-

Stable angina is a clinical syndrome caused by insufficient coronary artery blood supply, leading to myocardial ischemia and hypoxia. Its pathophysiological characteristics are closely associated with systemic microcirculatory dysfunction. Currently, millions of patients worldwide are affected by stable angina, with approximately 500,000 new cases reported annually[1]. Patients with stable angina face various adverse outcomes, including unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death caused by arrhythmias[2]. The heterogeneity of these clinical trajectories suggests that relying solely on traditional risk factors (e.g., blood pressure and lipid levels) for precise risk stratification is inadequate, necessitating the exploration of novel biomarkers reflecting systemic microvascular dysfunction.

Recent studies have revealed significant correlations between systemic metabolic and hemodynamic indicators (e.g., D-dimer, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and the coronary index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR). However, the clinical utility of these invasive metrics remains limited. Specifically, techniques such as coronary flow reserve (CFR) and IMR measurements require invasive coronary catheterization, which carries procedural risks, high costs, and limited repeatability[3]. These constraints preclude their use for routine monitoring in stable angina patients, particularly in primary care settings where noninvasive tools are urgently needed. Consequently, the development of noninvasive, reproducible tools for assessing microcirculation has emerged as a critical focus in cardiovascular research.

In this context, the retinal vascular system holds unique value. As the only directly observable microvascular network in humans, its examination is noninvasive and repeatable. The structural parameters of retinal vessels, particularly the standardized central retinal arteriolar equivalent (CRAE) and central retinal venular equivalent (CRVE), have been validated as sensitive indicators of systemic vascular endothelial function and hemodynamic stress[4]. Large-scale cohort studies (e.g., the Rotterdam Study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]) demonstrate that narrower CRAE correlates with elevated blood pressure and plasma triglycerides, whereas increased CRVE is associated with systemic inflammatory markers[5−13].

Nevertheless, current research has predominantly focused on general populations or patients with advanced cardiovascular diseases, leaving a critical evidence gap regarding stable angina, a pivotal transitional group. Compared with other populations, the chronic myocardial ischemic state in stable angina triggers alterations in neurohumoral regulatory mechanisms, which may induce specific changes in systemic microvascular systems (including the retinal microvasculature), reflecting disease progression, therapeutic responses, and prognosis[14,15]. Thus, it remains uncertain whether existing retinal parameter reference values—established in healthy populations—apply to stable angina patients, or whether retinal vascular alterations can mirror this group's unique compensatory microcirculatory adaptations. These knowledge gaps underscore the need for large-scale investigations to elucidate the relationships between microvascular parameters and systemic indicators in this population, potentially paving new avenues for clinical diagnosis, disease assessment, and therapeutic strategies in cardiovascular medicine.

As an innovation, this study integrates an artificial intelligence (AI)-based retinal analysis system with multidimensional systemic indicators to address these challenges. By quantifying associations between CRAE/CRVE and metabolic/hemodynamic indices in stable angina patients, we aim to uncover disease-specific retinal microvascular response patterns. This approach elucidates the retinal microvascular signatures of systemic pathologies, supporting further exploration of retinal imaging for microcirculatory monitoring. For instance, establishing quantitative relationships between retinal microvascular parameters and the severity of angina could offer clinicians a simple, noninvasive method for disease evaluation. Furthermore, identifying the mechanisms through which systemic indicators modulate retinal microvasculature may reveal novel therapeutic targets for intervention.

-

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed data from patients who visited the Department of Cardiology at Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China between June 2022 and October 2023. The data were collected from electronic medical records as part of routine clinical care. The study protocol for the retrospective analysis of these deidentified data was approved by the hospital ethics committee on 25 July 2024 (approval number: Ethics-KY-IIT-2024-98). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study was approved by the abovementioned ethics committee, which determined that verbal consent was appropriate, given the large sample size and the fact that the examinations performed were all necessary for hospitalization. No additional examinations of the patients were performed.

Inclusion criteria comprised patients diagnosed with stable angina caused by coronary artery disease. The diagnosis was established based on the 2012 ACCF/AHA guidelines, requiring: (1) the characteristic clinical symptoms of chest discomfort precipitated by physical exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin and (2) objective evidence of myocardial ischemia (e.g., via stress electrocardiography, stress echocardiography, or myocardial perfusion imaging) or the presence of significant coronary artery stenosis (≥ 50% luminal diameter narrowing in at least one major epicardial vessel) confirmed by coronary angiography or coronary computed tomography angiography[3].

Exclusion criteria included: (1) a diagnosis of other coronary artery disease subtypes (e.g., unstable angina, myocardial infarction), (2) major ocular pathologies (e.g., ocular trauma, glaucoma, retinal vascular occlusion, retinitis pigmentosa) or refractive media opacities (e.g., severe corneal disease, cataracts, vitreous opacities) affecting retinal imaging quality, and (3) concurrent cardiac conditions potentially confounding coronary artery disease diagnosis or treatment (e.g., myocarditis, endocarditis). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Questionnaire survey

-

A structured questionnaire was administered to the participants to collect essential data. The information gathered was primarily used for the following two purposes in this study.

● Verification of eligibility: The questionnaire collected a detailed history of other cardiovascular diseases (e.g., unstable angina, myocardial infarction), diabetes mellitus, and major ocular pathologies (e.g., glaucoma, retinal vascular occlusion, major eye surgeries). This information was crucial for confirming that the participants met the study's predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

● Collection of covariates: Data on lifestyle factors, specifically smoking and alcohol consumption, were obtained. Smoking status was subsequently used as a categorical variable in the statistical analyses.

Data collection

-

In total, 26 systemic indicators were selected for analysis on the basis of their established clinical relevance in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease—encompassing hemodynamic, inflammatory, metabolic, and coagulation pathways—and their routine measurement in the clinical management of patients with stable angina[3,16,17]. Systemic indicators were extracted from electronic medical records, including demographics (age, sex, height, weight), with body mass index (BMI) calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Blood pressure measurements were obtained using an automated oscillometric device (HEM-7136; OMRON Healthcare, Singapore) under standardized conditions: The participants rested supine for ≥ 5 min, with the right arm supported at heart level. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and pulse rate were recorded.

Fasting venous blood samples were collected by trained personnel for laboratory analyses of the following:

● Inflammatory markers: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP);

● Cardiac enzymes: Creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (HBDH), cardiac troponin T (cTnT), and myoglobin (Myo);

● Metabolic and coagulation markers: Homocysteine (HCY), D-dimer (D-D), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), triglycerides (TG), creatinine, albumin (ALB), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and fasting blood glucose (FBG).

Hypertension was defined per the 2020 International Society of Hypertension guidelines: A prior diagnosis with antihypertensive medication use, SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg[15]. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a physician-diagnosed disease or use of hypoglycemic medication.

Retinal image quality control and vascular caliber measurement

-

Singapore I Vessel Assessment-Deep Learning System (SIVA-DLS), was developed to provide fully automated and direct measurement of retinal vessel calibers without requiring human intervention for vessel segmentation or manual correction during the quantification process[18]. It employs a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture trained on > 70,000 retinal images from 15 multinational datasets. During the model's training, gradability was manually verified by certified technicians using Singapore I Vessel Assessment (SIVA) v4.0 software. In applied analyses, another automated CNN prefilter excluded ungradable images. Only gradable images (93.0% of the total dataset) were processed for measuring vessel calibre. Technical validation demonstrated excellent agreement with manual SIVA measurements (intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]: 0.82–0.95).

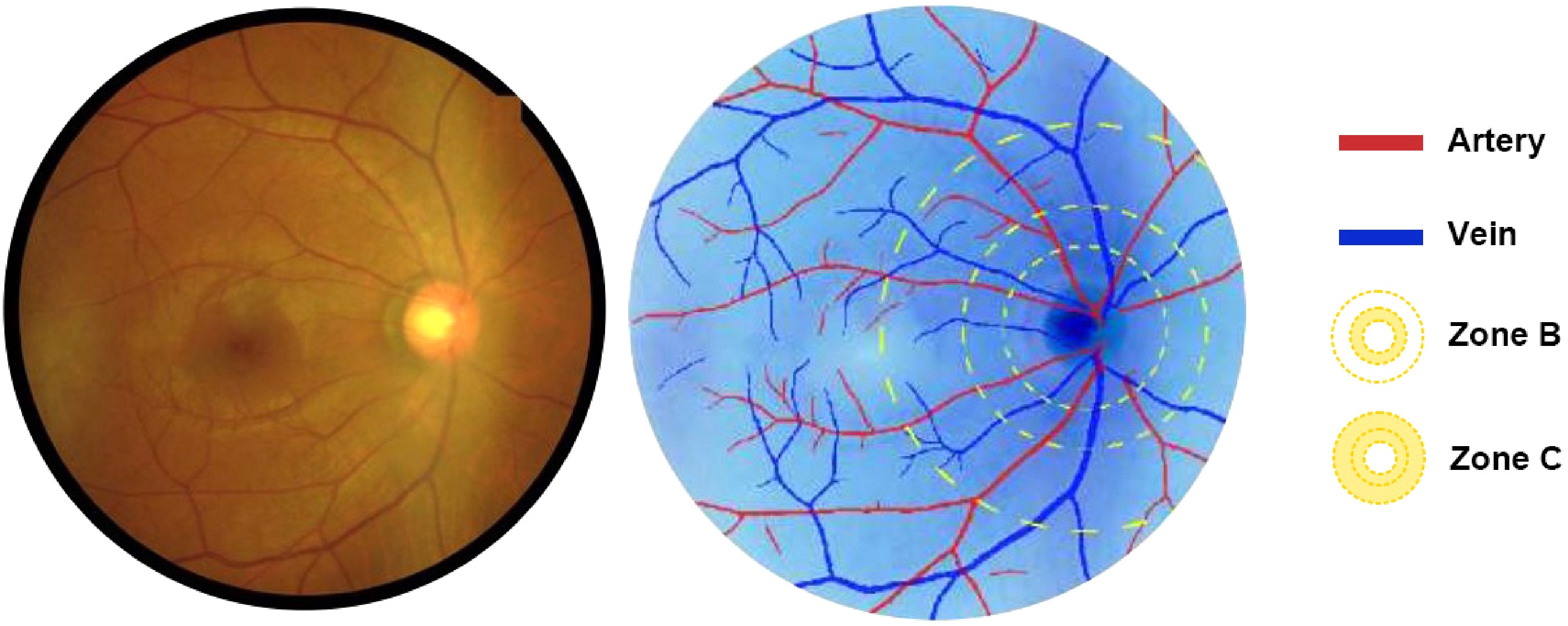

In our study, first, standardized 45° digital retinal photographs (Canon CR-2, Tokyo, Japan) centered on the optic disc were captured by certified ophthalmic technicians. Before processing, following the SIVA-DLS protocol, low-quality images were excluded[18]. Images were deemed ungradable if the six largest retinal vessels were not fully visible within peripapillary Zone B (0.5–1.0 disc diameters from the disc margin) and Zone C (0.5–2.0 disc diameters from the disc margin) because of the following:

● Technical inadequacies (e.g., poor focus, illumination, or optic disc centering);

● Pathological interference (e.g., hemorrhages, laser scars, or media opacities).

After that, the images were processed by Airdoc-AIFUNDUS (v1.0) based on SIVA-DLS to identify and compute CRAE and CRVE by weighting features within Zone B and Zone C. Refer to Fig. 1 for graphical illustration.

Figure 1.

The SIVA-DLS automatically identifies arterioles (marked in red) and venules (marked in blue) within two concentric zones: Zone B (0.5–1.0 papillary diameter [PD] from the optic disc margin) and Zone C (0.5–2.0 PD from the optic disc margin), from which CRAE and CRVE are calculated.

Statistical analysis

-

Descriptive statistics summarized variables as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or counts (percentages).

Univariate analysis identified potential predictors of retinal vascular parameters (p < 0.05 threshold). Multicollinearity was assessed via variance inflation factors (VIFs), with values of > 5 excluded.

For multivariate regression analyses, variables were selected according to a combination of statistical significance from the univariate analysis, established clinical importance, and their potential role as confounders as supported by the existing literature. Even if certain variables (e.g., BMI, diabetes, D-dimer) did not achieve statistical significance in the univariate analysis (p > 0.05), they were retained in the multivariate models because of their widely recognized clinical relevance and their importance in controlling for potential confounding effects on the associations between retinal vascular parameters and the study outcomes[16]. This approach ensured that our findings reflect independent associations adjusted for key demographic and clinical factors, aligning with common practices in cardiovascular epidemiological research.

This dual approach ensures biological fidelity while controlling for overfitting, aligning with established epidemiological modeling guidelines. This purposeful selection method was chosen over automated stepwise regression procedures, as the latter can be prone to model instability and may select variables according to statistical chance rather than clinical importance, which was a key consideration for our etiological focus. The final model selection integrated statistical validity and clinical interpretability[17].

Standardized β coefficients facilitated effect size comparisons across variables. Model performance was evaluated using adjusted R2 values. Analyses were performed in SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp, USA), with two-tailed p < 0.05 considered significant.

-

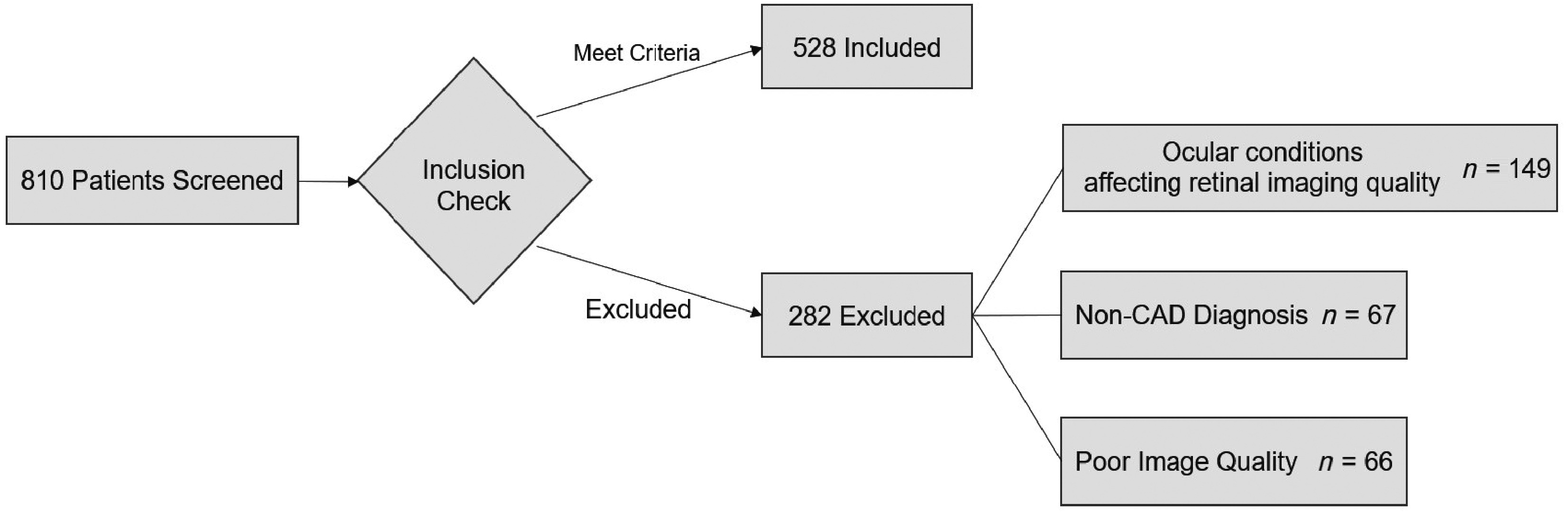

Among the 810 patients with coronary artery disease and angina who were initially enrolled, 528 (65.2%) met the inclusion criteria after excluding ineligible participants and poor-quality retinal images. Fig. 2 illustrates the participant screening process, including the distribution of excluded patients.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables as counts (percentages). The cohort had a mean age of 62.13 years, with 377 males (71.4%) and 151 females (28.6%). Hypertension was present in 152 patients (28.8%) and diabetes mellitus in 333 (63.1%). Smoking status included 315 nonsmokers (59.7%) and 213 current/former smokers (40.3%). The mean CRAE and CRVE were 0.023 papillary diameter (PD) and 0.031 PD, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

Mean SD Age, year 62.13 10.68 BMI, kg/m2 24.43 3.82 SBP, mmHg 126.31 13.20 DBP, mmHg 76.54 8.24 MAP, mmHg 92.69 10.05 PP, mmHg 49.77 14.18 Pulse, beats/minute 71.25 6.92 TG, mmol/L 1.54 0.84 TC, mmol/L 4.17 1.21 HDL-C, mmol/L 1.08 0.25 LDL-C, mmol/L 2.69 0.95 FBG, mmol/L 5.32 1.14 ALB, mmol/L 39.95 3.68 Creatinine, umol/L 93.87 36.59 hs-CRP,mg/L 6.36 9.99 α-HBDH, U/L 134.33 58.07 CK, U/L 131.79 163.44 CK-MB, U/L 7.82 11.96 LDH, U/L 202.26 73.29 cTnT, μg/L 0.21 0.91 Myo, ng/mL 38.63 32.09 NT-proBNP, pg/mL 609.08 1,301.76 HCY, μmol/L 11.09 3.04 D-D, mg/L 0.56 0.69 CRAE, PD 0.023 0.006 CRVE, PD 0.031 0.008 Gender Female n = 151 28.6% Male n = 377 71.4% Hypertension Absent n = 376 71.2% Present n = 152 28.8% Diabetes Absent n = 195 36.9% Present n = 333 63.1% Smoking Never n = 315 59.7% Current or former n = 213 40.3% Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD; categorical variables as counts (percentages). PD, papillary diameter. Hypertension was defined as a prior diagnosis with antihypertensive medication use, SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or DPB ≥ 90 mmHg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior physician diagnosis or the use of antidiabetic medications. Smoking was defined as current or former smoking. Regression analysis

-

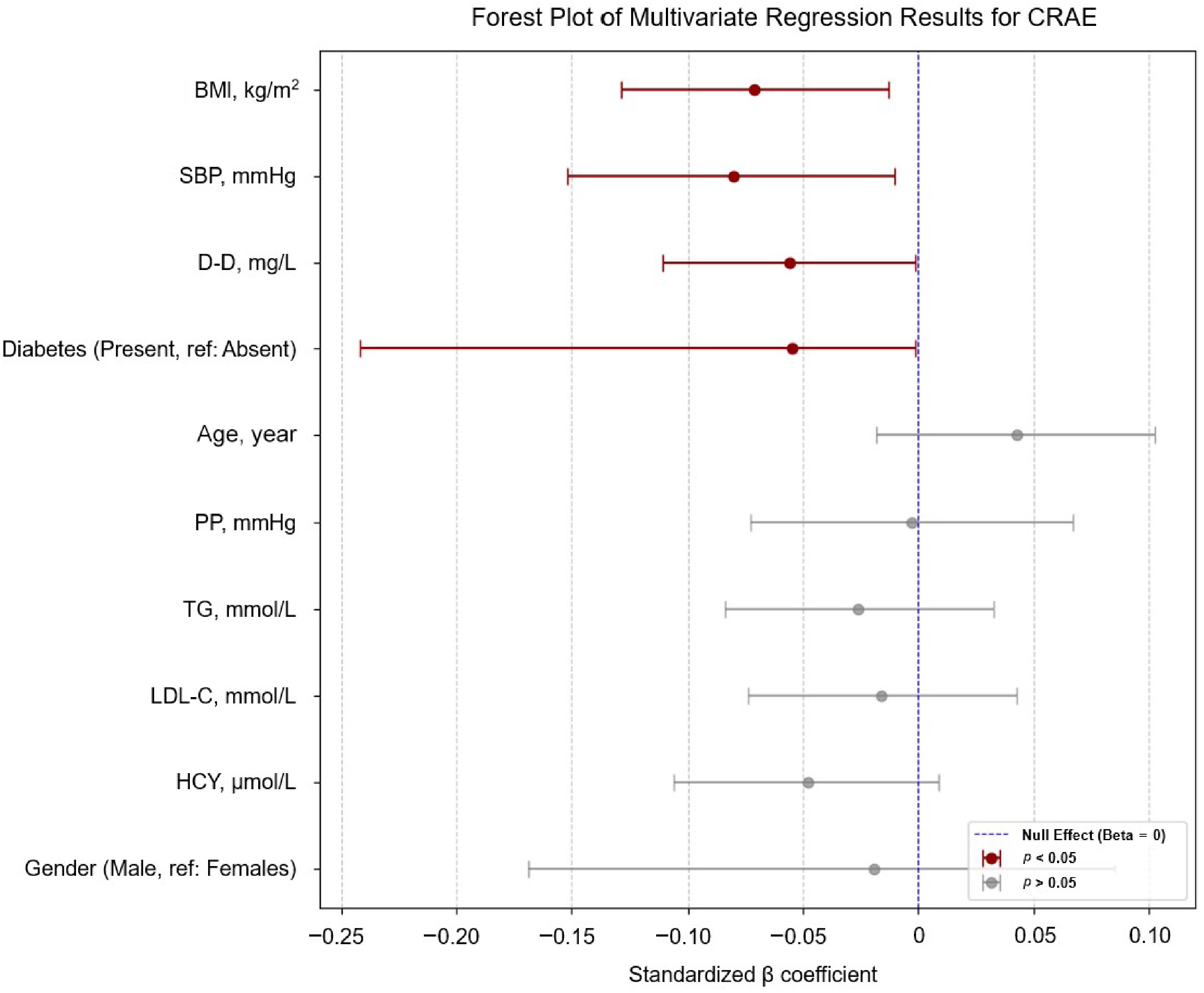

Tables 2 and 3 present the univariate and multivariate linear regression results for systemic clinical indicators associated with CRAE. The univariate analysis identified age, SBP, pulse pressure (PP), TC, LDL-C, HCY, and CRVE as significant predictors of CRAE (all p < 0.05). The multivariate analysis revealed independent associations between CRAE and BMI (β = −0.071, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.129 to −0.013, p = 0.016), SBP (β = −0.080, 95% CI: −0.152 to −0.010, p = 0.026), D-dimer (β = −0.056, 95% CI: −0.111 to −0.001, p = 0.047), diabetes status (β = −0.055, 95% CI: −0.242 to −0.001, p = 0.048), and CRVE (β = 0.761, 95% CI: 0.706 to 0.817, p < 0.001). All variables exhibited VIF < 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity.

Table 2. Univariate linear regression analysis of participants' clinical data and CRAE.

β 95% CI p Age, year −0.096 (−0.181, −0.010) 0.028* BMI, kg/m2 −0.020 (−0.106, 0.065) 0.640 SBP, mmHg −0.157 (−0.242, −0.073) < 0.001* DBP, mmHg −0.077 (−0.162, 0.009) 0.078 MAP, mmHg −0.083 (−0.169, 0.002) 0.056 PP, mmHg −0.131 (−0.216, −0.046) 0.002* Pulse, beats/min −0.077 (−0.162, 0.009) 0.078 TG, mmol/L −0.044 (−0.130, 0.041) 0.308 TC, mmol/L −0.102 (−0.187, −0.016) 0.020* HDL-C, mmol/L −0.019 (−0.105, 0.066) 0.656 LDL-C, mmol/L −0.104 (−0.189, −0.019) 0.017* FBG, mmol/L −0.074 (−0.160, 0.011) 0.088 ALB, mmol/L 0.028 (−0.058, 0.113) 0.525 Creatinine, μmol/L −0.051 (−0.137, 0.034) 0.239 hs-CRP, mg/L −0.007 (−0.093, 0.078) 0.866 α−HBDH, U/L −0.027 (−0.113, 0.059) 0.534 CK, U/L −0.018 (−0.103, 0.068) 0.684 CK-MB, U/L −0.056 (−0.141, 0.030) 0.201 LDH, U/L −0.037 (−0.122, 0.049) 0.398 cTnT, μg/L −0.041 (−0.127, 0.045) 0.347 Myo, ng/mL −0.009 (−0.094, 0.077) 0.842 NT-proBNP, pg/mL −0.004 (−0.090, 0.081) 0.924 HCY, μmol/L −0.101 (−0.187, −0.016) 0.020* D-D, mg/L −0.054 (−0.139, 0.032) 0.218 Gender Male (reference: Females) 0.045 (−0.144, 0.234) 0.642 Hypertension Present (reference: Absent) −0.146 (−0.323, 0.031) 0.105 Diabetes Present (reference: Absent) −0.172 (−0.360, 0.017) 0.074 Smoking Current or former (reference: Never) −0.057 (−0.252, 0.139) 0.570 CRVE, PD 0.769 (0.714, 0.824) < 0.001* * indicates p < 0.05. PD, papillary diameter; CI, confidence interval. Hypertension was defined as a prior diagnosis with antihypertensive medication use, SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior physician diagnosis or use of antidiabetic medications. Smoking was defined as current or former smoking. Table 3. Multivariable linear regression analysis of participants' clinical data and CRAE.

β 95% CI p VIF Age, year 0.043 (−0.018, 0.103) 0.166 1.250 BMI, kg/m² −0.071 (−0.129, −0.013) 0.016* 1.133 SBP, mmHg −0.080 (−0.152, −0.010) 0.026* 1.714 PP, mmHg −0.003 (−0.073, 0.067) 0.935 1.684 TG, mmol/L −0.026 (−0.084, 0.033) 0.391 1.169 LDL-C, mmol/L −0.016 (−0.074, 0.043) 0.599 1.156 HCY, μmol/L −0.048 (−0.106, 0.009) 0.101 1.145 D-D, mg/L −0.056 (−0.111, −0.001) 0.047* 1.061 Gender Male (reference: Females) −0.019 (−0.169, 0.085) 0.513 1.134 Diabetes Present (reference: Absent) −0.055 (−0.242, −0.001) 0.048* 1.030 CRVE, PD 0.761 (0.706, 0.817) < 0.001* 1.044 This multivariable model was adjusted for all variables listed in the table: Age, BMI, SBP, PP, TG, LDL-C, HCY, D-D, gender, diabetes status, and CRVE. * indicates p < 0.05. The coefficient of determination (R2) for the multivariate regression model was 0.611. CI, confidence interval; VIF, variance inflation factor; PD, papillary diameter. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior physician diagnosis or use of antidiabetic medications. The forest plots in Fig. 3 display the effect sizes of systemic indicators on CRAE.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the multivariable linear regression results for CRAE. Significant inverse associations with SBP (β = −0.080, 95% CI: −0.152 to −0.010), BMI (β = −0.071, −0.129 to −0.013), D-dimer (β = −0.056, −0.111 to −0.001), and diabetes status (β = −0.055, −0.242 to −0.001). Variables with p < 0.05 are emphasized with dark red; a legend indicates the significance levels (p < 0.05 and p > 0.05) and the null effect line (β = 0). We removed CRAE or CRVE from the vertical coordinates to maintain a clear focus on how other systemic health markers relate to the retinal vessel caliber.

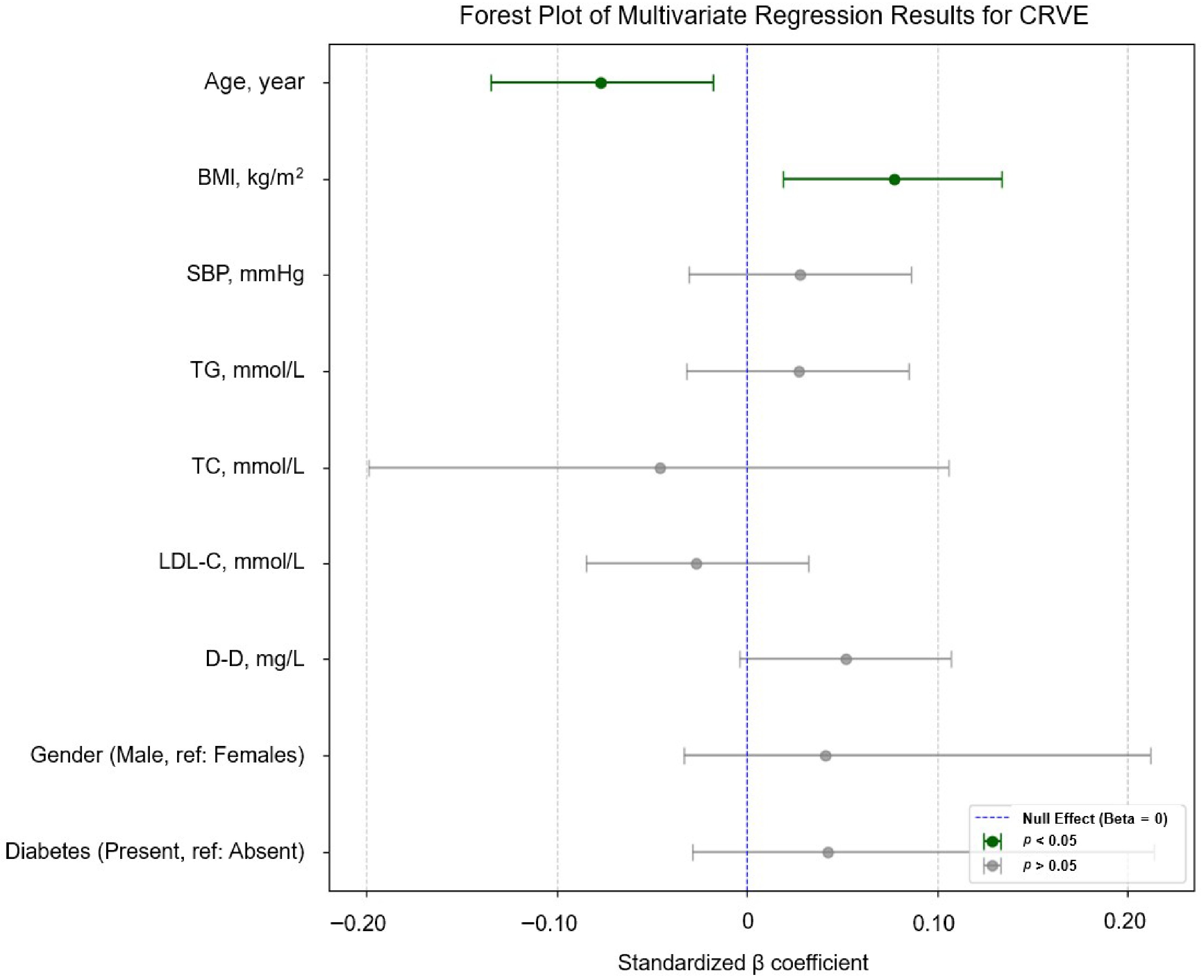

Similarly, Tables 4 and 5 show the regression results for CRVE. The univariate analysis demonstrated significant associations with age, SBP, TC, LDL-C, and CRAE (all p < 0.05). Multivariate analysis identified age (β = −0.077, 95% CI: −0.135 to −0.018, p = 0.011), BMI (β = 0.077, 95% CI: 0.019 to 0.134, p = 0.009), and CRAE (β = 0.772, 95% CI: 0.716 to 0.827, p < 0.001) as independent predictors of CRVE, with all VIF values < 5.

Table 4. Univariate linear regression analysis of participants' clinical data and CRVE.

β 95% CI p Age, y −0.131 (−0.216, −0.046) 0.003* BMI, kg/m² 0.025 (−0.061, 0.110) 0.571 SBP, mmHg −0.157 (−0.208, −0.038) 0.004* DBP, mmHg −0.035 (−0.121, 0.050) 0.417 MAP, mmHg −0.061 (−0.146, 0.025) 0.162 PP, mmHg −0.122 (−0.207, −0.037) 0.055 Pulse, beats/min −0.045 (−0.131, 0.041) 0.303 TG, mmol/L −0.008 (−0.094, 0.078) 0.856 TC, mmol/L −0.092 (−0.177, −0.006) 0.035* HDL-C, mmol/L −0.019 (−0.105, 0.067) 0.665 LDL-C, mmol/L −0.089 (−0.174, −0.003) 0.041* FBG, mmol/L −0.053 (−0.138, 0.033) 0.227 ALB, mmol/L 0.032 (−0.053, 0.118) 0.459 Creatinine, μmol/L −0.010 (−0.096, 0.075) 0.812 hs-CRP, mg/L 0.010 (−0.076, 0.096) 0.819 α−HBDH, U/L −0.028 (−0.114, 0.057) 0.516 CK, U/L 0.004 (−0.082, 0.090) 0.925 CK-MB, U/L −0.024 (−0.109, 0.062) 0.585 LDH, U/L −0.035 (−0.121, 0.050) 0.417 cTnT, μg/L −0.062 (−0.147, 0.024) 0.157 Myo, ng/mL −0.016 (−0.102, 0.069) 0.705 NT-proBNP, pg/mL −0.015 (−0.101, 0.071) 0.729 HCY, μmol/L −0.058 (−0.143, 0.028) 0.185 D-D, mg/L −0.003 (−0.088, 0.083) 0.953 Gender Male (reference: Females) 0.060 (−0.056, 0.322) 0.167 Hypertension Present (reference: Absent) −0.048 (−0.277, 0.078) 0.271 Diabetes Present (reference: Absent) −0.019 (−0.230, 0.147) 0.666 Smoking Current or former (reference: Never) 0.035 (−0.116, 0.275) 0.426 CRAE, PD 0.769 (0.714, 0.824) <0.001* * indicates p < 0.05. PD, papillary diameter; CI, confidence interval. Hypertension was defined as a prior diagnosis with antihypertensive medication use, SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior physician diagnosis or use of antidiabetic medications. Smoking was defined as current or former smoking. Table 5. Multivariable linear regression analysis of participants' clinical data and CRVE.

β 95% CI p VIF Age, y −0.077 (−0.135, −0.018) 0.011* 1.168 BMI, kg/m2 0.077 (0.019, 0.134) 0.009* 1.132 SBP, mmHg 0.028 (−0.031, 0.086) 0.355 1.158 TG, mmol/L 0.027 (−0.032, 0.085) 0.373 1.164 TC, mmol/L −0.046 (−0.199, 0.106) 0.550 1.820 LDL-C, mmol/L −0.027 (−0.085, 0.032) 0.367 1.148 D-D, mg/L 0.052 (−0.004, 0.107) 0.068 1.050 Gender Male (reference: Females) 0.041 (−0.033, 0.212) 0.151 1.040 Diabetes Present (reference: absent) 0.042 (−0.029, 0.214) 0.136 1.025 CRAE, PD 0.772 (0.716, 0.827) < 0.001* 1.050 This multivariable model was adjusted for all variables listed in the table: Age, BMI, SBP, TG, TC, LDL-C, D-D, gender, diabetes status, and CRAE. * indicates p < 0.05. The coefficient of determination (R2) for the multivariate regression model was 0.598. CI, confidence interval; VIF, variance inflation factor; PD, papillary diameter. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior physician diagnosis or use of antidiabetic medications. Similarly, the forest plots in Fig. 4 displays the effect sizes of the systemic indicators on CRVE.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the multivariable linear regression results for CRVE, showing an independent negative correlation with age (β = –0.077, –0.135 to –0.018) and a positive correlation with BMI (β = 0.077, 0.019–0.134) Variables with p < 0.05 are indicated in dark green; the legend indicates the significance levels (p < 0.05 and p > 0.05) and the null effect line (β = 0). We removed CRAE or CRVE from the vertical coordinates to maintain a clear focus on how the other systemic health markers relate to the respective retinal vessel caliber.

In summary, CRAE in stable angina patients was predominantly associated with SBP, diabetes status, BMI, and plasma D-dimer levels, whereas CRVE correlated primarily with age and BMI.

-

This study systematically investigated the links between retinal vascular parameters and a wide range of systemic indicators in patients with stable angina. Our key findings demonstrate that in this specific population, narrower CRAE is independently associated with higher SBP, the presence of diabetes, higher BMI, and elevated D-dimer levels. Conversely, CRVE was found to be independently associated with age and BMI. These findings suggest that retinal vascular caliber serves as a reflector of the systemic hemodynamic and metabolic stressors inherent to stable angina, offering a potential noninvasive window into the microcirculatory status of these patients. Although these associations were statistically significant, it is important to note that the standardized effect sizes (β coefficients) for the individual systemic factors were modest. This indicates that though these factors are independently associated with retinal vascular changes, their individual predictive power for microvascular caliber is limited. Furthermore, the high coefficient of determination (R2) of our multivariate models is largely attributable to the strong intrinsic correlation between CRAE and CRVE, which reflects the coupled hemodynamics within the retinal vascular network[19]. The independent contribution of the systemic factors to the explained variance, though significant, is more circumscribed. Therefore, the clinical value of these findings may lie in the collective pattern of association, reflecting the integrated systemic burden on the microvasculature, rather than the strength of any single variable.

Our multivariable analysis identified several key factors associated with arteriolar narrowing (reduced CRAE) in patients with stable angina. The strong positive correlation observed between CRAE and CRVE (β = 0.761, p < 0.001) suggests a coupled hemodynamic relationship, where changes in one vessel type are mirrored in the other to maintain circulatory equilibrium[19].

The inverse association between CRAE and both SBP and BMI aligns with established knowledge[8,20], likely reflecting the multifactorial interplay of hemodynamic, metabolic, and cardiovascular factors in patients with stable angina[21,22]. Hemodynamic stressors not only compromise microcirculatory structural integrity but also exacerbate atherosclerosis and post-infarction myocardial remodeling via excessive activation of hormonal systems (e.g., angiotensin II, norepinephrine)[23]. In the context of stable angina, where patients have both hypertension and obesity, these factors create a state of chronic hemodynamic stress and inflammation[24]. This environment promotes endothelial dysfunction and impairs nitric oxide's bioavailability, leading to systemic vasoconstriction that is visibly reflected in the retinal arterioles[25].

Similarly, the presence of diabetes was also a significant predictor of narrower CRAE in our cohort. Supporting this, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study linked generalized arteriolar narrowing to the development of diabetes, whereas the Beaver Dam Eye Study identified smaller arteriolar caliber as an independent predictor of Type 2 diabetes[26]. Although diabetic retinopathy is a well-known complication, our findings are particularly relevant to stable angina. They suggest that even after accounting for other factors, the metabolic dysregulation inherent to diabetes exerts an independent, constrictive effect on the microvasculature, potentially exacerbating the microcirculatory impairment caused by chronic myocardial ischemia[27,28]. Conversely, some studies paradoxically associate wider arterioles with hyperglycemia, highlighting the population's heterogeneity in diabetes risk profiles[29,30].

Notably, we also found a significant association between elevated D-dimer levels and reduced CRAE. D-dimer is a marker of hypercoagulability. In stable angina, chronic myocardial ischemia can trigger a low-grade inflammatory state that activates coagulation cascades[31,32]. Our finding links this prothrombotic state directly to microvascular structural changes in the retina, suggesting that retinal arteriolar narrowing may reflect not just hemodynamic stress but also an underlying thrombo-inflammatory process central to the pathophysiology of coronary artery disease[33]. Recent research has also confirmed that D-dimer is associated with coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease[34].

The associations with retinal venular caliber (CRVE) revealed a different pattern of influencing factors. CRVE was inversely associated with age but positively associated with BMI. The age-related venular narrowing observed in our stable angina cohort contrasts with the findings in some general population studies, which may point to a disease-specific aging process in the venous system of these patients, where chronic inflammation accelerates venous wall fibrosis and reduces compliance[35,36]. The positive link with BMI, however, is consistent with broader findings and likely reflects obesity-related inflammation and fluid shifts affecting the more distensible venous side of the circulation[37,38].

These findings hold significant potential for the clinical management of stable angina. Our results suggest that automated retinal imaging can capture the quantitative parameters of the microvasculature. The identified independent associations between CRAE/CRVE and key systemic indicators (e.g., SBP, diabetes status, D-dimer) support the concept that retinal vascular caliber reflects systemic pathological processes. This collective pattern of associations, rather than a single parameter, might offer a unique, noninvasive window into the systemic microvascular burden in stable angina patients. However, given the modest effect sizes of the individual factors, their utility for precise risk stratification beyond established metrics requires further validation in longitudinal studies. By demonstrating specific correlations, our study provides insights into how systemic pathologies manifest in the microcirculation of stable angina patients. For example, the link with D-dimer suggests retinal analysis could offer clues about a patient's underlying prothrombotic state. This study lays the groundwork for future prospective research. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if dynamic changes in retinal vascular caliber can predict adverse cardiovascular events or track responses to therapeutic interventions in stable angina. Furthermore, integrating retinal analysis with other imaging modalities, such as optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), could provide an even more comprehensive assessment of microvascular health[39].

This study has several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional observational study, it cannot determine causal relationships, and further prospective studies are needed to verify these associations. Our study did not perform disease staging or grouping for stable angina for various reasons. Future prospective studies incorporating standardized angina staging (e.g., the Canadian Cardiovascular Society [CCS] classification) are essential to address two critical questions: (1) Whether retinal microvascular parameters can discriminate between early (CCS I–II) and advanced (CCS III–IV) stable angina subgroups[40] and (2) how dynamic changes in retinal vasculature track with therapeutic interventions or disease progression.

Second, although we identified several statistically significant independent associations, the effect sizes of the systemic factors were modest. This, coupled with the fact that a large portion of the explained variance in our models was driven by the internal correlation between CRAE and CRVE, suggests that the standalone clinical utility of these specific associations for predicting individual risk may be limited. The findings primarily demonstrate a proof of concept that these systemic factors are linked to the retinal microvasculature in this patient population.

Third, our cohort included patients with systemic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes, which are known to impact the retinal microvasculature. Although we adjusted for these conditions as covariates in our multivariable models, we did not conduct a sensitivity analysis excluding these participants. Such an analysis, albeit valuable for confirming the robustness of our findings, was challenging within the scope of this cross-sectional study because of concerns about reduced statistical power in a smaller subgroup. We recommend that future, larger prospective studies incorporate such sensitivity analyses to enhance the reliability of the findings and better isolate the microvascular changes attributable to stable angina.

Furthermore, the associations reported between systemic indicators and retinal vessel calibers, though statistically significant at the conventional p < 0.05 threshold and adjusted for multiple confounders, should be interpreted in the context of the number of comparisons made. The modest effect sizes and the fact that some p-values are close to 0.05 (e.g., for D-dimer and diabetes status with CRAE) indicate that these findings are potentially vulnerable to Type I errors. We did not apply a formal multiplicity correction (e.g., Bonferroni), as our analysis was based on a prespecified set of variables chosen for their clinical relevance, and such corrections can be excessively conservative for exploratory studies, increasing the risk of dismissing true but modest effects (Type II errors)[41,42]. Therefore, the associations with systemic factors are best viewed as hypothesis-generating. Their validity is supported by their biological plausibility and alignment with the existing pathophysiological knowledge, but future prospective studies are necessary to confirm their robustness and clinical utility. In contrast, the strong association between CRAE and CRVE, a well-documented physiological coupling, was highly robust (p < 0.001).

Finally, the samples of this study were derived from specific hospitals and departments, and thus there may be selection bias, and the results may not be fully generalizable to other populations. Although detailed ocular histories were collected, these data served exclusively as exclusion criteria to ensure retinal image quality, rather than as analytical variables. Consequently, their distribution was not included in the primary results. Our analysis did not include certain sociodemographic data collected via the questionnaire, such as education level and history of alcohol consumption. Although our primary focus was on clinical and biochemical markers, we acknowledge that these factors could act as potential confounders, and their exclusion from the analysis is a limitation of this study. The deep learning system can provide accurate and consistent retinal vascular parameter measurements; however, it may still be affected by factors such as image quality and disease status.

-

In patients with stable angina, this study identified statistically significant, albeit modest, associations between retinal vascular calibers and key systemic indicators. Key findings include the following. CRAE in stable angina patients correlates with SBP, diabetes status, BMI, and plasma D-dimer levels; CRVE demonstrates primary associations with age and BMI. These findings demonstrate that retinal microvascular parameters reflect the cumulative burden of systemic hemodynamic and metabolic stressors. Although these associations provide insights into the systemic nature of microvascular changes in stable angina, their clinical utility for individual risk prediction or disease monitoring is yet to be determined. Future large-scale, prospective studies are essential to validate these findings and explore their potential role in clinical practice.

-

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region on 25 July 2024 (approval number: Ethics-KY-IIT-2024-98). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants.

The authors thank all patients and clinical staff, as well as the following sources of funding support: Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023J011581) and Specialized Key Discipline Construction Projects of the 14th Five-Year Plan in Chancheng District, Foshan City.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zheng X, Zhang C, Lei D, and Cui L; data collection: Zhou Y, Tang N, Tang F, and Shen C; analysis and interpretation of results: Zheng X, Zhang C, Lei D, and Xu F; draft manuscript preparation: He W, Xu F, and Cui L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Ling Cui, upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Xiaozhan Zheng, Chi Zhang, Daizai Lei, Yuchen Zhou

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng X, Zhang C, Lei D, Zhou Y, Tang N, et al. 2025. Relationship between systemic indicators and retinal vessel caliber in patients with stable angina. Visual Neuroscience 42: e025 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0024

Relationship between systemic indicators and retinal vessel caliber in patients with stable angina

- Received: 12 May 2025

- Revised: 05 September 2025

- Accepted: 12 September 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: The assessment of microcirculation in patients with stable angina holds significant value for monitoring disease progression and managing adverse cardiovascular events. This study systematically investigates the associations between central retinal arteriolar equivalent (CRAE) and central retinal venular equivalent (CRVE), with multidimensional systemic indicators in this population, to evaluate the potential of retinal vascular parameters as indicators of systemic microcirculatory status, thereby laying the groundwork for future noninvasive monitoring approaches. A cross-sectional study design was adopted, enrolling 528 patients diagnosed with stable angina between June 2022 and October 2023 (mean age: 62.13 years, 71.4% male). Retinal vessel calibers were quantified from fundus photographs using an artificial intelligence (AI)-based system that calculates CRAE and CRVE from the six largest vessels within standardized peripapillary zones. The system demonstrated excellent agreement with manual measurements (intraclass correlation coefficients: 0.82–0.95). Multivariable linear regression analyses, adjusted for key demographic and clinical confounders (including age, gender, body mass index [BMI], blood pressure, lipid profiles, and smoking status), were conducted to examine independent associations with systemic indicators. Significant correlations were found between CRAE and BMI (β = −0.071, p = 0.016), systolic blood pressure (β = −0.080, p = 0.026), D-dimer (β = −0.056, p = 0.047), diabetes mellitus (β = −0.055, p = 0.048), and CRVE (β = 0.761, p < 0.001). CRVE was significantly associated with age (β = −0.077, p = 0.011) and BMI (β = 0.077, p = 0.009). In conclusion, retinal vessels reflect the impact of systemic pathological stressors and support the potential of retinal analysis as a noninvasive approach to assess microcirculatory characteristics in this population.