-

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the predominant methylation modification in RNAs, is crucial for various physiological and pathological processes in organisms[1,2]. This m6A methylation was initially discovered in bacterial DNA in 1955, and then identified in mRNAs of mammalian cells during the early 1970s[3−5]. Recently, newly emerging methods have revealed a wide landscape of m6A modifications in mRNAs, such as methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq)[6], direct RNA sequencing (DRS)[7], and m6A-sensitive RNA endoribonuclease-facilitated sequencing (m6A-REF-seq)[8]. It was reported that m6A modifications occur in ~30% of transcripts[9]. In addition to mRNAs, it has gradually been accepted that m6A modification occurs in nearly all types of RNAs, such as tRNAs, rRNAs, circRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs[2,10,11]. Most m6A sites are found within the conserved DRACH sequence motif, where D represents G/A/U, R stands for G/A, and H corresponds to A/U/C[9,12−14]. The dynamic regulation of m6A modifications is precisely controlled. This process involves the m6A methyltransferases, known as 'writers', and demethylases, referred to as 'erasers', which play key roles in adding and removing m6A methylation modifications[1,2]. Several writer proteins have been identified, such as METTL3/14/16, RBM15/15B, ZC3H3, VIRMA, CBLL1, WTAP, and KIAA1429[1,2,15−20]. Meanwhile, FTO and ALKBH5 are well-characterized erasers that are responsible for the removal of m6A modifications[1,15].

The biological roles of m6A modifications mostly depend on the recognition of m6A-binding proteins known as m6A readers[21]. These reader proteins recruit various complexes to regulate RNA's metabolism, splicing, translation, stability, translocation, and structures[2,15,22]. To date, a series of reader proteins have been identified and characterized, such as YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing proteins, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (hnRNPA2/B1), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C (hnRNP C), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G (hnRNPG), insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein 1/2/3 (IGF2BP1/2/3), and eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3)[23,24−28]. Notably, although YTH domain-containing proteins are well-established m6A readers, the roles of other proteins, such as hnRNPA2/B1, IGF2BP1/2/3, hnRNPC, hnRNPG, and eIF3, in m6A recognition remain controversial[23,28]. Hence, YTH domain-containing proteins have been extensively studied across various organisms. The YTH domain, consisting of 100–150 residues, is evolutionarily conserved with the ability to recognize the m6A modifications[29]. Generally, these YTH domain-containing genes can be categorized into three subfamilies comprising five distinct members: the YTHDF subfamily (YTHDF1/2/3), the YTHDC1 subfamily (YTHDC1), and the YTHDC2 subfamily (YTHDC2)[11,30,31].

The accumulating documents have revealed that YTH domain-containing genes play diverse roles in the regulation of RNA's stability, splicing, export, and translation. Studies have proven that YTHDF1 can promote mRNA translation[32,33], YTHDF2 contributes to the degradation of mRNAs by reducing stability[34,35], and YTHDF3 was reported to either promote translation or facilitate mRNA degradation[34]. YTHDC1 is involved in RNA splicing and nuclear–cytoplasmic transport[36,37], whereas YTHDC2 is implicated in enhancing the translation efficiency of the target mRNAs[38,39]. For example, in higher vertebrates, YTH domain-containing genes have been systematically characterized and extensively investigated for their roles in responding to both abiotic and biotic stresses[40]. The repressed expression of YTHDF2 or YTHDF1 markedly enhances the activity of interferon-stimulated genes, creating an antiviral environment that inhibits the replication of both VacV and HSV-1[35]. In mouse (Mus musculus), YTHDF1 deficiency has been shown to limit lysosomal protease expression in dendritic cells (DCs), thereby enhancing cross-presentation and boosting the effectiveness of CD8+ T cell responses against tumor cells[41]. However, despite their crucial roles in recognizing m6A modifications, reports on YTH domain-containing genes in teleosts remain limited, and these have only been reported in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)[40,42]. During the embryonic development of zebrafish, YTHDF2 promotes the clearance of maternal mRNAs by recognizing m6A modifications[42]. Furthermore, YTHDC2 mutants exhibit infertility, highlighting its crucial function in germ cell development in zebrafish[39]. Following heat stress, the expression levels of OmDF1, OmDF2, OmDF3, OmDC1b, and OmDC2 are significantly upregulated, indicating their potential roles in the high-temperature response of rainbow trout[40]. Meanwhile, in rice (Oryza sativa), loss-of-function YTHDFA mutants exhibited enhanced salinity tolerance, whereas YTHDFC mutants showed increased sensitivity to abiotic stresses[43]. In Camellia chekiangoleosa, most CchYTH genes exhibited a pattern of initially increasing and then decreasing expression levels as the duration of drought stress extended[44]. YTH11 has also been reported to regulate the stability of m6A-modified RNA transcripts, thereby facilitating the abiotic stress response in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana)[35].

Spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) is natively distributed along the northwestern Pacific coast[45]. It has become a promising aquaculture species in China and is widely farmed in both freshwater ponds and seawater cages[46−48]. Recently, the increasing frequency of diseases outbreaks has significantly affected the survival of spotted sea bass, posing a threat to the maricultural industry's development[45]. Moreover, fluctuations in temperature and salinity can adversely affect the physiological state of spotted sea bass[49,50]. Previous studies have shown that YTH domain-containing genes play crucial roles in responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Despite their functional importance, LmYTH domain-containing genes have not been systematically identified or characterized in spotted sea bass. Thus, this study carried out a genome-wide investigation to characterize the LmYTH domain-containing genes in spotted sea bass[40]. Phylogenetic analysis, combined with exon counts and length distribution, YTH domain organization, and motif analysis, revealed the evolutionary conservation of YTH domain-containing genes. Additionally, RNA-seq datasets and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results demonstrated the dynamic expression profiles of LmYTH domain-containing genes under bacterial infection, temperature fluctuations, and salinity changes. The present study offers a comprehensive perspective on the LmYTH genes, shedding light on their potential functional significance in response to abiotic and biotic stresses.

-

To identify LmYTH domain-containing genes, the hidden Markov model (HMM) profile for YTH521-B-like domain (PF04146) was retrieved from the Pfam protein database[51]. This HMM profile served as a query to search for candidate LmYTH domain-containing genes from all protein-coding sequences using HMMER v3.3.2 with the default settings[52]. Meanwhile, YTH domain-containing genes in model vertebrates (human, mouse, and zebrafish) were downloaded from the NCBI database. BLAST analysis was used to verify the accuracy of the candidate LmYTH domain-containing genes[48]. The online ProtParam tool was employed to evaluate the intrinsic physicochemical properties[53]. Subcellular localizations were further predicted via the Cell-PLoc 2.0 online platform[54]. Iso-Seq data sourced from the previous study were used to detect alternative splicing events[55].

Phylogenetic analysis

-

The phylogenetic tree was constructed on the basis of protein sequences from the LmYTH candidates and YTH domain-containing genes from representative vertebrates. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using Clustal X (v2.0) with the default settings, which include a gap opening penalty of 10, a gap extension penalty of 0.2, the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix, and the complete alignment mode. The tree was then inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) method, with robustness evaluated by 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Finally, the phylogenetic tree was visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform[56].

Gene characteristics and three-dimensional protein structural analysis

-

The longest transcripts of YTH domain-containing genes from mouse, zebrafish, Japanese medaka, European sea bass, and spotted sea bass were extracted from NCBI Gene Transfer Format (GTF) files to obtain information on the gene structure, including exon number and length. Conserved motifs were identified using MEME v5.5.5[57], with the maximum motif counts set to 10. The YTH domain's locations were determined using NCBI Batch CD-Search[58].

The three-dimensional (3D) protein structure of MmYTH was modeled using the SWISS-MODEL database[59,60]. Meanwhile, the protein sequences of LmYTH were analyzed using the diffusion-based method in AlphaFold3 to predict their 3D structures. PyMOL v3.0.3 software was used for the visualization of YTH-GC (m6A) cytosine and uracil (CU) complexes in MmYTH and LmYTH proteins, further investigating their structural conservation. The binding sites for the interactions between m6A and aromatic cages were obtained from previously published studies[21,30]. Meanwhile, multiple sequence alignments were performed separately for each subfamily using the online tool ESPript 3.0, with the primary to quaternary protein structure information originating from the 3D structures in the present study[60].

Meta-analysis of RNA-seq data

-

The RNA-seq datasets were retrieved from the public Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the following BioProject accession numbers: PRJNA1093234 (Nocardia seriolae infection), PRJNA859992 (skeletal muscle cells under different temperatures), PRJNA841263 (Aeromonas hydrophila infection), PRJNA755166 (Aeromonas veronii infection), PRJNA557367 (temperature changes), PRJNA515986 (acute hypoxia), and PRJNA611641 (alkalinity stress). The experimental designs were as follows.

N. seriolae infection experiment: Spotted sea bass (average weight 53.22 ± 9.0 g) were randomly assigned to two groups—control and treatment—with each group cultured in three replicate tanks (60 individuals per tank). Following anesthesia, the treatment group was administered an intraperitoneal injection of 100 µL of an N. seriolae suspension at a concentration of 1 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, while the control group received an equivalent volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Spleen samples were subsequently collected at 0, 48, 96, and 120 h post-injection, immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C. Twelve RNA-seq libraries were prepared, comprising three replicates per group at each time point, and sequenced on the Illumina platform.

A. hydrophila infection experiment: Spotted sea bass (400 ± 50 g) were divided into two groups, one of which was intraperitoneally injected with A. hydrophila (1 × 107 CFU/mL), while the control group received an equivalent volume of PBS. Intestinal tissues from both groups were collected at 24 h post-injection, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ten sequencing libraries were prepared (five replicates per group) and submitted for sequencing on the Illumina platform.

A. veronii infection experiment: 50 spotted sea bass (8 ± 1 g) were intraperitoneally injected with A. veronii at a dose of 8.5 × 105 CFU/g (LD50), while 20 fish received an equivalent volume of 0.85% saline. Spleen tissues were collected at 0, 8, and 24 h post-infection. Nine sequencing libraries were prepared (three replicates per group) and submitted for sequencing on the Illumina platform.

Hypoxia challenge experiment: 60 healthy spotted sea bass (178.25 ± 18.56 g) were transferred into three tanks (20 fish per tank). Oxygen levels were reduced to 1.1 ± 0.14 mg/L within 1 h by adding nitrogen gas, and the hypoxia experiment lasted for 12 h. Oxygen levels were monitored every 10 min. Gill tissues were collected from three fish per tank at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h, then used for RNA extraction. Twelve sequencing libraries were prepared (three replicates per time point) and submitted for sequencing on the Illumina platform.

Alkalinity challenge experiment: Spotted sea bass juveniles were acclimated from seawater to freshwater for 30 days before exposure to alkaline water (carbonate alkalinity: 18 ± 0.2 mmol/L) for 3 days. Gill tissues were sampled at 0, 12, 24, and 72 h post-exposure for RNA extraction. Total RNA from three individuals per tank was pooled into a single sample. Twelve RNA-seq libraries were constructed, with three replicates per group for sequencing on the Illumina platform.

Temperature challenge experiment for tissues: 240 healthy spotted sea bass (2.00 ± 0.01 g) were randomly distributed into eight circular fiberglass tanks (200 L), with 30 fish per tank. These tanks were equally divided into two groups, with water temperatures maintained at either 27 or 33 °C for 8 weeks. At the end of the experiment, nine fish were randomly sampled from each tank and anesthetized. Total RNA was extracted from liver and spleen tissues. Twelve RNA samples (three replicates per treatment) were prepared for transcriptome sequencing.

Temperature challenge experiment for cells: Dorsal white skeletal muscle (approximately 1 cm3) was excised from anesthetized spotted sea bass (28.46–31.35 g). The tissue was washed, adipose tissue was removed, and the remianing muscle was minced into small pieces before being placed in a cell culture chamber with a growth medium. Cells were cultured at 25 °C in a CO2-free incubator to support cell migration and passage. When cells reached approximately 70% confluency, they were subcultured using trypsin, and fibroblasts were removed through pre-incubation. The cells were then divided into two groups: A proliferating group, where they were maintained in the growth medium, and a differentiating group, where they were induced to differentiate using a differentiation medium. Each group was further divided into three subgroups and cultured at 21, 25, and 28 °C. Eighteen sequencing libraries were prepared (three replicates per group) and submitted for sequencing on the Illumina platform.

Raw reads were processed with fastp software (using a -q 20 cutoff) to trim and filter, yielding clean reads. Quality assessment of these clean reads was subsequently performed with FastQC software. High-quality reads were then aligned to the reference genome using hisat2 software with the default settings, and the resulting alignments were sorted and saved in BAM format. The count matrix was generated to quantify the number of reads mapped to each LmYTH domain-containing gene. The expression levels were normalized and represented as fragments per kilobase of transcripts per million mapped reads (FPKM). Differential expression analysis of the LmYTH domain-containing genes was performed using the DESeq2 (v1.44.0), applying stringent criteria of |log2Fold Change| ≥ 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.05[61,62].

Salinity experiment

-

A total of 90 healthy spotted sea bass juveniles (body weight 45 ± 5 g) were obtained from the National Aquatic Technology Promotion Station, Beijing Freshwater Breeding Demonstration Base. Prior to the salinity experiment, fish were randomly distributed into six tanks (0.6 m × 0.3 m × 0.4 m; 72 L), with 15 individuals per tank for the two-week acclimation period. Environmental conditions were tightly controlled: Water temperature was held at 15 ± 0.5 °C using a semiautomatic temperature regulation system, dissolved oxygen levels ranged from 6 to 8 mg/L, pH was stabilized between 7.6 and 7.8, salinity was kept at 1‰ ± 0.5‰, and a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod was applied. After the acclimation, the tanks were randomly assigned into control and treatment groups. Salinity in the control group was kept at 0‰, while sea salt (Yier Sea Salt, Brand: Fisherman; product number: 10070170378869) mixed with fresh water was used to gradually increase the salinity in the treatment group at a steady rate of 5‰ per day until it reached 30‰. The survival rate of the experimental fish remained at 100% throughout the experiment. After 24 h of adaptation to 30‰ salinity, three fish per tank were randomly selected and anaesthetized with 40 mg/L MS-222 (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester methane-sulfonate). Gill tissues were rapidly collected for RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR experiment

-

Total RNA was extracted from the gill tissues in both the control and treatment groups using the traditional Trizol method. RNA from three individuals per tank was pooled to reduce individual variability. High-quality RNA was then used for cDNA synthesis.

Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 5 software, and the details are provided in Supplementary Table S1. RT-qPCR was performed using the ChamQ SYBR Colour RT-qPCR Master Mix kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. Each experimental condition was performed in triplicate at the biological level, with each biological replicate being analyzed in three technical replicates. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method, with 18S rRNA as the internal control. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student's t-test, and the results are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE).

-

Overall, six putative LmYTH domain-containing genes were comprehensively identified and designated as LmDF1a, LmDF1b, LmDF2, LmDF3, LmDC1, and LmDC2, on the basis of an analysis using HMMER and BLAST (Table 1, Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). Iso-Seq analysis revealed that all LmYTH domain-containing genes in spotted sea bass possessed a single transcript, except for LmDF3, which had two different transcripts derived from an alternative 3' splice site (A3SS) event (Supplementary Fig. S3). The lengths of the longest transcripts of the LmYTH domain-containing genes ranged from 3,274 (LmDF1b) to 18,240 bp (LmDC2). These genes are distributed across four chromosomes in an uneven pattern in spotted sea bass. Notably, LmDC2, which possessed the longest coding sequence (CDS), exhibited the highest molecular weight of 152,046.47 kDa, more than twice that of the other YTH domain-containing genes. The theoretical isoelectric points (pI) ranged from 6.49 (LmDC1) to 9.03 (LmDF3). The LmYTH domain-containing proteins were primarily distributed in the cytoplasm. Additionally, LmDF1a, LmDF2, and LmDF3 were also localized in the nucleus.

Table 1. Characteristics of YTH domain-containing genes in Lateolabrax maculatus.

Gene name Gene_ID Chromosome position Gene length (bp) Exon number CDS (amino acids) Molecular weight (kDa) Theoretical

pIPutative localization LmDF1a evm.TU.scaffold_235.11 Chr6 (+): 10,274,451–10,282,610 8,160 6 625 68,102.75 8.81 Cytoplasm LmDF1b evm.TU.scaffold_11.218 Chr6 (–): 5,887,283–5,890,556 3,274 4 614 66,271.48 7.85 Cytoplasm, nucleus, extracellular matrix LmDF2 evm.TU.scaffold_8.5 Chr22 (+): 10,207,118–10,215,610 8,493 6 639 68,286.14 8.86 Cytoplasm LmDF3 evm.TU.scaffold_7.115 Chr4 (–): 11,565,042–11,572,492 7,451 5 629 69,371.54 9.03 Cytoplasm LmDC1 evm.TU.scaffold_318.9 Chr16 (+): 119,607–131,643 12,037 15 669 76,962.88 6.49 Nucleus LmDC2 evm.TU.scaffold_71.73 Chr16 (+): 20,863,917–20,882,156 18,240 30 1,356 152,046.47 7.87 Cell membrane, nucleus Phylogenetic tree of YTH domain-containing genes

-

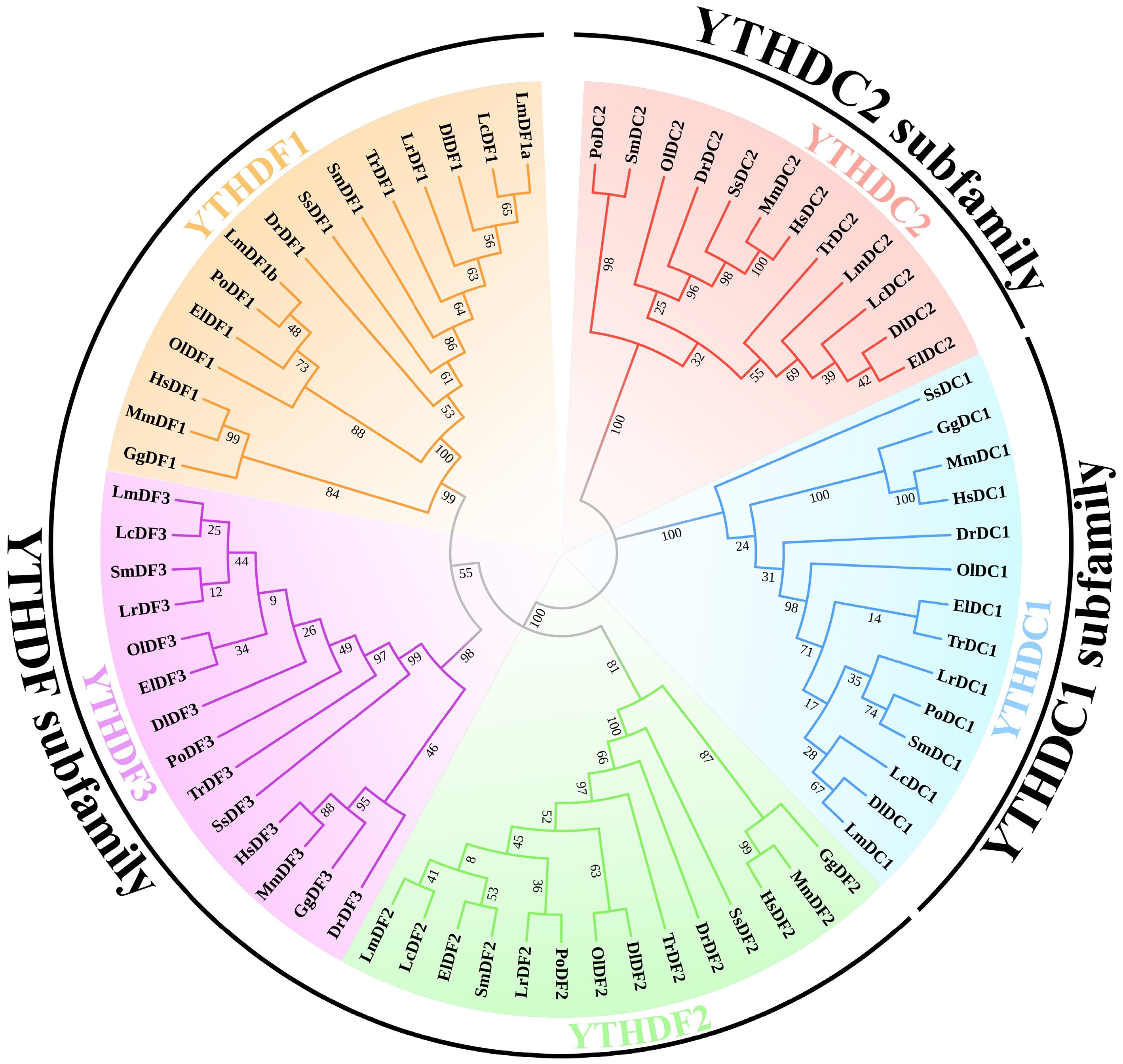

To explore the evolutionary relationships, a phylogenetic tree was constructed, based on 69 full-length amino acid sequences from spotted sea bass, human, mouse, zebrafish, Japanese fugu (Takifugu rubripes), large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea), turbot (Scophthalmus maximus), Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes), European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus), Barramundi perch (Lates calcarifer), Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus), chicken (Gallus gallus), and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). As illustrated in Fig. 1, the phylogenetic tree was clustered into five primary clades, corresponding to YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2. The topology was strongly supported by high bootstrap values. Moreover, these clades were grouped into three major clusters, consistent with the subfamily classifications of YTHDF, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2 subfamilies. These findings further supported the reliability and accuracy of the LmYTH domain-containing genes identification in spotted sea bass. Additionally, these results highlighted the evolutionary divergence among YTH domain-containing gene subfamilies in vertebrates.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of YTH domain-containing genes. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with 1,000 bootstrap replications. Amino acid sequences of the YTH domain-containing genes in human, mouse, spotted sea bass, and representative teleosts were aligned to build the phylogenetic tree. The five subclades of YTHDC1, YTHDC2, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 are distinguished with different colours. The abbreviations used are as follows: YTH domain-containing genes in Homo sapiens are labeled as Hs; Mus musculus, Mm; Danio rerio, Dr; Dicentrarchus labrax, Dl; Epinephelus lanceolatus, El; Gallus gallus, Gg; Larimichthys crocea, Lc; Lateolabrax maculatus, Lm; Lates calcarifer, Lr; Oryzias latipes, Ol; Paralichthys olivaceus, Po; Scophthalmus maximus, Sm; Salmo salar, Ss; Takifugu rubripes, Tr.

Gene structure and conserved motif analysis

-

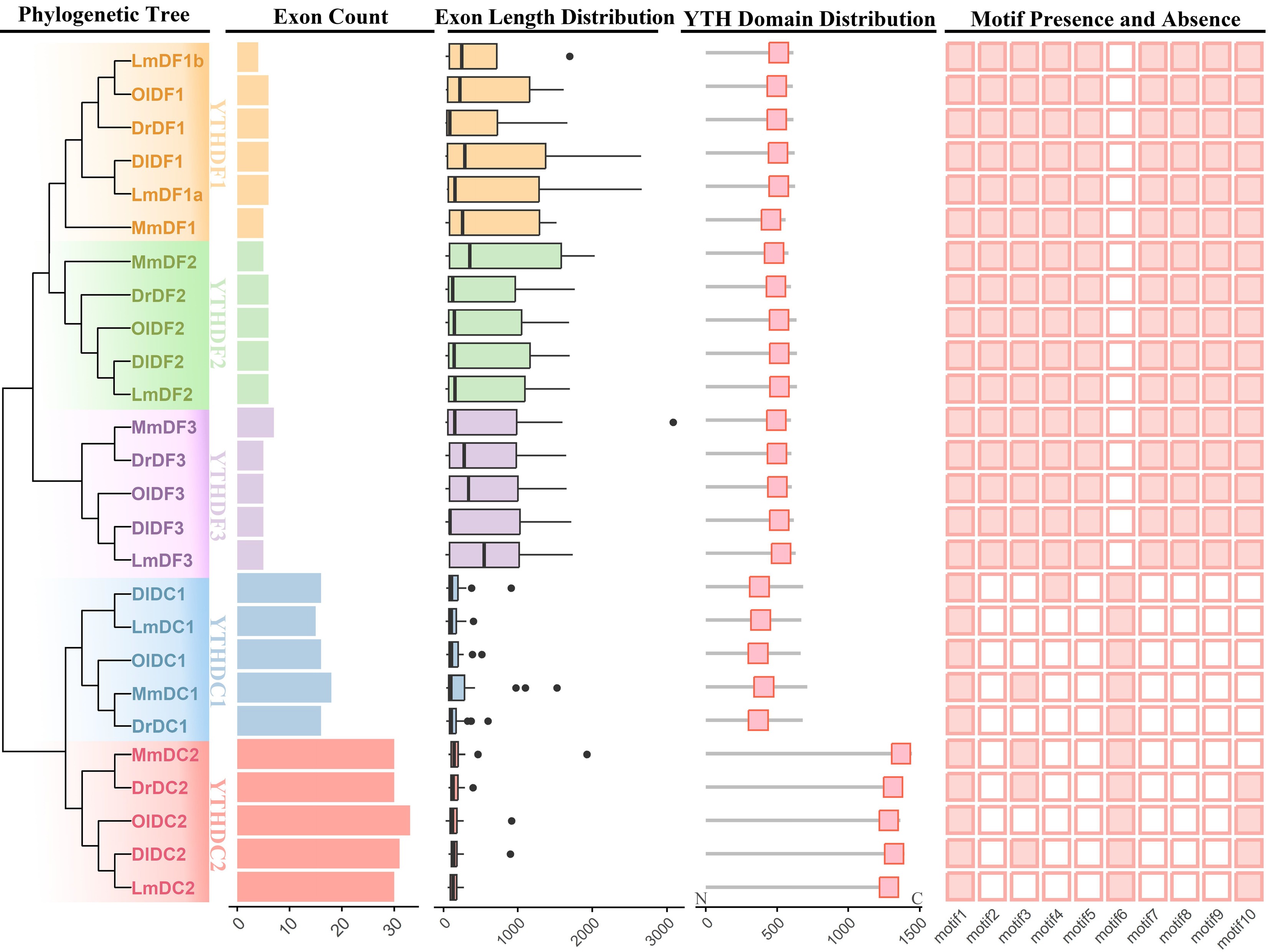

Gene structure analysis revealed that all the LmYTH genes had exon numbers similar to those of their respective clades (Fig. 2). Notably, members of the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies, particularly the YTHDC2 subfamily, harbored more exons than those of the YTHDF subfamily. The YTH domain, as predicted by the NCBI Batch CD search, was located in the C-terminal region of the YTHDF and YTHDC2 subfamilies, whereas the YTH domain of the YTHDC1 subfamily was positioned in the central region. Members of the YTHDF subfamily contained all motifs except Motif 6, suggesting high evolutionary conservation of this subfamily. Motif 6 was found exclusively in the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies. Meanwhile, all the members of the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies encompassed Motif 1, along with the variable presence of Motifs 3, 4, and 10. The sequence characteristics of the motif sites are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. In the YTHDF subfamily, Motifs 1 and 3 partially overlapped with the YTH domain, although Motif 2 was fully contained in the YTH domain. In the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies, Motif 1 partially overlapped with the YTH domain, whereas Motif 6 was entirely contained in the YTH domain.

Figure 2.

Gene structure and conserved motif analysis of YTH domain-containing genes. Exon counts, exon lengths, the YTH domain's distribution, and conserved motifs were integrated in accordance with the phylogenetic tree that was constructed using the neighbour-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replications. The five subclades, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3, are distinguished by distinct colours. The presence and absence of different motifs are represented as solid and open boxes, respectively. The abbreviations used are as follows: YTH domain-containing genes in Mus musculus are denoted as Mm; Lateolabrax maculatus, Lm; Danio rerio, Dr; Oryzias latipes, Ol; Dicentrarchus labrax, Dl.

Interaction analysis between m6A and YTH domain-containing proteins

-

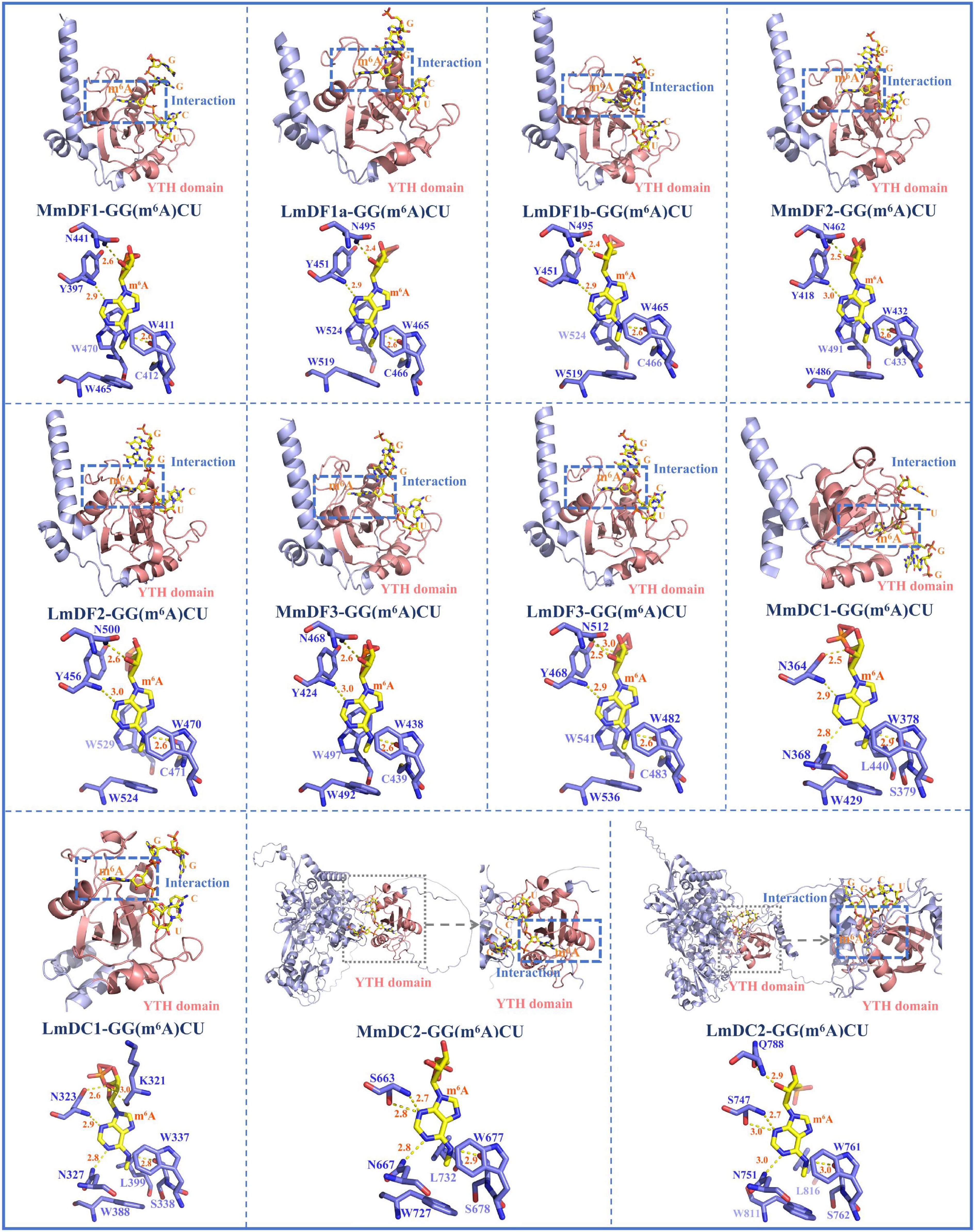

The 3D protein structure models of YTH domain-containing proteins in mouse and spotted sea bass were constructed and compared to explore the evolutionary conservation in binding ability and pockets to identify m6A modifications (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). YTH domain-containing proteins from mouse and spotted sea bass showed a high degree of structural similarity within the same subfamily, particularly in the YTH domain regions. Notably, the YTH domain exhibited a conserved structural arrangement across all the proteins in both species, characterized by a β-strand at the N-terminus and an α-helix at the C-terminus. However, the number of α-helices and β-strands in the YTH domains varied slightly among the three subfamilies: the YTHDF subfamily contained 4 α-helices and 8 β-strands, the YTHDC1 subfamily had 4 α-helices and 7 β-strands, and the YTHDC2 subfamily possessed 3 α-helices and 10 β-strands.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional protein structure models of YTH domain-containing genes and their interactions with m6A-modified adenine. The structure of the YTH domain is depicted in shades of pink. The other secondary structural elements, including α-helices, β-strands, and coils, are marked with cyan colour. In the YTH-GC (m6A) CU complexes, the RNA molecules and m6A modifications are represented with yellow colour, and the amino acid residues of YTH domain-containing proteins are shown with blue colour. Hydrogen bonds between the binding pocket and the m6A modification are indicated using dashed yellow lines (2.2 Å ≤ cutoff ≤ 3.0 Å). Abbreviations: Mus musculus, Mm; Lateolabrax maculatus, Lm.

In the interactions between RNA molecules and YTH domain-containing proteins, the m6A within the GGACU motif was embedded in an aromatic cage formed by the YTH domain (Fig. 3). The aromatic cage consisted of three hydrophobic amino acid residues (cage residues), which were either tryptophan (W) or leucine (L). The composition of the cage residues was conserved in the homologous YTH domain-containing proteins in mouse and spotted sea bass, but varied among different YTH subfamilies. Specifically, all three cage residues in the YTHDF subfamily were tryptophan, such as W465, W519, and W524 in LmDF1a; W465, W519, and W524 in LmDF1b; W470, W524, and W529 in LmDF2; and W482, W536, and W541 in LmDF3. In contrast, the cage residues in the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies were composed of two tryptophan residues and one leucine, such as W337, W388, and L399 in LmDC1 and W761, W811, and L816 in LmDC2. In addition to the aromatic cage, base-specific hydrogen bonds formed with additional hydrophobic amino acid residues, termed hydrogen bond (H-bond) residues, were also essential for the interaction between m6A modifications and YTH domain-containing proteins.

Strong hydrogen bonds (lengths: 2.2–3.0 Å) played important roles in maintaining structural stability. These interactions were visualized in the 3D stick models (Fig. 3). The m6A formed hydrogen bonds with three or four amino acid residues. In both mouse and spotted sea bass, the m6A-modified adenine formed similar hydrogen-bonding interactions with the corresponding amino acid residues.

Multiple sequence alignment analysis

-

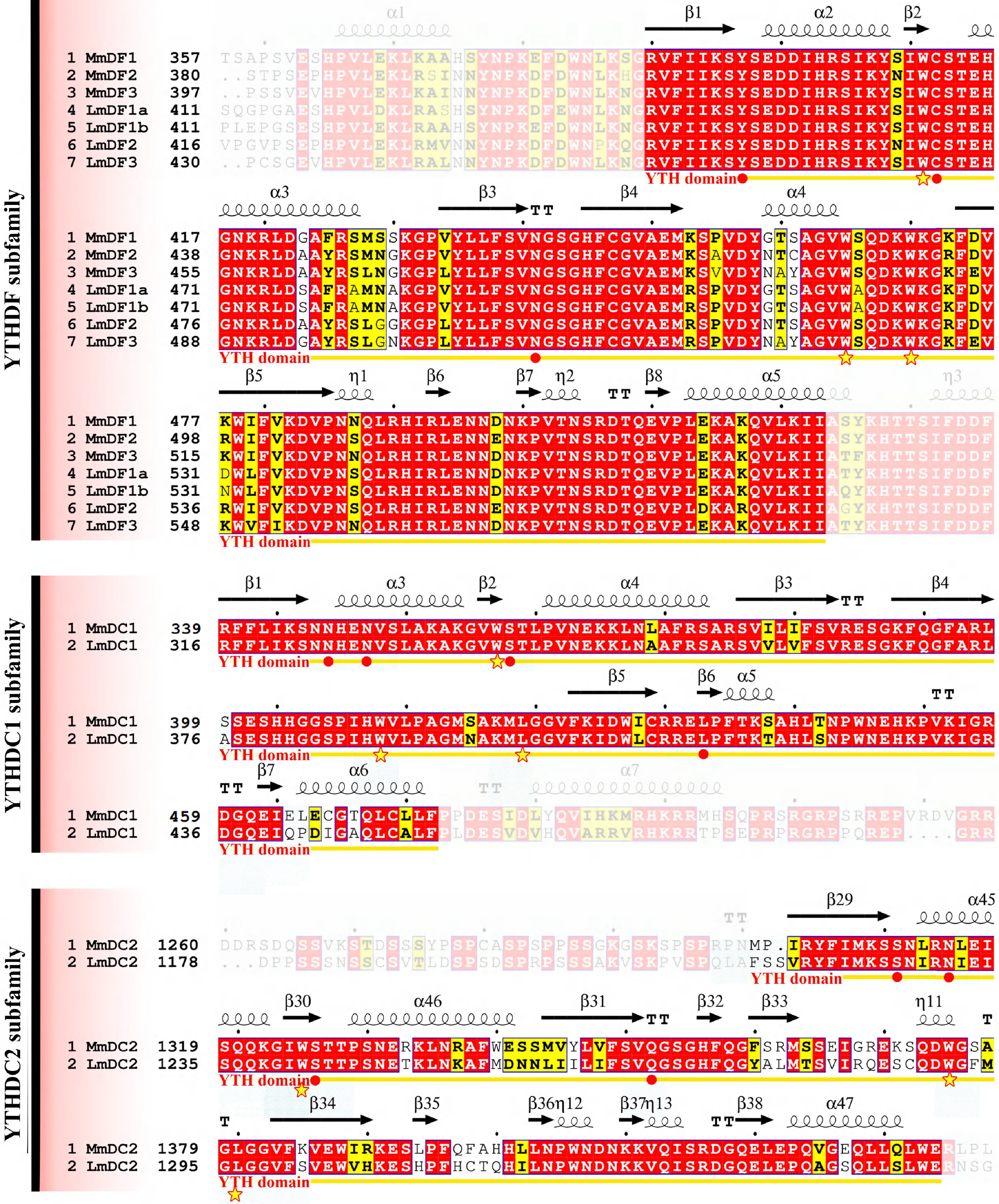

Multiple sequence alignments were performed to investigate the structural features of the YTH domain in mouse and spotted sea bass (Fig. 4). Compared with the YTHDC2 subfamily, the YTH domain sequences of proteins in the remaining subfamilies were much more conserved between mouse and spotted sea bass, with an identify value of > 82.8%. In contrast, a series of amino acid residues were divergent in the YTHDC2 subfamily of mouse and spotted sea bass with a relatively low identify value of 71.1%. The three or four amino acids forming strong hydrogen bonds (marked with red points in Fig. 4) were located upstream of the second cage residue, except for L403 in LmDC1. Notably, one of them was always adjacent to the first cage residue. Additionally, the amino acids were highly conserved in the neighboring regions of the cage residues and hydrogen bond residues.

Figure 4.

Multiple sequence alignments of YTH domains in mouse and spotted sea bass. Gene names and the corresponding amino acid positions are presented on the left of the sequence alignments. YTH domain-containing genes in mouse and spotted sea bass are designated as Mm and Lm, respectively. Predicted secondary structural elements are displayed above the sequence alignment, with medium squiggles representing α-helices, arrows indicating β-strands, and the letters TT denoting strict β-turns. In the sequence alignment, strictly conserved amino acid residues with 100% identity are highlighted in red with white lettering, whereas highly similar sequences are enclosed in blue frames and marked with blocks. The YTH domain is denoted by yellow arrows below the alignment, the cage residues are denoted by stars, and red solid points represent amino acids with the ability to form hydrogen bonds (hydrogen bond residues).

Expression patterns of LmYTH domain-containing genes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses

-

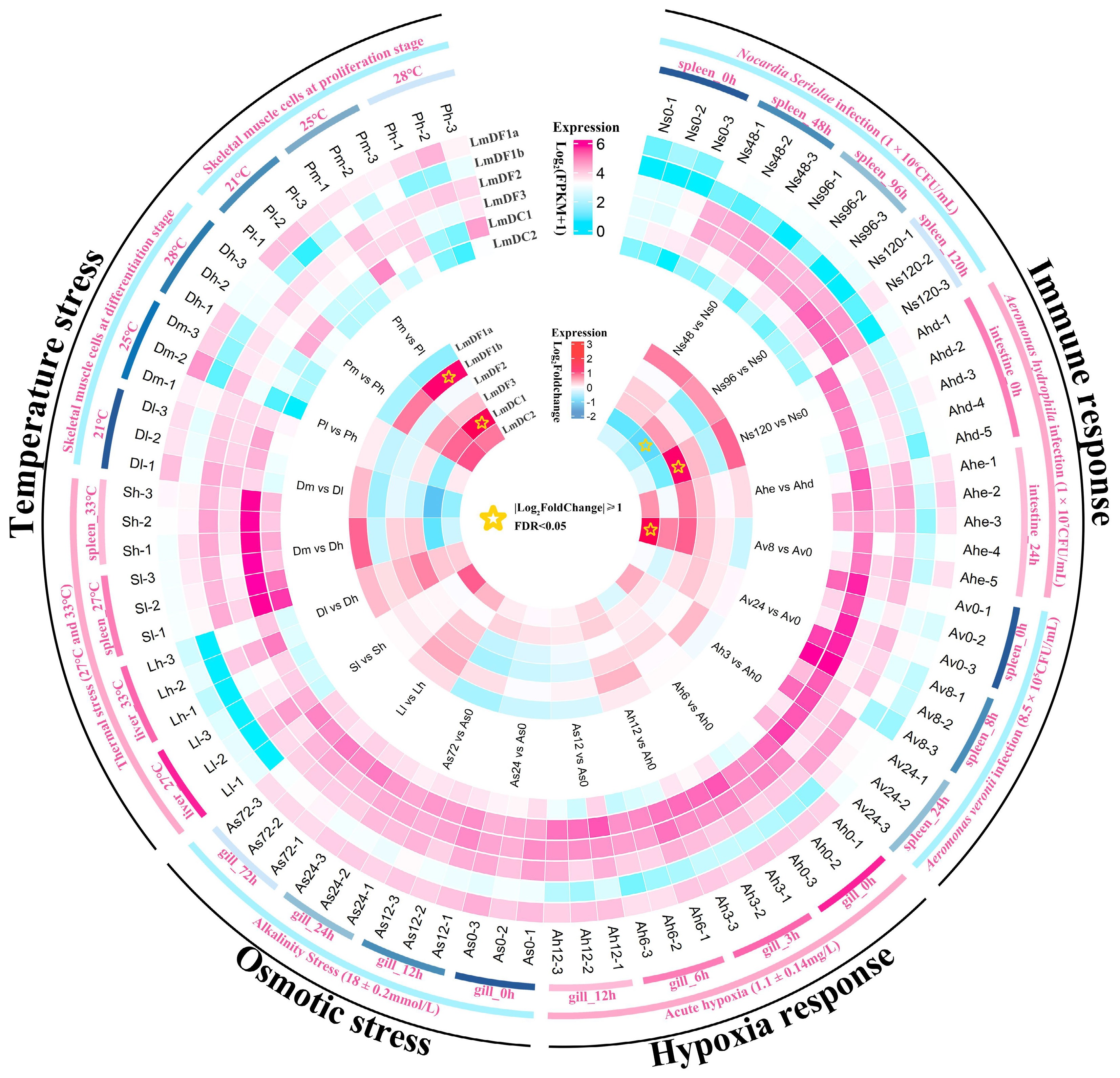

Several bacterial species, including N. seriolae, A. hydrophila, and A. veronii, have been reported to pose a serious threat to the health of spotted sea bass. The present study revealed that the expression patterns of several LmYTH domain-containing genes were changed after bacterial infection, suggesting their potential roles in the immune response in spotted sea bass (Fig. 5). After N. seriolae infection, the expression of LmDC1 in the spleens was significantly downregulated at 96 h, whereas LmDF3 was significantly upregulated at 120 h. Although no statistically significant differences were observed, the expression patterns of LmDF1a, LmDF2, and LmDF3 showed a similar trend in response to N. seriolae infection. In contrast, the expression levels of LmDF1b, LmDC1, and LmDC2 remained unchanged after infection. The expression of all the LmYTH domain-containing genes was insensitive to the A. hydrophila infection in the intestinal tissue of spotted sea bass, although LmDC1 was abundantly expressed. Meanwhile, LmDC2 exhibited significant upregulation in the spleens at 8 h after A. veronii infection.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of YTH domain-containing genes in spotted sea bass in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. The expression levels are normalized as the FPKM values and shown as log10(FPKM + 1), which are displayed in the outer heatmap. The significance of differential gene expression was determined using the DESeq2 v1.44.0 R package based on the criteria of | log2(Fold Change) | ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05. The differentially expressed genes are marked using stars in the inner heatmap.

LmDF1a, LmDF2, LmDF3, and LmDC1 were abundantly expressed in the gill tissues of spotted sea bass, compared with LmDF1b and LmDC2. No significant changes in the expression of any LmYTH domain-containing genes were observed in gill tissues under hypoxia and alkalinity stresses. This suggested that LmYTH domain-containing proteins may not act as readers for RNA m6A modification in response to hypoxia and adaptation to alkalinity. Additionally, the expression patterns of all the LmYTH domain-containing genes were investigated in liver, spleen, and skeletal muscle cells under different environment temperatures. It was evident that LmDF1b showed weak expression, especially in liver tissues. The expression levels of LmDF1b and LmDC1 in skeletal muscle cells cultured at 25 °C were significantly upregulated compared with cells cultured at 21 °C. Notably, LmDF1a displayed the opposite expression pattern in skeletal muscle cells compared with the duplicated copies of LmDF1b. There appears to be a functional divergence between LmDF1a and LmDF1b in response to temperature stress.

RT-qPCR analysis of LmYTH domain-containing genes under different salinity conditions

-

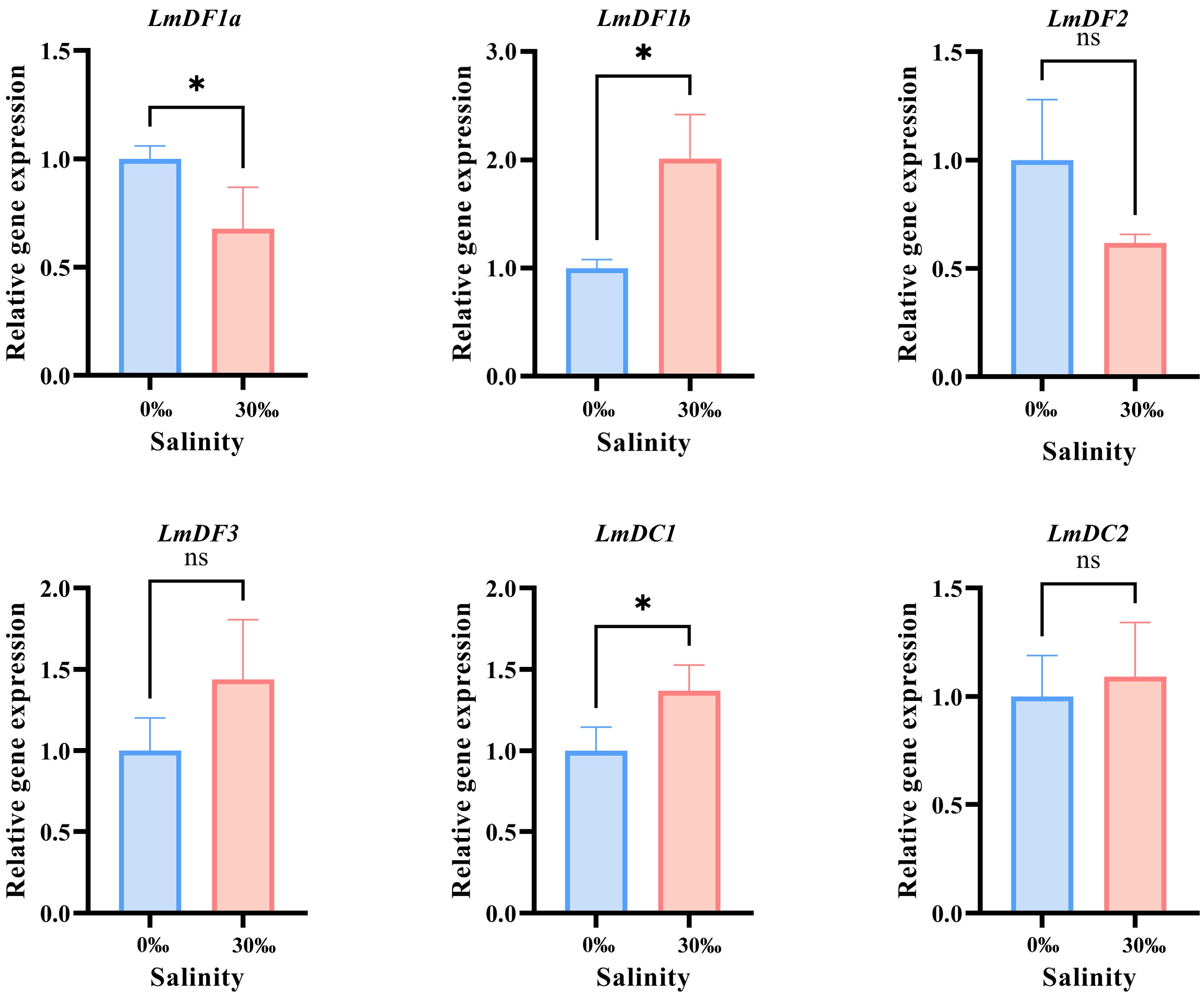

To investigate the potential roles of LmYTH domain-containing genes in response to different levels of salinity in the environment, RT-qPCR was conducted to evaluate their expression profiles in the gills following exposure to freshwater (0‰) and seawater (30‰). The results revealed that the expression levels of three LmYTH domain-containing genes were significantly affected by salinity changes (Fig. 6). In the seawater group, LmDF1a was significantly downregulated. In contrast, both LmDF1b and LmDC1 were significantly upregulated in seawater. Interestingly, LmDF1a and LmDF1b, the duplicated copies, exhibited opposite expression patterns in response to changes in salinity.

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR verification and statistical analysis. All the RT-qPCR experiments were performed with three biologically independent replicates. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method and normalized against 18S rRNA. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (* p < 0.05), while 'ns' indicates no significant difference.

-

At present, over 150 distinct RNA modifications with diverse biological functions have been identified in organisms[63]. These RNA modifications introduce additional layers of complexity to post-transcriptional regulation. Among them, m6A is generally accepted as one of the most abundant modifications in eukaryotic transcriptomes across nearly all RNA types, such as mRNAs, rRNAs, tRNAs, and snRNAs[1,2]. Reader proteins are necessary for the functional achievement of m6A modifications. In the last decade, the YTH domain-containing proteins have been widely investigated as acting as readers for the m6A modifications in both plants and animals[29,36]. In the present study, six LmYTH domain-containing genes were comprehensively identified and systematically analyzed. Conserved domain features, gene structures, and expression patterns under various stress conditions suggest that these genes may play important roles in response to abiotic and biotic stresses.

The six LmYTH domain-containing genes in spotted sea bass can be divided into three subfamilies. Previous studies have identified duplicated or triplicated copies of YTH domain-containing genes in rainbow trout, including OmDF1a, OmDF1b, and OmDF1c; OmDF2a and OmDF2b; and OmDC1a and OmDC1b[40]. However, only duplicated YTHDF1 genes were found in spotted sea bass, including LmDF1a and LmDF1b. The duplication of YTH domain-containing genes, originating from the 4R whole-genome duplication specific to salmon, was absent in spotted sea bass[40]. A series of differences in exon count, exon length, YTH domain position, and motif distribution were observed among the YTHDF, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2 subfamilies. The diversity of gene structure highlighted the evolutionary specialization and functional divergence among different YTH subfamilies. The YTH domain was predominantly located in the C-terminal region in both the YTHDF and YTHDC2 subfamilies, whereas it was positioned in the central region in the YTHDC1 subfamily. Similar findings were previously reported in rainbow trout[40]. In contrast, some members of the YTHDF subfamily in the plant alfalfa (Medicago sativa) exhibited N-terminal distribution of the YTH domain[64]. Motif distribution patterns were conserved within each subfamily. Motif 1 was present in all the YTH domain-containing genes of both spotted sea bass and other vertebrates, such as mouse, zebrafish, medaka, and European sea bass. However, Motif 6 only appeared in the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 subfamilies. The distribution of the YTH domain and the motifs' presence/absence may be linked to protein structure, enabling efficient interaction with GG (m6A) CU complexes.

Certain motifs were found to overlap with the YTH domain. Previous studies revealed that three shared motifs were identified in all 10 OmYTH genes in rainbow trout, all of which overlapped with the YTH domain. Only one motif was present across all members of LmYTH genes. Moreover, Motifs 1–3 overlapped with YTH domain in the members of the LmDF subfamily, while Motif 1 and Motif 6 were present in the YTH domain regions of the LmDC1 and LmDC2 subfamilies. These differences may be associated with variations in gene copy numbers in rainbow trout and spotted sea bass. The similarity in motif sequence characteristics suggests the strong evolutionary conservation of YTH domain functions.

The aromatic cage interacted with the m6A residue via a positively charged region formed by the side chains of three specific amino acids[65]. In human and mouse, a WWW-type aromatic cage composed of three tryptophan residues is specific in the structures of proteins encoded by members of the YTHDF subfamily, whereas the YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 proteins have a WWL-type cage consisting of two tryptophan residues and one leucine residue[30,39]. Similar findings were observed in the present study, suggesting a conserved mechanism for m6A recognition. A similar aromatic cage in YTHDF proteins was reported in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), although its YTHDC protein featured a WWY-type cage, in which the leucine (L) was replaced by tyrosine (Y)[15,66]. These observations suggest that the m6A-binding mechanism of YTHDCs differs between plants and animals, further highlighting significant evolutionary divergence in YTH domain-mediated m6A recognition in organisms. In addition, the 3D structures of YTH domain-containing proteins showed considerable similarities, including conserved patterns of α-helices and β-strands, and similar amino acid residues involved in hydrogen bonding with m6A-modified RNA. These findings indicated a highly analogous structural relationship between mouse and spotted sea bass, offering further support for the evolutionary conservation of YTH domain-containing proteins and their mode of binding to m6A modifications.

The expression patterns of multiple LmYTH domain-containing genes, particularly LmDF1b, LmDF3, LmDC1, and LmDC2, were altered in response to abiotic and biotic stresses. These findings suggested that LmYTH domain-containing genes might play important roles in stress response, similar to those observed in zebrafish and miiuy croaker (Miichthys miiuy)[42,67]. Previous studies have confirmed that YTHDF3 can regulate the decay of methylated mRNA and promote protein synthesis, thereby exacerbating inflammation in response to bacterial infection[5,34]. Meanwhile, YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 could regulate the expression of immunity-related genes[68,69]. For instance, YTHDC1 was significantly upregulated in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), showing a strong correlation with differentially expressed transcripts[70]. In teleosts, the spleen is one of the most important immune organs, playing a key role in response to bacterial infections. These reports are consistent with our findings that LmDF3 was significantly upregulated in the spleen after 120 h after N. seriolae infection, and LmDC2 showed elevated expression following A. veronii infection. In contrast, the expression of LmDC1 was significantly downregulated at 96 h after N. seriolae infection, indicating that the host might have suppressed translation efficiency and accelerated mRNA degradation in the spleen as part of the immune response to bacterial challenge. In mouse, co-transcriptionally deposited m6A has been shown to be crucial for the heat stress response[60]. Heat stress was found to reshape the genomic distribution of YTHDC1 in humans, which binds to m6A-modified heat-induced heat shock protein (HSP) RNAs, promoting HSP expression[37]. It was also reported that in humans, the expression of YTHDF2 significantly increased after heat stress, while YTHDF1 exhibited a more moderate increase[71]. The current study also yielded similar results, with LmDF1b and LmDC1 being significantly upregulated in proliferating skeletal muscle cells at 25 °C compared with those at 21 °C. In contrast, LmDF1a and LmDF2 exhibited a decreasing trend in expression. The significant upregulation of LmDF1b and LmDC1 might have been linked to cell proliferation, as elevated temperatures were found to promote the proliferation of skeletal muscle cells, a process characterized by highly active transcription and translation. In humans, YTHDF1 and YTHDC2 were shown to promote cell proliferation, which could further explain the significant upregulation of LmYTH domain-containing genes[41]. This expression pattern suggested that LmYTH domain-containing genes may contribute to transcriptionally active states associated with cell proliferation, consistent with their known roles in modulating gene expression dynamics in proliferating cells.

As a typical euryhaline teleost, spotted sea bass can live in both freshwater and seawater, exhibiting strong salinity tolerance and osmoregulatory capabilities. RT-qPCR analysis revealed distinct expression patterns of LmYTH domain-containing genes under freshwater and seawater conditions. For instance, LmDF1b and LmDC1 were significantly upregulated, whereas LmDF1a was downregulated. In alfalfa, MsYTH2 was predominantly expressed under salinity conditions, and stress-related cis-elements were identified in the upstream regions of YTH members' promoters, suggesting their responsiveness to environmental stressors[64]. Additionally, motifs enriched in specific amino acids, such as the leucine-rich repeat domain, were associated with salt resistance[64]. However, the leucine-rich repeat domain was absent in the proteins encoded by LmYTH domain-containing genes. Although RT-qPCR validation under salinity stress alone cannot conclusively demonstrate the functional roles of these genes, the observed expression differences, especially the opposite regulation of the duplicated genes LmDF1a and LmDF1b, suggest their potential functional divergence in response to salinity adaptation. Nevertheless, additional experiments are required to further validate the specific functions.

-

The present study systematically identified and characterized six members of LmYTH domain-containing genes, which can be divided into the YTHDF, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2 subfamilies. Similar gene structures, YTH domain distributions, and motif sites were observed between mouse and spotted sea bass. In addition, proteins encoded by LmYTH genes shared similar α-helices and β-strand compositions in their 3D structures, the same WWW- or WWL-type aromatic cages for m6A recognition, and common amino acid residues for hydrogen bond formation in mouse and spotted sea bass. These findings suggested the evolutionary conservation of m6A binding ability in YTH domain-containing genes. Upon bacterial infection, LmDF3 and LmDC2 were observed to be significantly upregulated, whereas LmDC1 was significantly downregulated. Meanwhile, LmDF1b and LmDC1 were significantly upregulated in the skeletal muscle cells at the proliferation stage after exposure to different temperatures. Under different salinity conditions, LmDF1a was significantly downregulated, whereas LmDF1b and LmDC1 were significantly upregulated. These results indicated their important roles in responding to abiotic and biotic stresses. In addition, it was interesting that LmDF1a and LmDF1b, the duplicated copies, displayed opposite expression trends when treated with the same temperatures or salinity conditions. This study systematically characterized six LmYTH domain-containing genes, highlighting their conserved structures that enable interactions with m6A-modified RNA. Additionally, the findings suggest the potential functional divergence of LmDF1, requiring further investigations.

-

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research and Ethics Committees of Ocean University of China (Permit No. 20141201) and conducted in accordance with the relevant ethical guidelines. No endangered or protected species were involved in this study.

This study was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022QC086), the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (BX20240343), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202896), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32373104), the Key R&D Project of Shandong Province (2022ZLGX01), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M713001), the Marine Science and Technology Innovation Demonstration Project of Qingdao (23-1-3-hysf-2-hy), the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2021SFGC0701), and the Technology Plan Project of Tangshan (23130233E).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Zhu H, Tian Y; formal analysis: Zhu H; investigation: Zhu H, Qi X; resources: Zhu H, Yan C; software: Zhu H, Zhang J, Wang B; visualization: Zhu H; data curation: Zhu H, Yu H, Tian Y; writing – original draft preparation: Zhu H; writing – reviewing and editing: Gao Q, Tian Y; methodology: Li Y, Wen H, Gao Q, Tian Y; supervision: Li Y, Wen H, Gao Q, Tian Y; validation: Qi X, Lu Y, Yao Y; project administration: Gao Q, Tian Y; funding acquisition: Gao Q, Tian Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The transcriptome datasets analyzed in the current study were obtained from the NCBI database: PRJNA1093234 (Nocardia seriolae infection), PRJNA859992 (skeletal muscle cells under different temperatures), PRJNA841263 (Aeromonas hydrophila), PRJNA755166 (Aeromonas veronii), PRJNA557367 (temperature changes), PRJNA515986 (acute hypoxia) and PRJNA611641 (alkalinity stress).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primers of LmYTH domain-containing genes.

- Supplementary Table S2 Quantitative structural similarity.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Visualization of transcripts of LmYTH domain-containing genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Conserved motif analysis of LmYTH domain-containing genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Exon–intron organizations of LmYTH domain-containing genes. Yellow boxes represent exons, black lines indicate introns, and green boxes show the 5' or 3' untranslated regions (UTRs).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Chromosomal distribution of LmYTH domain-containing genes.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu H, Yu H, Li Y, Wen H, Qi X, et al. 2025. Evolutionary conservation of YTH domain-containing genes facilitating the functional achievement of m6A-modified RNAs under abiotic and biotic stresses in spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus). Genomics Communications 2: e020 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0020

Evolutionary conservation of YTH domain-containing genes facilitating the functional achievement of m6A-modified RNAs under abiotic and biotic stresses in spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus)

- Received: 21 May 2025

- Revised: 22 July 2025

- Accepted: 01 September 2025

- Published online: 24 October 2025

Abstract: YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing genes encode key reader proteins with the ability to recognize N6-methyladenosine (m6A) and mediate m6A-related biological functions. Despite their importance, YTH domain-containing genes have not been systematically investigated in the vast majority of teleosts. In the present study, six LmYTH genes were identified in spotted sea bass through homologous alignment and a conserved domain search. Comparative analysis revealed high similarity in gene structures, the YTH domain's distribution, and motif sites in homologous YTH domain-containing genes between mouse and spotted sea bass. Through a three-dimensional structural analysis of YTH domain-containing proteins between mouse and spotted sea bass, similarities were found in the α-helixes and β-strands components, identical tryptophan–tryptophan–tryptophan- or tryptophan–tryptophan–leucine-type aromatic cages for m6A recognition, and shared hydrogen bond formation. These results strongly supported the evolutionary conservation of YTH domain-containing genes between mammals and teleosts. RNA-seq datasets, together with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction experiments, revealed significant differences in the expression patterns of LmDF1a, LmDF1b, LmDF3, LmDC1, and LmDC2, implying their roles in response to abiotic and biotic stresses. Interestingly, LmDF1a and LmDF1b, a pair of duplicated genes, exhibited the opposite expression patterns, suggesting their potential function divergence in evolution. The present study offers a comprehensive perspective on LmYTH genes, unveiling their potential significance in response to abiotic and biotic stresses.

-

Key words:

- YTH domain-containing genes /

- m6A reader /

- Spotted sea bass /

- Immune response /

- Salinity stress