-

Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf (P. cocos), a dried sclerotium, is one of the initial 86 traditional Chinese medicines approved for functional food development in China[1]. Studies have identified a variety of bioactive compounds in P. cocos, including polysaccharides, triterpenoids, steroids, amino acids, and fatty acids[2]. Alkali-soluble polysaccharides (ASP) constitute the primary components of its dried mass[3]. These polysaccharides exhibit significant pharmacological properties, such as antioxidative, immunoregulatory, and anti-cancer effects[4]. Recent findings suggest that P. cocos polysaccharides can modulate gut microbiota by increasing Lactobacillus populations[5], and improve sleep quality through the γ-aminobutyric acid subtype A (GABAA) receptor during normal sleep states[6]. These findings support the potential use of P. cocos polysaccharides as prebiotic and sleep-enhancing agents.

Nevertheless, the limited solubility of ASP in water often results in their discard as herbal residues after processing, thereby restricting their application in food product development[7]. To enhance their functionality and health benefits, it is crucial to modify their physicochemical properties through various physical, chemical, or biological methods[8]. Recently, there has been growing interest in physical modification techniques due to their mild processing conditions and chemical-free nature[9]. Superfine grinding has been identified as a pivotal step in the pretreatment of materials during food processing. Superfine powders are characterized by superior physicochemical properties, including excellent fluidity, adsorption qualities, and nutrient solubility[10]. The application of different micronization technologies may also influence the characteristics of polysaccharides, thereby enhancing their biological activities and bioavailability[11]. For instance, Wang et al.[12] found that ball milling reduces the crystallinity of P. cocos pachyman, thus increasing its prebiotic potential.

Both dry and wet grinding are prevalent techniques employed in the preparation of superfine powders from food materials[13]. Presently, jet milling (JM) is recognized as one of the most widely utilized technologies for dry grinding[14], whereas high-pressure microfluidization (HPM) is emerging as a novel technique for wet grinding[15]. Research indicates that wet grinding often results in softer and more brittle tissue structures that exhibit a greater propensity for fracture compared to those processed through dry grinding[16]. Such differences may have implications for the physicochemical properties and bioactivity of the raw materials. However, the effects of dry and wet grinding pretreatments on P. cocos have not been well investigated.

Consequently, it is important to conduct a comprehensive study comparing the effects of different superfine grinding pretreatments on the physicochemical characteristics and biological activities of ASP. In this study, two types of P. cocos powders were produced using JM and HPM, which served as the materials for extracting alkali-soluble polysaccharides. The particle size, color, adsorption properties, and microscopic morphology of the P. cocos powders were analyzed. Additionally, the chemical composition, intrinsic viscosity, monosaccharide composition, prebiotic properties, and sleep-promoting activities of the ASPs were systematically compared. The structural changes of polysaccharides were evaluated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction. This research aims to enhance the processing and utilization of P. cocos, offering both a theoretical foundation and practical insights into the application potential of ASP pretreated by different superfine grinding methods.

-

P. cocos were collected from Yunnan province, China. Yeast extract, beef extract, de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar, and peptone were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 were supplied by Nestlé R&D (China) Co. Ltd (Beijing, China). The Escherichia coli OP50 (E. coli OP50) and wild-type N2 Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) strains were generously provided by Prof. Xiuqing Zhang (China Agricultural University, Beijing, China). All other reagents utilized were of analytical grade.

Pretreatment of P. cocos powder

Jet milling pretreatment (JM)

-

The P. cocos sample was superfine ground by jet milling (FI-11A, Beijing Collaborative Innovation Research Institute, China). The main engine operated at a frequency of 50 Hz, the classifier at 30 Hz, and the induced draft fan at 50 Hz. The powders were then sieved through a 100-mesh sieve.

High-pressure microfluidization pretreatment (HPM)

-

Initially, the P. cocos samples were uniformly suspended in distilled water (1:9, W/V). This suspension was pretreated using a coarse grinding machine (FG 2018, Beijing Collaborative Innovation Research Institute, China) to mitigate potential blockages in the HPM equipment. The pretreated suspension was subsequently processed under a high-pressure interaction chamber (FG-3037D, Beijing Collaborative Innovation Research Institute, Beijing, China) at 120 MPa. The resulting powder suspension was freeze-dried and stored for subsequent analysis.

Particle characteristics of P. cocos powder

Particle size distribution

-

The particle size distribution of the different P. cocos powders were assessed using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). Distilled water was used as the dispersing medium, with the refractive index set to 1.57. The software associated with the device was utilized to calculate the particle sizes corresponding to 10% (D10), 50% (D50), and 90% (D90) of the cumulative volume. Furthermore, the span of the particle size distribution was determined using the following equation:

$ S pan=\dfrac{D_{90}-D_{10}}{D_{50}} $ Color

-

Colorimetric analysis of P. cocos powders was conducted using a colorimeter (Lab Scan XE, Hunter Lab, USA). The L*, a*, and b* values of the samples were recorded using a white correction plate as a reference (L0* = 93.29, a0* = –1.24, b0* = –0.45). The color difference (ΔE) of the P. cocos powders was computed according to the following formula:

$ \Delta E=\sqrt{(L^*-L^*_0)^2+(a^*-a^*_0)^2+(b^*-b^*_0)^2} $ where, ΔE is the total color difference.

Water-holding capacity, oil-holding capacity, and swelling capacity

-

Following the methodology outlined by Xia et al.[17], with minor modifications, a sample of P. cocos weighing 1.0 g was combined with 30 mL of distilled water and heated at 60 °C for 30 min. The resultant residues were isolated through centrifugation at 25 °C (6,000 g for 15 min) and subsequently weighed. The water-holding capacity (WHC) was determined using the following formula:

$ WHC\;({\rm{g\cdot g^{-1}}})=\dfrac{M_2-M_1}{M_1} $ where, M1 is the weight (g) of the sample, and M2 is the weight (g) of the residue.

Utilizing the modified approach proposed by Luo et al.[18], a 1.0 g sample of P. cocos was mixed with 10 mL of vegetable oil and heated at 60 °C for 30 min. The residues were then collected via centrifugation at 25 °C (6,000 g for 15 min) and weighed. The oil-holding capacity (OHC) was calculated using the corresponding formula:

$ OHC\;({\rm{g\cdot g^{-1}}})=\dfrac{W_2-W_1}{W_1} $ where, W1 is the weight (g) of the sample, and W2 is the weight (g) of the residue.

The swelling capacity (SC) was determined following the methodology outlined by Yu et al.[19]. A 3.0 g sample of P. cocos powder was combined with 30 mL of distilled water. The initial volume of the mixture was recorded before it was placed in a water bath at 25 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the expanded volume of P. cocos powders was recorded. SC value was calculated using the following formula:

$ SC\;({\rm{mL\cdot g^{-1}}}) =\dfrac{V_2-V_1}{m}$ where, m is the weight of the sample, V1 is the initial volume (mL) of the mixture, and V2 is the expanded volume (mL) of the mixture.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

-

The microstructural differences in the P. cocos powders were examined using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SU3500, Hitachi, Japan). The powder samples were uniformly applied to double-adhesive carbon tape and coated with gold. Microscopic images were captured at an acceleration voltage of 5.0 kV, and magnifications of 500× and 2000×.

Alkaline extraction of P. cocos polysaccharides

-

The superfine ground powders of P. cocos underwent a defatting process using 80% ethyl acetate followed by acetone. This was followed by cold alkali extraction using 0.5 mol·L−1 NaOH at 25 °C for 20 h. The supernatant was collected and neutralized to pH 7.0 with 0.5 mol·L−1 acetic acid, resulting in precipitates that were washed five times with distilled water to remove any chemical residues. The polysaccharide solution was subsequently purified through dialysis using a bag with a molecular weight cutoff of 3,500 Da for 3 d. Ultimately, the ASPs were obtained via lyophilization.

Physicochemical properties of ASPs

Chemical composition analysis

-

The total carbohydrate, protein, and uronic acid contents in the ASPs were quantified using phenol-sulfuric acid[20], Bradford[21], and m-hydroxydiphenyl assays[22], respectively.

Monosaccharides composition analysis of ASPs

-

The monosaccharide compositions of the ASPs were analyzed using the 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP) pre-column derivatization method[23]. The ASPs (5 mg) were hydrolyzed with 3 mL of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, 2 mol·L−1) at 120 °C for 4 h. The hydrolysate was then evaporated three times at 50 °C with methanol to remove excess TFA. The resulting hydrolysate was dissolved in 500 μL of distilled water. Next, 250 μL of the acid-hydrolyzed sample and 250 μL of NaOH (0.6 mol·L−1) were added to the solution. Afterward, 500 μL of 0.4 mol·L−1 PMP was introduced, and the mixture was incubated in a water bath at 70 °C for 1 h. Once the solution had cooled to room temperature, it was neutralized with 500 μL of HCl (0.3 mol·L−1). The solution was then extracted three times with 1 mL of chloroform, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane before injection. Analysis was performed using an Xtimate C18 column (4.6 mm × 200 mm, 5 μm), with the column maintained at 30 °C. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (LC-20AD, Shimadzu, Japan) was conducted at a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1, with a mobile phase consisting of 0.1 mol·L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 6.7), and acetonitrile (87:13, v/v). Detection occurred at 250 nm and monosaccharide standards were used for comparison.

Determination of intrinsic viscosity

-

The intrinsic viscosity ([η]) of the ASPs dissolved in DMSO was measured using an Ubbelohde viscometer with a capillary diameter of 0.5–0.6 mm at a controlled temperature of 25 ± 0.1 °C. The [η] value was derived from the mean intercepts of the Huggins and Kraemer plots.

Fourier transfer-infrared spectrometry (FT-IR)

-

The chemical bonding characteristics of the ASPs were investigated using FT-IR spectroscopy (Spectrum100, Perkin Elmer, USA). A homogeneous mixture of ASP and KBr powders in a 1:100 ratio was prepared as tablets, with KBr alone serving as the blank background. The analysis was conducted over a wavenumber range of 4,000 to 400 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 scans.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

-

The XRD patterns of the ASPs were analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. Scanning was conducted over a diffraction angle (2θ) range of 5°–40° with increments of 0.02° and a scanning rate of 4° min−1. The crystallinity index (CI) of the ASPs was calculated using MDI Jade 6.0 software (Materials Data, Inc. USA).

Prebiotic activity of ASPs

-

Carbohydrate-free MRS broth, enriched with 0.05% (W/V) l-cysteine, served as the foundational medium to assess the potential of ASPs as carbon source alternatives for probiotic growth. LGG and BB-12 were employed as reference bacterial strains. GOS, a pre-established prebiotic, acted as a positive control. To establish an anaerobic environment, the medium was purged with nitrogen and subsequently sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min. The polysaccharides (ASPs and GOS) were then filter-sterilized and incorporated into the medium, achieving final concentrations ranging from 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 3.0% (W/V), respectively. Subsequently, active probiotics were inoculated into the MRS broth and incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h. Optical density (OD) measurements were conducted at a wavelength of 600 nm to evaluate growth.

The optimal concentration of polysaccharides was used as the exclusive carbon source, with GOS serving as a comparative reference. The assessment of probiotic growth involved monitoring turbidity at regular intervals of 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, and 48 h, under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. The OD values were measured at 600 nm to quantify growth.

Sleep-promoting activity of ASPs

-

C. elegans were cultivated on plates incorporating nematode growth medium (NGM) at 20 °C, and nourished with E. coli OP50. Synchronization of the population was accomplished through the utilization of the alkaline hypochlorite technique; wherein fertile adults were subjected to bleaching to extract eggs. Following a 48 h incubation period at 20 °C, these eggs matured into L4 larvae, which were subsequently employed for experiments.

Subsequently, the C. elegans were transferred to experimental plates containing E. coli OP50, further enriched with ASPs at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 μg·mL−1. Continuous sequential images were captured using an inverted microscope over 12 h. To quantify the motility of C. elegans, a frame-by-frame subtraction method was implemented utilizing custom MATLAB (MathWorks) scripts, as previously described by Busack & Bringmann[24].

Statistical analysis

-

All measurements conducted in this study were performed in triplicate, with results expressed as mean values ± standard errors. The statistical analyses were carried out utilizing Origin 2021 software (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA), whereas SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) was utilized to ascertain significant differences. The threshold for determining significant differences between samples was set at p < 0.05.

-

The average particle sizes of modified P. cocos powders are presented in Table 1. The parameters utilized for measuring the particle size included the average particle size (D50), as well as the equivalent diameters at cumulative volumes of 10% (D10), and 90% (D90). Furthermore, the span value, which evaluates the uniformity of the particle size distribution, has also been reported. The analysis indicated that the HPM-treated P. cocos exhibited a D50 value of 75.20 ± 0.09 μm and a span value of 1.69 ± 0.01. In contrast, the JM-treated P. cocos powder demonstrated a notably smaller particle size, with a D50 value of 31.60 ± 0.01 μm and a span value of 1.58 ± 0.01, suggesting a narrower particle size distribution and enhanced uniformity for the JM-treated samples.

Table 1. Particle size distribution of P.cocos powders.

Sample D10 (μm) D50 (μm) D90 (μm) Span JM-treated 13.70 ± 0.01a 31.60 ± 0.01a 63.70 ± 0.01a 1.58 ± 0.01a HPM-treated 22.47 ± 0.06b 75.20 ± 0.09b 149.20 ± 0.58b 1.69 ± 0.01b Note: Different letters superscripted in the results were significantly different at p < 0.05. Jet milling employs interparticle collisions or impacts against solid surfaces facilitated by compressed air or inert gas, which is frequently utilized to decrease the particle size or granularity of dried materials[25]. Prior research has indicated that the JM process is likely to yield micro-powders with relatively narrow size distributions[26]. Conversely, Li et al.[27] have documented that elevating the pressure and the number of cycles during HPM treatment led to a decrease in the particle size of insoluble dietary fiber. The reduction of particle size in powders using various micronization technologies may influence breakage efficiency, as well as the physicochemical and functional properties[28].

Color

-

Color is a significant quality attribute of food powders and plays a crucial role in influencing consumer acceptance of various food products. The color parameters of the P. cocos powder were assessed using different superfine grinding techniques, as presented in Table 2. The L* (lightness) value of the HPM-treated powders was recorded at 83.95 ± 0.10, which is lower than the 85.15 ± 0.01 observed for the JM sample, while the a* (redness), and b* (yellowness) values were found to be higher. This finding indicates that the application of HPM treatment potentially leads to a decrement in the lightness of P. cocos powders, while simultaneously augmenting its yellowness and redness. Fang et al. have reported that high-pressure micro-fluidization treatment significantly increased the color intensity of bamboo shoot fibers[29]. This enhancement can be attributed to the Maillard reaction that occurs during the HPM process at elevated temperatures[30]. On the other hand, the JM treatment likely improved the specific surface area by decreasing the particle size, thereby promoting enhanced light reflection and leading to an elevated L* value[31].

Table 2. The color difference of P.cocos powders.

Sample L* a* b* ΔE JM-treated 85.15 ± 0.01a 1.74 ± 0.01a 9.96 ± 0.04a 14.08 ± 0.04a HPM-treated 83.95 ± 0.10b 2.03 ± 0.02b 10.56 ± 0.07b 14.31 ± 0.15b Different letters superscripted in the results were significantly different at p < 0.05. The water-holding capacity (WHC), oil-holding capacity (OHC), and swelling capacity (SC)

-

WHC, OHC, and SC capacities are critical parameters utilized to evaluate the water or oil retention capabilities and functional properties of various materials. WHC denotes the maximum volume of water that a substance can absorb and retain, while OHC quantifies its ability to absorb and retain oil. SC measures the degree to which a substance can expand by absorbing water and increasing in volume[32]. Table 3 presents the WHC, OHC, and SC values for different P. cocos samples. The data indicates that the HPM-treated powder exhibited a significantly enhanced WHC (6.95 ± 0.27 g·g−1) compared to the JM-treated samples (3.47 ± 0.22 g·g−1), reflecting an increase of 100.29%. Additionally, the HPM-treated powder demonstrated a 16.13% greater SC (3.96 ± 0.11 mL·g−1) than the JM powder (3.41 ± 0.16 mL·g−1). In contrast, the JM-treated sample displayed a lower OHC value (1.41 ± 0.01 g·g−1) compared to the HPM powder (3.46 ± 0.02 g·g−1. The experimental outcomes underscore the effectiveness of HPM treatment in enhancing the water-holding and oil-retaining capacities of P. cocos powders. In comparison to the JM technique, the abrupt pressure release at the exit of the HPM chamber triggers the expansion of particles, resulting in the formation of micropores or voids within the fiber matrix and the disruption of the intricate structure of the cell wall. This alteration exposes additional hydrophilic sites within the cell walls, thereby boosting the hydration properties of the P. cocos powders[33]. This enhancement establishes HPM-treated powder as a potentially valuable functional ingredient that can reduce dehydration shrinkage, modify viscosity, texture, and mouthfeel, in addition to decreasing the caloric content of food products[34]. Additionally, Li et al.[27] suggest that HPM represents a promising technology for the preparation of fibers with improved OHC. The significant increase in OHC observed in the HPM-treated powder can be attributed to the enhanced porosity and increased surface area, which facilitate the physical retention of oil through capillary action[35]. This improvement has the potential to inhibit the dissolution of fats and the deterioration of quality during the processing of high-fat foods, and it could also contribute to the reduction of cholesterol levels[36].

Table 3. Water-holding capacity (WHC), oil-holding capacity (OHC), and swelling capacity (SC) of P. cocos powders.

Sample WHC (g·g−1) OHC (g·g−1) SC (mL g−1) JM-treated 3.47 ± 0.22a 1.41 ± 0.01a 3.41 ± 0.16a HPM-treated 6.95 ±0.27b 3.46 ± 0.02b 3.96 ± 0.11b Different letters superscripted in the results were significantly different at p < 0.05. SEM

-

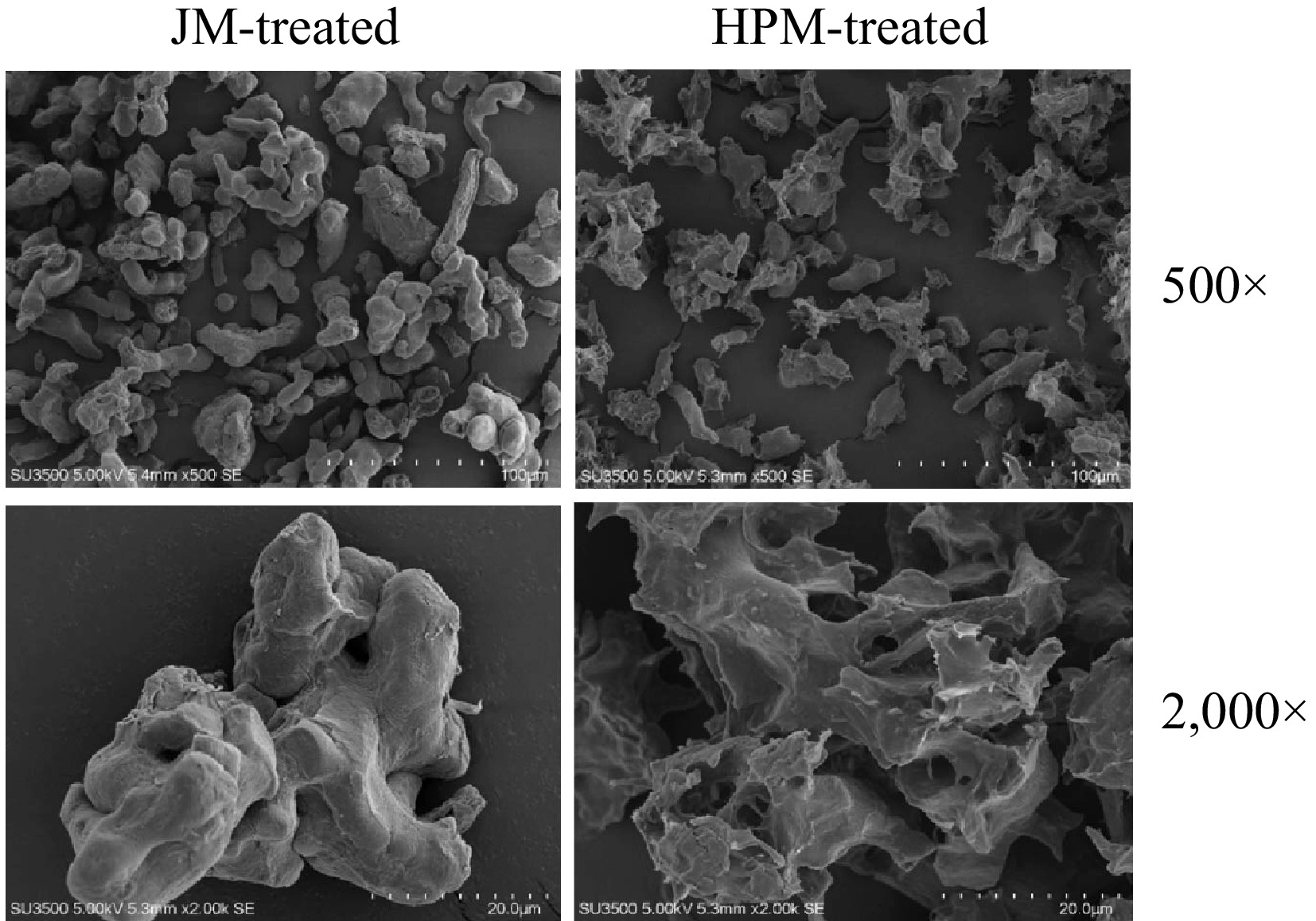

The microstructural characteristics of various samples of P. cocos were analyzed at magnifications of 500× and 2,000×, as depicted in Fig. 1. The sample subjected to JM exhibited an irregular spherical morphology, characterized by a smooth surface with minimal wrinkling. Conversely, the powders subjected to HPM treatment exhibited structural collapse within their microstructure, accompanied by the appearance of numerous minute voids. This morphological transformation after HPM processing could be ascribed to the abrupt decompression that occurs upon exiting the machine's interaction chamber, leading to particle fragmentation and expansion. This phenomenon resembles the microstructural alterations observed in insoluble dietary fiber from soybean residue[37]. Hence, it is reasonable to infer that this expansion contributes to the loosening of the particle's microstructure, thereby enabling the creation of pores or cavities within the particles.

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs of P. cocos powders with JM-treated and HPM-treated at different magnifications (500× and 2,000×).

The physicochemical characterization of ASPs

Yields and basic compositions

-

Table 4 shows the extraction yields and primary chemical components of the ASPs. HPM-ASP demonstrated a higher yield of 89.14% ± 1.70% (W/W), approximately 1.3 times that of JM-ASP. Microstructural analysis of the powder indicated that the HPM-treated powder possessed a looser structure with increased porosity, which may facilitate more efficient interactions between the powder and the extracting medium, thereby enhancing the extraction rate[38]. The total carbohydrate content, expressed as glucose equivalent, was found to be 91.23% ± 0.24% for JM-ASP and 94.56% ± 0.02% for HPM-ASP, indicating that carbohydrates constitute the predominant component in both extracts, with a slightly higher carbohydrate content in HPM-ASP. Huang et al.[39] also reported an increase in the total carbohydrate content of Mesona chinensis Benth polysaccharide following the HPM process. Furthermore, the protein contents were measured at 0.91% ± 0.01% for JM-ASP and 0.42% ± 0.02% for HPM-ASP. This observation is consistent with the lack of a peak at 1,541 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum, as illustrated in Fig. 2c[40].

Table 4. The chemical compositions and crystallinity index of crude ASPs.

Extraction yield (%) Total carbohydrate (%) Protein (%) Uronic acid (%) Crystallinity index (%) JM-ASP 78.75 ± 1.70a 91.23 ± 0.24a 0.91 ± 0.01a 2.56 ± 0.11a 14.20 ± 1.12a HPM-ASP 89.14 ± 4.67b 94.56 ± 0.02b 0.42 ± 0.02b 2.23 ± 0.08b 8.23 ± 0.85b Yield, (Weight of crude polysaccharide / Weight of P.cocos powder) × 100. Different letters superscripted in the results were significantly different at p < 0.05.

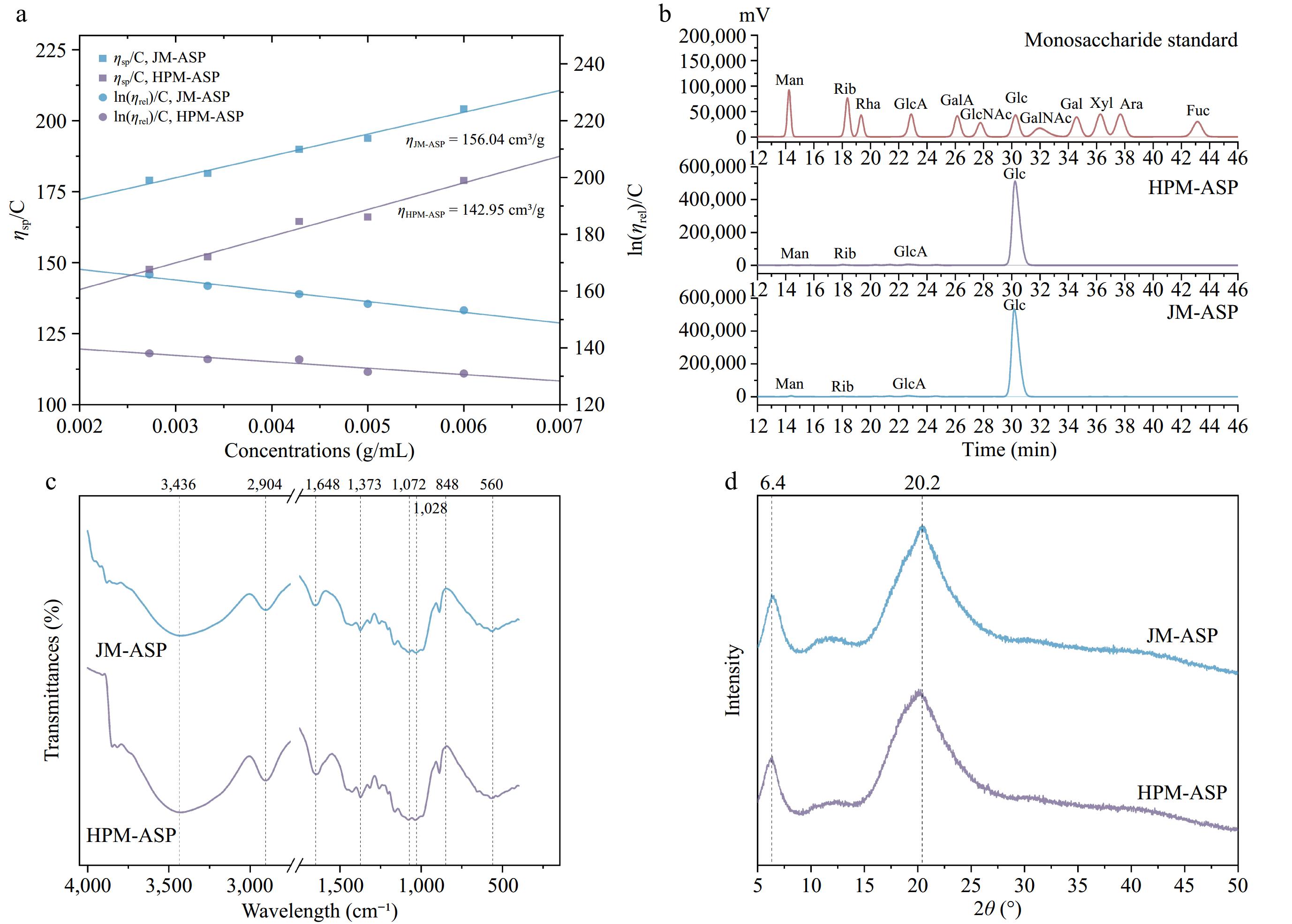

Figure 2.

Physicochemical properties and structural characterization of ASPs. (a) Intrinsic viscosity. (b) Monosaccharide composition. Peak identity: Man, mannose; Rib, ribose; Rha, rhamnose; GlcA, glucuronic acid; GalA, galacturonic acid; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; Glc, glucose; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Gal, galactose; Xyl, xylose; Ara, arabinose; Fuc, fucose. (c) FTIR. (d) XRD.

Intrinsic viscosities

-

Intrinsic viscosity ([η]) is a significant property of polysaccharides, representing the specific viscosity of a polymer solution as its concentration approaches zero[41]. This parameter is closely related to the molecular weight, chemical structure, and solvent quality of a polymer[42]. The intrinsic viscosities obtained were 156.04 cm3·g−1 for JM-ASP, and 142.95 cm3·g−1 for HPM-ASP (Fig. 2a). Polysaccharides derived from P. cocos through extraction with 0.5 mol·L−1 NaOH exhibit water-insolubility and a propensity to aggregate in aqueous NaOH solutions. This characteristic poses challenges for the application of the Mark-Houwink equation and the assessment of their molecular conformation. Chen et al.[43] formulated the Mark-Houwink equation specifically for alkali-soluble P. cocos polysaccharides in DMSO, which is expressed as η = 1.38 × 10−1 Mw0.54 (cm3·g−1). Using this equation, the molecular weights (MW) of JM-ASP and HPM-ASP were estimated to be approximately 4.51 × 105, and 3.84 × 105 Da, respectively. Research indicates that polysaccharides with lower molecular weights generally exhibit reduced intrinsic viscosity[44]. This observation aligns with findings from studies on Laminaria japonica[45] and Pinus koraiensis[46], which similarly revealed a decrease in viscosity associated with lower molecular weight of polysaccharides.

Monosaccharide compositions

-

Gas chromatography (GC) analysis results, as presented in Table 5 and Fig. 2b, revealed that JM-ASP and HPM-ASP were exclusively composed of glucose, indicating a homoglucan composition. This observation is consistent with previous research on ASPs extracted from a different cultivar of P. cocos sclerotium[47].

Table 5. Monosaccharide composition of the crude ASPs.

Monosaccharide composition (%) JM-ASP HPM-ASP Mannose 0.510 0.170 Ribose 0.205 0.520 Glucuronic acid 1.348 1.304 Galacturonic acid 0.098 0.075 Glucose 97.537 97.775 Galactomannan 0.084 0.016 Xylose 0.093 0.032 Arabinose 0.080 0.056 Fucose 0.045 0.051 FTIR

-

Figure 2c illustrates the FTIR spectra of the ASPs. The prominent absorption peak at 3,436 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the non-free O-H bond present within the sugar chain[48]. The absorption peak observed at 2,904 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibrations of glycomethyl and methylene C-H bonds[49]. Meanwhile, the peak at 1,648 cm−1 is associated with the asymmetric stretching of C=O bonds[50]. Within the spectral range of 1,200−1,000 cm−1, the peaks primarily correspond to ring vibrations, which overlap with the stretching vibrations of the C-O side groups and the vibrations of the C-O-C glycosidic bond[51]. The absorption at 1,072 cm−1 specifically indicated the presence of sugars in the pyranose form[52], while the characteristic absorption peak near 848 cm−1 suggested the presence of β-pyranose[53]. The results revealed that the positions and shapes of the absorption peaks of ASPs remained largely unchanged, with no emergence of new absorption peaks, which corroborates findings from studies on sweet potato starch processed through dynamic high-pressure microfluidization[54].

XRD

-

As illustrated in Fig. 2d, the peak patterns of the different ASPs were consistent, with two characteristic crystal peaks observed at approximately 2θ = 6.4° and 20.2°, indicative of polysaccharide characteristics associated with an amorphous structure[55]. This finding aligns with the study conducted by Fang et al.[29], suggesting that HPM modification did not alter the crystalline structure of the fiber samples. However, following HPM treatment, the diffraction peak at 20.2° exhibited a broader shape and decreased height, indicating the disruption of crystalline regions characterized by a dense structure and high density[56]. Compared to JM-ASP, the crystallinity index of HPM-ASP decreased from 14.21% ± 1.12% to 8.22% ± 0.85% (Table 4), signifying an increase in the proportion of amorphous regions with disordered molecular arrangements.

The biological activities of ASPs

Prebiotic activity

-

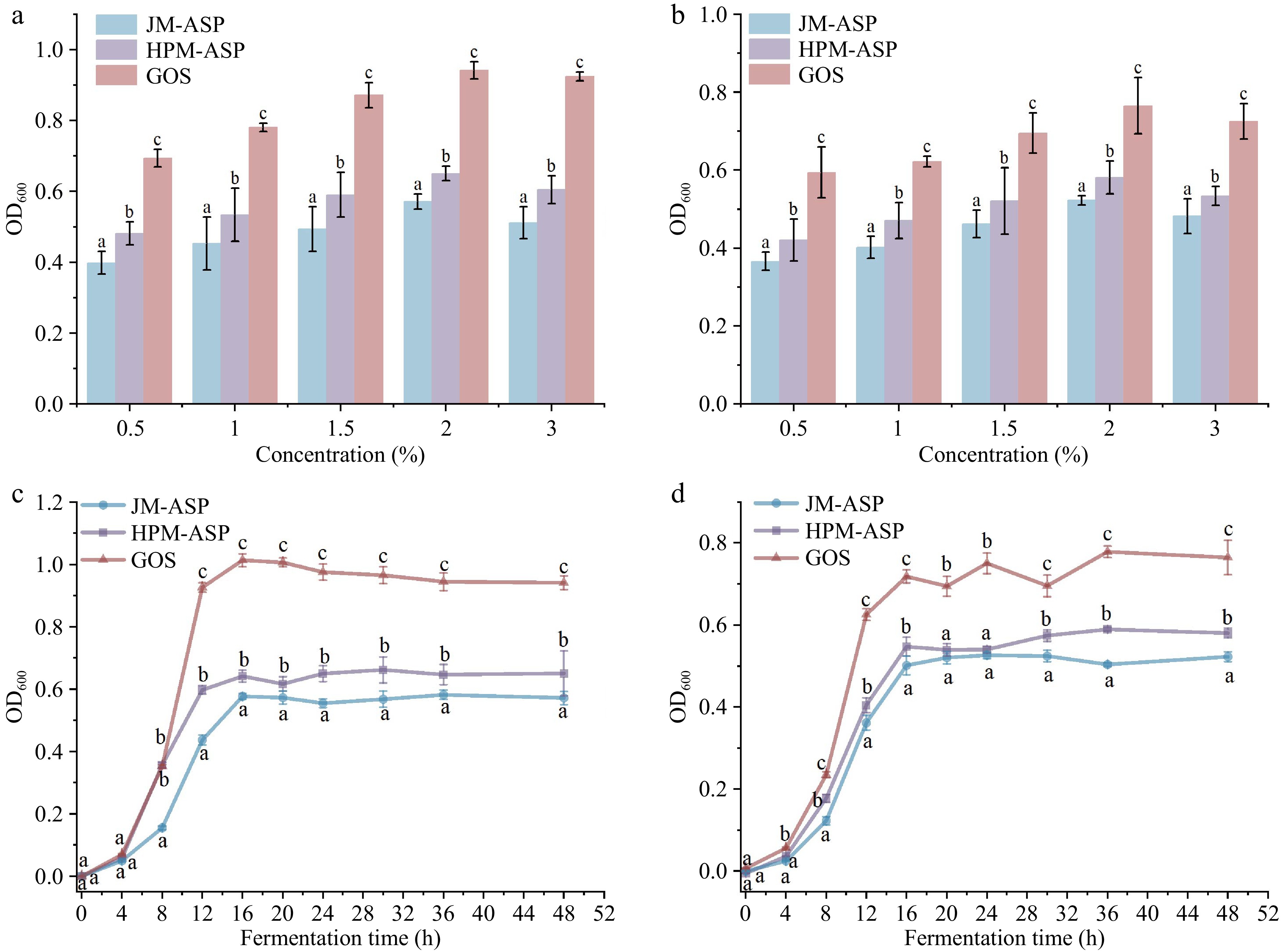

The effects of different concentrations of JM-ASP and HPM-ASP on the growth of probiotic strains are illustrated in Fig. 3a and b. OD values serve as indicators of microbial populations within the fermentation broth, thereby elucidating the growth dynamics of intestinal microflora. The observed alterations in these values reflect the variability in the proliferation of probiotic strains. These findings indicate that both probiotic strains, LGG and BB-12, can utilize ASPs as carbon sources for growth. This observation corroborates prior studies that demonstrated the efficacy of water-insoluble polysaccharides derived from P. cocos in modulating the gut microbiota by modifying its composition and enhancing the population of Lactobacillus species[57]. Notably, 2% ASPs and GOS exhibited the most beneficial effects on the proliferation of probiotic strains. This aligns with the existing literature, suggesting that the influence of polysaccharides isolated from longan pulp on probiotic growth is not contingent upon concentration[58]. This phenomenon may be explained by the increased osmotic pressure and metabolite accumulation associated with higher sugar concentrations, which ultimately restrict the proliferation of Bifidobacteria[59].

Figure 3.

Effect of GOS and ASPs on the prebiotic activity. (a) Proliferation of LGG after 48 h. (b) Proliferation of BB-12 after 48 h. (c) Growth curves of LGG over 48 h. (d) Growth curves of BB-12 over 48 h.

Figure 3c and d presents the growth curves of the two probiotic strains supplemented with 2% ASPs. The incorporation of polysaccharide samples as exclusive carbon sources in the basal medium significantly enhanced microbial proliferation. Initially, the growth rate remained stable for approximately 8 h, followed by a rapid increase that culminated in a peak growth at 16 h. Thereafter, the growth rate exhibited a gradual decline until the conclusion of the 48 h. Notably, the application of GOS led to the most substantial growth rates in the LGG and BB-12 strains. As illustrated in Fig. 3c and d, HPM-ASP exhibited more pronounced growth-promoting effects than JM-ASP (p < 0.05). The observed differences in bioactivity may be attributed to variations in physicochemical properties. The sugar content of polysaccharide prebiotics is critical for modulating probiotic growth[60]. The stimulatory effect of HPM-ASP was particularly pronounced, likely due to its higher sugar content than that of JM-ASP. Additionally, probiotics often proliferate more efficiently in non-digestible carbohydrates characterized by lower molecular weights[61]. In contrast, the proliferative potency of ASPs was relatively inferior to GOS, potentially due to their larger molecular weights. Furthermore, Fang et al.[29] reported that fibers subjected to HPM treatment demonstrated an enhanced capacity to stimulate bacterial growth, possibly attributed to a decrease in molecular weight after HPM treatment. Viscosity also plays a significant role in the prebiotic activity of the polysaccharides. Polysaccharides with lower viscosity exhibit superior dispersibility in solution, facilitating extensive molecular chain extension and offering more active sites for probiotic-secreted carbohydrate-degrading enzymes[62]. Moreover, the crystallinity of polysaccharides can modulate their prebiotic efficacy. Wang et al.[12] observed that the P. cocos pachyman pretreated by ball milling resulted in a decrease in crystallinity, thereby enhancing its degradation and subsequent utilization by intestinal bacteria.

Sleep-promoting activity of ASPs

-

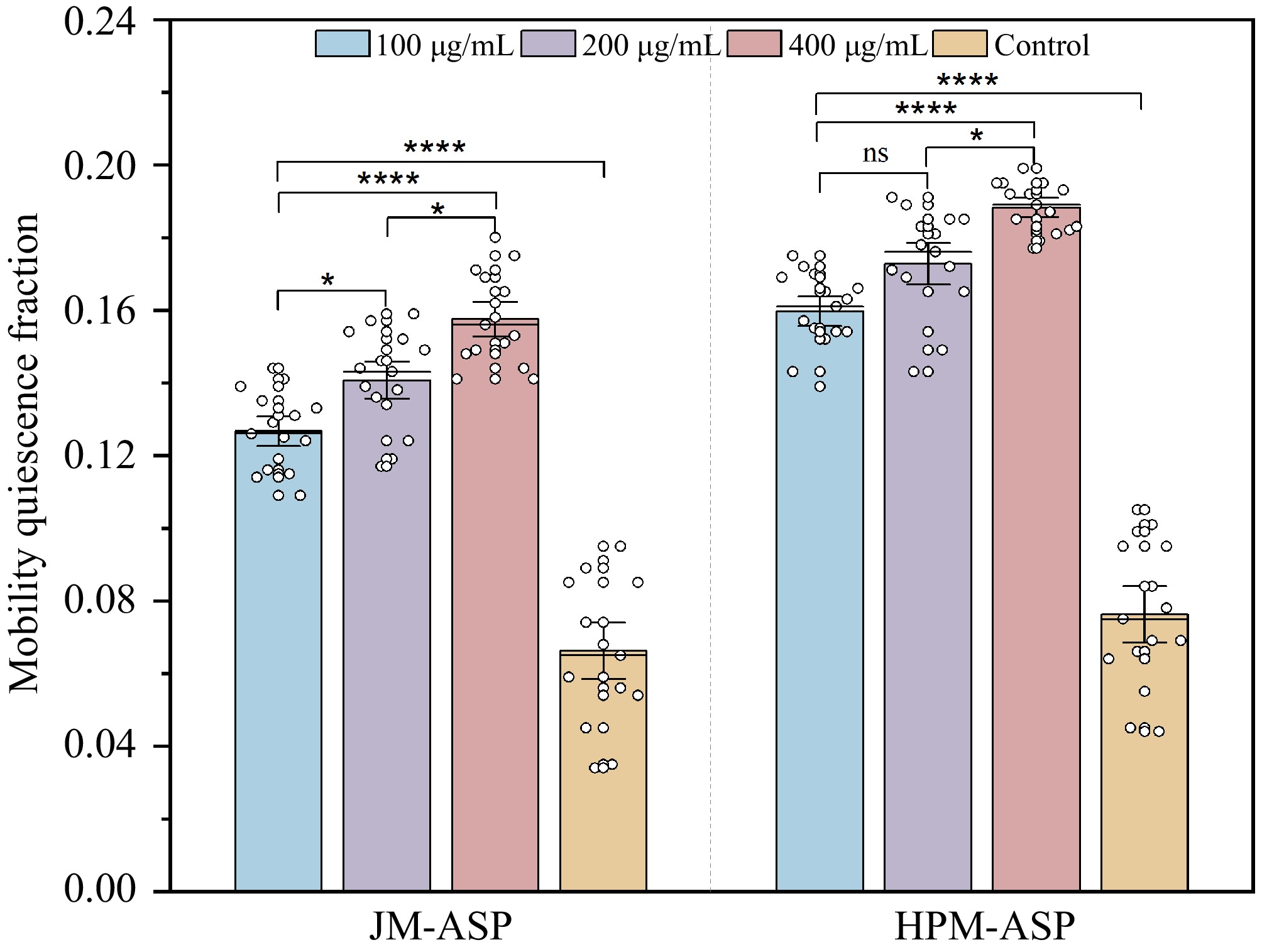

C. elegans has been selected as a model organism to explore the impacts of different ASPs on sleep patterns in vivo. Compared to the control group, the findings revealed that C. elegans fed with JM-ASP and HPM-ASP displayed elevated mobility quiescence fractions across the 100, 200, and 400 μg·mL−1 concentrations in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 4). Notably, HPM-ASP demonstrated a superior sleep-promoting effect compared to JM-ASP at equivalent doses. At the highest dose of 400 μg·mL−1, the sleep-enhancing activities of JM-ASP and HPM-ASP surpassed those of the control group by 1.38 and 1.84 times, respectively. Chen et al.[63] similarly documented that casein hydrolysates extended sleep duration in mice in a dose-dependent fashion.

Figure 4.

Mobility quiescence fraction of JM-ASP and HPM-ASP in C. elegans exposed to different concentrations. Values are presented as the mean ± SD, and the data were analyzed by ANOVA using SPSS 25.0, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and ns (not significant) p > 0.05.

P. cocos has traditionally been utilized as a food ingredient due to its diuretic and sedative properties, especially in Southeast Asian countries, where it is widely recognized as a safe and effective treatment for insomnia[64]. Research has demonstrated that polysaccharides derived from P. cocos can facilitate the modulation of gut microbiota to generate short-chain fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which function as prebiotics[7]. These fatty acids play a crucial role in activating the vagus nerve and influencing the gut-brain axis, thereby impacting the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the hypothalamus, which are associated with enhanced sleep quality[65]. The molecular weight of polysaccharides is a critical factor influencing gut microbiota regulation. Li et al.[66] found that blackberry polysaccharides (BBP-24) with lower molecular weights (247.62 kDa) exhibited greater fermentability compared to BBP-8 (408.13 kDa) and BBP (603.59 kDa), resulting in increased gas production and enhanced carbohydrate consumption rates. These findings suggest that low molecular weight polysaccharides are more effective in modulating gut microbiota, which in turn influences central neurotransmitter levels and contributes to improved sleep quality. Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms underlying the sleep-promoting effects of ASPs require further exploration.

-

Alkaline-soluble polysaccharide (ASP) is identified as the primary bioactive component of P. cocos, but it is frequently discarded as a byproduct during the processing of P. cocos due to its insolubility in water. The findings revealed that powders treated with high-pressure microfluidization (HPM) exhibited superior WHC, OHC, and SC in comparison to those subjected to jet milling (JM). The HPM treatment resulted in significant deformation and rupture of the cell walls, thereby facilitating the dissolution of polysaccharides. Additionally, the ASP derived from HPM pretreatment demonstrated an increased total carbohydrate content, alongside a decrease in intrinsic viscosity and crystallinity index relative to JM-ASP. The increase in prebiotic activity of HPM-ASP was correlated with these modifications. Furthermore, the crude ASPs improved the mobility quiescence fraction of C. elegans in a dose-dependent manner, with HPM-ASP exhibiting a more pronounced effect on sleep promotion. The improved physicochemical properties of the HPM-treated powder and its polysaccharide indicate their considerable potential as innovative functional ingredients for food development, offering enhanced health benefits. Consequently, HPM pretreatment is proposed as an effective approach for producing P. cocos powder and ASP with improved technological and health-promoting properties. Given that this study employed only a single microfluidization condition, further research is necessary to explore the impact of varying microfluidization parameters on these properties.

This work is financially supported by Nestlé R&D (China) Ltd (202204810610659).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: project administration, conceptualization: Jia X; data curation, formal analysis: Li J; writing - review and editing: Yin L, Jia X; funding acquisition: Jia X; validation, visualization: Li J; writing - original draft: Li J; resources: Liao Y, Xiang H, Phimolsiripol Y; supervision: Liao Y, Xiang H, Phimolsiripol Y, Yin L, Jia X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Yin L, Liao Y, Xiang H, Phimolsiripol Y, et al. 2025. Effects of different superfine grinding pretreatments on the physicochemical and biological properties of Poria cocos powder and its polysaccharide. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 437−445 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0034

Effects of different superfine grinding pretreatments on the physicochemical and biological properties of Poria cocos powder and its polysaccharide

- Received: 10 December 2024

- Revised: 08 March 2025

- Accepted: 10 March 2025

- Published online: 11 October 2025

Abstract: In this study, Poria cocos (P. cocos) powders were produced utilizing different superfine grinding techniques, specifically jet milling (JM), and high-pressure microfluidization (HPM). Alkali-soluble polysaccharides (ASP) were subsequently extracted from the pretreated P. cocos powders, designated as JM-ASP and HPM-ASP, respectively. This study aimed to examine the effects of JM and HPM pretreatments on the particle characteristics of P. cocos powders and physicochemical properties, prebiotic, and sleep-promoting activities of ASPs. Results revealed that the different superfine grinding methods significantly influenced the characteristics of the P. cocos powders and polysaccharides. The powders processed by JM exhibited a smaller particle size (31.60 μm) and a higher brightness value (L* = 85.15). In comparison, the HPM-treated powders exhibited superior water-holding, oil-holding, and swelling capacities, and displayed a more porous structure with prominent wrinkling, relative to those treated with JM. The ASPs obtained by different pretreatments possessed similar functional group structures, with over 97% composed of glucose. Furthermore, in comparison to JM-ASP, the extraction yield and total carbohydrate content of HPM-ASP increased by 13.19% and 3.65%, respectively. HPM-ASP displayed a significantly lower intrinsic viscosity (142.95 cm3·g−1) and crystallinity index (8.23%) relative to JM-ASP, which exhibited values of 156.05 cm3·g−1 and 14.86%, respectively. Besides, HPM-ASP displayed enhanced biological activities, including in vitro prebiotic effects and in vivo sleep-promoting properties. These results provide a theoretical basis for the development of P. cocos-based food products and support the application of alkali-soluble polysaccharides in the functional food industry.