-

The coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L.), commonly referred to as the 'tree of life', is regarded as one of the most valuable and versatile palm species[1]. It is cultivated in more than 94 countries, predominantly in Asia, the Pacific Islands, and South America, covering an estimated 12 million hectares globally[2,3]. The coconut industry significantly influences the livelihoods and economies of tropical regions, serving as a primary income source for approximately 30 million farmers[4].

Additionally, over 60 million households depend on the coconut sector, either directly as farm workers or indirectly through activities such as distribution, marketing, and processing of coconut and its derivatives[5]. However, the global coconut industry faces several challenges, including stagnant production, limited availability of high-quality planting materials, climate change impacts, and the prevalence of pests and diseases[4]. Biotechnologies have emerged as an innovative solution and transformative tool in this regard, offering advanced in vitro technologies, particularly micropropagation tools that enable meeting the increasing demand for high-quality planting material within significantly shorter timeframes compared to conventional methods[5].

However, despite decades of effort on coconut micropropagation since the 1980s, an economically viable and practically reliable protocol has yet to be established[2]. This process involves several critical stages, including callogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, embryo maturation, germination, and the subsequent growth of clonal plants[6]. However, the growth of clonal plants has been observed to be notably slow both in vitro and during the early ex vitro phase. Plantlets cultivated in vitro are continuously exposed to a controlled, aseptic, and stress-free microenvironment, rendering them unable to tolerate ambient environmental conditions when directly transferred to a planthouse[7]. When compared to embryo-cultured plants, clonal plants, despite their prolonged in vitro duration, are smaller at the time of transplanting and require a longer period to reach the field-planting stage[8]. During this transition, plantlets undergo a metabolic shift from heterotrophic to autotrophic, which increases their susceptibility to external diseases and environmental factors[9].

Despite progress already made, the micropropagation of coconut continues to face obstacles, particularly the challenge of low rooting efficiency, which markedly affects the survival rates of regenerated plantlets. The employment of particular plant growth regulators (PGRs) is of cardinal significance for the genesis of roots and, consequently, for the success of the acclimatization phase[10]. The development of strong, healthy root systems is essential for withstanding acclimatization and the survival of plantlets under ex vitro conditions[11]. During the transition of coconut seedlings from in vitro to ex vitro conditions, the roots are particularly vulnerable to damage. These roots generally exhibit an underdeveloped vascular system, which plays a critical role in establishing a functional connection between the root system and the emerging foliage. This immaturity in vascular development can significantly hinder the effective acclimatization process[12].

Numerous studies have accelerated the rooting process in in vitro-cultivated coconut plantlets/seedlings by incorporating auxins into the culture medium. The use of synthetic auxins, such as Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), is widely recognized as a practice for promoting root induction in plant tissue culture[13−16]. These auxins stimulate cell division, elongation, and differentiation, which are essential processes for root formation. During the root induction process of plant tissue culture, IBA can effectively trigger the formation of adventitious roots, improving both the quantity and quality of the roots. 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), on the other hand, is capable of stimulating root growth, accelerating the rooting speed, enhancing root vitality, and facilitating the rooting development of tissue-cultured plantlets[17]. Pulse treatments, where tissues are exposed to high auxin concentrations for a short duration, have proven particularly effective in inducing rooting due to their targeted and transient action[17]. For coconut micropropagation, where rooting efficiency remains a major challenge, pulse treatments with IBA and NAA offer a promising result. These treatments influence the physiological and molecular pathways of root initiation and development, providing a targeted approach to improving rooting outcomes both in vitro and ex vitro and plantlet survival[18]. However, optimization of concentration and exposure duration is necessary to achieve the desired outcomes without compromising plantlet viability.

Thus, this study evaluates the effects of NAA and IAA pulse treatments on rooting in coconut clonal plants, focusing on the optimization of protocols for in vitro environments to facilitate early acclimatization. By exploring the role of pulse treatments, the research aims to overcome existing challenges in coconut clonal propagation, contributing to the development of reliable, efficient propagation systems for this economically important crop.

-

This study was mainly undertaken at the Tissue Culture Division of the Coconut Research Institute, Lunuwila, Sri Lanka (CRISL). Unfertilized ovary derived in vitro propagated shoots which were at an average height between 10−15 cm, 1−2 leaves, and no roots were selected as plant materials to maintain homogeneity. These shoots are clones of the coconut hybrid; variety CRIC 65, which is a cross between the Sri Lanka Green Dwarf and Sri Lanka Tall coconut from Bandirippuwa Estate, Lunuwila, Sri Lanka. The protocol employed for generating ovary-derived plantlets was based on the method described by Vidhanaarachchi et al., with minor modifications[19]. Unfertilized ovaries were harvested from female flowers at the −4 developmental stage, where maturity stages were defined as follows: the most recently opened inflorescence was denoted as stage 0, the next to open as stage −1, and the inflorescence set to open in four months as stage −4[20]. Female flowers were obtained from the basal portion of the rachilla, which was excised from the inflorescence and subjected to surface sterilization using 2% (v/v) Clorox (Unilever, Sri Lanka) solution (commercial bleaching solution containing 5.25% active chlorine) for 15 min. This was followed by five rinses with sterilized distilled water under aseptic conditions. Ovaries, approximately 2 mm in size, were dissected by carefully removing the outer perianth parts using a stereo binocular microscope (Zeiss Stemi DV4).

Production of plantlets in vitro for experiment

Callus initiation

-

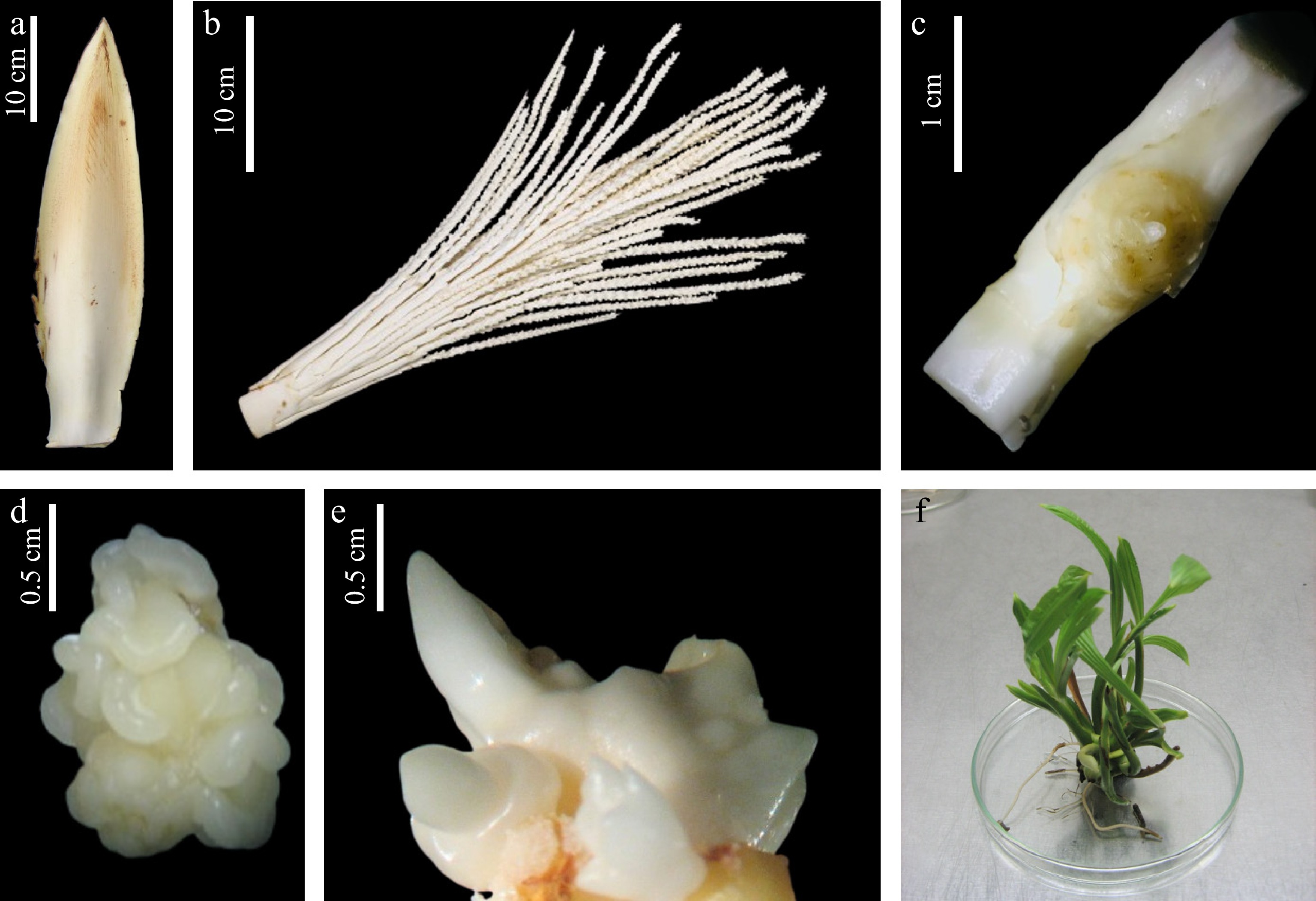

Firstly, dissected explants were cultured in 15 mL of standard callus induction medium Eeuwens Y3[21], supplemented with 160 μM 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (Sigma, Aldrich, USA), 0.1% (w/v) activated charcoal (Sigma, Aldrich, USA), and 4% sucrose (Sigma, Aldrich, USA)[19]. The medium was adjusted to pH 5.8 before solidification with 0.25% (w/v) phytagel (Sigma, Aldrich, USA). Cultures were maintained in complete darkness at 28 °C for 6−8 weeks without sub-culturing, as shown in Fig. 1. Primary callus (Fig. 1d), characterized by embryogenic (ear-shaped) structures, were dissected under a stereo binocular microscope (Zeiss Stemi DV4) and sub-cultured into callus induction medium for a first multiplication cycle. After 6 weeks, the embryogenic structures formed on the callus were isolated and transferred to the same medium for a second multiplication cycle (6 weeks), followed by a further cycle.

Figure 1.

Sequential stages in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) somatic embryogenesis and somatic embryo germination. (a) Immature inflorescence at −4 stage with spathe; (b) rachillae; (c) unfertilized ovary after removal of perianth parts; (d) embryogenic callus clump; (e) germinating somatic embryo structure; (f) shoot cluster induced from callus.

Shoot formation

-

Following three cycles, embryogenic structures (Fig. 1e & f) dissected from well-developed callus were subcultured into a somatic embryo induction medium (Eeuwens Y3 supplemented with 300 μM Benzyl amino purine (BAP) (Sigma, Aldrich, USA), 6 μM 2,4-D (Sigma, Aldrich, USA), and 0.5 μM gibberellic acid, (GA3) (Sigma, Aldrich, USA) for 4 weeks. Callus that exhibited shoots were directly transferred to a regeneration medium, comprising a modified Eeuwens Y3 medium supplemented with 20 μM BAP (Sigma, Aldrich, USA) and 0.5 μM GA3 (Sigma, Aldrich, USA). Embryonic nodules from the callus were subcultured onto somatic embryo induction medium for additional cycles until shoot initiation. Initiated shoots were then moved to regeneration medium (modified Eeuwens Y3 containing 20 μM BAP and 0,5 μM, GA3) to promote shoot formation. Once robust shoots started producing roots, the plantlets were transitioned to a modified Eeuwens Y3 liquid medium containing 4% sucrose (Sigma, Aldrich, USA) and maintained at 28 °C under a 16-h photoperiod (White LED fluorescence lights) (light intensity: 25 μmol·m−2·s−1) until ready for the experiment.

Treatments of PGRs on root development of in vitro developed coconut plantlets

-

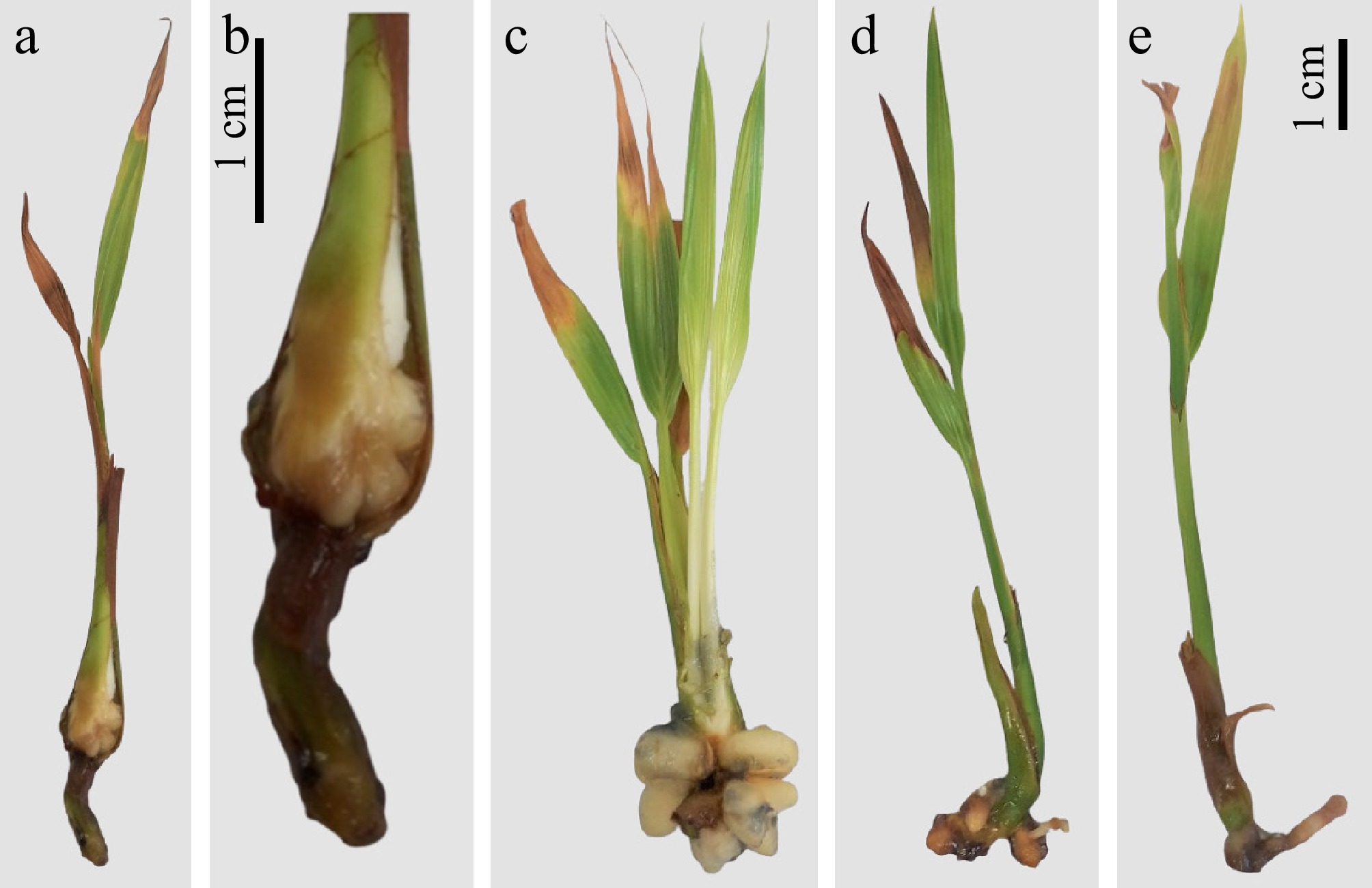

The effect of IBA and NAA on root development was evaluated by pulse treatment. Before treatment, the base of the shoot was cleaned by removing browned and necrotic tissues, followed by a gentle wash with sterile distilled water to eliminate debris. The cleaned shoot bases were then immersed in auxin solutions for 24 h. Three concentrations of both IBA and NAA (50, 125, and 200 μM) were tested, with 20 replicates in each treatment, as demonstrated in Table 1. Following auxin treatment, the plantlets were cultured in Modified Eeuwens medium (Y3)[21] supplemented with 4% (w/v) sucrose, 0.1% (w/v) activated charcoal, and 0.7% (w/v) agar. Cultures were maintained under controlled growth room conditions, with a 16-h photoperiod (White LED fluorescence lights) with 25 μmol·m−2·s−1 light intensity, and a temperature of 27 ± 1 °C. Subculturing was performed at six-week intervals, until the plants reached the acclimatization stage, as shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1. Treatments with plant growth regulators (PGRs) and their concentrations used in the experiment.

Treatment PGR type PGR concentration (μM) T1 NAA 50 T2 NAA 125 T3 NAA 200 T4 IBA 50 T5 IBA 125 T6 IBA 200 T7 (control) None 0

Figure 2.

Different shapes of bud in plantlets in vitro at the same developmental stage. All browning tissues were removed. (a), (b) Show the straight cut and no sign of root emergence, treatment needed to initiate root by using PGRs. (c), (d) Demonstrated a well-structured bud where primary root systems will start forming.

-

Therefore, this study aimed to induce primary root formation in coconut plantlets, thereby reducing the time required for root development while simultaneously enhancing the overall growth and development of the plants. By achieving these objectives, the in vitro duration could be significantly shortened. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), are two synthetic auxins known for their pivotal role in root development, were tested for their effects on key parameters, including the number and length of primary roots, as well as shoot elongation, leaf development, and plantlet weight, evaluated to optimize the in vitro conditions for an efficient tissue culture protocol.

Effect of NAA and IBA on root development

-

The results demonstrated in Table 2 highlight the effects of NAA and IBA on root parameters, including the number of primary and secondary roots, and their lengths at a significance level of 5%. The results indicate that NAA and IBA significantly influence root initiation and elongation of in vitro coconut clonal shoots at the basal part (Fig. 3a, b). Among the treatments, 200 μM NAA induced the highest average number of primary roots (3.55 ± 2.63), followed by 50 μM NAA (3.10 ± 2.94). However, in terms of root elongation, 125 μM IBA was the most effective, with the longest average primary root length (11.63 ± 8.73 mm) and secondary root length (7.72 ± 8.56 mm) (Fig. 3c, d, f). This result is also in agreement with the study by Balasuryia et al. [22], which demonstrates that NAA is more effective in promoting root initiation, while IBA excels in root elongation at optimal concentrations. In contrast, IBA at 50 μM and the control (0 μM auxin) showed the lowest numbers of primary roots and lengths, highlighting the necessity of exogenous auxin application for effective rooting. These findings are consistent with the well-established role of auxins in regulating root formation and elongation. Higher concentrations of IBA (200 μM), compared to 125 μM IBA, improved the average number of secondary roots (2.15 ± 3.20), but resulted in shorter primary roots (5.40 ± 6.81 mm), suggesting concentration-dependent effect that led to inhibition at higher levels, as shown in Fig. 4.

Table 2. Effect of NAA and IBA on in vitro root development of coconut plantlets.

Treatment (μM) Number of primary roots Length of primary roots (mm) Number of secondary roots Length of secondary roots (mm) NAA 50 3.10ab ± 2.94 10.04ab ± 7.97 0.75bc ± 1.44 1.10bc ± 2.57 NAA 125 2.55ab ± 1.88 6.79bcd ± 6.46 0.60bc ± 5.72 4.03b ± 0.00 NAA 200 3.55a ± 2.63 7.88abc ± 5.53 0.95bc ± 1.61 3.02bc ± 5.08 IBA 50 0.50d ± 0.70 0.40e ± 1.27 0.40bc ± 1.27 1.20bc ± 3.75 IBA 125 2.10bc ± 0.89 11.63a ± 8.73 1.45ab ± 1.67 7.72a ± 8.56 IBA 200 2.30abc ± 1.97 5.40cd ± 6.81 2.15a ± 3.20 2.60bc ± 3.97 Control 0.90cd ± 1.02 2.90de ± 3.82 0.00c ± 0.00 0.00c ± 0.00 Mean values followed by the same letter in a column are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. The best treatment was highlighted in bold.

Figure 3.

Primary root initiation and morphological differences of emerging primary roots in different auxin-type PGR treatments. (a), (b) Emerging of primary roots at the base of in vitro derived coconut plantlet. (c) Biomass/number of primary roots induced by NAA. (d) Biomass/number of primary roots induced by IBA. (e) Biomass/number of primary roots induced by without auxin treatment.

Figure 4.

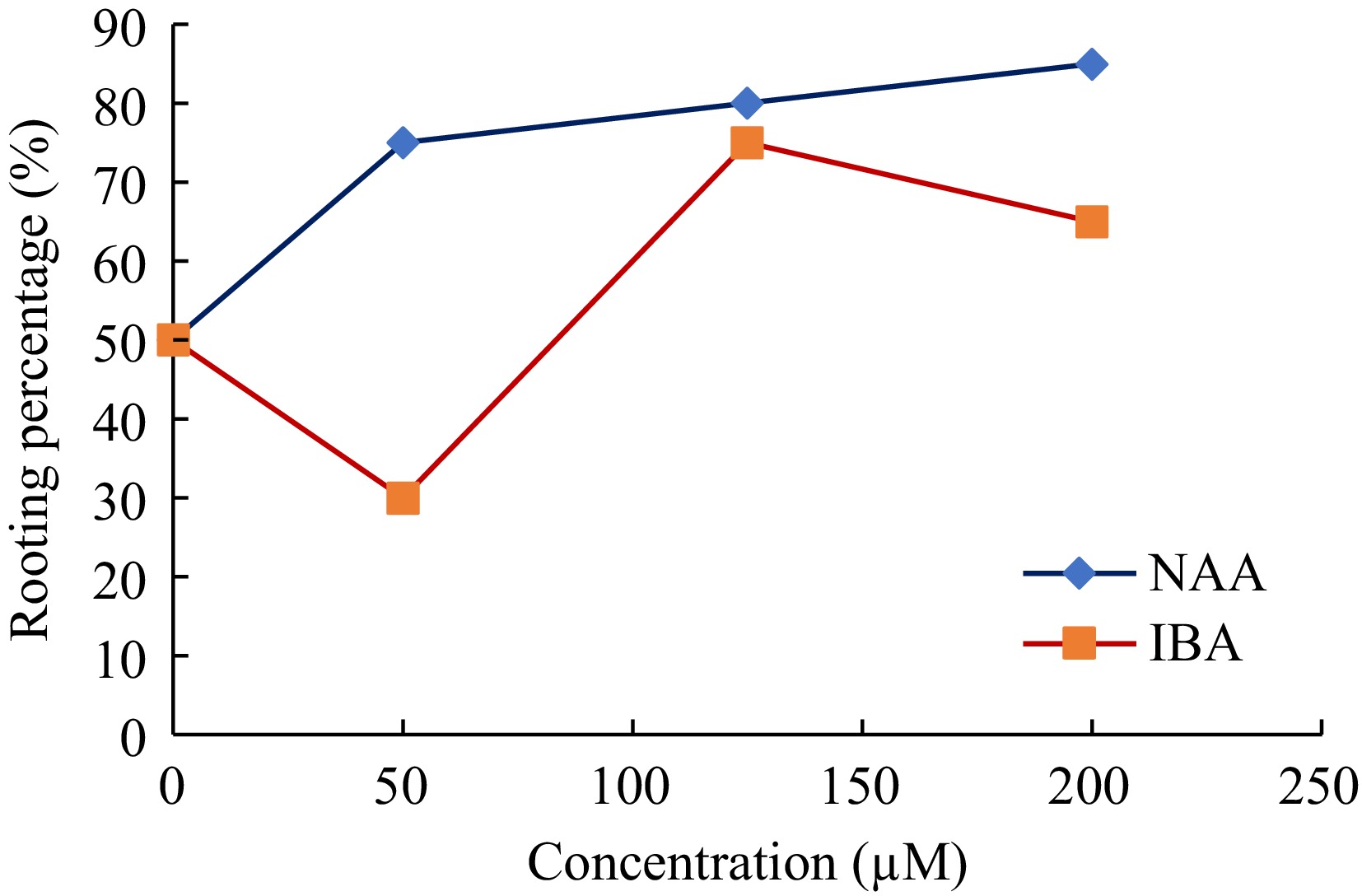

Comparison of rooting percentages at different concentrations (50, 125, and 200 μM) of IBA and NAA.

The enhanced root initiation observed in this study significantly reduces the acclimatization period of in vitro coconut plantlets by approximately three months compared to the traditional method. This improvement in early root establishment accelerates the transition to ex vitro conditions, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the propagation process.

The trend of rooting percentage (percentage of shoots that developed roots), as depicted in Fig. 4, reveals a clear distinction between the performance of NAA and IBA across the tested concentrations. NAA exhibited a consistent increase in rooting percentage with rising concentrations, reaching a maximum of 85% at 200 μM. This suggests that NAA is highly effective in promoting rooting at higher concentrations, likely due to its stability and prolonged activity in plant tissues. On the other hand, IBA demonstrated an optimal rooting percentage at 125 μM (approximately 70%), followed by a slight decline at 200 μM.

Effect of NAA and IBA on shoot development

-

The different concentrations of NAA and IBA inflicted significant effects on shoot development parameters; including shoot length, shoot weight, number of leaves, and girth of in vitro plantlets. As shown in Table 3, 125 μM IBA resulted in the highest shoot length (4.175 cm) and weight (1.70 g) among all treatments, outperforming other concentrations of both IBA and NAA. Furthermore, the control (0 μM auxin) also recorded a statistically significant value for shoot length (3.964 cm) but the lowest weight (0.34 g). The differences in shoot girth observed between NAA and IBA treatments highlight their distinct effects on plant growth. NAA at 200 μM resulted in the highest shoot girth (2.05 mm), demonstrating its effectiveness in promoting shoot robustness. Conversely, the decreasing trend in shoot girth with increasing concentrations of IBA, with the lowest girth observed at 200 μM (0.48 mm). Finally, the number of leaves, however, did not vary significantly across treatments, with all treatments producing approximately 1–1.5 leaves.

Table 3. Number of new leaves, shoot length, girth, and weight increment of in vitro coconut plantlets exposed to different auxin levels.

Treatment (μM) Shoot height increment (cm) Weight increment (g) Number of new leaves Girth increment (mm) NAA 50 1.421c ± 0.491 1.36ab ± 1.35 1.30a ± 0.10 1.70ab ± 1.78 NAA 125 2.594b ± 1.574 1.57ab ± 0.97 1.35a ± 1.27 1.72ab ± 1.28 NAA 200 1.467c ± 0.717 1.42ab ± 0.88 1.50a ± 0.69 2.05a ± 2.09 IBA 50 3.224ab ± 2.122 0.78cd ± 0.38 1.25a ± 1.25 0.98bc ± 0.96 IBA 125 4.175a ± 2.324 1.70a ± 0.93 1.45a ± 1.0 0.96bc ± 1.26 IBA 200 3.462ab ± 1.366 1.01bc ± 1.11 1.50a ± 0.83 0.48c ± 0.81 Control 3.964a ± 2.207 0.34d ± 0.25 0.75a ± 0.79 1.18bc ± 1.04 Mean values followed by the same letter in a column are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. The best treatments were highlighted in bold. -

Research on oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) demonstrated that IBA at lower concentrations (10 and 15 μM) significantly enhanced lateral root development, emphasizing its importance in promoting root architecture[23]. The response to IBA is slightly different in coconut, where moderate concentrations are most effective for rooting, while higher concentrations may have inhibitory effects[22]. This aligns with the findings of our study, where IBA treatments effectively improved root elongation and secondary root formation in coconut.

Apart from root formation, it was indicated that IBA at optimal concentrations promotes elongation and biomass accumulation in shoots, likely due to its role in enhancing cell division and elongation[24]. The comparison highlights the broader applicability of IBA across different palm species and the importance of concentration optimization for achieving balanced root and shoot development. This pattern can be attributed to the differential uptake and metabolism of IBA compared to NAA.

As suggested by Lee et al., our results also indicate that NAA is associated with shoot girth, showing its effectiveness in promoting shoot robustness[25]. This could be attributed to NAA's chemical stability and its role in enhancing localized cell division and expansion in the basal shoot region, contributing to thicker and sturdier shoots. NAA's consistent activity likely supports structural development, resulting in elevated girth[17]. Conversely, the decreasing trend in shoot girth with increasing concentrations of IBA, with the lowest girth observed at 200 μM, suggests that IBA, while effective for elongation and root induction, may not prioritize cell division in the shoot base at higher concentrations. Instead, higher IBA levels may promote vertical shoot elongation and biomass accumulation at the expense of girth, possibly due to reserve allocation favoring elongation over radial growth[24,26]. This indicates that while IBA is effective for stimulating certain aspects of shoot and root development, its role in enhancing shoot girth may be concentration-dependent, with higher levels potentially causing inhibitory effects on girth development.

Our findings also suggest that, in the absence of exogenous auxin, the shoot elongates as the plant distributes reserves predominantly toward vertical growth rather than biomass accumulation and balanced growth, including roots, leaves, and girth. This phenomenon is likely due to the plant's inherent hormonal balance, which may promote cell elongation but not necessarily the synthesis of additional cellular components needed for weight gain[27]. The significantly lower weight in the control group underscores the importance of exogenous auxin application in enhancing overall shoot growth by promoting both elongation and balanced growth with biomass accumulation.

The number of leaves indicates that auxin application, while effective for shoot elongation and weight gain, may not directly influence leaf initiation in coconut plantlets in vitro. Previous studies on embryo-cultured Dikiri coconut seedlings reveal notable differences in the average number of new leaves produced under similar NAA and IBA treatments[22]. For Dikiri seedlings, NAA treatments generally resulted in a higher number of new leaves, with the highest recorded at 1.25 (NAA 50 μM), while IBA treatments led to significantly fewer leaves, with averages ranging from 0.00 to 0.37. This contrast suggests that the physiological responses to exogenous auxins differ significantly between the two types of plants derived from different explants. The embryo-cultured Dikiri seedlings exhibit greater sensitivity to auxins, particularly IBA, resulting in lower leaf production compared to the more robust and uniform response of micropropagated plantlets of hybrid CRIC 65 coconut.

Strong, well-developed roots are essential for water and nutrient uptake, which are critical for plantlet survival under ex vitro conditions[18,28]. The higher rooting percentages observed with 200 μM NAA and 125 μM IBA suggest that these treatments could be applied to produce robust plantlets capable of surviving the transition to field conditions. However, the slower growth of tissue-cultured plantlets compared to embryo-cultured coconut plants (as noted in earlier studies) underscores the need for further refinements in culture media composition, in vitro environmental conditions, and plant growth regulator combinations to accelerate growth rates and reduce the overall duration and cost of the propagation process. Furthermore, it is known that plantlets from micropropagation and embryo culture differ[10]. In the future, a comprehensive comparison with plantlets derived from embryo culture should be conducted to ascertain the suitability of the materials obtained through the micropropagation route. It will be necessary to replicate this study with embryo-cultured seedlings, incorporating additional refinements.

Many factors influence the rooting of tissue-cultured coconut plantlets. For instance, PGRs (type, concentration, and combinations), basal medium components (inorganic salts, organic substances, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sugars, and vitamins), cultivation conditions (appropriate light, temperature, and humidity), genotype, source, and physiological state of the explants impact root formation. Future improvements in rooting efficiency can be achieved through multiple approaches: optimizing medium formulations with precise nutrient adjustments and exploring novel carbon sources; innovating the application of growth regulators by developing new compounds and constructing new release systems; enhancing cultivation conditions with smart control of light and temperature as well as improved sterile air circulation; and leveraging genetic engineering to identify rooting-related genes and applying omics technologies for support.

-

The differential responses of NAA and IBA treatments to root induction and shoot development provide important insights for improving micropropagation efficiency in coconut. NAA treatments, particularly 200 μM, are ideal for promoting root initiation, shoot robustness, and structural stability, making the plantlets suitable for early ex vitro establishment. Conversely, IBA at 125 μM, with its superior root elongation and weight gain effects, could be beneficial for ensuring efficient nutrient and water uptake during acclimatization. Additionally, the incorporation of other growth regulators or synergistic treatments, such as cytokinins or gibberellins, could be explored to enhance both shoot and root development.

This research was supported by the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (324QN360), the Technology and Innovation Project for Talent (KJRC2023L09), and the '111' Project (No. D20024). Immense gratitude is expressed to the technical and supporting staff of the Tissue Culture Division of the Coconut Research Institute of Sri Lanka, Lunuwila, Sri Lanka for their invaluable support.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study design: Indrachapa MTN, Vidhanaarachchi VRM, Mu Z; experiment operation: Indrachapa MTN, Balasuriya BMIK, Jayarathna SPNC; draft manuscript preparation: Indrachapa MTN, Jayarathna SPNC, Mu Z; manuscript review and editing: Vidhanaarachchi VRM, Mu Z. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Indrachapa MTN, Balasuriya BMIK, Jayarathna SPNC, Vidhanaarachchi VRM, Mu Z. 2025. Optimizing pulse treatments for enhanced in vitro rooting in coconut micropropagation. Technology in Horticulture 5: e027 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0019

Optimizing pulse treatments for enhanced in vitro rooting in coconut micropropagation

- Received: 13 January 2025

- Revised: 02 April 2025

- Accepted: 21 April 2025

- Published online: 09 July 2025

Abstract: Efficient in vitro rooting is critical for the successful micropropagation and early acclimatization of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.), a crop of immense agricultural and economic importance in the tropics. This study evaluated the effects of auxin pulse treatments using Indole-3-butyric Acid (IBA) and Naphthalene Acetic Acid (NAA) at concentrations of 50, 125, and 200 μM on the root induction and growth of unfertilized ovary derived clonal plantlets of coconut hybrid variety CRIC 65. Results revealed that 200 μM NAA significantly elevated shoot girth (2.05 mm), and shoot robustness. Conversely, IBA at 125 μM enhanced rooting performance, producing the highest primary root length (11.63 mm), and secondary root development (7.72 mm). Although the control (0 μM auxin) achieved the greatest shoot length (3.96 cm), it recorded the lowest weight (0.34 g), underscoring the necessity of exogenous auxins for balanced shoot and root growth. Higher concentrations of IBA and NAA promoted root initiation, while lower concentrations resulted in variable responses, with IBA favoring root elongation over girth and biomass accumulation. Furthermore, 200 and 50 μM NAA induced more roots (3.55 and 3.10, respectively, statistically non-significant) compared with the other treatments. The results emphasize the advantages of auxin optimization for improved root initiation, shoot development and overall plantlet development. This research contributes to refining micropropagation protocols for coconut, enhancing early root establishment, and reducing the acclimatization period by approximately three months compared to conventional methods, providing insights into auxin-mediated responses that enhance the efficiency and reliability of in vitro rooting, and field establishment of clonal plants.