-

Thermal processing remains the primary method for food preservation. Clostridium botulinum, a highly toxic foodborne pathogen, produces highly heat-resistant spores that frequently contaminate canned and sealed pickled foods, making it the target of thermal sterilization/pasteurization for these products[1]. The heat resistance of spores was commonly characterized by D-values, which refer to the time required to kill 90% of the microbial population[2]. Due to the physiological similarities (including high spore heat resistance), Clostridium sporogenes serves as a surrogate for C. botulinum in developing thermal sterilization/pasteurization processes for low-acid packaged foods. Accordingly, determining the heat resistance of C. sporogenes spores is critical in establishing sterilization procedures, validating microbial safety, and conducting rapid risk assessments for low-acid packaged foods[1,3]. Therefore, the preparation of C. sporogenes spores that meet research requirements is necessary for related studies. In-depth investigations into the heat resistance of C. sporogenes spores and the influence of their sporulation conditions are not only important for understanding their microbial mechanisms under heating, but also serve as a core basis for scientifically designing thermal sterilization/pasteurization protocols in food processing.

Many factors can affect the spore heat resistance during sporulation, such as temperature and calcium salt addition[4−6]. Studies have shown that Bacillus subtilis spores formed at higher sporulation temperatures exhibit higher heat resistance, possibly due to dramatic changes in the spore coat assembled under elevated temperatures[7]. For the heat resistance of C. sporogenes spores, reported studies are mainly focused on thermal processing environment and thermal processing techniques[8−11], the influence of sporulation conditions on spore heat resistance is limited. Studies have shown that the addition of calcium salts is a key measure for regulating spore heat resistance. Yamazaki et al.[12] found that calcium-depleted B. subtilis spores had significantly lower heat resistance compared to calcium-containing spores; Lee et al.[13] compared the effects of different metal ions (Mg2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, and Ca2+) on the heat resistance of Clostridium perfringens spores, and found calcium ions were the most effective in enhancing heat resistance. This is attributed to calcium ions binding with dipicolinic acid (DPA) in the spore to form Ca-DPA chelates, promoting core mineralization and reducing the spore core water content, thereby enhancing spore heat resistance[14−16]. However, existing studies primarily focus on the effects of various cations on spore heat resistance[13,16], with limited research on how different calcium salts—especially those with varying water solubility and anions—affect spore heat resistance. In practice, poor solubility of calcium salts in culture media can result in residual undissolved particles, which may interfere with subsequent experiments such as spore purification and microscopic examination. Therefore, identifying calcium salts that effectively supply Ca2+ without disrupting subsequent procedures and exploring their impact on spore heat resistance is of importance for enriching the theoretical understanding of spore heat resistance.

Spore purification is a key step in eliminating experimental interference factors. The most commonly used spore purification methods are heat treatment and lysozyme digestion[17,18]. However, inappropriate heat treatment temperatures or lysozyme concentrations may damage spore structure or even cause spore inactivation[19−21], which may affect heat resistance and recovery rate of the spores, thereby reducing the accuracy and reliability of experimental results[17]. Hence, identifying optimal purification conditions for C. sporogenes spores is particularly important for scientific studies using this microorganism. Currently, no research has been reported on the purification conditions for C. sporogenes spores.

Therefore, this study aims to: 1) investigate the effects of different forms of calcium salts (soluble and insoluble) on the sporulation rate and spore heat resistance of C. sporogenes by measuring spore protein content and DPA release; 2) analyze how different calcium salts influence spore composition and structure; 3) evaluate suitable lysozyme concentrations and heat treatment temperatures for spore purification process to obtain a maximized intact C. sporogenes spores.

-

C. sporogenes CICC 8021 was purchased from the China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (CICC). Tryptone glucose yeast extract broth (TPGY): tryptone 50 g/L, peptone 5 g/L, yeast extract 20 g/L, glucose 4 g/L, sodium thioglycolate 1 g/L, pH = 7.0 adjusted with 1 M NaOH. Spore medium: tryptone 60 g/L, glucose 1 g/L, sodium thioglycolate 1 g/L, calcium chloride 5.5 g/L (calcium carbonate 5 g/L, calcium fluoride 3.9 g/L, calcium gluconate 21.5 g/L), adjusted pH = 5.0 with 1 M HCl. Besides, 1.5% agar was added when preparing solid media, and all media were sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min.

Strain activation and enrichment culture

-

C. sporogenes spores stored in glycerol tubes were thawed and returned to room temperature. An inoculating loop was dipped into a small amount of spore suspension, and the streak plate method used to inoculate onto a TPGY solid plate medium. Plates were incubated anaerobically at 36 °C for 48 h to isolate single colonies. Selected single colonies were transferred to 10 mL of TPGY liquid medium for secondary activation, and the culture conditions were as described above. After secondary activation, the medium was centrifuged for 10 min (4 °C, 10,000 r/min), and the pellets were resuspended in 1 L of freshly prepared TPGY liquid medium. After 48 h of enrichment incubation at 36 °C, the culture was centrifuged (4 °C, 10000 r/min, 10 min) and washed three times with sterile water, and finally resuspended in sterile water.

Preparation of spores produced in different spore culture media

-

C. sporogenes resuspension was centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 10 min at 4 °C, and the pellets were resuspended in an equal volume of sporulation media with different calcium salts and incubated anaerobically at 36 °C for 15 d. The spores were then collected and washed three times with sterile water, and centrifugation conditions were as described above. The calcium salts providing calcium ions in the four media were calcium carbonate (CaCO3), calcium fluoride (CaF2), calcium chloride (CaCl2), and calcium gluconate (C12H22O14Ca). The spores were finally resuspended in sterile water and stored in a 4 °C refrigerator.

Determination of D-value of spores

-

A total of 100 µL of the spore suspension was taken and injected into a capillary glass tube (ID: 2 mm, OD: 3 mm, length 200 mm), and both ends heat-sealed with an alcohol blowtorch. The prepared capillary glass tube samples were submerged in an oil bath and heated at a preset temperature (90 °C) for different times, then immediately removed, and the samples were quickly cooled in ice water. After cooling, the walls of the capillary glass tubes were wiped with 75% ethanol. The ends of the capillary glass tubes were cut, and the samples were rinsed out of the tubes with 900 µL of sterile water, followed by a 10-fold gradient dilution with sterile water. The samples were counted by the pouring method (1 mL of the dilution was added to a petri dish and poured into the TPGY solid medium), and incubated anaerobically at 36 °C for 48 h. Spores were counted, and survival curves were plotted based on the counting of spores at the different heat treatment times. The D90 °C of spores was obtained by linear regression of the survival curves, taking the negative inverse of the slope. The heat treatment procedures performed included heat treatment of 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 min.

Protein content of spores

-

A total of 1 mL of the spore suspension (with a concentration around 107 CFU/mL) was added to 10 mL of lysate, and then the sample was placed in an ice water bath and crushed for 1.5 s, at 3 s intervals, for 5 min[22]. The supernatant was taken by centrifugation at 1,180 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Soluble protein concentration was determined using the Bradford protein concentration assay kit.

DPA release of spores

-

The spores prepared in different media were resuspended in sterile water and heat-treated in an oil bath at 90 °C for different times, and then immediately removed and cooled in an ice water bath. The solution was centrifuged at 1,180 g for 10 min at 4 °C, 4 mL of supernatant was taken and mixed with 1 mL of color developer, the solution was immediately color developed, and the absorbance value of the solution at 440 nm was determined within 2 h. The standard curve of DPA concentration was prepared, and the amount of DPA released was calculated according to the standard curve. Color developer: 1% (w/v) Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O and 1% (w/v) ascorbic acid in 0.5 M acetate buffer at pH 5.5. The spores were autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min, and the total DPA value was determined.

Lysozyme purification method

-

A total of 1 mL of spore suspension was taken and resuspended in different concentrations of lysozyme solution by centrifugation (4 °C, 10,000 r/min, 10 min). The concentrations of lysozyme were 0.2, 0.4, 1, 1.4, and 2 μg/mL. The spores were washed with sterile water three times after incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. The washed samples were gradient diluted with sterile water, and were counted by the pouring method.

Heat-shocked purification method

-

One mililitre spore suspension was added to a 5 mL stoppered test tube (OD: 12 mm, total height 125 mm), and the test tube placed in an oil bath for 5 min at different temperatures. The treatment temperatures were 86, 88, 90, 92, and 94 °C. After heat treatment, the tubes were immediately removed and cooled in an ice water bath, and the samples were diluted with sterile water in a gradient and counted.

Fluorescent staining

-

A total of 1 mL of the purified spores was taken, and PI solution was added at a final concentration of 15 μM, and 15 min of staining was carried out at room temperature, avoiding light. The spores were resuspended in 100 μL of sterile water, and 5 μL of the resuspension solution was placed onto a slide, and then observed through a fluorescence microscope at 488 nm.

Calculation of spore recovery rate

-

Spore recovery rate was calculated using the Eq. (1):

$ \mathrm{Recoveryrate\;({\text{%}} )=A}_{ \mathrm{F}} \mathrm{/A}_{ \mathrm{0}} \times 100 $ (1) where, the Af was the number of spores at the end of the purification procedure, and A0 was the number of spores without the purification procedure.

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were repeated three times, and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD); statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). and Duncan's post-hoc test (p < 0.05) using SPSS software (version 26); graphs were plotted using Origin2024b.

-

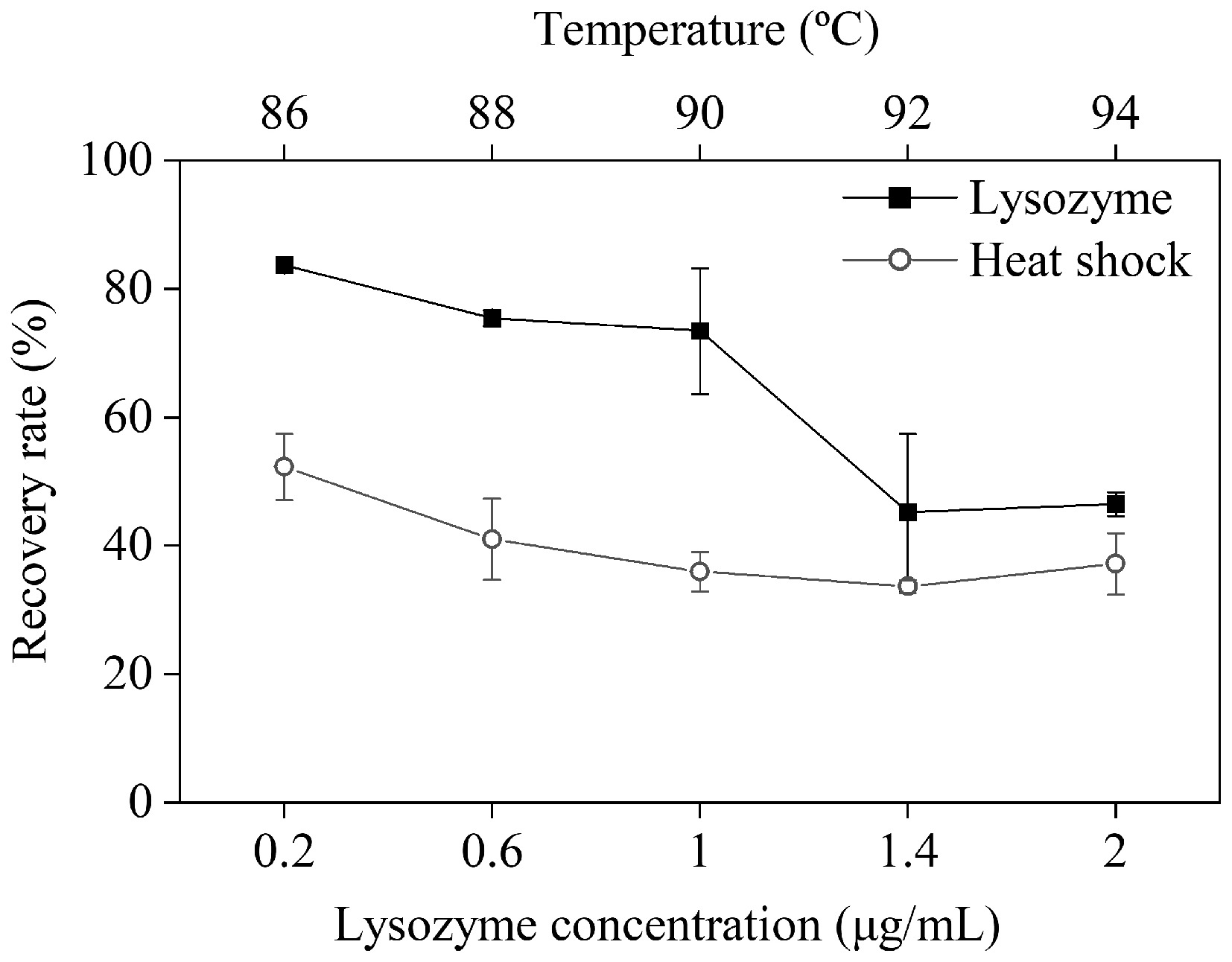

Different calcium salts have different solubilities in the culture medium, leading to differences in the release of calcium ions, which in turn, may affect the heat resistance of spores differently. Therefore, in this experiment, two water-insoluble calcium salts (calcium carbonate, calcium fluoride), and two water-soluble calcium salts (calcium chloride, calcium gluconate) were selected to prepare spore cultures. The four collected spores are hereinafter referred to as TS-CS (spores produced in calcium carbonate medium), F-CS (spores produced in calcium fluoride medium), L-CS (spores produced in calcium chloride medium), and PTT-CS (spores produced in calcium gluconate medium). As can be seen in Fig. 1, the fastest decrease rate of spore survivors was observed for L-CS, followed by PTT-CS, and the slowest decline was observed for TS-CS under heat treatment at 90 °C. This result aligns with the D90 °C measured for each spore (Table 1). TS-CS was the most heat resistant (D90 °C = 20.40 min), followed by PTT-CS (D90 °C = 18.09 min), with L-CS being the least heat resistant (D90 °C = 14.24 min). Due to the extremely low sporulation rate of C. sporogenes cultured in the calcium fluoride medium, sufficient spores cannot be obtained, so the heat resistance of spores produced in this medium could not be accurately determined. Calcium fluoride only interacts with concentrated strong acids, and hardly interacts with weak or even dilute strong acids[23]. Even though the spore medium had formed an acidic environment in the later stages of incubation[24,25], this environment is far from being sufficient to solubilize the calcium fluoride, and thus results in the failure of spore formation, or the formation of spores that can only take up a very small amount of Ca2+. During spore formation, Ca2+ participates in processes like peptidoglycan cross-linking in the cortex, aiding its stabilization and proper assembly to promote normal cortex formation[26]. Thus, Ca2+ deficiency in calcium fluoride-containing medium impaired spore formation, reducing sporulation rates of C. sporogenes. The few spores formed in calcium fluoride-containing media also exhibit low heat resistance. Conversely, calcium gluconate and calcium chloride are highly water soluble, which can release more Ca2+ under the same conditions, enabling faster uptake by spores and promoting Ca-DPA formation. As a key to spore core mineralization, Ca-DPA interacts with core proteins to enhance their thermostability, while facilitating core water excretion and binding free water, thereby boosting spore heat resistance[27]. Conversely, PTT-CS showed greater heat resistance than L-CS, likely because gluconic acid acts as a sporulation carbon source, driving spores into a more stable dormant state. Among water-insoluble calcium salts, calcium carbonate most significantly enhances spore heat resistance. This may result from the gradual accumulation of microbial metabolic organic acids during incubation, which slowly acidifies the medium and promotes the gradual dissolution of calcium carbonate—avoiding local high calcium ion concentrations that would cause osmotic imbalance. Additionally, dissolved carbonate ions further raised the pH of the medium, and spores formed at higher pH have been shown to exhibit stronger heat resistance[9]. However, the specific response mechanism of calcium ions and pH-regulated heat resistance of spores has not yet been clarified, which is worthy of further exploration.

Figure 1.

Survival curves of C. sporogenes spores produced in sporulation media with different calcium salts at 90 °C.

Table 1. The sporulation efficiency and D90 °C of C. sporogenes spores produced in sporulation media with different calcium salts.

Calcium salt Sporulation rate (%) D90 °C (min) Calcium carbonate 15.63 ± 0.25b 20.40 ± 0.72a Calcium fluoride 0.31 ± 0.00d − Calcium gluconate 47.64 ± 0.68a 18.09 ± 0.07b Calcium chloride 13.83 ± 1.57c 14.24 ± 0.63c Different letters mean there is a significant difference between values in the same column (p < 0.05). For the sporulation rate of C. sporogenes, the most spores were formed in the calcium gluconate containing sporulation medium with the highest sporulation rate of 47.64%, while in the rest of the media, this value did not exceed 20% (Table 1). On the one hand, this was attributed to the higher solubility of calcium gluconate, which resulted in the full release of calcium ions and a higher degree of uptake of calcium ions by the spores. On the other hand, gluconic acid both promoted bacterial propagation to establish a larger bacterial population for subsequent spore production and served as the primary energy source for the metabolic activities involved in spore formation. In addition, Cristiano-Fajardo et al.[25] investigated the effect of glucose-specific uptake rate on the sporulation rate of Bacillus velezensis and showed that the two main metabolic by-products of glucose (ethylidene glycol and butanediol) could reduce environmental acidification and thus promote spore formation. However, gluconate was less able to retard environmental acidification than carbonate, which may be the main reason for the greater heat resistance of spores produced in calcium carbonate-containing sporulation media. Therefore, the effect of anions contained in calcium salts on the formation of spores and their heat resistance cannot be ignored. In addition, calcium gluconate improves both heat resistance and sporulation rate of C. sporogenes compared to calcium carbonate and calcium chloride, so if more and higher heat-resistant conidia need to be obtained at the same time, this can be achieved by adding calcium gluconate.

In conclusion, compared with calcium fluoride, calcium carbonate, and calcium gluconate are more soluble and can effectively provide Ca2+ to satisfy the demand for calcium ions during spore production of C. sporogenes. Compared with calcium chloride, both calcium carbonate and calcium gluconate contain acid radical ions, which can delay the acidification of the environment when dissolved in the culture medium. Among these two calcium salts, carbonate is more capable of delaying acidification. Therefore, gluconate and its metabolites can increase the sporulation rate of C. sporogenes. to the greatest extent, while carbonate plays a more significant role in increasing the heat resistance of the spores.

Protein content and DPA release of C. sporogenes spores

-

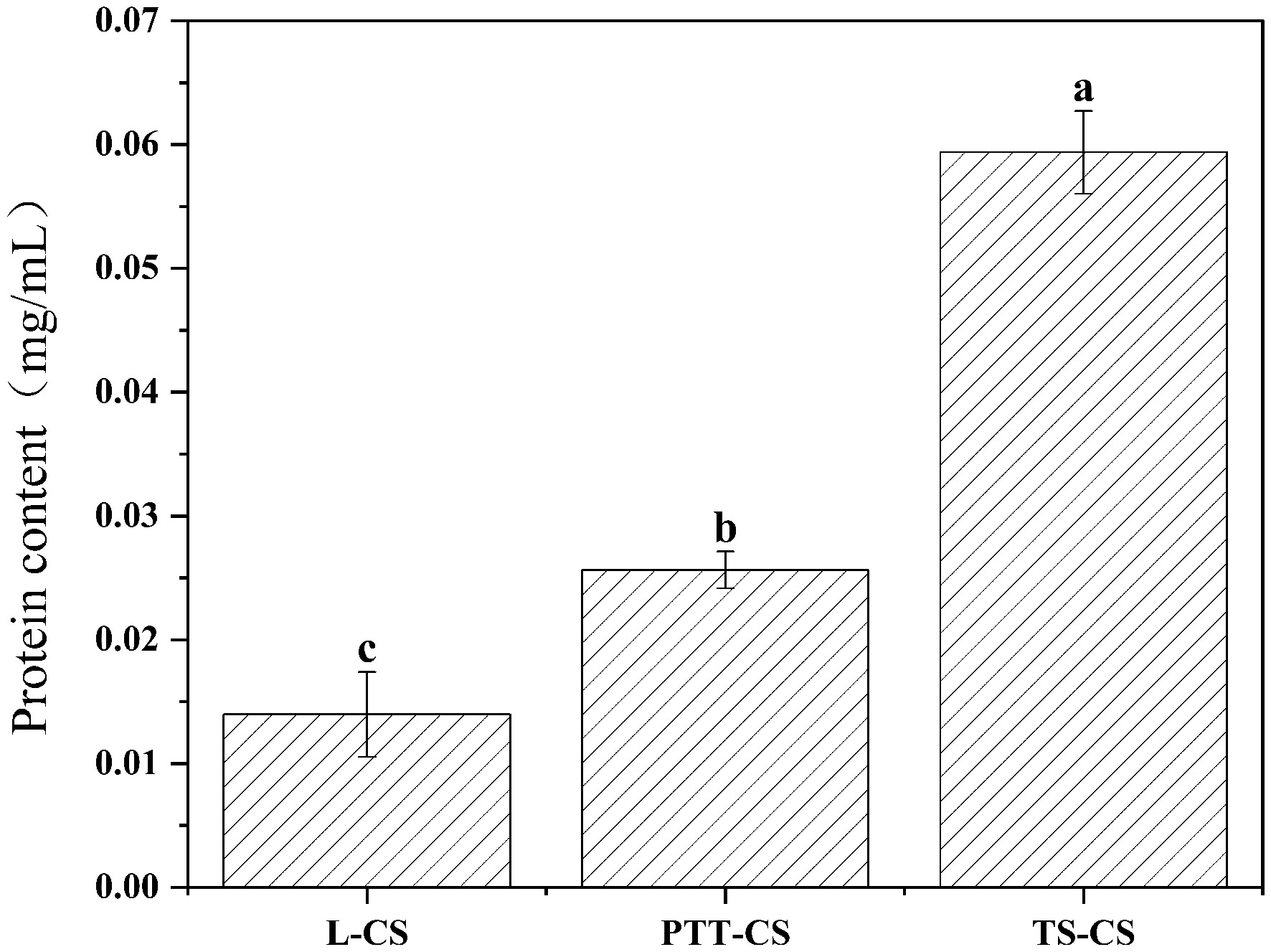

The coat and cortex are the outer layers of C. sporogenes spores. These two structures are composed of cysteine-rich proteins, while the spore core contains various essential heat-resistant proteins that contribute to thermal stability[28]. As shown in Fig. 2, the protein content of spores formed in the different sporulation media. Among the tested conditions, spores from the TS-CS group exhibited the highest protein concentration (0.059 mg/mL), correlating with the strongest heat resistance (Table 1). Spores from the PTT-CS group ranked second in both protein content and thermal tolerance, whereas the L-CS group showed the lowest protein content and weakest heat resistance. These results are consistent with findings by Malleck et al.[29], who reported that Moorella thermoacetica spores with greater heat resistance had more abundant and diverse proteins in the spore coat. This suggests that the elevated protein content in TS-CS spores may reflect more complete structural assembly and enhanced expression of key heat-resistant proteins during sporulation.

Figure 2.

The protein content of C. sporogenes spores produced in sporulation media with different calcium salts. L-CS: spores produced in calcium chloride medium; PTT-CS: spores produced in calcium gluconate medium; TS-CS: spores produced in calcium carbonate medium. Different letters indicate the significant differences in the protein content among different spores under (p < 0.05).

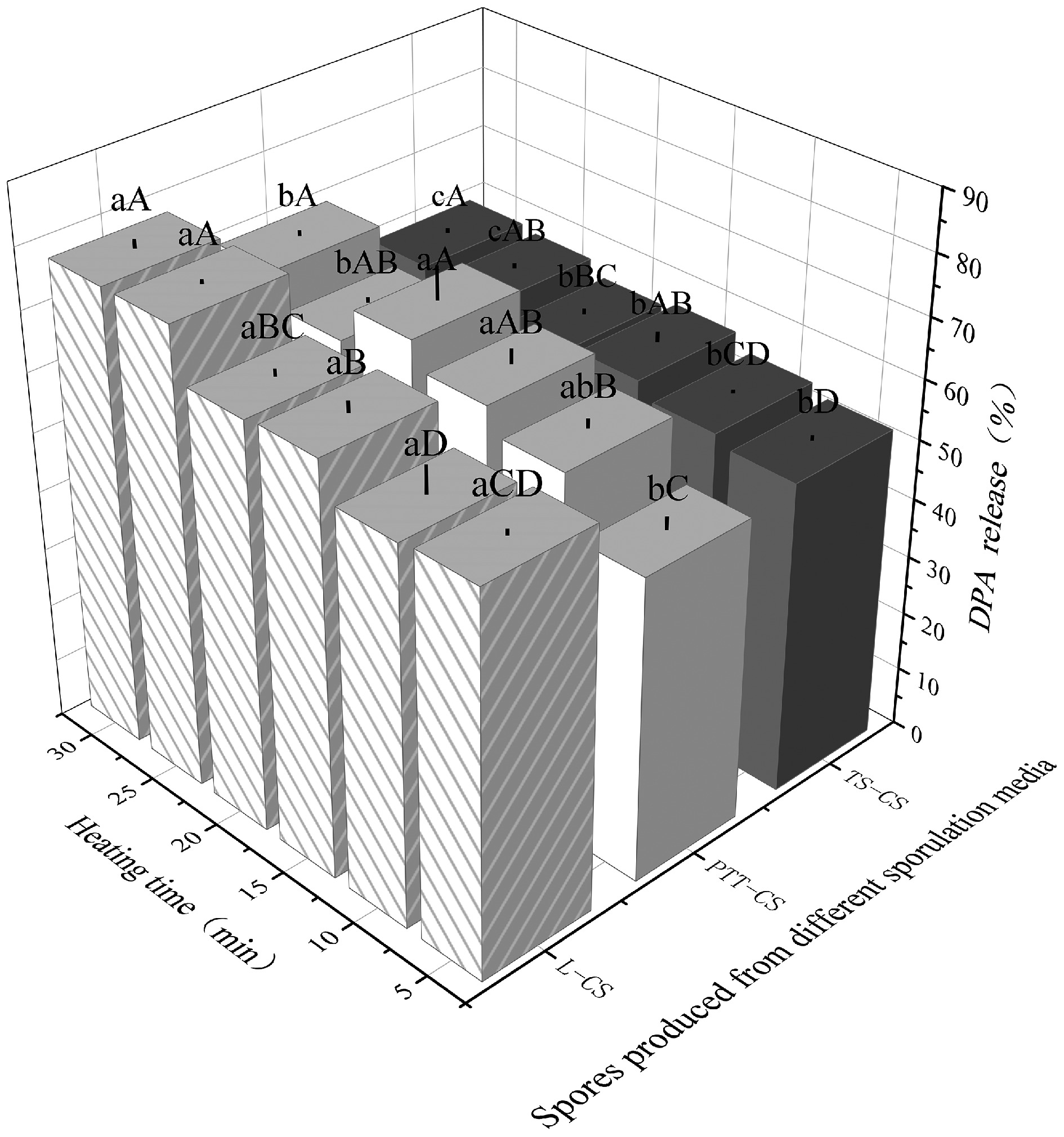

DPA is a hallmark component of the spore core and is another crucial determinant of spore heat resistance. During sporulation, DPA is rapidly synthesized and contributes to core dehydration and thermal stability. Furthermore, its chelation with Ca2+ ions forms a Ca-DPA, which enhances the thermostability of spore-associated enzymes[30]. Figure 3 illustrates the kinetics of DPA release from spores after heating for 30 min at 90 °C. Notably, TS-CS spores exhibited the slowest and least DPA release, whereas L-CS spores released DPA more rapidly and extensively. These differences imply that the inner membrane integrity of L-CS spores is more vulnerable to thermal disruption, and the resultant DPA loss likely exacerbates their reduced heat resistance. Tian et al.[31] demonstrated that calcium carbonate supplementation during sporulation can promptly elevate the pH of the culture medium into an optimal range, thereby stabilizing the outer spore structure and enhancing its protective functions. This may explain the improved structural integrity and thermal stability observed in spores formed in calcium carbonate–supplemented media. Additionally, calcium gluconate dissociates readily in solution, providing bioavailable calcium ions for spore uptake. Simultaneously, the gluconate anion undergoes hydrolysis, consuming hydrogen ions and increasing hydroxide ion concentration, thus mildly alkalizing the medium. This buffering effect delays acidification during sporulation and contributes to a more favorable environment for heat-resistant spore development.

Figure 3.

The DPA release of C. sporogenes spores produced by sporulation media with different calcium salts under heating (90 °C). Capital letters indicate significant differences in the DPA release of the same spores under different heating times, and lowercase letters indicate significant differences in the DPA release among different spores under the same heat treatment condition.

In summary, among the four calcium salts evaluated, calcium carbonate conferred the most significant improvement in spore heat resistance. It likely facilitates protein biosynthesis and promotes the formation of a robust spore structure capable of withstanding heat stress. Mechanistic data support that calcium carbonate also retards DPA release during thermal exposure and reduces overall DPA loss, thereby stabilizing the spore core and enhancing thermal resilience. In contrast, calcium gluconate showed a moderate protective effect, whereas calcium chloride was the least effective.

Optimization of spore purification conditions

Effects of lysozyme concentration on C. sporogenes spore structure and recovery rate

-

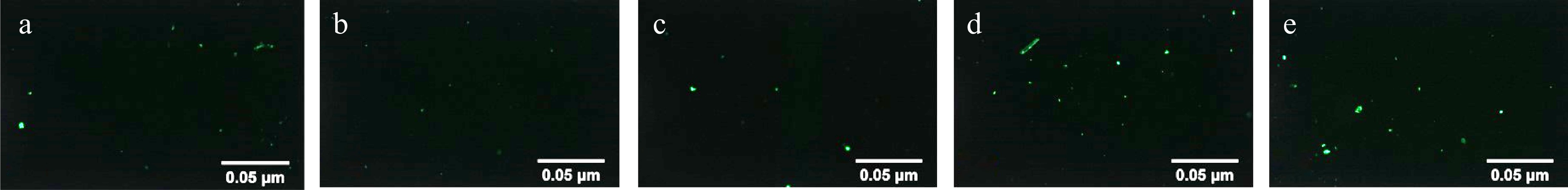

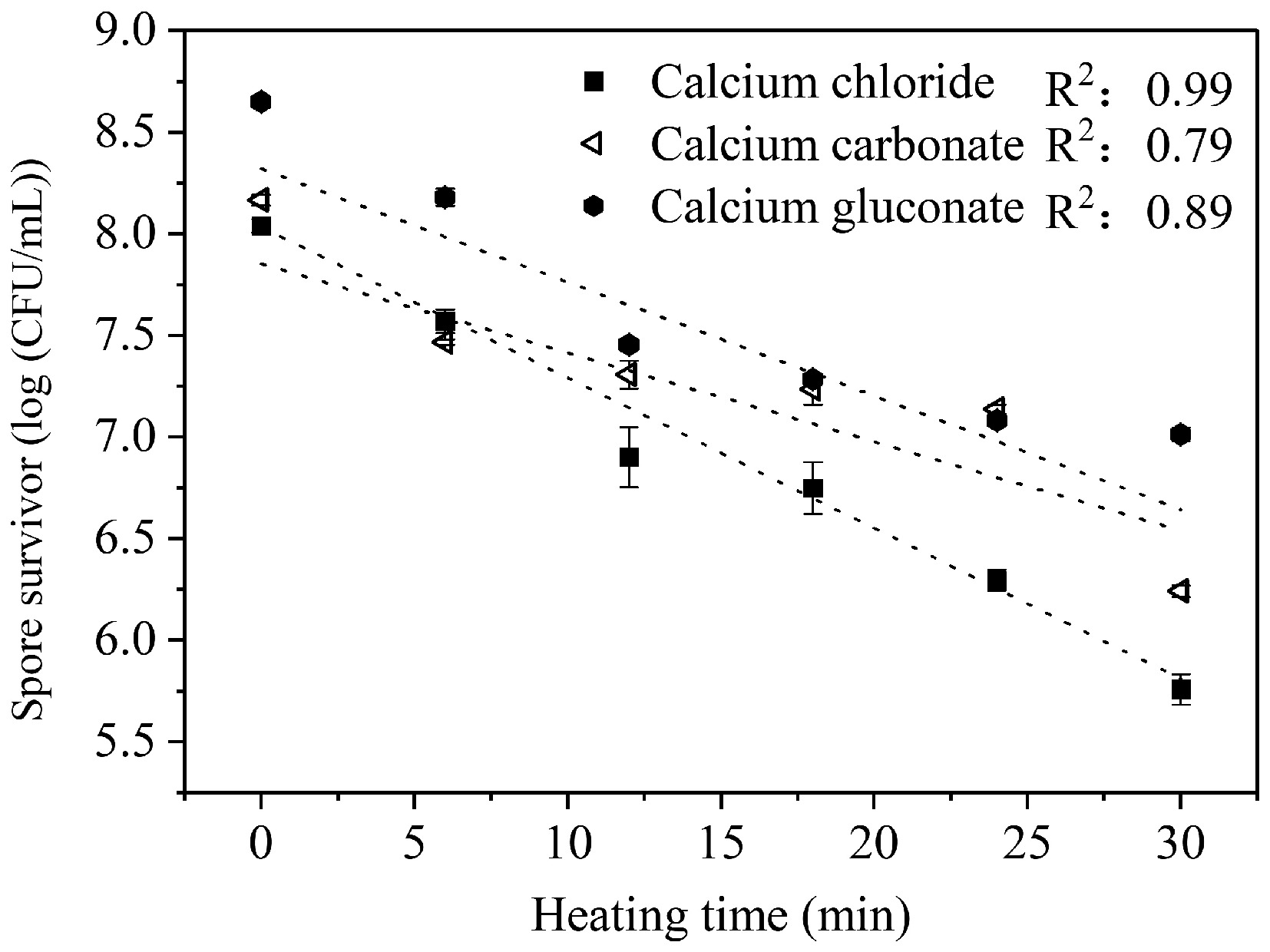

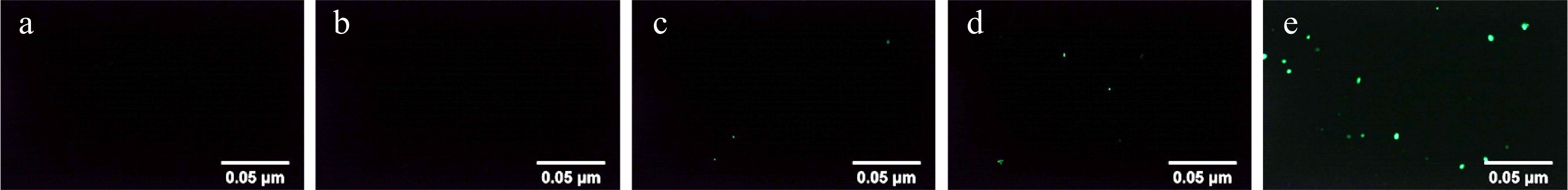

Residual vegetative cells and their fragments in spore suspensions may interfere with the accurate assessment of spore heat resistance. Lysozyme can degrade bacterial cell walls by hydrolyzing β-1,4-glycosidic linkages in insoluble peptidoglycans, leading to cell lysis and death[32,33]. In this study, lysozyme was used to remove residual C. sporogenes cells from their spore suspensions to obtain purified spores, and spores produced from calcium chloride-containing medium were used for purification. The survival of spores was then quantified to evaluate the effect of lysozyme concentration on spore structure and recovery rate. As shown in Table 2, lysozyme concentrations up to 1.0 μg/mL did not significantly affect spore viability. However, at 1.4 μg/mL, a marked reduction in viable spore count was observed, indicating structural damage and loss of spore viability at higher enzyme levels. These findings align with Liu[34]. It has been previously reported that lysozyme combined with high-pressure heat treatment could compromise the spore cortex of Bacillus subtilis, enhance inner membrane permeability, and synergistically improve sterilization efficacy. Thus, excessive lysozyme concentrations may disrupt the structure of C. sporogenes spores, rendering them more porous and facilitating the penetration of heat and water into the core, ultimately reducing heat resistance[35]. Moreover, lysozyme may interact with inner membrane proteins or lipids, increasing membrane permeability, and accelerating the leakage of core components. Structural alterations of spores under different lysozyme concentrations were further confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4). At 1 μg/mL, green fluorescence appeared in the field of view, while at 2 μg/mL, the fluorescence signal intensified significantly. This suggests that at higher concentrations, lysozyme induced membrane damage, allowing propidium iodide (PI) to penetrate the spore core and bind to nucleic acids. Spore recovery rates under varying lysozyme concentrations were also calculated (Fig. 5). The highest recovery (83.75%) was achieved at 0.2 μg/mL. Beyond this point, recovery declined progressively with increasing lysozyme concentration. At 1.4 μg/mL, recovery dropped below 50%, likely due to rapid lysis of susceptible spores under high lysozyme stress, with only highly resistant spores remaining.

Table 2. The survivors of C. sporogenes spores under different lysozyme concentrations and heat-shock temperatures.

Lysozyme Heat shock Lysozyme concentrations (μg/mL) Spore survivors [Log (CFU/mL)] Temperature

(°C)Spore survivors

[Log (CFU/mL)]0.2 8.66 ± 0.03a 86 8.45 ± 0.04a 0.6 8.63 ± 0.01a 88 8.35 ± 0.10ab 1.0 8.60 ± 0.09a 90 8.29 ± 0.07b 1.4 8.38 ± 0.14b 92 8.26 ± 0.02b 2.0 8.40 ± 0.02b 94 8.30 ± 0.09b Different letters mean there is a significant difference between values in the same column (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence PI staining of C. sporogenes spores under different lysozyme concentrations. (a) Lysozyme concentration was 0.2 μg/mL. (b) Lysozyme concentration was 0.6 μg/mL. (c) Lysozyme concentration of 1 μg/mL. (d) Lysozyme concentration was 1.4 μg/mL. (e) The concentration of lysozyme was 2 μg/mL.

In conclusion, when using lysozyme for the purification of C. sporogenes spores, the enzyme concentration should not exceed 1.0 μg/mL to maintain spore structural integrity and ensure a high recovery rate. Additionally, future research should prioritize elucidating the molecular interactions between lysozyme and inner membrane constituents to optimize spore purification protocols.

Effects of temperatures on spore structure and recovery rate of C. sporogenes

-

Spores exhibited exceptional heat resistance, enabling survival under high temperatures, whereas vegetative cells are rapidly inactivated by heat. Therefore, thermal treatment is widely employed for spore purification. However, variations in thermal tolerance across bacterial strains necessitate optimization of treatment temperatures based on target spore characteristics. For C. sporogenes spores, a conventional thermal treatment temperature of 90 °C has been established[10]. In this study, the effects of five temperatures (86−94 °C, with 90 °C as the central point) were systematically evaluated on spore recovery rate and structural integrity. As shown in Table 2, spore survivors decreased significantly when the treatment temperature increased from 86 to 90 °C, indicating that thermal exposure at 90 °C not only inactivates C. sporogenes but also induces lethality in its heat-sensitive spores. Structural damage to spores under varying thermal treatments is visualized in Fig. 6. The results demonstrated that thermal treatment inevitably caused structural damage to spores, with thermal lethality escalating as temperatures rose. Heated at 90 °C, the vast majority of residual bacterial cells die rapidly, and the spores retained in the bacterial cells are promoted to separate quickly. However, it will also kill heat-sensitive spores and damage part of the spore germination signal receptors (inner membrane proteins), thereby reducing the spore recovery rate. This phenomenon aligns with the findings by Wen et al.[36] on Bacillus subtilis spores. Their study revealed that B. subtilis spores exhibited thermal inactivation at 70 °C, activation coupled with damage to germination receptors at 75 °C, and exacerbated receptor impairment at 80 °C. Correspondingly, spore recovery rates declined progressively with increasing temperatures, with a marked attenuation in the decline in recovery rate above 90 °C (Fig. 5). This trend paralleled observations under lysozyme treatment, suggesting 90 °C serves as the demarcation temperature for heat-sensitive and highly thermotolerant C. sporogenes spores. At 90 °C, heat-sensitive spores are rapidly inactivated, while heat-resistant spores remain viable. These findings underscore the intricate relationship between thermal treatment temperature, spore germination activity, and purification efficacy. Excessive temperatures enhance spore purification but concurrently inflict structural and functional damage. Consequently, for the C. sporogenes spores cultivated under the experimental conditions herein, the optimal heat treatment temperature is 90 °C.

-

This study investigated the effects of sporulation media containing different forms of calcium salts on the sporulation rate of C. sporogenes and the heat resistance of its spores. Meanwhile, it evaluated the optimal heat-shock temperature and lysozyme concentration for spore purification to fill gaps in related research. Results showed that the solubility and anion type of calcium salts are key factors in regulating the sporulation rate of C. sporogenes and spore heat resistance. Specifically, calcium carbonate significantly enhanced spore heat resistance by promoting protein synthesis, and the spores produced with calcium carbonate showed the slowest release and the least amount of DPA during heating, which improved their heat resistance. Follow-up studies can be carried out to explore the differences in protein composition and metabolic pathways of spores produced in various calcium salt-containing media to better understand how calcium salts affect the heat resistance of C. sporogenes spores. Besides, this study also identified calcium gluconate as an ideal calcium source for C. sporogenes sporulation medium, which not only improves sporulation efficiency but also avoids interferences from water-insoluble calcium salts, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of experimental results. For spore purification, a lysozyme concentration of 1 μg/mL combined with a heat-shock temperature of 90 °C is suggested to effectively balanced the spore recovery rate and structural integrity. These findings provide important references for optimizing the spore preparation process and designing a sterilization process for vacuumed, low-acid foods.

We are grateful to the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20221020) for its financial support of this research.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, conceptualization, visualization: Zhang Y; data curation, methodology, writing—review and editing: Chen X, Li Y, Xu R, Wang Y, Zhan X; investigation, validation, writing—review and editing: Pan L, Tu K; conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing: Peng J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Chen X, Li Y, Xu R, Wang Y, et al. 2025. Effects of different calcium salts on the sporulation rate and spore heat resistance of Clostridium sporogenes. Food Materials Research 5: e017 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0017

Effects of different calcium salts on the sporulation rate and spore heat resistance of Clostridium sporogenes

- Received: 22 June 2025

- Revised: 05 August 2025

- Accepted: 15 August 2025

- Published online: 29 September 2025

Abstract: Clostridium sporogenes serves as a nontoxigenic surrogate for Clostridium botulinum in food thermal process design, requiring spores with high heat resistance and structural integrity. This study investigated the effects of four calcium salts on the sporulation rate and spore heat resistance of C. sporogenes CICC 8021. To further explore these effects, spore protein content and pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (DPA) release of the spores during heating were analyzed. Spore purification conditions were optimized by structural integrity and recovery rate to screen heat shock and lysozyme purification procedures suitable for this strain. Results showed that water solubility and the anion type of calcium salts are crucial to the sporulation rate and spore heat resistance of C. sporogenes. The highest sporulation rate (47.64%) was observed in the sporulation medium with calcium gluconate. The spores produced in the medium supplemented with calcium carbonate exhibited the highest heat resistance (D90 °C = 20.40 min), the highest protein content, and the least and slowest DPA release. The optimal lysozyme concentration for spore purification was determined as 1 μg/mL, and the optimal temperature for heat shock purification was 90 °C. This study systematically revealed the effects of different calcium salts in sporulation media on the heat resistance of C. sporogenes spores and the optimized strategy for spore purification, providing a theoretical basis for preparing highly uniform spores for scientific research and industrial use.