-

The study of plant sex chromosomes provides pivotal insights for understanding sex determination mechanisms and chromosome evolution. As early as the 1920s, Kathleen Bever Blackburn first identified morphologically distinct sex chromosomes in Silene latifolia, challenging the prevailing view that plants lack typical sex chromosomes[1]. Since then, diverse sex chromosome systems have been identified in numerous plant species[2−5]. Although animals are predominantly characterized by XY and ZW systems[6], plants exhibit remarkable diversity, including all the intermediate stages of evolution from monoecious to sexually differentiated phenotypes[7]. This diversity makes plants essential model systems for deciphering the mechanisms of sex chromosome evolution.

As one of the first plants from which a sex chromosome system was described, S. latifolia has been regarded as a model for studying the origin and degeneration of sex chromosomes. However, the highly repetitive nature of the Y chromosome and the extensive expansion of the nonrecombining region have long limited progress in resolving its structural and functional attributes[8]. Recent research has highlighted S. latifolia once more, with Akagi et al. (2025) and Moraga et al. (2025) having comprehensively characterized the important structural and functional features of the giant Y chromosome of S. latifolia. These two studies not only completed a technological feat by assembling a high-quality sequence for one of the most difficult to resolve chromosomes known in plants, but also redefined our theoretical understanding of the formation, expansion, and functional alteration of plant sex chromosomes.

Moraga and her colleagues[9] employed Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing, combined with Hi-C chromosome conformation capture technology, to obtain the most comprehensive draft of the male genome of S. latifolia, with a Y chromosome size of nearly 500 Mb, which is the largest assembled Y chromosome in a plant to date. By conducting a high-quality genomic comparison analysis of closely related Silene species as outgroups, which exhibit hermaphroditic or gynodioecious reproductive systems, consistent with the ancestral state inferred for the genus, they deduced the evolutionary history of the sex chromosomes of S. latifolia. They found that the Y chromosome contains at least three evolutionary strata, which were formed around 12, 5.4, and 4.4 million years ago, revealing a gradual expansion of recombination suppression regions in the Y chromosome. Moreover, similar stratification patterns have also been documented in spinach (Spinacia oleracea and S. turkestanica)[10]. These structural features are highly similar to the "staged stratification" pattern of animal Y chromosome evolution, suggesting that sex chromosome evolution may be conserved across kingdoms in terms of large-scale mechanisms. In addition, they found that the reduced expression of Y-linked genes was associated with CHH-type hypermethylation and 24-nt small RNA enrichment in the promoter region, and finally identified the candidate sex-determining genes. This high-quality assembly of X and Y chromosomes provides new insights into the evolutionary mechanism of suppressing recombination among the sex chromosomes in S. latifolia.

Complementing the work by Moraga et al., the research of Akagi et al.[11] focused on reconstructing the trajectory of the Y chromosome's degeneration at the functional level. They found some differences in the Y chromosome's structure in S. latifolia from different regions and a lower frequency of recombination in most regions of the X chromosome in female meiosis. On the basis of the age of the evolutionary strata and functional assays, they inferred a stepwise model of sex chromosome evolution. The initial establishment of dioecy was triggered by a stamen-promoting factor (SPF) mutation producing females, followed by the appearance of a closely linked gynoecium-suppressing factor (GSF, SlCLV3) mutation. Selection pressure drove the suppression of recombination between the X and Y chromosomes (Stratum 0), which was further reinforced by subsequent hitchhiking selection of sexually antagonistic genes (e.g., SlBAM1). Recombination loss promoted bursts of transposable element (TE) proliferation, particularly long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (gypsy and unclassified), leading to structural rearrangements and the progressive expansion of the male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY). The formation of Stratum 1 may have involved chromosomal inversions or fusion events that linked Stratum 0 to a location near the pericentromeric or pseudoautosomal region (PAR). While the Y chromosome was still undergoing active degeneration and rearrangement, dosage compensation of X-linked genes had already begun to evolve in Stratum 0 and Stratum 1. Male X-linked alleles are transcriptionally upregulated to counterbalance reduced Y expression, whereas the younger stratum (Stratum 2) shows little or no evidence of compensation. At this time, the evolutionary dynamics of Stratum 2 remain unclear, and the closely related species S. dioica has not yet formed this stratum. In addition, the Y chromosome has undergone extensive gene loss and expression silencing, with more than half of the ancestral genes being inactivated alongside a general reduction in the transcriptional levels of the remaining genes. The nonrecombinant regions of the Y chromosome are populated by numerous transposable elements and repetitive sequences, and are enriched in small RNAs and DNA methylation marks, collectively forming a highly heterochromatic and transcriptionally silent domain. This type of structural expansion, coupled with functional erosion, exemplifies the canonical degenerative trajectory of Y chromosomes[12].

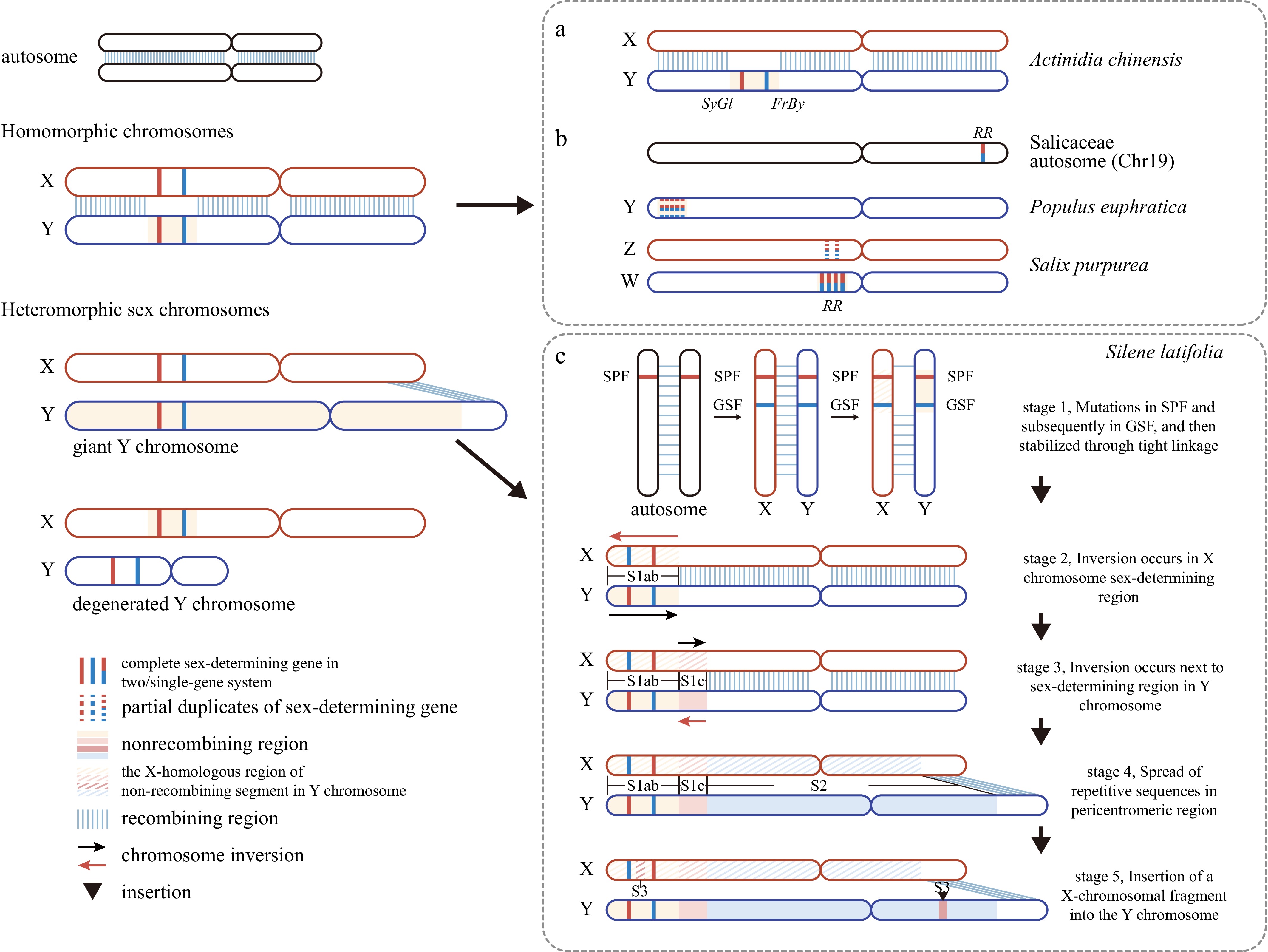

Together, these studies corroborate each other and collectively depict the formation of plant Y chromosomes as a multistage and systemic evolutionary process[13]. It typically begins with the emergence of a sex-determining factor, which may originate from a new copy or mutation of a functional gene on an autosome that triggers the suppression of recombination between the corresponding regions of homologous chromosomes. Subsequently, linkage of sexually antagonistic genes to the sex-determining region is maintained by selective forces, resulting in a progressive suppression of recombination between the region and those in its homologous chromosomes[14]. Inhibition of recombination then promotes the rapid accumulation of repetitive sequences, including LTR retrotransposons, DNA transposons, satellite sequences, etc., which both accelerates the expansion of chromosome size and further prevents homologous recombination of chromosomes. These successive changes facilitate the accumulation of degenerated or nonfunctional genes caused by mutations, whereas ongoing structural rearrangements further disrupt genomic integrity. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, such as promoter methylation and chromatin remodeling, are progressively inactivated or silenced, ultimately leading to the formation of a highly heterogeneous and transcriptionally inert chromosomal state[15]. At the same time, dosage compensation mechanisms evolve on the X chromosome to partially compensate for the decline in Y chromosome expression[16]. The giant Y chromosome of S. latifolia provides one of the clearest examples of the evolution of this process. In contrast, other plant species such as kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis)[17,18] possess largely homomorphic sex chromosomes or remain at intermediate stages of sex chromosome evolution, exhibiting neither pronounced structural heterogeneity nor substantial functional degeneration. Thus, the Y chromosome of S. latifolia represents not only an extreme case but also a pivotal reference point for testing models of sex chromosome evolution.

Although the degeneration of Y chromosomes follows a broadly conserved trajectory, considerable variation and deviations exist in plant lineages. In some species, the sex-determining region underwent "turnover," where new sex determination factors emerged and replaced the old mechanism at different genomic positions[3,19]. A representative case from the willow family (Salicaceae) is the conversion between XY and ZW systems regulated by the RR gene[20,21]. In polyploid plants, the sex determination system may be reshaped by genomic conflicts, dosage imbalances, or epigenetic reprogramming. For example, both weeping willow[22] and persimmon[23] exhibit a combined strategy involving chromosomal turnover and mechanistic rewiring. These atypical cases highlight that sex chromosomes' evolution in plants is not strictly linear or irreversible, but is instead characterized by substantial mechanistic flexibility and evolutionary plasticity.

Technically, these two studies demonstrate the potential of integrating next-generation sequencing platforms such as PacBio HiFi, ONT and Hi-C, with multi-scale genomic analytic approaches. Such integration not only advances the assembly of highly repetitive and structurally complex chromosomes, but also enables comprehensive characterization of nonrecombining and transposon-rich regions harboring regulatory elements. Future studies incorporating single-cell transcriptomics, methylomics, and spatial chromatin conformation analyses may elucidate the dynamic behavior of sex-determining regions across tissues and developmental stages.

Overall, the studies by Akagi et al. and Moraga et al. mark a significant advance in the field of research into sex chromosomes in plants. These works not only achieve a comprehensive, high-resolution analysis of the complex Y chromosomes but also provide empirical support for the structure-driven functional degeneration model of Y chromosomes' evolution. As an evolutionary extreme, S. latifolia offers new insights into the origin, diversification, and evolutionary trajectories of plant sex determination systems (Fig. 1). Beyond their fundamental contributions to our understanding of sex determination mechanisms, these findings also lay a theoretical foundation for applied strategies in sex control and resource allocation in agricultural breeding programs. However, several questions remain. How universal is the observed three-stratum (or more) structure? Do repetitive elements on the Y chromosome exhibit distinct functional roles or experience different selective pressures compared with those on autosomes? Can suppressed recombination regions on sex chromosomes be reactivated, and under what evolutionary or genomic contexts might such reactivation occur? What is the outcome if reactivation occurs? These questions call for integrative approaches combining comparative genomics, epigenetics, genome editing, and developmental biology.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of homomorphic and heteromorphic sex chromosome systems in plants. (a) Kiwifruit shows a homomorphic XY system, where sex is determined by the Y-linked genes SyGl and FrBy. (b) Sex chromosome turnover in Salicaceae. In Populus euphratica (poplar), an XY system is encoded on chromosome 19, whereas in Salix purpurea (willow), a ZW system has evolved on the same homologous region, with the sex-determining gene RR relocated to the W chromosome. (c) Stepwise evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes in S. latifolia. Stage 1: Sequential mutations in SPF and subsequently in GSF establish a sex-determining locus stabilized by tight linkage. Stage 2: A paracentric inversion occurs in the sex-determining region on the X chromosome (Stratum 1ab). Stage 3: An additional inversion arises in the corresponding region on the Y chromosome (Stratum 1c), consolidating recombination suppression. Stage 4: Repetitive sequences and transposable elements accumulate and spread around the pericentromeric region, driving expansion of the nonrecombining region (Stratum 2). Stage 5: Further structural change involves the insertion of an X-derived fragment into the Y chromosome, contributing to the formation of Stratum 3. Stamen-promoting factor, SPF; gynoecium-suppressing factor, GSF.

HTML

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32460303).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tang L; data collection: Peng D; draft manuscript preparation: Peng D, Tang L, Tembrock LR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Peng D, Tembrock LR, Tang L. 2025. From homomorphy to heteromorphy: stratified trajectories of sex chromosome expansion in Silene latifolia. Genomics Communications 2: e021 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0021 |