-

As one of the most fundamental computational techniques in genomics and bioinformatics, de novo genome assembly aims to reconstruct complete chromosome sequences from raw sequencing reads. Since the Human Genome Project[1], de novo genome assembly techniques have continuously evolved alongside advancements in sequencing technologies. However, due to limitations in cost and read length, assembly methods based on Sanger sequencing reads and short reads from second-generation sequencing struggle to construct chromosome-level assemblies. While long-read assembly methods based on traditional third-generation sequencing can generate chromosome-level assemblies for most key eukaryotic genomes with the help of additional linkage information such as Hi-C and BioNano, they face challenges due to high sequencing error rates (around 15%). This makes it difficult to handle complex genomic regions like tandem repeats and dispersed repeats, as well as to construct haplotype-resolved assemblies for complex genomes, including those of heterozygous diploids and polyploids.

Significant breakthroughs occurred around 2019 with the emergence of two high-quality long-read sequencing technologies: PacBio HiFi and ONT UL. PacBio HiFi reads have a length of 15–25 kb and an error rate of less than 0.1%–1%, offering a balance of both read length and accuracy[2]. Although ONT UL reads have an error rate comparable to traditional long reads, their length can reach 100 kb or even 200 kb[3]. Currently, the assembly workflow combining PacBio HiFi data with Hi-C data has become the most widely used approach. This workflow, incorporating state-of-the-art assembly tools such as hifiasm[4], Verkko[5], Flye[6], and Canu[7], enables near-chromosome-level assembly for the vast majority of heterozygous diploid and homozygous diploid (haploid) genomes in a phased or non-phased way[8]. It also allows accurate assembly of most types of repetitive sequences in relatively simple eukaryotic genomes (e.g., rice genome), resulting in near-telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assemblies. With the inclusion of ONT UL data, the assembly workflow based on PacBio HiFi, ONT UL, and Hi-C is capable of producing T2T or near-T2T assemblies for moderately complex genomes, with the aid of manual curation.

With the advancements in sequencing and assembly technologies, a large number of complete genomes have been constructed in recent years. Among these, the most iconic is the human T2T reference genome, T2T-CHM13, which marks the official entry of genome assembly into the telomere-to-telomere era[9]. Subsequently, the haplotype-resolved Chinese human genomes T2T-CN1[10], and T2T-Yao[11] were successfully assembled, and many other important eukaryotic species, such as rice (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare)[12], maize (Zea mays L. inbred line Mo17)[13], capsicum (Capsicum annuum L.)[14], cotton (Gossypium raimondii)[15], apple (Malus domestica 'Fuji')[16], goat (Capra hircus 'Inner Mongolia Cashmere')[17], ape (Hominoidea)[18], and soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr. cv. Williams 82)[19] have had their T2T or near-T2T genomes constructed. Although a part of these new genomes may not strictly meet the T2T standards (100% complete and correct rather than just gap-free), it is undeniable that their quality is a significant improvement over previous reference genomes of these species. Moreover, in recent years, the pangenomes of numerous important eukaryotic species have been constructed, including human (Homo sapiens)[20], tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.)[21], pig (Sus scrofa)[22], goat (Capra hircus)[23], vitis (Vitis vinifera L.)[24], and others. These pangenomes often contain dozens or even hundreds of high-quality individual assemblies. Most of these are consensus assemblies from homozygous diploids, but some also include haplotype-resolved assemblies from heterozygous diploids and even polyploids.

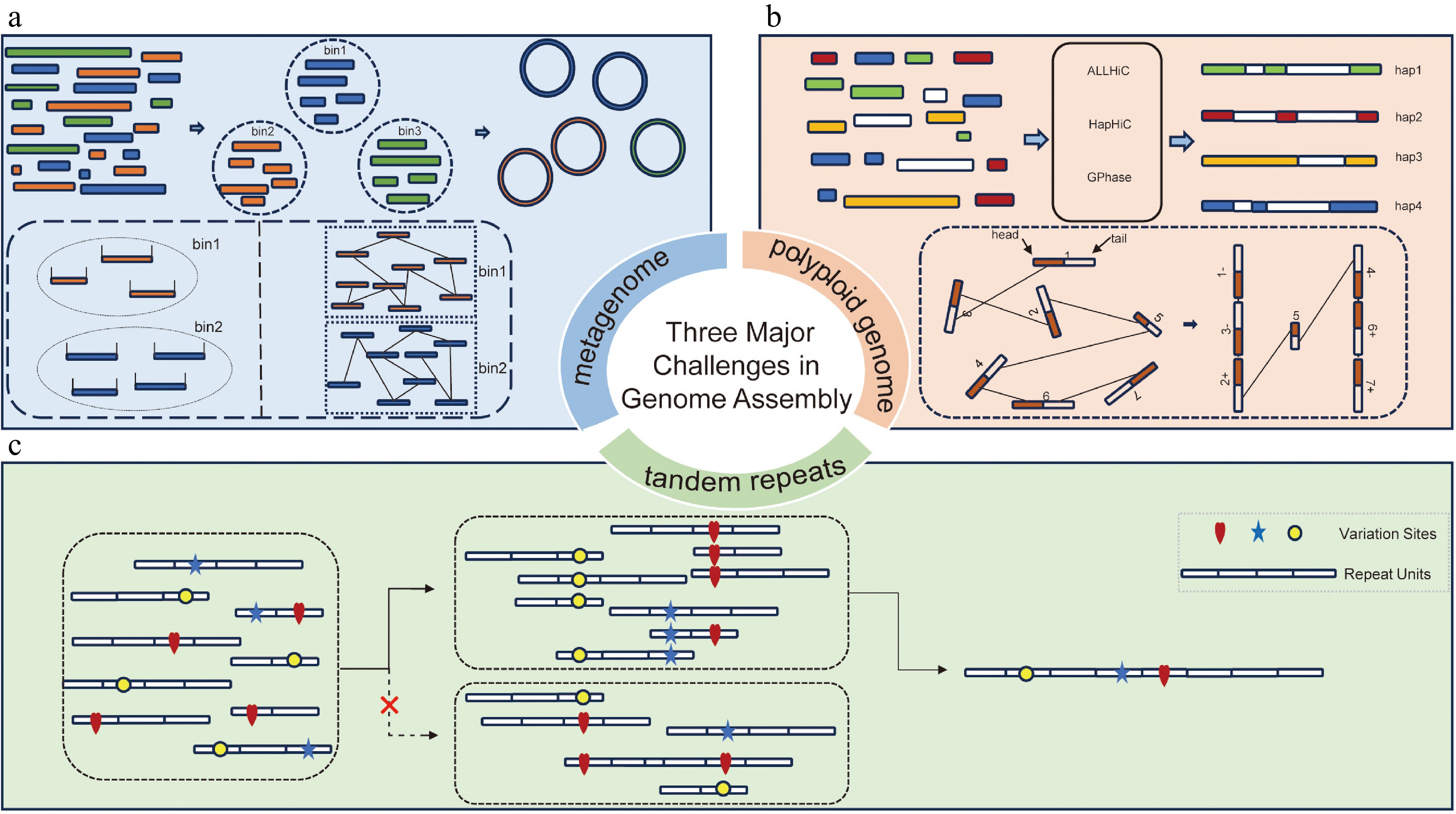

Nevertheless, several unresolved challenges remain in the field of genome assembly. These include the assembly of ultra-long tandem repeats (Fig. 1c), the haplotype-resolved assembly of polyploid genomes (Fig. 1b), and the complete assembly of metagenomes (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Schematics of assembling tandem repeats, polyploid genomes, and metagenomes. (a) Schematic of metagenomic binning: assembled contigs are grouped into different bins based on sequencing read coverage (left panel in dashed box) or Hi-C interaction signals (right panel in dashed box). These contigs are then connected to reconstruct genomes as completely as possible. (b) Schematic of haplotype-resolved scaffolding in polyploid genomes: in this step, preliminary contigs are assigned to different chromosomes and their respective haplotypes using Hi-C interaction signals, followed by ordering and orientation (as shown in the dashed box), ultimately achieving haplotype-resolved assembly. (c) Schematics of tandem repeat assembly: reads from tandemly repetitive regions were aligned in a pairwise manner. Sequence variations between repeat units, such as SNPs and small indels, were then used to evaluate the alignment correctness. Only correct alignments were retained and used to assemble the reads into continuous tandem repeat sequences.

-

The assembly of genomic repeat regions is a key focus of T2T assembly. Recent studies have revealed a strong association between repetitive genomic regions and various critical diseases[25]. For example, differences in centromere length between parental chromosomes have been identified as a major contributing factor to chromosomal triploidization in offspring, such as in Down Syndrome[26,27]. Additionally, approximately 40% of non-small cell lung cancers exhibit loss of heterozygosity (LOH) mutations in HLA genes, which are closely associated with immune evasion by tumor cells[28]. As mentioned, in recent years, significant progress has been made in addressing this challenge. Currently, not only can dispersed repetitive sequences, such as transposons, be easily resolved, but in most cases, long tandem repeats, such as centromeres and telomeres, can be assembled with high quality. However, there are still some special types of ultra-long tandem repeat sequences that remain difficult to assemble. One of the most typical examples is the assembly of the rDNA region, which often spans several megabases. The sequences of individual copies are highly similar, with even a single copy of length 45 kb containing only a few SNPs. This makes it extremely challenging to differentiate between the copies. Currently, almost all T2T assemblies (including the human T2T-CHM13) have rDNA sequences generated by duplicating a consensus sequence to create pseudo-sequences, rather than being assembled as true sequences[9]. From a methodological perspective, the core challenge in addressing this issue lies in ensuring that reads from repeat regions are not erroneously aligned to similar copies of other repeats. This is a limitation of the current mainstream alignment tools, such as mini-map2[29,30], and winnowmap2[31]. While alignment-filtering tools, such as RAfilter[32] and RAviz[33], are effective for removing false-positive alignments in normal tandem and dispersed repeats, they struggle to resolve highly similar copies, like those found in the rDNA regions.

Moreover, assembling repetitive sequences remains a significant challenge due to the high financial and time costs, severely limiting T2T-level assembly of large-scale pangenomes and ultra-large-size genomes. On one hand, existing assembly pipelines often require multiple data types, such as HiFi, ONT UL, and Hi-C, to achieve a more complete reconstruction of centromeres, telomeres, and other repetitive regions. For example, haplotype-resolved human genome assemblies generated using only HiFi and Hi-C data tend to lack most centromeric sequences. However, since ONT UL sequencing is relatively expensive, integrating all these data types can substantially increase overall costs. Recently, TRFill algorithm has been developed to fill large gaps in tandem repeat regions within chromosome-level assemblies constructed using only HiFi and Hi-C data, partially addressing the issue[34]. However, the algorithm is currently limited to tandem repeats and does not apply to other types of repetitive regions, highlighting the need for further methodological innovations in this area. On the other hand, existing assembly pipelines often involve highly time-consuming manual curation, with the most labor-intensive step being manual gap filling. This process can take weeks or even months, accounting for the majority of the assembly workflow and significantly reducing overall efficiency. Addressing this challenge requires methodological innovations in two key areas. A temporary solution is to develop software tools that assist with manual curation, making the process more accessible, lowering the technical barrier, and improving efficiency. Several tools, such as Bandage[35], Juicebox[36], Gap-Aid, and Gap-Graph, have been developed to aid different steps of genome assembly, including contig assembly, scaffolding, and gap filling, demonstrating promising results. However, the ultimate solution lies in further advancing automated assembly algorithms to eliminate the need for manual curation entirely.

As a case study, we analyze the assembly process of the human haploid T2T genome (T2T-CHM13), which is considered the highest-quality T2T assembly among eukaryotic genomes[20]. In this study, researchers combined approximately 30× coverage of PacBio HiFi sequencing with 120× coverage of ONT UL sequencing, and developed dedicated assembly and polishing methods. This approach enabled the successful assembly of highly repetitive centromeric satellite arrays and segmental duplications with high sequence homology. Specifically, a high-resolution string graph was constructed using PacBio HiFi reads to generate the initial assembly. Most components of this assembly originated from single chromosomes and exhibited near-linear structures, although gaps and mis-joins remained in some complex regions. Except for five rDNA regions, these complex gaps were resolved using ONT UL reads. Due to the limitations of string graphs in handling highly dynamic regions, the researchers ultimately constructed sparse de Bruijn graphs to assemble each rDNA array. The final T2T-CHM13 haploid assembly spans 3.05 Gb and achieves an estimated quality value (QV) of 73.9, representing a highly complete human haploid genome. However, it includes only 219 complete copies of the approximately 400 rDNA repeat units (accounting for 54.8% of the total), with the remaining sequences comprising partial or pseudo-sequences generated by duplicating consensus repeat units. This highlights that assembling rDNA sequences remains a major unresolved challenge in the field of genome assembly.

-

Another major challenge is the haplotype-resolved assembly of polyploid genomes. Polyploids can be classified into autopolyploids and allopolyploids, with the former posing greater assembly difficulties due to the higher sequence similarity between haplotypes. In polyploid genome assembly, the contig assembly step is similar to that of diploid genomes and can be performed using existing assemblers developed for diploids, such as hifiasm[4], Flye[6], and Verkko[5]. The primary difference lies in the scaffolding step, which requires specialized tools designed for polyploid genome assembly and phasing. In recent years, tools such as ALLHiC[37], HapHiC[38], and GPhase have been developed, enabling high-quality chromosome-level assembly for certain polyploid genomes. However, much like cancer genomes, polyploid genomes exhibit vast diversity, with significant differences in key characteristics such as sequence similarity. This results in highly variable assembly structures, making it difficult to establish a unified model or set of principles for algorithm design. Current algorithms are typically developed based on a limited number of known polyploid genome samples, which means they are often only effective for specific categories of polyploids. To address this challenge, a broad collection of diverse polyploid genome datasets is needed to systematically analyze and summarize their sequence characteristics. Based on these insights, more generalized assembly tools can be developed. A more promising approach is to integrate AI technologies into assembly graphs—such as leveraging graph neural networks (GNNs)[39]—to enable AI models to autonomously learn sequence patterns across different types of polyploid genomes. This could help avoid making strong assumptions within assembly algorithms. However, such techniques have only been minimally explored in haploid genome assembly and remain in their early stages, with performance still falling short of state-of-the-art assembly tools. For this technology to mature, two key advancements are required: breakthrough innovations in methodology and the acquisition of more genome datasets with reliable ground truth to expand training datasets.

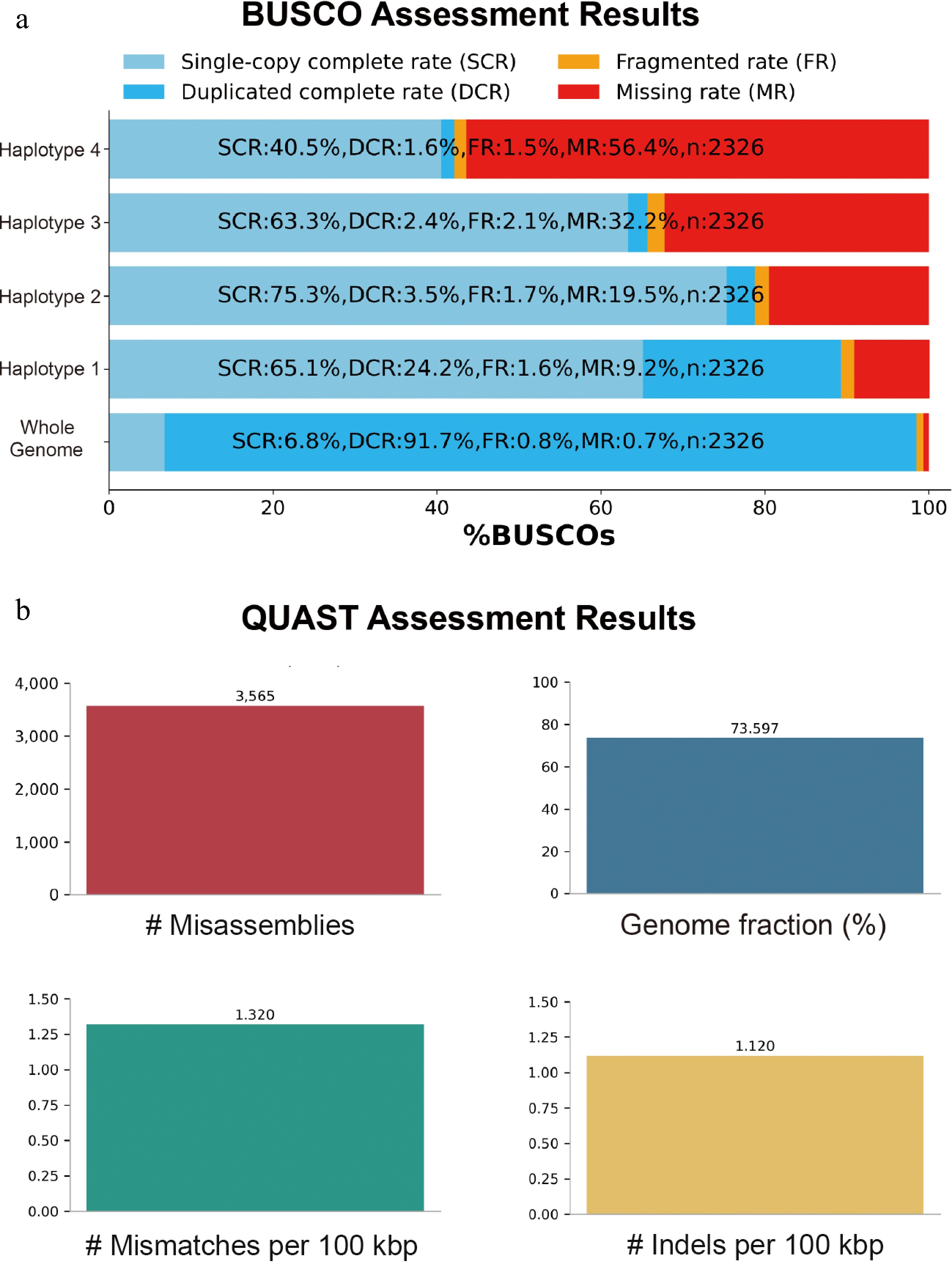

To further illustrate the progress and challenge in haplotype-resolved assembly of polyploid genomes, we reassembled a published genome of the autotetraploid potato cultivar C88 (Solanum tuberosum L. 'Cooperation-88')[40]. A preliminary assembly was first generated using Hifiasm with 96 Gb of PacBio HiFi sequencing data, yielding 26,952 contigs with a total length of 3.143 Gb and an N50 of 1.4 Mb. These contigs were then scaffolded using HapHiC, resulting in a phased assembly of 2.34 Gb, compared to the estimated 3.15 Gb genome size of potato. Assembly quality was assessed using BUSCO and QUAST. While the overall BUSCO completeness reached 98.5%, there were substantial differences among haplotypes (Hap1: 89.3%, Hap2: 78.8%, Hap3: 65.7%, Hap4: 42.0%). These results suggest that although scaffolding tools such as HapHiC can achieve haplotype-resolved assembly for polyploid genomes, the resulting assemblies still suffer from suboptimal quality and require considerable manual post-processing. First, the automated pipeline often introduces phasing errors (Fig. 2b), which demand extensive manual correction. Second, in regions with high allelic similarity (i.e., severely collapsed regions), the assembly quality and completeness deteriorate significantly (Fig. 2a). In summary, two major challenges persist in haplotype-resolved assembly of autopolyploid genomes: inaccurate haplotype phasing and reduced sequence completeness in highly similar allelic regions.

-

Metagenome assembly is another major challenge. Compared to polyploid genomes, metagenomes exhibit even greater complexity and diversity, making assembly significantly more difficult. Before 2019, only a few dozen complete microbial genomes had been successfully assembled from metagenomic samples[41]. The advent of HiFi sequencing has dramatically transformed this landscape. With HiFi data, a single sample can now yield dozens or even hundreds of complete or nearly complete microbial genomes using state-of-the-art assemblers such as metaFlye[42], hifiasm-meta, and metaMDBG[43−45]. As a result, the goal of metagenome assembly has shifted from merely recovering a useful subset of sequences to accurately assembling entire genomes (similar to single-genome assembly). Nevertheless, in assemblies generated from HiFi reads, most microbial genomes still exist in a fragmented form[43]. Assigning these contigs to their respective genomes (binning) remains a critical and challenging problem, although it is somewhat easier than binning contigs derived from short reads[46]. Traditional methods based on sequence-composition similarity and coverage similarity can only achieve coarse-grained binning[47−49], which is insufficient for high-resolution analysis. As a result, leveraging metagenomic Hi-C signals for binning has emerged as the most promising solution. As early as 2015, metagenomic Hi-C had already been applied to binning, but it did not gain widespread attention[50,51]. This was primarily due to two reasons: first, the complexity of metagenomic Hi-C sequencing made it challenging to generate high-quality data; second, it was difficult to obtain reliable Hi-C signals on the short contigs produced by short reads, limiting its applicability. In recent years, significant advancements in technology have greatly improved the proportion of valid read pairs (signals)[52], making it highly promising for use with the high-quality, long contigs generated from HiFi reads. Existing metagenomic binning tools based on Hi-C data, such as bin3C[53], HiCBin[54], and MetaTOR[55], can produce relatively accurate binning results. However, they still face challenges, such as mistakenly clustering sequences from multiple similar genomes together. Therefore, there is an urgent need for algorithmic innovations to address this issue and develop higher-resolution binning algorithms and tools.

As a case study, we examine the assembly of a high-depth sheep (Ovis aries) gut metagenomic dataset to evaluate the application of third-generation sequencing in metagenome assembly[43]. In this study, researchers combined high-accuracy PacBio HiFi sequencing with Hi-C technology. Compared to conventional short-read (second-generation) sequencing, this approach significantly improved the continuity and accuracy of the assembly. Leveraging the integration of HiFi and Hi-C data, the study successfully assembled 428 high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) (with > 90% completeness and < 10% contamination), including 44 complete circular bacterial genomes. Furthermore, Feng et al. developed hifiasm-meta, a metagenome assembler specifically optimized for HiFi data[44]. Without relying on any auxiliary data, hifiasm-meta successfully assembled 379 near-complete MAGs and 279 complete circular genomes from the same sheep (Ovis aries) gut metagenomic sample. However, despite these advances, the hifiasm-meta assembly still contained a large proportion of low-quality contigs (> 90%). In the final assembly graph, these contigs were entangled due to either local or global sequence similarity, preventing effective resolution. Current methods still struggle to fully separate and accurately assemble strains with high intra-species similarity or complex structural variations. This remains a major bottleneck in achieving truly high-quality metagenome assemblies.

-

To conclude, the new long-read sequencing technologies, such as HiFi and ONT UL, have propelled de novo genome assembly into the T2T era. In this new era, whether dealing with haploid, diploid, polyploid genomes, or metagenomes, the ultimate goal of assembly is to generate fully complete and accurate genome sequences. Moreover, achieving this goal must be as cost-effective, time-efficient, and labor-efficient as possible to enable large-scale population studies. However, current assembly technologies still fall short of this objective, particularly when handling ultra-long, highly similar tandem repeats, polyploid genomes, and metagenomes. Overcoming these challenges will require continuous methodological innovations in assembly algorithms, data structures, and computational strategies.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32470678); the Science and Technology Project of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, P.R. China; the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ZDRW202503); the Youth Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Y2025QC36); and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-CSIAF-202301).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: material collection: Lei J; draft manuscript preparation: Yang Y, Du W, Li Y, Pan W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All raw sequencing data for the potato cultivar C88 were downloaded from the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC, https://bigd.big.ac.cn) under project PRJCA007997. The reference genome for cultivar C88 (C88.v1) is available at SolOmics (http://solomics.agis.org.cn/potato/ftp/tetraploid).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yingxue Yang, Wenjie Du, Yanchun Li

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang Y, Du W, Li Y, Lei J, Pan W. 2025. Recent advances and challenges in de novo genome assembly. Genomics Communications 2: e014 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0015

Recent advances and challenges in de novo genome assembly

- Received: 24 March 2025

- Revised: 01 July 2025

- Accepted: 14 July 2025

- Published online: 29 July 2025

Abstract: De novo genome assembly has entered the telomere-to-telomere (T2T) era, driven by breakthroughs in high-quality long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio HiFi and ONT UL), and advanced assembly algorithms. This review comprehensively examines the current state and challenges of genome assembly across various genomic contexts. We highlight significant achievements, including the construction of T2T reference genomes for multiple eukaryotic species, and the development of pangenomes incorporating diverse individual assemblies. However, several critical challenges persist: (1) the assembly of ultra-long, highly similar tandem repeats, particularly in rDNA regions; (2) haplotype-resolved assembly of complex polyploid genomes, especially autopolyploids; and (3) complete metagenome assembly and high-resolution binning. These challenges are compounded by the high costs and time-intensive manual curation required for current assembly workflows. To address these limitations, we identify key areas for methodological innovation, including: improved alignment algorithms for repetitive sequences, AI-driven assembly graph analysis, and enhanced metagenomic Hi-C binning techniques. The integration of these advancements will be crucial for achieving cost-effective, efficient, and scalable assembly of complete and accurate genomes across diverse biological contexts, enabling large-scale population studies and advancing our understanding of genomic complexity.

-

Key words:

- Tandem repeats /

- Polyploid genomes /

- Metagenomes /

- De novo genome assembly