-

Hydrocarbon fuel combustion constitutes an integral process in industrial boilers, internal engines, and propulsion systems[1,2]. Soot, a byproduct of incomplete combustion of hydrocarbon fuels, serves as a direct indicator of inefficient combustion[3]. Soot emissions from a device adhere to airborne particulates like dust then migrate via air currents, compromising air quality, inducing respiratory damage, and exacerbating global climate change[4]. Therefore, it is imperative to elucidate the soot formation process and its control mechanisms in flames and develop clean combustion technologies to promote environmentally sustainable energy utilization[5].

Oxygen-enriched combustion involves elevating the oxygen concentration in combustion systems to optimize the process. This method enhances efficiency through higher flame temperatures and accelerated reaction rates, enabling efficient energy conversion and significant reductions in pollutants. Escudero et al.[6] experimentally investigated the effects of the oxygen index (OI) on soot formation and temperature in ethylene reverse diffusion flames. They observed that flame radiation loss varied linearly with the oxygen concentration, mirroring the trends of the soot volume fraction (SVF). Chu et al.[7] performed numerical simulations of propane laminar diffusion flames under varying oxygen concentrations, and analyzed the flames' temperature and combustion products. They found that the flame temperature rose with increasing oxygen concentrations, increasing the peak flame temperature. Additionally, Chu et al.[8] analyzed the impact of oxygen concentration on ethylene laminar diffusion flames, revealing that increased oxygen levels reduced flame height. Flame temperature exhibited a bimodal distribution, which grew more distinct with this increase. Bukar et al.[9] applied noninvasive diagnostics to investigate the influence of O2/CO2 and O2/N2 atmospheres on flame height, structure, and soot formation in methane oxy-fuel laminar diffusion flames at atmospheric pressure. The results revealed that the oxygen concentration had a nonlinear influence on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) levels, subsequently modulating soot formation. Gong et al.[10] investigated the influence of direct current electric fields on OH* and CH* chemiluminescence in methane oxygen laminar diffusion flames. The results demonstrated that under oxygen-enriched combustion conditions, the electric field enhanced CH* transport and expanded its spatial distribution. Wu et al.[11] compared simulations based on Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) and KAUST PAH Mechanism 2 (KM2) mechanismsagainst gas chromatography-based experimental data across varying oxygen concentrations, revealing the differential sensitivity of intermediate species to oxygen levels in both the centerline and radial directions. Zhang et al.[12] studied the effects of oxygen enrichment in a constant volume combustion chamber on the velocity of syngas laminar combustion. The analysis of chemical and thermal effects demonstrated that increased oxygen concentration produced a linear rise in the laminar combustion velocity. Zhang et al.[13] investigated thermochemical interactions by adding CO2 and H2O to oxygen-enriched ethylene diffusion flames, examining their impact on soot suppression and flame dynamics. The laminar burning velocity of ammonia was modest, measuring only 7 cm/s under ambient conditions, yet in pure oxygen environments, its combustion rate increases to the m/s range[14]. Similarly, Guo et al.[15] demonstrated through experimental and numerical analyses that increases in the oxygen enrichment coefficient exhibited a direct correlation with the laminar burning velocity of hydrogen/ammonia mixtures. Higher oxygen enrichment coefficients corresponded to increased laminar combustion rates.

Combustion exhaust is the primary source of soot, necessitating exhaust aftertreatment technologies such as diesel particulate filters (DPFs) and catalyzed diesel particulate filters (CDPFs) during operation to preserve operational longevity[16,17]. Optimizing the fuel and oxidizer supply constitutes a reliable technology for reducing carbon emissions. The combustion environment within internal combustion engines is complex and influenced by the operating conditions, complicating accurate predictions of soot formation processes. Laminar diffusion flames serve as a benchmark for simulating the combustion processes in these engines. Fuentes et al.[18] examined variations in flame height, soot formation, and oxidation processes along the centerline and radial positions of ethylene laminar co-flow diffusion flames within 17%–35% oxygen concentrations. Their results revealed that above 25% oxygen concentration, the growth rate of maximum soot volume fraction markedly declined. Hua et al.[19] experimentally analyzed the impacts of fuel-side and oxidant-side oxygen enrichment on ethylene laminar diffusion flames. They observed that oxidant-side oxygen enrichment induced a linear reduction in flame height with increasing oxygen, whereas fuel-side oxygen addition had a minimal influence on flame height. Building upon conventional internal combustion engines, dual-fuel engines have garnered significant attention[20,21]. In laboratory settings, n-heptane serves as a common gasoline surrogate for vehicle engine research[16,22,23]. Ou et al.[24] developed a simplified mechanism to predict combustion performance in ammonia/n-heptane dual-fuel engines, employing n-heptane as a diesel-mimicking single-component fuel. Wen et al.[25] integrated optical diagnostics and numerical simulations to analyze NOx and unburned NH3 emissions from ammonia/n-heptane combustion. Their findings revealed that unconsumed NH3 persisted in low-temperature zones during the late combustion stages, resulting in unburned NH3 emissions, whereas elevated cylinder temperatures effectively suppressed the release of N2O and unburned NH3. The natural gas–diesel dual-fuel combustion strategy represents a highly promising approach for achieving ultra-low emissions and efficient combustion in the transportation sector[26]. Investigating soot formation under elevated pressures holds substantial practical relevance, as it directly replicates the operating conditions of critical components including internal combustion engines and gas turbines, whereas pressure fundamentally modifies the key soot formation mechanisms[16]. Wang et al.[27] examined the distribution of soot in methane/n-heptane dual-fuel laminar diffusion flames across varying pressures, revealing a positive correlation between increased pressure and elevated SVF.

The influence of dual-fuel combustion systems and oxygen-enriched combustion technology on the analysis of soot emissions was summarized above. However, research on soot formation using methane/n-heptane dual-fuels at different oxygen concentrations is still lacking. A high-pressure environment significantly enhances the collision frequency of fuel molecules and promotes the generation and aggregation of soot precursors, leading to increased soot emissions. High-pressure soot data are essential for understanding and mitigating emissions from practical combustion systems. Oxygen-enriched combustion can accelerate the fuel oxidation process and reduce incomplete combustion products by increasing the oxygen concentration. By combining the two methods, it can be seen how oxygen enrichment under high pressure inhibits the nucleation and growth of soot by changing the flames' structure and chemical pathways. This research was based on laminar diffusion flames and analyzed the flames' characteristics and differences in soot formation of methane/n-heptane mixed fuel with different oxygen concentrations on the oxidant side. The microprocesses of soot particle initiation, surface growth, and oxidation were simulated, revealing the dynamic mechanism. This research provides a theoretical basis for controlling soot emissions in dual-fuel internal combustion engines through oxygen-enriched combustion, and is of great significance for the development of efficient and clean combustion equipment. This study deepened the understanding of the mechanism of soot formation in complex combustion systems by coupling three major variables: high pressure, oxygen enrichment, and dual fuel. The present results not only assist the development of efficient and clean combustion technologies but also provide key theoretical support for optimizing industrial combustion processes under peak carbon and carbon neutrality goals.

-

This study presents numerical simulations of the flame structure, soot formation, and oxidation processes in methane/n-heptane laminar diffusion flames at 2 atm. The laminar diffusion flame model was developed using the CoFlame code[28], the accuracy of which is validated in prior work[27,29]. Detailed transport equations, sectional soot models, and radiation models have been documented in the literature[28]. The gas-phase chemical mechanism employed herein[30] used simplified gasoline/diesel surrogate reaction pathways, encompassing 175 species and 1,086 reactions, with PAHs extending to five-ring structures. Within the CoFlame framework, soot nucleation was modeled via collisions among three five-ring PAHs-benzo(a)pyrene (BAPYR), secondary benzo[a]pyrenyl (BAPYR*S), and benzo(ghi)fluoranthene (BGHIF) with β set to 0.0001[28].

This study assumed that soot nucleation occurred via collisions among pyrene (A4), BAPAYR, and BGHIF, with the parameter β set to 0.002. The results demonstrated closer agreement with the peak SVF reported in the reference[28]. The sectional method employed in the soot model utilized 35 sections with a spacing coefficient of 2.35, which sufficed to ensure minimal variation in the average soot morphology parameters with increasing section counts.

Calculation conditions

-

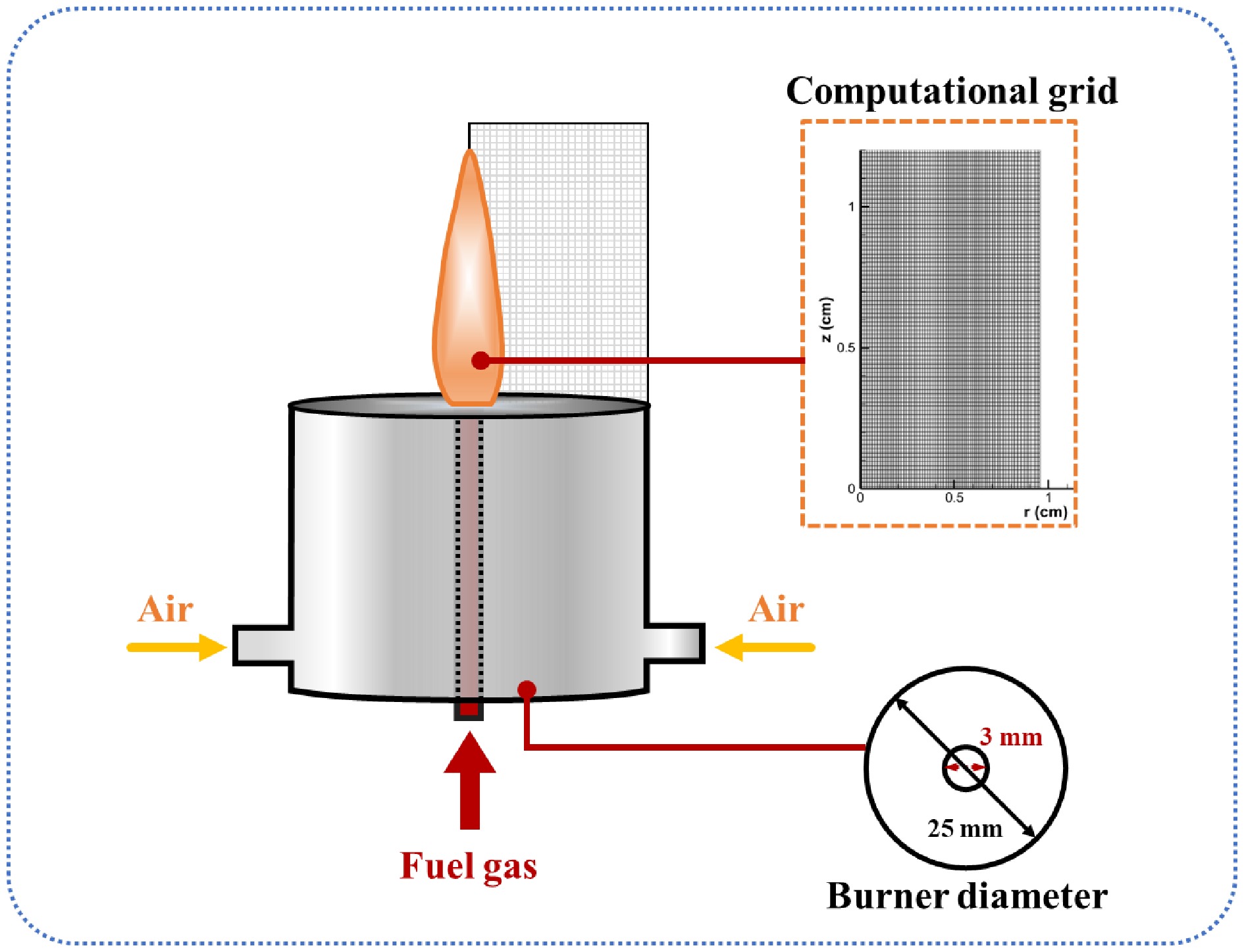

The CoFlame code[28] was used for numerical simulations, solving mass, momentum, energy, and gas-phase species conservation equations in an axisymmetric cylindrical coordinate system. Figure 1 illustrates the burner's structure and flame calculation domain. Under constant a carbon flow rate, methane/n-heptane dual-fuel issued from a vertical steel pipe (inner diameter: 3 mm), while air flowed through the annular region between concentric pipes (inner diameter: 25 mm). The total carbon mass flow rate of the fuel mixture was maintained at 0.41 mg/s, with vaporized n-heptane constituting 7.5% of the total carbon mass. The mass flow rates were 0.51 mg/s (CH4; molar fraction: 0.9872) and 0.036 mg/s (n-heptane; molar fraction: 0.0128). Co-flowing air was supplied at 340 mg/s, with fuel and air outlet temperatures of 523 and 473 K. Considering the oxygen-rich combustion costs and operational range, the oxidant oxygen concentration varied from 21% to 37%, defined as the oxygen index [OI = O2/(O2+N2)]. Radiation source terms were computed using the discrete coordinate method[7]. Detailed conditions are summarized in Table 1. Given the minimal hydrogen blending effects on the SVF in methane/n-heptane flames at 2 atm[27], all calculations were performed at this pressure.

Table 1. Calculated operating conditions.

Cases OI

(%)Fuel (CH4 + n-heptane) Air (O2 + N2) Inlet velocity

(cm/s)Temperature

(K)Inlet velocity

(cm/s)Temperature

(K)1 21 9.35 523 46.09 473 2 25 9.35 523 38.71 473 3 29 9.35 523 33.37 473 4 33 9.35 523 29.33 473 5 37 9.35 523 26.16 473 To ensure the simulation's accuracy, a rectangular grid of 1.0 cm in the radial direction (r) and 1.8 cm in the axial (z) direction covered the flame domain, while a nonuniform grid optimized computational efficiency. As shown in Fig. 1, a fine mesh was applied near the flame's surface, with a coarser mesh in distant regions. Convergence was achieved when the maximum relative change in temperature and SVF over 1,000 iterations fell below 1 × 10−4.

-

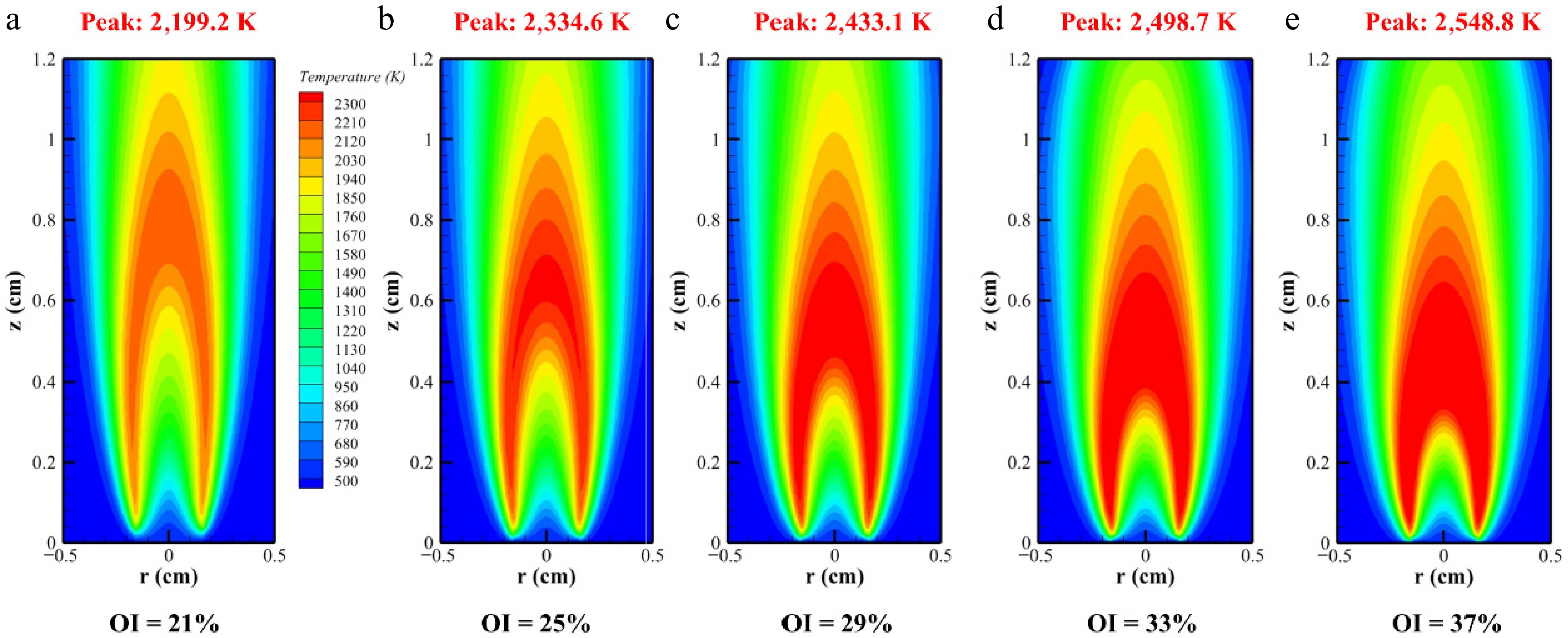

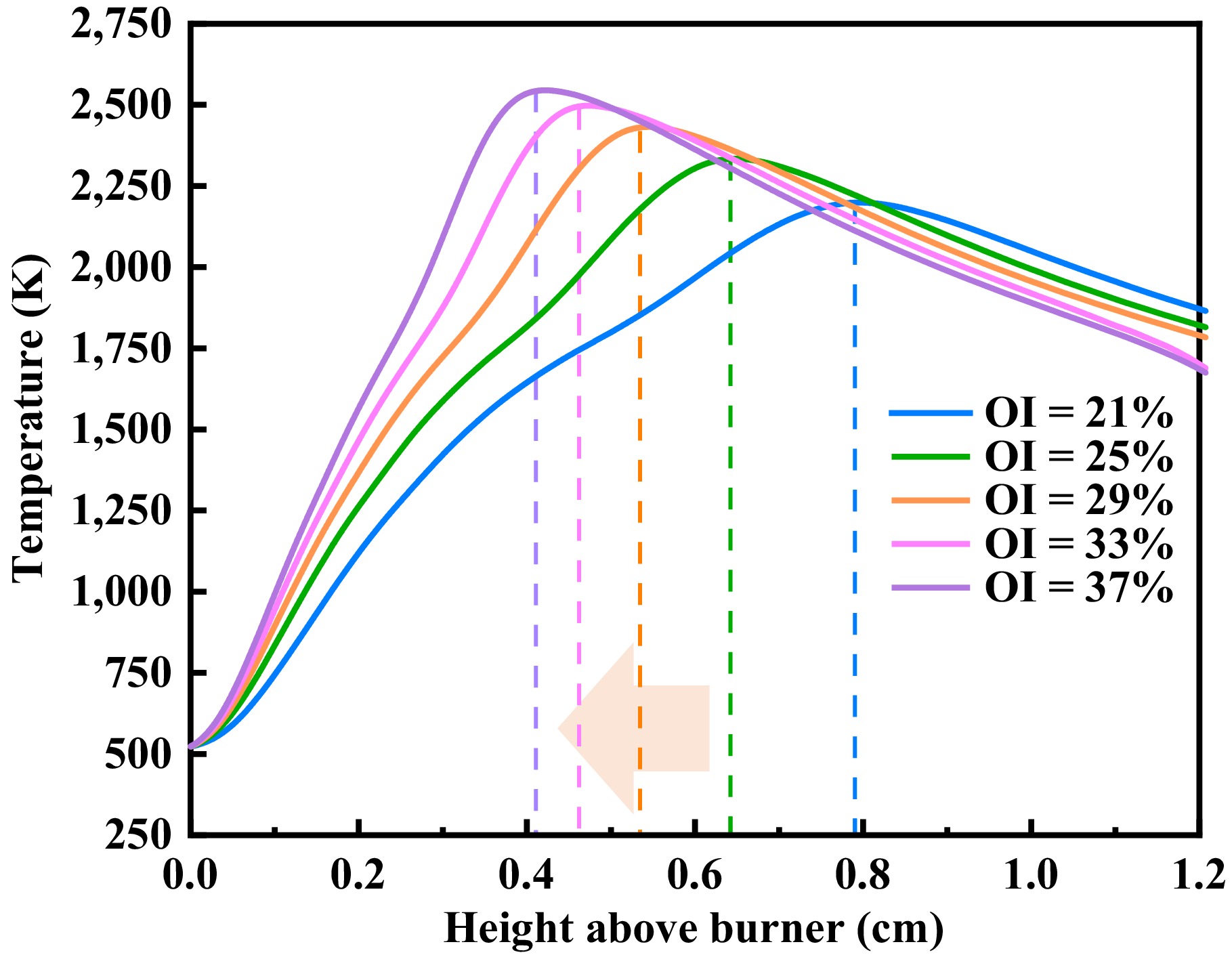

Figure 2 illustrates the flame distribution of methane/n-heptane dual-fuel under varying OI conditions at 2 atm. As the OI increased, flame height decreased significantly, whereas the high-temperature reaction zone expanded progressively, accompanied by a corresponding rise in the peak flame temperature. This increase in temperature from 21% to 37% oxygen concentration correlated with accelerated chemical reaction rates, flame front thinning, and reaction zone concentration, consistent with the Burke–Schumann theory. Notably, the high-temperature zone of the methane/n-heptane flame expanded markedly with increasing OI, particularly compared with the OI = 21% baseline. Since soot formation is intrinsically linked to flame temperature, these observations provide critical guidance for subsequent soot formation studies. The high-temperature zone was predominantly concentrated within the radial range of 0.05–0.9 cm, as depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 3 presents the axial temperature distribution curves of the flames. The peak temperature increased with a rising oxygen concentration, while its location progressively shifted toward the nozzle. This indicated that elevated oxygen levels promoted earlier and more concentrated reactions of methane/n-heptane dual-fuel, consistent with prior findings[7]. Figure 3 reveals that elevated oxygen content enhances the flame temperature at upstream positions. Conversely, at downstream locations (e.g., Height above burner = 1.2 cm), increased oxygen levels reduced the diffusion flame temperatures. This phenomenon occurred because higher oxygen concentrations accelerated premature fuel pyrolysis and expanded radical pools during combustion, leading to more complete combustion and greater fuel consumption at the flame terminus compared with low-oxygen conditions. Peak flame temperatures rose systematically with oxygen enrichment: 2,199.2, 2,334.6, 2,433.1, 2,498.7, and 2,548.8 K. Concurrently, the high-temperature zones of methane/n-heptane flames shifted progressively upstream as the OI increased, migrating from 0.7875 to 0.6375, 0.5325, 0.4575, and finally 0.4125 cm. Notably, below these high-temperature points, flame temperature decreased with a rising OI in the atmosphere. Overall, an increased oxygen volume fraction intensified combustion reactions near the nozzle, ultimately shortening the flame propagation length.

Figure 3.

Flame temperature distribution of different OIs along the flames' center axis for n-heptane/methane fuel at 2 atm.

Distribution of the SVF

-

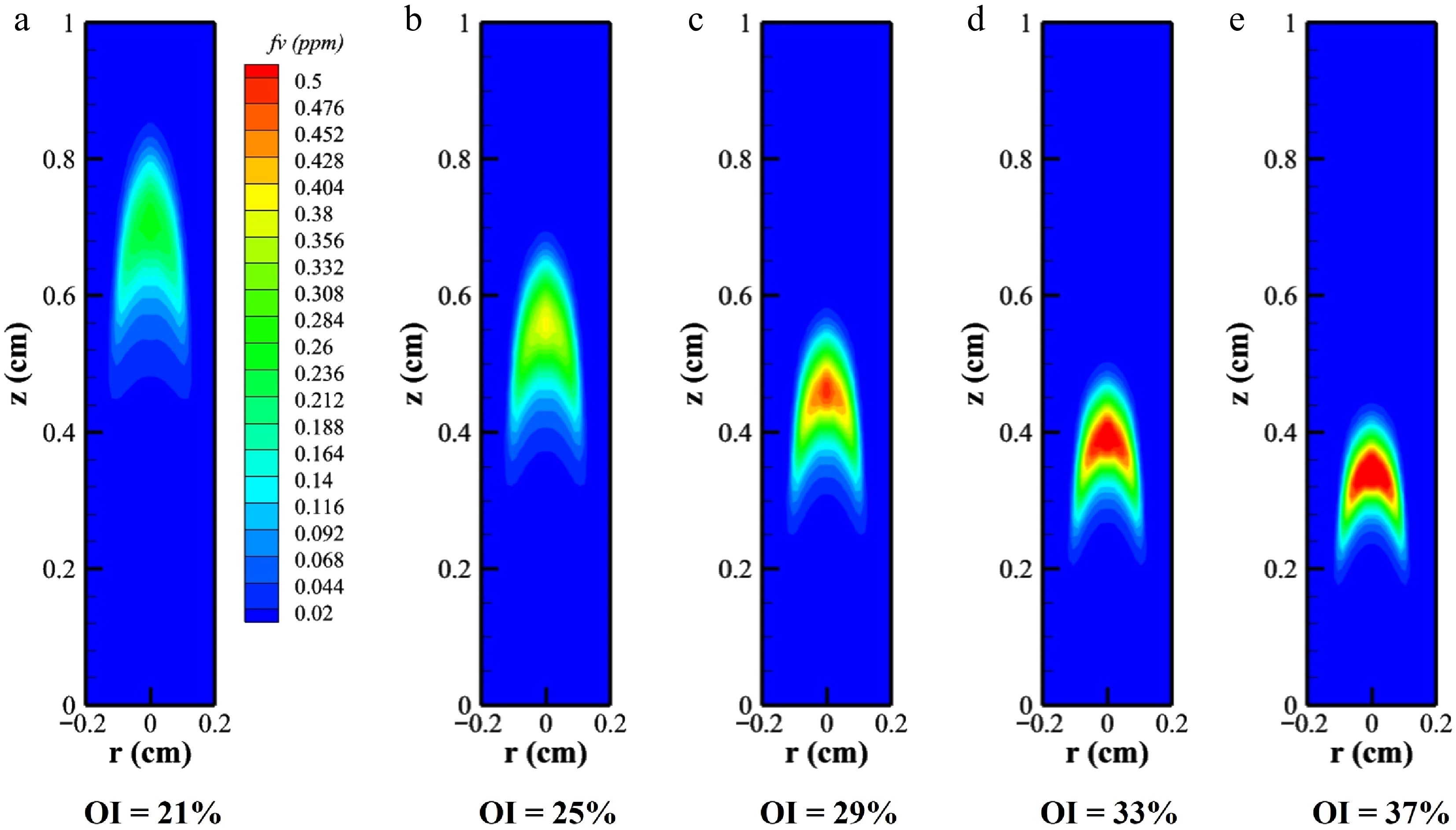

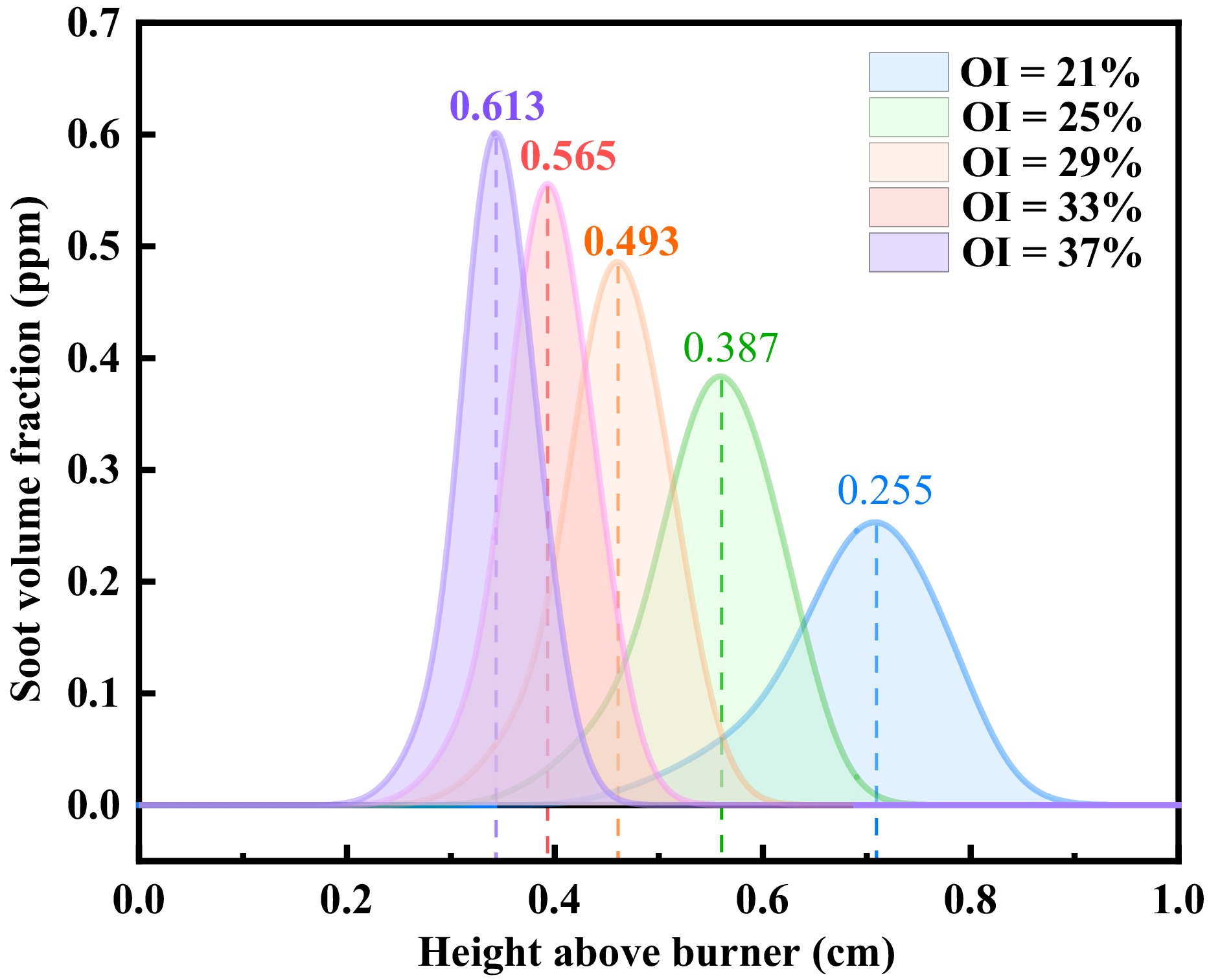

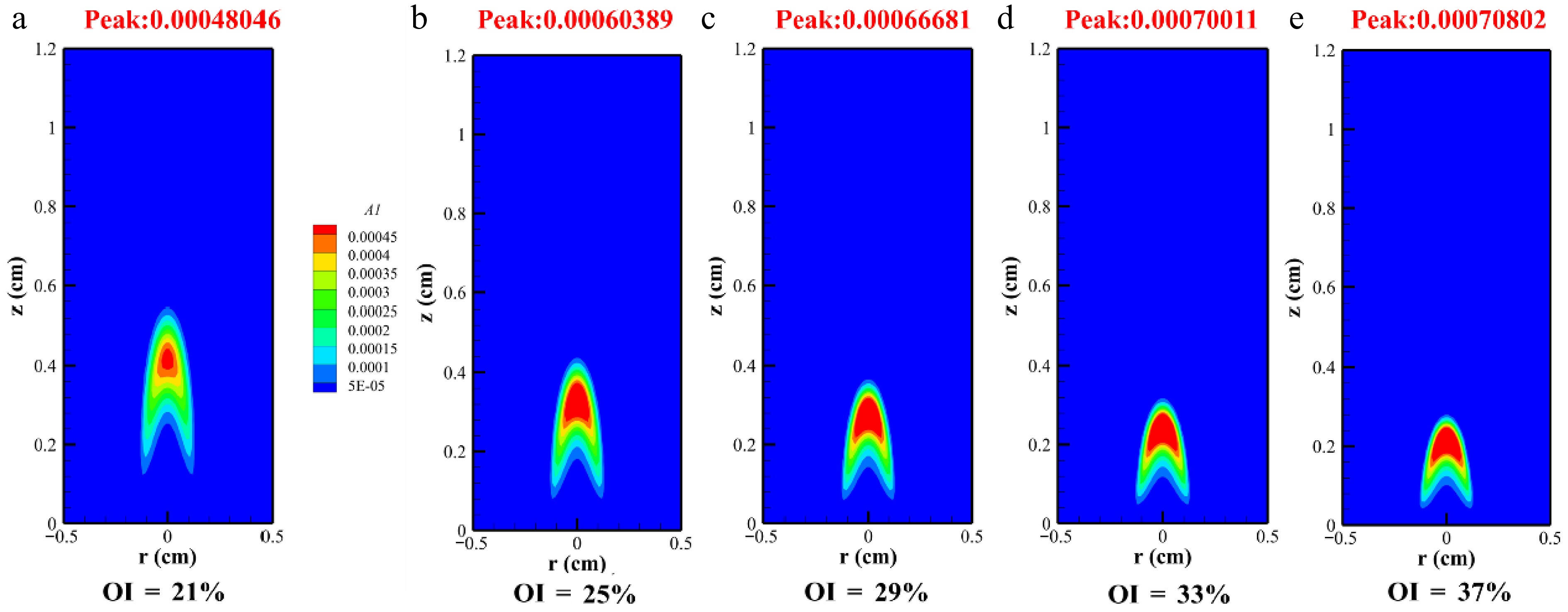

Soot constitutes a critical combustion pollutant, and investigating its distribution characteristics was essential for emission control. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of the SVF (fv) under varying OI conditions. As the OI increased, the spatial extent of elevated soot zones expanded, with peak fv rising from 0.255 to 0.613 ppm, a 2.4-fold increase. The figure reveals that the soot formation zones progressively shifted downstream while becoming spatially concentrated. Correlating with the temperature distributions in Figs 2 and 3 and the axial flame profiles, the soot distribution patterns mirrored temperature trends. At the flames' base, lower temperatures can also lead to soot formation. As the axial distance increased, rapid temperature escalation intensified the reaction rates, accelerating soot formation. At a greater flame height, oxidation surpassed the production rates, causing a gradual reduction in fv.

Figure 5 presents the axial soot distribution under varying oxygen concentrations. The peak SVF progressively shifted upstream as the oxygen levels increased, with recorded values of 0.255, 0.387, 0.493, 0.565, and 0.613 ppm. The figure also revealed that soot formation became increasingly concentrated along the flames' axis. Notably, elevated oxygen concentrations induced the downstream migration of the soot's distribution while narrowing the soot generation zone. This oxygen enrichment reduced the axial residence time of soot in methane/n-heptane flames, which was attributable to the enhanced oxidation kinetics.

Free radical distribution

-

To investigate the effect of the OI on soot formation in methane/n-heptane flames, this research analyzed key influencing factors. The hydrogen abstraction acetylene addition (HACA) reaction process is described by the following equation[31]:

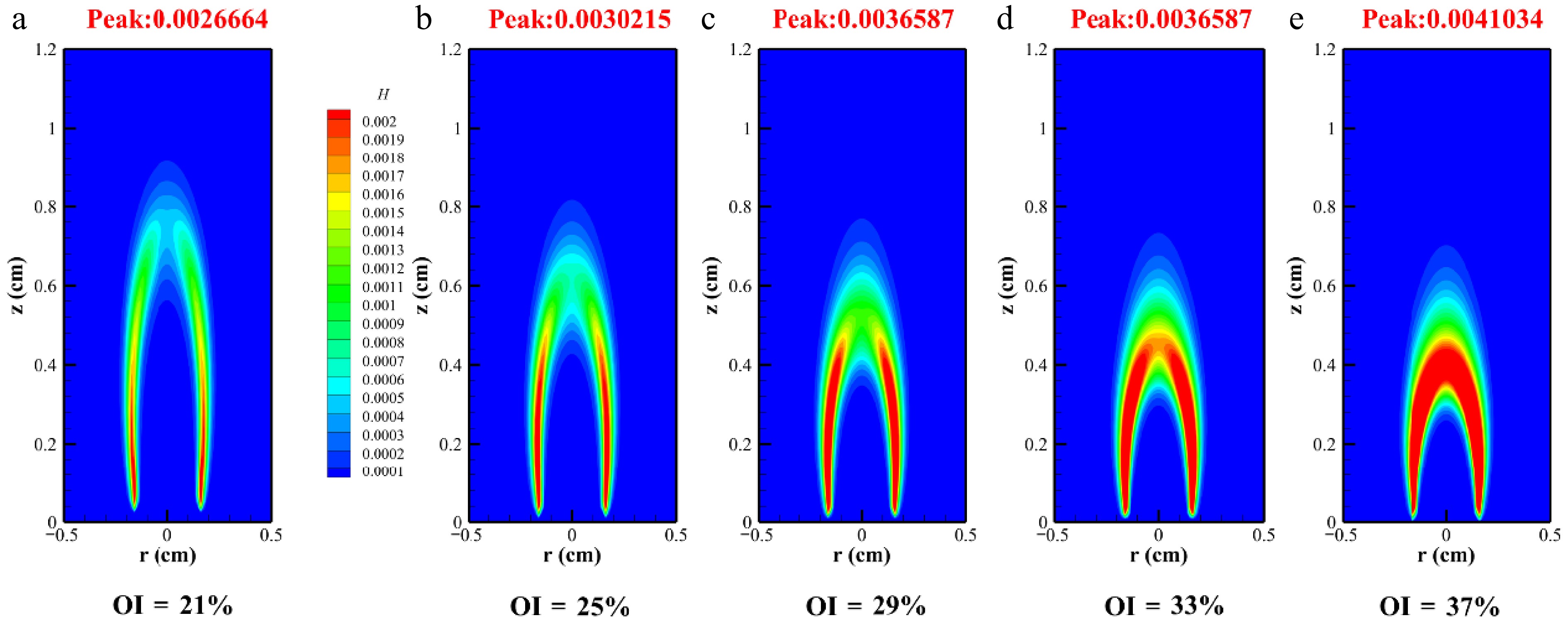

$ {{{A}}_{{i}}} + H \Leftrightarrow {A_i} \cdot + {H_2} $ (1) $ {A_i} \cdot + {C_2}{H_2} \Leftrightarrow Ai{C_2}{H_2} $ (2) $ {A_{\text{i}}}{C_2}{H_2} + {C_2}{H_2} \Rightarrow {A_{i + 1}} + H $ (3) To analyze the soot's distribution, the key free radicals H and OH were initially investigated. Figure 6 reveals that as the oxygen content increased, H radical peak values reached 0.0026664, 0.0030215, 0.0036587, 0.0036587, and 0.0041034 ppm. The region where the H radicals exceeded 0.002 ppm expanded with rising oxygen levels. Additionally, a higher OI reduced the height of H radical generation, as shown in Fig. 6a. The peak H radical position occurred at 0.92 cm under baseline conditions, shifting to 0.84 cm at OI = 25% and further decreasing to 0.72 cm at OI = 37%. The concentration of H radicals of the flame at the edge was higher than that at the center of the flame. At the edge of the diffusion flame, the fuel and oxidant mixed and approached the ideal reaction ratio, resulting in a faster rate of H radical generation. H radicals were driven by temperature gradients and migrated from high-temperature regions to relatively low-temperature flame edges. In the flame edge region, H radicals were more likely to diffuse radially towards low-temperature and low-concentration areas in addition to axial diffusion. Chain reactions involving free radicals such as H, O, OH, etc. (such as H2+OH <=> H2O+H) mainly occurred at the reaction front.

Flame height represents critical parameters in a flame's structure, reflecting its combustion status and soot formation processes. These parameters also qualitatively indicate the residence time of soot particles from inception to complete oxidation. Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of the OH mole fraction in methane/n-heptane flames under varying OIs. As the oxygen content increased, peak OH concentrations reached 0.0059373, 0.008072, 0.010401, 0.012757, and 0.01526. The data revealed that OH radicals were predominantly concentrated in the upstream flame wings. Typically, flame height is defined by the position of peak temperature or OH concentrationalong the centerline, whereas the visible flame height is determined by the radiation emissions of soot[32].

Figure 7 reveals that increasing the OI reduced flame height, which decreased to 1.12 cm at OI = 37%. This trend indicated a shortened soot formation time along the axis of methane/n-heptane flames. The phenomenon was attributed to enhanced oxygen entrainment into the fuel stream as a result of elevated co-flow oxygen content, accelerating the reaction kinetics. Concurrently, the rise in flame temperature diminished the OH radicals' residence time, contributing to the reductions in flame height. Furthermore, the increased oxygen concentration in the reaction zone elevated the peak OH concentrations, simultaneously promoting soot particle oxidation rates and reducing the luminous height of the soot[32].

Distribution of soot precursors

-

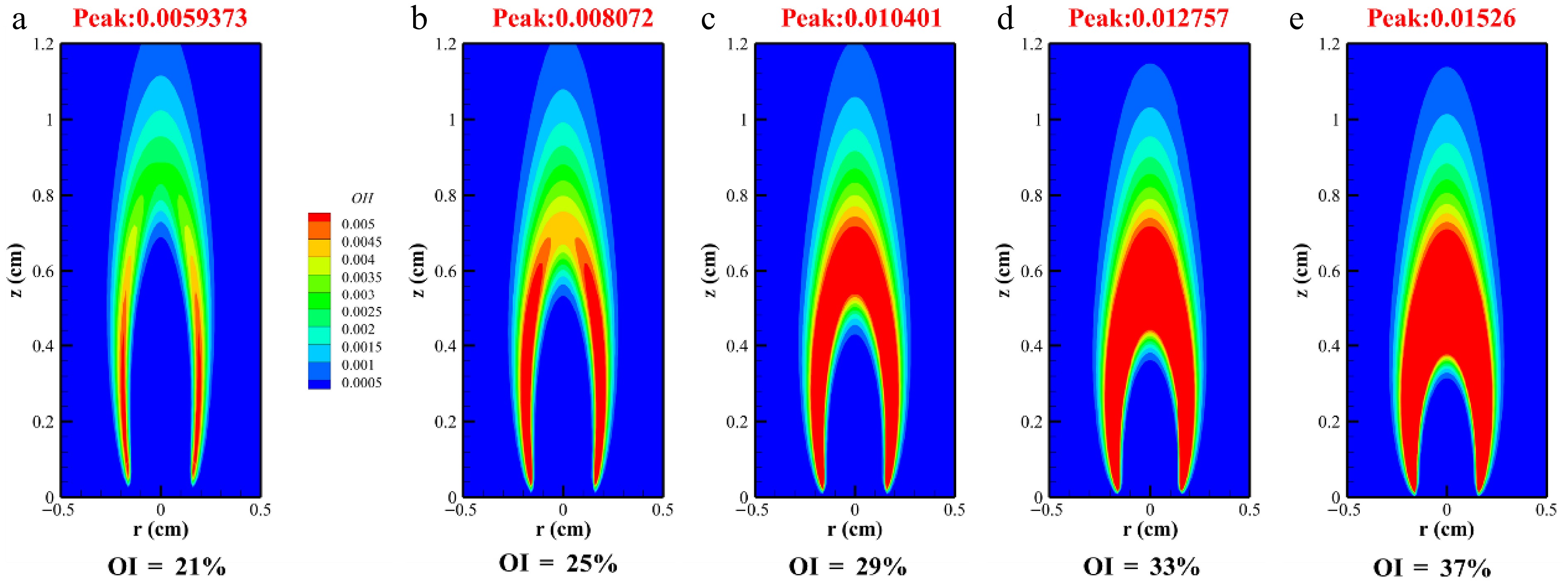

This study investigated free radicals and subsequently explored soot precursors, specifically acetylene (C2H2) and benzene (A1). These species are critical for the formation of larger PAHs in flames. Acetylene serves as a key component in the soot surface growth. As shown in Fig. 8, elevated oxygen content increases the mole fraction of acetylene during this process, leading to higher soot surface growth rates under increased OI. However, because of the significantly lower mole fraction of hydrogen atoms relative to acetylene, the growth rate exceeded the inhibition rate. Figure 8 illustrates the peak acetylene concentration curve, showing mole distributions of 0.019618, 0.022468, 0.024817, 0.026408, and 0.027508 as the OI increased from 21% to 37%, representing a 42% rise in the peak C2H2 concentration. Consequently, elevated OI enhanced the soot surface growth. As depicted in Fig. 6, the mole fraction of H increased radially under high OIs, correlating with suppressed soot formation. Nevertheless, the substantially higher acetylene concentration compared with hydrogen atoms resulted in net growth effects surpassing the inhibitory impacts.

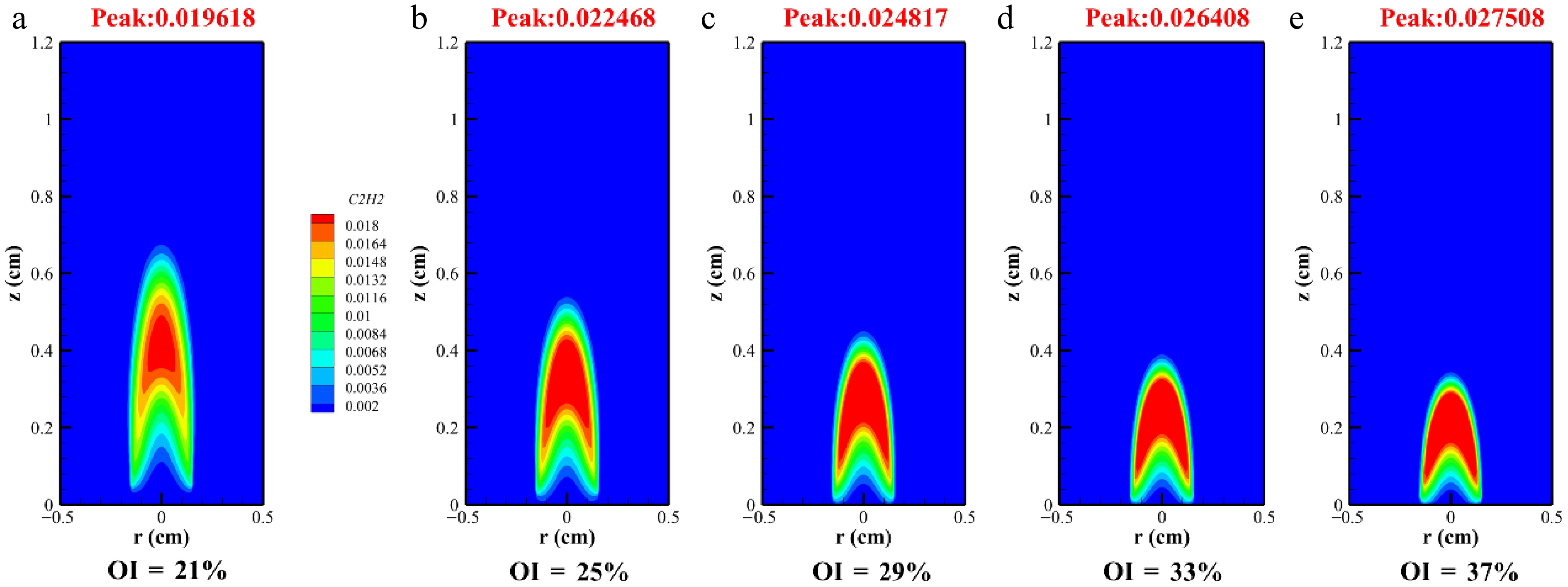

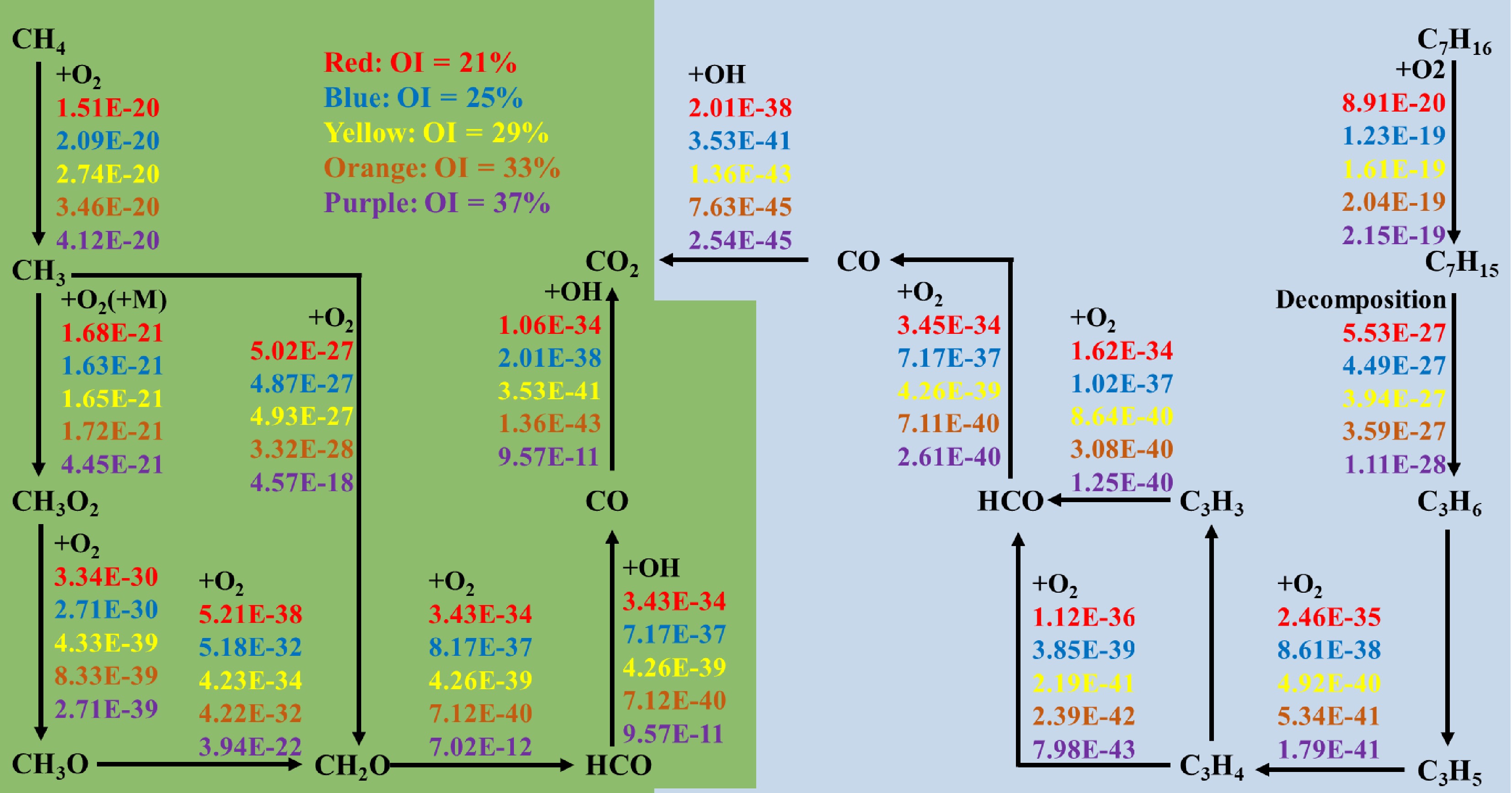

Benzene represents the initial aromatic ring, which undergoes growth into PAHs via the continuous HACA mechanism. Figure 9 illustrates the mole distribution of A1 in methane/n-heptane flames under varying OIs. The peak mole fractions progressively increased from 0.00048046 to 0.00060389, 0.00066681, 0.00070011, and 0.00070802 as the OI rose from 21% to 37%, reflecting the promoting effect of oxygen content on the formation of benzene in flames. Benzene preferentially formed soot through its stable cyclic structure and significantly promoted the mass growth of carbonaceous particles as surface growth sites. Furthermore, elevated OI shifted the position of A1 formation toward lower heights, suggesting that increased oxygen promoted earlier soot inception and compressed the spatial domain required for combustion reactions.

Figure 10 illustrates the reaction pathways of methane and n-heptane under varying OI conditions. As depicted, elevated oxygen concentrations accelerated the initial decomposition of fuel. For the reaction CH4 + O2 <=> CH3 + HO2, the reaction rate increased from 1.5E-20 to 4.12E-20 with rising OIs. Similarly, the reaction rate for n-heptane + O2 <=> C7H15 + HO2 rose from 8.91E-20 to 2.15E-19. The figure also revealed that oxygen enrichment exerts differential effects on intermediate reactions: whereas CH3O + O2 <=> CH2O + OH is promoted, other pathways may be inhibited. Consequently, under 2 atm operating conditions, modulating the OI critically influenced both the reactants' consumption rates and the kinetics of soot precursor formation.

-

This study investigated soot formation in methane/n-heptane dual-fuel flames under varying OI conditions at 2 atm using the CoFlame code. This study comprehensively analyzed flame temperature, SVF, the distribution of free radicals, and soot precursors. The key findings are summarized as follows: (1) As OI increased from 21% to 37%, flame temperature rose, with the SVF rising from 0.255 to 0.613 ppm. (2) Oxygen enrichment reduced the peak formation locations of H and OH radicals while intensifying their peak concentrations, concurrently decreasing flame height, and the H radical peak values reached 0.0026664, 0.0030215, 0.0036587, 0.0036587, and 0.0041034 ppm. (3) With an increase in the OI, the formation time of soot along the axis of methane/n-heptane flames was shortened. (4) The analysis of soot precursors revealed that elevated oxygen concentration enhanced the production of acetylene and A1 (benzene) by 42% and 47%, respectively.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52176095) and the Science Fund of State Key Laboratory of Engine and Powertrain System (No. skleps-sq-2023-224).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data collection and analysis: Liu J, Dou Z, Yao J; formal analysis: Liu J, Li Y, Su X, Dong W; writing—original draft: Liu J; writing—review and editing: Chu H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

Although authors Liu J, Dou Z, Li Y, and Su X are the employees of Weichai Power Co., Ltd., the work presented herein is independent academic research and is not related to the commercial interests of the company. The authors declare that no financial or other contractual agreements between the company and the authors or their institutions influenced the design, outcome, or reporting of this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu J, Dou Z, Li Y, Su X, Yao J, et al. 2025. Numerical study on soot formation in methane/n-heptane laminar diffusion flames under an oxygen-rich environment at elevated pressure. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e018 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0023

Numerical study on soot formation in methane/n-heptane laminar diffusion flames under an oxygen-rich environment at elevated pressure

- Received: 28 July 2025

- Revised: 26 August 2025

- Accepted: 17 September 2025

- Published online: 16 October 2025

Abstract: High-pressure and oxygen-enriched combustion technologies markedly elevate thermal efficiency, promote complete combustion, and mitigate the heat loss attributable to elevated temperatures in internal combustion engines. This study examined soot formation in methane/n-heptane dual-fuel under high-pressure oxygen-enriched conditions at 2 atm by utilizing the CoFlame code. With the oxygen index (OI) atmosphere rising from 21% to 37%, the soot volume fraction (SVF) increased 2.4-fold, and the peak flame temperature rose from 2,199.2 to 2,548.8 K. In addition, the temperature of the methane/n-heptane flame decreased with the increase in the OI content downstream of the flame. An increase in the OI extended the soot formation region of methane/n-heptane flames and relocated the maximum point of the flame axis volume fraction closer to the nozzle. As the OI rose, peak H radical fractions increased from 2.67 × 10−3 to 4.10 × 10−3, an increase of 53.6%. Under a high OI, the H mole fraction exhibited radial growth, which correlated with suppressed soot formation. Nevertheless, the markedly greater mole fraction of acetylene relative to H atoms led to net growth outweighing the inhibitory effects. The elevated oxygen concentration in the reaction zone raised the OH peak concentrations, accelerating the oxidation of soot while simultaneously reducing the visible soot height. As the OI increased, A1 peak concentrations rose from 0.00048046 to 0.00070802, up by 47.4%.

-

Key words:

- Soot /

- Oxygen-rich /

- Diffusion flame /

- High pressure /

- Numerical simulation