-

The development of industries poses a serious threat to the environment through the discharge of nonbiodegradable, highly toxic heavy metal ions into water bodies[1] . Even at low concentrations, they cause adverse effects by accumulating in the skeletal systems of humans, animals, and plants[2,3]. As a result, heavy metal pollution in aquatic systems has become a global concern. Studies investigating the mineralogical and chemical nature of these wastes under data science frameworks provide deeper insights into their environmental impact[4]. Among these, lead (II) and copper (II) ions are recognized as particularly toxic heavy metal pollutants frequently used in numerous industries[5]. In addition to metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), other porous materials such as porous organic polymers (POPs) with multiple active sites have also demonstrated high and reversible adsorption efficiency for various ionic contaminants, including tri-iodide ions, highlighting the growing potential of porous frameworks for water purification[6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines from 2008, 1.3 and 0.01 mg/L are the maximum permissible concentration for Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions in drinking water, respectively[7,8]. In humans, both these ions cause serious neurological disorders as well as organ failure disorders[9,10]. Effective treatment technologies are crucial for providing clean water to both humans and the ecological environment in affected regions[11] .

Several methods, such as membrane technology[12], chemical precipitation[13], reverse osmosis[14], electrochemical methods[15], superhydrophobic aerogels[6] , and adsorption have been employed to separate toxic metal ions from water[16]. However, these techniques have some intrinsic limitations; for example, chemical precipitation does not work at low concentrations of pollutants and produces large amount of waste material, whereas electrochemical processes involve the high cost of electricity[17,18]. When compared, adsorption emerges as a highly promising strategy for environmental remediation in industrial applications, offering advantages such as high efficiency, cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and environmental friendliness[19].

However, the selection of suitable adsorbents is crucial for ensuring an effective adsorption process. Different adsorbents such as double hydroxides, zeolites, chitosan, activated carbons, ion imprinted polymers, dendritic polymers, and organo-clay have been used for the removal of lead and copper[7,8,20−24]. These materials face challenges such as weak binding affinity, low uptake capacity, and poor selectivity. Despite attempts to improve their performance through functional modifications, they still suffer from complex preparation steps and expensive modifier usage[25].

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline structures where organic linkers and inorganic metal ions self-assemble through coordination bonds, renowned for their high porosity and customizable structures[26]. Recent studies have also highlighted the effective recovery of valuable metals from zinc-based residues using ultrasonic strengthening techniques, demonstrating the potential of zinc-based materials in environmental applications[27]. Because of their exceptional properties, MOFs have the potential to be used in various applications such as gas storage, catalysis, and adsorption[28,29]. They are gaining attention as advanced adsorbents, emphasizing the importance of low-cost, efficient synthesis methods[5]. Compared with three-dimensional (3D) MOF structures, where many active sites are poorly exposed to heavy metal ions and other contaminants, two-dimensional (2D) MOF nanosheets, with their unique structure, allow for better accessibility to their abundant active sites[30−32].

In this study, we prepared water-stable 2D zinc-based MOFs using 2-methylimidazole (2-MI) as a ligand. These MOFs have high affinity for heavy metal ions, making the adsorptive removal process highly efficient[33]. An optimized and refined approach was implemented to achieve a high product yield, ensuring scalability in technology. Afterward, this synthesized material was employed as an adsorbent to adsorb heavy metals such as Cu(II) and Pb(II) in aqueous media. The adsorption performance under different conditions (pH, temperature, dosage, and concenration) was investigated. Because of the direct synthesis method, affordable price, and excellent chemical and thermal stability, these imidazole-based Zn-MOFs have grown to be one of the most widely used MOFs[34]. This work shows their potential as an effective method for industrial and domestic water treatment to eradicate heavy metals such as Cd(II), Hg(II), Ni(II), and Co(II) ions from aqueous solutions.

-

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, >99%), 2-methylimidazole (C4H6N2), lead acetate (Pb(C2H3O2)2), copper sulphate (CuSO4·5H2O), sodium chloride (NaCl), sulphuric acid (H2SO4), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were of analytical grade. These chemicals were used without any further purification process.

Synthesis of Zn-based MOFs

-

Initially, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (2 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water to make a clear and transparent solution (Solution A). In another flask, 2-methylimidazole (1.3 g) was dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water to prepare Solution B. The two solutions were mixed using a magnetic stirrer. The resulting mixture was covered with perforated aluminum foil and left for 1 week before being centrifuged. The precipitate thus obtained was subsequently washed and dried at 60 °C to yield 2D Zn-MOF powder[35]. The synthesized material was then characterized and used in adsorption experiments for removing heavy metal ions such as lead and copper ions from contaminated water.

Characterization

-

The properties of the MOFs were determined using various characterization techniques. To investigate the surface morphology of the material, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies were performed using a Ziess scanning electron microscope (EVO LS10), which was also equipped with an X-ray detector for energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). To identify the functional groups present in the MOFs' structure, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis was performed using an FTIR spectrophotometer (FTIR, Agilent technologies, Diamond ATR (attenuated total reflectance) technique). Infrared (IR) radiation in the range from 400 to 4,000 cm−1 was used to analyze the synthesized MOFs. Crystal parameters were studied using the X-ray diffraction technique (XRD) (Bruker D8 Focus Powder XRD), and 2θ was scanned from 5° to 70°.

Batch adsorption experiment

-

For the removal of heavy metal ions from contaminated water, batch adsorption experiments were conducted. Stock solutions of 10 and 15 mg/L for copper and lead ions, respectively, were prepared using distilled water (pH 7; conductance, 4 μS/cm). Working standards were prepared using this solution, and different experiments were performed at fixed reaction parameters. Zn-based MOFs were added into samples containing metal at a fixed amount, and the reaction was carried out by placing the flask in a shaker at 150 rpm for 60 and 90 minutes. After the specified time, the solution was separated and the concentrations of copper and lead ion were analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). Adsorption capacity and removal efficiency for each experiment were calculated using Eqs (1) and (2) respectively.

$ Adsorption\;Capacity\;({q_t}) = \dfrac{{({C_o} - {C_t}) \times V}}{m} $ (1) $ {\text{%}} {\text{ }}Removal = \dfrac{{{C_o} - {C_t}}}{{{C_o}}} \times 100 $ (2) Here, C0 indicates the concentration of pollutant metal ions in mg/L, qt is the adsorption capacity in mg/g. Similarly, Ct is the concentration of heavy metal ions at time t, m is the mass (g) of adsorbent used in the adsorption experiment, and V is the volume of the solution (mL) used.

-

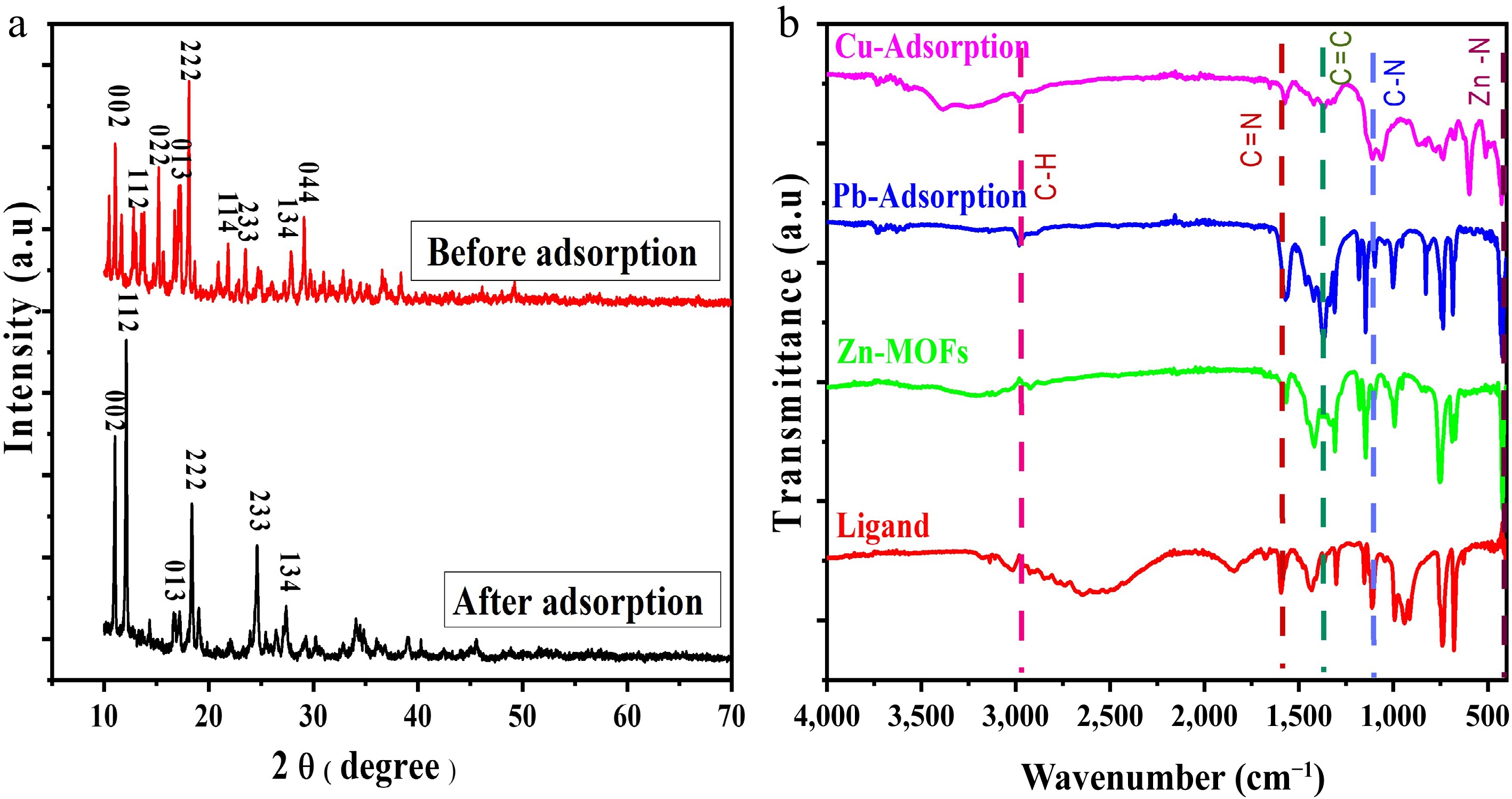

The XRD patterns of the samples before and after adsorption are shown in Fig. 1(a). The characteristic diffraction peaks of Zn-based MOFs at 2θ = 11.07, 12.8, 15.2, 17.1, 18.1, 21.8, 23.4, 27.8, and 29.1 which correspond to planes of (002), (112), (022), (013), (222), (114), (233), (134), and (044), respectively, are shown for the sample before the adsorption process. These characteristic peaks confirmed the synthesis of Zn-MOFs[36]. In case of samples produced as a result of the adsorption process, the characteristic peaks at 2θ = 11.03, 12.09, 17.2, 18.3, 24.5 and 27.3 correspond to the abovementioned planes. Peak positions were found to be almost similar in both graphs, as shown in Fig. 1a, indicating that the crystal structure was retained and the MOFs could be reused[34]. Moreover, the crystal parameters were calculated using Microsoft Origin 8.0 software and Scherrer's equation. The crystallite size was found to be around 50 Å and 519 Å for the material before and after adsorption, respectively. The size of crystallite was found to be increased, indicating maximum capture of heavy metal ions into pores of the adsorbent material.

FTIR analysis

-

FTIR spectra of the ligand (2-MI) and Zn-based MOFs before and after the adsorption of lead and copper ions are shown in Fig. 1b. Small peaks from 2,850 to 3,050 cm−1 are attributed to stretching vibrations of the -CH3 and -CH group of the imidazole ring. The peak around 1,600 cm−1 corresponds to C=N stretching vibrations in the imidazole ring[37]. A peak around 1,440 cm−1 is due to stretching vibrations of the C=C group in the imidazole ring. The peak around 1,130 cm−1 is due to stretching vibrations of the C-N group in the imidazole ring. Bending vibrations of C-H and N-H bonds are observed in the range of 1,050–1,350 cm−1. In all these spectra, except that of the ligand, the peak at around 430cm−1 is attributed to the Zn-N coordination bond, confirming the synthesis of Zn-MOFs[38]. Peaks at 680 and 730 cm−1 are attributed to the ring structure's bending vibrations, also indicating that the ring structure remained intact before and after adsorption. After the adsorption of Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions, the peaks around 526 and 750 cm−1 are attributed to Cu and Pb bonding with the MOF structure. Overall, the peaks for the main functional groups in the MOF structure remained unchanged, suggesting that these MOFs can be reused.

SEM and EDX analysis

-

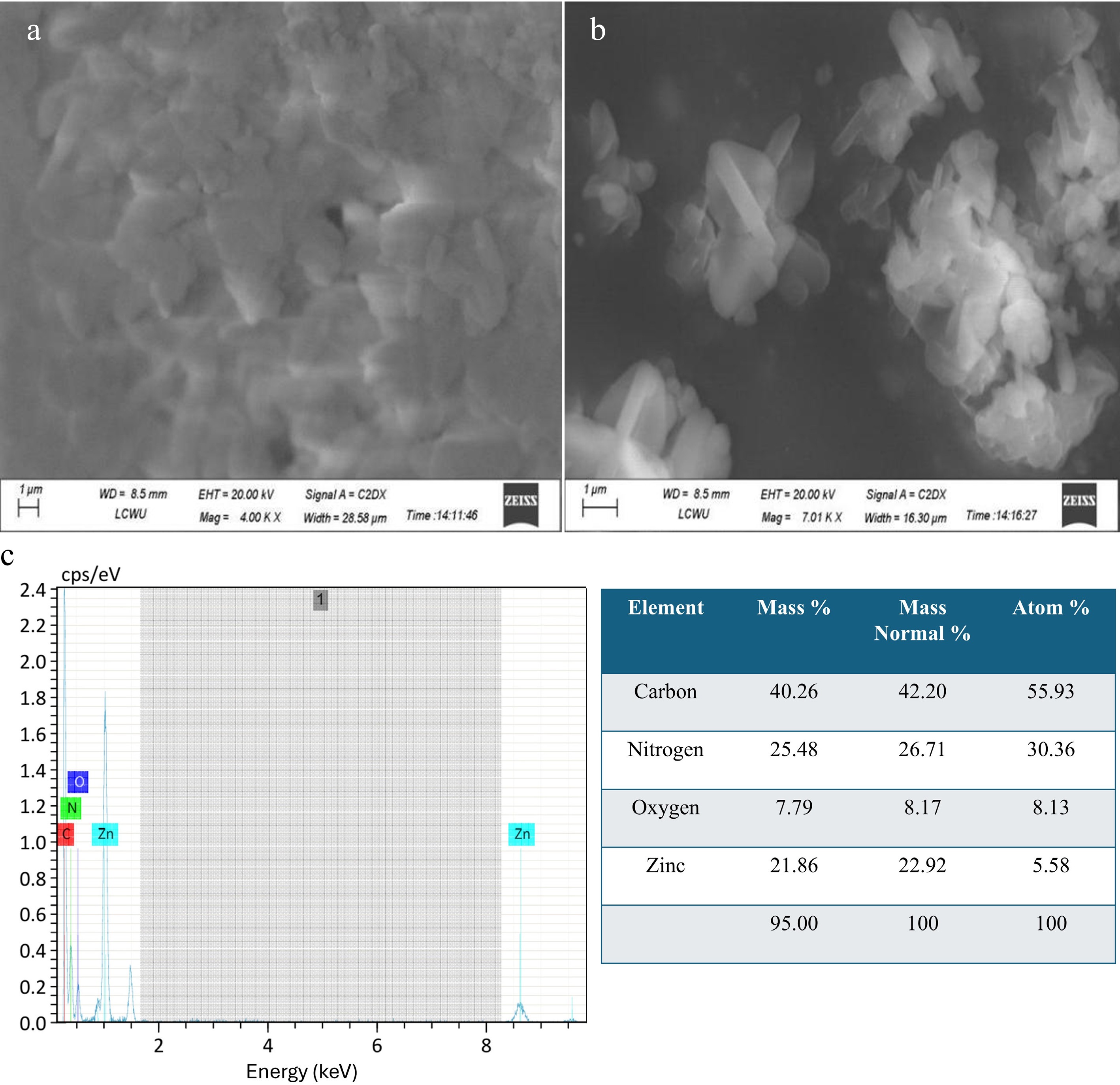

SEM studies were performed to investigate the surface morphology of zinc-based MOFs. The results shown in Fig. 2a, b reveal that the material has a somewhat cloudy appearance. The SEM images show that the Zn-MOFs primarily exhibit a flowery appearance with needle-like structures and well-defined edges. The surface of the MOFs were smooth in some places and rough when the images were taken at high magnification, with some crystals being elongated and others being relatively short. It can be seen in the images that some needle-like structures are aggregated and some are not. There are also pores in the aggregated structures that facilitate the adsorption process[34]. Because of the porous nature of these MOFs, they were selected to be used as adsorbents for removing heavy metal ions from wastewater.

Elemental distributions on the surface of Zn-MOFs were investigated using EDX analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, MOFs mainly consist of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and zinc. The percentage composition of these elements is shown in the table within this figure[39].

Batch adsorption experiment

Point of zero charge

-

The pH at which the net charge on the surface of material is zero is known as the point of zero charge (PZC)[40]. In the case of Zn-imidazole MOFs, the PZC was calculated using one of the most common methods, known as the salt addition method. From the graph, it was revealed that 7.1 is the pH at which the surface of these MOFs carries no charge[41].

Above this point, Zn-MOFs carry a negative charge, and it can easily attract positively charged surfaces or metal ions and vice versa. Therefore, in highly acidic conditions, these MOFs can effectively remove negatively charged ions instead of removing cations[36]. In the adsorption experiment, these MOFs removed the most Pb(II) ions in a basic medium, whereas the removal of copper ions was not affected by changes in the pH value. However, removal of both ions was found to be lowest in a highly acidic medium because MOFs carry a positive charge, which is why they have less affinity to attract cations in an acidic medium[42].

Effect of pH

-

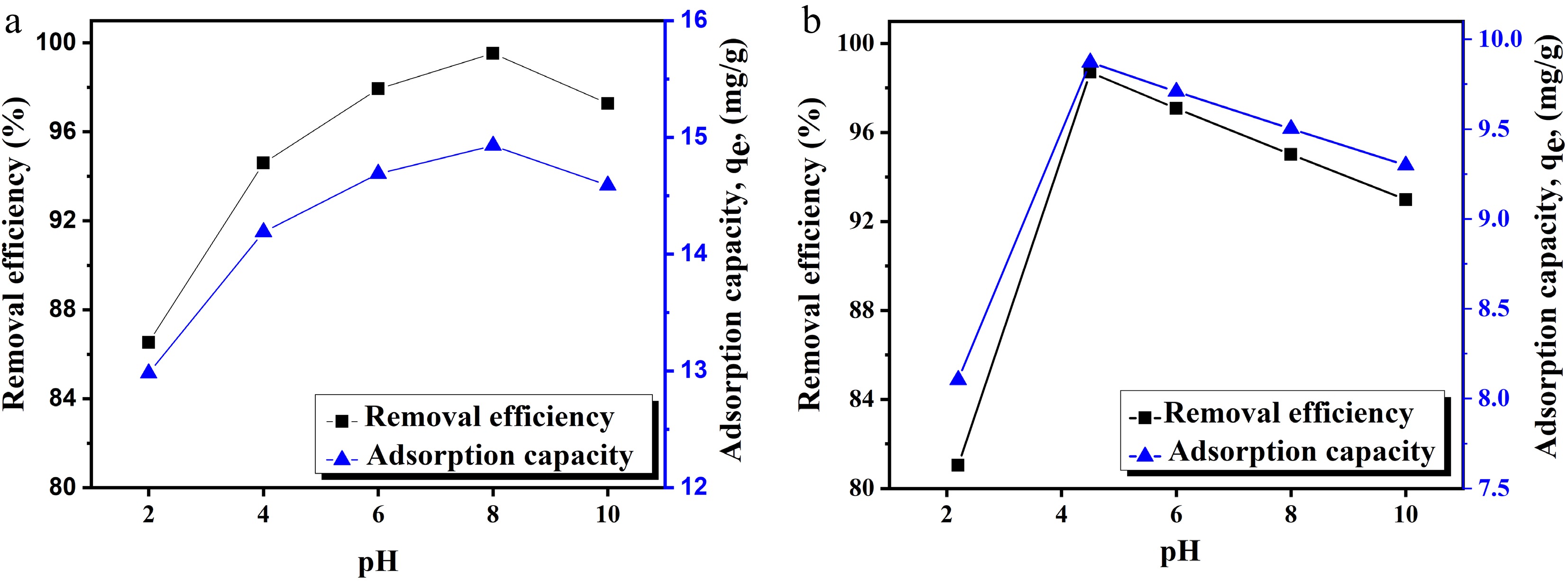

The pH of the solution strongly influences the adsorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions[43]. Since it affects the distribution of ions, as well as charge on adsorbent's surface, the effect of pH on the adsorptive removal of Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions was studied. To find the optimal pH, batch adsorption experiments were conducted across the pH range of 2–10. The reaction was carried out at 150 rpm and 30 °C. The results indicated that the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of MOFs increased with pH up to an optimal point, beyond which, both began to decrease gradually as shown in Fig. 3a, b. The PZC value explains the reason for the maximum removal of cations in a basic medium. Furthermore, at pH 4.5, Cu remains in its free ionic form, which readily binds to any available adsorbent sites. Similarly, around a neutral pH, Pb(II) ions are less tightly bound, although in a strong basic medium Pb(II) starts to form hydrolyzed complexes or precipitates, which limit further adsorption on the surface of the adsorbent. The optimum pH was found 4.5 and 8, with removal efficiency 98.7% and 99.5% for Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions, respectively.

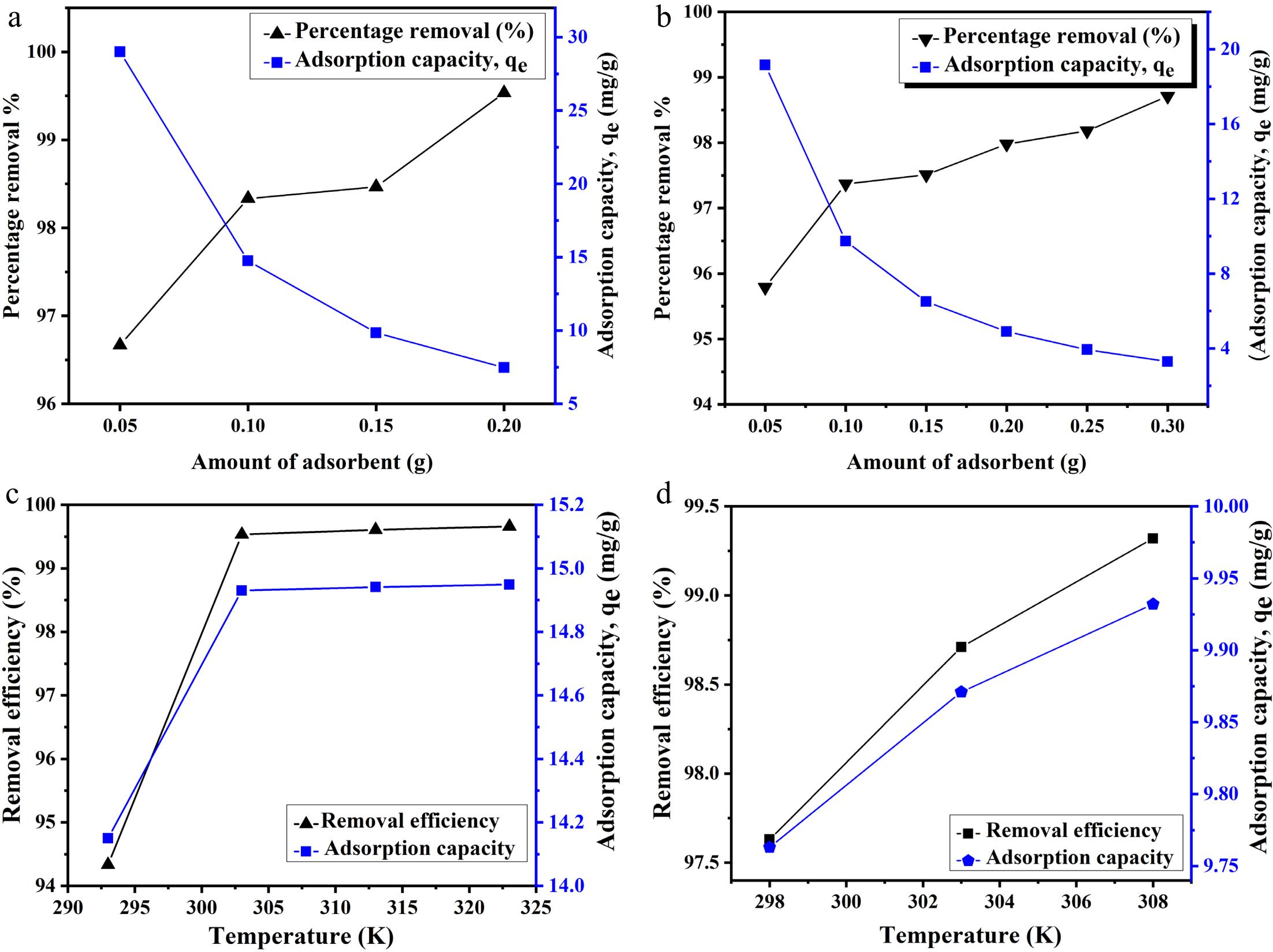

Effect of adsorbent dosage

-

To investigate the effect of Zn-MOF concentration, the dose of the adsorbent was increased from 0.05 to 0.3g in a 100-mL solution of metal ions. The reaction was carried out at the optimal pH, 150 rpm, and 30 °C. In the case of lead and copper ions, as the amount of Zn-MOFs increased, removal efficiency increased while adsorption capacity decreased, as shown in Fig. 4a, b. When the amount of adsorbent was low, its surface was surrounded by an adequate number of metal ions. As a result, all the sites were fully occupied, resulting in a higher adsorbing capacity of 19 and 29 m/g for Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions, respectively[44]. However, when the amount of adsorbent was increased, the presence of extra active sites resulted in lower adsorption capacity and maximum removal efficiency. Moreover, these results revealed that the saturation point was not reached when maximum removal was achieved, because of the presence of a large number of active sites.

Figure 4.

Effect of adsorbent dosage on removal efficiency and adsorption capacity for (a) Pb and (b) Cu ions. Effect of temperature on the adsorption of (c) Pb and (d) Cu ions.

Effect of temperature

-

The effects of emperature were investigated by conducting adsorption experiments at various temperatures. Temperatures varied from 298 to 308 K for Cu(II) ions, and from 293 to 323 K for Pb(II) ions. With the increase in temperature, adsorption capacity and removal efficiency for both metal ions were found to increase, as shown in Fig. 4c, d. The increase in these values with increasing temperature indicates that high temperature provides more kinetic energy to the adsorbing sites[45]. As a result, the ability of the adsorbent to capture metal ions from wastewater also increases.

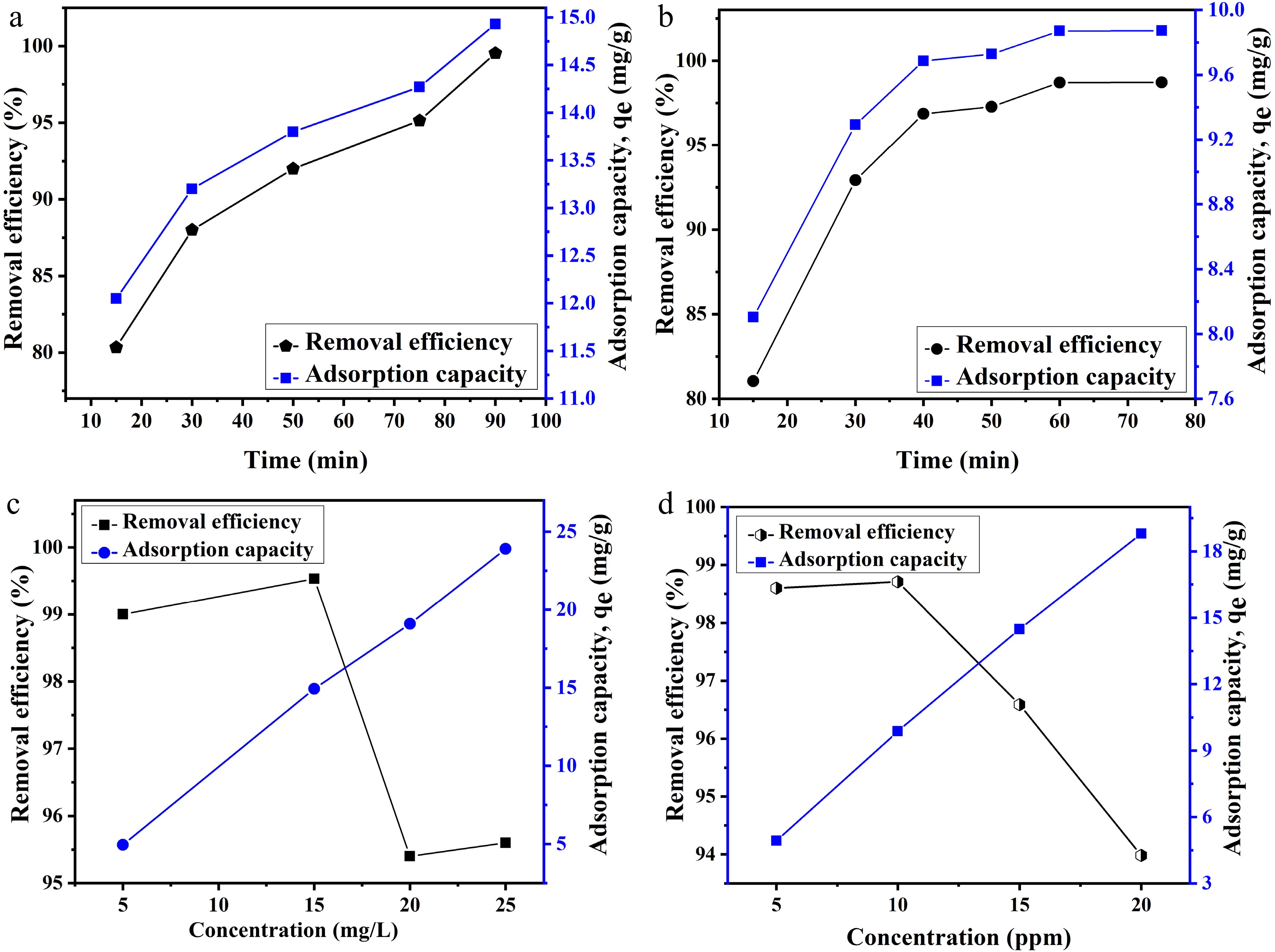

Effect of contact time

-

The effect of time on the adsorption process was investigated by varying the adsorption time from 15 to 75 and 90 min for Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions, respectively. The eaction was carried at the optimal pH, 150 rpm, and 30 °C. The adsorption capacity and removal effectiveness were measured at different time intervals, and graphs were plotted as shown in Fig. 5a, b. It was observed that with the increase in time, adsorption capacity as well as removal efficiency also increased for both metal ions. This can be attributed to the maximum availability of active sites. Speedy removal was observed in the first 30 minutes for both metal ions.

Figure 5.

Effect of time on the adsorption of (a) Pb and (b) Cu ion. Effect of the concentration of metal ions on adsorption of (c) Pb and (d) Cu ions.

Effect of the concentration of metal ions

-

Changes in adsorption capacity and removal efficiency were also investigated using solutions with different initial concentrations of 5–50 mg/L for lead and copper ions. Experimental conditions include optimial pH, 150 rpm and a 30 °C temperature. Generally, adsorption capacity for both ions was found to increase, but removal efficiency decreased, as shown in Fig. 5c, d. This is because the increased concentration of metal ions also increases the availability of adsorbate ions that can adsorb on the available active sites. As a result, the maximum number of metal ions were adsorbed, resulting in an increase in adsorption capacity[46]. Removal efficiency was found to increased from 4.9 to 18.7 mg/g and from 4.5 to 23.5 mg/g, for copper and lead ions, respectively. However, because of the presence of large numbers of metal ions compared with the available active sites, removal efficiency was found to decrease for both metal ions, as shown in Fig. 5c, d.

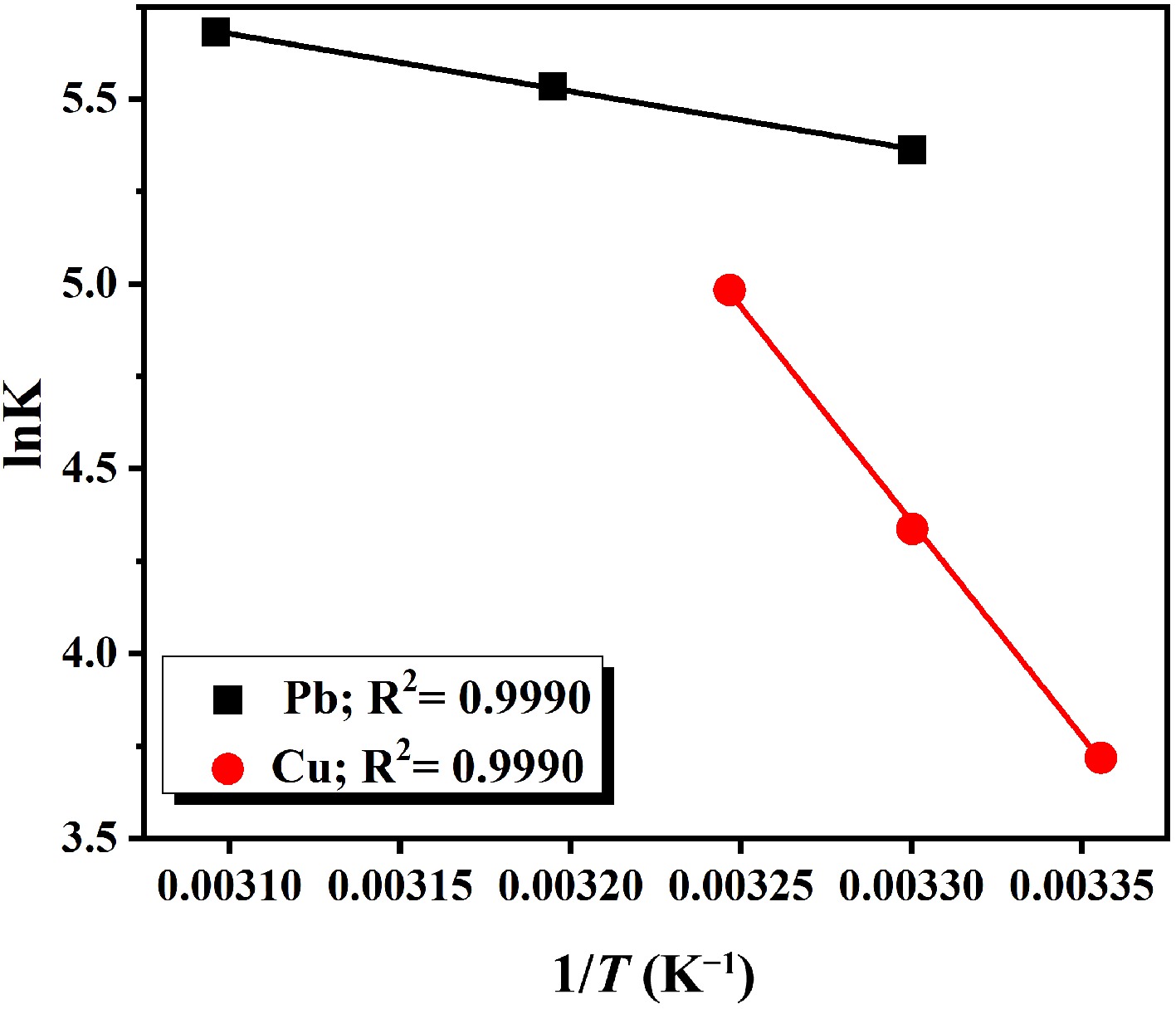

Thermodynamic study

-

To investigate thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption process, the temperature was varied from 293 to 323 K. Thermodynamic parameters such as enthalpy, Gibbs free energy, and entropy were calculated using Van't Hoff plot, as shown in Fig. 6. The straight-line equation for this plot is given as follows:

$ \Delta {\rm G} = - {\rm RT lnK }= - {\rm RT} \left(- \dfrac{\mathrm{\Delta }\mathrm{H}}{RT}+\dfrac{\mathrm{\Delta }\mathrm{S}}{R} \right) $ (3) Here, R is the general gas constant and T (K) is the temperature. Values calculated for these parameters at different temperatures are shown in Table 1. Gibbs free energy was found to be negative, indicating that the reaction is spontaneous. There was a slight increase in the values of ΔG with a rise in temperature. Higher temperature values are more effective for the adsorption process. Moreover, positive values for enthalpy suggest the endothermic nature of the adsorption process. Therefore, increasing the temperature up to an appropriate value promotes the adsorption reaction for the removal of heavy metal ions. The positive values of entropy (ΔS) indicate that the adsorption process is entropy-driven, reflecting increased randomness at the solid–solution interface.

Table 1. Thermodynamic parameters.

Copper ions Lead ions Temperature (K) 298 303 308 303 313 323 Δ G (kJ/mol) −9.2 −10.5 −12.7 −13 −14.4 −15.2 Δ H (kJ/mol) 96.6 12.9 Δ S (kJ/mol K−1) 0.35 0.08 Adsorption isotherm

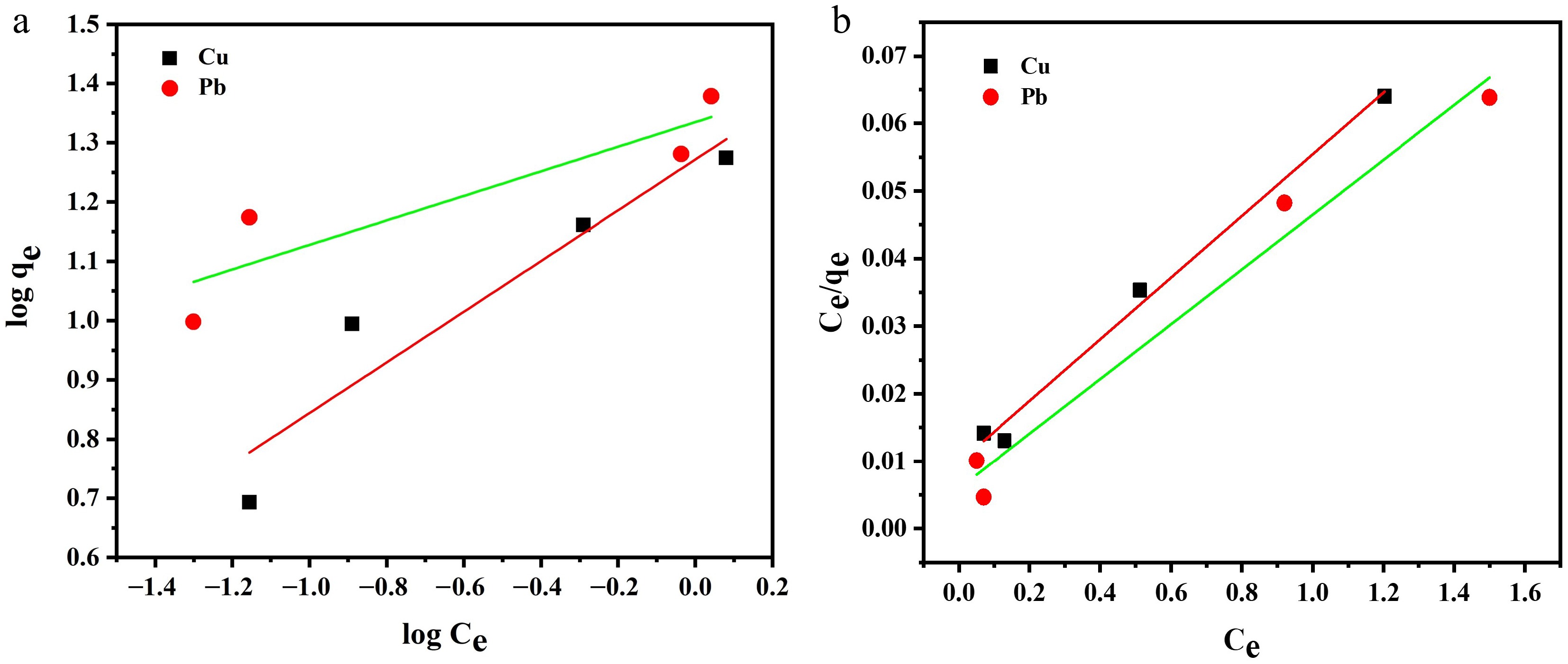

-

To properly investigate the removal mechanism of copper and lead ions and their interaction with Zn-based MOFs, adsorption isotherms were studied. Different initial metal ion concentrations were prepared, and batch adsorption experiments were performed. Adsorption equilibrium data for both metal ions were investigated by fitting both Freundlich and Langmuir adsorption isotherms (Fig. 7a, b). The Freundlich isotherm is used to study reversible and multilayer adsorption processes (Equation 4), whereas the Langmuir model (Equation 5) explains monolayer adsorptive behavior[47,48].

$ \log ( {q}_{e} ) = \log {K}_{f} + \dfrac{log{C}_{e}}{n} $ (4) $ \dfrac{{C}_{e}}{{q}_{e}} = \dfrac{{C}_{e}}{{q}_{m}} + \dfrac{1}{{{K}_{L}q}_{m}} $ (5) In the abovementioned equation, qe mg g−1) represents the equilibrium adsorption capacity, Ce (mg/L) shows the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate, Kf (mg/g) (L/mg)1/n and n are constants related to the adsorption process for the Freundlich isotherm, and qm mg g−1) is the maximum adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir adsorption constant, also known as the affinity constant, which is further used to calculate the separation factor RL[23].

The correlational coefficient (R2) was also calculated by linear fitting of these models, as shown in Table 2. Freundlich model does not fit well with these data points. Additionally, values of Kf and n were calculated using the values of the slope and intercept from the graph and are displayed in Table 2. Results revealed that the Langmuir model gave the best fitfor both metal ions, indicating a monolayer chemisorption adsorption process[49]. This was further confirmed by fitting data in the nonlinear form of the Langmuir isotherm model, supporting the conclusion of monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface for Cu(II) ions. However, for Pb(II) ions, the data fit to some extent, indicating surface heterogeneity or multilayer adsorption (data are provided as Supplementary File 1).

Table 2. Best fitting parameters for the adsorption isotherm for removal of copper and lead ions using Zn-MOFs

Adsorbate Freundlich isotherm Langmuir adsorption isotherm Kf n R2 KL qm R2 Pb 21.60 ± 0.05 4.830 ± 0.10 0.7339 6.76 ± 0.003 24.68 ± 0.004 0.9672 Cu 18.66 ± 0.07 2.341 ± 0.06 0.8510 4.65 ± 0.001 21.9 ± 0.002 0.9881 The separation factor RL was also calculated for the Langmuir model using Eq. (6).

$ {R}_{L} = \dfrac{1}{1+{C}_{o}{K}_{L}} $ (6) Here, C0 is the maximum initial concentration of metal ions and is dimensionless. This factor determines the nature of the shape of the isotherm. According to this factor, adsorption process is said to be favorable (0 < RL < 1), unfavorable RL > 1, or linear RL = 1; in the case of irreversible adsorption, RL = 0 . The values for the separation factors are shown in Table 3.

The separation factor (RL values presented in Table 3) are greater than zero but less than one for both metal ions, indicating that the adsorption process is favorable under the studied conditions. The value of the constant n from the Freundlich adsorption isotherm, shown in Table 2, also suggests the same behavior. Therefore, both these models confirm that the adsorption of heavy metal ions is a favorable process when using Zn-based MOFs.

Table 3. Calculations for the separation factor at different initial concentrations.

Copper Lead C0 (mg/L) RL ± 0.001 C0 (mg/L) RL ± 0.003 5 0.041 5 0.0287 10 0.021 15 0.00976 15 0.014 20 0.0073 20 0.010 25 0.0058 Adsorption kinetics

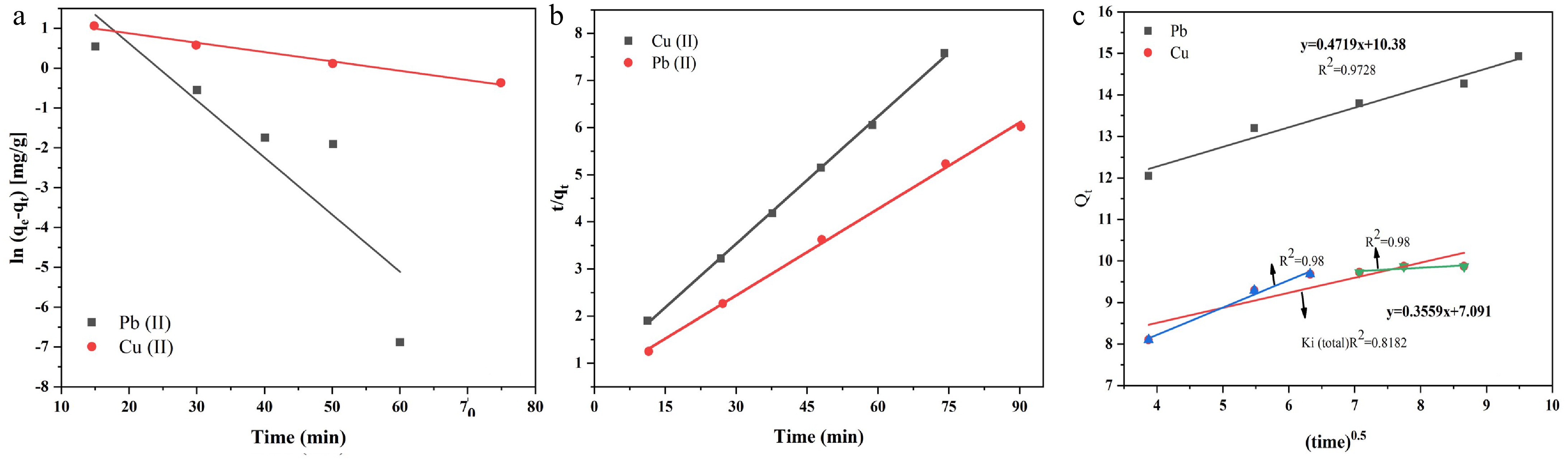

-

Kinetic studies play a crucial role in transferring technology from the laboratory to the industrial level. These studies contribute to a deeper understanding of the reaction mechanism, facilitate the analysis of experimental data, and aid in predicting optimized strategies for future operational conditions[50]. Various kinetic models, including the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order and intraparticle diffusion models were employed, as shown in Eqs (7)−(9), respectively[8].

$ \ln \;( {q}_{e} - {q}_{t} ) = \ln\; {q}_{e} - {k}_{1} t $ (7) $ \dfrac{t}{{q}_{t}} = \dfrac{1}{{q}_{e}^{2}{k}_{2}}+\left(\dfrac{1}{{q}_{e}}\right) t $ (8) $ {q}_{t} = {K}_{i}{t}^{0.5} + C $ (9) Here, k1, k2, and Ki represents rate constants for the pesudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order and intra-particle diffusion models. The values of these constants are shown in Table 4 along with the R2 values. The R2 values served as the basis to find best fitting model.

Table 4. Best fitting kinetic parametres for the removal of copper and lead by Zn-MOFs.

Adsorbate qe (mg/g) Experimental Pseudo-first-order Pseudo-second-order k1 qe calculated (mg/g) R2 k2 qe calculated (mg/g) R2 Pb 14.93 −0.024 ± 0.08 3.658 ± 0.044 0.9831 0.0125 ± 0.08 15.52 ± 0.001 0.9977 Cu 9.87 −0.014 ± 1.8 34.88 ± 0.001 0.7066 0.024 ± 0.05 10.44 ± 0.001 0.9993 Pseudo-first-order kinetics

-

On the basis of the regression coefficient values, the adsorption of lead ions follows the first-order kinetic model, but for copper ions, it does not fit best, as shown in Fig 8a. Furthermore, for determining the best fit, when the experimental and calculated values of adsorption capacities are compared, a large difference appears between these values. These results indicate that the adsorption of lead and copper ions does not follow pseudo-first-order kinetics[38].

Pseudo-second-order kinetics

-

The plot for the pseudo-second-order kinetic model shown in Fig 8b, suggesting that this is the best fitting model for both metal ions. The R2 values for both models are shown in Table 4. Moreover, when the experimental and calculated values of adsorption capacity are compared, they were found to be closer to each other. These results indicate teh better fit of the pseudo-second-order model as compared with the pseudo-first-order model. Consequently, it is concluded that adsorption follows a partial-second-order rate mechanism. Thus, the adsorption rate is directly proportional to square of number of free adsorption sites[24,51].

Figure 8.

(a) Pseudo-first-order kinetic model. (b) Pseudo-second-order kinetic model. (c) Intraparticle diffusion model.

Intraparticle diffusion model

-

Weber and Moris proposed the intraparticle diffusion model to investigate mechanisms of adsorption. According to this model, if the plot is linear then the process mainly involves a diffusion mechanism, but if the plot exhibits a multilinear fit for the data points, then the process involves two to three steps to control the reaction mechanism[52]. Fitting experimental data into this model provides a linear graph for lead ions but a two-phase graph for copper ions. For lead ions, the linear plot indicates that adsorption is mainly controlled by the diffusion of adsorbate ions from the solution to the surface of the adsorbent. However, for copper ions, in the initial stages, the adsorption is mainly caused by surface interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent. In the second phase, it involves a diffusion mechanism, as indicated by the R2 value for Ki1 < Ki2.

Adsorption mechanism

-

On the basis of the abovementioned characterization results, kinetic analysis, and isotherms, a possible mechanism can be proposed for the removal of copper and lead using Zn-MOFs. The process of adsorption is usually controlled by two main mechanisms, including the liquid phase mass transfer mechanism and the particle diffusion mechanism. According to the pseudo-second-order kinetic studies, the adsorption process is mainly chemisorption, which involves strong interactions between the asdsorbate and the surface of adsorbent molecules. According to the intraparticle diffusion model, removal of lead ions mainly involves diffusion, which might be supported by electrostatic interactions. However, for copper ions, a diffusion process is involved, along with other processes (such as electrostatic charge). Similarly, FTIR studies also indicate chemical bond formation between the adsorbent and metal ions, suggesting chemisorptive adsorption behavior. Therefore, it can be concluded that the adsorption of lead and copper ions involves electrostatic bond formation between the adsorbate and Zn-MOFs

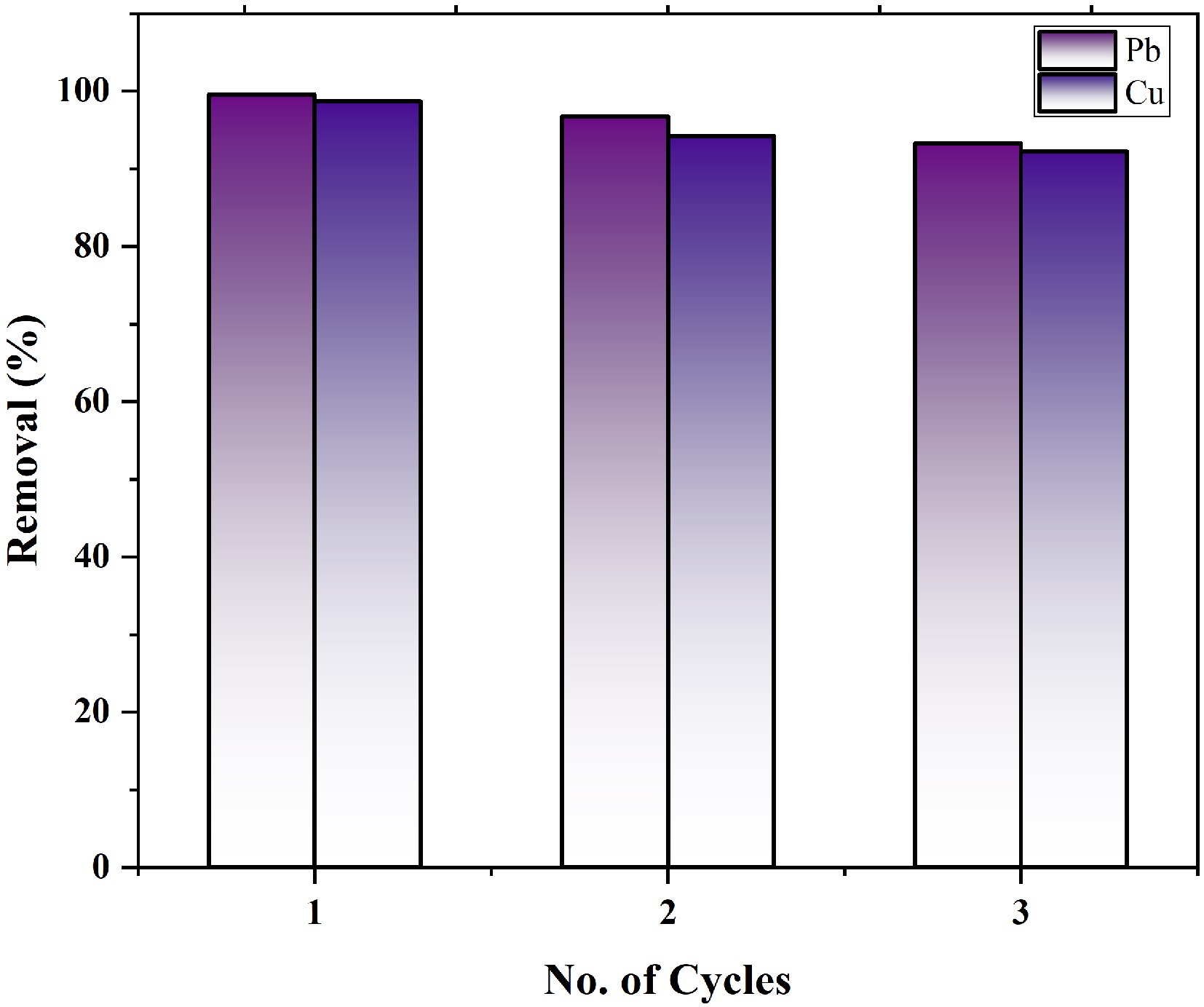

Reusability

-

MOFs remaining as a residue after a contact time of 60 and 90 min were centrifuged, separated, dried, regenerated, and used for lead and copper ion removal without any chemical treatment. The adsorption capacity and removal effectiveness of this residual material was calculated using Eqs (1) and (2). For three successive cycles, the percentage removal is shown in Fig. 9. Removal efficiency was found to be around 93% and 92% for lead and copper ions, respectively. These results suggest that zinc-based MOFs are an efficient and cost-effective adsorbent that can be reused for at least three or four cycles without any treatment[23]. Metal loaded on the MOFs was discarded by encapsulating it in inert matrices to prevent environmental pollution.

Comparison with conventional adsorbents

-

Numerous studies have been reported regarding the use of low-cost natural materials, such as nutshells[53], citrus peel[54], rice bran[55], and rice husk[56], for the adsorption of heavy metals like Pb(II) and Cu(II). These biosorbents are valued for their environmentally compatible and cost-effective nature. However, they typically lack some intrinsic properties such as the well-defined porosity, surface area, and chemical stability required for high-performance reusable adsorbents.

In contrast, the zinc-based MOFs developed in this study offer significant improvements, including a highly porous structure, superior adsorption capacity, and excellent regeneration over multiple cycles (Table 5). These features make our MOFs promising candidates for real-world wastewater treatment applications, particularly when high selectivity and reusability are required.

Table 5. Comparison of different parameters of various natural adsorbents with Zn-MOFs.

Serial no. Adsorbent Adsorbate Adsorption capacity (mg/g) Cost effectiveness Removal percentage Industrial application potential Ref. 1. Almond shells Pb(II) 3.58 Very high 80.3% Moderate [53] 2. Walnut shells Pb(II) 3.59 Very high 82.7% Moderate [53] 3. Neem leaves Pb(II) 22.33 Very high − Moderate [53] 4. Citrus peel Pb(II) 23.04 High 97.08% Low to moderate [54] 5. Rice bran Cu(II) 5.93 High − Moderate [55] 6. Rice husk Cu(II) 10.93 High 85% Moderate [56] 7. Our Zn-MOFs Pb(II) and Cu(II) 29 and 19 Moderate 99.5% and 98.7% High − Economic model comparison

-

This method appears to be cost-effective because of its simplicity, low operational costs, and minimal energy consumption. The use of zinc nitrate, 2-MI, and water makes it an economical and scalable option, especially for large-scale applications. Some biosorption methods also offers a cost-effective solution through the use of biosorbents, but additional preprocessing steps like drying and grinding increase the operational costs[57]. Similarly, the use of nanocomposites as adsorbents involves complex synthesis methods that increase both the material and operational cost[58]. Consequently, the short synthesis time, minimal adsorption time, and low environmental impact all contribute to the overall cost-effectiveness of Zn-MOFs.

-

This study highlights the potential of Zn-based MOFs as an efficient adsorbent. Heavy metals such as Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions from contaminated water were removed using these MOFs. These zinc-based metal–organic frameworks exhibited a large surface area, excellent stability, and the availability of abundant active functional groups. All these characteristics make this material a strong candidate and effective solution for removing toxic heavy metal ions. The pseudo-second-order kinetic model was followed for adsorptive removal of copper and lead ions. Moreover, the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model also fit best with these results, which indicates a monolayer adsorption process on the surface of the adsorbent.

A removal efficiency of 98.7% for Cu(II) ions and 99.5% for Pb(II) ions, along with high adsorption capacities of 19 mg/g for Cu2+ and 29 mg/g for Pb2+, was achieved. These results highlight the potential of this material for large-scale wastewater treatment applications. Additionally, integrating these MOFs with existing treatment technologies could further intensify its applicability, making it a valuable tool for dealing with environmental damage. These findings emphasize the promise of Zn-based MOFs as an efficient solution for removing heavy metalions from contaminated water, contributing to environmental protection and safeguarding the ecosystem. Further research could explore the regeneration and reuse potential of these MOFs for practical applications.

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia, for supporting and funding this research through project number TU-DSPP-2024-26.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Kinza Farooq contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and original draft preparation. Mohsin Siddique supervised the project, contributed to the study design, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Khalid J. Alzahrani participated in data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. Khalaf F. Alsharif contributed to the validation, visualization, and project administration. Faud M. Alzahrani assisted with resources, data curation, and final manuscript review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary File 1 Data of surface heterogeneity and multilayer adsorption characteristics of Pb(II) .

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Farooq K, Siddique M, Alzahrani KJ, Alsharif KF, Alzahrani FM. 2025. Zinc-based metal–organic frameworks for high-efficiency adsorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions from an aqueous solution: synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e015 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0015

Zinc-based metal–organic frameworks for high-efficiency adsorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions from an aqueous solution: synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation

- Received: 19 April 2025

- Revised: 31 May 2025

- Accepted: 14 July 2025

- Published online: 27 August 2025

Abstract: Heavy metal ions in water can be extremely toxic, even in trace amounts, endangering the ecosystem and posing serious threats to the natural environment. Therefore, their removal from contaminated water is of utmost importance. Among various methods, adsorption has proven to be one of the most effective techniques for treating water contaminated with heavy metals. Due to unique structural and dimensional properties, metal–organic frameworks have drawn ample research interest as effective metal ion adsorbents. This study focuses on adsorption process for the removal of lead (Pb) and copper (Cu) ions from polluted water. A new metal–organic framework was synthesized using simple, easy, cost-effective single-step synthesis method. Nanoadsorbent metal–organic frameworks exhibited excellent stability, a large surface area, and prominently exposed active sites for lead (II) and copper (II) ions. Batch adsorption experiments at 30 °C showed the removal of 98.7% of copper (II) and 99.5% of lead (II) ions at pH 4.5 and 8 in 60 and 90 min, respectively. Similarly, the maximum adsorption capacity was found to be 19 and 29 mg/g, for Cu(II) and Pb(II) ions, respectively. A 10-fold increase in crystallite size was observed after three cycles of using the material untreated for Pb(II) removal, giving a removal efficiency greater than 90%. Adsorption followed pseudo-second-order kinetics and best fit the Langmuir adsorption isotherm for both metal ions. This adsorption behavior can be easily explained by the value of the point of zero charge. Moreover, thermodynamic studies reveal that the adsorption process for heavy metal ion removal is spontaneous and entropy-driven, and involves the endothermic adsorption reaction.

-

Key words:

- MOFs /

- Adsorption /

- Lead (Pb2+) /

- Copper (Cu2+) /

- Water treatment