-

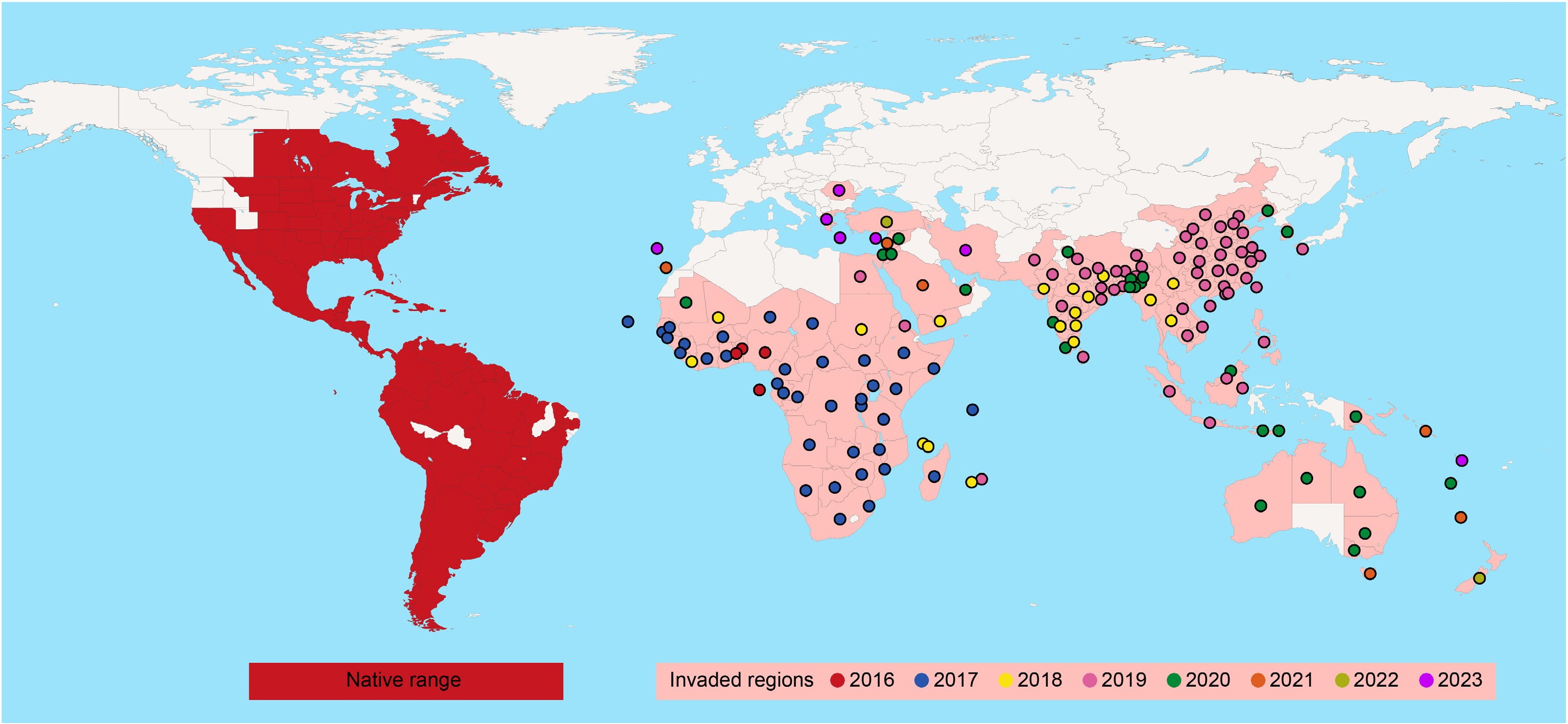

The fall armyworm is native to the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas. Due to its strong migratory ability, its range of damage in the Americas extends from Canada in the north to Argentina in the south, covering nearly the entire continent[1]. Since it was first detected in West Africa in 2016, the pest has rapidly spread across most of the African continent within two years, and subsequently expanded eastward into Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and other regions, even posing a potential threat of northward invasion into Europe (Fig. 1). Currently, the fall armyworm has successfully established adaptive populations in many invaded regions, completed the colonization process, and evolved into a major global agricultural pest.

Figure 1.

Schematic map of the global distribution and invasion spread of the fall armyworm. Colored dots indicate the first recorded year of fall armyworm detection in each region. The data were primarily sourced from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (last updated February 27, 2025) and supplemented with relevant published literature and reports.

Today, the fall armyworm has become an unavoidable focal point in agriculture. Wherever it spreads, it causes substantial economic losses to local crop production and poses serious disruptions to ecological balance. In Africa alone, annual losses attributed to fall armyworm damage are estimated at

${\$} $ In recent years, the availability of a chromosome-level genome for the fall armyworm, combined with large-scale population resequencing efforts, has enabled researchers to uncover the molecular genetic basis underlying its high invasiveness and destructive potential. These genomic resources and related studies have greatly enhanced our understanding of population differentiation and the evolutionary history of this pest. In the following sections, we summarize recent research from the perspectives of molecular biology and genomics, with a particular focus on some of the controversial findings related to invasive populations. We also offer our insights to provide a theoretical foundation and guide future research directions for the comprehensive prevention and control of the fall armyworm.

-

The fall armyworm is a typically polyphagous insect known to feed on over 300 plant species[10]. In its native range, fall armyworm larvae attack a wide variety of cultivated crops, including wheat, rice, sorghum, and corn, which are extensively grown throughout the Western Hemisphere. Damage has also been reported on cotton, soybean, millet, alfalfa, and even weeds during host-free periods. However, the most severe economic losses in the Americas are associated with infestations in corn and sorghum. Because of its broad host range that includes many economically important crops, particular attention has been given to the differentiation of its population strains. Based on host plant preferences, two main strains are typically recognized: the 'rice strain' and the 'corn strain'. The rice strain is commonly associated with bermudagrass and rice, while the corn strain is often distributed on corn[11]. In the Americas, these two strains are genetically distinct subpopulations, yet they commonly occur sympatrically across various host plants. Early studies suggested a degree of reproductive isolation between them, potentially due to differences in their mating time throughout the night[12]. However, subsequent laboratory experiments have observed successful hybridization between the two strains in both directions, although fertility ratios vary depending on the direction of the inter-strain cross[13].

The underlying fundamental factors and mechanisms driving the differentiation of these strains remain incompletely understood. Whether they should be classified as subspecies, host-associated populations, or geographically isolated variants requires further research and stronger evidence. It is also important to note that the terms 'rice strain' and 'corn strain' originated as practical descriptors based on field observations in the Americas and do not necessarily imply that these strains primarily target rice or corn, respectively. In particular, reports of the fall armyworm as a major pest of rice in its native range mostly trace back to literature from several decades ago, often likely referring to upland rice[14], which differs from the irrigated rice systems commonly used in other regions. More recent studies have associated the rice strain primarily with cover crops such as broadleaf signalgrass and pasture grass[15,16].

-

Since the two fall armyworm strains are morphologically indistinguishable, molecular markers have become an effective tool for differentiating them and have indeed confirmed their genetic divergence. Among these, the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) and Z-linked triosephosphate isomerase (Tpi) gene are among the earliest developed and most widely used molecular markers to date[17,18]. Both contain specific SNPs that reliably distinguish the two strains (Fig. 2). Notably, variation at a particular site in the COI marker can further divide the corn strain into two subgroups, corresponding to their geographic distribution in the Americas[19]. The Tpi marker is defined either by a combination of 10 SNPs located in exons 3 and 4, by a ~ 200 bp fragment within intron 4, or by a single highly diagnostic site (TpiE4-183)[18,20]. Since their development, these markers have been extensively used in strain identification and studies of fall armyworm population dynamics. However, it is important to note that in the species' native range, although these markers can distinguish the two genetic subpopulations, their genotypes do not always align with host plant preferences[21]. Based on the COI marker, approximately 20% of rice-strain genotypes have been found on corn, while around 5% of corn-strain genotypes have been detected on pasture or turf grasses, indicating that the marker-based strain identity does not perfectly predict host association[22].

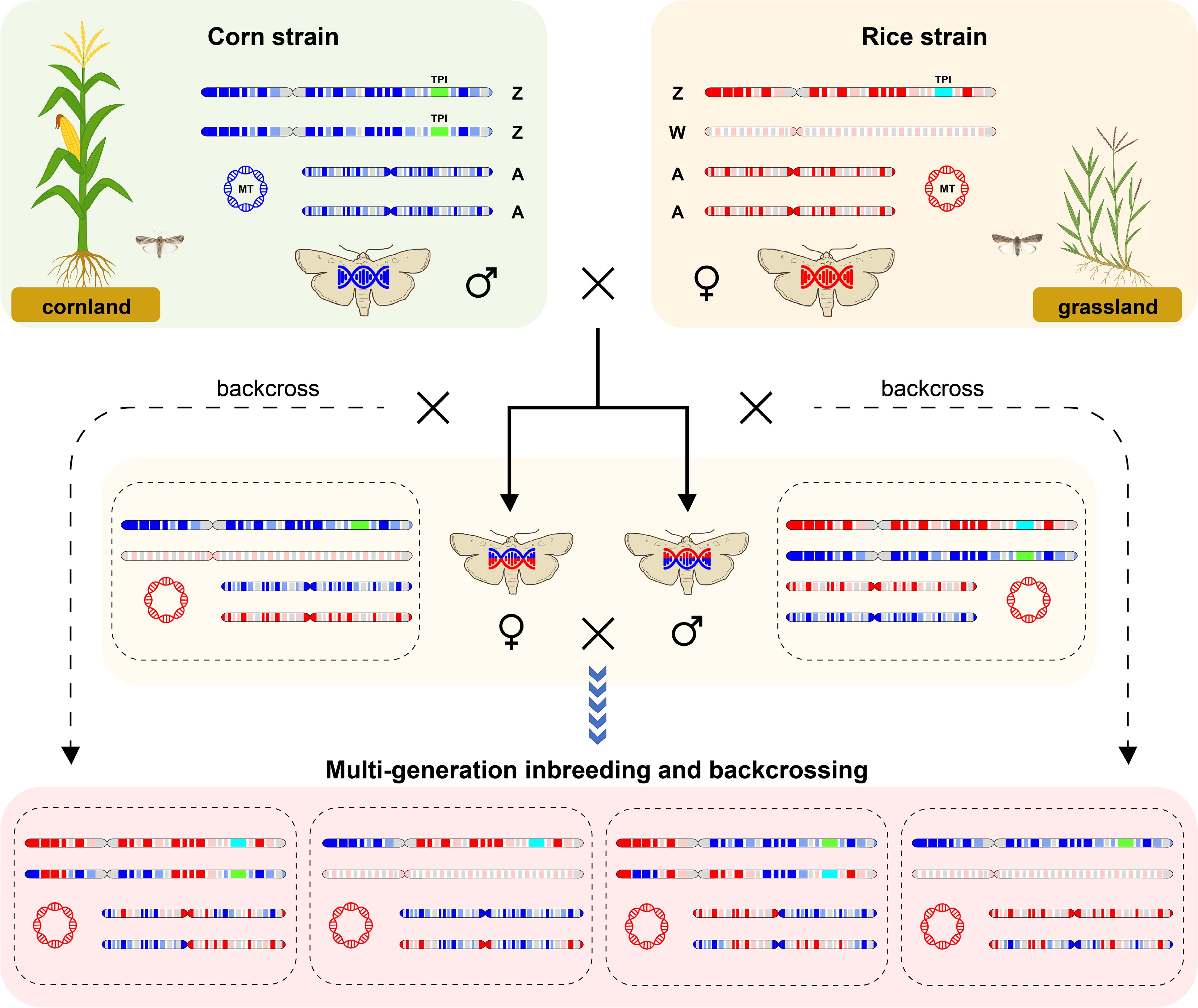

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the interstrain evolutionary patterns of the two fall armyworm strains. The corn-strain genetic background is represented in blue, and the rice-strain background is shown in red. MT and TPI denote the mitochondrial (COI) and nuclear (Tpi) molecular markers, respectively.

It should be noted that the two commonly used molecular markers each have inherent limitations. The COI marker is located in the mitochondrial genome and is maternally inherited, meaning that only the maternal genotype is expressed in the offspring. In contrast, the Tpi marker is located on the Z sex chromosome in the nuclear genome. As such, male individuals (ZZ) can express genotypes from both parents, while female individuals (ZW) only inherit and express the paternal Tpi genotype. Therefore, in cases of hybrid between strains, which has been reported in natural populations with approximately 16% of sampled individuals identified as potential interstrain hybrids[23], neither marker can fully and accurately represent the individual's complete genetic background (Fig. 2). Moreover, as previously mentioned, these two markers are only associated with phenotypic strain differentiation and are not the causal drivers of strain divergence. Although they have been widely used for strain identification and population dynamics studies in the species' native range, their accuracy declines under certain conditions, particularly in the presence of heterozygocity when hybrid strains. In such cases, these markers can no longer be regarded as reliable tools for strain identification. Relying solely on molecular markers without considering the underlying genetic complexity introduces limitations and may even lead to misleading conclusions.

-

During the early stages of the fall armyworm invasion, determining the strain composition of the invading population quickly became a research priority, as strain characteristics were closely linked to determining which host plants should be prioritized for monitoring and control. Across various invaded regions, including Africa and Asia, early studies using the COI marker revealed the presence of both rice- and corn-strain genotypes, with the rice-strain COI genotype generally appearing at a higher frequency, except in a few regions of western Africa, where the corn strain was more dominant[24]. However, results based on the Tpi marker consistently identified the invading populations as the corn strain[16,25]. Since Tpi is a nuclear genome marker and is generally considered more reliable than the maternally inherited mitochondrial COI for strain identification, the Tpi-based results, together with field observations of host plants (which aligned with typical corn-strain hosts), led to the commonly accepted conclusion that the invading fall armyworm populations belonged to the corn strain.

Several studies have reported the detection of rice-strain fall armyworm in invaded regions. However, some of these findings were based solely on the COI marker[26], which is widely regarded as unreliable for precise strain identification. Others relied on only a limited number of variable sites within the Tpi marker, many of which have since been shown to be unstable[27]. A few studies identified rice-strain or hybrid individuals in invasive populations using the most diagnostic Tpi site, TpiE4-183[28]. Notably, in these cases, the TpiE4-183 variation in invasive samples was consistently accompanied by several other unique polymorphisms, often referred to as the Zambia strain or AfrRa1 strain, that do not match the haplotype profile of the traditional American rice-strain Tpi sequence[27,29,30]. Taken together, these findings lack solid evidence to support the presence of true rice-strain genotypes in invaded areas. To date, no invasive samples have been found to fully match the typical American rice-strain Tpi genotype.

The conflicting results obtained from different molecular markers suggest that the invasive fall armyworm population likely possesses a heterozygous genetic background. As mentioned earlier, in cases involving interstrain hybridization, no single molecular marker can accurately determine an individual's strain identity (Fig. 2). Therefore, whole-genome analyses offer a more comprehensive and reliable approach to uncovering the genetic makeup of these populations. Since the fall armyworm invaded the Eastern Hemisphere, genomic research on the species has advanced rapidly. To date, several high-quality reference genome assemblies have been published[16,27,31]. Additionally, population resequencing data from both native and invaded regions have provided a solid foundation for investigating the genetic background of invasive populations at the whole-genome level.

Whole-genome analyses reveal clear differentiation between rice-strain and corn-strain populations in native-origin samples. The population genetic structure is strongly correlated with the Tpi gene and shows some association with mitochondrial genotypes, but not with geographic origin[15,32,33]. In contrast, samples from invaded regions, particularly Africa and Asia, display marked genetic homogeneity, reflecting rapid population expansion over a short period. Further analyses of population differentiation indicate that invasive samples are genetically closer to the American corn-strain population, with evidence of gene flow from the corn-strain into the invasive populations[32]. Consequently, most studies have classified the invasive population as either the corn strain or a hybrid population with corn-strain dominance[27,32,34].

However, it may be overly simplistic to categorize the invasive fall armyworm population as merely the corn strain or the heterozygous interstrain. The genetic makeup of the invasive population differs from that of native populations, exhibiting unusually high genomic heterozygosity and nucleotide diversity[32,35], characteristics not typical of traditional invasive species, which usually display reduced genetic diversity due to founder effects. This elevated diversity could be the result of complex hybridization backgrounds or potential introgression from uncharacterized lineages, possibly even from an independently evolved local population in Africa[32]. Although no direct evidence currently supports this hypothesis, the distinct genetic structure of invasive populations compared to native ones may also result from processes such as genetic drift, similar to those observed in laboratory rearing, or due to sampling bias.

-

Although the fall armyworm possesses strong migratory capabilities, it is predicted that the population that invaded West Africa in 2016 was introduced through human-mediated pathways rather than natural dispersal[36]. Early analyses based on the mitochondrial COI-B fragment indicated that the invasive corn-strain genotype was consistent with the Florida type[29], which is distributed along the eastern coast of the United States and to the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. This genotype differs from the Texas type, which is primarily found in South America. Subsequent mitochondrial genome haplotype network analyses reached a similar conclusion, revealing that invasive samples share ancestral haplotypes with those from North and Central America. Additional evidence comes from the frequency of specific mutations (G227A) in the pesticide resistance-associated Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) gene[32]. These analyses suggested a low likelihood that the invasive population originated from South America. Moreover, while field populations in South America have developed resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) crops[37], samples from invaded regions remain sensitive to Bt toxins[27], further reducing the probability of a South American origin. However, some studies based on a limited number of nuclear SNPs have proposed South America as a potential source[38]. Additionally, the above-mentioned COI-B based Florida-type origin only accounts for the corn strain and does not explain the origin of the rice-strain COI genotypes, indicating that the source of the invasive population remains a subject of debate.

The fall armyworm has undergone extensive genetic differentiation in the Americas, with nearly every individual representing a unique mitochondrial genome haplotype[32]. In contrast, only about 10 mitochondrial haplotypes have been detected among more than 200 samples from invaded regions, with nearly all field-collected individuals exhibiting highly similar genetic backgrounds. This pattern strongly suggests that the invasion was likely initiated by a single introduction involving a small founding population, followed by rapid population expansion and spread, although a few studies have proposed the possibility of multiple introductions[24,38,39]. To date, no samples from the native range are completely identical to those from the invaded areas, either at the mitochondrial or nuclear genome level. This discrepancy is likely due to insufficient sampling coverage. On one hand, expanded sampling in the native range, particularly in Central and South America, could reveal missing genetic diversity. For instance, the Zambia-strain Tpi haplotype, currently regarded as unique to the Eastern Hemisphere[32], may exist in the native range but remains undetected due to limited sampling efforts. On the other hand, broader sampling within the invaded range may also lead to the detection of additional divergent genotypes, potentially even including the America rice-strain Tpi genotype. Additionally, although there have been reports suggesting that fall armyworm populations may have existed in the Eastern Hemisphere prior to 2016[40], which may help to potentially explain the high genomic heterozygosity and nucleotide diversity observed in invasive populations, still, there is currently no solid evidence to support this hypothesis.

-

Stable colonization marks a critical phase following the initial invasion of alien species and is often accompanied by successful adaptation to the new environment. The fall armyworm has now firmly established itself in invaded regions, causing sustained damage. It reproduces year-round in tropical and subtropical areas and expands its range during warm seasons through migratory behavior, mirroring its dynamics in its native range[41]. However, under laboratory conditions, invasive fall armyworm populations collected from China exhibited superior life-history traits compared to native populations from Florida, including shorter larval development time, higher fecundity, increased larval and pupal survival rates, and greater mating success[42]. Given that the genetic origins and characteristics of invasive populations remain unclear, and may potentially include rice-strain genetic backgrounds, it is essential to remain vigilant regarding their broader biological impact and potential for adaptive evolution.

First, regarding host preference and feeding damage: in invaded regions, the fall armyworm has primarily been reported feeding on typical corn-strain host plants, such as corn and sorghum, as well as other crops including wheat, soybean, and peanut[43]. Although rice is widely cultivated across many of these invaded areas, particularly in Southeast Asia and China, there have been few reports of large-scale fall armyworm infestations in rice fields. Only occasional observations have documented its presence in rice seedling plots[25]. However, it is worth noting that under laboratory conditions, invasive fall armyworm populations can be domesticated into stable strains that show a feeding preference for rice[44]. Furthermore, the invasive populations could also exhibit good adaptability to alternative rice-strain hosts such as various weed species and can successfully complete their life cycle on them[45]. These findings suggest that the potential for fall armyworm to evolve increased damage to rice-strain hosts warrants continued attention and monitoring.

Second, the evolution of pesticide resistance in the fall armyworm is a critical concern. Bioassay results on invasive populations have shown relatively high levels of resistance to organophosphates and pyrethroids, while maintaining sensitivity to chlorantraniliprole, findings that are consistent with molecular detection of resistance gene mutations[27,46]. Overall, the invasive fall armyworm population remains sensitive to commonly used insecticides, suggesting that key resistance mutations present in native populations were not introduced during the invasion. Regarding Bt resistance, although field-evolved resistance to multiple Bt toxins, such as Cry1F and Cry1A, has been documented in the Americas (particularly in South America)[37], invasive populations remain largely susceptible to Bt crops. However, it is important to note that under toxin pressure in laboratory conditions, invasive fall armyworm populations can rapidly evolve high-level resistance to the Vip3Aa toxin, involving multiple resistance mechanisms[47,48]. This highlights the pest's strong adaptive potential. With the anticipated commercial cultivation of Bt-corn in invaded regions, there is a significant risk that resistant populations may evolve rapidly under the pressure of selection, necessitating the need for proactive resistance management strategies.

Finally, the population evolution of fall armyworm in invaded regions warrants close attention. Although invasive populations currently display relatively uniform genetic backgrounds, they may undergo adaptive evolution, or even population differentiation, under the selective pressures of new environments. Previous studies based on molecular markers revealed that early invading populations were predominantly of the rice strain as determined by COI markers[25,49]; however, the proportion of the corn strain has gradually increased over time. This shift suggests that mitochondrial genotypes may be associated with differing traits such as flight capacity or reproductive ability[50]. Additionally, Tpi marker analysis indicates that invasive populations can be further subdivided into two sub-genotypes, implying a complex genetic background and the potential for ongoing differentiation[30]. Given the diverse cropping systems, varying environmental conditions, and human-mediated control measures across invaded regions, it is likely that fall armyworm populations will continue to evolve adaptively in unpredictable ways.

-

The fall armyworm has become the predominant agricultural pest in many invaded regions, occupying a competitive ecological niche over other local species[43]. Although its outbreak intensity has declined under strict management and control measures, it remains a significant threat to agricultural production. Notably, the range of host plants affected by the fall armyworm may continue to expand, potentially shifting toward rice-strain-associated hosts. For invasive populations, it is suggested to weaken the traditional descriptive classification of 'rice strain' and 'corn strain', as their genetic backgrounds differ significantly from those of the native populations in the Americas. Moreover, key environmental factors, such as host plant species (e.g., forage grasses), cultivation practices (e.g., upland rice), and cropping systems (e.g., Bt crops), in the native range differ from those in the invaded regions. Thus, the fundamental drivers of strain differentiation, possibly involving pheromone compatibility, olfactory preferences, detoxification pathways, or gut microbiota, remain unclear and require further investigation through integrative approaches.

For invasive populations, strain identification using traditional molecular markers may no longer be accurate or appropriate. Nevertheless, markers such as COI and Tpi still serve as valuable tools for monitoring newly introduced genotypes, tracking distribution patterns, and assessing population dynamics due to their efficiency and low cost. To thoroughly investigate the genetic characteristics of invasive populations and uncover the mechanisms underlying their invasion and outbreaks, future studies should place greater emphasis on whole-genome approaches. A major current limitation is the insufficient sampling of field-collected specimens from the native range of the Americas, especially across different time periods, geographic regions, host plants, and phenotypic traits. With more comprehensive and representative sampling from the native regions, future research incorporating pangenomics, comparative genomics, and metagenomics will be essential for revealing the species' population diversity, genetic structure, and evolutionary trends. This, in turn, will provide a robust scientific basis for understanding invasion dynamics and developing effective strategies for integrated management and control.

The fall armyworm serves as an ideal model organism for studying biological invasions. As a recently emerged invasive species, it offers a valuable opportunity to investigate the full trajectory of invasion, from initial entry to outbreak and eventual colonization. Therefore, conducting long-term, large-scale field monitoring, combined with bioassays and multi-omics analyses, can systematically uncover the mechanisms of its post-invasion adaptive evolution, including phenotypic plasticity, gene introgression, selection signatures, resistance evolution, and habitat suitability. Such research will offer both a solid theoretical foundation and practical strategies for studying the invasion and adaptation processes of the fall armyworm and other invasive species.

This work was supported by the Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2022ZD04021) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. CAASZDRW202412).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiao Y, Zhang L; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang L, Liang X. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during this review.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang L, Liang X, Xiao Y. 2025. Genomic perspectives on the evolution of fall armyworm subpopulations. Genomics Communications 2: e015 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0013

Genomic perspectives on the evolution of fall armyworm subpopulations

- Received: 21 May 2025

- Revised: 14 June 2025

- Accepted: 27 June 2025

- Published online: 06 August 2025

Abstract: Since its invasion in the Eastern Hemisphere, the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) has rapidly become one of the world's most destructive invasive species. Its explosive spread and severe damage to crops have brought this originally regionally distributed pest into global focus and made it a hot topic in agricultural pest research. It has prompted a series of biological and ecological studies, including systematic research on host selection, population dynamics, insecticide resistance, and more, gradually revealing the biological foundations of the pest and enabling a more comprehensive understanding of its impact. However, to date, knowledge about the genetic properties of fall armyworm strains and the mechanisms behind its invasion and outbreaks remains incomplete and requires further investigation. This review systematically summarizes recent research progress on fall armyworm from the perspective of genomics and molecular biology, providing scientific insights and prospects for understanding strain differentiation and population evolution in this species.

-

Key words:

- Fall armyworm /

- Strain identification /

- Interstrain /

- Population differentiation