-

The Spondias tuberosa Arruda Câmara species, known as umbu tree, belongs to the Anacardiaceae family. This family is represented by nine fruitful species in Brazil with great bioactive potential[1] and possible technological, and commercial applications[2]. Among these species, umbu and cajá (Spondias mombin) are particularly noteworthy for their high nutritional value and versatility in product development[3].

Endemic to Brazil, the umbu tree is predominantly distributed across the Brazilian semiarid region, particularly within the Caatinga biome[4], where it is found in both native areas and agroforestry systems. The Caatinga covers approximately 862,818 km², accounting for about 10% of Brazil's territory and 86% of the semiarid region, being the only biome exclusively Brazilian[5]. This region encompasses northeastern states such as Bahia, Pernambuco, and Ceará, as well as northern Minas Gerais.

In response to the low precipitation conditions characteristic of the region, the umbu tree exhibits remarkable morphological and physiological adaptations that ensure its survival. These include specialized root systems capable of water storage[6], waxy cuticles that reduce water loss, and the senescence of leaves during the dry season[7]. These adaptive strategies make the umbu tree not only a symbol of resilience but also a crucial element for maintaining the ecosystem services of the Caatinga. By providing food and shelter for local fauna and contributing to soil stabilization, the umbu tree plays an indispensable role in environmental preservation and the balance of the biome[8].

The socioeconomic significance of the umbu tree is profound. The fruit serves as a vital source of income for rural communities, particularly during the harvest season[9]. Through local sales and regional markets, umbu fruit not only contributes to enhancing food security but also bolsters economic resilience in a region often impacted by unpredictable climate patterns. Umbu-derived products are consumed in various regions of Brazil, although fresh fruits are primarily marketed within their region of origin. The main processed products include pulp, sweets, jams, and other items[10], which have the potential for expansion into international markets, although exports remain in their early stages[4].

One of the most notable aspects of the umbu tree is the genetic diversity present in its natural populations[11]. Variations in fruit size, shape, texture, and chemical composition[12,13] offer extensive opportunities for selective breeding. These variations can be leveraged to enhance desirable traits such as productivity, disease resistance, and nutritional content.

Moreover, these natural populations represent a significant genetic resource that can be utilized not only for agricultural purposes but also to preserve the species' genetic diversity and ensure its long-term viability. The umbu's tree role as both an agricultural asset and a means of biodiversity conservation emphasizes its fundamental importance to the region's sustainability.

In this context, this study aims to study the examine and variability of fruits from different accessions of the umbu tree, within the same population in the territory of Western Cariri in Paraiba (Brazil), through physical, chemical, and physicochemical analyses.

-

The studied fruits were harvested from 14 accessions located in the Serra do Jatobá region in Serra Branca, Paraíba, Brazil, a municipality located in the territory of Western Cariri in Paraíba, Brazil (07º29'00" S, 36º39'54" W, altitude - 493 m).

Approximately 160 hectares were covered and the accessions were selected, in the field, based on apparent characteristics, such as size, shape, and hairiness. In addition, all were previously identified and georeferenced with the aid of a GPS (Garmin Etrex 10) (Fig. 1), where the greatest distance found between individuals (3.65 km) was related to accessions 3 and 14, and the closest distance was between accessions 12 and 13 (35 m).

The fruits were manually harvested between 6 and 10 am from the entire length of the crowns and visually selected based on commercial maturity, referred to by Campos[14] as 'almost ripe' (onset of pigmentation), using peel coloration and apparent firmness as indicators. After harvesting, the fruits were placed in plastic bags, labeled, and transported in styrofoam boxes to the Post-Harvest Physiology Laboratory at the Center for Human, Social, and Agrarian Sciences (CCHSA), Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), Brazil. At the laboratory, they were sanitized in a chlorine solution (100 ppm), classified for uniformity in size, and inspected to ensure the absence of mechanical injuries or signs of disease.

Due to the low population density of the studied area and the variable availability of fruits, each accession was represented by a single mother tree. The sampling consisted of 100 fruits per tree, from which 25 processed and homogenized fruits formed the experimental units for physicochemical and chemical analyses. However, before this processing, the physical characterization of the fruits from each experimental unit was carried out.

Physical evaluations

-

The weight of the fruit (g), the peel, and the seed were determined by individually weighing each fruit on a semi-analytical scale (Bel Engineering, S203H); the longitudinal and transverse diameters (cm) were measured with the aid of a caliper, and from their ratio, the shape of the fruit was obtained.

Firmness was measured using a digital penetrometer (Instrutherm model PTR-300) with a 3 mm tip (5–200 ± 1 N) inserted in the equatorial region of the fruits, with results expressed in Newton.

To obtain the yield, the edible parts of the fruit (peel and pulp) were considered. Thus, the fruits were manually peeled with the aid of a stainless-steel knife to obtain the mass of the peel, seed, and pulp, expressed as a percentage in relation to the whole fruit. Then, the yield was determined from the sum of the percentages of peel and pulp.

Physicochemical evaluations

-

Soluble solids (SS) were determined using a handheld digital refractometer, with results expressed in degrees Brix (°Brix), according to standardized techniques[15].

The titratable acidity (TA) was obtained according to the methodology recommended by IAL[15], which used 5 g of homogenized pulp diluted in 100 mL of distilled water, followed by titration with a standardized solution of 0.1 N NaOH, having as an indicator the phenolphthalein turning point. The results were expressed in g of citric acid per 100 g of the sample. Subsequently, the SS/TA ratio was calculated.

The potential of hydrogen (pH) was obtained through a benchtop pH meter by direct reading in the homogenized pulp, according to IAL[15].

Chemical evaluations

-

Vitamin C was determined by the Tillman's method[16], in which 1 g of the sample was weighed and transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask, where the volume was completed to 50 mL, with 0.5% oxalic acid, and titration was performed with a Tillman's solution until reaching the turning point. The results were expressed in mg of ascorbic acid per 100 g of the sample.

Sugars were determined using the Lane-Eynon method, which involves titration with Fehling's reagent[15]. This approach quantified reducing and total sugars, while non-reducing sugars were calculated by difference, and the results were expressed as a percentage. In addition, the percentages of moisture and ashes were obtained using a gravimetric technique by weighing 5 g of the sample, previously submitted to an oven for 24 h at 105 °C and, subsequently, to a muffle at 550 °C (methods 012/IV and 018/ IV)[15].

The normality of the obtained data was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which was met for all evaluated variables. The studied traits were then analyzed using the Scott–Knott cluster test of means at 1% significance, conducted with RStudio software version 3 (2009–2019 RStudio, Inc.). Pearson correlation and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed using OriginPro 2024 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Pearson correlation was applied to assess the strength and direction of linear relationships between physical and physicochemical traits, identifying potential associations among variables[17]. PCA was conducted to reduce data dimensionality, reveal the main sources of variability, and classify different accessions based on their distinguishing characteristics[18].

-

In terms of fruit mass, the treatments were grouped into six distinct categories based on average values. Among these, accessions 1, 2, and 6 produced the smallest fruits, whereas accessions 4, 8, and 13 exhibited the highest fruit weights, ranging from 24 to 24.51 g (Table 1).

Table 1. Physical characteristics of umbu accessions.

Accessions Mass Peel Seed Pulp Yield 1 13.21f 16.59b 9.83d 73.25c 89.85b 2 12.87f 13.85c 11.54c 74.58c 88.43b 3 16.61e 20.06a 15.75a 64.86d 84.92c 4 24.42a 10.28d 8.30e 81.36a 91.64a 5 16.46e 13.19c 9.53d 77.74b 90.94a 6 13.81f 13.88c 10.88c 75.15c 89.04b 7 18.30d 11.87d 7.07e 80.94a 92.82a 8 24.00a 10.33d 8.49e 80.62a 90.96a 9 15.58e 9.84d 7.68e 82.17a 92.01a 10 19.54c 10.15d 8.74e 80.73a 90.88a 11 21.60b 10.52d 10.98c 77.93b 88.45b 12 21.74b 10.76d 9.63d 79.34b 90.10b 13 24.51a 9.87d 8.07e 81.80a 91.68a 14 18.75d 11.12d 14.02b 73.65c 84.77c Average 18.67 12.31 10.04 77.44 89.75 CV (%) 4.81 9.25 5.70 1.78 1.03 p-value < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 Mass (g), peel (%), seed (%), pulp (%), yield (% peel + % pulp). CV (%): coefficient of variation. Averages in the same column with distinct letters differ from each other by the Scott–Knott test with p < 0.001. The percentage of peel varied from 9.84% (accession 9) to 20.06% (accession 3), with an average value of 12.31% (Table 1). Most accessions showed no significant statistical differences and exhibited values below the average.

Accessions 3 and 14 exhibited the highest seed percentages, at 15.75% and 14.02%, respectively, while the lowest value was observed in accession 7, at 7.07%. Most accessions had seed percentages below the average of 10.04%. Accessions 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 13 demonstrated the lowest seed-to-fruit ratios, with no significant statistical differences among them (Table 1). Nine accessions had pulp percentages exceeding the average value of 77.44%, with accessions 4, 9, and 13 standing out, surpassing 81%.

The fruit yield averaged 89.75%, ranging from 84.77% (accession 14) to 92.82% (accession 7). Notably, accessions 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 achieved yields exceeding 90% (Table 1). Accession 3, in addition to exhibiting the lowest pulp percentage, also had the highest seed percentage, rendering it one of the least suitable accessions for processing due to its lower yield. Similarly, accession 14 was also identified as less favorable for processing.

Accessions 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 13 exhibited lengths above the overall average of 3.05 cm, while the width ranged from 2.34 cm to 3.32 cm, with an overall average of 2.80 cm (Table 2).

Table 2. Physical dimensions and firmness of umbu accessions.

Accessions Length Width Shape Firmest 1 2.63e 2.51f 1.04c 30.10b 2 2.79d 2.34g 1.19a 23.13c 3 3.21b 2.66e 1.21a 29.91b 4 3.50a 3.32a 1.05c 30.27b 5 2.83d 2.65e 1.07c 25.10c 6 2.61e 2.57f 1.01d 20.23d 7 3.11c 2.73e 1.14b 28.69b 8 3.21b 3.14b 1.02d 27.43b 9 2.80d 2.58f 1.08c 24.55c 10 3.19b 2.85d 1.12b 30.51b 11 3.25b 2.97c 1.09c 25.26c 12 3.03c 3.01c 1.00d 35.36a 13 3.54a 3.04c 1.16b 25.13c 14 3.03c 2.81d 1.07c 31.22b Average 3.05 2.80 1.09 27.64 CV (%) 2.30 1.93 1.99 7.22 p-value < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 Length (cm), width (cm), firmest (N). CV (%): coefficient of variation. Averages in the same column with distinct letters differ from each other by the Scott–Knott test with p < 0.001. The shape of the studied fruits varied between spherical and oval, with a predominant tendency towards an oval shape. Accessions 12, 6, and 8 were similar and stood out for their uniform proportions, making them round, while accessions 3, 2, 13, and 7 were more elongated.

The fruits of accession 12 were the firmest, with a firmness of 35.36 N, while accession 6 exhibited the lowest firmness at 20.23 N. Overall, most accessions demonstrated firmness values above the average of 27.64 N, with accessions 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, and 14 showing no significant differences from one another.

Among the physicochemical quality attributes quantified (Tables 3 & 4), titratable acidity ranged from 0.86% (accessions 6, 11, and 13) to 1.72% (accession 4), with an average value of 1.14%.

Table 3. Physicochemical characteristics of umbu accessions.

Accessions TA pH SS SS/TA 1 1.28c 2.45a 9.03c 7.03c 2 1.08d 2.36a 8.00d 7.34c 3 1.08d 2.22b 8.00d 7.45c 4 1.72a 2.29b 9.00c 5.22d 5 0.99e 2.45a 8.13d 8.19b 6 0.86f 2.46a 8.00d 9.23a 7 1.43b 2.30b 12.93a 9.03a 8 1.26c 2.20b 10.00b 7.90c 9 0.99e 2.38a 9.16c 9.23a 10 1.14d 2.26b 9.03c 7.90c 11 0.86f 2.37a 8.36d 9.73a 12 1.00e 2.41a 9.36c 9.36a 13 0.90f 2.42a 6.60f 7.34c 14 1.33c 2.37a 7.56e 5.67d Average 1.14 2.35 8.80 7.90 CV (%) 4.99 2.37 2.31 5.74 p-value < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 TA: titratable acidity (g of citric acid 100 g−1), SS: soluble solids (°Brix). CV (%): coefficient of variation. Averages in the same column with distinct letters differ from each other by the Scott–Knott test with p < 0.001. Table 4. Physicochemical composition of umbu accessions.

Accessions Vit C RS NRS Moisture Ash 1 50.06a 3.31c 1.40d 89.27b 0.42a 2 36.97b 2.65d 1.31d 91.14a 0.38b 3 25.30e 2.68d 1.32d 89.79b 0.46a 4 36.99b 2.90d 1.71c 89.22b 0.43a 5 35.04c 3.44c 2.21b 90.80a 0.32c 6 37.69b 3.06c 2.68a 90.77a 0.26d 7 34.07c 3.76b 2.70a 85.57d 0.43a 8 32.88c 4.52a 2.03c 87.57c 0.35b 9 37.74b 3.11c 1.37d 88.09c 0.33c 10 31.97c 3.26c 2.62a 89.63b 0.28d 11 21.87e 2.71d 2.68a 91.00a 0.26d 12 25.08e 2.75d 3.07a 90.10b 0.25d 13 22.65e 2.57d 1.94c 91.17a 0.21d 14 28.99d 2.38d 1.68c 91.21a 0.35b Média 32.66 3.08 2.05 89.66 0.34 CV (%) 6.20 9.19 11.61 0.50 9.99 p-value < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 Vit C: vitamin C (mg of ascorbic acid 100 g−1), RS: reducing sugars (%), NRS: non-reducing sugars (%), Moisture (%), Ash (%). CV (%): coefficient of variation. Averages in the same column with distinct letters differ from each other by the Scott–Knott test with p < 0.001. In this regard, the pH ranged from 2.20 (accession 8) to 2.46 (accession 6), with an average of 2.35. Nine accessions exhibited similar pH values, all above the average.

Fruits with higher soluble solids content are generally more appreciated. Accessions 7 and 8 stood out, with soluble solids contents of 12.93 °Brix and 10.00 °Brix, respectively. The lowest value was observed in accession 13, with 6.60 °Brix. In terms of similarity, accessions 2, 3, 5, 6, and 11 showed no significant differences from one another, as did accessions 1, 4, 9, 10, and 12.

The SS/TA ratio ranged from 5.22 (accession 4) to 9.73 (accession 11), reflecting a significant variation of 46.35% between the maximum and minimum values, with an average of 7.90. Furthermore, accessions 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, and 13, as well as accessions 6, 7, 9, 11, and 12, showed similarities within their respective groups. These accessions were notable for having desirable SS contents above 9 °Brix.

The average content of vitamin C among the analyzed accessions was 32.26 mg·100 g−1 (Table 4). Accession 1 had the highest vitamin C content (50.06 mg·100 g−1) with 53.27% above the quantified average, and accessions 3, 11, 12, and 13 had the lowest values (21.87 mg·100 g−1 and 22.65 mg·100 g−1).

The reducing sugars (glucose and fructose) varied between 2.38% (accession 14) and 4.52% (accession 8), with an average of 3.08%, in which the majority presented lower content, however, during the maturation process these sugars tend to increase. Regarding non-reducing sugars (sucrose), the range was from 1.31% (accession 2) to 3.07% (accession 12) and an average of 2.05%. It was observed that accessions 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, and 13 had the lowest levels of reducing sugars, while accessions 1, 2, 3, and 9 exhibited a low proportion of non-reducing sugars (Table 4).

The average moisture content of the fruits was 89.66%. Among the accessions, moisture content ranged from 85.57% (accession 7) to 91.21% (accession 14), representing the smallest variation among the others studied. The ash content ranged from 0.21% (accession 3) to 0.46% (accession 13), with an average of 0.34%.

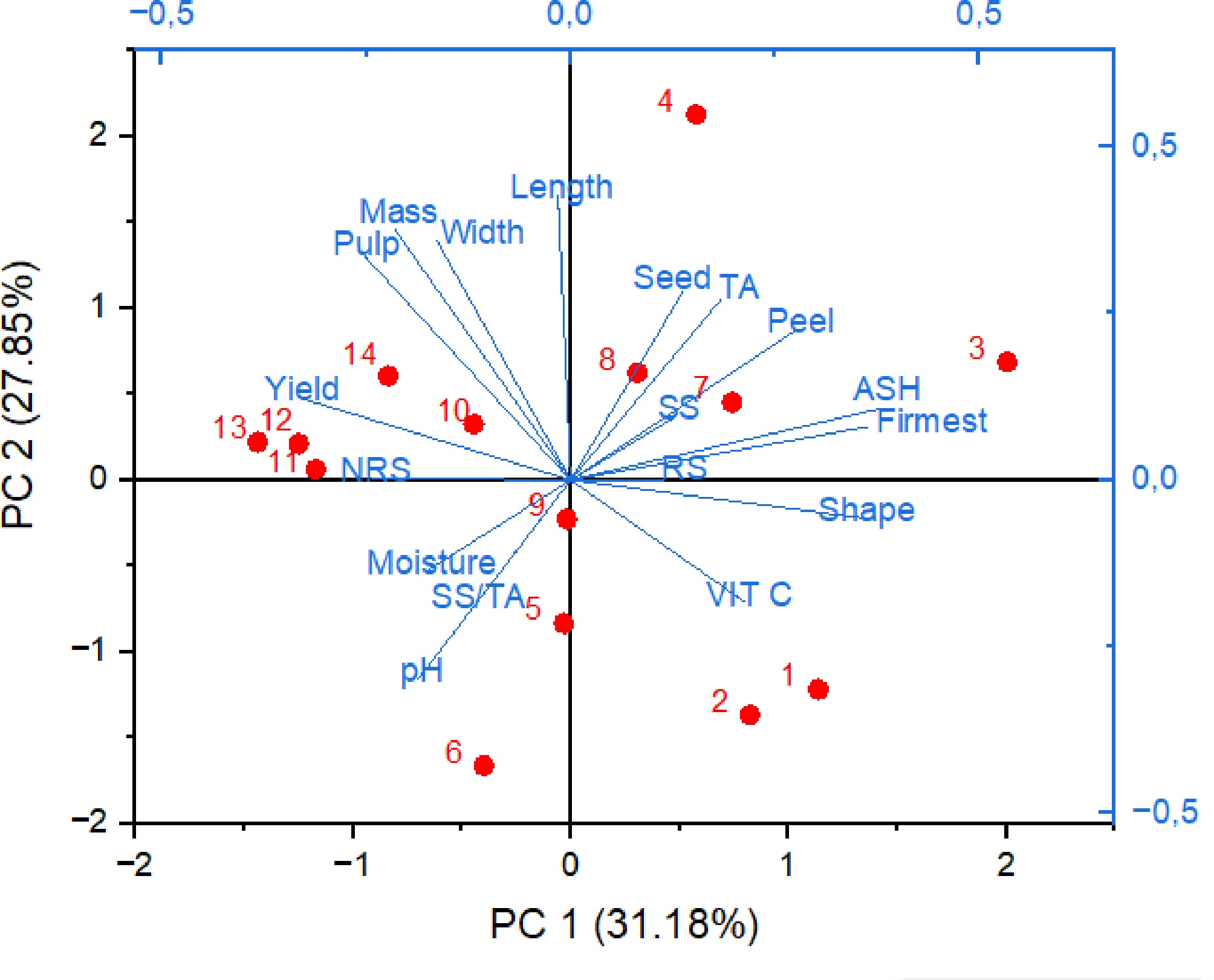

From the principal component analysis, the formation of three groups of variables was verified, responsible for 76.50% of the variability of the study. The main components number 1 (PC 1) accumulated 31.18% of the variability, attributed to the pulp percentage, fruit mass, yield, shape, width, ash content, firmness, and vitamin C; in turn, the main components number 2 (PC 2) accounted for about 27.85% of the variation between the different accessions, as a function of the fruit length, pH, titratable acidity, percentage of peel and seed; and the last one (PC 3), that was formed by soluble solids, reducing sugars and moisture, corresponded to 17.47% of the distinction between the fruits.

When evaluating Fig. 2, considering that the length of the vectors representing the studied characteristics (in blue) indicates their contribution and strength in the variability of the study, it is possible to observe, according to the eigenvalues, that length (0.428), ash (0.382), mass (0.377), firmness (0.364), width (0.360), shape (0.358), and pulp (0.341) were the most relevant parameters contributing to the variation among the accessions. In contrast, RS (0.114), SS (0.127), and NRS (−0.2437) exhibited the lowest influence.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the evaluated quality attributes of umbu accessions. Red points represent the different accessions, projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The blue vectors correspond to the quality attributes of the accessions that contribute to the formation of the principal components.

Regarding the distribution of the different accessions in the graph, Fig. 2 shows that accession 4 presented the greatest distinction between the different accessions, mainly attributed to the biometric characteristics. On the other hand, accessions 11, 12, and 13 formed a group due to their high similarity. Accessions 5 and 9 displayed significant physical and physicochemical similarities, as did accessions 7 and 8, which clustered together based on fruit proportion and similar SS values, a characteristic that conferred greater prominence to accession 7. Additionally, it is noteworthy that accession 3 exhibited the greatest distinction from the other fruits due to its ASH content, while accession 1 stood out for its vitamin C content.

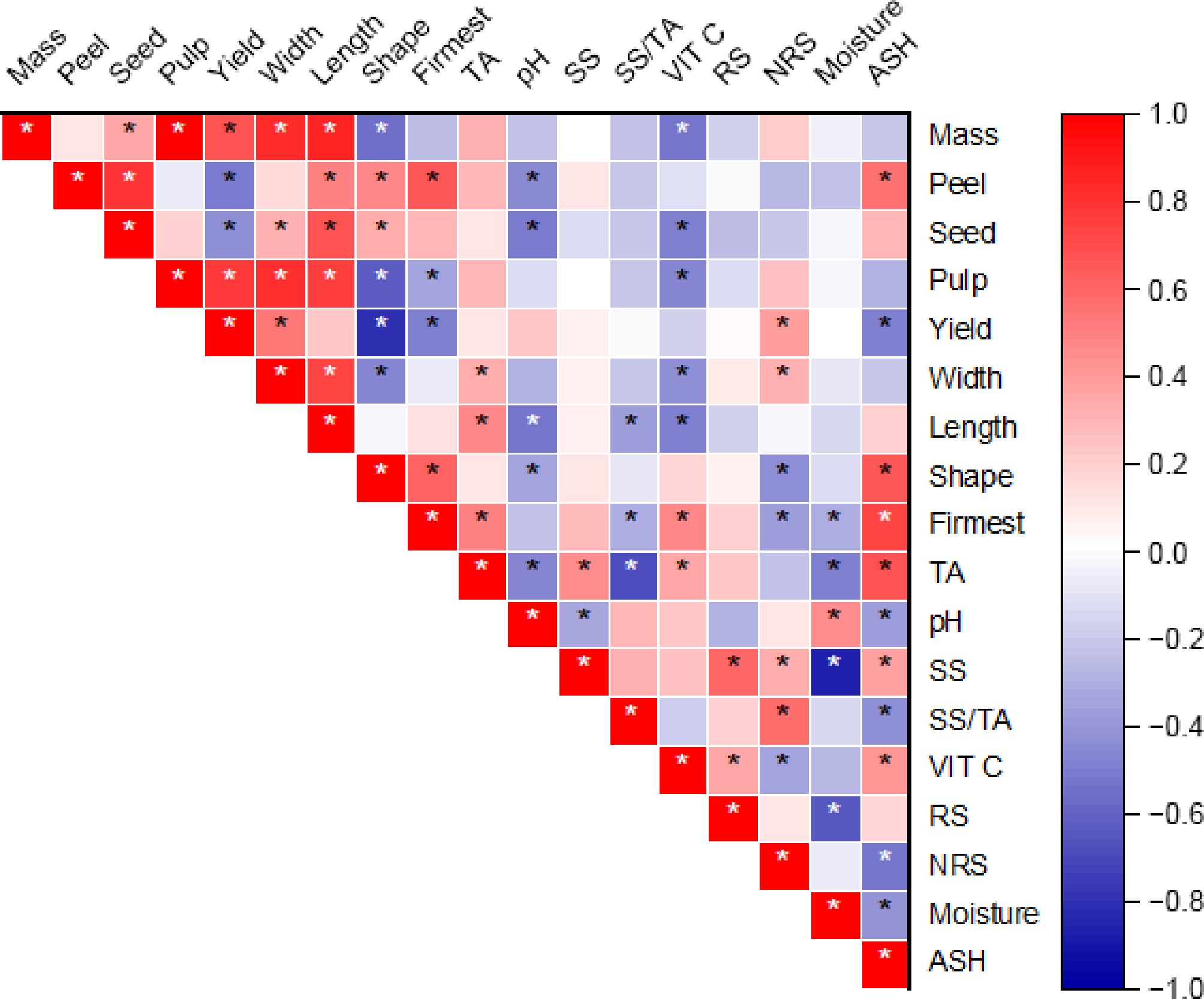

The correlation analysis revealed significant associations among the quality attributes of different umbu accessions, considering all evaluations together (Fig. 3). This approach aimed to identify common trends among the evaluated characteristics, regardless of the accessions, allowing for a broader understanding of general patterns that aid in fruit characterization and the comprehension of their physicochemical and biometric interrelationships.

Fruit mass was positively correlated with biometric traits such as seed, pulp, yield, width, length, and shape, reflecting the expected relationship between the fruit's physical size and its structural components. A positive correlation was observed between the proportion of pulp and yield. Fruits with a higher peel content exhibited elevated ash levels, suggesting a greater mineral concentration in the peel, a characteristic commonly observed in fruits. Less rounded fruits demonstrated higher yields, likely due to a higher proportion of usable pulp in these shapes. Greater yields were also associated with lower ash content, indicating that fruits with less peel (and more pulp) have a lower mineral concentration. Moisture content showed a positive correlation with yield, reflecting the contribution of the succulent pulp, and a negative correlation with acidity and firmness, behaviors typically associated with riper fruits or those with higher water content. Firmness exhibited a tendency for a direct correlation with peel quantity and ash content, likely due to the more rigid structure of the peel. Lastly, yield showed a negative correlation with peel and seed content, confirming that fruits with a higher proportion of these components yield less pulp.

-

Physical characteristics, such as weight and size, are used as quality attributes for selection and classification of products according to the convenience of the consumer market.

The average value obtained of mass in this study (18.67 g) corroborates with the study of Dantas Júnior[19] which presented an average value of 18.27 g, however, the largest fruits surpass the value of 23.78 g, as highlighted by Costa et al.[20] for fruits collected in the same municipality of this study. This reinforces that the umbu trees in the region produce fruits of desirable size, compared to other regions, within their diversity.

The fruit yield is obtained through the proportions between the peel, pulp, and seed, and the high pulp content is one of the most desirable characteristics, both for raw commercialization and for industrial purposes, as it is a fraction of the fruit of great economic interest[21].

In general, only accession 4 presented a percentage of peel above those reported by Dantas Júnior[19] of 17.22%, Costa et al.[20] of 17.54%, and Dutra et al.[22] of 22.79%. All fruits were in the almost ripe stage. During maturation, the proportion of peel decreases as the fruit grows[20,23].

The size of the seed directly influences the yield, so the most desirable aspect is that the proportion of the seed is small. In this sense, it is observed that the accessions that have the lowest seed percentage presented the highest yields, a characteristic of great commercial importance since both the industry and the consumer appreciate the high yield. Compared to other studies, the average value of pulp percentage was higher than those reported by Dantas Júnior[19] and Costa et al.[20], with 73.16% and 65.08%, respectively.

In the industrial processing of umbu pulp, especially in almost ripe fruits, the peel and pulp are homogenized together, with no influence of the peel thickness on the industrial yield in quantitative terms, although it may interfere with the final quality of the product[19]. An average value of around 90.38% was found by Dantas Júnior[19], referring to 32 umbu genotypes. However, Narain et al.[23] and Costa et al.[20] obtained lower yields of 83.91% and 82.62%, respectively.

The average length was close to that observed by Costa et al.[20] who reported an average length of 3.45 cm, however, the width was lower, with an average of 3.22 cm. Gondim[24] found an approximate size of 3.36 cm in length and 3.17 cm in width.

The shape of the studied fruits varied between spherical and oval, but with a more oval tendency. This parameter consists of a visual characteristic of great importance to the consumer and as a quality parameter in the industry for classification. Furthermore, processing machines are normally suited to handle of specific proportion.

Firm fruits favor their handling and conservation, and it is important to emphasize that the studied maturation stage is almost ripe, so the tendency is that, throughout the maturation process, the fruits lose firmness due to chemical and structural changes, as verified by Teodosio et al.[25] during the storage of umbu fruit. In addition, firmness is one of the most variable traits of umbu fruit, ranging from 4 N to 80 N[26], depending on different conditions from the maturation stage to harvesting.

In general, based on the physical characteristics mentioned, it is considered that accessions 4, 7, 8, and 13 stand out because they contain a group of desirable attributes, such as high mass, small seed, high yield, and above-average firmness. On the other hand, accession 3 presented lower mass, protuberant seed, low yield, and non-uniform shape (oval).

With an average value of 1.14%, for titratable acidity close to that found by Dantas Júnior[19] of 1.25%, accessions 1, 4, 7, 8, and 14 stood out, with acidity above the obtained average. When studying fruits at the same maturation stage, Costa et al.[27] found acidity higher than the highest value found in this study, 1.87% for fruits considered sweet and 2.27% for acidic fruits. It is worth mentioning that a TA value above 1% is of greater interest to the agro industry, because it reduces the amount of citric acid added in the pulp standardization process and microbiological control[24], however, sensorially it may not be such a favorable attribute, depending on the balance with soluble solids.

Although pH and titratable acidity have a high correlation, the same variation between treatments was not observed; the pH varied less than the acidity itself (2.20–2.35), which may occur due to some substances with buffering power[19]. Narain et al.[23] observed a pH value above 3.00 for almost-ripe fruits, however, Costa et al.[27] and Lima et al.[28] reported pH values of 2.22 and 2.16 respectively; closer to those obtained in this study.

The soluble solids content refers to the solids that are dissolved in the juice or pulp of the fruits and are constituted mainly by sugars[21]. The average value among the studied accessions was 8.80 °Brix, which is similar to the 8.90 °Brix found by Narain et al.[23] and is close to the 9.1 °Brix quantified by Campos[14] for almost ripe fruits. The soluble solids content is one of the physiological events most directly related to maturation, which tends to increase throughout this process, reaching maximum values of 14.3 °Brix[25], depending on the genotype and specific conditions.

The SS/TA ratio indicates the degree of sweetness, the predominant flavor between sweet and sour, and whether there is a balance between them. As they are almost ripe fruits, the SS/TA ratio should increase during maturation, due to the increase in soluble solids and decrease in titratable acidity. In this context, depending on the studied maturation stage, it is normal to present a more acidic characteristic. Narain et al.[23], Moura et al.[29], and Teodosio et al.[25] reported for ripe fruit, values of 10.73, 12, and 8 respectively. In addition, Dantas Júnior[19] observed high variability between different genotypes with a range from 4.89 to 11.89 for almost ripe fruits.

The amount of vitamin C is considered to be a high value when compared to other studies carried out with fruits from different states of Brazil: Pernambuco and Bahia by Campos[14] (24.2 mg·100 g−1), Paraiba by Gondim[24] (6.16 mg·100 g−1 to 14.52 mg·100 g−1), and Paraiba by Narain et al.[23] (15.9 mg·100 g−1). Contents above 50 mg·100 g−1 were only reported by Dantas Júnior[19], for fruits related to superior genotypes from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation active germplasm bank.

These variations in vitamin C content may be influenced by factors such as environmental conditions, soil composition, and genetic diversity among accessions, highlighting the importance of exploring these elements further. The data presented in this study significantly contribute to the understanding of the nutritional quality of umbu, emphasizing the need for complementary research to deepen knowledge of regional variables and their impact on the fruit's nutritional profile.

Although all were collected at the same maturation stage, accessions 1, 2, 3, and 4 showed an earlier development cycle; they were harvested about 20 d before the other which may explain the lowest levels of reducing and non-reducing sugars. This can be justified by considering metabolic and genetic factors related to fruit development[30]. Fruits with a shorter cycle have a reduced time for the transport and accumulation of carbohydrates from the leaves to the fruit, which may result in lower sugar reserves compared to longer-cycle fruits.

Furthermore, short-cycle fruits may exhibit a higher respiratory rate during the ripening process, consuming a significant amount of the accumulated sugars, which contributes to the lower final sugar content[31]. Finally, genetic variations within the same species, associated with hormonal regulation, can influence the developmental cycle and the ability to synthesize sugars[30], resulting in early-ripening fruits with distinct characteristics, even under similar environmental conditions.

The average moisture value of the fruits (89.66%) was considered high when compared to values found by Narain et al.[23] and Rufino et al.[32], 87.81% and 87.9%, respectively. The average of ash (0.34%) is equivalent to that quantified by Narain et al.[23] (0.3 g·100 g−1); accessions 1, 3, 4, and 7 stood out. This parameter tends to vary according to soil type and composition, which may explain the similarity between accessions 10, 11, 12, and 13, which were the most closely located accessions. In addition, it may indicate a high mineral content, a variable not commonly evaluated in these fruits.

The inverse relationship between ash content and yield indicates that fruits with less peel, although edible, offer a higher yield of usable pulp. Fruit firmness, associated with peel quantity, influences its texture and durability, directly impacting its market acceptance and processing suitability. Furthermore, fruit shape, particularly less rounded fruits, was correlated with a higher yield. While these fruits may be more irregular for harvesting, this association can be useful in the selection of accessions that maximize pulp yield, serving as a criterion for improving productivity. These findings are essential for fruit selection strategies, aiming to optimize both yield and quality for consumption and processing.

The significant variability observed among the 14 accessions of umbu highlights its potential for targeted selection and genetic improvement, aimed at enhancing fruit characteristics for different market segments. Accessions with high vitamin C content, such as accession 1, show promise for nutritional enrichment in fresh consumption and the development of functional foods, while those with higher mass and yield, such as accessions 4, 8, and 13, are more suitable for large-scale pulp extraction and industrial processing.

Moreover, the considerable variation in physicochemical attributes, including soluble solids, acidity, and sugar content, allows for the identification of accessions with desirable sensory profiles, facilitating product diversification and increasing market potential. These findings underscore the importance of preserving and utilizing the genetic resources of umbu to strengthen regional production chains and agro-industrial applications.

Furthermore, the diversity observed within a single population reflects the natural variability of the species in its native area, emphasizing the importance of selecting and conserving superior accessions[33,34]. As an endemic species adapted to water scarcity, umbu plays a crucial role in the local ecosystem and agriculture of the region[6]. This variability serves as a valuable parameter for conservation strategies and sustainable management practices, ensuring a long-term resilience and productivity of umbu orchards.

From a practical perspective, these insights can guide producers and agroindustries in selecting accessions[33] that align with specific production goals, whether for fresh fruit markets, processed products, or the development of bioactive compounds. Finally, this study provides a solid scientific foundation for breeding programs, sustainable use, and the development of high-value-added applications for umbu, contributing to the economic and agricultural advancement of the Brazilian semi-arid region.

-

This study highlights the potential for selecting superior umbu accessions for agricultural and commercial purposes, enabling increased fruit production and the development of value-added products in the semi-arid region. Conserving the genetic diversity of these accessions is essential to ensuring population resilience to environmental changes, advancing sustainable agricultural practices, and strengthening food security.

The observed diversity, exemplified by the high vitamin C content of accession 1 and the significant mass and yield of accessions 4, 8, and 13, highlights their relevance for future research. These investigations should focus on agronomic adaptation, the analysis of bioactive compounds, and consumer acceptance, fostering the integration of umbu into regional and global markets and contributing to the economic and environmental sustainability of the region.

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Saraiva MMT, da Costa Araújo R, Martins LP; data collection: Saraiva MMT, Azevedo de Lucena F,Dias Costa A; analysis and interpretation of results: Saraiva MMT, Martins LP; draft manuscript preparation: Saraiva MMT, da Costa Araújo R. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Saraiva MMT, Azevedo de Lucena F, Dias Costa A, Martins LP, da Costa Araújo R. 2025. Quality attributes of different umbu (Spondias tuberosa) accessions and their main components. Technology in Horticulture 5: e019 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0014

Quality attributes of different umbu (Spondias tuberosa) accessions and their main components

- Received: 20 September 2024

- Revised: 28 February 2025

- Accepted: 05 March 2025

- Published online: 07 May 2025

Abstract: Umbu (Spondias tuberosa) tree is a fruitful species, endemic to the Brazilian semiarid region, widely distributed in its center of origin; this plant has great environmental and socioeconomic importance due to the expressive production of fruits of high nutritional value. Therefore, this study evaluated the quality and variability of fruits from 14 accessions of umbu tree, within the same population in the territory of Western Cariri in Paraíba (Brazil), through physical, chemical, and physicochemical analyses. The studied attributes were fruit mass, peel, and seed content, longitudinal and transverse diameters, shape, yield, firmness, soluble solids content, titratable acidity, the ratio of soluble solids content to titratable acidity, pH, vitamin C, sugars, moisture, and ashes; which were submitted to the test of means and principal component analysis. The results indicated considerable diversity of the umbu fruit in the region, presenting different sizes, shapes, textures, chemical composition, and other physicochemical traits, which increases the range of possibilities for the consumption, use, and exploitation of this fruit. Exemplified by the high vitamin C content of accession 1 and the significant mass and yield of accessions 4, 8, and 13.

-

Key words:

- Brazilian semiarid /

- Fruits diversity /

- Caatinga /

- Characterization