-

Diabetic macular edema (DME), characterized by fluid accumulation in the macular region, is the leading cause of vision impairment in diabetic retinopathy (DR)[1]. The first-line treatment for DME is intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents. However, some patients do not respond well to initial anti-VEGF medications, resulting in persistent macular edema[2]. Over time, prolonged macular edema can lead to damage to photoreceptors and retinal atrophy, which would cause irreversible vision loss. Therefore, it is crucial to identify biomarkers that can predict the effectiveness of anti-VEGF treatment, allowing the recognition of patients at risk of developing refractory macular edema early on, thus leading to early combination with anti-inflammatory treatments or initial use of second-generation therapies, such as faricimab and 8 mg aflibercept. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a widely utilized imaging modality in medical retina, serving as a key tool for diagnosis and treatment evaluation in daily clinical practice. Among its imaging features, central subfoveal thickness (CST) is a primary anatomical measure. However, CST severity shows limited predictive value for treatment response and demonstrates a weak correlation with visual acuity and outcomes[3]. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has been increasingly applied to various imaging modalities to aid in predicting anti-VEGF treatment outcomes in DME. Traditional AI models primarily help to quantify image biomarkers, offering efficiency in processing vast amounts of data. AI's potential lies in its ability to integrate multimodal data (including clinical, demographic, and multimodal imaging) to provide a more comprehensive assessment of patient risk and response to treatment. This integration may enhance personalized treatment plans by allowing clinicians to better understand individual patient characteristics and tailor treatment strategies accordingly. The goal of this review is to summarize the current state of AI-driven prediction of anti-VEGF treatment outcome in DME and to identify the existing gaps in current algorithms and clinical applications for further research.

-

To assess the current landscape of AI models related to anti-VEGF treatment response in DME, a comprehensive literature review was conducted using Google Scholar and PubMed for the period from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2024. The search strategy incorporated a range of keywords, including 'diabetic macular edema', 'anti-vascular endothelial growth factor', 'prediction', 'treatment response', 'optical coherence tomography', 'optical coherence tomography angiography', 'fluorescein angiography', 'ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography', 'artificial intelligence', 'machine learning', and 'deep learning'. The selection was limited to articles published in English. Studies focused on pathologies other than DME were excluded from this study. Prediction of anti-VEGF treatment outcomes in DME includes anatomical and/or visual function responses, as well as treatment intervals. The narrative review includes all three of these outcomes, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of research articles on applicability of AI in DME treatment outcome prediction.

Year Authors Objective Imaging modality used Datasets AI model Outcome predicted Performance 2024 Baek et al.[4] Generate post-treatment OCT images, long-term anatomical prediction OCT + fundus 327 DME eyes from RCT KINGFISHER, one year follow-up GANs (CycleGAN, Pix2PixHD) Anatomical PPV, sensitivity, specificity, and kappa for residual fluid ranging from 0.500 to 0.889, 0.455 to 1.000, 0.357 to 0.857, and 0.537 to 0.929. PPV, sensitivity, specificity, and kappa for hard exudate were ranging from 0.500 to 1.000, 0.545 to 0.900, 0.600 to 1.000, and 0.642 to 0.894. 2022 Alryalat et al.[5] Predict anti-VEGF anatomical response (e.g., CST reduction) OCT 101 DME patients, three month follow-up U-Net, EfficientNet Anatomical The classification accuracy of classifying patients' images into good and poor responders was 75%. 2024 Meng et al.[6] Predict persistent DME after anti-VEGF via OCT-omics OCT 113 eyes from 82 patients with DME RF + Radiomics Anatomical The logistic classifier achieved a sensitivity of 0.904, specificity of 0.741, F1 score of 0.887, and AUC of 0.910. The SVM classifier showed a sensitivity of 0.923, specificity of 0.667, F1 score of 0.881, and AUC of 0.897. The BPNN classifier exhibited a sensitivity of 0.962, specificity of 0.926, F1 score of 0.962, and AUC of 0.982. OCT-omics scores were positively correlated with the rate of decline in CST after treatment (Pearson's R = 0.44). 2020 Rasti et al.[7] Predict anti-VEGF anatomical response (post-treatment retinal thickness) OCT 127 subjects treated for DME with three consecutive injections of anti-VEGF agents deep CNN Anatomical An average AUC of 0.866 in discriminating responsive from non-responsive patients, with an average precision, sensitivity, and specificity of 85.5%, 80.1%, and 85.0%. 2020 Cao et al.[8] Predict anti-VEGF anatomical response (good responders vs bad responder) OCT 712 DME eyes, treated with three monthly consecutive intravitreal conbercept injections OCT feature extractioin-CNN, responder prediction-RF/SVM Anatomical The sensitivity, specificity and AUC of responder prediction task was 0.900, 0.851, and 0.923. 2022 Xu et al.[9] Generate post-treatment OCT images, short-term anatomical prediction OCT 632 pairs of pre-therapeutic and post-therapeutic OCT images of patients with DME GAN(pix2pixHD) Anatomical The MAE of the CMT between the synthetic OCT images and the actual images was 24.51 ± 18.56 μm. 2022 Xie et al[10] Predict BCVA, CST reduction using OCT OCT n = 254, multi-nation cohort, six months SVM, RF Functional and anatomical The ACC and AUC of structural predictions of retinal pigment epithelial detachment were close to 1.000. The MAE and MSE of visual acuity predictions were nearly 0.3 to 0.4 logMAR. The ACC of treatment plan regarding continuous injection was approaching 70% 2020 Liu et al.[11] Predict CST and BCVA outcomes post three injections OCT Multi-center cohort, 363 OCT images and 7,587 clinical data records from 363 eyes Ensemble (RF + DL) Functional and anatomical For CFT prediction, MAE, RMSE, and R2 was 66.59, 93.73, and 0.71 in the training set, with an AUC of 0.90 for distinguishing the eyes with good anatomical response. For BCVA prediction, MAE, RMSE, and R2 was 0.19, 0.29, and 0.60, in the training set, with an AUC of 0.80 for distinguishing eyes with a good functional response. 2022 Zhang et al.[12] Predict VA one month after anti-VEGF therapy OCT (features extracted manually)

+ clinical data281 DME eyes linear regression + RF regression Functional For the prediction of VA variance at one month, the MAEs were 0.164–0.169 logMAR, and the MSEs were 0.056–0.059 logMAR. 2024 Wang et al.[13] Predict BCVA post-anti-VEGF therapy in telemedicine OCT + clinical/

demographic dataAPTOS 2021 Dataset, pre-treatment and post-treatment 2864 OCT images of 221 patients Semi-supervised CNN Functional Accuracy of VA prediction 38.18%, MAE 0.106, RMSE 0.141, R2 0.722 2022 Kar et al.[14] Predict anti-VEGF BCVA outcomes (responders vs non-responder) UWFA+OCT DME eyes from the PERMEATE study (29 eyes for UWFA study and 28 eyes for OCT study) ResNet50, ResNet101, Inception-v3 and DenseNet201 Functional The best performing DL model had a mean AUC of 0.507 ± 0.042 on UWFA images, and highest observed AUC of 0.503 for fluid-compartmentalized OCT images. 2021 Prasanna et al.[15] Predicting therapeutic durability of intravitreal aflibercept injection UWFA 13 eyes with DME and 14 eyes with RVO from the PERMEATE study Machine learning Functional The cross-validated AUC was 0.77 ± 0.14 using baseline leakage distribution features and 0.73 ± 0.10 for the UWFA baseline tortuosity measures. 2021 Gallardo et al.[16] Predict low and high treatment demand in patients with DME OCT+demographic data 333 eyes (285 patients) with RVO or DME RF Treatment interval Mean AUC of 0.76 and 0.78 for low and high demand in RVO and DME model. PPV, Positive Predictive Value; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; GAN, Generative Adversarial Network; CNN, Convolutional Neural Network; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machine; MSE, Mean Squared Error; MAE, Mean Absolute Error; RMSE, Root Mean Squared Error, DL: Deep Learning. -

OCT biomarkers such as CST, disorganization of retinal inner layers (DRIL), hyperreflective foci (HRF), ellipsoid zone (EZ) integrity, and subretinal Fluid (SRF) dominate prediction models, with established associations to anatomical outcomes[17]. Predicting visual function (visual acuity) is more complex and less reliable than CST changes due to weak correlations between structural and functional outcomes. DRIL is strongly associated with poor visual and anatomical outcomes[18−20]. The presence of HRF is linked to favorable anti-VEGF outcomes if reduced post-treatment. EZ integrity is correlated with visual improvement, with disruption of the EZ suggesting poorer treatment outcomes[21,22]. The presence of baseline SRF is associated with favorable visual outcomes in some cases, but this has been inconsistently validated across studies[23]. Moreover, chronic large cysts and central thickness reductions are core but insufficient as stand-alone predictors for DME.

-

As the manual interpretation of OCT B-scan images for DME can be time-consuming and error-prone, research focused on AI-assisted OCT biomarker identification has emerged. Midena et al. validated an AI algorithm for identifying and quantifying different major OCT biomarkers (IRF, SRF, ELM, EZ integrity, and HRF) in 303 DME eyes. The accuracy of the automatic quantification of IRF, SRF, ELM, and EZ ranged between 94.7% and 95.7%, while the accuracy of quality parameters ranged between 99.0% and 100.0%[24]. Tripathi et al. investigated an AI-driven system that can extract specific biomarkers such as DRIL, HRF, and cystoids from OCT images, and DME severity can be determined using these automatically detected features[25]. AI algorithm is promising in providing a reliable and reproducible assessment of the most important OCT biomarkers in DME, allowing clinicians to routinely identify and quantify these parameters[5].

Cao et al. used auto-segmented HRD, SRF, and IRF from baseline OCT images and a self-explainable machine learning (ML) model to predict the initial anti-VEGF therapeutic responsiveness of DME[8]. In a post hoc analysis of DRCR Protocol-T, IRF and SRF volumes were automatically quantified using deep learning during anti-VEGF treatment, and their changes were correlated with visual acuity outcomes[23]. Gallardo et al. adopted morphological features automatically extracted from the OCT volumes at baseline and after two consecutive visits, as well as patient demographic information, to train random forest models to predict the probability of the long-term treatment demand of DME and retinal vein occlusion (RVO)[16]. Their ML model achieved a mean AUC of 0.76 and 0.78 for low and high demand for RVO and DME. Michl et al. used deep learning to analyze macular fluid volumes (localisation and quantification of IRF/SRF) and treatment response in anti-VEGF therapy across multiple retinal conditions, and they found a specific anatomical response of IRF/SRF to anti-VEGF therapy in DME[26]. Therefore, automated quantification of IRF and SRF provides a more comprehensive observation for monitoring DME treatment efficacy, which is beneficial for studies on the predictive effectiveness of DME treatment.

-

In addition to the established OCT biomarkers mentioned above, textural-based OCT radiomics features represent another area of exploration. Radiomics refers to the extraction and analysis of extensive advanced quantitative imaging features from medical images using computer vision and image processing techniques. Numerous works in oncology have used texture-based radiomics features from different tumor subcompartments to predict treatment response across a range of cancer types. Ehlers et al. extracted radiomic features from each of the fluid compartments (IRF and SRF) and various retinal tissue compartments on SD-OCT scans obtained from the PERMEATE clinical trial[14,15]. In this trial, eyes were treated with 2 mg intravitreal aflibercept injection q4 weeks for the first six months, and then administered q8 weeks at months eight, ten, and 12. 'Non-rebounders' were eyes that maintained/improved BCVA following the first 8-week challenge, while 'rebounders' were eyes that exhibited at least one letter worsening in BCVA following the first 8-week challenge.

Top-performing features selected from the consensus of different feature selection methods were evaluated in conjunction with four different ML classifiers to distinguish eyes tolerating extended interval dosing and those requiring more frequent dosing. Eventually, they found that the combination of fluid and retinal tissue features yielded a cross-validated AUC of 0.78 ± 0.08 in distinguishing rebounders from non-rebounders, and the texture-based radiomics features pertaining to IRF subcompartment were most discriminating between rebounders and non-rebounders to anti-VEGF therapy. Meng et al. used radiomics features derived from the segmented OCT images using the Pyradiomics module within the 3D Slicer software, as well as clinical data, to develop and evaluate an OCT-omics prediction model for assessing anti-VEGF treatment response in patients with DME[6]. The OCT-omics scores were significantly higher in the non-persistent DME group than in the persistent DME group and were also positively correlated with the rate of decline in CST after treatment. These findings highlighted the predictive power of the pretreatment OCT-omics in assessing the prognosis of DME.

-

Deep learning techniques are increasingly being used in OCT scans to predict treatment responses in DME. Rasti et al. designed and evaluated a deep convolutional neural network using pre-treatment OCT scans as input and differential retinal thickness as output[7]. The algorithm achieved an average AUC of 0.866 in discriminating responsive from non-responsive patients, with an average precision, sensitivity, and specificity of 85.5%, 80.1%, and 85.0%, respectively. This study demonstrated the effectiveness of a deep learning-based automated system in predicting anti-VEGF treatment response directly using pretreatment OCT scans, potentially streamlining patient management.

-

GANs are a type of deep learning model made up of two neural networks—a generator and a discriminator—that compete in a minimax game. The generator creates synthetic data (e.g., images), while the discriminator tries to distinguish real data from generated data. GANs support tasks such as data augmentation, super-resolution, segmentation, and disease progression prediction in numerous medical specializations. In DME cases, GANs have been effectively applied to OCT imaging to predict both short-term and long-term outcomes of anti-VEGF therapy. Xu et al. used a pix2pixHD GAN to predict post-therapy OCT changes, particularly edema resolution, based on pre-treatment OCT images[9]. Metrics like mean absolute error (MAE) of central macular thickness (CMT) demonstrated precise alignment with real outcomes. Alryalat et al. applied multiple GAN architectures (CycleGAN, UNIT, Pix2PixHD, RegGAN) for predicting residual fluid and hard exudates at 52 weeks using multi-time-point OCT datasets[4]. The approach improved predictive accuracy by incorporating temporal OCT data (weeks 4/12, augmenting baseline) and provided clinically useful outputs. The application of GANs to OCT imaging for predicting anti-VEGF outcomes in DME is promising, but challenges in dataset scalability and model interpretability remain to be addressed.

-

AI frameworks integrating OCT images/biomarkers with systemic variables helped to improve the prediction of anti-VEGF treatment outcomes. Liu et al. used deep learning on OCT images and classical ML on OCT-derived features/clinical variables to predict post-treatment central foveal thickness (CFT) and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA)[11]. A machine learning system was used to predict anti-VEGF outcomes using OCT/clinical data. For CFT prediction, they achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.90 for distinguishing eyes with a good anatomical response. Wang et al. proposed a multimodal algorithm based on a semi-supervised learning framework, combining OCT images and clinical data to automatically predict the VA values of DME patients after anti-VEGF treatment. They achieved accuracy scores of 65.2% for CST prediction and 33.04% for VA prediction[13].

-

While OCT is widely used to evaluate structural changes during treatment, FA/UWFA provides critical information on retinal perfusion and vascular integrity. FA visualizes retinal vasculature in detail, capturing leakage, capillary dropout, and microaneurysms. These vascular abnormalities are key determinants of disease severity and response to anti-VEGF therapy. Leakage observed on FA has been widely studied as a predictor of anti-VEGF response in DME. Several studies reported that leakage patterns—classified as focal (microaneurysm-associated) vs diffuse (wide, non-microaneurysm-associated)—are central predictive markers. Microaneurysm (MA)-associated focal leakage has been consistently linked to better anti-VEGF response, as it primarily reflects VEGF-driven vascular activity[27,28]. Residual or persistent leaking MAs, however, are correlated with incomplete treatment response or residual edema, especially in refractory cases[29]. Diffuse leakage is associated with suboptimal treatment outcomes, likely reflecting chronic vascular or inflammatory damage that does not fully respond to VEGF inhibition alone[30]. Quantitative analyses of leakage distribution have shown that diffuse leakage requires more frequent injections and longer treatment timelines to achieve partial resolution[31].

Macular ischemia (MI), defined as an enlargement of the FAZ and perifoveal capillary loss, is another important clinical feature in DR. Zheng et al. developed software for automated measurements of the FAZ on FA photos, which demonstrated good reproducibility and a linear correlation with manual grading by retina specialists[32]. Ischemia markers appear to limit visual recovery and anatomical improvements with anti-VEGF therapy. Studies consistently show that enlarged FAZ or perifoveal capillary loss strongly predicts poor outcomes following anti-VEGF therapy[30]. Macular ischemia results in irreversible damage to the retinal structure and reduced oxygen supply, limiting the potential for VEGF suppression to restore retinal function.

UWFA expands imaging coverage to the peripheral retina, allowing for panretinal assessment of nonperfusion and vascular abnormalities. Semi-automated or fully automated tools focus on measuring metrics such as leakage area, leakage intensity, retinal vascular bed area (RVBA), and nonperfusion indices to standardize predictions[33]. Quantitative leakage analysis via segmentation algorithms has demonstrated significant correlations between leakage extent and treatment responses. Baseline and treatment-induced changes in leakage have also been quantitatively assessed to evaluate therapy responsiveness. RVBA, a novel metric from UWFA, correlated with macular volume improvement and baseline nonperfusion index[34]. However, peripheral ischemia and global nonperfusion assessed via UWFA do not strongly correlate with anti-VEGF response in all studies, reflecting variability in peripheral leakage relevance[34,35].

Recent studies have employed AI and deep learning algorithms to analyze fluorescein angiograms for correlations with anti-VEGF outcomes. ML algorithms have been applied to large UWFA datasets to segment features like leakage and vascular tortuosity, demonstrating potential for predicting treatment interval lengths in DME[36]. Dong et al. applied deep learning to UWFA images, classifying patients based on their ability to tolerate extended anti-VEGF dosing intervals[36]. Their findings emphasized the role of peripheral non-perfusion zones and leakage area as critical biomarkers for stratifying treatment responders vs non-responders. Textural-based radiomics features were also explored in UWFA to predict therapeutic response[25,26]. Firstly, UWFA scans were evaluated using an automated vessel and leakage segmentation platform, and a panretinal vascular skeletonised map and leakage localisation masks were generated. The masks were then exported for further computational analysis, which involved quantitative measures of leakage shape/spatial distribution and quantitative measures of vessel tortuosity. Eventually, two new computer-extracted radiomics-based imaging biomarkers derived from UWFA for the prediction of extended interval tolerance to intravitreal anti-VEGF aflibercept treatment for DME[15]. However, further efforts are needed to standardize quantitative metrics in UWFA, and deep learning models for FA/UWFA should be validated against clinical outcomes using large, multi-site datasets.

-

OCTA is a noninvasive imaging technique that can quickly and noninvasively capture high-resolution images of all the vascular layers of the retina and choroid. In contrast to FA, OCTA images are not obscured by hyperfluorescence from dye leakage, and therefore, they can generate high contrast, well-defined images of the microvasculature. OCTA-based biomarkers, particularly baseline vessel density (VD) and foveal avascular zone (FAZ) metrics, have shown strong predictive value for anti-VEGF treatment response in DME[37,38]. Higher baseline VD, especially in the superficial capillary plexus (SCP), is consistently associated with better visual and anatomical outcomes[38,39]. The foveal avascular zone (FAZ) is another prominent feature in OCTA images of the macula. The size, shape, and fragmentation status of the FAZ serve as potential biomarkers. Smaller FAZ area and more regular FAZ contours predict favorable treatment responses[39,40]. In addition, improved perfusion density (PD) in SCP is linked to responder status, with higher SCP PD noted in responders[38].

Microaneurysms detected by OCTA might serve as a biomarker for a short-term clinical response to anti-VEGF treatment, although further validation is required, as MAs were manually selected by the examiner[40]. Intercapillary area (ICA), assessed by customised MATLAB software, was a significant predictor of macular thickness outcomes after intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy in initially treatment-naïve eyes with DME[41]. A lower vessel diameter index in the deep capillary plexus (DCP) has also been observed in responders compared to non-responders[38].

Diabetic macular ischemia (DMI) involves capillary nonperfusion and reduced blood flow in the macula, leading to ischemic damage. Some studies suggested that severe DMI may be associated with a limited visual response to anti-VEGF therapy[42]. A multitask deep-learning system has been proposed and shown promise in facilitating simplified, automated DMI assessment from OCTA images, which could enhance screening and monitoring for diabetic patients at high risk of visual loss. The study also emphasized DCP ischemia as a greater contributor to visual decline.

Widefield OCTA (WF-OCTA) captures the retinal and choroidal microvasculature over a larger field of view than standard OCTA, enabling detection of peripheral ischemic changes, such as nonperfused areas (NPAs), in addition to macular features. Several studies have focused on the application of AI to automate the analysis of WF-OCTA features. For example, Guo et al. developed deep learning models such as MEDnet and parallel U-Nets to detect and segment NPAs in WF-OCTA and widefield montaged scans[43]. Their work demonstrated high accuracy in handling imaging artifacts and isolating NPAs across retinal microvascular plexuses. Similarly, semi-automated quantification methods, such as those proposed by Alibhai et al. and Garg et al.[44,45], provided robust tools to correlate NPA burden with DR progression. If AI-based analysis of WF-OCTA-derived metrics, such as NPAs, can be utilized to predict anti-VEGF efficacy, it would significantly improve our understanding of treatment responses in DME.

The most noted challenges in OCTA-based AI models involved motion artifacts, noise, and projection errors disproportionately affecting ischemic zones[46]. Recently, an AI-based super-resolution framework has been developed to enhance OCTA images with learnable texture generation, facilitating improved vessel segmentation and ischemia assessment in DME[47]. Novel algorithms enhancing OCTA image quality provide potential foundational data for future AI-driven models that integrate ischemia and other macular parameters to predict anti-VEGF response in DME.

Unlike OCT and FA, there is a noticeable gap in studies that integrate OCTA features with AI models for predicting anti-VEGF response in DME. Future research directions should focus on developing fully automated OCTA extraction algorithms to enable large-scale biomarker-based predictions and combining OCTA-derived ischemia metrics with emerging AI technologies to improve personalized treatment predictions in DME. Furthermore, integrating super-resolution techniques into AI pipelines will be crucial to ensure the accuracy and reliability of ischemia biomarkers extracted from OCTA[47].

-

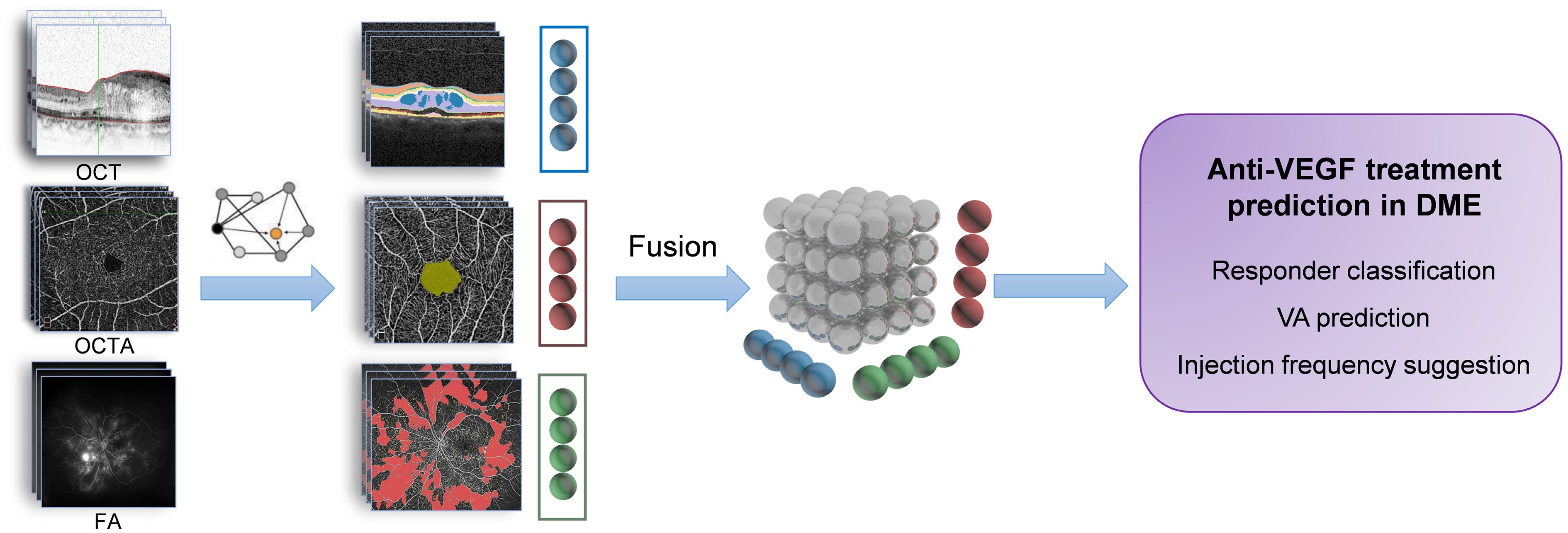

OCT provides high-resolution cross-sectional structural imaging of the retina, while OCTA adds vascular insights, capturing blood flow and macular perfusion, and FA offers dynamic information about vascular leakage and ischemia. By integrating these modalities, multimodal imaging provides a comprehensive view of the retina, combining structural, functional, and vascular characteristics to better understand disease complexity and predict treatment outcomes in DME.

Single-modality approaches, such as OCT-derived biomarkers (e.g., fluid compartments and DRIL) or OCTA-derived biomarkers (e.g., vessel density and flow voids), provide valuable insights but fail to capture the full spectrum of disease activity. For instance, OCT-derived markers miss critical vascular and ischemic factors influencing anti-VEGF efficacy, while OCTA biomarkers alone may not fully predict fluid dynamics or functional outcomes like visual acuity improvement. Multimodal imaging addresses these gaps by combining vascular and leakage data (OCTA, FA) with structural findings (OCT), enabling the identification of patterns that distinguish good responders, suboptimal responders, and non-responders[48].

Studies have demonstrated the utility of multimodal approaches. For instance, co-localizing FA leakage with OCT-detected cystoid spaces improves diagnostic specificity for VEGF-driven mechanisms in DME[30]. Kar et al.[49] carried out a radiogenomic assessment and revealed strong correlations between VEGF expression and seven UWFA leakage morphologic features, one vascular tortuosity-based UWFA feature, and two OCT-derived IRF texture features, further validating the role of multimodal imaging in treatment response prediction.

Multimodal imaging fusion models encompass feature-level fusion, image-level fusion, decision-level fusion, and, more recently, transformer-based architectures and attention mechanisms. Future clinical applications of multimodal fusion in DME are expected to include responder classification, visual acuity prediction, and injection frequency optimization (Fig. 1). However, data heterogeneity and the limited availability of multimodal datasets continue to pose significant challenges for integrating multimodal imaging in DME, restricting the progress of AI research. To address these issues, greater emphasis must be placed on standardizing datasets and promoting data sharing across institutions. Additionally, incorporating longitudinal imaging data to track disease progression over successive anti-VEGF treatments is essential for enabling more dynamic and precise outcome predictions.

-

AI has shown great potential in predicting anti-VEGF treatment outcomes for DME (Table 1), leveraging advanced imaging modalities like OCT, OCTA, and FA. By analyzing biomarkers and integrating multimodal data, AI offers insights into treatment response, visual acuity improvement, and injection optimization. However, critical evaluation reveals significant gaps in the current AI models and their clinical applicability. To translate these models effectively into real-world practice, several challenges must be addressed. First, data heterogeneity is a major concern. Validation of AI models using larger and more diverse patient datasets is essential to ensure their generalizability across different populations. Second, the standardization of OCT protocols is vital to minimize variability introduced by different imaging devices and clinical settings. Additionally, incorporating these models into clinical trials will be crucial for demonstrating their efficacy and practical value in various medical environments. Furthermore, addressing ethical considerations—such as patient data privacy and the transparency of AI decision-making processes—is imperative to build clinician and patient confidence in these technologies. By systematically addressing these challenges, the clinical utility of AI models in predicting anti-VEGF treatment outcomes can be enhanced.

The future of AI in DME treatment prediction lies in personalized treatment plans, integration of multimodal imaging, and real-time decision support. Advanced models will utilize biomarkers, radiomics, and longitudinal data to enhance predictive accuracy. Collaborative efforts to standardize datasets and ensure robust model development are crucial for global adoption. The use of large language models (LLMs) and foundation models in DME treatment prediction holds significant promise for advancing eyecare outcomes. LLMs can effectively process and analyze a variety of data types, including clinical notes, structured patient data, and various modalities of retinal imaging, thereby improving the accuracy of treatment predictions. By utilizing patient-specific information, LLMs can assist in tailoring treatment plans that consider individual characteristics, medical histories, and current fundus conditions, enabling ophthalmologists to make informed decisions based on up-to-date research and established guidelines. Foundation models like RETFound[50] can enhance the development of AI models by efficiently extracting relevant features from complex datasets and integrating various data sources for improved accuracy. They also enable transfer learning and predictive analytics, ultimately leading to more robust and generalizable applications in healthcare. Embracing AI-driven precision medicine is essential for transforming the management of DME. This approach paves the way for tailored, efficient, and effective treatment strategies that ultimately enhance patient outcomes.

This study was supported by project BJ-LM2021013J from Bethune Lumitin Mid-Young Ophthalmic Research Fund (KH0120220277), and project MOH-000622-01 from Health Services Research Grant (HSRG).

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing – original draft preparation: Cao D; writing – review and editing: Yao J, Ting D; conception: Tan G; graphical design: Cao D. All authors reviewed the contents and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data presented in this study are included in this published article and related references.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cao D, Yao J, Ting D, Tan G. 2025. Artificial intelligence in predicting anti-VEGF treatment response in diabetic macular edema: current progress and future directions. Visual Neuroscience 42: e027 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0027

Artificial intelligence in predicting anti-VEGF treatment response in diabetic macular edema: current progress and future directions

- Received: 04 February 2025

- Revised: 17 February 2025

- Accepted: 24 February 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Diabetic macular edema (DME), a leading cause of vision impairment in diabetes, is primarily treated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections. However, variable treatment response rates often lead to persistent edema and irreversible vision loss. Accurate prediction of treatment response is therefore critical for optimizing treatment strategies and preserving visual function. This review examines the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to predict anti-VEGF treatment outcomes in DME. While optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging has shown significant progress, the potential of optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) and fluorescein angiography (FA) remains under-exploited. AI holds considerable promise for enhancing predictive accuracy. Future research should focus on multimodal imaging approaches integrating structural, ischemic, and vascular information to develop more accurate and reliable predictive models for personalized DME treatment.