-

RNA therapeutics exhibit high selectivity and hold great potential for targeting the currently undruggable genes/genetic products, thereby providing entirely new therapeutic paradigms in disease treatment[1]. This capability stems from their distinct physicochemical and physiological properties[2]. To date, various types of RNA therapeutics have been developed, including messenger RNA (mRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), RNA aptamers, microRNA (miRNA), antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), short activating RNA (saRNA), RNA aptamers, circular RNA (circRNA), and CRISPR-based therapeutics, etc.[3]. These RNA therapeutics offer diverse therapeutic intervention through different functions and mechanisms[4]. RNA therapeutics such as siRNAs, ASOs, and miRNAs can specifically target mRNAs and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) via base pairing to downregulate the expression of disease-related genes[5]. In contrast, mRNA-based therapeutics are commonly used for protein replacement therapy or immunization after entering the cellular cytoplasm, which does not lead to irreversible genome changes, or genetic risks[6]. In addition, RNA aptamers act as small-molecule inhibitors and antibodies, directly blocking protein activity[7]. These RNA-based therapeutics have been widely used to treat a variety of major diseases, including cancer, infectious diseases, liver diseases, and lung disorders, and have shown remarkable treatment outcomes[8].

However, one of the significant challenges that has long-term hindered the therapeutic efficacy and application prospects of RNA therapeutics is insufficient cellular delivery, which is mainly caused by sophisticated in vivo biological barriers (e.g., effective cellular internalization and subsequent endosomal escape, phagocytosis by the mononuclear phagocyte system, clearance by the kidney, etc.) and unstable properties[9−11]. The limited targeted cell internalization is usually induced by their negatively charged phosphate backbone and large molecular weight[12]. Currently, advances in delivery technologies have provided a fast lane for the development of RNA delivery[13,14]. In particular, nanotechnology-derived carriers (e.g., lipid-based nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, polypeptide nanoparticles, inorganic nanoparticles, biomembrane/exosomes) are widely used to improve RNA delivery[15,16]. The key to improving delivery is the design optimization of carriers based on the characteristics of the disease or target cells[17]. However, the immunogenicity, biosafety, biocompatibility, and in vivo fate of the carriers should not be ignored for the translation[18].

Several RNA therapeutics have been approved, including siRNA, ASO, mRNA vaccines, and RNA aptamers, etc.[19]. For example, two mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273) received emergency marketing approval in 2020 for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infections[20]. Onpattro® (patisiran) is one of the siRNA-based RNA therapeutics approved for the clinical treatment of polyneuropathy in hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis[21]. Despite advances in the development of RNA therapeutics, their clinical translation and application still face several significant challenges, including unsatisfactory drug stability, large-scale production, product consistency, therapeutic bioequivalence, safety, and the risk of immunogenicity. Substantial efforts are being devoted to intensive mechanistic exploration, and to the continuous development of new strategies to promote RNA therapeutics in clinical disease treatment[22]. This review will summarize RNA therapeutics, including therapeutic mechanisms, delivery challenges, emerging RNA delivery strategies, clinical applications, and translation obstacles (Fig. 1). Advances in preclinical research and the clinical landscape of approved products and ongoing clinical trials are discussed, providing new insights and perspectives for future development and disease treatment.

-

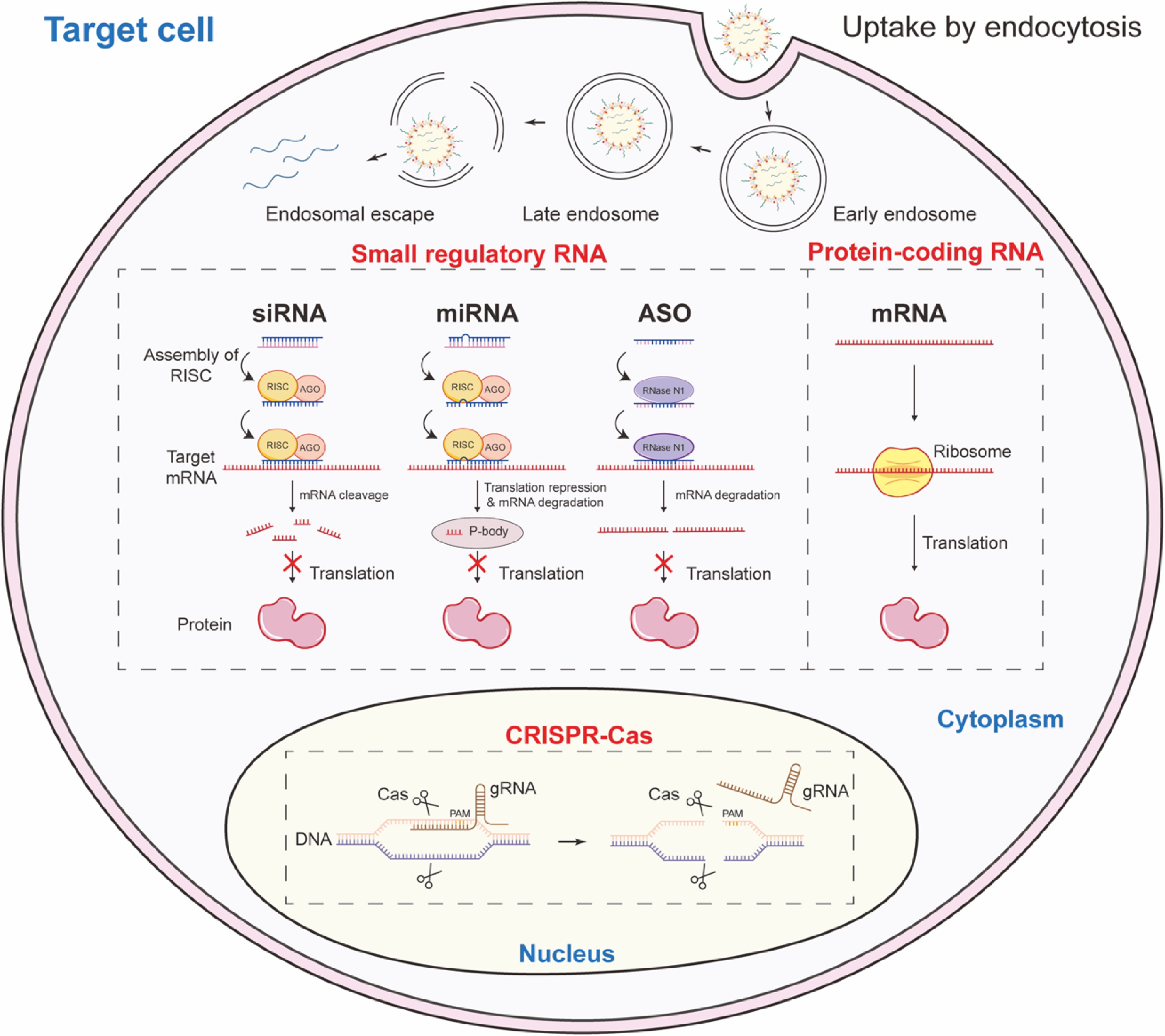

Therapeutic RNAs are broadly classified into three categories according to the action mechanism: small regulatory RNA; protein-coding RNA; and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-derived guide RNA[2].

Small regulatory RNAs include antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs). These molecules modulate gene expression by sequence-specific binding to target RNA[23]. ASOs are single-stranded, chemically modified deoxyribonucleotide fragments that inhibit gene expression by binding to specific mRNA sequences. The action mechanism includes degradation mediated by RNase H1 and the blocking of the transcriptional activity of target genes[24]. siRNAs are external double-stranded RNAs that guide the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to cleave complementary mRNAs, thus silencing the gene encoding the mRNA[25]. miRNAs, endogenous single-stranded RNAs that also operate through the RISC, typically induce translational repression or degradation of partially matched target mRNAs, influencing broader gene networks[26].

Protein-coding RNAs comprise messenger RNA (mRNA), self-amplifying RNA (saRNA), and circular RNA (circRNA). These RNAs are engineered to encode therapeutic proteins, and are translated by the host's cellular machinery[27]. mRNAs contain 5' caps and 3' poly tails, and facilitate translation initiation via formatting the complex of cap•eIF4E•eIF4G•PABP•poly(A), and are employed in vaccines, protein replacement therapies, and genome editing[28]. saRNA and circRNA represent new RNA forms that enhances translational durability and efficiency, reduces dosing, and prolongs protein expression[29].

CRISPR guide RNAs are engineered molecules that direct CRISPR-associated enzymes (e.g., Cas9, Cas12, Cas13) to specific genomic or transcriptomic targets. These RNAs facilitate precise genetic modifications, including cleavage, base editing, and prime editing. Base editors consisting of cytosine use guide RNAs to obtain precise nucleotide conversion, while prime editing systems employ longer guide RNAs to direct insertions, deletions, or substitutions[30].

Delivery challenges for RNA therapeutics

-

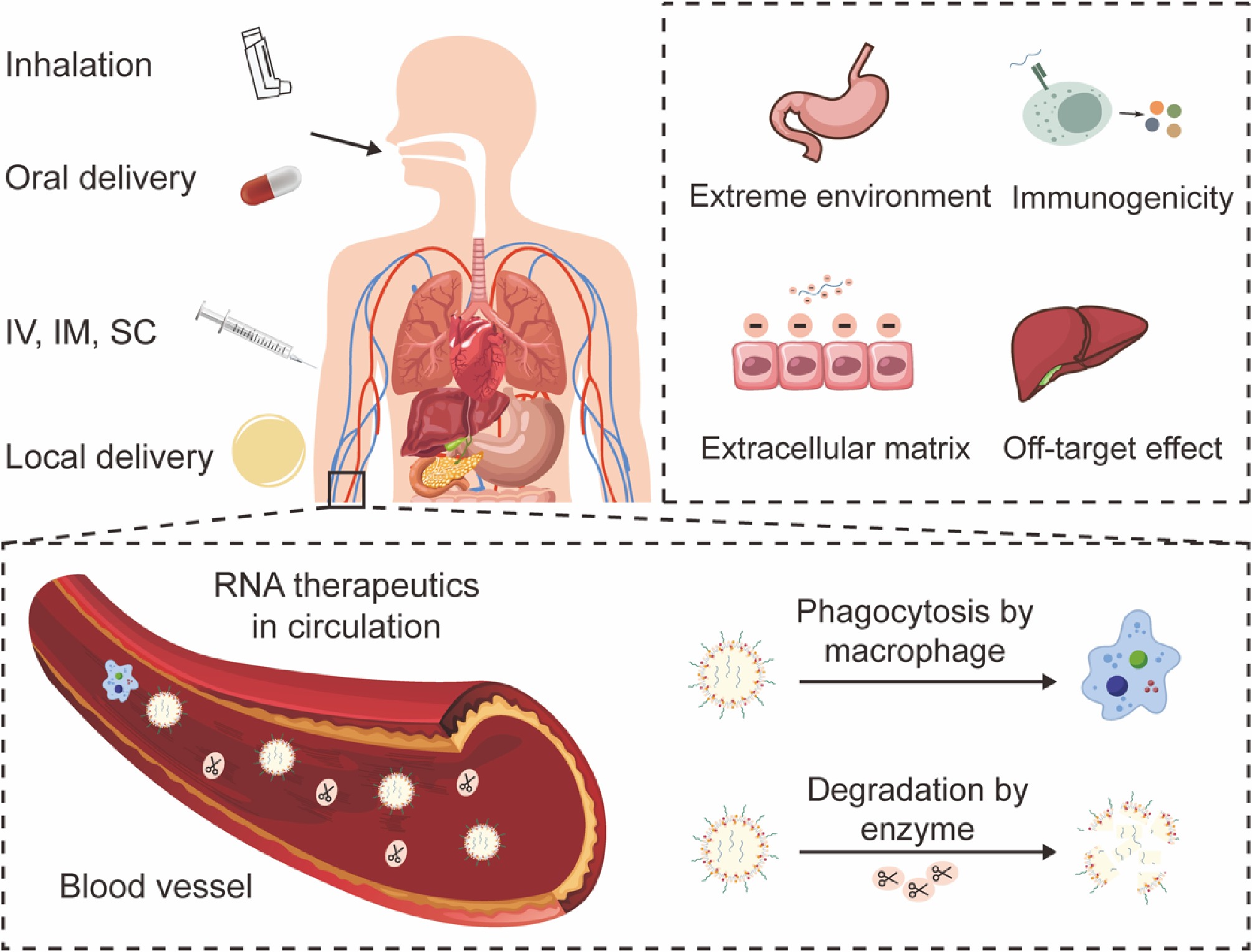

Although RNA holds great promise in drug development, the clinical translation of RNA therapeutics hinges on delivering the fragile RNA molecule to its intracellular site of action. This process is fraught with a multitude of sequential and interconnected challenges across biological scales, from the systemic to the molecular level (Fig. 2).

The choice of administration route is severely limited by RNA's inherent vulnerabilities, each of which presents unique hurdles. Intravenous (IV) injection is the direct method for systemic delivery, while exposing the RNA to the most hostile environment—the bloodstream—where nucleases (RNases) and immune factors are abundant[31]. IV administration requires sophisticated delivery systems to ensure the RNA survives circulation and reaches the target tissue. Subcutaneous (SC) and intramuscular (IM) injections offer a less harsh initial environment than IV injections. However, the diffusion of large, hydrophilic RNA molecules through the dense extracellular matrix (ECM) of tissues is inefficient. The journey from the injection site to the vasculature, and then to the target organ is a significant barrier, often leading to localized degradation, and limited bioavailability[32]. Oral administration of naked RNA is tough. RNAs are degraded rapidly in the gastrointestinal tract by low pH conditions in the stomach, and a high concentration of RNases in the intestines[33]. Furthermore, the gut epithelium is a formidable barrier to large, charged molecules. Although inhalation, intrathecal, and topical administration are being explored for localized delivery, they still face barriers such as mucosal clearance, epithelial barriers, and tissue-specific RNases[34].

Upon entering the systemic circulation, naked RNA is subject to hydrolysis of the phosphodiester backbone and degradation by RNases. Naked RNA is degraded within seconds to minutes, possessing a circulatory half-life of less than several minutes[35]. In addition, the kidneys filter small molecules and nanoparticles below a certain size threshold (~5–10 nm). Thus, small regulatory RNAs will be rapidly cleared from the blood through glomerular filtration. Meanwhile, neutralizing antibodies and phagocytic clearance further reduce their bioavailability[30].

If the RNA survives the bloodstream and reaches the target cell, it must overcome several cellular barriers. The inherent unfavorable physicochemical properties of RNA molecules make them unsuitable for crossing biological membranes. High molecular weight and large hydrodynamic size preclude passive diffusion through membrane pores. At the same time, the strong negative charge causes strong electrostatic repulsion with the negatively charged glycocalyx and phospholipid heads of cell membranes, forcing reliance on endocytic pathways (e.g., clathrin-mediated, caveolin-mediated, micropinocytosis). The efficiency of this uptake is highly dependent on the cell type and the surface properties of the delivery carrier[36,37]. After endocytosis, the RNA is trapped within endosomes, which mature and acidify (pH drops to ~5.0–6.0) before fusing with lysosomes. Lysosomes contain a suite of digestive enzymes (RNases, proteases) that will degrade both the carrier and its RNA cargo. A vast majority of internalized RNA is lost to this pathway[38]. The critical challenge is to engineer carriers that can disrupt the endosomal membrane and facilitate the 'endosomal escape' of the RNA into the cytosol before it is degraded. For small regulatory RNA and mRNA, the cytosol is the delivery destination. For CRISPR systems targeting nuclear RNA, the vector must further pass through the nuclear membrane via the nuclear pore complex, a process that is highly inefficient unless during cell division[39].

Essentially, even with efficient delivery, off-target, and toxicological side effects should still be considered. The introduction of siRNA could lead to reduced expression of genes other than those targeted, potentially posing a danger in the treatment of disease[40]. Off-target effects can be attributed to two mechanisms: first, siRNA can tolerate several mismatches on the target mRNA, forming partially complementary pairings while continuing to exert its gene-silencing effect. The 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of these transcripts is complementary to the 5' end of the siRNA sense strand[41]. Second, the RNAi level in the body is saturated when the external siRNAs are transported into the cells; they will compete with endogenous miRNAs, which are, therefore, subject to interference[42]. Some studies have found that the specific structure of RNA sequences and drug carriers can lead to the release of cytokines such as IFN-α and IFN-P[43,44], potentially triggering a potent innate immune response.

Overcoming these challenges requires a multi-pronged engineering approach combining chemical modification of the RNA itself to enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity, and the development of advanced delivery systems (LNPs, GalNAc conjugates, polymers) designed to navigate this complex biological landscape, protect their cargo, and release it functionally at the correct site of action. The specific characteristics that an efficient RNA delivery system should possess include: (1) effective encapsulation and protection of RNA to prevent nuclease degradation during systemic delivery; (2) prolonged circulation time in the bloodstream to avoid rapid clearance by the kidneys and phagocytosis by the liver or spleen; (3) enhanced penetration and accumulation in target tissues/organs; (4) promotion of cellular internalization by target cells; (5) avoidance of lysosomal degradation during intracellular transport; (6) enhanced release of RNA in the cytoplasm to exert its genetic function.

-

To date, several RNA therapeutics approaches have been approved for disease treatment, including siRNA, miRNA, mRNA, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), and aptamers[10,45]. Despite significant progress in these RNA therapies, they still face challenges related to fabrication technology, safe and effective delivery, as well as clinical translation[46−48]. Therefore, researchers are still striving to develop novel RNA delivery strategies to enhance the stability, targeting, and bioactivity of enzymes, promote cellular uptake and endosomal escape, while avoiding renal clearance and reducing immunogenicity (Fig. 3). Structural modification and the use of advanced delivery vectors/materials for encapsulation are common strategies in RNA therapy[49].

Structural modification

Ribose modification

-

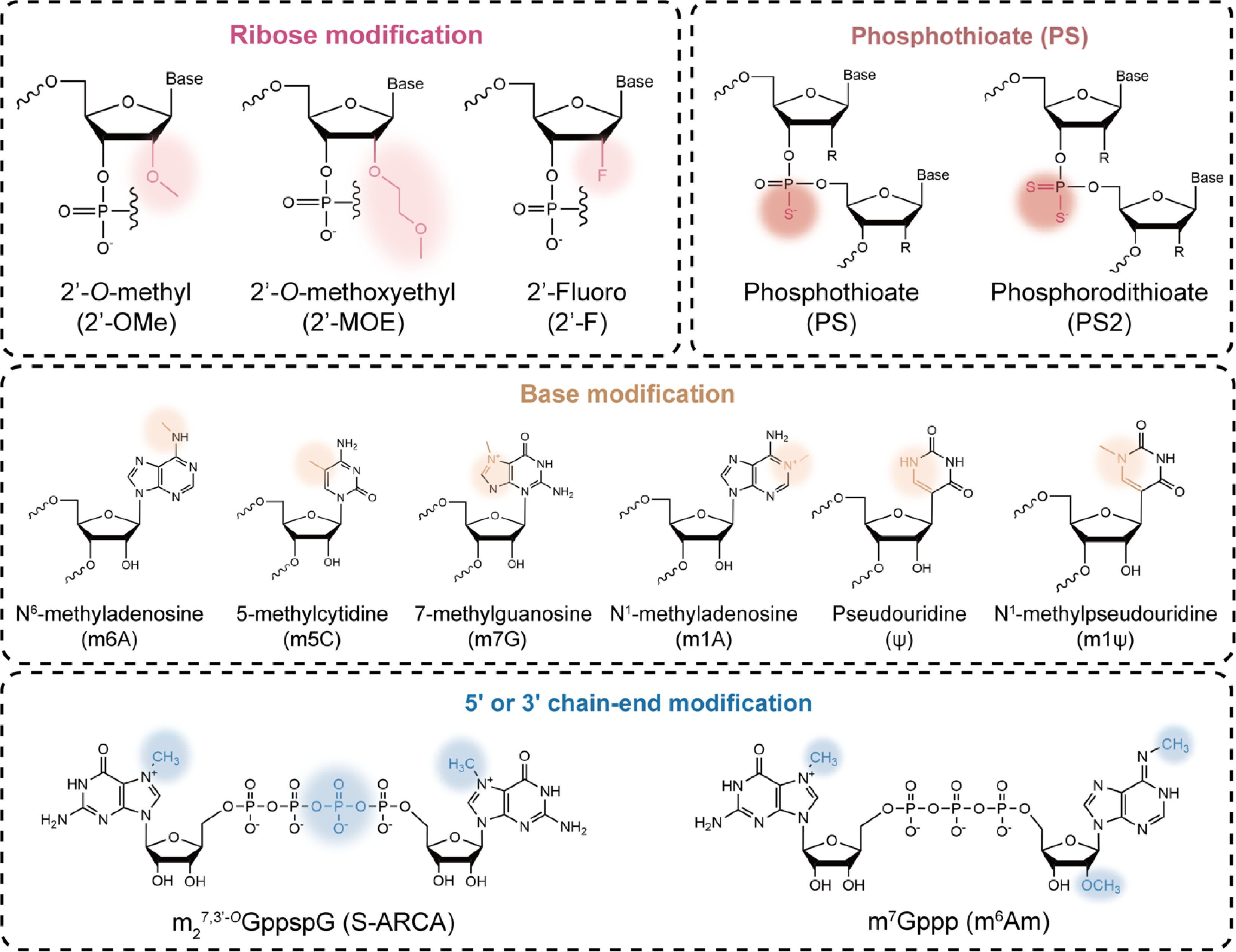

Ribose chemical modifications involve replacing the 2'-OH group of the ribose sugar in RNA nucleotides with other atoms or groups, also known as 2'-ribose modifications. For instance, 2'-O-Methyl (2'-OMe), 2'-Methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), and 2'-Fluoro (2'-F) are involved[50]. These modifications enhance RNA stability against RNases by mimicking the biophysical properties of the 2'-OH, while preventing RNA from activating innate immune pattern recognition receptors, Toll-like receptors (TLRs)3/7/8, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA-5), ultimately enhancing its affinity for target sequences[51].

2'-MOE, a chemical modification commonly used in ASOs, replaces the 2'-OH group with a methoxyethyl group to improve oligonucleotide stability by increasing resistance to RNase, significantly prolonging the half-life[52]. For instance, Spinraza® is a fully phosphorothioate and 2'-MOE-modified ASO drug approved for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)[53]. However, it is worth noting that 2'-MOE modification at the 5' or 3' ends may affect siRNA silencing efficiency, so modifications are often applied to the central region of the siRNA sequence[13].

In addition to 2'-MOE modification, 2'-OMe and 2'-F are commonly used for modifying siRNA compared to ASOs. To integrate multiple beneficial properties to enhance binding affinity and reduce immunogenicity, oligonucleotide therapeutics commonly comprise multiple modifications. For instance, Amvuttra® incorporates 2'-OMe, 2'-F, and 2'-deoxy chemical modifications to enhance therapeutic efficacy against hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR)[54]. In contrast, ribose modifications are incompatible with RNase H activity and are therefore not commonly used in RNase H-dependent ASO therapeutics[55].

Phosphate backbone modification

-

Phosphothioate (PS) modification replaces a non-bridging oxygen atom (O) on the phosphate backbone with a sulfur atom (S), forming a PS bond[56]. The PS modification enhances RNA binding to plasma proteins, prolongs half-life, and improves tissue permeability, making it one of the most common chemical modifications in ASO therapeutics[57]. A PS-modified aptamer, S-XQ-2d, has been reported to exhibit approximately 13-fold higher binding affinity for its target CD71 protein compared to the unmodified aptamer[58]. Furthermore, the stereochemical changes induced by the PS bond can influence the efficacy of the final oligonucleotide. PS bonds in the Sp configuration have been reported to be more stable than those in the Rp configuration, preventing drug inactivation through a stereo-protective mechanism[59].

Furthermore, the impact of phosphate backbone modifications on RNA function may differ from nucleotide modifications. For instance, Nikan et al. observed that siRNA modified with monoalkyl phosphonate bonds exhibited enhanced specificity and therapeutic properties, with optimal efficacy when these modifications were positioned at the inter-nucleotide bond 6–7 positions from the 5' end of the guide strand[60]. Notably, PS modifications also reduce the affinity of nucleic acid therapeutics for their complementary nucleotide sequences and induce off-target effects. siRNAs modified at every linkage site have been reported to exhibit lower activity, leading to the common practice of modifying most PS bonds only at the siRNA ends[61]. Additionally, high-level PS modification may increase non-specific binding between nucleic acids and plasma proteins, thereby altering biodistribution, accumulation, and clearance processes, and exacerbating toxic reactions[62].

Base modification

-

Nucleoside modifications primarily involve chemical alterations of nucleosides within RNA sequences, including pyrimidines and purines. Typically, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent base modification in eukaryotic RNA, dynamically regulated by three enzymes[63]. The biological significance of m6A largely depends on m6A 'readers' that control mRNA fate and function[64,65]. However, m6A modification is unevenly distributed within RNA and is more prevalent in mature mRNA. Dysregulation of this modification has also been linked to various human diseases[66,67].

In addition, pseudouridine (ψ) modification, also known as the 'fifth nucleotide' of RNA, serves as a natural isomer of the nucleoside uridine and represents the most prevalent natural RNA modification in nature[68,69]. ψ-modified RNA effectively avoids activating pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs, significantly reducing RNA immunogenicity while enhancing translation efficiency[70]. Compared to ψ, N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ) is less likely to activate protein kinase R (PKR), which offers greater advantages in reducing RNA immunogenicity and promoting translation capacity[71−73]. Moreover, other commonly used examples of RNA base modifications include 7-methylguanosine (m7G), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), and 5-methylcytidine (m5C), etc.[74], which also have significant implications for the development of therapeutic RNA drugs.

5' or 3' chain-end modification

-

5'-end cap structure modification ensures mRNA stability and efficient translation by synthesizing cap analogs, such as Anti-Reverse Cap Analog (ARCA), and CleanCap Analogue[75]. Given the 5' cap's role in regulating mRNA stability and translational efficiency, researchers are engaged in identifying and synthesizing chemically modified 5' caps. For instance, functional mRNAs were synthesized using either vaccinia virus capping enzyme modification techniques or click chemistry to produce diverse 5' cap analogues[76,77].

Furthermore, optimizing the length and sequence of the 3'-terminal polyadenylic acid (poly(A)) tail can enhance mRNA stability against RNases and prolong its half-life, thereby regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level[78,79]. Longer poly(A) tails may enhance mRNA stability and transfection efficiency; however, excessively elongated tails may paradoxically reduce protein output. Reports indicated that an optimal poly(A) tail length of approximately 100 nt yields the highest translation rates[80].

Drug carriers/special materials

-

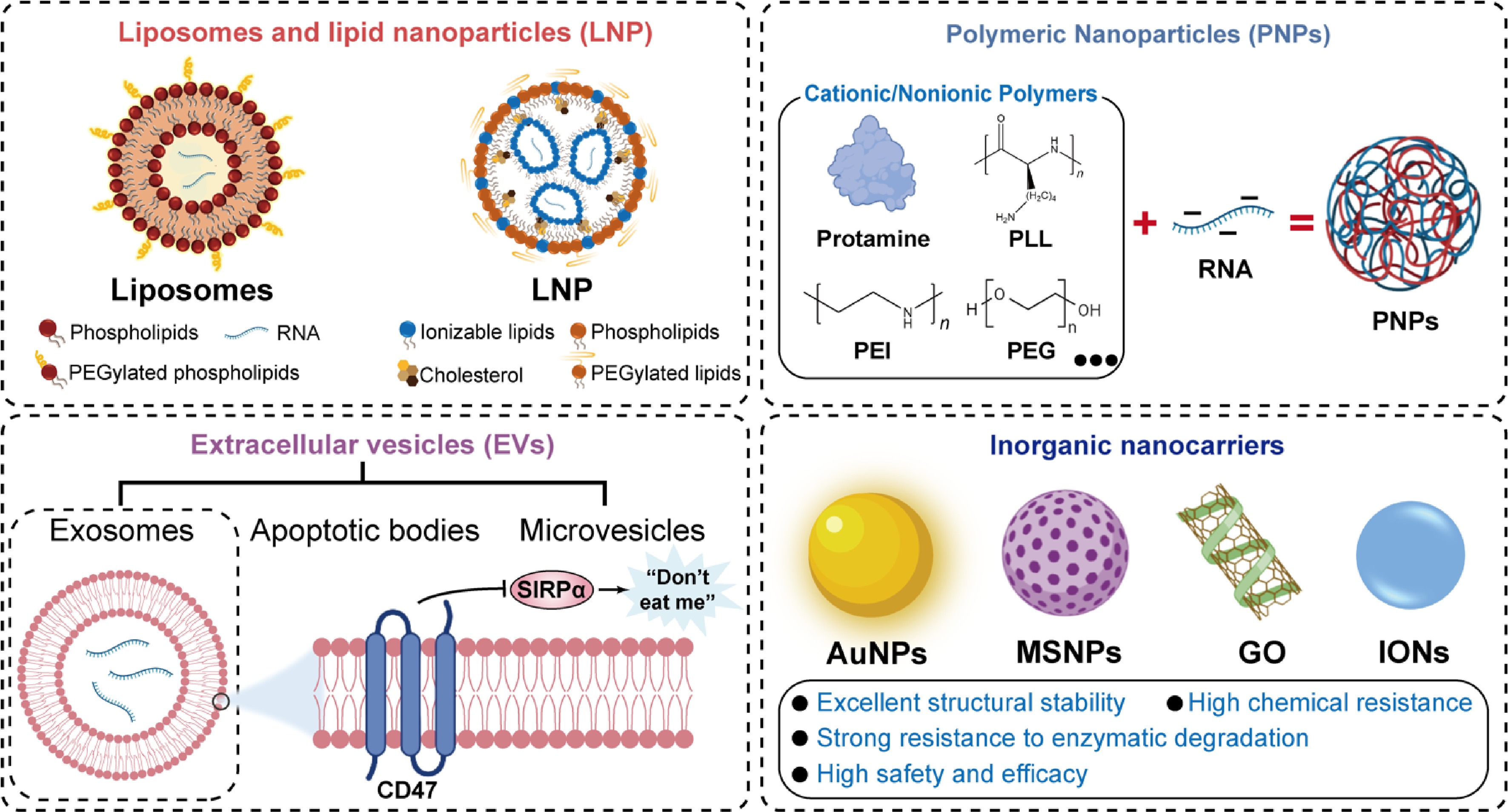

Generally, mRNA delivery carriers are categorized into viral and nonviral carriers. However, viral carriers are not widely used due to their higher immunogenicity, toxicity, and carcinogenic risks[81,82]. Nonviral carriers exhibit lower immunogenicity and higher delivery efficiency, making them the preferred choice for mRNA delivery. Here, nonviral carriers are mainly discussed (Fig. 4).

Liposomes and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)

-

Liposomes are bilayer spherical vesicles formed through the self-assembly of amphiphilic phospholipids, with several formulations already approved for clinical use[83−85]. Positively charged cationic liposomes promote particle uptake and endosomal escape; however, they still face issues such as poor stability and high immunogenicity[86]. To address the limitations, chemically modified lipids are incorporated into the liposomes[87,88].

LNPs have emerged as a prominent nucleic acid delivery platform[89]. Four LNP-based RNA therapeutics, including Onpattro®, Comirnaty®, Spikevax®, and mResvia®, were approved for clinical use. Typically composed of ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEGylated lipids, LNPs offer advantages including controllable lipid synthesis, flexible manufacturing processes, and robust nucleic acid encapsulation capacity[90]. Rational design of lipid structures and surface modifications significantly improves pharmacokinetic profiles, reduces immunogenicity, extends circulation half-life, and maintains high transfection efficiency[91]. Recently, precision-mixing methods by microfluidic technology enabled the efficient and controllable synthesis of LNPs, providing crucial support for their clinical translation[92,93]. Nonetheless, LNPs consistently demonstrated only a modest ability to enhance DNA transfection. LNP-based RNA therapeutics are expensive due to the use of ionizable lipids, limiting their application. In addition, LNPs demonstrate significant shortcomings, such as a severe immune response, complex manufacturing, and formulation discrepancies.

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs)

-

PNPs are a class of artificially synthesized nanocarriers constructed from biodegradable or biocompatible polymers through methods such as self-assembly. Due to RNA's relatively high negative charge and its sensitivity to nucleases, positively charged substances are introduced to bind with negatively charged RNA, forming stable complexes[94]. These substances include positively charged proteins (such as protamine)[95], polyethyleneimine (PEI), poly-L-lysine (PLL), and polycaprolactone (PCL)[96−98]. However, these cationic components also trigger acute neutrophil infiltration and a cascade of inflammatory responses, exhibiting significant toxicity[99]. Nonionic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), act as 'seeding agents' that promote nanoparticle formation at ambient conditions by increasing the local concentration of precursor RNA[100,101]. These interactions protect RNA from degradation and enhance cellular delivery by facilitating endosomal escape via proton-sponge effects[102]. No PNP-based RNA therapeutics are approved for clinical use so far. However, PNPs demonstrate less immune stimulation and liver accumulation and, as a result, could contribute to the RNA-based therapeutic landscape.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs)

-

EVs with a diameter of 50–150 nm are naturally occurring vesicles actively secreted by cells that possess biological activity[103]. EVs can effectively encapsulate RNA, protect it from degradation, facilitate its crossing biological barriers, and target cells of interest, representing a safe and efficient method for RNA therapy[103,104]. Based on their biogenesis and size characteristics, EVs are primarily categorized into exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies[105]. Exosomes, with well-defined membrane structure and rich surface protein composition, have the potential to improve RNA delivery. For instance, CD47 expressed on the exosome membrane transmits a 'do not eat me' signal through interaction with signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα), effectively evading clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system and prolonging circulation time in vivo[106,107]. Various bioengineering techniques were used to functionalize exosomes, such as incorporating specific targeting peptides or fusion proteins, thereby improving tissue tropism and cellular uptake capacity[108,109]. Despite the significant potential in RNA therapeutics, biomimetic EVs face multiple challenges for clinical application, including standardized large-scale production, precise controllability of targeted modifications, and high preparation costs[110]. So far, no therapeutic applications of EV-based RNA delivery systems have been approved or entered clinical trials.

Inorganic nanocarriers

-

Inorganic nanocarriers represent a novel class of nonviral delivery systems composed of inorganic materials. Their unique size-dependent properties, precisely tunable physicochemical characteristics, and diverse functionalizable interfaces have demonstrated several advantages, including structural stability and high chemical resistance[111]. For instance, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) possess outstanding optical properties and easily modifiable surface chemistry[112]. Their surfaces can covalently bind RNAs via gold-sulfur bonds for functionalization, achieving temporally and spatially controlled RNA release through photothermal effects[113]. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) are gaining attention as potential RNA therapeutic carriers due to their highly ordered pore structures, large specific surface areas, and tunable pore sizes[114]. Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as iron oxide nanoparticles (IONs) and graphene oxide (GO), also represent compelling platforms for RNA delivery[115,116]. Whereas the prospects for inorganic carriers in RNA therapy are unclear due to the risks associated with complex metabolism and elimination.

-

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are increasingly integrated into the RNA therapeutics development process, providing powerful tools to accelerate drug discovery, optimize design strategies, enhance delivery efficiency, and predict clinical efficacy[117,118]. By integrating large-scale biological data, these computational methods effectively address key challenges in RNA-based drug development.

AI is demonstrating its potential to drive the future of RNA drug development. The accuracy of AI models such as AlphaFold further underscores the transformative impact of AI[119]. AI-driven large models, combined with high-resolution 3D visualization technology, enable researchers to gain detailed insights into RNA structures and their dynamic changes. By analyzing omics data, AI platforms can simulate and predict RNA-target interactions in real time, thereby enabling rational design of RNA molecules[120]. Also, breakthroughs in deep learning-driven approaches, such as large language models like ChatGPT, have revolutionized the analysis of long RNA sequences[121]. These advanced AI models assist interactive RNA generation platforms in generating and refining RNA sequences based on criteria like target specificity. Simultaneously, RNA-protein affinities can be further analyzed from the predicted sequences[122].

Beyond AI, ML is a core method for achieving AI. One of the standout contributions of ML tools to RNA therapeutics lies in the design of delivery systems, particularly in the discovery of mRNA delivery[123]. ML aids in screening and designing lipids by predicting the efficacy, stability, and biodistribution characteristics of LNPs[124]. Its combination with high-throughput screening enables the identification of optimal lipid formulations for achieving targeted tissue delivery and escaping endosomal sequestration[125]. For instance, Li et al.[126] reported a method that integrates ML and high-throughput synthesis to discover ionizable cationic lipids. They identified a lipid superior to the established benchmark lipid (SM-102) for transfecting muscle and immune cells across multiple tissues. In addition, ML models can be used to model interactions between RNA and small molecules, including binding sites, conformations, performance, and affinity[127].

Traditional experimental techniques are gradually being replaced by AI-ML tools in RNA synthesis and sequencing, characterization methods, transfection efficiency, and toxicity assessment. These tools can save time, reduce costs, and, to a certain extent, produce more precise results. However, even when AI-ML tools perform well on specific datasets, they still lack universality. Meanwhile, the risk of ethical issues, data loss, high maintenance costs, and frequent software upgrades will also need to be addressed in the future. In summary, advanced AI-ML tools will revolutionize the design, optimization, and delivery strategies for RNA therapeutics, while efficient big-data model development will open new pathways for RNA therapies.

-

RNA therapy aims to achieve precise disease treatment by intervening at the mRNA level, modulating disease-causing proteins at their source[128]. Currently approved RNA drugs primarily address rare monogenic disorders using ASOs or siRNAs to silence or correct defective genes, as well as to modulate hepatic metabolism and prevent infectious diseases[129]. Meanwhile, the pipeline of investigational RNA drugs has expanded considerably to combat cancer, neurological disorders, and cardiovascular diseases[130]. The use of delivery strategies allows RNA therapies to extend their therapeutic reach beyond the liver to other tissues and organs, ultimately targeting previously 'undruggable' pathological pathways[131]. Based on the targeted disease types, RNA therapeutics have established a clear, broadly deployed clinical application landscape (Table 1). Here, the targets, RNA-based products, their market advancements, and RNA therapeutics under clinical investigation, for the treatment of major diseases, will be discussed (Table 2).

Table 1. RNA therapeutics on market for disease treatment.

Disease classification Classification Development code Indications Target/mechanism of action RNA technology platform Delivery system Route of administration Launch year Ref. Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1345 Respiratory syncytial virus Respiratory syncytial virus stabilized prefusion F glycoprotein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2024 [145] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2 spike protein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2020 [177] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1283 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusmRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2025 [178] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2 spike protein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2020 [179] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine ARCT-154 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2 spike protein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2025 [180] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine SYS6006 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2 spike protein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection 2023 [181] Liver and metabolic diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy KJX839 Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) and cardiovascular risk reduction PCSK9 mRNA siRNA GalNAc Subcutaneous injection 2020 [182] Hepatic and metabolic diseases RNA aptamer therapy NX1838 Neovascular (Wet)

age-related macular degenerationSpecifically targets

the VEGF165

isoformRNA aptamer Not required Intravitreal injection 2004 [183] Genetic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy Nusinersen Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) Modulation of SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing ASO Ligand-conjugated active delivery Intrathecal injection 2016 [184] Genetic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy AVI-4658 Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) DMD gene pre-mRNA ASO No specialized delivery system required Intravenous infusion 2016 [185] Genetic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy IONIS-TTRRx Hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR) mRNA silencing of

the TTR geneASO Ligand-conjugated active delivery Subcutaneous injection 2018 [186] Genetic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy BIIB067 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Targeted degradation of SOD1 mRNA ASO Ligand-conjugated active delivery Intrathecal injection 2023 [187] Genetic diseases CRISPR gene editing therapy CTX001 β-thalassemia,

sickle cell diseaseEdits the BCL11A gene in autologous hematopoietic stem cells to reactivate

fetal hemoglobin productionCRISPR-Cas9 Electroporation Intravenous infusion 2023 [188] Genetic diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy ALN-TTR02 Hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR) mRNA silencing of

the TTR genesiRNA LNPs Intravenous infusion 2018 [189] Genetic diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy ALN-AS1 Acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) Targeted silencing

of ALAS1 mRNAsiRNA GalNAc Subcutaneous injection 2019 [190] Table 2. RNA therapeutics under investigation for disease treatment.

Disease classification Classification Development code Indications Target/mechanism of action RNA technology platform Delivery system Route of administration Status Ref. Cancer Personalized neoantigen vaccine mRNA-4157 Melanoma Personalized neoantigen mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase II [135] Cancer Personalized neoantigen vaccine BNT122 Melanoma, colorectal cancer, non-small cell

lung cancerPersonalized neoantigen mRNA LNPs Intravenous

infusionPhase II [191] Cancer Shared-antigen vaccine BNT111 Melanoma Shared-antigen mRNA LNPs Intravenous

infusionPhase II [137] Cancer Shared-antigen vaccine CV9104 Prostate cancer Shared-antigen mRNA Protamine complex Intradermal injection and subcutaneous injection Phase II [138] Cancer RNA interference (RNAi) therapy MTL-CEBPA Hepatocellular carcinoma CEBPA gene activation siRNA LNPs Intravenous

infusionPhase II [132] Cancer RNA interference (RNAi) therapy siG12D-LODER Pancreatic cancer KRAS G12D silencing siRNA LODER™ (LOcal Drug EluteR) Endoscopic Intratumoral injection Phase II [192] Cancer mRNA-encoded cytokine/antibody mRNA-2752 Solid tumors, Lymphoma Cytokine encoding mRNA LNPs Intratumoral injection Phase I [193] Cancer microRNA therapy MRX34 Advanced or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), melanoma, lymphoma, and various other solid tumors miR-34a mimic Double-stranded

RNA mimicLNPs Intratumoral injection Phase I [194] Cancer microRNA therapy MesomiR-1 Malignant pleural mesothelioma, advanced non-small cell lung cancer miR-16 mimic Double-stranded

RNA mimicTargeted Bacterial Minicells Intratumoral injection Phase I [195] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1010 Influenza Hemagglutinin (HA) glycoproteins of four influenza virus strains mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase III [196] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine PF-07252220 Influenza Hemagglutinin (HA) glycoproteins of four influenza virus strains mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase I [197] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1647 Cytomegalovirus Cytomegalovirus mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase III [198] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1443 Cytomegalovirus Hemagglutinin (HA) protein of influenza virus mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase I [199] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1189 E–B virus Epstein–Barr virus envelope glycoproteins gH, gL, gp42, and gp220 mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase I/II [200] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1215 Nipah virus Nipah virus prefusion-stabilized F protein and G protein monomer mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase I [201] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1893 Zika virus Zika virus mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase II [202] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1608 Herpes simplex virus Herpes simplex virus mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase I/II [203] Infectious diseases Prophylactic mRNA vaccine mRNA-1283 SARS-CoV-2/

COVID-19 virusSARS-CoV-2 spike protein mRNA LNPs Intramuscular injection Phase III [178] Infectious diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy ARO-HBV Hepatitis B virus Degradation of HBV mRNA siRNA Dynamic Polyconjugates Subcutaneous injection Phase I/II [204] Liver and metabolic diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy Fazirsiran α-1 antitrypsin

deficiency (A1ATD)Specific silencing of mutant SERPINA1 siRNA TRiM™ Subcutaneous injection Phase III [161] Liver and metabolic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy Vupanorsen Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) and cardiovascular risk reduction Targeted silencing of ANGPTL3 ASO GalNAc Subcutaneous injection Phase II [205] Liver and metabolic diseases Messenger RNA (mRNA) therapy mRNA-3927 Propionic acidemia (PA) PCCA and PCCB mRNA LNPs Intravenous

infusionPhase I/II [164] Liver and metabolic diseases Messenger RNA (mRNA) therapy ARCT-810 Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) Encoding a functional

OTC enzymemRNA LNPs Intravenous

infusionPhase II [206] Liver and metabolic diseases RNA interference (RNAi) therapy AB-729 Hepatitis B virus GalNAc-conjugated siRNA targeting all HBV RNA transcripts that produces

a marked and durable reduction in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levelssiRNA GalNAc Subcutaneous injection Phase II [207] Hepatic and metabolic diseases Hybrid antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy TPI ASM8 Asthma mRNA targeting the two signaling molecules CCR3 and the βc chain ASO No delivery system required Nebulized inhalation Phase II [208] Hepatic and metabolic diseases RNA aptamer therapy ARC1779 Thrombotic Microangiopathy, Acquired Hemophilia,

and other thrombotic disordersTargets the A1 domain of von Willebrand Factor (vWF) RNA aptamer Not required Intravitreal

injectionPhase III [209] Hepatic and metabolic diseases RNA aptamer therapy ARC1905 Age-related Macular Degeneration Complement C5 protein RNA aptamer Not required Intravitreal

injectionPhase III [210] Genetic diseases Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy RO7234292 Huntington's disease (HD) Targeted silencing of

mutant huntingtin mRNAASO Ligand-conjugated active delivery Intrathecal

injectionPhase III [211] Genetic diseases CRISPR gene editing therapy NTLA-2001 Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis Knocks out the TTR gene in hepatocytes to reduce the production of disease-causing transthyretin protein CRISPR-Cas9 LNPs Intralesional injection Phase I/II [212] Genetic diseases CRISPR gene editing therapy NTLA-2002 Hereditary

angioedemaKnocks out the Kallikrein B1 gene in hepatocytes to reduce bradykinin and prevent swelling attacks CRISPR-Cas9 LNPs Intralesional injection Phase I/II [213] Genetic diseases CRISPR gene editing therapy EDIT-101 Leber Congenital Amaurosis Type 10 Use CRISPR to remove the pathogenic mutation in intron 26 of the CEP290 gene in retinal cells to restore normal protein function CRISPR-Cas12a Adeno-associated virus CRISPR-Cas12a Phase I/II [214] Cancer

-

RNA-based therapies have demonstrated significant potential in cancer treatment. The therapies currently in clinical trials are mainly divided into two categories: mRNA vaccines and RNAi therapies. RNA therapeutics can precisely modulate cancer targets. For instance, the first small activating RNA (saRNA) was used to activate CEBPA in the liver, promoting the differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells toward a normal phenotype and inhibiting tumor proliferation[132,133]. The clinical trials of saRNA therapy are ongoing (NCT05097911, NCT02716012). Compared to genetic disorders and metabolic diseases, few RNA therapeutics have been approved for cancer treatments. Among these, the combination therapy of mRNA-4157 (V940) with Keytruda® represents a significant advancement of mRNA technology in cancer treatment[134]. mRNA-4157 (V940) is a personalized mRNA cancer vaccine developed by Merck and Moderna. It employs mRNA technology to encode up to 34 personalized tumor neoantigens, activating specific T-cell immunity and establishing long-term memory to treat high-risk melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer[135,136]. In Phase I/II clinical trials in combination with pembrolizumab, this vaccine demonstrated favorable efficacy[134,135]. As shared-antigen cancer vaccines, both BNT111 and CV9104 have demonstrated robust and durable antitumor efficacy in clinical trials in melanoma and prostate cancer patients, respectively[137,138]. Furthermore, several clinical trials of RNA therapeutics for cancer (e.g., lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers) are ongoing, targeting well-known oncogenes such as KRAS, MYC, and STAT3[139,140].

RNA therapeutics have introduced a paradigm shift in cancer treatment. However, their full maturation requires overcoming significant translational challenges. The advancements require isolated technological breakthroughs and the deep integration of delivery technologies, bioinformatics, immunology, and clinical medicine. RNA therapeutics are poised to evolve from a cutting-edge technology into a mainstream pillar of oncology by addressing delivery limitations, enlarging application scenarios, and reducing costs. In the coming years, increasing RNA drugs are expected to enter the cancer treatment market.

Infectious diseases

-

For the prevention and control of infectious diseases, RNA therapeutics offers a highly efficient and versatile platform for vaccine development compared to traditional strategies, effectively addressing rapid viral mutations by targeting highly conserved regions of the viral genome, providing defense against potential future novel viruses[141]. The most representative example is the COVID-19 pandemic that erupted in late 2019, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which prompted the rapid launch of multiple vaccine development programs worldwides[142]. Among these, mRNA vaccines (mRNA-162b2 and mRNA-1273) utilizing LNP delivery to encode the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein were approved for emergency use following accelerated development to curb the spread of COVID-19[143]. Subsequently, more candidate COVID-19 vaccines have entered clinical trials[144]. Another preventive mRNA vaccines, mRESVIA, utilizes LNP delivery technology to elicit specific immune responses within cells. In a Phase III clinical trial, it demonstrated 83.7% efficacy in preventing lower respiratory tract disease associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in adults aged 60 years and older[145]. The vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of RSV infection, becoming the second kind of marketed mRNA vaccine following COVID-19 vaccines.

JNJ-3989, a therapeutic vaccine, is an RNAi-based therapy used to treat chronic hepatitis B by specifically silencing viral mRNA, reducing patients' levels of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and holds considerable promise for achieving a functional cure in combination with other agents[146,147]. The transition from emergency pandemic response toward building a more agile, broad-spectrum, and accessible line of defense against infectious diseases is expected. By overcoming challenges related to stability, safety, and accessibility, and expanding their applications from prophylaxis to treatment, RNA technology will play a leading role in ending pandemic threats and even tackling some of the most intractable chronic infections.

Nervous system diseases

-

RNA therapeutics demonstrate significant potential in treating neurological disorders due to their ability to target gene transcripts directly. Huntington's disease, one of the most representative neurological disorders, is caused by an excessive expansion of the CAG repeat sequence in the Huntington (HTT) gene[148]. Tominersen® is an ASO drug developed for Huntington's disease that inhibits HTT protein synthesis by targeting HTT mRNA, thereby slowing disease progression[149]. However, Tominersen® was halted in Phase III clinical trials due to failure to meet efficacy endpoints (NCT03761849).

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is another representative genetic neurological disorder classified as an autosomal recessive disease[150]. In 2019, Novartis Pharmaceuticals developed Zolgensma® (Onasemnogene abeparvovec), a gene therapy for SMA. The therapy promoted the expression of SMN protein in patients by delivering the survival motor neuron gene 1 (SMN1)[151]. AVXS-101 is another RNA therapy that delivers the SMN2 gene, developed by the Novartis subsidiary AveXis[152]. However, the US FDA partially suspended clinical trials of AVXS-101 in October 2025 due to safety concerns (NCT03505099). Additionally, RNA therapy shows increasing potential for treating Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases by targeting the amyloid precursor protein (APP)/BACE1 and α-synuclein (SNCA)[153,154].

Hepatic and metabolic diseases

-

RNA therapeutics have also achieved remarkable success in hepatic and metabolic diseases, expanding from treating rare disorders to standard conditions. For instance, familial chylomicronemia syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder associated with hypertriglyceridemia and severe acute pancreatitis[155]. Waylivra® (Volanesorsen) is an ASO drug that significantly reduces plasma triglyceride levels by targeting apolipoprotein CIII (apo-CIII) mRNA to inhibit its synthesis[156]. Furthermore, primary hyperoxaluria is another rare autosomal recessive disorder. Oxlumo® (Lumasiran) is an RNAi therapy for treating type 1 hyperoxaluria by targeting the HAO1 gene (encoding oxalate oxidase), thereby inhibiting oxalate production at its source[157]. Similarly, Nedosiran® (DCR-PHXC) is an RNAi therapy targeting lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). It functions as a GalNAc-dsRNA conjugate that suppresses LDH expression via RNAi technology, thereby reducing urinary oxalate production[158].

Apart from rare disorders, RNA therapeutics have also been applied to common hepatic and metabolic diseases. In 2013, Kynamro® (Mipomersen Sodium) was approved for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. This ASO drug inhibits apo B-100 protein synthesis through RNase H-mediated mRNA degradation, lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels[159]. Similarly, Leqvio® (Inclisiran) is an RNAi targeting PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) mRNA. By catalyzing the degradation of PCSK9 mRNA, the medicine increases hepatic LDL-C receptor recycling and expression and reduces circulating LDL-C levels[160]. Fazirsiran silences explicitly the expression of the mutant SERPINA1 mRNA and reduces the synthesis and accumulation of aberrant Z-AAT protein. In Phase I and II clinical trials, Fazirsiran showed remarkable efficacy, significantly decreasing hepatic Z-AAT deposition and improving biomarkers associated with liver inflammation and fibrosis[161−163]. mRNA-3927 is an mRNA-based therapy for propionic acidemia (PA), designed to encode two functional enzymes deficient in patients. Delivering the mRNA into cells can direct the synthesis of the corresponding enzyme proteins and restore metabolic function[164].

As the liver serves as the central hub for metabolic regulation, and is the most established organ for RNA therapy delivery, RNA therapeutics have ushered in a new era of precision medicine for liver diseases. The use of delivery techniques allows the therapy shift from 'efficient liver targeting' to 'precise cell-specific targeting', from 'chronic suppression' to 'functional cure', and from 'treating rare disorders' to 'conquering common diseases'. RNA-based interventions are becoming central to reversing—and potentially even curing—a broad spectrum of liver pathologies. Emerging targets in lipid metabolism, glucose regulation, and energy balance are gaining prominence as research focal points[165,166]. Moreover, combining RNA therapeutics targeting different pathways or integrating them with conventional drugs may represent a promising strategy to pursue curative treatment of liver-associated diseases.

Pulmonary diseases

-

RNA-based drugs for pulmonary diseases represent a rapidly emerging field, with current clinical-stage candidates mainly employing mRNA, siRNA, and ASO technologies. TPI ASM8 is an inhalable and mixed ASO agent for asthma treatment by simultaneously targeting CCR3 and the βc chain. Experimental results indicate that the administration could significantly mitigate allergen-induced late asthmatic responses[167,168]. The application of RNA therapeutics in pulmonary diseases represents a formidable challenge—one whose success hinges critically on breakthroughs in delivery technology. Although still in its early stages, this approach holds the promise of establishing a new treatment paradigm characterized by localized action, high efficiency, and programmable design.

Genetic diseases

-

RNA therapeutics for genetic disorders are among the most mature sectors within this technological domain. Patisiran, the first globally approved siRNA drug, is indicated for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR), while inotersen is an approved ASO-based therapy. Amyloid deposition decreases by silencing the mRNA expression of the TTR gene, or reducing the production of misfolded TTR protein[169−172]. Nusinersen, used for SMA, is also an ASO-based therapy that modulates the pre-mRNA splicing of the SMN2 gene to promote the production of full-length, functional SMN protein[173,174]. Eteplirsen, an ASO agent for specific mutation types of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), employs an 'exon-skipping' technique to skip exon 51 during DMD gene transcription, restoring the reading frame and resulting in a truncated but partially functional dystrophin protein[175,176]. Other relevant therapeutics for genetic disorders approved and in clinical trials are summarized in Table 1. RNA therapeutics have successfully transitioned from conceptual promise to clinical reality, reshaping the therapeutic landscape across multiple diseases. The therapeutics allow precise delivery of mRNA instructions or targeted degradation of pathogenic mRNA, demonstrating significant potential against major human disorders, including oncology, infectious diseases, genetic disorders, and hepatic and pulmonary conditions.

-

Due to the unique chemical/biological properties of different RNA molecules, RNA therapeutics have made significant advances in the treatment of diseases such as cancer, infectious diseases, liver disease, and lung disorders. However, various shortcomings, including poor cellular delivery, immunogenicity issues, poor stability, rapid clearance from the circulation, potential adverse effects, and challenges posed by complex in vivo biological barriers, significantly diminish the potential of RNA editing, markedly reducing the therapeutic efficacy of drugs. Therefore, extensive efforts have been devoted to overcoming these challenges, especially by optimizing delivery strategies/carriers to improve cell-targeted delivery efficiency and enhance RNA molecule stability. Various nanoparticle-based delivery strategies, including protein-RNA complexes, lipid carriers, and polymer carriers, have shown great promise in clinical evaluations and are being continuously optimized for efficient RNA delivery. Also, novel technologies such as AI, high-throughput RNA therapeutic screening, chemical modification, and RNA/single-cell sequencing methods further promote the optimization and validation of RNA therapeutics delivery. In addition, large-scale production, product consistency, and bioequivalence are important factors that limit widespread clinical translation. Manufacturers continually adapt to market demand by developing continuous production equipment, optimizing production processes, improving process quality monitoring and control, and ameliorating separation and purification methods. To date, over 40 carrier-based (LNP/Liposome) RNA therapeutics or structurally modified RNA molecules are currently undergoing different stages of clinical investigation. With further in-depth research into breakthroughs in drug-delivery strategies, more RNA-based products will be approved for disease treatment, offering more diversified clinical therapeutic approaches and providing potential for future precision or personalized medication.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: He W; writing—original draft: Zou J, He X, Li Z, Song B, Xing X, Yu J; review & editing: He W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82073782 and 82241002).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

#Authors contributed equally: Jiahui Zou, Xiaoke He, Zimin Li

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Pharmaceutical University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zou J, He X, Li Z, Song B, Xing X, et al. 2025. Harnessing RNA molecules for therapy: advances in design, delivery, and clinical development. Targetome 1(1): e005 doi: 10.48130/targetome-0025-0003

Harnessing RNA molecules for therapy: advances in design, delivery, and clinical development

- Received: 22 September 2025

- Revised: 02 November 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 19 November 2025

Abstract: RNA-based therapeutics have emerged as attractive candidates for clinical applications, offering distinct advantages over conventional small-molecule drugs, which play an important role in the treatment of a variety of diseases. Through specific and rational design, exogenous coding/noncoding RNA therapeutics, including messenger RNA (mRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), RNA aptamers, microRNA (miRNA), antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), short activating RNA (saRNA), RNA aptamers, circular RNA (circRNA), and CRISPR-based therapeutics are increasingly used to modulate the process of diseases at the genetic level. However, insufficient cellular delivery, RNA instability, and complex in vivo biological barriers significantly limit the therapeutic efficacy of RNA therapeutics. Numerous delivery strategies (e.g., nanotechnology, material-based carriers, and structural modification) have been used to overcome these key issues. In this review, the ongoing development and latest advances in RNA therapeutics are thoroughly summarized, focusing on therapeutic mechanisms, delivery challenges, and emerging drug delivery strategies. In particular, the clinical applications and current challenges in translating RNA therapeutics are discussed, highlighting future directions and opportunities to improve clinical efficacy.

-

Key words:

- Drug delivery /

- RNA therapeutics /

- Biological barriers /

- Clinical applications /

- Translation challenges