-

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.), a dicotyledonous plant in the Convolvulus family[1], ranks among the seventh largest flowering plant families globally. In China, it is the fourth most significant food crop, with the largest cultivation area worldwide, contributing approximately 54.19% to global production[2]. Renowned for their nutritional richness, sweet potato roots are high in proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and various essential nutrients[3]. Additionally, they are a good source of fiber, which can improve the gut microbiome and promote beneficial immune responses[4]. Sweet potato roots are harvested for their water content and delicate structure but are susceptible to various postharvest challenges, including sprouting, nutritional degradation, microbial contamination, and mechanical injury during harvesting, transportation, and storage. The necessity for extended storage to enhance the availability, and marketability of sweet potatoes is further complicated by high temperatures, which can trigger sprouting, significantly reduce commercial viability, and complicating long-term preservation efforts[5]. Germination accelerates nutrient losses and increases water transpiration, resulting in greater weight loss of the roots. This deterioration in quality contributes to higher rejection rates and waste of fresh sweet potato roots[6]. These combined effects negatively affect the edibility and processing potential of sweet potato roots and results in substantial economic losses.

Ethylene (C2H4) is a biologically active gaseous hormone recognized as the principal endogenous regulator of maturation and senescence in respiratory, leptotropic plant organs[7,8]. 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) serves as an inhibitor of ethylene action, mitigating the senescence and decay of plant organs caused by ethylene. In European and American countries, ethylene and 1-MCP were used as chemical agents to inhibit sprouting and maintain the quality of potato tubers during storage[9]. Currently, 1-MCP is commercially registered and marketed in the United States, Europe, and Asia, with numerous studies confirming its effectiveness in preserving agricultural products[10,11]. Sustained treatments with ethylene or 1-MCP effectively inhibit germination in sweet potato roots. In addition, 1-MCP treatment significantly reduces root germination and decay during the healing process and long-term storage of the roots[12]. Previous studies demonstrated that storing onions in an ethylene-enriched environment can extend their storage duration while maintaining acceptable quality for up to seven months[13]. A concentration of 1 μL·L−1 of 1-MCP significantly inhibited root sprouting in ginger tubers at ambient temperature, preserving quality by reducing the accumulation of oxidative enzymes[14]. Furthermore, 1-MCP treatment of mustard roots delayed senescence and quality deterioration, maintaining good eating quality and nutritional value for up to 35 d of storage[15].

Exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP treatment effectively inhibit root germination and reduce root rot without affecting the storage quality of sweet potato roots[16]. In recent years, the role of exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP in the storage and preservation of sweet potato roots has gained significant attention. Sweet potato roots are generally classified as respiratory climacteric roots due to their high respiration rates during postharvest. However, some studies indicated that sweet potato roots exhibited low sensitivity to ethylene and produce minimal ethylene during storage, leading to their classification as non-climacteric roots. This classification of the respiration type of sweet potato roots needs further investigation as it may differ among varieties. For instance, the roots of the 'Covington' variety treated with 10 μL·L−1 ethylene exhibited increased glucose metabolism, phenolic formation, and hormone changes, significantly inhibiting germination[17]. The combination of healing treatment with exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP treatment significantly reduced root rot and sprouting in the varieties of 'Beijing 553' and 'Chuan Shan Zi' compared to the control group[12]. Continuous exogenous ethylene treatment (10 μL·L−1), with 24-h applications of 1-MCP at 625 nL·L−1 and AVG at 100 μL·L−1, significantly suppressed root rot and shoot emergence in the 'Bushbuck' and 'Ibees' varieties when stored at 25 °C[7]. Moreover, the roots of these varieties treated with the combination of 1-MCP and AVG exhibited higher concentrations of glucose and fructose than those treated with ethylene alone. 1-MCP treatment did not alter the inhibitory effects of ethylene on germination, indicating that the action of ethylene remained unaffected. Overall, treatments with ethylene, 1-MCP, and their combination effectively inhibited tuber sprouting and reduced decay without compromising the storage quality of sweet potato roots[18]. However, the research of systematic and comprehensive research regarding the optimal application of exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP, as well as the molecular mechanisms underlying their preservation effects on sweet potato roots was limited.

Transcriptomic analysis has become a powerful tool for understanding the mechanisms of plant development[19]. In recent years, transcriptome sequencing has increasingly contributed to studies investigating how ethylene and 1-MCP regulate postharvest processes in fruits. However, the specific mechanisms by which these compounds preserve the freshness of sweet potatoes remain unclear. Ethylene-induced inhibition of potato tuber germination is complex, with both physiological and transcriptomic results indicating that this inhibition may be linked to the suppression of endogenous growth hormone production and signaling, as well as the activation of ethylene signaling pathways[20]. Transcriptome sequencing, combined with hormonal analysis, has explored potential mechanisms underlying ethylene-induced dormancy and the emergence of onion tubers. Notable findings include significant upregulation of the ethylene synthesis gene ACO, the receptor gene EIN4, and the transcription factor EIL3 following ethylene treatment. In contrast, the ethylene signaling gene EIN2 was significantly downregulated, while the expression of the transcription factor ERFs was markedly increased[21]. Although ethylene and 1-MCP are believed to be closely linked to postharvest modifications in sweet potato roots, the precise genes and metabolic pathways involved, as well as their regulatory mechanisms, remain poorly understood. Therefore, elucidating how exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP influence postharvest freshness in roots, along with the underlying molecular regulatory mechanisms at the transcriptomic level, is essential for enhancing the commercial value of sweet potato roots.

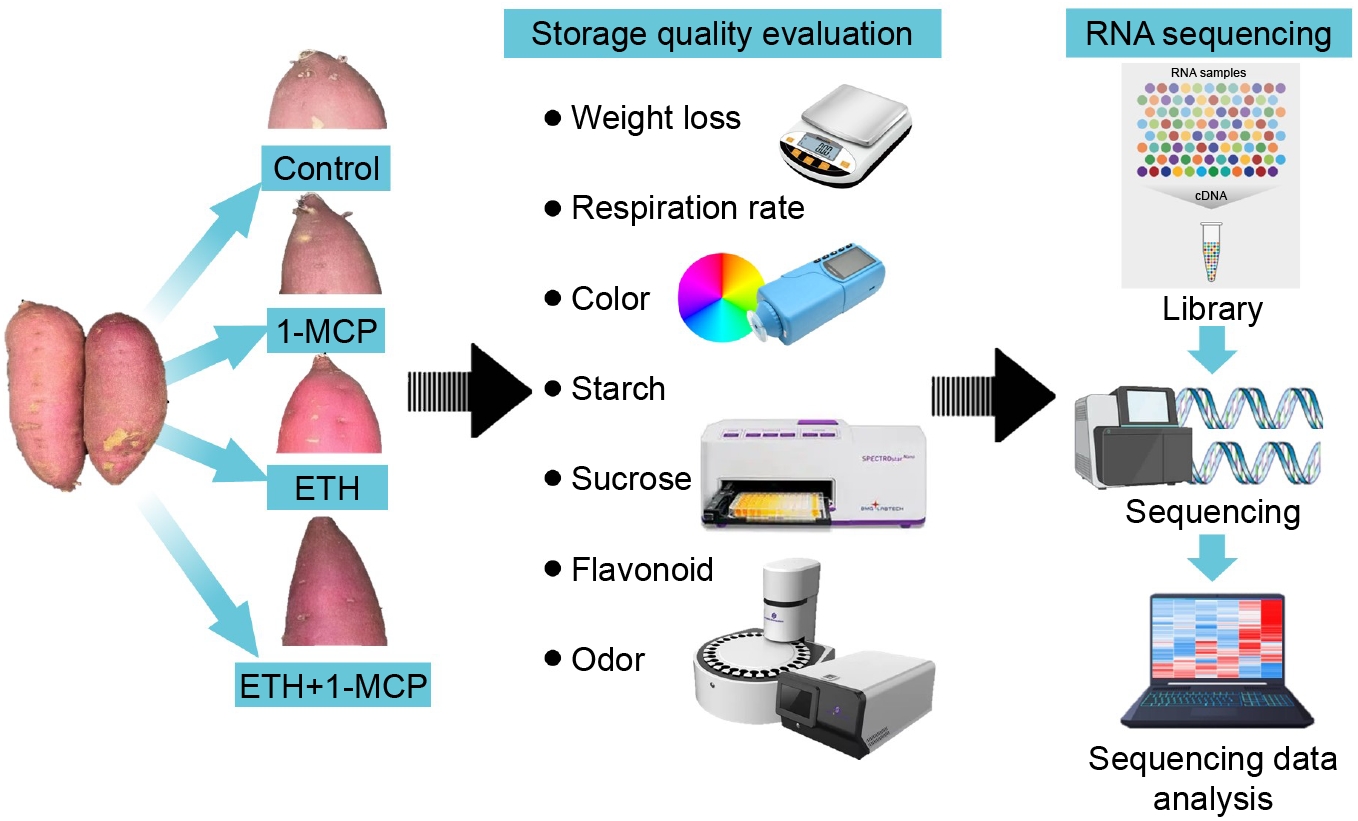

In this study, we utilized the organic sweet potato cultivar Kokei No.14 from Hainan Province (China). We systematically screened various treatments involving exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP, focusing on treatment concentration and duration, to assess their impact on sprouting rates and quality changes in sweet potato roots. Additionally, we explored how these treatments influence postharvest storage. To establish the optimal treatment protocol for prolonging root freshness, we examined the effects of exogenous ethylene and 1-MCP on harvested roots. Concurrently, we employed transcriptome sequencing to analyze RNA from roots subjected to combined treatments of ethylene and 1-MCP. This sequencing method provides comprehensive information on expressed genes in sweet potato roots and allowed us to identify and verify key regulatory genes, offering a theoretical basis for improving postharvest storage practices.

-

All fresh sweet potato roots (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) were harvested from a commercial farm located in Danzhou, Hainan Province (China). To avoid mechanical injury, the harvested roots were packed in plastic crates, with each layer separated by soft fabric. They were then transported to the postharvest laboratory at Hainan University (25 °C, 75%−80% relative humidity) within four hours. Only well-formed roots with uniform appearance, size, and color were washed with distilled water, dried at room temperature, and used for further experiments.

Postharvest treatment

-

Sweet potato roots were randomly placed into 12 plastic sealed boxes (20 L) with 40 roots per box. Each box contained a 9 cm × 9 cm electric fan to circulate gas during the treatment period. Three boxes were allocated for each postharvest treatment method, resulting in a total of four methods: Control: air; Ethylene (Shanghai Shengli Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) treatment: 200 μL·L−1; 1-MCP (Smart FreshTM, Agrofresh Inc., USA) treatment: 30 μL·L−1; Ethylene + 1-MCP treatment: 200 μL·L−1 + 30 μL·L−1. The temperature inside the boxes was maintained at 25 °C, with relative humidity held at 90%, allowing the roots to be fumigated for 48 h.

Measurement of weight loss, respiration rate, and color

-

Weight loss was expressed as the percentage of weight lost compared to the initial weight. A total of 12 gas-tight boxes (7.5 L each) were randomly arranged, with three boxes designated for each treatment and three as reference samples. Each box contained six sweet potato roots, which were weighed and sealed for 1 h at 25 °C. The oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels were measured using a portable O2/CO2 headspace analyzer (Jinan Saicheng, DK190). The respiration rate was calculated and expressed as CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1.

The L*, C*, and h* color values of roots were determined using a colorimeter (Shenzhen Linshang Technology Co., Ltd, LS170). The instrument was calibrated with a standard white plate. The L* value indicates lightness and ranges from 0 to 100. The C* value represents Chroma can exceed 100%, with no upper limit. The h* value represents hue, ranging from 0 to 360 degrees. For each treatment, six roots were measured, and color readings were taken at three evenly distributed equatorial sites on each root. The average values were calculated in this study.

Measurement of hardness and TPA

-

A physical property analyzer (FTC company model TMS-PRO) was used to evaluate the textural properties of sweet potato roots by puncture tests and Texture Profile Analysis (TPA). The puncture test was performed on the equatorial region of each tuber using a 2 mm diameter stainless steel cylindrical probe, at a speed of 50 mm·min−1 and a puncture distance of 20 mm. The maximum peak force (N) indicating hardness was recorded as a parameter of the puncture test. Samples were washed, peeled and cut into 1 cm3 cubes. TPA tests were performed using a disc compression probe (75 mm diameter), at a speed of 30 mm·min−1 and a trigger force of 0.38 N. Each treatment was measured with three roots, with each root tested in triplicate.

Measurement of root germination rate and length

-

The number of sprouts was determined considering only those longer than 1 mm and the results expressed as the average number of sprouts per root. Sprout length was measured with digital calipers and expressed in millimeters.

Measurement of starch, sucrose, and flavonoid content

-

Starch, sucrose, and flavonoid contents were measured both while dormant and after sprouting. Roots were cut into cubes (approximately 0.5 cm3), immediately placed into liquid nitrogen, and then transferred to storage at −80 °C. Frozen powdered root samples were used for the determination of starch, sucrose, and flavonoid content using a starch content assay kit (BC0700, Solarbio, Beijing, China), sucrose content assay kit (BC2460, Solarbio, Beijing, China), and a flavonoid content assay kit (BC1330, Solarbio, Beijing, China) by spectrophotometry (Shanghai Spectrum SP-756P, Instrument Co., Ltd., China).

Briefly, starch content was determined by using 80% ethanol to separate soluble sugars from starch in the sample. The starch was then hydrolyzed into glucose through an acid hydrolysis method. The glucose content was measured using the anthrone colorimetric method, which allows for the calculation of starch content, expressed as mg·g−1. Sucrose content was determined by mixing the sample with an alkaline solution and heating it to eliminate reducing sugars. Under acidic conditions, sucrose was hydrolyzed to produce glucose and fructose. The fructose then reacted with resorcinol to form a colored complex, which has a characteristic absorption peak at 480 nm. Sucrose content is expressed in mg·g−1. Flavonoid content was measured by forming a red complex with aluminum ions in the presence of an alkaline nitrite solution, which has an absorption peak at 470 nm. The absorbance of the sample extract at this wavelength allowed for the calculation of flavonoid content, expressed as mg/100 g.

Electronic nose and sensory analysis

-

Electronic nose (Shanghai Ruifen International Trade Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) with 18 sensor reactions (SN-1~SN-18) was preheated for 30 min before measurement. Root samples were chopped (10 g) and placed into 40 mL headspace bottles, then left in a room temperature environment for 30 min to collect headspace gas. Three sweet potato roots were measured for each treatment at each time point. The measurement conditions were as follows: Cleaning time for the instrument was set to 120 s; the interaction time with the samples was 60 s; the gas flow rate of the instrument was 1 L·min−1. The corresponding response substances of the 18 metal-oxide semiconductor chemical sensors were as follows: S1: Propane, Natural Gas, Aerosols; S2: Alcohol, Aerosols, Isobutylene, Formaldehyde; S3: Ozone; S4: Hydrogen Sulfide; S5: Ammonia, Methylamine, Ethanolamine; S6: Toluene, Xylene, Ethanol, Hydrogen, Other Organic Vapors; S7: Methane, Natural Gas, Sewer Gas; S8: Propane, Liquefied Gas; S9: Toluene, Formaldehyde, Benzene, Alcohol, Xylene; S10: Hydrogen; S11: Liquefied Gas, Alkanes, Olefins; S12: Liquefied Gas, Methane; S13: Methane; S14: Flammable Gases, Aerosols; S15: Aerosols, Isobutylene, Organic Esters, Fatty Acids; S16: Sulfur-containing Compounds; S17: Nitrogen-containing Compounds; S18: Esters, Ethanol, Organic Solvents.

Roots subjected to different treatment methods were evaluated for sensory qualities after fumigation for 14 d, with three roots randomly selected from each treatment method. The roots were washed and then steamed in a pot for 1 h. The steamed samples were then cut into square pieces (approximately 50−100 g) and placed in labeled trays with random codes. Sensory evaluation was conducted at room temperature (25−30 °C) by a sensory panel consisting of 25 trained-experienced panelists, students, and staff of Hainan University, male and female between the ages of 20−56 years. Panelists were provided with bottled mineral water to cleanse their palates between tastings of different treatments.

RNA extraction, isoform sequencing (Iso-Seq), and illumine sequencing

-

Dormancy and sprouting samples were collected by extracting the bud eye area with a 1 cm stainless steel punch, and inserted 1 cm beneath the skin to cut the root tissue. The samples were then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was extracted from pooled samples of each replicate. Specifically, the study examined dormancy (D-Control, D-1-MCP, D-ETH, D-ETH + 1-MCP) and sprouting (S-Control, S-1-MCP, S-ETH, S-ETH + 1-MCP) roots subjected to ethylene, 1-MCP, ethylene + 1-MCP treatments, and control treatment during the dormancy period (day 1) and at four sprouting time points (days 6, 12, 25, and 27), with three replicates for each time point.

RNA quality was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and verified through RNase free agarose gel electrophoresis. After total RNA extraction, eukaryotic mRNA was enriched by Oligo (dT) beads. The enriched mRNA was then fragmented into short fragments using fragmentation buffer and reverse-transcribed into cDNA by using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB#7530, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The purified double-stranded cDNA fragments were end-repaired, adenosine added, and ligated to Illumina sequencing adapters. The ligation reaction was purified with the AMPure XP Beads (1.0X) and amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The resulting cDNA library was sequenced using Illumina Novaseq6000 by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co (Guangzhou, China).

Transcriptomic data analysis and WGCNA analysis

-

Gene expression levels were calculated using the values of fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM), which accounts for gene length and sequencing depth differences. This method allows for direct comparison of gene expression levels across samples. Significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened from the raw count data using the DESeq2 method, with criteria of an absolute log2 (fold change) greater than 1, and an FDR value less than 0.05. Validation (qRT-PCR) of selected differentially expressed genes are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

In WGCNA analysis, weighted correlation coefficients are utilized by raising gene correlation coefficients to a power of N, ensuring that gene connections in the network follow a scale-free distribution. A hierarchical clustering tree was constructed based on these weighted correlation coefficients, with each branch representing distinct gene modules. Different colors were assigned to these modules, based on the weighted correlation coefficients of the genes. Genes were categorized by their expression patterns, with those showing similar patterns clustered into the same module.

Statistical analysis

-

Data were presented as the mean and standard deviation of at least three replicate measurements. The significance of differences (p < 0.05) and correlations were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) software, with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted for data analysis. Results were presented as the mean ± standard error (S.E.), and GraphPad Prism 10.1.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) software was used for creating graphs. Origin 2021 software (Origi-nLab, Northampton, MA, USA) was used for plotting radar charts.

-

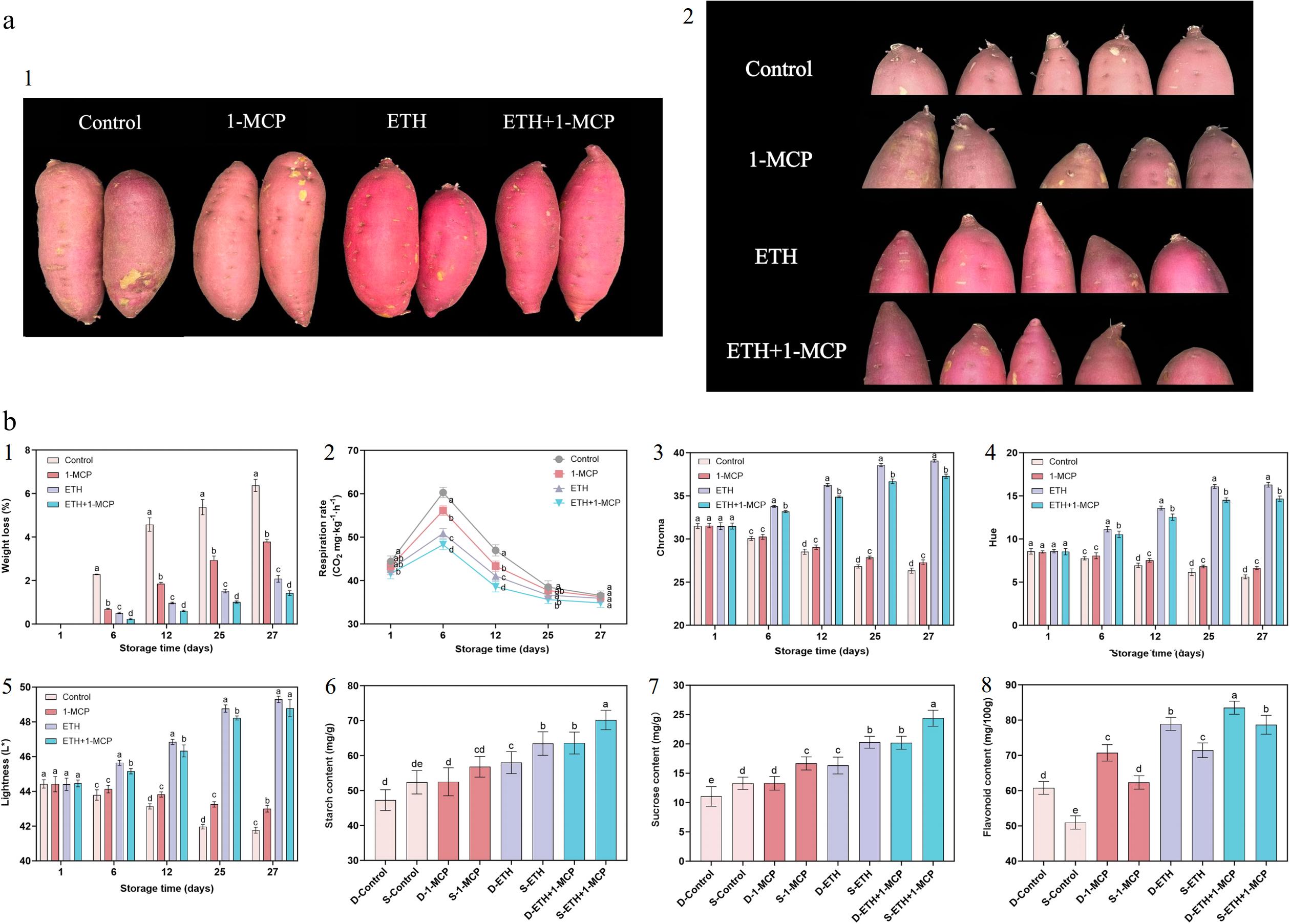

The results of these studies showed that the control group exhibited the most significant weight reduction during storage, with an initial loss of 2.28% by day 6 and a total loss of 6.37% by day 27 (Fig.1b-1). In comparison, the 1-MCP-treated sweet potato roots exhibited a lower weight loss, starting at 0.67% and increasing slightly to 3.78% after 27 d. The ETH treatment also resulted in a lower weight loss rate, beginning at 0.51% and rising to 2.08% by day 27. The most effective control of weight loss was observed in the sweet potato treated with both ETH and 1-MCP, where the initial weight loss was only 0.23%, reaching 1.42% by day 27. The 1-MCP treatment significantly enhanced the longevity of the 'Covington' variety[22], suggesting that it may possess anti-spoilage properties and reduce weight loss. Furthermore, the continuous presence of ethylene inhibited germination, while the combined treatment of ethylene and 1-MCP mitigated ethylene-induced weight loss and decay[22]. Similarly, the weight loss of the 'Bushbuck' and 'Ibees' varieties was reduced following treatment with ethylene, 1-MCP, and ETH + 1-MCP[7]. These findings are consistent with the phenomena observed in our experiments.

Figure 1.

(a) -1 Color and -2 sprout changes of Kokei No.14 sweet potato roots after exposure to 1-MCP (30 μl·L−1), ETH (200 μL·L−1), ETH + 1-MCP (200 μL·L−1 + 30 μL·L−1) after one week. (b) -1 Average percentage weight loss, -2 respiration rates, -3 chroma, -4 hue, -5 and lightness of Kokei No.14 sweet potato roots subjected to different treatments: Air (Control), 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP. -6 Changes in starch, -7 sucrose, and -8 flavonoid content in D (dormancy) and S (Sprouting) period. Each data point is a mean of three replicates with six roots. Means followed by different letters at the same sampling point indicate statistical differences according to Tukey's test (p < 0.05).

The respiration rates of all treatment groups exhibited a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing, peaking on day 6 (Fig. 1b-2). Throughout the experimental period, the control group consistently recorded the highest respiration rate, peaking at 60.28 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1 before gradually decreasing to 36.55 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1 by day 27. In contrast, the respiration rate of the 1-MCP-treated sweet potatoes was generally lower, reaching a peak of 56.14 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1 and a minimum of 36.27 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1. The ethylene-treated group peaked at 50.87 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1, decreasing to 35.91 mg·kg−1·h−1 on day 27. The ETH + 1-MCP treatment group maintained the lowest respiration rates, peaking at 48.26 CO2 mg·kg−1·h−1. The results indicate that all three treatments, 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP, effectively inhibited the respiration of sweet potatoes, with the ETH + 1-MCP treatment demonstrating the strongest inhibitory effect. In the storage of the 'Covington' variety, the application of 1-MCP significantly reduced respiration, leading to decreased weight loss and spoilage. This aligns with our experimental findings, confirming that 1-MCP is an effective method for lowering the respiration rate of sweet potatoes[22]. In comparison to the control group, respiration of 'Bushbuck' and 'Ibees' varieties were significantly inhibited following 1-MCP (625 nL−1) treatment, while ethylene-treated sweet potatoes (10 μL−1) exhibited the highest respiration rates. The ETH + 1-MCP (625 nL−1 + 10 μL−1) treatment also enhanced the respiration rates[7]. For the 'Owairaka Red' variety, exposure to 1-MCP (1 μL·L−1), ethylene (10 μL·L−1), or their combinations increased respiration rates. Conversely, the 'Clone 1820' variety showed inhibited respiration with 1-MCP treatment, while its respiration rate significantly increased with ethylene and combined treatments[18]. These differing outcomes may be attributed to variations in experimental methods and environments, treatment concentrations, and sweet potato varieties, involving multiple physiological pathways.

The experimental results indicated that ethylene treatment most significantly enhanced the color Chroma and hue angle of sweet potatoes, followed by the ETH + 1-MCP treatment, which also improved the color slightly. In contrast, sweet potatoes treated with 1-MCP alone exhibited color characteristics most similar to the control group, with minimal changes in color lightness, Chroma, and hue angle. This study demonstrated significant differences in color lightness and Chroma among the various treatment conditions (Fig. 1b-3, b-5). Specifically, ETH-treated sweet potatoes displayed the brightest and most uniform color, showing the greatest effect on color saturation (Fig. 1a-1, a-2). The sample group receiving ETH + 1-MCP treatment also reflected a similar positive trend in color lightness and Chroma. Conversely, the control and 1-MCP-treated samples showed a slight decreasing trend in both lightness and Chroma during storage. Figure 1b-4 illustrates the changes in hue angle under different treatment conditions. In the ETH treatment group, the hue angle continuously increased from the first day of storage. Similarly, the ETH + 1-MCP group exhibited an increasing trend in hue angle. In contrast, the control and 1-MCP-treated groups displayed a slight decrease, with the hue angle remaining relatively stable throughout the storage period for the 1-MCP treatment.

Tomatoes treated with stored ethylene slightly affected the surface color of the fruit during air storage. Fruits stored for longer periods appeared redder than those stored for shorter durations. This observation aligns with our experimental results, which showed that ethylene-treated sweet potatoes exhibited the most vibrant and uniform color[23]. Fresh broccoli treated with 1-MCP showed no significant color changes throughout storage. Exposure to 1-MCP before storage helped preserve the green color of the tissue, likely due to the inhibition of enzymes involved in chlorophyll degradation[24]. Regardless of treatment, the colorimetric angle of cucumber rinds significantly decreased, leading to gradual decolorization during storage. While the rate of decolorization temporarily increased upon exposure to ethylene, it did not differ from that of cucumbers stored in air or in 1-MCP + air conditions after transfer to air. Notably, cucumbers treated with 1-MCP + air remained greener after day 7 compared to those stored in air only[25]. At the end of the storage period, the control eggplant showed significant reductions in brightness and chroma angle, with the color changing from bright green to yellowish brown. In contrast, 1-MCP-treated eggplant sepals exhibited significantly lower reductions in both lightness and chroma angle[26]. Overall, these findings suggest that 1-MCP has minimal effect on the color of fruits and vegetables, which is consistent with the phenomena observed in our experiments.

Hardness and TPA changes during Kokei No.14 root storage

-

The results of these studies indicate that different sweet potato varieties, fruits, and treatments significantly affect texture, leading to considerable complexity in the results. Textural characteristics serve as a comprehensive framework for accurately assessing sweet potato quality[27]. Hardness is a key aspect of these characteristics typically, sweet potatoes with high raw food quality are less hard[28]. On day 1 after treatment, there were no significant differences in hardness values among the treatment groups (Table 1). However, from day 6 to day 27 of storage, the ETH + 1-MCP treatment group exhibited the highest hardness value, significantly different from the control group. In contrast, the hardness difference between the 1-MCP-treated group and the ETH-treated group was not significant. Throughout the storage period, the ETH + 1-MCP group consistently showed slightly higher hardness than the other treatment groups, indicating its effectiveness in maintaining sweet potato hardness. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of adhesive force and adhesiveness data over the 27-d storage period revealed no significant differences among the four treatment groups. The control group displayed the highest cohesiveness on day 1. From day 6 to day 27, cohesiveness levels among the groups converged and were no longer significantly different. The control group had the lowest springiness value on day 1; from day 6 to day 25, no significant differences in springiness were observed among the treatment groups. However, on day 27, the control group exhibited higher springiness than the others. As storage time increased, springiness in the control group improved, while it decreased in the ETH and ETH+1-MCP groups. Gumminess showed no significant differences among groups from day 1 to day 25, remaining relatively stable during this period. On day 27, the control group displayed significantly higher gumminess than the ETH + 1-MCP-treated group, while no significant differences in gumminess were found between the ETH and 1-MCP groups. Regarding chewiness, the ETH-treated group had significantly higher chewiness than the control group on day 1. There were no significant differences in chewiness between the 1-MCP and ETH + 1-MCP groups compared to the others. From day 6 to day 25, chewiness differences among the four treatment groups were not significant, indicating consistent effects of the treatments. On day 27, the control group exhibited significantly higher chewiness than the ETH-treated and ETH+1-MCP-treated groups, which had relatively lower chewiness.

Table 1. Texture parameters of KoKei No.14 organic sweet potato roots affected by different treatments.

Storage

time (d)Treatment Hardness (N) Adhesive force (N) Adhesiveness (mJ) Cohesiveness (ratio) Springiness (mm) Gumminess (N) Chewiness (mj) 1 Control 27.22 ± 1.82a −0.07 ± 0.00a 0.0069 ± 0.0014a 0.83 ± 0.03a 1.03 ± 0.08b 53.32 ± 4.16a 54.94 ± 5.45b 1-MCP 27.93 ± 1.62a −0.07 ± 0.00a 0.0077 ± 0.0010a 0.79 ± 0.03b 1.23 ± 0.09a 67.97 ± 23.09a 84.22 ± 31.72ab ETH 28.27 ± 2.99a −0.06 ± 0.02a 0.0080 ± 0.0024a 0.79 ± 0.01b 1.28 ± 0.04a 82.04 ± 17.13a 105.25 ± 24.26a ETH + 1-MCP 28.91 ± 2.11a −0.06 ± 0.04a 0.0107 ± 0.0035a 0.81 ± 0.01ab 1.18 ± 0.11ab 62.52 ± 12.21a 73.39 ± 12.34ab 6 Control 26.54 ± 2.02b −0.09 ± 0.09a 0.0088 ± 0.0077a 0.81 ± 0.02a 1.34 ± 0.12a 53.32 ± 4.16a 148.32 ± 50.76a 1-MCP 27.17 ± 1.8ab −0.04 ± 0.00a 0.0046 ± 0.0006a 0.78 ± 0.01a 1.24 ± 0.09a 67.97 ± 23.09a 77.16 ± 41.13a ETH 27.65 ± 0.62ab −0.04 ± 0.00a 0.0035 ± 0.0007a 0.79 ± 0.03a 1.30 ± 0.15a 82.04 ± 17.13a 108.27 ± 68.39a ETH + 1-MCP 28.62 ± 1.31a −0.06 ± 0.04a 0.0059 ± 0.0003a 0.82 ± 0.05a 1.47 ± 0.11a 62.52 ± 12.21a 165.92 ± 38.11a 12 Control 25.98 ± 0.81b 0.00 ± 0.00a 0.0123 ± 0.0045a 0.81 ± 0.05a 1.35 ± 0.14a 140.36 ± 11.22a 189.82 ± 35.18a 1-MCP 26.76 ± 2.71ab −0.01 ± 0.02a 0.0117 ± 0.0018a 0.79 ± 0.02a 1.23 ± 0.01a 106.15 ± 25.54a 129.95 ± 31.61a ETH 27.27 ± 1.18ab −0.01 ± 0.02a 0.0102 ± 0.0004a 0.79 ± 0.03a 1.20 ± 0.12a 110.72 ± 19.78a 133.82 ± 31.3a ETH + 1-MCP 28.28 ± 1.30a −0.01 ± 0.02a 0.0100 ± 0.0008a 0.80 ± 0.06a 1.24 ± 0.01a 123.06 ± 32.03a 152.73 ± 40.26a 25 Control 25.19 ± 1.80b −0.06 ± 0.04a 0.0297 ± 0.0418a 0.78 ± 0.08a 1.32 ± 0.08a 76.17 ± 14.36a 101.02 ± 24.77a 1-MCP 26.13 ± 1.54ab −0.03 ± 0.02a 0.0046 ± 0.0024a 0.81 ± 0.04a 1.35 ± 0.16a 109.22 ± 24.33a 150.09 ± 46.56a ETH 26.89 ± 1.97ab −0.05 ± 0.02a 0.0115 ± 0.0134a 0.78 ± 0.01a 1.08 ± 0.07a 75.02 ± 4.09a 81.18 ± 3.73a ETH + 1-MCP 27.66 ± 1.43a −0.05 ± 0.02a 0.0054 ± 0.0014a 0.78 ± 0.06a 0.90 ± 0.56a 95.51 ± 42.86a 122.65 ± 64.82a 27 Control 24.47 ± 1.79b −0.03 ± 0.02a 0.0070 ± 0.0026a 0.80 ± 0.02a 1.27 ± 0.20a 123.59 ± 33.62a 146.21 ± 41.82a 1-MCP 25.37 ± 3.95ab −0.01 ± 0.02a 0.0103 ± 0.0034a 0.77 ± 0.04a 1.23 ± 0.04ab 99.00 ± 15.43ab 121.72 ± 22.04ab ETH 25.59 ± 1.62ab −0.06 ± 0.04a 0.0048 ± 0.0022a 0.77 ± 0.03a 1.04 ± 0.08b 78.25 ± 20.68ab 82.20 ± 28.66b ETH + 1-MCP 27.13 ± 1.51a −0.04 ± 0.04a 0.0079 ± 0.0043a 0.74 ± 0.03a 1.02 ± 0.05b 74.23 ± 14.84b 76.19 ± 18.12b Means with the same letters in a column are not significantly different (p < 0.05) by Duncan's multiple range test. ± denotes standard deviation. The experimental results showed that treatments with 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP had complex effects on the texture of sweet potatoes. Overall, the texture of treated sweet potatoes did not significantly differ from that of the control group. The treatments affected adhesive force, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, springiness, gumminess, and chewiness, but these effects were not significant. All three treatments increased sweet potato hardness, with ETH + 1-MCP showing the best retention of hardness. Texture measurements taken for 81 sweet potato varieties showed that root hardness ranged from 72.82 N to 142.26 N, with a mean value of 105.86 N. Root adhesiveness varied from 0.91 mJ (Xu yam 18) to 12.27 mJ (Soya yam 25), while root cohesiveness ranged from 0.17 (Ning Zhi yam 6) to 0.29 (Xu yam 18). Root springiness was measured from 3.92 mm (Wan A4921) to 7.78 mm (Luo Purple yam 6). Additionally, root gumminess ranged from 15.80 N (Fu sweet 1) to 29.68 N (Xu yam 8), and root chewiness varied from 73.96 mJ (Wan A4921) to 172.89 mJ (Xu yam 18)[28]. Similarly, the texture parameters of 35 sweet potato varieties at harvest were examined. The mean values for hardness, adhesion, cohesion, elasticity, gumminess, and chewiness were 104.35 N, −4.91 J, 0.20, 6.14 mm, 20.91 N, and 129.62 J, respectively[29]. During storage, there were no significant differences in hardness and elasticity between 'Saturna', 'Russet Burbank', and 'Marfona' potatoes, regardless of whether they were treated with 1-MCP. However, 'Estima' tubers showed exceptions in hardness and apparent elasticity between non-1-MCP and 1-MCP treated groups. Furthermore, 'Marfona' tubers stored continuously in ethylene exhibited greater resilience at the end of storage compared to air-treated tubers[30]. The effects of 1-MCP and ethylene on textural characteristics were influenced by factors such as respiration rate, cell wall composition, enzyme activity, and corresponding gene expression, all of which were regulated integrally[31].

Germination rate and germination length changes during Kokei No.14 root storage

-

The findings highlight the inhibitory effects of 1-MCP and ethylene on sweet potato germination, with ETH + 1-MCP showing a particularly strong effect, especially during late storage (Fig. 1a-2). These results provide important insights for optimizing sweet potato storage and transportation practices. The impact of various treatments (Control, 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP) on the average number and length of sweet potato sprouts was assessed on poststorage days 1, 6, 12, 25, and 27 (Table 2). The data revealed that except for the ETH + 1-MCP treatment, the average sprout count and length increased over storage time, with the most notable changes occurring on days 25 and 27. Initially, all sweet potatoes were dormant on day 1. By day 6, the control group exhibited significant sprouting, and the 1-MCP group began to show sprouts as well. Throughout the study, the 1-MCP treatment resulted in fewer and shorter sprouts compared to the control, effectively inhibiting sprouting by blocking the ethylene receptor binding site[32].

Table 2. Average sprout number and average sprout length of Kokei No.14 organic sweet potato roots after 27 d (25 °C and 90% RH).

Storage

time(d)Treatment Average number

of sproutsAverage sprout

length (mm)1 Control 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 ± 0.00 1-MCP 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 ± 0.00 ETH 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 ± 0.00 ETH + 1-MCP 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 ± 0.00 6 Control 2.67 ± 0.58a 3.33 ± 1.47a 1-MCP 1.00 ± 0.00b 0.79 ± 0.69b ETH 0.00 ± 0.00c 0.00 ± 0.00b ETH + 1-MCP 0.00 ± 0.00c 0.00 ± 0.00b 12 Control 5.33 ± 0.58a 4.36 ± 1.87a 1-MCP 2.33 ± 0.58b 2.46 ± 0.53b ETH 0.33 ± 0.58c 0.65 ± 0.03c ETH + 1-MCP 0.00 ± 0.00c 0.00 ± 0.00c 25 Control 6.00 ± 0.00a 5.28 ± 1.83b 1-MCP 4.33 ± 1.15b 4.03 ± 0.80b ETH 1.67 ± 0.58c 1.86 ± 0.04c ETH + 1-MCP 0.67 ± 0.58c 0.40 ± 0.16c 27 Control 6.00 ± 0.00a 6.07 ± 1.58a 1-MCP 4.67 ± 1.15b 5.34 ± 0.95a ETH 2.00 ± 0.00c 2.73 ± 0.05b ETH + 1-MCP 1.00 ± 0.00c 1.08 ± 0.14b Means bearing the same superscript within the same column are not significantly different at the 5% level (p < 0.05). The 'BRS Rubissol' variety treated with 1-MCP (1 mg·L−1) reduced sprout formation by 69%[33]. Similarly, 1-MCP inhibited germination in various sweet potato varieties, notably reducing sprouting in 'Evangeline' and 'Beauregard' with 1-MCP (1−2 μL·L−1) treatment in three and two out of four experiments, respectively[34]. On day 12, the ethylene treatment group began sprouting, while the ETH + 1-MCP group remained dormant. By day 25, both the control and 1-MCP treatments exhibited a marked increase in sprout number and length, with the ETH + 1-MCP group also beginning to sprout. On day 27, the control treatment peaked in sprout number and length, while the ETH and ETH + 1-MCP treatments demonstrated superior sprout suppression, significantly differing (p < 0.05) from the other groups. Control roots of the 'Ibees' variety germinated after one week, with average sprout lengths increasing to 3.3, 10.6, 15.8, and 28.6 mm after 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks, respectively. In contrast, 1-MCP (625 nL·L−1) treated roots germinated after two weeks, ethylene (10 μL·L−1) treated roots germinated after three weeks, and the combination of 1-MCP + ethylene (625 nL·L−1 + 10 μL·L−1) germinated after four weeks, all showing significantly fewer and shorter sprouts than the control[7]. There was no significant difference in germination between the control and 1-MCP (1 μL·L−1) treated 'Owairaka Red' variety after four weeks. However, continuous ethylene (10 μL·L−1) and ethylene + 1-MCP (10 μL·L−1 + 1 μL·L−1) treatments entirely prevented germination[35].

Starch, sucrose, and flavonoid content during Kokei No.14 root storage

-

Our study reveals a notable increase in starch content across all treatment groups after germination (Fig. 1b-6), with the ETH + 1-MCP group demonstrating the most significant rise and the highest starch levels. Similarly, sucrose content exhibited a similar trend (Fig.1b-7), increasing in all groups after sprouting, with the ETH + 1-MCP group consistently maintaining the highest levels. In contrast, flavonoid content decreased across all treatments following germination (Fig. 1b-8); however, the ETH + 1-MCP group retained the highest flavonoid levels both before and after germination.

After five weeks of ethylene (10 μL·L−1) and 1-MCP (1 mg·L−1) treatment at 25 °C and 90% relative humidity, the starch content of the 'BRS Rubissol' decreased, while flavonoid content increased[36]. This decrease in starch concentration from dormancy to germination suggests distinct physiological and metabolic pathways between potatoes and sweet potatoes, accounting for their differing responses in starch synthesis and degradation[37]. These variations may stem from differences in variety, treatment concentrations, and experimental methodologies. Moreover, our experiments confirmed that sucrose content in sweet potatoes changes significantly during storage, typically increasing over time[38]. Notably, all treatment groups displayed enhanced sucrose levels, with the ETH + 1-MCP group sustaining the highest sucrose content that aligns with observations in other cultivars. 'Owairaka Red' exhibited higher sucrose content after 4 to 12 weeks of storage at 25 °C and 80%−90% relative humidity when treated with ethylene (10 μL·L−1) and 0.14% 1-MCP (86.9 mg) powder[18].

Electronic nose and sensory analysis during Kokei No.14 root storage

-

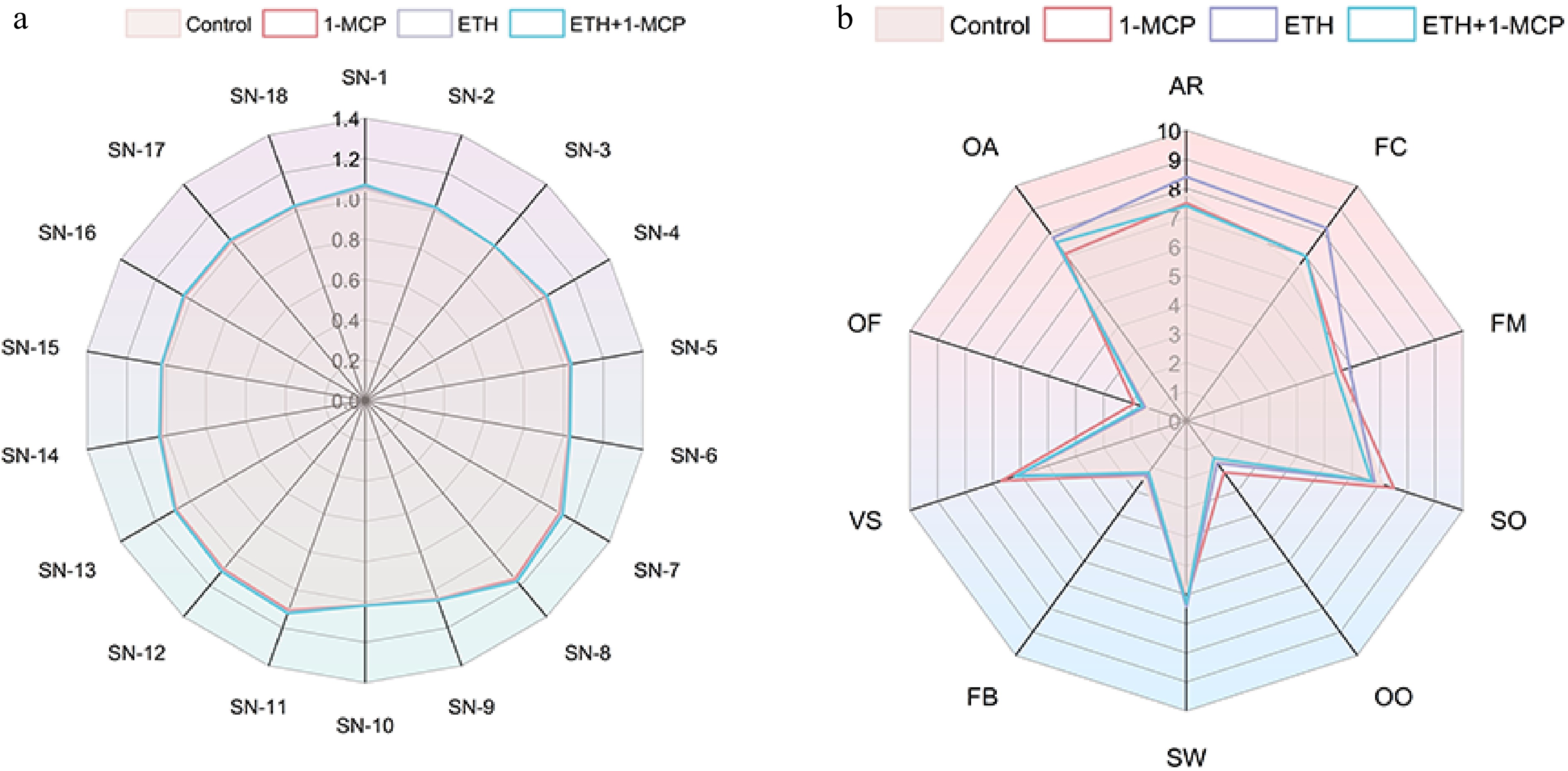

The radar chart (Fig. 2a) shows that the odor response values of sweet potato flesh exhibited no significant changed during the storage period. The results indicated that treatments with 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP had minimal impact on the volatile compounds of sweet potatoes, effectively preserving the original aroma.

Figure 2.

(a) Radar chart of electronic nose results of Kokei No.14 sweet potato under treatments (Control, 1-MCP, ETH, ETH + 1-MCP). Values were the means of three replicates. (b) Sensory quality evaluation of sweet potato roots fumigated for 14 d under different treatments (Control, 1-MCP, ETH, ETH + 1-MCP).

Differences in taste quality results may be from variations in sweet potato variety, cooking methods, treatment concentrations, and environmental conditions. Additionally, the subjectivity of sensory assessments and differing criteria among evaluation groups can further influence results. This study conducted a comprehensive sensory evaluation of sweet potatoes subjected to 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP treatments. Notably, the 1-MCP treatment significantly enhanced the viscosity (VS) and sweet potato odor (SO) (Fig. 2b). However, samples treated only with 1-MCP scored lower in appearance (AR) and overall assessment (OA). 'Russet Burbank' potatoes pretreated with 1-MCP maintained a lighter frying color similar to untreated tubers, suggesting that 1-MCP could be a potential tool for preserving fried potato color during extended storage[39]. In contrast, ethylene treatment resulted in significant improvements in appearance (AR), flesh color (FC), firmness (FM), and sweetness (SW), but negatively affected off-flavor (OF) and off-odor (OO). In 'Centennial' sweet potato roots, exposure to 10 ppm ethylene led increased phenolic compounds and polyphenol oxidase activity, leading to discoloration and undesirable flavors, along with a decrease in the hardness of baked roots[40]. This aligns with our findings that ethylene increases sweet potato off-odors, despite also improving scores for appearance (AR), flesh color (FC), and firmness (FM) of sweet potatoes. Additionally, ethylene treatment significantly elevated sucrose levels in 'NCCov II' sweet potatoes[41], supporting our results that showed increased sweetness (SW) from ethylene treatment alone. However, the combined ETH + 1-MCP treatment slightly negatively impacted firmness (FM), sweet potato odor (SO), appearance (AR), and overall assessment (OA). While ethylene treatment darkened potato chips in 'Shepody' and 'Russet Burbank', but 1-MCP effectively controlled this ethylene-induced darkening[42]. This contrasts with our observations of ethylene's positive effects on sweet potato appearance (AR) and flesh color (FC), and the negative impact of the ETH + 1-MCP group on appearance (AR).

Transcriptome analysis of Kokei No.14 root at different storage stages

-

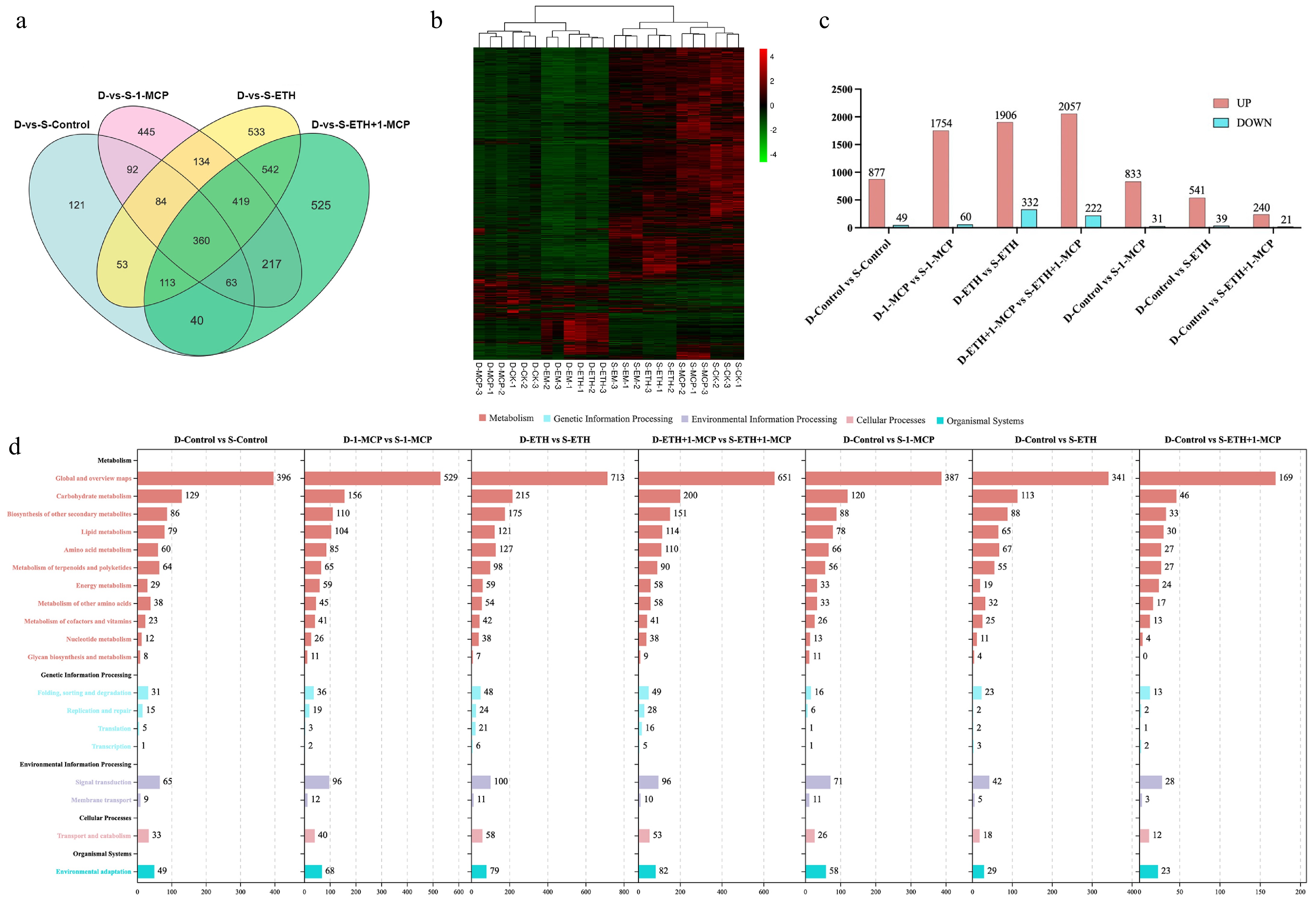

The number of commonly differentially expressed genes across various treatment groups were identified by Venn analysis. A total of 84 genes were commonly expressed between the D-vs-S-Control, D-vs-S-1-MCP, and D-vs-S-ETH groups. 419 genes were commonly expressed among the D-vs-S-1-MCP, D-vs-S-ETH, and D-vs-S-ETH + 1-MCP groups. Additionally, 63 genes were shared between the D-vs-S-Control, D-vs-S-1-MCP, and D-vs-S-ETH + 1-MCP groups. One hundred and thirteen genes were identified as commonly expressed between the D-vs-S-Control, D-vs-S-ETH, and D-vs-S-ETH + 1-MCP groups (Fig. 3a). To explore variations in transcriptome sequencing data, we conducted a differential gene expression clustering analysis on sweet potatoes under four distinct treatment conditions: Control, 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP, focusing on dormancy and sprouting (Fig. 3b). This analysis revealed significant disparities between the states of dormancy and sprouting.

Figure 3.

Transcriptome analysis of Kokei No.14 sweet potato roots at different postharvest stages. (a) Venn diagram for gene expression analysis under different treatments of roots, (b) heat map of the DEGs during root storage, (c) numbers of DEGs in the pair-wise comparisons, (d) KEGG pathway analysis of clustered DEGs in 19 categories. The X-axis indicates the number of DEGs, and the Y-axis indicates KEGG classification.

The data indicated that different treatment methods significantly impact gene expressions in sweet potatoes. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are associated with the physiological responses of sweet potatoes to these treatments. After filtering (Fold Change > 5, FDR < 0.05), the numbers of DEGs under various treatment conditions are shown in Fig. 3c. The bar chart compares gene expression changes between different treatment groups, with red representing up-regulated genes (UP), and blue representing down-regulated genes (DOWN). In the comparison between the non-treated sweet potato in dormancy and sprouting (D-Control vs S-Control), 877 genes were up-regulated and 49 were down-regulated. After treatment with 1-MCP, the comparison between dormancy and sprouting in sweet potatoes (D-1-MCP vs S-1-MCP) showed 1,754 up-regulated genes and 60 down-regulated genes. After ethylene treatment, the comparison (D-ETH vs S-ETH) showed 1,906 up-regulated genes and 332 down-regulated genes. In the combined treatment with ethylene and 1-MCP (D-ETH+1-MCP vs S-ETH + 1-MCP), 2,057 genes were up-regulated genes, and 222 were down-regulated, indicating that the ETH + 1-MCP treatment further influenced gene expressions. The comparison between the control group in dormancy and the 1-MCP treated sweet potatoes in sprouting (D-Control vs S-1-MCP) showed 833 up-regulated genes and 31 down-regulated genes. Comparing the control group in dormancy to ethylene-treated sweet potatoes in sprouting (D-Control vs S-ETH) demonstrated 541 up-regulated genes and 39 down-regulated genes. The comparison between the control group in dormancy and the ETH + 1-MCP treated groups in sprouting (D-Control vs S-ETH + 1-MCP) revealed 240 up-regulated genes and 21 down-regulated genes.

KEGG annotation identified the specific pathways and mechanisms by which sweet potatoes respond to 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP. The KEGG pathway database records biomolecule interactions within cells and their variations in specific organisms, enabling a deeper understanding of the biological functions and interactions of related genes[29]. Comparisons were made between the dormancy state of sweet potato groups and their sprouting state after treatment, specifically contrasting the dormancy of the control group with the sprouting states of the treated groups. Differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in metabolic pathways, including carbohydrate metabolism, secondary metabolism biosynthesis, lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and the metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides (Fig. 3d). In the environmental information process, differentially expressed genes were most enriched in the plant signal transduction process.

Analysis of WGCNA

-

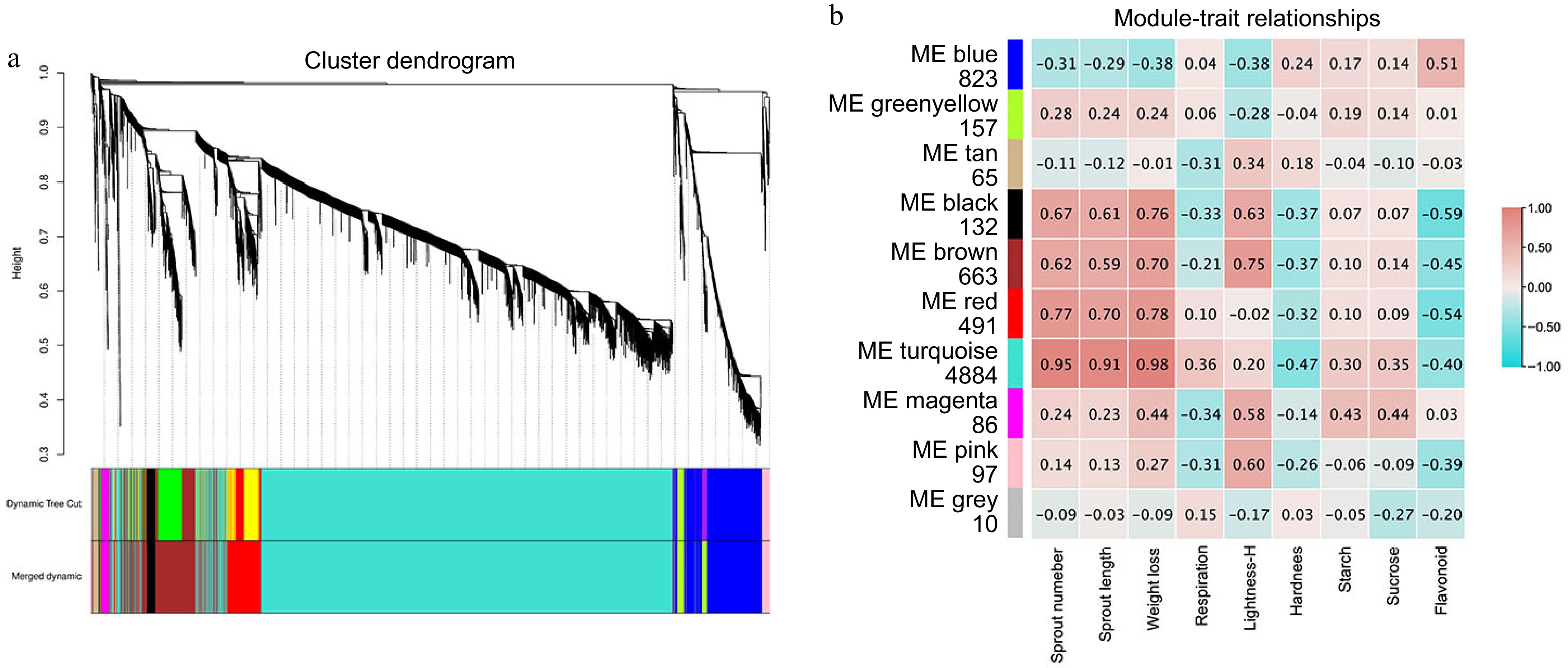

Genes with similar expression patterns are typically involved in related biological processes. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) serves as a valuable tool for examining gene sets with analogous expression patterns[43]. To identify potential regulatory networks associated with sweet potato root dormancy and sprouting in postharvest, we performed WGCNA on a curated set of genes. Low-expression genes (FPKM < 1) were excluded to minimize false positives, resulting in a total of 7,408 genes for analysis (Fig. 4a). Dynamic hierarchical tree cutting revealed 10 modules with similar gene expression patterns. The turquoise module contained the highest number of genes (4,884), while the grey module had the fewest (10) (Fig. 4b). Genes in the turquoise module were positively correlated with sprout number, sprout length, weight loss, respiration, lightness-H, starch, and sucrose. This correlation suggests that the genes in the turquoise module are closely related to these physiological indicators in sweet potatoes.

Figure 4.

Analysis of WGCNA during storage in Kokei No.14 sweet potato roots. (a) Clustering dendrogram of 7408 DEGs, the color rows provide a simple visual comparison of module assignments based on the dynamic hybrid branch cutting method, (b) number of genes contained in each module, and the correlation coefficient between phenotypic traits and module eigengenes presented with a color scale with red and blue representing positive and negative correlations, respectively.

Key transcription factors in differential treatment regulation

-

Transcription factors (TFs) are key regulatory genes that control the spatial and temporal expression of structural genes[44]. In our study, we examined the genes encoding TFs within annotated singletons, identifying 2,069 TFs across more than 40 families, with AP2/ERF, MYB, bHLH, and WRKY being the most prevalent (Supplementary Table S1). The AP2/ERF superfamily is one of the largest families of plant-specific transcription factors and plays crucial roles in various biological processes[45]. MYB transcription factors were among the largest protein families in plants[46]. WRKY transcription factors were essential for regulating plant growth, development, and stress responses[47]. Additionally, bHLH TFs have been shown to be critical regulators in signal transduction networks, influencing diverse developmental and metabolic processes, such as photomorphogenesis, flowering, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, which are important for enhancing plant tolerance to adverse conditions[48].

In this experiment, we identified for all differentially regulated transcription factors in sweet potatoes during dormancy and sprouting across various treatment groups including D-Control vs S-Control, D-1-MCP vs S-1-MCP, D-ETH vs S-ETH, and D-ETH + 1-MCP vs S-ETH + 1-MCP. These comparisons predominantly consisted of AP2/ERF, bHLH, and MYB, with 180, 269, 336, and 306 DEGs encoding TFs identified, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Differential expression of TFs between control groups after germination and dormancy under different treatments. In the comparisons of D-Control vs S-1-MCP, D-Control vs S-ETH, and D-Control vs S-ETH + 1-MCP, we identified 133 DEGs (predominantly AP2/ERF, WRKY, and MYB), 94 DEGs (predominantly bHLH, MYB, and AP2/ERF), and 50 DEGs (predominantly WRKY, AP2/ERF, and GRAS) encoding TFs, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, we cross-compared DEGs encoding TFs in sweet potatoes between dormancy and sprouting after different treatments to explore unique and common TFs. The results indicated that the TFs activated during the sprouting process were primarily specific to different treatment methods, suggesting that 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH+1-MCP may employ different regulatory factors that target various structural genes.

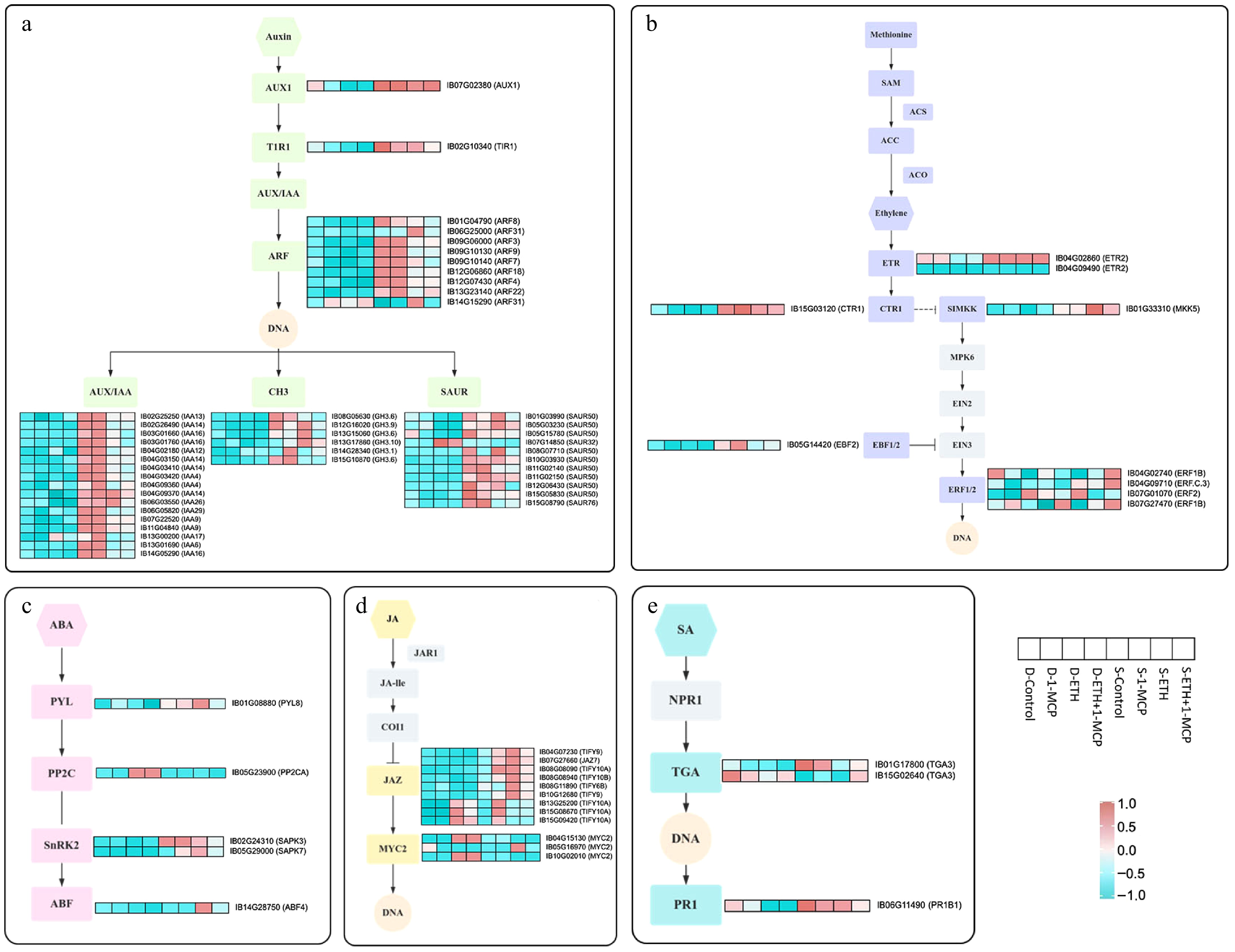

Gene regulatory network associated with phytohormones

-

These treatments affect key gene expressions within hormone signaling pathways, providing critical insights into hormone regulation in post-harvest produce. To illustrate the changes in DEGs associated with hormone signaling in sweet potato roots, we annotated and visualized the expression patterns of DEGs across five distinct hormone signaling pathways using heat maps (Fig. 5). We identified 45 DEGs in the auxin signaling cascade, including genes encoding AUX1, TIR1, AUX/IAA, ARF, GH3, and SAUR, most of which were upregulated germination in control roots. In contrast, ETH and ETH + 1-MCP treatments significantly suppressed the expression of these genes throughout germination.

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of DEGs associated with different plant hormones signal transduction, including (a) Auxin, (b) Ethylene, (c) Abscisic acid (ABA), (d) Jasmonic acid (JA), and (e) Salicylic Acid (SA). Rows in the heat map represent screened DEGs, and the columns indicate different samples (D-Control, D-1-MCP, D-ETH, D-ETH + 1-MCP, S-Control, S-1-MCP, S-ETH, and S-ETH + 1-MCP). The color gradient, ranging from blue through white to red, represents low, middle, and high values of the FPKM value. The denser the red color, the more expression is up-regulated, while the denser the blue color, the more expression is down-regulated.

In the ethylene signaling pathway, we detected nine DEGs, including one ETR-encoding gene and three ERF1/2-encoding genes, which showed significant upregulation in ETH + 1-MCP-treated roots compared to controls. The ABA signaling pathway revealed five DEGs, among which a PP2C-encoding gene was significantly downregulated following treatments with 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP. In the JA signaling pathway, 12 DEGs were identified, including nine JAZ-encoding genes that were upregulated by 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP treatments, and three MYC2-encoding genes, two of which were downregulated by ETH and ETH + 1-MCP. Additionally, three DEGs in the SA signaling pathway were found, with one gene downregulated by 1-MCP and ETH treatments.

Transcriptome analysis of the potato variety 'Favourita' after ethylene treatment revealed numerous DEGs in the ethylene signaling pathway, particularly those encoding ETR and ERF1/2, which were upregulated. Conversely, ethylene treatment downregulated genes in the auxin pathway that regulate cell expansion and growth, such as AUX1, AUX/IAA, ARF, GH3, and SAUR. Additionally, ABA and gibberellin signaling appeared less susceptible to ethylene's influence, suggesting a limited role in bud inhibition[20]. Quantified hormone levels in potato cultivars 'Marfona' and 'Estima' after ethylene and 1-MCP treatments revealed an increase in ABA levels in response to ethylene, which was counteracted by 1-MCP. While increased ABA may delay dormancy, the inhibition by 1-MCP did not significantly affect germination[49]. Transcriptomic analysis of papaya fruits treated with ethylene, 1-MCP, and control conditions revealed that 1-MCP inhibits EIN4 and upregulates EBF2, potentially reducing ethylene sensitivity. The differential expression of genes in ABA, cytokinin, and auxin pathways varied across treatments[50]. Ethylene promoted durian ripening, while 1-MCP inhibited this process, with maturation mediated by DzETR2 and associated transcription factors[51]. ETH and 1-MCP treatments are pivotal in modulating storage quality and germination in sweet potatoes and other crops synthesizing these findings with our study.

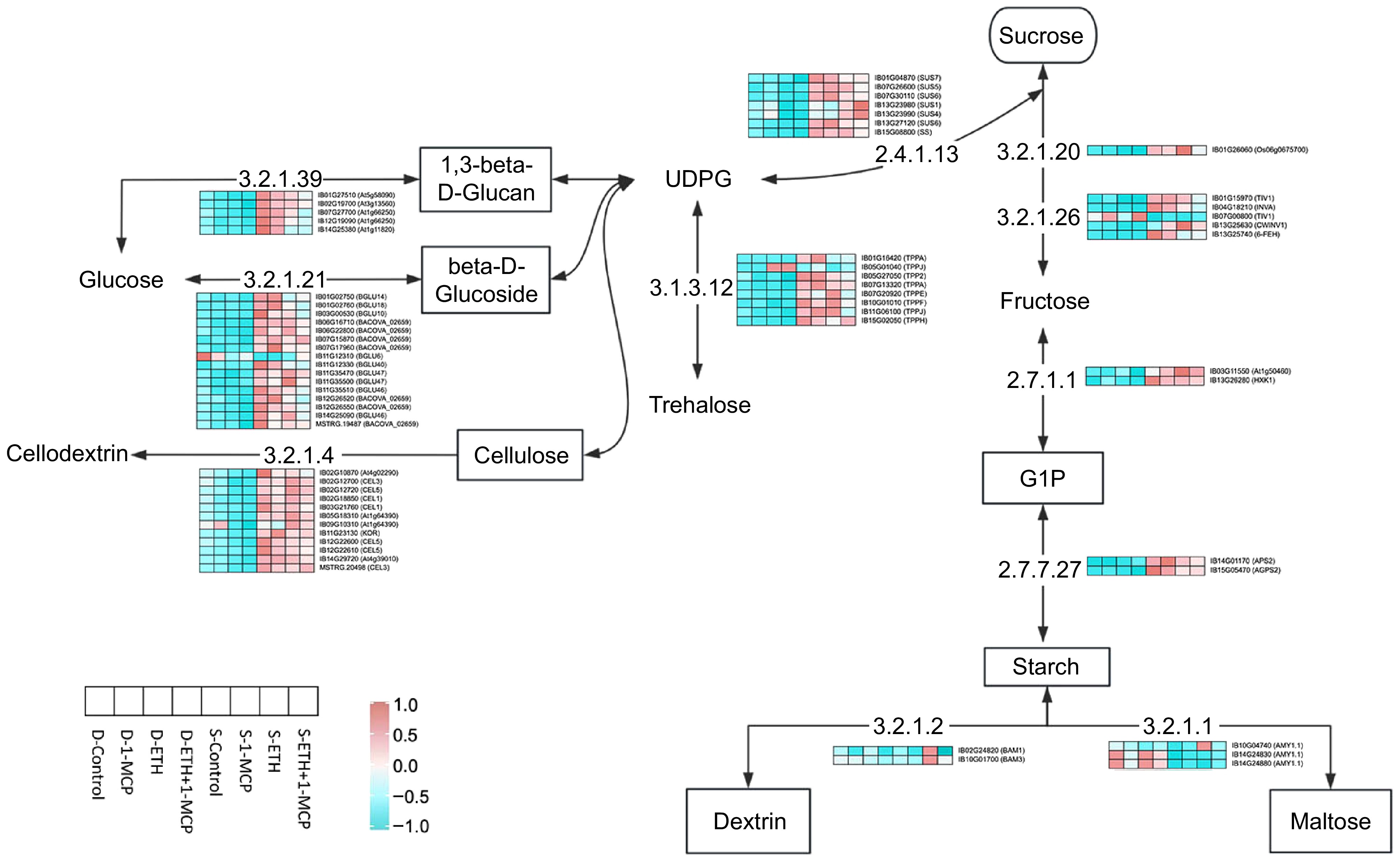

Gene regulatory network associated with starch and sucrose metabolism

-

In this study, we investigated sugar metabolic pathways and their impact on starch and sucrose content. The results (Fig. 1b-6, b-7) indicated that ETH and ETH + 1-MCP treatments significantly increased starch and sucrose during sweet potato germination. Specifically, 1-MCP treatment enhanced starch and sucrose content, with an upregulation of sugar metabolism-related genes. In contrast, the control group showed lower starch and sucrose content during dormancy and germination. In the metabolic process, glucose is converted into 1,3-beta-D-glucan by endo-1,3-beta-glucanase (Fig. 6). This compound is then transformed into beta-D-glucoside by starch synthase and further converted into cellulose by endo-1,4-beta-glucanase. Additionally, trehalose is metabolized into glucose by trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and subsequently converted into sucrose by sucrose-synthase (EC 2.4.1.13), a crucial precursor for synthesizing additional sugars, including trehalose[52]. Sucrose readily breaks down into glucose and fructose, with the latter being phosphorylated by starch phosphorylase to produce glucose-1-phosphate (GIP), a key precursor in starch synthesis. Starch serves as the primary energy reserve in root crops and is rapidly mobilized during sweet potato germination. Sucrose decomposes into glucose and fructose[53], which are then processed glycolytically to generate ATP, essential for germination and sprout growth. Following treatment with 1-MCP, ETH, and ETH + 1-MCP, the expression of numerous genes in sweet potatoes remained low during dormancy but significantly increased during the budding stage, exceeding dormancy levels. Notably, the expression of AMY, which encodes alpha-amylase, was higher during dormancy than during budding, suggesting a unique role that is independent of sucrose levels. BAM, another alpha-amylase inhibitor, showed elevated expression only during the budding stage in response to ETH treatment, indicating a complex regulation of starch metabolism that is not solely dependent on sucrose content. A positive correlation between gene expression and starch content was established across all treatment groups post-germination. 1-MCP significantly reduced the expression of genes involved in starch and sucrose metabolism, as well as respiration, contrasting with the upregulation caused by ethylene[54]. Potato cultivars 'VR808' and 'Shelford' exhibited accumulation of sucrose and reducing sugars within the first five days of exogenous ethylene treatment, with sucrose accumulation being the initial response. Ethylene negatively impacted the expression of genes encoding glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase and α-1,4 glucan phosphorylase, which are integral to the early stages of starch biosynthesis, along with two isoamylases[55]. In the 'Favourita' potato variety treated with 117.9 μL·L−1 ethylene, there was a notable reduction in the number of upregulated genes associated with starch and sucrose metabolism, indicating inhibition of starch mobilization in sprouted tubers[20].

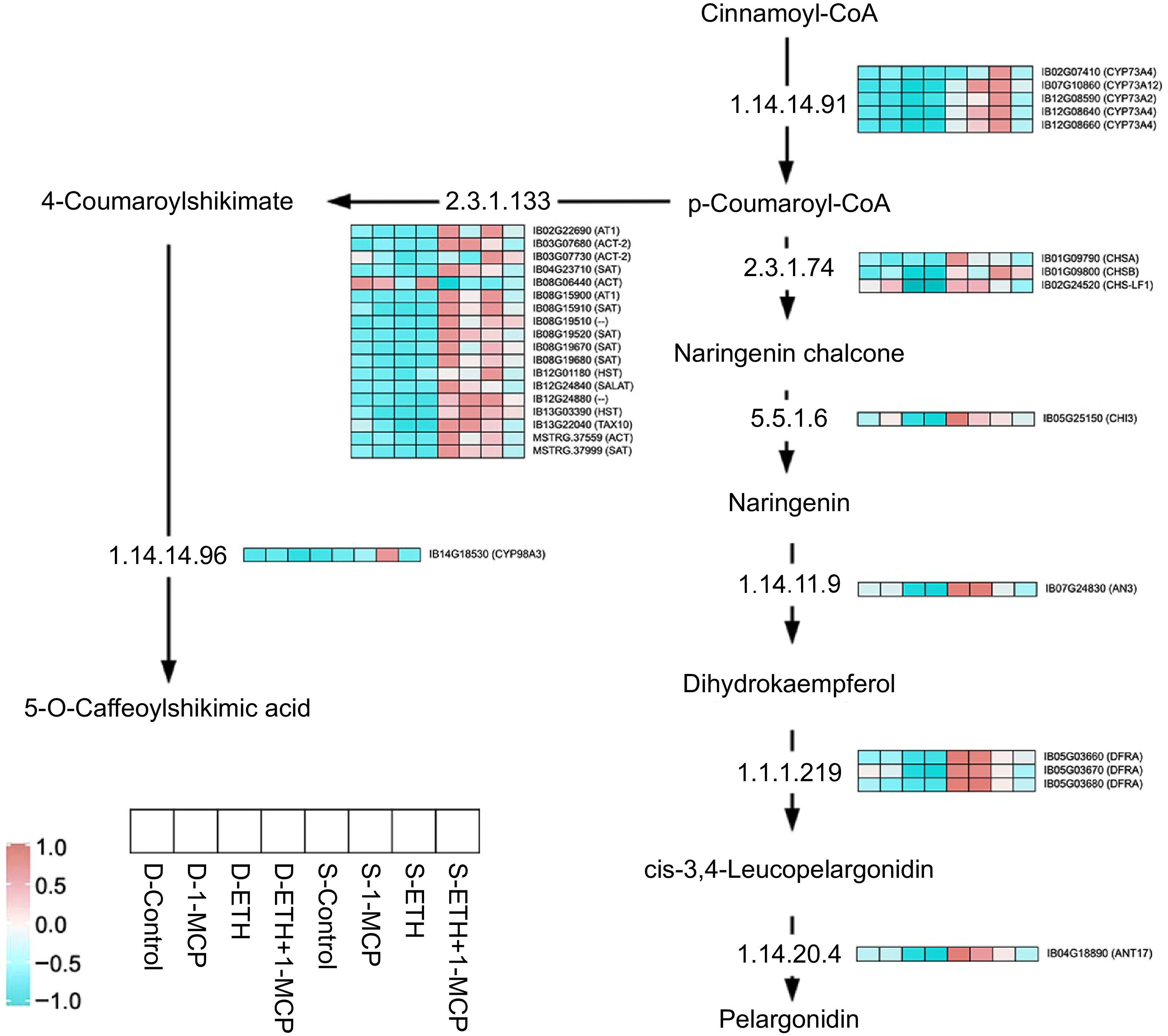

Gene regulatory network associated with flavonoid metabolites

-

Flavonoids, abundant in plants, are celebrated for their antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties, enabling them to neutralize free radicals effectively[56]. These compounds are essential for eliminating reactive oxygen species, thereby significantly contributing to plant development and defense against various biotic and abiotic stresses[57]. In sweet potatoes, pelargonidin, an anthocyanin, stands out as a key secondary metabolite that enhances resistance to oxidative stress[58].

This study found that toots treated with ETH, 1-MCP, and ETH + 1-MCP had significantly higher flavonoid content during dormancy and germination compared to the control group (Fig. 1b-8). The ETH + 1-MCP group maintained the highest flavonoid levels. However, all treatments resulted in decreased flavonoid content in germination, with the upregulation of key genes in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway during this period. Our comprehensive analysis of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in the sweet potato transcriptome reveals the expression patterns of crucial enzymes and associated genes (Fig. 7). We identified 33 DEGs critical to this metabolic cascade. The pathway begins with the catalyzation of cinnamoyl-CoA, progressing through intermediates like p-coumaroyl-CoA and naringenin chalcone, ultimately resulting in the production of pelargonidin. During the transition from dormancy to germination, expression levels of CYP73A, CHS, CHI, AN3, DFRA, and ANT17 were notably low. However, after treatment with ETH and ETH + 1-MCP, CYP73A expression significantly increased, while most other pathway genes remained low during germination. A strong correlation was observed between these gene expressions and flavonoid content. Both ETH and ETH + 1-MCP treatments maintained low flavonoid production levels, potentially aiding sweet potatoes in adapting to environmental changes. In the biosynthetic pathway of 5-O-caffeoylshikimic acid, ACT and SAT genes typically show low expression during dormancy but significantly increase upon germination across all treatment groups. Notably, ETH + 1-MCP treatment induced a modest increase in gene expression, suggesting its regulatory influence on flavonoid metabolism. Additionally, ETH treatment was linked to an increase in CYP98A3 expression during germination, indicating ETH's role in modulating this gene.

A transcriptomic analysis of post-harvest Chinese cabbage treated with chlorine dioxide, benzoic acid, and 1-MCP revealed that 1-MCP upregulated genes Bra007142, Bra008792, Bra009358, and Bra027457. This regulation facilitated the degradation of hesperidin, chalcone, rutin, and total flavonoids while delaying the degradation of baicalin, resulting in lower levels of the former and higher concentrations of baicalin compared to controls[59]. Omics techniques were employed to investigate the TFs regulating pigment metabolism associated with yellowing in Chinese cabbage during storage at 20 °C after 1-MCP fumigation. This analysis identified 28 DEGs, including six linked to flavonoid biosynthesis, which played a crucial role in the yellowing process. 1-MCP treatment led to the continuous downregulation of most flavonoid biosynthesis genes (Bc4CL1, Bc4CL4, BcCHS3, and BcFLS3) while upregulating BcC4H, Bc4CL4, and BcFLS in late storage[60].

-

This study highlights the significant impact of various postharvest treatments on the sprouting and quality of organic sweet potato cultivar Kokei No.14. The results demonstrated that both 1-MCP and ethylene treatments effectively inhibit sprouting and respiratory rates, reducing weight loss and extending shelf life under controlled storage conditions (25 °C, RH 90%, 20.95% O2, 0.038% CO2 with 12 h of sunlight exposure). Notably, the combined application of ethylene and 1-MCP showed a synergistic effect, leading to enhanced quality attributes, such as color vibrancy, which is critical for market acceptance. Ethylene treatment extended the sprouting time by 11 d, 1-MCP by 5 d, and the combined treatment of ethylene and 1-MCP by 23 d. The transcriptomic analysis further elucidated the underlying biological mechanisms governing these effects. The identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to phytohormone signaling, starch, and sucrose metabolism, and flavonoid synthesis underscores the complex regulatory networks involved in sweet potato development and storage physiology. Specifically, the findings from the Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) indicated that these DEGs correlated strongly with key physiological indicators, including sprout number, length, and overall root quality. In conclusion, this research advanced the understanding of the molecular mechanisms that regulate sweet potato sprouting and provided practical strategies for optimizing postharvest management. The insights gained from this study could inform future practices aimed at enhancing the storage longevity and marketability of sweet potatoes, ultimately contributing to reduced waste and improved food security. Further investigations into additional treatments and their combinations may offer additional avenues for extending the shelf life and quality of sweet potato roots in storage.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260443), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (322QN251 & 323RC411), the Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (SKJC-JYRC-2024-20), the Earmarked Fund for CARS-10-Sweetpotato, National Tropical Plants Germplasm Resource Center, Specific Research Fund of the Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (YSPTZX202206) and the Scientific Research Start-up Fund Project of Hainan University (KYQD(ZR)22125).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Kou J, Zhu G, Chen Y; data collection: Zang X, Wang B, Wu G; analysis and interpretation of results: Zang X, Peng M, Wang B; draft manuscript preparation: Zang X, Kou J, Wu G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

accompanies this paper at (https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/tp-0025-0015)

-

Received 16 February 2025; Accepted 29 March 2025; Published online 7 May 2025

-

Ethylene and 1-MCP play important roles in organic Kokei No.14 root sprouting.

Ethylene and 1-MCP suppressed sprouting in Kokei No.14 root separately or in combination.

Starch and flavonoids are essential inducers of sweet potato root sprouting.

The AP2/ERF, MYB, bHLH, and WRKY genes play a vital role in root sprouting.

Ethylene takes a crucial part in plant hormone regulation in root sprouting.

- Supplementary Table S1 Transcription factors differentially expressed (up- and down-) between consecutive time points in Kokei No.14 organic sweet potatoes. D-Control, D-1-MCP, D-ETH and D-ETH+1-MCP represent the dormancy period and S-Control, S-1-MCP, S-ETH and S-ETH+1-MCP represent the sprouting period after treatment, respectively.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Validation of transcriptome data by qRT-PCR.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zang X, Wu G, Peng M, Wang B, Chen Y, et al. 2025. Comparative transcriptomic analyses of ethylene and 1-MCP controlling sprouting in Kokei No.14 organic sweet potatoes during storage. Tropical Plants 4: e019 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0015

Comparative transcriptomic analyses of ethylene and 1-MCP controlling sprouting in Kokei No.14 organic sweet potatoes during storage

- Received: 16 February 2025

- Revised: 26 March 2025

- Accepted: 29 March 2025

- Published online: 07 May 2025

Abstract: The organic sweet potato cultivar Kokei No.14 is recognized for its high quality, nutritional benefits, and favorable growth performance in Hainan province (China). However, postharvest sprouting of Kokei No.14 presents a significant challenge during storage. To clarify sprouting mechanism, we performed several treatments including continuous air (Air), 1-MCP (30 μL·L−1), ethylene (200 μL·L−1), and combined ethylene and 1-MCP. The sprouting rates, quality changes, and transcriptomic analysis after treatment were investigated. The results indicated that ethylene, 1-MCP, and their combined treatment significantly inhibited germination and respiration rates, reduced weight loss, and extended the root shelf life. The combination of ethylene and 1-MCP was more effective in reducing sprouting than the individual application of either compound. Meanwhile, ethylene treatment enhanced the color vibrancy and flavor of the roots. Transcriptome analysis identified 2,069 transcription factors, predominantly AP2/ERF, MYB, bHLH, and WRKY, which were crucial in regulating root sprouting and quality changes during germination. A total of 360 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were assigned to 19 KEGG pathways including starch and sucrose metabolism, plant hormone signal transduction, and the flavonoid pathway by comparative transcriptome. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) indicated that these DEGs were primarily associated with physiological indicators such as sprout number, sprout length, weight loss, respiration rate, color, starch, and sucrose content. DEGs in these pathways played a crucial role in regulating sweet potato sprouting after ethylene and 1-MCP treatment. This research provided a theoretical basis and practical guidance in germination inhibition and quality improvement of organic Kokei No.14 sweet potato roots.