-

Fire safety remains a critical challenge in both residential and industrial settings, especially with the growing use of combustible polymeric materials in construction and transportation[1]. Some advanced systems, such as smoke alarms and sprinklers, have been installed to prevent fire incidents with a reduced number of deaths over recent decades. However, the escalating frequency of recent fire incidents, such as the iconic spiral spire of Denmark's oldest landmark, the Old Stock Exchange building, caught fire and collapsed on April 16, 2024, the Notre-Dame cathedral fire, and the London Grenfell Tower fire, has increased our awareness of fire prevention in ancient and modern buildings[2]. These disasters have also resulted in substantial casualties, property devastation, and the permanent obliteration of precious artifacts[3]. Notably, one common cause identified in fire incident investigations is the use of highly flammable polymers in buildings, which exacerbates the spread of fire and the release of toxic gases.

Over the past decades, considering their versatile and durable properties, polymeric materials have been widely used in various industrial sectors, ranging from automobiles to building and construction materials. However, those hydrocarbon-based materials are highly flammable and have a very large fire load, which poses potential hazards in our daily life and restricts their practical applications in some areas[4]. To mitigate the possible fire risks, approaches have been developed to prevent the ignition or reduce the heat release during the polymer burning process. As a result, these advanced polymeric materials can meet the requirements of a series of industrial standards and regulations. Particularly, adding efficient flame retardants to the polymer matrix is considered the most convenient method to interfere with different stages involved in the combustion process using physical and/or chemical strategies[5].

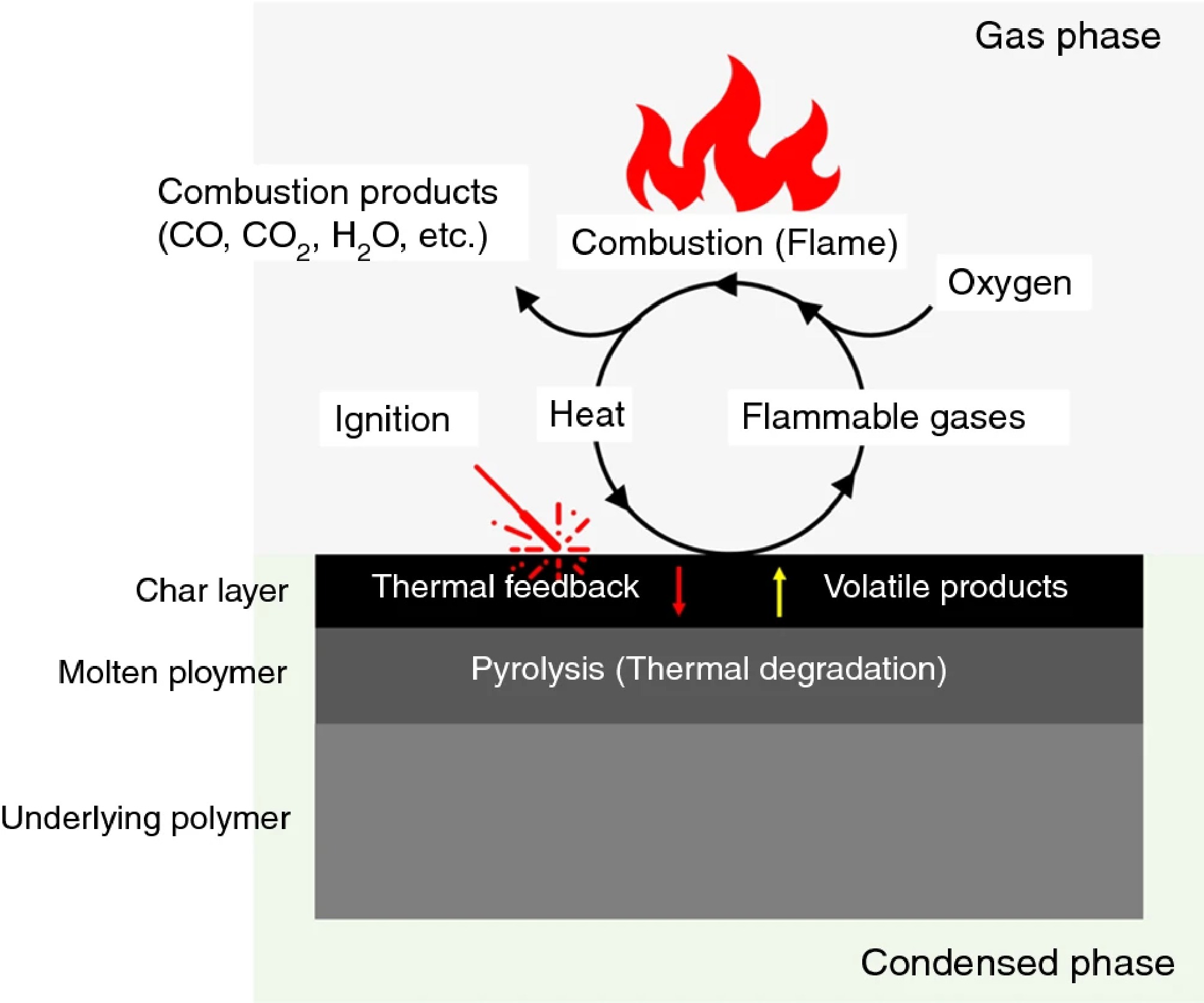

Figure 1 describes the multi-stage processes in both gaseous phase and condensed phase during the polymer combustion period, which includes various interrelated physical and chemical interactions[6]. Based on the fire triangle (heat, fuel, and oxygen), it can be generally divided into several steps. When polymers are exposed to heating conditions, it begins with thermal decomposition towards volatile fragments. Those flammable volatiles diffuse into the gas phase and mix with the oxygen to form a combustible gas mixture. When in contact with high-energy sources in the environment, they can initiate fire and release heat and toxins during polymer combustion. To prevent the ignition or minimize heat release, different flame retardants can be developed to interrupt and retard combustion in the condensed and gaseous phase by physical and/or chemical actions. In the condensed phase, the main objective of different flame retardants is to develop compact and thermally stable protective layers to suppress heat and mass transfer between the fire structure and the polymer matrix. During the formation of char structures, some inert vapors can be released to dilute those flammable volatiles, such as H2O, CO2, and NH3. As a result, the polymer degradation steps in the condensed phase can be slowed with a reduction in 'fuel flow' towards the flame structure[7]. Intumescent flame retardants (IFRs) are the typical cases by developing effective carbonaceous protective layers and increasing char yield in the condensed phase[8,9]. Similar barrier mechanisms that can also be used are borates or silicon-based compounds[10,11]. In addition to the char yield, the char quality, which is evaluated by graphitic carbon content, is also important to barrier thermal stability. The addition of carbon-rich components in the polymer matrix as 'carbonific' are beneficial to their performance under heating and combustion processes. In the gaseous phase, the main principle is to interrupt free radical reactions of flammable volatiles from polymer degradation, as described in Eqs (1) and (2)[12]. With the addition of halogen or phosphorus-containing flame retardants, chain reactions in the combustion zone can be interupted. Specifically, halogen-based free radicals (e.g., Cl· and Br·) can react with H· and OH· to inhibit flame reactions. Even though they have been widely used to good effect in recent decades, an increasing scrutiny is observed due to environmental concerns. With similar mechanisms in the gaseous phase, phosphorus-based flame retardants have been a prominent alternative to conventional halogenated compounds to terminate free radical reactions, as described in Eqs (1)–(6).

$\rm H\cdot +\; O_{2}\to OH \cdot +\; O \cdot $ (1) $ \rm O\cdot +\; H_2 \to OH\cdot +\; H \cdot $ (2) $ \rm PO \cdot + \; H\cdot \to HPO $ (3) $\rm PO \cdot + \; OH\cdot \to HPO_2 $ (4) $ \rm HPO + H\cdot \to HPO $ (5) $ \rm HPO_2 + H\cdot \to H_2 + PO_2 $ (6)

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the polymer combustion process[6].

Based on these suppression mechanisms, current commercialized flame retardants can be categorized into several types, including halogen-based, nitrogen-based, phosphorus-based, silica-based, mineral fillers, intumescent systems, and nanomaterials[13]. Most of these synthetic chemicals are prepared from fossil resources, which is not environmentally friendly, and doesn't reduce CO2 emissions as required by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[14]. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions while meeting the increased energy demand, the utilization of renewable resources is considered a feasible choice. In recent decades, biorefinery strategy has been widely discussed to transform biomass components to bio-based energy and chemicals in the same way as the petroleum companies for fossil-based resources[5]. The raw materials can be either from first-generation biomass products from food sources (such as sugar-rich and starch-rich components), or second-generation products from non-food sources (such as cellulose and lignin). Despite their promise, bio-based flame retardants often face challenges in terms of thermal stability, flame-retardant efficiency, and compatibility with polymer matrices, particularly when used in high-performance or engineering-grade materials. To maintain environmental sustainability and overall impact, the exploration of biomass-based flame retardants from renewable sources is attractive in both industrial and academic research.

Based on the flame-retardancy mechanisms mentioned above, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus-based components are popular considering their inherent structural properties. To be more specific, biomass is considered a large renewable carbon reservoir within its saccharide-based structures, which are produced via photosynthesis reactions. Under heating conditions, those hydrocarbon structures can be dehydrated and carbonized to develop char structures as protective layers between flame and polymer matrix during the combustion process. As a result, it can replace some conventional IFRs as the carbon source to reduce both heat transfer and flammable volatile diffusion[15,16]. Moreover, nitrogen-rich compounds, which can be obtained from protein, vegetable oil, and fish gelatin, can release inert gas to dilute the volatiles in the flame structures, thus lowering the heat and toxicity release[17]. Some phosphorus-rich components from different sources can be utilized to produce P-containing flame retardants, such as living plant and animal tissues. For example, DNA has shown competitive flame retardancy performance to enhance thermal stability and promote the char formation of polymeric materials: the phosphorus groups can generate phosphoric acid to catalyze the auto-crosslinking dehydration process in the polymer matrix[18]. Therefore, the development of novel flame retardants from renewable resources is both crucial and promising for mitigating fire risks by disrupting various reactions in both the condensed and gaseous phases.

Although the sustainable biomass-based components exhibit promising applications in fire safety, some concerns have been raised: if those materials are used individually as flame retardants, it requires a higher value to meet the comprehensive flammability assessment, which would deteriorate their original mechanical properties or increase the cost of the industrial products[19]. To develop efficient biomass-based flame retardants while maintaining the original properties in a cost-effective strategy, two methods are widely used and have been discussed in recent studies: (1) combination of biomass component with other flame retardants; and (2) chemical modification of biomass component with functional flame retardant groups[20]. The combination of raw biomass with commercialized flame retardants is considered as a facile, efficient, and scalable method to industrially manufacture various polymer composites. Those biomass materials can act as the synergistic agent to increase thermal stability and promote the formation of char structure barriers, thus improving their self-extinguishing behavior and reducing heat and toxicity release during combustion processes[15,21]. It should be noted that interfacial compatibility behavior is required to be seriously considered for the mechanical strength and ductility performance of the polymer matrix when combining the biomass components with different commercialized flame retardants. Therefore, state-of-the-art design for combination strategy is required to prepare high-performance polymer composites that combine flame retardancy and the necessary mechanical properties[22].

Chemical modification of biomass components is considered another promising method to improve thermal stability and flame retardancy, which can be achieved by grafting some functional groups over the available reactive sites. For the carbon-rich saccharide and aromatic products, the phenolic hydroxyl and aliphatic hydroxyl groups have been utilized as the reactive sites to tailor various chemical modifications[20]. Based on the Mannich reaction mechanisms, the urea group was modified over lignin as the charring agent to improve thermal stability and residue yield under combustion[23]. Phosphorylation reactions of biomass components can be developed through hydroxyl group functionalization with strategies, such as phosphoric acid or its salts, polyphosphorus compounds, and through the grafting of phosphorus-containing polymers[24]. For the phosphorus-rich components, it provides various interactions over the reactive sites and can be combined with different flame-retardant structures (such as nitrogen, silicon, and boron) or polymer chains (such as cotton fabric and polyurethane foams)[25]. The combination of phosphorus materials with other heteroatoms is efficient in developing synergistic multicomponent systems, particularly for phosphorus-nitrogen (P-N) compounds. The prominent P-N structures, including phosphoramidates and cyclotriphosphazenes, are considered as sustainable replacements for halogen-based flame retardants[26,27]. The advanced P-N structures exhibit a higher thermal stability and lower volatility under heating conditions, which makes them stay within the polymer matrix during the combustion period and improves the condensed-phase performance[28]. Those reactive sites also allow for the phosphorus molecules as part of the materials' structure, thus leading to 'inherent' flame retardancy[25]. For example, a layer-by-layer assembly strategy was developed to reduce the flammability of cotton fabric and polyurethane foams using chitosan and phytic acid (PA)[29,30]. It is noted that the chemical modification of biomass components is a combination of synthetic chemistry, flame retardancy mechanisms, and polymer processing. Sufficient studies are required to allow higher grafting yields and better compatibility with the polymer matrix, as well as to avoid degradation during the melting processes.

Costes et al. reviewed the applications of different biomass components to reduce the flammability of various polymeric materials, including cellulose, starch, chitosan, lignin, DNA, proteins, and PA[5]. Thakur et al. reviewed a series of lignin-reinforced polymer composites from synthetic molecules to biodegradable polymers[31]. Following this, Yang et al. provided a systematic review on the flame retardancy performance of neat lignin, combination of lignin with other flame retardants, and chemically modified lignin[20]. Hussin et al. discussed the recent strategies to modify cellulose-based flame retardants[32]. Biomass-based flame retardants, including starch, chitosan, DNA, lignin, PA, dopamine hydrochloride, cyclodextrin, and tannic acid, have been explored for their potential in sustainable fire protection[33].

This review focuses specifically on starch, chitosan, and PA due to their abundance, cost-effectiveness, and well-documented flame-retardant mechanisms. DNA and dopamine hydrochloride-based flame retardants, while highly effective, are limited by their high cost and restricted availability, making them less practical for large-scale applications. Lignin, cyclodextrin, and tannic acid, despite their promising flame-retardant properties, often suffer from challenges such as complex extraction processes, poor solubility, and limited compatibility with polymer matrices, which hinder their use in industry. Therefore, in this work, we mainly focus on starch, chitosan and PA, to summarize recent progress on synthesis, modifications, and synergistic mixture with other flame retardants for developing sustainable and environmentally benign polymer composites. The associated retardancy performances and mechanisms from those biomass components are also compared and investigated during polymer combustion processes.

-

To comprehensively assess the current state of research on biomass-based flame retardants, an extensive literature review was conducted, focusing on flame-retardant evaluation techniques, physical blending strategies, and chemical modification methods. This analysis provides insight into the advancements in utilizing starch, chitosan, and PA as sustainable flame-retardant materials while identifying key research gaps that require further exploration.

A detailed examination of flame-retardant testing methods and evaluation criteria was performed to establish a standardized framework for assessing material performance. Specific attention was given to studies investigating the chemical modification of starch, chitosan, and PA, as well as their incorporation into polymer matrices to enhance flame retardancy. Additionally, research on hybrid flame-retardant systems, integrating nanomaterials and synergistic flame-retardant components, was analyzed to highlight emerging strategies and technological advancements.

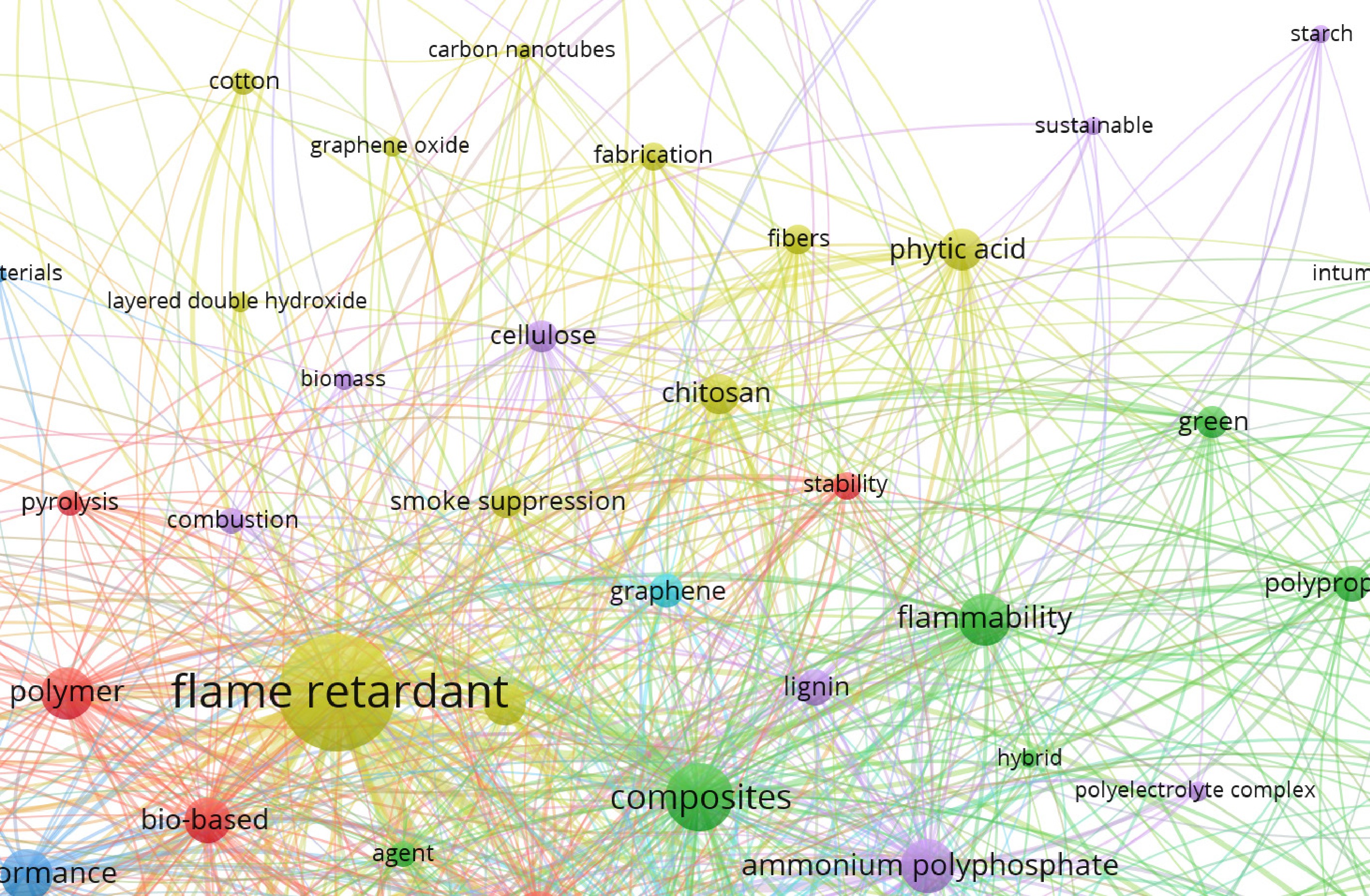

To visualize key research topics in biomass-based flame retardants, a co-occurrence network was constructed using VOSviewer. The analysis was based on the top 500 scientific publications retrieved from the Web of Science database using the keywords flame retardant, polymer, and bio. Through clustering analysis in VOSviewer (Fig. 2), the main research themes were identified and categorized according to their association strength, offering a comprehensive overview of the dominant focus areas in the field. Notably, frequently co-occurring terms such as starch, PA, and chitosan underscore the strong research interest in natural bio-based components. Two major approaches for enhancing flame-retardant properties and polymer compatibility were also evident: chemical modification, often associated with terms like ammonium polyphosphate (APP), and physical blending, reflected in terms such as composites.

Figure 2.

Clustering analysis in VOSviewer based on the top 500 scientific publications retrieved from the Web of Science using the keywords flame retardant, polymer, and bio.

Through this literature review, critical findings and prevailing research trends have been summarized, offering a structured overview of the field. The results highlight major advancements in biomass-based flame retardants while identifying challenges that need to be addressed, such as scalability, mechanical property retention, and eco-friendly modification processes. This analysis serves as a foundation for guiding future studies toward the development of high-performance, sustainable flame-retardant materials.

-

Thermal stability and flammability of flame-retardant polymer composites can be assessed by a series of characterizations. In this section, we mainly introduce the methods that can quantitatively describe the performance or determine the rating following international standards, including thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), limited oxygen index (LOI), Underwriters Laboratories Standard 94 (UL-94), microscale combustion calorimetry (MCC), and cone calorimetry. Some micro- or macro-scale characterizations can also be used to clarify flame retardancy mechanisms in both gaseous and condensed phases, such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy[7,34−39].

TGA

-

TGA is very efficient in simulating the thermal degradation of polymer matrices under either inert or air conditions. Corresponding TGA and differential thermogravimetry curves can reveal thermal decomposition behaviors in the presence of different flame retardants, including Tonset (temperature at which 5 wt.% mass loss occurs), Tmax (temperature at which maximum mass loss rate occurs), and residue yield in the condensed phase[40]. TGA can also be coupled with other evolved gas analysis to measure decomposed volatiles and pyrolysis products from polymer matrix, such as Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and mass spectrometry[41,42].

LOI

-

LOI is a fire-test-response apparatus to measure the minimum volumetric concentration of oxygen to support combustion by adjusting the flow rates of oxygen and nitrogen. Following the guidance of ASTM D2863 or ISO 4589, several testing procedures can be applied to determine the oxygen index, including surface ignition (procedure A), propagating ignition (procedure B), and comparison with a specified minimum value for oxygen index (procedure C).

UL-94 vertical burning test

-

UL-94 vertical burning test is a fire-test-response apparatus to determine the burning characteristics when exposed to a 20 mm (50 W) or 125 mm (500 W) flame that is applied to the base of specimens in a vertical position following various industrial standards, including ASTM D3801, ISO 1210, and IEC 60695-11-10. Given two 10-s flame applications, it records the after-flame time (t1) after the first flame application, the after-flame time (t2) and the afterglow time (t3) after the second flame application. Whether the flaming material drips from the specimen during combustion and whether these drips can ignite the cotton indicator are also recorded. Based on the after-flame, afterglow time, and cotton ignition behaviors, the samples can be classified as V-0, V-1, V-2, or no rating.

MCC

-

Similar to other thermal analysis techniques, samples can be thermally decomposed either in an anaerobic or aerobic condition with a constant heating rate[43]. MCC can provide two different procedures to determine the heat release behaviors of materials under a controllable heating and oxygen consumption calorimeter following the guidance of ASTM D7309. Corresponding heat release is calculated by the oxygen consumed by gaseous components from the matrix during thermal or thermoxidative decomposition. It only requires milligram samples and can be very efficient for initial material research and development.

Cone calorimeter

-

Cone calorimeter is a fire-test-response apparatus to simulate the forced combustion and bench-scale fire conditions and measure the corresponding reaction-to-fire properties after ignition (with or without an external ignitor) under a set external heat flux and ventilation environment. It can be used to simultaneously determine the ignition time, heat release, mass loss, effective heat of combustion, gas analysis, and visible smoke production in both the gaseous phase and condensed phase during the combustion period[6]. Following the guidance of various standards (such as ASTM E1354 and ISO 5660), it can comprehensively describe the polymer flammability behaviors for fire science and engineering.

-

Starch has become one of the most promising carbon-rich biomass materials in various practical applications due to its abundant production, competitive price, and complete biodegradability[44]. In most types of starches, it is composed of amylose (a linear molecule of glucopyranosyl units) and amylopectin (a highly branched polysaccharide with short chains), which are organized as starch granules. As a result, the structure of natural starch molecules has excessive free hydroxyl groups in the molecular chain. Assisted by hydrogen bonds, adjacent starch molecules can interact with each other to form a micro-crystalline structure. In the presence of some fillers, the compatibility between starch molecules may be interfered with, which is responsible for the different thermal stability and glass transition behaviors.

Basically, thermal degradation of starch molecules can be divided into three stages. It begins with the loss of absorbed and bound water during the dehydration step up to 150 °C. With temperature increase, the corresponding decomposition is related to chemical dehydration between hydroxyl groups to form ether segments. At the same time, the dehydration in the glucose rings results in the formation of C=C bonds and aromatic rings over time, such as interconnected benzene and furan structures. Lastly, the carbonization reactions go further for a larger conjugated aromatic structure at an elevated temperature[45]. Moreover, it is found that some functional groups that are grafted on the starch chains can improve the thermal stability: the higher the hydroxyl group substitution degrees over acetylation reaction, the higher the decomposition temperature of starch products[46]. The increased decomposition temperature is also very important in their potential applications since it can expand the polymer candidates that require a higher manufacturing temperature. To enhance flame retardancy, various strategies have been explored for starch-based systems, which include two main approaches: (1) physical combination with other flame retardants; and (2) chemical modification of starch itself. In combination strategies, starch is often used as a carbon source in intumescent flame retardant (IFR) systems, paired with ammonium polyphosphate (APP), melamine, microencapsulated IFRs, or inorganic fillers like kaolin. These combinations are applied in polymer matrices such as polyamide, polypropylene, polyurethane, and even wood substrates, showing significant improvements in LOI, UL-94 rating, and heat release suppression. In chemical modification strategies, starch is modified via phosphorylation (using phosphoric acid or phosphorus-containing salts), phosphorus-nitrogen (P–N) synergistic routes (e.g., with urea or dicyandiamide), and multi-acid treatments (e.g., combining PA and boric acid), aiming to introduce functional groups that promote char formation and gas-phase radical quenching. These chemically modified starch derivatives have been successfully applied in expandable polystyrene foams, cotton fabrics, and rigid polyurethane foams, demonstrating excellent condensed-phase and gas-phase flame retardant performance. These methods and their flame-retardant mechanisms will be discussed in detail in the following subsections.

Combination of starch with other flame retardants

-

In recent years, IFRs have been considered as one of the most promising categories of sustainable materials considering flammability suppression and environmental impact. Typically, commercialized IFRs include an acid source, a blowing agent, and a carbonization agent. When polymers are exposed to heat, the protective carbonaceous structures can be promoted from the dehydration of carbonization agents in the presence of the catalytic acid source and simultaneously expanded towards the fire structure by inert gas from the blowing agent to suppress heat and mass transfer between the condensed phase and gaseous phase. Considering the flame retardancy mechanisms and chemical structures, the carbon-rich starch components can be an efficient replacement for carbon sources in the flame-retarded polymer composites.

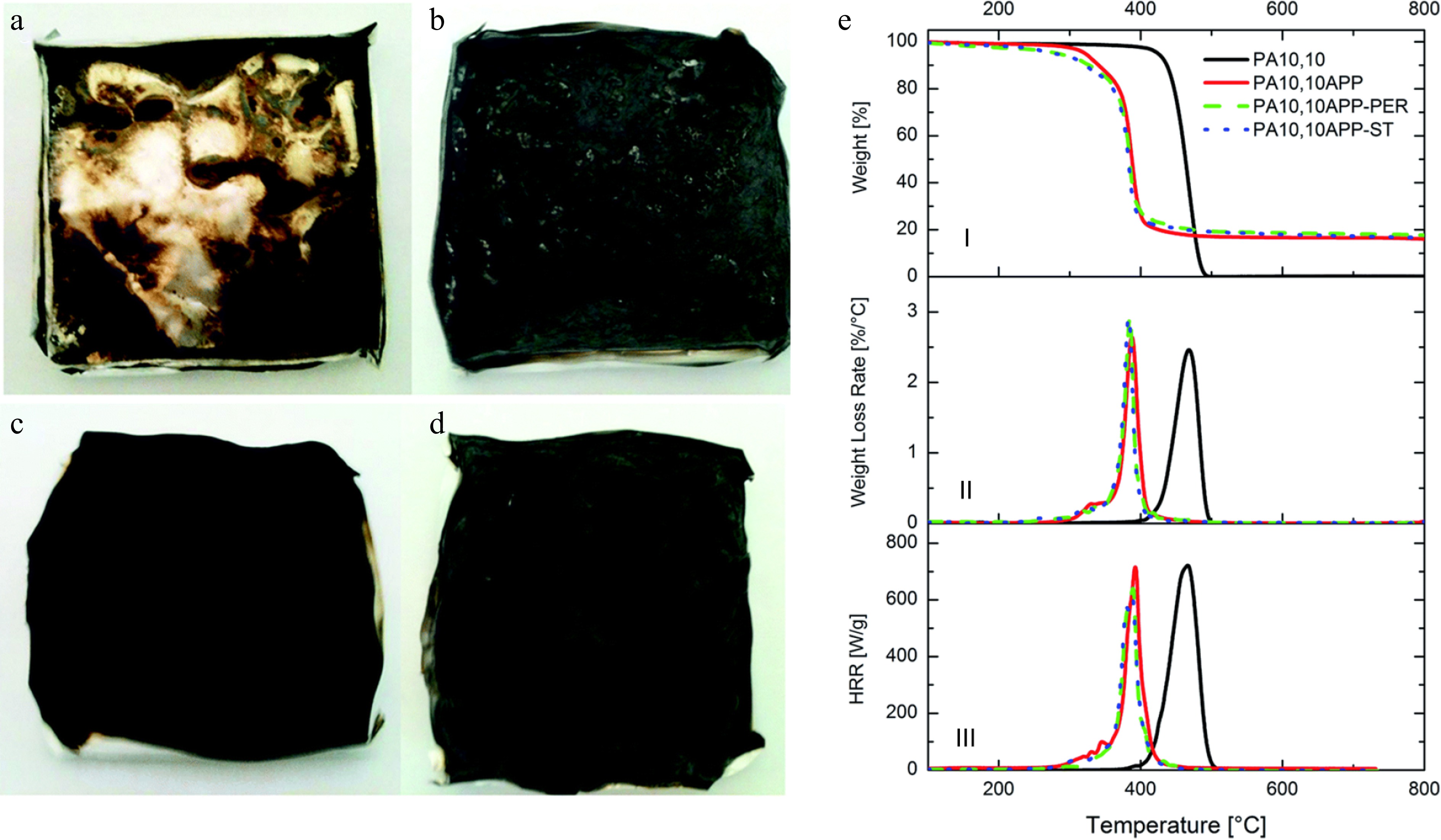

Battegazzore et al. demonstrated that corn starch can replace pentaerythritol as the carbon source and work together with APP to reduce the flammability of polyamide 10,10 (PA 10,10). It exhibits flexible manufacturing features: it can be prepared either by melt-blending with IFR formulations at 220 °C, or by coating the polymer matrix with UV-curable mixtures[47]. As illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 1, starch reinforced polyamide 10,10 composite (PA 10,10 APP-ST), and pentaerythritol (PER) reinforced polyamide 10,10 (PA 10,10 APP-PER) show a similar improvement on thermal stability and combustion behaviors of polyamide as assessed by TGA, MCC, and cone calorimeter tests. Compared with neat polyamide, PA 10,10 APP-ST exhibits excellent performance. The decomposition temperature (T5%) is increased from 332 to 425 °C, and a higher amount (16%) of char residue is collected at 800 °C. It is also observed that there was a 32% and 15% reduction in total heat release (THR), and peak heat release rate (pHRR), respectively. Furthermore, starch can jointly cooperate with APP to generate a more coherent and expanded swollen char structure to protect the polymer matrix, thus decreasing the pHRR from 1,101 kW/m2 (neat polyamide) to 712 kW/m2 measured using a cone calorimeter under a 35 kW/m2 heat flux. Similarly, the integration of microencapsulated APP and starch into polypropylene matrices further highlights the effectiveness of starch as a flame-retardant additive. With 20 wt.% microencapsulated APP, the sample polypropylene 40 wt.% starch can pass a UL-94 V-0 rating. The LOI value is as high as 28.0%. The pHRR and THR of the starch-containing polypropylene semibiocomposites decrease substantially compared with those of pure PP. The pHRR value decreases from 1,140.0 to 231.0 kW/m2, and the THR value decreases from 96.0 to 60.3 MJ/m2[48]. Starch, along with microencapsulated APP and melamine, was reported to develop a polyurethane-based composite with improved flame retardancy. While pure polyurethane is highly combustible, polyurethane composites containing 20% IFR and 10% starch achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating and a remarkably high LOI value of 40%[49]. Starch has also been combined with polyvinyl alcohol and kaolin to create flame-retardant, biodegradable coatings for wooden substrates. A 0.15 μm thick coating on 0.5 mm wooden strips significantly improved fire safety, increasing ignition time by four times, reducing the burning rate by 80%, and enhancing char formation[50]. From the above studies, it is evident that combining raw starch with other flame retardants significantly enhances flame retardancy. Leveraging the carbon-rich nature of starch and its compatibility with various systems, this approach provides a versatile solution for polymer composites. The synergistic interaction between starch and other components not only improves fire resistance but also broadens the application range, offering a sustainable and flexible strategy for developing advanced flame-retardant materials.

Figure 3.

Residue pictures after cone calorimetry tests for: (a) PA 10,10, (b) PA 10,10 APP, (c) PA 10,10 APP-PER, (d) PA 10,10 APP-ST, (e) TG, differential thermogravimetry and HRR curves of PA 10,10-based composites in nitrogen[47].

Table 1. TGA and MMC data of PA 10,10-based compounds.

Sample TGA in nitrogen MCC Cone calorimeter T5% (°C) Tmax (°C) Residue (%) THR (kJ/g) pHRR (W/g) TpkHRR (°C) THR (MJ/m2) pHRR (kW/m2) Residue (%) PA 10,10 425 468 0 32.6 720 467 30 ± 3 1101 ± 55 0 PA 10,10 APP 322 388 16 26.9 710 392 22 ± 2 735 ± 37 18 ± 1 PA 10,10 APP–PER 283 385 18 20.6 640 388 23 ± 2 833 ± 40 17 ± 1 PA 10,10 APP–ST 279 383 17 22.0 612 389 23 ± 2 712 ± 36 18 ± 1 Chemical modifications of starch as efficient flame retardants

-

Starch, as a naturally occurring polysaccharide, is widely recognized for its abundance of functional hydroxyl groups. These hydroxyl groups provide ample opportunities for chemical modifications, allowing starch to be tailored for various advanced applications. Among these, enhancing flame-retardant properties has emerged as a critical focus in starch chemical modification research, offering promising solutions for sustainable and environmentally friendly fire protection.

Currently, the primary methods for starch modification focus on phosphorus-modified systems and phosphorus-nitrogen (P-N) synergistic systems. These approaches have demonstrated outstanding flame-retardant performance across a variety of applications, such as expandable polystyrene foams, cotton fabrics, and rigid polyurethane foam (RPUF). Phosphoric acid and urea-modified starch have been reported for use in flame-retardant expandable polystyrene foams. The addition of 47 wt.% ammonium phosphate starch carbamates enhanced the LOI from 17.6% to 35.2%, achieved a V-0 rating in the UL-94 test, and reduced the pHRR from 666 to 316 kW/m2. Furthermore, the total smoke production (TSP) decreased sharply, from 70 to 17 m2[51]. In another study, cationic starch was modified with (2,3-epoxypropyl)trimethylammonium chloride and phosphorous acid for use as a flame retardant for cotton fabrics[52]. The treated fabrics passed the vertical flame test and achieved an LOI value of 43.9%. Cone calorimetry results revealed that the treated fabrics exhibited no concentrated heat release, indicating a condensed-phase flame-retardant mechanism. Phosphoric acid and urea were also used to modify starch to produce P-N modified starch, which was then applied in flame-retardant RPUF. With just 6 wt.% of P-N modified starch, the RPUF achieved a UL-94 V-0 rating, with a 41.1% reduction in pHRR and a 23.7% decrease in THR[53]. Additionally, the flame size and width were reduced, leading to quicker flame extinction. The modified starch also lowered the internal combustion temperature of the RPUF, effectively delaying both preheating and combustion times. The improvement in flame-retardant properties can be attributed to the gas-phase effects produced by phosphate esters. These effects include the release of reactive phosphorus-containing substances, such as PO or PO2 radicals, which interfere with the combustion process. These radicals restructure combustible reactive species (e.g., H·and OH·), thereby terminating the chain reaction of combustion[54].

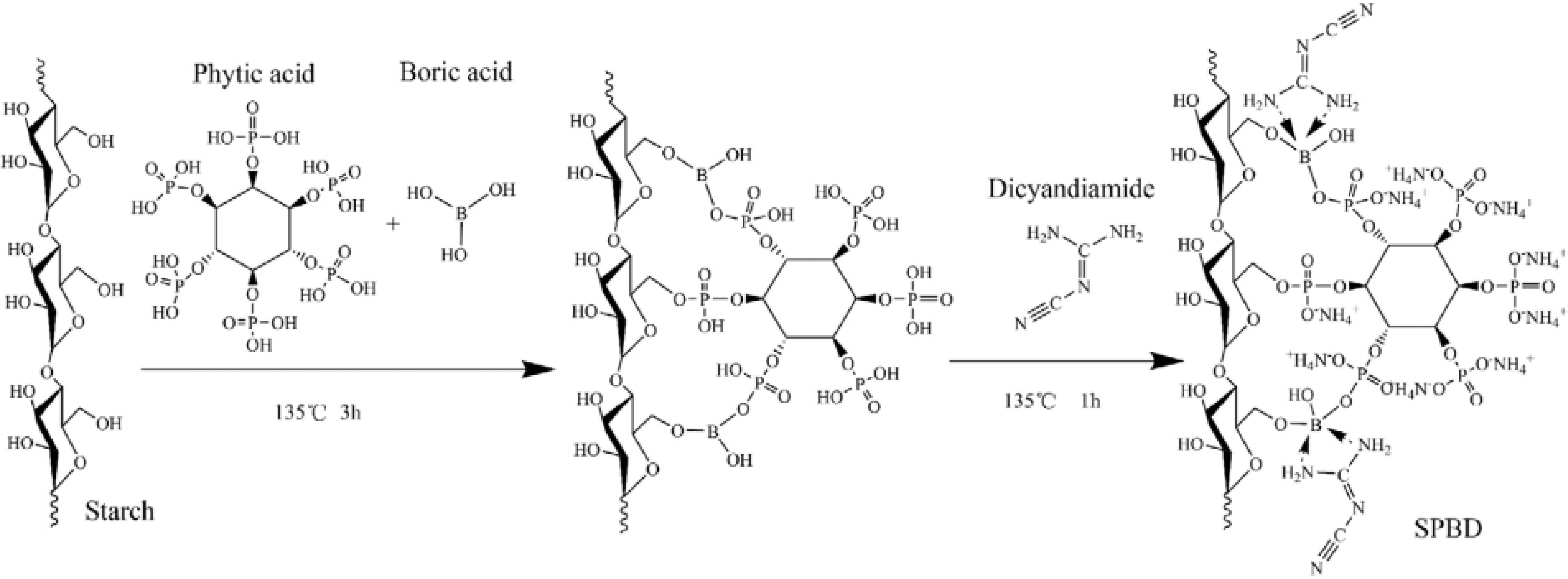

Another effective approach in starch modification involves the use of multiple acidic agents, such as combining boric acid and PA as acid sources (Fig. 4)[55]. A starch-based flame retardant was synthesized using starch as the carbon source, PA and boric acid as acid sources, and dicyandiamide as the gas source. The resulting flame retardants demonstrated excellent flame-retardant performance when applied to insulating paper. With a starch-based flame retardant concentration of 24%, the limiting residue in the insulating paper reached 34.72%, with a char length of 6.24 cm. Additionally, the LOI value of the FP-24 insulating paper increased significantly, from 19.4% to 44.0%, achieving the UL-94 V-0 rating. This remarkable flame-retardant effect can be attributed to boric acid and its derivatives, such as borates, which play a crucial role in flame retardancy by forming a glass-like, oxygen-impermeable coating that suppresses flame spread. Moreover, boron compounds exhibit significant synergistic effects within phosphorus–nitrogen systems, further enhancing their utility in flame-retardant applications.

Figure 4.

Synthetic route of starch-based flame retardants[55].

The chemical modification of starch presents significant potential for developing efficient and sustainable flame retardants. Current studies highlight the effectiveness of phosphorus-modified and phosphorus-nitrogen (P-N) synergistic systems, as well as the use of multiple acidic agents, in enhancing flame retardancy across various substrates. Future advancements could focus on multifunctional starch derivatives that combine flame retardancy with properties like water resistance and antimicrobial activity, eco-friendly modification processes aligned with sustainability goals, and nanoengineering approaches incorporating materials like graphene or nano-metal oxides. Addressing scalability, cost, and industrial compatibility will also be critical for widespread adoption. In summary, starch chemical modification offers a promising pathway toward sustainable and high-performance flame retardants, paving the way for safer and greener materials.

PA-based materials

-

PA is mainly extracted from plants, and it can also be found in animals and soil[56]. PA, also known as myoinositolhexaphosphoric, myo-inositol (1,2,3,4,5,6)hexakishosphoric acid, or inositol hexaphophoric acid, is formed during the ripening of seeds and grains and contains a 6-C ring with one H and one phosphate[57]. Each phosphate is attached via an ester linkage and bears two replaceable hydrogens. The two non-ester hydroxyl groups facilitate inorganic P-like (orthophosphate bond) properties, essential for the interaction of PA with various metal ions to form different soluble or insoluble compounds, known as 'phytate salts'. PA carries about 80%–85% of total phosphorus in plants, hence considered as a major storage of phosphorus. It has ~28 wt.% phosphorus and thus has great potential as a suitable alternative phosphorus source[58]. In the combustion process, PA is often used as the acid source in the IFRs system. Metaphosphoric acid and other substances are produced by thermal decomposition to promote the catalytic carbonization of carbon sources in the flame-retardant system. In addition, the PA produces many noncombustible gases, produces phosphorus-containing free radicals, and captures the free radical ions in the system in the gas phase to stop the combustion. At the same time, a large amount of phosphorus in its structure can be used as a charring agent to promote the formation of more stable carbon residue in the system. The more compact and continuous the carbon layer, the better the protection of the substrate. The carbon layer can be a physical barrier to reducing heat transfer and oxygen. PA will also produce phosphorus-containing compounds during the thermal decomposition process, which will form a physical barrier to protect the substrate.

PA can be used alone as a phosphorus-based flame retardant, or it can work synergistically with other flame retardants. However, the strong acidic nature of PA limits its direct use as a flame retardant. For example, its direct application has been found to negatively impact the mechanical properties of cotton fabrics, primarily due to its acidic nature, which can degrade cellulosic fibers[59]. To overcome this limitation, PA is treated in two ways before use in polymers: (1) forming salts with metal ions and combining with other flame retardants; and (2) chemical modification by compounding with fillers or forming organic derivatives. In metal-ion coordination strategies, PA forms stable phytate metal salts with elements such as Co, Ni, Zn, Al, and Cu, which enhance char formation, suppress smoke release, and improve thermal stability. These combinations have been successfully applied in polymer matrices, including polyurethane, PLA, epoxy resin, and textiles. In terms of chemical modification, PA can be converted into ammonium phytate derivatives by reacting with nitrogen-containing compounds (e.g., piperazine, furfurylamine, urea) or grafted onto nanofillers such as metal-organic framework (MOF), boron nitride (BN), and graphene to leverage synergistic effects. These modified systems significantly improve fire resistance while expanding PA's compatibility and application scope. The specific methodologies and fire-retardant mechanisms involved in each strategy will be detailed in the following subsections.

Combination of PA with metal ions

-

PA is a strong acid containing six negatively charged phosphate groups, giving it excellent chelating properties and enabling it to form complexes with metal ions. Metal ions can work alongside phosphorus-based flame retardants to facilitate the formation of a protective char layer, which acts as a barrier between the heat source and the substrate[60]. This process effectively inhibits the release of flammable gases during combustion, thereby enhancing flame-retardant performance. In general, transition metals such as Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, and Fe contribute to the formation of a carbonaceous physical barrier, thereby achieving flame retardancy. Meanwhile, main group elements like Mg, Al, and Ba typically form a protective layer that insulates the substrate, reducing heat and mass transfer while suppressing the emission of combustible gases[17]. Furthermore, these elements can promote solid-phase polymer crosslinking and carbon formation during combustion, leading to enhanced smoke suppression. Recently, researchers have developed various metal phytates to further improve the flame-retardant efficiency of polymeric materials. Table 2 lists some recent studies on phytate metals as flame retardants.

Table 2. List of recent studies on phytate metal salts as flame retardants.

Phytate

metal saltsPolymer matrix LOI pHRR THR TSP Ref. PA-Fe PLA / −24% − 25% / [19] PA-Co Polyurethane + 4.9% − 43.2% − 24.3% − 41.2% [61] PA-Ni PLA + 12.9% − 62.4% − 10.2% / [62] PA-Cu Poly(vinyl chloride) + 5.4% − 44.9% − 5.7% − 62.6% [63] PA-Al Polyamide 66 fabric + 8.2% − 43.9% − 38.2% / [64] PA-Zn Paper / − 43% − 49% / [65] PA-Zr Polyethylene + 5.4% − 46.4% − 14.9% / [66] PA-Mg EP / − 28.6% −10.6% / [67] PA-Ba EP + 11.6% − 69.1% − 71.5% − 77.4% [68] PA-Zn Polypropylene + 13.4% − 64% − 17.6% / [69] As flame retardants, phytate metals are mainly used in plastics, such as polyurethane, polylactic acid (PLA), and epoxy resin (EP). RPUF composites APP and cobalt phytate (PA-Co) as flame retardants were reported to exhibit improved fire resistance[61]. The pHRR of RPUF decreased from 260.7 to 181.2 kW/m2 with 50 phr APP and further to 148.2 kW/m2 with 40 phr APP and 10 phr PA-Co. THR of RPUF decreased from 23.0 to 19.3 MJ/m2 and further to 17.4 MJ/m2, accordingly. The fire performance index of RPUF/APP50 and RPUF/APP40/PA-Co10 increased to 0.0110 and 0.0135 m2·s/kW, respectively, indicating reduced fire hazards. Additionally, RPUF/APP40/PA-Co10 lowered CO yield by promoting the catalytic oxidation of CO into CO2 via Co ions. It also exhibited the lowest mass-loss rate (4.6 g/s·m2) and the highest char residue (40.4 wt.%), as Co ions effectively retained gaseous products in the condensed phase. The char residue at 700°C increased from 12.3 wt.% to 35.2 wt.% with APP/PA-Co, enhancing the composite's thermal stability. PLA composites incorporating nickel phytate (PA-Ni) and IFRs were also studied[62]. The results showed that with 4 wt.% PA-Ni and 11 wt.% IFR, the composite achieved a UL-94 V-0 rating and an LOI value of 31%. The pHRR decreased significantly from 368.3 to 138.6 kW/m2, while the residual char yield increased from nearly 0 to 12.6%. The enhanced flame retardancy can be attributed to PA-Ni promoting the formation of a compact, continuous char layer with improved graphitization. Additionally, phosphorus-containing compounds in the gas phase acted as radical scavengers, indicating that both gas-phase and condensed-phase flame retardant mechanisms contributed to fire resistance. PA complexed with copper ions (Cu2+) to form a flame-retardant material (Cu-Phyt) for flexible poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC)[63]. TGA showed that Cu-Phyt exhibited excellent charring behavior, contributing to enhanced flame retardancy. The LOI of PVC/Cu–Phyt increased from 24.9% to 30.3%, while the pHRR decreased significantly from 329.67 to 181.77 kW/m², and TSP was reduced by 62.63%. The mechanical properties of PVC/Cu–Phyt remained comparable to pure PVC, with minimal effect on tensile strength and impact toughness. The results indicated that Cu–Phyt is an effective flame retardant, offering significant improvements in fire resistance and smoke suppression, making it a promising candidate for practical applications in PVC.

In addition to plastics, phytate metal salts were used as flame-retardant coatings for textiles and papers. For example, PA was combined with Al3+ ions to form an in situ Al3+-PA complex on polyamide 66 fabric using a coordination-driven layer-by-layer deposition method[64]. The treated fabric achieved a maximum LOI of 27.8%, exhibited the highest char residue, and showed no melt-dripping behavior. Additionally, reductions in THR, pHRR, and heat release capacity confirmed the improved fire safety of the modified fabric. Similarly, a recyclable flame-retardant paper was developed using a zinc-coordinated multilayer coating composed of polyethylenimine/melamine and PA[65]. TGA demonstrated that the thermal stability of the treated paper was significantly improved, with the char residue at 700 °C increasing from 1.6% (untreated paper) to 31.6% (treated paper). Horizontal burning tests revealed that treated paper achieved self-extinguishing behavior, while MCC tests showed a 43% and 49% reduction in pHRR and THR, respectively, compared to untreated paper.

Chemical modification of PA as efficient flame retardants

-

The ability to replace hydrogen atoms on phosphate groups with various organic compounds provides a versatile platform for synthesizing PA-based flame retardants tailored for different applications. Such chemical modifications are typically designed to enhance compatibility with the polymer matrix, improving dispersion while minimizing adverse effects on mechanical properties. Chemical modification of PA primarily follows two approaches: forming PA derivatives or grafting PA with functional fillers. Forming PA derivatives involves chemically modifying PA by introducing new functional groups to enhance its flame-retardant properties while maintaining its core structure. Table 3 lists some recent studies on phytate ammonium as flame retardants. In contrast, grafting PA with functional fillers integrates PA with materials such as MOF, BN, and graphene, leveraging their synergistic effects to improve thermal stability, char formation, and overall flame retardancy[70−74]. While the former enhances PA's intrinsic properties through molecular modification, the latter relies on the additive effects of fillers to achieve improved performance.

PA derivatives are formed mostly by the combination of PA and amino groups, utilizing the synergistic effects between phosphorus and nitrogen elements to create phytate ammonium. The abundance of amino-containing compounds also provides an ideal platform for improving flame-retardant properties. Phytate ammonium has also been widely used in plastics. For example, PA reacts with furfurylamine in water to synthesize a novel bio-based flame retardant, PF[75]. The incorporation of 4 wt.% PF increases the LOI of PLA to 28.5% and enables it to achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating. Additionally, 4 wt.% PF reduces the pHRR from 362.2 to 332.7 kW/m2, demonstrating an 8% reduction. PF enhances flame retardancy by promoting the formation of melting droplets to dissipate heat, inhibiting the release of combustible gases, and improving char layer compactness. Furthermore, PF facilitates the capture of free radicals during combustion, leading to the formation of a graphitized carbon layer that protects the matrix. However, the TSP of PLA/PF composites is higher than that of pure PLA, indicating that the introduction of PF results in incomplete combustion, leading to increased smoke release. A bio-based nitrogen-phosphorus-containing flame retardant, PIPT, was synthesized by PA and piperazine[76]. The incorporation of 15 wt.% PIPT increases the LOI of EP to 35.5% and enables it to achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating. Additionally, 15 wt.% PIPT reduces the PHRR and THR of EP by 51.4% and 35.9%, respectively, demonstrating significant improvements in fire safety. PIPT enhances flame retardancy by promoting the formation of a compact and stable char layer, which acts as a barrier to heat and gas transfer. However, as the PIPT content increases, the mechanical properties of EP/PIPT composites slightly decline compared to pure EP. Phytate ammonium is also widely used in fabrics, such as cotton and wool, to improve their flame-retardant properties. For example, a flame-retardant material (APA) was synthesized using phosphoric acid and urea for cotton fabric treatment[77]. The cotton fabric treated with a 20% APA solution achieved an LOI of 43.2%, representing a 25.4% increase compared to the untreated fabric. The pHRR and THR of the treated fabric decreased by 94.5% and 58.0%, respectively. Additionally, the char residue significantly increased from 1.31% to 36.24%. The APA-treated cotton fabric contains abundant phosphate groups, which promote carbonization and enhance its condensed-phase flame retardant effect. A water-soluble polyelectrolyte complex (PEC) system based on PA and polyethyleneimine was developed to enhance the flame retardancy of wool fabrics[78]. The treated wool fabric exhibited a 13.2% increase in the LOI and reductions of 39.7% and 44.4% in the pHRR and THR, respectively. PA and polyethyleneimine combined to form an insoluble coating on the wool fiber surface and underwent both ionic and covalent cross-linking with the fibers, resulting in excellent flame retardant washing durability.

Table 3. Lists of recent studies on phytate ammonium as flame retardants.

Phytate ammonium Polymer matrix LOI pHRR THR TSP Ref. PLA-Furfurylamine PLA + 28.5% − 8% − 4% + 11.3 % [75] PA-Hexakis (4-Aminophenoxy) Cyclotriphosphazene PLA + 24.2% − 15.3% − 21.5% − 31% [79] PA-Trometamol PLA + 5.9% − 10.7% − 9.4% / [80] PA- Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl aminomethane PLA 8.5% − 30.2% − 29% + 80 % [81] PA-Piperazine EP + 12% − 51.4% −35.9% / [81] PA-Phenylphosphonate-based compound EP / − 64% − 16% − 21% [82] PA-Urea Cotton + 25.4% − 94.5% − 58.0% / [77] PA-(3-piperazinylpropyl) methyldimethoxysilane Cotton + 11.0% −55.6% −58.1% / [83] PA-polyethyleneimine Wool +13.2% − 39.7% − 44.4% / [78] The modification approach of integrating PA with fillers is also an effective method for enhancing fire resistance. A MOF, UiO-66-NH2, was functionalized with PA through a complexing reaction between P−O bonds and the zirconium metal sites of the MOF, forming a novel flame retardant (PA/UiO-66-NH2) for EP[84]. The incorporation of 5 wt.% PA/UiO-66-NH2 significantly improved flame retardancy, reducing pHRR by 41% and TSP by 42%. During combustion, the strong interaction between EP and PA/UiO-66-NH2 facilitated cross-linking, leading to the formation of a reinforced char layer that acted as an efficient physical barrier, limiting heat and gas transfer. Furthermore, the release of toxic gases was significantly suppressed, demonstrating the potential of phosphorus-functionalized MOFs as high-efficiency flame retardants. A BN nanosheet-based nanofiller (f-BNNSs) was functionalized with PA using a silane coupling agent, forming a sustainable multifunctional additive for poly(L-lactic acid). The incorporation of 20 wt.% f-BNNSs significantly enhanced flame retardancy, increasing the LOI value from 18.5% to 27.5% while reducing HRR by 50% and THR by 40.6%. During combustion, the strong interfacial interactions between f-BNNSs and Poly(L-lactic acid) promoted char formation, creating a robust protective barrier that effectively limited heat and gas transfer[72]. A graphene-based flame retardant (PMrG) was synthesized by self-assembling melamine and PA onto a reduced graphene oxide framework, forming a novel additive for PLA. The incorporation of 10 wt.% PMrG significantly enhanced flame retardancy, reducing pHRR by 35.3% and THR by 21.7%, while increasing the LOI value from 19% to 25% and prolonging the time to ignition from 46 s to 59 s. During combustion, the synergistic effect of graphene oxide, melamine, and PA promoted the formation of a compact char layer, acting as an efficient barrier to suppress heat and smoke release[85].

Chemical modification of PA enhances its flame-retardant efficiency by either forming PA derivatives or integrating PA with functional fillers. PA derivatives, primarily synthesized through reactions with amino-containing compounds, leverage the synergistic effects of phosphorus and nitrogen to improve flame retardancy. These derivatives, such as phytate ammonium salts, have been successfully applied in polymers like PLA, EP, and textiles, significantly enhancing their fire resistance. However, some formulations may lead to increased smoke release or minor mechanical property reductions. Alternatively, incorporating PA with fillers such as MOFs, BN, and graphene utilizes their synergistic effects to further enhance thermal stability, char formation, and overall flame retardancy. These composites form stable protective layers during combustion, reducing heat and gas transfer while suppressing toxic emissions. Both modification strategies demonstrate the versatility of PA-based flame retardants, offering effective solutions for improving fire safety across various materials.

Chitosan-based materials

-

Chitosan, a natural polysaccharide with inherent charring ability, has emerged as a promising component in flame-retardant systems. However, its direct application is often limited by poor solubility, thermal stability, and compatibility with polymer matrices. To overcome these challenges, recent studies have explored two primary strategies: combining chitosan with other flame retardants and chemically modifying its structure to enhance flame-retardant performance. The first approach leverages synergistic effects between chitosan and phosphorus-, metal-, or nanomaterial-based flame retardants, significantly improving thermal stability, char formation, and fire resistance. Layer-by-layer (LBL) assembly further enhances these properties, enabling the fabrication of multifunctional coatings with tunable thickness and composition. The second approach focuses on chemical modifications that introduce phosphorus, nitrogen, or silicon functional groups, enhancing chitosan's flame-retardant efficiency and mechanical properties. These advancements highlight chitosan's versatility in developing high-performance, sustainable flame-retardant materials for various polymer applications. In combination strategies, chitosan is blended with phosphorus-based salts, transition metals (e.g., Co2+, Fe3O4), or nanomaterials (e.g., HNTs, MXene, nano-silver), as well as assembled using LBL techniques with partners like APP, PA, or vitamin B2 phosphate to enhance char formation, thermal stability, and toxic gas suppression in substrates including PLA, PU, EP, PET, and textiles. In chemical modification strategies, chitosan is functionalized through phosphorylation, crosslinking, or shell-coating (e.g., CTSPA, MCMPP, RP@CH/LS), introducing phosphorus, nitrogen, or silicon moieties to enhance solubility, thermal resistance, and compatibility with the matrix. These modified systems have been shown to significantly boost LOI values and reduce pHRR, THR, and smoke production. The following subsections provide a detailed discussion on each methodology, its mechanism, and its application context.

Combination of chitosan with other flame retardants

-

Chitosan has been reported to enhance the flame resistance of polymer materials such as PLA, polyurethane, EP, and cotton fabric. However, chitosan is rarely used alone and is typically combined with other flame retardants through various strategies, such as blending and LBL self-assembly with other flame retardants[33,86]. For blending with other flame retardants, a phosphorus-containing chitosan-cobalt complex (CS-P-Co) was synthesized and incorporated into a PLA matrix to enhance flame retardancy[87]. The incorporation of 4.0 wt.% CS-P-Co significantly reduced the pHRR and THR by 23.0% and 20.0%, respectively. During combustion, the catalytic action of cobalt salts promoted the formation of a dense graphitized char layer, which effectively restricted heat, oxygen, and mass transfer. This synergistic effect between CS-P-Co and PLA improved thermal stability and flame retardancy. A chitosan-Fe3O4 nanohybrid flame retardant, HNT@CS@Fe3O4, was synthesized using halloysite nanotubes (HNT) as a template, chitosan as a char-forming agent, and Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a catalytic component to enhance the fire safety of EP[88]. The incorporation of 10 wt.% HNT@CS@Fe3O4 significantly improved flame retardancy, increasing the LOI to 31.3% and reducing the pHRR, CO production, and peak smoke production by 32.0%, 44.0%, and 33.0%, respectively. During combustion, the HNT-based nanofiller facilitated the formation of a three-dimensional network structure, restricting heat release and the diffusion of flammable components. Simultaneously, Fe3O4 catalyzed the charring process, leading to the development of a reinforced protective layer that effectively limited heat and gas transfer. A ternary chitosan-PET nanocomposite was fabricated by integrating phosphorylated chitosan and in-situ synthesized silver nanoparticles, significantly enhancing its flame retardancy[89]. The incorporation of phosphorylated chitosan provided phosphorus-containing flame-retardant sites, improving thermal stability and delaying thermal degradation. During combustion, the combined effect of phosphorylated chitosan and nano-silver promoted the formation of a reinforced char layer, which acted as a physical barrier to restrict heat release and gas diffusion, thereby enhancing fire resistance.

LBL assembly leverages chitosan's intrinsic cationic nature, making it particularly effective for improving the flame retardancy of polyurethane foam, textiles, and thermoplastic polymers like PET. Common deposition techniques such as spraying, dipping, and spin coating provide versatile application methods tailored to different substrates. A flame-retardant exoskeleton for polyurethane foams was constructed using an LBL assembly of chitosan and phosphorylated cellulose nanofibrils (P-CNF), forming a sustainable and efficient fire protection system[90]. The incorporation of 8 wt.% chitosan/P-CNF significantly enhanced flame retardancy, reducing pHRR by 31% while suppressing melt dripping and preventing foam collapse during combustion. The synergistic interaction between chitosan and P-CNF promoted the formation of a mechanically stable and thermally resistant char layer, which acted as a protective barrier, effectively limiting heat and flammable volatile release. A flame-retardant nanocoating was developed by assembling ultra-thin Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets and chitosan onto polyurethane foam via an LBL approach[91]. The incorporation of an 8-bilayer coating significantly enhanced fire safety, reducing pHRR by 57.2%, THR by 65.5%, TSR by 71.1%, and peak smoke production rate by 60.3%. Notably, the coating also decreased peak CO production and peak CO2 production by 70.8% and 68.6%, respectively, demonstrating its excellent effectiveness in suppressing toxic gas emissions during combustion. A flame-retardant silk fabric was developed using an electrostatic LBL assembly of chitosan and vitamin B2 sodium phosphate[92]. The incorporation of 10 bilayers significantly enhanced flame retardancy, increasing the LOI value to 32.8% and reducing the char length to less than 15 cm. A flame-retardant and anti-dripping coating was developed by assembling chitosan and APP onto PET fabrics via a LBL assembly technique[29]. The LOI increased from 21.1% (uncoated) to 26.2% with 20 BL of chitosan/APP. Char length decreased from 15.1 to 13.0 cm, and after-flame time reached 0 s with 5 BL. Anti-dripping performance improved, with complete elimination of dripping at 10 BL.

Chemical modification of chitosan as efficient flame retardants

-

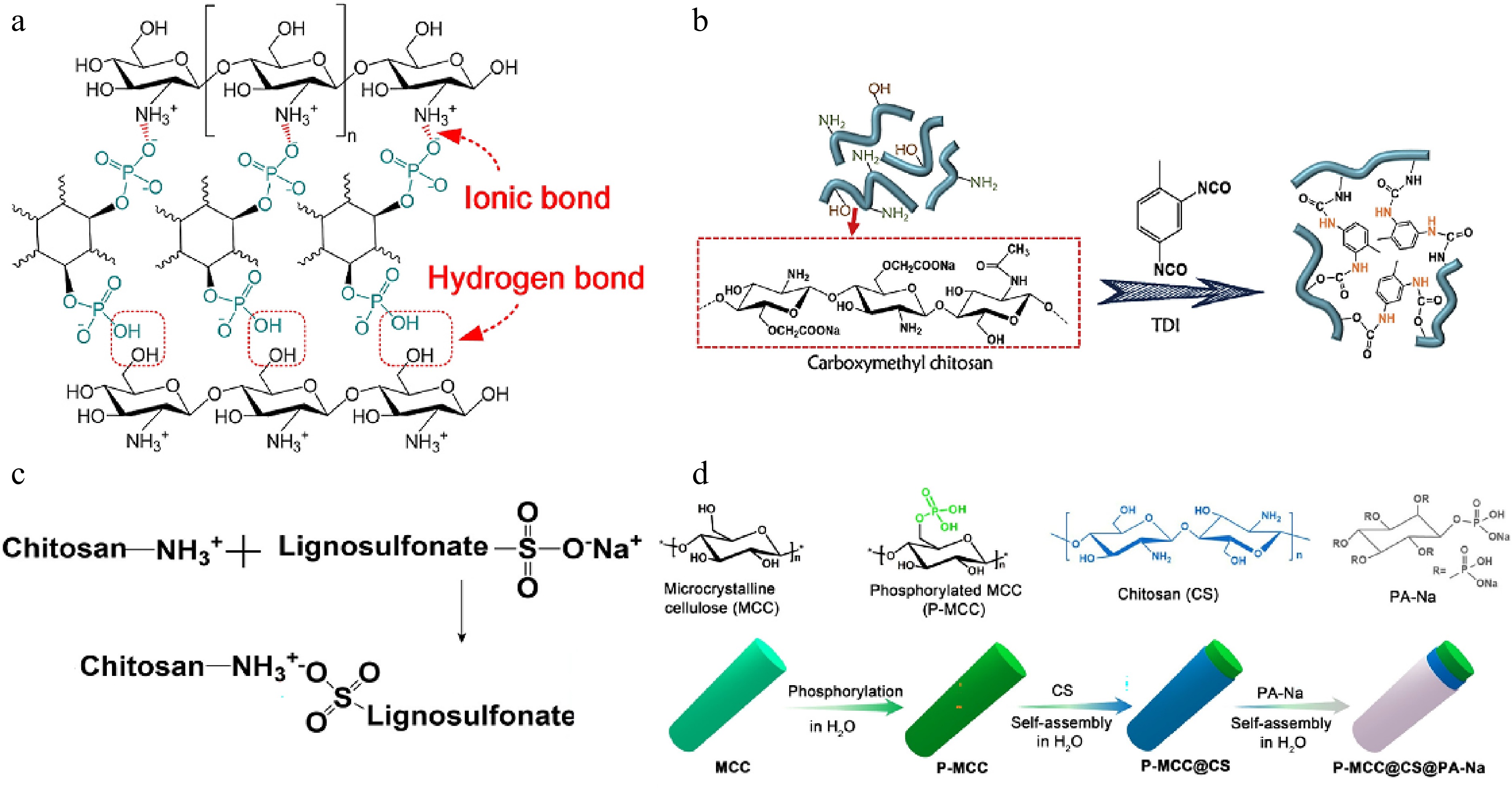

Chitosan contains several functional groups, including 3-hydroxy, 6-hydroxy, and 2-amino groups, as well as β-(1-4)-D-glucosidic linkages. The high reactivity of its amino and hydroxyl groups allows for diverse chemical modifications, such as acylation, esterification, Schiff base formation, quaternization, and graft copolymerization[93−96]. These modifications not only enhance the solubility, electrostatic properties, porosity, and mechanical strength of chitosan but also introduce flame-retardant elements or structures. By incorporating phosphorus-, nitrogen-, or silicon-containing functional groups, chemically modified chitosan derivatives exhibit improved thermal stability and char formation, making them highly effective as flame retardants in polymer systems. A chitosan-based flame retardant system was successfully developed using tannic acid/ferric salt (TAFe), and chitosan/PA (CTSPA) complexes for PLA composites, shown in Fig. 5a[97]. The incorporation of 3 wt.% CTSPA increased the LOI of PLA to 30.5% and enabled the composite to achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating with minimal melt dripping. Additionally, the combined use of 2.5 wt.% TAFe and 2.5 wt.% CTSPA reduced the pHRR and THR of PLA by approximately 19% and 37%, respectively. A flame retardant (MCMPP) was prepared by microencapsulating melamine polyphosphate with carboxymethyl chitosan cross-linked by toluene diisocyanate, shown in Fig. 5b[98]. The incorporation of 15 wt.% MCMPP increased the LOI of polyurethane to 29.4% and enabled it to achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating, even after prolonged water immersion. Additionally, 15 wt.% MCMPP significantly reduced the pHRR, THR, TSR, and carbon monoxide production of polyurethane by 65.9%, 24.1%, 87.3%, and 60.6%, respectively. In Fig. 5c, a chitosan-based phosphorus-containing flame retardant (RP@CH/LS) was synthesized by coating red phosphorus with a chitosan/lignosulfonate composite shell for EP[99]. The incorporation of 7 wt.% RP@CH/LS increased the LOI of EP to 30.6%, reduced the pHRR of EP by 59.7%, reduced the THR by 48.2% and enabled it to achieve a UL-94 V-0 rating. Char residual increased from 0.35% to 17.5% under air conditions. In Fig. 5d, another chitosan-based flame retardant (P-MCC@CS@PA-Na) was developed for EP by modifying microcrystalline cellulose with chitosan and sodium phytate[100]. The incorporation of 15 wt.% P-MCC@CS@PA-Na enhanced the flame retardancy of EP, achieving a UL-94 V-1 rating with an LOI of 26.2%. Moreover, the composite exhibited significant reductions in pHRR (50.2%), THR (25.7%), and TSP (38.6%), highlighting its effectiveness in suppressing fire hazards. The presence of P-MCC@CS@PA-Na facilitated the formation of a stable char layer, acting as a protective barrier to limit heat and smoke release. Additionally, this flame retardant improved the mechanical properties of EP due to its uniform dispersion and strong interfacial interactions with the polymer matrix, offering a sustainable and multifunctional solution for fire-resistant materials.

As discussed above, chitosan has gained attention as a sustainable flame retardant due to its intrinsic charring ability. However, its direct application is limited by poor solubility, thermal stability, and compatibility with polymers. To address these issues, two key strategies have been explored: combining chitosan with other flame retardants and chemically modifying its structure. The combination approach leverages synergistic effects with phosphorus-, metal-, or nanomaterial-based flame retardants, enhancing char formation and thermal stability. LBL assembly further improves fire resistance, enabling tailored multifunctional coatings. Notable examples include chitosan-cobalt complexes in PLA, chitosan-Fe3O4 hybrids in EP, and chitosan-based LBL coatings for textiles and polyurethane foams, all demonstrating significant reductions in heat release, smoke production, and toxic gas emissions. Chemical modifications introduce flame-retardant elements like phosphorus, nitrogen, and silicon, improving chitosan's solubility and performance. Modified chitosan derivatives, such as PA-chitosan complexes and microencapsulated chitosan-based systems, have achieved high LOI values and UL-94 V-0 ratings in PLA, polyurethane, and EP, effectively reducing fire hazards while maintaining mechanical integrity.

-

The exploration of biomass-based materials, particularly those related to starch, chitosan, and PA, has demonstrated significant potential for developing sustainable and high-performance flame retardants. Their natural abundance, cost-effectiveness, and multifunctional properties enable enhanced flame retardancy through synergistic mechanisms such as char formation, gas-phase inhibition, and thermal stability improvements. However, challenges remain in optimizing their performance while maintaining mechanical properties and processing feasibility. It should be noted that this review primarily focuses on starch, chitosan, and PA due to their widespread use and well-studied flame-retardant mechanisms. As a result, other emerging biomass-based materials, such as tannic acid, cyclodextrins, and lignin, are not discussed in detail, which may limit the scope of the conclusions. Additionally, the review emphasizes flame-retardant performance rather than life-cycle assessment or industrial scalability, which are equally important for practical applications. Future research should focus on developing advanced chemical modification strategies to enhance the compatibility and efficacy of these biomass-based flame retardants within polymer matrices. For starch-based systems, multifunctional derivatives that integrate flame retardancy with additional properties such as water resistance and antimicrobial activity could offer broader applications. In the case of PA, novel derivatives and hybrid formulations with functional fillers like MOFs and graphene hold promise for further improving fire resistance and environmental performance. For chitosan, innovations in solubility enhancement, structural modification, and LBL assembly could enable more effective incorporation into diverse polymeric materials. Moreover, sustainable modification processes that minimize environmental impact, scalable synthesis routes suitable for industrial applications, and hybrid flame-retardant systems combining biomass-based and nanomaterial components should be prioritized. The integration of nanotechnology approaches, such as graphene and nano-metal oxides, may further enhance thermal stability and mechanical properties, paving the way for next-generation flame retardants. By addressing these challenges, biomass-based flame retardants can play a crucial role in the transition toward greener and more sustainable polymer composites, meeting both industrial demands and environmental goals.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Quan Y, Zhang W, Wang Q; data collection: Quan Y, Zhang W; analysis and interpretation of results: Quan Y, Zhang W, Marquez JAD, Guo L, Tanchak R, Shen R, Wang Q; draft manuscript preparation: Quan Y, Zhang W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Yufeng Quan, Wan Zhang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Quan Y, Zhang W, Marquez JAD, Guo L, Tanchak R, et al. 2025. Sustainable biomass-based flame retardants: recent advances in starch, phytic acid, and chitosan systems for polymeric materials. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e016 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0014

Sustainable biomass-based flame retardants: recent advances in starch, phytic acid, and chitosan systems for polymeric materials

- Received: 18 June 2025

- Revised: 09 July 2025

- Accepted: 16 July 2025

- Published online: 27 August 2025

Abstract: The increasing demand for flame-retardant polymeric materials in industrial applications has stimulated significant interest in sustainable fire protection strategies. Most polymers are intrinsically flammable, posing serious fire risks during use and processing. While conventional flame retardants, including halogenated compounds, phosphorus-based additives, metal hydroxides, and silicon-containing materials, have been widely used, growing environmental and health concerns necessitate the development of greener alternatives. Biomass-based flame retardants have emerged as promising candidates due to their renewability, inherent carbon-forming ability, and compatibility with polymer matrices. This review specifically focuses on starch, chitosan, and phytic acid because of their abundance, cost-effectiveness, and well-documented flame-retardant mechanisms. The evaluation methods for polymer flame retardancy, including thermal stability and flammability tests, as well as techniques for analyzing both gaseous and condensed-phase mechanisms, are systematically discussed. Furthermore, the latest advances in starch, chitosan, and phytic acid-based flame retardants are reviewed from the perspective of combination strategies and chemical modifications. The discussion highlights their synthesis, structural modifications, and processing techniques, along with their integration into polymeric matrices and the resulting flame-retardant performance. The review aims to provide a comprehensive foundation for the rational design of efficient, biomass-based flame-retardant systems with potential scalability for industrial applications.

-

Key words:

- Biomass /

- Flame retardants /

- Polymer /

- Starch /

- Phytic acid /

- Chitosan