-

Protein N-glycosylation is one of the most common and functionally relevant post-translational modifications, influencing protein folding, stability, and biological activity in both plants and animals[1,2]. Analysis of these N-linked glycans is critical in a range of fields, from food authenticity and quality assessment to biomedical research, with glycoprotein profiling offering insights into species origin, allergenicity, and product integrity[3−5]. Among the analytical tools available, peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidases (PNGases, EC 3.5.1.52) serve as an indispensable tool for enabling the specific release of N-glycan chains from glycoproteins and glycopeptides.

Currently, commercial PNGases such as PNGase F and PNGase A dominate glycomic and glycoproteomic workflows; however, each exhibits notable limitations. PNGase F, while readily expressed recombinantly in E. coli and highly efficient at cleaving mammalian-type N-glycans, is unable to remove plant- and insect-type glycans containing core α1,3-fucose substitutions[6,7]. Conversely, PNGase A can release such as α1,3-fucosylated N-glycans but is only available from plant sources (such as almond), does not express in standard microbial systems, and itself is a glycoprotein, leading to sample contamination by auto-deglycosylation and challenging large-scale production[8]. As glycoproteomic studies expand to cover diverse matrices—including edible plant materials and processed foods—these enzyme limitations constrain reliable N-glycan profiling and downstream analysis.

In response, novel PNGases from bacterial sources have been explored over the last decade, with emphasis on enzymes showing robust activity even under acidic conditions, broad substrate specificity (releasing both mammalian- and plant-type N-glycans including core α1,3-fucosylated and xylosylated structures), high stability, and suitability for recombinant expression in E. coli[9]. Of particular note are the 'PNGase H+ family', originally identified in Terriglobus roseus, and subsequently from other acidobacterial and proteobacterial species[10]. These enzymes combine the substrate versatility of PNGase A with the recombinant tractability and sequence homogeneity of PNGase F, featuring optimal activity at low pH, no dependency on metal ions, and high storage stability—key attributes for high-throughput glycoprotein analysis in food science and glycoengineering[11−13]. Two recent studies on a PNGase from Rudaea cellulosilytica (PNGase Rc) demonstrated excellent deglycosylation efficiency across animal- and plant-derived substrates, and innovative applications in extracting N-glycans from complex matrices such as mouse plasma and Arabidopsis tissues, confirming the value of bacterial PNGases as universal tools for N-glycoproteomics[14,15].

Building on this progress, the present study describes the identification, recombinant expression, biochemical characterization, and potential food analysis applications of a previously uncharacterized PNGase H+ (AmePNG) from Amycolatopsis mediterranei—a filamentous actinomycete recognized for its industrial and biotechnological significance[16]. The activity of AmePNG was profiled under acidic conditions, with substrate specificity assessed using plant and animal glycoproteins, and structural insights obtained through AlphaFold modeling. AmePNG thereby represents a promising addition to the glycoanalytical toolbox, facilitating high-confidence N-glycan release in the investigation of food authenticity, allergenicity, and biotechnology-derived glycoproteins.

-

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (China) or Sangon Biotech (China), and were of analytical grade.

Gene synthesis and plasmid construction

-

The gene encoding the novel PNGase H+ from Amycolatopsis mediterranei (AmePNG, UniProt Identifier A0A0H3D2L9) was synthesized as a codon-optimized sequence for efficient expression in E. coli and commercially obtained from Genescript (Nanjing, China). For recombinant expression, the optimized gene was amplified using the primer pair AACATATGGCTGGTGCTGTTGCTTC (forward) and AACTCGAGTTCACGGTTTTCGGTG (reverse) and subsequently subcloned into the pET30a(+) expression vector through NdeI and XhoI restriction using the protocol described by Yu et al.[17].

Recombinant expression in E. coli

-

The recombinant plasmid (pET30a-AmePNG) was transformed into chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Takara, China) by standard heat-shock protocol. Recombinant protein expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells was induced by transferring approximately 20 mg of frozen bacterial glycerol stock into 5 mL of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, followed by 12 h of activation culture at 37 °C with shaking; 5 mL of this overnight culture was then inoculated into 400 mL of fresh LB medium and grown at 37 °C and 200 rpm until the OD600 reached ~0.6, at which point protein expression was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the culture was immediately transferred to an 18 °C shaker for 18 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 10 mL of Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 8.0), and lysed by ultrasonication on ice; the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min to separate the supernatant and inclusion body-containing precipitate.

Protein purification

-

While the supernatant of the cell lysate was subjected directly to Ni2+ affinity chromatography, the precipitate was solubilized overnight at 4 °C with stirring in 30 mL of solubilization buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 6 M urea, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min; the resulting supernatant was then purified using Ni2+ affinity chromatography, and the target protein was eluted with Elution Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 6 M urea, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). For refolding, the eluted protein was slowly diluted into refolding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 8 mM cysteine, 0.3 mM cystine, 1% (w/v) PMSF, pH 8.0) until the absorbance at 280 nm reached 0.02–0.05, incubated with stirring at 4 °C for 4 h, and finally concentrated using an ultrafiltration concentrator. The average yield of purified, refolded AmePNG from a 400 mL culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) was approximately 0.6 mg per preparation.

Enzyme activity and substrate specificity assays

-

Actively purified AmePNG was evaluated using standard glycoprotein substrates. Deglycosylation activity was assessed using horseradish peroxidase (HRP), bovine lactoferrin, and model plant glycoproteins. For gel-based assays, 10 μg of substrate were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, then incubated with 1 μg AmePNG in 20 μL glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.5–3.0) at 37 °C overnight. Controls with PNGase F and Rc were run in parallel.

UPLC-based analysis

-

Released N-glycans were fluorescently labeled with 2-aminobenzamide (2-AB) and analyzed by HILIC-UPLC (Waters BEH Glycan column, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 150 mm) using an acetonitrile/ammonium formate buffer gradient. Detection was performed at Ex 330 nm/Em 420 nm as previously described[18]. The optimal pH was determined by incubating enzyme reactions in buffers ranging from pH 2.0 to 7.0 (sodium phosphate–citrate buffer, 0.5 M) at 37 °C.

Mass spectrometry analysis of released N-glycans

-

For structural analysis of N-glycans released after PNGase digestion, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF-MS) was performed. Fractions of interest from HILIC-UPLC were prepared by mixing 1 μL of sample solution with 1 μL of 6-aza-2-thiothymine (ATT) matrix (0.3% w/v in 70% v/v aqueous acetonitrile) on a stainless steel MALDI target plate. The mixture was allowed to air dry at room temperature. MALDI–TOF-MS spectra were acquired in positive ion mode using a Bruker Autoflex Speed mass spectrometer. Measurements were conducted with standard settings for carbohydrate analysis. Monoisotopic masses were assigned using FlexAnalysis (Bruker) software, and glycan compositions were verified and annotated with GlycoWorkbench version 1.1[19]. Where applicable, selected ions were subjected to MS/MS fragmentation to further confirm glycan structures. All mass spectra were analyzed and annotated manually.

Structural and topological analysis

-

Predicted structural models of AmePNG were generated using AlphaFold2[20] and visualized with ChimeraX[21], and the topological spatial structure diagram was generated using Pro-origami[22].

-

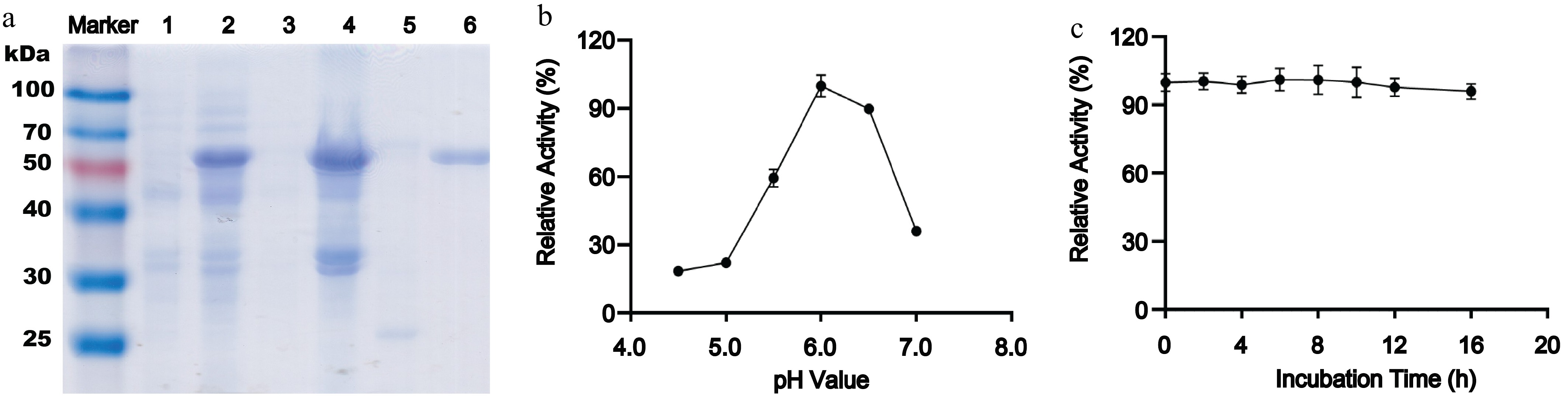

SDS-PAGE analysis indicated a single dominant band at approximately 60 kDa for purified AmePNG, corresponding to the expected molecular mass (Fig. 1a). Notably, the recombinant AmePNG exhibited very limited solubility when expressed in E. coli, and the majority of the protein accumulated as insoluble inclusion bodies, necessitating denaturation in urea and subsequent refolding to obtain active enzyme. HPLC-based activity assays revealed a secondary activity optimum at pH 6.0, with relative activity decreasing to 59% at pH 5.5, 22% at pH 5.0, and 36% at near-neutral pH (Fig. 1b). The enzyme also demonstrated remarkable stability, maintaining full activity after 16 h of incubation in sodium phosphate–citrate buffer (pH 6.0, 0.5 M) (Fig. 1c). When compared to other PNGases, most characterized PNGase H+ enzymes from bacterial sources—such as those from Terriglobus roseus (PNGase H+)[9], Rudaea cellulosilytica (PNGase Rc)[15], and Dyella japonica (PNGase Dj)[10]—display much lower pH optima, typically around pH 2.2 to 2.5, with negligible activity at higher pH values. In contrast, the well-characterized almond PNGase A, which is also active toward core α1,3-fucosylated N-glycans, has an optimum in the moderately acidic range of pH 5.0–5.5[6], which is a pH optimum much closer to AmePNG's maximum activity at pH 6.0 than to the bacterial PNGase H+ enzymes. This phenomenon shows the broader pH adaptability of AmePNG relative to both bacterial and plant PNGases.

Figure 1.

Expression, purification, and biochemical characterization of recombinant AmePNG. (a) SDS-PAGE analysis of AmePNG expression and purification. Lane Marker: protein molecular weight marker; Lane 1: uninduced E. coli cells; Lane 2: IPTG-induced E. coli cells; Lane 3: soluble fraction (supernatant) after cell lysis; Lane 4: insoluble fraction (precipitate) after cell lysis; Lane 5: AmePNG purified from the soluble fraction by nickel affinity chromatography; Lane 6: refolded AmePNG purified from inclusion bodies. (b) pH profile showing relative activity of AmePNG across different pH values. (c) Stability of AmePNG after incubation at pH 6.0 in 0.5 M sodium phosphate–citrate buffer for up to 16 h, expressed as relative activity.

N-glycan release from horseradish peroxidase (HRP)

-

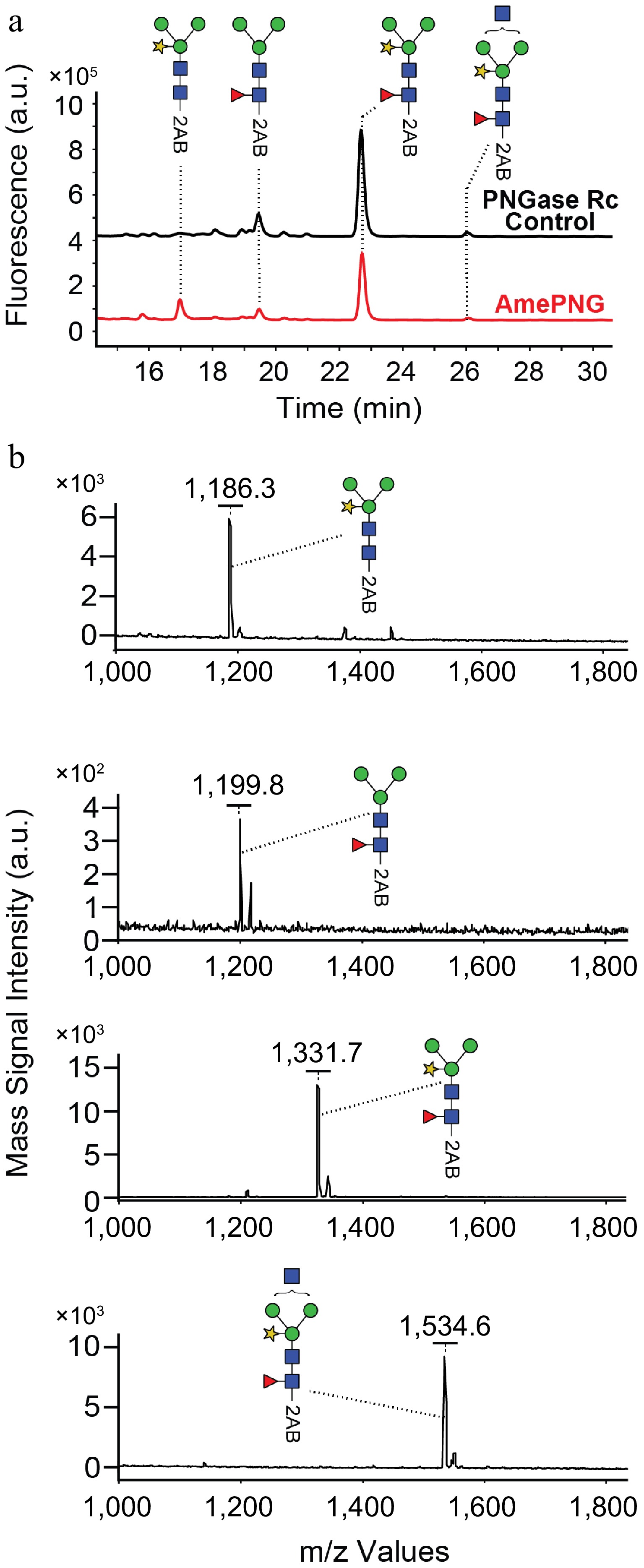

To evaluate the substrate specificity and glycan release profile of AmePNG, deglycosylation of HRP—a plant glycoprotein featuring core α1,3-fucosylated and core xylosylated N-glycans—was performed, and the released N-glycans were analyzed both by UPLC-fluorescence (Fig. 2a) and MALDI-TOF-MS (Fig. 2b).

The UPLC chromatogram demonstrated that AmePNG efficiently released major plant N-glycan species from HRP, generating a glycan profile highly similar to the reference (PNgase Rc, likely PNGase A or another plant-active PNGase)[9,14]. The principal glycan species corresponded in retention time and fluorescence intensity, suggesting that AmePNG efficiently cleaves a range of plant-type N-glycans, including those bearing core α1,3-fucose and β1,2-xylose—a structural specificity not accessible to PNGase F, which is inactive on such glycan motifs[6]. The MALDI-TOF mass spectra confirmed the release of key HRP N-glycans, with observed m/z species corresponding to 2AB-labelled plant-type N-glycans. Signals at m/z 1,186.3, 1,199.8, 1,331.7, and 1,534.6 match known HRP glycan structures featuring varying combinations of mannose, N-acetylglucosamine, xylose, and fucose moieties. Such correspondence confirms both the specificity and the completeness of glycan release by AmePNG, and demonstrates its utility for detailed glycan profiling in plant-based or mixed-source samples.

N-glycan release from bovine lactoferrin (LF)

-

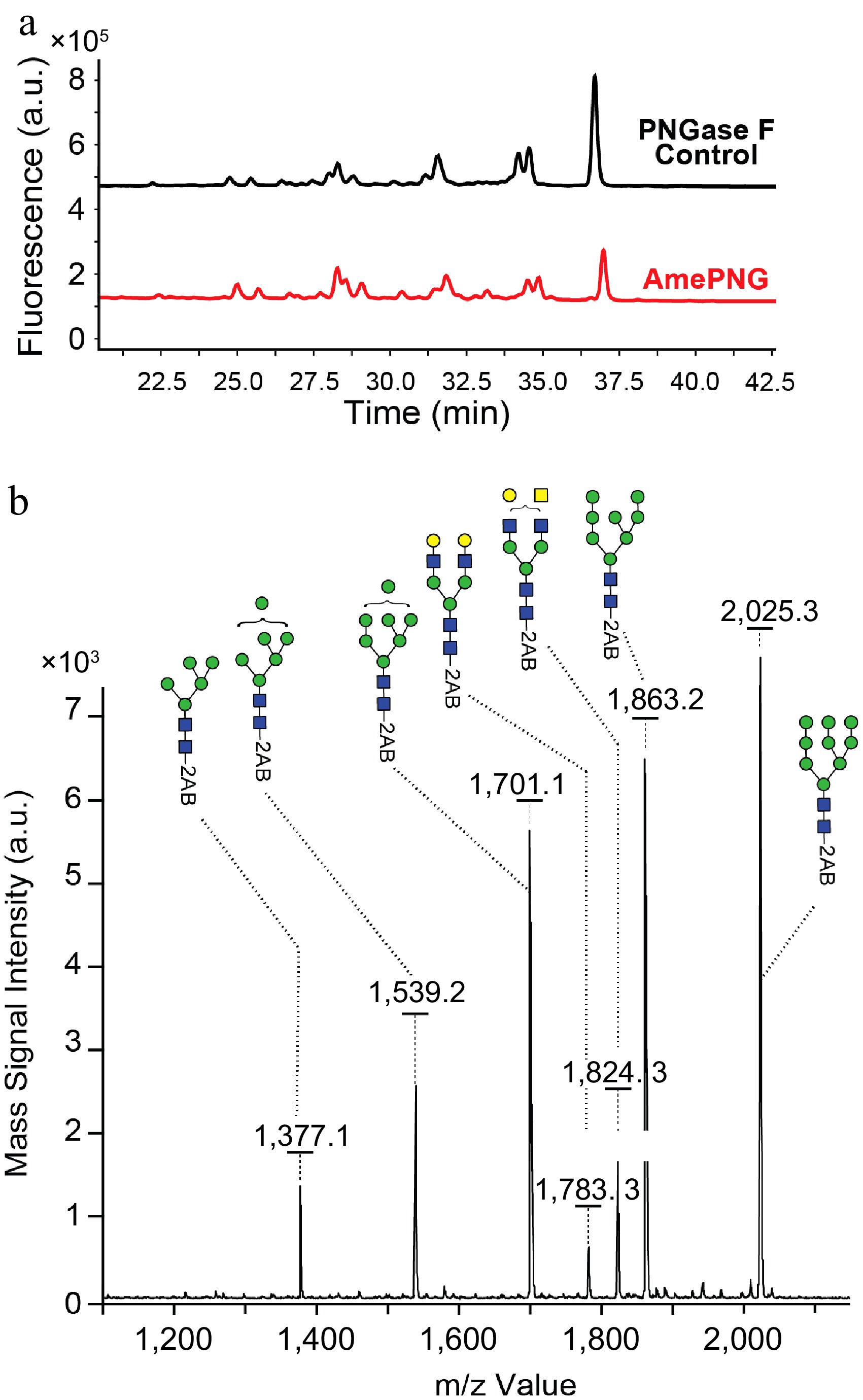

Bovine lactoferrin, a complex food glycoprotein abundant in milk bearing both complex and hybrid N-glycans, was used to further probe the substrate scope of AmePNG. UPLC (Fig. 3a) and MALDI-TOF-MS (Fig. 3b) revealed that AmePNG efficiently released all major N-glycan species found in bovine lactoferrin, with a glycan profile nearly identical to that generated by PNGase F.

Signals corresponded to mono-, bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary complex N-glycans. MALDI-TOF analysis further resolved the released glycans, including peaks at m/z 1,377.1, 1,539.2, 1,701.1, 1,783.3, 1,824.3, 1,863.2, and 2,025.3, which match the expected glycoforms for lactoferrin, demonstrating also the effectiveness of AmePNG with animal-derived substrates.

Structural and topological modeling

-

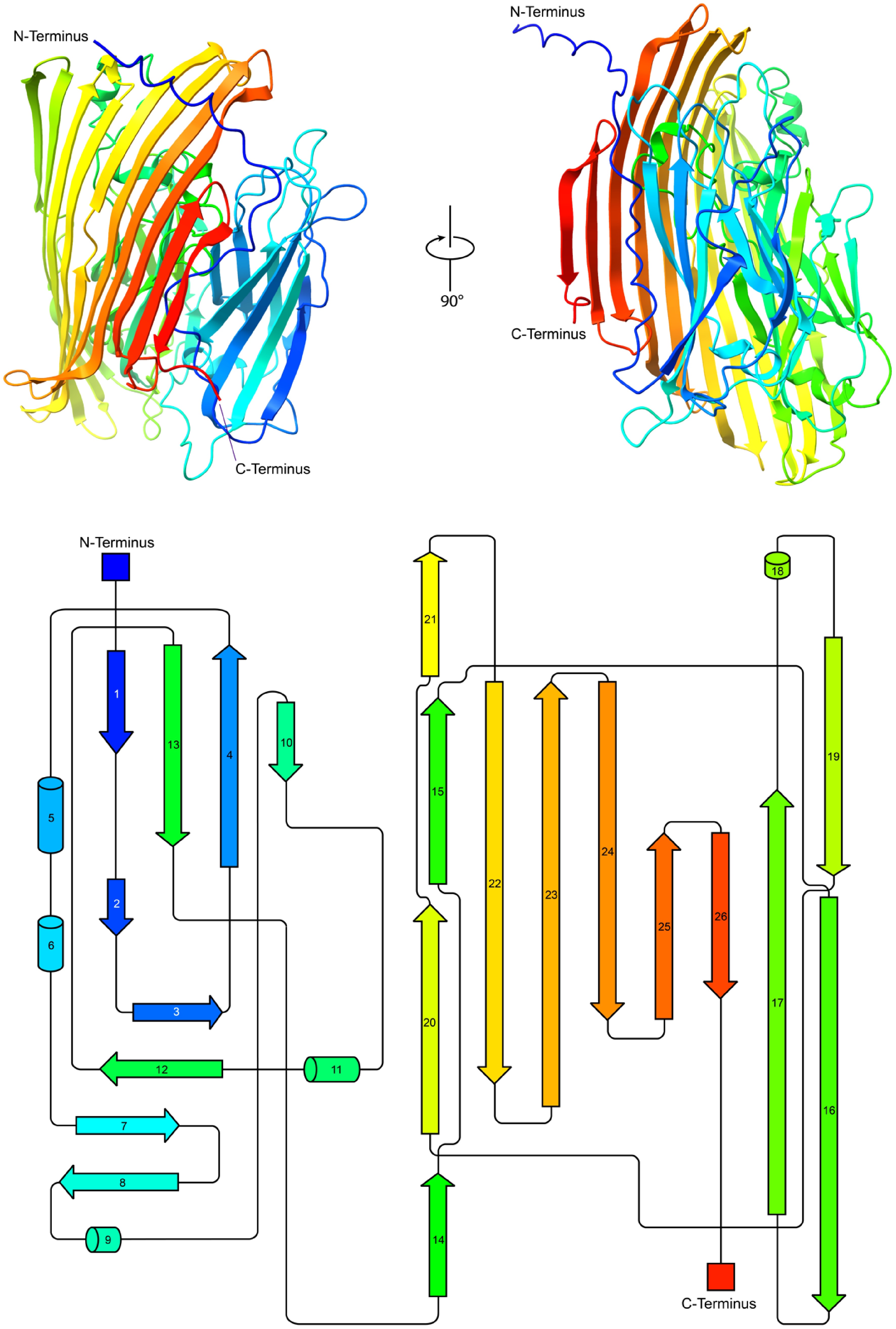

AlphaFold-based structural prediction (Fig. 4) revealed that AmePNG has a predominantly β-sheet-rich architecture reminiscent of other bacterial PNGases, with an overall sandwich-like fold and clear spatial organization from N- to C-terminus. The arrangement of β-strands and key loop regions parallels what has been described for PNGase H+ and PNGase Rc, supporting the hypothesis that these enzymes share mechanistic and substrate-recognition strategies.

Figure 4.

Structural and topological analysis of AmePNG. The top part shows cartoon representations of the predicted AmePNG structure, generated using AlphaFold2, in two orientations rotated by 90°, with the N- and C-termini indicated in red and blue, respectively. The bottom shows the corresponding topological map of AmePNG. β-strands and α-helices are represented as arrows and cylinders, respectively, and illustrate the sequential order and spatial organization of AmePNG's secondary structure.

Comparison with other PNGases and application prospects

-

Unlike PNGase F, which is ineffective against core α1,3-fucosylated glycans common in plant and insect glycoproteins, AmePNG offers a broad substrate scope, making it suitable for plant proteins, food matrices, and 'difficult' clinical or biotechnology specimens[5,23]. This property is particularly valuable for food analysis, where the authenticity and origin of ingredients can hinge on detailed N-glycan profiling.

The acidophilic performance of AmePNG, much like PNGase Rc and Dj, enables workflows incompatible with neutral or alkaline conditions—including rapid fluorescent tagging and analysis of otherwise labile sample types. Storage stability and lack of metal ion dependence further add to its practical deployment in routine and high-throughput glycoproteomics.

Sequence homology and structural comparison with other PNGases

-

A detailed sequence alignment of AmePNG with previously characterized bacterial PNGase H+ enzymes from Rudaea cellulosilytica (RcPNG), Dyella japonica (DjPNG), and Terriglobus roseus (TrPNG, Supplementary Fig. S1) was performed. This analysis revealed moderate sequence identity levels (~31% between AmePNG and these PNGases), while RcPNG, DjPNG, and TrPNG share higher identities (45%–55%). Importantly, key catalytic residues, including aspartic and glutamic acids implicated in substrate binding and catalysis, are conserved across all enzymes. A structural comparison by aligning the AlphaFold2-predicted model of AmePNG with existing AlphaFold models of DjPNG, TrPNG, and RcPNG. The latter three PNGases exhibit a highly similar overall fold, consistent with their shared family and substrate specificities (Supplementary Fig. S2). AmePNG shows a generally conserved β-sheet-rich architecture characteristic of bacterial PNGase H+ enzymes; however, it features several loop regions that fold slightly differently compared to the other PNGases. These subtle loop conformational differences lead to small but notable variations in overall structure, which may underlie AmePNG's broader pH optimum and substrate versatility.

-

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the novel PNGase H+ from Amycolatopsis mediterranei (AmePNG) is a highly active, acid-stable, and recombinant-accessible deglycosylation tool, capable of releasing all major classes of protein N-glycans from both plant and animal glycoproteins. Structural and functional analyses confirm its broad utility for glycoprotein characterization in food analysis, offering alternatives to existing PNGases for quality control and authenticity assessment in of foodstuffs.

While the current study employed purified standard glycoprotein substrates, future work will focus on evaluating AmePNG performance with complex food matrices. Such studies are essential to fully validate the enzyme's robustness, efficacy, and practical applicability in food authenticity testing and allergenicity assessment under industrially relevant conditions. Given AmePNG's broad substrate specificity, acid stability, and recombinant accessibility, it holds great potential for diverse food-related applications, including food quality control, ingredient authenticity verification, allergen profiling, and development of functional food products requiring detailed N-glycan analysis.

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; Grant Nos 31671854, 31871793, and 31871754).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu L, Voglmeir J; data collection: Wei B; analysis and interpretation of results: Wei B; draft manuscript preparation: Liu L, Voglmeir J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Sequence alignment showing the moderate homology between AmePNG and other PNGase H⁺ enzymes. Pairwise sequence identities are approximately 31.3% between AmePNG and RcPNG, 31.1% between AmePNG and DjPNG, and 31.4% between AmePNG and TrPNG. In contrast, RcPNG, DjPNG, and TrPNG share higher sequence identities ranging from 45% to 55%. Catalytically relevant residues are highlighted in green.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 AlphaFold2-predicted structural models of PNGases from AmePNG, DjPNG, TrPNG RcPNG. All four structures display the canonical β-sheet-rich fold typical of the PNGase H+ family. While DjPNG, TrPNG, and RcPNG exhibit highly similar overall folds, AmePNG shows several loop regions with distinct conformations, resulting in subtle structural differences.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wei B, Liu L, Voglmeir J. 2025. Novel PNGase H+ from Amycolatopsis mediterranei: biochemical properties and food analysis potential. Food Materials Research 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0014

Novel PNGase H+ from Amycolatopsis mediterranei: biochemical properties and food analysis potential

- Received: 07 June 2025

- Revised: 10 July 2025

- Accepted: 28 July 2025

- Published online: 29 August 2025

Abstract: Peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidases (PNGases) are essential biocatalysts for the deglycosylation of complex carbohydrates from glycoproteins, protein analysis and food quality assessment. In this study, the cloning, heterologous expression in Escherichia coli, and biochemical characterization of previously undescribed PNGase H+ enzyme (AmePNG) from Amycolatopsis mediterranei—a species known for its role in antibiotic production and fermentation processes in food biotechnology—are reported. Recombinant AmePNG showed a robust deglycosylation activity toward horseradish peroxidase (HRP), as demonstrated by HPLC analysis of released N-glycans. The enzyme's activity profile spanned a broad pH range, with maximum activity observed under acidic conditions. Structural insights were obtained through AlphaFold modeling, highlighting conserved motifs associated with the PNGase H+ family. These findings establish AmePNG as a promising tool for glycoprotein analysis in food science, facilitating the structural elucidation of plant glycoproteins relevant to food quality and processing.

-

Key words:

- PNGase H+ /

- N-glycanase /

- Glycoprotein analysis /

- Core α1,3-fucosylation /

- Enzymatic deglycosylation /

- Food analysis