-

Harmful microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoan parasites, can contaminate food-contact surfaces[1], leading to the formation of biofilm communities of microbes encased in a self-produced matrix that adheres to surfaces[2−5]. These biofilms provide a protective barrier that makes microorganisms more resistant to cleaning and disinfection efforts[4]. When biofilms form on food-contact surfaces, they can persistently harbor pathogens that contaminate food products, thereby increasing the risk of disease transmission to consumers[6]. This contamination can result in foodborne illnesses, which are a significant public health concern due to the difficulty in eradicating biofilms once established. Biofilms pose a significant challenge in food packaging due to their resistance to conventional cleaning and sanitization methods[7]. Antimicrobial packaging addresses this issue by incorporating substances that inhibit or kill microorganisms, thereby preventing biofilm formation on food surfaces.

Antimicrobial packaging is a revolutionary innovation in the food packaging industry aimed at enhancing food safety and extending the shelf life of perishable products[8]. The primary function of antimicrobial packaging is to inhibit or kill pathogenic microorganisms that can spoil food and cause foodborne illnesses. This technology incorporates antimicrobial agents into packaging materials, creating an active defense against microbial contamination[9]. The significance of antimicrobial packaging in food safety cannot be overstated, as it addresses a critical challenge in the food supply chain: maintaining the quality and safety of food products from production to consumption. Food safety is a paramount concern for consumers, producers, and regulators[10]. Contaminated food can lead to severe health issues, ranging from mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening conditions. Traditional packaging methods primarily serve as barriers that protect food from external contamination. However, they do not actively combat the growth of microorganisms that may already be present in the food. Antimicrobial packaging fills this gap by providing an additional layer of protection. This review aimed to summarize antimicrobial agents, packaging materials, methods of incorporation, strategies, biodegradability, and smart innovations in antimicrobial packaging.

-

Antimicrobial packaging works through various mechanisms depending on the type of antimicrobial agents used. These agents can be integrated into the packaging material, coated on the surface, or embedded in a carrier matrix. The active agents then migrate to the surface of the packaging or the food product, where they exert their antimicrobial effects[11]. Common mechanisms include the disruption of microbial cell membranes, interference with cellular metabolism, and inhibition of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) replication (Fig. 1).

One of the primary mechanisms by which antimicrobial agents' function is by disrupting the cell membranes of microorganisms. This disruption can cause cell lysis, leakage of cellular contents, and ultimately, cell death. For instance, essential oils such as those derived from oregano and thyme contain compounds like carvacrol and thymol, which have been shown to insert themselves into microbial cell membranes, creating pores that lead to cell leakage and death[12−14]. Antimicrobial agents can interfere with the metabolic processes of microorganisms. This inhibition can occur through the disruption of enzyme activity, interference with nutrient uptake, or disruption of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. Silver nanoparticles, for example, can bind to thiol groups in enzymes and proteins, inhibiting their function and leading to the disruption of cellular respiration and other metabolic activities[15]. This mechanism is particularly effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains. Another significant mechanism is the interference with DNA replication and protein synthesis. Some antimicrobial agents can bind to DNA or ribonucleic acid (RNA), preventing the replication and transcription processes necessary for cell division and function. Chitosan, a natural polymer derived from chitin, has been shown to bind to bacterial DNA, inhibiting its replication and leading to cell death[16]. This mechanism is particularly useful in targeting rapidly dividing cells, such as bacteria in the lag phase of growth. Antimicrobial agents can also disrupt the biofilm matrix on food surfaces by various mechanisms that target the structural integrity and functionality of biofilms. These agents can inhibit biofilm formation by preventing bacterial adhesion and growth, dismantling the extracellular matrix, or disrupting multiple biological pathways[17−20]. Natural antimicrobial compounds like usnic acid inhibit bacterial biofilm formation on polymer surfaces by interfering with the biofilm slime matrix[21].

Among the various antimicrobial agents used in packaging, plant extracts have garnered significant attention due to their natural origin and potent antifungal, antibacterial, and antibiofilm properties[22−24]. Plant extracts, especially essential oils and polyphenols are rich in bioactive compounds that can inhibit a broad spectrum of microorganisms. These natural agents are preferred over synthetic chemicals because they are biodegradable, non-toxic, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory authorities.

Essential oils derived from plants such as oregano, thyme, and clove are known for their strong antimicrobial activity. These oils contain compounds like carvacrol, thymol, and eugenol, which have been proven to disrupt microbial cell walls and interfere with their metabolic processes. Studies have shown that packaging films incorporated with essential oils can effectively inhibit the growth of pathogenic microorganisms[25]. Polyphenols are another group of plant-derived compounds with significant antimicrobial properties. Tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids can damage microbial cell membranes and bind to microbial proteins, leading to the inhibition of enzyme activity and biofilm formation[26]. Packaging materials infused with polyphenols from sources like green tea, grapes, and olives have demonstrated effectiveness in prolonging the shelf life of food products by preventing microbial growth[27]. Jailani et al.[28] examined the capacity of tannic acid, a compound commonly found in woody plants, to selectively hinder the growth and generation of biofilms by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Tannic acid exhibited antibacterial properties and effectively decreased the production of biofilm on both polystyrene surfaces and the roots of Raphanus sativus, as confirmed by 3D bright-field and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) pictures. In addition, tannic acid had a strong downregulating effect on the exoR gene, which is essential for the adherence of cells to surfaces. Zhao et al.[29] investigated how tea catechin extracts affected the growth of three different methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains as well as the formation of biofilms on their surfaces. According to the findings, tea catechin extracts were able to effectively inhibit the growth of MRSA strains, and the minimum inhibitory concentration of tea catechin extracts against these MRSA strains was 0.1 g/L. The tea catechin extracts prevented the development of biofilms by these strains in a dose-dependent manner, which was assessed using a colorimetric approach. Additionally, the expression of fnbA and icaBC was reduced in the strains when tea catechin extracts were used. Other antimicrobial agents used in food packaging are organic acids, enzymes, peptides, and nanomaterials (Table 1).

Table 1. Antimicrobial agents are commonly used in food packaging.

Type Antimicrobial agents Efficacy Ref. Plant extract Olive leaf extract Olive leaf extract of Gemlik possesses the highest levels of oleuropein and rutin contents. It shows the highest zone of inhibition against E. coli (16.33 ± 0.33 mm) and against Salmonella typhimurium (16.00 ± 0.00 mm). The studies of thickness, water vapor transmission rate, oxygen transmission rate and antibacterial potential of the packaging sheets prove that olive leaf extract is an effective active functional food packaging. [30] Adina rubella extract Fermented Adina rubella extract, a flowering shrub, for 9 d can inhibit the growth of Listeria monocytogenes by destroying the structure of the cell wall when incorporated into food film, showing great potential for pork packaging. [31] Cannabis sativa L.

seeds extract2.5 [wt%] Cannabis sativa L. seeds extract incorporated into apple and citrus-based pectin food film successfully inhibit S. aureus, S. typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes. Cannabidiol, a phenolic compound found in the seed may alter cell membrane permeability, inhibit RNA synthesis, and inactivate bacterial proteins, giving the extract antibacterial properties. [32] Organic acid Lactic acid Polyvinyl alcohol film incorporated with lactic acid (PVA/LA) exhibits the highest bacterial inhibition, which is largely due to its capacity to modify the local pH and alter the permeability of the microbial layer by disrupting bacteria–substrate interaction. The composite film has attractive properties and can be considered as a food packaging material with low environmental impact based on polyvinyl alcohol. [33] Sorbic acid Sorbic acid-incorporated polypropylene (PP) films for packaging fresh yufka dough, a Turkish flatbread, regulate the moisture content of the dough, preventing it from being spoiled. At 6% sorbic acid concentration, the film decreases the log cycles of E. coli and S. aureus and shows a greater inhibition zone against Aspergillus niger (6.70 ± 0.48 mm). [34] Citric acid Keratin from chicken feathers reinforced with citric acid-modified cellulose nanocrystals (CNC-CA) film possesses a promising antimicrobial activity against E. coli and S. aureus. The film has a great tensile strength and elongation at a break of 209%, aside from being biodegradable, successfully extends the shelf-life of blueberries for 5 d at room temperature. [35] Enzyme Lysozyme Chitosan-lysozyme composite films and coatings remarkably decrease the growth of L. monocytogenes, E. coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and mold in mozzarella cheese than laminated films and coatings. [36] Nanoenzyme Biomimetic artificial bovine serum albumin (BSA) nanoenzyme chelated with copper ions (CuBSA) successfully kills more than 95% viable bacteria. The nanoenzyme delays the oxidative browning of freshly cut fruit slices and prevents the growth of bacteria on figs and apples. [37] Phage endolysin The incorporation of endolysin from E. coli EO157:H7 phage JN01 and eucalyptus leaf essential oil liposome into gelatin packaging is effective against E. coli O157:H7 and S. enteritidis. These suggest that this packaging successfully prevents microbial growth on fresh Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) that are prone to microbial spoilage during cold storage. [38] Peptides Bacteriocin When used as Minas Frescal cream cheese packaging, a chitosan/agar-agar bioplastic film incorporated with bacteriocin contributes to the increase of microbiological stability, showing a reduction of 2.62 log CFU/g, contributing a gradual release of the active compound into the food during the storage time. [39] Nisin Nisin, an antimicrobial peptide from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis that is loaded into zein/polyethylene oxide (PEO) film has a significant increase in the antibacterial activity against S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, S. typhimurium, and E. coli, which is probably due to the membrane permeability alteration. The strong antibacterial activity of the fabricated nisin-loaded electrospun mats successfully prolongs the shelf-life of chicken breast in storage, proven as a promising antibacterial packaging material. [40] Casein Milk-derived antimicrobial peptides αs2-casein151-181 and αs2-casein182-207, are incorporated into whey protein-based edible films for cheese packaging. They have a similar antibacterial activity against B. subtilis and a much greater activity against E. coli when compared to nisin-containing cheese packaging films. It is a promising packaging for soft cheese, inhibiting yeasts and molds as well as controlling the growth of other psychotrophic bacteria at refrigerated temperatures. [41] Nanomaterial A combination of

silver and zinc oxide nanoparticlesThe antimicrobial efficiency of starch/PBAT nanocomposite films with AgNPs and ZnONPs reaches more than 95% within 3 h of contact. [42] Nanocellulose Corn cob nanocellulose combination with essential oil that is incorporated into polylactic acid (PLA) film, reinforces its matrix and prevents food with high water content from being spoiled. When tested against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cubense, the nanocellulose composite bags completely inhibit the mycelial growth. [43] Titanium carbide

MXene nanofillersTi3C2 MXene nanofillers-reinforced chitosan/gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) composite films (CGPF-Mxs) at a concentration of 0.75% alters the permeability of cell membrane by binding the amino ions on chitosan with teichoic acid and lipopolysaccharide in the cell wall. It has an inhibition rate of up to 98.53% against S. aureus and 82.91% against E. coli and could be considered as packaging for cooked meat products. [44] Antimicrobial agents in food packaging offer diverse advantages and disadvantages based on their characteristics. Plant extracts, such as essential oils, are natural, biodegradable, and have broad-spectrum activity but may vary in efficacy and affect packaging stability. Organic acids, like citric and lactic acids, are effective and affordable, but their dependence on low pH can alter food taste and texture. Enzymes, being highly specific, limit spoilage with minimal impact on food properties, but are costly and sensitive to environmental factors. Bacteriocins, such as nisin, are stable and safe but are limited in activity to certain bacteria, risking microbial resistance. Nanomaterials, like silver nanoparticles, are broad-spectrum and durable but face regulatory hurdles and potential toxicity concerns. Thus, selecting the right agent involves balancing antimicrobial efficacy, material compatibility, cost, and consumer safety.

-

Food packaging materials play a crucial role in preserving the quality and safety of food products. Among the most commonly used materials are plastics, metals, glass, and paper, each offering unique properties and benefits for various applications. According to Marsh & Bugusu[45], traditional food packaging materials include glass, metals such as aluminium, tinplate, and tin-free steel, which are valued for their excellent barrier properties against moisture, gases, and light, thereby extending the shelf life of food products significantly.

Plastics are widely used due to their versatility, lightweight, and cost-effectiveness. They can be tailored to provide specific barrier properties and mechanical strengths. However, the environmental impact of plastic waste has driven research towards more sustainable options. Common types include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Recent studies highlight the use of biodegradable and bio-based plastics, which decompose under natural conditions and reduce the environmental footprint. Jiang et al.[46] discussed the advancements in active materials for food packaging, including oxygen scavengers and antimicrobial agents incorporated into plastic matrices, which actively enhance the preservation of food by inhibiting microbial growth and reducing oxidation.

Glass remains a preferred material for packaging beverages and certain food products due to its inert nature, impermeability, and recyclability. It does not react with food contents, ensuring the preservation of flavor and quality. Glass also provides an excellent barrier against oxygen and other gases, preventing spoilage and extending shelf life. Its transparency allows consumers to see the product, enhancing appeal and trust. Additionally, glass is 100% recyclable and can be reused indefinitely without losing quality, aligning with growing consumer and regulatory demands for sustainable packaging solutions. In 2014, Makwana et al.[47] demonstrated that glass coated with nano-encapsulated cinnamaldehyde may be used as an active packaging material in preserving liquid foods.

Clamshell packaging, a type of packaging that consists of two halves joined by a hinge, is widely used for its convenience and protective properties. It is commonly made from plastic materials such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which offer clarity and durability. Clamshells are used for fresh produce, bakery items, and ready-to-eat meals due to their convenience and protection. A key study by Kao et al.[48] investigated the incorporation of calcined waste clamshell (CCS) powder into polyethylene (PE) bags to enhance their bacteriostatic properties. The findings revealed that the addition of CCS powder prolonged the shelf life of the packaged food by retaining its CaO bacteriostatic efficacy. This innovative approach highlights the potential of using waste materials to improve the functionality of clamshell packaging, particularly in the food industry.

When selecting materials for antimicrobial packaging, plastics, glass, and clamshells each have distinct advantages and drawbacks. Plastics are cost-effective, lightweight, and versatile, making them widely used, but they have a significant environmental impact due to non-biodegradability and reliance on fossil fuels. Glass is inert, recyclable, and offers excellent preservation by providing an impermeable barrier, but it is heavier, more expensive, and energy-intensive to produce and transport. Clamshells, often made from biodegradable or recyclable materials, strike a balance between cost and environmental impact, offering moderate preservation but sometimes lacking the durability of plastics or glass. For antimicrobial packaging, the choice depends on balancing cost, environmental sustainability, and the required preservation efficacy, with plastics being economical but less eco-friendly, glass offering superior preservation at higher costs, and clamshells providing a middle ground with better environmental credentials.

-

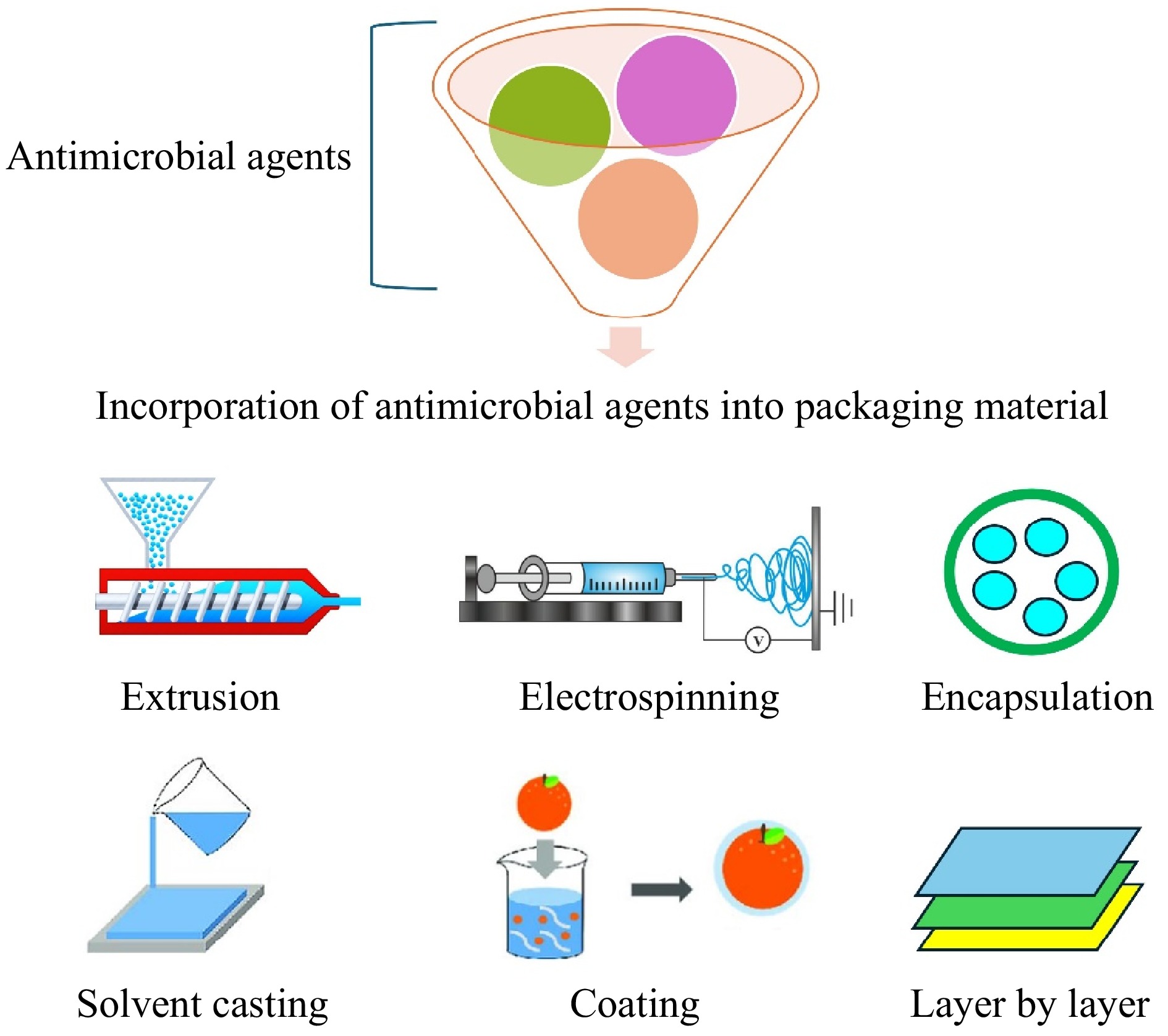

The integration of plant materials into packaging material is a rapidly advancing field aimed at developing sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives to traditional plastic packaging. These methods focus on incorporating natural compounds and fibers derived from plants to enhance the antimicrobial properties, biodegradability, and overall functionality of packaging materials. The incorporation of plant extracts into packaging materials can be achieved through several methods including surface coating, solvent casting, extrusion, electrospinning, layer-by-layer, and encapsulation[49,50]. Figure 2 summarizes those common methods.

Figure 2.

Different methods are commonly used for incorporating antimicrobial agents into packaging material for food packaging applications.

Plant extracts can be applied as a coating on the surface of packaging materials. The surface coating method is particularly useful for creating a strong antimicrobial surface layer that can come into direct contact with the food product[51]. Encapsulation techniques, such as nanoencapsulation, can be used to protect plant extracts from degradation and control their release over time. This method enhances the stability and efficacy of antimicrobial agents[11]. Extrusion is a widely used method for incorporating plant materials into packaging. This process involves melting and shaping materials through a dye, allowing uniform distribution of antimicrobial agents within the polymer matrix[52]. Solvent casting is another common technique where plant extracts are dissolved in a solvent and mixed with a polymer solution. The mixture is then cast onto a surface and allowed to evaporate, forming a thin film[53]. This method is particularly useful for incorporating heat-sensitive plant extracts that might degrade during extrusion. Electrospinning is a technique that uses electrical forces to produce fine fibers from a polymer solution. Plant extracts can be incorporated into these fibers, creating packaging materials with enhanced functionalities[54]. This method is particularly advantageous for creating nanoscale fibers with high surface area, which can improve the release and effectiveness of antimicrobial agents. Layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly is a more advanced method where multiple layers of plant extracts and polymers are alternately deposited to build a multilayer structure[55].

In 2019, Radusin and colleagues[56] developed innovative active films composed of polylactide (PLA) with a 10 wt% extract of Allium ursinum (AU), commonly known as wild garlic, using electrospinning technology. The electrospinning process produced fibers within the 1–2 μm range, displaying a beaded morphology, indicating that the AU extract was predominantly encapsulated in specific fiber regions. These electrospun mats were subsequently annealed at 135°C to form continuous films suitable for active packaging applications. Examination of the film cross-sections showed that the AU extract was embedded within the PLA matrix as micro-sized droplets. The addition of the AU extract was found to plasticize the PLA matrix and reduce its degree of crystallinity by interfering with the PLA chains' ability to fold into a crystalline structure. The electrospun PLA films containing the AU extract exhibited significant antimicrobial activity against foodborne bacteria.

Ordon et al.[57] developed active low-density polyethylene (LDPE) films incorporating a blend of CO2 extracts from rosemary, raspberry, and pomegranate using an extrusion process. The study demonstrated that these LDPE films inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis. The integration of CO2 extracts into the polymer matrix altered its mechanical properties and enhanced its UV radiation barrier capabilities. These modified PE/CO2 extract films are promising candidates for functional food packaging materials due to their antibacterial and antiviral properties.

-

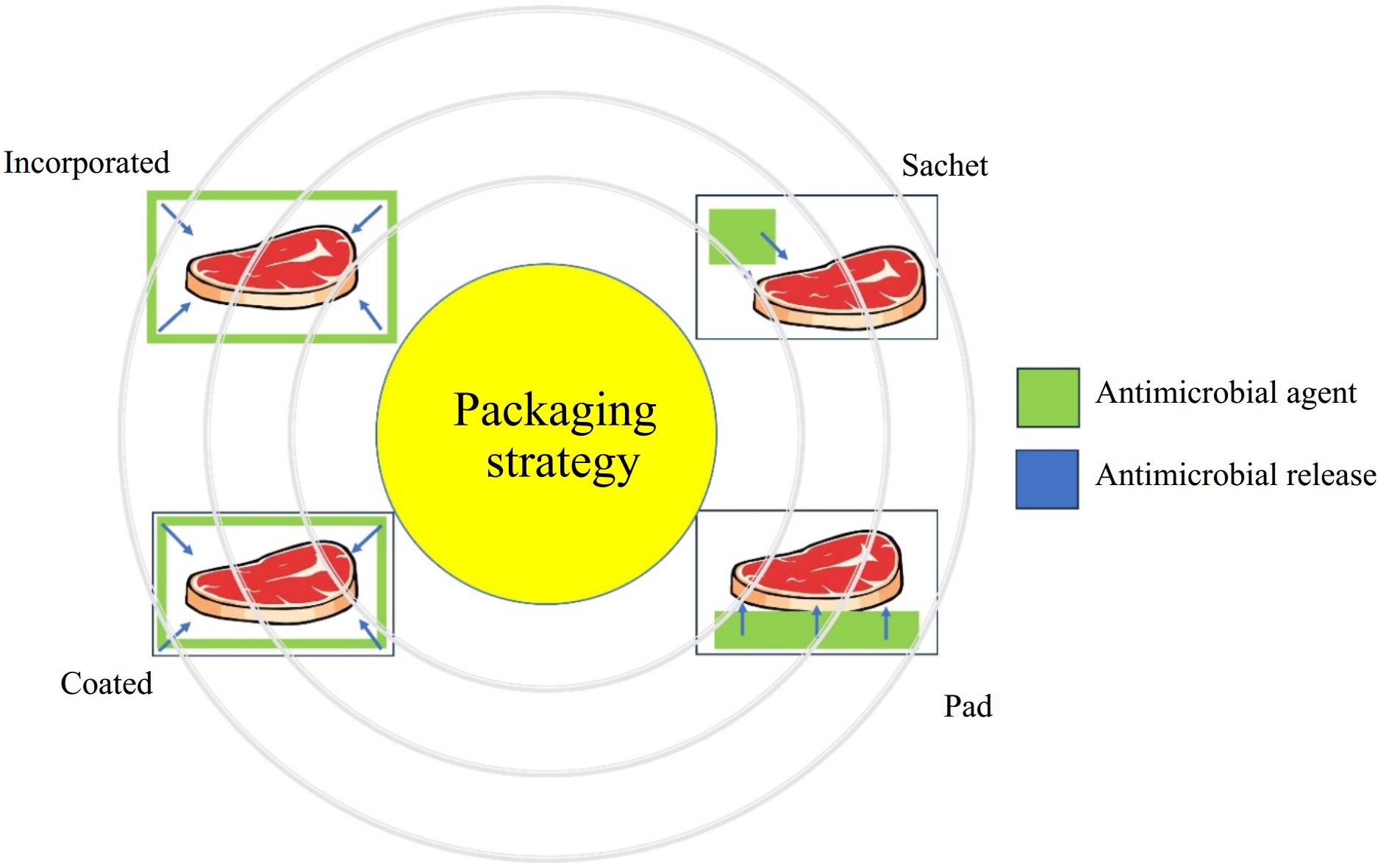

Antimicrobial packaging employs various strategies to prevent microbial growth and extend food shelf-life (Fig. 3). The antimicrobial agents can be incorporated into the polymeric film, coated onto the film, released from the sachet, and in direct contact with pads[58]. Incorporated systems blend antimicrobial agents into the packaging material, allowing for a controlled and sustained release, though compatibility with polymers can be a challenge. Coated systems apply antimicrobial substances onto the packaging surface, providing direct contact and rapid efficacy, although their durability can decrease over time. Pads infused with antimicrobials are commonly placed under perishable foods like meats, where they absorb moisture and release active agents, creating a localized protective environment. Sachets, often containing volatile compounds like ethanol or essential oils, release active vapors into the package headspace, which is particularly effective for non-contact preservation. Each approach is tailored to specific food types and conditions, balancing factors like targeted microbial inhibition, material compatibility, and ease of integration.

Antimicrobial packaging offers diverse strategies to address food safety and shelf-life extension, but each has inherent strengths and limitations. Incorporated systems ensure sustained antimicrobial activity but face challenges with polymer compatibility and uniform distribution. Coated systems provide immediate and effective action against surface contamination but may degrade or lose efficacy with extended use. Antimicrobial pads, particularly beneficial for high-moisture foods like meat, create targeted protective zones but are limited to localized effects and require physical contact. Sachets, on the other hand, excel in preserving dry or sealed products through vapor release but depend on precise environmental control for consistent performance. While these approaches effectively combat microbial growth, achieving a balance between practicality, scalability, and material biodegradability remains critical. Developing multifunctional, eco-friendly solutions to address these challenges can further enhance their utility across the food industry.

-

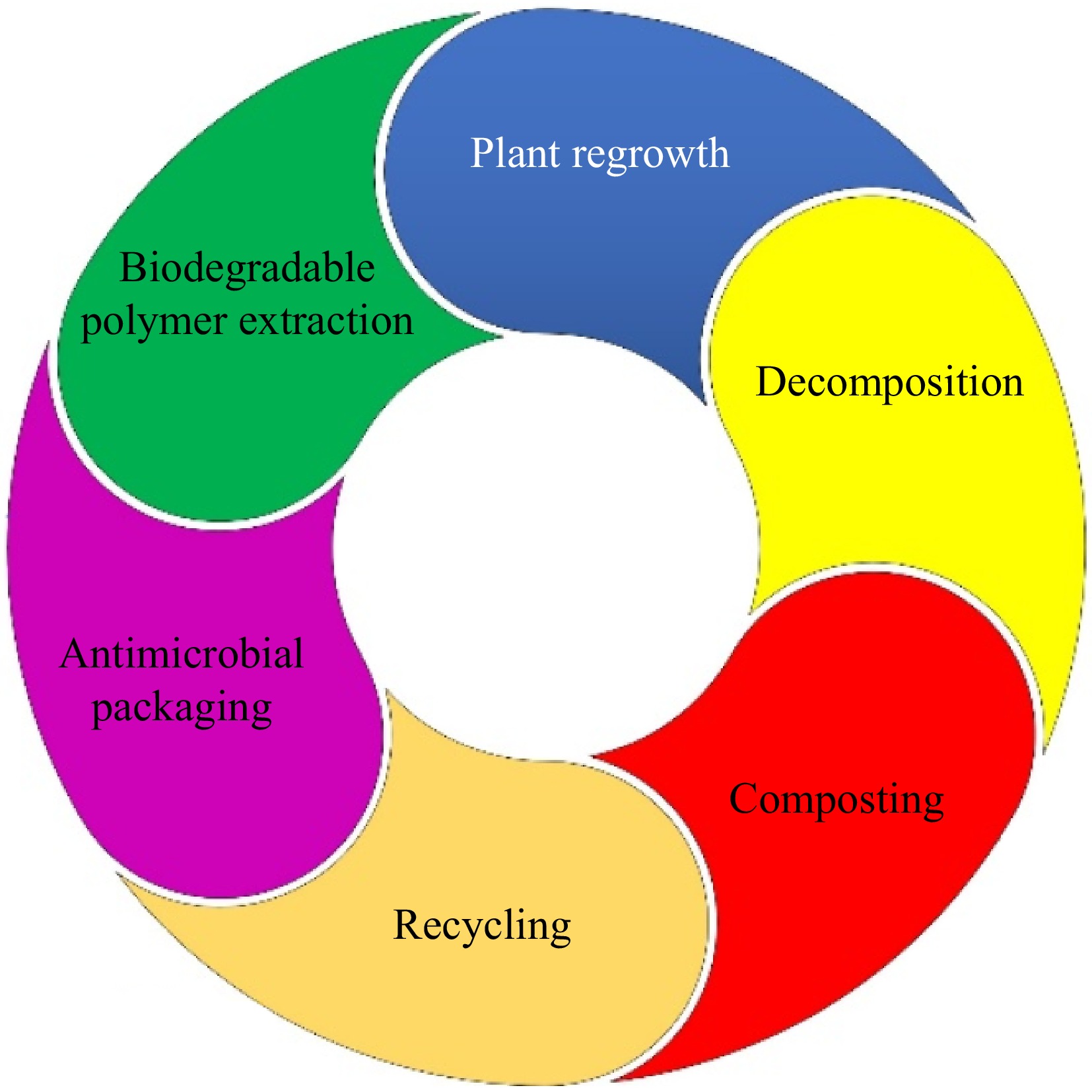

Antimicrobial packaging films are increasingly utilized in the food industry to extend shelf life and reduce spoilage caused by microorganisms[8,9]. The incorporation of biodegradable materials into these films not only addresses food safety concerns but also mitigates environmental issues associated with plastic waste. Research indicates that the biodegradation rates of antimicrobial films vary based on their composition. For example, antimicrobial packaging incorporated with carvacrol[59] and chitosan requires 45 and 7 d[60], respectively. Despite the advantages of biodegradable antimicrobial packaging, there are several challenges such as mechanical and barrier properties. Many biodegradable polymers exhibit inferior mechanical properties compared to traditional plastics[61], which limits their application in demanding environments. Enhancing the oxygen and moisture barrier properties is crucial for maintaining food quality while ensuring biodegradability. These include nanotechnology, chain architecture modification, melt blending, multi-layer co-extrusion, and surface coating[62]. The sustainability process begins with utilizing plants, particularly agricultural waste, as a source of raw materials for biopolymer production (Fig. 4).

In this process, plants provide starches, cellulose, or other biopolymers that are extracted using environmentally friendly methods. The extracted biopolymers are then incorporated with antimicrobial agents, such as essential oils or natural extracts, to produce biodegradable antimicrobial packaging that enhances food safety by extending shelf life and reducing spoilage. Once the packaging is used, it can undergo recycling if the structure allows direct composting in industrial or natural systems. In decomposition, microorganisms break down the material into carbon dioxide, water, and nutrients, which enrich the soil. This fertile soil supports plant regrowth, completing the cycle and reducing reliance on synthetic inputs. Each step has critical benefits and challenges. Biopolymer extraction adds value to agricultural waste but requires efficient technologies to minimize energy use. Antimicrobial packaging reduces food waste but depends on ensuring compatibility between polymers and antimicrobial agents. Recycling and composting offer eco-friendly disposal but require robust waste management systems. Biodegradability ensures environmental safety but necessitates consumer awareness and adoption. Overall, these steps highlight the pivotal role of biodegradable antimicrobial packaging in creating sustainable food systems and mitigating plastic pollution.

-

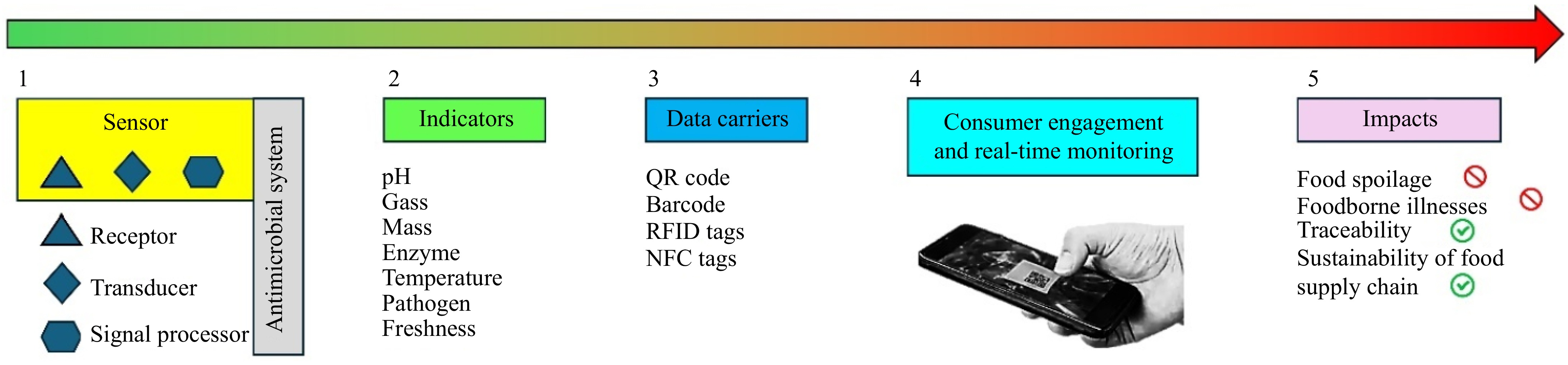

Future research in antimicrobial packaging is likely to focus on optimizing the incorporation methods of plant extracts to enhance their stability and efficacy. Exploring new plant sources and bioactive compounds can expand the range of antimicrobial agents available for use in packaging. Innovations such as the development of smart packaging materials that can respond to environmental changes and release antimicrobial agents on demand are promising. Intelligent controlled-release packaging can synchronize the release of active substances with food preservation needs by sensing stimuli like enzymes, pH, humidity, temperature, and light[63]. These stimuli can be the properties of the headspace inside the package or the food or storage conditions. In 2021, Wang et al.[64] developed a pectin-based antimicrobial hydrogel infused with cinnamon essential oil, designed to serve as an inner packaging alternative to commercial alcoholic freshness cards. This hydrogel effectively absorbed moisture generated by bread, facilitating the accelerated release of cinnamon essential oil through the expanded gel pore walls, thereby significantly suppressing mold growth. Meanwhile, Min et al.[65] designed an antibacterial nanofiber membrane utilizing the enzyme hydrolysis principle to respond to pectinase stimulation, which was tested on citrus artificially inoculated with pathogens. This membrane demonstrated the ability to intelligently detect Aspergillus niger and precisely release thymol to suppress its growth. Song et al.[66] provided insights into bio-based smart active packaging, which incorporates antibacterial agents, antioxidants, and other active compounds into biodegradable materials. These packaging materials not only respond to environmental changes but also enhance the sustainability of packaging solutions.

Smart antimicrobial packaging also integrates advanced technologies to enhance food preservation and safety by controlling the release of antimicrobial agents. This innovative packaging can utilize slow-release mechanisms, where antimicrobial compounds are gradually released, thereby maintaining their effectiveness over extended periods. For example, the addition of glyoxal enables a controlled release of lysozyme, effectively modulating its antimicrobial activity against Micrococcus lysodeikticus and Staphylococcus aureus[67]. The cross-linking process with glyoxal, a small, dialdehyde molecule, forms an insoluble caseinate network at pHs close to the isoelectric point of caseinate (pH 4.6). It is capable of gradually releasing enzymatic activity. A slower release of gallic acid is also observed after plasma treatment[68]. The prepared gallic acid-coated low-density polyethylene (LDPE) antimicrobial film exhibits strong activity against E. coli and S. aureus.

Recent advances in smart and active biodegradable packaging materials include the development of sensors that indicate changes in food attributes through measurable color changes[69−71]. Chemical sensors and biosensors are the most widely studied in food packaging. Chemical sensors are mostly based on electrochemical or optical signal transduction methods to detect the presence of volatile chemicals and gases[72]. On the other hand, biosensors are based on organisms or substances in organisms, such as enzymes and DNA[73]. The impact of smart antimicrobial packaging is summarized in Fig. 5. Nevertheless, intelligent equipment such as sensors tends to be intricate and expensive.

-

Smart antimicrobial packaging often entails elevated initial expenses relative to conventional packaging, attributable to the integration of modern materials, antimicrobial agents, and technology such as controlled-release systems, indications, or sensors[73]. These components need specialized manufacturing procedures, research, and development, resulting in elevated costs. Smart antimicrobial packaging may provide enduring cost savings by substantially prolonging product shelf life, decreasing food spoiling, and lessening the need for additives or regular restocking[74]. Moreover, it may improve food safety by effectively suppressing microbial proliferation, possibly reducing healthcare expenditures related to foodborne diseases. Although conventional packaging is less expensive initially, its passive characteristics often result in elevated total expenses owing to food loss and safety concerns, making smart antimicrobial packaging a cost-efficient and sustainable alternative over time.

There are several technical and logistical challenges involved in turning antimicrobial packaging from a pipedream when first being test-run in the lab into an industrial-scale reality. When antimicrobial agents are incorporated into packaging materials, production sometimes calls for specialized equipment and processes like extrusion, coating, or encapsulation[49,50]. These processes have to be optimized so that the antimicrobial agents are evenly dispersed and give consistent results. Should the antimicrobial agents lose their potency or break down in other ways before the expiration date, either temperature or humidity can present challenges to their stability in this period of storage.

Regulations from governing bodies are important for guaranteeing antimicrobial food packaging is secure and effective. However, regulatory agencies, such as the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) as well as EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), require quite wide-ranging toxicological data under certain guidelines, which may be time-consuming along expensive for production. Antimicrobial packaging regulations vary by region[75], which creates difficulty for manufacturers seeking to market their products worldwide. The absence of harmonized standards may result in certain delays in approval as well as elevated compliance costs. The implementation of completely non-biodegradable or non-recyclable materials in antimicrobial packaging may potentially conflict with ecological regulations strictly targeted at reducing plastic waste. Thus, manufacturers must balance antimicrobial efficacy with sustainability to comply with these regulations.

-

Antimicrobial packaging represents a transformative approach to food preservation, using advanced mechanisms in addition to revolutionary materials plus smart technologies for the enhancement of food safety, extending shelf life, and reducing waste. These packaging systems actively inhibit microbial growth by incorporating antimicrobial agents such as oils, nanoparticles, or organic acids through coating, encapsulation, or immobilization methods, dealing with critical challenges in food spoilage and contamination. Approaches such as controlled release, biodegradability, and combining with smart innovations also enhance their functionality and sustainability. Antimicrobial packaging improves food quality and safety and strengthens global sustainability aims by lessening the necessity for chemical preservatives and cutting down on food waste. As research persistently continues to address notably important challenges about scalability, regulatory compliance, and economic feasibility, antimicrobial packaging holds remarkably huge potential for transforming the food industry, guaranteeing a safer, more sustainable future in food preservation and distribution.

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yahya MFZR, Jalil MTM; data collection, draft manuscript preparation: Nor AHA, Yahya MFZR; analysis and review: Seow EK, Idris MHM, Yahya MFZR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this review as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors would like to thank Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia for its research facilities.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Nor AHA, Jalil MTM, Seow EK, Idris MHM, Yahya MFZR. 2025. Antimicrobial packaging: mechanisms, materials, incorporation methods, strategies, biodegradability, and smart innovations – a comprehensive review. Food Materials Research 5: e009 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0008

Antimicrobial packaging: mechanisms, materials, incorporation methods, strategies, biodegradability, and smart innovations – a comprehensive review

- Received: 21 December 2024

- Revised: 11 April 2025

- Accepted: 26 May 2025

- Published online: 30 June 2025

Abstract: The increasing demand for sustainable food preservation solutions has highlighted the potential of antimicrobial packaging to extend shelf life and enhance food safety. Conventional packaging materials contribute to environmental pollution, while microbial contamination continues to threaten food security. This review addresses these challenges by exploring antimicrobial packaging systems combining active agents with biodegradable polymers to tackle foodborne pathogens and environmental pollution. Antimicrobial agents, including natural extracts, organic acids, enzymes, bacteriocins, and nanomaterials, which inhibit microbial growth and alter cell membrane permeability, are commonly used in antimicrobial packaging. Incorporation techniques like coating, extrusion, and electrospinning are evaluated for their role in optimizing antimicrobial functionality. Strategies to balance functionality with environmental impact are critically evaluated, focusing on material performance and release mechanisms. The use of biodegradable polymers in these packaging systems ensures that they decompose naturally after use, reducing plastic waste, and promoting sustainability. Smart packaging, integrated with indicators and sensors for pH or temperature, enables real-time monitoring of food conditions, empowering consumers and stakeholders with actionable insights throughout the supply chain. Antimicrobial packaging demonstrates significant potential in addressing food preservation and sustainability, the high costs associated with advanced materials, incorporation methods, and smart innovations also limit the widespread adoption of these technologies, particularly in developing countries. Scaling up production while maintaining the efficacy and stability of antimicrobial components also poses significant technical challenges. Future research must focus on developing cost-effective, scalable, and regulatory-compliant antimicrobial packaging solutions that balance performance, safety, and environmental sustainability to facilitate global implementation.