-

The central dogma of molecular biology is a complex of two diverse processes of genetic information transfer: transcription and translation. In eukaryotes, nearly 90% of the whole genome is transcribed into RNA, but only RNA is translated into polypeptides[1]. A significant proportion of RNAs do not correspond to protein-coding protein-non-coding RNA (ncRNA)[2]. ncRNAs comprise a heterogeneous class of transcripts, including regulatory RNAs (miRNA and siRNA), housekeeping RNAs (tRNA and rRNA), and long non-coding RNAs ( lncRNAs)[3]. Initially, lncRNAs were represented as 'junk DNA' or 'dark matter', but later gained attention due to their diverse roles in biological functions, such as in epigenetics, growth, development, and other regulatory processes, which can directly or indirectly hijack proteins or their mRNAs[4]. An lncRNA could be more than 200 nucleotides in length; have two or more exons; and a few open reading frames, which could code for shorter proteins (fewer than 100 amino acids)[1].

Once regarded as functionless, lncRNAs are now recognized as emerging regulators that are pivotal for the smooth functioning of diverse cellular processes or genomic activities in plants. The biosynthesis of lncRNAs is a complex and multistep process involving multiple enzymes. Each step is catalyzed by a specific set of enzymes. Although lncRNA biogenesis is quite complicated, it is still similar to that of mRNAs but is enriched in the nucleus due to insufficient processing by RNA polymerase II (Pol-II)[5]. The lncRNAs transcribed by Pol-II possess a 3′-polyadenylated (poly-A) tail and a 5-methyl-cytosine cap. In comparison, Pol-IV and Pol-V play key roles in the biogenesis of lncRNA that lack poly-A tails, and play a significant role in driving RNA-directed DNA methylation. These lncRNAs are merely aberrantly expressed when compared to those derived from Pol-II and are characterized by high instability[6].

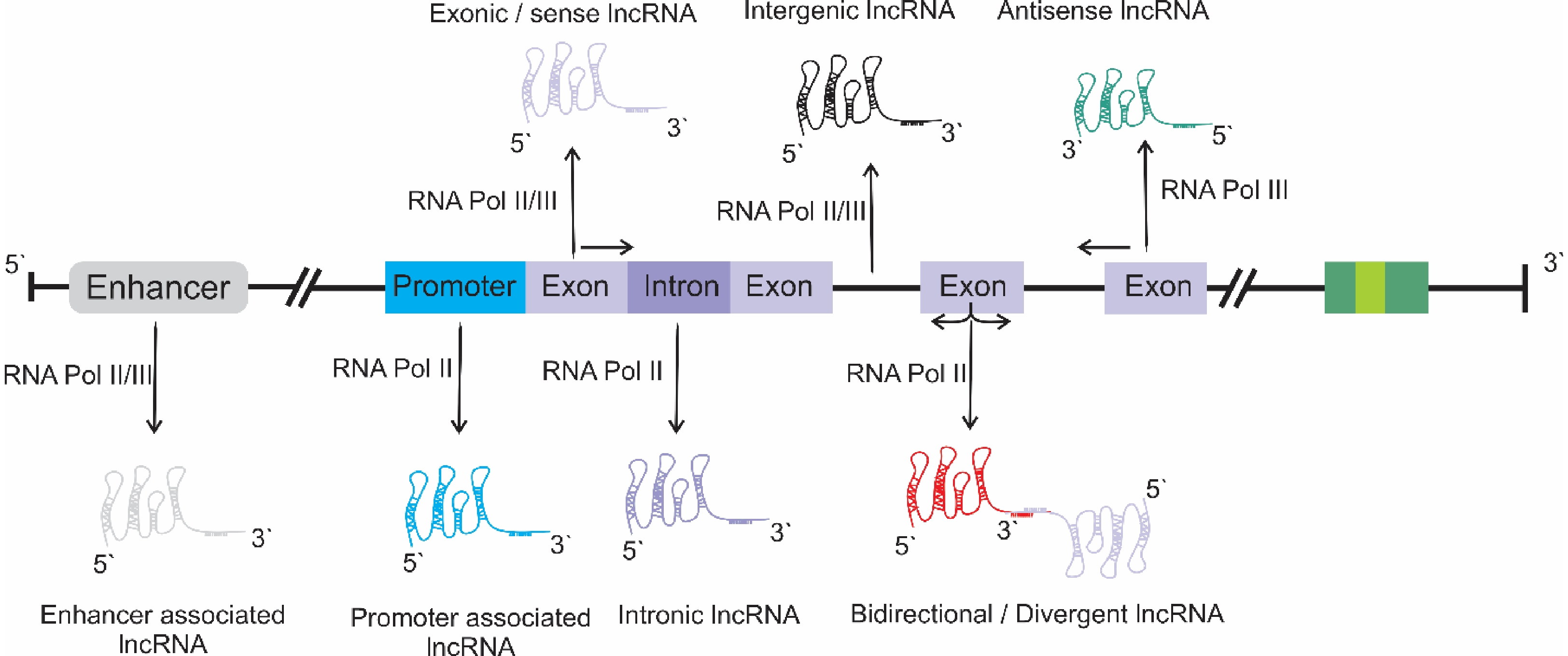

However, based on their genomic context, lncRNAs are classified into the following groups: enhancer enhancer-associated lncRNAs; promoter promoter-associated lncRNAs; intronic lncRNAs; sense or exonic lncRNAs; long intergenic lncRNAs; divergent or bidirectional lncRNAs; antisense lncRNAs (Fig. 1). These lncRNAs are transcribed by Pol-II, Pol-IV, or Pol-V[1]. To date, studies of the biosynthesis of lncRNAs in relation to specific physiological conditions and their mechanisms of action remains in their infancy.

LncRNAs have different features. lncRNAs are abundant and critical group of RNA molecules that modulate gene expression, controlling diverse biological processes related to development and response to environmental constraints. The first lncRNA, H19, was discovered in 1984 in mice[7] and functions as an oncogene in many malignant tumors. With the advancement of next-generation technology and comparative genomics, EARLY NODULIN 40 (ENOD40) was reported as the first plant lncRNA involved in symbiotic nodule organogenesis in Medicago truncatula[8]. Several lncRNAs have been characterized as riboregulators of various important biological processes in plants, including flowering, leaf development, pollen development, male sterility, plant innate immunity, nutrient toxicity and deficiency, and responses to diverse environmental constraints, such as salinity, drought, and temperature extremes (Fig. 2)[1].

Figure 2.

Functional regulation of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in plant growth, development, and stress responses. HID1 plays an important role in seed germination, APOLO, MIKKI, and WOX11a alter root development and root system architecture, leaf morphogenesisis controlled by UGT73c6 (a NAT lncRNA) is regulated cold and spring flowering, flowering time by Zm401, COLDAIR, COLDWRAP, COOLAIR, lncR-TaVRN1, MASS, LINC-AP2, FLORE, and ASL, pollen development is control by MF11, ZM40, and LDMAR. ENOD40 promotes root nodulation. Sex differentiation is determined by SUF and CsM10. Plant ability to enhance nutrient accumulation is in addition to a protein-coding genes is also contributed by lncRNAs like IPS1, T5120, Mt4, OsPI1, TPS11, PILNCR1, and PMAT. SVALKA, MrCIR2, Xh123, and CIL1 regulate tolerance to high temperatures, while DANA2, DRIR, and DAN1 regulate drought tolerance, and lncRN4354 regulates salinity stress in plants. ALEX1 and JAL1/3 regulate phytohorme-mediated responses in plants. However, there are several lncRNAs like ELENA1, lncRNA23468, lncRNA16397, S-sylnc0957, and lncR33732 that regulate pathogenic infections and enhance disease resistance[1].

Recent advancements in studies of lncRNAs in plants have provided compelling evidence supporting the fact that despite lacking protein-coding potentials, lncRNAs play critical roles in regulating gene expression, either directly or indirectly. lncRNAs lack sequence conservation, which does not impair their function. In general, lncRNAs exhibit very low sequence conservation across different plant species. Their rapid evolutionary rate contributes to this genetic variability, and the nature of their functions depends on their structural features rather than their precise sequence identity[9]. The diverse regulatory roles of lncRNAs are due to their high sequence variability, which assists plant breeders in developing new stress-tolerant cultivars.

-

Brassica crops are highly nutritive, have high economic value, and have high economic value. They are cultivated as vegetables, fodder, edible oils, and other usable products[10]. Brassicaceous crops belong to the taxa B. rapa, B. juncea, B. napus, and B. oleracea. These crops are highly susceptible to various environmental constraints; however, the introduction of genetically modified Brassica cultivars has greatly reduced the impact of harsh environmental conditions to overcome the reduction in crop production and yield. With the advancement of next-generation sequencing technologies, a plethora of lncRNAs have been identified in Brassica crops across different developmental stages and diverse environmental constraints. This review aimed to improve the current understanding of lncRNAs in Brassica crops. Altogether, this study summarized the characteristics and highlighted the regulatory roles of lncRNAs in plant biological processes, such as growth, development, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses in Brassica crops.

-

Since the advent of genomic studies that have focused on the transcriptome, the number of genome studies has increased significantly owing to their high precision and cost-effectiveness. The study of lncRNAs is challenging owing to their low expression and sequence conservation. Many lncRNAs have been identified in diverse biological processes such as growth, development, and responses to environmental constraints[11]. Transcriptome analysis and standardization of lncRNA identification pipelines has generated significant data concerning lncRNAs in Brassica crops. The enormous amount of data facilitates global identification and in silico characterization of lncRNAs in Brassica crops to understand their potential function and expression patterns. Genome-wide identification and characterization of lncRNAs in Brassica crops in specific tissues, developmental stages, and responses to abiotic and biotic stress are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Genome-scale identification of lncRNAs in Brassica crops in specific tissues, developmental stages, and environmental conditions.

Brassica plant Number of lncRNAs Developmental stage Stimuli / environmental condition Ref. Abiotic Biotic Brassica rapa 1,031 NAT-lncRNAs Heat [12] 12,051 lncRNAs Pollen development and fertilization [13] 18,253 lncRNA Heat [14] 254 DE-lncRNAs Vernalization [15] 407 lncRNAs Anthers development [16] 278 lncRNAs Heat [17] 4,594 lncRNAs Heat [18] 6,392 lncRNAs Pollen development [19] 385 DE-lncRNAs Male sterility and fertility [20] Brassica napus 3,181 lncRNA Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [21] 11,073 lncRNAs Cold [22] 8,094 lncRNAs Seed oil accumulation 5,546/6,997 in Q2 and 7,824/10,251 Qinyou8 down/upregulated Drought and re-watering [23] 2,546 lncRNAs Cadmium [24] Brassica juncea 7,613 lncRNAs with 1,614 DE-lncRNAs Drought and heat stress [25] 3,602 DE-lncRNAs Salinity [26] 1,539 lncRNAs Seed development [27] Brassica oleraceae 148 DE-lncRNAs Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis [28] -

The seed of Brassica crops have unique economic value and are a vital source of edible oil, nutrients, and biofuel with key crop improvement traits. However, seed-related traits such as seed size, vigor, shape, and oil content are of paramount importance, and are target targets for crop improvement[29]. Recently, lncRNAs were reported to be involved in regulating seed oil content and fatty acid composition in Brassica crops. For instance, the seeds of two contrasting genotypes of B. Juncea, Early Heera 2 (EH2) and Pusajaikisan (PJK), had 809 differentially expressed lncRNAs, of which 25 lncRNAs were significantly correlated with seed size, color, and accumulated oil content. The expression of 28 lncRNAs correlated with fatty acid biosynthesis genes, indicating that these lncRNAs play a critical role in oil synthesis[27]. This study is consistent with that of Shen et al.[30], which indicated that 13 lncRNAs in B. napus were significantly correlated with eight lipid-related genes. Comparative analysis of lncRNAs in two B. napus accessions, WH5557 (low oil content) and ZS11 (high oil content), indicated the role of two lncRNAs (MSTRG.22563 and MSTRG.86004) in the regulation of oil content accumulation and fatty acid composition. MSTRG.22563 might affect seed oil content by affecting respiration and the TCA cycle, while MSTRG.86004 plays a role in prolonging seed developmental time to increase seed oil accumulation[31]. Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) indicated dynamic alterations in oil content and fatty acid composition during seed development and in low-low-high oleic acid rapeseed genotypes. Genes related to lipid biosynthesis, such as 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 16 (KCS16) and acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1), were predicted in the co-expression network, suggesting that their effect on lipid metabolism might be embodied by increasing the expression of these lncRNAs[32]. Oil biosynthesis is one of the major experimental research areas focused on the key biological process in Brassica crops. However, the role of lncRNAs in fatty acid and lipid biosynthesis vary. Understanding the role of lncRNAs in fatty acid and lipid biosynthesis is still limited or in its early stages.

-

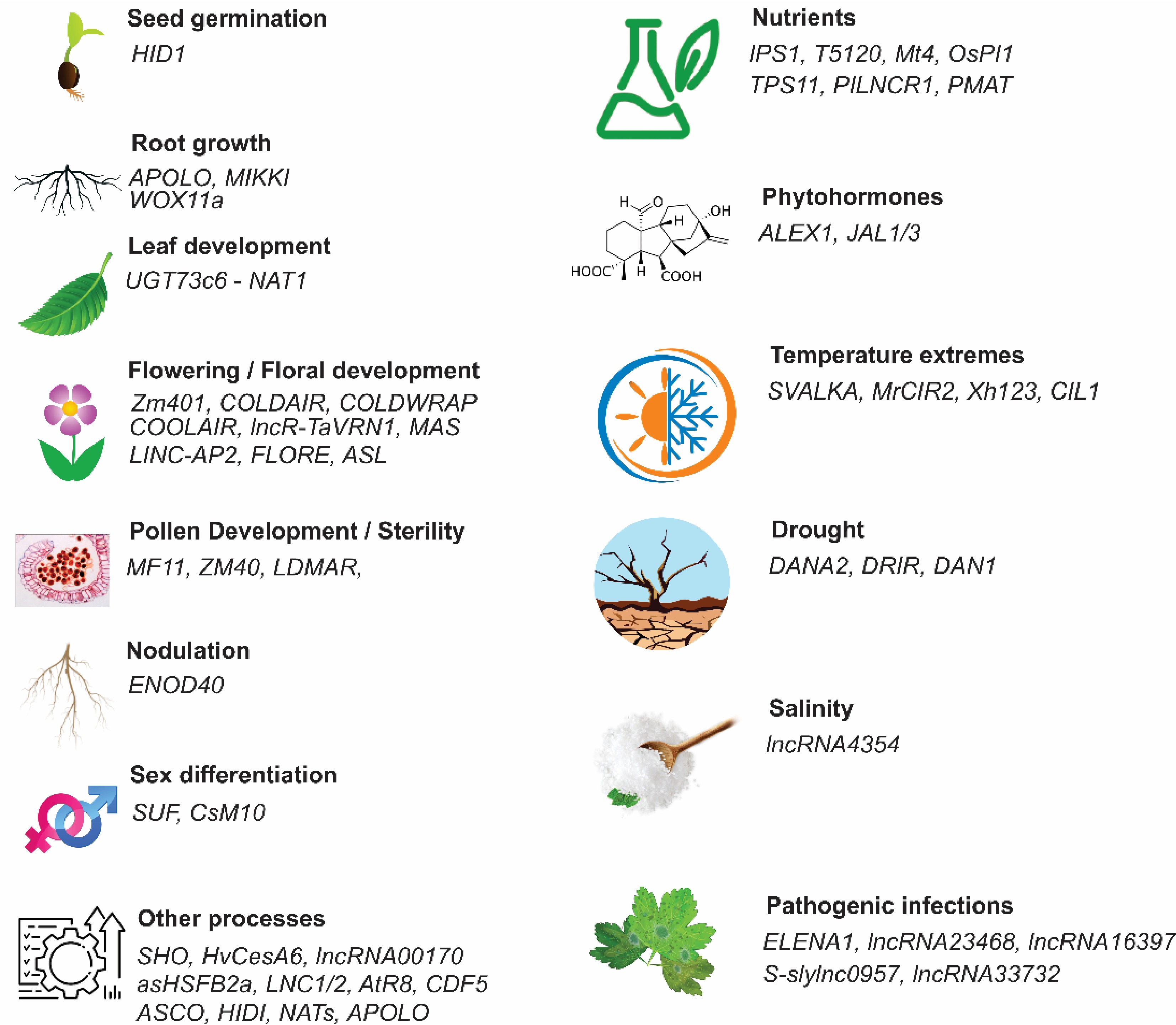

The underestimation of the roles of lncRNAs is probably due to the relatively low expression of lncRNAs compared to that of protein-coding genes or small RNAs such as miRNAs. An in-depth study of plant lncRNAs based on their molecular mechanisms and the iris based on their molecular mechanisms and related biological functions. In plants, many lncRNAs have been identified by in-silico approaches considered to participate in crop fertility, such as flower bud development and flowering. Pollen development is a key process in controlling productive development. In the cytoplasmic male sterile system (CMS) in rapeseed, Xing et al.[33] reported five lncRNAs cis-target genes in Pol (P5A) and Nsa (1258A) genotypes during pollen abortion. Among these lncRNAs, β-glucosidase (LOC106445716) was predicted as the target gene of lncRNA, MERGE.18561.2 and could regulate pollen development and be related to pollen abortion (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of action of lncRNAs in different developmental and stress responses. (a) a lncRNA (MERGE.18561.2) impacts pollen viability by targeting beta-glucosidase genes. (b) MF11 suppresses pollen germination efficiency, delays pollen tube germination, delays tapetum degradation, and aborts the development of pollen grains. (c) lncRNAs acting as endogenous targets of bra-miR160, bra-eTM160-1, and bra-eTM160-2, suppress the activity of miR160 activating ARF genes, which subsequently influence pollen development. (d) lncRNA as eTM of bra-miR156 in Chinese cabbage, which ultimately delays flowering by activating SPL genes. (e) An antisense lncRNA activates the MAPK15 gene to enhance resistance against downy mildew.

Male Fertility (MF) is a novel pollen-specific lncRNA, involved in regulating tapetum degradation and pollen wall formation, which is a critical step in the formation of tapetum degradation and pollen wall formation, a necessary step in the formation of viable pollen[34]. In Brassica crops, MF11 has been characterized in different species, such as B. campestris. Downregulation of BcMF11 suppresses pollen germination efficiency, delays pollen tube germination, delays tapetum degradation, and aborts the development of pollen grains (Fig. 3b)[35]. Likewise, BcMF8 encodes a putative arabinogalactan protein-encoding (AGP) gene that contributes to aperture formation, pollen tube growth, and pollen wall development in B. campestris[36]. The B. rapa lncRNAs, BcMF11, and BcMF11 are essential for tapetum and pollen development[37]. However, Wei et al.[20] reveal the potential role of lncRNA-mR in the NA modules in the genetic male fertility and sterility of B. rapa. Among these lncRNA-miRNA modules, MSTRG.13.532-BraA05g030320.3C (pectinesterase), MSTRG.9997-BraA04g004630.3 C (β-1,3-glucanase) and MSTRG.5212-BraA02g040020.3 C (pectinesterase) are associated with asynchronous tetrad separation, tapetum degradation, and callose degradation indicating their potential regulatory role in pollen development. The role of lncRNAs in Brassica crops was further strengthened by systematic analysis of lncRNAs during pollen development in B. rapa. For instance, systematic analysis of lncRNAs revealed two lncRNAs as endogenous target mimics of miR160 functioning in pollen development, and Huang et al.[13] predicted 15 lncRNAs as endogenous target mimics of miRNAs, particularly target mimics of miR160. For example, two lncRNAs, bra-eTM160-1 and bra-eTM160-2, were predicted to be potential eTMs for bra-miR160-5p and to affect the expression of its target gene, auxin response factor (ARF). bra-eTM160-2 was predominantly expressed in inflorescences, and transgenic plants overexpressing bra-eTM160-2 showed abnormal pollen grains without nuclei and were not viable with complete abortion (Fig. 3c).

-

Flowering in plants involves non-coding cues that regulate an intricate molecular mechanism in the transition from the vegetative to the reproductive phase and ensure seed productivity. To date, studies have revealed the roles of many coding and non-coding genes, including lncRNAs, which play a central role, and their interactions ultimately influence flowering time[38]. Vernalization, a crucial phenomenon for successful flowering and sustainable yield in B. rapa, is intricately regulated by lncRNAs. In this realm, FLOWERING LOCUS C, a principal inhibitor of flowering B. rapa contains multiple homologs of FLC genes, three of which are syntenic orthologs of AtFLC. For example, Dai et al.[39] reported an inversion of the expression of the flowering repressor genes BrFLC1 and BrFLC2 in B. rapa during vernalization and displayed acceleration in flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis. However, in B. oleracea, BoFLC1 contributes to non-flowering traits through tandem duplication[40]. A premature stop codon in the BrFLC2 transcript of B. rapa leads to early flowering[41]. BrFLC5 is predicted as a flowering time QTL and it is possibile that BrFLC5 is involved in flowering time variation[42]. Furthermore, in the B. rapa genome, BrFLC5 is classified as a pseudogene because it lacks two exons. A splicing site mutation in B. rapa BrFLC5 is related to variation in flowering time[43]. Akter et al.[44] confirmed that BrFLC5 acts as a floral repressor when it is overexpressed in Arabidopsis. In B. rapa, comparative transcriptome analysis provided a new perspective on the mechanism of lncRNAs during vernalization. Liu et al.[15] found that BraZF-HD21 (Bra026812) expression is correlated with TCONS_00035129 in B. rapa. More recently, a precursor of miR156 from the lncRNA bra-miR156HG in B. campestris, heterologous expression in Arabidopsis, was directly linked to the delayed flowering phenotype (Fig. 3d)[45].

-

Temperature extremes are detrimental to crop production and are associated with the drastic changes in annual precipitation and global warming. Heat stress leads to alteration in biochemical and physiological factors including accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced chlorophyll contents causing damage including the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced chlorophyll content, causing cellular damage[46]. In Brassica crops, heat stress during the early seedling stage drastically affects growth and productivity by disrupting the metabolic enzymatic activity of the seed[47]. To date, studies on Brassica crop responses to heat stress have been limited to biochemical and physiological alterations; however, recent transcriptome-wide analyses have identified and characterized several lncRNAs in Brassica crops at the genome scale. These lncRNAs modulate protein-coding genes, and protein-coding gene expression in response to heat stress. For example, transcriptome analysis of B. juncea revealed 1,614 lncRNAs in response to heat stress[25]. In B. napus, 11,073 highly confident lncRNAs were identified under cold stress conditions[22]. However, another study in B. rapa predicted 2,088 lncRNAs in the whole transcriptome of four-week cold stressed plants. Vernalization-related lncRNAs, including natural antisense transcripts (NATs), have been reported in BrFLC and BrMAF[48]. In contrast, in B. rapa plants 4,594 lncRNAs were predicted to be involved in heat stress responses. Among these, a heat-responsive lncRNA, TCONS_00048391, functions as an endogenous target mimic for bra-miR164, a target of NAC1 in Chinese cabbage[18].

Drought is another pivotal factor limiting plant growth and productivity. Brassica crops are vulnerable to drought, and their production is substantially affected. In the current scenario of global warming and shrinking precipitation, research studies have focused on characterizing or understanding the mechanisms of drought tolerance and enhanced resistance levels[23]. In B. juncea, 1,614 differentially expressed lncRNAs responded to drought, and a few were simultaneously expressed with transcription factors showing an abiotic stress response[25]. Tan et al.[23] indicated that lncRNAs are key players in the response to drought stress in drought-sensitive (Qinyou8) and drought-tolerant (Q2) genotypes. The differential expression of these lncRNAs regulates the expression of genes involved in hormone signal transduction and stress/defense responses. WGCNA in B. juncea indicated that the lncRNA MSTRG.150397 acts as a regulatory lncRNA, and MSTRG.107159 acts as an inhibitory lncRNA. The former was inferred to potentially modulate key photosynthetic genes (PetC, Psb27, PsbW, PetH, and PetH), whereas the latter functioned as regulators of drought-responsive PIP genes[49]. However, an alternative way to explore the complex mechanisms of drought tolerance in rapeseed is through transcriptome-wide analysis of drought-responsive lncRNAs, which have been suggested to act as a regulatory hub by controlling phytohormone signaling pathway genes such as ABRE-binding factors (ABFs), phosphatase 2C (PP2C), and SMALL AUXIN UPREGULATED RNAs (SAURs)[50].

Salinity is another global environmental stressor that causes a reduction in yield quality and productivity by the sudden induction of physiological dysfunction in plants. Salinity is a key growth-limiting factor for Brassica crops, leading to stunted plant growth and lower yields[51]. For instance, canola is an important global oil crop; although it is considered to be salt-tolerant, its yield and productivity are still affected by salinity[52]. Salinity has a detrimental effect on canola, including decreased potassium and elevated sodium levels, and it is imperative to mitigate the negative impacts of salt[51]. Many lncRNAs have been reported to play critical regulatory roles in salt-stress tolerance. However, there is a significant gap in lncRNA identification and characterization under elevated salt stress conditions in Brassica crops. For instance, a few preliminary studies in Brassica crops, such as B. juncea, reported 3,602 differentially expressed lncRNAs, of which 61 were predicted to display salt stress-specific responses[26].

Studies on the involvement of lncRNAs in various biological responses to environmental stress have increased daily. Contamination of soil by heavy metals is a global challenge. The mining and characterization of genes that control heavy metal uptake and translocation are the first steps in heavy metal tolerance[53]. The recent discovery of lncRNAs via transcriptome-scale profiling has provided new information regarding novel regulatory pathways for plant responses to this stress. Recently, genome-scale identification of genes involved in metal uptake, detoxification, and translocation has been performed in a number of plant species. Brassica crops are ideal plants for the phytoremediation of heavy metals, with moderate to high accumulation capacities. For instance, cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal contaminant in the environment. In B. napus. Strand-specific RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) profiling of lncRNAs in response to Cd stress revealed that three lncRNAs function as target mimics of heavy metal transport proteins, including Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase copper chaperone precursor, metal transporter NRAMP3, and disease resistance response protein[24].

-

Plants are susceptible to diverse pathogens that cause diseases and affect final productivity and plant survival. Plant diseases are major contributors to global food scarcity. Plants have acquired many molecular non-coding genetics and physiological strategies to fine-tune their defense mechanisms. One such strategy at the molecular and genetic levels includes the regulation of gene expression by non-coding RNAs, particularly lncRNAs. The study of the robust plant immune system mediated by lncRNAs is an emerging field in plants[54]. It is estimated that approximately 20%–40% of global agricultural productivity is lost owing to pathogenic diseases. Of these, 50%–60% of crop yield losses occur in Brassica. Brassica crops are cultivated for oil, animal fodder, high nutritional value, low fat content, and antioxidant properties[55]. The primary pathogens responsible for biotic stress in Brassica crops include Fusarium oxysporum[56], Sclerotinia sclerotiorum[21], Plasmodiophora brassicae, and Hyaloperonospora brassica[57,58]. For example, a study in B. napus using a strand-specific RNA-Seq approach in clubroot-resistant and clubroot-susceptible lines, 530 differentially expressed lncRNAs were identified, of which 24 differentially expressed lncRNAs associated with chromosome A8 conferred resistance to clubroot disease[59]. The role of lncRNAs in P. brassicae in Chinese cabbage was also explored, of which 114 differentially expressed lncRNAs had 16 differentially expressed lncRNAs interacting with 15 defense-related genes[58]. Furthermore, lncRNAs have been reported in S. sclerotiorum[21]. Additionally, Zhang et al.[57] identified a candidate lncRNA, MSTRG.19915, related to downy mildew disease resistance, which is a natural antisense transcript of the MAPK gene, BrMAPK15. MSTRG.19915-silenced seedlings showed enhanced resistance to downy mildew, probably because of the upregulated expression of BrMAPK15 (Fig. 3e).

-

Although Brassica species are traditionally temperate crops, their expanding cultivation in tropical and subtropical regions—particularly through winter cropping systems and highland agriculture—highlights the critical need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying their adaptation to warmer and more variable environments. The rising global demand for oilseeds and vegetables, coupled with climate-induced shifts in agricultural zones, has led to increased efforts to cultivate crops like B. juncea, B. rapa, and B. oleracea in non-temperate environments[60]. However, these environments pose unique challenges, including high temperatures, erratic rainfall, humidity, and altered photoperiods, which can significantly affect growth, flowering time, and yield[46]. Recent transcriptomic and epigenetic studies have begun to uncover regulatory pathways and gene networks—such as those involving heat shock proteins (HSPs), hormone signaling, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification—that are activated under stress conditions in subtropical environments[25]. Importantly, lncRNAs have emerged as novel regulatory elements in these adaptive responses, modulating gene expression post-transcriptionally and interacting with microRNAs (miRNAs) to fine-tune stress tolerance pathways[18, 61].

The adaptation of Brassica crops—such as broccoli, cauliflower, mustard, and canola—to subtropical and tropical climates has garnered significant research interest due to the challenges posed by high temperatures, humidity, and changing photoperiods provided by the new regions. This summary synthesizes findings from recent studies, highlighting genetic, physiological, and agronomic strategies employed to enhance the resilience and productivity of Brassica species in warmer climates.

Traditionally, temperate B. oleracea varieties, such as broccoli and cauliflower, require vernalization—a period of low temperatures—to initiate flowering. However, in subtropical environments like Taiwan, breeding programs have identified genotypes that bypass this requirement. Notably, the gene BoFLC3, rather than the typical BoFLC2, regulates curd induction in these varieties, enabling flowering without cold exposure. Research involving 112 breeding lines of broccoli selected under high-temperature and high-humidity conditions in Taiwan led to the identification of QTLs associated with days to curd induction and curd quality. These findings provide valuable markers for breeding programs aiming to develop heat-tolerant Brassica cultivars[62].

In southeastern Brazil, studies on B. juncea and B. rapa evaluated their growth, yield, and oil content under tropical conditions. B. rapa accessions matured earlier and had higher oil content, while B. juncea exhibited greater pod numbers and overall yield. These results suggest that both species hold promise as alternative oilseed crops for biodiesel production in tropical climates[63].

By targeting specific lncRNAs and their associated regulatory networks, it may be possible to enhance the heat tolerance of these crops, ensuring better yield and resilience in warmer climates. The identification of heat-responsive lncRNAs provides valuable insights for breeding programs aimed at developing Brassica crops suited for subtropical and tropical regions. Understanding these complex regulatory mechanisms not only provides insights into environmental resilience but also facilitates the development of climate-resilient Brassica cultivars through molecular breeding and genome editing.

-

The study of lncRNAs is a challenging task because they are differ from the genomic context of protein-coding genes, are highly non-conserved, and display sequence similarities with structural genes. LncRNAs have been reported to play roles in diverse biological processes, including growth, development, and abiotic and biotic stress responses in plants. Although in Brassica crops, lncRNAs have also been reported to play diverse roles in flowering, vernalization, pollen development, fertility, and stress responses to salinity, drought, and heat, understanding of the specific regulatory mechanism is still in its infancy.

Current understanding of Brassica crop-crop lncRNAs represents only the tip of an iceberg. The key problems are incomplete genome sequencing, lack of a comprehensive collection of lncRNAs associated with different developmental stages, and abiotic and biotic stresses. Therefore, there is a need to establish a link between the lncRNAs and mRNAs. Functional exploration of lncRNAs in seed development, pollen development, flowering time, and heat stress tolerance can be achieved by genetic and molecular modulation using CRISPR-Cas genome-editing approaches, RNAi, and overexpression.

As global temperatures rise, the adaptation of Brassica crops to warmer climates becomes increasingly critical. Breeding programs focusing on heat tolerance, drought resistance, and pest resilience are essential. LncRNAs play a significant role in the adaptation of Brassica crops to heat stress, a common challenge in subtropical and tropical agriculture. Moreover, integrating traditional breeding with molecular techniques, such as lncRNAs mapping and genetic modification, can accelerate the development of climate-resilient Brassica varieties. Understanding and manipulating these lncRNAs offer promising avenues for improving crop resilience and productivity in the face of climate change.

Although this review demonstrates that lncRNAs play a role in a variety of biological processes in Brassica crops, such as pollen development, flowering, and abiotic stress responses, research on lncRNAs in Brassica crops is still in its early stages. In particular, little research has been conducted on the precise regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs in Brassica species. Research methods for lncRNAs in animals and model plants such as Arabidopsis and rice should be extended to lncRNAs in Brassica crops. Exploration of the function and mechanism of lncRNAs in Brassica crops has just begun, and rapid progress and development of technology will bring new opportunities and breakthroughs for lncRNA research in Brassica crops.

This work was supported by grants from the China NSFC Research Fund for International Young Scientists (Grant No. 32250410291), the Key Research Program of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2022XDNY185), and a Special PN on coding the Academician Team Innovation Center of Hainan Province (Grant No. YSPTZX202206).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Basharat S, Waseem M; supervision, funding acquisition: Waseem M, Liu P; writing − original draft preparation: Basharat S, Waseem M; writing − review & editing: Basharat S, Waseem M, Liu P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Received 26 March 2025; Accepted 9 June 2025; Published online 28 August 2025

-

# Authors contributed equally: Sana Basharat, Muhammad Waseem

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Basharat S, Waseem M, Liu P. 2025. Long non-coding RNAs in Brassica crops: molecular hijackers of developmental processes and stress responses with implications for tropical adaptation. Tropical Plants 4: e029 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0021

Long non-coding RNAs in Brassica crops: molecular hijackers of developmental processes and stress responses with implications for tropical adaptation

- Received: 26 March 2025

- Revised: 06 June 2025

- Accepted: 09 June 2025

- Published online: 28 August 2025

Abstract: The genus Brassica comprises diverse agriculturally important crops and is grown for vegetables, oil crops, forage, and industrial purposes. With the advancement of next-generation sequencing technologies in plants, hundreds of thousands of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified and characterized in Brassica crops. LncRNAs intricately regulate diverse aspects of Brassica crop growth and development, including flowering time, flower fertility, pollen development, and abiotic stress tolerance, and involve unique mechanisms that regulate gene expression, miRNAs, and interaction in controlling hormone pathways. This review aims to present a comprehensive overview of lncRNAs, with a particular focus on their regulatory roles in Brassica crops which are increasingly grown in tropical and subtropical agricultural systems under abiotic stress conditions, such as heat, drought, and salinity.

-

Key words:

- Bra

ssica / - lncRNAs /

- Tolerance /

- Pollen development /

- Flowering