of binary SCW–organic molecules (alkane/aromatic hydrocarbon) confined within CNTs. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) Under nanoscale confinement, solute molecules strongly influence the overall diffusion of the system. Compared with alkanes, aromatic hydrocarbons significantly reduce the self-diffusion coefficients of both solutes and solvents, exhibiting a substantially stronger confinement-induced suppression effect.

(2) Owing to their cyclic π-conjugated structures, aromatic molecules experience strong π–π interactions with both the CNT wall and neighboring solute molecules, resulting in the formation of stable adsorption layers near the CNT walls. This adsorption and aggregation behavior suppresses the overall mass transport of the confined fluid and markedly affects the energy distribution and microscopic structure of the system.

(3) Increasing temperature effectively weakens the adsorption strength between aromatic solutes and the CNT wall, promoting their desorption from the confined surface and consequently enhancing the diffusivity of the confined fluid, providing molecular-level insight into how thermal activation enhances mass transfer efficiency in processes such as SCWG.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaoran Rong, Hongtu Wu, Hui Jin; data collection: Xiaoran Rong, Bowei Zhang, Jie Zhang, Tongjia Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiaoran Rong, Bowei Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Xiaoran Rong, Hongtu Wu, Hui Jin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2020YFA0714400), and Shaanxi Science & Technology Co-ordination & Innovation Project (Grant No. 2024GX-YBXM-518).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Molecular dynamics simulations reveal distinct transport behaviors of SCW–alkane and SCW–aromatic mixtures under CNT confinement.

Aromatic solutes markedly suppress the diffusion of both solute and SCW due to strong π–π interactions and near-wall aggregation.

The effects of confinement size, solute concentration, and temperature on adsorption layers, clustering behavior, and energy distributions were analyzed.

Elevated temperature weakens aromatic–CNT interactions, promoting desorption and enhancing mass transport in confined systems.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Rong X, Wu H, Zhang B, Zhang J, Zhang T, et al. 2026. Molecular dynamics study on the transport and structural behaviors of supercritical water–organic mixtures under nanoscale confinement. Sustainable Carbon Materials 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0015

Molecular dynamics study on the transport and structural behaviors of supercritical water–organic mixtures under nanoscale confinement

- Received: 03 November 2025

- Revised: 04 December 2025

- Accepted: 21 December 2025

- Published online: 15 January 2026

Abstract: Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to systematically investigate the transport behavior and microscopic structural characteristics of supercritical water–organic binary mixtures (alkane or aromatic) confined within carbon nanotubes. The results indicate that the molecular structure of the solute plays a crucial role in regulating the diffusion properties of the confined fluid. Compared with alkanes, aromatic solutes significantly reduce the diffusion coefficients of both solute and solvent components, and this inhibitory effect becomes more pronounced with increasing the number of aromatic rings. Energy and spatial distribution analyses reveal that, owing to the π-conjugated structure of aromatics, strong π–π interactions occur between aromatic rings and the carbon nanotube wall as well as among solute molecules, leading to preferential adsorption and cluster formation near the tube wall, which markedly restricts molecular mobility. Furthermore, increasing temperature effectively weakens the adsorption between aromatic molecules and carbon nanotube surfaces, thereby promoting the desorption and diffusion of organics from the confined region. This study elucidates, at the molecular level, the structural rearrangement and dynamic regulation mechanisms of SCW–organic systems under nanoscale confinement, providing theoretical insight for optimizing supercritical water gasification and related energy conversion processes.

-

Key words:

- Supercritical water /

- Molecular dynamics /

- Nanoscale confinement /

- Carbon nanotube /

- Diffusion behavior