-

The phytohormone, auxin, is fundamentally involved in regulating diverse physiological processes ranging from plant growth to stress acclimation[1,2]. Extensive studies have demonstrated that indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) serves as the major endogenous auxin in plants, accompanied by less abundant forms including phenylacetic acid (PAA) and 4-chloro-indole-3-acetic acid (4-Cl-IAA)[1]. In plants, the homeostasis of IAA is precisely regulated through its biosynthesis, transport, conjugation, and degradation pathways[2−4]. The physiological functions of auxin depend critically on its signal perception and transduction systems, which primarily involve two distinct receptor systems localized in different subcellular compartments: the ABP1/ABLs-TMK (Auxin-Binding Protein 1/ABP1-Like proteins- Transmembrane Kinases) co-receptor complex located at the plasma membrane, and the nuclear-localized TIR1/AFB (Transport Inhibitor Response 1/ Auxin signalling F-Box protein) receptor family[5−7]. The binding of IAA to the ABP1/ABLs-TMK co-receptor triggers an ultrafast auxin phosphorylation response, which mediates rapid auxin signaling[8]. In contrast, IAA binding to TIR1/AFB receptors activates the canonical SCF (Skp1-Cullin1-F-box)TIR1/AFBs-Aux/IAA (Auxin/Indole-3-Acetic Acid)-ARF (Auxin Response Factor) signaling cascade that mediates transcriptional reprogramming, which is considered the central molecular mechanism underlying most of auxin's physiological regulatory functions[9,10].

Notably, although the SCFTIR1/AFBs-Aux/IAA-ARF signaling pathway has been extensively studied, the recent breakthrough discoveries have revealed that TIR1/AFB receptors possess AC activity capable of catalyzing the production of the second messenger cAMP to participate in transcriptional regulation[11,12]. This discovery opens new avenues for exploring the complexities of auxin signaling.

This review systematically examined the discovery of TIR1/AFB's AC enzymatic activity, provides an in-depth discussion of the molecular mechanisms of cAMP-mediated auxin signal transduction and its crosstalk with other hormonal signaling pathways, and offers prospective insights into unresolved key scientific questions regarding the TIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA-cAMP-ARF transcriptional signaling module.

-

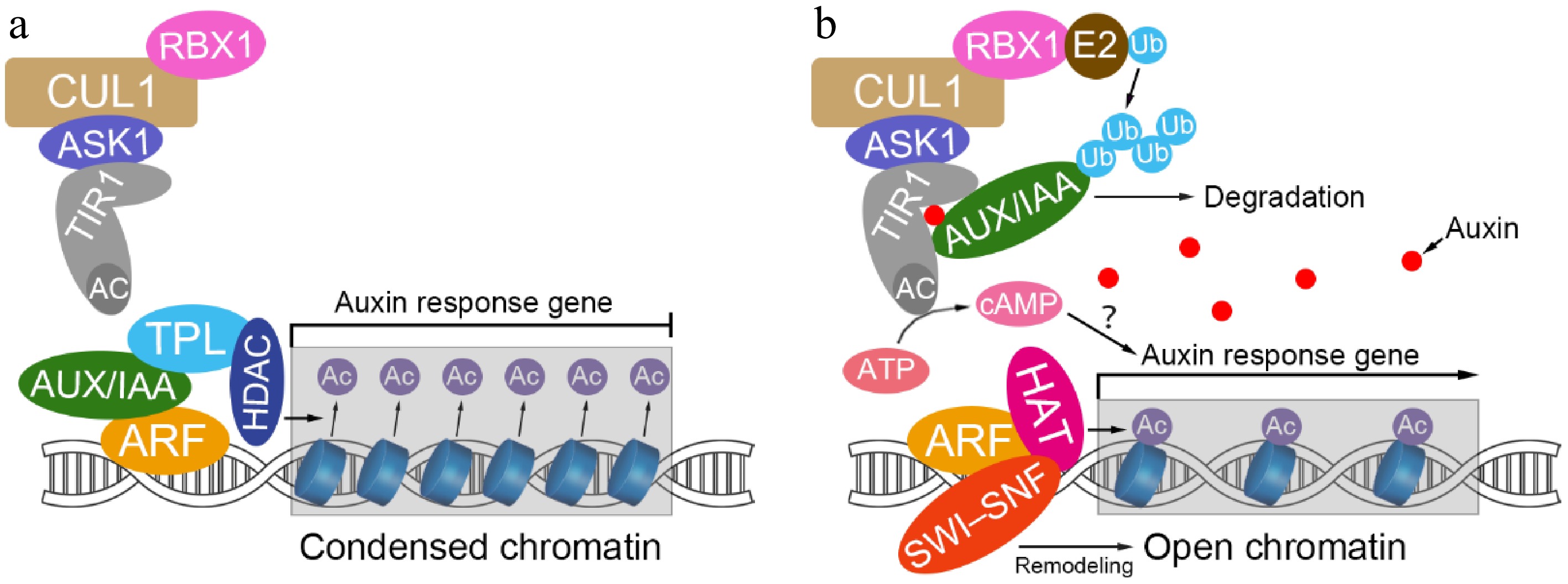

The canonical nuclear auxin signaling pathway consists of three core components: the receptors TIR1/AFBs, transcriptional repressors Aux/IAAs, and transcription factors ARFs[10,13]. Under low auxin concentrations, Aux/IAAs interact with ARFs to suppress their transcriptional activity. When auxin levels increase, auxin acts as a 'molecular glue' that simultaneously binds to both TIR1/AFB receptors and Aux/IAA repressors, facilitating the formation of the SCFTIR1/AFB-auxin-Aux/IAA ternary complex. This leads to ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Aux/IAAs, thereby releasing ARFs to activate or repress the transcription of auxin-responsive genes (Fig. 1)[6,13,14].

Figure 1.

Nuclear auxin signaling pathway and auxin-dependent regulation of gene expression. (a) Aux/IAA repressors bind to ARF transcription factors at low cellular auxin levels. Aux/IAA recruit TPL-HDA19, which maintains condensed chromatin by histone deacetylation. This interaction prevents ARF from driving gene transcription. (b) At high cellular auxin concentrations, the hormone is perceived by the SCFTIR1- Aux/IAA co-receptor complex, followed by degradation of Aux/IAA and cAMP production. ARFs recruit chromatin-remodeling complexes containing SWI-SNF, histone acetylases, and other regulatory factors. This process promotes chromatin opening and further activates the transcription of auxin response genes. RBX1, RING-BOX 1; CUL1, CULLIN 1; ASK1, ARABIDOPSIS SKP1 HOMOLOG; TIR1, TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESISTANT1; AC, adenylate cyclase activity of TIR1; Aux/IAA, AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID; ARF, AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR; TPL, TOPLESS; HDAC, HISTONE DEACETYLASE; Ac, acetyl group; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; Ub, ubiquitin; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; HAT, HISTONE ACETYLASE; SWI-SNF, SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complex. The blue cylinders represent histone-constituted nucleosomes.

The typical Aux/IAA protein contains four conserved domains (I–IV) and is localized in the nucleus[15,16]. Domain I serves as a repression domain featuring characteristic 'LxLxL' or '(L/F)DLN(L/F)xP; motifs that specifically recruit the corepressors TPL (TOPLESS)/TPL-related proteins (TPR1−TPR4)[17]. TPL/TPRs recruit histone deacetylases to suppress ARF target gene expression by inducing chromatin condensation[18]. Domain II contains a highly conserved 'GWPPV' motif that mediates interaction with SCFTIR1/AFB to regulate Aux/IAA degradation[19]. Domains III and IV together form the PB1 (Phox and Bem1) domain, where Domain III contains a crucial βαα-fold structure responsible for homo- or heterodimerization (Aux/IAA-Aux/IAA or Aux/IAA-ARF), while Domain IV participates in electrostatic protein interactions through a conserved 'GDVP' motif[20]. Additionally, both Domain II and IV contain nuclear localization signals (NLS) that ensure nuclear targeting[15].

As auxin concentrations rise and Aux/IAAs are degraded, the chromatin repression mediated by TPL/TPR-HDAC (Histone Deacetylase) complexes is relieved. The released ARFs recruit SWI/SNF (Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermenting) chromatin remodeling complexes to activate transcription by altering chromatin structure[21]. Subsequently, ARFs specifically recognize and bind to auxin response elements (AuxREs) in target gene promoters through their DNA-binding domains (DBD) to regulate gene expression (Fig. 1)[22]. Similar to Aux/IAAs, ARF proteins also contain four characteristic domains: Domain I (DBD) for DNA binding; Domain II, determining transcriptional regulatory properties (activation-type ARFs are glutamine-rich while repression-type are serine/threonine/proline-rich); and Domains III−IV (PB1 domain) mediating protein dimerization[13,22]. Strikingly, among the 23 ARF members in Arabidopsis, only five (AtARF5/6/7/8/19) function as transcriptional activators, with the remainder characterized as repressors[22]. Genetic and biochemical evidence reveal that the Aux/IAA-ARF module primarily regulates activator ARFs, while repressor ARFs have evolved distinct regulatory pathways[13,23]. Specifically, ARF activators are dually controlled by: (i) auxin-dependent degradation of Aux/IAA proteins, and (ii) constitutive suppression by repressor ARFs. Although auxin signaling relieves Aux/IAA-mediated inhibition of activator ARFs, repressor ARFs can still modulate transcriptional activation through two autonomous mechanisms: (i) direct recruitment of TPL/TPRs corepressor complexes (e.g., ARF2/3/9/18) to suppress target gene expression[13,24,25], or (ii) competitive DNA binding or formation of functional heterodimers to constrain the transcriptional potential of activator ARFs (e.g., ARF9)[23]. This sophisticated regulatory network, featuring Aux/IAA-ARF module-dominated control of activator ARFs coupled with the dual repression mechanisms independently evolved in repressor ARFs, constitutes the core framework of auxin signaling transduction, ensuring spatiotemporal precision and plasticity in signal responses[13,23].

Moreover, recent studies have revealed that some atypical ARFs (e.g., Arabidopsis ARF3/ETTIN), which lack the PB1 domain, function independently of the canonical TIR1/AFB pathway[25]. Intriguingly, auxin can directly bind to ARF3, bypassing TIR1/AFB receptors, to modulate its interaction with the TOPLESS-HDA9 complex and thereby influence histone acetylation status during transcriptional reprogramming in plant developmental processes. This discovery suggests an alternative mechanism whereby auxin directly regulates gene transcription through non-canonical ARFs, significantly expanding our understanding of auxin-mediated transcriptional regulation.

-

Auxin-induced apoplastic alkalinization and cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients constitute a rapid and reversible mechanism for regulating primary root growth. Importantly, these rapid physiological responses are genetically positioned downstream of TIR1/AFB signaling, indicating that TIR1/AFB receptors may also participate in non-transcriptional pathways[26].

Building on this insight, the Friml research group conducted a comprehensive analysis of Arabidopsis TIR1/AFB protein sequences and identified a conserved AC motif in their C-terminal domains. Functional assays using heterologous expression systems (Escherichia coli and Sf9 insect cells) confirmed that TIR1, AFB1, and AFB5 possess AC activity that catalyzes the conversion of ATP to cAMP[24]. The resulting cAMP has been shown to activate cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs), modulating intracellular Ca2+ dynamics[27]. Although only three TIR1/AFB family members have been experimentally verified to possess AC activity, the widespread conservation of the AC motif suggests that this enzymatic function may be a general feature of the entire family. Strikingly, AC activity was also detected in a moss (Physcomitrella patens) AFB homolog, suggesting that this function evolved early during land plant evolution[24,11].

To further investigate the role of AC activity, the authors performed site-directed mutagenesis of conserved residues in TIR1 and AFB5, generating three mutant variants (ACm1, ACm2, and ACm3). ACm2 retained partial AC activity but lost its ability to interact with Aux/IAA proteins (e.g., IAA7), whereas ACm1 and ACm3 completely lacked AC activity. Notably, these two mutations did not impair the interaction of TIR1 with ASK1 (Arabidopsis SKP1 homolog 1), which serves as a critical bridge connecting F-box proteins with Cullin 1 in SCF complexes, nor did they disrupt Aux/IAA binding or ubiquitination (Fig. 1)[28]. These findings demonstrate that the AC activity of TIR1/AFBs is mechanistically separable from their canonical role in Aux/IAA degradation[11,12].

A key discovery was that auxin-induced interaction between TIR1 and Aux/IAA proteins significantly enhances TIR1's AC activity, and that normal Aux/IAA degradation is required for optimal cAMP production. Thus, TIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA interactions trigger two parallel processes: promotion of Aux/IAA ubiquitination and degradation, and stimulation of TIR1/AFB's AC activity.

Genetic complementation assays in the tir1-1 afb2-3 double mutant background further revealed functional consequences of impaired AC activity. Roots expressing the ACm2 variant exhibited near-complete insensitivity to IAA-mediated growth inhibition, while ACm1 and ACm3 showed only partial attenuation. These phenotypic differences underscore the essential role of TIR1's AC activity in auxin-regulated root growth, alongside its traditional function in Aux/IAA degradation[12].

Despite previous evidence linking TIR1/AFB signaling to rapid cellular responses such as apoplastic alkalinization and Ca2+ influx, this study demonstrated that the AC activity of TIR1/AFBs is not involved in these processes. Instead, transcriptomic analyses revealed that auxin-induced expression of classical response genes (e.g., GH3.3, GH3.5, IAA5, IAA19, and LBD29) was markedly reduced in ACm1 mutants[12]. This indicated that TIR1/AFB's AC activity contributes to transcriptional activation. However, residual gene expression suggests partial functionality of the canonical degradation pathway. In addition, the authors showed that TIR1's AC activity is required for multiple developmental processes regulated by auxin, including root gravitropism, lateral root formation, root hair elongation, and hypocotyl growth[11].

To determine whether Aux/IAA degradation is necessary for cAMP-mediated ARF activation, the authors designed a creative experiment in which the AC domains of KUP5 or LRRAC1 were fused to the auxin-resistant 3 (axr3) mutant (an allelic mutant carrying a point mutation in Domain II exhibits impaired binding capacity to TIR1/AFB while retaining ARF-binding capacity)[29]. Remarkably, these fusion constructs activated ARFs and downstream transcription without requiring TIR1/AFB interaction or Aux/IAA degradation. This suggests that localized cAMP production near ARFs may directly stimulate transcriptional activity, potentially bypassing traditional auxin perception and degradation routes, though a dynamic interplay between cAMP activation and Aux/IAA-mediated repression cannot yet be ruled out[11].

Together, these findings from the Friml group reveal a dual signaling mechanism downstream of auxin perception. Upon IAA binding and SCFTIR1/AFB complex formation, two parallel events unfold: (i) Aux/IAA proteins are ubiquitinated and degraded, releasing ARFs; and (ii) TIR1/AFB's AC activity is enhanced through interaction with Aux/IAAs, leading to localized cAMP production. The authors propose a model in which undegraded Aux/IAAs may guide cAMP enrichment near specific ARFs via protein-protein interactions, thus facilitating ARF activation. Subsequent degradation of Aux/IAAs then consolidates ARF activation, collectively orchestrating transcriptional responses such as GH3 and SAUR expression to regulate growth and development (Fig. 1)[11,12].

While the authors' study represents significant progress and provides novel insights into the role of TIR1/AFB signaling, one critical question remains insufficiently addressed in their conclusions. The authors employed KUP5 (K+ Uptake Permease 5) or LRRAC1 (Leucine-Rich Repeat protein 1)-AC domain fusions with axr3 and demonstrated that localized cAMP production near ARFs directly stimulates transcriptional activity[11]. However, they did not include essential control experiments to verify whether spatially restricted cAMP synthesis near ARFs is strictly required for this function. For instance, introducing a nuclear-localized protein fused to the AC domain could help determine whether cAMP-dependent transcriptional activation still occurs when cAMP production is not spatially constrained.

-

cAMP serves as a crucial secondary messenger in plants, establishing intricate interaction networks with various phytohormones, particularly stress hormones including abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA). Investigations have revealed a bidirectional regulatory relationship between cAMP and ABA: while ABA suppresses cAMP-induced seed germination, its inhibitory effect on stomatal opening can be completely reversed by the cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP[30,31]. Notably, exogenous ABA application induces cAMP accumulation under drought and heat stress conditions in maize ABA-deficient mutants[32]. Furthermore, cAMP significantly modulates SA levels through regulation of AC activity[33], whereas JA rapidly elevates intracellular cAMP concentrations[34].

Beyond stress hormones, cAMP demonstrates noteworthy interactions with IAA and gibberellins (GA3). Experimental evidence shows that low-concentration GA3 synergistically promotes seed germination with exogenous cAMP, while GA3 itself regulates cAMP levels during germination[31,35]. In auxin signaling, cAMP not only mimics IAA in activating tryptophan oxygenase synthesis but also forms a bidirectional regulatory loop with IAA-transient cAMP induction, which increases IAA content, which in turn stimulates cAMP production[36,37].

Overexpression studies of the soluble AC domain (AtKUP7 N-terminus) in Arabidopsis and rapeseed have demonstrated that elevated cAMP levels substantially altered hormonal homeostasis[38,39]. Transcriptome analyses indicate that cAMP-responsive genes are predominantly enriched in three biological processes: (1) hormone response and biosynthesis, (2) stress response (both abiotic and biotic), and (3) growth and development regulation[38,39]. Intriguingly, cAMP-induced hormonal changes exhibit remarkable species specificity: although consistently reducing ABA and SA levels, the effects on IAA and cytokinins (KT/cZ) differ significantly between Arabidopsis and rapeseed[38,39]. The observed differences likely reflect species-specific cAMP regulation of hormonal (notably auxin and cytokinin) metabolic pathways, including biosynthesis, conjugation, and transport. While auxin biosynthesis genes are predominantly suppressed in Arabidopsis, essential genes, e.g., Tryptophan Aminotransferase of Arabidopsis 1 (TAA1), Cytochrome P450 83B1 (CYP83B1), Tryptophan Synthase α subunit (TSA1), demonstrate significant induction in rapeseed, indicating transcriptional control of hormone metabolism by cAMP may vary across species[38,39]. Nevertheless, the fundamental mechanism, whether cAMP directly regulates gene transcription or indirectly perturbs hormonal signaling through cumulative effects, requires further experimental confirmation.

Based on current evidence, this study proposes that plants may employ two sophisticated mechanisms for precise cAMP signal modulation: (1) a feedback regulation mechanism where hormonal changes reciprocally regulate cAMP metabolism, and (2) a spatial localization mechanism achieved through AC enzyme incorporation into functional protein complexes, enabling spatiotemporal-specific activation. These coordinated mechanisms presumably underlie the crucial role of cAMP in integrating plant growth, development, and stress responses.

-

Additionally, several key questions warrant further investigation.

Mechanism of cAMP-mediated ARF activation

-

As a small diffusible molecule, cAMP is expected to rapidly disperse upon synthesis. How do plant cells maintain high local concentrations of cAMP in specific subcellular regions? One possibility is the formation of biomolecular condensates (e.g., phase-separated droplets), analogous to protein interaction hubs, which could transiently sequester cAMP and sustain its localized activity.

Regarding the mechanism by which cAMP activates ARFs, two plausible hypotheses were proposed: (1) the kinase cascade model, in which cAMP promotes ARF phosphorylation to alleviate Aux/IAA repression or enhance transcriptional activity, akin to PKA-mediated signaling in animals (cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation has been experimentally confirmed in plants)[40]. And (2) a chromatin remodeling mechanism where, after the repression mediated by Aux/IAAs is relieved, unknown cAMP-dependent chromatin remodeling remains essential to activate the expression of auxin response genes. Based on the activation of auxin response gene transcription by axr3 fused with adenylate cyclase, it is more plausible to speculate that cAMP may play a role in histone acetylation because the re-acetylation of histones can relieve the inhibition of TPL-HDAC. This speculation is also based on cAMP involved histone acetylation via CREB1 (cAMP response element binding protein) and CRRBBP/KAT3A (CREB binding protein/lysine acetyltransferase 3A) in animals[41,42].

Termination of cAMP signaling

-

The identity and regulation of plant phosphodiesterases (PDEs) responsible for degrading cAMP remain unclear[27,40].

Coordination of fast and canonical auxin responses

-

Future research should explore the interplay between rapid, non-transcriptional signaling (e.g., involving Ca2+ or cGMP) and slower transcriptional reprogramming.

Compartmentalization and crosstalk of cAMP signaling by distinct AC in plants

-

Emerging evidence reveals that plant ACs are encoded by genes producing multifunctional proteins, which possess not only AC activity but also additional enzymatic functions, prompting two key questions: (1) whether cAMP pools generated by different AC isoforms interact, and (2) how cells achieve signaling specificity while coordinating downstream responses.

In conclusion, the discovery of adenylate cyclase activity in TIR1/AFBs adds a previously unrecognized dimension to auxin signaling, linking hormone perception to localized second messenger production. This work not only reshapes our understanding of TIR1/AFB function but also offers a powerful framework for dissecting signaling complexity in other hormone pathways.

We are deeply grateful to Prof. Guang-Qin Guo for his invaluable insights and constructive suggestions on this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20240214), the Field Frontier Program of the Institute of Soil Science (Grant No. ISSAS2412), the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (Grant No. 22JR5RA462), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos lzujbky-2023-22 and lzujbky-2024-jdzx05), and the Enterprise Cooperation Projects (Grant No. Am20230457BC).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: data collection: Di DW, Wu L; figure preparation: Wu L; draft manuscript preparation: Di DW, Kriechbaumer V, Wu L; manuscript revision: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

This study is a mini review article and does not contain any original datasets. All referenced data can be found in the cited publications.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu L, Kriechbaumer V, Di DW. 2025. Emerging roles of cAMP: a transcriptional master regulator in the canonical TIR1/AFB-mediated auxin signaling. Plant Hormones 1: e018 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0018

Emerging roles of cAMP: a transcriptional master regulator in the canonical TIR1/AFB-mediated auxin signaling

- Received: 25 June 2025

- Revised: 10 August 2025

- Accepted: 14 August 2025

- Published online: 09 September 2025

Abstract: Recent breakthroughs have revealed that the auxin receptors TIR1/AFB possess adenylate cyclase (AC) activity, producing the second messenger 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) to regulate transcription. This fundamentally reshapes our understanding of auxin signaling. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the dual functionality of TIR1/AFBs: mediating both the canonical SCFTIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA-ARF cascade and auxin-induced cAMP production. Genetic and biochemical evidence demonstrates that Aux/IAA interaction enhances TIR1/AFB's AC activity, while locally generated cAMP near ARFs can activate transcription independently of Aux/IAA degradation, suggesting the presence of a parallel signaling axis. As a central hub, cAMP further integrates auxin responses with other hormonal pathways (e.g., ABA, JA, SA, and GA3) through bidirectional crosstalk. In this review, two mechanistic models are proposed for cAMP-mediated ARF activation: (1) kinase cascades via cAMP-dependent phosphorylation, and (2) chromatin remodeling through histone acetylation. Key unresolved questions include spatiotemporal control of cAMP gradients, identification of plant phosphodiesterases (PDEs), and coordination between fast and canonical auxin signaling responses. These findings establish cAMP as a pivotal regulator in auxin signaling and hormonal crosstalk, providing novel insights into plant development and stress adaptation.

-

Key words:

- Auxin signaling /

- TIR1/AFB /

- Adenylate cyclase /

- cAMP