-

In recent years, deep learning methods have gained attraction due to the ability to learn complex patterns and representations from large amounts of data, enabling breakthroughs in challenging tasks in image recognition, natural language processing, and speech processing. However, there are two main constraints of deep learning methods: dependency on extensive labeled data and training costs[1]. Often in genetics, the focused problems only have limited labeled phenotypes with high dimensional genetic data. In these cases, transfer learning has the potential of higher prediction accuracy and test power by the shared parameters from a well-trained deep learning model in a massive source problem. For example, with the vast amounts of genetic data collected from biobank projects, an interesting scientific question is whether these resources can be used to enhance genetic analysis in small-scale studies. A common assumption made by most existing approaches is that two studies should be similar (e.g., the same population). However, this assumption could fail in reality. The study design and study population may differ between the two studies (e.g., Caucasian vs African American).

While transfer learning attempts to improve the performance of target learners on target domains by transferring the model parameters contained in different but related source domains, it does not require data from two studies drawn from the same feature space or the same distribution. It learns possibly useful features from source studies and applies learned features based on focused problems. Therefore, it holds great promise in using the enriched resources from large-scale studies for uncovering novel genetic variants in small-scale studies[2].

In recent years, transfer learning has been investigated in biological and medical fields. For example, a data-driven procedure for transfer learning[3], called Trans-Lasso, was proposed in high-dimensional linear regression and applied to understand gene regulation using Genotype-Tissue Expression data. The transfer learning problem under high-dimensional generalized linear models[4] aimed to improve the fit of target data by borrowing information from useful source data. Although several survey articles[5−7] have reviewed recent developments on transfer learning in machine learning methods, including network-based deep transfer learning which reuses the partial of network pre-trained in the source data, the application of deep transfer learning in genetic data analysis is relatively sparse. The transfer learning in convolutional neural networks[8] was developed to predict the progression-free interval of lung cancer with gene expression data. A pipeline of transfer learning for genotype-phenotype prediction[9] was studied using deep learning models with a small number of genotypes.

Given that the transfer methods depend on the models or algorithms being used to learn the tasks, we propose to integrate the idea of transfer learning into deep neural networks for prediction and association analyses with high dimensional genetic data. For example, deep neural networks can be trained in the large-scale UK Biobank dataset for nicotine dependence and transfer the parameter weights to facilitate genetic analysis in small-scale studies. By integrating transfer learning into deep neural networks, we are able to transfer model parameters regarding complex genotype-phenotype relationships (e.g., gene-gene interactions) between two studies.

Besides the proposed predictive modeling using transfer learning in deep neural networks, we further develop a permutation-based association test to detect significant genes in the targeted problem based on the proposed transfer learning. The resulting p-values can be interpreted as a measure of feature importance, and they help decide the significance of variables and therefore improve model interpretability[10−12]. The permutation-based association test using transfer learning shows higher statistical power compared to that without transfer learning in two case studies. Moreover, the permuted data is obtained via randomly shuffling the index of subjects while maintaining their intrinsic genetic structures, hence no model re-fitting is needed which greatly reduces the computation cost.

-

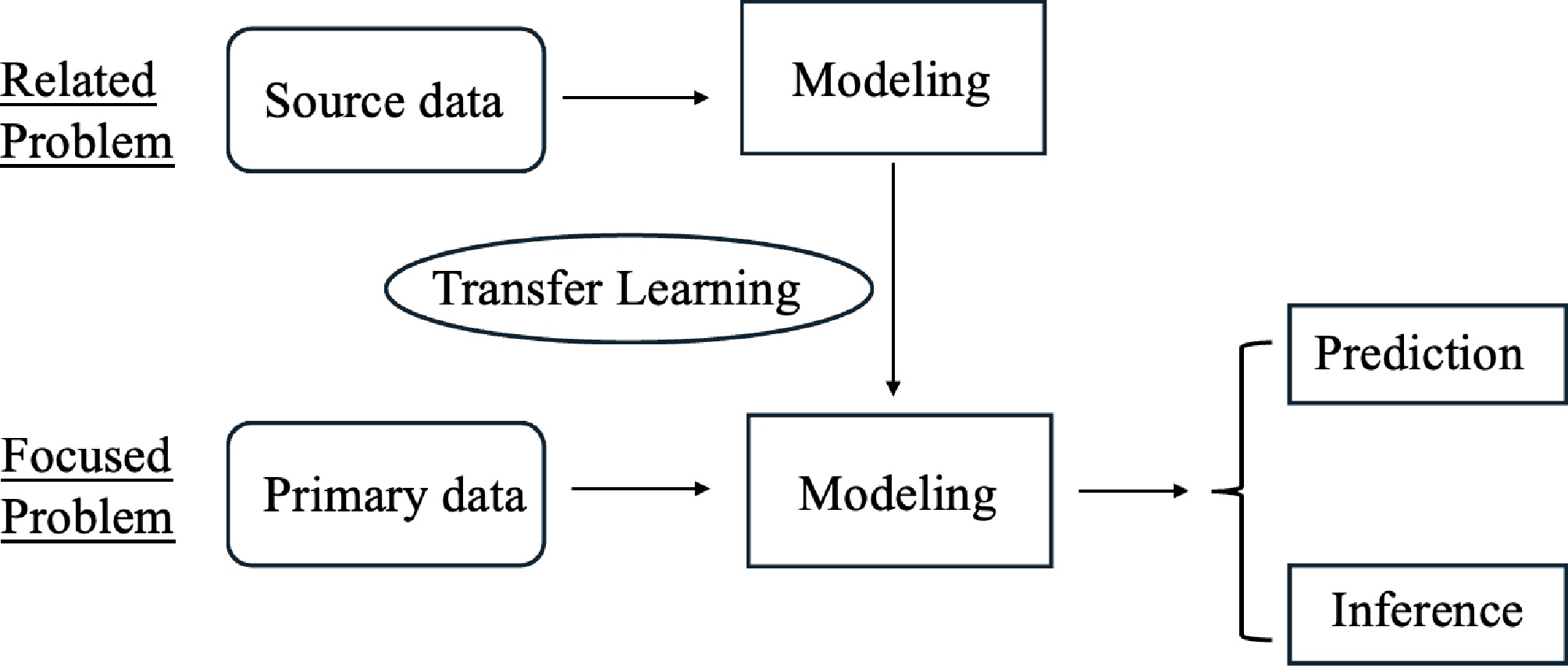

Transfer learning applies model parameters gained from one research problem to a different but related problem, and has been widely used in text and image recognition. The basic idea of transfer learning is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

An illustration of transfer learning. The goal is to build predictive models and conduct inference in the primary data for the focused problem. The modeling parameters learned from the source data of a related problem are transferred to the modeling process in the primary problem.

In this paper, we illustrate transfer learning in the deep neural networks (DNN) model. In this section, we briefly introduce the DNN model and then integrate the idea transfer learning into DNN (TL-DNN) between two datasets. To distinguish the different data types in the following sections, we use lowercase letters, bold lowercase letters, and uppercase letters to denote scalar, vector, and matrix, respectively.

Deep neural networks

-

Suppose our research interest is to find a predictive function f that models the continuous response variable y and predictor variable x = (x1, ..., xq), where q is the dimension of input. The true model is written as:

$ y=f(\boldsymbol{x})+\epsilon $ where,

$\epsilon$ $ \begin{array}{l}\boldsymbol{h}_1=\sigma(W_1\boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{b}_1) \\ \boldsymbol{h}_d=\sigma(W_d\boldsymbol{h}_{d-1}+\boldsymbol{b}_d),\quad d=2,\dots,l-1 \\ \ \ \hat{y}=\hat{f}(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{w}_l\boldsymbol{h}_{l-1}\end{array} $ where, hd is the hidden layer learned from the primary study and has a dimension of md,

$\sigma$ $\sigma(x) = \dfrac{1}{1+e^{-x}}$ In DNN, we first normalize the response variable y. Suppose that

$\bar{y}$ $\bar{v}$ $ \hat{y}=\hat{f}(\boldsymbol{x})=\overline{v}\boldsymbol{w}_l\boldsymbol{h}_{l-1}+\overline{y} $ For simplicity, we her focus on the regression problem and use the L2 loss and mean square error (MSE) to estimate parameters and evaluate the model performance. It can be easily extended to the classification problem, and other loss functions (e.g., cross-entropy loss) and measurements (e.g., misclassification error) can be used.

In genetic studies, genetic effects are usually smaller than the noise, and therefore heavy penalties are required to avoid overfitting. Various regularization methods, such as penalty regularization, dropout method, and early stopping method, can be used. In this paper, we impose two parameter regularization forms defined below: the square regularization p1(S;λ) and the group Lasso regularization[13] p2(S;λ), where, λ is a hyperparameter controlling the solution space.

$ \begin{array}{l} p_1({\boldsymbol{S}}; \lambda) = \lambda \Big(\sum\limits_{d = 1}^{l-1} \|W_d\|_2^2 + \|{\boldsymbol{w}}_l\|_2^2\Big) \\ p_2({\boldsymbol{S}}; \lambda) = \lambda \Big(\sum\limits_{d = 1}^{l-1}Q(W_d)+Q({\boldsymbol{w}}_l)\Big) \\ Q({\boldsymbol{z}}) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \Vert{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\Vert, & \rm{for} & \Vert{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\Vert \geq \alpha \\ \dfrac{\Vert{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\Vert^2}{2\alpha} + \dfrac{\alpha}{2}, & \rm{for} & \Vert{{\boldsymbol{z}}}\Vert \lt \alpha \end{array}\right., \, \alpha = 1e^{-3} \end{array}$ (1) In the following, we apply p1(S;λ) for the prediction step while p2(S;λ) is used in the association test. Therefore, the solution to the DNN framework is defined as:

$ \hat{\boldsymbol{S}}=arg\min\limits_{\boldsymbol{S}}\left(\dfrac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{i=1}^n(y_i-f(\boldsymbol{x}_i))^2+p(\boldsymbol{S};\lambda)\right) $ The backpropagation method is typically used to obtain the solution. The selection of hyperparameter λ is discussed in the following section.

Transfer learning in deep neural networks

-

If we have a source dataset (e.g., UK biobank), in which we model the response variable y' with predictor variable

${\boldsymbol{x}}' = (x_1', \dots, x_q')$ $ {\boldsymbol{h}}_1' = \sigma(W_1' {\boldsymbol{x'}} + {\boldsymbol{b}}_1'), $ (2) $ {\boldsymbol{h}}_d' = \sigma(W_d' {\boldsymbol{h}}_{d-1}' + {\boldsymbol{b}}_{d}'), \quad d = 2,\dots,l-1, $ (3) $ \hat{y}' = \hat{f}'({\boldsymbol{x}}') = \bar{v}' {\boldsymbol{w}}_l' {\boldsymbol{h}}_{l-1}' + \bar{y}', $ (4) where,

$\bar{y}'$ $\bar{v}'$ $\hat{\boldsymbol{S'}}$ To prepare for the transfer learning, we divide the solution

$\hat{\boldsymbol{S'}}$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1' = \{\hat{W}_d', \hat{{\boldsymbol{b}}}_{d}' | d = 1,\dots,l-1\}$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2' = \{\hat{{\boldsymbol{w}}}_{l}'\}$ ${\boldsymbol{h}}_{l-1}'$ ${\boldsymbol{h}}_{l-1}'$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1'$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2'$ ${\boldsymbol{h}}_{l-1}'$ $f_1'$ $f_2'$ $ \boldsymbol{h}_{l-1}'=f_1'(\boldsymbol{x'}|\hat{\boldsymbol{S}}_1'),\qquad\hat{y}'=f_2'(\boldsymbol{h}_{l-1}'|\hat{\boldsymbol{S}}_2') $ Similarly, the parameter set

$\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2$ $p({\boldsymbol{S}}_1, {\boldsymbol{S}}_2; \lambda)$ After training the deep neural network in the related problem, we now apply transfer learning using

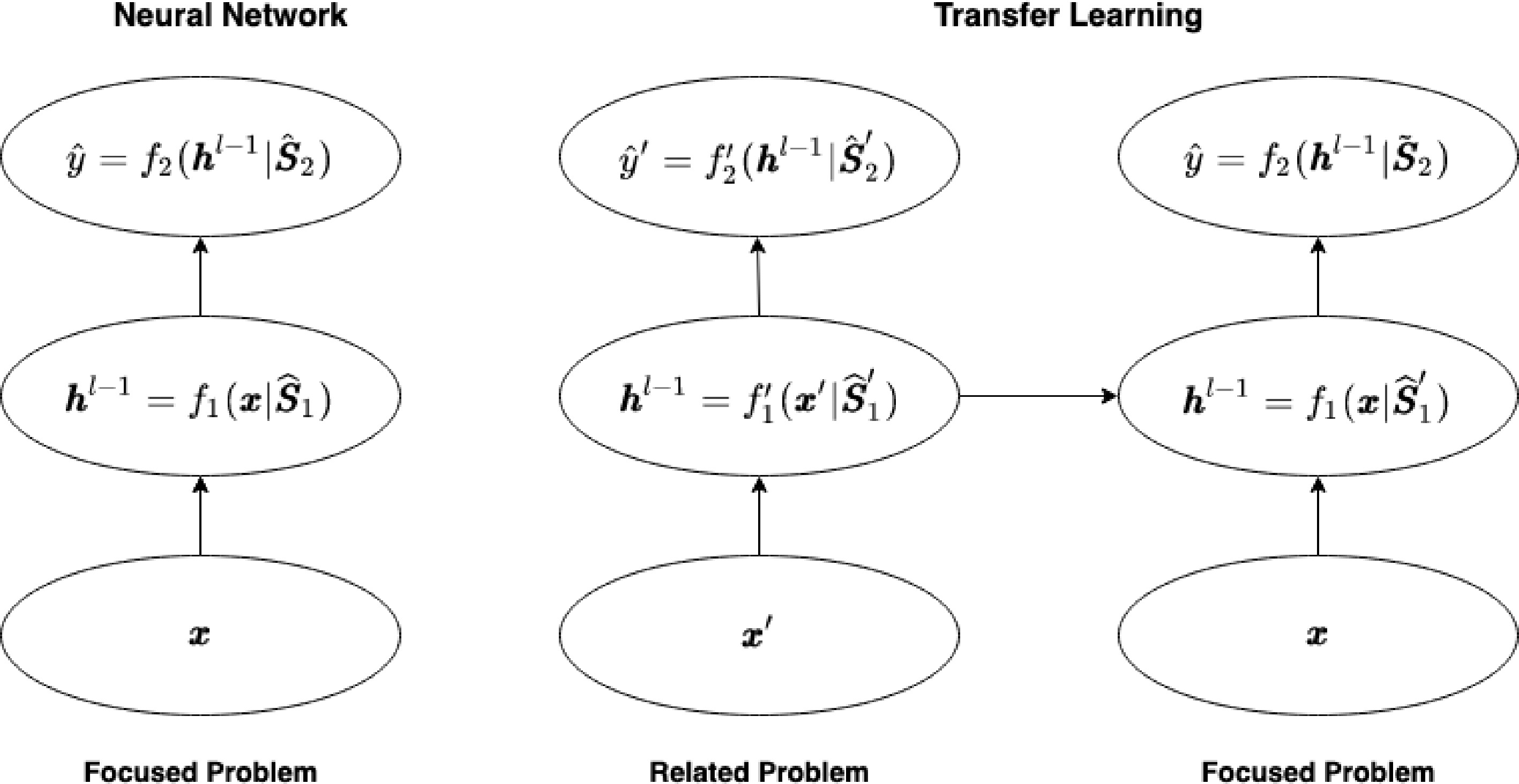

$\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1'$ $\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1'$ $ \begin{array}{l} \widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1 \equiv \hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1 = \arg\min\limits_{{\boldsymbol{S}}_1, {\boldsymbol{S}}_2} \Bigg(\dfrac{1}{n}\displaystyle\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n}(y'_i - f'({\boldsymbol{x}}_i'))^2 + p({\boldsymbol{S}}_1, {\boldsymbol{S}}_2; \lambda) \Bigg) \\ \widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2 = \arg\min\limits_{{\boldsymbol{S}}_2} \Bigg(\dfrac{1}{n}\displaystyle\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n}(y_i - f({\boldsymbol{x}}_i|{\boldsymbol{S}}_1 = \widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1))^2 + p(\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, {\boldsymbol{S}}_2; \lambda)\Bigg) \end{array} $ (5) The transfer learning method based on the deep neural networks is illustrated in Fig. 2 in comparison to the direct application of deep neural networks in the focused problem.

Figure 2.

Transfer learning in deep neural networks. The left panel shows the application of neural networks in the focused problem while the right panel displays the proposed transfer learning method based on training the neural networks in the related problem. Here $ \hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1' $ are the transferred weight parameters in hidden layers. The output layer weights $ \tilde{\boldsymbol{S}}_2 $ are updated during the training while $ \hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1' $ are frozen.

We apply the Adam algorithm[15] for optimization in Eqn (5). The backpropagation procedure is implemented as:

$ \begin{array}{l}c(\boldsymbol{S})=\dfrac{1}{n}\displaystyle\sum\limits_{i=1}^n(y_i-f(\boldsymbol{x}_i))^2+p(\boldsymbol{S}_1,\boldsymbol{S}_2;\lambda) \\ \ \ \ \ s\gets s-r_1\dfrac{\partial c(\boldsymbol{S})}{\partial s},\quad s\in\boldsymbol{S}_1 \\ \ \ \ \ s\gets s-r_2\dfrac{\partial c(\boldsymbol{S})}{\partial s},\quad s\in\boldsymbol{S}_2\end{array} $ where, r1 and r2 are the learning rates of S1 and S2, respectively.

The Adam algorithm is an adaptive optimization method in which the learning rate is determined element-wise. While the default setting of the Adam algorithm works well in most cases, it is not suitable for genetic studies. Due to the heavy penalty in the last layer, the solution of S can be too small compared to the default learning rate of the Adam algorithm. Therefore, we set the learning rate parameter based on λ while keeping other parameters as the default value. The iteration process stops when MSE does not decrease for 3,000 epochs. In the next section, we set l = 3, and the numbers of hidden units of each layer are 16 and 4.

For modeling performance comparison, we add a baseline model, which is essentially the mean value of the response variable

$ \bar{y} $ $ R^2_{pseudo} = 1- \dfrac{MSE(f)}{MSE(\bar y)} = 1 - \dfrac{\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n}(y_i - f({\boldsymbol{x}}_i))^2}{\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n}(y_i - \bar{y})^2} $ (6) The larger the value of

$ R^2_{pseudo} $ Permutation-based association test using transfer learning

-

Based on the proposed deep transfer learning approach, we further develop a permutation-based association test, called PT-TL-DNN, to identify significant genes for different phenotypes. We adapt the feature selection method[12] and the test procedure is defined as follows. Assume that x is the candidate gene/region to be tested for association with disease Y and we denote

$ f({\boldsymbol{x}}|\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{S}}_2) $ $ \Delta = \dfrac{1}{K}\sum\limits_{k = 1}^K \Delta_{k} = \dfrac{1}{K}\sum\limits_{k = 1}^K\sum\limits_{i\in D_{k,2}} \Big\{L(y_i,f_{k}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}|\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{S}}_2)) - E\Big[L(y_i,f_{k}({\boldsymbol{x}}_i'|\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{S}}_2))\Big]\Big\} $ where,

$ {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}' $ $ E\big[L(y_i,f_{k}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}'|\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{S}}_2))\big] $ $ \Delta $ $ \Delta $ $ H_0:\Delta\ge0\qquad vs.\qquad H_a:\Delta \lt 0 $ Under H0, it was shown that

$ \Delta \sim N(0,\sigma^2) $ $ \sigma^2 $ During the TL-DNN model training before the permutation step, we apply the smooth group Lasso regularization p2 defined in Eqn (1). Compared to the square regularization, the smooth group Lasso regularization can provide structured sparsity and allow the entire group of features to be removed, which may benefit the permutation testing when we test all variants together as a gene. The regularization parameter is denoted as λSGL to distinguish it from the previous square penalty parameter. The parameter λSGL is selected from the set {0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10}. The detailed algorithm of the PT-TL-DNN is described in Table 1.

Table 1. Algorithm for the permutation-based association test using transfer learning.

Permutation-based test using transfer learning with K-fold cross-validation Input: Genetic variants of a gene x, Phenotype y, a set of candidate smooth Group Lasso regularization parameters λSGL. Output: Empirical p-value of the gene Step 1: Construct a TL-DNN model f(x) with 2 hidden layers. Step 2: For k $ \leftarrow $ 1, ..., K do 1: Split (xtrain, ytrain), (xtest, ytest). For each λi in λ do a: Input (xtrain, ytrain) and train f(xtrain, ytrain;λi) with smooth Group Lasso regularization parameter λi, output $ \hat{f} $. b: Evaluate Mean Square Error on (xtrain, ytrain) , $ MSE(y_{test},\hat{f}(x_{test};\lambda_i)) $. end. 2: Choose λopt with the lowest MSE, output $ \hat y_{test} = \hat{f}(x_{test};\lambda_{opt}) $ and calculate $ MSE(y_{test}, \hat{f}(x_{test};\lambda_{opt})) $. 3: Permute $ x_{test} $ by row, denoted as $ x_{test}' $, calculate $ \hat y_{test}' = \hat{f}(x_{test}';\lambda_{opt}) $, $ MSE(y_{test}, \hat y'_{test}) $ and $ l = MSE(y_{test}, \hat y_{test})-MSE(y_{test}, \hat y_{test}') $. 4: Repeat 3 for B times, obtain $ l_1,...,l_B $. Calculate $ \Delta_k = \frac{1}{B}\sum_{b = 1}^{B}l_b $ and $ \hat{\sigma}_k^2 = var(l_1,...,l_B) $. end. Step 3: Calculate statistic $ \Delta = \frac{1}{K}\sum\Delta_k $ with limiting distribution $ N(0, \sigma^2 = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{1}^{K} \sigma_k^2) $, calculate and output p value. end. For comparison, we also perform the permutation-based association test using the direct application of deep neural networks (PT-DNN) in the focused problem. In other words, we replace the transfer learning predictive model

$ f_{k}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}|\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widetilde{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2) $ $ f_{k}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}|\widehat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_1, \widehat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_2) $ The advantage of the proposed test lies in the predictability of the transfer learning method using the candidate gene. On the one hand, when the transfer learning exhibits higher prediction accuracy, it can further reduce the value of the first loss function in

$ \Delta $ $ \sigma^2 $ -

In this section, we apply the proposed transfer learning method and the association test to investigate the relationships between nicotine addiction and candidate genes based on two relevant projects. Specifically, we conducted two transfer learning case studies: a cross-project case study and a cross-ethnicity case study. We show that TL with large-scale data sets helps improve predictive accuracy and gene selection.

Data description

-

Cigarette smoking is one of the leading causes of preventable disease, contributing to 5 million deaths worldwide each year[16]. During the last decade, a great deal of progress has been made in identifying genetic variants associated with smoking. Among those findings, the nAChRs subunit genes (e.g., CHRNA5) have been identified and confirmed in several large-scale studies[17]. In this application, we apply the proposed transfer learning to study the complex relationships between the nAChRs subunit genes and nicotine dependence.

The datasets to be analyzed are the large-scale UK Biobank (UKB) dataset and the relatively small-scale dataset from the Study of Addiction: Genetics and Environment (SAGE). UKB is a population-based prospective cohort of nearly 500,000 individuals recruited in the United Kingdom who were aged 40−69 years. UKB contains a wealth of data on detailed clinical information, genome-wide genotype data, and whole-exome sequencing data[18]. SAGE is one of the most comprehensive studies conducted to date, aimed at discovering genetic contributions to substance use disorders. It included about 4,000 participants to study the genetic association with multiple phenotypes, including alcohol, nicotine, and other drug dependence. For the focus of our gene-based analysis, we used cigarettes per day (CPD), available in both SAGE and UKB, as the phenotype and considered genes from two clusters, CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4[19] and CHRNB3-CHRNA6[20] that are associated with nicotine dependence. Before the analysis, we re-assessed the quality of the data (e.g., checking for successful genotype calls, missing rates, deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and unexpected relationships).

Two studies of transfer learning are investigated in this section. One is a cross-project study and the other is a cross-ethnicity study. In the first study, we apply the transfer learning from the white British population to the black and the white Irish populations. In the second study, we transfer the model trained from UKB to SAGE to demonstrate the performance of the transfer learning approach.

To illustrate the implementation and evaluation of the transfer learning procedure, we split the dataset into the train set (80%) and the test set (20%). We train the original NN model using the source data, transfer the trained model to the train set, and compare their performance on the test set. To avoid chance findings due to the data splitting, we repeat the random splitting 100 times, train the model on the train set of each split, and then average the evaluation metrics on the test sets to assess model performance more reliably. A validation process is used to determine the value of λ. In the validation process, we split our train set into the subtrain and validation sets with a ratio of 4:1. We evaluate a range of possible values of λ, in the subtrain set, and then select the optimal λ based on the validation set. After a careful quality assessment, the hyperparameter we consider for lambda is {10−1, 10−0.5, 1, 100.5, 101}. The learning rates r1 and r2 are both set as 10−3. The initial values of parameters are generated by a normal distribution whose mean and standard deviation are 0 and 10−3, respectively.

Cross-project transfer learning

-

In this section, we transfer the model parameters from the large-scale UKB data to the relatively small-scale SAGE data. For this analysis, we focus on the Caucasian population in both datasets. The sample sizes of the population are 288,039 in UKB and 2,517 in SAGE.

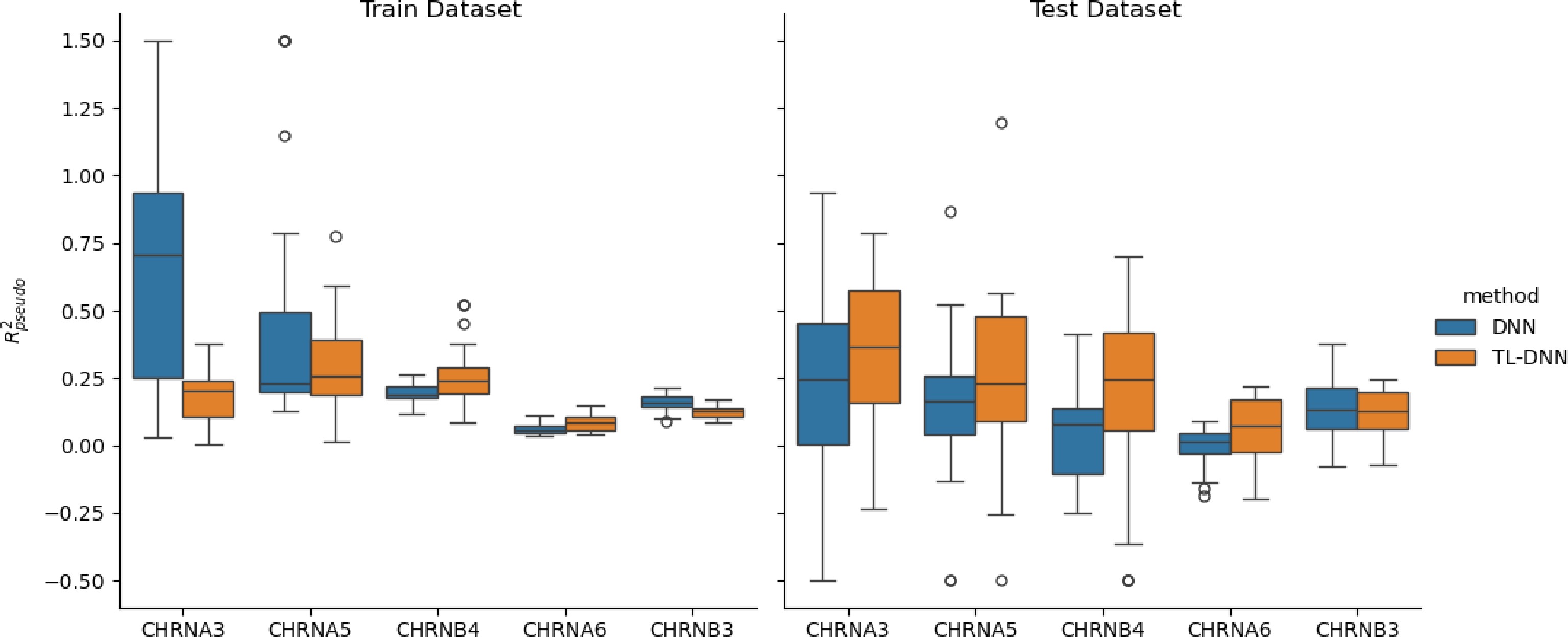

For model prediction performance, we compute the relative efficiency criterion

$ R^2_{pseudo} $

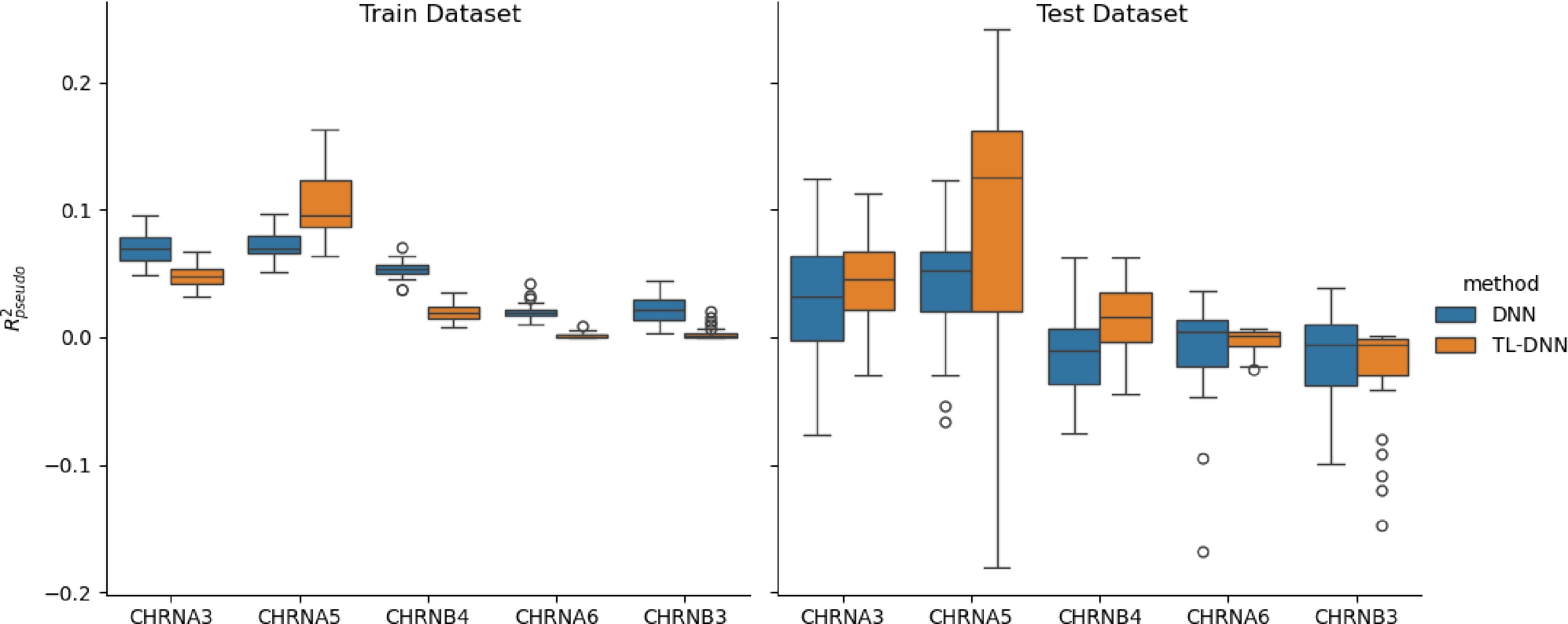

Figure 3.

Prediction comparison regarding relative efficiency in the SAGE data set between the transfer learning (TL-DNN) from UK Biobank and the direct application of DNN without transfer learning.

As we can see from Fig. 3, the TL-DNN model outperforms the DNN with higher prediction efficiency in the test set for all five candidate genes. The TL-DNN also shows its robustness to overfitting while the DNN suffers from overfitting for most genes.

The permutation-based association test is used to evaluate the association of the five candidate genes for nicotine dependence. Table 2 summarizes the results of the PT-DNN applied in the UKB Caucasian data, indicating all five candidate genes are associated with nicotine dependence at the significance level of 0.05.

Table 2. PT-DNN results from the association of the five candidate genes in the UKB Caucasian sample.

Gene $ \Delta $ $ \hat\sigma $ p-value CHRNA3 −1.33e−3 1.10e−4 0 CHRNA5 −1.13e−3 1.01e−4 0 CHRNA6 −8.24e−5 3.19e−5 4.88e−3 CHRNB3 −1.20e−4 4.13e−5 2.19e−3 CHRNB4 −1.4e−3 1.11e−4 0 When testing the genetic associations in the smaller SAGE data set, as shown in Table 3, PT-DNN without the transfer learning step identified four candidate genes but failed to identify CHRNB4 (p-value = 0.636); with the transfer learning step, PT-TL-DNN identified that all five genes are significantly associated with nicotine dependence with CHRNB4 having a p-value of 0.0256. Moreover, PT-TL-DNN provided smaller p-values for all genes except CHRNB3 compared to PT-DNN. It is also found that PT-TL-DNN yielded smaller estimated standard deviations

$ \hat\sigma $ Table 3. Comparison between the permutation-based test without transfer learning (PT-DNN) and with transfer learning (PT-TL-DNN) in the SAGE data set.

Gene PT-DNN PT-TL-DNN $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value CHRNA3 −0.0112 3.81e−3 1.66e−3 −8.28e−3 2.78e−3 1.48e−3 CHRNA5 −8.64e−3 3.63e−3 8.58e−3 −7.79e−3 3.26e−3 8.41e−3 CHRNA6 −9.16e−3 3.18e−3 1.97e−3 −6.54e−3 2.26e−3 1.91e−3 CHRNB3 −0.0139 3.20e−3 7.35e−6 −7.75e−3 2.53e−3 1.09e−3 CHRNB4 4.85e−8 1.39e−7 0.636 −5.15e−3 2.64e−3 0.0256 Cross-ethnicity transfer learning

-

The vast amount of genetic data collected from the Caucasian population provides us with a great resource for genetic research in other populations, especially minority populations. In the UKB dataset, there are 271,240 white British, 7,349 white Irish, and 6,219 black. In this case study, our target populations are the white Irish population and the black population, while the white British population is used as the source population. We transfer the model parameters trained from the white British population to either the white Irish or black population.

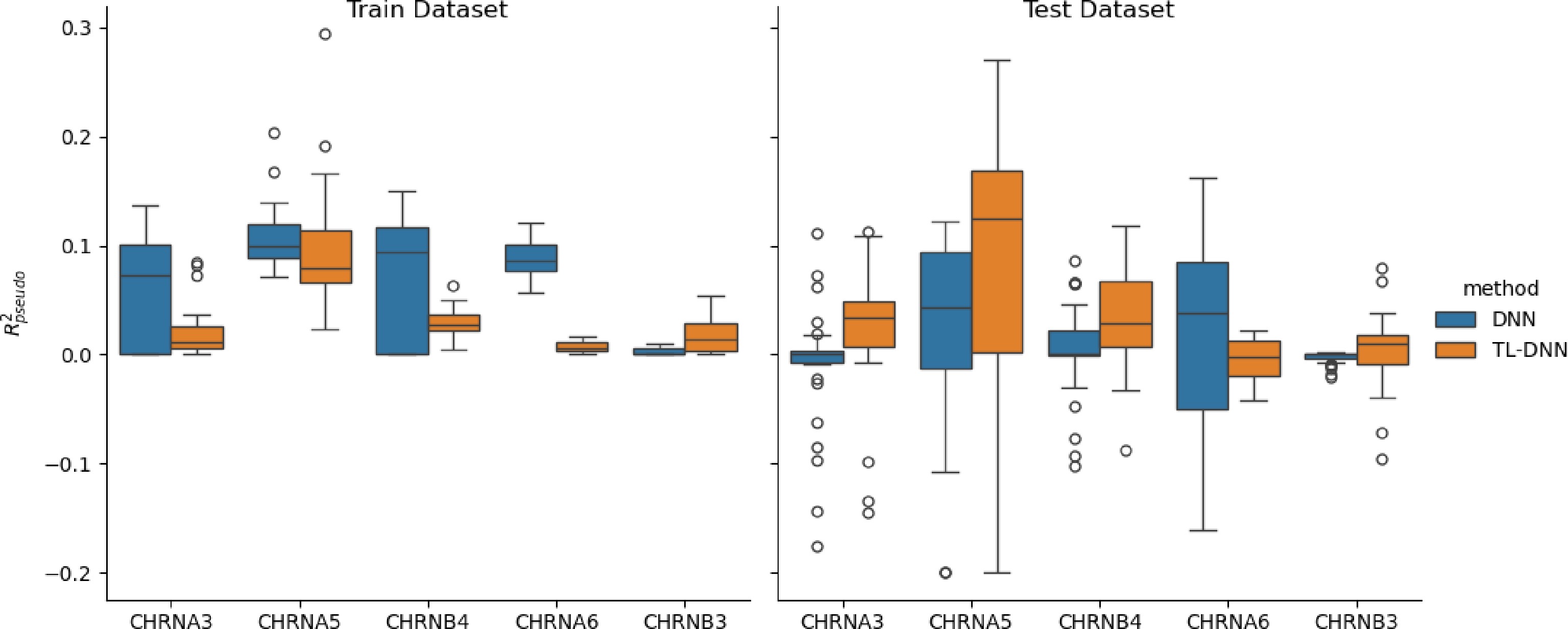

Similar to above, the prediction performance of the proposed TL-DNN and the direct application of DNN without transfer learning is shown in Fig. 4 for the white Irish population, and Fig. 5 for the black population.

Figure 4.

Prediction comparison regarding relative efficiency in the SAGE data set between the transfer learning (TL-DNN) from UK Biobank and the direct application of DNN without transfer learning.

Figure 5.

Prediction comparison regarding relative efficiency in the UKB black population between the transfer learning (TL-DNN) from the white British population and the direct application of DNN without transfer learning.

Both Figs 4 and 5 show that transfer learning achieves higher relative efficiency for CHRNA3, CHRNA5, and CHRNB4, while it shows similar or slightly worse performance for CHRNA6 and CHRNB3. These results may be related to the genetic heterogeneity of CHRNA6 and CHRNB3, while the heterogeneity is not significant in the other three genes, which is consistent with our previous finding[21].

For the association analysis, Table 4 summarizes the result of the PT-DNN in the UKB white British sample, indicating all five candidate genes are significantly associated with nicotine dependence.

Table 4. PT-DNN results from the association analysis of five candidate genes in the UKB white British sample.

Gene $ \Delta $ $ \hat\sigma $ p-value CHRNA3 −6.6e−4 9.38e−5 1.02e−12 CHRNA5 −6.20e−4 1.07e−4 3.83e−9 CHRNA6 −6.09e−5 2.39e−5 5.474e−3 CHRNB3 −1.00e−4 3.88e−5 4.63e−3 CHRNB4 −1.02e−3 1.27e−4 5.00e−16 However, when applying PT-DNN to the UKB white Irish and black samples, whose sample sizes are limited, it yielded less significant results. Nevertheless, the proposed PT-TL-DNN had improved power to test all the candidate genes by using the model parameters learned from the white British sample. Tables 5 and 6 present the testing results from PT-DNN and PT-TL-DNN based on the UKB white Irish and black, respectively. As seen in Table 5, PT-TL-DNN identified all five genes are significantly associated with nicotine dependence in the white Irish sample while PT-DNN failed to detect the association of three genes (CHRNA5, CHRNA6, and CHRNB4). Similarly, for the association test in the UKB black sample, PT-DNN only identified one gene (CHRNA3) but our proposed PT-TL-DNN successfully identified four genes, (CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNA6, and CHRNB4), associated with nicotine dependence.

Table 5. Comparison between the permutation-based test without transfer learning (PT-DNN) and with transfer learning (PT-TL-DNN) in the UKB white Irish sample.

Gene PT-DNN PT-TL-DNN $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value CHRNA3 −1.15e−3 6.48e−4 0.0378 −6.95e−4 3.67e−4 0.0291 CHRNA5 −8.40e−4 5.22e−4 0.0529 −1.81e−3 7.9e−4 0.0110 CHRNA6 −4.20e−4 5.00e−4 0.201 −1.07e−3 3.97e−4 3.58e−3 CHRNB3 −1.58e−3 7.14e−4 0.0132 −2.59e−3 9.68e−4 3.75e−3 CHRNB4 8.60e−4 6.09e−4 0.0789 −1.02e−3 4.68e−4 0.0145 Table 6. Comparison between the permutation-based test without transfer learning (PT-DNN) and with transfer learning (PT-TL-DNN) in the UKB black sample.

Gene PT-DNN PT-TL-DNN $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value $ \Delta $ $ \hat{\sigma} $ p-value CHRNA3 −3.40e−3 1.73e−3 0.0247 −2.9e−3 9.2e−4 9.1e−4 CHRNA5 −2.50e−4 4.94e−4 0.305 −5.00e−3 1.80e−3 2.69e−3 CHRNA6 −1.09e−5 2.34e−5 0.679 −3.60e−3 1.12e−3 5.90e−4 CHRNB3 1.88e−11 4.35e−11 0.667 −1.20e−3 1.28e−3 0.183 CHRNB4 −1.62e−3 1.07e−3 0.0651 −2.80e−3 1.53e−3 0.0336 -

Our capacity to detect novel genes in small-scale studies or minority populations (e.g., African Americans) is often limited by the small sample size. The vast amount of genetic data collected from biobank projects and the Caucasian population provides us with an additional resource for genetic research in small-scale studies or minority populations. In this paper, we have proposed a transfer learning procedure in deep neural networks for genetic risk prediction and genetic association analyses in small-scale studies or different populations. Through a cross-project study and a cross-ethnicity study, we demonstrate the advantages of transfer learning in terms of prediction accuracy and testing power.

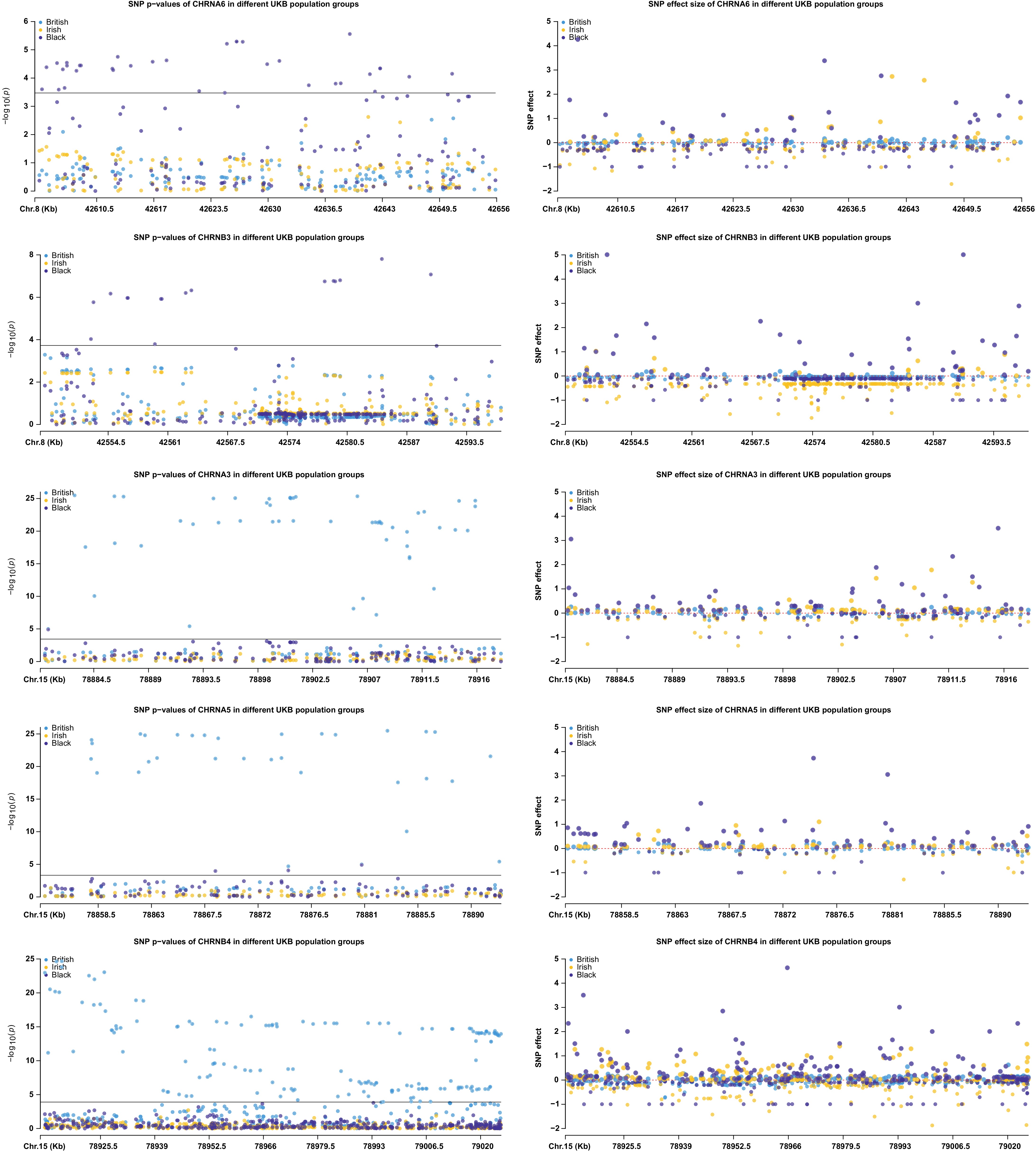

To further address the potential genetic difference among ethnic groups, we investigated the individual SNP p-values and effect sizes of all five genes in the white British, white Irish, and black populations, respectively, using software PLINK[22] and R package CMPlot[23]. From Fig. 6, we observe that the three populations show different patterns in genes CHRNA6 and CHRNB3. Moreover, in the black population, there are more significant SNPs in these two genes compared to the other three genes. These findings indicate that the DNN without transfer learning performs more effectively compared to the transfer learning in the black samples. On the other hand, for the three genes with more significant SNPs in the white British population, transfer learning attains better performance than DNN alone. These observations may partially explain the difference in model prediction performances in the cross-ethnicity case study.

Figure 6.

Illustration of genetic heterogeneity among the ethnic UKB population groups regarding individual SNP p-values and affect sizes of the five genes in populations white British, white Irish, and black.

Transfer learning is expected to become one of the key drivers of machine learning success. It does not require data from two studies drawn from the same feature space and the same distribution[5]. In most cases, as long as part of the model parameters are shared between two studies, transfer learning can help improve performance. In our studies, we transferred the model parameters among different studies and populations. In most scenarios, we found that transfer learning improved the models' accuracy and enhanced the test's power. Nevertheless, when a large discrepancy between the source data and the primary data exists, we expect poor performance of the transfer learning. Under such a circumstance, both datasets should be carefully examined, and additional procedures (e.g., testing the heterogeneity of data resources) need to be implemented in the transfer learning approach[14]. Regarding the theoretical basis of transfer learning, we refer to previous studies[24−26].

Besides the application of transfer learning in small-scale studies or minority populations, it can be used for other purposes, such as transfer learning from different species. While human studies play a significant role in genetic research, human research can be restricted due to study design and high cost. In contrast, animal research is more flexible and can adopt different designs. Given the experimental results generated from the well-controlled conditions, it would be valuable to further transfer these results to humans.

Limitations of the study include the limited sample sizes and the generality of the results in the two case studies. The proposed transfer learning techniques can be further explored and applied to a wider range of applications, such as different types of omics data, other complex traits, and diverse populations. Just like most applications of transfer learning, how to measure the transferability across domains and avoid negative transfer remains an important issue. Finally, despite the advances in the theoretical basis of transfer learning, theoretical studies for the proposed deep transfer learning can be further conducted in the future to better understand the properties of the proposed deep transfer learning.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lu Q, Geng P; analysis: Zhang S, Zhou Y; interpretation of results: Lu Q, Geng P, Dong K, Liu J; manuscript preparation: Geng P, Zhang S, Zhou Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, and Python codes are available on GitHub (https://github.com/DianaYuanZhou/PT-TL-DNN).

-

The authors wish to thank the two reviewers for their comments which greatly improved the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Shan Zhang, Yuan Zhou

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang S, Zhou Y, Dong K, Liu J, Geng P, et al. 2025. Predictive modeling and inference using deep transfer learning in genetic data analysis. Statistics Innovation 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/stati-0025-0003

Predictive modeling and inference using deep transfer learning in genetic data analysis

- Received: 01 April 2025

- Revised: 30 May 2025

- Accepted: 10 June 2025

- Published online: 28 July 2025

Abstract: Transfer learning has been widely applied in text and image classification, demonstrating its effectiveness in numerous applications. In this paper, we propose a transfer learning procedure for both prediction and association testing between genotypes and phenotypes in a smaller primary data set with an available larger source data set. Specifically, we training a deep neural network model in the source data, transfer a part of the trained weight parameters to the model in the primary data, and complete the training process in the primary data with the remaining free parameters. Furthermore, we develop a permutation-based association test using the trained transfer learning model to identify significant genes in the primary data set. We apply the proposed procedure to two case studies for the investigation of nicotine dependence. These two case studies show that transfer learning can not only improve prediction accuracy but also the power of detecting candidate genes compared to those results without transfer learning.

-

Key words:

- Transfer learning /

- Deep neural networks /

- Permutation test