-

Senescence is a universal life characteristic of all organisms, playing a significant role in the survival and adaptation of plants. In the final stage of plant growth and development, senescence is typically characterized by the gradual and orderly degradation of macromolecules and organelles, accompanied by the directional redistribution of nutrients from senescing organs to developing tissues[1−3]. Plant senescence is a complex biological process mediated by a multi-level regulatory network, involving the dynamic integration of endogenous developmental signals and exogenous environmental stresses. Among these, plant hormones play a core regulatory role in organ-level programmed senescence by precisely regulating the expression of related genes and physiological-biochemical reactions[4,5]. As an important component of the horticultural industry, the postharvest senescence of cut flowers directly affects their ornamental and economic values, making it one of the key scientific issues restricting industrial development[3,6].

Among numerous hormones, ethylene is recognized as the 'core regulatory factor' for the senescence of ethylene-sensitive cut flowers[7]. As a gaseous plant hormone, ethylene plays a crucial role in the senescence process of cut flowers. It not only regulates the expression of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase (ACS) and ACC oxidase (ACO) genes to form an autocatalytic ethylene biosynthesis pathway, but also regulates petal senescence-related genes directly or indirectly through signaling pathways such as ethylene insensitive 2 (EIN2) and EIN3, participating in petal senescence and flower organ abscission[8]. It is worth noting that the regulatory effect of ethylene exhibits significant species specificity, coupled with conserved crosstalk with ABA: in a typical ethylene-sensitive cut flowers such as carnations and roses, ethylene dominates senescence regulation (with its concentration and action time directly affecting the rate), while ABA synergistically enhances this process through mutual promotion[9−13]; In contrast, in ethylene-insensitive cut flowers such as lilies chrysanthemums and lilies, ABA serves as the primary regulator of the senescence process, whereas ethylene may only exert a secondary or synergistic function[7] (Table 1). Cultivars/varieties with high ethylene sensitivity exhibit severe damage upon ethylene exposure, characterized by abnormal flower morphology (bull bud), accelerated petal wilting, and abscission, whereas ethylene-induced alterations are minimal in less sensitive cultivars/varieties[6]. In-depth analysis of the regulatory mechanisms of hormones on cut flower senescence not only helps to reveal the molecular logic of plant organ programmed death, but also provides theoretical support for the development of new preservation technologies.

Table 1. Comparison of regulatory mechanisms of ethylene and ABA in cut flower senescence.

Regulatory factor Ethylene ABA Target plants Ethylene-sensitive cut flowers (carnations and roses) Ethylene-insensitive cut flowers (chrysanthemums and lilies); sometimes collaborates with ethylene in sensitive flowers Biosynthetic pathway Catalyzed by ACC synthase (ACS) and ACC oxidase (ACO): SAM → ACC → ethylene, with ACS as the rate-limiting step Mediated by 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED): carotenoids → ABA, with NCED as the key rate-limiting enzyme Signaling pathway EIN2-EILs signaling cascade: Ethylene binds to receptors (DcETR1) → inhibits CTR1 → activates EIN2 → EILs transcription factors regulate senescence genes ABA accumulation induced by NCED activates WRKY, HD-Zip and other transcription factors, triggering oxidative stress Key genes/proteins ACS/ACO genes (DcACS1, DcACO1), signaling components EIN2,

DcEIL3-1, transcription factors DcWRKY33, RhERF3NCED genes (DcNCED2, DcNCED5), transcription factors TgWRKY75, PlMYB308, oxidase DcRBOHB Hormone interactions Antagonizes cytokinin (CTK): promotes CTK O-glucosylation and degradation; synergizes with ABA: activates ABA biosynthesis

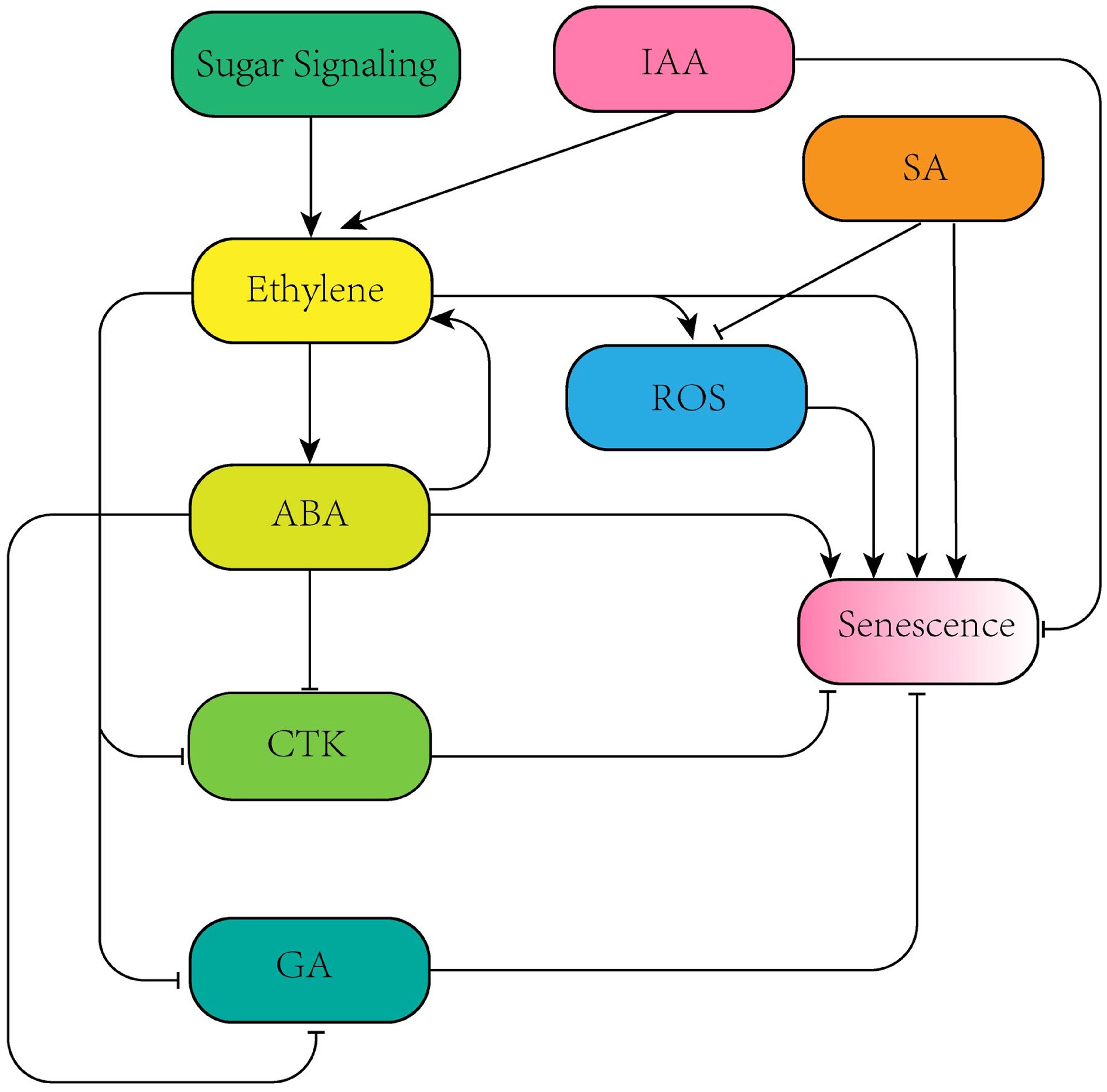

genes via DcWRKY33Synergizes with ethylene: activates ethylene biosynthesis genes via RhERF3; antagonizes gibberellin (GA): inhibits GA synthesis and promotes membrane permeability Applications in preservation technology 1-MCP (irreversibly binds to ethylene receptors), AVG (inhibits ACS activity), sucrose (suppresses ethylene biosynthesis gene expression) ABA antagonist pyrabactin (inhibits ABA signaling), GA3 (antagonizes ABA effect), sucrose (regulates water and carbon metabolism) The synergistic and antagonistic interactions among multiple hormones jointly influence the physiological and biochemical changes during cut flower senescence, further enriching the senescence regulatory network (Fig. 1). In the senescence process of ethylene-sensitive cut flowers, as a key regulatory factor, ethylene can regulate senescence through interactions with hormones such as auxin, abscisic acid, cytokinin, gibberellin, and polyamines, and can also interacts with sugars to jointly regulate the expression of related genes, thereby affecting the senescence of cut flowers[14−17]. These complex interaction relationships indicate that cut flower senescence is not a 'solo performance' of a single hormone, but the result of the dynamic balance of a multi-hormone network.

There are still many gaps in the research on the influence of hormones on cut flower senescence, such as the precise action targets of abscisic acid in ethylene-insensitive cut flowers, the quantitative model of multi-hormone interactions, and the practical application effects of preservation technologies based on hormone regulation, all of which need further in-depth exploration. This review examines the regulatory mechanisms and interaction relationships of hormones in cut flower senescence, and discusses their application potential in postharvest preservation, combined with the latest research progress, in order to provide theoretical references for prolonging the lifespan of cut flowers and improving their commercial value.

-

As a gaseous plant hormone, ethylene plays a key role in plant growth and development, stress responses, and the post-harvest shelf life of vegetables, fruits, and flowers[18−22]. The ethylene signaling pathway has been deeply studied in plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa[23−26]. The biosynthesis and signal transduction of ethylene are two steps of the ethylene response[27−29]. Ethylene biosynthesis is initiated by the conversion of methionine to S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM); SAM is then converted to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) by ACC synthase (ACS). Finally, ACC is oxidized to ethylene by ACC oxidase (ACO). The synthesis step of ACC is generally considered the rate-limiting step of ethylene biosynthesis[29]. The generated ethylene regulates the senescence of cut flowers through signaling pathways such as EIN2 and EIN3[8].

Ethylene biosynthesis directly affects senescence

-

The core enzymes of ethylene biosynthesis are ACS and ACO, and the expression levels of their encoding genes directly determine the ethylene production, thereby accelerating the process of senescence.

Ethylene plays a key role in the petal senescence process of carnations. Removing the pistil does not affect the induction of petal senescence and ethylene production. During senescence, the transcription levels of DcACS1 and DcACO1 genes in petals increase, and ethylene production rises[30,31]. In long-vase-life carnation varieties such as 'Miracle Rouge', 'Miracle Symphony', and 'Sandrosa', as well as the super-long-life carnation line 532-6, they are related to the low expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes DcACS1 and DcACO1, low ethylene production, and different expression patterns of senescence-related genes. Currently, there is a lack of direct research on the specific responses of long-vase-life ethylene-sensitive cultivars such as 'Miracle Rouge' to ABA. It is hypothesized that the low-ethylene environment characteristic of these long vase-life varieties may downregulate the expression of ABA signaling-related genes, thereby weakening the petal response to ABA and consequently delaying senescence[32,33].

In petunias, the ethylene response element binding factor PhERF71 and the bHLH transcription factor PhFBH4 are upregulated during flower senescence. They directly bind to the promoters of ethylene synthesis genes PhACS4, PhACO4, and PhACS1, respectively, activating the expression of related genes to promote ethylene production, thereby accelerating flower senescence[34,35]. The transcription factor PhHD-Zip is upregulated during flower senescence. Silencing this gene can extend the lifespan of cut flowers by 20%, reduce the transcription of ethylene and related hormone synthesis genes, and lower the expression of senescence-related genes[36].

PlMYB308 in peonies can specifically bind to the promoter of PlACO1, induce ethylene production, and make ethylene accumulate in leaves; silencing PlMYB308 significantly increases the content of gibberellin in petals, playing a role in delaying senescence[37]. The rehydration treatment of rose cut flowers activates the RhMKK9-RhMPK6-RhACS1 signaling cascade, rapidly inducing ethylene biosynthesis in the pistil, thereby accelerating petal senescence[38]. The flower senescence of tulip 'American Dream' and lily is regulated by ethylene. The expression of ethylene synthesis genes (such as TgACS1/2, TgACO, LbACS, LbACO) is significantly upregulated during senescence, and the ethylene release increases. Exogenous ethylene treatment accelerates senescence, while the inhibitor 1-MCP delays senescence by binding to ethylene receptors and blocking ethylene action[39,40]. Exogenous nitric oxide (NO) treatment of roses can reduce ethylene production by inhibiting the activity of ACO, prolonging the vase life of cut flowers[41].

In addition, overexpression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) in transgenic tobacco can enhance ethylene biosynthesis, promote an increase in ethylene production in flowers and upregulation of related gene expression, thereby accelerating flower senescence. This indicates that PI3K plays an important role in the hormone regulation of cut flower senescence by affecting the ethylene signal transduction[42].

Ethylene signal transduction and cell structure regulation

-

The ethylene signal transduction takes the 'receptor-CTR1-EIN2-EILs' pathway as the core, and dynamically balances the signal intensity through ubiquitination and degradation, transcriptional regulation, and epigenetic modification, which is the core regulatory network of cut flower senescence.

As downstream components of the ethylene signaling pathway, Ethylene Responsive Factor (ERF) family proteins play a crucial role in petal senescence by regulating the expression of target genes, and they are differentially regulated in ethylene-sensitive and ethylene-insensitive cut flowers. In petunias, the expression peaks of some PhERF genes (PhERF2-5) are synchronized with the ethylene production peak and the progression of petal senescence, and exogenous ethylene can accelerate their expression[43]. In contrast, in baby's breath (Gypsophila), the expression level of the ethylene response sensor (ERS) is low, and the number of downstream ethylene response factor (ERF) genes is significantly reduced (only 34, much lower than 205 in bananas, and 118 in Arabidopsis), which contributes to its ethylene insensitivity[44].

Under ethylene induction, DcEBF1/2 in carnations regulates the expression of downstream genes by ubiquitination and degradation of the ethylene signal core transcription factor DcEIL3-1, and DcEIL3-1 can activate the promoters of DcEBF1/2. The two interact to participate in petal senescence regulation[45]. During the senescence process of rose cut flowers, ethylene regulates petal senescence through the synergistic regulation of multiple signaling pathways: inducing the expression of the F-box protein gene RhSAF, and its encoded protein promotes the degradation of the gibberellin receptor RhGID1 as an SCF-type E3 ligase recognition subunit, weakening the gibberellin signal; the calcium signal-related RhCBL4-RhCIPK3 module phosphorylates and promotes the degradation of the jasmonic acid response inhibitor RhJAZ5 under ethylene induction, relieve the inhibition of downstream senescence genes; the protein kinase RhCIPK6 responds to ethylene signals, directly binds to RhCBL3 to activate the expression of downstream senescence genes, and accelerates petal senescence[46−48].

Blocking receptors can effectively delay ethylene-induced cut flower senescence. 1-MCP inhibits ethylene perception by irreversibly binding to the ethylene receptors of carnations (DcETR1, DcERS1). A single treatment can delay, but not completely block, the expression of ethylene synthesis genes (DcACS1, DcACO1) and petal involution senescence, while multiple treatments can continuously inhibit receptor synthesis and ethylene response, extending the vase life by three times, providing a new perspective on receptor regulation for the preservation of ethylene-sensitive cut flowers[49]. The NOP-1 peptide derived from the ethylene signal core regulatory factor EIN2 specifically binds to ethylene receptors and blocks downstream signal transduction, significantly delaying the senescence process of cut flowers such as carnations and roses[50].

Epigenetic modifications also participate in the regulation of gene expression, including DNA methylation and histone modification, which can activate or inhibit the expression of senescence genes. At the same time, epigenetics and multiple hormones jointly construct a complex regulatory network for petal senescence[51,52]. The histone methyltransferase DcATX1 can positively regulate the expression of ethylene synthesis downstream target genes DcWRKY75, DcACO1, and DcSAG12 by regulating the level of H3K4me3, thereby accelerating ethylene-induced carnation petal senescence[53]. During ethylene-induced carnation petal senescence, the expression of the DNA demethylase DcROS1 decreases, leading to DNA hypermethylation in the promoter region of the amino acid synthesis genes, thereby reducing the accumulation of arginine and branched-chain amino acids and accelerating senescence[54].

Ethylene can also accelerate the senescence of cut flowers by affecting cell structure. Exogenous ethylene promotes the membrane lipid changes in carnation cut flower petals (increased membrane micro-viscosity and decreased fluidity), causing petal incurvature, increased electrolyte leakage and physiological function decline, accelerating the senescence process[55,56].

Synergistic regulation of transcription factors and hormone interactions

-

Transcription factors are the core nodes for ethylene to integrate multiple signals. Genes of the WRKY, NAC, ERF, and other families drive senescence by regulating ethylene synthesis, other hormone metabolism, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation.

In carnations, a typical ethylene-sensitive cut flower, DcWRKY33 directly binds to the promoter regions of ABA biosynthesis genes (DcNCED2 and DcNCED5) and ROS generation genes (DcRBOHB), activating their expression, thereby synergistically promoting the accumulation of ethylene, ABA, and ROS, forming a positive feedback regulation network, and significantly accelerating the petal senescence process[57]. The ethylene signal core transcription factor DcEIL3-1 directly activates the downstream factor DcWRKY75, jointly promoting the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes (DcACS1/DcACO1) and senescence-related genes (DcSAG12/DcSAG29), accelerating the senescence process[58]. Further studies have found that DcEIL3-1, DcWRKY75, and DcHB30 form an activation-inhibition interaction network: DcWRKY75 and DcHB30 mutually inhibit each other's expression, while DcEIL3-1 and DcHB30 also antagonize each other, forming a fine balance regulation module, jointly determining the senescence rate mediated by ethylene[59,60]. Studies have also revealed that RhWRKY33 of roses integrates mechanical damage and ethylene signals, positively regulating petal senescence. After silencing, it can delay ethylene and mechanical damage-induced senescence, and down-regulate the expression of RhSAG12. It shows that it plays a core regulatory role in abiotic stress-induced senescence by mediating the hormone interaction network dominated by ethylene[61].

In the NAC family, the transposon dTdic1 is inserted into the second exon of the ethylene-induced NAC transcription factor gene DcNAP, and a truncated variant DcNAP2 is generated through alternative splicing; DcNAP2 forms a heterodimer with the complete functional variant DcNAP1, inhibiting the transcriptional activation ability of the latter on the ethylene biosynthesis genes DcACS1 and DcACO1, thereby delaying the ethylene signal-mediated carnation petal senescence at the post-transcriptional level[62]. In Japanese petunias, exogenous ethylene can induce the NAC transcription factor EPH1 through the InEIN2-dependent pathway and accelerate the senescence process[63].

Thirteen ERF genes were cloned from petunias, and their expression patterns were different during flower senescence, and they were regulated by multiple hormones such as ethylene, ABA, and auxin. For example, Group VII PhERF2-PhERF5 is closely related to the increase in ethylene production, and may play an important role in the senescence process of petunia cut flowers[43]. The ethylene response element binding factor PhERF71 is upregulated during petunia flower senescence, and it can directly bind to the promoters of ethylene synthesis genes PhACS4 and PhACO4, promote ethylene biosynthesis, and positively regulate the flower senescence process[34]. While the ethylene response factor RhERF3 in roses directly binds to and activates the promoter of the abscisic acid biosynthesis key gene RhNCED1, promoting the accumulation of endogenous ABA, thereby accelerating ethylene-dependent petal senescence[64].

The hormonal regulation of cut flower senescence is highly complex, and the synergistic or antagonistic effects among different hormones are achieved through gene expression differences, metabolic pathway intersections, and signal cascade networks for precise regulation. Studies have found that the regulation of flowering by ethylene in cut roses 'Kardinal' and 'Samantha' has varietal differences, and the key mechanism lies in the differences in the transcription levels of ethylene receptor genes (ETR): after ethylene treatment, ETR in 'Samantha' is significantly upregulated, while the expression of ETR in 'Kardinal' remains unchanged, indicating that the differences in the expression of the hormone signaling pathway genes play a core role in the regulation of cut flower senescence[65].

Ethylene and CTK show an antagonistic effect in the regulation of cut flower senescence, forming an interaction network through metabolic modification and gene expression regulation. In petunias, ethylene promotes the O-glucosylation and degradation inactivation of cytokinins, antagonizing the senescence-delaying effect of cytokinins, and the two jointly regulate the senescence of cut flowers[66]. In roses, ethylene induces the transcription factor RhHB6 to directly activate the expression of RhPR10.1, upregulate the cytokinin metabolism-related genes, and significantly inhibit flower senescence, while the silencing of RhPR10.1 not only reduces the CTK level but also accelerates the expression of senescence marker genes[67].

The synergistic effect of ethylene and jasmonic acid (JA) is an important mechanism for the regulation of cut flower senescence, and its molecular pathway is mediated by key transcription factors. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor RhMYB108 directly binds to the promoter regions of senescence-related genes SAG113, NAC053, and NAC092 and activates their transcriptional activity, mediating the synergistic regulation of rose petal senescence by ethylene and JA[68]. In addition, the study of the interaction between sugar signals and ethylene shows that the rapid decrease in glucose and fructose content in cut flowers accelerates the induction of DcACS1, DcACO1 expression, and ethylene burst. At the same time, the transcription levels of ethylene signal genes DcEIL1/2 decrease, and the expression of autophagy-related gene DcATG8a increases synchronously with ethylene production, revealing a new mechanism by which sugar starvation accelerates senescence by enhancing ethylene metabolism and autophagy processes[69].

Application mechanisms of preservation technologies in cut flowers

-

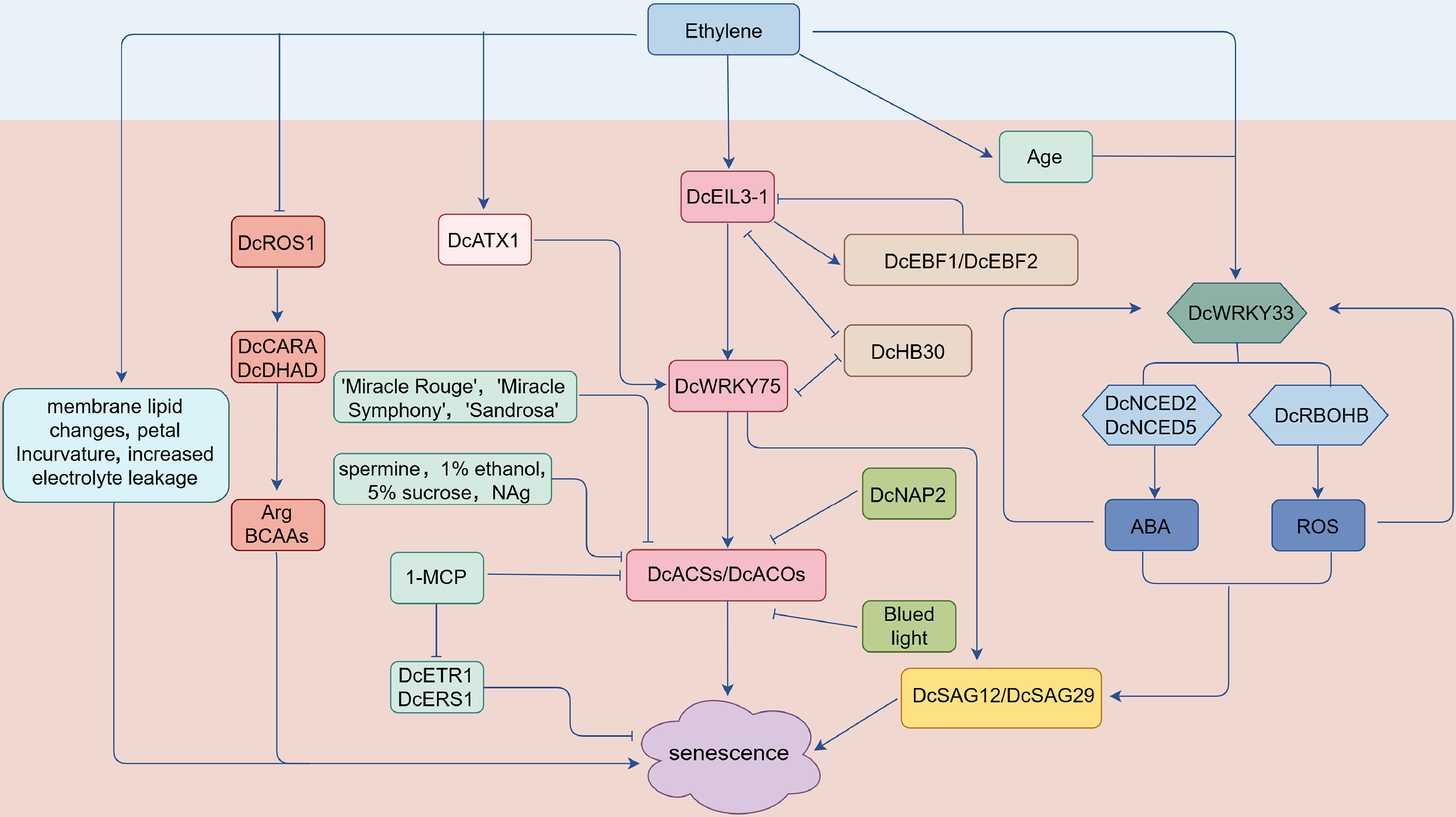

The preservation technologies for cut flowers were developed based on hormonal regulation mechanisms that delay senescence by interfering with ethylene biosynthesis and signal transduction. Treatments with spermine, 1% ethanol, and 5% sucrose all delay carnation senescence and prolong their vase life by inhibiting the activity and transcription level of key ethylene synthesis enzymes (ACS and ACO) and reducing ethylene production. Among them, sucrose inhibits the expression of Dc-EIL3, a core transcription factor in the ethylene signaling pathway, thereby blocking the activation of downstream ethylene-responsive genes (such as ACS and ACO)[70−73]. NAg treatment can significantly inhibit ethylene production and delay carnation petal senescence. This process is related to NAg inhibiting the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes (ACS1 and ACO1), petal senescence-related genes (CP1), and ethylene signal transduction positive regulatory genes (EIL1/2, ERS2, EBF1), while upregulating the expression of senescence inhibitory gene CPi[74] (Fig. 2). Ethylene accelerates the opening of rose 'Samantha' flowers by regulating the expression of receptor ETR and CTR genes, and drives the variety-specific senescence (petal abscission/wilting) of dahlias. Its effect is jointly regulated by the developmental stage and the endogenous ethylene production pattern, and the ethylene inhibitor 1-MCP can effectively block this effect[75,76].

Figure 2.

Regulatory network diagram of ethylene-mediated petal senescence in carnation. ACS:1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase; ACO: ACC oxidase; DcEIL3-1: core ethylene-responsive transcription factor (homolog of ethylene-insensitive 3-like 1); DcEBF1/2: homologs of EIN3-binding F-Box protein 1/2; DcROS1: DNA demethylase; DcATX1: histone methyltransferase; DcWRKY33, DcWRKY75: WRKY transcription factors; DcNCED2/5: 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase genes; DcRBOHB: respiratory burst oxidase homolog B; ABA: abscisic acid; DcCARA: carbamoyl-phosphate synthase subunit A; DcDHAD: dihydroxyacid dehydratase; Arg: arginine; BCAAs: branch chain amino acids; DcETR1, DcERS1: ethylene receptors; DcSAG12/29: senescence-associated genes.

-

ABA is an important plant hormone that participates in the regulation of plant growth and development, plays a crucial role in responding to abiotic stresses, inducing stomatal closure, promoting senescence, regulating seed dormancy and germination, etc. At the same time, abscisic acid also has signal cross-interactions with other hormones to jointly coordinate plant growth and stress responses[77−80]. N-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) is a key rate-limiting enzyme in ABA biosynthesis[81]. In ethylene-sensitive cut flowers, the role of abscisic acid may be dependent on ethylene; in ethylene-insensitive cut flowers, abscisic acid replaces ethylene as the primary hormone for senescence[6,8].

For ethylene-insensitive flowers, when the flowers of Calendula officinalis transition from the fully open stage (Stage IV) to the senescence stage (Stage V), the ABA content in petal tissues increases significantly, with the highest ABA content observed in senescent petal tissues. In contrast, ethylene content does not show a significant increase across various developmental stages, and there is no significant difference between the senescence stage V and the fully open stage IV[82]. It is reasonable to hypothesize that in ethylene-insensitive flowers, the expression of genes related to the ABA pathway may occur more rapidly than that of the ethylene pathway; however, relevant reports remain scarce. In the future, time-series transcriptome analysis can be performed on the senescence process of ethylene-insensitive species to monitor the expression dynamics of key genes in the ABA pathway (NCED, WRKY75) and the ethylene pathway (ACS, ACO, ERF). Combined with verification using real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR), the occurrence time of expression peaks and the upregulation rates of these two types of genes can be compared to clarify their temporal differences during the senescence process.

ABA signaling pathway mediated by transcription factors

-

A variety of transcription factors become key nodes for ABA to regulate senescence by regulating ABA synthesis or signaling genes. During the senescence of tulip petals, the content of ABA increases significantly, and the HD-Zip transcription factor TgHB12-like positively regulates the petal senescence process by upregulating the expression of the senescence-related gene TgSAG6[83]. Exogenous application of ABA to tulips induces the expression of the transcription factor TgWRKY75, which directly binds to and activates the transcription of the ABA synthesis-related gene TgNCED3, increases ABA accumulation, and promotes petal senescence[84]. Blue light significantly delays the senescence of carnation cut flowers and prolongs the vase life by 33% by inhibiting the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes DcACS1 and DcACO1 and upregulating ABA biosynthesis and transport-related genes DcZEP1, DcNCED1, and DcABCG40[85]. In peonies, the PlMYB308 transcription factor directly activates the promoter of the ethylene biosynthesis gene PlACO1, promotes the accumulation of ethylene and ABA, and inhibits the synthesis of GA, thereby accelerating petal senescence[86]. The PlZFP gene specifically regulates ABA biosynthesis by targeting PlNCED2, positively regulating the flower senescence process[87].

Bidirectional regulation of ABA: context-dependent differentiation between promoting and delaying senescence

-

ABA has both promoting and delaying effects on the regulation of cut flower senescence, and realizes the fine regulation of the senescence process through hormone interactions, signal transduction, and antioxidant mechanisms.

During the natural senescence process of the leaves of the Asiatic lily 'Courier', the content of ABA increases, and dark treatment can accelerate ABA accumulation and induce leaf premature senescence; exogenous spraying of ABA promotes leaf senescence, and its antagonist pyrabactin delays chlorophyll degradation and photosystem II inactivation by inhibiting ABA signals, playing a role in delaying senescence[88]. DcWRKY33 and ethylene response factor RhERF3 directly bind to the promoter regions of ABA biosynthesis genes (DcNCED2, DcNCED5, and RhNCED1), activate their expression, promote the accumulation of endogenous ABA, and form a positive feedback regulation network to accelerate ethylene-dependent petal senescence[57,64].

Studies have found that ABA induces the synthesis of NO, synergistically inhibits stomatal opening, reduces water loss, and activates the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), maintains chlorophyll content, and thus delays the senescence of rose cut flowers[89]. In rose petals, the ABA signaling pathway directly activates the expression of the ferritin gene RhFer1 through the transcription factor RhABF2, regulates iron ion homeostasis, and reduces dehydration-induced oxidative stress, thereby enhancing the dehydration tolerance of petals; at the same time, the RhABF2/RhFer1 module works together with iron transport genes to delay the natural senescence process[90].

Interaction regulation between ABA and other hormones

-

The synergistic effect of ABA and ethylene is one of the core pathways for the regulation of cut flower senescence, and the two form a positive feedback loop through the gene expression network mediated by transcription factors. The transcription factor DcWRKY33 can promote the accumulation of ethylene, ABA, and ROS, forming a synergistic network that accelerates carnation petal senescence[57]. The ethylene response factor RhERF3 directly binds to and activates the promoter of the abscisic acid biosynthesis key gene RhNCED1, promotes the accumulation of endogenous ABA, and thus accelerates the ethylene-dependent petal senescence of roses[64]. ABA can also accelerate senescence by promoting ethylene synthesis and enhancing the sensitivity of carnations to ethylene, while the ethylene synthesis inhibitor AVG can completely offset the senescence-promoting effect of ABA[91]. However, in ethylene-insensitive flowers, existing studies have primarily focused on the regulatory role of ABA as the main hormone in senescence, while the antagonistic interaction mechanism between ABA and ethylene remains underexplored. However, in Arabidopsis thaliana, abscisic acid and ethylene exert antagonistic effects on seed germination and post-germinative seedling growth, with their antagonism enhanced through mutual regulation of metabolism and signal transduction. In the aba2 mutant, the key ethylene synthesis gene ACO is upregulated, suggesting that ABA may inhibit ethylene synthesis; in the ein2 mutant, the key ABA synthesis gene NCED3 is upregulated, indicating that ethylene signaling can suppress ABA synthesis[92]. Given that plant hormone interaction mechanisms are generally conserved across species, it is hypothesized that similar mechanisms may exist in ethylene-insensitive flowers. Future studies could employ transcriptome sequencing to screen for genes in ethylene-insensitive flowers that respond to both ABA and ethylene, and examine whether these genes mediate their antagonistic signals.

The dynamic balance between ABA and GA plays a key regulatory role in the senescence of cut flowers. In ethylene-insensitive gladiolus, the content of endogenous ABA significantly accumulates with the natural senescence of petals. Exogenous ABA treatment accelerates the senescence process by enhancing membrane permeability, reducing water absorption, and fresh weight, while GA3 can restore membrane stability and prolong the vase life by antagonizing the effect of ABA[93]. Similarly, exogenous application of ABA (10–100 μM) significantly shortens the vase life of 'Dutch Master' daffodil cut flowers, and GA3 can also antagonize the effect of ABA to delay senescence[94]. Studies have also shown that silencing the PlZFP gene can reduce the levels of ethylene and ABA and increase the content of GA, thereby delaying the senescence of peony flowers[87].

In addition, ABA and sucrose have an antagonistic effect on cut flower senescence, and synergistically delay the senescence of Eustoma and 'Super Star' rose cut flowers by regulating water balance and carbon metabolism pathways, providing a new strategy mechanism for the preservation of cut flowers[95,96].

-

GA plays a role in the regulation of flower senescence through transcription factor interactions and metabolic dynamic balance. The bZIP transcription factor PhOBF1 of petunia can specifically bind to the promoter of the GA biosynthesis gene PhGA20ox3, regulate the accumulation of active GA, and negatively regulate the ethylene-mediated flower senescence[97]. During the senescence of rose petals, ABA, and ethylene induce the expression of RhHB1, which in turn inhibits the expression of the GA biosynthesis gene RhGA20ox1, reduces the level of active GA, and promotes petal senescence[98]. In peonies, the upregulation of the expression of gibberellin degradation genes PoGA2ox1 and PoGA2ox8.1 reduces the level of active gibberellin and accelerates flower senescence[99]. In addition, studies on 'White Prosperity' gladiolus show that soaking bulbs in benzyl adenine (BA, 200 mg/L) and gibberellin (GA3, 100 mg/L) before harvesting can increase the content of soluble sugars, proteins, and chlorophyll in petals and leaves, delay protein degradation and chlorophyll decomposition, extend the vase life to 11 d, and significantly improve the quality of cut flowers[100].

-

CTK shows bidirectional effects of delaying and promoting in the regulation of cut flower senescence, and its function is realized through hormone interactions, gene expression regulation, and tissue-specific responses. CTK can delay senescence by inhibiting chlorophyll degradation, activating antioxidant enzymes (such as CAT, APX, SOD), and upregulating photosynthesis-related genes (such as CAB, RBCS). Its synthetic derivatives (such as TDZ, 3F-BAPR) have better anti-aging activity than natural CTK due to their structural stability and receptor affinity advantages[101].

Delaying effect and mechanism of CTK on cut flower senescence

-

In petunias, exogenous application of the cytokinin analog 6-benzylaminopurine (BA) can significantly prolong the vase life of cut flowers by inhibiting the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes (such as PhACS, PhACO) and receptor genes (such as PhERS1, PhETR2)[102]. Exogenous application of kinetin (5–10 μg/mL) to carnations prolongs the vase life of cut flowers by reducing the ethylene peak production (by more than 55%), delaying the occurrence time of the ethylene peak, and reducing the sensitivity of flowers to ethylene[103]. Studies have also shown that CTK pretreatment of carnation petals can inhibit ethylene synthesis through multiple pathways, and there are tissue-specific responses to CTK between leaves and petals[56]. The ethylene response transcription factor RhERF113 positively regulates the expression of CTK biosynthesis genes (such as RhIPT5, RhIPT8) and signaling pathway-related genes (RhHK2, RhHK3, RhCRR3/5/8), significantly increasing the content of isopentenyladenosine (iPA) in rose petals, and playing a role in delaying senescence[104].

Promoting effect and mechanism of CTK on cut flower senescence

-

During the senescence of rose cut flowers, CTK accumulates in the petal abscission zone as a promoter of petal abscission, and CK-induced RhLOL1 interacts with the bHLH transcription factor RhILR3 to activate the expression of Aux/IAA genes, thereby accelerating petal abscission[105]. The RhNAP transcription factor directly activates the CTK oxidase gene RhCKX6, promotes CTK degradation, enhances dehydration tolerance by reducing CTK levels in young petals, and accelerates senescence in mature petals. This process interacts with ABA signals and is independent of stomatal regulation[106].

The role of CTK in variety differences and senescence timing

-

The content and activity of endogenous CTK in the young petals of the long-life rose variety 'Lovita' are significantly higher than those of the short-life variety 'Golden Wave', indicating that the difference in CTK content may be one of the reasons for the different life spans between varieties[107]. Application of a GA and CTK compound agent 1 d after flowering of the lily 'White Heaven' can prolong the vase life by more than 2 d, and the treatment after 4 d and later is ineffective. Along with the decrease in the content of endogenous active CTK (IPA) and the late increase in ABA, it indicates that the dynamic balance between hormones and the timing change of tissue sensitivity regulates senescence, and there is a key time node for hormone intervention[108].

-

The auxin-sucrose module plays an important role in cut flower senescence by regulating carbon distribution and hormone signal interactions. Auxin maintains the transport of sucrose to the petals by directly activating the expression of the sucrose transporter RhSUC2, inhibits ethylene sensitivity, and delays rose petal abscission; exogenous application of auxin or sucrose can significantly delay the abscission process induced by ethylene[109].

-

SA has both delaying and promoting effects in the regulation of cut flower senescence, and its function is closely related to the treatment timing, plant species, and molecular regulation network. In Eustoma cut flowers, 0.5 mM SA treatment during the reproductive period using a hydroponic method can significantly prolong the vase life of some varieties (such as 'Blue Picote' and 'Kroma White')[110]. The tulip NAC transcription factor TgNAP directly activates the transcription of SA biosynthesis genes TgICS1 and TgPAL1, and inhibits the expression of ROS scavenging-related genes TgPOD12 and TgPOD17, dual-regulates the accumulation of SA and the dynamic balance of ROS, thereby positively mediating the petal senescence process, confirming that it plays a core hub role in the cut flower senescence regulation network by integrating SA signals and oxidative stress pathways[111].

-

The regulation of cut flower senescence by plant hormones is a complex network mechanism. As the core regulatory factor for the senescence of ethylene-sensitive cut flowers (such as carnations and roses), ethylene catalyzes the biosynthesis of ethylene by activating the expression of ACS and ACO genes, and regulates petal senescence-related genes through signaling pathways such as EIN2 and EIN3. Its role involves the coordination of transcription factors (such as ERF, WRKY families), epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation, histone modification), and cell structure damage (membrane lipid changes, electrolyte leakage). In ethylene-insensitive cut flowers (such as chrysanthemums and lilies), ABA replaces ethylene as the dominant hormone for senescence, driving senescence by regulating the synthesis genes of NCED and interacting with GA and CTK.

Differences in the expression levels and activities of ethylene biosynthesis-related genes (ACS, ACO) can indirectly affect ethylene sensitivity. A study on 33 rose cultivars with varying ethylene sensitivity revealed that the transcriptional abundance of RhACO1 in roses is significantly correlated with ethylene sensitivity and vase life[112]. In the ethylene signaling pathway, alterations in the expression or sequence of ethylene receptors can partially account for the differences in ethylene sensitivity among different species and cultivars[6]. There are differences in the expression levels of receptor genes between short-lived and long-lived rose cultivars[65,113]. Meanwhile, differences in the expression and function of downstream transcription factors (such as EIN3, EILs, and ERFs) can also influence ethylene sensitivity. A 7-bp frameshift mutation in the EIN3-like2 (EIL2) gene in Campanula leads to ethylene insensitivity in floral organs[114].

In addition, multi-hormone interactions, sugar signals, ROS, and other factors jointly participate in senescence regulation. At present, preservation technologies based on hormonal regulation (such as 1-MCP inhibiting ethylene signals and sucrose maintaining sugar levels) have been applied in some cut flowers, but the ABA action targets of ethylene-insensitive cut flowers, the quantitative model of multi-hormone interactions, and the broad-spectrum nature of preservation technologies still need in-depth study.

With the continuous development of artificial intelligence (AI), it is expected to develop a cut flower senescence prediction model based on machine learning in the future, combined with physiological indicators such as real-time monitored ethylene/ABA concentration and sugar content, to dynamically optimize the preservative formula. At the same time, AI can be used to design new molecular inhibitors, and screen small-molecule compounds targeting ethylene receptors (such as DcETR1) or ABA synthases (NCED) through structural biology simulation to improve preservation efficiency.

This work was supported by the National Key Laboratory for Germplasm Innovation & Utilization of Horticultural Crops (Grant No. Horti-3Y-2024-015), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos 2662025YLPY006, 2662023PY023, and 2662019PY049), the Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan-Basic Research (Grant No. 2023020201010106), the Thousand Youth Talents Plan Project and the Start-up Funding from Huazhong Agricultural University to FZ, and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos 2662025YLPY008 and 2662023PY011), the Young Scientist Fostering Funds for the National Key Laboratory for Germplasm Innovation & Utilization of Horticultural Crops (Grant No. Horti-PY-2023-001), and the Yunnan Xingdian Talents-Special Selection Project for High-level Scientific and Technological Talents and Innovation Teams-Team Specific Project (Grant No. 202505AS350021).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, project supervision, manuscript editing: Zhang F; draft manuscript preparation: Yao H; manuscript review and suggestions: Zhong L, Luo J, Cheng Y, Bao M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yao H, Zhong L, Luo J, Cheng Y, Bao M, et al. 2025. Molecular mechanisms and research advances of plant hormone regulation in cut flower senescence. Plant Hormones 1: e020 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0021

Molecular mechanisms and research advances of plant hormone regulation in cut flower senescence

- Received: 28 June 2025

- Revised: 28 August 2025

- Accepted: 05 September 2025

- Published online: 26 September 2025

Abstract: Plant hormones play pivotal roles in regulating cut flower senescence. Ethylene dominates senescence in ethylene-sensitive species (such as carnations and roses) by activating senescence-associated genes via ACS/ACO-mediated biosynthesis and the EIN2-EILs signaling cascade, with abscisic acid (ABA) synergistically promoting this process through crosstalk. Conversely, ABA drives senescence in ethylene-insensitive cut flowers (such as chrysanthemums and lilies) through the NCED pathway-induced ABA accumulation and triggers oxidative stress, while ethylene may play a secondary collaborative role. Interactions among ethylene, ABA, gibberellin (GA), cytokinin (CTK), auxin, and salicylic acid (SA) form a sophisticated regulatory network. These hormones orchestrate senescence through biosynthesis pathways, signal transduction, transcription factors, epigenetic modifications, and cellular structural regulation. Preservation technologies based on hormonal regulation, such as 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and sucrose treatments, have been successfully implemented. Understanding these molecular mechanisms and hormonal crosstalk provides a theoretical foundation for extending vase life and enhancing the commercial value of cut flowers.

-

Key words:

- Plant hormone /

- Cut flower /

- Senescence /

- Ethylene /

- Abscisic acid