-

Premature ovarian failure (POF) refers to a disease state related to ovarian failure caused by overdepletion of ovarian oocytes, and abnormalities in sex hormone levels[1]. Ovarian oxidative damage can cause serious ovarian dysfunction[2] and is one of the main factors resulting in POF. In mice treated with D-galactose (D-gal), the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) triggers an excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[3]. The toxicity of AGEs, combined with ROS-induced oxidative stress, significantly accelerates the deterioration or loss of ovarian function, mimicking the natural aging process observed in women[3,4]. Therefore, a mouse model of ovarian ageing induced by D-gal is a common method for investigating the mechanism of POF. POF can be influenced by multiple factors, such as insufficient nutrition, autoimmune diseases, genetic factors, iatrogenic factors, and environmental factors[5−8]. An effective aetiological treatment for POF is currently unavailable. Hence, alternative or complementary therapy has become the focus of POF research.

The increase in toxic metabolite production caused by ROS accumulation mainly induces ovarian granulosa cell apoptosis[9]. Many antioxidants, such as melatonin[10], resveratrol[11], epicatechin[12], and curcumin[13], can protect cells from ROS and may promote follicular development and survival; all of these compounds have been shown to improve D-gal-induced POF. Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is a naturally derived plant compound that exhibits a wide range of biological activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects[14−16]. Chen et al. reported that CGA improves the intestinal antioxidant capacity and decreases the degree of intestinal mucosal damage caused by oxidative stress[17]. Additionally, CGA effectively decreases the content of ROS, relieves oxidative stress, and reduces the degree of apoptosis of neurons[18], and Sertoli cells[19]. Therefore, CGA may also decrease the degree of ovarian damage caused by ROS and protect ovaries against POF. Nevertheless, the effects of CGA on POF mice are currently unclear.

Gut microbiota are intricately linked to host reproductive aging. Research has shown that several key aspects of reproductive function, such as serum oestrogen levels[20], follicle development, oocyte maturation, fertilization, implantation, and embryo migration[21], are significantly influenced by the gut microbiota. Moreover, studies have also uncovered a connection between gut microbiota dysbiosis and premature ovarian insufficiency[22,23]. Thus, timely intervention to restore the balance of gut microbiota may help delay ovarian aging. In this study, we hypothesize that CGA may possess the potential to correct the disrupted gut microbiota and exert beneficial effects on ovarian reserve function in mice with POF. To test this hypothesis, we used D-gal to accelerate ovarian aging in mice, and the POF models were constructed to: 1) determine the effects of CGA on ovarian function and oxidative damage-related factors in mice with POF; 2) identify the impacts of CGA on the gut microbiota composition of mice with POF. Elucidating these characteristics will not only provide a reference for identifying alternative or complementary therapies for POF but also offer theoretical support for studying the mechanism of POF.

-

Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were sourced from the Experimental Animal Center of Jilin University in Changchun, China. The mice were housed in an animal facility under controlled conditions, with a natural photoperiod of 12 h light/dark cycle, ambient temperature maintained at 22–25 °C, and relative humidity kept at 50%–60%. After a 1-week acclimatization period, the initial body weights of the mice were recorded. The mice were then randomly assigned into four groups: the control group (CON), the POF group (D-gal), the low-dose CGA group (CGA-L), and the high-dose CGA group (CGA-H). Mice in the D-gal, CGA-L, and CGA-H groups received daily intraperitoneal injections of D-gal (200 mg/kg/d[24]; G0750, Sigma, USA) for 42 consecutive days, while those in the CON group were injected with an equivalent volume of sterile saline. Then, sterile saline (CON and D-gal groups) or different doses of CGA (CGA-L, 100 mg/kg/d; CGA-H, 200 mg/kg/d[25]; C3878, Sigma, USA) were gavaged daily following daily D-gal injection. On day 42, following the completion of D-gal treatment, a subset of mice from each group was weighed, and faecal samples were collected in 5 ml sterile polypropylene tubes. These samples were immediately frozen at –80 °C for subsequent DNA extraction. Afterward, the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg) for general anaesthesia, and blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis. The ovaries were then excised and weighed promptly. The left ovaries were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis, while the right ovaries were stored at –80 °C for further biochemical assays, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT‒PCR), and Western blot analysis. The remaining mice were used to assess oestrous cycles through daily vaginal smears (one smear per animal) over the subsequent week. Vaginal smears were stained using a Wright's stain kit (G1040, Beyotime Biotech, China) and examined under a microscope (Nikon Eclipse, Nikon, Japan).

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, follicles/corpora lutea counting

-

Five ovarian samples from each group were selected for follicle and corpus luteum counting (one sample per animal). Mouse ovarian tissue was collected, fixed in paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. A single 4-μm-thick section was randomly selected from each ovarian sample, mounted on a glass slide, and stained using a H&E kit (G1120, Solarbio, China). The criteria for follicle and corpus luteum classification were as follows: primordial follicle: the oocyte is surrounded by a single layer of flattened granulosa cells; primary follicle: the oocyte is enclosed by a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells; secondary follicle: the oocyte is surrounded by more than one layer of cuboidal granulosa cells, but no antral cavity is present; antral follicle: the oocyte is enclosed by more than four layers of granulosa cells with a large antral space visible[26]; corpus luteum: composed of hypertrophic granulosa cells derived from the remnants of the follicle after ovulation[27]; and atretic follicle, the structure of the follicle was blurred, the zona pellucida contracted, and the follicle wall collapsed. In atretic follicles, oocytic nuclei shrink, granular layers decrease in size, chromosomes and the cytoplasm dissolve, and follicular membrane cells become hypertrophic[28].

Biochemical assays

-

Mouse serum was harvested from blood samples by centrifugation (900 × g, 10 min) for hormone assays. The serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and oestradiol (E2) levels in the serum of mice were determined via FSH (KA2330) and LH ELISA kits (KA2332) (Novus Biologicals, USA) and an E2 (582251) ELISA kit (Cayman Chemicals, USA). Ovarian tissue was washed with cold saline and homogenized (10,000 × g, 15 min) in Tris–HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). The supernatants were collected for further removal of insoluble proteins via centrifugation (100,000 × g, 60 min). Biochemical analyses of the resulting supernatant (cytosolic fraction), including total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) and catalase (CAT) activities and malondialdehyde (MDA) content, were performed via T-AOC kit (S0119), CAT (S0051) kit (Beyotime Biotech Inc., China), and MDA kit (A003-1) (Nanjing Jian Cheng Bioengineering Inc., China).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT‒PCR) assay

-

RNA was extracted from ovarian samples via the TRIzol reagent (15596026CN, Invitrogen, USA).

The quality and concentration of the extracted RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA) and confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. cDNA samples were obtained through reverse transcription via MonScriptTM RTIII All-in-One Mix with dsDNase kit (MR05101S/M, Monad Bio, China). The reaction mixture was thoroughly combined, and qRT‒PCR was performed using a three-step protocol under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 65 °C for 10 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The expression level of the target gene was determined using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method and normalized to the internal reference gene, Gapdh. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primers used for qRT‒PCR.

Genes Primer sequence (5'-3') Accession no. Length of

product (bp)Amh Forward: CCACACCTCTCTCCACTGGTA NM_007445.3 151 Reverse: GGCACAAAGGTTCAGGGGG Gapdh Forward: AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG NM_001411840.1 123 Reverse: TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA Western blot analysis

-

Protein lysates extracted from ovarian tissues were subjected to 12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (ISEQ00010, Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 1× protein-free rapid blocking buffer (PS108P, Shanghai Yamei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) for 15 min. They were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-Akt (9272, CST, USA), anti-p-Akt (9271, CST, USA), polyclonal anti-Nrf2 (16396-1-AP, Proteintech, China), anti-HO-1 (10701-1-AP, Proteintech, China), and anti-β-actin (4970, CST, USA). Following this, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (SA00001-1, Proteintech, China) or an HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (SA00001-2, Proteintech, China) at room temperature for 60 min. The blots were then visualized using a Tanon 5200 imaging system (Tanon, China) and analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH, USA). For normalization, Western blot data were compared against the internal reference proteins: Akt (for p-Akt) or β-actin (for Nrf2 and HO-1).

In situ TUNEL staining assay

-

The embedded ovarian sections mentioned above were stained using a One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (C1089, Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Specifically, one section from each glass slide was randomly chosen and incubated with the TdT labeling buffer at 37 °C for 60 min. Subsequently, the sections were counterstained with DAPI to visualize the nuclei. The nuclei of TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells were stained green and observed via an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse, Nikon, Japan). To rule out histological dissimilarities between ovarian tissues, four areas were randomly assessed per slide (five animals per group, five slides per animal), and 100 areas (4 × 5 × 5 = 100) were randomly assessed per group. Both TUNEL-positive granulosa cells and total granulosa cells were enumerated within the antral follicles. The ratio of TUNEL-positive granulosa cells (%) was analysed via NIH ImageJ software.

Faecal microbiota analysis

-

Mouse faecal DNA was extracted as described in the manufacturer's protocol. Common primers (341F, 5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′; 806R, 5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′) were employed to amplify the hypervariable V3 and V4 regions of the 16S rDNA gene. The resulting amplicon libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA), and the 250 bp paired-end sequences generated were evaluated via QIIME2 (version 2019.4)[29]. Briefly, the primer sequences and low-quality reads (Q < 25) were denoised via the DADA2 plugin. High-quality paired-end clean reads were subsequently merged into tags via FLASH, and chimaeras and singletons were subsequently removed to acquire amplicon sequence variants (ASVs)[30]. ASVs were assigned to taxa according to the Greengenes2 database[31]. Alpha diversity was determined based on rarefied ASVs via QIIME2 (version 2019.4). Beta diversity was measured on the basis of the Bray‒Curtis distance. Dissimilarities in the faecal bacterial communities between different groups were determined via PERMANOVA on the basis of Bray‒Curtis distances with 999 permutations via the 'vegan' package of R (v3.0.3). In addition, the numbers of ASVs shared by and solely detected in various faecal samples are shown in a Venn diagram. To identify taxonomic biomarkers in POF mice, we performed linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis[32] on taxa that showed significant differences in abundance between the CON and D-gal groups, with an LDA score threshold set at > 2. The taxa that were more abundant in the D-gal group than in the CON group were referred to as 'D-gal-predominant taxa' (biomarkers of mice with POF). Notably, the same comparison was made between the CGA and D-gal groups to infer the genera whose abundance might be modulated by the administration of CGA.

Associations of the faecal microbiota composition with POF-related symptom parameters

-

The associations between the faecal microbiota composition and POF-related parameters (serum hormone levels, ovarian oxidative stress indices, and the number of follicles and corpora lutea) were investigated via the R package to evaluate Spearman's correlation coefficients.

Statistical analysis

-

Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro‒Wilk and Kolmogorov‒Smirnov tests in GraphPad Prism (version 8). Unless otherwise indicated in the figure legends, statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA or Kruskal‒Wallis test.

-

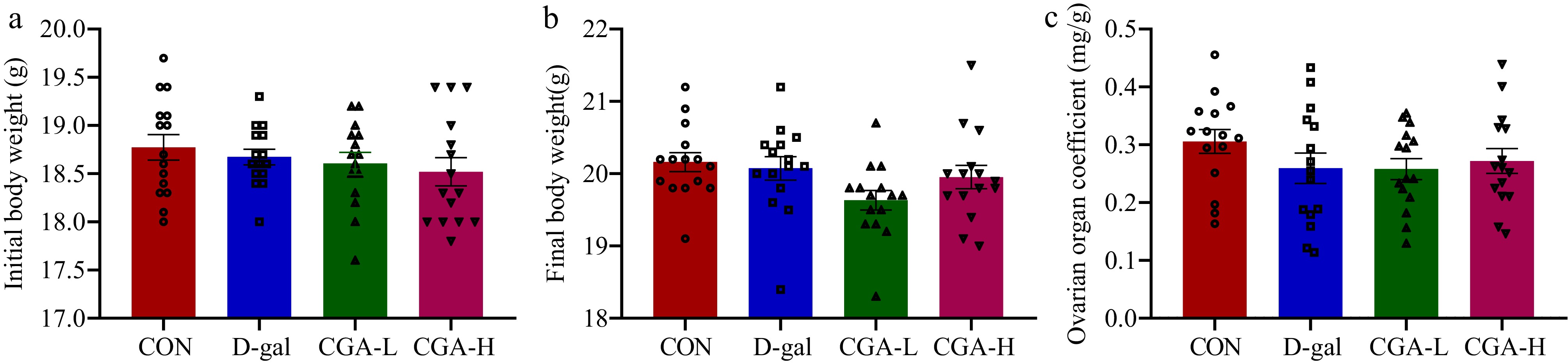

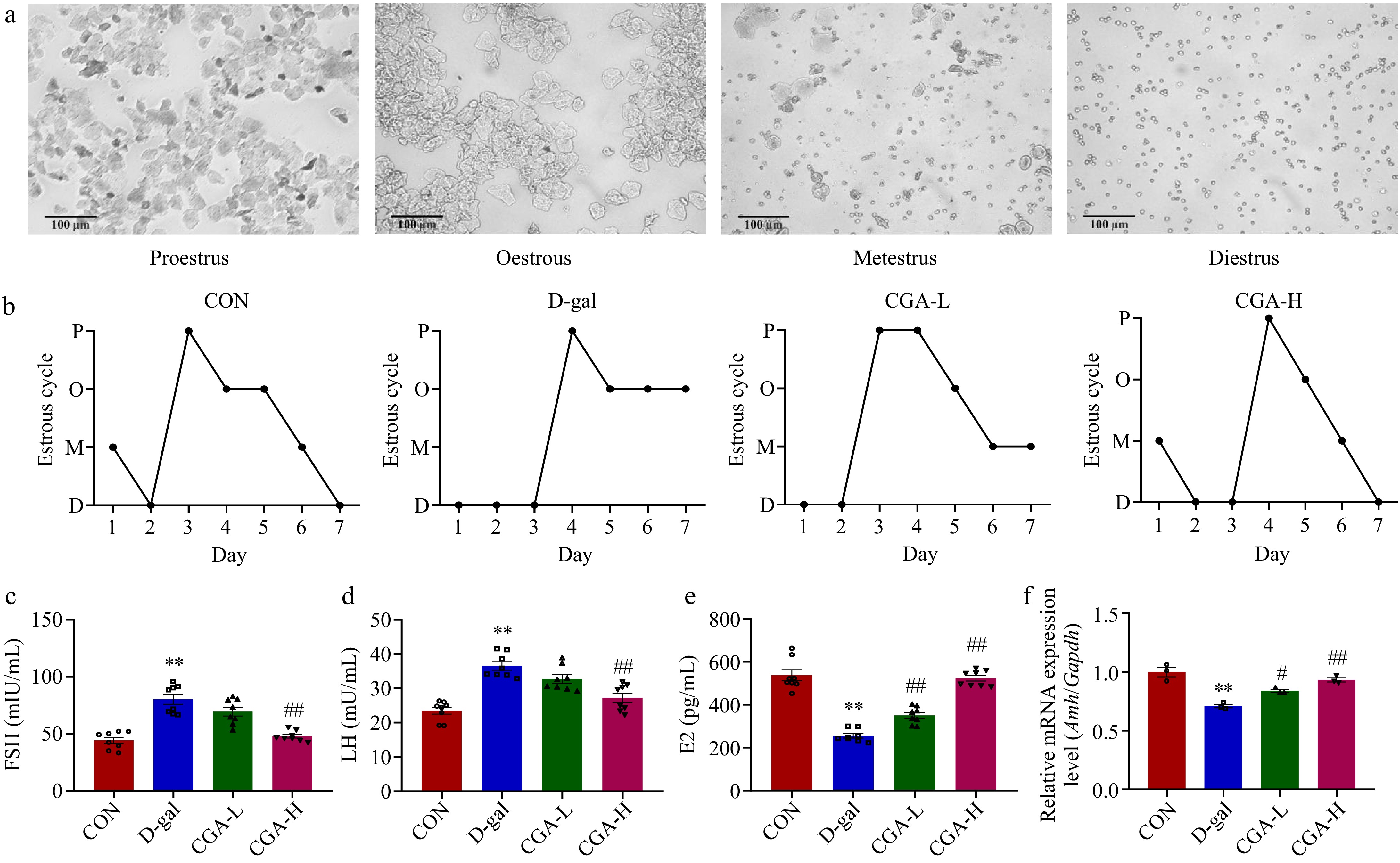

There were no significant differences in initial body weights, final body weights, and ovarian organ coefficient among the mice in the CON, D-gal, CGA-L, and CGA-H groups (p > 0.05; Fig. 1a−c). The oestrous cycles of the mice were observed via daily vaginal smears. The mice in the CON group presented regular oestrous cycles; however, most of the mice in the D-gal group presented an irregular oestrous cycle, which specifically manifested as an increased oestrous duration and diestrus phase. Oestrous cycle disorders improved after CGA treatment, especially high-dose CGA treatment, which rebuilt the normal oestrous cycle (Fig. 2a, b). Compared with those in the CON group, increased serum FSH (p < 0.01) and LH levels (p < 0.01) but decreased serum E2 levels (p < 0.01) and ovarian Amh mRNA expression (p < 0.01) were noted in the D-gal group. Nevertheless, these changes were ameliorated in the mice in the CGA groups (p < 0.05, p < 0.01; Fig. 2c−f), indicating that the POF model was successfully established and that CGA administration improved POF symptoms.

Figure 1.

Effects of CGA on body weights and ovarian organ coefficient in POF mice. The (a) initial body weights, (b) final body weights, and (c) ovarian organ coefficient were confirmed (n = 15). The ovarian organ coefficient was calculated as follows: ovarian organ coefficient (mg/g) = ovarian weight (mg) / final body weight of mice (g). The data are shown as the means ± SEMs.

Figure 2.

Effects of CGA treatment on ovarian performance in POF mice. (a) Representative vaginal smears (scale bar: 100 μm); (b) four stages (P, O, M, and D indicate proestrus, oestrous, metestrus, and diestrus, respectively) of the oestrous cycle (n = 5); serum (c) FSH, (d) LH, and (e) E2 levels (n = 8); and (f) ovarian tissue Amh mRNA expression was evaluated (n = 3). Data are shown as the means ± SEMs. ** Significance vs the CON group (p < 0.01), # and ## significance vs the D-gal group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01).

Effect of CGA administration on follicular development and ovarian oxidative stress in POF mice

-

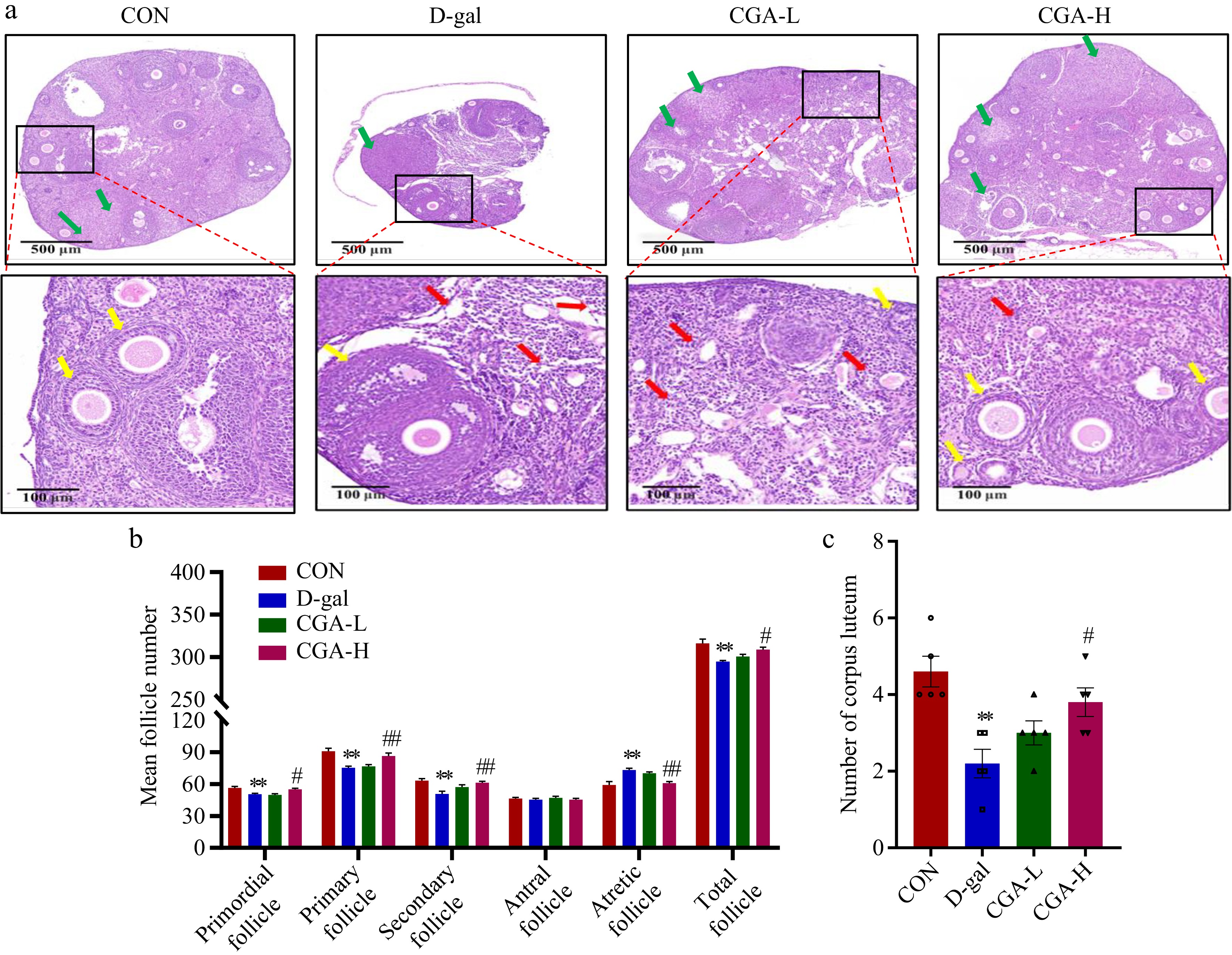

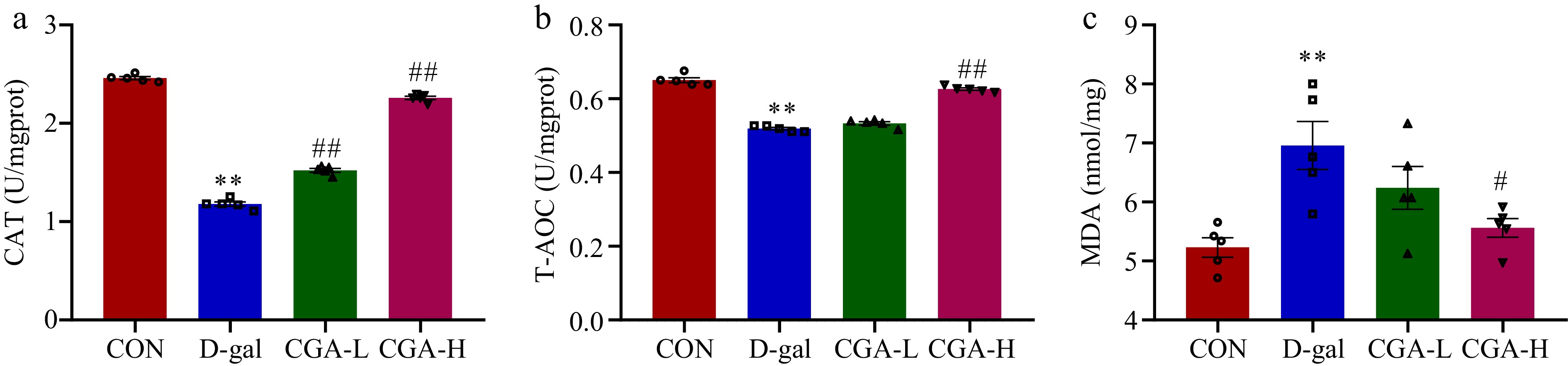

In the D-gal group, the counts of primordial (p < 0.01), primary (p < 0.01), secondary (p < 0.01), total follicles (p < 0.01), and corpora lutea (p < 0.01) were significantly reduced, but the number of atretic follicles (p < 0.01) was significantly higher compared to the CON group. These alterations were mitigated by high-dose CGA treatment (Fig. 3a−c). Additionally, compared to the CON group, the activities of CAT (p < 0.01) and T-AOC (p < 0.01) were markedly decreased, while the levels of MDA were significantly elevated in the D-gal group (p < 0.01). In the CGA-H group, CGA treatment led to significantly higher levels of CAT (p < 0.01) and T-AOC (p < 0.01), as well as lower contents of MDA (p < 0.01) compared to the D-gal group (Fig. 4a−c). These results indicate the strong antioxidant potential of CGA. According to the above results, high-dose CGA treatment resulted in better ovarian performance than low-dose CGA treatment. Therefore, we selected a high dose of CGA (200 mg/kg/d, named the CGA group) as the experimental concentration for subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Effects of CGA treatment on follicular development in POF mice. (a) Histology of ovary sections stained with H&E. The yellow arrows represent the primordial, primary, secondary, or antral follicles. The red arrows represent atretic follicles. The green arrows represent corpora lutea. Scale bars = 500 μm at 5× and 100 μm at 20× magnification. The counts of (b) follicles, and (c) corpora lutea at various stages of development in the ovaries are summarized (n = 5). The data are shown as the means ± SEMs. ** Significance vs the CON group (p < 0.01), # and ## significance vs the D-gal group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Effect of CGA treatment on ovarian oxidative stress in POF mice. (a)−(c) The CAT and T-AOC activities and the MDA content were determined via commercial ELISA kits (n = 5). The data are shown as the means ± SEMs. ** Significance vs the CON group (p < 0.01), # and ## significance vs the D-gal group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01).

Effect of CGA administration on ovarian cell apoptosis and oxidative stress signalling pathway-related protein expression in POF mice

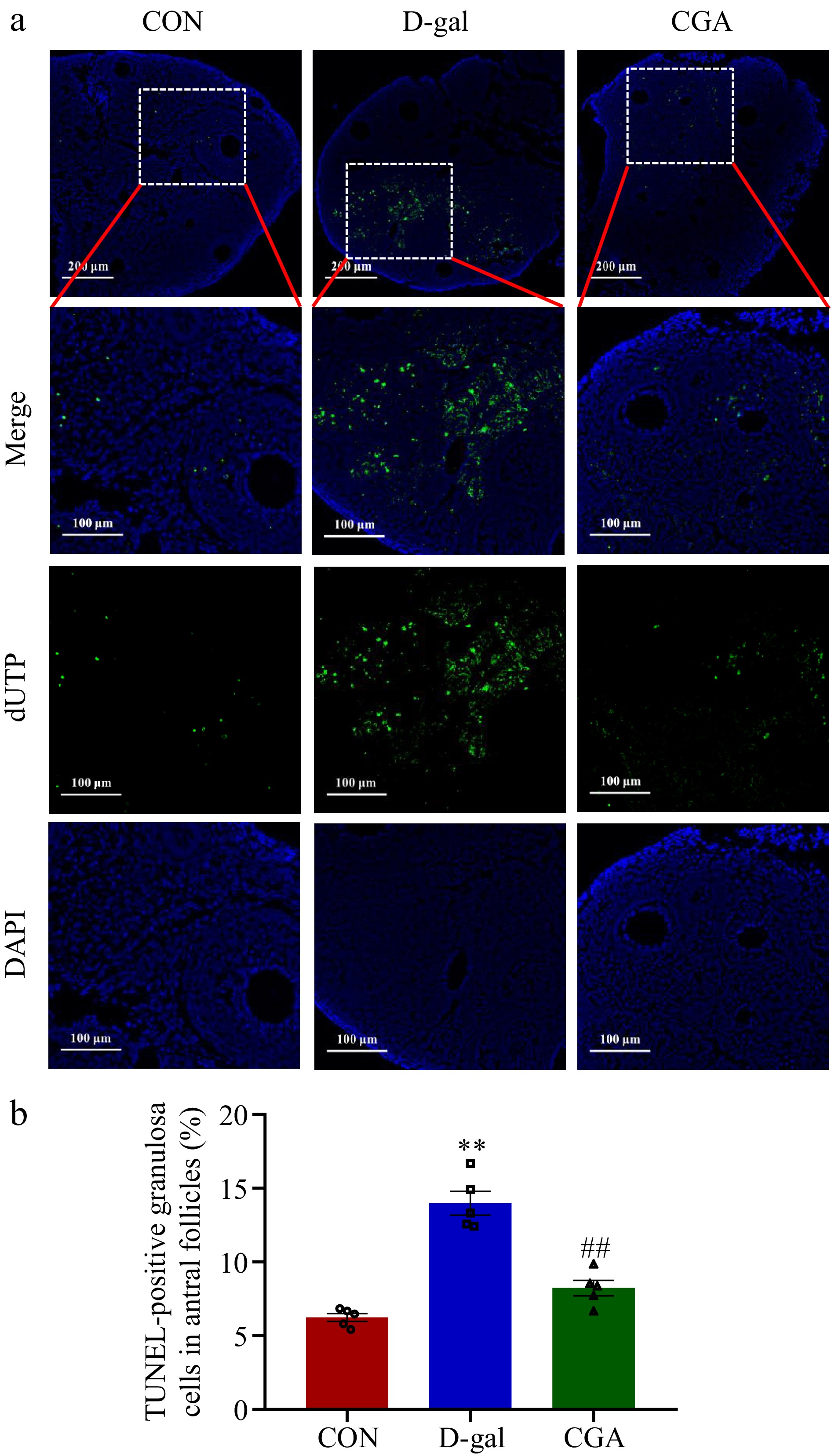

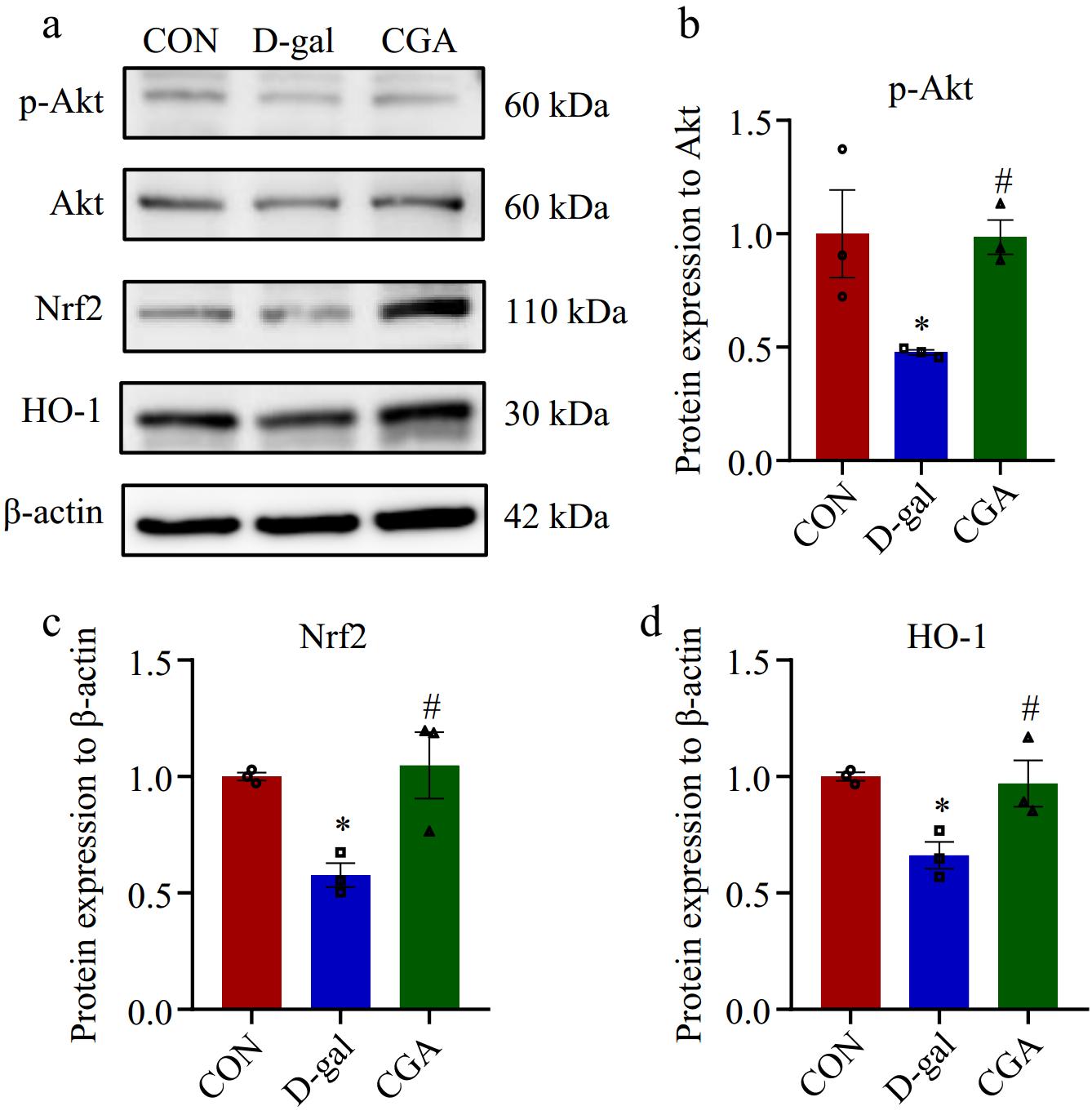

-

The apoptotic granulosa cells were stained green (Fig. 5a). There were more apoptotic cells in the POF mice than in the control mice (p < 0.01), but the number of apoptotic cells was significantly reduced by treatment with CGA (p < 0.01, Fig. 5b). Lower protein expression levels of p-Akt (p < 0.01), Nrf2 (p < 0.05), and HO-1 (p < 0.05) were detected in the D-gal group, while these expression levels markedly increased after gavage of CGA (p < 0.05 Fig. 6a-d).

Figure 5.

Effect of CGA treatment on ovarian cell apoptosis in POF mice. (a) Apoptosis was detected via in situ TUNEL fluorescence. The nuclei of TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells were stained green. Scale bar = 200 μm at 10.7× and 100 μm at 24.5× magnification. (b) The percentage of TUNEL-positive granulosa cells in antral follicles was compared among the three groups (n = 5). The data are shown as the means ± SEMs. ** Significance vs the CON group (p < 0.01), ## significance vs the D-gal group (p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

Effect of CGA treatment on the expression of proteins associated with the oxidative stress signalling pathway in POF mice. (a) The expression levels of associated proteins were assessed via Western blotting. (b)−(d) The expression levels of associated proteins were quantitatively detected (n = 3). The data are shown as the means ± SEMs. * Significance vs the CON group (p < 0.05), # significance vs the D-gal group (p < 0.05).

Effects of CGA on the faecal microbiota in POF mice

-

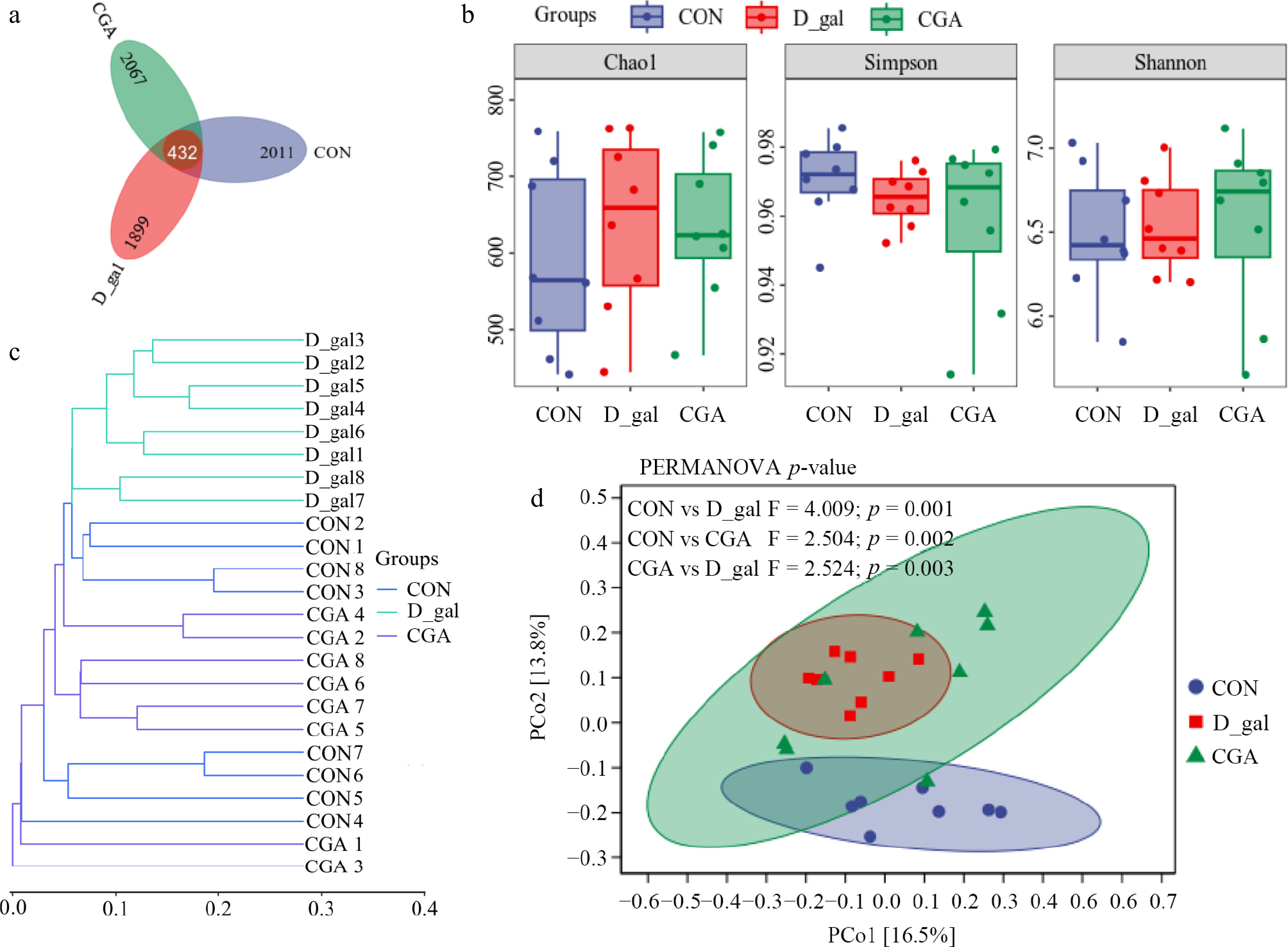

A total of 2,443, 2,331, and 2,499 ASVs were detected in the CON, D-gal, and CGA groups, respectively, with average Good's coverage values of 99.70% ± 0.12%, 99.73% ± 0.10%, and 99.77% ± 0.04%, respectively (Fig. 7a). The faecal microbial alpha diversity did not significantly differ between the CON and D-gal groups or between the D-gal and CGA groups (p > 0.05; Fig. 7b). Nevertheless, the faecal microbial beta diversity analysis (Fig. 7c,d) revealed distinct differences between the groups (PERMANOVA, CON vs D-gal: p = 0.001; CON vs CGA: p = 0.002; CGA vs D-gal: p = 0.003). CGA treatment tended to shift the faecal microbial beta diversity from a profile similar to that of D-gal mice to a profile more similar to that observed in CON mice.

Figure 7.

Effects of CGA treatment on faecal microbial diversity in POF mice. (a) Venn diagram displaying the number of shared ASVs within each sample (n = 8). (b) Alpha diversity was evaluated via the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices (n = 8). Beta diversity was measured based on the Bray‒Curtis distance and shown by (c) hierarchical clustering analysis, and (d) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) (n = 8). PERMANOVA was used to detect differences between the groups.

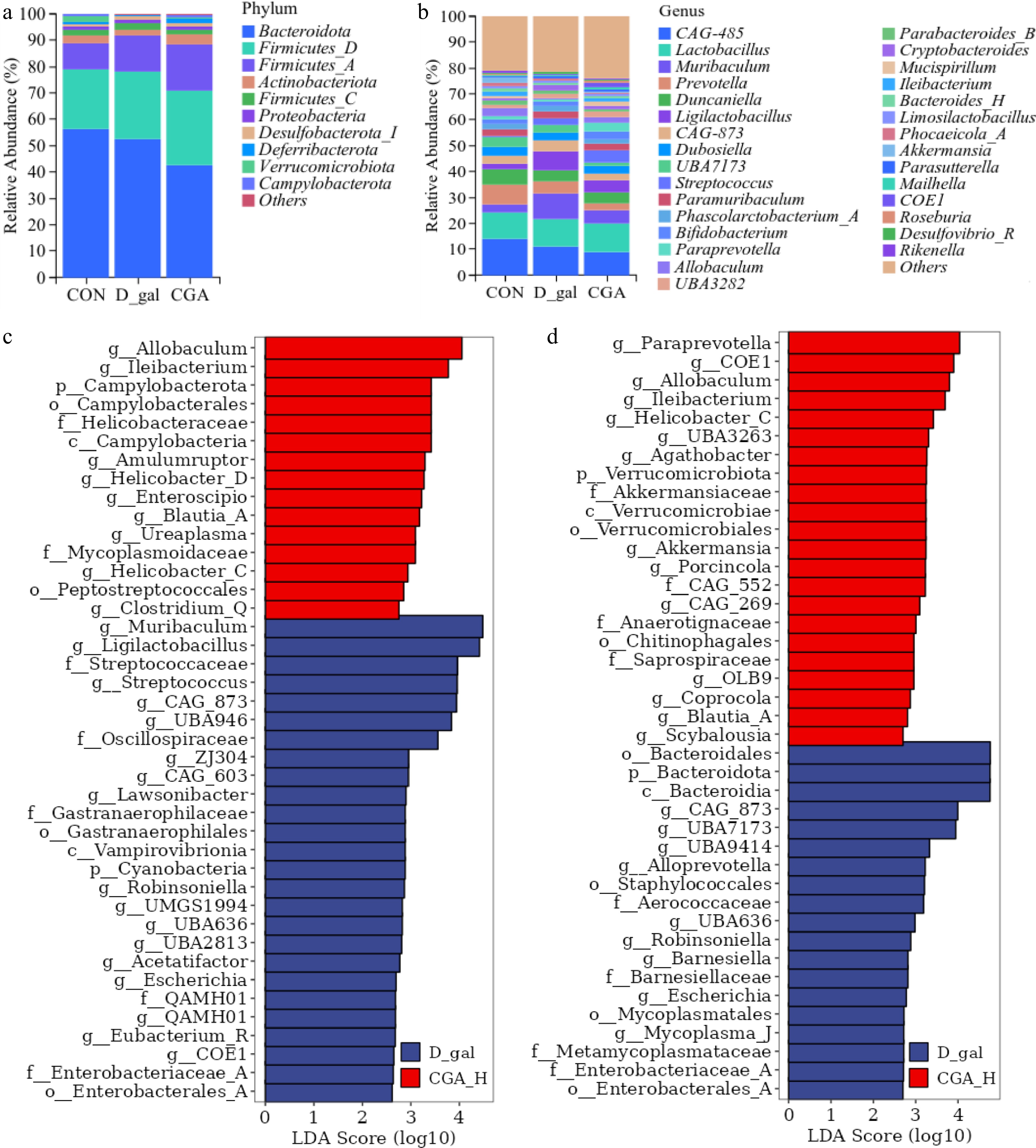

Taxonomic composition analysis of the faecal microbiota (Fig. 8a, b) revealed that in all the mouse faecal samples, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes_D, and Firmicutes_A were the predominant phyla, and Bacteroidetes were the most abundant of the three. In addition, CGA-485, Lactobacillus, Mucispirillum, Prevotella, Duncaniella, and Ligilactobacillus were the most common genera in all groups of mice. LEfSe analysis (Fig. 8c,d) revealed that the relative abundances of six D-gal-predominant taxa (biomarkers of mice with POF), which were assigned to the genera CGA_873, UBA636, Robinsoniella, Escherichia, Enterobacterales_A, and Enterobacteriaceae_A, decreased in the CGA group. Interestingly, Allobaculum, Ileibacterium, and Blautia_A, which were enriched in the CON group, were also enriched in the CGA group. The data imply that the abundance of these bacteria might be altered by the addition of CGA.

Figure 8.

Effects of CGA treatment on the faecal microbial composition of POF mice. The relative abundances of the (a) phyla, and (b) genera of the faecal microbial taxa in the mice. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis with an LDA score > 2 for the faecal microbial communities of the mice. (c) The enriched faecal microbial taxa between the mice in the CON group and those in the D-gal group, and (d) the enriched faecal microbial taxa between the mice in the D-gal group and those in the CGA group are shown (n = 8). The red bars suggest enrichment in the CON or CGA group; the blue bars suggest enrichment in the D-gal group.

Associations of the faecal microbial composition with POF-related symptom parameters

-

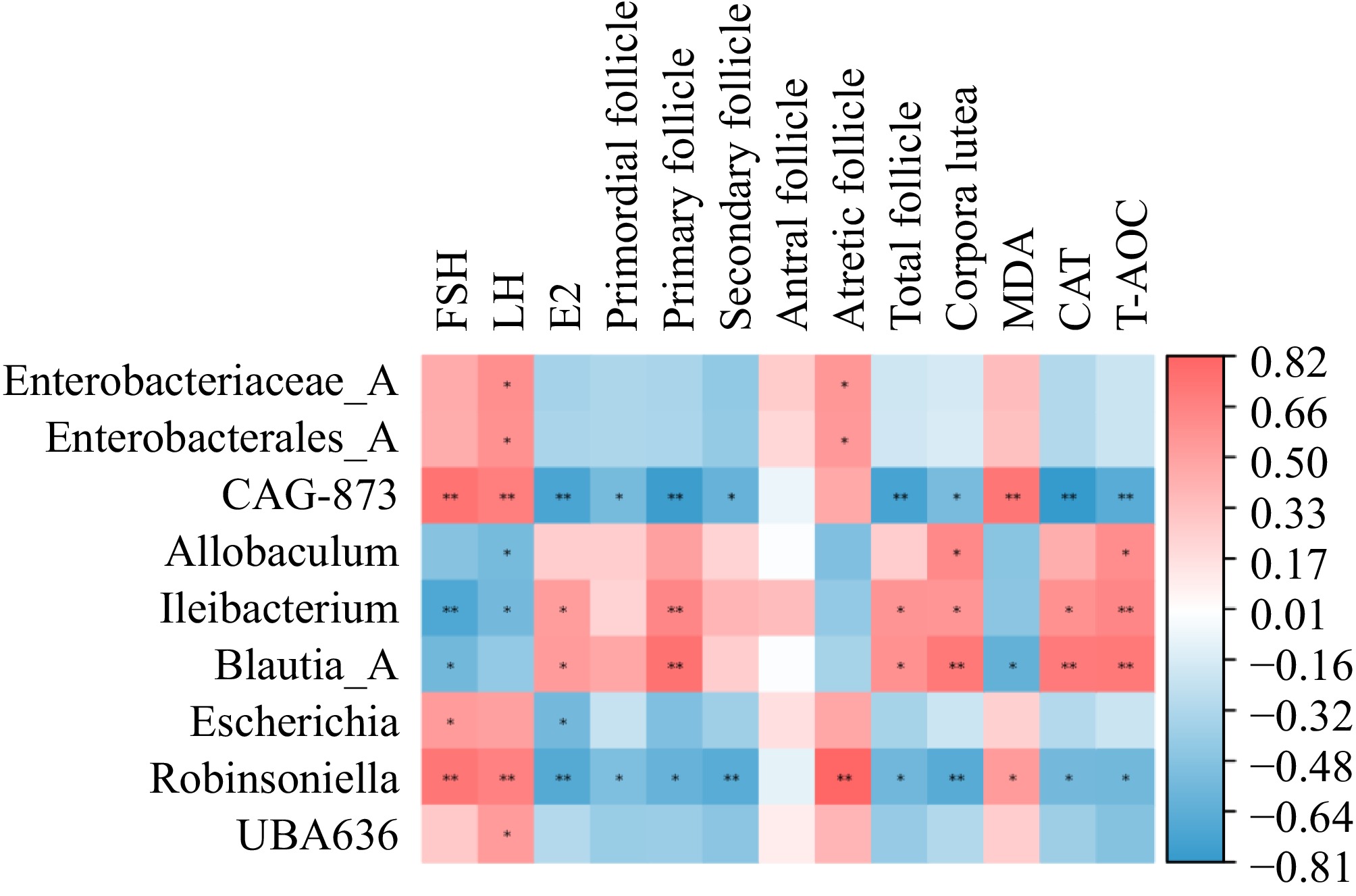

We next explored the associations between the CGA-responding faecal microbiota and POF-related symptom parameters via Spearman's correlation coefficient analysis. The data (Fig. 9) revealed that Enterobacterales_A, Enterobacteriaceae_A, and Robinsoniella abundances were associated with LH levels and the number of atretic follicles. The abundances of Ileibacterium and Blautia_A exhibited a significant adverse relationship with FSH levels but were strongly positively associated with E2 levels; the number of primary follicles, total follicles, and corpora lutea; and CAT and T-AOC activity. Moreover, the abundance of Ileibacterium presented a strong negative association with the LH level, and the abundance of Blautia_A was inversely related to the MDA content. CGA_873, Escherichia, and Robinsoniella abundances were closely related to FSH levels but negatively correlated with E2 levels. Additionally, the abundances of CGA_873 and Robinsoniella were negatively related to the numbers of primordial follicles, primary follicles, secondary follicles, total follicles, and corpora lutea, and CAT and T-AOC activity but were positively connected with the MDA content. Moreover, Allobaculum abundance was strongly negatively related to LH levels and was positively linked to T-AOC activity and the number of corpora lutea. In contrast, the abundances of CGA_873 and UBA636 were positively correlated with LH levels.

-

The POF model of mice was successfully established with D-gal treatment and was demonstrated by clinical symptoms and indices of POF, including oestrous cycles, serum hormone levels, and ovarian Amh mRNA expression, which is in agreement with the results of earlier studies[3,4, 24]. Studies have reported that D-gal-induced POF enhances FSH and LH bioactivity, inhibits E2 production[3, 33], and increases ROS levels, follicular atresia, and impaired fertility[4, 34]. AMH is an indicator of ovarian ageing and reflects the number of preantral follicles[3, 35]. In women, serum AMH levels gradually decrease with age[36], indicating that low AMH levels are associated with ageing and ovarian failure. CGA is an antioxidant and antiapoptotic substance that reduces the accumulation of ROS, relieves oxidative stress, and reduces neuronal apoptosis[17,18]. Therefore, CGA may also protect ovaries against ageing. In the present study, two different doses of CGA were administered orally to POF model mice. As expected, the anti-POF effect of CGA was obvious, and a higher dose resulted in better efficacy. CGA administration improved ovarian reserve, as indicated by rebuilding the normal oestrous cycle; decreased serum LH and FSH levels; reduced atretic follicle numbers; elevated serum E2 levels and ovarian Amh mRNA expression; and increased primordial, primary, total follicle, and corpora lutea numbers in POF model mice. Moreover, CGA administration increased the expression of proteins (p-Akt, HO-1, and Nrf2) related to the oxidative stress signalling pathway. The increased expression of p-Akt can downregulate the expression of proapoptotic proteins, which is one of the key ways to regulate cell survival[37], while Nrf2 can eliminate ROS through sequential enzymatic reactions, such as HO-1[38]; this may explain why higher T-AOC and CAT activities but lower MDA contents and apoptotic cell ratios in the antral follicles were detected in CGA-treated POF model mice. These results suggest that CGA treatment relieves POF symptoms.

Previous findings have shown that the gut microbiota impacts endocrine metabolism by shifting the gut microbial composition and its metabolites[23, 39]. In women, clinically premature ovarian insufficiency is characterized by structural dysregulation of the gut microbiota, which can accelerate the degeneration of ovarian function[40,41]. Next, 16S rDNA sequencing was used to determine the response of the gut microbiota to POF and CGA treatment. Alpha diversity is one of the main indices used to evaluate gut microbial composition richness and homogeneity. As demonstrated previously, D-gal-treated mice possess alpha diversity similar to that of control mice[23]. Similarly, we found no indistinct difference in the alpha diversity of the faecal microbiota between the mice in the CON and D-gal groups. Moreover, the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices of the CGA-treated mice were not significantly different from those of the POF model mice, suggesting that CGA treatment had no obvious effect on the alpha diversity of the faecal microbiota in the D-gal groups of mice. Beta diversity reflects the diversity of species complexity in a sample at the population level. In this study, beta diversity was measured on the basis of the Bray‒Curtis distance, and PCoA and hierarchical clustering analysis were used to determine the structural modifications of the faecal microbiota among the groups. The results revealed that the faecal microbiota of D-gal group mice significantly differed from that of CON and CGA group mice, whereas CGA treatment tended to shift the faecal microbial beta diversity from that of D-gal group mice to that of CON group mice. Previous studies have demonstrated that gut microbial beta-glucuronidase (gmGUS) can convert oestrogen from its inactive form to an active form, thereby influencing host oestrogen levels[22, 42]. Dysregulation of the gut microbiota has been shown to lead to decreased gmGUS activity and disrupted oestrogen metabolism[21]. Given the strong association between oestrogen levels and ovarian aging[22], gut microbial activity has significant implications for reproductive health. In this study, although marked differences in faecal microbial beta diversity and serum E2 levels were observed between the CON and D-gal groups, CGA treatment partially mitigated these differences. This finding further supports the intricate relationship between ovarian aging and the gut microbiota.

To understand the effects of CGA administration on key phylotypes of the gut microbiota in POF mice, the microbial compositions of the faeces of the mice in the CON, D-gal, and CGA groups were compared. Studies have shown that Allobaculum and Blautia reduce oxidative stress and downregulate the expression of inflammatory mediators[43]. Blautia ameliorates inflammatory and metabolic diseases[44]. The Ileibacterium and Blautia abundances decreased in mice with premature ovarian insufficiency[23]. Ovarian aging is frequently associated with oxidative stress and inflammation. Oxidative stress can accelerate follicle loss and atresia[45], while inflammation may represent one of the key mechanisms underlying reproductive aging[46]. These results suggest that Blautia, Allobaculum, and Ileibacterium may be potentially beneficial host bacteria and that their presence leads to improve POF. Women with POF typically exhibit elevated levels of FSH and reduced levels of E2[3]. Therefore, the proportion of Blautia, Allobaculum, and Ileibacterium, serum E2 levels, total follicle number, and corpora lutea number were lower, while serum FSH levels and atretic follicles number were higher in the D-gal group than in the CON group. Moreover, CGA ameliorates ovarian oxidative injury and enhances the antioxidant status of ovarian tissue[47], and the combination of indole-3-carbinol and CGA restores the relative abundance of Allobaculum in the gut microbiota and alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice[48]. These findings advise that CGA treatment may play a role in improving ovarian oxidative stress. Consistent with these findings, the ovarian CAT and T-AOC activity were meaningly increased, while MDA content was significantly reduced in the mice treated with CGA than in those in the D-gal group. Furthermore, Spearman's correlation coefficient analysis revealed that the abundances of Ileibacterium and Blautia_A were strongly positively correlated with E2 levels, the number of primary follicles, total follicles, and corpora lutea, and CAT and T-AOC activity. Moreover, the abundance of Allobaculum was significantly positively associated with corpora lutea number and T-AOC activity. These data demonstrate that there is a potential relationship between gut microbiota and anti-POF-related symptom parameters. Conversely, CGA treatment prevented the proliferation of UBA636 (family Erysipelotrichaceae), Robinsoniella, Escherichia, Enterobacterales_A, Enterobacteriaceae_A, and CGA_873 (family Muribaculaceae) in D-gal-treated mice. Research has shown that the abundances of Erysipelotrichaceae and Robinsoniella, which are generally conditioned microbes, are significantly enriched in mice with chronic diseases and are associated with gut inflammation and ecological disorders[49−51]. Moreover, clinical research has shown that the abundances of Escherichia, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterobacterales are significantly increased in perimenopausal patients with abdominal obesity[52], suggesting that these bacteria may be involved in ovarian ageing. Therefore, UBA636 abundance was strongly positively related to LH levels. Robinsoniella abundance was positively related to FSH and LH levels, atretic follicle numbers, and the MDA content. Enterobacterales_A and Enterobacteriaceae_A abundances were positively related to LH levels and atretic follicles number, whereas Escherichia abundance was closely related to FSH levels. However, few studies have investigated the enriched genus CGA_873. The genus CGA_873 belongs to the family Muribaculaceae. Muribaculaceae abundance is significantly negatively associated with Allobaculum abundance in type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats[53], advising that Allobaculum may regulate ovarian function by regulating the abundance of its related microbiota, such as CGA_873 (Muribaculaceae). This finding may explain why a lower abundance of Allobaculum but a greater abundance of CGA_873 were observed in the D-gal group of mice. Overall, CGA treatment can mitigate the effects of POF. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota may contribute to the pathogenesis of POF. Restoring the balance of target gut microbiota (Allobaculum, Blautia_A, Ileibacterium, CGA_873, UBA636, Robinsoniella, Escherichia, Enterobacterales_A, and Enterobacteriaceae_A) could represent a novel strategy for delaying the progression of POF. Notably, although a potential link between POF and target gut microbiota gut microbiota has been suggested, the precise nature of this relationship remains to be elucidated.

-

CGA restored the disturbed oestrous cycle and normalized gut microbiota in POF mice. In addition, CGA significantly alleviated ovarian oxidative stress damage and improved ovarian function in POF mice. The findings provide valuable evidence supporting the potential therapeutic application of CGA in treating female POF. However, the clinical efficacy and optimal dosing of CGA in human POF patients remain to be determined and require further investigation.

This research was supported by the Jilin Provincial Scientific and Technological Development Program (Grant No. YDZJ202301ZYTS355) and the College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program at Jilin University (Grant No. 202310183341), China.

-

The research plan was carried out in strict accordance with the 'Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals at Jilin University'. The Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of Jilin University reviewed the ethical welfare of the animal experiments as follows: SY202404006, approval date: 20240401. The research strictly adheres to the principles of 'replacement, reduction, and refinement' to minimize harm to the animals, with their health and well-being prioritized throughout the experimental process.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: project management, funding procurement, and manuscript review/editing: Liang S, Zhang Y; formal analysis: Qu H, Wang Y, Li S, Pan H, Xiang D, Yan C, Wang T, Zhang J; investigation: Qu H, Wang Y, Li S, Pan H, Xiang D, Yan C, Wang T, Zhang J, Liang S, Zhang Y; writing – original draft: Qu H, Sun H, Sun B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study can be accessed from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The raw amplicon sequence data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under the Accession no. PRJNA1132568.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Hexuan Qu, Yanqiu Wang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Qu H, Wang Y, Li S, Pan H, Xiang D, et al. 2025. Effects of chlorogenic acid on gut microbiota composition and ovarian function in mice with D-galactose-induced premature ovarian failure. Animal Advances 2: e011 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0011

Effects of chlorogenic acid on gut microbiota composition and ovarian function in mice with D-galactose-induced premature ovarian failure

- Received: 01 February 2025

- Revised: 10 March 2025

- Accepted: 17 March 2025

- Published online: 25 April 2025

Abstract: Premature ovarian failure (POF) refers to a disease state linked to ovarian failure caused by overdepletion of ovarian oocytes, abnormalities in sex hormone levels, and abnormalities in the gut microbiota. POF often comes with oxidative damage. However, the effect of chlorogenic acid (CGA) administration on POF has not yet been explored. The current study evaluated improvements in ovarian dysfunction, ovarian oxidative stress, ovarian apoptosis, and the gut microbiota in mice with D-galactose (D-gal)-induced POF that were subsequently treated with CGA. CGA treatment significantly promoted follicle development and decreased the ratio of apoptotic granulosa cells in antral follicles of POF mice. CGA treatment also restored the irregular oestrous cycle and serum hormone levels, and attenuated ovarian oxidative stress injury by increasing the expression of correlated proteins (p-Akt, Nrf2, and HO-1) in POF mice. 16S rDNA sequencing revealed significant alterations in the gut microbiota structure and abundance between the control and POF groups, and most of these alterations were reduced after CGA intervention. Spearman's correlation coefficient analysis exhibited that the regulatory effect of CGA treatment on POF-related parameters was closely connected with the abundances of Allobaculum, Blautia_A, Ileibacterium, CGA_873, UBA636, Robinsoniella, Escherichia, Enterobacterales_A, and Enterobacteriaceae_A in the gut microbiota. In conclusion, CGA intervention represents a promising therapeutic approach for POF, providing valuable insights for its application in treating female POF.

-

Key words:

- Chlorogenic acid /

- Premature ovarian failure /

- Oxidative stress /

- Apoptosis /

- Gut microbiota composition