-

Epigenetics has been reported as a major factor in diseases like diabetes[1], genomic imprinting[2], and various cancers[3]. Increasing recognition of the role of epigenesis has altered scientific approaches to understanding cancer-related genes. Large-scale scrutiny of these aberrations indicates that the reduced transcription of major regulatory genes leads to malignant phenotypes[4]. Subtle modifications alter the DNA, or the associated histones can be passed on to future progeny. The reversible nature of these modifications makes them a striking area of research for epi-drug development[5].

Genetic instability and mutations have been considered the critical factor in most cancers. Current studies propose that epigenetic alteration is an underlying cause of clonal expansion in tumors. Over the last three decades, research investigating epigenetic defects identified several potential mechanisms, including acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, sumoylation, DNA methylation, histone modification, nucleosome remodeling, and non-coding RNA-mediated epigenetics[4]. Scientists have prominently recognized methylation and histone modification as key processes that drive genomic imprinting through interdependent pathways[6].

DNA methylation and histone modifications are crucial epigenetic mechanisms driving hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by altering gene expression[7]. DNA methylation occurs at CpG islands which are rare throughout the human genome but are often found in the proximity of promoters. 50-70% of all CpG islands in the heterochromatic region are methylated, while unmethylated CpG islands in euchromatin regions ensure the transcriptional activation of the regulatory genes[6,8−10]. The promoters of malignancy suppressor or tumor activator genes associated with 5' CpG islands are methylated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT3a and DNMT3b)[11]. S-adenosyl methionine acts as a methyl group supplier to methyltransferases[12] and therefore mediates cancer development. Hypermethylation, and hypomethylation can hamper the cell cycle by either silencing or activating regulatory genes. In particular, hypomethylation plays a major role in DNA replication leading to genetic disruption and chromosomal instability[13]. On the other hand, hypermethylation of 5' CpG islands in the vicinity of tumor-suppressor gene promoters impedes transcription, thus, leading to enhanced tumor formation[14].

Histone modifications are a post-translational modification that involves acetylation and methylation of lysines at the histone tails in both euchromatin and heterochromatin[15]. There are four core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, that form an octamer around which DNA is coiled. During acetylation, histone acetyltransferase enzymes (HATs) catalyze histone N-terminal lysine residues, while deacetylation involves histone deacetylases (HDACs)[16]. The opposite charges on the positive lysine in histones and negative DNA allow them to form a compact chromatin structure that can conceal regions of DNA from transcription factors. Acetylation of H3 and H4, therefore, abolishes the charge from lysine and loosens the compact bundle of DNA and histones. This exposes different promoter regions and allows the binding of transcription factors. Lysine methyltransferases perform mono-, di-, and tri-methylation of histone lysine residues. In cancer cells, the methylation pattern is altered in H3K9 and H3K27[17]. Current studies have disclosed that H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 mono-methylation stimulate gene transcription[18,19], whereas H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 tri-methylation leads to epigenetic silencing[19]. Now, epigenetic research has shown that the centromeric histone H3 variant leads to the formation of CENP-A stable chromatin, which gives the centromere an epigenetic label. During the cell cycle, the presence of CENP-A ensures a balance between cell division and centromere propagation[20].

The main difference between DNA methylation and histone modification is the relative stability of the interaction. DNA methylation is a more stable modification, while on the other hand, histone modifications are more transient[14], and strenuous to analyze. Later, scientists observed that DNA methylation and histone modification complement each other during developmental stages[21].

Notably, epigenetic pathways are involved in the main type of primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[22]. Different geographical areas show variations in the rate of occurrence and etiological factors for HCC. Several environmental factors involved in HCC development have been linked to epigenetic changes, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, chronic alcohol intake, and aflatoxin[23]. Research to understand the mechanisms involved in liver cirrhosis revealed many pathways that showed association with HCC. These pathways include the p53 pathway, the Rb pathway, the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) pathway, and the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. The irregular signaling in these pathways might be due to the activation of oncogenes and silencing of tumor suppressor genes[24].

HCV is the cause of widespread chronic liver disease. Almost 58 million people are infected with HCV worldwide[25]. HCV is a member of the Flaviviridae family. This 9.6 kb RNA virus was first reported in 1989[26,27]. The genome comprises a single open reading frame that encodes a polyprotein of 3,000 amino acids and non-translated regions situated at the 5' and 3' terminus[28]. Various studies have reported adverse effects of HCV infection on both oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that in turn disturb cellular pathways. This would lead to chromatin remodeling, RNA-associated silencing, silencing of tumor suppressor genes by hypermethylation, and oncogene activation by hypomethylation[29].

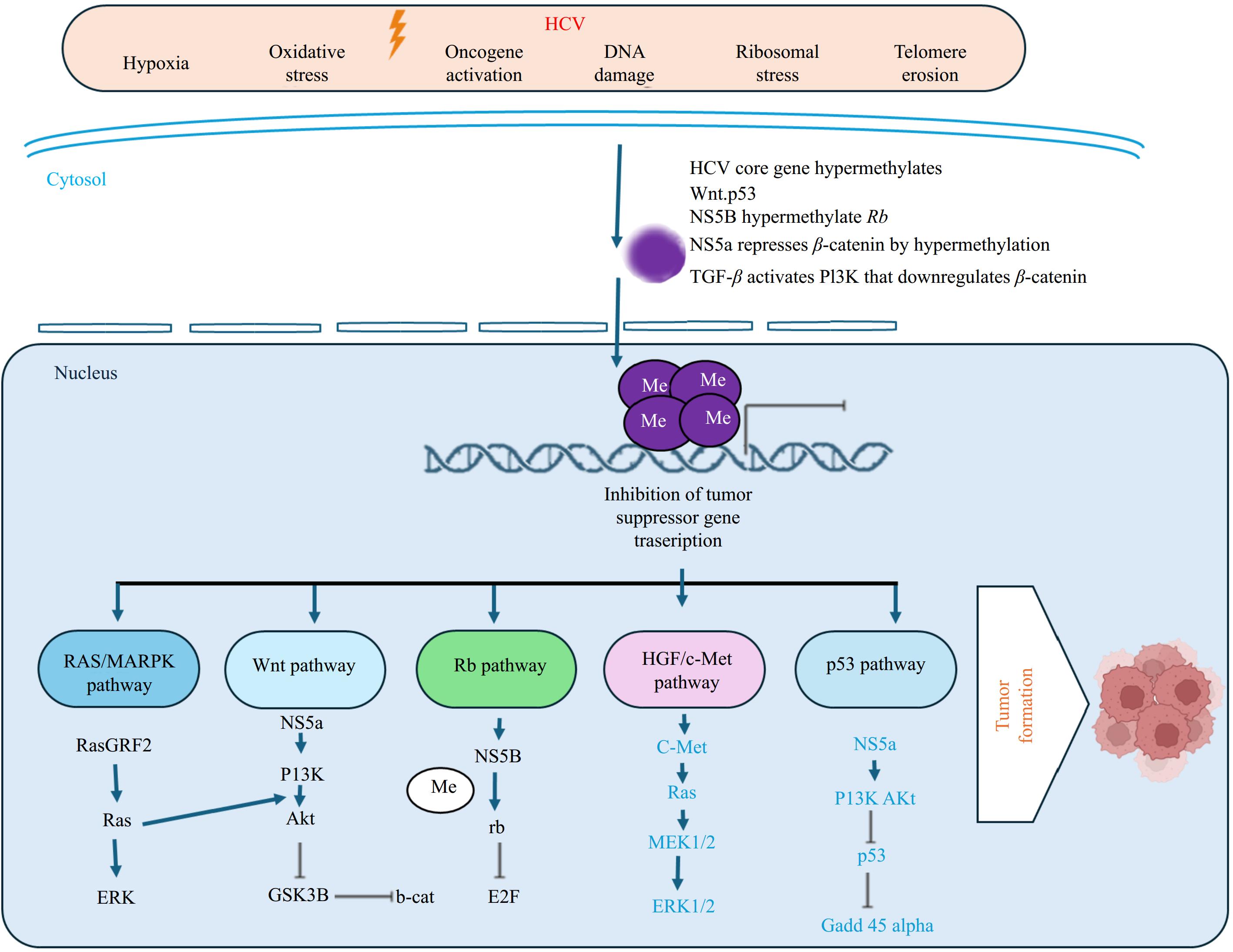

Several notable tumor suppressor genes are p53, Rb, p21, p27, p14ARF, E-cadherin, Axin 1, APC, SOCS1/3, RASSF1A, NORE1, KLF6, and FHIT, which have been studied in a plethora of research. HCV proteins hypermethylated CpG islands within the promoters of these genes, which silences their transcription[29] and allows an E2F transcription factor-mediated increase in unwanted cell growth. Figure 1 depicts a general concept of HCV-mediated HCC. It also shows various tumor suppressor genes that play a vital role at different stages of the cell cycle.

Figure 1.

HCV infection hypermethylates promoter CpG island of Tumor Suppressor Gene and silences its activity. Different HCV genes control p53, rb, TGF-β, HGF/c-Met, RAS/MAPK, and Wnt pathways and disrupt the functionality of tumor suppressor genes Dysfunctional TSGs allow defective DNA to sneak out cell cycle checkpoints. Consequently, leads to the proliferation of cells with damaged DNA and develops tumorigenesis. Created with BioRender.com.

In this review, HCV-mediated methylation of tumor suppressor genes will be discussed to provide an abridged overview of this fatal disease.

Retinoblastoma gene and HCV

-

The retinoblastoma gene, Rb, is one of the most well-studied tumor suppressor genes that obstruct the cell cycle at G1 and that entry into the S-phase. Rb silencing has been observed in various cancers such as soft tissue carcinoma, retinoblastoma, osteosarcoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancers[30]. Rb promoters contain a CpG Island of 600 bp that is normally unmethylated[31], whereas infectious agents can cause hypermethylation of CpG islands within this promoter[30].

Earlier it was thought that methylation of only specific CpG sites could lead to cancer. In 1993 however, Ohtani-Fujita et al.[32] proved that the entire promoter of Rb underwent hypermethylation in the presence of CpG methylase, which down-regulated its expression. Complete promoter methylation reduced its activity to 8%, whereas HpaII or FnuDII methylase partially methylates it and thus partially inactivates it. At that time, it was not clear whether the reduced activity of the Rb gene could cause cancer or if it was by random chance[33]. To explore this mystery, Stirzaker et al.[34] used bisulfite sequencing to investigate methylation of the Rb promoter in 1997. They found varying levels of hypermethylation in all tumor cases. The results indicated different hypermethylation patterns in the promoter region that were not limited to specific sites[35]. Other data about hypermethylation of the Rb gene promoter in HCV patient samples revealed reduced transcription and increased tumor induction[36]. Zhang et al. analyzed the Rb gene methylation status in HCC patients who were coinfected with HBV and HCV, and they witnessed a trend of hypermethylation[37,38].

p16, p14, p15 genes and HCV

-

p16, a tumor suppressor gene, is essential for the phosphorylation of the Rb protein that maintains the integrity of DNA during the cell cycle checkpoint G1-S phase[39]. It is located on chromosome 9p21 and is involved in various human cancers. Data shows that p16 undergoes genetic and epigenetic modifications which promote oncogenic activity in normal cells. p16 hypermethylation was observed along with an increased level of α-fetoprotein in the serum of HCC patients, making it an attractive biomarker for tumor detection[40]. In 2001, a study was conducted to detect the methylation status of the p16 gene promoter in different cases of HCC. It was found that hypermethylation silenced p16 expression in premature hepatocarcinogenesis only in patients who were infected with HCV or HBV. This study paved a new path toward identifying and treating liver cancer in its early stages[41]. Another study confirmed the efficacy of early malignancy diagnosis by identifying hypermethylation of the p16 gene and the DAPK gene in HCC patient blood samples[42]. Later, p16 down-regulation was observed in HCC patients due to promoter hypermethylation of CDKN2A[43]. Recently, p16 promoter methylation was found to be more prevalent in HCV or HBV-positive HCC patients as compared to cirrhotic liver diseases caused by non-viral agents[44].

Before 2002, it was thought that hypermethylation of a single gene caused cirrhosis; however, it was shown that multiple hypermethylated genes could be observed in HCC[45]. That same year, researchers in Taiwan (China) confirmed the prevailing notion that higher methylation levels are seen with increasing age during HCV infection, and all tumors from elderly patients showed reduced p16 expression[46]. They also identified malfunctions in the p14, p16, p53, and Rb pathways. The p14 protein prevents the degradation of the p53 protein. Hypermethylation of the p14 promoter was observed in far fewer HCV cases than in the p16 promoter[47,48]. The deleterious effect of promoter methylation of p14, p15, and Rb1 genes on the Rb pathway was confirmed by research conducted in the subsequent year, as shown by the absence of Rb1 expression among patients with HCV-induced HCC[49]. p16 hypermethylation was observed to be one of the most impactful alterations in HCV-induced HCC patients, yet hypermethylation was also detected in p15, p14, Rb, and PTEN (encodes a phosphatase that prevents tumor formation) genes[48]. This suggests that multiple hypermethylated genes may be involved in the development of liver cancer in the presence of HCV.

The p14 and p15 (the mediator of TGF-β-induced cell arrest) tumor suppressor genes are of interest due to their role in the cell cycle and their relation to p16. Interestingly, the p14 gene is within the CDKN2A locus and plays a role in monitoring the integrity of the G1-G2 phase. The p14 gene contains three exons (1-β, 2, and 3), where exons 2 and 3 are shared by the p16 gene. A study conducted on an Egyptian population suffering from HCV-induced HCC showed hypermethylation of the p14 promoter that can be specifically used as an early tumor detection marker[50]. p16 is also significantly homologous to the p15 protein and exists 25 kilobases from the p15INK4B/MTS2/CDKN2 gene[51]. p15 is expressed in response to transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). p15 inactivates CDKN4 and CDKN6, which then stops the G1-S phase transition. Therefore, the absence of TGF-β leads to p15 silencing. There are doubts that p15 acts as an independent tumor suppressor gene[51], but it is clear that the methylation status is altered as detected by methylation-specific PCR in HCV-mediated HCC. Hypermethylation of the p14, p15, and p16 promoters was reported in cancer cases[52].

In 2009, a cohort of Thai patients suffering from HCV were tested for promoter methylation. Methylation-specific PCR data showed hypermethylation of the P16INK4a promoter in 41.4% of tumors and 6.9% of normal liver tissues[53]. Throughout these studies, methylation-specific PCR has been used as the primary method in establishing the relationship between disease symptoms and methylation status[37,50].

p53 gene and HCV

-

p53 is a major tumor suppressor gene that controls apoptosis, maintains genome integrity and plays a vital role in angiogenesis. Very few studies on the p53 promoter hypermethylation status have been conducted during HCV infection[24]. HCV or HBV-mediated HCC cases showed hypermethylation in p53 and Rb promoters[37] though most of the research reported mutations in the p53 gene[54]. The core gene of HCV has been reported as a positive as well as a negative regulator of p53 in different cell lines[55].

Various (CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDH1, GSTP1, SOCS1, APC) genes and HCV

-

SOCS-1 negatively regulates cytokines that signal through the JAK/STAT3 pathway, whereas APC inhibits tumor formation through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. SOCS-1, APC, and p15 promoters were found to be significantly hypermethylated in HCV-induced HCC patients as compared to HCV-negative HCC patients[56]. The SOCS-1 gene promoter has been reported to be hypermethylated during HCV-mediated chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Studies have shown that the frequency of hypermethylated tumor suppressor genes increases from the early stages of fibrosis to the later stage of liver cirrhosis[57].

CDKN2A blocks MDM2-induced degradation of p53, whereas CDKN2B prevents the activation of the CDK kinases, and thus controls cell cycle G1 progression[58]. Epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor gene is initiated by viral infections that cause the development of HCC. A study based on an Indian cohort found that six tumor suppressor gene (CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDH1, GSTP1, SOCS1, and APC) promoter regions showed that the CDKN2B promoter was more frequently hypermethylated compared to APC and GSTP1 (plays a role in detoxification and antioxidant system). These findings showed that hypermethylated CDKN2B, SOCS1, CDH1, and GSTP1 play a prime role in the pathogenesis of HCC. Thus, the development of HCC in response to HCV may be linked to methylation profiles of tumor suppressor gene promoters[59].

The APC gene plays a prime role in promoting proper signaling in the Wnt pathway. The frequency of APC promoter methylation was observed in almost 80% of HCV-induced HCC cases[59,60].

The immunoreactivity score (IRS) of expressed proteins revealed that APC methylation in HCV-infected cells is comparatively more than in normal cells[61]. A high-throughput methylation technique was employed to investigate methylated CpG sites that are associated with HCV-induced HCC and demonstrated that the APC promoter was hypermethylated[62].

p27 and HCV

-

p27, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, monitors cyclin-dependent kinases during the G1-S phase transition. In HCV-associated HCC, immunohistochemical analysis showed down-regulated expression of p27 in HCV-mediated HCC patients. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation, western blot analysis, and MSP data indicated that p27 expression was silenced due to p16 promoter hypermethylation[63].

SPINT2 and HCV

-

SPINT2, a serine protease inhibitor, inhibits the HGF activator, which prevents the formation of active hepatocyte growth factor. SPINT2 was reported to be hypermethylated during HCV infection for the first time in 2009[63]. The study presented SPINT2, CCND2, and RASSF1A as potent, highly sensitive, and specific markers to differentiate between HCC and non-HCC samples. Another study conducted on SPINT2 confirmed a strong link between HCV infection and HCC development via hypermethylation[64].

NORE1A and HCV

-

The potential of NORE1A as a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker is highlighted by the correlation between its downregulation in HCC and its poor prognosis[65]. The sensitivity and specificity of HCC detection, especially in the early stages, may be improved by combining NORE1A with methylation and protein markers. Compared to AFP, the HepaClear panel, which combines protein markers and hypermethylated CpG sites, showed a sensitivity of 84.7% for early-stage HCC[66].

EFEMP1 and HCV

-

Epidermal growth factor containing Fibulin-like Extracellular Matrix Protein 1 (EFEMP1) is located at chromosome 2p16 and regulates angiogenesis. One case study observed that the EFEMP1 gene was hypermethylated in tumorous tissue sampled from a woman of 68 years. Double expression array analysis showed down-regulated expression of the gene in this patient with HCV-associated HCC[67]. According to Zhao et al.[68] and Ma[69], 130,512 CpG sites across the whole genome have been analyzed for the association between HCV infection and the development of HCC. They found that 228 CpG sites were associated with HCV infection, 17,207 with cirrhosis, and 56 with HCV infection and cirrhosis collectively. They also found that 2,109 (53.8%) CpG sites within promoter regions of the entire genome were significantly hypermethylated. Table 1 shows the role of tumor suppressor genes within different phases of the cell cycle. Furthermore, the development of HCC induced by HCV infection was comparatively more than HBV-induced HCC[70].

Table 1. Tumor suppressor genes regulating cell cycle phases.

Cell cycle phases Tumor suppressor genes Effect of hypermethylation Function Refs G1-S PTEN[71], p15[72], p16[73], p18[74], p19[75], p27[76], SOCS1[77], CDKN2A[78], CDKN2B[78], RASSF1A[79], Rb[71] Loss of cell cycle control, uncontrolled proliferationCyclin D-CDK4/6 activation, bypass of G1 checkpoint HCV NS5b is associated with Rb gene of the host cell and down-regulates its expression. p27, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor.SOCS-1 down-regulates cytokines of JAK/STAT3 pathway CDKN2A degrades p53 CDKN2B controls G1phase progression. RASSF1A is a potent, highly sensitive, and specific marker to differentiate between HCC and non-HCC samples. [58,64,80,81] S p53[82], p21[83] Impaired DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest NS5a forms a complex with the p53 gene and, therefore, down-regulates p21 expression. [84] G2-M PTEN[85] Inactivation of tumor-suppressive phosphatase activity PTEN encodes a phosphatase that prevents tumor formation. [48] M p53, p21[86], APC[87] Impaired DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest APC gene of the Wnt pathway was found to be hypermethylated in almost 80% of HCV-induced HCC cases [88] -

HCV Core protein has been observed to down-regulate p53 expression and promote unattended cell growth. It has been reported as a positive regulator of the p53 gene that prevents unattended cell propagation[89]. Another group of researchers observed that the HCV Core of genotype 1a was a negative regulator of the p53 gene in COS-7 and HeLa cells. These contradictory activities of the HCV Core may be associated with different genotypes and cell cultures[90]. HCV Core-induced p53 silencing HepG2 cells. A study conducted in 2018 showed HCV Core-mediated down-regulation of the p53 gene using a luciferase reporter in HepG2 cells. The doxycycline-regulated Rat1 cell line transfected with HCV Core showed reduced Rb expression and unregulated cell expansion[91].

A study conducted on the effects of HCV Core on p16 gene methylation and expression proved that its promoter was hypermethylated and expression was significantly down-regulated, this further disrupted Rb-mediated apoptotic activity[92]. Using a 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo-(-z-y1)-3,5-di-phenytetrazoliumromide (MTT) assay, one study explored down-regulation of the PTEN gene in the presence of the HCV Core gene, which in turn activated NF-kB and caused exponential cell growth[55]. Together this body of research highlights the essential role of HCV Core protein in the hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and its association with HCC progression.

NS3 and NS5a

-

Earlier serological studies showed significant down-regulation of p16 expression in the presence of antigens of the HCV proteins, NS3 and NS5, in patient serum samples[93]. Down-regulated p53 expression was observed when NS3 and NS5a were transfected in the hepatoma cell line[94]. Experiments conducted in HepG2 and Saos-2 cells showed that NS5a forms a complex with the p53 gene and, therefore, down-regulates p21 expression[84].

HCV NS5b is associated with the Rb gene of the host cell and down-regulates its expression[80]. It can be inferred from available data that the presence of HCV genes hinders p53 and Rb gene expression disrupting tumor suppressor gene expression. Table 2 summarizes the HCV genes responsible for down-regulating expression through epigenetic alteration of tumor suppressor gene promoters that have been studied, according to the best of our knowledge.

Table 2. HCV genes down-regulate tumor suppressor genes' expression in HCC.

HCV genes Tumor suppressor genes Function Refs Core P53[99], rb[99], p16[100], PTEN[55] By means of methylation, the aberration core affects the cell cycle. It hypermethylates the p16 promoter and mitigates its expression. P16 is suggested as a negative regulator of the G1 checkpoint that inactivates during HCC pathogenesis. [92] Core-mediated Rb phosphorylation that releases E2F1 and activates DNMT-1 which is mandatory for HCV infection. [101,102] HCV Core diminishes the activity of ATRA to upregulate p53 and apoptosis. [103] The core gene down-regulates the PTEN gene. [104] NS3 P21[105], p53[99] NS3 down-regulates p53 and p21. [94] NS5a PTEN[106], p53[99], p21[107] Down-regulated p53 expression was observed when NS3 and NS5a were transfected in hepatoma cell line. Experiments conducted in HepG2 and Saos-2 cells showed that NS5a forms a complex with the p53 gene and, therefore, down-regulates p21 expression. [94,108] NS5a down-regulates PTEN and inhibits the PI3K-Akt pathway. [106] NS5b Rb[106] HCV NS5b associates with Rb gene of the host cell and down-regulates its expression [80] ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers, such as SWI/SNF complexes, are prevented from recruiting and activating by HCV Core and NS5A proteins[95,96]. The hypermethylation and silencing of tumor suppressor genes result from chromatin compaction caused by the loss of function of these complexes. Hepatocellular carcinoma result from epigenetic changes that facilitate carcinogenic pathways[97]. Receptively, these epigenetic modifications persist as 'epigenetic memory' following virus eradication, as evidenced by hypercohesion and elevated HCC risk. This suggests that HCV has long-term effects on chromatin[98].

-

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) participate in several biological functions, including transcription regulation and RNA processing. Dysregulation of RBPs can affect the expression of tumor-promoting genes, accelerating cancer growth[109]. The interaction between (RBPs) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is significant in HCV infection. RBPs, such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), are critical for chromatin organization, and transcriptional control[109]. HCV infection can activate certain RBPs, which may interact with DNMTs to increase methylation at tumor suppressor gene promoters and cause HCC[110].

-

Specific Repetitive Elements (REs) methylation is lost during HCV infection. This process can lead to the development of liver cancer[111]. Res, including long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1) and Alu element (Alu), promotes HCC development[112]. LINE-1 and Alu are found abundantly within the genome. They can mobilize in the human genome, which leads to genetic instability[111,112] and contribute to cancer development[113]. Genomic integrity is maintained by DNA methylation of Res[114]. Thus, RE hypomethylation allows them to mobilize within the genome and lead to HCC development[111]. It has been shown that during HCV infection, certain Res (LINE-1) are hypermethylated that initiate the process of HCC[111].

-

Cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and apoptosis are controlled by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway[115]. The binding of the Wnt ligand to the low-density-lipoprotein-related protein 5/6 co-receptor complex initiates β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation. This canonical pathway activates target genes c-Myc and cyclin D1[116]. Epigenetic changes can result in improper activation of the Wnt pathway and promote cancer development[117]. Wnt extracellular antagonist, secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs), has an N-terminal cysteine-rich domain that can block Wnt–receptor interactions and obstruct Wnt signaling[118]. HCC cells expressed high levels of Dnmt1, HDAC1, and methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins that bind near the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the SFRP1 gene. When Dnmt1 was knocked down, HCV Core-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) was inhibited and obstructed Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Hypermethylation of the SRFP1 promoter induces EMT during HCV infection and leads to HCC progression[119].

-

DNA methylation process involves the methyl group donor, S-adenosyl methionine, and Dnmt (1, 3a, 3b) enzymes that transfer the methyl group to DNA. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes was observed in several cases of cancer where Dnmt enzymes were over-expressed[120]. Dnmt1 has been reported to hypermethylated the tumor suppressor genes E-cadherin[121], PARP-1[101], and GSTP1[122]. Using a Huh7 cell model, it was found that Dnmt1 is over-expressed in cells transfected with the HCV-Core gene, leading to epigenetic silencing of SFRP-1. Knockdown of Dnmt1 restored SFRP-1 expression[116].

Epigenetic changes induced by HCV are inherited by their daughter hepatocytes that ultimately lead to the development of HCC. The many epigenetic alterations that change gene expression are also inheritable to future generations. Methylation of chromosomes 3 and 16 has been observed in hepatocarcinogenesis in regions that suppress tumor suppressor genes RASSF1A, BLU, and FHIT[123]. Alterations in miRNA expression that target methyltransferases and hypermethylation of INK4a and INK4b tumor suppressor genes also influence hepatocarcinogenesis[123]. Epigenetic changes during HCC have been reported in the Ras/Raf/MAPK, and mTOR pathways. Methylation-associated epigenetic changes are observed in G-protein receptor signaling[124].

-

Few patients with acute HCV infection successfully clear the virus from the body. Often, patients with a chronic infection develop HCC[125]. HCV induces epigenetic alteration in the host genome. During HCV infection, HCV pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) activate the toll-like receptor (TLRs), and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) pathways, which stimulate Interferon (IFN) type I signaling[126]. HCV infection triggers the secretion of interleukins (IL) and activates inflammasomes. Liver cells infected with HCV activate macrophages that produce NALP3 inflammasomes and IL-8. This molecular mechanism activates natural killer cells (NK) of the disease, the host body fails to fight against the HCV infection, and immune factors (IFN signaling, activation of NF-κB, TNF-α, and IL-6) become dysregulating to the development of HCC[127]. T-cells become exhausted, meaning they lose their functionality and show increased expression of inhibitory receptors such as programmed cell death 1 (PD-1). It has been reported that high PD-1 expression can persist even after direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy[128,129]. This may be due to epigenetic alterations resulting from chronic HCV infection that contribute to the progression of liver cancer.

Hepatocyte apoptosis is affected by HCV Core protein. Thus, H2O2 upregulates p14 expression that degrades MDM2 in the proteasome. This stabilizes p53. Core hypermethylates the promoter of p14 and inhibits its expression, which in turn hinders p53 by MDM2[54]. Thus, p14 and p53 inhibition lead to HCC progression. The repressed p14 stops the function of trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) that prevents hepatocyte apoptosis. ATRA hypomethylates the promoter of p14 that activates the p53-dependent apoptotic pathway. HCV Core diminishes the activity of ATRA to upregulate p53 and apoptosis. Core mediates increased expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B that hypomethylate the p14 promoter[130] of using methylation aberration core affects the cell cycle. It hypermethylates the p16 promoter and mitigates its expression. P16 is suggested as a negative regulator of the G1 checkpoint that inactivates during HCC pathogenesis[92].

HCV-induced DNA methylation leads to DNA damage and cell cycle arrest. The Gadd45 gene family encodes the Gadd45β protein that repairs DNA excision. During genotoxic stress, this protein inhibits G2/M progression due to HCV-mediated promoter hypermethylation of the Gadd45 gene. Higgs et al. observed the down-regulation of Gadd45β in HCV-infected cells. Moreover, a noticeable decrease in Gadd45β expression was observed in liver biopsies of HCV patients and non-tumoral tissues from transgenic mouse models[131]. There exist two unique mechanisms that govern the Core-mediated up-regulation of DNMT expression. Park et al. suggested that intracellular transducers (ERK1/2, JNKs, and p38 MAP kinases) play a role in core mediated activation of AP-1 expression and DNMT-1 promoter that has binding motifs of the AP-1 complex. JNK inhibitor reduced the expression of DNMT-1 in core-expressing cells[92]. Arora et al. suggested another mechanism that showed stimulation of the Rb-E2F pathway by core-mediated Rb phosphorylation that releases E2F1 and activates DNMT-1[101]. mRNA and protein expression levels of DNMT-1 and DNMT-3B are different in different HCV genotypes[91]. DNMT-1 and DNMT-3B are essential for HCV infection, RNA synthesis[132], and its expression.

Core hypermethylates and represses E6-associated protein (E6AP) and evades poly-ubiquitination by E6AP and its proteasomal degradation[103]. Promoter methylation of SPINT2/HAI-2 was found in HCC patients. Hypermethylation of SPINT2/HAI-2 inhibits the HGF activator enzyme and the HGF/c-Met receptor pathway. Thus, down-regulates a urokinase plasminogen activator that degrades extracellular matrix, migration, and metastasis. HCV-mediated aberrated methylation leads to inflammation and ROS generation in HCV-infected cells[27]. Another tumor suppressor gene, RASSF1A, was reported to be hypermethylated during HCC progression. IFNγ expression increased in HCV-infected mice. Natural killer (NK) cells express IFNγ, and NK cell inhibitor reduces its expression. Thus, the function of NK cells in HCV-infected mice induces DNA methylation[133]. Global DNA methylation in enhancers containing binding sites of FOXA1, FOXA2, and HNF4A, was observed in liver biopsies from HCV-infected patients. Nishida et al. observed that persistent HCV infection increased methylation in CpG loci. Thus, the aberrated methylation profile of HCC patients leads to HCC progression[134]. All the suggested pathways reflect the involvement of epigenetics in the immune system.

-

Tumor recurrence in patients treated with DAAs has been reported by various epidemiological studies. In vitro, HCV infection models showed persistent epigenetic signatures even after the removal of the virus by DAAs treatment. Eight gene signatures have been persistently reported in HCV-infected and post-SVR liver biopsies[135]. Cytoskeleton remodeling pathways are epigenetically altered during HCV infection. These pathways are involved in the invasion and metastasis of tumorous cells[135]. This epigenetic scarring persists within the genome even after DAAs-mediated HCV eradication[135]. Recent research has shown that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor drug, Erlotinib, inhibits the epigenetic-inducing enzymes and reverses the epigenetic signature in vitro[135]. Potentially, such drugs can be employed to diminish HCV-induced epigenetic signatures from the genome to decrease the risk of liver cancer[135].

Clinically, long-lasting effects are required, it reprograms the epigenetic changes to fight chronic diseases. Therefore, sustained effects cannot be expected if one epigenetic enzyme is targeted to use epigenetic editing, several epigenetic 'writers and erasers' could be targeted. Treatments should be done in a way that guarantees the persistence of these effects over several cell replications[136].

-

Worldwide, the commonly consumed epigenetic regulators include flavonoids. Flavonoids are strong cancer inhibitors, as they have been proven in different studies. They restore dysfunctional epigenetics and intervene in DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA expression. Flavonoids always showed significant efficacy either used alone or in adjuvant therapy[137]. The efficacy of flavonoids is unchallengeable. While flavonoids produce anti-cancerous effects through multiple mechanisms, they can simultaneously cause problems for drug administration. Efficacy and results may vary while modulating epigenetic aberrations, and this is quite common[137]. Insufficient bioavailability is the main hindrance to its clinical application. The researchers now have begun to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of flavonoids by using them in adjuvant therapy (other plant compounds, Nano-drug carrier system). By blocking DNMTs and histone-modifying enzymes, natural substances—in particular, flavonoids like quercetin, genistein, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) from green tea—have demonstrated potential in restoring epigenetic changes in HCC[138]. These substances trigger apoptosis, control the cell cycle, and support anti-cancer pathways. Furthermore, it has been shown that curcumin and resveratrol can change the methylation state of tumor suppressor genes such as RASSF1A, which slows the growth of HCC[139]. The effectiveness of treatment may be further increased by combining flavonoids with synthetic medications, especially when it comes to addressing preneoplastic cells[140].

-

It has been noted that various protein targets respond to epigenetic modifiers such as HMTs, KDMs, and HDACs. Depending upon different target genes of the same cell, the epigenetic modulator, G9a/KMT1C, can act as a coactivator or a corepressor[141]. EZH2/KMT6 epigenetic modulator can also inhibit or activate gene expression depending on the tumor type when over-expressed[142]. Pathophysiological implications are better understood while monitoring the whole impact of the epigenetic machinery. Advanced epi-drugs, such as DNMT inhibitors like guadecitabine, which demethylates hypermethylated tumor suppressor genes like CDKN2A and SOCS1, and HDAC inhibitors, which encourage gene reactivation through increased histone acetylation, are the mainstay of therapeutic strategies to reverse HCV-induced epigenetic changes[143]. With ongoing clinical trials examining their effectiveness across different cancer types, combining these medicines suggests synergistic promise in reactivating suppressed genes and enhancing outcomes in HCV-related HCC[144]. Advancements in scientific research have revealed promising inhibitors of epigenetic modifiers. Recent data shows that these inhibitors do not antagonize the modifiers but bind to the enzymes that regulate the epigenome (Table 3).

Table 3. HCV-induced epigenetic changes can be inhibited by epigenetic modifiers inhibitors. These inhibitors and their modifiers are given in the table.

Epigenetic modifiers Description Inhibitors of modifiers Ref. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) HCV infection activates EGFR that epigenetically modify cytoskeleton remodeling Erlotinib [107] Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) HCV genome induces UPR. UPR inhibitor has been reported to partially recover the dysregulated gene expression. UPR inhibitor [107] Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) pathway LPA initiates the HCC-inducing pathways. The efficacy of the inhibitors was observed in the diethylnitrosamine (DEN) rat model. These inhibitors suppress Rho and ERK pathways. ATX (AM063), LPAR1 (AM095) [107] -

Epigenetic changes in the promoters of tumor suppressor genes progress with the advancement of liver disease associated with HCV infection. Since epigenetic modifications are reversible by nature, it is an attractive area for epi-drug development. Thus, understanding the mechanism behind specific HCV genes that promote the development of cancer may open new horizons for the treatment of HCC patients. This review is an effort to summarize data on the promoter methylation status of tumor suppressor genes in the presence of HCV-induced HCC. This review focuses on discoveries about how hepatitis C virus (HCV) genes affect epigenetic modifications and HCC. The effect of NS5a on histone modifications, which change chromatin structure and silence tumor suppressor genes, and the function of the HCV Core protein in causing DNA methylation, which silences important regulatory genes including p16, p53, and PTEN, are remarkable results. Additionally, even after viral clearance, residual epigenetic scars following HCV treatment, such as hypermethylation and histone alterations, point to a risk of HCC recurrence. Additionally, the study compiles evidence of extensive hypermethylation across tumor suppressor genes, including CDKN2A/B, SOCS1, and EFEMP1, which impacts pathways essential for apoptosis and cell cycle regulation. These results highlight the necessity of long-term post-treatment monitoring and the promise of designed epigenetic therapy.

Future perspectives

-

Focusing on HCV-induced epigenetic changes in tumor suppressor genes during HCC development may prove to help design potent epi-drugs. It may aid in devising strategies that can undo these modifications in the promoters of tumor suppressor genes and allow the normal cell cycle to continue. Certain HCV genes could be targeted to disrupt their function, thus allowing the tumor suppressor genes to function properly. Additional tumor suppressor genes should be examined in HCV-induced HCC tissue samples. Further studies should concentrate on improving tumor suppressor gene methylation patterns as non-invasive biomarkers for early HCC identification, with a particular emphasis on integration with multi-omics techniques and liquid biopsy technologies. The diagnostic and prognostic value of markers such NORE1A, RASSF1A, SPINT2, CDKN2A (p16), APC, SOCS1, and EFEMP1 should be investigated.

The accuracy of diagnosis may be improved by looking into population-specific methylation patterns and how they interact with environmental and genetic factors. Furthermore, these methylation markers may be combined with newly developed protein panels and epi-drug response monitoring to produce all-inclusive tools for individualized HCC screening and prognosis.

-

Approximately 58 million people worldwide are infected with HCV. Scientists rarely focus on HCV-induced HCC that can involve epigenetic modifications to tumor suppressor genes and their expression. To date, there is only a minute amount of data regarding the epigenetic profile of HCV-induced HCC. Researchers historically explored epigenetic profiles of HCC irrespective of its cause (alcohol consumption, HCV, HBV, or any other environmental factors). The literature referenced in this review shows that more studies are needed to focus on the HCV-induced epigenetic changes in tumor suppressor genes to decipher the mechanisms underlying the development of HCC. EFEMP1, SPINT1, Rb, p53, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDH1, GSTP1, SOCS1, APC, p27 p16, p14, and p15 are tumor suppressor genes that have been found to have hypermethylated promoters during HCV-induced HCC. The methylation profiles of these promoters can potentially be used as early detection biomarkers for reducing deaths from HCC. HCV-NS3a, HCV-NS5a, and HCV-Core have been reported to down-regulate p53, p16, p21, PTEN, and Rb genes in different cell lines. Thus, furthering the concept that HCV-induced hypermethylation and silencing of tumor suppressor genes promote HCC development. The impacts of these findings are extensive. Because HCV-induced epigenetic changes are reversible, they are desirable targets for therapeutic intervention. In addition to understanding the molecular processes underlying the development of HCC, methylation patterns of tumour suppressor gene promoters serve as a basis for the creation of innovative epigenetic treatments. Drugs that target histone-modifying enzymes and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) may be able to stop the spread of tumors and restore normal gene expression. Furthermore, non-invasive screening and monitoring of HCV-associated HCC may be made possible by detecting hypermethylation patterns in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Afzal S; draft manuscript preparation: Aftab A; data acquisition, figures and tables preparation: Naveed H, Idrees H; manuscript review: Ali L, Idrees M, Afazal S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Aftab A, Naveed H, Idrees H, Ali L, Idrees M, et al. 2025. The emerging role of epigenetics (DNA methylation) in hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointestinal Tumors 12: e009 doi: 10.48130/git-0025-0007

The emerging role of epigenetics (DNA methylation) in hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma

- Received: 25 November 2024

- Revised: 29 January 2025

- Accepted: 11 March 2025

- Published online: 07 May 2025

Abstract: Epigenetics has enthralled humanity as a form of genetic alteration that may underlie different human cancers. Among these cancers, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a threatening disease and one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. This review attempts to summarize the scientific work examining the hypermethylation of promoters for tumor suppressor genes to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and the development of HCC. Data shows that the development of HCC is a multistep phenomenon where varying promoter methylation profiles can be observed. Moreover, HCV-mediated HCC has been linked to hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes. Evidence suggests that HCV Core, NS3, NS4b, and NS5a can potentially inhibit tumor suppressor genes. Therefore, HCV genes disrupt the function of host tumor suppressor genes by inducing epigenetic modifications that result in tumor progression.

-

Key words:

- Hepatitis C virus /

- Tumor suppressor /

- Hepatic /

- liver /

- Epigenesis /

- Methylation /

- Gene expression