-

The discipline of ophthalmology combines theoretical knowledge with high-level practical skills, encompassing diagnosis, treatment, and surgical intervention[1]. However, the evolution of modern medicine has introduced several challenges to traditional ophthalmological education and clinical practice, including escalating training costs, the scarcity of internship opportunities, and the limitations of conventional teaching models[2].

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is profoundly transforming ophthalmology, with significant potential in both clinical practice and education. Clinically, AI shows promise in disease screening, diagnosis, treatment planning, and surgical assistance[3]. In ophthalmological education, AI integrates virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to create immersive learning environments, enabling students to practice surgical procedures safely and repeatedly, thereby enhancing their clinical skills[4−5]. AI-assisted teaching systems, such as intelligent tutoring and adaptive learning platforms, also optimize outcomes through personalized pathways and real-time feedback[6]. Despite addressing traditional educational challenges and compensating for resource limitations, the implementation of AI faces hurdles including data quality, privacy protection, and ethical and legal considerations[7].

Thus, a systematic review of AI applications in ophthalmology education is necessary to summarize the existing research, analyze its advantages and limitations, and explore future development directions. The contents will cover the main ways that AI technology is applied in teaching ophthalmology. This review examines AI's integration into ophthalmological education, evaluating its current roles and future trajectories in improving educational quality, disease screening/diagnostic capabilities, and the implementation of VR/AR technology.

-

A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines[8] with the aim of comprehensively summarizing advancements in AI for clinical applications and education in ophthalmology. Systematic searches were performed in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science for publications released between 1 January 2019 and 31 May 2025, using combinations of the following keywords and their semantic variants: ("ophthalmology" OR "oculopathy" OR "optometry" OR "ophthalmological" OR "ophthalmologist" OR "orthoptist") AND ("artificial intelligence" OR "deep learning" OR "machine learning" OR "neural network") AND ("teaching" OR "education"). The full detailed search strategies, including the specific query syntax, Boolean operators, and filters for each database, are provided in Supplementary Table S1 to ensure reproducibility and transparency.

Literature selection and inclusion criteria

-

The inclusion criteria were as follows: original research with full text available; studies focusing on ophthalmology-centered teaching and training, rather than on ophthalmic diseases; research involving the use of AI technology, including deep learning, machine learning or neural networks; and English as the publication language. The exclusion criteria screened out literature unrelated to the research topic; conference summaries; nonoriginal research such as editorials; and reviews or case reports. After preliminary screening of the literature, the literature that met the inclusion criteria were further screened and data extracted.

Selection process recording

-

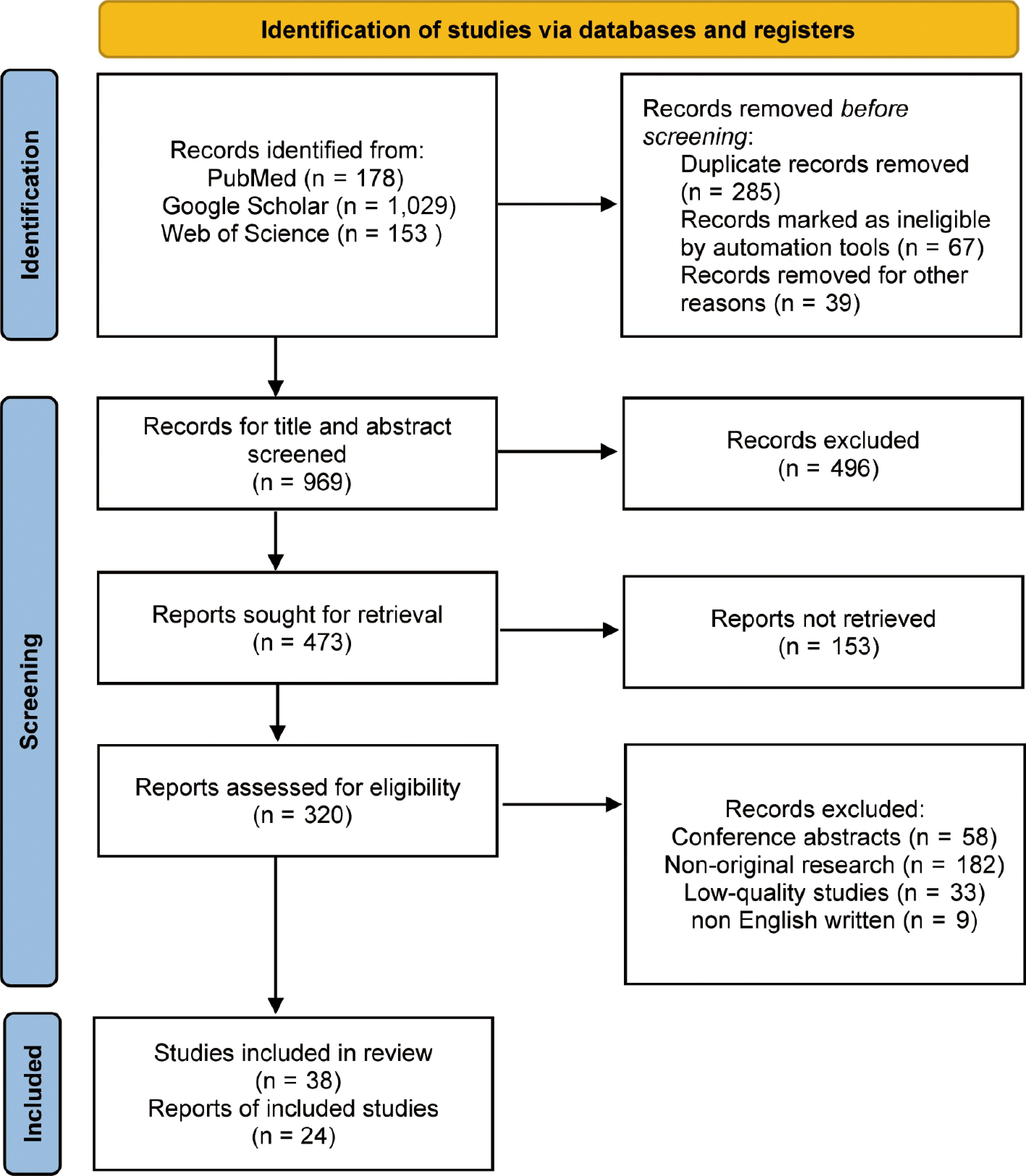

After deleting all duplicate records, title and abstract screening was conducted by two independent researchers (Lu Yuan and Kai Jin), and was excluded records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full-text screening of the remaining records was conducted to further evaluate whether they met the inclusion criteria. The detailed breakdown of the search results and the number of studies excluded at each stage is presnted visually (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review, including searches in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science.

Data extraction and analysis

-

To systematically summarize the application status and effect of AI in ophthalmology, we extracted the following information: research design, sample size, AI technology types, application fields, main findings, and conclusions. The data were classified according to the application of AI in various ophthalmic diseases, including but not limited to "diabetic retinopathy", "glaucoma", "age-related macular degeneration", "retinopathy of prematurity", "cataract", "keratopathy", "xerophthalmia", and "ocular tumors (such as retinoblastoma, ocular melanoma)". The extracted data were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively, utilizing descriptive statistical methods and graphical presentations to enhance clarity and understanding.

Quality evaluation

-

The quality of the selected studies was assessed by adopting the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). The Cochrane tool was applied to evaluate six aspects such as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding method, blinding method in evaluating the results, incomplete result data, and selective reporting. The risk of bias in each field was rated as low, high, or unclear. NOS was utilized to evaluate the selectivity (four stars), comparability (two stars), and results (three stars), and a total score of nine stars indicated the highest quality. Each evaluation was conducted independently by two reviewers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion, and was arbitrated by a third reviewer if necessary. Among the research included, 25% had a high risk of bias in at least one field, and 75% were rated as low-risk. NOS scores ranged from 6 to 9 points, with an average score of 7.8 points, indicating that the overall quality of the research was at an upper-middle level. Supplementary Table S2 displays the risk of bias assessment and quality scores for each included study.

Data analysis

-

Quantitative and qualitative methods were used to analyze the extracted data. In contrast, qualitative analysis was used to summarize the effects and challenges of AI in ophthalmological education, providing a comprehensive view of its impact and potential areas for improvement.

Included literature and basic information

-

In this systematic review, 38 studies were finally included after multiple rounds of screening through a strict process. Firstly, 1,360 related studies were retrieved from multiple databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science). After removing duplicates and preliminary screening, some repetitive, irrelevant, or substandard articles were eliminated. Finally, the quality and relevance of the included studies were confirmed by full-text evaluation. Among the 38 articles, 24 were detailed analysis reports. These articles covered different research types and designs, such as randomized controlled trials and observational studies, involving different sample sizes, ensuring the representativeness and external validity of the research results. The included studies mainly discussed the effects of specific intervention measures, evaluations of prognosis, and related mechanisms of the disease, which provided sufficient data support for this systematic evaluation. Some key studies could be used for empirical research, as shown in Table 1. Detailed information for all included studies is consolidated in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 1. Key empirical articles on AI in clinical education on ophthalmology (2019–2025).

Training objective Trainees AI type AI educational role Key findings Key notes Publication AI-assisted problem-based learning (PBL) in ophthalmological education Medical students (clerkship) AI tutor system Empowering the learner Enhanced discussion efficiency and depth of understanding; students reported A positive learning experience Integration of PBL with AI-guided discussions Wu et al.[9] Training for identification of pathologic myopia Junior ophthalmology residents Image interpretation model with a feedback platform Support teaching AI-assisted feedback improved diagnostic accuracy and enhanced the quality of residents' reports AI-labeled images used as visual teaching aids Fang et al.[10] Personalized ophthalmology residency training Ophthalmology residents (all years) Recommendation system with adaptive learning pathways Support teaching Adaptive learning system improved the overall pass rate by tailoring content to individual weaknesses Real-time performance assessment used to dynamically adjust learning modules Muntean et al.[11] Enhancing AI literacy in medical imaging through a flipped classroom approach Undergraduate medical students (preclinical) AI-based flipped classroom and imaging tools Direct teaching Post-course AI literacy and confidence significantly improved in students Blending AI tools with flipped pedagogy to foster conceptual and applied understanding Laupichler et al.[12] Training for diabetic retinopathy grading using an AI reading label system Junior ophthalmology residents and medical students (clinical years) AI reading label system Direct teaching Improved grading accuracy and efficiency; fewer classification errors Structured training workflows with built-in performance monitoring Han et al.[13] Customized learning instructions and literature search using large language models (LLMs) Ophthalmology interns and junior residents LLM Empowering the learner Custom prompts and enhanced retrieval significantly improved literature comprehension, diagnostic reasoning, and self-directed learning efficiency Interactive dialogue, personalized guidance, and language generation for simulated clinical education Sonmez et al.[14] Training for manual diabetic retinopathy detection using an AI grading system Medical students and primary care providers Automated grading and feedback system Support teaching AI feedback reduced training time and lowered error rates by 20% Error flagging and performance tracking through AI-enhanced platforms Xu et al.[15] Training in surgical phase identification in cataract surgery videos Senior ophthalmology residents Video-based machine learning and deep learning Direct teaching Effective phase identification supports standardized procedural training Surgical phase data support structured training and feedback loops Yu et al.[16] Training in surgical instrument recognition in cataract procedures Cataract surgery fellows AI tool annotation model Support teaching Higher instrument recognition accuracy contributes to improved assessment of skills AI-generated annotations improve operative training and evaluation metrics Al Hajj et al.[17] Improving retinal disease recognition skills through training with synthetic images Medical students and beginner retina specialists Image-generative AI+ classification model Direct teaching Training with AI-generated images led to 40% improvement in recognition efficiency and reduced learning duration GAN-generated pathological images offer superior simulation-based training compared with traditional case studies Tabuchi et al.[18] -

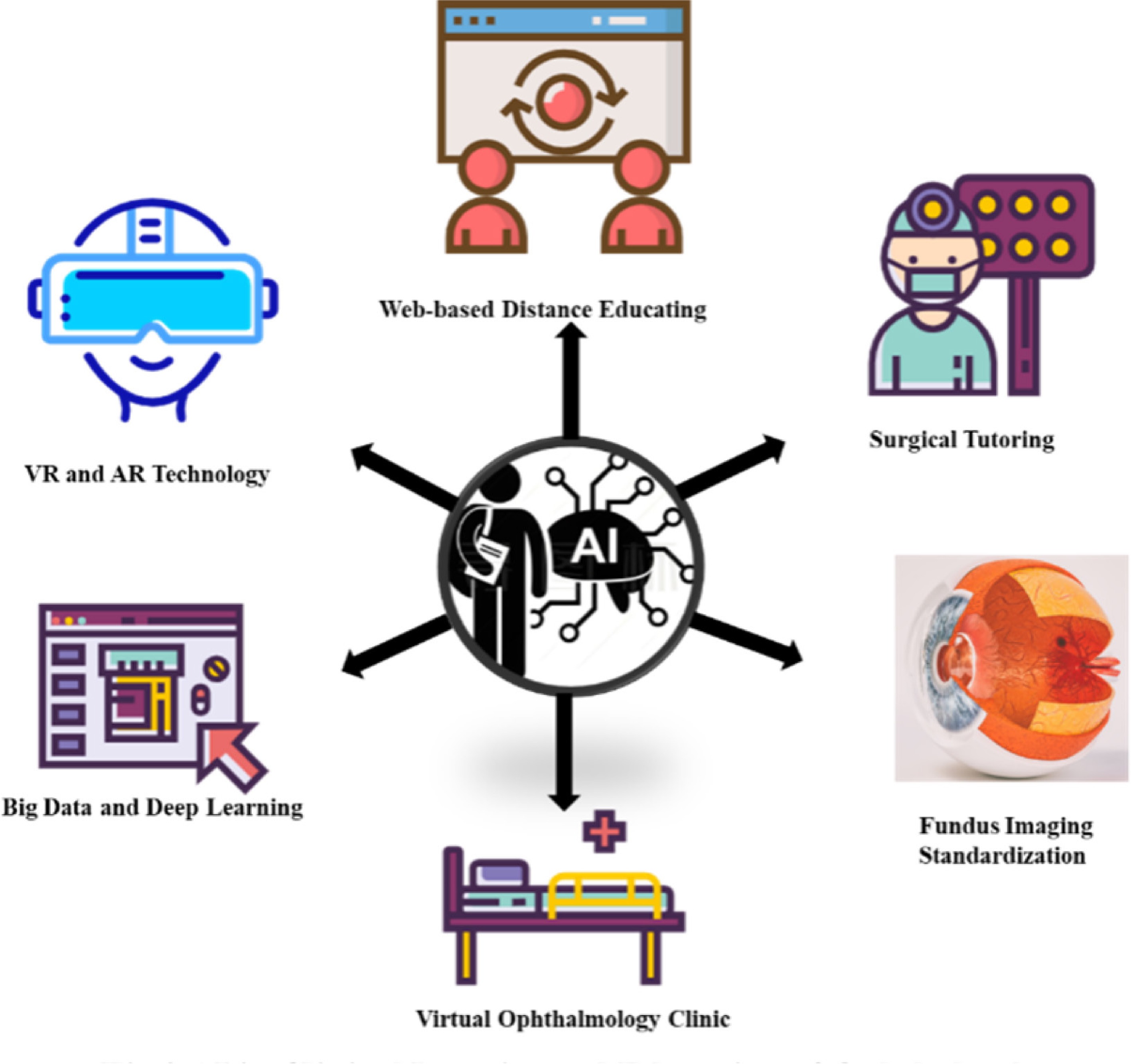

Figure 2 summarizes the six primary application domains identified in this systematic review, encompassing technological tools such as VR and AR and clinical support systems like Fundus Imaging Standardization. AI technology enhances surgical precision and safety. By using an AR ophthalmoscope, medical students can perform an indirect fundus examination without mydriasis, and avoid phototoxicity caused by long-term exposure to light during training[19]. Additionally, a smart surgical tutoring system developed by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich simulates the procedure of peeling the retinal internal limiting membrane using AR technology, facilitating the mastery of surgical skills for clinical interns[20]. Moreover, AI platforms like ChatGPT can create virtual patient scenarios, allowing learners to practice diagnosing and managing ophthalmic diseases in a risk-free environment[21].

Academic exchange and cooperation platforms

-

Platforms like the Global Education Network for Retinopathy of Prematurity (GEN-ROP) change ophthalmological education, as it offers a web-based distance education module[22]. This initiative improves the diagnostic skills of ophthalmology residents and promotes communication among physicians. This networking enhances learning and cooperation across different regions, ultimately improving patient care in ophthalmology[23].

Auxiliary uses of AI in clinical ophthalmology

Auxiliary ophthalmology diagnosis education

-

The integration of AI in ophthalmological education has markedly improved the effectiveness of auxiliary diagnosis education. AI systems can efficiently analyze fundus photographs and assist medical students to identify and understand various fundus lesions. The DeepMind Health project, developed by Google in collaboration with the American Academy of Ophthalmology, uses AI algorithms to train the model on many images of diabetic retinopathy, and achieves a highly accurate diagnosis[24]. By analyzing abundant clinical data and medical literature, Watson[25] helps doctors diagnose complex ophthalmic diseases such as macular degeneration more accurately. Medical students can also understand the pathological mechanism of the disease via the Watson Health system, obtain key information, and apply this knowledge for clinical decision-making[26].

Teaching support tools

-

Teaching support tools leveraging AI technology have also transformed ophthalmological education. One notable example is the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) for creating synthetic optical coherence tomography (OCT) images, which serve as educational resources for teaching image-based diagnosis of macular diseases[27]. The research team from the University of California has developed an AI fundus imaging analysis software tool, which can automatically detect and label the key pathological features in fundus images, such as vascular abnormalities, exudates, etc., and provide standardized learning materials for medical students[28,29].

Virtual patients and simulation training

-

Virtual patients and simulation training represent a new application of AI in ophthalmological education. The introduction of virtual ophthalmology clinics (VOCs) offers a highly simulated clinical learning environment for medical students, allowing them to practice diagnosis and management in a risk-free setting[30]. In the British Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Program, the study found that virtual clinics effectively reduce service requirements and waiting times while maintaining high-quality nursing, and provide patients with efficient diagnosis and management methods[31].

Distance education and collaboration

-

Remote consultations now serve as real-time teaching platforms, allowing specialists to demonstrate diagnostic reasoning for underserved populations while their trainees observe. Simultaneously, telemonitoring enables guided procedural practice across distance, effectively turning clinical service delivery into experiential learning that scales surgical exposure and refines diagnostic competencies[32]. AI technology plays a crucial role in enhancing ophthalmological distance education and services. For instance, the successful implementation of Lions Outback Vision project in remote areas provides experience for ophthalmic telemedicine services[33]. The project uses real-time video conferencing and "store-and-forward" mode to cover a total of 51 ophthalmic telemedicine service communities, significantly improving ophthalmic medical services in remote and Indigenous communities and effectively overcoming geographical constraints. Long et al.[34] developed an innovative AI agent model that leverages personalized predictions and telemedicine capabilities, introducing a prediction–telemedicine cloud platform designed for the long-term management of cataract patients. This integration of AI in telemedicine not only enhances educational outreach but also optimizes patient care in underserved areas.

Application of AI in screening and diagnosis of ophthalmic diseases and its influence on teaching

Application of AI in the screening and diagnosis of ophthalmic diseases

-

The application of AI and deep learning (DL) technology in the analysis of fundus photographs, visual field tests, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images has significantly improved the capacity for early detection of diabetic retinopathy (DR), wet age-related macular degeneration (w-AMD), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and glaucoma[35]. The research report of Abràmoff et al. showed that the sensitivity and specificity of the DL algorithm for the detection of DR were up to 96.8% and 87%[36]. The DL model could efficiently detect lesions such as geographic atrophy and w-AMD, and provide quantitative OCT biomarkers[37]. The Pegasus DL system is superior to most ophthalmologists in the diagnosis of glaucomatous optic neuropathy, and the AI system helps early detection and progression monitoring by analyzing retinal nerve fiber layers' thickness, intraocular pressure, and visual field data[38]. Quantitative analysis of the drusen volume and hyperreflective lesions by an AI algorithm showed a correlation with disease progression[39,40].

Influence of AI in teaching ophthalmology

-

AI technology makes the teaching content richer and more diversified. Students can understand the diversity and complexity of different diseases by accessing massive AI analysis results. It can analyze the learning data and behavior pattern of students, identify learning difficulties and interest points, and provide students with customized learning resources and teaching programs[41]. The Duke Institute of Health Innovation project has demonstrated the potential of AI in personalized education by identifying predictors of the early stages of sepsis through the use of AI systems[42].

VR, AR, and intelligent teaching systems in ophthalmological education

Practical effects of VR technology

-

The application of VR technology in ophthalmology encompasses various areas, including surgical training, visual rehabilitation, disease diagnosis, and patient education by creating an immersive and strongly interactive virtual environment[43]. Dyer et al.[44] used VR technology to allow medical students to experience the daily life of elderly patients with macular degeneration in an immersive way, and enhance students' understanding of the influence of the disease on patients. The Eyesi Surgical Simulator is a popular tool in medical schools and hospitals, providing realistic surgical scenarios and real-time feedback to enhance students' surgical skills and safety[45]. Using VR glasses to watch surgical videos can enhance the viewers' sense of immersion, whereas three-dimensional (3D) surgical videos record the 3D structural information of the surgery, further enriching learning and training materials.

Practical effects of AR technology

-

AR technology has significant advantages in the field of ophthalmology. From diagnosis and treatment to education and training, AR technology is changing the traditional ophthalmic medical model[46]. AR technology provides students with a more intuitive learning experience by superimposing virtual information over the real world. During cataract surgery, an AR system can superimpose preoperative planning and real-time images to help doctors with accurate location and operation and reduce the intraoperative risks[47]. The SimEdge SA ophthalmic VR tutoring system and disease simulator allows trainees to perform indirect fundus examinations to help identify early signs of eye diseases such as glaucoma and macular degeneration[48]. Additionally, stereoscopic 3D AR applications provide detailed virtual representations of eye structures and diseases, helping students grasp and master ophthalmic examination techniques more effectively[49].

Practical effects of intelligent auxiliary teaching systems

-

An intelligent auxiliary teaching system provides a personalized learning path and real-time feedback through AI technology, which significantly improves the learning efficiency of and effects on students. Researchers have developed a clinical trial matching system using natural language processing technology, which can quickly match appropriate patients for clinical trials by analyzing clinical trial databases and patients' historical medical records and clinical data[50]. Additionally, thermography analysis indicates that AI demonstrates diagnostic reasoning akin to that of physicians in identifying fundus diseases[51]. Wei et al.[52] used virtual fundus photographs generated a GAN model, and these photographs were not different from real fundus photographs in terms of detail and are suitable for ophthalmological education and training of beginner doctors.

These advances in AI not only improve diagnostic accuracy but also support the development of targeted treatment strategies, aligning with the objectives of personalized medicine in the diagnosis and management of age-related macular degeneration (AMD)[40]. Traditional medical education mainly depends on descriptions of the disease in textbooks, but in the future, the use of AI technology to enable medical students to experience the effects of diseases may become an effective means to enhance medical teaching.

Advantages and disadvantages of AI technology in improving the quality of teaching ophthalmology and the skills of students

Advantages

-

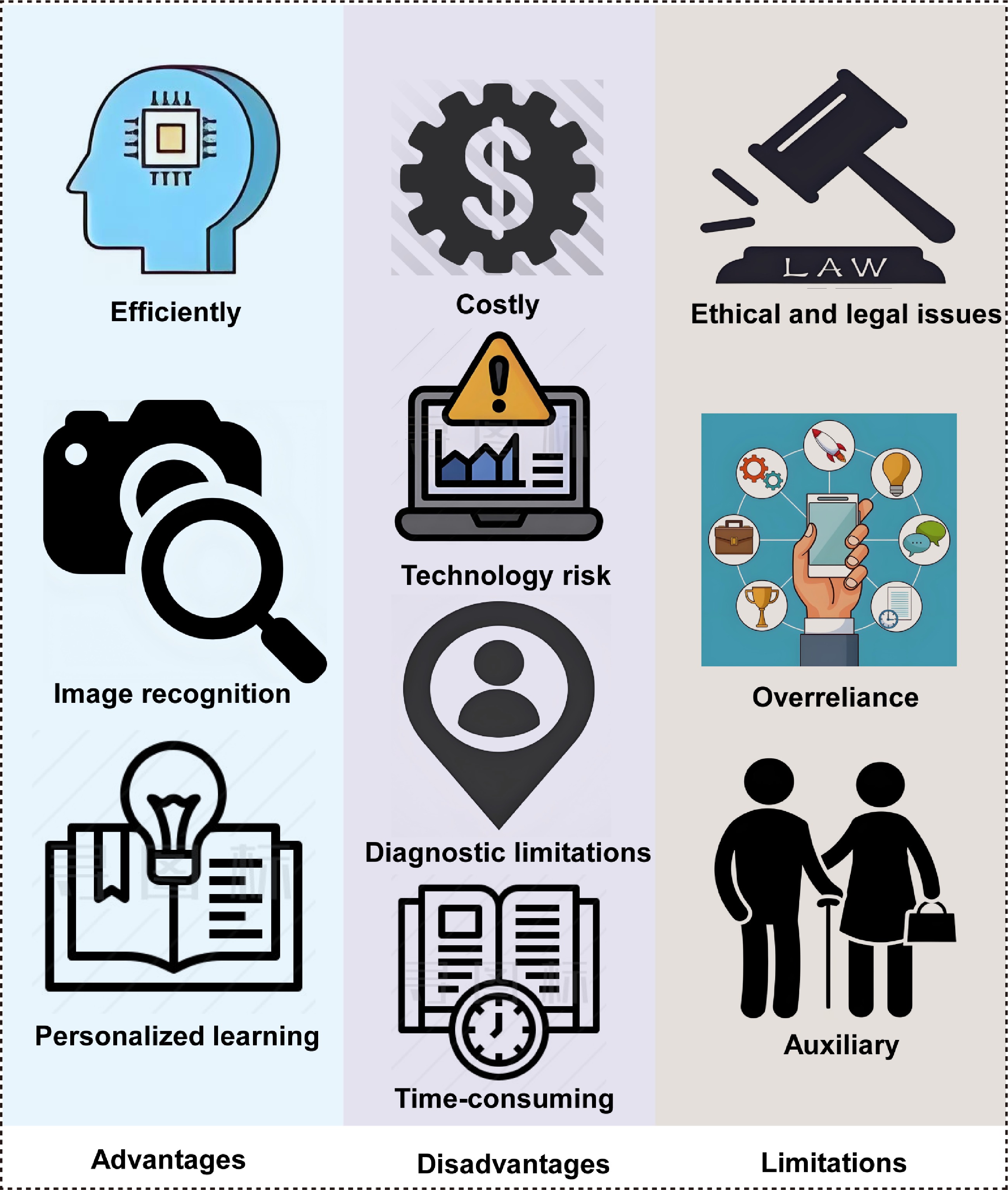

Figure 3 illustrates the key advantages, disadvantages, and current limitations of AI application in ophthalmic clinical and educational settings. AI technology significantly enhances the quality of ophthalmological education and skills by efficiently processing and analyzing vast datasets for disease screening. Krause et al.[53] used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to detect and classify DR. The model was trained on 1.5 million fundus photographs, and its performance even exceeded that of many senior ophthalmologists. AI technology has powerful capabilities in image recognition and analysis. AI is also widely used in the field of image recognition, which can automatically analyze OCT and fundus images[54]. AI not only improves the quality of image processing, but also provides students with tailored learning experiences. Moreover, intelligent teaching systems powered by machine learning algorithms create personalized learning paths and practical content tailored to the students' progress, enabling them to master complex ophthalmic knowledge and skills more effectively[55].

Figure 3.

The advantages, disadvantages, and limitations of AI in clinical and medical teaching applications in ophthalmology.

Disadvantages

-

Despite its advantages, AI technology in ophthalmic teaching also presents challenges. The high development and maintenance costs of advanced VR and AR devices and intelligent teaching systems can be prohibitive for resource-limited institutions[56]. AI systems may perform operations contrary to expectations as a result of programming errors or program defects, which may lead to wrong information output in the process of teaching or diagnosis, affecting the quality of learning and treatment[57]. AI-based glaucoma screening performs well in terms of sensitivity and specificity, but its diagnosis mainly depends on fundus photographs and other data, and there are learning errors and lag problems. AI models usually only identify glaucoma and normal people, and pay less attention to other concurrent diseases, such as high myopia, which may lead to false negative diagnoses[58]. Furthermore, the requirement for technical support and training can increase the teaching burden for both educators and students initially.

AI lacks the essential ophthalmic expertise and clinical judgment that experienced practitioners possess, which can lead to potential errors or misleading outcomes. Therefore, AI should be regarded as a supplementary resource rather than a substitute for expert guidance and practical training[59]. It may not completely replace human experience and judgment when dealing with complex and changeable clinical situations. Diagnosis in most studies is isolated and cannot reflect clinical practice[60]. Ethical and legal concerns, including patients' privacy and the transparency of AI decision-making, also require attention[61]. Finally, over-reliance on AI technology may lead to the students' lack of practical experience in the training process, affecting their performance in real clinical environments.

-

AI technologies play three distinct roles in medical education: Direct teaching, support teaching, and empowering the learner[9−15]. The integration of these AI capabilities into ophthalmological education drives transformative advancements in both teaching methodologies and learning outcomes. AI-driven tools such as tutoring systems[9], image interpretation models with feedback platforms[10], and personalized learning platforms[11] have significantly enhanced students' engagement and knowledge retention by providing adaptive feedback and tailored educational pathways. Notably, AI-assisted flipped classrooms[12], AI reading label systems[13], large language models (LLMs)[14], and automated grading systems[15] have optimized the efficiency of training, enabling learners to achieve higher diagnostic accuracy. In surgical training, AI's role in phase recognition[16, 62] and tool annotation[17,18] has revolutionized skill acquisition by offering real-time, data-driven feedback, reducing reliance on traditional apprenticeship models.

Implications for educational practice and future developments

-

These advances in AI not only improve diagnostic accuracy but also support the development of targeted treatment strategies, aligning with the objectives of personalized medicine in the diagnosis and management of ophthalmic diseases[40]. The integration of these advanced technologies has markedly improved the effectiveness of ophthalmological education and training, equipping future practitioners with the skills and confidence necessary for successful clinical practice. Traditional medical education mainly depends on descriptions of the disease in textbooks, but in the future, the use of AI technology to enable medical students to experience the effects of diseases may become an effective means to enhance medical teaching.

Future perspectives

-

Building upon the systematic review's findings, several critical gaps and limitations in the current application of AI in ophthalmological education must be addressed to guide feasible and validated future development. The evolution of ophthalmological education will likely be driven by AI-powered adaptive learning ecosystems, wherein intelligent tutoring systems could dynamically adjust microsurgical simulation content according to individual trainees' performance. Such systems should be rigorously validated through multi-institutional prospective trials to assess their efficacy in improving surgical outcomes—an area where current evidence remains limited. Furthermore, AI-generated synthetic cases have the potential to provide scalable and immersive diagnostic training across diverse ocular pathologies. However, efforts are needed to standardize the algorithmic generation process and ensure clinical fidelity, especially since many current AI models suffer from limited generalizability and insufficient external validation.

Significant breakthroughs are expected in mixed-reality surgical theaters, which integrate AR anatomy overlays with physical models. Nevertheless, issues surrounding the simulation's realism, the user interface design, and integration into existing surgical curricula require further co-design with educators and validation against real-world surgical performance metrics. Neural feedback systems, which are capable of refining techniques such as phacoemulsification through real-time motion analytics, also hold promise for transforming passive learning into precision skill acquisition. However, the implementation of such technologies must overcome the challenges related to data privacy, model interpretability, and ethical considerations, particularly when handling sensitive data on trainees' performance.

To scale this transformation responsibly, dedicated ophthalmic–AI research laboratories should prioritize the development of federated learning networks that enable multi-institutional collaboration while preserving data privacy. Concurrently, predictive analytic engines must be designed not only to identify competency gaps through analyses of surgical videos and decision patterns but also to address biases related to small sample sizes and unrepresentative training data—a common limitation identified in existing studies. Finally, for AI to truly democratize ophthalmic expertise, it will be essential to establish robust ethical frameworks and validation protocols that ensure equitable access, algorithmic fairness, and clinical relevance in AI-generated training environments.

Looking forward, three key research directions warrant particular attention. The first is the development of standardized assessment frameworks for AI-based educational interventions, including validated metrics for measuring skill acquisition and knowledge retention. The second relates to implementation science studies examining the integration of AI tools into existing educational curricula and clinical workflows. Third, researchers should undertake longitudinal studies evaluating the long-term impact of AI-enhanced training on clinical outcomes and the quality of patient care. Additionally, research should explore the optimal balance between AI-driven instruction and human mentorship, recognizing that the most effective educational models will likely involve synergistic human–AI collaboration rather than complete automation.

By anchoring these future directions in a response to current methodological limitations and validation gaps, the field can move toward more reproducible, generalizable, and ethically informed AI-enhanced educational tools. This systematic review has identified both the tremendous potential and significant challenges of AI in ophthalmological education, providing a foundation for targeted research efforts that can ultimately transform how we train the next generation of ophthalmologists.

-

This study provides a comprehensive review of how AI technology is applied in ophthalmology, focusing on its impact on disease screening, diagnosis, and teaching quality. Evidence indicates that AI, particularly through big data and deep learning algorithms, has significantly enhanced the diagnostic capabilities for ophthalmic diseases, resulting in improved treatment accuracy and safety. Additionally, integrating VR and AR technologies with intelligent teaching systems has enriched ophthalmological education, boosting students' engagement and practical skills. However, the widespread application of AI faces challenges such as data quality, privacy concerns, and ethical issues. Although AI improves learning efficiency and provides personalized feedback, it also requires significant resources and support. Excessive reliance on AI may lead to insufficient practical experience, highlighting the need for balance in educational design. Ultimately, AI technology is positioned to play a crucial role in advancing both medical practice and education in ophthalmology.

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82201195) and the Research Program of Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (grant number LGF21H120003).

-

Formal ethical approval was not required for this study. This is a systematic review based entirely on the analysis of previously published, peer-reviewed data. The data used for synthesis are publicly available and do not involve direct interaction with human participants or the collection of new individual-level data. All original studies included in this review received the necessary ethical approvals from their respective institutions before publication. This systematic review adheres to all relevant ethical guidelines for research synthesis.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Grzybowski A, Jin K; data collection: Yuan L, Dong X; analysis and interpretation of results: Yuan L, Liu L; draft manuscript preparation: Yuan L, Kang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Search strategies for each database.

- Supplementary Table S2 Summary table of bias risk and quality score for the included studies.

- Supplementary Table S3 Summary of Basic Characteristics and Key Findings of Included Studies.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan L, Kang D, Dong X, Liu L, Grzybowski A, et al. 2025. Artificial intelligence in clinical education in ophthalmology: a systematic review. Visual Neuroscience 42: e026 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0025

Artificial intelligence in clinical education in ophthalmology: a systematic review

- Received: 29 July 2025

- Revised: 28 September 2025

- Accepted: 20 October 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in ophthalmological clinical education has attracted widespread attention. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and searched three electronic databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science) for literature published between 1 January 2019 and 31 May 2025. In total, 38 studies were included to evaluate the role of AI in ophthalmological education. The results indicate that AI enhances the screening and diagnostic capabilities for ophthalmic diseases through big data and deep learning algorithms, while also diversifying educational approaches. Technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and intelligent tutoring systems create immersive learning environments that support surgical simulation, real-time feedback, and personalized learning pathways, significantly improving students' engagement and skill acquisition. Furthermore, AI-assisted image analysis and automated annotation tools optimize educational resources, shorten the duration of learning, and improve diagnostic accuracy. Nevertheless, challenges remain in the promotion of AI, including issues related to data quality, privacy protection, and ethical considerations.

-

Key words:

- Artificial intelligence /

- Ophthalmology /

- Clinical education /

- Research /

- Systematic review