-

Tea oil Camellia (Camellia oleifera) is an evergreen shrub in the Theaceae family[1], known for its high oil content and significant economic value. It is regarded as one of the world's four major woody oil crops, alongside Olea europaea L., Elaeis guineensis Jacq., and Cocos nucifera L.[2]. With a history of cultivation and utilization spanning more than 2,300 years in China[3], its primary cultivation areas are mainly located in southern China. However, its Hainan counterpart, C. hainanica, has emerged as a distinct species with unique morphological and genomic traits. Compared to C. oleifera, C. hainanica exhibits larger fruit size[4], decaploidy (vs hexaploidy in C. oleifera)[5], distinct chloroplast genome[6], and nuclear genome architecture[7], likely shaped by Hainan's tropical climate and geographic isolation. These factors have contributed to the distinct flavor and value of tea oil produced by C. hainanica[8].

Critically, C. hainanica demonstrates superior nutritional and economic potential. Its seed contains a higher oil content of 37.60%−41.60% (vs 31.04%−33.20% in C. sinensis), including elevated levels of oleic acid (79.62% vs 59.21%). Additionally, the contents of vitamin E (194.43 μg/g) and total phenols (345.73 μg/g)in C. hainanica oil were significantly higher than those in C. sinensis oil(3.00−17.42 μg/g,5.92−28.75 μg/g)[9]. These advantages, coupled with its adaptability to Hainan's high-temperature, high-humidity climate, underscore C. hainanica's potential to expand tea oil cultivation into tropical zones.

The phenology of plant flowering refers to the dynamic sequence of events, including flower or inflorescence blooming, anther dehiscence, pollination, and nectar secretion, under appropriate climatic conditions[10]. This process forms the basis for plant fruiting and crossbreeding. In this process, pollination, the transfer of mature pollen from the pollen sac of a plant to the stigma or near the micropyle via external forces, is a critical factor for fruit set and fertilization in seed plants[11], and the comprehensive characteristics of pollination are significantly related to flowering time[12,13]. Moreover, the viability and longevity of both pollen and stigma, as well as the role of pollination vectors, are central topics in pollination biology. Furthermore, the mating system, comprising floral characteristics, the longevity of sexual organs, the degree of self-compatibility, and the structure of the breeding system[14], plays a crucial role in shaping the morphological traits and evolutionary trajectories of plants, making it a key area of research. The outcrossing index (OCI)[15], the pollen-ovule (P/O) ratio[16], and bag pollination are commonly used methods to study plant mating systems and can also guide pollination and fruit set strategies.

C. oleifera is a cross-pollinated species characterized by distinct reproductive traits including autumn-winter flowering phenology, entomophilous pollination, and self-incompatibility[17]. Under natural pollination conditions, it exhibits an extremely low self-pollination fruit set rate of 3.26%[18]. This low fruit setting rate poses significant challenges to both yield optimization and large-scale cultivation of C. oleifera — a limitation also observed in its congener C. hainanica[19,20]. Assisted pollination technologies have demonstrated potential to mitigate low fruit set issues. In Juglans regia L., artificial pollination increased fruiting rates by 62.28%[21]. Similarly, manual cross-pollination between genetically distinct C. oleifera individuals nearly doubled fruit set rates[18]. However, effective implementation of such techniques requires systematic understanding of critical biological parameters, including flowering phenology, breeding system dynamics, pollen viability, and optimal pollen storage protocols[22−24]. While the flowering biology and breeding systems of C. oleifera cultivars have been extensively investigated[25,26], C. hainanica — a newly recognized species within the Camellia genus — remains understudied. Current research on C. hainanica has primarily focused on photosynthesis and foliar nutrient dynamics[27], and cultivation techniques such as grafting[28,29]. Notably, no comprehensive studies have addressed its flowering patterns, reproductive system characteristics, pollen viability thresholds, or pollen preservation methods. This knowledge gap severely impedes both agronomic management and targeted breeding programs for this species.

In this study, C. hainanica 'H4', a widely promoted variety in Hainan Province, was used as the experimental material to investigate its floral organ characteristics, pollen storage, and reproductive system. Various indicators, including floral organ morphology, pollen viability, and breeding systems, were measured and comprehensively analyzed to provide a theoretical foundation for artificial pollination, hybrid breeding, and variety allocation of C. hainanica 'H4'. This research not only aids in understanding flowering patterns to increase yields but also assists in selecting superior hybrid parents of C. hainanica 'H4'. The results offer valuable guidance for the selection and breeding of new varieties, varietal improvement, and the formulation of variety allocation strategies for C. hainanica.

-

The experimental orchard is located in Yongbian Village, Fushan Town, Chengmai County, Hainan Province, China (19°90′34″ N, 109°90′23″ E). The average annual temperature is 23.7 °C, with 2,060.5 h of sunshine, an annual average rainfall of 1,756 mm, and an annual average relative humidity of 84%. The orchard is situated on a flat terrain with fertile red soil. The experimental material consisted of 9-year-old 'H4' cultivar plants, exhibiting healthy growth and free from pests and diseases. The planting arrangement had an average row spacing of 3.0 m × 4.0 m, with a density of approximately 750 plants per hectare. All experimental plants were managed uniformly under the same conditions.

Observation of flowering dynamics and floral organ structure

-

The flowering period of 'H4' was investigated from September 2023 to March 2024. The number of flowering individuals was recorded daily. Based on the observed flowering numbers, anthesis was categorized into three distinct periods: the initial bloom period (≤ 25% of the total flowering individuals), the full bloom period (≥ 50% and ≤ 95% of the total flowering individuals), and the final bloom period (≥ 95% of the total flowering individuals). During the full bloom period in November 2023, the dynamics of flower opening in individual blooms were observed in the field. This study selected three groups (10 plants/group) of healthy and mature 'H4' plant varieties. Flowers at the large bud stage were marked for identification from all four cardinal directions on each plant. For the first 1–2 d of blooming, observations were made and recorded every 2 h. Subsequently, observations were made daily at 12:00 PM until the flowers withered.

A total of 20 flowers were randomly selected, and the number of petals, stigma cracks, and stamens were counted. The ovaries were dissected to determine the number of ovules, and the anther color and phenotype were recorded. A vernier caliper was used to measure the width of the corolla, the length and width of the petals, the diameter of the androecium, the length of the style, and the length of the filaments.

Determination of pollen grain number, pollen viability, and stigma receptivity

-

For this experiment, 20 flowers at the bud stage were randomly selected from 10 healthy plants, and all anthers were mixed. Thirty intact, uncracked anthers were randomly selected and divided equally into three groups, with 10 anthers in each group as three replicates. They were then incubated in a 25 °C oven until the anthers fully released their pollen. Subsequently, 1 mL of a 1% cellulase solution was added to each tube. The tubes were shaken thoroughly on a shaker for 24 h to ensure the pollen grains fully mixed with the solution. A 3 μL aliquot of the extract was pipetted and observed under a microscope. The pollen count was determined using the method described by Yuan et al.[30]. The formula for calculating the pollen count is as follows:

$ {\rm Amount\;of\;pollen\;per\;anther = \dfrac{Total\;no.\;of\;pollen\;grains\;per\;slide \times 1000}{30}} $ $ \mathrm{\begin{aligned} & \rm{A}mount\; of\; pollen\; per\; flower=Pollen\ vol.\ of\ a\ sigle\ anther\times No.\ of\ anthers\end{aligned}} $ Pollen viability was assessed using TTC (2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride) staining. Anthers from 10 flower buds were randomly collected, and one anther was placed on a microscope slide and crushed thoroughly to release the pollen. A suitable amount of pollen was then mixed with a 5% TTC solution. The slides were incubated at 35 °C for 15 to 20 min. Pollen viability (PV) was assessed using a microscope, and the viability percentage was calculated according to the following formula:

$ \rm{P}ollen\; viability\; (\text{%})=\dfrac{No.\; of\; stained\; pollen\; grains}{Total\; no.\; of\; observed\; pollen\; grains}\times100\text{%} $ An in vitro pollen germination test was conducted on a medium optimized by Yuan et al.[30], consisting of 1% agar, 10% sucrose, and 0.01% boric acid, at a temperature of 25 °C and an illumination intensity of 10,000 lux[31]. The germination status of the pollen was observed and recorded at 1, 3, and 5 h intervals. The criterion for pollen germination was defined as the length of the pollen tube exceeding half the diameter of the pollen grain. Pollen grains that did not germinate after 5 h were considered non-germinative.

$ \mathrm{P}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\; \mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\; \mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{o.}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{g}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\; \mathrm{p}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\; \mathrm{g}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{s}}{\mathrm{T}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{no.\; \mathrm{o}}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{p}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{g}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{s}}\times100\text{%} $ Stigma receptivity was assessed using the benzidine-hydrogen peroxide method. Stigmas were collected from the pre-anthesis stages of small buds, large buds, initial blooms, and final blooms. The stigmas were placed on concave slides, and 2−3 drops of benzidine-hydrogen peroxide reaction solution (1% benzidine : 3% hydrogen peroxide : water = 4:11:22) were added to fully submerge the stigmas. After 5 min, the stigmas were observed and photographed under an OLYMPUS SZX10 stereo microscope. The intensity of stigma receptivity was evaluated based on the number of bubbles produced around the stigma. A high degree of stigma receptivity was indicated by a large number of bubbles formed around the stigma, whereas a low degree of stigma receptivity was characterized by fewer bubbles[32].

Pollen storage

-

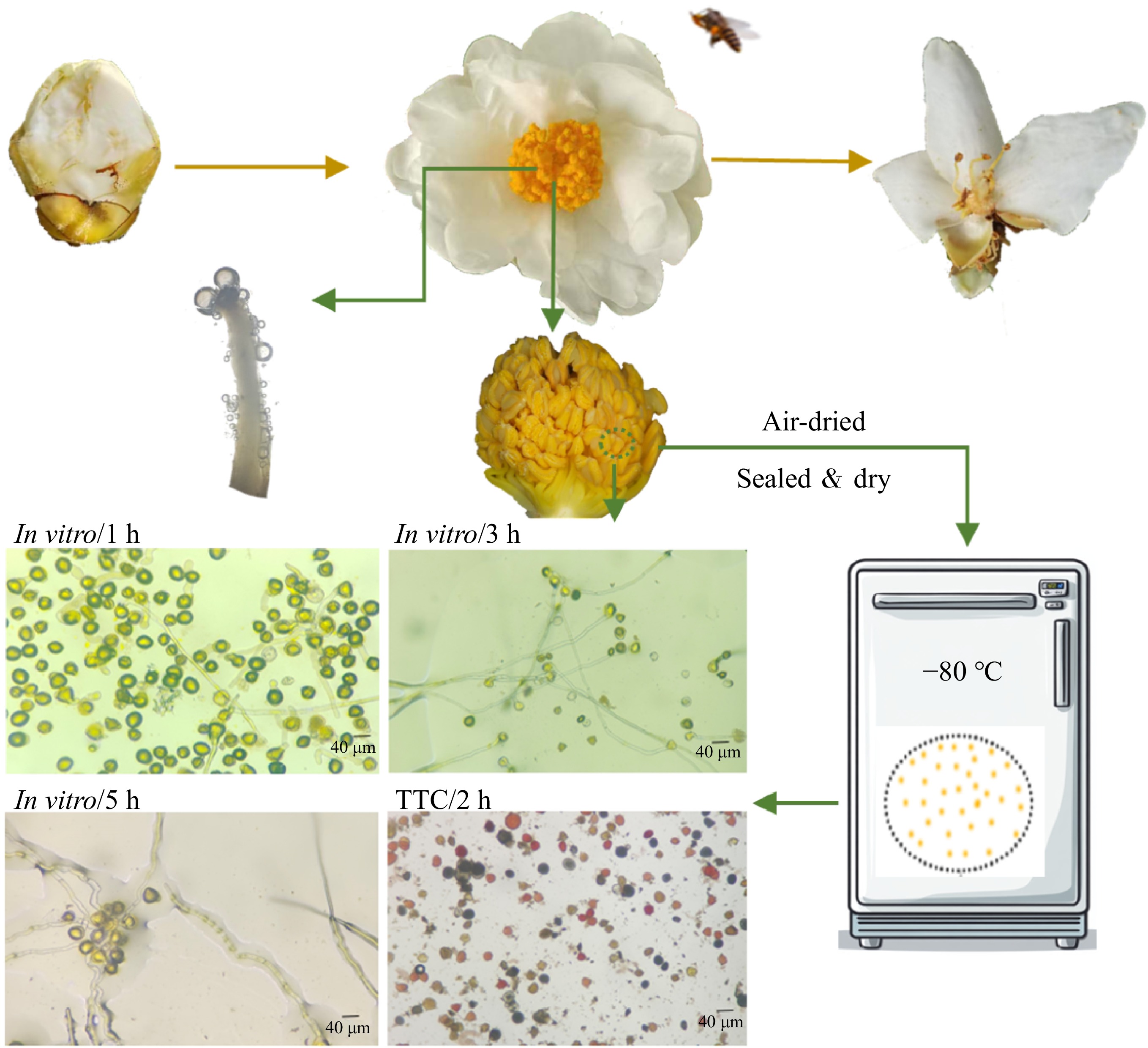

Three key factors affecting the pollen viability during storage temperature (25, 4, −20, −80 °C), method (sealed, sealed & dry) and pollen state (fresh, dried) were evaluated to optimize the best storage condition using for the future artificial pollination. In this experiment, 'sealed' indicates that the pollen was stored in 2 mL microcentrifuge tube, whereas 'sealed & dry' denotes pollen stored in 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes and further placed in a sealed bag containing 25 g of solid CaCl2 as a desiccant. Fresh pollen refers to pollen collected directly from flowers, while dried pollen refers to pollen dried at room temperature (RT) for 12 h before storage. The experimental design followed an L8 (4 × 24) mixed orthogonal array, as detailed in Table 1[33,34]. Pollen samples were cultured under uniform conditions on an in vitro germination medium described previously. Pollen germination rates were subsequently measured at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 d under varying storage conditions.

Table 1. Orthogonal experimental design of C. hainanica pollen storage.

Treatment Temperature (°C) Mode Pollen state T1 RT Sealed Fresh T2 RT Sealed & dry Dried T3 4 Sealed Dried T4 4 Sealed & dry Fresh T5 −20 Sealed Dried T6 −20 Sealed & dry Fresh T7 −80 Sealed Fresh T8 −80 Sealed & dry Dried Measurement of the breeding system

-

The observation of flower-visiting insects commenced on November 29, 2023, coinciding with the peak flowering period of C. hainanica. From 7:00 to 17:00 every day, five blooming flowers were observed continuously for 18 d to record the activity of flower-visiting insects.

We collected 20 flowers of 'H4' at full bloom, dissected the ovaries using a scalpel, and observed them under a stereo microscope to count the ovules in each ovary, calculating the number of ovules per ovary. According to Cruden[16], the pollen-ovule (P/O) ratio was evaluated and calculated, a P/O ratio of 2.7–5.4 is defined as cleistogamy pollination, 18.1–39.0 corresponds to obligate selfing, 31.9–396.0 as facultative selfing, 244.7–2,588.0 as facultative outcrossing, and 2,108.0–195,525.0 as obligate outcrossing.

The outcrossing index (OCI) was calculated according to the method described by Dafni[15] as follows: (1) Flower diameter: < 1 mm scored as 0, 1–2 mm as 1, 2–6 mm as 2, and > 6 mm as 3. (2) Maturation synchrony: If anther dehiscence coincided with stigma receptivity or pistil maturation preceded stamen maturation, a score of 0 was assigned; if stamen maturation preceded pistil maturation, the score was 1. (3) Stigma-anther spatial separation: If the stigma and anther were at the same height, the score was 0; if spatially separated, the score was 1. The OCI was suggested by summing the scores from these criteria. The breeding system was then classified as following: OCI = 0 represents cleistogamy (obligate self-pollination); OCI = 2 indicates facultative self-pollination; OCI = 3 suggests self-compatibility but with occasional pollinator requirements; OCI ≥ 4 signifies partial self-compatibility, cross-fertilization, and dependency on pollinators.

Artificial-assisted pollination experiment

-

Before flowering, 30 flowers were selected for each pollination treatment and individually enclosed using tracing paper bags. The pollination treatments were as follows: (1) natural pollination: neither emasculation nor bagging; (2) self-pollination: bagged with tracing paper bags before anthesis to prevent external pollen transfer; (3) natural cross-pollination: emasculated at the bud stage, not bagged; (4) geitonogamy: flowers were emasculated at the bud stage, pollinated with pollen from flowers on different plants, and then bagged; (5) xenogamy: emasculated at the bud stage, pollinated with pollen from different varieties of the same species, and bagged; (6) emasculation without pollination: emasculated at the bud stage and bagged. Emasculation is the process of removing the stamens (male reproductive parts) from a plant flower using tweezers to prevent self-pollination or to control cross-pollination.

The fruit set rate was calculated 90 d after pollination using the following formula:

$ \mathrm{F}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}\; \mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\; \left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{o.}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{f}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{s}}{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{o.}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{f}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{w}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{s}\; \mathrm{p}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}}\times100\text{%} $ Data analysis

-

Data organization and statistical analysis were performed using Excel (2024) and GraphPad Prism 9, while graphs were generated in the same software. One-way ANOVA was conducted to analyze pollen and fruit set data using SPSS 25.0. Image processing and enhancement were carried out using Photoshop 2023.

-

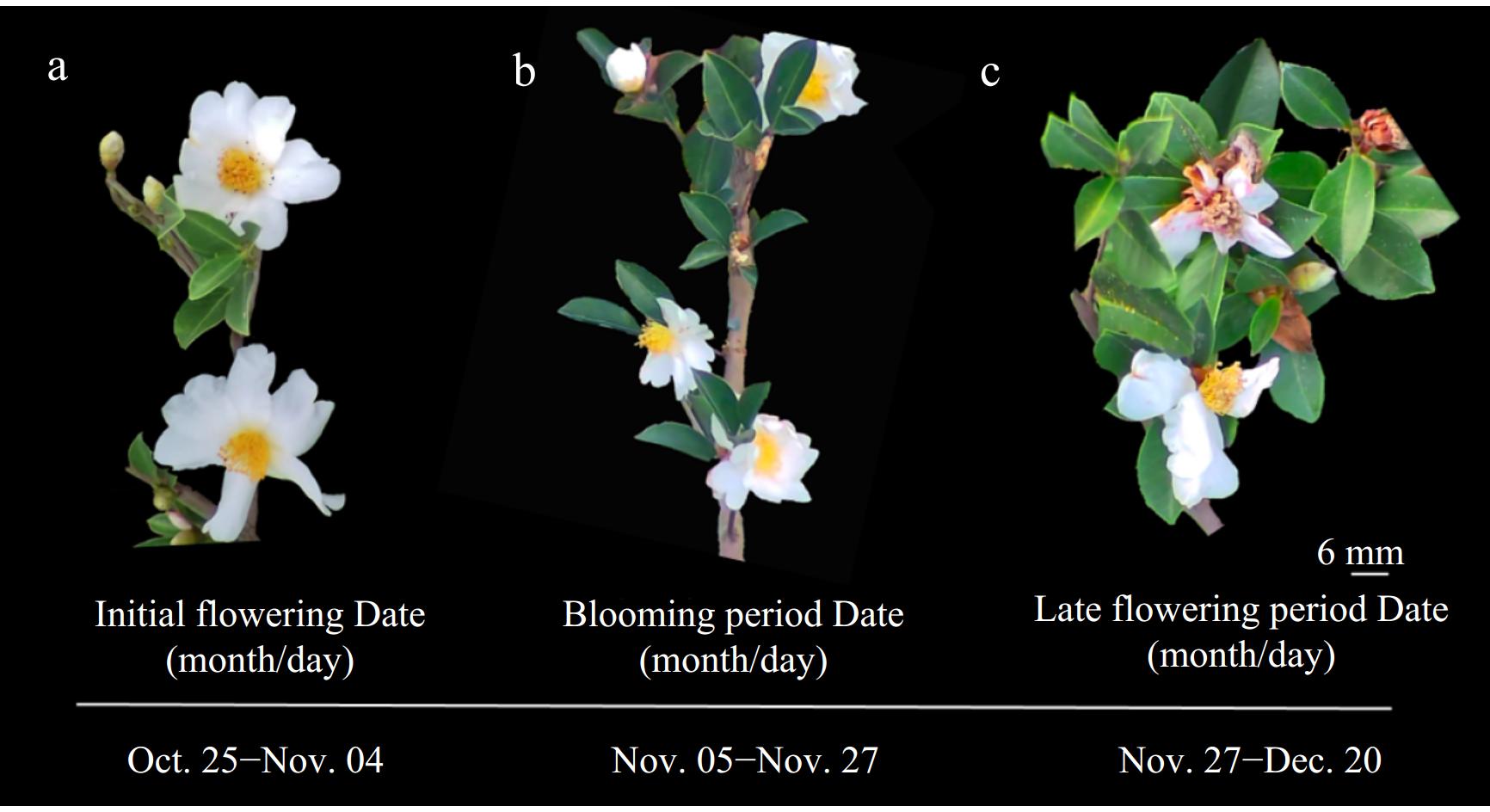

The flowering phenology of C. hainanica was observed and recorded for one year. Following the lignification and aging of germinated spring shoots, the leaf buds located at the apex of small branches and in the leaf axils of spring shoots began to differentiate into flower buds, which subsequently developed into small flower buds. In mid-to-late October, approximately 25% of the flowers on the target tree were fully bloomed, marking the onset of the initial flowering stage (Fig. 1). By November, 50%–75% of the flowers on the tree had opened, signifying the peak flowering stage. At the end of November, about 95% of the flowers had bloomed and withered, indicating the transition to the senescent flowering phase. The flowering period extended into mid-to-late December, though some trees retained a few flowers until early January of the following year, with the overall flowering duration lasting until mid-January. On average, the flowering period of 'H4' lasted 57 d.

Figure 1.

Flowering phenology of C. hainanica 'H4' in 2023. (a) Initial flowering date (Oct. 25–Nov. 4); (b) blooming period date (Nov. 5–Nov. 27); (c) late flowering period date (Nov. 27–Dec. 20).

Single flower opening dynamics

-

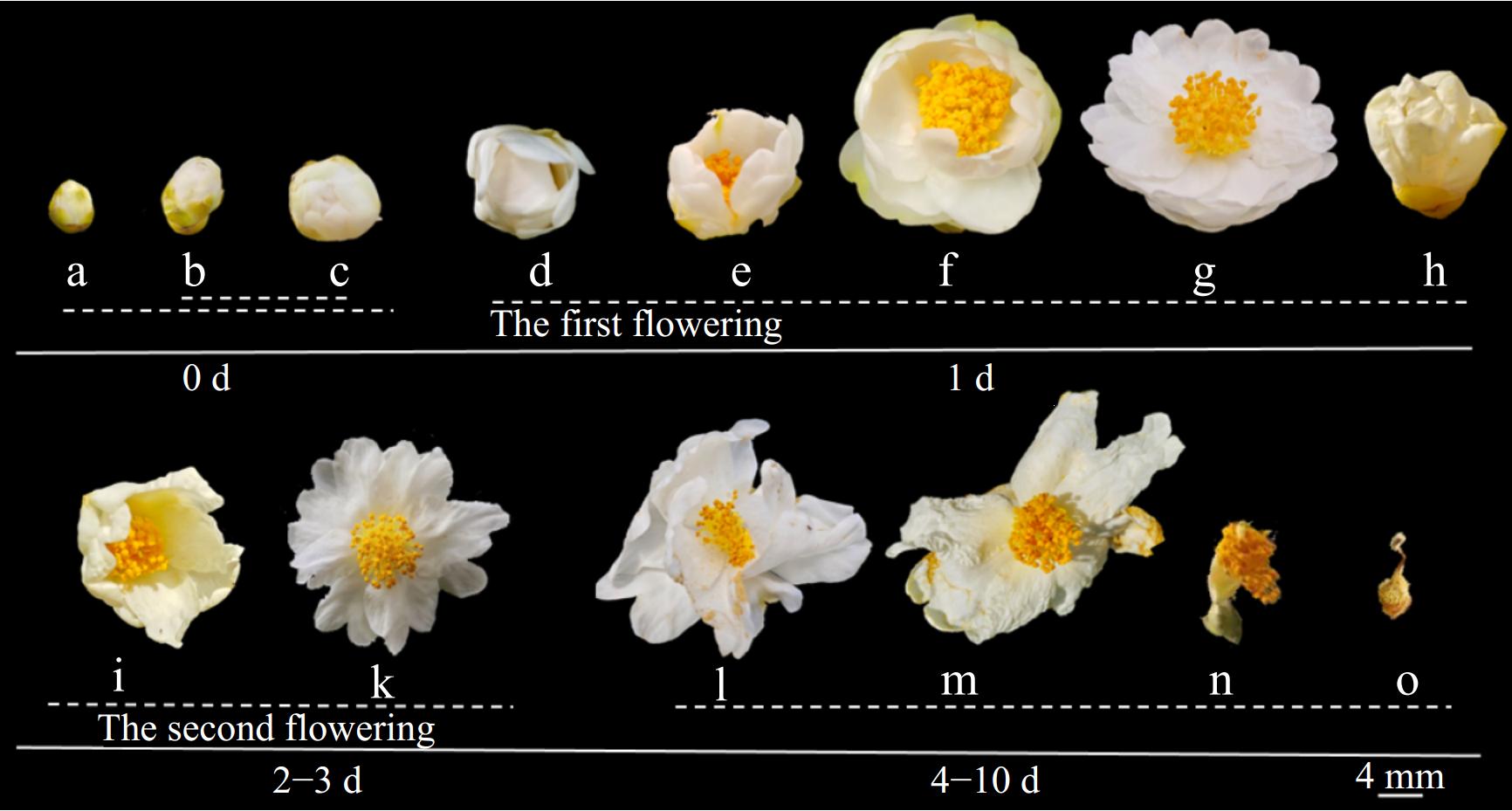

The flowering duration of 'H4' lasts for 5–10 d, with the blooming dynamics of a single flower illustrated in Fig. 2. According to the degree of petal unfolding and the developmental states of the androecium and gynoecium, the flowering dynamics of a single C. hainanica flower were divided into five stages (Fig. 2): (1) non-blooming stage (Fig. 2a–c), (2) slightly blooming stage (Fig. 2d, e), (3) first blooming stage (Fig. 2f–h), (4) second blooming stage (Fig. 2i–m), and (5) wilting stage (Fig. 2n, o).

Figure 2.

The flowering process of C. hainanica single flower. (a) Outer part of the bud was green; (b) bud began to loosen; (c) top view of the bud as it started to loosen; (d) petals gradually began to unfold; (e) stamens were exposed; (f) stamens and pistils were completely protruding; (g) flower blossomed fully for the first time; (h) flower began to close; (i) flower bloomed again; (k) flowers were fully open again; (l) petals began to wilter and fade; (m) petals withered and dropped; (n) petals had dropped entirely; (o) style turned brown.

(1) Before blooming, the buds are oblong, with the top gradually turning white (Fig. 2a). The bud transitions from green to white as it loosens and expands (Fig. 2b). The petals tightly closed, enclosing the stamens and pistils, with the apex of the bud displaying a light yellow hud (Fig. 2c).

(2) Petals begin to unfold on the morning of the first day (Fig. 2c). Within 2 h, the inner petals open slightly (Fig. 2e), causing the stamens and style to separate. The anthers remain full but have not yet begun to shed pollen, while a faint pollen fragrance is detectable. The transition from swollen buds to partially expanded petals occurs within a few hours under favorable lighting conditions.

(3) By midday on the first day, the petals are fully expanded, the flower diameter reaches its maximum, and the stamens and pistils are completely separated (Fig. 2f, g). The stamens radiate outward, and the orange-yellow anthers begin to dehisce and release pollen. In the late afternoon, the flowers begin to close, entering a preparatory phase for a second bloom the following day (Fig. 2h).

(4) After an overnight interval, the flower reopens (Fig. 2i). By the morning of the third day, the flower is fully open (Fig. 2k). The style secretes abundant mucus for pollen reception, and a strong fragrance is emitted to attract pollinators. This phase persists for 2–3 d. Over the subsequent 1–2 d, the anthers darken yellow-brown color, the stigma shrinks and darkens, nectar secretion, and the petals begin to fade and wither (Fig. 2l, m).

(5) During this final stage, the petals wither and fall off, followed by the complete detachment of the petals and filaments. The style turns brown, marking the end of the flowering process (Fig. 2n, o).

Morphological characteristics of the floral organs

-

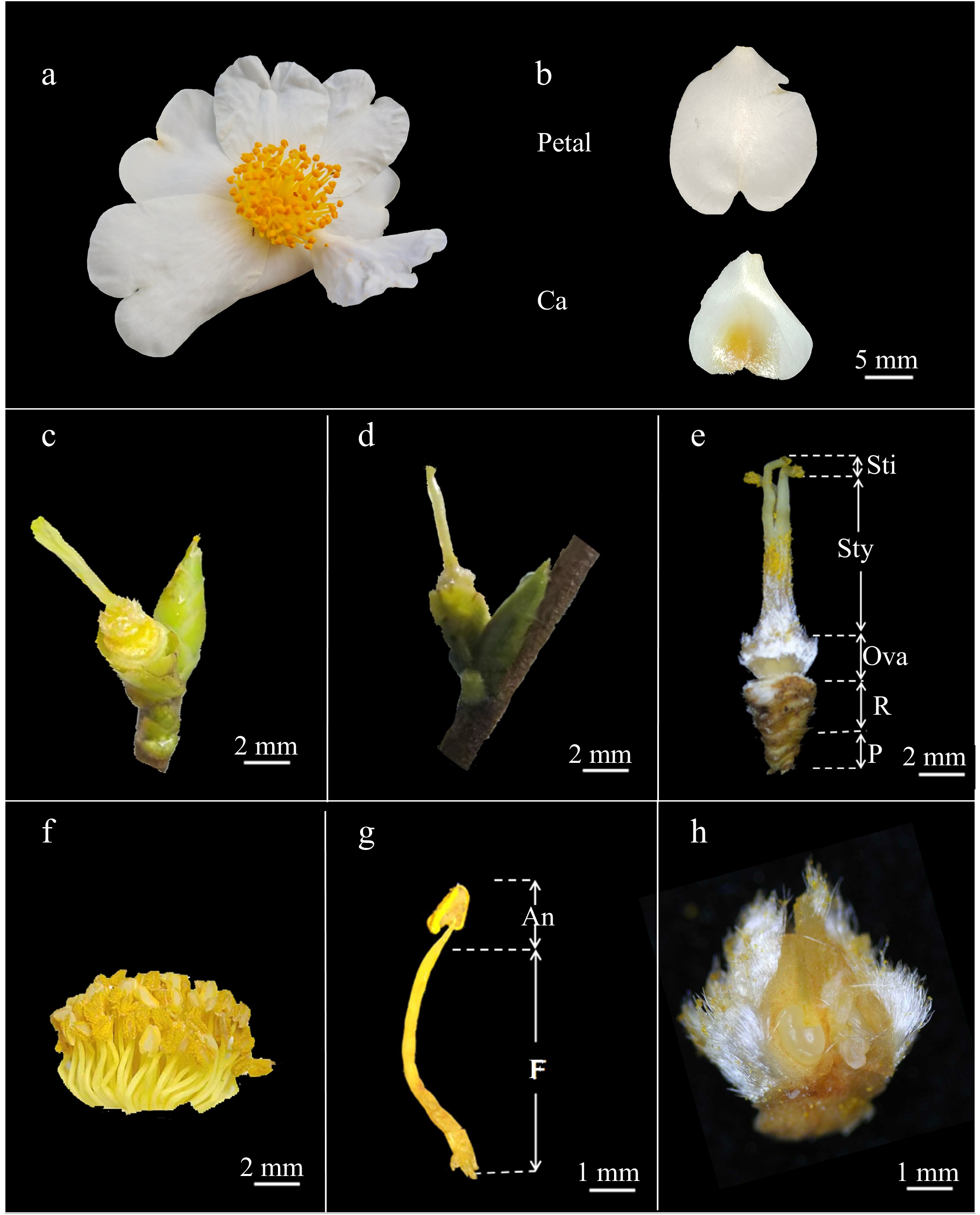

The flowers of 'H4' are white (Fig. 3a, b), and either terminal (Fig. 3c), or axillary (Fig. 3d). The pedicels are short and thick, approximately 3 mm in length, or are nearly sessile (Fig. 3e). The calyx consists of 5–6 sepals, which range in color from brownish yellow to yellowish green (Fig. 2a). During flowering, the sepals undergo petalization, where they develop petal-like characteristics, with sepals closer to the petal layer exhibiting more pronounced petalization. These petaloid sepals have a transverse diameter of 6.9–7.5 mm (Fig. 3b) and are more prone to falling off than the true petals. The petals are inverted heart-shaped and tend to exhibit irregular wrinkles (Fig. 3b). The flowers of 'H4' are double-petaled, containing flowers with 6–21 petals. The overall flower diameter ranges from 25.6 to 41.3 mm, while the transverse and longitudinal diameters of individual petals measured 12.1–17.0 and 13.6–19.6 mm, respectively. The anthers are golden yellow (Fig. 3f). The stamens and pistils have average lengths of 7.77 ± 0.88 and 7.61 ± 0.62 mm, respectively. Most stamens are taller than the pistils, although a few are shorter. The styles were 2- to 5-lobed, with 3- and 4-lobed styles being the most common. The surface of the ovary has sparse hairs. The stamens are arranged in 4–7 concentric whorls around the pistil, with an average diameter of 11.78 ± 1.34 mm for the stamen groups (Fig. 3f). The total number of stamens in a single flower ranges from 89 to 139.

Figure 3.

Organ morphology of C. hainanica. (a) External morphology of a flower; (b) morphological features of floral organs; (c) terminal flower bud; (d) axillary flower bud; (e) gynoecium morphology; (f) stamen group; (g) structure of anther; (h) ovary anatomy diagram. Petal: normal petals; Ca: petaloid sepal; An: anthers; F: filament; Sti: stigma; Sty: style; Ova: ovary; R: receptacle; P: pedicel.

Number of pollen grains

-

The pollen count of 'H4' was quantified using a cellulase assay. The number of pollen grains per anther ranged from 17,802 to 21,543, with an average of 19,615 ± 1,170 grains per anther. The average number of anthers per flower was 122 ± 13. Consequently, the total number of pollen grains per flower ranged from 2,163,833 to 2,618,552, with an average of 2,373,649 ± 139,795 grains per flower. Under a stereomicroscope, the ovules were shown to be tightly arranged within the locule of the ovary, exhibiting an irregular spherical shape. The number of ovules in C. hainanica ranged from 17 to 26, with an average of 20.80 ± 0.66 ovules per ovary.

Pollen vitality

-

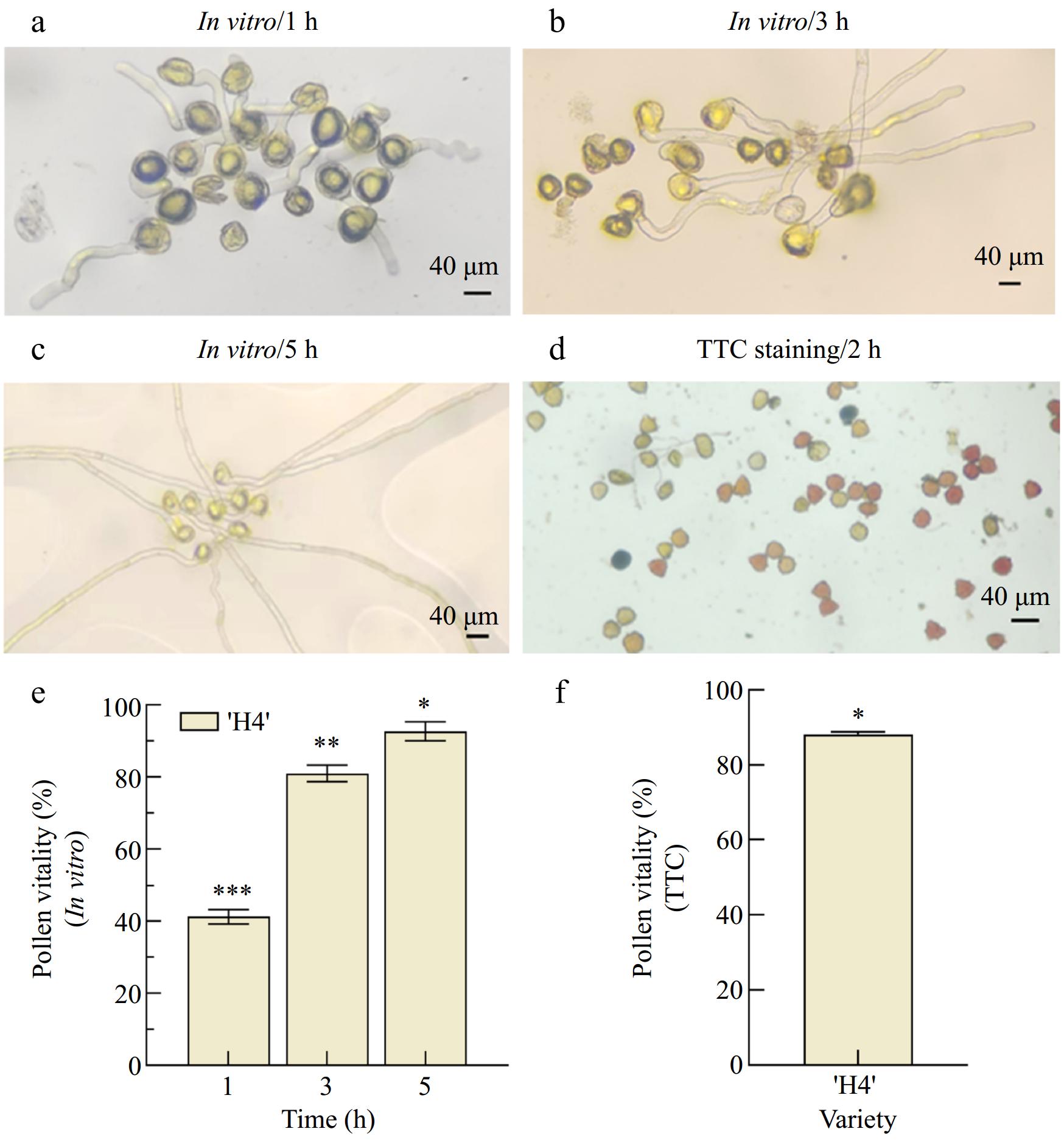

The pollen vitality of C. hainanica 'H4' at different stages was evaluated using an optimized in vitro pollen culture medium developed for C. oleifera (1% agar + 10% sucrose + 0.01% boric acid) (Fig. 4a–c). After 1 h of incubation, the average pollen viability of 'H4' was 41% (Fig. 4a). Following 3 h incubation, the viability increased significantly to 81% (Fig. 4b). When incubated for 5 h, the pollen viability peaked at 93 % (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Determination of pollen viability of C. hainanica using different methods. (a) Pollen phenotype of 'H4' after in vitro germination for (a) 1 h, (b) 3 h; and (c) 5 h. (d) Pollen phenotype of 'H4' after TTC staining for 2 h. (e) Germination rate of 'H4' pollen after 1, 3, and 5 h of in vitro culture, (f) 'H4' pollen TTC staining for 2 h. The symbols (*, **, ***) were significantly different by Duncan's test at p ≤ 0.05.

The pollen viability of 'H4' during the flowering period was further assessed using TTC staining[35]. After staining with TTC (5%), pollen grains exhibited significant color changes, turning red or rose pink depending on their vitality level. Over time, some grains developed into darker shades, such as dark red or brown (Fig. 4d). The pollen viability ranged from 82.77% to 87.53%, with an average of 85.15% (Fig. 4c).

Stigma receptivity

-

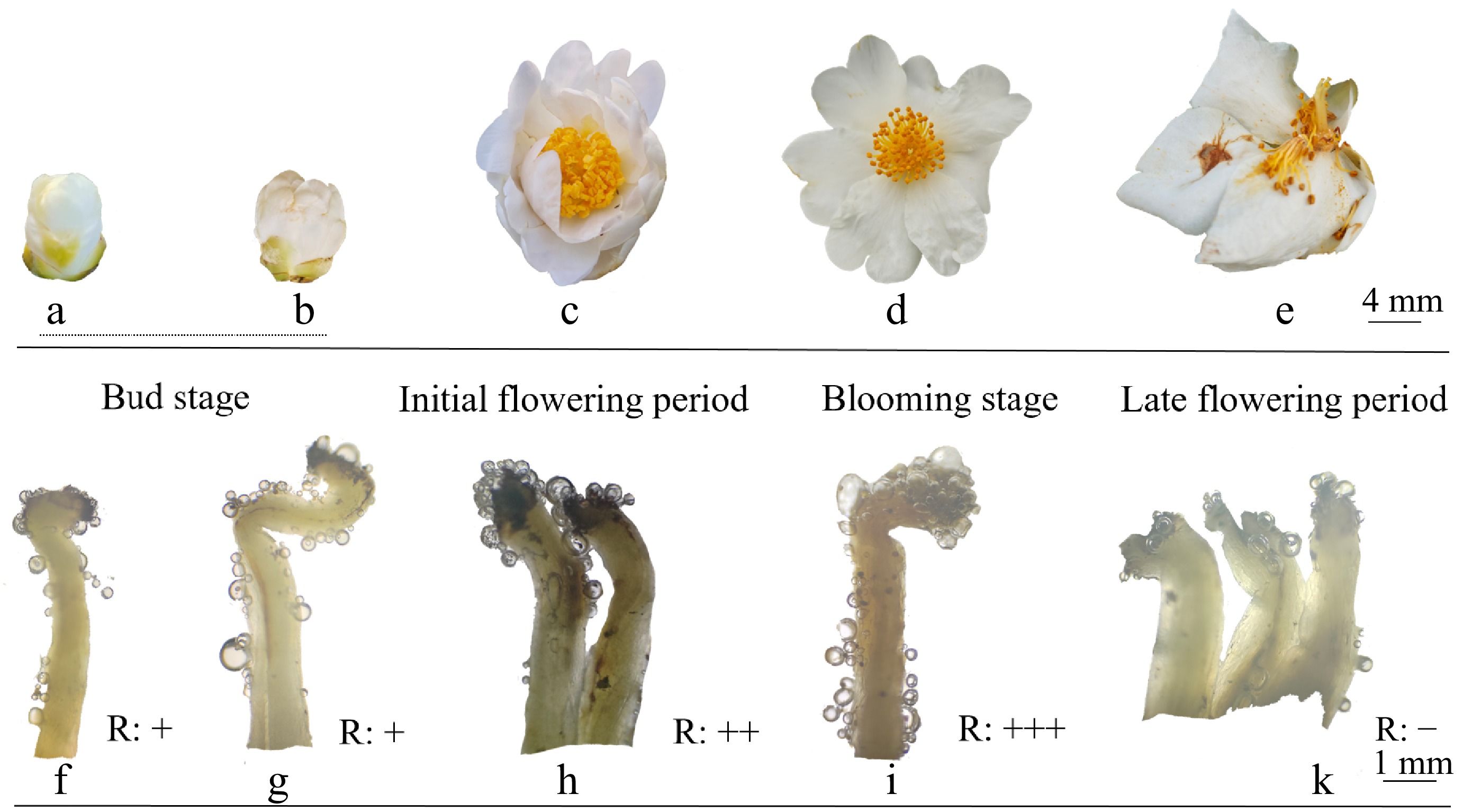

The benzidine-hydrogen peroxide method was used to measure the stigmatic receptivity of 'H4'. The results are displayed in Fig. 5. At each flowering stage of C. hainanica, bubbles could be observed on the stigmas, but their number and size varied. It was found that during the bud stage, only a small number of bubbles were produced on the stigma (Fig. 5f, g). However, the number of bubbles was greatest during the early and peak flowering stages, suggesting the strongest receptivity on the stigma (Fig. 5h, i). Stigmatic receptivity was lowest during the late flowering stage (Fig. 5k).

Figure 5.

Stigma receptivity of 'H4' at different blooming stages. (a) Small bud stage; (b) large bud stage; (c) initial flowering period; (d) blooming stage; (e) late flowering period. Graphical representation of the stigma receptivity in the (f) small bud stage, (g) large bud stage, (h) initial flowering period, (i) blooming stage, and (k) late flowering period.

Pollen storage

-

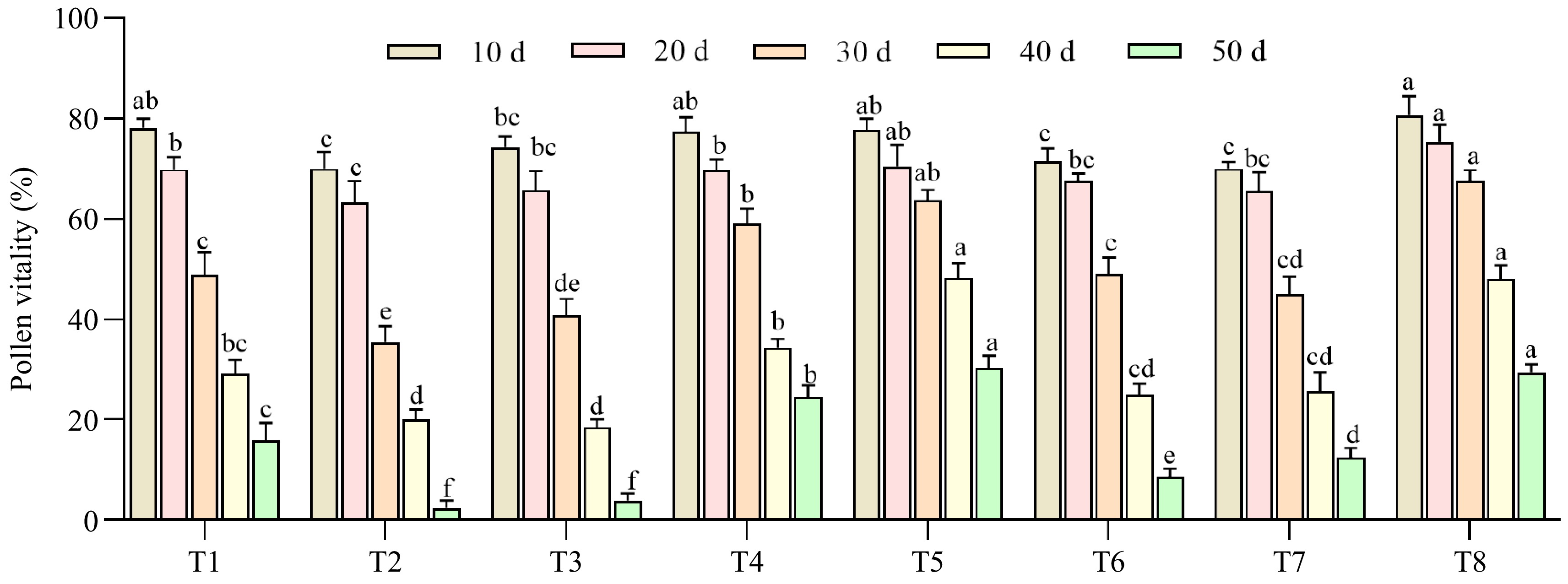

The viability of C. hainanica 'H4' pollen under various storage conditions was assessed using in vitro germination (Fig. 6). Under short-term storage (10 d), no significant differences were observed among most treatments, except for T2, T6, and T7. However, prolonged storage led to a significant decline in germination rates across all treatments (p < 0.05). The T3 treatment exhibited the most rapid decline, with its germination rate dropping to the lowest value of 4% by 50 d. In contrast, the T8 treatment demonstrated a slower reduction rate, maintaining a germination rate of 29% at 50 d. Overall, the germination rates for T8 at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 d were 81%, 75%, 68%, 48%, and 29%, respectively, consistently outperforming other treatments. These results indicate that the storage protocol combining '−80°C, sealed & dry, and air drying' is the most effective method for preserving pollen viability in C. hainanensis 'H4' (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Study on the effects of different treatment methods on the storage of C. hainanica pollen. T1 = RT + sealed + Fresh; T2 = RT + sealed & dry + Dried; T3 = 4 °C + sealed + Dried; T4 = 4 °C + sealed & dry + Fresh; T5 = −20 °C + sealed + Dried; T6 = −20 °C + sealed & dry + Fresh; T7 = −80 °C + sealed + Fresh; T8 = −80 °C + sealed & dry + Dried; 10 d, 20 d, 30 d, 40 d, 50 d = The number of days in storage. The different lowercase letters were significantly different by Duncan's test at p ≤ 0.05. (All data were compared horizontally at the same time).

Breeding system

-

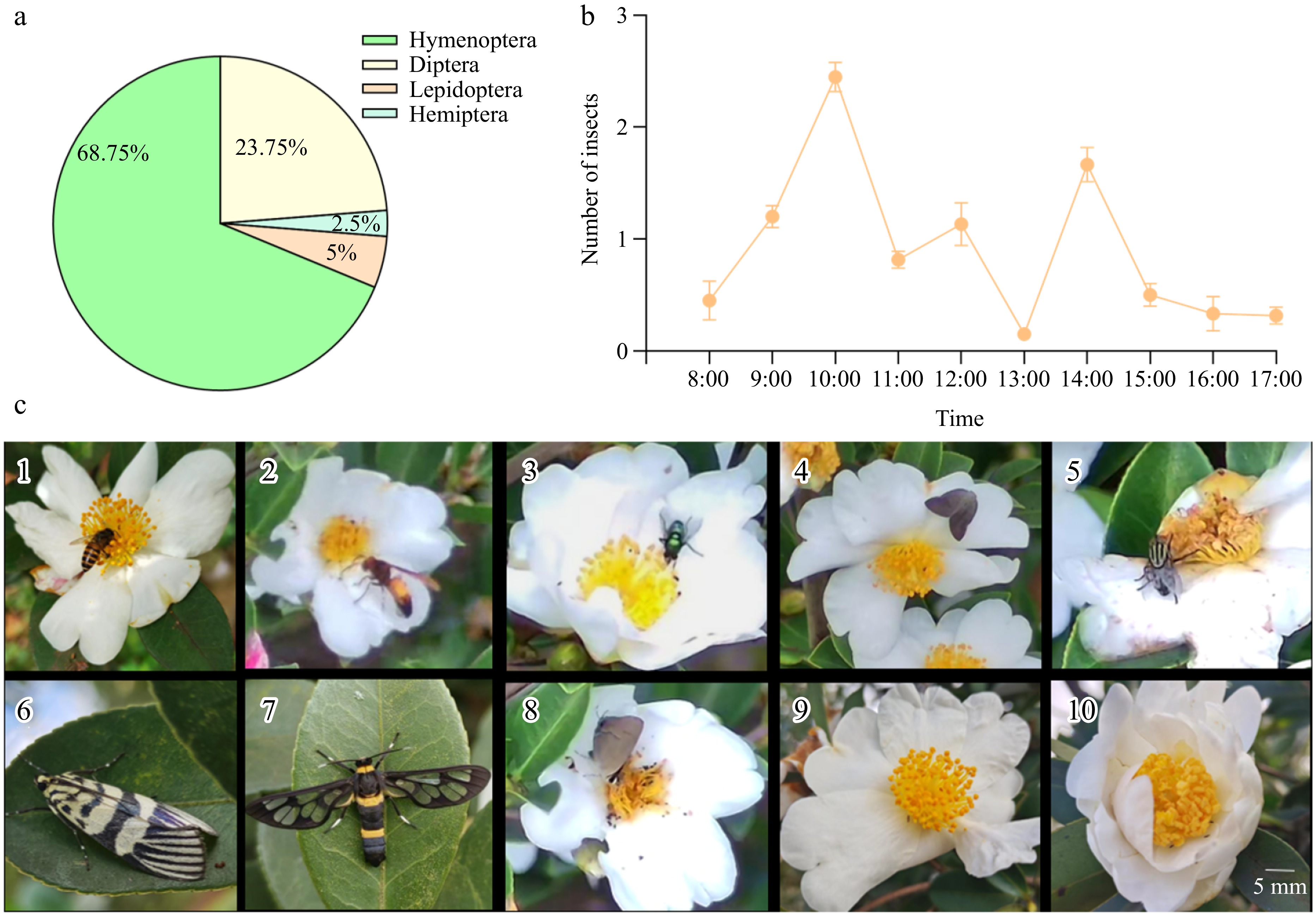

Approximately nine insect species, representing four orders, were observed visiting the flowers of C. hainanica 'H4'. The most prevalent order was Hymenoptera, accounting for 68.75% of all flower-visiting insects, followed by Diptera (23.75%), Lepidoptera (5%), and Hemiptera (2.5%) (Fig. 7a). The most abundant species was Apis cerana. The daily activity patterns of flower-visiting insects were recorded from 8:00 to 17:00, with the visitation frequency shown in Fig. 7b. Insect activity peaked at 10:00 and 14:00, whereas lower activity levels were observed during the early morning (8:00–9:00), late afternoon (13:00–17:00), and midday (13:00).

Figure 7.

Species of flower visiting insects. (a) Number of flower-visiting insects. (b) Average frequency of flower visits by insects (8:00–17:00). (c) Primary flower-visiting insects. (c1) Apis sp.; (c2) Vespa; (c3) Lucilia sp.; (c4) Hippoboscoidea; (c5) Sarcophaga; (c6) Heortia; (c7) Euproctis; (c8) Rapala; (c9) Formicidae; (c10) Thrips.

The P/O ratio of C. hainanica 'H4' was determined based on the number of pollen grains and ovules per flower, with the results summarized in Table 2. The number of pollen grains per flower ranged from 2,163,833 to 2,618,552, with an average of 2,373,649 ± 139,795. The number of ovules per pistil ranged from 17 to 26, with an average of 20.80 ± 0.66. The calculated P/O ratios of 'H4' ranged from 83,225.62 to 154,032.47, with an average of 114,117.76. Based on Cruden's[16] classification criteria, the breeding system of 'H4' is classified as obligate outcrossing.

Table 2. Pollen‒ovule (P/O) ratio of 'H4'.

Items Value Number of pollen grains per flower 2,163,833−2,618,552 Number of ovules per flower 17−26 P/O ratio 83,224.35−154,032.47 Reference value 2,108.00−195,525.00 Additionally, the OCI of 'H4' was estimated following the method outlined by Dafni[15], with the results provided in Table 3. The flowers of 'H4' typically measure between 25.6 and 41.3 mm in diameter, qualifying them for a score of '3' under the size criterion. During anthesis, the pistils mature first, corresponding to a score of '0' for temporal separation. Furthermore, the stigma and anthers are spatially segregated, resulting in a score of '1' for spatial arrangement. Consequently, the total OCI score for 'H4' is '4'. According to Dafni's[15] classification, the breeding system type of 'H4' is partially self-compatible and relies on pollinators for successful outcrossing.

Table 3. Outcrossing index (OCI) of C. hainanica.

Items Findings Scores Corolla diameter/mm > 6 3 Maturation sequence of androecium and gynoecium Protogyny 0 Spatial position between anthers and stigmas Existence of spatial segregation 1 Outcrossing index 4 Breeding systems Outcrossing, partially selfcompatible, pollinators required An artificial bagging pollination experiment was conducted on C. hainanica to determine its breeding system type (Table 4). Under the natural pollination treatment, the fruit set rate of C. hainanica was low, only 6.68%. In the bagging treatment—both without emasculation and with emasculation—the fruit set rate was 0%, indicating the absence of apomixis. In the geitonogamy treatment, where cross-pollination was performed within the same individual, the fruit set rate was 6.67%, suggesting that while C. hainanica can produce fruit through geitonogamous pollination, but its self-compatibility is low. Under xenogamy treatment, where cross-pollination was conducted between different individuals, the fruit set rate increased to 16.67%, the highest among all treatments. These findings indicate that the breeding system of C. hainanica is predominantly outcrossing, with partial self-compatibility. Successful pollination requires the assistance of pollinators.

Table 4. C. hainanica setting rate of different pollination methods.

Treatment No. of trees No. of flowers No. of fruits Fruit-set rate Natural pollination 4 30 2 6.67% No emasculation, bagged 4 30 0 0 Emasculation, not bagged 4 30 3 10% Geitonogamy 4 30 2 6.67% Xenogamy 4 30 5 16.67% Emasculation, bagged 4 30 0 0 -

A comprehensive and systematic understanding of the biological characteristics of plant flowering is essential for studying plant life histories, as well as for the conservation, utilization, and breeding of germplasm resources[36]. In field production, the flowering phenology of plants is closely tied to pollination processes[37,38]. Generally, the flowering period of the C. oleifera population spans from mid-October of the current year to late January of the following year, lasting about 80 d, with approximately 40 d of full bloom. Based on the flowering period, the population can be classified into three types: early, medium, and late flowering periods[39]. In this study, C. hainanica entered its full-bloom in early November, categorizing it as a medium-flowering type. Comparing the flowering periods of different tea-oil Camellia varieties reveals variation due to latitude, often exhibiting a normal distribution[40]. Although C. hainanica is distributed in low-latitude regions, its overall flowering period, from late October to late December, is similar to that of C. oleifera 'Huashuo' and C. vietnamensis[41,42]. This overlap suggests their potential for cross-pollination in the future. The flowering duration of a single 'H4' flower generally lasts for 10 d, longer than the bloom period of both 'Changlin' series of C. oleifera and C. osmantha, which typically last less than 9 d[43,44]. This extended bloom duration suggests that C. hainanica may have more pollination opportunities compared to other oil-tea Camellia species and C. osmantha, which could positively impact its yield. During the flowering process of C. hainanica, we observed a notable phenomenon of secondary blooming among the flowers. The closure of these flowers creates a microenvironment within, characterized by stable temperature and high humidity conditions, which in turn facilitates anther development and enhances pollen functionality. Consequently, this environmental control leads to an increase in seed production, ultimately supporting successful reproduction in early spring[45−47].

Flowers, as the reproductive organs of angiosperms, exhibit diverse morphological characteristics that influence pollinator preferences and subsequently affect pollination and mating[48−50]. According to Abe's[51]classification standard, 'H4' belongs to the category of large flowers, which may enhance pollination opportunities. In this study, a total of 13 species of flower-visiting insects were observed, with Vespa bicolor and Ricania speciosa (wax cicada) classified as medium to larger-sized insects. This finding suggests that larger flowers can attract larger pollinators, thereby increasing pollination success. Additionally, the golden-yellow stamens of C. hainanica, clustered at the flower's center, create a striking contrast with its white petals, potentially serving as a visual cue to attract pollinators. This distinct floral display likely contributes to insects visiting the flowers accurately and feeding on the pollen (Fig. 3).

Pollen viability of C. hainanica

-

Pollen grains are produced within the anthers of higher plants and serve as the unit of sexual reproduction, carrying male genetic material[52]. Rich in genetic information, pollen exhibits a high degree of genetic conservation, making it a crucial basis for studies on plant origin, evolution, classification, and species identification[53]. He et al.[54] compared the pollen counts of individual anthers in seven Camellia varieties and found that C. giganlocarpa had the highest pollen count (9,441.3[54]), which likely contributes to its high fruit-setting rate. In this study, 'H4' showed 122 ± 13 anthers per flower, with the number of pollen grains per anther ranging from 17,802 to 21,543. This demonstrates that C. hainanica produces substantially higher pollen quantities compared to most C. oleifera varieties and C. gigantocarpa, highlighting its distinctive reproductive characteristics in the genus.

Pollen germination capacity, a critical determinant of successful stigma pollination and high-quality seed formation, is directly influenced by pollen viability[55−57]. In C. hainanica 'H4' , TTC staining — a conventional method for rapid viability assessment[35,58,59] — revealed pollen viability ranged from 82.77% to 87.53%. However, in vitro germination tests, widely regarded as a more reliable approach for pollen vitality evaluation for its direct observation of pollen tube growth under controlled conditions[60−63], demonstrated a markedly higher germination rate of 93% after 5 h cultivation, which outperformed C. oleifera (70.47%−87.91%[35,64]). This discrepancy between TTC staining and germination assay results aligns with observations in other species such as Prunus laurocerasus[65], suggesting that TTC-based viability metrics may not consistently correlate with actual germination performance in certain taxa. While TTC staining offers advantages in speed and simplicity, its susceptibility to environmental variables limits diagnostic accuracy[66,67]. Conversely, the in vitro method, despite requiring specialized media (e.g., sucrose and boric acid to promote tube elongation), provides superior consistency and biological relevance. The observed divergence between the two methods likely stems from nutrient-enhanced germination in vitro, where culture medium components critically influence pollen tube development.

Another key factor during the pollination stage is stigma receptivity, which is regulated by various enzymes produced at different phases of floral development and significantly influences pollination success. This receptivity varies across cultivars, with the highest stigmatic acceptance typically observed in the youngest flowers, followed by a gradual decline[68,69]. The findings of this study revealed that the 'H4' cultivar exhibited the highest stigmatic receptivity during the initial and peak flowering stages. In comparison, Camellia weiningensis and ten other primary cultivars displayed peak stigmatic receptivity within the first to third days of flowering, after which it declined[25,26]. Notably, the period of high stigmatic receptivity in 'H4' was significantly prolonged compared to other oil-tea camellia cultivars.

The source and vitality of pollen significantly affect fruit set rates in cross-pollination[70] and the nutrient content[71,72]. Low-temperature storage is commonly used to preserve pollen viability across various plant species[60,73]. The storage duration and effectiveness vary widely among species[34,74]. For instance, Phalaenopsis and apple pollen retained high germination rates after 96 weeks at −20 °C and 6 months −80 °C (50% and 59%, respectively). However, C. hainanica and C. oleifera pollen show lower viability under similar conditions[75], suggesting their classification as recalcitrant pollen with inherently low storability.

This study highlights the significant impact of drying treatments on C. hainanica pollen viability. Air-dried pollen proved more conducive to long-term storage, consistent with findings in Exochorda racemosa[76] (Fig. 6). Meanwhile, after storage at −20 to −80 °C for 50 d, the germination rate showed little difference (31% and 29%), but was significantly higher than that at 4 °C and room temperature (4% and 2%). As a 50% germination rate is typically considered the minimum standard for viable pollen storage[76], the optimal storage combination for C. hainanica pollen is −80°C, sealed dry conditions, and air-dried storage for about 40 d (Fig. 6). For further improvement, ultra-low temperature storage methods could be explored to enhance long-term preservation.

Reproductive system type of C. hainanica

-

The plant reproductive system is a central focus in evolutionary biology, influencing pollination, mating strategies, and ecological adaptation[77]. Floral characteristics play a significant role in shaping pollination dynamics, often demonstrating a degree of co-adaptation with the plant's breeding system. Understanding these systems is essential for optimizing pollination strategies and ensuring reproductive success[78]. The OCI and P/O ratios are widely used metrics for studying plant breeding systems[79]. Most tea-oil Camellia species are self-incompatible and rely heavily on insect pollinators for successful reproduction[80]. Similarly, the results of this study indicate that C. hainanica 'H4' exhibits a mixed mating system that is primarily outcrossing but partially self-compatible, requiring pollinators for effective reproduction. Pollinator activity plays a critical role in determining fruit set rates in oil-tea Camellia. Studies have shown that insect visits significantly enhance the fruit yields of C. osmantha, C. vietnamensis, and C. oleifera[81]. However, the overlap of the flowering season with winter poses a challenge due to reduced insect activity during this period. Artificial pollination has been proven effective in increasing fruit set rates in C. oleifera[82], providing valuable insights for improving the productivity of C. hainanica. Given that C. hainanica shares similar reproductive characteristics with C. oleifera, leveraging artificial pollination techniques or introducing supplementary pollinator species could serve as practical approaches to enhance its yield.

According to the research, the low fruit set (6.68% in nature) in C. hainanica likely arises from a combination of its obligate outcrossing breeding system, seasonal pollination constraints, and pollinator limitations. As an obligate outcrosser (P/O ratio = 114,117.76), successful reproduction requires cross-pollination with genetically distinct individuals (pollen donor trees), yet natural populations may lack sufficient compatible genotypes, reducing effective pollen transfer. Additionally, its peak flowering in winter coincides with reduced pollinator abundance, exacerbating reproductive challenges. Dominance of Apis cerana as the primary pollinator (68.75% of visitors) introduces further risks, as oil-tea pollen consumption may induce toxicity in honeybees[83,84], potentially deterring visitation. This aligns with the observed low natural fruit set (6.68%) despite high pollen viability (93% at 5 h in vitro), which declines rapidly under natural conditions.

To address these barriers, strategic interventions are critical. First, establishing pollinator orchards with genetically compatible trees could enhance cross-pollination efficiency. Second, artificial pollination using high-viability pollen during peak stigma receptivity (early to peak flowering stages) may compensate for pollinator scarcity. Third, optimizing pollen storage protocols (−80 °C, desiccated) could extend viability for controlled pollination. Finally, introducing alternative pollinators (e.g., Andrena camellia)[85], or mitigating pollen toxicity effects on A. cerana may stabilize visitation rates. Integrating these approaches with breeding efforts to select self-compatible genotypes could synergistically improve reproductive success in this species.

-

This study is the first comprehensive investigation into the flowering biology and breeding system of C. hainanica 'H4'. The findings demonstrate that C. hainanica exhibits strong adaptability in its flowering phenology and pollination mechanisms, aligning well with the internal floral structures and external morphological features. The flowering period of 'H4' spans approximately 40 d, with individuals remaining in bloom for 5 to 10 d. A unique phenomenon of secondary opening and closing was observed during the blooming process of single flowers. Petaloidy of the calyx was noted, with more pronounced petaloidy in calyces closer to the petal layer. The average pollen production per flower was estimated to be 2,373,649 ± 139,795 grains. Pollen viability was assessed using TTC staining, with viability ranging from 82.77% to 87.53%. The in vitro germination method revealed that pollen viability peaked at 93% after 5 h of culture. However, after 40 d of storage, pollen viability declined to approximately 50%. The optimal pollen storage conditions for C. hainanica were determined to be −80 °C under sealed and dry conditions with air-drying, effectively delaying pollen inactivation. Based on the P/O ratio, OCI value, and artificial pollination experiments, the breeding system of C. hainanica was identified as primarily outcrossing with partial self-compatibility, requiring pollinators for successful reproduction.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160719, 32060365); the Key Science and Technology Plan Program of Haikou City (2022-013); and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (324MS010).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li M, Yuan D, Li J, Wang J; experiments conducted: Li M, Wang S, Li C, Dai S, Zhang R, Xu H; writing - draft manuscript preparation: Li M; writing – review & editing: Wang J, Li J, Li J, Wang T, Li T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Received 6 February 2025; Accepted 21 March 2025; Published online 17 April 2025

-

The flowering dynamics of a new species of Camellia, C. hainanica, have been systematically studied.

The breeding system is partially self-fertilization, outcrossing, and reliant on pollinators.

−80 °C, sealing and air drying are conducive to pollen storage.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li M, Li J, Wang S, Li C, Dai S, et al. 2025. The flowering dynamics and breeding system in Camellia hainanica 'H4'. Tropical Plants 4: e017 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0012

The flowering dynamics and breeding system in Camellia hainanica 'H4'

- Received: 06 February 2025

- Revised: 14 March 2025

- Accepted: 21 March 2025

- Published online: 17 April 2025

Abstract: Camellia hainanica, a newly identified species in Hainan Province, China, is an edible oil tree with low fruit set under natural pollination. This study examined the flowering dynamics and reproductive system of C. hainanica 'H4'. Flowering occurred from mid-October to late December, peaking in early November. Each flower produced 2,373,649 ± 139,795 pollen grains. Stigmatic receptivity, measured via benzidine-hydrogen peroxide method, peaked during the initial and peak flowering phases. Orthogonal array experiments identified optimal pollen storage at '−80 °C, sealed & dry, and air drying', maintaining 93% viability after 5 h in vitro germination—significantly exceeding C. oleifera (70.47%−87.91%). Pollination experiments revealed partial self-compatibility, with geitonogamy yielding a lower fruit set than xenogamy. No fruit set occurred in direct bagging or emasculation without pollination, indicating reliance on cross-pollination. The pollen-ovule (P/O) ratio (114,117.76) and outcrossing index (OCI = 4) suggested a partially self-compatible, outcrossing breeding system dependent on pollinators. Floral visitation peaked at 10:00 and 14:00, with Apis cerana identified as the most effective pollinator. These findings demonstrate that low natural yield in C. hainanica stems from pollinator limitation and partial self-incompatibility. Strategic introduction of managed pollinators and inter-varietal planting are recommended to enhance cross-pollination efficiency.

-

Key words:

- Camellia hainanica /

- Flowering phenology /

- Breeding system /

- Pollen