-

Lycium, commonly known as 'goji', 'wolfberry', and 'gouqi', one of the traditional Chinese herbs, belongs to the Solanaceae family[1]. It is known for its unique nutritional profile, rich in polysaccharides, polyphenols, carotenoids, and other bioactive compounds. It has been demonstrated to have effects on aging, fatigue, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and immune system function[1−3]. Consequently, there has been a notable increase in interest in Lycium, with a particular focus on its health benefits. Traditionally, Lycium has been consumed in its fresh form, often soaked in water or used medicinally[1]. Nowadays, it is also utilized in various products, including juices, jams, bakery products, energy bars, and dietary supplements, catering to diverse health and nutritional needs[4,5]. Several species of Lycium, such as Lycium barbarum (L. barbarum), Lycium ruthenicum Murr. (L. ruthenicum Murr.), Lycium dasystemum (L. dasystemum), and Lycium intricatum Boiss. (L. intricatum Boiss.), are cultivated in various regions, including Central Asia, Southern Africa, and parts of the Americas and Australia[6]. At present, the global Lycium cultivation areas are estimated to be approximately 1.76 × 105 ha, and China is the world's largest producer of Lycium, with about 1.33 × 105 ha of planting areas. The production of fresh Lycium berries reached 1.4 million tons, with a processing conversion rate of 20%, yielding approximately 7,000 tons of Lycium seed waste.

Lycium seeds, which constitute 15%−20% of the total fresh fruit yield, are a significant byproduct of fruit processing[7−10]. However, the current utilization of Lycium seeds is limited. The annual production of Lycium seed oil in China is approximately 7 tons, with a sales volume of 3.85 tons. This highlights their significant untapped potential, underscoring the importance of further research and development to fully explore their value. Lycium seeds contain a valuable source of carbohydrates (46.5%), oil (18%−22%), polyphenols (2%−6%), polysaccharides (7.78%), proteins (12%−15%), and minerals[8,9,11,12]. Despite their nutritional richness, the large number of seeds in the process of Lycium is a difficult problem for the food industry to solve. While there is basic public knowledge about the nutritional components of Lycium, due to the limited research focused on Lycium seeds, they are primarily used as animal feed, fertilizer, or discarded, leading to significant waste[13]. As a typical underutilized raw material, Lycium seeds have significant potential for further use. Therefore, this review summarizes and analyzes Lycium seeds from three aspects: bioactive compounds and extraction methods, bioactivity, and applications.

Existing literature has thoroughly explored the bioactive components, extraction methods, and molecular characteristics of Lycium seeds, which are rich in bioactive compounds such as oils, phenolic compounds, polysaccharides, and proteins. Studies have compared the effects of different varieties and extraction methods on yield and bioactivity. Additionally, this paper reviews the various bioactivities of Lycium seeds, including anti-fatigue, neuroprotective, anti-diabetic, anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-obesity effects, and provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms behind these functions. Furthermore, this work also examines the potential applications of Lycium seeds in pharmaceuticals, functional foods, and animal feed. This is with a view to promoting the efficient utilization of discarded by-products, contributing to sustainable development, and enhancing their industrial value in the fields of medicine, the food industry, and agriculture.

-

Lycium seeds are a rich source of various nutrients. However, existing research has predominantly focused on Lycium seed oil. Optimizing extraction methods for Lycium seeds is crucial to maximizing yield and selectively extracting bioactive compounds. The selection of extraction methods can target specific nutrients, as shown in Tables 1−3.

Lycium seed oil

-

Lycium seed oil is highly valued as an edible oil due to its substantial content of unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs), including oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid, as well as saturated fatty acids (SFAs), such as palmitic acid[13,14]. It also contains other beneficial compounds including tocopherols, phytosterols, and carotenoids[9,15].

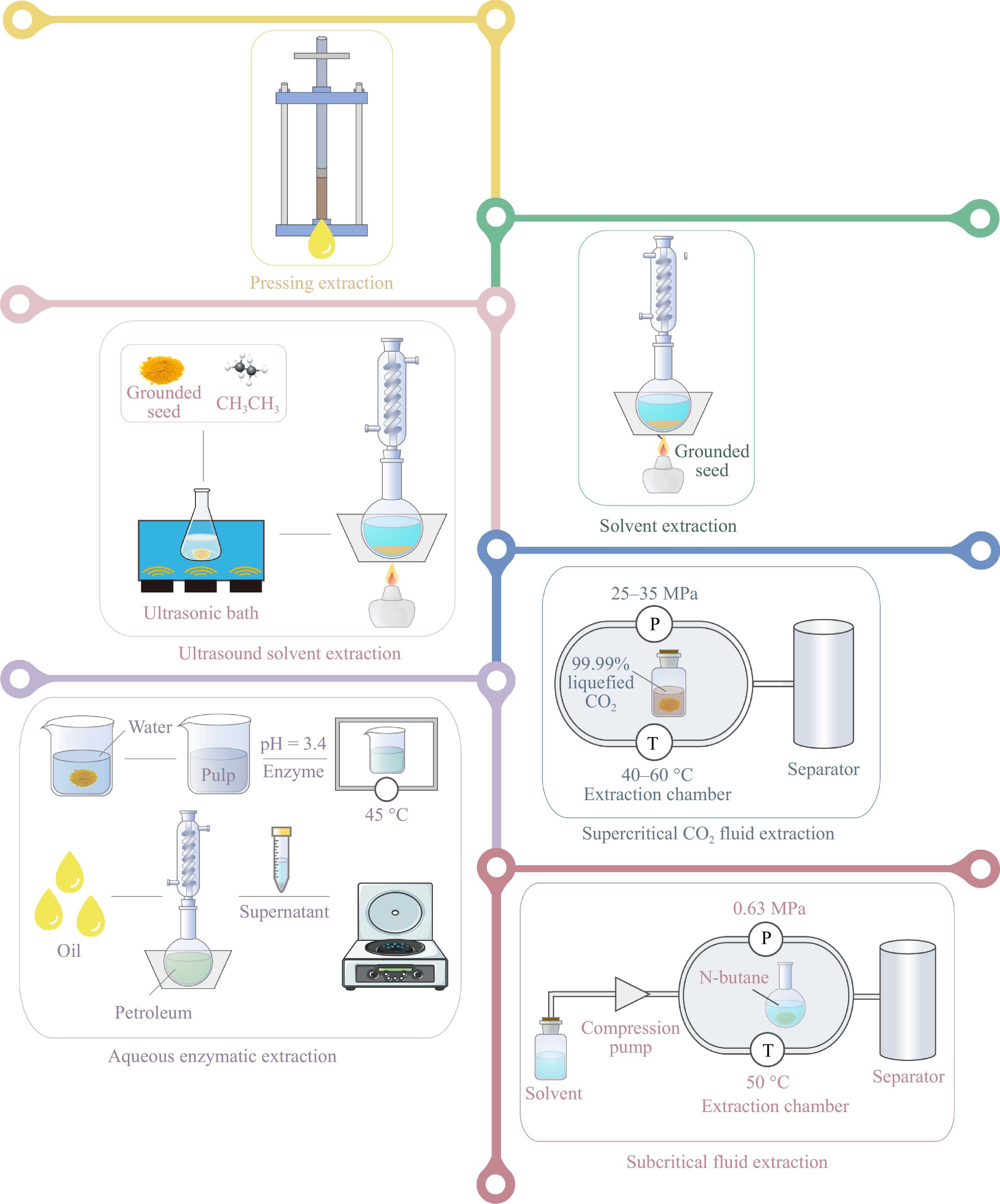

The selection of an extraction method needs a balance between yield, product quality, process efficiency, cost, and environmental sustainability[16]. Several methods are available for extracting Lycium seed oil, as shown in Fig. 1, and the different operating conditions of each method affect the composition and yield of the Lycium seed oil. Pressing extraction is a conventional method that is characterized by its operational simplicity, safety, and environmentally benign nature. However, it is limited by relatively low extraction yields[13]. For commercial Lycium seed oil production using inedible oil, cold pressing is a commonly used method. Pressing extraction method yielded 10%−13% oil, while under hot pressing conditions, the content of SFAs in Lycium seed oil was 5.2% higher than under cold pressing conditions[15]. However, the content of UFAs was 0.55% lower, likely due to the destruction of some unsaturated bonds by high temperatures[15]. Solvent extraction is widely used in industrial oil extraction, but it presents issues with organic solvent residues and pollution of the environment[13]. The yield of Lycium seed oil in this extraction method was 12%−20%[6,15,17]. Yield is also affected by the extraction solvent. The concentration of free fatty acids obtained from n-hexane extraction was approximately 4.28% higher than that from petroleum ether[18].

Ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction was demonstrated to improve the efficiency of solvent extraction, and the yield of specific varieties of Lycium seed oil can be increased by 15% using this method while retaining a higher content (90%) of UFAs[15]. Supercritical CO2 fluid extraction and subcritical fluid extraction are novel extraction techniques with the advantages of non-toxicity, environmental friendliness, and high oil yield, whereas these two methods are limited in large-scale industrial production due to high investment cost[15,17]. Extraction of Lycium seed oil by supercritical CO2 fluid extraction is used in the commercial production of high-grade edible oil. The yield of Lycium seed oil under supercritical CO2 extraction was around 15%−19%, and the yield under subcritical fluid extraction was 21%[9,13,15,17,19]. Aqueous enzymatic extraction has the advantages of low energy consumption and less pollution, achieving high extraction efficiencies with 87.6%, however, this method has been found to result in the formation of formed emulsified oil[20]. The particular methodologies utilized by the researchers in the extraction of Lycium seed oil are delineated in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of extracted methods of Lycium seed oil.

Extraction method Extraction conditions Main composition of the oil Yield (%) Material Ref. Pressing extraction Use a screw-press oil expeller to press seeds below 60 °C, then purifying through centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 15 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18, C18:3 10.5−12.5 L. barbarum [15] Use a centrifugal oil extractor to press the pretreated powder seeds for 2 h and then filtrating. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18 12.63 L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] Use a screw-press oil expeller to press seeds at 150 °C, then purifying through centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 15 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18:3, C18 11.0−13.0 L. barbarum [15] Solvent extraction Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 °C. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18, C18:3 12.0−15.0 L. barbarum [15] Extract with n-hexane using a Soxhlet extractor for 6 h, then evaporating under reduced pressure at 40 °C. C18:2, C16:1, C22:1, C14, C18:1 20 ± 3 L. intricatum Boiss. [6] Extract with n-hexane using a Soxhlet extractor at 40−60 °C for 4 h, then evaporating under vacuum at 70 °C. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18, C18:3 16.25 L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] Ultrasound-assisted extraction Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 °C. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18:3, C18 14.0−16.0 L. barbarum [15] Supercritical CO2 fluid extraction Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 °C for 90 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18:3, C18 10.0−12.0 L. barbarum [15] Extract with CO2 with a flow rate of 30 g/min at 250 bar and 60 °C for 2 h, with the use of co-solvent 2% ethanol. C18:2, C18:1, C18:3 17.0 ± 0.67

(without cosolvent),

15.2 ± 0.42

(with cosolvent)L. barbarum [13] Extract with CO2 with a flow rate of 25 kg/h at 30 MPa and 45 °C for 60 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18, C20:6 19.28 L. barbarum [19] Extract with CO2 with at 35 MPa and 40 °C for 90 min. C18:2, C18:1, C18:3, C16, C20 8.56 L. ruthenicum Murr. [9] Extract with CO2 with a flow rate of 80 L/h at 26 MPa and 55 °C for 60 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18 19.76 L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] Subcritical fluid extraction Extract with n-butane in the form of subcritical fluid at 0.63 MPa at 50 °C for 48 min. C18:2, C18:1, C16, C18, C18:3 21.20 L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] Aqueous enzymatic extraction Enzymatic hydrolysis at pH 3.4 and 45 °C using Viscozyme L, centrifuge the obtained solution at 5,000 rpm for 30 min. Add petroleum ether to the supernatant to extract the oil, followed with rotary evaporation. — 87.6 L. barbarum [20] It is crucial for maintaining the biological activity of the extract to select the appropriate extraction method. Compared to other extraction methods, supercritical CO2 fluid extraction and subcritical fluid extraction are particularly effective in preserving antioxidant activity, as they operate under milder conditions that reduce the risk of oxidative degradation[9,13,15,17,19]. Under supercritical CO2 fluid extraction conditions resulted in a peroxide value 50% lower than pressing extraction, indicating a reduced oxidative degradation under milder conditions[14]. Compared to supercritical CO2 fluid extraction, subcritical fluid extraction operates at a lower pressure, thereby enhancing the retention of bioactive substances[17].

Lycium seed oil provides an abundance of UFAs as well as a small amount of SFAs. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the fatty acid profiles of Lycium seed oil. For instance, L. barbarum predominantly contains linoleic acid (65.18%−67.36%), oleic acid (15.64%−22.12%), palmitic acid (3.26%−7.12%), stearic acid (2.87%−4.89%), and γ-linolenic acid (1.16%−4.55%)[15,19]. L. ruthenicum Murr. and L. dasystemum exhibited similar profiles to L. barbarum, but L. ruthenicum Murr. provided the highest linoleic acid (70.19%−73.94%), 14.4% higher than L. barbarum and 16.4% higher than L. dasystemum, and L. dasystemum seed oil provided the least amount of stearic acid (1.1%−1.4%)[9,13−15,17,19]. L. intricatum Boiss. has a different profile, with lower concentrations of linoleic and oleic acids, but higher levels of palmitoleic acid (27.96%), erucic acid (13.62%), and myristic acid (5.3%)[6,9,13−15,17,19]. The variation in fatty acid composition of Lycium seed oil may play a significant role in its distinct bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. Consequently, a detailed understanding of its fatty acid profile is essential for selecting the most suitable species for specific health benefits or industrial applications, such as in the healthcare and functional food sectors.

Table 2. The relative content of fatty acids (FA) in Lycium seed oil under different extraction methods.

Material Extraction method C18:2 (%) C18:1 (%) C16 (%) C18:3 (%) C18 (%) SFA (%) UFA (%) Ref. L. barbarum PE 65.8−65.95 20.11−20.42 6.28−6.63 2.61−2.90 3.36−3.7 9.65−10.15 89.85−90.35 [15] SE 65.24 19.76 7.03 2.75 3.99 11.08 88.92 USE 65.82 20.23 6.4 2.83 3.39 9.92 90.08 SCFE 60.32−67.36 15.64−22.12 3.26−7.68 1.16−4.55 2.87−4.89 8.15−13.61 84.21−91.85 [13,15,19,121] L. ruthenicum Murr. PE 73.53 18.81 3.89 0.75 1.10 — > 92% [17] SE 68.31−72.06 17.76−19.3 4.22−5.37 1.37−4.77 1.12−2.58 8.91 91.10 [17,85] SCFE 73.31−74.56 11.82−19.55 3.93−4.88 0.55−6.6 1.22−1.4 6.70 93.31 [9,17] SFE 73.36 18.7 4.09 0.92 1.17 5.26 92.98 [17] L. dasystemnm PE 63.05 21.13 1.49 2.82 3.5 > 9.52 > 86.19 [14] SCFE 67.19 18.17 6.24 0.83 3.12 > 5.56 > 87.00 L. intricatum Boiss. SE 49.47 2.99 0.63 — — 5.93 94.04 [6] FAs: fatty acids; SFA: saturated fatty acids; UFA: unsaturated fatty acids; PE: pressing extraction; SE: solvent extraction; USE: ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction; SCFE: supercritical CO2 fluid extraction; SFE: supercritical fluid extraction. Current extraction methods for Lycium seed oil are largely derived from techniques used for other seed oils, such as pumpkin seed oil and rapeseed oil, which employ similar extraction procedures[21,22]. The active components of Lycium seeds differ from those in other seeds, and the extraction method employed significantly influences the composition of the resulting extract. Additionally, variations in extraction conditions further impact the obtained components. These factors collectively contribute to the distinct differences in the extraction processes and outcomes of Lycium seed oil compared to oils derived from other seeds.

Lycium seed polyphenols

-

Polyphenols are a class of antioxidants that help protect lipids, proteins, enzymes, carbohydrates, and DNA in cells and tissues from oxidative damage[23]. The primary classes of polyphenols are flavonoids, lignans, stilbenes, and phenolic acids[24,25]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis has identified several compounds in Lycium seeds, such as quercetin, kaempferol, and chlorogenic acid, which contribute significantly to the antioxidant activities of the extracts[26].

Ethanol is commonly used as an efficient solvent for extracting polyphenols from Lycium seeds. For instance, reflux extraction with 95% ethanol for 1.5 h, yielded 26.7 mg/g of polyphenols[26]. Another study reported that an initial extraction with 60% ethanol followed by ultrasonic treatment, yielded between 1.19 and 3.37 mg GAE/g of polyphenols, with L. ruthenicum Murr. seeds containing up to 2.63 times higher polyphenol content than L. barbarum seeds[27]. Additionally, geographical variations also have an impact, with polyphenol content varying from 2.23 mg GAE/g in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regione to 3.37 mg GAE/g in Qinghai Province for L. ruthenicum Murr. seeds[27].

Polyphenols in Lycium seeds are predominantly composed of flavonoids such as quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin, which are highly regarded for their strong free radical scavenging capabilities[26]. These flavonoid compounds play a critical role in mitigating oxidative stress-induced free radical damage, contributing significantly to the prevention of cardiovascular and degenerative diseases[28,29]. Additionally, Lycium seeds contain abundant phenolic acids, including chlorogenic acid and gallic acid, which are essential in antioxidative processes[26,30]. Current research on polyphenols in Lycium seeds primarily focuses on flavonoid compounds due to their significant health benefits and bioactivity. In Gao's study, ultrasonic extraction with 95% ethanol yielded approximately 5.8 mg/g flavonoids[26]. Another study reported yields of 0.62 and 2.37 mg CAE/g flavonoids, with the highest content observed in L. ruthenicum Murr. from Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

This demonstrates that both the variety and geographical location can significantly influence flavonoid content[27]. The variability in polyphenol content observed between different regions and species can be attributed to factors such as soil composition, climate, and genetic differences, which affect the biosynthesis and accumulation of these compounds[31].

Lycium seed polysaccharides

-

Polysaccharides are a class of biomolecules composed of different monosaccharides linked by α or β glycosidic bonds and substituted by hydroxyl groups on hemiacetal groups[32]. The presence of hydroxyl groups in polysaccharides is responsible for their biological activities such as antitumor, antibacterial, antiviral, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant[32−34].

Typically, soaking in distilled water is used to extract polysaccharides from medicinal herbs[35]. After oil removal, water extraction at room temperature for 2 h yields 2.84% crude polysaccharides from L. barbarum seeds[26]. This method is simple and widely used, but it has relatively low extraction efficiency. The water decoction extraction method, involves three cycles of extraction, each lasting 40 min, with a material-to-liquid ratio of 1:40 (g/mL)[36], the average polysaccharide yield is 10.65% from L. barbarum seeds. This method effectively enhances extraction efficiency through multiple cycles, making it suitable for large-scale production, though it requires higher energy input. Both methods are effective for extracting integral polysaccharides but have limitations in separating and analyzing specific functional components.

In addition, a novel sequential extraction method has been developed, whereby the dregs undergo four stages of extraction with distinct solvents solution: hot buffer solution (HBSS), chelating agent solution (CHSS), dilute alkaline solution (DASS), and concentrated alkaline solution (CASS), as shown in Table 3[37]. This method yields polysaccharide fractions ranging from 2.79% to 5.60% from L. barbarum seeds[8]. Sequential extraction enables the separation of polysaccharides in various binding states, facilitating the analysis of different components. Although the yield is lower compared to water extraction methods, this approach is particularly suitable for in-depth studies of functional polysaccharides.

Table 3. Summary of the active compounds of Lycium seeds.

Compound Method Yield Material Ref. Polyphenol 60% ethanol and Scientz-IID ultrasonic cell disrupter for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. 2.23 ± 0.93 to 3.37 ± 1.33 mg GAE/g L. ruthenicum Murr. [27] 1.35 ± 0.29 mg GAE/g L. barbarum (big) 1.19 ± 0.55 mg GAE/g L. barbarum (small) Extraction using a 500 mg Sepax Generik Diol column with methanol, hexane, ethyl acetate, and Folin-Ciocalteu reagent for 2 h. HP: 113.87 ± 4.04 mg/kg L. barbarum [15] SFE: 65.89 ± 1.39 mg/kg CP: 79.19 ± 2.93 mg/kg SE: 35.65 ± 0.42 mg/kg USE: 40.47 ± 1.95 mg/kg Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and

40 ºC for 90 min.5.97 ± 0.10 to 10.21 ± 0.55 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [9] Reflux extraction with 95% ethanol for 1.5 h. ~26.7 mg/g L. barbarum [26] Total flavonoid Ultrasonicated three times with 95% ethanol. ~5.8 mg/g L. barbarum [26] 60% ethanol and Scientz-IID ultrasonic cell disrupter for 30 min, followed by centrifuge at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. 2.37 ± 0.91 to 1.79 ± 1.30 mg CAE/g L. ruthenicum Murr. [27] 1.18 ± 0.07 mg CAE/g L. barbarum (big) 0.62 ± 0.20 mg CAE/g L. barbarum (small) Polysaccharide Ether and 80% ethanol, by Soxhlet reflux method for 1 h Seed: ~28.4 mg/g L. barbarum [26] Seed dreg: ~13.2 mg/g [26] HBSS extraction with 0.05 mol/L CH3COONa at 70 ºC, pH 5.2, for 1 h. ~41.06 mg/g Rha 15.34% L. barbarum [8] Xly 64.63% Ara 4.48% Gal 9.35% Man 4.87% Glc 1.75% CHSS extraction with 0.05 mol/L (NH4)2C2O4, CH3COONa, and EDTA-2Na at 70 ºC, pH 5.2, for 1 h. ~23.04 mg/g Rha 12.59% Xly 70.00% Ara 4.68% Gal 9.93% Man 1.49% Glc 1.31% DASS extraction with 0.05 mol/L NaOH and 20 mmol/L NaBH4 at 70 ºC for 1 h. ~36.24 mg/g Rha 9.39% Xly 44.71% Ara 2.84% Gal 6.27% Man 35.04% Glc 1.76% CASS extraction with 5 mol/L NaOH and 20 mmol/L NaBH4 at 4 ºC for

2 h, then centrifuged at 7,155 rpm for 15 min.~47.29 mg/g Rha 17.23% Xly 66.67% Ara 4.55% Gal 9.75% Man 0.68% Glc 1.11% — 46.50% L. barbarum [15] Protein Isolated protein extraction at 40 ºC, pH 9−9.5, for 2 h with a ratio of 1:12, followed by pH adjustment to 4.5 and centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. 85.67% L. barbarum [11] Seed protein extraction at 40 ºC, pH 9−9.5, for 2 h with a ratio of 1:12, then pH adjustment to 4.5 for 10 min. 22.13% L. barbarum [11] Alkali extraction and acid deposition. 15% — [12] α-tocopherol Extract with n-butane in the form of subcritical fluid at 0.63 MPa at

50 ºC for 48 min.10.84 ± 0.42 to 21.35 ± 1.64 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] HP with 150 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 36.18 ± 0.38 mg/kg L. barbarum, [15] CP with below 60 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 33.49 ± 0.75 mg/kg SE: Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 ºC. 31.99 ± 1.27 mg/kg USE: Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 ºC. 32.88 ± 0.70 mg/kg SCFE: Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 27.17 ± 1.02 mg/kg γ-tocopherol Extract with n-butane in the form of subcritical fluid at 0.63 MPa at

50 ºC for 48 min.2.22 ± 0.11 to 9.22 ± 0.59 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] HP with 150 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 452.31 ± 5.54 mg/kg L. barbarum [15] CP with below 60 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 380.80 ± 1.18 mg/kg SE: Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 ºC. 384.19 ± 0.32 mg/kg USE: Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 ºC. 385.73 ± 0.59 mg/kg SCFE: Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 265.48 ± 0.79 mg/kg Carotenoid Extract with n-butane in the form of subcritical fluid at 0.63 MPa at

50 ºC for 48 min.35.75 ± 3.66 to 49.61 ± 3.18 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [17] HP with 150 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 43.57 ± 0.20 mg/kg L. barbarum [15] CP with below 60 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 33.71 ± 0.39 mg/kg SE: Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 ºC. 41.51 ± 0.10 mg/kg USE: Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 ºC. 46.16 ± 0.15 mg/kg SCFE: Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 4.17 ± 0.05 mg/kg Stigmasterol HP with 150 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 826.97 ± 55.53 mg/kg L. ruthenicum Murr. [15] CP with below 60 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 778.40 ± 14.98 mg/kg SE: Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 ºC. 872.17 ± 53.48 mg/kg USE: Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 ºC. 894.27 ± 50.52 mg/kg SCFE: Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 671.15 ± 17.93 mg/kg Solvent extraction with n-hexane, chloroform, and petroleum ether for 6 h at 40 ºC. ~18.56 mg/100 g L. intricatum [6] Extract with CO2 with at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 3.34 ± 0.03 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [9] ß-Sitosterol HP with 150 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 1,901.48 ± 15.18 mg/kg L. ruthenicum Murr. [15] CP with below 60 ºC; Centrifugal condition: 4,000 rpm for 15 min. 1,965.72 ± 45.97 mg/kg SE: Extract with hexane for 30 min, then evaporating under vacuum at 45 ºC. 1,940.95 ± 29.62 mg/kg USE: Extract with hexane for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath with 750 W and 40 kHz and repeat twice, evaporating under vacuum at 70 ºC. 2,062.34 ± 9.40 mg/kg SCFE: Extract with 99.99% CO2 with a flow rate of 1 L/min at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 1,843.27 ± 39.05 mg/kg Solvent extraction with n-hexane, chloroform, and petroleum ether for 6 h at 40 ºC. ~13.04 mg/100 g L. intricatum [6] Extract with CO2 with at 35 MPa and 40 ºC for 90 min. 38.50 ± 0.09 mg/100 g L. ruthenicum Murr. [9] HP, hot pressing extraction; CP, cold pressing extraction; SE, solvent extraction; USE, ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction; SCFE, supercritical CO2 fluid extraction; Rha, rhamnose; Xly, xylose; Ara, arabinose; Gal, galactose; Man, mannose; Glc, glucose. Extracted polysaccharides consist of rhamnose, xylose, arabinose, galactose, mannose, and glucose. These monosaccharides form complex structures through glycosidic bonds, with common linkages including β-(1→3), α-(1→4), and β-(1→6)[38]. Among the samples, HBSS has the highest rhamnose (15.34%) and xylose (64.63%) content. CHSS also has a high xylose content (70.00%) but lower rhamnose (12.59%). DASS has a considerable quantity of mannose (35.04%). CASS has the highest rhamnose content (17.23%) and also high xylose content (66.67%), but much lower mannose (0.68%)[8]. These variations in monosaccharide composition highlight the structural differences in polysaccharide structures extracted by different methods, which may influence their biological activities.

Among the methods for selectively altering the structure and function of polysaccharides, chemical modification has proven to be the most effective[39]. Modifying Lycium seed residue polysaccharides through sulfation, phosphorylation, and carboxymethylation significantly enhances their functional properties[40]. After modification, the uronic acid content increased markedly, with sulfated polysaccharides showing an increase from 0.69% in natural polysaccharides to 7.03%. In terms of antioxidant activity, sulfated polysaccharides exhibited an improved 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline 6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS•+) radical scavenging rate, rising from 20.17% to 37.22%, along with enhanced reducing power, reaching 0.13 mg/mg (VC equivalent). Phosphorylated polysaccharides showed the best Fe2+ chelating capacity, achieving 48.08%.

Lycium seed protein

-

Food protein and food-derived peptides have garnered attention as potential components in functional foods and natural health product formulations[41]. The proteins derived from Lycium seeds have been reported to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities[11]. Elucidating their structure-function relationships, including detailed analyses of their amino acid sequences and three-dimensional conformations, is essential for optimizing their application in diverse health-related fields[7,11,42].

Proteins from Lycium seeds are typically extracted using alkaline extraction (pH = 9−9.5) followed by acid precipitation (pH = 4.5). Protein isolate from Lycium seeds has been reported to contain 85.67% protein[11]. Lycium seed proteins are rich in essential amino acids, including leucine (3.88 mg/100 mg), which is crucial for muscle protein synthesis and repair, helping stimulate muscle growth and recovery. Phenylalanine (2.86 mg/100 mg) is vital for cognitive function and mood regulation, while valine (2.69 mg/100 mg) plays a role in energy metabolism[43,44]. Additionally, the protein extract contains non-essential amino acids, such as glutamic acid (9.38 mg/100 mg), which contribute to the overall nutritional value of the extract[43−45]. These amino acids contribute to a variety of physiological functions, making Lycium seed proteins a promising ingredient for enhancing immune function and alleviating conditions such as vascular diseases, diabetes, osteoporosis, and chronic inflammation.

Other compounds

-

In the extraction of Lycium seed oil, several bioactive compounds such as tocopherols, phytosterols, and carotenoids are also obtained.

Tocopherols, particularly α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol, are prominent antioxidants in Lycium seed oil, playing a crucial role in preventing oxidative damage to cellular lipids and offering protective effects against cardiovascular and aging-related diseases[46,47]. The extraction yield of tocopherols varies depending on the method used. For instance, hot pressing yields the highest tocopherol content at 488.49 mg/kg due to the disruption of cell membranes, which facilitates the release into the oil phase, while subcritical fluid extraction results in lower yields at 29.26 mg/100 g[15,48]. Additionally, there is considerable variation in the tocopherol content of L. ruthenicum Murr. seeds, with values ranging from 31.35 mg/100 g to 14.84 mg/100 g depending on the geographical origin, with α-tocopherol predominating form, representing approximately 70% of total tocopherols[17].

Phytosterols represent a distinctive category of structural lipids that enhance cell membrane stability and contribute to micro-fluidity, playing key roles in processes such as cell signaling and cellular sorting[49]. In Lycium seed oil, phytosterols, such as β-sitosterol (46%), Δ7-sitosterol (21%), campesterol (8%), and stigmasterol (5%), are known to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), thereby lowering the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)[3,50]. The extraction method significantly affects phytosterol yields. Ultrasound-assisted extraction yields the highest amount, at 16.68 mg/g, compared to 9.61 mg/g from subcritical fluid extraction[9]. Analysis of different L. barbarum seed oil (LBSO) revealed concentrations of campesterol at 22.50 mg/100 g, stigmasterol at 3.34 mg/100 g, and β-sitosterol at 38.50 mg/100 g. The sterol fraction extracted by organic solution was composed of stigmasterol (18.56 mg/100 g), β-sitosterol (13.04 mg/100 g), and ergosterol (8.12 mg/100 g). In comparison, total phytosterols were about 39.72 mg/100 g[6].

Carotenoids are essential for all photosynthetic organisms due to their significant photoprotective and antioxidant properties, with compounds such as β-carotene being effectively dissolved and extracted using various techniques[51]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction was demonstrated to be particularly efficient, achieving the highest carotenoid concentration at 4.62 mg/100 g, whereas supercritical fluid extraction offered the lowest at 0.417 mg/100 g[15]. The disruptive effect of ultrasound on cell structures significantly enhanced carotenoid extraction[52]. The β-carotene content of L. ruthenicum Murr. seeds exhibited a modest degree of variation between different origins. The highest concentration, 49.61 mg/100 g, was observed in Nuomuhong Qinghai Province, while the lowest, 35.75 mg/100 g, was identified in Cele Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region[17].

Lycium seeds also contain many additional components[15]. These include crude fiber (7.78 g/100 g), calcium (112.5 mg/100 g), iron (8.42 mg/100 g), nucleic acid (4.32 mg/100 g), and riboflavin (1.27 mg/100 g), which are present in higher quantities compared to fresh and freeze-dried fruits. Furthermore, Lycium seeds are also rich in potassium (1.132%), phosphorus (0.178%), sodium (0.1498%), zinc (0.0021%), and other nutrients or components. These minerals have been demonstrated to have anti-aging and metabolic benefits, which contribute to the overall health-promoting properties of Lycium seeds[15].

-

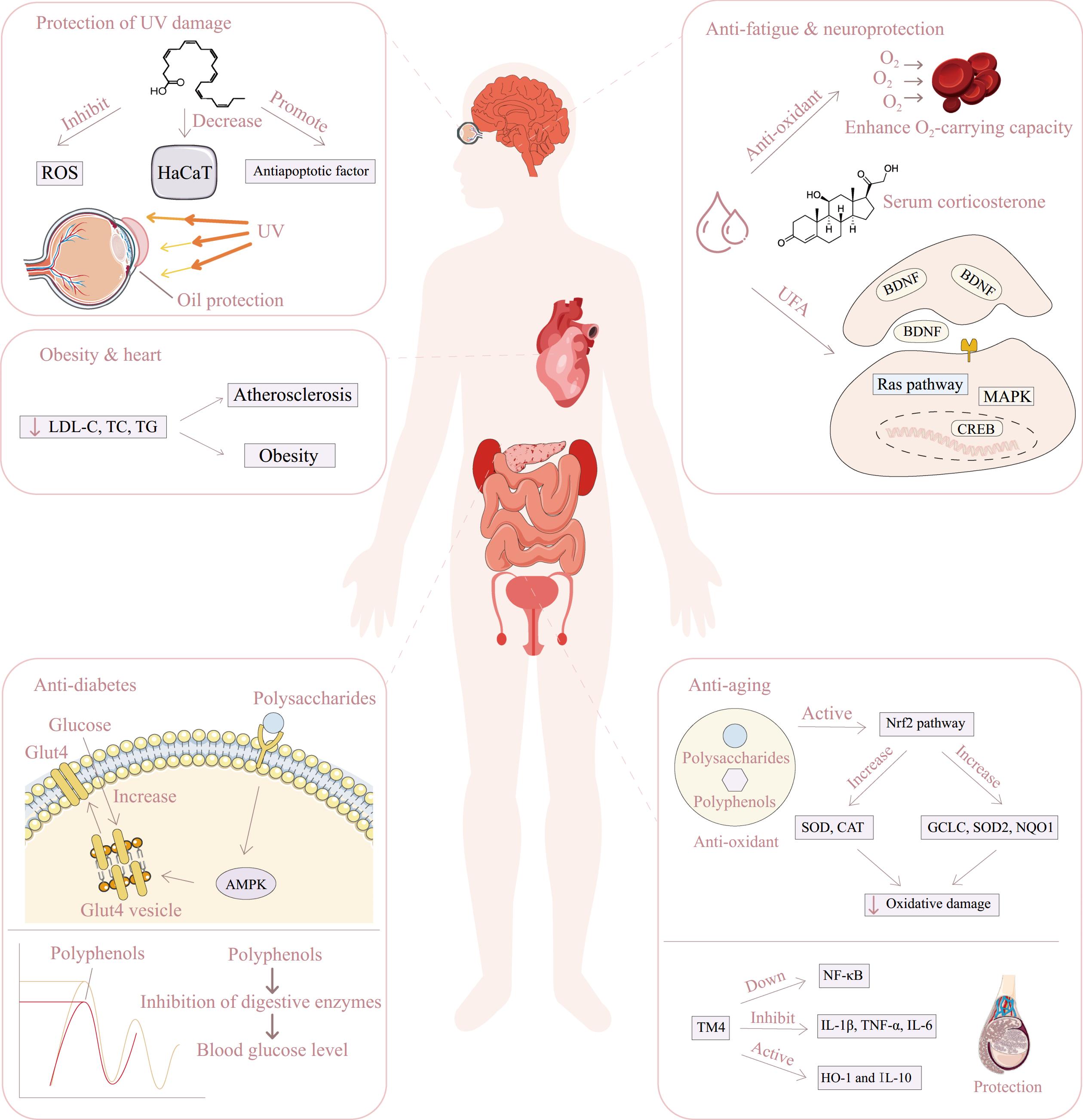

Lycium seeds contain a diverse range of bioactive compounds such as fatty acids, polysaccharides, polyphenols, and others. These compounds have gained considerable attention due to their potential health benefits, such as antioxidant, anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antihypertensive, hypolipidemic, and cardiovascular protective properties[9,15,53]. Consequently, a comprehensive investigation of these functions and mechanisms is imperative to fully comprehend the potential benefits of Lycium seeds. The studies related to these benefits are summarized in Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Table 4. Summary of Lycium seed bioactivity.

Bioactivity Method Result Mechanism Ref. Anti-fatigue Low dose (10 mg/kg body weight (BW)), Medium dose (20 mg/kg BW), High dose (40 mg/kg BW ) for 3 weeks. Significantly extended swimming time and survival time under hypoxia. Enhance blood oxygen capacity and antioxidant ability [58] Anti-fatigue LBSO (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg BW) and fluoxetine (20 mg/kg BW) were administered daily. CUS modeling for 28 d. LBSO improved behavior in CUS mice, increasing horizontal crossing and decreasing immobility in tail suspension and forced swimming tests. Reduce serum corticosterone levels and promote hippocampal CREB-BDNF pathway [59] Anti-diabetes Low dose (2.5 mg/kg BW), medium dose (5 mg/kg BW), high dose (10 mg/kg BW) after a high-fat diet for 4 weeks. Improved antioxidant capacity and reduced blood glucose levels in T2D mice. Antioxidant capacity [69] Anti-diabetes C57BL/6J mice diabetes induced by streptozotocin injection (70 mg/kg BW). LBSO (5, 10 mg/kg BW) and metformin (300 mg/kg BW) groups were administered daily for 5 weeks. Reduced blood glucose, urine glucose, and renal tissue IL-8 in diabetic mice. Decreased blood glucose and urine protein quantity [71] Neuroprotection SD rats underwent common carotid artery ligation surgery. Five groups: sham-operated, model, and three LBSO dose groups (80, 40, 20 mg/kg BW). LBSO increased T-AOC activity and decreased MDA levels. Cognitive function improved significantly in rats, as shown by Morris water maze tests. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity and antioxidants [77] Neuroprotection LBSO was administered at low, medium, and high doses (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg BW) by gavage for 35 d. LBSO significantly improved cognitive function in CUS mice, reducing escape latency and increasing platform crossings in memory tests. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity and antioxidants [59] Anti-aging The LBSO group received an additional daily dose of 1,000 mg/kg BW for 4 weeks. LBSO treatment increased INHB and testosterone levels. In vitro, LBSO upregulated SIRT3, HO-1, and SOD expression, enhancing cell proliferation. SIRT3 overexpression also increased AMPK and PGC-1α levels. Protective effects against oxidative damage and improved reproductive hormone levels [90] Anti-aging LBSO was administered in low (1,000 mg/kg BW), medium (1,750 mg/kg BW), and high (2,500 mg/kg BW) doses along with D-gal (125 mg/kg BW) for 8 weeks to establish a subacute aging model in rats. LBSO significantly increased the expression of Nrf2 pathway proteins and its downstream targets (GCLC, SOD2, NQO1) in the testes of subacute aging rats. Protective effects against oxidative damage and improved reproductive hormone levels [92] Anti-atherosclerosis Low dose group (LLSO, gavage with 1 mg/kg BW) and the high dose group (HLSO, gavage with 2 mg/kg BW) for 56 d. Decreased LDL-C, TC, and TG in serum, increased HDL-C in plasma. Blood lipid reduction [95] Lipid Metabolism Five groups (normal diet, high-fat diet, 10% insoluble dietary fiber, 10% low carboxylation degree of substitution (DS), 10% high carboxylation DS) for 8 weeks. Insoluble dietary fiber inhibited weight gain and reduced lipid levels in hyperlipidemic mice. It also improved liver function, reduced inflammation, and increased short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels, promoting cholesterol reduction through gut microbiota changes. IDF can improve gut function in hyperlipidemic mice by increasing SCFAs synthesis, thereby controlling lipid metabolism and preventing lipid accumulation in the body. [97] Photoprotection HaCaT cells were treated with different concentrations of LBSO (75, 150, 300, 600 mg/kg BW) and exposed to UVB (40 mJ/cm²). Cells were incubated for 24 h post-irradiation. LBSO increased the survival rate of UVB-damaged cells, promoted Bcl-2 expression, inhibited ROS generation, reduced apoptosis, and lowered levels of pro-apoptotic factors and inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL1β, IL-6). LBSO alleviated UVB-induced photodamage by regulating apoptosis and reducing inflammation through increased Bcl-2 and decreased Bax, Caspase-3, and inflammatory markers. [98]

Figure 2.

Biological activities of Lycium seed extracts and potential mechanisms. ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; HaCaT: Human Keratinocyte; UFA: Unsaturated Fatty Acids; LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; TC: Total Cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; Glut4: Glucose Transporter Type 4; AMPK: AMP-activated Protein Kinase; Nrf2: Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2; SOD: Superoxide Dismutase; CAT: Catalase; GCLC: Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase Catalytic Subunit; SOD2: Superoxide Dismutase 2; NQO1: NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1; NF-κB: Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; IL-1β: Interleukin 1 beta; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha; IL-6: Interleukin 6; HO-1: Heme Oxygenase 1; IL-10: Interleukin 10; CREB: cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein; BDNF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase.

Anti-fatigue

-

Fatigue is a significant factor affecting physical performance[54]. Persistent fatigue has been demonstrated to reduce exercise ability and an increased risk of both physical and mental ill-health[55]. Chronic fatigue is associated with a higher likelihood of developing autoimmune diseases, depression, and cancers[56,57]. Jiang et al. demonstrated that various doses of LBSO significantly extended the swimming time of the experimental mice and their survival time under hypoxia, with higher doses yielding more positive results[58]. Similarly, Zheng administered LBSO via oral gavage at low (0.025 mL/10 g), medium (0.05 mL/10 g), and high (0.1 mL/10 g) doses to mice, followed by 28 d of chronic unpredictable stress (CUS)[59]. The results demonstrated that LBSO improved open-field test scores and alleviated depression-like behaviors in the mice, with the most notable improvements observed in the high-dose group.

The mechanism of action of Lycium seed involves multiple bioactive compounds and signaling pathways that contribute to its significant health benefits. UFAs in Lycium seed oil, such as linoleic acid and oleic acid, enhance the body's antioxidant capacity by increasing the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px)[58,60]. Additionally, Lycium seed polysaccharides regulate the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)/tyrosine receptor kinase B/xtracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway, which is critical for neuroprotection and neurogenesis[61,62]. Furthermore, studies indicate that LBSO significantly reduces serum corticosterone levels by modulating the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/cAMP response element binding protein (CREB)/BDNF signaling pathway in the central nervous system, which supports stress resistance, fatigue recovery, and cognitive function[59,63]. Its antioxidant components, including tocopherols and β-sitosterol, further promote neuroprotection by alleviating oxidative stress-induced inflammation[64,65].

Anti-diabetes

-

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by high blood glucose levels[66]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most prevalent form of the disease, characterized by insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, which are closely related to poor diet and obesity[67,68]. The study by Zhu et al. indicated that a high-dose group (0.1 mL/10 g) of LBSO showed a 34% reduction in blood glucose levels after a five-week treatment period[69]. The medium-dose group (0.05 mL/10 g) exhibited the most remarkable improvement compared to the diabetic model group, with a 36% increase in SOD activity, a 61% reduction in malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and a 26% elevation in glutathione content[69]. These findings indicate that LBSO improves antioxidant capacity and reduces blood glucose levels in mice with T2D induced by a high-fat diet. In severe cases, diabetes can lead to diabetic nephropathy, a microvascular complication that reduces the quality of life[70]. Yang et al. found that in the high-dose group (0.1 mL/10 g), LBSO reduced blood glucose (35%), urine glucose (91%), urine volume (62%), urine protein (51%), renal mass index (23%), glomerular area (22%), and renal tissue interleukin-8 (IL-8) (59%) in diabetic mice[71]. These results suggest that the anti-diabetic effects of LBSO may be attributed to its ability to enhance antioxidant defenses, lower blood glucose levels, and reduce urine protein levels.

The anti-diabetic effects of Lycium seeds are mediated through two main mechanisms. First, supercritical CO2 fluid extracts enhance glucose uptake by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, which increases the translocation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the cell membrane, thereby improving insulin sensitivity and reducing blood glucose levels[34,72]. The second mechanism involves flavonoids that inhibit digestive enzymes such as α-glucosidase and α-amylase, which slows carbohydrate digestion and absorption, thus reducing postprandial blood glucose increase[24,73]. In conclusion, Lycium seeds have the potential to be an effective dietary supplement for managing diabetes by improving antioxidant capacity, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and lowering blood glucose levels.

Neuroprotection

-

Neurodegenerative diseases are movement disorders characterized by the progressive loss of neurons and neuronal apoptosis, leading to cognitive disorders and memory impairment. These conditions result in a decline in motor functions and cognitive abilities over time, profoundly impacting the quality of life of patients[74,75]. Wu et al. demonstrated that LBSO increased total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) in brain tissue and significantly reduced MDA levels. Additionally, in the Morris water maze test, LBSO-treated rats showed significant improvements in cognitive performance, indicating that LBSO can effectively alleviate cognitive impairment induced by chronic cerebral ischemia[77]. Zheng further showed that LBSO improved open-field test campaign scoring, shortened the immobility time in both the tail suspension and forced swimming tests, and decreased the escape latency and the traveled distance in the Morris water maze test learning process[59]. Furthermore, corticosterone levels in the serum were significantly reduced when induced by CUS, and the impairments in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis feedback regulation caused by CUS were reversed[59,78].

The neuroprotective effects of Lycium seeds are attributed to its bioactive compounds, which modulate key pathways involved in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, neurotransmission, and neurogenesis. Antioxidants such as tocopherols and carotenoids activate the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) pathway, reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation, thereby protecting neuronal integrity[79]. Additionally, polysaccharides enhance the activity of SOD and GSH-Px, mitigating oxidative damage, while suppressing the Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), thereby reducing neuroinflammation[80,81].β-sitosterol, another active compound, inhibits microglial activation, further enhancing anti-inflammatory responses[82]. UFAs, such as linoleic and oleic acids, inhibit acetylcholinesterase to maintain acetylcholine levels and support cognitive functions like learning and memory[59]. Furthermore, polysaccharides activate the cAMP/CREB/BDNF pathway, promoting neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, essential for repairing neuronal damage caused by aging or oxidative stress[79]. These mechanisms collectively suggest that LBSO has significant potential as a neuroprotective agent for managing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease[83].

Anti-aging

-

The antioxidant activity of Lycium is attributed to its high content of UFAs and minor components such as tocopherols and phytosterols, which help neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress. These components contribute to the oil's anti-aging attributes[1,13,84]. Seeds from L. ruthenicum Murr. and L. barbarum exhibited significant 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and ABTS radical scavenging capacities, indicating its potential as a dietary antioxidant[9,85]. Since oxidative stress is a significant contributing factor to aging and age-related diseases, the antioxidants in Lycium seed oil activate the Nrf2 pathway, which increases the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and catalase[86]. This activation helps mitigate oxidative damage in cells and tissues, thereby slowing the aging process.

Particularly, as a traditional Chinese medicine, Lycium has the function of maintaining male fertility by alleviating testicular aging[87,88]. Treatment with LBSO in TM4 cells inhibited cell proliferation by 14.89% ± 0.89% through the downregulation of NF-κB and the suppression of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6[89]. Additionally, LBSO activated HO-1 and IL-10, contributing to its anti-inflammatory effects. Also, LBSO (1,000 mg/kg/d) alleviated oxidative stress in the testes of aging subjects induced by D-galactose both in vivo and in vitro using Sertoli cells (TM4)[90]. In vitro, half maximal effective concentration of LBSO was determined to be 86.72 ± 1.49. Intervention with LBSO (100 µg/mL) in TM4 cells resulted in an 87.82% increase in cell number, accompanied by upregulation of silent information regulator of transcription 3 (SIRT3), HO-1, and SOD.

The anti-aging effects of Lycium seeds are mediated by its ability to regulate key pathways involved in oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and reproductive health. Research indicates that silencing of SIRT3 led to dysregulation of HO-1 and SOD, while lentiviral overexpression of SIRT3 upregulated AMPK and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) expression[90]. Furthermore, Lycium seed oil has been shown to modulate reproductive hormone levels by increasing serum testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels, while decreasing luteinizing hormone levels. This modulation likely occurs through Lycium seed oil regulatory effects on testicular reproductive function via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis[91,92]. Additionally, in subacute aging rats, Lycium seed oil significantly enhanced the expression levels of Nrf2 and its downstream targets, including glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), SOD2, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAD(P)H) quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), providing protective effects against oxidative damage and further protecting testicular tissue from aging induced by oxidative stress[92].

Other functions

-

In addition to the functions mentioned above, Lycium seeds have shown remarkable health benefits, especially in managing blood lipids, reducing inflammation, and protecting against ultraviolet (UV) damage. It is important to explore how these benefits work and what potential applications they might have.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic low-inflammatory disease and is considered an underlying cause of CVDs[93]. It is characterized by high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, and triglyceride (TG), which are major contributing factors[94]. Consequently, reducing these risk factors can help alleviate atherosclerosis. Lycium seed oil has demonstrated significant anti-atherosclerotic properties by targeting lipid metabolism and inflammation-related pathways. Jiang et al. showed that high-dose LBSO (2 mL/kg) reduced LDL-C (30.73%), total cholesteryl (TC) (58.52%), and TG (68.01%) levels in serum, while simultaneously increasing HDL-C (377.42%) in plasma[95]. These effects are primarily mediated through Lycium seed oil modulation of lipid profiles, potentially by regulating the protein kinase C pathway, which contributes to reduced proliferation of smooth muscle cells and collagen secretion by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases[96].

Beyond its anti-atherosclerotic effects, Lycium seeds also contribute to managing obesity-related health issues. Carboxymethylated L. barbarum seed dreg insoluble dietary fiber (LBSDIDF) effectively mitigates hyperlipidemia induced by a high-fat diet in mice. In the high-dose LBSDIDF group, substantial reductions were observed in TC (39.66%), TG (52.86%), and LDL-C (56.98%), compared to the high-fat (HF) group, indicating a significant improvement in lipid profiles[97]. However, HDL-C levels decreased by 33.56% in the high-dose LBSDIDF group compared to the HF group. This suggests that while the intervention was successful in lowering harmful cholesterol levels, it also led to a reduction in beneficial HDL-C, which may require further investigation or additional dietary adjustments to optimize overall health benefits[97].

Furthermore, Lycium seed oil has shown protective effects against UV-induced photodamage in immortalized human keratinocytes[98]. Studies have shown that Lycium seed oil significantly increases the survival rate of UV-damaged human keratinocyte cells, promotes the expression of anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-2, inhibits intracellular ROS production, and reduces apoptosis rates[99]. Additionally, Lycium seed oil suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, through regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, which is essential for reducing UV-induced inflammation and photodamage[98].

-

Lycium seeds, rich in bioactive compounds, contribute antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antihypertensive effects. These properties make Lycium seeds highly valuable across various sectors, with applications in pharmaceuticals, functional food, and animal husbandry[69,89,92]. This section will examine the practical uses of Lycium seeds, highlighting their potential as a valuable resource in different industries.

Daily diet

-

Lycium seeds are typically consumed as the fruit, either fresh or dried. The fruit has a slightly sweet flavor, and its seeds are small and soft, making them easy to chew together with the whole fruit[88]. Including Lycium in daily meals can significantly boost the nutritional value of dishes, and regular consumption may help strengthen the body and enhance disease resistance[15,73]. With their flavor and small size, Lycium seeds are easily incorporated into a variety of foods, such as porridge, soups, baked goods, and beverages, meeting the modern demand for health benefits. Their unique taste complements a wide range of ingredients, making them a practical and popular nutritional additive that provides natural support for health enhancement.

Pharmaceuticals

-

Since oil extraction is the most common and convenient method for processing Lycium seeds, research has primarily focused on oil-based applications. The bioactive compounds extracted from Lycium seeds have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential in various pharmaceutical formulations. Lycium seeds indicate considerable promise in encapsulation and microencapsulation technologies, which enhance the stability and efficacy of bioactive compounds[13,100]. For example, microencapsulation of Lycium seed oil using octenyl succinic anhydride-starch, gum Arabic, and maltodextrin at a stabilizer concentration of 0.3% (w/v) through spray drying has effectively prevented lipid degradation, achieving high encapsulation efficiency and superior oxidative stability[100]. Compared to unencapsulated LBSO, the inhibitory concentrations (IC50) value for -OH radicals scavenging was reduced by approximately 88%, approaching the antioxidant potential of vitamin C. Similarly, the IC50 value for ABTS radical scavenging was reduced by around 82%. This improvement suggests that the LBSO Pickering emulsion has markedly enhanced radical scavenging capacity, exhibiting superior antioxidant efficacy compared to LBSO alone. This enhancement is likely due to the increased dispersibility of LBSO, which facilitates interactions with radicals. Additionally, the emulsification and encapsulation of the UFAs in LBSO with gelatin and bacterial cellulose nanofiber helped reduce oxidation, thus preserving the nutritional components of LBSO[101].

Furthermore, gel formulations containing 2% Lycium seed oil microemulsions with Tween-80, have enhanced drug retention, bioavailability, hydrophilicity, and phase transition temperature, facilitating more efficacious drug delivery[102]. The addition of Tween-80 enhances the hydrophilic properties of the Lycium seed oil microemulsion, with increased polyoxyethylene content elevating the cloud point and, consequently, the phase transition temperature. These advances underscore the medicinal value of Lycium seed extracts in enhancing drug delivery and stability.

Beyond pharmaceutical oil-based formulations, Lycium seed extracts have shown hypotensive effects and potential benefits for erectile function, emphasizing their broad pharmacological potential[103]. These findings underscore the medicinal value of Lycium seed-derived products, particularly in enhancing drug stability and providing diverse therapeutic benefits. Nevertheless, ensuring safety remains critical for the commercial production of these products. The safety of Lycium seed oil is primarily influenced by potential contamination, oxidative degradation during storage, and variability caused by different processing methods[104]. Improper handling of raw materials during production may result in microbial or other contaminants, compromising product safety. To mitigate these risks, raw materials must adhere to stringent sensory and technical standards, such as being free from mold and off-odors[105]. During storage, the high content of UFAs in Lycium seed oil makes it oxidation, leading to increased acid and peroxide values, which can negatively affect its quality and safety[106]. Consequently, storage conditions must be carefully controlled through measures. Furthermore, processing methods significantly affect the concentration of bioactive compounds. For example, compared to solvent methods, supercritical CO2 extraction is more effective at retaining active components while avoiding residual organic solvents, thereby improving product safety[15,17]. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to implement rigorous quality control measures and standardization protocols to ensure the safety, consistency, and efficacy of Lycium seed-derived products, thereby supporting their expanded use in pharmaceutical industries[107].

Functional food

-

With their rich antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulation properties, Lycium seeds, and their derivatives hold significant potential for application in functional foods. Lycium seeds can enhance the nutritional value and flavor of a wide variety of food products. For example, when the concentration of Lycium seed juice is 30%, with 5% β-cyclodextrin added, the resulting noodles display an appealing dark red color. Under these optimal conditions, the noodles achieved the highest sensory evaluation score, with a maximum water absorption rate of 216.13%, indicating significant improvements in texture and sensory properties[108]. The incorporation of Lycium seeds into flour, noodles, and other food items not only enhances taste but also offers potential health benefits.

Further enhancement of nutritional profiles and sensory characteristics was achieved by optimizing enzymatic hydrolysis processes and Maillard peptide salt formulations. Lycium seed oil, rich in UFAs and polysaccharides, significantly improved the antioxidant capacity and sensory quality of these products. The formulated salt scored 95.75 in sensory evaluation, with an antioxidant capacity of 91.72% and superior thermal stability. It also contained 264.78 g/kg sodium and 139.79 g/kg potassium, with an electronic tongue salinity response 1.71% higher than refined salt. Additionally, the Maillard peptide salt contained higher levels of umami nucleotides compared to refined salt, enhancing saltiness while allowing for reduced salt content[109].

The optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions for preparing angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from Lycium seed meal were determined as follows: alkaline protease activity of 1.42 × 104 U, ultrasonic power of 122 W, hydrolysis time of 36.5 min, and hydrolysis temperature of 50 °C. Under these conditions, the ACE inhibition rate of the Lycium seed's ACE inhibitory peptides reached a maximum of 71.28% ± 0.86%[110]. Using LBSO as a base, three oleogels—beeswax oil, rice bran wax oil (GRO), and lac wax oil—were prepared and tested as partial cocoa butter substitutes in chocolate. GRO demonstrated the highest hardness (1457 g) and oil binding capacity (99.82%), along with superior gel properties. GRO-based oleogel chocolate displayed the most stable rheological properties, best mouthfeel, and highest overall acceptability[111,112].

Animal husbandry

-

Currently, the primary market application of Lycium seeds is in animal feed production, where research indicates that Lycium seed bio-feed exhibits antimicrobial properties, inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria in livestock[113]. Supplementation with Lycium seeds has been associated with improved fermentation quality of silage, enhanced performance, and health indicators in ruminants[114,115]. The beneficial effects of Lycium seeds in animal husbandry can be attributed to their high content of bioactive compounds, including antioxidants, polysaccharides, and unsaturated fatty acids. These compounds help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in livestock, leading to improved immune responses and resistance to infections. Additionally, Lycium seeds promote beneficial microbial growth in the gut, which enhances nutrient absorption and feed efficiency[112]. By improving animal health and productivity, the use of Lycium seeds in livestock feed contributes to more sustainable and efficient agricultural practices. The utilization of Lycium seeds in animal husbandry underscores their potential to enhance animal health and productivity, thereby contributing to the sustainability of agricultural practices.

-

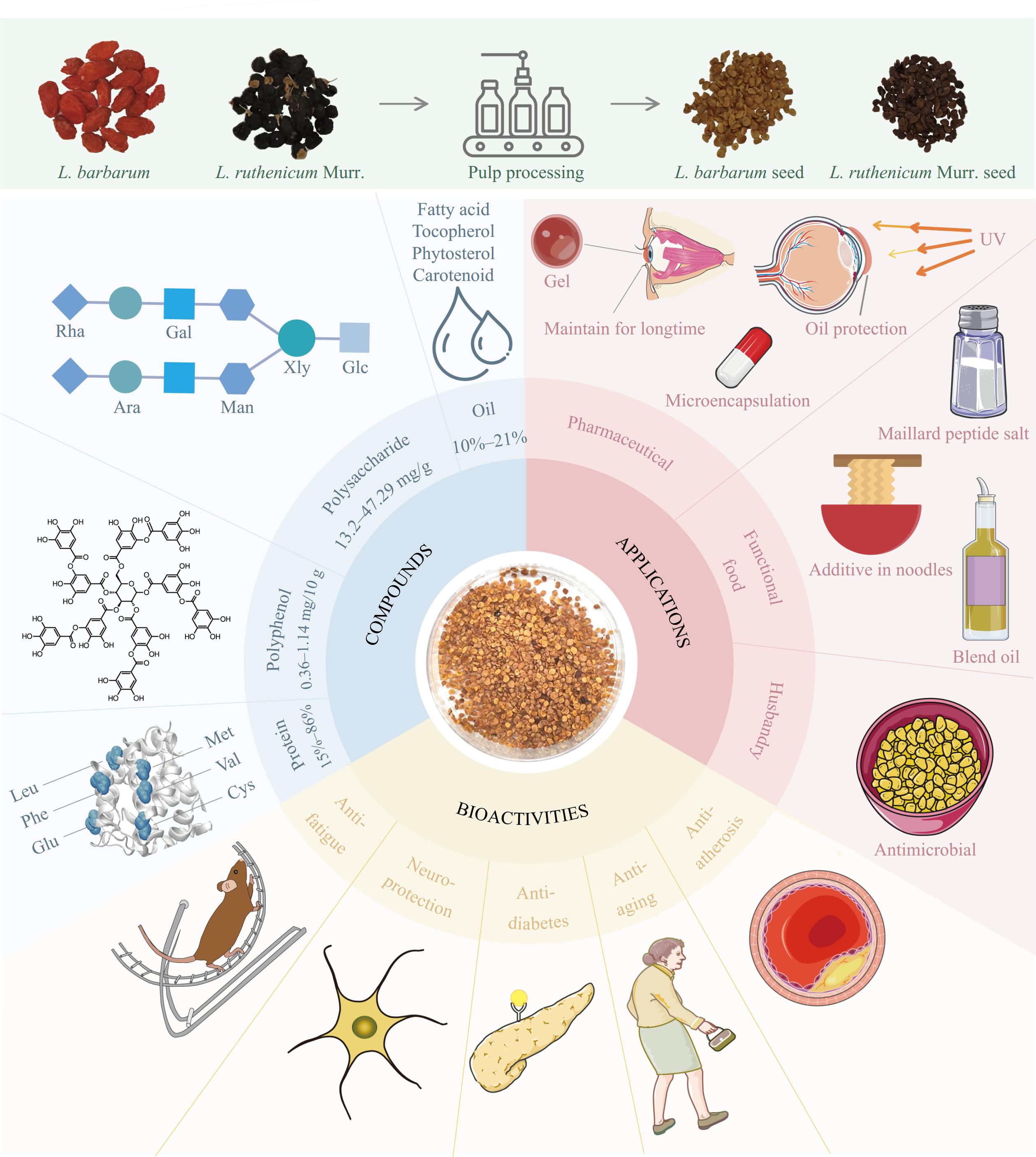

Lycium seeds, a by-product of Lycium fruit processing, are rich in bioactive compounds and hold significant health potential. This review summarizes and analyzes existing research, finding substantial progress in understanding the extraction of nutritional components, health benefits, and applications, as shown in Fig. 3. However, several challenges and opportunities remain to be explored.

Figure 3.

The summary of composition, biological activity, and application of Lycium seeds. Rha – Rhamnose; Gal – Galactose; Xyl – Xylose; Glc – Glucose; Ara – Arabinose; Man – Mannose; Leu – Leucine; Phe – Phenylalanine; Glu - Glutamic acid; Met – Methionine; Val – Valine; Cys – Cysteine; UV - Ultraviolet.

Extraction methods have been the subject of considerable research, as different methods can be selected to specifically maximize the extraction of various nutrients. This review explores the differences among Lycium seed varieties and examines how optimizing extraction methods can affect both yield and bioactivity. Despite the progress made in current extraction technologies, several issues still require further investigation. Firstly, extraction methods vary in efficiency when isolating bioactive compounds, leading to the loss of key bioactive compounds and reduced bioavailability[116]. Secondly, the complex composition of Lycium seeds and the difficulty in controlling extraction parameters pose challenges to achieving large-scale industrial production, both technically and financially[117]. The inconsistency in extraction outcomes affects not only the yield but also the effectiveness of bioactive compound extraction, creating a significant barrier to industrial applications[35].

Existing research on the functions of Lycium seeds has primarily focused on animals, demonstrating its health benefits. However, further rigorous clinical trials are necessary to confirm the efficacy of Lycium seed extracts in humans. While several clinical studies have established the health benefits of Lycium fruits, such as improved energy levels, sleep quality, and mental focus through Lycium juice, clinical studies on Lycium seeds specifically are lacking[118]. For instance, formulations containing Lycium fruit have shown potential for liver health improvement in heavy drinkers and skin hydration and wrinkle reduction in eye serums[119,120]. Nevertheless, similar studies on Lycium seeds are essential, as are studies validating their safety and efficacy in clinical applications. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms underlying these health benefits require further investigation, particularly for bioactive components such as proteins and polyphenols. Their specific molecular mechanisms and effects still need to be explored using advanced technologies such as metabolomics[35].

Future research should prioritize efficient and eco-friendly extraction technologies to enhance yield and bioactivity while minimizing environmental impact. Establishing standardized industrial processes is crucial to ensure consistent product quality, safety, and efficacy. Lastly, evaluating the environmental and economic impacts of Lycium seed production and utilization will be vital to optimizing agricultural and industrial practices, reducing resource waste, and fostering sustainable development.

-

This review shows that Lycium seeds are a rich source of bioactive compounds with several potential health benefits. Research progress has been made in understanding the nutritional components, extraction methods, and potential health applications of Lycium seeds. However, key challenges such as inconsistent extraction outcomes, limited human studies, and the need for industrial optimization must be addressed. The integration of innovative extraction methods, rigorous clinical validation, and sustainable industrial practices will be pivotal for fully realizing the value of Lycium seeds in food, pharmaceutical, and husbandry industries.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32422069), China Agricultural University-Cornell University dual-degree program undergraduate research fund.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Li Y: wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figs 1 & 2, the graphical abstract, and Tables 3 & 4; Shen R: wrote the main manuscript text prepared Fig. 1, Tables 1 & 2; Wang S: participated in literature analysis and contributed to the main manuscript text; Zhang J: contributed to the manuscript text and assisted with revisions; Deng J: performed the final review and editing of the manuscript; Liu Y: provided critical revisions to the structure and content of the manuscript and conducted proofreading; Sun Q: performed the final review and editing of the manuscript; Yang H: supervised and guided the entire writing process, provided academic support, and performed the final review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Y, Shen R, Wang S, Zhang J, Deng J, et al. 2025. A comprehensive review on bioactive compounds from Lycium seeds: extraction, characterization, bioactivities, and applications. Food Innovation and Advances 4(2): 212−227 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0020

A comprehensive review on bioactive compounds from Lycium seeds: extraction, characterization, bioactivities, and applications

- Received: 10 November 2024

- Revised: 28 February 2025

- Accepted: 05 March 2025

- Published online: 30 May 2025

Abstract: Lycium, known for its medicinal, nutritional, and food applications, is widely utilized in various food, pharmaceutical, and health-related industries. However, Lycium seeds as a byproduct of Lycium processing are still not fully utilized, resulting in a waste of green resources. About 20-25% of Lycium seeds are wasted due to inefficient disposal practices. In this work, the bioactive compounds from Lycium seeds, including oils, phenolic compounds, polysaccharides, proteins, and other components, along with the methods used for their extraction are summarized. Differences in extraction techniques, yields, and bioactivities are analyzed to provide insights into optimizing these processes. The review also highlights the diverse bioactivities of Lycium seed extracts, such as anti-fatigue, neuroprotective, anti-diabetic, anti-aging, and anti-atherosclerotic effects, delving into their functional mechanisms. Furthermore, it explores the potential applications of Lycium seed-derived bioactive compounds in pharmaceuticals, functional foods, and animal husbandry, emphasizing their value in enhancing food processing practices. This comprehensive review aims to bridge the knowledge gap, offering theoretical support for the broader application of Lycium seeds in industries such as food, healthcare, and agriculture.

-

Key words:

- Lycium seeds /

- Extraction /

- Bioactive compounds /

- Biological activities /

- Applications