-

As sessile organisms, plants are typically exposed to a complex natural environment in which a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses can lead to partial or complete yield loss. Plant growth, development, and stress resistance are strictly coordinated by intercellular communication and subsequent intracellular signaling, processes in which plant hormones play important roles. Small secreted peptides (SSPs), defined as peptides shorter than 250 amino acids (aa), have recently emerged as an important class of hormones and key signaling molecules that help to coordinate cell–cell communication[1,2]. Since the discovery of systemin, a plant signaling peptide involved in the systemic wounding response, in the last century[3], numerous SSPs with crucial roles in plant growth and stress responses have been identified in a variety of plant species.

CLAVATA3 (CLV3)/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (ESR)-RELATED (CLE)-family peptides are peptide hormones initially identified for their critical role in maintaining plant meristems[4]. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that CLE peptides are produced across numerous tissues, organs, and developmental contexts, from root tips to flowers[5], and are actively transported out of plant cells[6,7]. These peptides mediate a variety of physiological processes, including the regulation of cell-division rates and orientations within meristems, leaf senescence, stomatal patterning, microspore–tapetum interactions, pollen development, pollen–stigma communication[8], fruit development, and nodule formation[4,9,10]. Endogenous CLEs exert their influence at pico- and nano-molar concentrations over both long and short distances[2,11−14]. Numerous CLE-encoding genes with distinct expression patterns and diverse functions are present in plant genomes of various angiosperms including Arabidopsis thaliana (32 CLE genes), Zea mays L. (51), and Oryza sativa L. (41)[15].

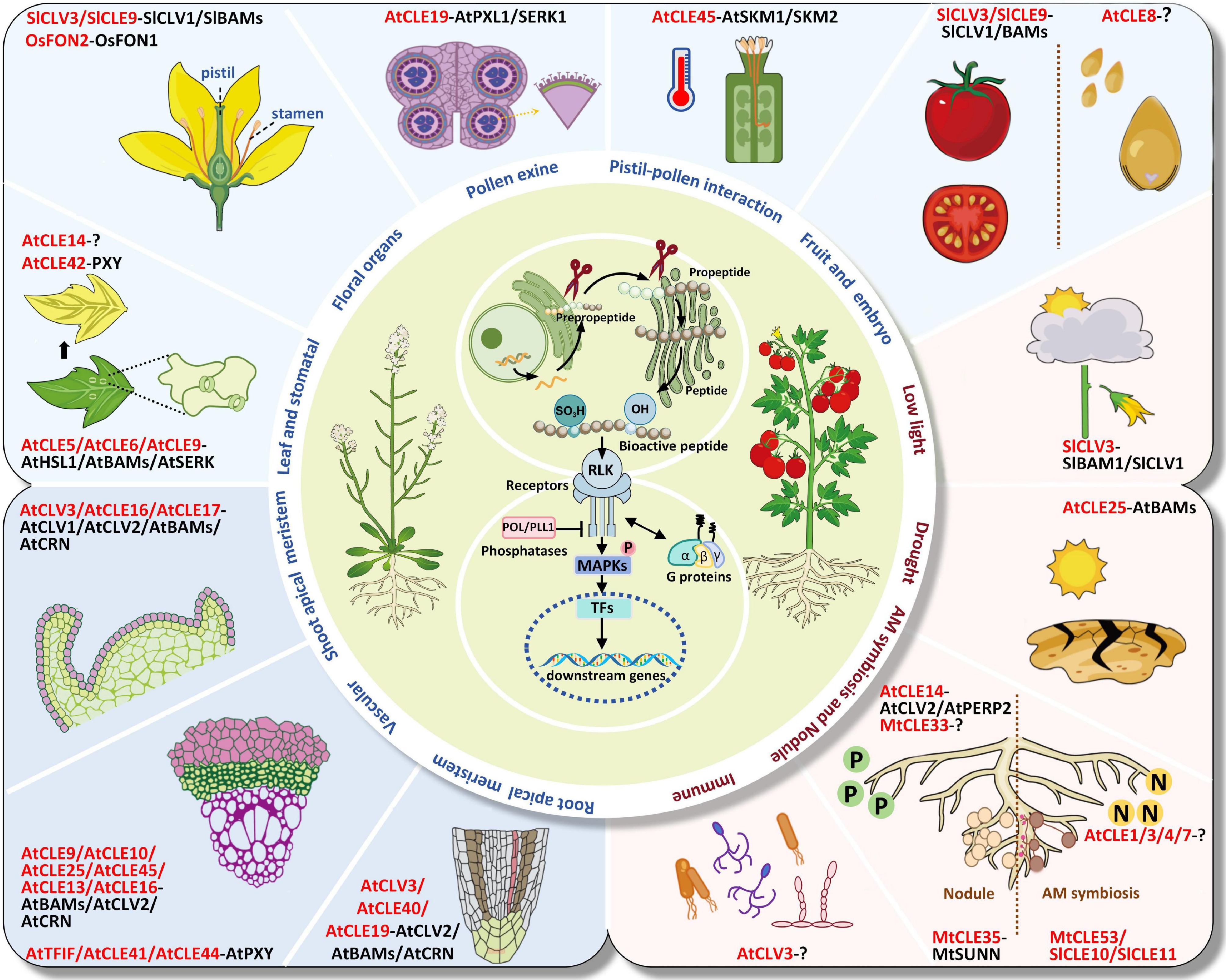

In this review, we describe the proteolytic processing of precursor proteins to release CLE peptides, the molecular structures of mature CLE ligands, and the signaling modules in which they participate. We also review recent findings on the functions of CLE peptides in growth, development, and stress responses across multiple plant species and their underlying molecular regulatory mechanisms (Fig. 1). Finally, we highlight critical areas for future research.

Figure 1.

Biological functions of CLE peptide hormones and related receptors in regulating plant growth, development, abiotic stress, AM symbiosis, nodulation, and plant-pathogen interactions. CLE ligands are in red and receptors are in black. The name and abbreviation of plant species used are Arabidopsis thaliana (At); Solanum lycopersicum (Sl); Oriza sativa (Os); Medicago truncatula (Mt).

-

CLE precursor peptides are approximately 100 amino acids (aa) in length. These propeptides consist of an N-terminal secretion signal (approximately 20 aa), a C-terminal CLE domain (12–13 aa), and a variable middle domain (approximately 80 aa)[16]. Generally, a CLE propeptide gives rise to a single CLE peptide of 12–13 aa through serine peptidase and carboxypeptidase cleavage at sites flanking its single CLE domain[17−19]. However, several CLE propeptides with multiple CLE domains have been reported in O. sativa and S. moellendorffii, and these can give rise to multiple different CLE peptides depending on proteolytic cleavage patterns. The mechanism of CLE proteolytic cleavage has been characterized in Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula and is thought to be conserved across land plants[20,21]. CLE propeptides are categorized into two distinct types—A-type and B-type—based on sequence similarities and the specialized functions of their conserved C-terminal amino acids. A-type CLE peptides, such as CLV3, primarily inhibit activity in both shoot and root apical meristems, simultaneously promoting cellular differentiation. In contrast, B-type peptides, which include CLE41 to CLE44, suppress the differentiation of tracheary elements while promoting division in procambial cells. Beyond their roles in modulating cell proliferation and differentiation, these classes of CLE peptides also influence the orientation of cell division planes[9,14].

Arabinosylation of hydroxyproline (Hyp) is an important post-translational modification found on secreted plant peptide signals and is critical for their function[22,23]. Several A-class CLEs are known to undergo arabinosylation after cleavage; mature CLE peptides are C-terminally proteolytically processed from their precursors, generating 12- or 13-residue glycopeptides modified with L-arabinose residues on Hyp7[24]. The arabinosylated form of CLV3 in Arabidopsis terminates the shoot apical meristem (SAM) more effectively at lower concentrations than its non-arabinosylated form[22], and the limitation of SAM size in tomato by CLV3 requires its complete arabinosylation[25]. The control of nodule number in Pisum sativum and Lotus japonicus by soybean CLE (GmRIC1) and CLE-RS2 also depends on arabinosylation[26]. However, the presence and roles of arabinosylated CLE peptides in other plant species and other CLE clades remain to be investigated. It would be particularly useful to investigate whether each CLE ligand has only one modification type and how different sugar modifications affect downstream signaling.

-

CLE peptides are recognized by transmembrane leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs), which contain an extracellular ligand-binding LRR domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular kinase domain and interact with a variety of co-receptors to facilitate intracellular signal transduction[27] (Fig. 1). To date, all studies have reported that CLE peptide signals from different clades are recognized and transduced by LRR-RLKs[28]. The first identified CLE peptide–receptor pair was CLAVATA3 (CLV3) and the LRR-RLK CLAVATA1 (CLV1), which control stem-cell fate in Arabidopsis[29−32].

Given the numerous variants of both CLE peptides and their candidate receptors, confirming specific ligand-receptor relationships remains challenging. Nevertheless, several CLE receptors, notably SAM regulators such as CLV1, CLV2, and CORYNE, have undergone detailed functional characterization[33−35].

The identification of individual CLE-receptor pairs and their developmental functions will be discussed below. Previous research has explored the mechanisms through which intracellular signals from CLE peptides are transmitted. It is proposed that phosphatases, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and heterotrimeric G proteins participate in this signaling pathway. Mutations in the genes encoding the phosphatases POLTERGEIST (POL) and POL-LIKE 1 (PLL1) have been found to suppress the SAM phenotype in CLV3, CLV1, and CLV2 mutants, suggesting that these phosphatases act downstream of CLE signals and their receptors[36,37]. Additionally, CLV3 signaling has been shown to activate the MAP kinase cascade in Arabidopsis, with MAP6 expression upregulated in the clv1 mutant compared to the wild type, indicating its role in downstream signaling. Importantly, negative regulation of MAP kinase activity can rescue the clv1 mutant phenotype, highlighting the critical role of MAP kinases in maintaining SAM homeostasis[2,3]. In maize, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) signal downstream of CLE peptides in the SAM through a subset of receptors. Specifically, GPCR compact plant2 (CT2) transmits signals from the maize homolog of CLV2, fascinated ear 2 (FEA2), which conveys downstream signals from ZmCLE7[38]. Despite these advancements, the intracellular signaling mechanisms activated by CLE receptor recognition remain poorly understood, highlighting the need for further research. A prevailing hypothesis posits that common signaling components trigger specific responses through diverse transcription factors in different cell types. Understanding how multiple ligand-receptor pathways in single cells maintain signaling specificity is essential. For instance, research comparing developmental and immune signaling in Arabidopsis root endodermal cells shows they share a common MAPK module but have distinct functions and outputs. These studies suggest that differential phosphorylation within the MAPK cascade regulates a key transcription factor, demonstrating the importance of combinatorial activation patterns[39,40].

Identification of specific CLE–RLK interactions and characterization of their genetic and molecular bases will help to clarify their mechanisms of action. How shared receptors and kinases accurately transmit diverse CLE signals within the same cell type remains to be determined, and answering this question will shed light on how plants integrate and process complex signals.

-

Plant vegetative development involves tightly regulated processes of cell division, growth, and differentiation. Stem cells, present in the shoot apical meristem (SAM), root apical meristem (RAM), and procambium/vascular cambium, are crucial for producing new tissues and organs during post-embryonic growth and development. CLE peptides help to regulate these processes through their roles in intercellular signaling within organs and among cell types.

-

One of the first identified CLEs, the CLV3 peptide, is a key factor for SAM size regulation in angiosperms[4]. CLV3 promotes stem-cell differentiation in the central zone and functions in a feedback loop with its receptors, including CLV1, to regulate the expression of its major downstream target, the transcription factor WUSCHEL (WUS)[11,41−43]. WUSCHEL (WUS) controls the proliferative activity of overlying stem cells and antagonizes the function of CLAVATA3 (CLV3). This CLV–WUS pathway forms a negative feedback loop that maintains constant meristem size, with WUS expression restricted by CLV3 activity[44]. Additional CLE receptors also regulate meristem size in A. thaliana[45]; these include BARELY ANY MERISTEM1, 2, and 3 (BAM1–3), CLAVATA2 (CLV2)[34], SUPPRESSOR OF LLP2/CORYNE (SOL2/CRN)[35,46], and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE2 /TOAD2 (RPK2/TOAD2). CLV1 is thought to play a dominant role in restricting stem-cell proliferation, with BAM1–3 acting as redundant safeguards[47]. Another recent report showed that a mechanism involving CLE16 and CLE17 partially compensates for CLV3 activity to restrict stem-cell proliferation in the SAM[48].

-

CLE peptides also control cell proliferation in the RAM. AtCLE40, expressed in stele cells of the root differentiation zone, mediates cell proliferation in the proximal root meristem, extending from the quiescent center toward the shoot[49,50]. Application of chemically synthesized 14-aa CLE40, CLV3, and CLE19 peptides reduces the length of the proximal root meristem and suppresses root growth in Arabidopsis seedlings through a CLV2- and CRN-dependent pathway[49,51−53]. Exogenous application of two other type-A peptides, CLE17 and CLE19, also limited root growth via the RPK2 receptor kinase[54]. By contrast, external application of type-B CLE peptides has been shown to induce both proliferation and elongation of the proximal root meristem in Arabidopsis and poplar. Likewise, tracheary element differentiation inhibitory factors (TDIFs), as type-B CLEs, also enhance proximal root meristem growth by regulating PIN-FORMED (PIN)-mediated polar auxin transport[55,56]. Exogenous applications of A-type or B-type CLE peptides thus broadly modulate cell differentiation and proliferation across the entire RAM; however, the specific cellular mechanisms underlying these regulatory processes remain poorly understood.

-

Stem-cell proliferation is necessary for the vascular development and mechanical integrity of plant stems. TDIF peptides regulate vascular development through their roles in cell communication[57,58]. Synthesized in the phloem, TDIFs are translocated to the cambium and perceived by the receptor PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM/TDIF RECEPTOR (PXY/TDR)[59,60]. Both exogenous treatment with synthetic TDIF peptides and overexpression of CLE41 and CLE44 genes can promote procambial cell proliferation and repress xylem cell differentiation[9,53]. WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) transcription factors WOX4 and WOX14 are downstream targets of the TDIF–PXY signaling module and redundantly regulate vascular cell division. The TDIF–PXY–WOX pathway is crucial for maintaining vascular meristem patterning during secondary growth[61]. In addition to CLE41/CLE44, CLE9/10, CLE25, and CLE45 are also crucial for vascular development. CLE9/10 are expressed in xylem precursor cells of the root vasculature and inhibit periclinal cell division by binding to BAM receptor kinases, including BAM1–3. Physical interactions between CLE9/10 and BAM1 have been confirmed during root xylem development, revealing BAMs as CLE9 receptors. The CLE9–BAM signaling pathway limits the proliferation of xylem precursor cells, preventing excessive differentiation of metaxylem cell files[62].

CLE-mediated consumption of the proximal root meristem is closely related to protophloem development. The CLE45 peptide specifically inhibits protophloem differentiation in the RAM and binds directly to the receptor BAM3. CLV2 forms a heterodimer with CRN to stabilize and enhance the accumulation of BAM3 protein, enabling full perception of the CLE45 signal[63]. Like CLE45, CLE25 also regulates phloem initiation and affects the development of the proximal root meristem. The class-II LRR-RLK protein, CLE-RESISTANT RECEPTOR KINASE (CLERK), is also essential for the perception of CLE45 and CLE25 peptides during early protophloem development, operating in a genetically distinct pathway from BAM3 and CLV2/CRN[64]. In addition, recent studies have shown that BAM1 and BAM2 redundantly promote the formative ground-tissue divisions stimulated by CLE13/16 in the root stem-cell niche, a process in which CLV1 and BAM3 appear to have minor roles[47].

-

CLE signals play a role in the regulation of leaf development. In Arabidopsis, CLE5, and CLE6 are expressed at the base of the developing leaf, and their knockout mutants show widened petioles. WOX transcription factors, particularly WOX1 and PRESSED FLOWER (PRS), regulate the expression of CLE5 and CLE6 during this process[57]. Overexpression of the CLE gene FCP1 in rice eliminates the boundary between leaf and sheath by inhibiting vascular-bundle differentiation[65]. Interestingly, exogenous application of CLE reduces leaf size in moss, whereas the leaves of CLE mutants are larger, with increased tip formation[14]. Although the regulation of leaf development by CLEs appears to be conserved from lower plants to angiosperms, CLEs have distinct roles at different stages of the plant life cycle, and the mechanisms by which they mediate these effects remain unclear.

Recent advances have significantly enhanced our understanding of the regulatory roles of CLE peptides in plant leaf senescence. Specifically, mutants lacking CLE14 and CLE42 function display a precocious senescence phenotype, while transgenic plants overexpressing these peptides exhibit delayed leaf senescence. This effect is corroborated by experiments with synthesized CLE14 and CLE42 peptides, which also delay senescence[66,67]. Detailed analyses reveal distinct mechanisms through which CLE14 and CLE42 modulate senescence pathways. CLE14 acts primarily through the reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling pathway. It upregulates JUNGBRUNNEN 1 (JUB1), a transcription factor that enhances the expression of ROS-scavenging genes such as CATALASE3 (CAT3) and ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE1/3 (APX1/3). This cascade effectively reduces ROS levels, thereby delaying the onset of leaf senescence[67]. In contrast, CLE42 influences the ethylene signaling pathway by suppressing ethylene biosynthesis in young leaves through downregulation of 1-AMINO-CYCLOPROPANE-1-CARBOXYLATE SYNTHASE 2 (ACS2) and promotes the accumulation of EIN3-BINDING F BOX PROTEIN (EBF1), leading to the degradation of ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3) and inhibiting senescence[66]. Furthermore, SERK4 and PXY have been identified as key regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis, possibly interacting with the signaling pathways activated by CLE14 and CLE42[66,67]. However, it remains to be determined whether these receptors can specifically perceive and respond to signals from both CLE peptides to modulate senescence processes.

-

Stomatal development is also regulated by CLE signals. Most pavement cells (PCs) of the leaf epidermis originate from meristemoid mother cells (MMCs), which undergo asymmetric divisions to produce large stomatal lineage ground cells (SLGCs) and smaller meristemoid cells. These cells can differentiate into PCs and guard cells (GCs), respectively[68]. The CLE9 peptide, initially identified in MMCs, meristematic cells, and GCs, binds to the RLK receptor protein HAESA-LIKE 1 (HSL1). Somatic Embryogenesis Receptor Kinase 1 (SERK1) enhances the interaction between CLE9 and HAESA-LIKE 1 (HSL1), which in turn negatively regulates the proliferation of stomatal lineage cells by destabilizing the transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH)[62]. Further research indicates that the activation of HSL1 by its ligands requires a SERK co-receptor kinase. Specifically, the HSL1-SERK1 complex recognizes the full INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION (IDA) signaling peptide, which is crucial for cell separation, but only partially recognizes CLE9 peptides. Receptor kinases BAM1 and BAM2, critical for regulating leaf epidermal cell division in Arabidopsis, bind the signaling peptide CLE9 with high affinity and specificity, significantly influencing leaf cell patterning. The HSL1–IDLs and BAM1/BAM2–CLE9 complexes independently regulate cell patterning in the leaf epidermis and may function antagonistically by interacting with distinct classes of signaling peptides[69]. Understanding the dynamics of these receptor-ligand-co-receptor complexes within stomatal lineage and cell differentiation pathways will enhance our insight into the complex signaling inputs that drive plant development.

-

Proper seed formation requires precise spatial and temporal coordination among the embryo, endosperm, and maternal components. In Arabidopsis, CLE8 is specifically expressed in young embryos and endosperm, where it functions both cell- and non-cell-autonomously to regulate basal embryo cell-division patterns, endosperm proliferation, and the timing of endosperm differentiation. Together, CLE8 and its downstream transcription factor, WUSCHEL-like homeobox 8 (WOX8), form a signaling module that promotes seed growth and overall seed size[70]. However, the receptor kinase that perceives the CLE8 signal has not yet been identified.

-

The rice CLE genes FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 (FON2)[71], FON2-LIKE CLE PROTEIN1 (FCP1)[72], and FON2 SPARE1 (FOS1)[73] control inflorescence and floral meristem size similarly to their Arabidopsis orthologs CLV1 and FON1[74]. The rice transcription factor OsWUSCHEL-related homeobox 4 (OsWOX4) also regulates meristem size and is negatively influenced by the CLE FCP1[75]. Similar findings have been observed in maize: thick tassel dwarf1 (td1) encodes a receptor kinase similar to CLV1, and fasciated ear2 (fea2) encodes an LRR protein that lacks a cytoplasmic domain, similar to its Arabidopsis counterparts[76,77]. These findings suggest that the classic CLV3–WUS feedback mechanism characterized in Arabidopsis is also conserved in monocots.

SlCLV3 has been shown to act as a peptide ligand that regulates inflorescence architecture, flower production, and fruit size in tomato[25]. In contrast to findings in Arabidopsis, there appears to be an active compensation mechanism between SlCLV3 and its closest paralog, SlCLE9. Loss of SlCLV3 function triggers the upregulation of SlCLE9 expression, thus maintaining stem-cell homeostasis in tomato, primarily through their shared receptor, SlCLV1. Additional receptors, including SlBAMs, may also contribute to the signaling of SlCLV3 and SlCLE9, which differs from the active compensation mechanism observed in Arabidopsis[78].

In Arabidopsis, CLE19 and six functionally redundant anther-expressed CLEs (CLE9, CLE16, CLE17, CLE41, CLE42, and CLE45) play a 'braking' role by suppressing the expression of ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS), a master regulator of pollen-wall development. This regulation is essential for maintaining appropriate expression of the tapetum transcriptional network and ensuring the biosynthesis of a suitable amount of sporopollenin[79]. The LRR receptor kinase PXL1, which has been proposed to function synergistically with PXY and PXY-LIKE2 (PXL2) in regulating vascular development, was also demonstrated to interact directly with CLE19. PXL1 is hypothesized to function as a receptor and SERKs as coreceptors for CLE19 during normal pollen development[80]. Another important study reported that BAM1 and BAM2 function redundantly to limit the production of sporogenous cells in the anther lobes. BAMs appear to promote differentiation of peripheral somatic cells while reducing the proliferation of sporogenous cells, akin to the role played by CLV1 in meristem maintenance. The biochemical similarities between BAM1/2 and CLV1 imply that the ligand for BAM1/2 may also belong to the CLE family[81].

CrCLV3, identified in the Ceratopteris genome, promotes cell proliferation and maintains stem cell identity during female gametangium formation by regulating the WOX gene, CrWOXA[82]. These findings not only pave the way for further research on CLE peptides in ferns but also help clarify the evolutionary development of CLE-WOX signaling pathways in land plants.

-

To tolerate abiotic stress, plants regulate their growth and development by integrating long-distance signals among cells (e.g., from root to shoot) and short-distance signals within organs or between cell types. CLE peptides play a crucial role in regulation at both scales. The CLE45 peptide ligand and its receptors, SKM1/SKM2, direct a pistil–pollen interaction, and the CLE45–SKM1/SKM2 signaling pathway sustains pollen performance and enables successful seed production under higher temperatures[83]. The Arabidopsis receptor-like kinase pair AtCLV2/AtCRN was recently shown to act together with AtCIK co-receptors to promote continued flower outgrowth under various thermal regimes[84], but the specific CLE peptide involved in temperature-dependent CLV2/CRN/CIK signaling is unknown. High-temperature treatment led to upregulation of MdCLE6/21 and MdCLE18 in apple (Malus domestica) and VvCLE6 in grapevine (Vitis vinifera), whereas cold stress enhanced the expression levels of MdCLE6/21, MdCLE10, and MdCLE16 and reduced the expression of MdCLE17[85,86].

The Arabidopsis CLV3-like peptide CLE25 has been shown to translocate from roots to shoots, inducing ABA accumulation and facilitating stomatal closure in response to dehydration[2]. Together with evidence for root–shoot CLE signaling during nodulation[13,87], these findings suggest that CLE peptides may participate in long-distance signaling and coordinate developmental responses to abiotic stress throughout the plant. Chemical synthesis and functional assays of peptides revealed that the NtCLE3 peptide from Nicotiana tabacum enhances drought resistance in three Solanaceae crops, including tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), pepper (Capsicum annuum), and eggplant (Solanum melongena)[88].

SlCLV3 is highly expressed in the pedicel abscission zone (AZ) in response to low-light stress in tomato, and knockout of SlCLV3 reduces low-light-induced flower drop. The molecular mechanisms involved in this response have been clarified: SlCLV3 signals in the AZ are perceived through SlCLV1 and SlBAM1, ultimately repressing the expression of SlWUS and inducing the expression of its negative regulatory targets KNOX-LIKE HOMEDOMAIN PROTEIN1 (SlKD1) and FRUITFULL 2 (SlFUL2). A CLE compensation mechanism also acts during pedicel abscission in tomato, as upregulation of SlCLE2 compensates for the loss of SlCLV3 during this process. These results demonstrate that CLE signaling pathways serve as an environmental buffering mechanism to ensure plant reproductive success.

-

A number of CLEs have documented roles in the interactions of plants with other organisms. For example, the signal peptides GmRIC1/2 (Rhizobium-induced CLE peptides 1 and 2) are produced during the formation of root nodule primordia in Glycine max and have been shown to activate GmNARK (nodule autoregulation receptor kinase) to control nodule number. Similarly, the nitrogen-induced MtCLE35 signaling peptide in M. truncatula acts through the super numeric nodules (MtSUNN) receptor and the miR2111 systemic effector to inhibit nodulation.

Recent evidence has demonstrated the involvement of plant CLEs in regulating arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis. The expression of MtCLE53 is significantly upregulated during AM colonization, and loss of MtCLE53 function increases the expression of AM-symbiosis-related marker genes, indicating that MtCLE53 acts as a repressor of AM symbiosis[89]. Likewise, SlCLE10 and SlCLE11 have been identified as inhibitors of AM colonization in tomato, and it is likely that at least SlCLE11 requires arabinosylation for its activity[90]. Fungal CLEs have been identified in the genomes of several phylogenetically distant AM fungi and have been shown to promote symbiotic interactions. Notably, exogenous application of RiCLE1 from Rhizophagus irregularis enhanced mycorrhization in M. truncatula[91]. It remains unclear whether plant and fungal CLEs interact to facilitate successful symbiosis.

The CLV3 peptide can be sensed by the flagellin receptor FLS2, which in turn activates MAPK phosphorylation and upregulates the expression of marker genes in the pattern-triggered immunity pathway. However, whether CLV3 can independently activate plant immune regulation remains controversial[92,93]. Arabidopsis clv1, clv2, and crn mutants exhibited greater resistance than wild-type plants to infection by the bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum and the oomycete Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. By contrast, the same mutants were more susceptible to infection by the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae and two species of necrotrophic fungi, including Botrytis cinerea. Interestingly, the effect on plant–pathogen interactions seems to be specific to AtCLV1, AtCLV2, and AtCRN and does not require the participation of other known CLAVATA signaling-pathway components (AtCLV3 and AtBAM) or downstream signaling components (AtPOL and AtWUS). By contrast, clv1 mutants are susceptible to infection by R. solanacearum[94]. This suggests that the CLAVATA signaling involved in plant–pathogen interactions may be distinct from that involved in the maintenance of meristematic tissues in stems[94].

Recent studies reveal that CLE peptides extend beyond plants, with increasing evidence of CLE-like peptides in organisms interacting with plants. These organisms can hijack plant CLAVATA signaling pathways using their own CLE-like signaling peptides. For example, nematodes secrete CLE precursors that exploit the plant's cellular secretion pathways, where they are processed by the plant cells. Arabidopsis receptors CLV2 and CRN perceive cyst nematode CLE effector proteins, which mimic plant CLE peptides and are essential for successful nematode infection[95]. These findings highlight the significant roles of CLE peptides in plant biotic interactions, although their specific functions in disease resistance and plant immunity still require detailed characterization.

-

Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are crucial for major physiological and biochemical processes in plants[96]. Plants adapt to N and P limitations by altering their root system architecture, among other developmental changes[97]. CLE genes have been noted for their role in symbiosis-independent responses to N and P starvation.

In Arabidopsis, N-responsive CLE peptides, such as AtCLE1, AtCLE3, AtCLE4, and AtCLE7, accumulate in the root vasculature to regulate lateral root development in an N-dependent manner. Overexpression of these genes inhibits lateral root outgrowth under nitrogen deficiency, whereas clv1 mutants display increased lateral root numbers and lengths during nitrogen starvation, accompanied by overaccumulation of AtCLE2/3/4/7 transcripts. This suggests feedback regulation of these CLE genes by the CLV1 receptor[1]. Additionally, N-induced CLE genes such as SlCLE2, SlCLE10, and SlCLE14, which are upregulated by nitrate in tomato, have been identified across various species[22,98−101]. The M. truncatula rdn1 and L. japonicus plenty mutants, which are defective in CLE arabinosylation, show N-dependent alterations in root architecture[102,103], pointing to a role for CLE peptides in root N adaptations. However, the biological functions of these N-induced CLE genes remain unknown. Mutations in CLV1 orthologs, such as MtSUNN in M. truncatula, LjHAR1 in L. japonicus, and GmNARK in soybean, result in increased lateral root length and density under optimal nitrogen conditions, whereas the CLV1-like ortholog FASCIATED AND BRANCHED (SlFAB) in tomato does not regulate lateral root development[104]. The involvement of the CLAVATA pathway in N-mediated regulation of root system architecture thus appears to vary significantly among plant species.

In Arabidopsis root tips, several CLE genes induced under phosphorus (Pi) starvation have been identified. Notably, AtCLE14 is upregulated in the root apical meristem under Pi-limiting conditions, where it mediates root meristem termination via the CLV2 and PEP1 RECEPTOR2 (PEPR2) signaling pathways[105,106]. Conversely, in several plant species including L. japonicus (LjCLE19 and LjCLE20), purple false brome (Brachypodium distachyon), and M. truncatula, other CLE genes are upregulated by high Pi levels[89,107−109]. In M. truncatula, MtCLE33 is induced under high phosphorus (Pi) conditions in roots, leading to a MtSUNN-dependent decrease in strigolactone biosynthesis genes and reduced root strigolactone levels compared to controls[110]. Strigolactones are phytohormones crucial for plant adaptation to Pi deficiency, influencing root and shoot plasticity and modulating plant-microbe interactions[111−113]. Thus, phosphorus-regulated CLE signals like MtCLE33 may modulate developmental responses to phosphorus availability, linking plant phosphorus status with plant-microbe interactions.

-

In addition to those in model plants, a considerable number of CLE signaling peptides have also been identified and functionally characterized in crops. Recent research on how modulation of CLE peptide signaling controls yield, quality, and stress resistance in crops such as rice, Zea mays, tomato, and G. max has shed light on CLE functions and provided important information for crop genetic improvement.

Crop yield traits are closely related to meristem development. Knockout of FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER 4 (FON4), a rice homolog of Arabidopsis CLV3, led to abnormal enlargement of the inflorescence and floral and shoot meristems, as well as an increase in the number of floral organs[114]. Subsequent research revealed that mutations at various FON4 loci could influence deterministic spikelet meristem production and determine the grain number per panicle[115]. ZmCLE7 and ZmFCP1, the maize homologs most closely related to CLV3, were shown to be recognized by the maize CLV2 ortholog FEA2 and to precisely regulate development of the inflorescence meristem. ZmCLE15 was also shown to function redundantly with ZmCLE7 in regulating meristem size and grain yield[78].

Gene-editing technology can be used to improve a wide variety of wild crop species and resources, leveraging valuable CLE peptide genes to generate suitable pre-breeding germplasm and thus facilitate de novo crop domestication. Weak promoter-edited alleles of ZmCLE7 and ZmFCP1 produced by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing caused abnormal development of the maize inflorescence meristem, resulting in significant variations in several maize yield traits and an obvious increase in yield per ear[116]. Disruption of the SlCLV3 promoter, which reduced SlCLV3 expression levels, led to an increase in the locule number of tomato fruit, a change known to have contributed to increased fruit size during tomato domestication[78]. Recent studies have demonstrated that the SlCLV3 promoter contains four conserved regions that exhibit additivity, synergy, and redundancy[117]. Mutations in one conserved region lead to a weak phenotype of increased fruit size, and combinations of mutations in multiple regions enhance this phenotype, suggesting the existence of complex cis-regulatory interactions within the SlCLV3 promoter[117]. These results highlight the potential for improvement of agricultural traits through fine-tuning of CLE gene promoters or leveraging of compensation and redundancy mechanisms via CRISPR-based editing, approaches that are likely to apply to a variety of crops.

-

As signaling molecules, CLE peptides exert significant biological effects at minimal concentrations. The application of CLE peptides at micromolar levels can alter the development of plant roots, leaves, and vascular bundles; promote symbioses; and influence biological processes such as stem-cell niche maintenance in shoot apices, anther development, pollen maturation, fruit development, drought response, and nodule formation. With advances in genomics, transcriptomics, and peptidomics technologies, research on CLE peptides has expanded from model plants like Arabidopsis to various crop species, identifying a growing number of CLE peptides. Currently, research on CLE peptide functions is primarily centered on their roles in plant growth and development. The functions of many CLE peptides remain unclear, especially those involved in responses to biotic stresses (e.g., disease resistance) and environmental changes such as temperature and humidity. Further exploration of these functions is needed, but obtaining T-DNA insertion mutants for studying CLE-peptide function through traditional genetic approaches is challenging. Moreover, identifying CLE peptides through biochemical methods is time-consuming and labor-intensive due to their low expression levels. Redundancy among CLE homologs and their receptor-like proteins further complicates functional studies. It will be necessary to integrate bioinformatics, molecular biology, genetics, and biochemical analysis to confirm the functions of new CLE-peptide genes.

The molecular mechanisms underlying known CLE peptides also require further in-depth analysis. Questions remain about the redundancy and specificity of these peptides, particularly how they regulate the same biological processes through positive, negative, or synergistic signals. This complexity suggests a sophisticated level of regulatory accuracy that still needs full elucidation. Additionally, the receptors and downstream signaling pathways for many functionally characterized CLE peptides are not well defined. The diverse actions of CLE peptides add to the complexity and precision of plant regulatory mechanisms, yet their specific mechanisms and associated receptors and signaling pathways require more detailed exploration. Advancements in high-throughput proteomics and mass spectrometry, along with the development of CRISPR screening systems capable of generating single or multiple receptor-like kinase mutants simultaneously, provide powerful tools for discovering new CLE peptide receptors and exploring their functions[118]. Moreover, various in vitro methods can verify interactions between CLEs and newly identified receptors[119]. To establish CLE-mediated transcriptional networks, advanced RNA-seq techniques are essential for identifying gene clusters responsive to CLE signals[120]. Additionally, technologies such as CROP-seq[121], CRISP-seq[122], and Perturb-seq[123], as well as CRISPR-based activation, interference, and epigenetic modification systems[116,124], offer methods to study how CLEs affect the expression of downstream transcription factors.

CLE signaling pathways cooperatively regulate complex plant growth processes through interactions with other hormone signaling pathways, including those of auxin[53], cytokinin[125,125,126], gibberellin[57,127], and abscisic acid[2,128]. However, the mechanistic details of how CLE signals interact with these other hormones require further investigation. Likewise, the mechanisms of short-distance CLE peptide transport, such as between anther somatic and reproductive cells during pollen formation, also warrant further study.

CLE peptides offer significant potential for crop improvement through molecular breeding. Targeted editing of CLE genes using CRISPR/Cas9 technology can enable the development of high-yield, high-quality, and disease-resistant varieties. For instance, edits to the cis-regulatory elements of CLV3 in wild tomato (Solanum pimpinellifolium) have produced superior cultivars[129]. Additionally, synthetic CLE peptides, which degrade rapidly in the environment, present an eco-friendly alternative to traditional agrochemicals, enhancing crop resistance and stress tolerance. In tomato, the roles of the AtCLE25 peptide in drought resistance and the SlCLE10 and SlCLE11 peptides in symbiosis underscore their potential in sustainable agriculture. However, challenges in optimizing peptide binding affinity and delivery for practical use persist, especially in horticultural crops and forest trees, which often have complex genomes, long growth cycles, and are recalcitrant to genetic transformation.

Overall, CLE peptides represent a promising research frontier in plant biology and agriculture. Despite technical challenges in their functional validation, advances in experimental techniques are expected to elucidate their molecular mechanisms, highlighting their potential to enhance crop productivity, resilience, and quality through genetic modification and synthetic biology.

This work has been supported by the Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation General Program (24ZR1419200). The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful and constructive suggestions and comments to improve the quality of the paper.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiang Y, Wang S; draft manuscript preparation: Wang S, Liang Y. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

No data was used for the research described in the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang S, Liang Y, Jiang Y. 2025. Plant CLE peptides: functions, challenges, and future prospects. Plant Hormones 1: e006 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0006

Plant CLE peptides: functions, challenges, and future prospects

- Received: 13 December 2024

- Revised: 21 February 2025

- Accepted: 27 February 2025

- Published online: 21 March 2025

Abstract: Peptide hormones have garnered significant research interest since their initial discovery in higher plants. As crucial components of intercellular communication, CLE peptides have been shown to regulate plant development in response to both developmental and environmental cues. Here, we present a systematic review of recent findings on CLE peptide signaling pathways and their associated mechanisms in plants. We summarize our current understanding of the biological functions and regulatory mechanisms of CLE peptides, highlighting (1) their roles in plant growth, including root, leaf, and reproductive development, with a particular focus on meristem regulation; (2) their involvement in mitigating abiotic stresses such as drought and low light; and (3) their contribution to plant–microbial interactions, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. We also suggest future directions for research on plant CLE peptides to enhance our understanding of their functions and promote their application in crop breeding.