-

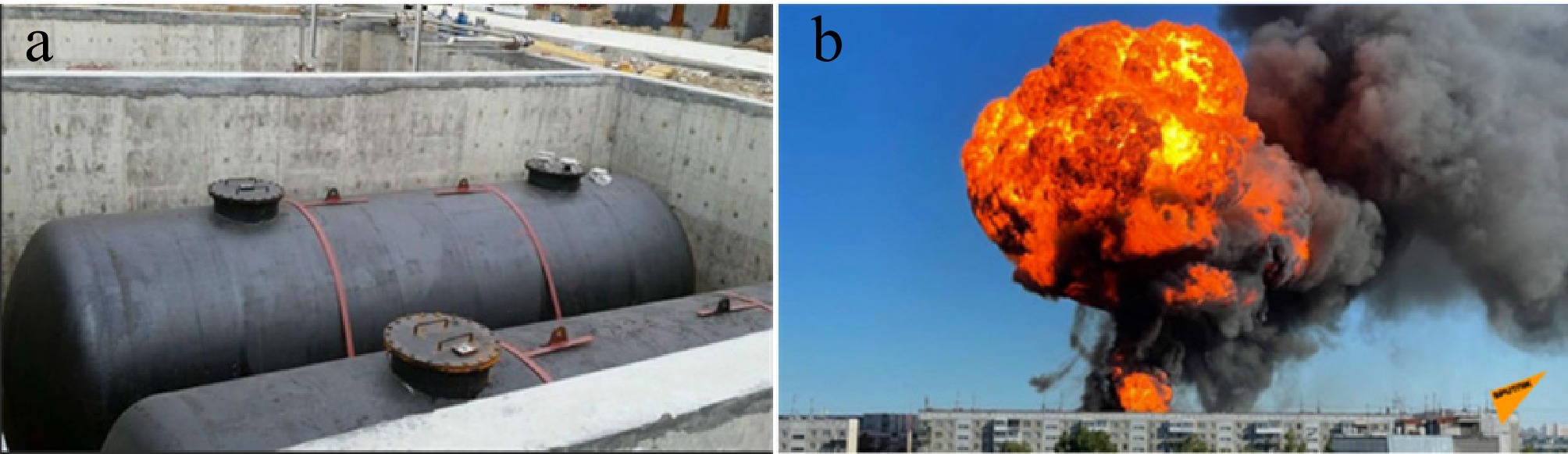

Over the past decade, there has been a notable transformation in domestic energy consumption within low- and middle-income nations, with a marked transition from solid fuels to more environmentally friendly gaseous fuels[1], notably liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and liquefied natural gas (LNG). These liquefied gases are frequently considered as eco-friendly substitutes for conventional biomass because of their superior ability to curtail emissions of various pollutants, including PM2.5, CO, and SO2[2]. However, because of the need to store liquefied gas under pressurized conditions, once the tank leaks due to its own defects or external factors, the gas can easily overheat, potentially leading to serious accidents. The infamous Russian gas station underground storage tank disaster in 2021 was an accident involving an explosion of liquefied petroleum gas (Fig. 1). The explosion caused a fire covering an area of about 500 m2 and injured 35 people, including two firefighters. In actual accident situations, since leakage points in tanks may emerge either spontaneously or non-spontaneously, BLEVE manifests in two distinct manners. Firstly, the tank wall itself has weak points, and cracks are gradually formed due to overfilling and thermal action. Similar experimental pressure depressurization methods are bursting disc and bursting film. Secondly, the tank cracks directly under the external force, such as the experimental methods of ball valve or needle puncture. The effect of vessel weak link fracture and external impact-induced rupture on the onset of superheated boiling is distinct. Therefore, the feasibility of pressure depressurization devices will directly affect the effective influence of typical parameters in boiling explosion experiments. However, the scientific understanding is still limited in the open literature.

Figure 1.

The scenarios of (a) before, and (b) during the fire or explosion of the underground storage tank (Credit: World Wide Web).

Furthermore, the probability of BLEVE occurrence is contingent upon the magnitude of the stored explosive energy in the pressurized liquefied gas[3]. This energy accumulates during pressurization due to thermal exposure and is subsequently released violently through explosive boiling following complete vessel failure. The energy discharged during such an explosion stems from both vapor and liquid contents within the container. The vapor's energy is primarily responsible for generating shock overpressures in both near and far fields[4,5]. While liquid flashing and expansion can induce local overpressures via dynamic pressure effects, they typically do not generate shock waves because this process unfolds too gradually[6,7]. Additional dangers like near-field shock waves and debris strikes are predominantly influenced by liquid energy[8,9]. Moreover, factors such as boiling intensity, various working fluids, and expansion flow counterflow interactions are intricately linked to contained liquid energies[10,11]. Despite extensive studies on the initiation dynamics of BLEVE and the evolution of the internal medium, most research assumes that containment failures occur openly, without considering confined environments such as underground spaces or buildings, where BLEVEs present unique hazards and remain understudied areas requiring further investigation.

Extensive research has been conducted to suppress pressure rebound and explosive boiling in the context of BLEVEs. Methods for suppressing explosive boiling include using metal nets[12], adding solid particles[13], and installing micro-fin surfaces[14]. These methods can advance nucleation or hinder bubble movement during depressurization, which reduce the area where superheated liquids boil, leading to a slower vaporization rate and a reduced intensity of explosive boiling. Methods for suppressing pressurization include using venting devices[15], and water spray cooling[16]. These approaches prevent the liquid temperature from exceeding the superheat limit temperature and extend the failure time. However, suppressing rapid depressurization processes can also effectively reduce the probability of BLEVE, although there is limited research on this topic in the published literature. Tank explosions are often caused by local rupture and rapid depressurization. Moreover, the rate at which this occurs significantly affects explosion intensity[17]. Confined spaces inhibit external pressure action when tanks leak while providing buffering effects on explosive boiling by controlling depressurization rates[18].

Meanwhile, the response of two-phase flow movement to pressure in the storage tank is also an important factor affecting the rapid depressurization. The study examined both the micro-processes involved in evolution during superheating-induced ebullition and the dynamic characteristics inherent to flows consisting of gas and liquid phases simultaneously[19]. The results show that the superheated liquid in the container has a low depressurization rate due to small cracks, and there is almost no pressure recovery. However, when the initial pressure increases, the rapid depressurization process will produce two overpressure peaks, and it is believed that the action of steam on the top of the tank is the cause of the first overpressure peak[20,21]. Additionally, it was discovered that swift mist-like dual-phase currents mainly drive up top-tank pressures. Experiments using R113 demonstrated that both beginning pressurizations and commencing liquid heats crucially impact speedy relief scenarios[22].

In this work, a small-scale experiment was conducted to explore the effects of needle puncture of PET film and natural rupture of PET film on liquid superheated boiling in a confined space. Moreover, the reasons for the absence of pressure rebound were discussed using a high-speed camera after the container was opened. When rapid depressurization occurs within a confined space, the resulting superheated boiling is insufficient to trigger pressure recovery. As a result, this phenomenon will not lead to severe damage to the storage tank. This finding has significant implications for the design and protection of tanks.

-

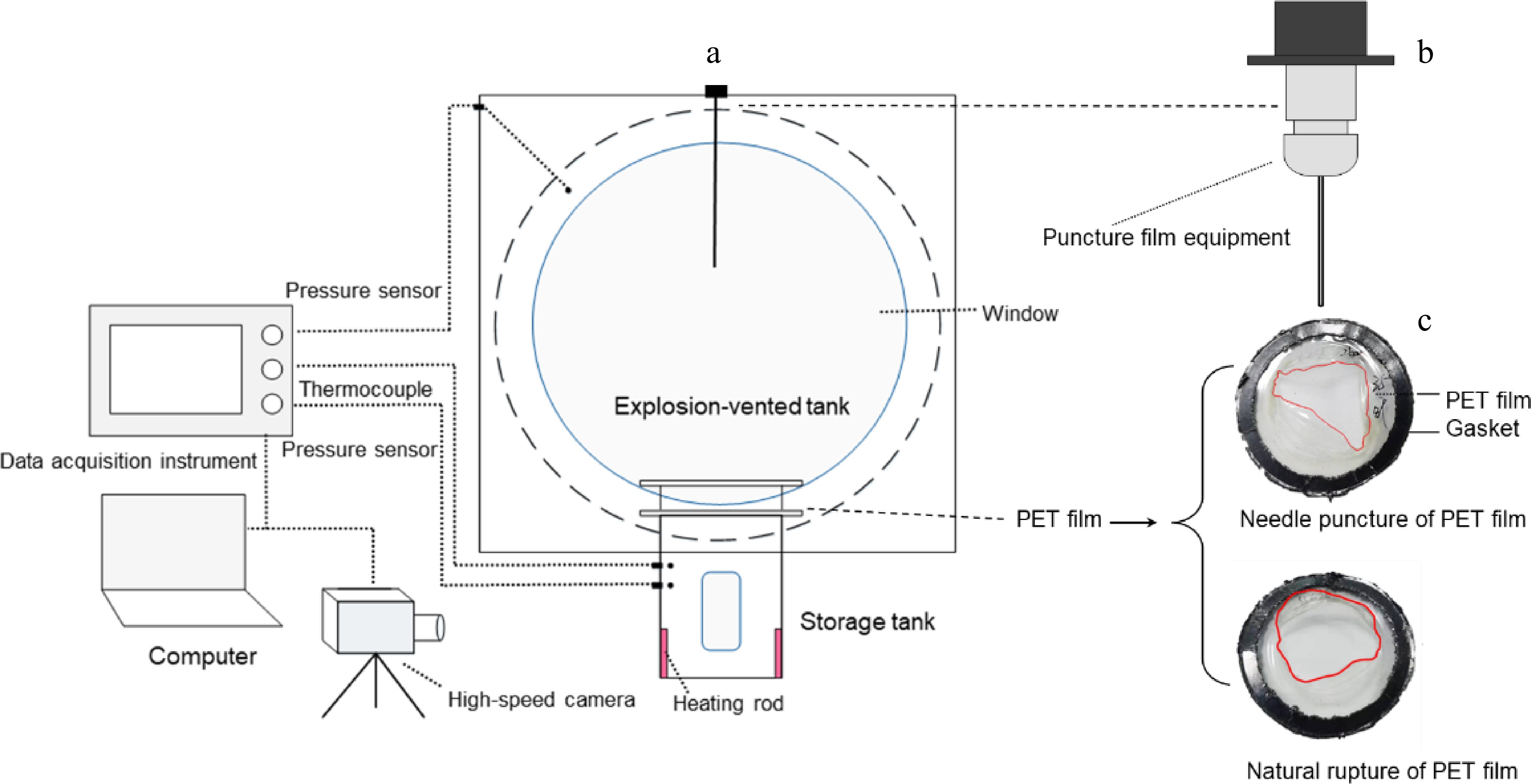

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2. It mainly consisted of heating rods to heat the liquid to the preset temperature and pressure, the pressure storage tank to support the liquid medium, the PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate) film[23] to regulate the pressure relief conditions, and an explosion-vented tank to simulate a confined space. The pressure vessel is made of stainless steel, with a diameter of 68 mm, a thickness of 13 mm, a height of 150 mm, and a volume of 0.25 L. Two viewing ports were positioned on the front side, covering the liquid level range of 10%–30% (equivalent to 20–50 mm in vessel height) to facilitate observation of two-phase flow behavior. A 42-mm-diameter PET film was installed atop the vessel, designed to rupture and release the internal medium upon reaching the preset constant pressure. An orifice plate was integrated above the PET membrane to control the venting area.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the (a) experimental device, the (b) needle puncture film equipment, and (c) PET film.

To explore the effect of the opening size and shape, the spontaneous and non-spontaneous formation of cracks has been introduced by the natural rupture and needle puncture. These actions correspond to simulating the storage tank itself having weak links and the external mechanical action of the storage tank, respectively. A 2 L explosion-vented tank was mounted atop the pressure storage tank, equipped with four evenly spaced 100-mm-diameter viewing ports arranged symmetrically across its spherical surface. In experiments with the natural rupture of PET film, a series of tests were conducted on films of different thicknesses by controlling the initial release pressure to quantify their effects on the pressure response inside the storage tank and the explosion-vented tank. Here, the PET films with a thickness of 0.025–0.1 mm correspond to a natural rupture pressure of 1.7–4.6 barg. To accurately control the blasting time and record the dynamic evolution process of pressure response, bubble formation, and two-phase flow, a millisecond-response needle puncture mechanism was employed to perforate the PET membrane at predetermined initial pressures (1.5, 2, and 3 barg). All the experiments were conducted under a liquid fill level of 70% and a discharge area of 9.6 cm2, which falls within the typical range observed in practical cases[24]. The ambient temperature is 20 °C. The experimental conditions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Experimental conditions.

Category Fill level Discharge area

(cm2)PET thickness

(mm)Release pressure

(barg)Nature rupture 70% 9.6 0.025 1.7 ± 0.2 0.038 2.4 ± 0.3 0.05 2.8 ± 0.2 0.075 3.8 ± 0.3 0.1 4.6 ± 0.1 Needle puncture 70% 9.6 0.025 1.5 0.038 2.0 0.075 3.0 Test procedures and controlled parameters

-

Before each test, a water ring vacuum pump evacuated air to eliminate gaseous interference. The fluid was then heated and pressurized within the pressure vessel. Upon reaching the predetermined pressure, the PET film is either pierced or undergoes spontaneous rupture, inducing swift and localized depressurization to drive the liquid into a superheated state. Temperature monitoring employs K-type thermocouples while transient pressure data acquisition utilizes a HM90 dynamic pressure sensor with 1 MS/s sampling capability.

During rapid depressurization, a high-speed camera with 1,000 frames per second was used to observe the two-phase flow, bubble motion, and ejection. In repeated experiments, the experimental phenomena inside the storage tank and explosion-vented tank were recorded separately. Measurements of liquid levels were taken both before and after each experiment. Given the intricate nature of the experimental conditions, a minimum of 3–5 repetitions were performed for each specific set of experimental conditions.

Uncertainty analysis

-

The experimental discrepancies observed in this study primarily stem from the inherent uncertainties associated with the testing apparatus. The vacuum level maintained during the experiments fluctuates between 0.8–0.9 barg. Consequently, there may be minor variations in the trace amounts of residual gases present within each experimental chamber. The thermocouples have an absolute error of ± 1 °C, and the pressure sensors boast an accuracy error of 0.25%. These errors are within an acceptable range and will not affect experimental and analytical results.

-

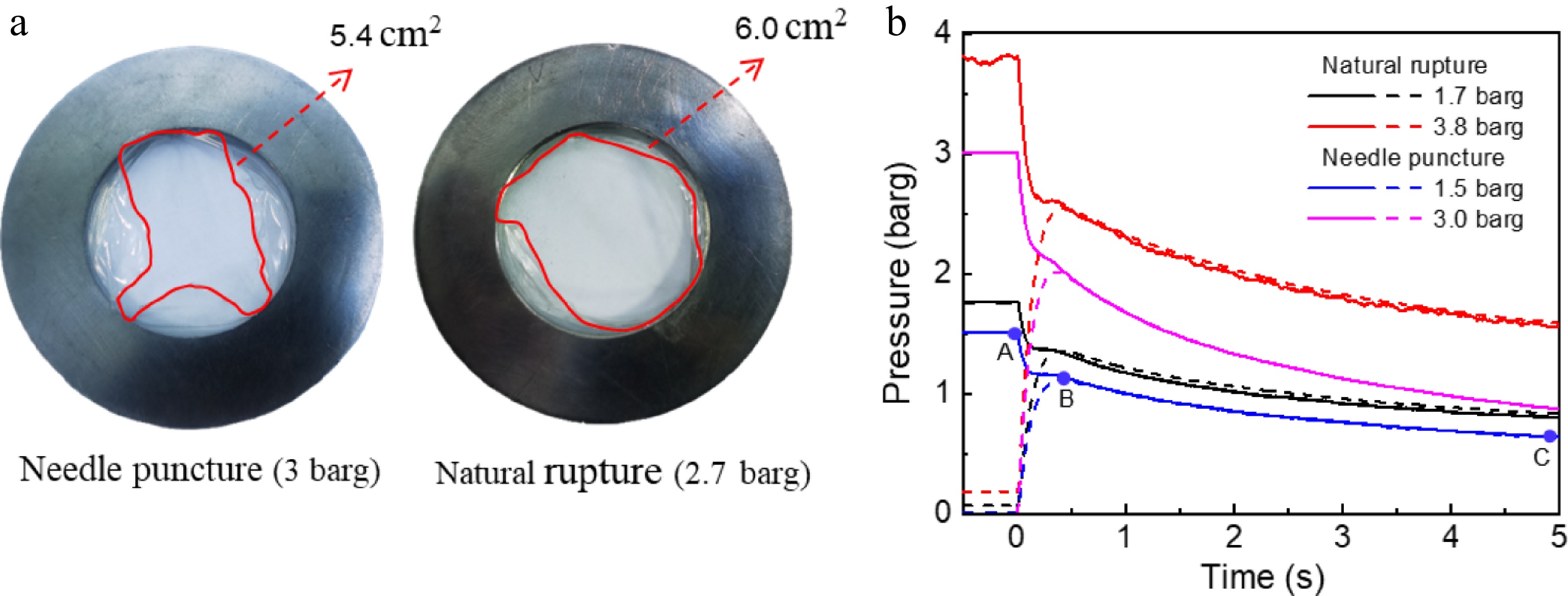

Figure 3a shows the fracture diagram of the PET film rupture under puncture rupture and natural rupture. The crack of natural rupture tears more completely than a needle puncture. The reason for the natural rupture mechanism is that continuous pressure causes the PET film to reach its maximum pressure tolerance limit, resulting in a complete brittle fracture of its internal structure. Figure 3b illustrates the effect of PET film thickness on the pressure response in both tanks. When the pressure limit of the PET film is reached and it ruptures, the pressure in the storage tank drops sharply, and the pressure in the explosive tank increases sharply. This phenomenon is caused by vigorous vaporization and two-phase flow induced by localized depressurization of superheated liquid. As vaporization continues, the explosion-vented tank eventually reaches saturation, leading to a subsequent decline in pressure.

The burst pressure variability in PET films makes it difficult to determine the exact timing of rupture. To better control release pressures, needle puncture was used to mimic situations where external actions (e.g., mechanical impacts) could directly create cracks and leaks in storage tanks. However, rapid depressurization produces notably different effects compared to natural rupture. The corresponding pressure responses and leakage characteristic parameters for different depressurization modes are illustrated in Figs 3−5 respectively.

As illustrated in Fig. 3b, there are distinct differences in the pressure response between the two tanks under the depressurization modes of natural rupture and needle puncture. The PET film of 0.025 and 0.075 mm thickness, corresponding to natural rupture pressure of 1.7 and 3.8 barg, and the needle puncture pressure of 1.5 and 3 barg, respectively, were selected to control the initial release pressure. After rapid depressurization, there is no pressure rebound in the rapid depressurization process of both natural rupture and needle puncture under the explosion-vented tank. However, when needle puncture is used as the depressurization method, the pressure inside the explosion-vented tank will not exceed the storage tank pressure during rapid depressurization. For instance, if the initial pressure is 1.5 barg, as the storage tank pressure decreases to 1.1 barg, the pressure within the explosion-vented tank increases to 1.06 barg, eventually aligning closely with the storage tank pressure. As the pressure continues to drop, the pressure in the explosion-vented tank consistently remains below that of the storage tank. In contrast, when natural rupture is employed for depressurization, the pressure within the explosion-vented tank can exceed the pressure in the storage tank. This indicates that the leakage rate of needle puncture is significantly smaller than that of natural rupture.

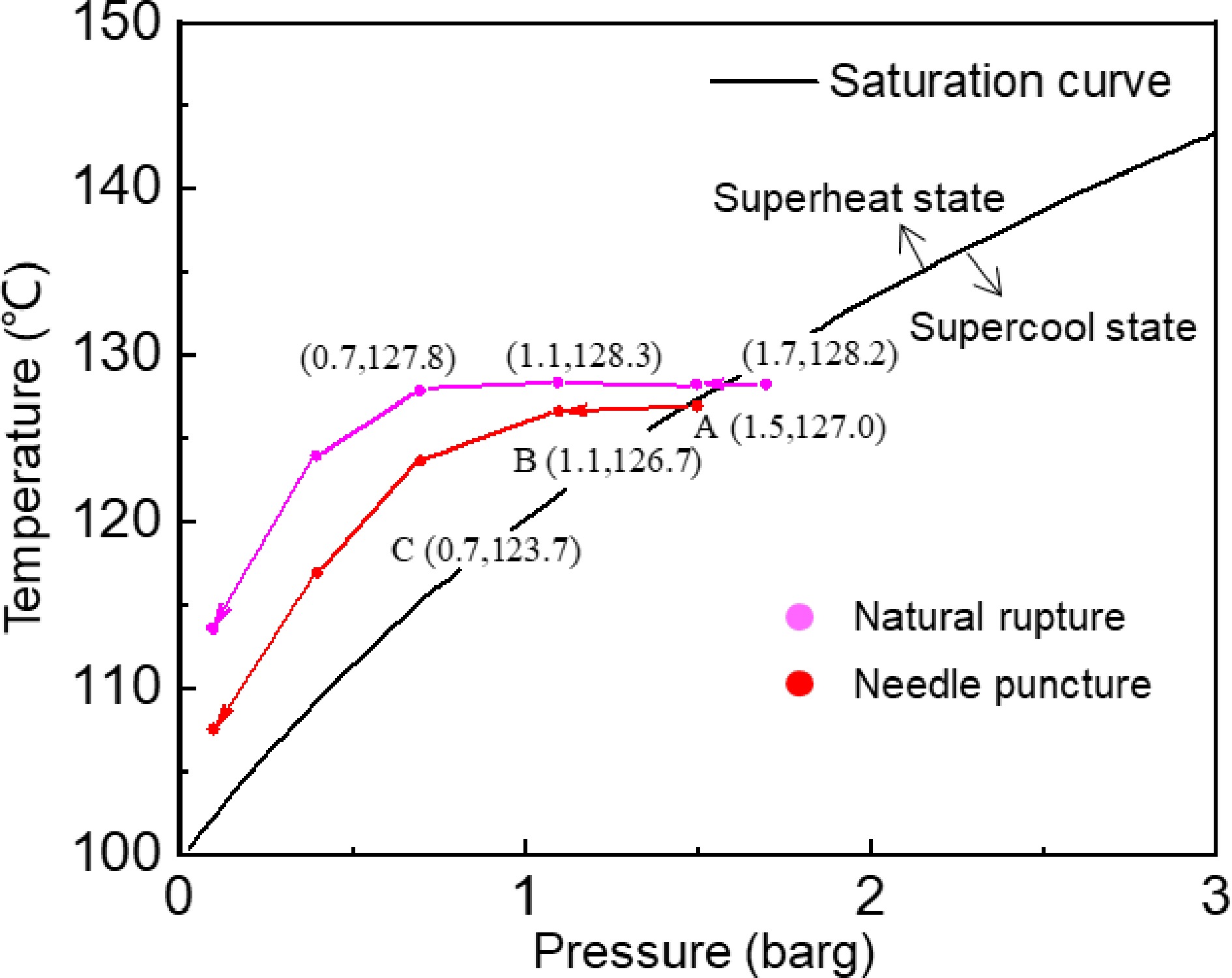

Figure 4 shows the saturation curve at the initial pressure of puncture rupture of 1.5 barg and the initial pressure of the natural rupture of 1.7 barg, aiming to analyze the correlation between medium superheating and time during rapid depressurization. The saturated vapor pressure corresponding to water at different temperatures is determined based on the thermodynamic properties of water (the saturation curve shown in Fig. 4). The medium is in a superheat state when the pressure-temperature coordinate point lies above the saturation curve, and in a supercool state when it lies below the saturation curve. Taking the puncture rupture of 1.5 barg as an example, the temperature of the medium is below the saturation temperature and in a supercool state before the rapid pressure reduction of the storage tank. When the crack opens, the pressure and temperature will decrease correspondingly. However, due to the significantly higher rate of pressure reduction compared to the cooling rate, the medium rapidly becomes superheated, transitioning from point A to point B. With the ongoing depressurization, the peak superheat occurs at the moment when the two tanks have the same pressure. Before the storage tank reaches atmospheric pressure, it remains in a superheated condition influenced by the restraining effect. This is different from the superheated state in an open space, which quickly becomes a supercooled state.

Pressure characteristic parameters

-

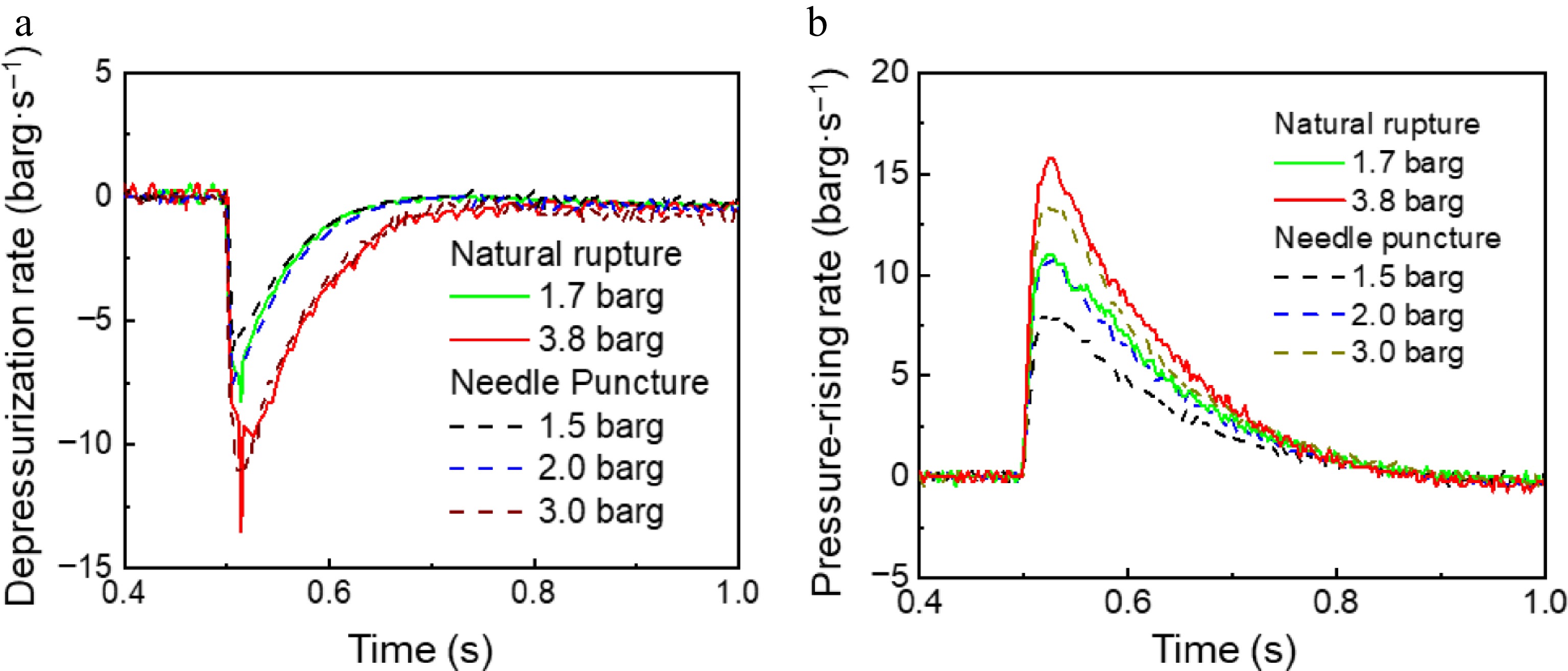

Figure 5 shows the rate of pressure variation of two tanks under different depressurization modes. As the initial pressure increases, the maximum depressurization rate of the storage tank and the maximum pressurization rate of the explosion-vented tank exhibit nonlinear growth. This trend is observed because, when the PET film thickness is 0.025 mm (corresponding to a release pressure of 1.7 barg), the maximum depressurization and pressurization rates (as shown in Fig. 4a) exceed those at 2 barg, indicating a higher depressurization rate for natural rupture under identical operating conditions. The results indicate that various depressurization techniques yield distinct impacts on the process of rapid leakage. The results demonstrate that different depressurization modes have distinct effects on the rapid leakage process.

Figure 5.

The depressurization rate in the (a) storage tank, and the (b) pressurization rate in the explosion-vented tank under the depressurization mode of natural rupture and needle puncture.

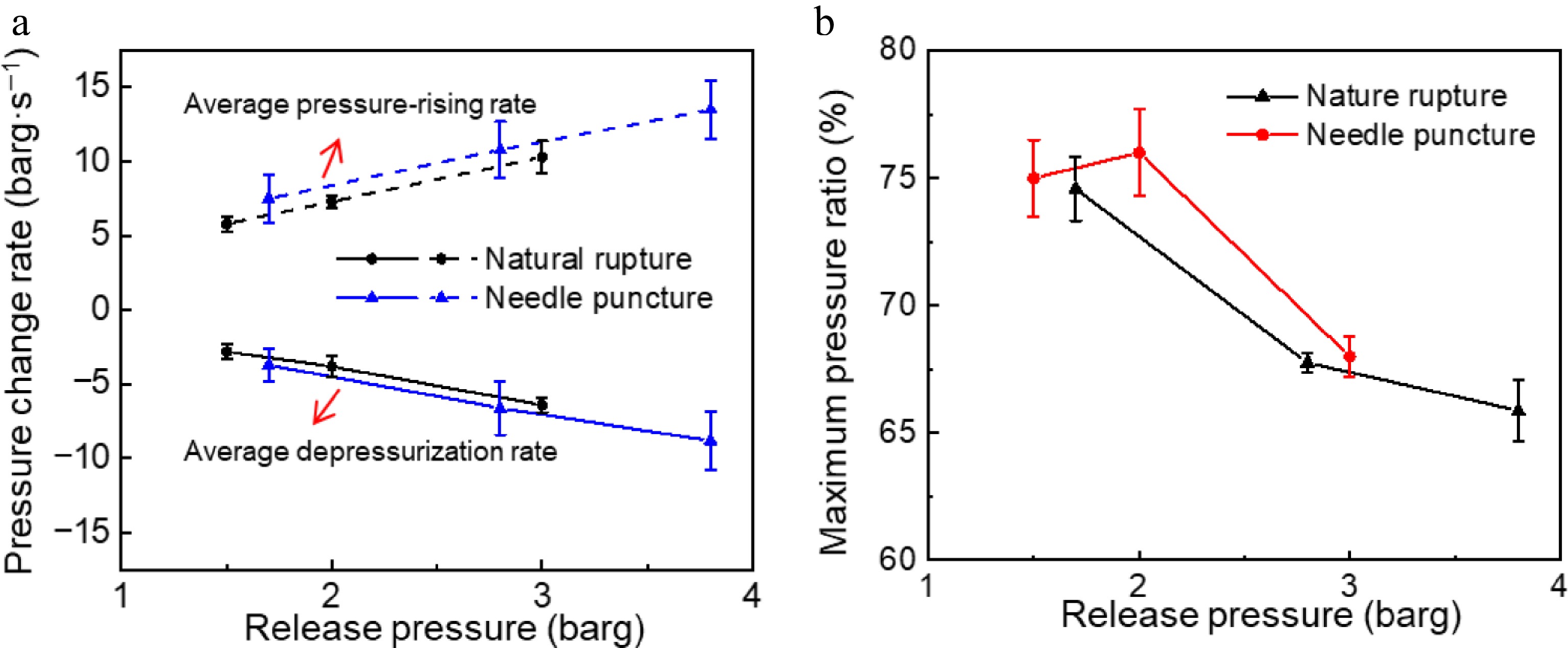

Figure 6 shows the effect of initial superheat on leakage parameters of two tanks under different depressurization modes. The pressure recovery ratio indicates the ratio of the pressure peak to the release pressure, which symbolizes the suppression effect of the explosion-vented tank. When the depressurization mode was natural rupture, under the condition of release pressure from 1.7 to 4.6 barg (the thickness of PET film ranges from 0.025 to 0.1 mm), the storage tank experienced an increase in its average depressurization rate, climbing from 3.2 ± 1.1 to 11.7 ± 2.4 barg·s−1, while the explosion-vented tank demonstrated a rise in its average pressure-rising rate, escalating from 7.5 ± 1.6 to 17.2 ± 2.5 barg·s−1 (see Fig. 6a). When the depressurization mode was natural rupture, PET films with a thickness of 0.025, 0.038, and 0.075 mm were selected to control the release pressure, and the pressures corresponding to the PET film rupture were 1.5, 2, and 3 barg, respectively. The storage tank saw its average depressurization rate rise from 2.8 to 6.4 barg·s−1, whereas the explosion-vented tank experienced an increase in its average pressure-rising rate, climbing from 5.8 to 10.3 barg·s−1 (see Fig. 6a). Further analysis of the release pressure of 1.7 to 3.8 barg in the natural rupture experiment showed the average depressurization rate increased from 3.2 to 6.6 barg·s−1 (Fig. 5a), indicating that the average depressurization rate was lower compared to the needle puncture. The results show that the two-phase flow leakage velocity of natural rupture is faster than that of needle puncture. Under all pressure relief conditions, the average pressurization rate consistently exceeds the average depressurization rate. This phenomenon results from the synergistic actions of gas flow and the vaporization of two-phase flow.

Figure 6.

The effect of initial superheat on leakage parameters of storage tank and explosion-vented tank under different depressurization modes.

From Fig. 6b, as the release pressure increases, the pressure recovery ratio exhibits a gradual decline, but the decreasing trend becomes stable. This is because when the PET film thickness is more than 0.038 mm, the decrease in crack area results in a lower actual effective leakage velocity (see Fig. 10), which in turn causes a notable decline in the rate of decompression. But the depressurization of the medium directly determines the superheat degree, which means that the thicker PET films have a lower superheat degree of the liquid during the pressure depressurization process. A reduced level of superheat leads to diminished expansion of the bubbles and accelerated energy dissipation. Consequently, only a portion of the medium vaporizes inside the tank, leading to a diminished pressure rise tendency. However, under the needle puncture depressurization mode, the pressure recovery ratio initially increases and then decreases with rising release pressure. This occurs because a release pressure of 1.5 barg exhibits a higher initial leakage velocity compared to 2 barg, indicating that the explosion-vented tank exerts a more pronounced suppression effect at 1.5 barg. In addition, the volume also exerts an influence on the pressure recovery ratio.

Bubble motion and two-phase flow evolution

-

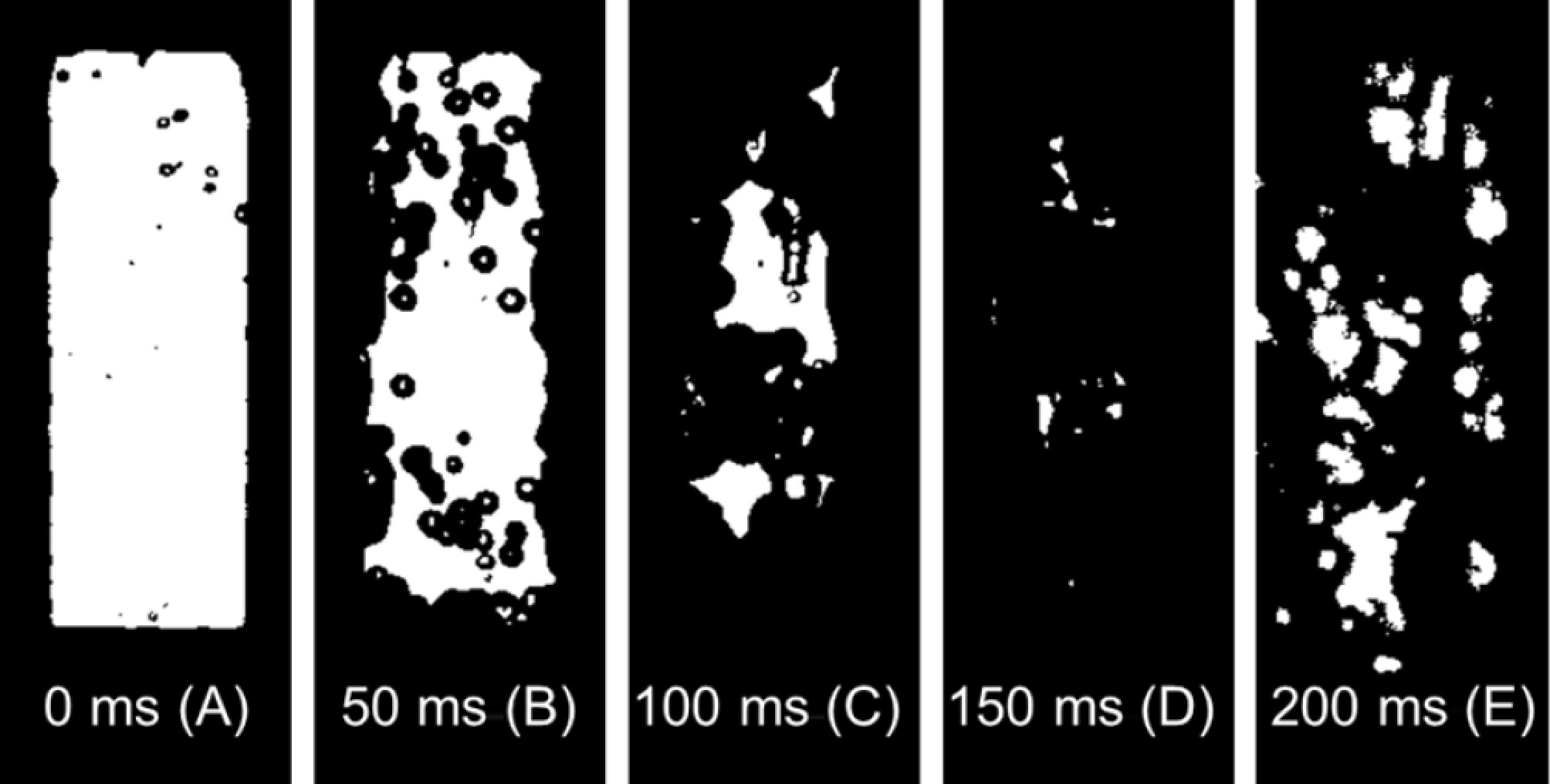

In Fig. 3b, neither the natural rupture test nor the needle puncture test exhibits pressure rebounds when the fracture is in the gas phase. Figure 7 shows the evolution of two-phase flow within the medium, where depressurization is precisely regulated via needle puncture. From points A to C, the tank pressure declines steadily. The depressurization rate is only 6.4 barg·s−1 (between points A and C), which is significantly lower than the depressurization rate required for pressure rebound to occur[25]. From point C to point D, as the pressure continues to drop, the upward motion of the two-phase flow blurs the high-speed visualization. Once the pressure falls to point E, the boiling intensity of the liquid increases markedly. The bubbles begin to expand faster, and the expanding flow moving down from the liquid surface impedes the movement of the leaking flow (high-speed visualization is restored). At this time, an equilibrium is achieved between rapid expansion and intense leakage, leading to stabilized pressure without observable recovery. Subsequently, the downward expansion flow subsides, while the depressurization rate accelerates markedly.

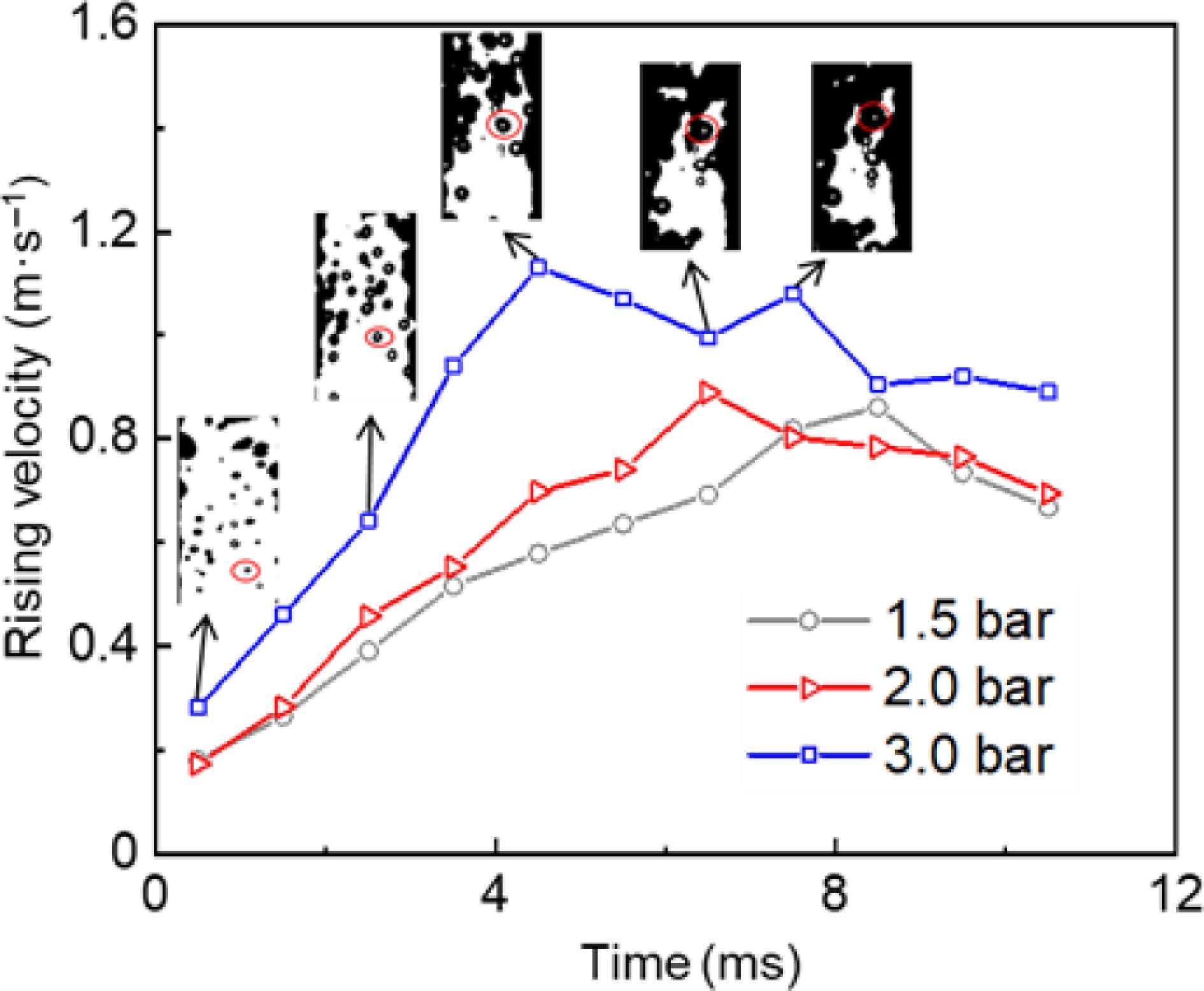

To further investigate bubble dynamics, a monitoring point was established within the storage tank, with time zero defined as the initial movement of observable microbubbles within the medium. Figure 8 shows variations in bubble ascent velocity at different release pressures under the needle puncture. The bubble rise velocity generally exhibited an initial increase followed by a progressive decrease until bubble rupture or coalescence occurred.

During the rising stage, the relationship between the bubble rising velocity and the release pressure is divided into two regimes. Before 1.6 ms, the bubble rise rate is almost unaffected by the release pressure due to the larger leak velocity at the release pressure of 1.5 barg in Fig. 9. Then, as the release pressure continues to increase, more energy will be released, accelerating the rising speed of the bubbles. Thereafter, the pressure gradient between the two tanks progressively diminishes over time, thereby hindering bubble expansion and resulting in a decrease in the deceleration of bubble ascent. A clear correlation exists between initial pressure and bubble ascent rate, as higher initial pressures result in a faster bubble rising velocity and an earlier onset of declining speed.

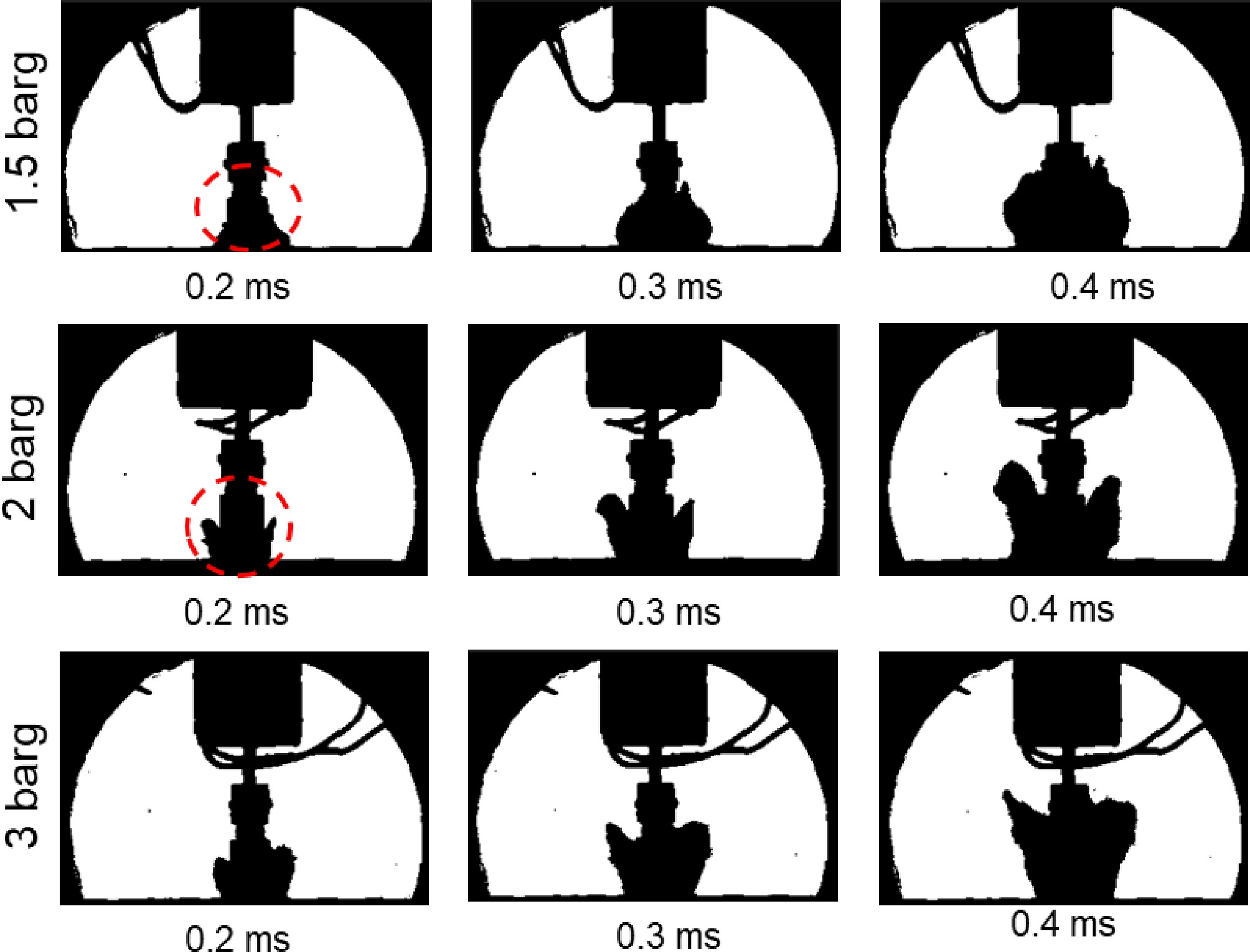

Figure 9 illustrates the two-phase flow leakage process within 0.4 ms of needle puncture, in the depressurization mode under different release pressures. When the release pressure is 1.5 barg (0.025 mm thick PET film), the pressure gradient between the needle puncture and natural rupture of the PET film is 0.2 barg (see Table 1). The initial jet shape of the two-phase flow is a bun shape (narrow top and wide bottom), which has a large leakage velocity. As the release pressure increases to 2 and 3 barg, the pressure gradient between the needle puncture and natural rupture is 0.4 and 0.8 barg, respectively. The initial jet shape of the two-phase flow is Y-shaped (wide top and narrow bottom).

The results indicate that the depressurization rate of natural rupture is higher compared to needle puncture since natural rupture facilitates a complete fracture for initial gas phase leakage (as depicted in Fig. 3), thereby resulting in a faster response time to rapid depressurization. Increased release pressure hastens the initiation of buffering effects. This phenomenon results from enhanced vaporization saturation rates under higher superheat conditions, which effectively suppresses the ejection of bottom-up two-phase flow. Elevated release pressures hasten the activation of pressure buffering in the explosion-vented tank[18,26]. The changes of vapor morphology in Fig. 9 indicate the impact of the needle structure on the shock wave. From the perspective of vapor injection rate, the cone structure can reduce the intensity of the initial shock wave. How to quantify the effect however needs further verification in future work.

PET film thickness vs pressure

-

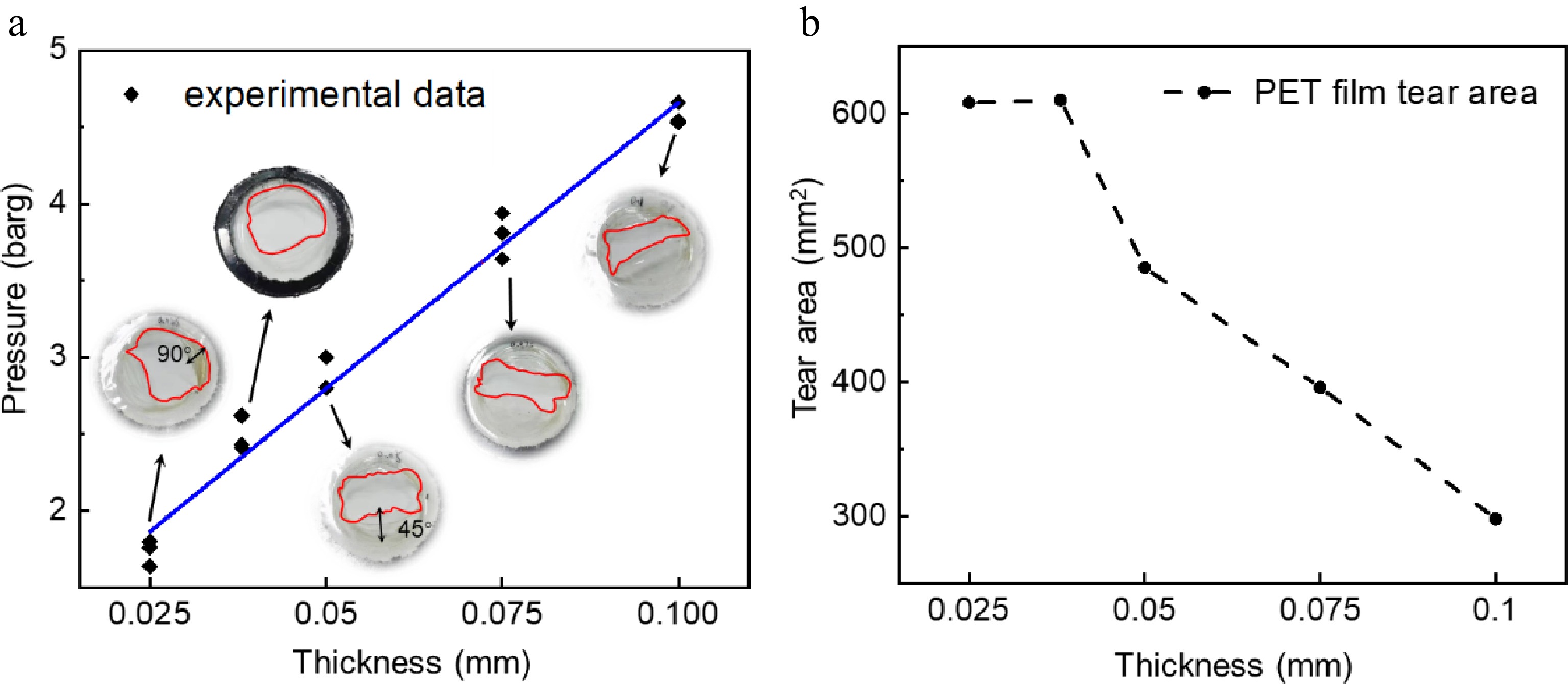

Figure 10 shows the rupture pressure, and tear area of PET films of different thicknesses under 70% fill level and 9.6 cm2 discharge area. In the heating stage, the continuous heating of the internal liquid increases the pressure inside the tank. When the pressure reaches the maximum extent that the PET film can withstand to produce a crack, and gradually expands due to the two-phase flow impact. Cracks form when the tank pressure exceeds the PET film's limit, then gradually propagate due to two-phase flow impact. This is similar to the failure form of the weak part of the tank, and suitable for simulating the real pressure limit leakage test of the tank. From Fig. 10a, the PET film thickness has a linear relationship with the release pressure. Therefore, a thicker PET film can represent a greater initial superheat.

Figure 10b shows the area of the crack generated by the simulated weak link in the PET film with different thicknesses. Significant variations exist in the opening size of the crack formed during the rupture of PET films with differing thicknesses. When the thickness of the PET film is 0.025 and 0.038 mm (as shown in Fig. 10a), the PET film is almost completely torn, and the tear shape is similar to that of a circle. However, when the thickness of the PET film is more than 0.038 mm, the tear area gradually decreases with the increase of the thickness, and the tear shape is approximately rectangular. Therefore, the tearing force action on the PET film is directly generated by the medium inside the tank. Once the internal pressure attains the film's rupture threshold, the expansion work from liquid boiling drives the tearing process. For thinner PET films, pressure drops rapidly, inducing intense superheated boiling. Two-phase flow acts on weak points, further propagating cracks and widening the tear to nearly 90°. For thicker PET films, the released two-phase flow contains more gas than liquid, significantly increasing leakage rates. However, the tear opening angle remains smaller (less than 45°), drastically reducing the effective depressurization area. As a result, the peak pressure ratio stabilizes and gradually declines (see Fig. 6b).

The PET film simulated leakage port, the opening area is relatively small in the process of rapid depressurization, and the process of gas ejection is relatively choked. After the pressure in the tank is reduced to a certain extent, the liquid medium will become superheated and evaporate. Liquid evaporation is a transient process of considerable complexity, making it challenging to quantify both the liquid mass expended during evaporation and the resultant vapor output. Therefore, the supplementary effect of liquid evaporation on pressure is not considered in the calculation process. The calculation of mass flow rate and pressure in the tank during the step-down stage can be obtained as follows[27]:

$ Q=AP\sqrt{\frac{rM}{R{T}_{0}}{\left(\dfrac{2}{r+1}\right)}^{r+1/r-1}} $ (1) where, Q is the mass flow rate, A is the discharge area, r is the adiabatic index of the gas mixture, M is the molar mass of the gas mixture, R is the parameter of the equation of state of the gas, and T0 is the initial temperature.

When the medium is discharged outwards, the pressure in the tank can be calculated by the ideal gas equation of state:

$ P=(m_g)RT_0/MV $ (2) where, V is the gas phase volume, and mg is the mass of residual gas in the storage tank

As can be seen from Eqs (1) and (2), the pressure within both tanks exhibits a direct proportionality to the liquid injection mass flow rate. However, as the degree of superheat increases, greater energy dissipation occurs through the vented tank walls, which subsequently attenuates the pressure rise trend. Moreover, the effective pressure depressurization area decreases as superheat increases, resulting in nonlinear variations in both pressure and liquid mass flow rate inside the tank under natural rupture depressurization conditions. This also explains why, in Fig. 6b, the pressure recovery ratio initially decreases before stabilizing with increasing initial pressure under the natural rupture depressurization mode.

-

In the past, research on BLEVE primarily focused on rapid pressure changes in open spaces, with little consideration given to the influence of confined spaces on BLEVE. This paper explores the consequences of superheated liquid releases under confined conditions. It is found that the rapid pressure depressurization process occurs in confined spaces without pressure recovery. Moreover, the explosive boiling intensity of weak link leakage and needle puncture leakage is different, which results in a difference depressurization rate between the two rupture modes. This supplements existing research findings in this field and provides data references and support for subsequent researchers. In industrial applications, liquefied gas tanks are frequently installed in enclosed environments, such as buildings and underground tunnels, conditions that substantially influence superheated liquid boiling behavior within the containers, consequently mitigating potential hazards. The investigation into confined space effects on superheated liquid boiling therefore carries significant implications, providing a scientific basis for accident forensics, risk assessment, and preventive measures. However, the size of the storage tanks used in the experiment differ significantly from those used in actual industrial applications, and the medium used in the experiment is pure water, which makes it difficult for the experimental results to fully reflect the complex situations in real scenarios. Therefore, in response to the above issues, further research is needed to optimize the experimental design and improve their accuracy.

-

This research utilized a precisely controlled experimental apparatus to simulate the leakage behavior of a small storage tank within a confined environment. High-speed imaging techniques were applied to visualize and analyze the transient development of two-phase flow during rupture initiation. The influence of two distinct pressure-driven PET film rupture mechanisms on liquid superheated boiling was examined under varying release pressures in confined conditions. The main experimental conclusions are as follows:

(1) In the case of needle puncture simulating the tank leakage under external action, the smaller thickness PET film has a significant effect on the expansion process in two-phase flow. When the thickness of the PET film is large (more than 0.038 mm), the explosive boiling intensity increases with the thickness of the PET film. It indicates that the leakage outlet dominates the leakage process when the PET film thickness is small. Moreover, the bubble's ascent speed generally follows an initial increase, followed by a decrease, until it either ruptures or coalesces with another bubble.

(2) In the scenario simulating natural rupture-induced tank leakage at existing weak links, the depressurization rate of the storage tank and the pressurization rate of the explosion-vented tank are accelerated, potentially causing higher pressure inside the vented tank chamber than in the storage tank. As the thickness of the PET film increases, the opening angle of the PET film decreases from 90° to 45°, and the effective leakage area decreases. Meanwhile, higher superheat levels result in increased energy dissipation through the explosion-vented tank wall, which suppresses the pressure buildup inside the tank during an explosion. The combination of these two factors results in a decrease in the pressure recovery ratio as the release pressure increases, but the decreasing trend stabilizes.

(3) Under the experimental conditions described in this study, the inhibitory effect of confined spaces of the capacity impeded the upward movement of the leakage flow and reduced the depressurization rate, resulting in no pressure rebound in the tank. The study can offer a valuable preventive approach for mitigating tank leakage incidents within confined space environments.

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant Nos 2016YFC0800100 and 2017YFC0804700).

-

The authors confirm their contributions as follows: overall design of the research: Wang S, Zhai X; research funding and experimental equipment: Wang S; data collection, processing and paper writing: Zhai X, Wei L; review of the results, revision and approvement of the final version of the manuscript: Wang S, Wei L, Pan Y, Jiang J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhai X, Wei L, Wang S, Pan Y, Jiang J. 2025. Study on leakage of superheated liquid in confined space under natural and needle rupture. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e014 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0012

Study on leakage of superheated liquid in confined space under natural and needle rupture

- Received: 18 April 2025

- Revised: 10 June 2025

- Accepted: 25 June 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: Effects of vessel weak link fracture and external impact-induced rupture on the onset of superheated boiling are distinct, and the scientific understanding of these effects remains limited. This study investigates the leakage processes in a small storage tank within a confined environment and compares the effects of natural rupture and needle puncture-induced leakage. Experimental results demonstrated that under the same leakage conditions, the depressurization rate of needle puncture was lower than that of natural rupture. Furthermore, in the needle puncture mode, tank pressure was maintained within the saturated vapor pressure range corresponding to the liquid temperature. In natural rupture mode, pressure exceeded this saturated vapor pressure threshold, initiating bubble formation. As release pressure increased, the bubble rise velocity initially increased, followed by a gradual decline, until the bubbles either ruptured or coalesced during their ascent. The confined space also restricted upward fluid motion, thereby slowing depressurization and preventing pressure rebound. The present study can offer a valuable preventive approach for mitigating tank leakage incidents within confined spaces.

-

Key words:

- Boiling explosion /

- Pressure recovery ratio /

- Confined space /

- Rupture mode