-

The velvet bean is a member of the Fabaceae family and commonly referred to as 'M. pruriens L. DC. var. utilis', is an annual climbing leguminous, green manure, legume, and land cover crop plant[1−4]. M. pruriens (L.) DC. grows wild in India[5−7] and thrives in tropical and subtropical regions of America, Africa, Asia, the Pacific Islands, and India[8−11]. It has 150 species worldwide, including 15 documented in India. M. pruriens is a medicinally valuable crop[12,13]. In India, two main species of M. pruriens (L.) DC. are commonly found: M. pruriens var. pruriens and M. pruriens var. utilis. M. pruriens var. pruriens, a wild variation with a black seed coat, has reddish-brown irritating trichomes on the pod that produce severe itching when in contact with the skin[14].

Human contact with Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. leads to itchy dermatitis attributed to mucuna production[15]. Due to this, farmers were hesitating mainly in terms of cultivation and toughness in harvesting this crop. The other varieties, like CIM-Ajar, CIM-Nirom (released by CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow), and Arka Shubra[13,14,16,17], possess non-irritating trichomes, and their distinctive velvety appearance is due to the dense silky trichomes, earning them the common name 'velvet beans'[12,18−20].

This study focused on M. pruriens (L.) DC., var. utilis, a commercially significant plant renowned for treating central nervous system disorders such as dementia, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's. Almost, all plant parts contain L-DOPA, with seeds having the highest quantity, followed by roots, stems, and leaves. Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC., var. utilis (variety: Arka Shubra, developed by ICAR-IIHR, Hessaraghatta Lake Post, Bengaluru) seeds exhibited notably high L-DOPA content (51.9 mg/g) and proline (1.74 mg/g), along with strong antioxidant activity (86.5%)[21]. This medicinally valuable crop is used for culinary purposes, with pods consumed as vegetables and leaves utilized as animal feed[22−24]. The characteristic pods bear fruits, and this plant has been studied in various studies[23,25,26].

L-DOPA, a valuable compound found in M. pruriens is in high demand globally, with the world market reaching 250 tons/year, costing USD

${\$} $ Spineless M. pruriens is a tropical leguminous plant that is celebrated for its versatility, serving as a cover crop, forage, traditional medicine source, and high-protein food[13,35−37]. Similar to other legumes like soybeans, common beans, and mung beans, velvet beans thrive in environments with ample moisture and warmth, both in cultivated and wild varieties[38−42]. To maximize its potential, understanding and optimizing the germination process are crucial. Seed treatments, including scarification and soaking, offer potential methods to enhance seed germination and, subsequently, crop establishment.

Thermo-hydro-priming, a method of soaking seeds in water to initiate germination without sprouting, has effectively enhanced germination rates and seedling vigor in various crops. This technique activates metabolic processes, improving germination rates and seedling growth. Chemical priming has also been shown to have positive effects on root development and seedling vigor[2]. It can significantly improve germination rates, with some studies indicating up to 88% germination when combined with mechanical treatments[40]. Seed priming enhances physiological traits, such as root and shoot length, and biochemical responses, contributing to improved crop establishment and yield. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of different seed priming treatments on germination rate and seedling establishment and determine the optimal seed priming treatment for improving germination dynamics and seedling establishment in Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis (Arka Shubra).

-

During 2022–2023, the experiment was conducted under Shade net Nursery conditions, at the CSIR-CIMAP RC, Experimental Farm in Hyderabad (17.25° N latitude and 78.33° E longitude). Spineless M. pruriens (L.) DC. Var. utilis, genotype/variety (Arka Shubra) seeds were used in this experiment, and it was designed in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with seven treatment combinations with three repetitions.

Seed collection

-

Seeds of spineless M. pruriens (L.) DC. Var., genotype/variety: Arka Shubra, were obtained from ICAR-IIHR, Hessaraghatta Lake Post, Bengaluru farm, ensuring genetic purity and viability. The study examined the influence of different seed treatments on seed germination, using the following methods:

Scarification

-

The Seeds were scarified by chemicals to break the seed coat.

Soaking

-

The Seeds were soaked in normal water (24 h) and hot water (80 °C) for 5 min.

Treatments

-

The following seed treatments were used in the experiment: T1 (control), T2 (hot water at 80 °C for 5 min), T3 (normal water for 24 h), T4 (H2SO4 1% for 5 min), T5 (KNO31% + HNO3 1% for 24 h), T6 (GA3 500 ppm for 24 h), and T7 (thiourea for 24 h). A total of 30 seeds for each treatment were subjected to their respective treatments and were sown in separate trays under controlled environmental conditions on June 10th, 2022, and June 22nd, 2023. In this experiment, we utilized sand, vermiculite, and paper towels as substrate. The seeds were exposed to normal daylight conditions, and the temperature was maintained within the range of 20−30 °C to facilitate optimal germination. Germination was monitored daily, and the percentage of germinated seeds was recorded.

Sampling and measurement

-

To obtain a complete picture of germination behavior, the following parameters were calculated using formulas and methodologies:

Germination (%) was calculated using the following formula[43]:

$ \mathrm{G}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\left[\dfrac{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{o}.\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\; \mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{T}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{\mathrm{l}\; no.}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}}\right]\times100 $ The mortality (%) was calculated using the following formula:

$ \mathrm{M}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{y}\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\left[\dfrac{\mathrm{No.}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\; \mathrm{u}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}+\mathrm{D}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{s}}{\mathrm{T}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{no.\; \mathrm{o}}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}}\right]\times100 $ The survival (%) was calculated using the following formula:

$ \mathrm{S}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\left[\dfrac{\mathrm{\mathrm{N}o.\; \mathrm{o}}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{h}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{y}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{s}}{\mathrm{T}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{no.\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}}\right]\times100 $ For survival (%) we use visual observations for healthy seedlings that typically exhibit vibrant green leaves, strong stems, and a well-developed root system. Signs of distress include yellowing leaves, wilting, stunted growth, or discoloration.

Days to germination were calculated as:

$ \mathrm{D}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{y}\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{t}\mathrm{o}\;\mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}=\mathrm{D}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{y}\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{t}\mathrm{o}\;\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\;\mathrm{e}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}-\mathrm{D}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{y}\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{t}\mathrm{o}\;\mathrm{f}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\;\mathrm{e}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e} $ Days to Initial Emergence refers to the number of days required for the first seedling to break through the soil surface after planting. In contrast, Days to Final Emergence indicates the total number of days for all seeds within a given treatment to emerge. Additionally, 'Days to Germination' is defined as the time from planting to the first emergence of a seedling, rather than the difference between initial and final emergence.

The speed of germination was calculated using the following formula[31]:

$ GS=\dfrac{\sum ni}{\sum di} $ Here, 'ni' is the number of germinated seeds, and 'di' is the total number of days.

The Vigor index was calculated by the following formula[32]:

$ \mathrm{V}\mathrm{I}=\dfrac{\mathrm{G}\mathrm{P}\times \mathrm{S}\mathrm{L}}{100} $ Here, 'GP' is the germination (%), and 'SL' is the seedling length.

Observations

-

The following seven attributes were recorded: ASL = average seedling length (cm); DFG = days for germination; Germ (%) = germination (%); Mort (%) = mortality (%); SDW = seedlings dry weight (g); SP = survival (%), and VI = Vigour Index.

Statistical analysis

-

The mean data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Ver. 19 software[44] for DMRT (Duncan's Multiple Range Test). Multivariate PCA was conducted using PAST Ver. 4.3 software to assess the impact of various treatments on the germination of M. Pruriens, and correlation analysis was employed to further investigate the relationships between the treatment variables and germination outcomes.

-

The germination (%) of spineless M. Pruriens exhibited notable variations under different treatments. H2SO4 treatment yielded the highest germination rate at 57.14% ± 2.49%, surpassing other treatments. Hot water treatment followed closely, with a germination rate of 44.25% ± 1.35%, comparable to the 42.86% ± 1.87% observed with normal water treatment. In contrast, the control group exhibited a significantly lower germination rate at 22.0% ± 0.96% compared to the rest of the treatments. This outcome suggests that applying H2SO4 positively influenced germination, outperforming both hot and normal water treatments. The efficacy of H2SO4 in enhancing germination may be attributed to its specific effects on seed coat permeability and the release of dormancy mechanisms[43,45−47]. The relatively high germination rates observed with hot water and normal water treatments also indicate their potential to promote seed germination.

The markedly lower germination rate in the control group underscores the importance of the applied treatments in optimizing germination conditions for spineless M. Pruriens (L.) DC. The obtained results are corroborated with the findings of Wanjekeche et al.[48] who found that Mucuna seeds treated in hot water recorded higher germination compared to the control. Similarly, the mortality percentages in spineless M. Pruriens varied significantly across treatments, with the control group recording a markedly higher mortality rate of 78% compared to the other groups.

In contrast, the H2SO4 treatment exhibited the lowest mortality rate at 42.86% ± 2.49%, followed by hot water treatment (55.75% ± 1.35%) and normal water treatment (57.14% ± 1.87%) (Table 1). This divergence in mortality rates highlights the potential impact of different treatments on the survival of Mucuna pruriens. The significantly higher mortality in the control group suggests that natural conditions or a lack of specific treatments may adversely affect seedling survival. Conversely, the lower mortality rates observed in the H2SO4, hot water, and normal water treated plants indicate their potential to enhance seedling survival.

Table 1. Thermo-hydro-chemical seed treatments and germination dynamics of Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis.

Treatments Germination (%) Mortality (%) SL (cm) Survival (%) DG SDW (g) T1: Control 22.00 + 0.96e 78.00 + 0.96a 8.89 + 0.39c 20.56 + 0.53f 14.26 + 0.38a 0.30 + 0.04f T2: Hot water 44.25 + 1.35b 55.75 + 1.35d 17.33 + 0.76b 43.94 + 1.16b 11.23 + 0.54d 0.68 + 0.05d T3: Normal water 42.86 + 1.87bc 57.14 + 1.87d 19.00 + 0.83a 39.42 + 1.04c 10.67 + 0.81f 0.74 + 0.03c T4: H2SO4 57.14 + 2.49a 42.86 + 2.49e 19.67 + 0.86a 56.98 + 1.73a 8.69 + 0.26g 0.90 + 0.04a T5: KNO3 + HNO3 28.94 + 1.26d 71.06 + 1.26bc 16.81 + 0.73b 27.42 + 0.87d 13.33 + 0.34b 0.36 + 0.08 T6: GA3 27.65 + 0.58d 72.35 + 0.58b 19.39 + 0.40a 26.89 + 0.92d 9.67 + 0.21e 0.82 + 0.02b T7: Thiourea 27.01 + 0.71d 72.99 + 0.71b 16.98 + 0.45b 26.05 + 0.54de 12.65 + 0.37c 0.50 + 0.04de SL, Seedling length (cm); SP, Survival (%); DG, Days to germination; SDW (g), Seedling dry weight; Average data followed by similar letter in the same column means not significantly different based on 5% of DMRT (Duncan's Multiple Range Test). Spineless Mucuna seeds commonly display both physical and physiological dormancy, hindering germination in a timely and uniform manner[49,50]. This dormancy is attributed to the impermeability of the seed coat and the presence of inhibitory substances within the seed. Sulfuric acid is recognized for its capacity to break seed dormancy via scarification, which entails weakening or thinning the seed coat[51]. The application of H2SO4 can effectively target the robust seed coat of Spineless Mucuna, promoting water absorption and facilitating the initiation of germination[34,51].

Enhanced germination observed in spineless Mucuna seeds following acid scarification with H2SO4 can be attributed to the alleviation of physical and physiological barriers that impede gaseous exchange and water uptake. This treatment likely facilitated improved imbibitions and respiration, which are critical for initiating metabolic processes and fostering early germination. Similar findings have been reported by Bhuse et al.[52] in Senna species, where acid scarification significantly improved germination rates by overcoming seed coat dormancy. The hard seed coat in Mucuna pruriens acts as a physical barrier to water and oxygen diffusion. H2SO4, a strong acid, chemically erodes the seed coat, creating micro-pores and cracks that enhance permeability. This mechanical breakdown allows for faster and more efficient imbibitions, which is essential for rehydrating seed tissues and activating metabolic processes.

Average seedling length (ASL) cm

-

The average seedling length of Spineless Mucuna exhibited notable variations under different treatments, with the application of H2SO4 resulting in a significantly higher seedling length of 19.67 ± 0.83 cm. This length was comparable to that observed after the application of GA3 (19.39 ± 0.40 cm) and normal water (19.0 ± 0.83 cm) (Table 1). In contrast, the control group exhibited a significantly shorter seedling length of 8.89 ± 0.39 cm.

These findings indicate that H2SO4 treatment not only positively influenced the seedling length of Spineless Mucuna but also outperformed the effects of both GA3 and normal water treatments. This suggests that H2SO4 may play a crucial role in promoting seedling growth, potentially by enhancing nutrient uptake and improving the physiological processes essential for growth. The effectiveness of H2SO4 in stimulating seedling development could be attributed to its ability to break seed dormancy and improve seed coat permeability, thereby facilitating better access to water and nutrients.

Conversely, the significantly reduced seedling length observed in the control group highlights the critical importance of external treatments in fostering the growth and development of Mucuna pruriens seedlings. The lack of any treatment in the control group likely resulted in suboptimal conditions for germination and early growth, underscoring the necessity of implementing effective pre-germination strategies to enhance seedling vigor.

These results are consistent with the findings of Fiallos et al.[53], who also reported the positive effects of various treatments on seedling growth in leguminous species. The implications of this study extend beyond the immediate effects on seedling length; they suggest that the application of treatments such as H2SO4 and GA3 can significantly improve the establishment and overall health of Spineless Mucuna seedlings.

Survival (%) (SP %)

-

The survival rates of spineless Mucuna seedlings following treatment with H2SO4 were significantly higher, reaching 56.98% ± 1.73%, in contrast to the remaining treatments. Subsequent in efficacy were hot water treatment (43.94% ± 1.16%) and normal water treatments (39.42% ± 1.04%) (Table 1). The control group exhibited a significantly lower survival rate of 20.56% ± 0.53% compared with the other treatments, with thiourea treatment following closely. The results highlight the remarkable impact of H2SO4 treatment on the survival of Spineless Mucuna seeds, surpassing the effects of both hot and normal water treatments. This underscores the potential utility of H2SO4 in enhancing seed viability and germination. The lower survival rate observed in the control group emphasizes the importance of specific treatments in fostering optimal conditions for seedling survival.

These findings underscore the significant positive impact of H2SO4 treatment on the survival of Spineless Mucuna seedlings, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing seed viability and promoting successful germination. The superior survival rate associated with H2SO4 treatment can be attributed to its role in breaking seed dormancy and improving seed coat permeability, which facilitates better water absorption and nutrient uptake. This treatment likely creates more favorable conditions for seedling establishment, leading to higher survival rates.

The notably lower survival rate observed in the control group emphasizes the critical need for specific treatments to foster optimal conditions for seedling survival. Without these interventions, seedlings may struggle to thrive because of factors such as physical dormancy and inadequate access to moisture and nutrients. This finding reinforces the idea that pre-germination treatments are essential for improving the establishment and growth of Mucuna pruriens seedlings.

Days for germination (DFG)

-

The germination period for spineless Mucuna seeds was significantly shorter under the treatment with H2SO4, requiring only 8.69 ± 0.26 days, compared with the other treatments. Following closely in efficiency was the GA3 treatment. Conversely, the control group exhibited a prolonged germination period of 14.26 ± 0.38 days and followed by KNO3 + HNO3 treatment (13.33 + 0.34 d) (Table 1). The notable reduction in germination days observed with H2SO4 treatment suggests its effectiveness in expediting the germination process of spineless Mucuna seeds. This finding indicates the potential utility of H2SO4 in optimizing germination conditions.

The implications of these results are particularly relevant for the cultivation of Mucuna pruriens, as faster germination can lead to earlier establishment of the crop and potentially higher yields. Previous studies have shown that treatments such as acid scarification can effectively reduce germination times in various leguminous species by overcoming physical dormancy and enhancing seed coat permeability[41]. Moreover, the prolonged germination periods observed in the control group and in the KNO3 + HNO3 treatment underscore the challenges posed by untreated seeds, which may struggle to germinate due to inherent dormancy mechanisms.

Vigour Index (VI)

-

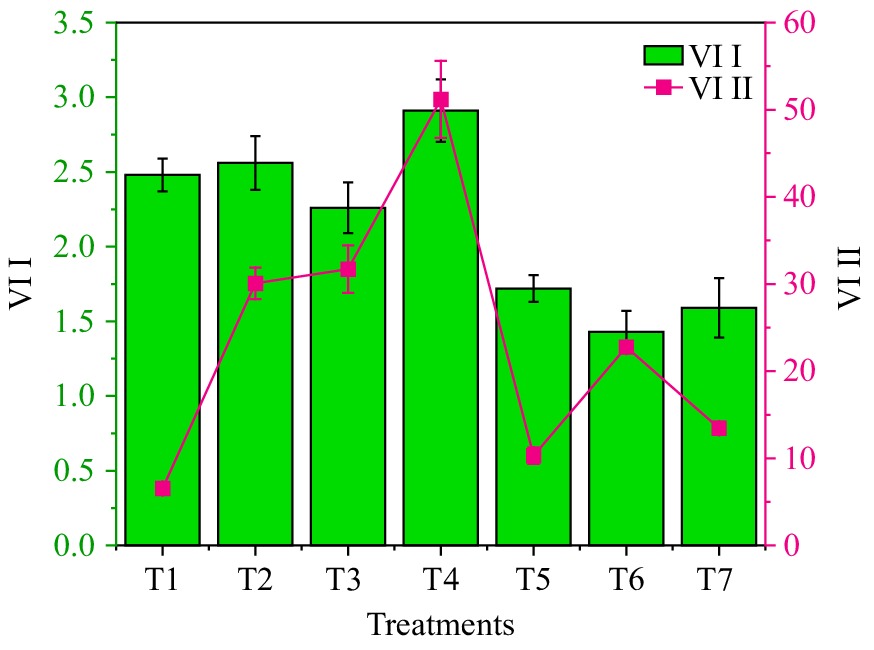

H2SO4 treatment resulted in significantly higher values for VI I and VI II, measuring 2.91 ± 0.21 and 51.18 ± 4.41, respectively, compared to all other treatments. The hot water treatment was closely followed, with values of 2.56 ± 0.18 and 30.08 ± 1.81 for VI I and VI II, respectively. Conversely, the control group exhibited significantly lower VI I (6.53 ± 0.41) compared to the other treatments, with the KNO3 ± HNO3 treatment recording the second-lowest values of 1.72 ± 0.09 and 10.30 ± 0.94 for VI I and VI II, respectively (Table 1 & Fig. 1). The substantial increase in VI I and VI II observed after H2SO4 treatment highlights its effectiveness in promoting these indices, suggesting a positive influence on the physiological and biochemical aspects of treated specimens. The hot water treatment also demonstrated notable effects, albeit to a lesser extent. In contrast, the control group exhibited significantly lower values, highlighting the importance of specific treatments in achieving favorable physiological responses (Figs 2, 3 & 4).

Figure 1.

Vigour index with the different treatments (error bars with standard deviation) in Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis). [T1 (control), T2 (hot water 80 °C for 5 min), T3 (normal water for 24 h), T4 (H2SO4 1% for 5 h), T5 (KNO3 1% + HNO3 1% for 24 h), T6 (GA3 500 ppm for 24 h), and T7 (thiourea for 24 h); ASL = Average seedling length; DFG = Days for germination; GP/Germ% = Germination (%); Mort% = Mortality (%); SDW= Seedling Dry Weight; SP/Sur% = Survival (%); VI I = Vigour index 1; VI II = Vigour Index 2].

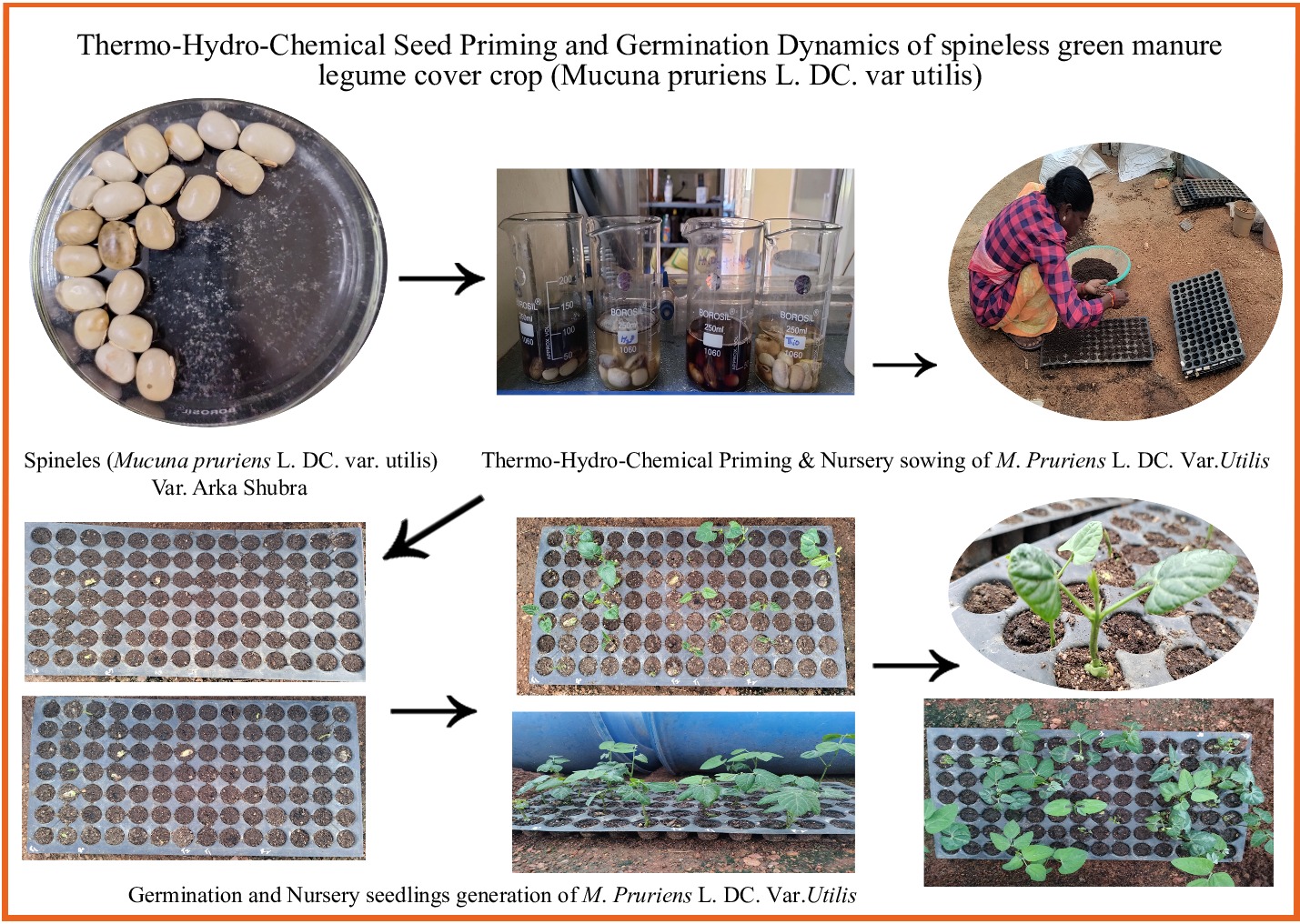

Figure 2.

Thermo-hydro-chemical seed priming and germination dynamics of spineless green manure legume cover crop (Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis).

Figure 3.

Seedling height of Mucuna pruriens in (a) (T4: H2SO4 1% for 5 min), and (b) (T2: hot water 80 °C for 5 min) thermo-hydro-chemical seed priming treatments.

Figure 4.

Trichomeless varieties of (a) CIM Ajar, (b) CIM-Nirom, and (c) wild collection with trichomes of Mucuna pruriens.

While the hot water treatment was also demonstrated beneficial effects on vigor indices, its impact was less pronounced than that of H2SO4. This suggests that while hot water can be an effective treatment for promoting germination and early growth, it may not be as potent as H2SO4 for optimizing physiological responses in Spineless Mucuna seedlings.

The significantly lower values observed in the control group highlight the critical role of specific treatments in achieving favorable physiological outcomes. Without these interventions, seedlings may experience suboptimal growth conditions, leading to reduced vigor and overall health.

Seedling dry weight (g) (SDW)

-

Applying H2SO4 resulted in a significantly higher seedling dry weight of 0.90 ± 0.04 g compared to all other treatments, with GA3 followed closely at 0.82 ± 0.02 g. Conversely, the control group exhibited a significantly lower seedling dry weight of 0.30 ± 0.04 g. The substantial increase in seedling dry weight under the H2SO4 treatment suggests its efficacy in promoting robust growth and biomass accumulation. The observed higher dry weight in the GA3 treatment further underscores the positive impact of specific treatments on seedling development. In contrast, the control group's significantly lower seedling dry weight emphasizes the importance of external factors in influencing plant growth. The markedly lower seedling dry weight in the control group underscores the critical importance of external factors, such as pre-germination treatments, in influencing plant growth. Without these interventions, seedlings may struggle to establish themselves, leading to reduced biomass and overall vigor. This finding aligns with the existing literature that emphasizes the necessity of employing effective treatments to optimize seedling growth and development[41,54].

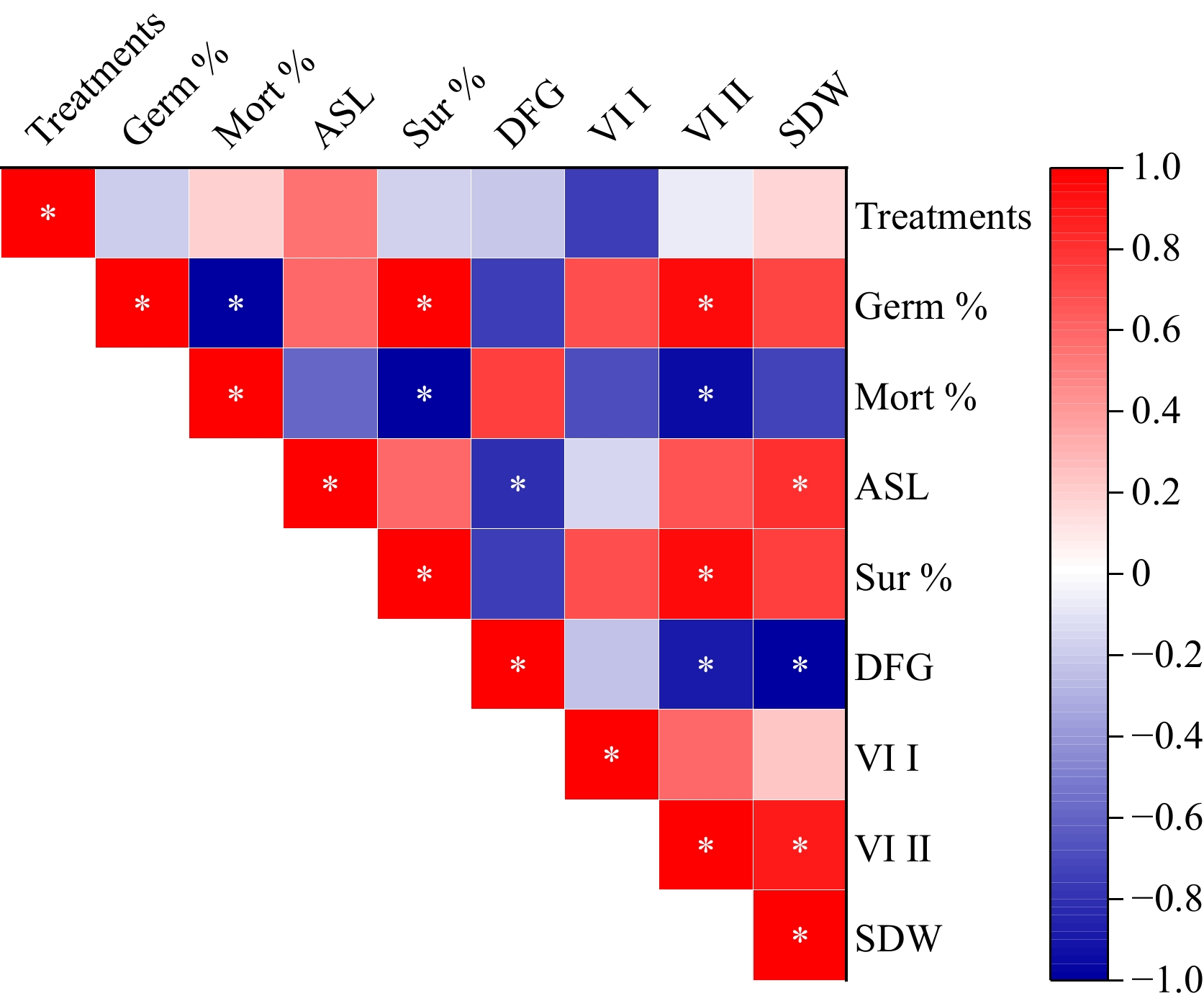

Correlation matrix and principal component analysis (PCA)

-

The correlation matrix provides insights into the degree of association between different variables. From the results, a strong positive correlation (r = 0.996) was observed between germination % and survival %, indicating that higher germination rates are strongly associated with better seedling survival. Similarly, a strong positive correlation (r = 0.956) was found between germination % and vigor index II, suggesting that seeds with higher germination rates tended to exhibit better overall vigor (Fig. 5). On the other hand, a strong negative correlation was observed between mortality % and germination % (r = −0.99), as well as between days to germination and seedling dry weight (r = −0.991). This implies that seeds that germinate faster tend to produce seedlings with higher dry weight, indicating that early germination is advantageous for seedling development. Additionally, negative correlations were noted between days to germination and vigor index (r = −0.896) and between seedling length and days to germination (r = −0.812) (Fig. 5). These findings highlight that early and high germination rates are critical for overall seedling success. Reducing the time to germination may enhance multiple seedling characteristics, and selecting for high germination percentages is likely to improve survival rates.

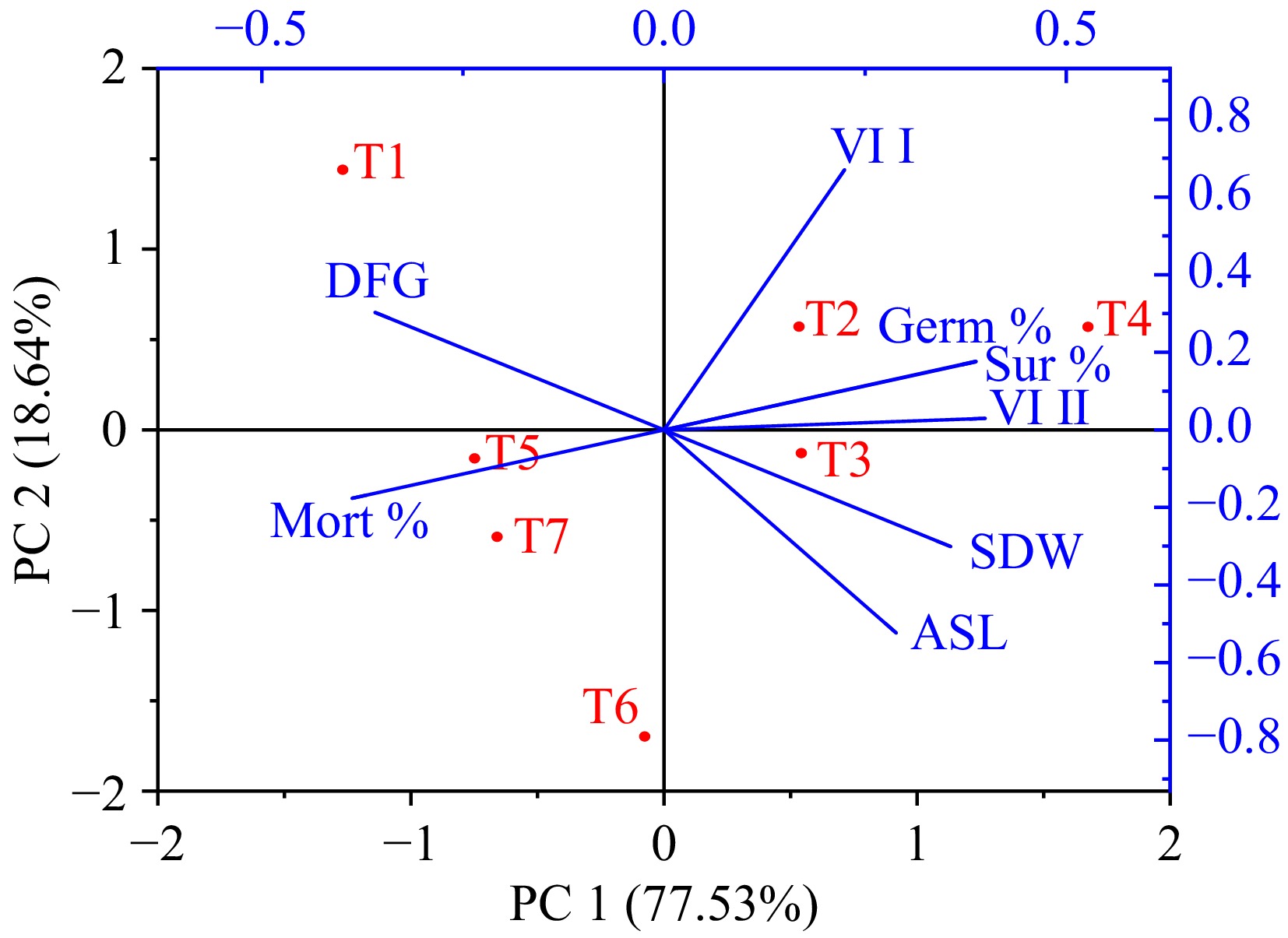

To assess the variability among treatment effects and germination characteristics, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed on eight parameters of M. pruriens. The resulting PCA plot (Fig. 6) revealed that the first two principal components (PC-1 and PC-2) collectively accounted for 96.17% of the total variation. PC-1 explained 77.53% of this variation, with positive contributions from VI I, VI II, Germination %, and Survival %, and negative contributions from ASL and SDW. PC-2 explained an additional 18.64% of the total variation, with a positive contribution from DFG and a negative contribution from mortality %. Notably, treatments T2 and T4 exhibited positive contributions, while the remaining treatments had negative contributions. Furthermore, the correlation matrix depicted significant correlations among various parameters. Germination % exhibited noteworthy correlations with VI 2 and survival (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) for treatments with germination-related traits in Mucuna pruriens [T1 (control), T2 (hot water 80 °C for 5 min), T3 (normal water for 24 h), T4 (H2SO4 1% for 5 h), T5 (KNO3 1% + HNO3 1% for 24 h), T6 (GA3 500 ppm for 24 h), and T7 (thiourea for 24 h); ASL = Average seedling length; DFG = Days for germination; GP/Germ% = Germination (%); Mort% = Mortality (%); SDW= Seedling Dry Weight; SP/Sur% = Survival (%); VI I = Vigour index 1; VI II = Vigour Index 2].

Table 2. Correlation analysis of germination related traits of Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis.

Characters G (%) M (%) SL (g) SP (%) DG VI I VI II SDW (g) G (%) 1 −0.99 0.596 0.996 −0.747 0.697 0.956 0.739 M (%) 1 −0.600 −0.996 0.746 −0.698 −0.957 −0.738 SL (g) 1 0.591 −0.812 −0.155 0.670 0.802 SP (%) 1 −0.754 0.698 0.958 0.742 DG 1 −0.228 −0.896 −0.991 VI I 1 0.593 0.231 VI II 1 0.887 SDW (g) 1 GP (%), Germination (%); Mort (%), Mortality (%); SP (%), Survival (%); DG, Days to germination; VI, Vigour Index; SL, Seedling length (cm); SDW (g), Seedling dry weight; Correlation is significant at 5%. -

The findings of this study underscore the significant impact of various seed treatments on the germination and growth characteristics of spineless M. pruriens. The application of H2SO4 emerged as the most effective treatment, leading to the highest germination percentage, reduced mortality rates, enhanced seedling length, and increased seedling dry weight. These results suggested that H2SO4 not only facilitates the breaking of seed dormancy but also promotes robust growth and biomass accumulation, thereby optimizing the conditions for seedling establishment. Hot water and normal water treatment also demonstrated positive effects, although to a lesser extent than H2SO4. The control group, which lacked any specific treatment, exhibited significantly lower germination rates and higher mortality, highlighting the critical role of targeted interventions in improving seedling survival and growth. Our results align with existing literature, reinforcing the notion that effective seed treatments can substantially enhance the physiological and biochemical responses of M. pruriens. Principal component analysis (PCA) further elucidated the relationships among various growth parameters, revealing that specific treatments positively influenced key indices such as vigor and survival rates. The significant correlations identified among germination percentage, seedling length, and survival rates emphasize the interconnectedness of these traits in determining overall seedling performance. The results of this study have implications for developing sustainable agriculture practices, particularly in regions where M. pruriens is a key crop.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jnanesha AC; analysis and interpretation of results: Venu Gopal S, Kumar A, Sravya K; draft manuscript preparation: Ranjith Kumar S, Bharath Kumar S; manuscript review and revision: Lal RK. All authors have reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors thank the Director, CSIR-Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Lucknow (U.P.), India for encouragement and support to experiment. CIMAP Publication No.: CIMAP/PUB/2023/167.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jnanesha AC, Ranjith Kumar S, Bharath Kumar S, Venu Gopal S, Sravya K, et al. 2025. Augmenting thermo-hydro-chemical seed priming and germination dynamics on genotype/cultivar-Arka Shubra: a spineless green manure legume cover crop Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis. Technology in Horticulture 5: e013 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0008

Augmenting thermo-hydro-chemical seed priming and germination dynamics on genotype/cultivar-Arka Shubra: a spineless green manure legume cover crop Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis

- Received: 19 August 2024

- Revised: 05 February 2025

- Accepted: 17 February 2025

- Published online: 02 April 2025

Abstract: The exploration of seed priming techniques represents a critical avenue for enhancing agricultural productivity, particularly in leguminous cover crops like Mucuna pruriens L. DC. var. utilis is commonly known as the velvet bean. This spineless green manure legume has significant potential for sustainable agricultural systems, offering multiple ecosystem services including soil fertility improvement, erosion control, and nitrogen fixation. Over 2022–2023, an experiment was conducted to evaluate the impact of diverse seed treatments on the germination dynamics and seedling growth of trichomeless (spineless) Mucuna pruriens. The experiment was designed in an RCBD with three replications, occurred under shaded conditions. Various treatments were applied, including scarification, soaking in hot and normal water, H2SO4, KNO3 + HNO3, GA3, and thiourea. The results indicated that H2SO4 treatment significantly enhanced the germination rate (57.14% ± 2.49%) and reduced the mortality rate (42.86% ± 2.49%) compared with the other treatments. Additionally, the H2SO4 treatment exhibited higher values for VI I (2.91 ± 0.21) and VI II (51.18 ± 4.41) than the other treatments. Furthermore, the application of H2SO4 resulted in a greater seedling drying weight (0.90 ± 0.04 g) in comparison to other treatments, with GA3 showing similar trend at 0.82 ± 0.02 g. The observed PCA plot indicates that PC-1 and PC-2 collectively explained 96.17% of the total variation. These findings highlight the effectiveness of H2SO4 in promoting favorable germination and seedling growth characteristics in spineless Mucuna pruriens.

-

Key words:

- Dormancy /

- Germination /

- Seed priming /

- Trichomeless /

- Vigour index