-

In the current society, the fast-paced work environment and unhealthy lifestyle have contributed to making gastric mucosal injury (GMI) become a main epidemic disease affecting human health. Medical experts have found that up to 53% of people between the ages of 20 and 30 have varying degrees of gastric disease through numerous surveys[1]. Their gastric mucosa faces heavy pressure with poor eating habits, smoking, excessive drinking, stress, and so on[2]. Therefore, improving the resistance of gastric mucosa is an urgent problem to be solved. Ethanol is one of the most common gastric mucosal injury factors[3], and excessive alcohol consumption can damage the gastric mucosa and cause it to fall out[4,5]. The stimulation of ethanol results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells, which aggravates the oxidative stress of gastric tissue and exacerbates the damage of gastric tissue by releasing pro-inflammatory factors (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), I interleukin-1β (IL-1β), endothelin-1 (ET-1), etc.) and various free radicals[5,6]. In addition, ethanol can reduce the level of nitric oxide (NO) needed to function properly, resulting in reduced blood flow to the stomach[7,8].

Studies have shown that the NO of serum can be used as an endogenous vasodilator to inhibit the production of ET-1, regulate blood flow volume, and alleviate GMI[4,9]. However, excessive concentration of NO in tissue can aggravate oxidative damage, promote the release of inflammatory factors, and accelerate the apoptosis of tissue cells[10]. The main source of NO is catalyzed by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Endothelial cells produce NO in the effect of eNOS, which plays an important role in the protection of gastric mucosa. It contributes to gastric mucosal healing by increasing blood flow to gastric tissue and nutrient supply[4,11,12]. Furthermore, the expression of eNOS is positively regulated by phosphorylated protein kinase B (P-AKT), and NO is a double-edged sword. In response to stimulation, a large amount of NO induced by iNOS is accumulated in tissue cells, leading to abnormal levels of NO and metabolic hypoxia in tissues[13]. The iNOS prevented eNOS from producing physiologically low concentrations of NO and accelerated oxidative damage of tissues. Studies have demonstrated that the down-regulation of iNOS expression can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory factors, thus playing a protective and anti-apoptotic role in cells[14,15]. ET-1 is an important cytokine for vasoconstriction, which can induce vasoconstriction and aggravate tissue hypoxia. Its elevation is induced by TNF-α. Interestingly, the large increase of ET-1, in turn, increased tissue oxidative stress, thereby promoting TNF-α production[16,17]. This leads to a vicious cycle that accelerates tissue damage. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) play an important role in vascular remodeling and tissue repair and healing[18,19]. The serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase (SGK) can be induced by EGF and VEGF, which can be activated through the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. It has been reported that high expression of SGK, EGF, and VEGF has a protective effect on tissue cells and can inhibit apoptosis of tissue cells[20,21]. These cytokines play different roles in the occurrence and development of gastric mucosal injury and are important indicators for improving gastric mucosal resistance.

At present, proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists are used to treat GMI. These chemosynthetic drugs have certain side effects, such as diarrhea and arrhythmia[22,23]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find a non-toxic and harmless new ingredient from food sources. Previous studies have shown that the mycelium polysaccharides of H. erinaceus have a variety of biological activities, including improving immunity, anti-oxidation, anti-aging, anti-inflammation, nourishing the stomach, and so on[24,25]. However, there are few studies on the intervention mechanism of gastric protection. In this study, the mechanism by which the polysaccharide derived from the fruiting body of H. erinaceus enhances gastric mucosal resistance was investigated in ethanol-induced GMI mice from the aspects of various inflammatory factors, PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and NO reaction.

-

Six-week-old Kunming mice were purchased from Jinan Pengyue Experimental Animal Breeding Center (Shandong, PR China). They were raised in five cages with ten mice in each cage, drinking and eating freely in the laboratory animal room (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C, humidity: 50% ± 5%, light cycle: 12 h). These mice, classified as SPF (specific pathogen-free) had passed the detection of Shandong Province animal testing center. The animal experiments were conducted under the supervision of the Ethics Committee for Laboratory Animals at Shandong Agricultural University (SDAUA-2023-103).

Drugs and reagents

-

In a previous study, HEP-1, a low molecular weight polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 1.67 × 104 Da and composed of →6)-β-D-Glcp-(1→, →3)-β-D-Glcp-(1→, β-D-Glcp-(1→, and →3,6)-β-D-Glcp-(1→, was isolated and characterized from the fruiting body of Hericium erinaceus[26]. The fruiting body of H. erinaceus was purchased from Shengfuyuan Edible Fungi Co., Ltd., Gutian County, Fujian Province, PR China. Omeprazole was purchased from Chengdu Tiantaishan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, PR China. The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbnent Assay (ELISA) kits, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, ET-1, EGF, NO, VEGF, were purchased from Jiangsu HRP-Conjugate Reagent Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, PR China. The antibodies of western blot and immunofluorescence were purchased from Shenyang WanLei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Other chemicals were all of analytical grade and gained through commercial sources.

Establishment of ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury model mice

-

The mice were randomly divided into five groups, with ten mice in each group. Mice were given a free diet and water to adapt to the laboratory environment for one week, and the following treatments were performed respectively (as shown inTable 1). All treatments lasted two weeks, and on day 22, the groups except the control group were given anhydrous ethanol (10 mg/kg) intragastric administration to induce gastric mucosal injury (all mice were fasted for 12 h with free access to water before modeling). Two hours after induction of GMI, blood samples were taken from the orbit of each mouse under anesthesia. The blood sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to obtain clean plasma. The mice were euthanized with cervical dislocation under anesthesia.

Table 1. Mice grouping and dose level.

Group Dose level Male number Duration

(weeks)Control 0.9% Saline (gavage) 10 2 Model 0.9% Saline (gavage) 10 2 OME Omeprazole (10 mg/kg b.w., gavage) 10 2 HEP-L HEP-1 (200 mg/kg b.w., gavage) 10 2 HEP-H HEP-1 (400 mg/kg b.w., gavage) 10 2 Determination of gastric mucosa injury index

-

The stomach was quickly removed after the mice were killed and cut open along the greater curvature of the stomach, which was washed with normal saline. The inside of the stomach was photographed to assess the extent of damage to the gastric mucosa. The degree of GMI was scored as follows: No ulcers (0 mm), 1−5 ulcers (< 1 mm) (1), 6−10 ulcers (< 1 mm) (2), > 10 ulcers (< 1 mm) (3), small linear ulcers (< 2 mm) (2), middle linear ulcers (2−4 mm) (3), large linear ulcers (> 4 mm) (4)[27]. If the width was greater than 1 mm, the fraction was multiplied by two. The gastric mucosal damage index was obtained by adding the sum of the fractions and dividing by the number of animals.

Determination of antioxidant index in vivo

-

The activities of catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and malondialdehyde (MDA) in gastric tissue homogenate were determined by the kit. The plasma was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was taken for determination. Gastric tissue (1 g) from mice was taken and ground with 9 ml phosphoric acid buffer solution, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was taken for determination.

Determination of various cytokines

-

The sample preparation method is the same as above. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, and ET-1 in gastric tissue were determined according to the instructions for use of the ELISA kit. At the same time, the levels of EGF and VEGF in gastric tissue were also measured using this method.

Determination of related indexes of NO reaction

-

NO levels of serum and gastric tissues were detected by the ELISA kit. The levels of eNOS and iNOS in gastric tissues were detected by immunofluorescence.

Histopathological examination of gastric mucosa

-

Gastric tissue specimens of mice were soaked in 10% formalin solution for 24 h for fixation. The fixed gastric tissue was embedded in paraffin. Then, the stomach tissue was sectioned with a thickness of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The gastric tissue was observed by a light microscope.

Effects of HEP-1 on PI3K-AKT signaling pathway

-

In order to prove that HEP-1 can activate the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, inhibit gastric cell apoptosis, and promote its survival. Western blotting was used to detect the expression of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway-related proteins in gastric tissues. AKT, P-AKT (SER473) and SGK in gastric tissues was detected. Expression levels of EGF and VEGF, which stimulate SGK expression, were also detected. Gastric tissue (0.1 g) of each group was accurately weighed, and 0.9 mL of tissue lysate, 10 μL protease inhibitor, and 10 μL phosphatase inhibitor were added and ground in a glass homogenizer for 20 min. The abrasive solution was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 10 min, and the supernatant was added to the loading buffer and placed in boiling water for 30 min to obtain protein samples required by Western blot (WB).

Statistical analysis

-

Animal experimental data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multi-interval test (SPSS 22.0 software package, USA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences in liver index, spleen index, kidney index, and thymus index among the experimental groups, indicating that the model of ethanol-induced gastric mucous membrane injury did not cause significant damage to the other organs of mice, and that HEP-1 did not have any significant toxicity effects on mice under the existing experimental conditions.

Table 2. Organ index of mice in each group.

Group Liver index

(mg/g)Spleen index

(mg/g)Kidney index

(mg/g)Thymus index

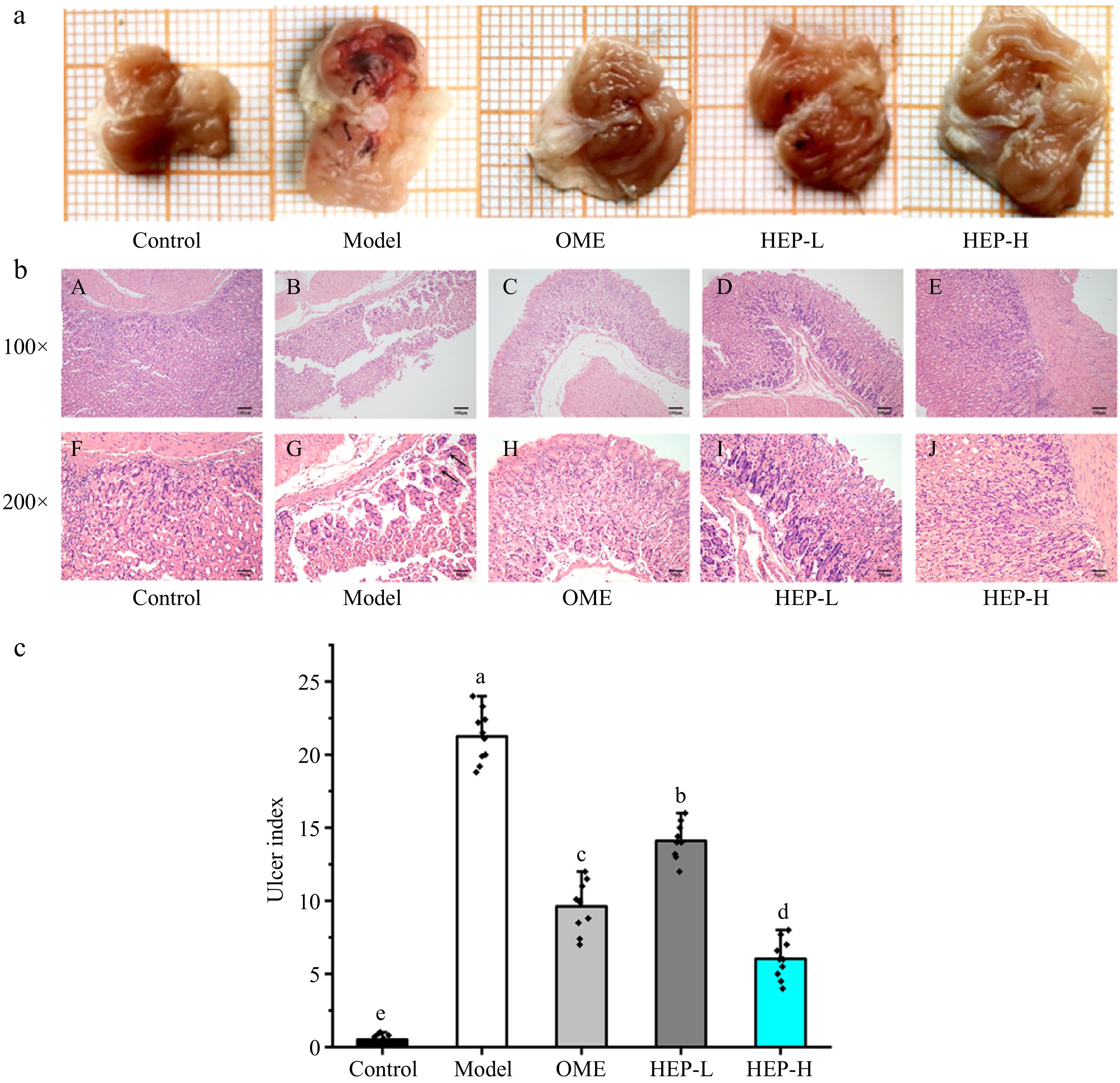

(mg/g)Control 38.62 ± 1.39 2.38 ± 0.23 15.41 ± 0.23 1.52 ± 0.25 Model 41.37 ± 1.42 2.55 ± 0.14 15.63 ± 0.27 1.55 ± 0.27 OME 40.20 ± 2.50 2.52 ± 0.13 15.36 ± 0.25 1.53 ± 0.26 HEP-L 40.39 ± 1.16 2.56 ± 0.25 15.54 ± 0.29 1.57 ± 0.23 HEP-H 40.82 ± 1.18 2.51 ± 0.21 15.37 ± 0.30 1.51 ± 0.28 As shown in Fig. 1a, the gastric mucosa of mice in the ethanol-induced model group was severely damaged, with extensive hemorrhagic necrosis. In the omeprazole group, there was a small amount of hyperemia, and gastric mucosa injury was relieved. Compared with the model group, the area, and degree of GMI in HEP-1 pretreated mice were significantly reduced. The injury of gastric mucosa was significantly decreased in the HEP-H group. In Fig. 1b, after staining, the gastric tissue was observed. The results showed that the gastric mucosa cells in the control group were intact and compact. On the contrary, the gastric tissue of the ethanol-induced model group showed hemorrhagic injury, submucosal edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, epithelial cell defect, and so on. In Fig. 1c, the ulcer index of gastric tissues of mice in the pre-treatment groups of omeprazole, HEP-L and HEP-H were significantly decreased after ethanol stimulation by 54%, 36%, and 72%, respectively. Pre-treatment with omeprazole and HEP-1 significantly reduced the ethanol-induced pathological changes.

Figure 1.

Macro lesion, ulcer index, and histological evaluation of gastric tissue. (a) Effect of HEP-1 on macromorphology of gastric mucosa. A grid in the figure represents the actual 1 mm2. (b) Histopathological evaluation of the effect of HEP-1. Blank arrow: swelling of epithelial cells, with loose cytoplasm and pale staining. Uppercase letters (A−E) indicated H&E staining of gastric mucosa (100×), (F−J) indicated H&E staining of gastric mucosa (200×). (c) Effect of HEP-1 on ulcer index. Lowercase letters (a−e) indicated significant differences at p < 0.05.

Effects of HEP-1 on oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in stomach tissue

-

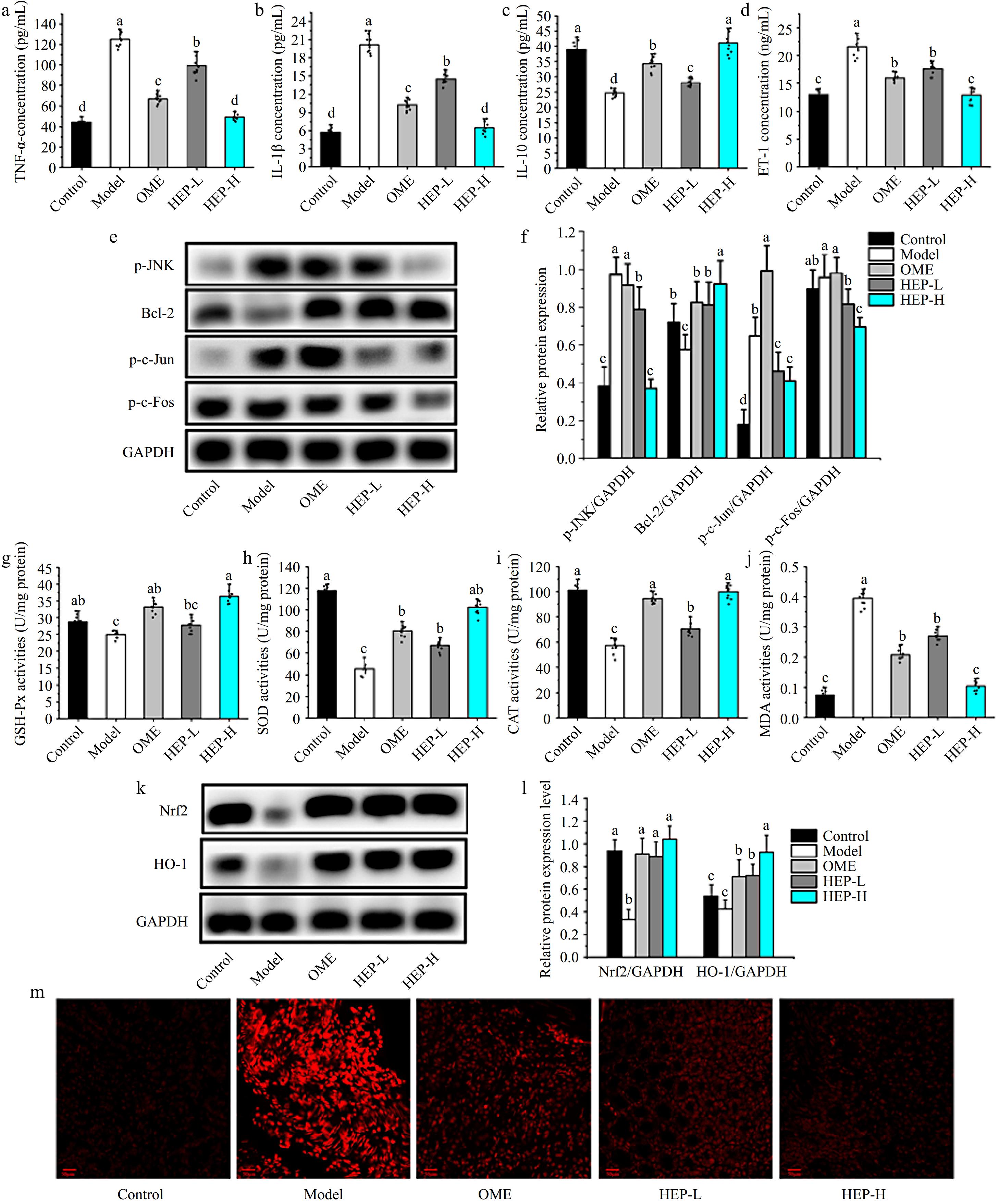

Inflammatory cytokines were measured in gastric tissue homogenate and the analysis results are shown in Fig. 2a−d. Compared with the control group, the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and ET-1 in the gastric tissues of the model group were significantly increased by 183%, 188%, and 63%, respectively, and the levels of IL-10 were significantly decreased by 38%. Compared with the model group, the levels of TNF-α in the gastric tissues of mice pretreated with omeprazole, HEP-L and HEP-H decreased by 47%, 21%, 131%, and IL-1β by 50%, 38%, and 56%, respectively, and the levels of IL-10 increased by 39%, 13%, and 64%, respectively. ET-1 is a vasoconstrictor polypeptide. Ethanol stimulation can raise it significantly. Pretreatment with HEP-1 significantly inhibited the excessive increase of ET-1 level. Pretreatment of HEP-1 can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β) and promote the expression of anti-inflammatory factor IL-10, thereby reducing the production of ET-1. Additionally, JNK is an important member of the MAPK family can regulate various stress responses both inside and outside the cell. The JNK signaling pathway plays a crucial role in regulating cell death and inflammation. In Fig. 2e−f, the HEP-1 intervention modulated the MAPK-JNK pathway, suppressed the activation of JUN, and significantly reduced inflammation and apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Effects of HEP-1 on inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in stomach tissue. (a) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). (b) Interleukin-1β (IL-1β). (c) Interleukin-10 (IL-10). (d) Endothelin-1 (ET-1). (e) Representative immunoblot bands. (f) The relative protein expressions. (g) Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). (h) Superoxide dismutase (SOD). (i) Catalase (CAT). (j) Malondialdehyde (MDA). (k) Representative immunoblot bands. (l) The relative protein expressions. (m) ROS fluorescence staining.

The levels of GSH-Px, SOD, CAT, and MPO in gastric tissue homogenates were evaluated. Results as shown in Fig. 2g−j, compared with the control group, ethanol stimulation resulted in a significant decrease in antioxidant enzyme content and a significant increase in MDA level. Compared with the model group, the levels of GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT were significantly increased in gastric tissue after ethanol stimulation with the pre-treatment of omeprazole, HEP-L, and HEP-H, while the level of MDA was significantly decreased. The levels of GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT of gastric tissue in HEP-H group were increased by 53%, 98%, and 120%, respectively, while MDA level was decreased by 66%, as compared with the model group. The results of western blot showed that HEP-1 increased the protein expressions of Nrf-2 and HO-1 (Fig. 2k−l) and reduced the levels of ROS (Fig. 2m). Through this process, it inhibits the decrease of blood flow of gastric tissue, improves oxygen and nutrient supply to tissues and reduces the generation of oxidative stress.

Effect of HEP-1 on NO reaction in gastric tissue

-

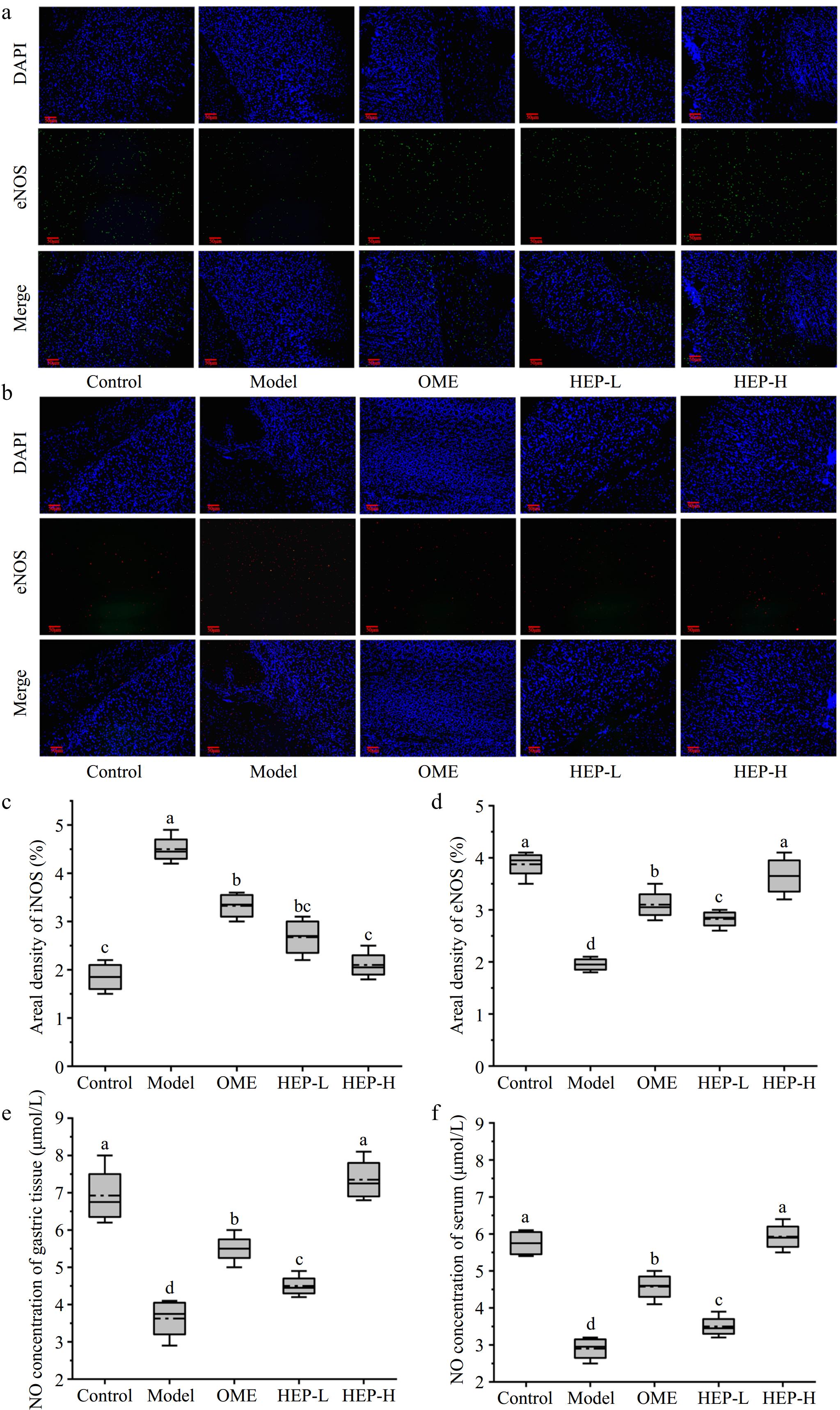

To investigate the effect of HEP-1, the levels of NO in gastric tissue and serum were measured. The expression levels of eNOS and iNOS, related to NO production, were detected by the immunofluorescence method, as shown in Fig. 3a−d. HEP-1 pretreatment significantly increased the expression level of eNOS, while the expression level of iNOS decreased. In Fig. 3e−f, the level of NO in the model group was significantly decreased, as compared with the control group. This is consistent with the research results of Li et al.[21]. Compared with the model group, the level of NO in HEP-1 groups was significantly increased. HEP-1 can effectively inhibit the expression of iNOS and promote the expression of eNOS. Thus, it can regulate the physiological balance of NO, enhance the activity of the central nervous system, and play an anti-ulcer role.

Figure 3.

The levels of eNOS and iNOS in the gastric tissue of mice analyzed by immunofluorescence. (a) Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). (b) Induction nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). (c) Areal density of iNOS. (d) Areal density of eNOS. (e) The NO of gastric tissue. (f) The NO of serum.

Effects of HEP-1 on PI3K-AKT signaling pathway

-

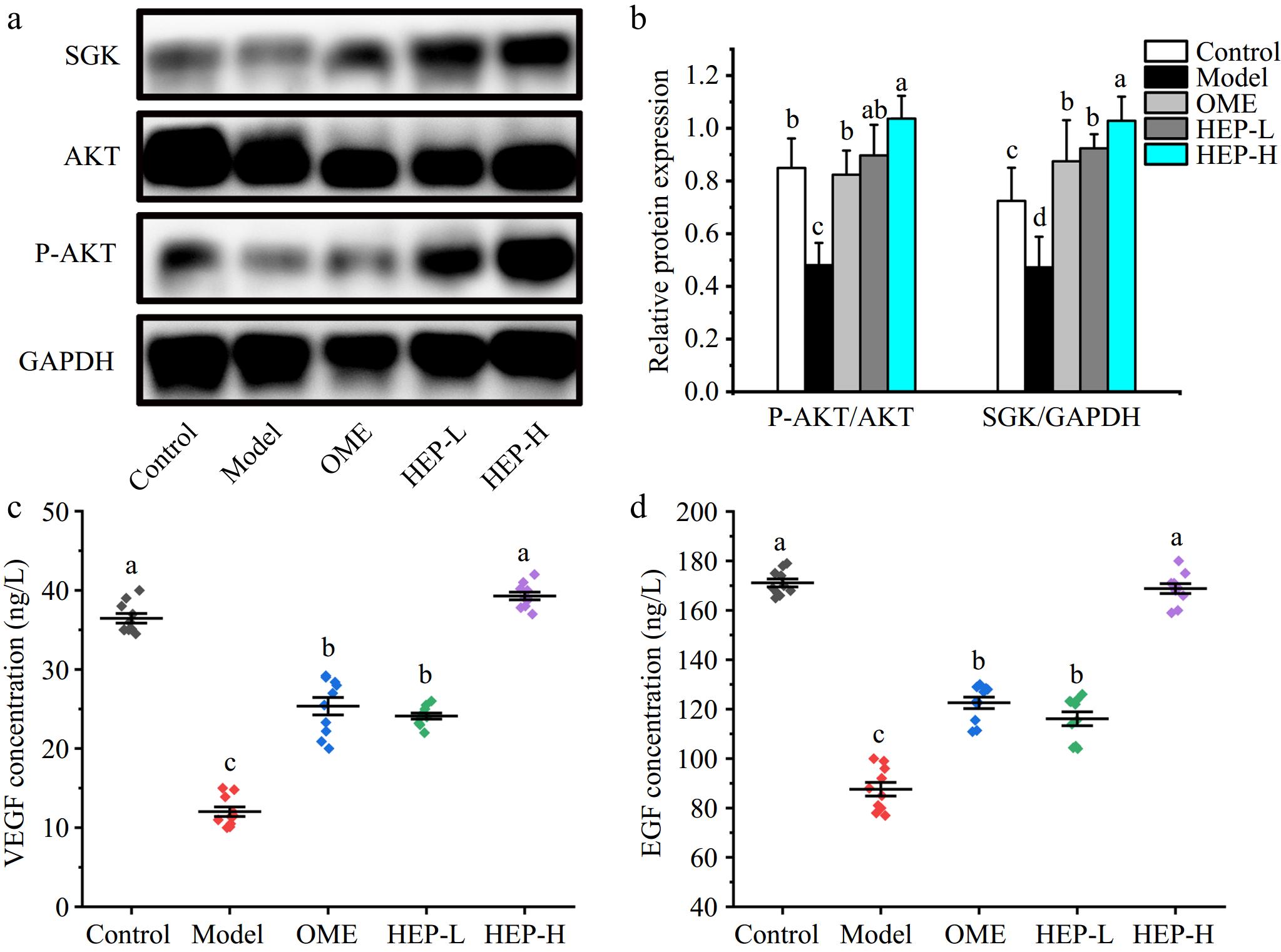

In order to further explore the mechanism of HEP-1 intervention on GMI, in Fig. 4a and b, the expression level of AKT/P-AKT was detected in the gastric tissues of each group by western blotting method and the results showed that P-AKT level increased significantly after pretreatment with HEP-1, indicating that HEP-1 intervention activated PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. This result is consistent with the previous results suggest that HEP-1 pretreatment may promote the increase of eNOS through the activation of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. In Fig. 4a and b, the levels of SGK were also detected, and it was found that the intervention of HEP-1 significantly improved the expression level of SGK. EGF and VEGF are the main factors that induce the increase of SGK expression, and are also the key to promote the repair and healing of injury[28]. In Fig. 4c and d, the results showed that the level of EGF in gastric tissue was significantly increased after pretreatment with HEP-1, which was 19% and 56% higher than that in the model group respectively. Similarly, levels of VEGF in gastric tissue increased significantly, by 37% and 91%, respectively, as compared with the model. The increase of EGF and VEGF levels promoted the repair and healing of gastric wounds, promoted the regeneration of blood vessels, and played a positive protective effect on gastric mucosa.

Figure 4.

Effects of HEP-1 on levels of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway-related proteins in ethanol-induced gastric injury. (a), (b) Western blot images of SGK, P-AKT, AKT, and GAPDH. (c) VEGF level in gastric tissue. (d) Epidermal growth factor (EGF) level in gastric tissue. The gray quantitative data of western blotting was determined by image J software.

-

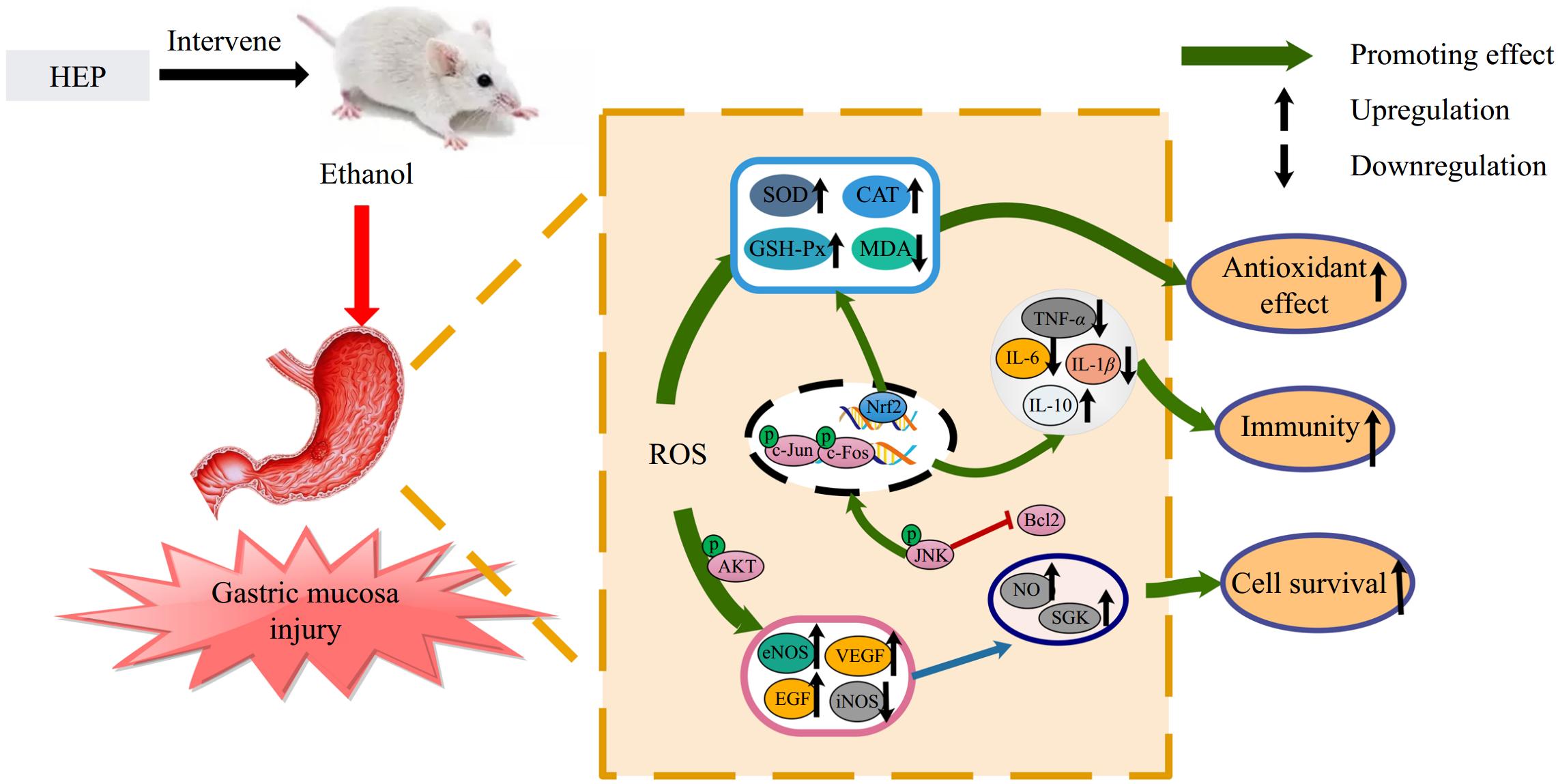

H. erinaceus has a protective effect on gastric mucosa, the main active component of which is polysaccharide[29]. HEP-1 can improve gastric mucosal circulation and enhance gastric mucosal defense function by accelerating the regeneration and repair of gastric mucosal epithelium[30,31]. As shown in Fig. 5, it is proved that HEP-1 has the activity of improving gastric mucosal defense ability.

Figure 5.

HEP protect against gastric mucosa injury via modulating inflammatory factors, promoting antioxidant activity, and activating the PI3K-AKT pathway.

Excessive intake of alcohol is one of the main factors causing gastric mucosa injury. The stimulation of alcohol can cause bleeding and shedding of gastric mucosa and the release of a large number of inflammatory factors[32]. These inflammatory factors activate the NF-κB signaling pathway and iNOS, and stimulate the accumulation of immune cells at the site of injury, resulting in increased hypoxia in gastric tissues[33,34]. The production of gastric protective factors such as NO can make blood vessels dilate, which provides capacity and oxygen support for the repair of gastric tissue injury. NO is an unstable free radical produced during the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by nitric oxide synthase (NOS). It serves as a signaling molecule involved in regulating various physiological processes. Research has shown that NO can activate soluble guanylate cyclase, converting GTP into c-GMP[35], leading to vasodilation and smooth muscle relaxation, regulating gastric pH, increasing mucosal blood flow, maintaining mucosal integrity, enhancing gastric mucosal defense factors, and improving gastric tissue damage[36]. The increase in NO level can inhibit the production of ET-1 and play a role in vasodilation[9]. NO produced by endothelial cells induced by eNOS can enter the blood to play physiological functions. However, high concentrations of NO induced by iNOS in tissues can cause tissue hypoxia and aggravate tissue oxidative damage. In this study, HEP-1 regulates the balance of NO by upregulating eNOS expression and downregulating iNOS expression, enabling NO to exert protective effects rather than pro-inflammatory effects. This is consistent with previous reports[14].

It has been reported that high expression of SGK, EGF, and VEGF has a protective effect on tissue cells and can inhibit apoptosis of tissue cells[18]. Baccharis trimera extract,[37] Hunan insect polyphenols[38], and Kuding tea polyphenols[39] can improve the expression of EGF and VEGF, and enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes, thus playing a role in the prevention and promotion of ulcer healing. HEP was found to promote the production of EGF and VEGF, activate the expression of SGK, and enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes. These effects play an important role in promoting cell survival, healing, and repair of injury.

In this study, the molecular mechanism of polysaccharide from the fruit body of H. erinaceus on gastric mucosa was investigated in ethanol-induced gastric mucosa injury mice. The intervention of HEP-1 can reduce the inflammatory response of gastric mucosal injury. Interestingly, the study also found that HEP-1 can activate the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, which promotes the expression of eNOS due to the phosphorylation of AKT. Activation of this pathway also enhances the expression of SGK[40,41]. Increased EGF and VEGF expression levels also stimulate SGK expression. These growth factor can promote the repair of gastric mucous membrane injury and healing, accelerate blood vessel new birth, enhance its resistance to external stimulation[35,42]. On the one hand, this study provides ideas for the mechanism of gastric mucosal protection, and provides the basis for further development of more diversified gastric nourishing foods.

-

In conclusion, HEP-1 has the ability to improve gastric mucosal defense ability and its molecular mechanism may be able to improve gastric mucosal resistance to external stimulation by promoting the activity of antioxidant enzymes, inhibiting the production of inflammatory factors, increasing the level of eNOS-derived NO in gastric tissues, and upregulating the levels of EGF and VEGF.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of PR China (Grant No. 31901644), and the University Innovation Team of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2022KJ243).

-

All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines provided by the Animal Care Committee. The animal experiments were conducted under the supervision of Ethics Committee for Laboratory Animals in Shandong Agricultural University (SDAUA-2023-103).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing-original draft, conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization: Cui W; software, formal analysis: Cui W, Zhu X; writing-review and editing: Zhu X, Song X, Li X, Jia L, Zhang C; supervision: Jia L, Zhang C; resources: Zhang C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Weijun Cui, Xiangyang Zhu

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cui W, Zhu X, Li X, Song X, Jia L, et al. 2025. Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides (HEP) protect against gastric mucosa injury via modulating inflammatory factors, promoting antioxidant activity, and activating the PI3K-AKT pathway. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 284−292 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0028

Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides (HEP) protect against gastric mucosa injury via modulating inflammatory factors, promoting antioxidant activity, and activating the PI3K-AKT pathway

- Received: 24 October 2024

- Revised: 06 March 2025

- Accepted: 07 March 2025

- Published online: 08 July 2025

Abstract: Gastric mucosal injury (GMI) is a common pathology affecting many people around the world. Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides (HEP) have various biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidation, and protection of the gastrointestinal tract. HEP-1, a low molecular weight polysaccharide (1.67 × 104 Da) isolated from Hericium erinaceus, is composed of →6)-β-D-Glcp-(1→, →3)-β-D-Glcp-(1→, β-D-Glcp-(1→, and →3,6)-β-D-Glcp-(1→. However, whether HEP has preventive efficacy against GMI is unknown. This study investigated the intervention effect and potential mechanism of HEP-1 on GMI. Mice treated with HEP-1 for two weeks were treated with ethanol to induce gastric mucosal damage. The gastric mucosal tissue pathology, gastric tissue inflammatory factors, and gastric oxidative stress function were evaluated. The results showed that HEP-1 increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, reduced the release of inflammatory factors, promoted the production of nitric oxide (NO), inhibited the production of endothelin-1 (ET-1), and increased the blood flow of gastric mucosa to maintain the defensive function of the gastric mucosa. HEP-1 also activated the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, increased the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), promoted the expression of serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase (SGK), and enhanced the biosynthesis of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thereby facilitating the repair and healing of gastric mucosal injury (GMI). Therefore, HEP-1 has the potential to preserve the integrity of the gastric mucosa and is anticipated to be a key bioactive ingredient in the prevention and repair of GMI.

-

Key words:

- Hericium erinaceus /

- Polysaccharides /

- Gastric mucosal injury /

- NO /

- PI3K/AKT