-

Maintaining thermal and metabolic homeostasis is fundamental to mammalian physiology[1]. Classical thermogenesis relies on uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1)-mediated proton leakage in brown and beige adipocytes, where mitochondrial energy is dissipated as heat during cold exposure[2,3]. The observation that Ucp1–/– mice are not obese, however, presents a physiological paradox that has led to the growing recognition of significant UCP1-independent contributions to systemic energy expenditure[4,5]. While mitochondrial thermogenesis via UCP1 is well-established, multiple UCP1-independent pathways exist, including futile lipid cycling, creatine phosphate cycling, and triglyceride-fatty acid cycling[6], which demonstrate the versatility of cellular energy dissipation[7]. Alternative cellular compartments, notably peroxisomes, can generate heat through substrate cycling and redox chemistry, but the biochemical identity and physiological relevance of these routes have only recently begun to be realized[8−10]. The study by Liu et al., published in Nature, positions a peroxisomal FASN-ACOX2 axis in adipocytes at the center of one such non-mitochondrial thermogenic program, prompting reconsideration of peroxisomes as active effectors of organismal energy balance[11].

-

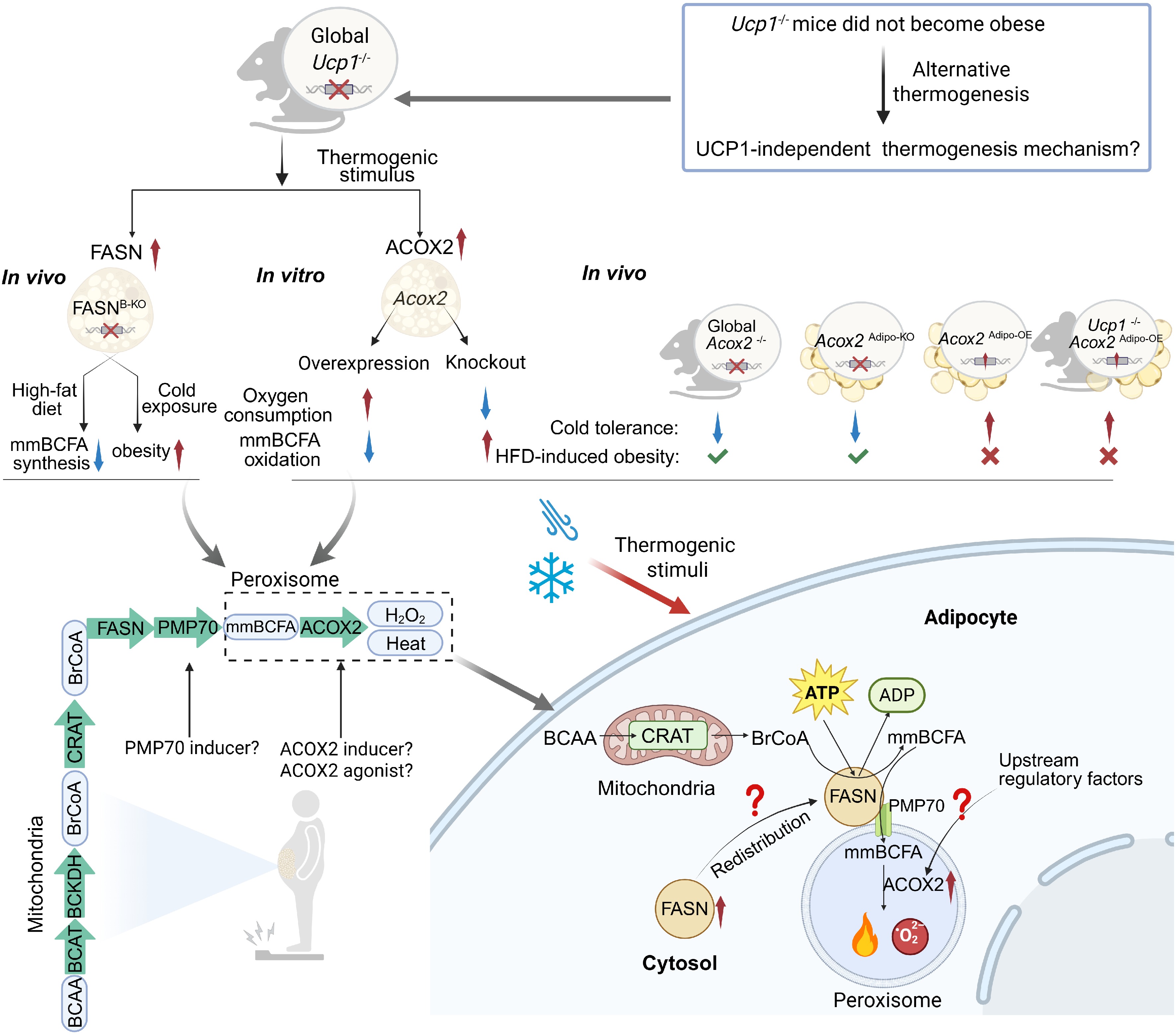

Liu et al., provide experimental evidence for an alternative, UCP1-independent thermogenic mechanism centered on peroxisomal enzymes that function to oxidize monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids (mmBCFAs)[11]. In contrast to the UCP1-dependent ATP-producing cycle[12], this study reveals a novel UCP1-independent thermogenesis process that is accomplished by an FASN-ACOX2 axis linking lipogenesis to peroxisomal β-oxidation, forming an ATP-consuming yet heat-producing substrate cycle[11]. Fatty acid synthase (FASN) converts branched-chain amino acid (BCAA)-derived intermediates into mmBCFAs, which are subsequently oxidized by acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (ACOX2)[11]. The synthesis and oxidation of mmBCFAs dissipate energy as heat, elevate oxygen consumption, and improve metabolic flexibility independent of UCP1 presence[11]. Manipulating this axis mitigates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, positioning peroxisomes as active regulators of adipose energy expenditure rather than passive lipid-processing organelles[11].

The adipocyte FASN-ACOX2 axis represents a novel heat-producing mechanism that first highlights the functional plasticity of FASN in metabolic regulation[11,13]. Traditionally regarded as a canonical lipogenic enzyme promoting energy storage, FASN exhibits remarkable adaptability in response to environmental cues[13]. Under cold exposure, FASN expression is highly induced and undergoes spatial reprogramming, redistributing from the cytosol to peroxisomes vicinity in adipocytes, where it promotes ACOX2-dependent oxidation of mmBCFAs[11]. This functional switch transforms FASN from a 'builder' of lipid stores into a 'regulator' of energy dissipation, highlighting the view that enzymes can be dynamically repurposed according to metabolic demand. Notably, the substrate preference of FASN is likely governed not only by organelle identity per se but also by local substrate availability and metabolic cues. Under thermogenic stimulation, peroxisomal BrCoA enrichment enables FASN to redistribute toward peroxisomal regions and utilize this conditional substrate for mmBCFA synthesis[11], whereas generally, cytosolic FASN mainly processes acetyl-CoA for conventional lipogenesis[13]. This highlights that metabolic context, rather than compartmentalization alone, dictates FASN's functional output[11,13].

Given that FASN is a large multifunctional enzyme complex (~250–280 kDa)[14], direct manipulation of its spatial localization remains challenging. However, the peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70) that may play a crucial role in this process[15] may be relatively easier to be regulated. Under cold exposure, FASN colocalizes with PMP70, which mediates the transport of mmBCFAs into peroxisomes[11]. Notably, several studies have reported inducing PMP70 expression or enhancing its transport activity[16], thereby potentially increasing peroxisomal import of mmBCFAs and promoting energy-dissipating oxidation. Although these mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, this concept expands the therapeutic landscape: targeting enzyme redistribution, so-called spatial pharmacology, could enable selective modulation of adipose thermogenesis without globally disturbing lipogenesis[17]. In this sense, the FASN-PMP70 axis exemplifies how subcellular compartmentalization can serve as an additional regulatory layer in energy metabolism.

As the peroxisomal executor of this thermogenesis cycle, ACOX2 catalyzes the initial oxidation step of mmBCFAs, thereby coupling substrate utilization with heat generation[11]. The highly localized expression of ACOX2 in peroxisomes of brown and beige adipocytes, and ACOX2 induction during cold exposure, underscore its pivotal role in non-mitochondrial adaptive thermogenesis[11]. Moreover, tissue specificity reflects a clear functional hierarchy: brown adipose tissue (BAT) shows the strongest induction of ACOX2 under cold exposure, inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT) exhibits moderate responsiveness, and gonadal white adipose tissue (gWAT) remains largely inert[11]. Such depot-dependent expression patterns underscore BAT as the primary executor of this UCP1-independent thermogenic pathway and provide a rationale for BAT-targeted interventions. Genetic ablation of ACOX2 either by global or adipocyte-specific ACOX2 knockout disrupts oxygen consumption and thermogenic competence, while adipose-specific overexpression restores thermal homeostasis independent of UCP1 presence[11]. These findings establish adipocyte ACOX2 as an indispensable node linking peroxisomal metabolism to systemic energy expenditure.

From a translational perspective, ACOX2 represents a potential metabolic target: enhancing its oxidation capacity could, in principle, increase energy dissipation and improve insulin sensitivity[11]. However, peroxisomal β-oxidation inherently generates hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct, raising concerns about oxidative stress and redox imbalance if chronically overactivated[18]. Moreover, given the established role of ACOX2 in bile acid metabolism, its activation may exert broader hepatic and systemic effects beyond thermogenesis[19]. Interestingly, comparison of the two knockout models, global ACOX2 deletion resulted in more pronounced metabolic disturbances than adipose-specific deletion[11], albeit these two experiments are not strictly designed and performed in parallel. Although both models exhibited comparable drops in core temperature during cold exposure indicating that adipose tissue is the primary site of ACOX2-mediated thermogenesis, the global knockout mice showed markedly greater weight gain, fat accumulation, and glucose dysregulation when fed a high-fat diet[11]. These findings suggest that ACOX2 expressed in extra-adipose tissues, such as the liver or muscle, plays a potential role in maintaining systemic metabolic balance rather than directly driving thermogenesis. Consequently, the development of future strategies should aim to balance therapeutic efficacy with considerations of redox and metabolic safety. Thermogenic stimuli can upregulate or activate the expression of numerous transcription factors, such as PGC-1α[20,21]. However, further research is needed to determine which factors cause the substantial upregulation of ACOX2 and FASN expression. Together, these insights position ACOX2 not merely as a metabolic enzyme but as a drug-modulatable switch in energy homeostasis, albeit the upstream modulators of ACOX2 induction in adipose remain to be identified.

-

Collectively, Liu et al. expand the functional spectrum of peroxisomes by unveiling a FASN-ACOX2-mediated substrate cycle that couples lipid synthesis with oxidation to generate heat in adipose and maintain cellular energy balance[11]. The dual functionality of FASN challenges the traditional view of lipogenesis and introduces enzyme redistribution as a new fine-tuned mechanism for thermogenesis[11,13]. ACOX2, in turn, emerges as an indispensable executor linking peroxisomal metabolism to systemic energy expenditure[11]. Nevertheless, current findings largely rely on murine models and remain unvalidated in humans, leaving the upstream cues that synchronize FASN redistribution and ACOX2 induction undefined[11]. Future studies should therefore aim to dissect the signaling mechanisms that coordinate FASN-ACOX2 induction under cold exposure, while also identify upstream regulators that govern ACOX2 expression and peroxisomal targeting. Furthermore, it will be essential to evaluate whether moderate, adipose tissue-specific activation of this pathway can be safely harnessed for metabolic therapy. Additionally, whether the adipocyte FASN-ACOX2 axis could be chemically or genetically targeted has not been examined in the current study; the translational value of the current findings remains a question. The role of the FASN-ACOX2 axis in cells beyond adipocytes also requires further investigation that could help clarify the specificity of targeting this adipose FASN-ACOX2 axis for treating obesity. Elucidating these mechanisms will not only refine the understanding of peroxisomal thermogenesis but also help clarify whether the FASN-ACOX2 axis or its upstream regulators could be therapeutically targeted to combat obesity and metabolic diseases. Future efforts aimed at selectively modulating the FASN-ACOX2 axis may complement existing mitochondrial thermogenic strategies, representing a distinct avenue for targeted anti-obesity therapy (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

FASN-ACOX2 axis regulates UCP1-independent peroxisomal thermogenesis. UCP1-deficient mice are resistant to obesity, revealing an UCP1-independent thermogenic pathway. Thermogenic stimuli upregulates FASN and ACOX2 in adiposes, triggering peroxisomal energy expenditure. In this pathway, mitochondrial CRAT converts BCAAs to BrCoA, which FASN uses to synthesize mmBCFAs. FASN is enriched around peroxisomes, where mmBCFAs are imported via PMP70 and metabolized by ACOX2, releasing heat. UCP1, uncoupling protein 1; ACOX2, acyl-CoA oxidase 2; BCAA, branched-chain amino acids; CRAT, carnitine acetyltransferase; BrCoA, branched-chain acyl-coenzyme A (CoA); FASN, fatty acid synthase; mmBCFA, monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids; KO, knockout; OE, overexpression.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception, manuscript revision and supervision: Yan T, Gonzalez FJ; draft manuscript preparation, figure creation: Xu X, Fang Y; critical revision and expert input: Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Note: figures were created with BioRender.com.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 82404732 and 82574484 to Tingting Yan) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20241592 to Tingting Yan). This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, CCR, CIL.

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest. We confirm that we have not received any financial support or sponsorship from any organization that could be perceived as influencing the results or interpretations presented in this work. The contributions of the NIH author(s) were made as part of their official duties as NIH federal employees, are in compliance with agency policy requirements, and are considered Works of the United States Government. However, the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

-

#Authors contributed equally: Xi Xu, Yannan Fang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Pharmaceutical University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu X, Fang Y, Zhang Y, Gonzalez FJ, Yan T. 2025. Targeting the peroxisomal FASN-ACOX2 axis to modulate energy homeostasis: therapeutic potential and challenges. Targetome 1(1): e006 doi: 10.48130/targetome-0025-0006

Targeting the peroxisomal FASN-ACOX2 axis to modulate energy homeostasis: therapeutic potential and challenges

- Received: 24 October 2025

- Revised: 11 November 2025

- Accepted: 13 November 2025

- Published online: 04 December 2025

Abstract: Peroxisomes are increasingly recognized as active contributors to cellular thermogenesis beyond their classical oxidative role. The Nature study by Liu et al. identifies a peroxisomal FASN-ACOX2 axis in adipocytes that mediates UCP1-independent heat production through cyclic synthesis and oxidation of monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids (mmBCFAs). In adipocytes, cold exposure induces the cytoplasmic enrichment of fatty acid synthase (FASN) adjacent to peroxisomes, where it provides substrates for acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (ACOX2)-dependent oxidation. The FASN spatial relocation may couple lipogenesis with energy dissipation, raising the possibility that enzyme subcellular distribution represents a way of fine-tuned metabolic regulation. Adipocyte ACOX2 acts as the peroxisomal executor of this UCP1-independent thermogenesis cycle and a potential metabolic target linking lipid flux to systemic energy expenditure. However, the metabolic role of the FASN-ACOX2 axis outside adipose tissue, and the upstream signals that coordinate FASN redistribution with ACOX2 induction, remain to be defined. Elucidating these mechanisms could ultimately inform novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating peroxisomal thermogenesis to treat obesity-associated metabolic disorders.

-

Key words:

- Peroxisomes /

- FASN-ACOX2 axis /

- UCP1-independent thermogenesis /

- Adipocyte /

- Obesity