-

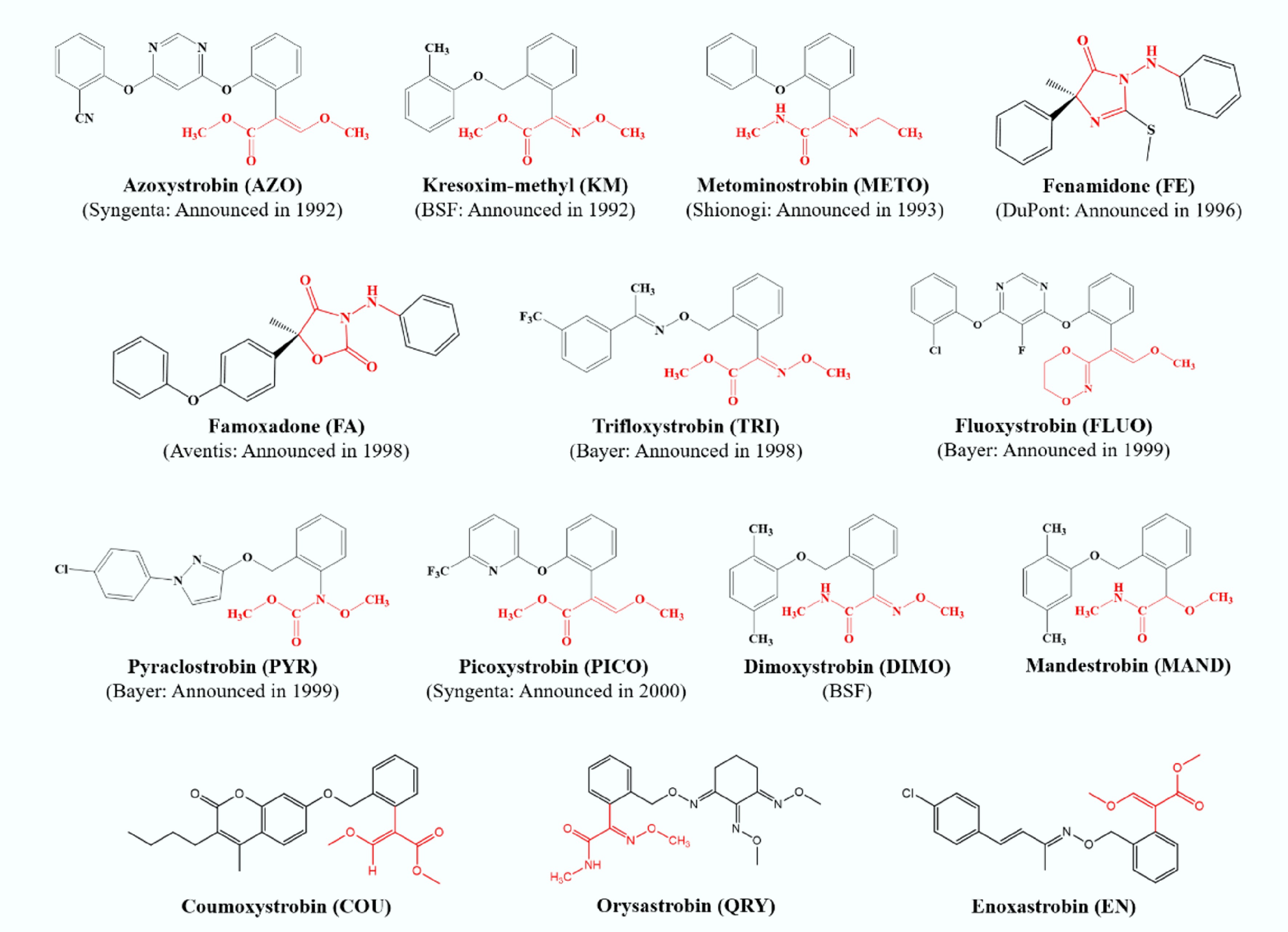

Strobilurin fungicides (SFs), a novel class of fungicides inspired by natural strobilurins, represent a significant advancement in agricultural chemical development[1]. Azoxystrobin (AZO), a pioneering commercial SF, was introduced by Syngenta in 1992[2,3]. Following its market debut in 1996, the application of AZO rapidly expanded, culminating in its status as the top-selling fungicide globally by 2014. The evolution of SFs continued with the introduction of methoxyiminoacetate derivatives, such as kresoxim-methyl (KM) by BASF in 1992, and trifloxystrobin (TRI) by Bayer in 1998[2]. This was followed by a wave of innovation, with industry leaders including Bayer, BASF, Shionogi, DuPont, and Aventis discovering and patenting a multitude of new SFs[4,5]; the timeline of these developments is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The widespread adoption of SFs in agricultural practices over several decades can be attributed to their broad-spectrum efficacy, cost-effectiveness, potent germicidal activity, and rapid degradation properties[6]. By 2016, SFs had reached the pinnacle of fungicide sales, capturing a significant 20% of the global market share[7]. Data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) reveal that in 2016, the combined application of AZO, pyraclostrobin (PYR), picoxystrobin (PICO), TRI, fluoxystrobin (FLUO), and KM in the United States reached approximately 5.7 million pounds[8], Concurrently, China's usage of these fungicides was estimated at around 10,000 tons (~220 million pounds) in 2018, underscoring the substantial reliance on SFs in major agricultural economies[9].

The widespread application of SFs has led to numerous instances of environmental contamination on a global scale, reflecting their extensive use in agriculture. For example, residues of SFs have been identified in various crops and vegetables across Europe, as well as in wheat in China. Additionally, these compounds have been detected in environmental matrices such as surface water, groundwater, and both indoor and outdoor dust in the United States[10,11]. The concentrations of SFs in aquatic systems can exceed 100 μg·L–1, posing a potential threat to aquatic biodiversity due to their increasing application in crop protection and subsequent entry into water bodies. Initially perceived as non-toxic to humans, birds, and other mammals, emerging research has revealed that SFs exhibit significant toxicity to aquatic organisms[5]. Among these, PYR, AZO, and KM are identified as the most toxic fungicides to aquatic ecosystems[8].

SFs are predominantly utilized as protectants, curative agents, and translaminar fungicides, offering versatile applications in plant disease management[12]. A pivotal factor contributing to the remarkable commercial success of AZO is its broad-spectrum efficacy against fungi from all four major classes of plant pathogens: Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, Deuteromycetes, and Oomycetes[3,12]. Biochemically, SFs are classified as quinone outside inhibitors (QoI), exerting their fungicidal activity by disrupting energy production within fungal cells, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The (E)-β-methoxyacrylate group, highlighted in red, represents the toxiphoric moiety central to the structure and function of SFs[12]. Mechanistically, SFs inhibit electron transfer at the quinol oxidation site (Qo site) of the cytochrome bc1 complex, thereby obstructing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis[2]. Furthermore, this inhibition can result in electron leakage from the mitochondrial respiratory chain, triggering cellular oxidative stress. This oxidative stress is subsequently mitigated by mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), which plays a critical role in detoxification[13].

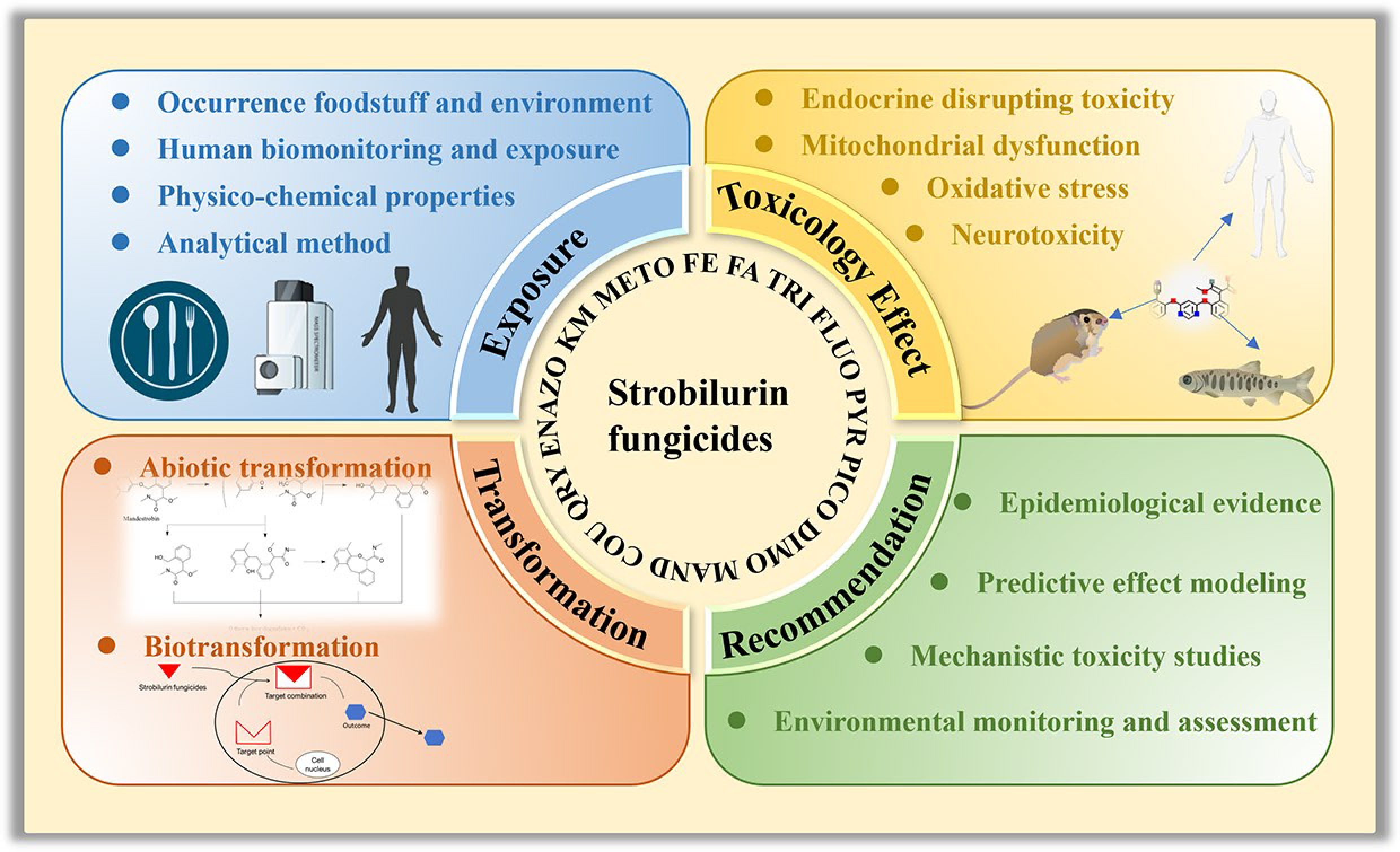

The ecological risks posed by SFs are of growing concern due to their extensive agricultural application, pervasive environmental occurrence, and unintended ecological consequences stemming from non-target toxicity. Nevertheless, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding their current environmental status, analytical detection methodologies, and toxicological profiles in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, while future research priorities remain poorly defined. Thus, in this critical review, we first compiled the occurrence of SFs across various environmental matrices, agricultural crops, and human metabolites, alongside a summary of analytical methodologies for detecting these compounds in diverse sample types. Subsequently, we delved into the toxicological impacts of SFs, encompassing mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, endocrine-disrupting effects, and neurotoxicity. Furthermore, we explored potential degradation pathways of strobilurin fungicides based on different transformation routes. Conclusively, we identified current research gaps and proposed future directions for exploration, offering recommendations to advance the current state of SF research.

-

The physico-chemical properties and structural characteristics of SFs are summarized in Table 1. Generally, all natural strobilurins share a common methyl (E)-3-methoxy-2-(5-phenylpenta-2,4-dienyl) acrylate moiety, with variations primarily occurring in the aromatic ring substitutions at positions 3 and 4. These compounds exhibit relatively complex structures, which introduce multiple metabolic reaction sites, thereby facilitating diverse metabolic pathways.

Table 1. Physico-chemical properties and structural characteristics of strobilurin fungicides

Compound Abbreviation Structure Molecular formula CAS M.W. Log Kow Log Koa Log Koc Solubility in water (mg L−1) at 20 °C Azoxystrobin AZO

C22H17N3O5 131860-33-8 403.40 1.58 14.03 3.05 11.61 Kresoxim-methyl KM

C18H19NO4 143390-89-0 313.40 3.40 − − 2.00 Pyraclostrobin PYR

C19H18ClN3O4 175013-18-0 387.80 5.45 17.32 3.48 1.43 Trifloxystrobin TRI

C20H19F3N2O4 141517-21-7 408.40 6.62 9.86 3.35 0.39 Fluoxystrobin FLUO

C21H16ClFN4O5 361377-29-9 458.80 2.86 − − 2.56 Picoxystrobin PICO

C18H16F3NO4 117428-22-5 367.30 3.60 − − 3.10 Dimoxystrobin DIMO

C19H22N2O3 149961-52-4 326.40 3.59 − − 3.50 Metominostrobin METO

C16H16N2O3 133408-50-1 284.30 3.69 10.11 2.24 158.00 Mandestrobin MAND

C19H23NO3 173662-97-0 313.40 3.51 − − 15.80 Fenamidone FE

C17H17N3OS 161326-34-7 311.40 2.80 − − 7.80 Famoxadone FA

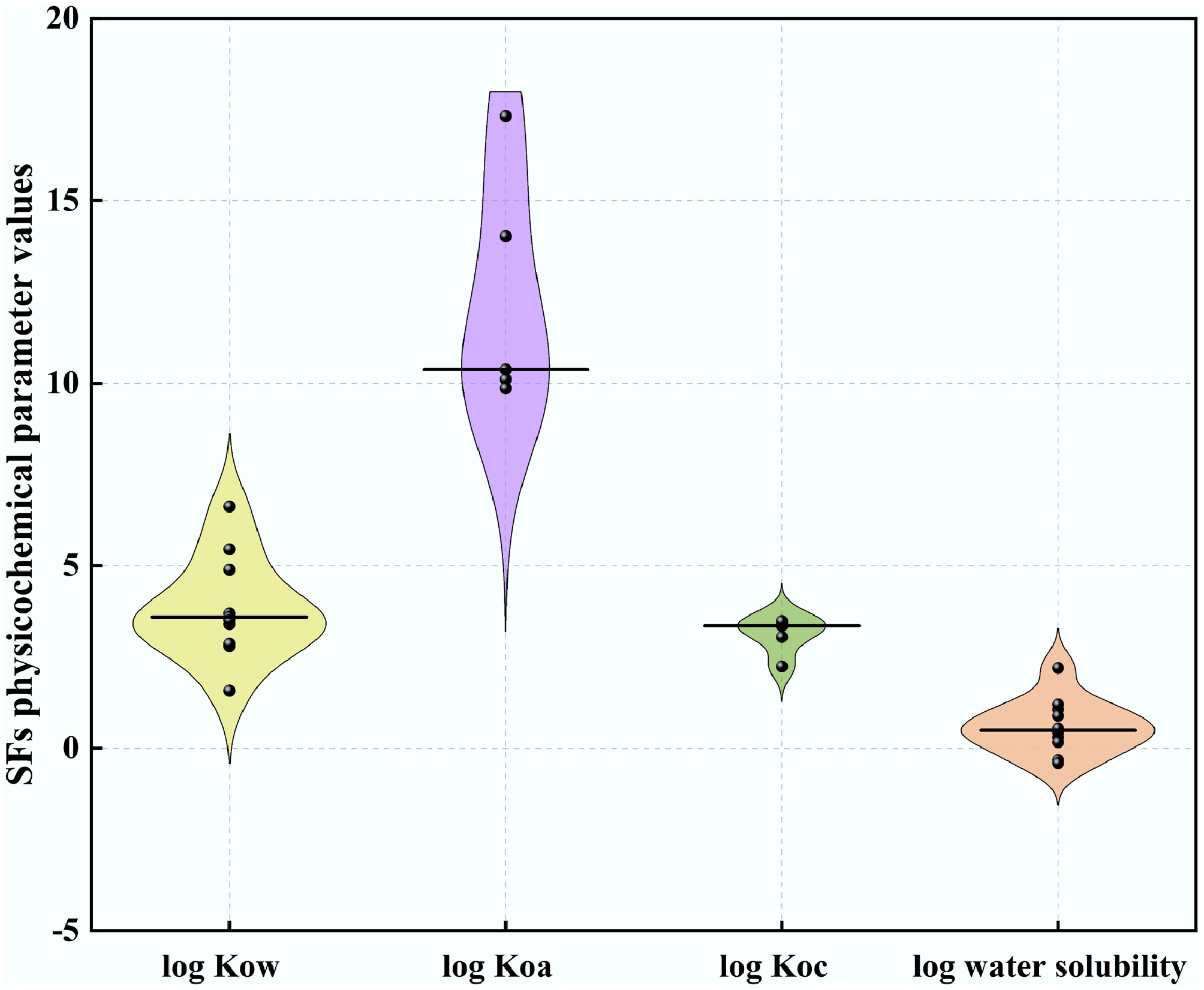

C22H18N2O4 131807-57-3 374.40 4.89 10.38 3.45 0.47 Most SFs demonstrate moderate to high hydrophilicity, with a median log octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) of 3.59 (Fig. 2). Although their water solubility varies significantly across groups (median log water solubility ranging from −0.41 to 1.06; Fig. 2), they are frequently detected in aquatic environments. Additionally, SFs generally exhibit moderate adsorption potential to organic carbon, with a median log organic carbon-water coefficient (Koc) of 3.35 (Fig. 2). These compounds tend to accumulate in environmental organic phases due to their low volatility, as indicated by a high log octanol-air partition coefficient (Koa) of 10.38 (Fig. 2). Notably, when log Koa > 8 and log Kow > 5, compounds exhibit low water solubility and are more likely to adsorb to particulate matter in both the atmosphere and water bodies[14], TRI and PYR meet these criteria (Table 1), suggesting their potential for higher concentrations and detection frequencies in atmospheric and aquatic particulate matter. For most aquatic organisms, compounds with 5 < log Kow < 8 exhibit strong bioaccumulation potential[15], TRI and PYR are likely to demonstrate significant bioaccumulation, whereas compounds with log Kow<5, such as AZO, KM, metaminostrobin (METO), fenamidone (FE), FLUO, PICO, dimoxystrobin (DIMO), and mandestrobin (MAND), exhibit higher hydrophilicity and reduced partitioning into lipid tissues, resulting in lower bioaccumulation potential (Table 1). In contrast to aquatic organisms, compounds with 2 < log Kow < 5 and log Koa > 6 can still achieve bioaccumulation in atmospheric media through respiratory uptake[15], and METO and femoxadone (FA) may utilize this pathway for accumulation.

Figure 2.

Violin plots of physico-chemical properties related to mobility and dissipation for strobilurins fungicides currently registered for use in the EU (log Kow: n = 11, log Koa: n = 5, log Koc: n = 5, log water solubility (20 °C): n = 5). Black bars within violins represent medians.

Analytical method

-

SFs were initially introduced for agricultural use, but their widespread application has led to the detection of SF residues in both environmental and biological systems. While early concerns focused on residues in agricultural soils and crops, recent attention has shifted to the potential toxicity of SFs to aquatic ecosystems and human health[16]. This review synthesizes the literature on the occurrence of SFs, with agricultural products such as crops, beans, fruits, vegetables, and grape wine being the most commonly analyzed for SF concentrations. Environmental monitoring has primarily targeted soil, surface water, and indoor/outdoor dust, while human and biological sample analyses are increasingly being developed (Table 2).

For the analysis of SFs residues in foodstuffs, including fruits and vegetables, the QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method is widely employed as a pretreatment technique, typically using acetonitrile (ACN) as the extraction solvent[17−24]. Additional sample preparation methods, such as liquid-liquid microextraction (LLME) and solid-phase extraction (SPE), have also been utilized, with various organic solvents tailored to specific sample types. In environmental matrices, a magnetic SPE extraction method coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) has been developed for detecting AZO, orysastrobin (ORY), PICO, DIMO, and KM in lake and tap water. This method has been demonstrated to be simple, time-efficient, and highly sensitive[25]. Research on SFs residue analysis in biological samples remains limited, with pretreatment methods largely mirroring those used for environmental and agricultural samples[26−30].

Instrumental analysis of SFs has predominantly relied on liquid chromatography (LC) and gas chromatography (GC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). In 2007, Flores et al. pioneered the determination of AZO residues in grapes, must, and wine using a multicommuted flow injection-solid phase spectroscopy (FI-SPS) system combined with photochemically induced fluorescence (PIF)[31]. Guo et al. advanced the field by developing a nonaqueous micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography method with indirect laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), offering advantages such as low solvent consumption, rapid analysis, and high separation efficiency. This method achieved limits of quantification (LOQs) of 0.001 mg·kg–1 for AZO, KM, and PYR, significantly lower than those obtained by traditional HPLC-MS or GC-MS[32]. Additionally, fluorescence polarization immunoassays (FPIAs) based on monoclonal antibodies have been optimized for the detection of SFs in vegetables and fruits, providing a sensitive and specific analytical approach[33].

Table 2. Extraction, purification, and analytical methods of strobilurin fungicides

Matrix Target SFs Sample preparation Analytical technique Recovery (RSD) LOQ Ref. Vegetable, fruit, and food Bean AZO, KM, TRI, DIMO,

FLUO, PICO, PYRLLME (ACN/H2O 9:1b) HPLC/UV-AD 61.6%–98.8% (< 10%) 0.004–0.005 mg·kg–1 [34] Rice ORY LLME (DCM/n-Hexane 20:80)

Florisil Column Chromatography (EA/DCM 10:90)HPLC-UV

LC-MS/MS83.9%–92.3%

80.6%–114.8%0.02 mg·kg–1

0.002 mg·kg–1[35] Apple, grape, wheat AZO, KM, TRI Extracted: EA/Cyclohexane

Clean-up: GPCGC-EC

GC-NP

GC-MS70%–114% −a [36] Pomegranate AZO, PYR d-SPE (ACN) LC-MS/MS 78.7%–98% (< 20%) 0.005 mg·kg–1 [17] Pepper PYR, PICO QuEChERS (ACN) UPLC-MS/MS 91%–107%

(3.7%–9.6%)0.12–0.61 μg·kg–1 [21] Watermelon FA LLextraction: DCM

Clean-up: Acetone/petroleum 1:9)HPLC-UVD 84.91%–99.41%

(0.06%–4.93%)− [37] Cucumber PYR QuEChERS UHPLC-MS/MS 89.8%–103.6%

(3.6%–7.5%)8.1 μg·kg–1 [18] Grape, must, wine AZO SPE (MeOH)

SPE (DCM)PIF-FI-SPS 84.0%–87.6%,

95.5%–105.9%,

88.5%–111.2%21 μg·kg–1

18 μg·L–1

8 μg·L–1[31] Jujube PYR, AZO QuEChERS (ACN) LC-MS/MS 87.5%–116.2%

(3.2%–14.7%)0.01–0.2 mg·kg–1 [24] Watermelon TRI QuEChERS (ACN) GC-MS/MS 78.59%–92.66% 0.01 mg·kg–1 [23] Apple tree bark PYR QuEChERS (ACN-Ammonia) HPLC-VWD 86.1%–101.4% 0.028–0.080 mg·kg–1 [20] Green bean, pea AZO LLME (ACN) HPLC-UV

GC-MS81.99%–107.85%

(< 20%)

76.29%–100.91%

(< 20%)0.1 mg·kg–1 [38] Banana AZO QuEChERS-Citrate (ACN) GC-SQ/MS − 0.022–0.199 mg·kg–1 [19] Pomegranate AZO, PYR QuEChERS (ACN);

d-SPE (n-Hexane /acetone 9:1)LC-MS/MS

GC-MS78.7%–98% (< 20%) 0.005 mg·kg–1

0.01 mg·kg–1[17] Water, juice, wine, vinegar PICO, PYR, TRI d-LLME (DES: thymol, octanoic acid) HPLC 77.4%–106.9%

(0.2%–6.8%)− [39] Rice TRI Extraction solvent (ACN) LC-MS/MS 74.3%–103.0% (0.5%–6.8%%) − [40] Cereal AZO, PYR,

TRId-LLME-SFOD (Nonanoic acid) HPLC-MS/MS 82.0%–93.2%

(1.6%–7.4%)− [41] Apple, citrus, cucumber, potato, tomato AZO,

KM,

PYR− Electrokinetic capillary chromatography 81.7%–96.1%

86.5%–95.7%

87.3%–97.4%0.005–2.5 mg·kg–1 [32] Tea TRI QuEChERS GC-MS 80.7%–105.8% (<9.3%) 0.05 mg·kg–1 [22] Red wine TRI, KM,

PICOCross-linked poly as a sorbent FPIAs-monoclonal antibodies 80%–104% (<12%) − [33] Cotton seed TRI, PICO,

KM, AZOd-LLME (ACN) GC-ECD 87.7%–95.2%

(4.1%–8.5%)− [42] Grape wine AZO, KM, TRI, PYR, FA, FE LLME (EA/n-Hexane 50:50) LC-ADA

GC-MS95.5% ± 5%

104% ± 6%0.3–0.6 mg·L–1

0.4–0.8 mg·L–1[43] Environmental media Lake, river, tap water AZO, ORY, PICO,

DIMO, KMMagnetic SPE HPLC-MS/MS 80.8%–109% 0.18–0.24 mg·L–1 [25] Soil, water, FA SPE (ACN) UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS 70%–120% (< 20%) 0.1 mg·kg–1

1 μg·L–1[44] Atmosphere AZO,

DIMO,

FLUO,

KM,

PYR,

TRI− LC-MS/MS 91.6% ± 12.2%

99.9% ± 5.6%

100.8% ± 10.4%

101.2% ± 0.2%

99.9% ± 0.7%

97.7% ± 6.3%− [45] Biological Sample Fish gill, blood, liver, muscle, PYR Mixtures of PSA, C18, MgSO4

QuEChERS-PC

Waters Oasis HLB SPEUPLC-MS/MS 112.5%–276.2%

(< 10%)

45.3%–259.7%

(< 10%)

86.94%–229.9%

(< 10%)0.002 mg·kg–1 [26] Human urine AZO, PYR d-LLME (Choline chloride / sesamol 1:3) HPLC-MS/MS 50%–101% 0.03–0.07 ng·mL–1 [28] Human urine AZO SPE (ACN) UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS 90%–103% 0.01 ng·mL–1 Human blood AZO, FA SPE (Dichloromethane /

methanol 9:1)GC-MS/MS 70%–120% (< 20%) < 1.45 ng·mL–1 [30] Indoor dust New dry wall, gypsum, house dust AZO,

PYR,

TRI,

FLUOExtracted: DACM/Hexane,1:1

Clean-up: ENVI-FlorisilLC-MS/MS 92%–96%

73%

36%

38%− [11] Indoor dust AZO, FLUO, TRI, PYR Extracted: ACN

Clean-up: ENVI-FlorisilUHPLC-MS/MS 91.2%–108% 0.005–0.01 ng·mL–1 [46] a: '–' indicates that the sample preparation method or recovery data were not recorded in the related literature. b: Extraction solvent ratio, indicated by the volume ratio. Abbreviation: d-LLME (Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction), d-SPE (Dispersive Solid Phase Extraction), GPC (Gel Permeation Chromatography), DES (Deep Eutectic Solvents), SFOD (Solidification floating organic droplets), ACN (Acetonitrile), DCM (Dichloromethane). Occurrence in foodstuffs and the environment

Foodstuffs

-

SFs are extensively utilized in agricultural practices, with residues reported in staple crops such as wheat, rice, cucumbers, apples, and grapes across regions including China, Brazil, the United States, and Europe (Table 3). Among these, AZO exhibits the highest detection frequency, likely attributable to its early commercialization and widespread adoption. Notably, the highest concentrations of AZO have been documented in wheat, whereas TRI shows the lowest levels. Research on SFs residues in foodstuffs predominantly appears in food science journals, focusing on the development and validation of analytical methods, as well as the assessment of environmental residue concentrations.

Environment

-

Owing to their broad application in crop disease management, SFs residues were initially reported in agricultural soils, followed by detections in surface water, drinking water, sediments, and indoor dust (Table 3). Compounds such as AZO, FLUO, PYR, and TRI are frequently detected across environmental matrices, demonstrating seasonal fluctuations characterized by elevated concentrations in summer and reduced levels in winter. This pattern aligns with agricultural application cycles, where fungicide use peaks during warmer months. Furthermore, SF concentrations in soils and sediments typically exceed those in aquatic systems, a phenomenon driven by their moderate adsorption potential to organic carbon (median log Koc for SFs: 3.35), which promotes hydrophobic partitioning into organic-rich environmental phases[25, 47−50].

Table 3. Concentrations of strobilurin fungicides in foodstuffs and environmental media

Matrix Target SFs Concentration Region Ref. Foodstuff Wheat PYR 0.08–9.91 mg·kg–1 China [51] Ginseng root, Ginseng stem and leaf AZO 0.343–9.40 mg·kg–1 China [52] Pepper PYR 1.68–3.27 mg·kg–1 China [21] PICO 2.79–2.80 mg·kg–1 Coffee bean AZO < 1.43 μg·kg–1 Brazil [34] DIMO < 1.46 μg·kg–1 KM < 1.48 μg·kg–1 PICO < 1.33 μg·kg–1 TRI < 1.54 μg·kg–1 Watermelon leaf Fa 19.695 mg·kg–1 China [37] Banana AZ 0.05–2.0 mg·kg–1 Brazil [19] Corn AZO 0.01–0.024 mg·kg–1 China [53] TRI < LOQ PYR 0.013–0.065 mg·kg–1 Apple PYR 0.01–0.070 mg·kg–1 China [54] Dried grape PYR 0.01–0.024 mg·kg–1 Turkey [55] Dried apricot TRI 0.01–0.162 mg·kg–1 Environment Soil AZO 0.726 mg·kg–1 China [52] Soil AZO 8.9–15.7 μg·kg–1 Vietnam [56] Sediment 5.5–35.0 μg·kg–1 Drinking water AZO 0.37–3.66 ng·L–1 China [50] FLUO < MDL ~0.011 ng·L–1 PYR 0.01–0.25 ng·L–1 TRI 0.07–1.03 ng·L–1 Suspended solid AZO 0.02–0.01 ng·L–1 China [50] FLUO < MDL PYR 0.04–0.48 ng·L–1 TRI < MDL ~ 0.007 ng·L–1 Drinking water AZO 0.036–2.41 μg·L–1 Vietnam [57] TRI 0.003–0.56 μg·L–1 Stream AZO 0.008–1.13 μg·L–1 the United States [58] PYR 0.006–0.054 μg·L–1 Groundwater AZO 0.2–0.9 ng·L–1 the United States [49] PYR 0.1–4.8 ng·L–1 Surface water AZO 30.6–59.8 ng·L–1 the United States [49] PYR 15.2–239 ng·L–1 Surface water AZO 0.01–47.3 ng·L–1 China [59] FLUO < MDL ~0.10 ng·L–1 PYR 0.01–0.52 ng·L–1 TRI < MDL ~0.21 ng·L–1 Indoor dust AZO < MDL ~21.9 ng·g–1 China [46] FLUO < MDL ~1.91 ng·g–1 PYR < MDL ~1,946 ng·g–1 TRI < MDL ~9.52 ng·g–1 Human biomonitoring

-

Concerns regarding the potential health risks of SFs to humans have grown in recent years. However, research on SF residues in human matrices remains limited, with only a small number of studies reporting detectable concentrations to date.

Widespread exposure in sensitive populations

-

Jamin et al. pioneered the identification of AZO metabolites in urine samples from 3,421 pregnant women in France[60]. In 2010, AZO and FA were detected in blood samples from pregnant women in China, with mean concentrations (detection rates) of 0.08 ng·mL–1 (3%) and 0.27 ng·mL–1 (23%), respectively[30]. Hu et al. reported AZO exposure (measured as AZ-acid) in 100% of urine samples from pregnant women and 70% of samples from children, with median levels of 0.10 and 0.07 ng·mL–1, respectively. The average estimated daily intake (EDI) was 75.6 ng·kg–1·d–1 for pregnant women, and 112.6 ng·kg–1·d–1 for children[29].

Limited detection in healthy volunteers

-

Gallo et al. analyzed urine samples from 10 healthy volunteers, detecting AZO (0.03 µg·g–1 creatinine), and PYR (0.03 µg·g–1 creatinine) in only one individual[28].

-

SFs function by inhibiting ATP synthesis and disrupting fungal energy metabolism. However, growing evidence highlights their unintended mitochondrial toxicity in non-target aquatic organisms. Mitochondrial dysfunction is typically quantified through oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements, including basal respiration, oligomycin-sensitive ATP-linked respiration, FCCP-uncoupled maximal respiration, and non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption[61].

Mitochondrial respiration inhibition

-

In zebrafish embryos, Yang et al. demonstrated that lethal concentrations of PYR (486 μg·L–1), TRI (403 μg·L–1), and AZO (408 μg·L–1) reduced OCR by 98.5%, 73.1%, and 28.7%, respectively, indicating potent suppression of both mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial respiration[62]. Even sublethal PYR exposure (100 μg·L–1) significantly diminished basal respiration and non-mitochondrial OCR in embryos[9].

Impairment of mitochondrial complexes and energy metabolism

-

Exposure to 10–20 µg·L–1 AZO or PYR in zebrafish larvae markedly reduced activities of mitochondrial complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase) and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), coupled with diminished ATP content[63,64]. Cao et al. directly visualized mitochondrial ultrastructural damage, including membrane degradation, rupture, and swelling, in zebrafish liver tissues following 8-d AZO exposure (10 μg·L–1). Notably, larval zebrafish exhibited greater susceptibility to AZO-induced mitochondrial dysfunction than adults, accompanied by downregulated Cytb transcription[63].

Transcriptomic and histopathological effects

-

Transcriptomic profiling of zebrafish exposed to TRI, KM, AZO, or PYR during early developmental stages revealed significant perturbations in pathways associated with apoptosis, carcinogenesis, organelle membranes, and mitochondrial integrity[65]. In fish, gills serve as primary sites for pollutant uptake; acute PYR exposure (500 μg·L–1) induced severe histopathological lesions, mitochondrial dysfunction, energy depletion, and respiratory impairment in gill tissues[66].

Toxicity in algal systems

-

Liu et al.[67] demonstrated that KM, PYR, TRI, and PICO at environmentally relevant concentrations (10–50 μg·L–1) inhibited bc1 complex activity in Chlorella vulgaris, impairing photosynthetic efficiency. Comet assays further revealed DNA damage in algal cells, suggesting genotoxic risks posed by SFs in aquatic ecosystems[7].

Mammalian studies

-

AZO has been shown to dose-dependently inhibit cellular respiration by targeting the quinol oxidation (Qo) site of mitochondrial complex III in rat liver. Interestingly, AZO also demonstrated systemic benefits in regulating glucose and lipid homeostasis in high-fat diet-fed mice, suggesting a dual role in metabolic modulation[68].

Mitochondrial dysfunction and toxicity

-

Exposure to KM at concentrations below the Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) induced mitochondrial dysfunction in fibroblast-like renal Vero cells, characterized by elevated mitochondrial superoxide production and reduced mitochondrial transmembrane potential[69]. Similarly, Jang et al. investigated the effects of TRI on human skin keratinocytes (HaCaT cells) at the organelle level, revealing that mitochondrial damage and mitophagy contribute to keratinocyte toxicity. These findings suggest a potential mechanistic link between TRI exposure and the development of skin diseases (Table 4)[70].

Table 4. Human related toxicity studies of strobilurin fungicides

Target SFs Research content Conclusion Ref. PYR Investigated the toxicological risks of PYR toward HepG2 cells and the mechanisms of intoxication in vitro. PYR induced DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to excessive generation of intracellular ROS, which ultimately resulted in mitochondrial-mediated cell apoptosis and toxic effects on human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells. [81] PYR, TRI, FA, FE Identified transcriptomic signatures shared with neurological disorders by exposing mouse cortical neuron-enriched cultures to PYR, TRI, FA, and FE. PYR, TRI, FA, and FE induced transcriptional changes in vitro. By inhibiting mitochondrial complex III, and they upregulated Nrf2-targeted antioxidant response genes and Rest. These changes are associated with human brain aging and neurodegeneration. [79] TRI Explored the mechanism of TRI-mediated mitophagy in human skin keratinocytes exposed to TRI. Mitochondrial damage and mitophagy likely contribute to TRI-induced toxicity in human keratinocytes, suggesting a potential mechanism for cutaneous diseases developed upon exposure. [70] AZO Explored the effects of AZO on human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma KYSE-150 cells and investigated the underlying mechanisms. AZO effectively induced apoptosis in esophageal cancer cells via mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic pathways. [72] PYR Using a multi-analytical approach that integrates toxicological database mining, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, and molecular docking, we studied the molecular mechanisms of PYR toxicity. PYR exposure was significantly associated with pathways related to prostate cancer and renal dysfunction, indicating its potential role as an inducer of these diseases. [82] Anticancer potential of AZO

-

Beyond its environmental and toxicological implications, AZO has shown promise as a potential chemotherapeutic agent. Studies have demonstrated that AZO induces apoptosis in cancer cells, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (KYSE-150)[71,72], and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2)[68,73], through activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. This highlights the potential for repurposing AZO as a therapeutic agent in oncology.

Oxidative stress

-

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that exposure to SFs can induce oxidative stress in biological organisms. PYR has been shown to disrupt oxidative balance in earthworms, primarily characterized by a dose-dependent increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. This elevation in ROS can impair the antioxidant defense system, ultimately leading to DNA damage[74]. Similarly, TRI, AZO, and KM have been reported to alter antioxidant enzyme activities, including increased catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) activities and decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. These changes weaken the oxidative defense system and exacerbate oxidative stress, resulting in developmental impairments. Additionally, exposure to these SFs downregulated the expression of growth-related genes such as IGF-1, IGF-2, and GHR, leading to abnormal growth and developmental malformations[67]. Cao et al. investigated the effects of AZO exposure on maternal zebrafish and their offspring, revealing that maternal toxicity influenced the expression of oxidative stress-related genes in embryos. Furthermore, offspring exposed to the same environment exhibited more severe oxidative stress responses, highlighting the potential for transgenerational impacts of SFs on aquatic organisms[75].

Endocrine-disrupting toxicity

-

SFs, including TRI, KM, PYR, and AZO, have demonstrated significant detrimental effects on the development and reproduction of aquatic species such as medaka, D. magna, and zebrafish. These substances act as potential endocrine disruptors and induce various developmental malformations.

Reproductive effects

-

Exposure to TRI disrupts the sex hormone pathway and xenobiotic metabolism in medaka, significantly up-regulating the mRNA levels of the er gene at concentrations above 1 μg·L–1. This disruption adversely affects embryonic and larval development[76]. The reproduction of D. magna is significantly affected by the three SFs (KM, PYR, and TRI). Increased concentrations of these fungicides result in reduced brood numbers per female and decreased fecundity, with females showing particularly high sensitivity[77].

Transcriptomic alterations

-

Exposure to SFs results in the up-regulation of genes related to apoptosis, disease infection, and cancer pathways[65].

Lethal and teratogenic effects

-

Although high concentrations of TFS, KM, AZO, and PYR do not cause embryonic mortality in zebrafish, they lead to developmental issues such as reduced hatching rates, pericardial edema, decreased heart rates, and impaired metabolic cycles[6,8,16,67]. According to Wu et al., exposure to PYR, TRI, and AZO induces lethal and teratogenic effects, with affected embryos exhibiting microcephaly, hypopigmentation, somite segmentation, and narrow fins. These effects are consistent across single and combined exposures, displaying a strong synergistic interaction that enhances malformation rates in a concentration-dependent manner[78].

Neurotoxicity

-

Few studies were focused on the neurotoxicity of SFs, but certain evidence proved that PYR, TRI, FA, and FE might induce transcriptional changes in vitro, which were similar to those seen in brain samples from humans with autism, Alzheimer's disease, and Huntington's disease (Table 4)[79]. In primary cultured mouse cortical neurons, KM and PYR were found to be highly neurotoxic, with LC50 in the low micromolar and nanomolar levels, respectively[80]. Further study showed that they could cause a rapid rise in intracellular calcium and strong depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential. KM- and PYR-induced cell death was reversed by the calcium channel blockers MK-801 and verapamil, suggesting that calcium entry through NMDA receptors and voltage-operated calcium channels are involved in KM- and PYR-induced neurotoxicity. Studies in mice revealed that AZO transferred from the mother to the offspring during gestation by crossing the placenta and entered the developing brain, and high levels of cytotoxicity were observed in embryonic mouse cortical neurons[29].

-

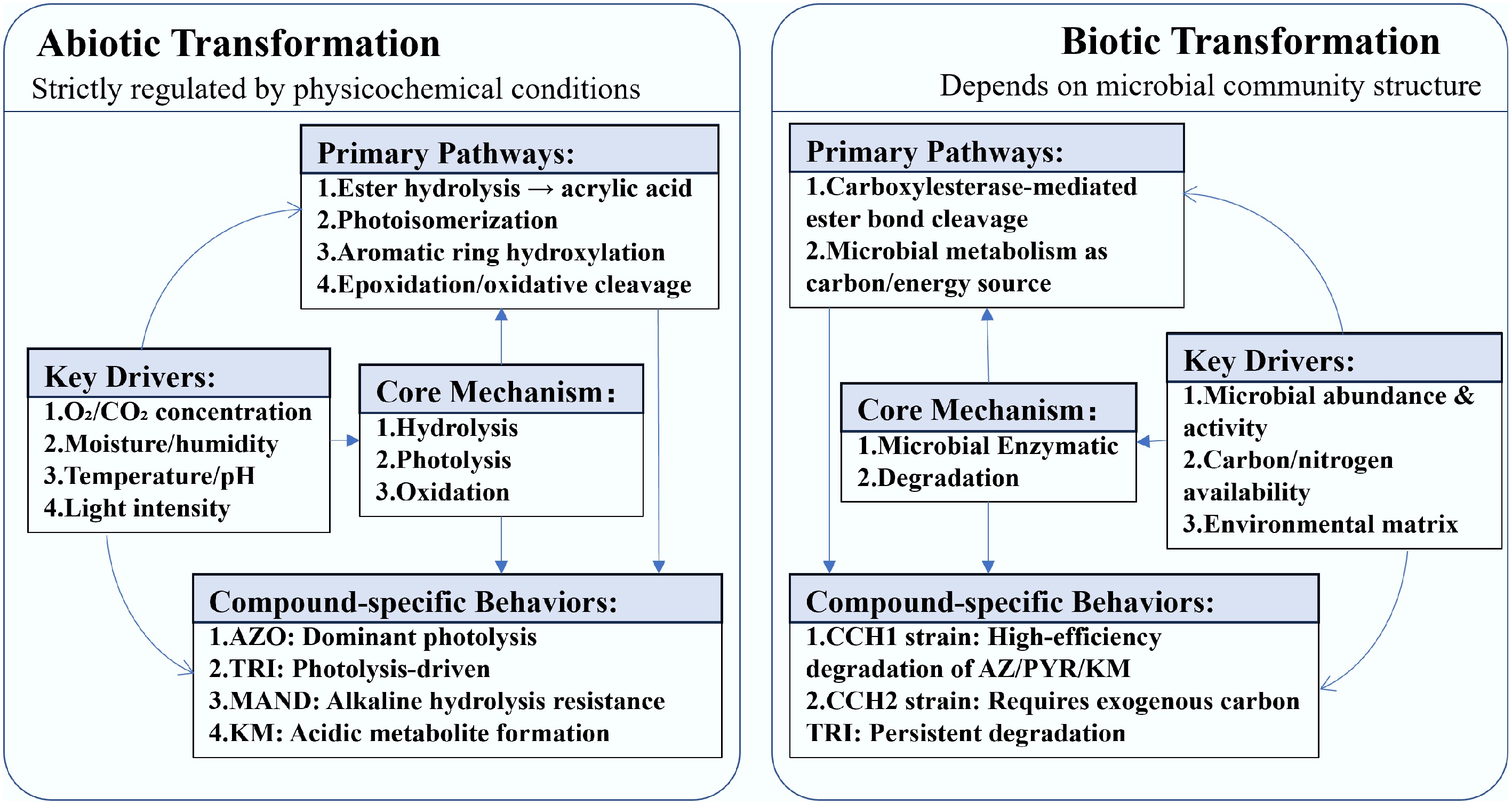

The primary pathways, core mechanism, compound-specific behaviors and key drivers for both abiotic and biotic transformation of the SFs are illustrated in Fig. 3. The detailed discussion is shown below.

Abiotic transformation

-

Abiotic transformation of SFs involves multiple metabolic pathways based on their molecular structure. These pathways include the formation of free acrylic acid through the hydrolysis of methyl esters, aromatic cyclohydroxylation, and conjugation with glutathione or other biological groups. Additionally, the double bonds in the acrylic moiety can undergo epoxidation, forming carboxyl groups or alcohols through the addition of hydrogen or water[83]. In aquatic environments, KM is particularly prone to forming acidic metabolites, influenced significantly by abiotic factors such as pH, temperature, light, and atmospheric CO2 levels[4]. Photoconversion of AZO is expected to occur through several parallel reaction pathways, including photoisomerization (E/Z), photohydrolysis of methyl and nitrile groups, cleavage of acrylate double bonds, and cleavage of photohydrolytic ethers between aromatic rings to yield phenols. Furthermore, oxidative cleavage of acrylate double bonds is also observed[83]. Under field conditions, photolysis is the primary degradation pathway for TRI, with the duration of sunlight exposure being a critical factor[84]. In contrast, PYR undergoes rapid transformation under conditions of humid air, with the organic matter content, microbial population, and soil moisture serving as the primary influencing factors[6]. Meanwhile, MAND, which features a unique methoxyacetamide functional group, exhibits resistance to alkaline hydrolysis, similar to mandestrobin, which also possesses this methoxyacetamide moiety and shows comparable resistance[85]. We further compared the half-lives of these SFs across different environmental matrices. In aquatic systems, MAND demonstrated the shortest photolytic half-life (1.2–3 d) under light exposure, followed by KM with an aqueous half-life of 5.2 d. AZO exhibited the longest persistence in water with a half-life of 15 d. For soil environments, TRI and PYR showed comparable photolysis half-lives of 8.8 and 9.2 d, respectively.

Biotransformation

-

Microbial degradation stands out as the primary biotransformation pathway for SFs, with specific soil microorganisms utilizing these chemicals as carbon sources. Notably, four species, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus flexus, and Arthrobacter oxydans, are known to metabolize TRI for carbon[86]. These species were isolated through a sequential soil and liquid culture enrichment technique. Additionally, two strains, Cupriavidus sp. CCH2 and Rhodanobacter sp. CCH1, have been isolated for their ability to use AZO as their exclusive carbon and nitrogen source, and they can also degrade TRI, PYR, and KM when additional carbon is available[87,88]. Significant differences in the degradation rates of SFs were observed between microbial strains. Specifically, CCH1 demonstrated universally higher degradation efficiency than CCH2 for three strobilurins—AZ (DT25: 2.0 d vs 2.2 d), PYR (2.3 d vs 2.8 d), and KM (2.6 d vs 2.9 d)—with the most pronounced disparity occurring in PYR degradation. Additionally, TRI exhibited the slowest degradation across both strains (identical DT25 of 4.2 d), markedly exceeding other SFs. Other studies have shown that HI2 and HI6 achieved a PYR degradation rate of 0.1 mg·(L·d)–1.

While SFs have a complex structure with numerous active sites, the underlying molecular mechanisms of their biodegradation are consistent across different species. Carboxyester hydrolysis by esterases is often the primary degradation mechanism in the microbial-guided biotransformation of strobilurins. This enzymatic process effectively cleaves the ester bonds within the molecules, initiating degradation and enabling further metabolic transformations[12,88,89].

-

The widespread presence of SFs in environmental media, foodstuffs, and human populations suggests a large-scale and potentially global contamination trend. Human exposure to SFs occurs through various pathways that have been established for other pesticides, including oral ingestion, dermal absorption, hand-to-mouth transfer, and additional mechanisms. To date, human biomonitoring studies remain limited, and Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) values are generally lacking for SFs. Available research indicates that SFs exhibit toxicity not only to aquatic species but also to mammals, including humans. However, the existing data are insufficient for a comprehensive assessment of human exposure routes and associated risks for SFs. Further research is necessary across multiple domains, including environmental monitoring, toxicological effects, biomonitoring, and human exposure assessments. Knowledge gaps have been identified and prioritized to the best of our current understanding to guide future research endeavors.

Enhancing environmental monitoring and exposure assessment

-

Despite the widespread use of SFs, critical gaps persist in characterizing their environmental distribution. Comprehensive monitoring across matrices such as air, indoor/outdoor dust, drinking water, and consumer products remains limited. Large-scale regional and global studies are urgently needed to establish baseline concentrations and evaluate the spatial-temporal dynamics of these emerging contaminants. Concurrently, exposure pathways—including dietary and non-dietary routes—must be systematically quantified, particularly for sensitive populations (e.g., children, pregnant women). Advanced analytical frameworks integrating source tracking, fate modeling, and biomonitoring are essential to refine risk assessments and inform regulatory policies.

Advancing mechanistic toxicity studies

-

While mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as a primary toxicity endpoint for SFs in mammals, the molecular mechanisms driving these effects remain poorly understood. Current research disproportionately focuses on mitochondrial endpoints, neglecting potential interactions with other cellular pathways (e.g., epigenetic regulation, immune disruption). Cutting-edge omics technologies (e.g., transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics) should be prioritized to unravel systemic toxicity profiles and identify novel biomarkers of effect. Furthermore, investigations into mixture toxicity and cumulative effects are critical, given the co-occurrence of SFs with other agrochemicals in environmental matrices.

Expanding epidemiological evidence

-

Epidemiological data linking SFs exposure to human health outcomes are strikingly scarce. Robust cohort studies incorporating biomonitoring (e.g., urine, blood SF metabolites) and longitudinal health assessments are imperative to evaluate associations with chronic diseases, developmental anomalies, and endocrine disorders. Special attention should be directed toward agricultural communities and regions with intensive SF usage, where exposure levels are likely elevated. Harmonized methodologies for exposure quantification and outcome measurement are needed to ensure comparability across studies.

Leveraging predictive effect modeling

-

Empirical testing of SF toxicity across all ecologically relevant species—particularly under realistic exposure scenarios involving mixtures and environmental stressors—is logistically unfeasible. Effect modeling offers a transformative alternative:

Toxicokinetic-Toxicodynamic (TK-TD) Models: proven frameworks for predicting time-dependent toxicity under variable exposure regimes[90,91], such as those based on acute mortality data, should be expanded to sublethal endpoints (e.g., growth inhibition, reproductive impairment).

Quantitative Structure-Toxicity Relationship (QSTR) Models: existing multi-species QSTR models, which accurately predict SFs toxicity across 20 indicator species (invertebrates and vertebrates), warrant validation in field conditions and extension to underrepresented taxa[92,93].

Mixture Toxicity Modeling: integrate chemical interaction algorithms (e.g., concentration addition, independent action) to assess cumulative risks of SFs co-exposures[90].

-

study conception and design, authorship team assembling, writing − draft manuscript preparation: Xue J, Liu Z, Liu Y; metadata compiling and analysis: Liu Z, Liu Y; writing − manuscript editing: Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhang T, Cai Y. All authors commented on the draft and gave final consent for publication.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the Basic Science Center Project of the Natural Science Foundation of China (52388101), the Program for Guangdong Introducing Innovative and Entrepreneurial Teams (2019ZT08L213), the Natural Science Foundation of China (42377376), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory Project (2023B1212060068), and the R & D program of Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2024B1212040004).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

-

SF residues are ubiquitous in crops, aquatic systems, and humans, indicating widespread exposure and risks.

Mitochondrial dysfunction underpins SF toxicity: inhibiting complex III, reducing ATP 28.7%–98.5%, and inducing ROS in zebrafish.

At environmental levels, SFs trigger endocrine and neurotoxicity, indicating low-dose risks.

Microbial degradation dominates SF transformation, offering novel remediation insights.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhilei Liu, Yuxian Liu

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Z, Liu Y, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhang T, et al. 2025. A brief review of strobilurin fungicides: environmental exposure, transformation, and toxicity. New Contaminants 1: e004 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0002

A brief review of strobilurin fungicides: environmental exposure, transformation, and toxicity

- Received: 15 June 2025

- Revised: 16 July 2025

- Accepted: 06 August 2025

- Published online: 03 September 2025

Abstract: Strobilurin fungicides (SFs), a class of quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) agrochemicals, have revolutionized crop protection since their commercialization in the 1990s. This critical review synthesizes global data on environmental distribution, analytical detection methods, toxicological impacts, and environmental transformation of SF. Key findings revealed: (1) SFs residues are ubiquitously detected in agricultural products (e.g., wheat, apples), aquatic systems (median concentration up to 100 μg·L–1), and human matrices (e.g., 100% detection of azoxystrobin metabolites in pregnant women's urine); (2) mitochondrial dysfunction emerges as a central toxicity mechanism, with SFs inhibiting complex III activity, reducing ATP synthesis by 28.7%–98.5% in zebrafish embryos, and inducing oxidative stress via ROS overproduction; (3) endocrine disruption and neurotoxic effects were observed at environmentally relevant concentrations (e.g., 1 μg·L–1 trifloxystrobin altered er gene expression in medaka); (4) microbial degradation dominated the environmental transformation, showing exceptional catabolic versatility. Despite advancements, critical gaps persist in mixture toxicity assessment, epidemiological correlation, and global biomonitoring. We advocate for integrated approaches combining effect modeling (QSTR/TK-TD), omics technologies, and international surveillance networks to mitigate ecological and health risks in the era of intensifying agrochemical use.

-

Key words:

- Strobilurin fungicides /

- Environmental exposure /

- Toxicology effect /

- Transformation