-

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are a unique lymphoid lineage bridging innate and adaptive immunity, co-expressing surface markers characteristic of both natural killer (NK) cells and T cells. They are defined by a highly restricted semi-invariant T-cell receptor that confers stereospecific recognition of glycolipid antigens presented by the non-polymorphic MHC class I-like molecule CD1d[1]. Although largely confined to a minor fraction (approximately 0.01%–0.1%) of human peripheral blood lymphocytes, iNKT cells function as exceptionally potent immunomodulators, capable of orchestrating diverse immune responses.

A growing body of evidence has delineated the essential contribution of iNKT cells to host defense against bacterial and viral pathogens. Notably, these cells exhibit a functional duality in cell-mediated immunity: they can promote anti-tumor responses while also suppressing deleterious immunity in contexts such as autoimmune disease and allograft rejection[2]. This pivotal role is further underscored by the fact that iNKT deficiency increases susceptibility to both infections and cancer.

iNKT cells can effectively distinguish normal from abnormal cells, a critical capability that renders them attractive candidates for adoptive cellular therapy[3]. Their capacity to precisely identify and lyse target cells allows them to potently augment protective immunity[4]. Owing to the non-polymorphic nature of CD1d and the minimal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) risk, iNKT cells are emerging as promising candidates for allogeneic, off-the-shelf therapies, with significant applications emerging in Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and malignancies, as highlighted by recent work in Nature Communications[5] and Oncogene[6,7].

HTML

-

In the context of viral infections, a rapid decline in iNKT cell numbers, as observed in patients following HIV seroconversion[8]. Even with this reduction, these cells still play a regulatory role in airway hyper-reactivity. The CD1d-binding ligand, alpha-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), that activates iNKT cells also enhances immune responses in models of H1N1 influenza, viral encephalomyocarditis, and HIV vaccination[9]. Glycolipid-mediated iNKT stimulation and iNKT-based cell therapies are already under clinical investigation in oncology. The demonstrated antiviral efficacy of α-GalCer in clinical settings for chronic viral infections supports the therapeutic potential of adoptive iNKT cell therapy for acute viral conditions, such as SARS-CoV-2 infection[10].

An open-label phase 1/2 trial[5] demonstrated that agenT-797, an allogeneic off-the-shelf iNKT cell therapy, can resuscitate exhausted T cells and activate innate and adaptive immunity in patients with SARS-CoV-2-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The treatment was well-tolerated without dose-limiting toxicities (n = 21), and resulted in persistent iNKT cells that elicited merely transient donor-specific antibody responses, accompanied by an anti-inflammatory systemic cytokine profile. Notably, clinical signals included potential survival benefits and a reduction in secondary infections[5]. This study supports the safety and scalability of iNKT cell therapy, highlighting its broad therapeutic potential for infections[11].

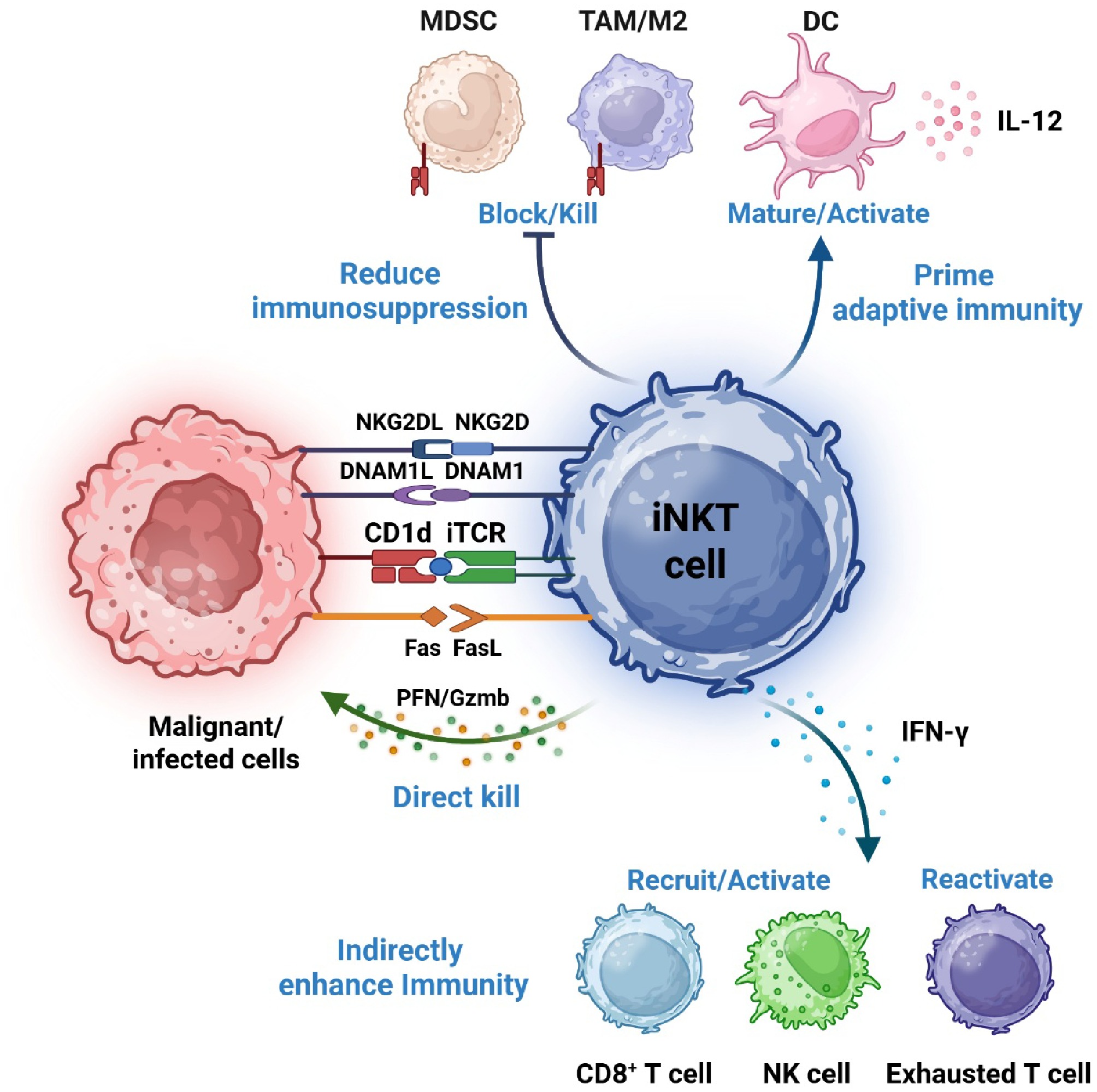

The mechanism of agenT-797 involves the reverse of T-cell exhaustion via soluble factors and activation of DCs, coupled with the preferential elimination of tumor- and infection-promoting M2 macrophages toward the M1 phenotype, thereby creating a theoretically hostile environment for both malignant and infected cells[5]. Post-infusion immunomonitoring revealed a corresponding anti-inflammatory shift, characterized by elevated IL-1RA and reduced levels of IL-7 and other pro-inflammatory mediators. These findings show mechanistic alignment with prior interaction data[12] and the documented myeloid-stimulating and T cell-rejuvenating effects of agenT-797[5] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of iNKT cell-mediated anti-viral and anti-cancer immunity. iNKT cells identify stressed and dying cells via T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated recognition of endogenous CD1d-presented lipid antigens, as well as engagement of NKG2D and DNAM-1 ligands. Upon activation, iNKT cells directly eliminate target cells and secrete abundant cytokines. These cytokines subsequently recruit and activate additional immune effectors, thereby intensifying anti-pathogen and anti-tumor responses. Additionally, iNKT cells can suppress immuno-regulatory myeloid cells, including macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), further bolstering immune activation.

-

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have advanced cancer treatment, tumor resistance leading to progression remains a common challenge. Notably, a striking response was observed in a treatment-refractory metastatic germ cell cancer patient who achieved complete and durable remission after a single infusion of iNKT cells (agenT-797) plus nivolumab. Strikingly, this response occurred in the absence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a frequent dose-limiting toxicity of cell therapies[6]. Further evidence for allogeneic iNKT cell therapy comes from a patient with relapsed/refractory gastric cancer refractory to standard therapies (FOLFOX and nivolumab). The administration of a single agenT-797 infusion resulted in a 42% tumor reduction and more than nine months of progression-free survival, accompanied by enhanced intratumoral immune infiltration[7].

iNKT cells exert tumor-suppressive activity via direct and indirect pathways[13]. iNKT cells mediate direct elimination of CD1d+ tumor cells via perforin/granzyme and FasL, and indirect immune enhancement via IFN-γ-mediated activation of NK and CD8+ T cells. This dual capacity enables iNKT cells to target both tumor cells and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) components like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)[14]. Furthermore, iNKT cells reshape the TME by engaging CD1d+ TAMs and MDSCs to reduce their inhibition[14], thereby promoting the infiltration and cytotoxic function of effector cells, such as NK and CD8 + T cells. The immunomodulation is amplified via reciprocal activation with dendritic cells (DCs): iNKT-derived signals promote DC maturation and IL-12 production, which in turn enhances the induction of tumor-specific adaptive immunity. Together, these integrated mechanisms establish a permissive niche for effective anti-tumor immune responses (Fig. 1).

-

iNKT cells possess significant advantages (Table 1), such as potent immunomodulatory functions and high tolerance, enabling the transformation of 'cold tumors' into 'hot tumors' and reversing resistance to immunotherapy. The inherent low alloreactive potential of natural iNKT cells positions them as a promising platform for developing 'off-the-shelf' allogeneic cell therapies. This advantage does not exclude further engineering. Instead, it provides a compatible and scalable cellular chassis that can be enhanced, for instance, through adding chimeric antigen receptors or other genetic modifications, to tailor potency and specificity for particular clinical indications. However, it is important to note the limitations. CD1d expression in solid tumors (positivity rate of 20%–50%) may trigger immune-related adverse events (irAEs). It is also very challenging to obtain large quantities of autologous iNKT cells from immunosuppressed cancer patients, and the culture and differentiation of these cells require several weeks.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of different cell therapies.

Cell therapies Target and mechanisms Advantages Disadvantages Applications CAR-T[15] Targeting tumor antigen with genetically engineered receptors, (MHC-independent) through scFv-CD3ζ. High target specificity, long-lasting efficacy, well-established manufacturing platform. Risk of Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS), tumorigenicity, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), graft-versus-host disease (GVHD, allogeneic), high cost and long production time. Hematological malignancies, particularly B cell malignancies and multiple myeloma. Mesenchymal cells[16] Direct migration towards diseased tissues through chemokine receptor and ligand, paracrine secretion, and immune modulation. Wide sources, modulating inflammatory effects, promoting tissue regeneration. Functional heterogeneity, difficulties in preparing quality-controlled cells in vitro, inconsistent response. Inflammatory and debilitating diseases. iNKT cells[17] Targeting CD1d-presented lipid antigens with invariant TCR, possessing both direct killing and immune re-orchestration. HLA-independent, durable responses due to memory function, safer toxicity profile (low GVHD risk, minimal CRS and negligible ICANS), potent activity with only one single dose and low costs. Limited number obtainable at their source, require specific manufacturing processes, limited targets. Allogeneic cell therapy for solid tumors, virus-associated diseases. NK cells[18,19] Non-specific cytotoxicity and recognition of NKG2DL on tumor. No need for antigen priming, good safety with low GVHD, CRS and ICANs. Low persistence in the absence of cytokine, subject to immunosuppressive barriers in the tumor microenvironment. Adoptive transfer of allogeneic NK cells for leukemia, lymphoma and solid tumors.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: visualization, software, funding acquisition, draft manuscript preparation: Wang X; writing – review & editing: Wang X, Jin J; resources, project administration: Zhang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82073948).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Pharmaceutical University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Wang X, Jin J, Zhang L. 2025. iNKT cells: an emerging promise for immunotherapy. Targetome 1(1): e010 doi: 10.48130/targetome-0025-0010 |