-

Theories of reproductive evolution suggest that the divergence of sexual systems is a key mechanism for species' adaptive radiation. When a population contains two or more interbreeding sexual morphs, phenological asynchrony and morphological traits jointly drive the formation of nonrandom mating patterns[1]. In this process, disassortative mating is considered a key driving force in maintaining sexual polymorphism, with dichogamous plants being typical representatives of this mating pattern[1,2].

Dichogamy refers to the temporal separation of male and female reproductive functions within a plant, either within a single flower or among different flowers on the same plant[2,3]. This phenomenon is of significant importance in the field of plant reproductive biology and has attracted widespread attention. The concept was first described by Kölreuter (1761–1766) and formally named by Sprengel[4]. The term is derived from the Greek roots "dicho" (separation) and "gamous" (mating), emphasizing the temporal differentiation of male and female functions in hermaphroditic flowers[3,4]. However, the current academic consensus still follows Sprengel's original definition, which emphasizes the temporal offset of reproductive activities between stamens and pistils[4].

In spermatophyta, approximately 72% of species exhibit hermaphroditic flowering characteristics[5,6]. To avoid genetic defects caused by inbreeding depression (such as chromosomal deletions), these plants have evolved various mechanisms to promote cross-pollination, thereby maintaining genetic diversity and enhancing adaptability[7]. Key outcrossing strategies include self-incompatibility systems at the molecular level, morphologically differentiated heterostyly, and temporally regulated dichogamy[8−12]. It is worth noting that unisexual phenomena are not common in angiosperms, with only a minority of seed plant species exhibiting unisexual flowers (dioecy: approximately 4%; monoecy: approximately 7%), but their phylogenetic distribution is widespread, occurring in about 75% of families[13]. As a typical monoecious species, common walnut (Juglans regia) provides a case study of its reproductive system[14].

Although dichogamy is widespread in angiosperms[15], it has received relatively less attention compared with other floral traits[3]. This relative neglect may stem from Darwin's limited focus on the phenomenon, leading to long-standing deficiencies in theoretical and experimental research on the types, evolutionary drivers, and functional consequences of dichogamy. In recent years, as research on plant reproductive strategies has deepened, dichogamy, as an important reproductive mechanism, has gradually gained attention for its role in plant evolution and ecological adaptation.

-

Dichogamy effectively prevents self-pollination by avoiding a temporal overlap between pollen release and stigma receptivity[7]. This phenomenon manifests in various forms in plants, and a single species may exhibit a combination of two or more dichogamous subtypes, each of which, along with its combinations, may confer different benefits and drawbacks to the plant[2,16]. Depending on the order of maturation, dichogamy can be categorized into protandry (PA) and protogyny (PG)[17]. In hermaphroditic flowers, if the stamens mature significantly earlier than the stigma receptivity period, this is known as PA[18,19]; conversely, if the pistil is active before anther dehiscence, it is known as PG[18]. For instance, the hermaphroditic flowers of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and beet (Beta vulgaris L.) are pistil-first, while those of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and apple (Malus pumila Mill.) are stamen-first[3]. These two phenomena were previously termed 'androgyny' and 'gynandry', corresponding to PA and PG, respectively[3]. Hildebrand (1867) standardized them as PA and PG, while Delphino (1868–1875) further adjusted them to proterandry and proterogyny[4].

Depending on the scope of expression, dichogamy can be divided into intrafloral dichogamy and interfloral dichogamy[2]. Intrafloral dichogamy refers to the temporal separation of pistil and stamen maturation within the same flower. For example, Clerodendrum infortunatum exhibits stamen-first maturation[20], with a pronounced intrafloral dichogamy where the female and male phases are entirely separated in time. Interfloral dichogamy, on the other hand, refers to differences in the maturation times of pistils and stamens in different flowers on the same plant. For example, in maize (Zea mays), the male inflorescence matures earlier than the female inflorescence, exhibiting interfloral PA[21].

Depending on the degree of separation, dichogamy can be further divided into complete dichogamy and incomplete dichogamy[2,22]. Complete dichogamy refers to the absence of any temporal overlap between male and female functions, as seen in Platycodon grandiflorus[4,23]. Incomplete dichogamy, however, involves a brief period of overlap. For example, in H. annuus L.[2], there is a partial overlap between the pollen and stigma receptivity periods of stamen-first and pistil-first forms.

Additionally, depending on the synchrony of male and female maturation within a plant, dichogamy can be classified as synchronous or asynchronous dichogamy[2]. Synchronous dichogamy refers to the highly consistent maturation times of pistils and stamens across all flowers on a plant, as seen in Ziziphus mauritiana[24] and Sassafras randaiense[25]. Asynchronous dichogamy (also known as heterodichogamy), in contrast, involves significant differences in the maturation times of pistils and stamens in different flowers on the same plant, such as in Acer pseudoplatanus[24], J. regia[14], Carya illinoinensis[26], and other members of the Juglandaceae family. In asynchronous dichogamous plants, the pistils and stamens of female and male flowers mature synchronously within their respective sexes but do not interfere with each other. This characteristic enables the plant to effectively engage in disassortative hybridization, thereby promoting genetic diversity[27−29].

This study compiles the systematic classification and reproductive characteristics of 50 dichogamous plant species across 27 families (Table 1), revealing the diversity and adaptive differentiation of this phenomenon in the plant kingdom. The statistical data clearly show that dichogamy is particularly prominent in the Lauraceae family, the genus Acer, and the Annonaceae family. Notably, plants in the Lauraceae family predominantly exhibit PG with a 6–12-h interval, which is strongly associated with self-incompatibility (SIC), reflecting an adaptive strategy to promote outcrossing through temporal separation. Moreover, according to this table, it can be inferred that the dichogamous strategy of plants can effectively avoid inbreeding depression through spatiotemporal separation. For example, the widespread PG in Lauraceae plants such as Cinnamomum and Aniba, in conjunction with insect pollination, not only enhances the resilience of tropical forest tree species to disturbances but also maintains and increases genetic diversity at the community level through outcrossing.

Table 1. Attributes of currently known dichogamous flowering plants.

Family Genus Species Flowering characteristics Ref. Pollinating vector Male–Female

separationCompatibility Sapindaceae Acer Acer pseudoplatanus Thysanoptera 24−48 h SC [30] Acer japonicum Insects [31] Acer grandidentatum [32] Acer saccharum [33] Acer opalus [10] Acer mono [9] Circaeasteraceae Kingdonia Kingdonia uniflora Unknown 1 d Unknown [34] Amaranthaceae Grayia Grayia brandegei Wind 14−21 d SIC [8] Spinacia Spinacia oleraacea var. americanna Wind 24−48 h SC [8] Lauraceae Aniba Aniba rosaeodora Apis 6–12 h SIC [35] Cinnamonum Cinnamonum camphora Apis 6–12 h SIC [35] Cinnamonum zeylanicum [35] Licaria Lcaria guianensis Apis 6–12 h SIC [35] Mezilaurus Mezilaurus thoroflora Apis 6–12 h SIC [35] Persea Persea americana Apis 24 h SIC [35] Persea caerulea [35] Thymelaeaceae Thymelaea Thymelaea hirsuta Wind 8−12 d Unknown [29] Trochodendraceae Trochodendron Trochodendron aralioides Musca domestica 10−28 d SC [36] Annonaceae Annona Annona squamosa Coleoptera 12 h SC [36] Betulaceae Corylus Corylus avellana Wind A few days varies SIC [27] Lamiaceae Lepechinia Lepechinia floribunda Bombus and Xylocopa aeratus 6 h SC [37] Juglandaceae Carya Carya illinoensis Koch Wind 1−2 d SC [26] Carya ovata [38,39] Carya tomentosa [38,39] Carya laciniosa [38,39] Juglans Juglans hindsii Wind 7 d SC [40] Juglans nigra [27] Juglans mandshurica [41] Juglans ailanthifolia [42] Juglans regia [43] Juglans cinerea [38] Juglans cordiformis [36] Cyclocarya Cyclocarya paliurus Wind 14 d SC [38,39] Lauraceae Sassafras Sassafras randaiense Rehd Beetles and Apis 1−2 h SIC [25] Campanulaceae Platycodon Platycodon grandiflorus Unknown Unknown SIC [4,23] Rhamnaceae Ziziphus Ziziphus mauritiana Wasps, flies, butterflies and bees 3−12 h SIC [24] Araliaceae Stilbocarpa Stilbocarpa polaris Drosophilidae 10 d SC [44] Meliaceae Toona Toona sinensis Unknown 17−24 d Unknown [45] Lamiaceae Ajuga Ajuga decumbens Apis and Megachile 1−2 d SC [46] Salvia Salvia elegans Trochilidae 1−2 d SC [47] Verbenaceae Clerodendrum Clerodendrum infortunatum Papilionoidea 11 h SC [20] Onagraceae Clarkia Clarkia pulchella Pursh Halictidae 1−2 d SC [48] Alismataceae Sagittaria Sagittaria latifolia Apis, wasps, and beetles 1 d SC [49] Asteraceae Helianthus Helianthus annuus Apis 3−7 d SC [2] Amaryllidaceae Narcissus Narcissus broussonetii Long-tongued pollinators 3 d SIC [50] Brassicaceae Brassica Brassica napus Apis and wind 1−3 d SIC [51] Amaranthaceae Beta Beta vulgaris Wind 1−2 d SIC [52] Rosaceae Malus Malus domestica Apis and wind Unknown SIC [53] Poaceae Zea Zea mays Wind 2−7 d SC [54] Cucurbitaceae Cucumis Cucumis sativus Unknown Unknown Unknown [55] Zingiberaceae Lanxangia Lanxangia tsaoko Unknown 2−4 h SIC [56] Note: SC represents self-compatibility and SIC represents self-incompatibility. -

The phenomenon of dichogamy may be associated with multiple factors, including biological interactions[3], environmental responses[57], gene expression[58], and epigenetics[59]. Under similar environmental conditions, dichogamous plants exhibit temporal rather than morphological differences during flower development, suggesting that genes regulating flowering time may play a more crucial role and deserve further attention. Moreover, once floral sexual differentiation is completed in dichogamous plants, the asynchrony in flowering time becomes evident through the distinct differences in the opening sequence of male and female inflorescences or individual flowers[60]. This indicates that the process of sex differentiation may influence flowering time at the population or individual level by altering the sex ratio of plants and the sequence of floral development[60]. Although direct evidence linking sex differentiation and flowering time in dichogamous plants is limited, studies on te regulation of sex expression in dioecious species and the temporal and spatial regulation of flower sex differentiation in dichogamous species can provide a theoretical framework for this field[60]. However, research on genes regulating flowering time and sex differentiation in dichogamous plants remains limited. Nonetheless, relevant studies in other plants, such as the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, can offer insights into the factors affecting the mechanisms in dichogamous plants.

Biological factors

Pollinators

-

Throughout plant growth, diverse biological activities are present. As a key facilitator of outcrossing, pollinators shape plants' selection pressure for dichogamy through species-specific traits, visitation frequency, and variation in feeding behavior[3]. In Narcissus broussonetii, long-styled plants delay stigma receptivity, while short-styled ones elevate their styles to prevent self-pollination, illustrating pollinator-driven dichogamous coevolution[51]. In Primula oreodoxa, at higher altitudes, reduced long-tongued pollinator activity may favor homostyly over heterostyly, increasing self-pollination rates[61].

Pathogens

-

Intraspecific resource competition drives plants to optimize energy allocation, while pathogen infection risks can disrupt the balance of sexual expression; together, they affect the dynamic balance of dichogamy. In Cucumis sativus, upregulating the flavonoid metabolism combats powdery mildew, and jasmonic acid (JA) signaling induces the MYB21 gene to promote stamen development[62]. These hormonal networks influence flowering time and sexual differentiation. For example, the disease-resistant variety BK2, regulated primarily by salicylic acid (SA) and auxin, shows a moderate proportion of female flowers and delayed flowering, whereas the susceptible variety H136, controlled mainly by gibberellin (GA) and JA, has a higher proportion of female flowers, earlier flowering, and premature senescence. This illustrates that plants can regulate dichogamy while resisting pathogens[62]. Additionally, Magnaporthe oryzae infecting Oryza sativa damages photosynthetic organs like leaves, impairing photosynthesis and affecting carbohydrate accumulation and metabolism, which may delay flowering or shorten the flowering period, ultimately reducing grain set and yield[63]. In summary, pollinators' behavior and pathogen infection interact with other biological factors to influence plants' flowering and reproduction strategies, reflecting complex coevolutionary relationships in ecosystems.

Abiotic factors

Environmental factors

-

Plant growth and development are influenced by a combination of internal and external environmental factors, among which light, nutrition, temperature, and water play a crucial role in the flowering cycle[64−66]. In Cyclocarya paliurus, while soluble proteins for protandrous male bud development mainly come from their own reserves, those for female bud development rely on the photosynthetic products of the surrounding leaves, and insufficient light may weaken nutrient acquisition in female flowers, which may disrupt the dichogamous sequence[64]. In C. illinoinensis, spring freezes in April can severely injure pecan buds, decreasing bloom and fruit set; however, the results demonstrate that the Maramec/Colby combination uses more nonstructural carbohydrates and soluble sugars and starches, which may be a possible mechanism contributing to its freeze tolerance, which may be a possible mechanism contributing to its freezing tolerance[65]. In A. thaliana, the abscisic acid (ABA)-responsive element-binding factors 3 and 4 act with the nuclear factor Y subunit C to promote flowering by inducing the transcription of SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS1 (SOC1) under drought conditions, which might contribute to adaptation by enabling plants to complete their life cycles under drought stress[66].

Regulatory network of flowering sequence and sex differentiation

Regulation of flowering time

-

Flowering is a crucial stage in the life cycle of plants, precisely regulated by the interaction of external environmental signals, such as photoperiod and temperature, and internal molecular networks. These internal networks include hormone signaling, circadian rhythms, and genes associated with flowering. This process not only shapes the reproductive strategies of species but also reflects the adaptive evolution of plants to dynamic niches[67]. Although model plants like A. thaliana and O. sativa have revealed the molecular mechanisms of floral transition through core modules such as CONSTANS, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), FLOWERING LOCUS M, FRUITFULL, TERMINAL FLOWER1, and AGA MOUS-LIKE 24[68], there are still significant research gaps in the regulation of flowering in dichogamous plants. Currently, the identification of related gene functions and pathway analysis are limited to scattered reports on a few species.

The regulation of flowering time in maize involves a complex molecular network, where ZmGIGANTEA2 (ZmGI2) acts as a core regulator influencing the photoperiod-dependent flowering process through the combined action of multiple pathways[69]. Research has shown that mutations in the ZmGI2 gene lead to early flowering under long-day conditions but do not significantly affect flowering time under short-day conditions[69]. ZmGI2 directly binds to the promoter regions of FT-like gene CENTRORADIALIS8 (ZmZCN8) and Flowering-promoting Factor 1 (ZmFPF1), thereby inhibiting their expression. ZmZCN8, translated in the leaf vasculature, relocates to the shoot apex to trigger floral identity genes; ZmFPF1 then accelerates flowering[69]. Further studies have indicated that ZmGI2 regulates flowering through its downstream targets A Response Regulators (ZmARR11), DNA binding with one finger (ZmDOF), and Ubiquitin-conjugating 11 (ZmUBC11)[69,70].

In addition to the above, there is an interesting trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P) synthesis pathway in the flowering regulatory network of many plants, such as A. thaliana. T6P acts as a signaling molecule and a regulator of sucrose homeostasis. It regulates sucrose production in the source leaves and developmental processes via trehalose phosphate synthase (TPS) and trehalose phosphate phosphatase (TPP), thereby modulating flowering and embryo development[68]. Recent studies show that the TPPD gene in walnuts is key to regulating flowering time. Its 3' untranslated region (UTR) contains tandem repeats that affect gene expression through small RNA mechanisms, controlling the maturation sequence of male and female flowers. This finding reveals the molecular basis of walnut's flowering dichogamy and offers new insights into the regulation of plant flowering[71]. In apple, flowering control largely mirrors the Arabidopsis paradigm. Exogenous sucrose selectively upregulates 5 of the 13 TPS genes (MdTPS1–MdTPS13), increasing T6P, which, in turn, activates SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) and other flowering integrators. Sucrose simultaneously elevates leaf FT1 and floral APETALA1 (AP1) transcripts, supporting a model in which FT protein acts as a mobile inductive signal[72]. Concomitantly, sucrose represses miR156 and induces miR172, thereby releasing SPL from age-dependent inhibition. The sucrose-metabolizing enzymes sucrose synthase1, sucrose-phosphate synthase6, and hexokinase1 also contribute to this regulatory network[72]. In addition, Chen et al. traced the first dichogamy switch in Zingiberaceae to a 13-kb locus in the dichogamy-associated region (DAR) on chromosome 12 of Lanxangia tsaoko, which determines whether plants are PA or PG. Within DAR, influence anther dehiscence (LtIAD) is upregulated in PG anthers; its overexpression in rice delays dehiscence and recreates the PG phenotype[56].

Some hormones can indirectly influence the flowering of plants through relevant signaling pathways. In C. paliurus, most CpC5-Methyltransferase (CpC5-MTase) and Cpd Methyltransferase (CpdMTase) genes are significantly correlated with key enzymes in the GA biosynthesis pathway, such as DELLA and GIBBERELLIN DWARF1. Moreover, GA-responsive elements have been identified in the promoter regions of these genes[73]. This suggests that GA may modulate the promoter activity of CpC5-MTase and CpdMTase genes to affect DNA methylation levels, ultimately influencing the flowering process and cross-pollination characteristics of Camellia papyrifera[74]. Malus domestica trees exhibit alternate bearing during their growth and development, with years of low yield (OFF years) and high yield (ON years)[75]. Research has shown that M. domestica trees in OFF years promote floral induction by activating the phenolic acid metabolism pathway[75]. Notably, although ABA and GA do not show significant differences, cytokinins may indirectly regulate SA synthesis through the histidine–aspartate phosphorelay signaling pathway, thereby influencing flowering[76]. However, the reduction in SA derivatives is consistent with the carbohydrate competition hypothesis, which posits that fruit development consumes excessive resources, thereby limiting the accumulation of flowering-related signals[77]. Furthermore, the dynamic balance between methyl jasmonate and indole-3-acetic acid may be disrupted under high-load conditions, further inhibiting floral bud differentiation[75].

Sex determination

-

Flower development is fundamental for fruit and seed production in plants. Compared with hermaphroditic flowers, the differential development or selective arrest of carpels or stamens in some species leads to unisexual male or female flowers, creating flower sex-type diversity[78]. Various combinations or distributions of the three flower types result in dichogamous, dioecious, and hermaphroditic plants, forming the sexual morphological diversity of plants[77]. In the sex differentiation regulatory network of dichogamous plants, the ethylene biosynthesis and signaling pathway, the cell cycle regulatory pathway, and members of transcription factor families together form the core regulatory module[79]. In C. sativus, sex determination is regulated by 1-aminocyclopropane-l-carboxylate (ACC) synthase encoded by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase (CsACS1G) and CsACS2. CsACS1G induces female flower development by catalyzing the synthesis of the ethylene precursor ACC[79], while CsACS2 maintains the hermaphroditic flower phenotype by suppressing stamen development[80]. Studies have shown that ETHYLENE RESPONSE 1 (CsETR1), an ethylene receptor, inhibits stamen development in female flower primordia by inducing a DNA damage response mechanism[81]. Notably, this study found that CsACS1G is specifically and highly expressed at the one-leaf–one-heart stage in C. sativus (B36), potentially suppressing the expression of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Oxidase (CsACO1/3) through negative feedback regulation, thereby forming a time-specific window for ethylene signaling[73]. Additionally, key cell-cycle genes − including Minichromosome Maintenance complex components (Cs-MCM2, Cs-MCM6), Cell Division Cycle 45 (CDC45), DNA primase (Cs-Dpri), and Cs-CDC20 − exhibit peak activity in dichogamous plants during the one-leaf–one-heart stage, synchronized with activation of the ethylene pathway[82]. This implicates ethylene in cell cycle coordination, where Cs-MCM6 governs DNA replication in early floral tissues, whereas Cs-CDC20 may initiate the meiosis transition[82]. Co-upregulated ethylene response factors (Cs-ERF12, Cs-ERF118) potentially integrate ethylene signaling with sex determination[82].

Epigenetic modification

DNA methylation

-

DNA methylation, as an important epigenetic regulatory mechanism, can influence flowering time and sex differentiation in plants by modulating downstream gene expression. However, there are currently few studies on the impact of DNA methylation on the flowering process in dichogamous plants, with only a limited number of examples in C. paliurus[73]. Research has shown that in C. paliurus, cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase (C5-MTase) and DNA demethylase (dMTase) affect the flowering process by regulating gene expression[73]. During the polyploidization of the CpC5-MTase and CpdMTase gene families, significant gene expansion and loss events have occurred. Specifically, the DEMETER subfamily has significantly expanded during tetraploidization, while the CHLOROPLAST MANGANESE TRANSPORTER 1 and DEMETER-like subfamilies have experienced gene loss[73]. These dynamic changes in gene families have led to alterations in DNA methylation patterns, which, in turn, affect the synchronous development of floral organs. Moreover, CpC5-MTase and CpdMTase expression differs between female and male flowers and between the mating types PA and PG across stages[75]. At bud break (S2), specific CpC5-MTase transcripts peak in PG males, while certain CpdMTase transcripts rise in PA males, driving asynchronous flowering. Concomitantly, DNA methyltransferase 2 and methyltransferase are downregulated in PG pistillate buds, lowering methylation and accelerating female development; conversely, upregulation of repressor of silence 1 demethylase in PA staminate buds promotes male growth via active demethylation[75]. By maturity, CpC5-MTase and CpdMTase are predominantly higher in female flowers, with further mating-type variation, underscoring DNA methylation's sex-biased control of floral morphogenesis and sex differentiation in C. paliurus.

Noncoding RNA regulation

-

Noncoding RNAs, which are molecules that do not encode proteins but are widely involved in the regulation of gene expression, mainly include microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)[82]. However, in the study of dichogamous plants, research on this topic is very limited. Only a few studies have found that some genes in miRNA families can regulate the flowering time and sex differentiation of dichogamous plants by targeting downstream genes[83−85]. Research has shown that ZmSPL13 and ZmSPL29 are key factors regulating the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth in Z. mays[83]. These two genes belong to the SPL family, and their expression is regulated by the microRNA miR156. As Z. mays plants develop, the expression of miR156 gradually decreases, leading to an increase in the accumulation of ZmSPL13 and ZmSPL29[85]. ZmSPL13 and ZmSPL29 directly activate the expression of ZmMIR172C, thereby inhibiting its target gene Glossy 15 (which encodes an AP2 transcription factor), thus promoting the transition from the vegetative stage to the adult stage[83].

Additionally, in Z. mays, it has been found that the sex determination of the male inflorescence (tassel) is closely related to the microRNA miR172 family member Tasselseed4 (Ts4)[84]. Research has shown that Ts4 targets the AP2-like transcription factor indeterminate spikelet1 (IDS1) to inhibit pistil development and maintain male flower characteristics[84]. Specifically, in wild-type Z. mays male flowers, the miR172 encoded by Ts4 cleaves IDS1 mRNA, preventing its translation into protein and thereby inhibiting the formation of pistil primordia. When the function of Ts4 is lost (such as in Ts4 mutants), the IDS1 protein accumulates excessively, causing male flowers to transform into bisexual flowers (containing pistil structures)[84]. It is worth noting that another mutant, Ts6, exhibits a dominant pistil development phenotype, and its mechanism is different from that of Ts4: The IDS1 protein encoded by the Ts6 gene escapes degradation due to a mutation in the miR172 binding site, resulting in a gain-of-function effect[84].

In studies of other nondichogamous plants, it has been observed that noncoding RNA systems form complex regulatory networks through cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting factors, indirectly controlling the flowering process[70,85]. In A. thaliana, the YTH-domain N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader EVOLUTIONARILY CONSERVED C-TERMINAL REGION2 (ECT2) binds to m6A-modified transcripts of the trichome regulator TESTA GLABRA 1 and stabilizes them; loss of ECT2 disrupts trichome morphogenesis, which, in turn, alters light perception in the leavees and flowering time[85]. Moreover, the two major miRNA modules, miR156-SPL and miR172-AP2, precisely regulate the temporal transition from vegetative to reproductive growth through mutual antagonism, and this mechanism is highly evolutionarily conserved[86]. Additionally, the lncRNA COOLAIR suppresses the expression of FLC through chromatin remodeling, forming the core epigenetic barrier of the vernalization pathway[87].

Histone modification and chromatin remodeling

-

Histone modification refers to the process by which histones undergo modifications such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination under the action of related enzymes[88]. These modifications can influence gene expression by altering the state of chromatin, in turn affecting the flowering process in plants[88]. Similarly, research on this topic in dichogamous plants is very limited. Only in cucumber has it been found that the histone acetyltransferase (HATs) and histone deacetylase (HDACs) gene families exhibit significant stage-specific expression patterns during flower bud development[89]. For example, whole-genome analysis has revealed that among the 36 CsHAT genes and 12 CsHDAC genes in cucumber, their expression levels dynamically change during the growth stages of flower buds from 1–2 to 9 mm, implying that these enzymes may participate in determining flowering time by regulating the chromatin accessibility of target genes[89]. Notably, the expression of CsHAT genes is significantly higher at the initial stage of flower bud formation (e.g., 1–2 mm) compared with the apical bud stage, whereas CsHDAC genes show higher activity in later developmental stages (e.g., 6–8 mm). This suggests that the coordinated action of HAT/HDAC may drive the initiation and termination of flower organ differentiation[89].

In studies of other nondichogamous plants, it has been observed that the methylation of histone H3 exhibits spatiotemporal distribution characteristics: H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 promote reproductive growth by activating the expression of the key flowering gene FT[90] and the floral organ development regulator AP3[91], respectively. In contrast, H3K27me3 is catalyzed by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) complex and deposited at the FLC locus, maintaining the vernalization-induced flowering repression state through epigenetic silencing[88]. Acetylation neutralizes the positive charge of lysine residues, altering chromatin's accessibility. The dynamic changes in H3K9ac and H4K16ac are involved in photoperiod signal-mediated flowering regulation[92]. The histone demethylase JMJ16 represses the expression of leaf senescence genes by erasing the H3K4me3 mark on the WRKY53 promoter[93]. In contrast, demethylation of H3K9me3 mediated by JMJ30 promotes callus formation[94].

Chromatin remodeling and the three-dimensional structure of chromatin

-

Chromatin remodeling exerts spatiotemporally specific functions in determining the identity of floral organs in plants by dynamically regulating the higher-order structure of chromatin and its interaction network with transcription factors, and subsequently controls genes related to flowering[95]. Current research is mostly focused on the model plant A. thaliana, and there are significant gaps in studies on dichogamous plants. Nevertheless, insights can still be gained by starting with research on A. thaliana. The chromatin remodeling ATPases SPLAYED (SYD) and BRAHMA, members of the SWI2/SNF2 family, physically interact with the floral organ identity determinants LEAFY (LFY) and SEPALLATA3 (SEP3)[95]. During flower development in A. thaliana, they antagonize Polycomb-mediated epigenetic repression, dynamically regulating the spatiotemporally specific expression of the AP3 and AGAMOUS genes[95]. Notably, SYD can directly bind to the N-terminal protein interaction domain of LFY, whereas SEP3 enhances the recruitment efficiency of SYD through its DNA-binding domain, forming a synergistic regulatory module combining transcription factors and chromatin remodeling factors[95].

Recent studies have shown that the three-dimensional (3D) chromatin interaction patterns at flowering-related loci undergo significant reorganization during the transition to flowering. Using Hi-C technology, it has been found that in A. thaliana, flowering loci form chromatin loop structures under floral induction conditions, promoting physical contact between enhancers and promoters, thereby activating the expression of downstream flowering genes[96]. In O. sativa, dynamic changes in the 3D genomic topology are positively correlated with the level of m6A modification, suggesting that epigenetic modifications may regulate the coordinated expression of flowering genes by affecting the spatial conformation of chromatin[97].

-

Dichogamy, a floral trait widely present in hermaphroditic plants, primarily functions to temporally separate male and female reproductive functions. This separation forms complex adaptive trade-offs in avoiding inbreeding depression, optimizing resource allocation, and enhancing genetic diversity[3,18,51,98].

From the perspective of avoiding self-pollination risks, dichogamy reduces the probability of pollen (male) and stigma (female) interacting within the same plant through spatiotemporal separation, effectively inhibiting self-pollination. For example, PA, which releases pollen first and suppresses stigma receptivity during the same period, significantly reduces the occurrence of geitonogamy[99]. PG, on the other hand, delays stigma maturation to avoid self-pollination[3]. This mechanism is particularly important in self-incompatible plants, as it prevents the plant's own pollen from occupying stigma space and thus discounting ovules[99]. However, the temporal separation of dichogamy may lead to temporal mismatches between male and female functions: if pollen release peaks before stigma receptivity, it may result in pollen wastage; conversely, if stigma receptivity is prolonged, it may increase competition for outcrossing pollen[15]. This trade-off is especially prominent in entomophilous plants, as pollinators' behavior directly affects the efficiency of sexual resource allocation[51].

In terms of enhancing population genetic diversity, dichogamy can promote outcrossing to break the inbreeding bottleneck and increase heterozygosity. Heterosis, which enhances the offspring's fitness through the expression of beneficial recessive genes and hybrid vigor, is supported by the spatiotemporal separation mechanism of dichogamy[98]. For example, synchronous PA maximizes the overlap of flowering periods among different plants, thereby enhancing interplant pollen flow[18]. However, over-reliance on outcrossing may lead to the accumulation of genetic load, especially when inbreeding coefficients increase in small populations, and heterozygote disadvantage may offset the benefits of heterosis[18]. Moreover, strict temporal separation in dichogamy may limit the range of gene flow. If pollination networks are unstable, this can reduce allelic diversity within populations[100].

From the perspective of sexual selection and resource allocation, dichogamy optimizes energy allocation through phased functional differentiation. Protandrous plants focus resources on anther development during the pollen maturation stage and shift to ovule maintenance during the female phase. This phased specialization can improve resource use efficiency[51]. For example, wind-pollinated dichogamous plants often shorten the stigma receptivity period to reduce energy loss from wind pollination[51]. However, this resource allocation pattern may limit reproductive flexibility: In the absence of pollinators, a premature decline in male function can lead to insufficient pollen export, while an extended female phase may increase the risk of ovule abortion[101]. It is worth noting that the evolution of dichogamy is often accompanied by pollinator-mediated selective pressures. For example, in plants of the genus Ruellia pollinated by hummingbirds, the movement of touch-sensitive stigma coordinates the timing of male and female functions, reducing the probability of self-pollination probability while matching the flowering rhythm of pollinators[100].

Overall, the adaptive significance of dichogamy is reflected in a dynamic balance amid multiple trade-offs, specifically manifested as follows:

(i) Dichogamy reduces the risk of self-pollination through temporal separation mechanisms but incurs the cost of potential sexual resource mismatches.

(ii) Dichogamy enhances genetic diversity by promoting outcrossing but may face the trade-off of restricted gene flow.

(iii) Dichogamy optimizes resource allocation through functional differentiation but still needs to cope with the challenges of environmental fluctuations.

These balances shape the diverse manifestations of dichogamy across different ecological contexts and make it an important driving force in the evolution of plants' reproductive strategies.

-

Dichogamy, as a crucial reproductive strategy, plays a pivotal role not only in plants' evolution and ecological adaptation but also demonstrates significant application potential in the field of hybrid breeding. Its temporal separation mechanism of male and female reproductive functions effectively reduces the rate of self-fertilization, providing a natural biological emasculation solution for the production of hybrid seed. This substantially reduces the labor costs associated with manual emasculation and enhances the efficiency of outcrossing[15,36,102]. For instance, timely and thorough manual detasseling during the production of hybrid maize seed effectively curtails self-pollination, secures heterosis, and minimizes seed contamination[102]. Similarly, heterodichogamous plants, such as walnut (J. regia), promote natural outcrossing through reciprocal flowering asynchrony (PA vs. PG) between different individuals. Optimized orchard configurations can significantly enhance the efficiency of cross-pollination[42,71,103]. A recent study found that structural variants control heterodichogamy, possibly by influencing the expression of TPPD-1[71]. Concurrently, the cucumber CsACS1G gene potentially regulates pistillate flower development through the ethylene biosynthesis pathway[104,105]. These key genes offer new clues for understanding the molecular basis of dichogamy and can serve as valuable genetic resources for marker-assisted breeding. However, using dichogamy in breeding still has limitations. Changes in environmental conditions (such as temperature shifts) may affect flowers' synchronization, and the strict timing of flowering could reduce reproductive success[65]. Future research should integrate genomics and gene editing technologies to optimize dichogamous phenotypes, balancing outcrossing efficiency with stress resilience, thereby advancing the development of high-yield, genetically diverse hybrid crops.

-

Dichogamy, as a key reproductive strategy in angiosperms, achieves a complex dynamic balance by skillfully separating the maturation times of male and female reproductive organs. This separation effectively avoids the risks of self-pollination, optimizes resource allocation, and enhances genetic diversity. Dichogamy has played a crucial role in the evolutionary history of plants and has demonstrated remarkable adaptability across diverse ecological contexts, highlighting the capacity of plants to respond to environmental changes and the complexity and flexibility of their reproductive strategy evolution.

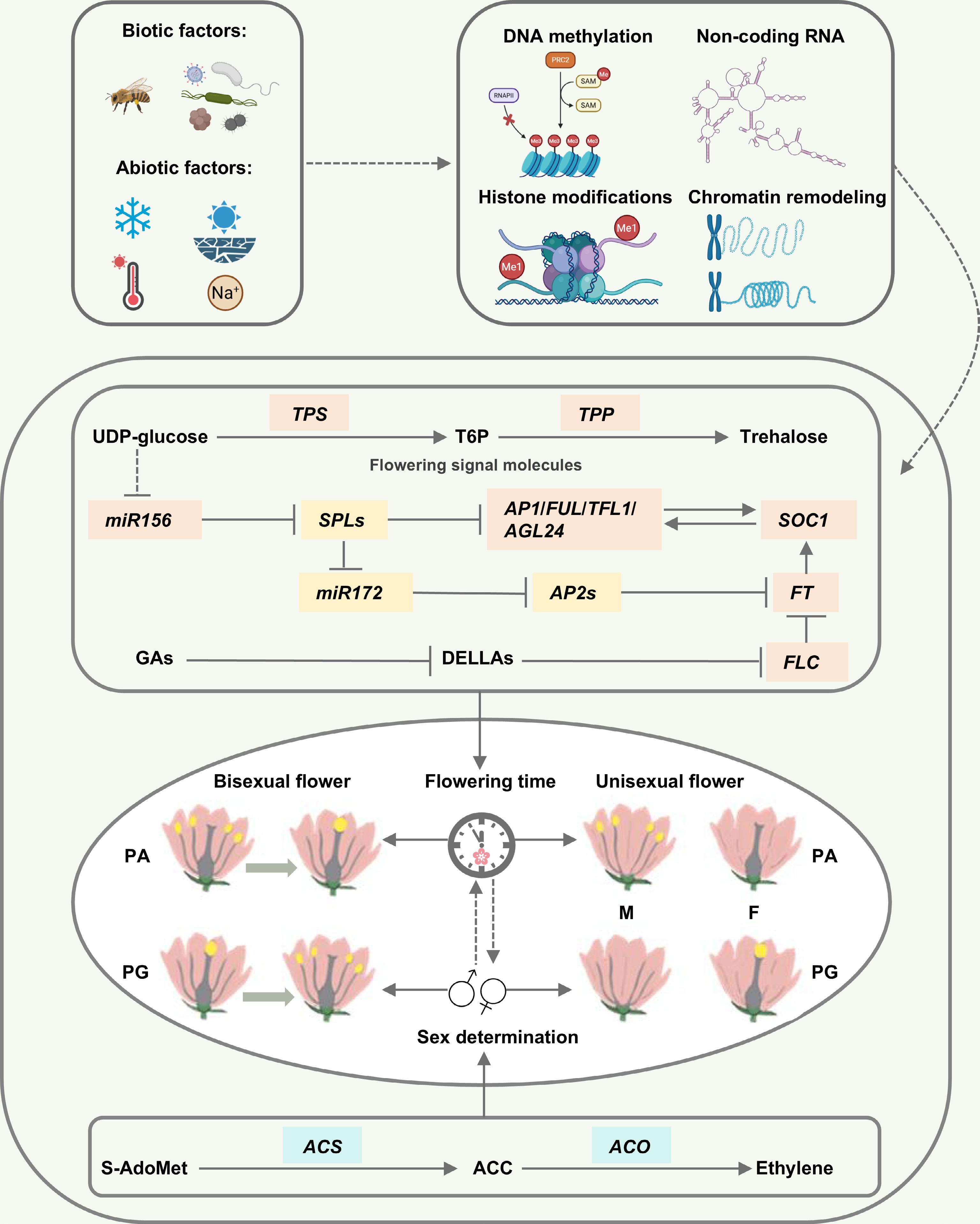

Despite its significance, research on dichogamy remains relatively limited. This review, based on a comprehensive examination of previous studies, summarizes the characteristics of dichogamy in various plants and elaborates on its mechanisms and types. Studies have shown that the dynamic balance of dichogamy is influenced by a variety of factors[3,62,64−66,68,71−73,79,85,88,95]. Drawing on research in model plants such as A. thaliana[3,62,64−66,68,71−73,79,85,95], we have summarized the key mechanisms that affect dichogamy in plants, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Summary diagram of the factors affecting dichogamy in plants. PG, protogyny; PA, protandry; F, female; M, male; T6P, trehalose-6-phosphate. The yellow parts in the central morphological diagram represent the maturation of pistils and stamens; the clock represents flowering time; the gender symbols represent sex differentiation. Pink squares represent genes that affect flowering time, green squares represent genes that affect sex differentiation, and yellow squares represent genes that affect both flowering time and sex differentiation. Solid lines indicate direct interactions or regulatory relationships between two molecules, dashed lines typically indicate indirect interactions or regulatory relationships between two molecules, and T-shaped lines represent inhibition.

(i) Pollinators' interactions drive coevolution.

(ii) Environmental cues indirectly influence flowering time and sex differentiation through the regulation of key genes.

(iii) Genes involved in sex differentiation and flowering time form an interactive hub.

(iv) Epigenetic mechanisms couple environmental signals with genetic regulation.

These findings further elucidate the complexity and diversity of dichogamy for exploring its roles in plant reproduction, the maintenance of biodiversity, and hybrid breeding, thus providing important references and insights for future research.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200295, 32370386, and 32070372); the Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Shaanxi Province (2023-JC-JQ-22); the Shaanxi Fundamental Science Research Project for Chemistry and Biology (23JHQ029, 23JHZ009, and 22JHZ005); the Young Talent Fund of the Association for Science and Technology in Shaanxi, China (20240221); the Shaanxi key research and development program (2024NC-YBXM-064); and China's Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022MD723843).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: Zhao P, Li M, Wang M, Ou M; first draft preparation: Ou M, Yu S, Gao Z; table and figure preparation as well as manuscript editing and proofreading: Ou M, Yu S, Gao Z, Qiao X; revision of the manuscript: Li M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ou M, Yu S, Gao Z, Qiao X, Wang M, et al. 2025. The molecular and evolutionary basis of dichogamous reproductive strategies in flowering plants. Seed Biology 4: e015 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0015

The molecular and evolutionary basis of dichogamous reproductive strategies in flowering plants

- Received: 28 May 2025

- Revised: 19 July 2025

- Accepted: 05 August 2025

- Published online: 12 September 2025

Abstract: Dichogamy, a reproductive strategy in plants, describes the temporal separation of maturation between female and male reproductive organs within a flower or across flowers. Under similar environmental conditions, dichogamous species exhibit asynchronous development of their sexual organs during flowering, rather than morphological divergence. This phenomenon is classified into protandry (male-first maturation) and protogyny (female-first maturation) on the basis of the maturation sequence, into intrafloral or interfloral dichogamy on the basis of the spatial scope, and into complete or incomplete dichogamy depending on the degree of separation. Further subdivisions include synchronous or asynchronous types, determined by the synchronicity of sexual maturation within individual plants. Studies reveal that dichogamy arises from a dynamic equilibrium shaped by direct and indirect interactions of multiple factors. Biotic drivers, such as pollinators' behavior, promote co-evolutionary dynamics, while abiotic factors indirectly regulate key genes governing the timing of flowering, thereby modulating dichogamy. Hormonal signaling pathways critically regulate floral development and sexual differentiation, and epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, further fine-tune these processes. By temporally and spatially isolating sexual functions, dichogamy reduces selfing risks, enhances outcrossing, enriches genetic diversity, and underpins the breeding of high-yield, genetically diverse hybrids. However, this strategy entails trade-offs, such as resource allocation conflicts and restricted gene flow. The diverse ecological manifestations of dichogamy reflect its adaptive significance as a key driver in the evolution of plants' reproductive strategies. This review systematically examines the mechanistic basis, regulatory factors, and ecological implications of dichogamy, offering insights into its role in plant reproduction, biodiversity, and hybrid breeding.

-

Key words:

- Dichogamy /

- Gene expression regulation /

- Epigenetic modification