-

Nepal, a landlocked and predominantly agricultural country, has 62% of its households engaged in farming[1]. Agriculture plays a vital role in the national economy, contributing approximately 25% to the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Among various crops, potato stands out as one of the fastest-growing staple and cash crops, offering higher productivity and economic value compared to major cereals. As such, it holds significant potential to improve food security and reduce poverty, particularly among smallholder farmers.

Potatoes are cultivated across Nepal's diverse agro-ecological zones, ranging from the low-lying Terai plains at 100 m above sea level to high mountain regions reaching 4,400 m. They are grown either as a sole crop or intercropped with maize in both upland (bari) and lowland (khet) farming systems. The mid-hills dominate potato cultivation, accounting for 41.5% of the total area, followed by the Terai (38.5%), and highlands (20%)[2]. In the hills, potatoes primarily serve as a staple food, while in the Terai, they are mainly cultivated as a cash crop. In 2021/22, winter potatoes were grown by 1,336,616 holdings over 61,033.4 ha, while summer potatoes were cultivated by 483,645 holdings on 37,697.9 ha[1].

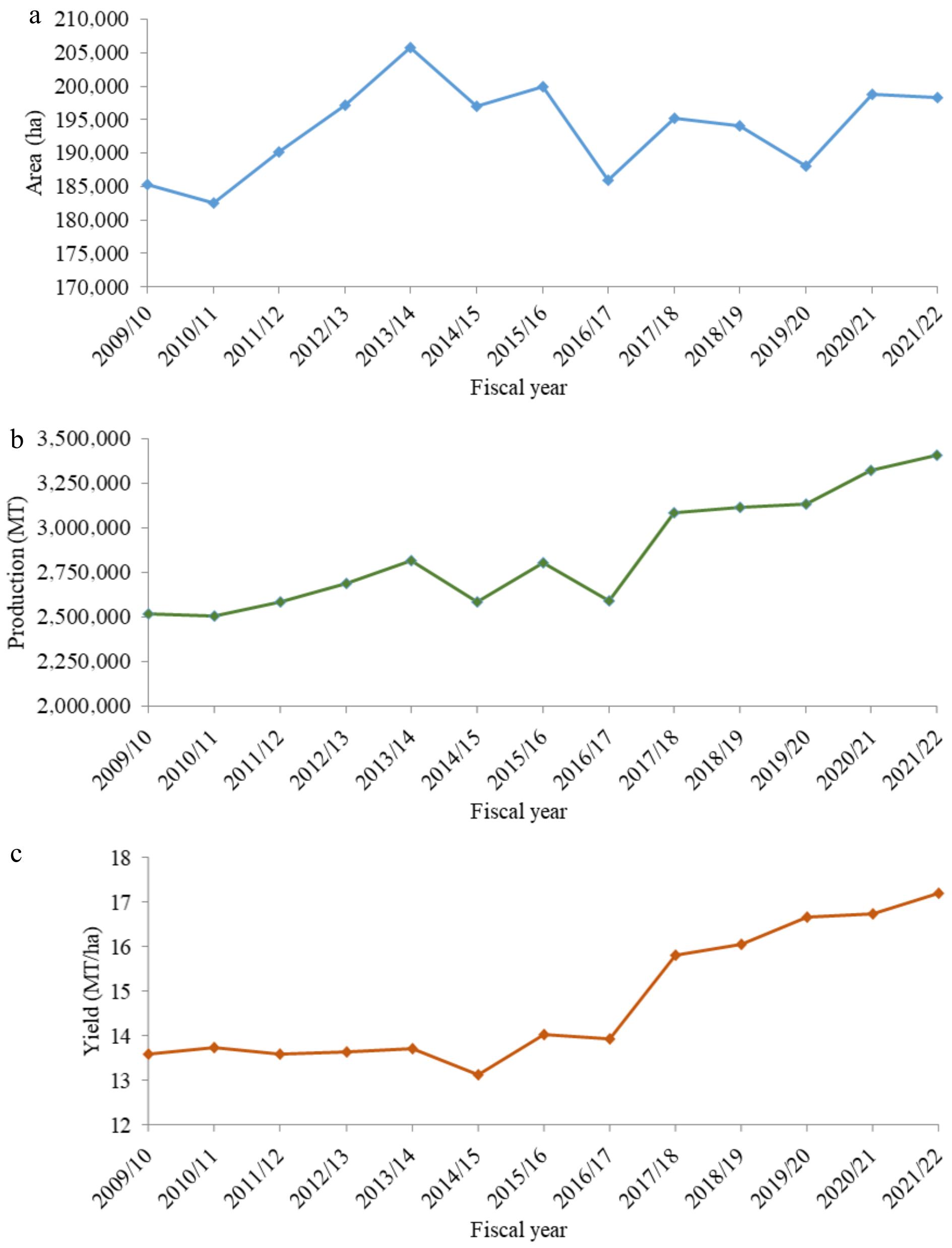

Horticulture and cash crops contribute between 25% and 35% of agricultural GDP (equivalent to 16.29% of national GDP), with potatoes alone contributing 7.36%[3]. Overall, cash crops cover a total area of 529,800 ha with an average productivity of 13.95 MT/ha, and a total production of 6,806,810 MT. Specifically, the potato has a productive area of 198,788 ha (37.52% of the cash crop area) with 16.73 MT/ha productivity and 3,325,231 MT production during 2020/21[3]. Figure 1 illustrates trends in area, production, and yield over the past 13 years. As shown in Fig. 1, a sharp decline in potato cultivation around 2016/17 can be attributed to several factors, including severe impact of the 2015 earthquake, fuel crisis and prolonged border blockade (2015–16), climate disruptions, weak agricultural policy support, inadequate storage infrastructure, and delays in decentralization post constitution (2015). But the subsequent recovery afterward, correlates with post-earthquake recovery schemes on restoration of infrastructure, agricultural tools and inputs, stabilized supply chains and fuel access, improved markets, and local government subsidies for fertilizer and seed distribution. Despite growing domestic production, Nepal imported potatoes worth NRs 8.9 billion in 2020/21 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table S1), indicating persistent supply-demand gaps. Therefore, given its adaptability, wide cultivation range, and economic importance, potato production remains a key strategy for meeting Nepal's growing demand for fresh and processed foods in an evolving socioeconomic landscape.

-

Holistic potato mechanization covers the entire production chain, from land preparation to post-harvest handling. Accordingly, this section explores current mechanization technologies and identifies the corresponding gaps, bottlenecks, and constraints across all stages of potato farming, including tillage, seed cutting, planting, weeding, irrigation, harvesting, and storage. Table 1 summarizes the existing region-specific agricultural equipment, highlights key operational challenges, and outlines future technology needs for improving potato cultivation in Nepal. Meanwhile, Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the multifaceted bottlenecks and constraints i.e., economic, technical, social, environmental, infrastructural, institutional, and policy-related factors that collectively hinder the adoption of mechanization technologies.

Table 1. Summarized technological breakdown and associated bottlenecks of agricultural equipment for various stages of potato production process in Nepal.

Stage Purpose/function Region specific technologies Adoption region/status Key bottlenecks and constraints R&D priorities/tech suggestions Land preparation Break soil, incorporate organic matter and level the field a) Terai: tractor, plough, harrow, rotavator, laser land leveler;

b) Hill: mini tiller, power tiller# Power tillers and tractors common in Terai; mini tillers fit hills; laser levelers rare # Steep slopes; high costs; limited credit; fragmented plots; poor infrastructure; lack of local machinery # Mechanized, better than other operations, expand mini tillers or small tillage tools for small terraces Seed bed preparation Make furrows/ridges for better root and tuber growth a) Terai: tractor mounted bed former, ridger;

b) Hill: power tiller bed former and mini tiller ridger, manual spade-based beds# Tractor-mounted units moderately used in Terai and mid-hills; mini tiller bed formers under NARC research # No hill-compatible machinery; limited R&D and promotion; poor training and fabrication support # R&D for hill-specific equipment, increase field demos across agro-ecologies Seed cutting and treatment Cut large tubers into seed pieces and treat with fungicides/

insecticidesTeri and hill: knife and sickle, manual/chemical seed treatment, Hand sprayers # Dominant in all regions; mechanical seed cutters not in use # Sanitation risks from manual cutting; no small-scale seed cutters; limited innovation and commercialization # Research on mechanical cutter design and testing Planting Precisely plant seed tubers at correct spacing and depth a) Terai: hand tools and automatic or semi-automatic potato planters;

b) Hill: hand tools# Traditional in hills; partially mechanized in Terai (NARC & PMAMP-supported). # No hill-suited planters; no mechanized bung system; limited credit and R&D support; seasonal use only # Increase demonstration of verified planters in Terai; and in-depth research on hill suitable small potato planter or tools Weeding and intercultural operations Control weed, aerate soil and maintain ridges Terai and hills: manual tools (hoe, spade), dry land weeder, animal-drawn tools, mini tillers (limited use), mulching (plastic/straw) # Manual everywhere; some mini-tiller use in Terai/mid-hills; mulching emerging in commercial zones # No potato-specific weeder; CHCs lack targeted tool; insufficient training; mulching barriers # Testing and promoting mechanized/semi-mechanized weeders, ridgers, and cultivators in Terai; lightweight power weeders for hills Plant protection Apply fertilizers and chemicals uniformly a) Terai: knapsack sprayer, power sprayer, boom sprayers;

b) Hill: small hand compression sprayer, knapsack sprayer# Basic tech like knapsack sprayers common; advanced methods (drones, electrostatic sprayers) # Limited research and promotion of modern tools; high cost and technical complexity; lack of custom equipment for TPS and smallholders # Integrate fertigation in potato farming; expand demonstrations of boom sprayers, precision sprayers, and drone trials Irrigation and fertigation Provide adequate and uniform irrigation water to crop Terai and hill: sprinklers/drip, solar pumps, pumps (centrifugal, turbine, submersible, axial flow, mixed flow pumps), mini tiller-operated pump, flood and canal systems; # Traditional in hills; drip/sprinkler in Terai/mid-hills; solar pumps rising; manual fertilizer broadcasting # Energy access and cost issues; no long-term economic studies; technical support lacking; limited subsidies in remote areas # Increase demos of mini-tiller pumps and economic feasibility study of drip/sprinkler/solar pumps; research fertilizer broadcasting equipment Harvesting Lift tubers from the soil with minimal damage a) Terai: tractor mounted potato diggers or power tiller digger;

b) Hill: power tiller or mini tiller digger, manual tools (hoe/spade)# Manual in hills; mechanized digging in Terai and mid-hills flatlands Poor terrain fit; high costs; manual collection required; no customization for small plots # Research and promote hill-suitable tech; adopt ridge-furrow cultivation in valleys; and demo potato harvesters in hills and Terai Post-harvest processes Clean, sort, package, and store harvested or seed potatoes Manual grading and sorting, manual roller drum grader (NAERC), traditional storage (pit, room-floor), cold storage # Manual dominates; low adoption of cold storage, mostly (70%) in central region # Non-specific grader designs; technical complexity; high energy and cost, limited storage; poor hill transport; and low processing equipment adoption # Need affordable manual/motorized graders and reliable cold storage for small farmers; design low-power gravity/vibration systems (battery/solar); promote low-cost evaporative/insulated storage; support group-owned cold chains Protected cultivation for seed production Produce disease-free seeds Screen houses, tissue culture, aeroponics and TIS (limited use), UV-treated irrigation # Low adoption; used by NARC, KU, NPRP, few private farms; mainly in research, pilot, or demo stages # High costs and skill gaps; lack of affordable systems, skilled labor, equipment; no clear farmer scale-up roadmap # Yet to scale, research on low-cost protected structure Table 2. Categorized bottlenecks and constraints in potato mechanization of Nepal.

Category Bottlenecks/constraints Impact Economic and financial barriers ● High initial investment

● Socio-economic constrictions (gender, land & income)

● Energy and fuel dependency

● Poor access to credit and insurance

● Custom hiring monopolies with limited, costly, and poorly monitored services

● High import tax on parts and raw materials (15%–30%)● Unaffordable

● Restricts investment

● Raises operational costs

● Restricts local manufacturingTechnical, operational and infrastructure deficiencies ● Lack of appropriate machinery for small farms

● Incompatibility with local soil conditions

● Technical skill gaps; limited spare parts, skilled mechanics, and maintenance services

● Low technical capacity of farmers/operators

● Crop damage from mechanized harvesting

● Weak infrastructure (roads, irrigation, electricity, and storage)

● Higher post-harvest losses (20%–30%)● Disrupt the value chains

● Reduce machine efficiency

● Delay cultivation

● Reliance on ineffective methods

● Duplication of effortsAgricultural and production constraints ● Supply chain bottlenecks (input, seeds, irrigation, labor)

● Pests and diseases (e.g., blight, aphids, wilt)

● Weak seed system

● Traditional cropping methods e.g., comb beds

● Environmental concerns (degradation, erosion, emissions, climate change)● Reduce yield, quality, and profits

● Raise costs, harm environment

● Limit machine useTopographical and farm structure limitations ● Steep, narrow terrain with rugged terraces

● Fragmented smallholdings (avg. parcel size: 0.24 ha, 3.27 parcels/farm)

● Predominantly rainfed, subsistence farming● Limits technological adoption Policy, governance, and institutional issues ● Absence of clear federal-aligned policies and standards

● Weak research–extension–education coordination

● Poorly resourced mechanization institutions● Duplication of efforts

● Limit the research and innovationPrivate sector and industry limitations ● Decline of traditional artisans (blacksmiths)

● Lack of government-supported manufacturing

● Financial/technical limits for Small Machinery Entrepreneurs (SMEs)

● Urban-focused importers and suppliers● Import dependence

● Costly local products

● Limited rural access to tech and servicesSocial and labor dynamics ● Traditional comb-type beds

● Shortage of skilled agri-labor

● Youth migration and cultural resistance

● Gender/income gaps; lack of inclusive tools

● Socioeconomic inequalities● Burdens women and elderly

● Restricts machine use

● Excludes marginalized groups

● Fosters resistance to changeLand preparation

-

Land preparation is a crucial step in potato cultivation, essential for enhancing soil health and ensuring effective water management[5]. Traditionally, Nepali farmers relied on draught animals and wooden tools. In recent years, however, the Terai region has increasingly adopted mechanized methods, including power tillers, four-wheel tractors with attachments, and, to a limited extent, laser levelers (134 units as of 2019)[6]. This shift is more pronounced in the Terai due to its flat terrain, larger farm sizes, heavier soils, and better access to rental services, infrastructure, and repair facilities. In contrast, mechanization in the hill regions remains limited, hindered by steep slopes, fragmented landholdings, inadequate infrastructure, and high machinery costs. In these areas, mini-tillers are gradually replacing oxen, as they are more maneuverable on small and sloped plots (Fig. 2b). Their compact size, affordability, and compatibility with narrow terraces make them particularly suitable for remote, rugged areas with limited infrastructure and maintenance services. Despite this progress, many remote hill communities still rely on manual tools like spades. This ongoing dependence is largely driven by financial barriers, high fuel costs, limited access to credit and rental markets, and the absence of repair services. Furthermore, imported machinery is often ill-suited to local terrain, and the absence of supportive policies along with an underdeveloped market for locally adapted tools continues to impede the advancement of mechanization in Nepal's hill agriculture.

Seed bed preparation (bed forming)

-

Bed forming is essential in potato cultivation for ensuring proper soil structure, drainage, and root development. Tractor-operated bed formers and ridgers are increasingly used, particularly in the Terai and flat mid-hill regions, where they create raised beds ideal for large-scale farms. However, steep hill areas still rely primarily on manual tools like spades due to the lack of suitable mechanized options. In these areas, ridgers or bed formers mounted on power tillers or mini tillers offer affordable and maneuverable alternatives for small, fragmented mid-hill plots.

For instance, a power tiller bed former developed by AED/NARC (Fig. 3b) has shown promising results, achieving a field capacity of 1.6 ha/d, significantly outperforming manual spade-based methods, which require around 15 labor-days per hectare[7]. Despite these advantages, adoption remains limited due to insufficient field trials, limited research dissemination, high costs, and a lack of local fabrication support. Furthermore, the absence of supportive policies and technical training restricts wider technology uptake, leaving many smallholders dependent on labor-intensive methods. Therefore, future efforts should prioritize lightweight equipment for hilly terrains, promote local fabrication, and integrate seedbed preparation into broader mechanization strategies for potato cultivation.

Figure 3.

(a) Comb type bed forming using spade. (b) Power tiller bed former. (c) Mini tiller ridger.

Seed cutting and seed treatment

-

Adoption of potato seed cutting and treatment equipment remains very low, despite its critical importance for disease prevention and yield improvement. While whole tubers (40–50 g) are preferred to minimize disease transmission, many farmers cut larger tubers into smaller pieces to reduce seed costs. This cutting is typically done using traditional tools such as knives and sickles, which consequently increases the risk of disease spread. Furthermore, seed treatment methods are largely semi-manual and involve practices such as fungicide dips, curing with ash or Bordeaux mixture, sun-sprouting, and chemical spraying using hand sprayers.

The use of mechanical seed cutters is rare, mainly due to high costs, lack of small-scale equipment, limited awareness of disease risks, and insufficient technical knowledge. These challenges are further compounded by limited research, ineffective extension services, and the absence of equipment suited for hilly terrain. Consequently, no widely adopted models currently exist for small-scale, hill-based farming systems. This highlights a significant opportunity to develop affordable, hill-adapted seed cutting and treatment technologies tailored to the needs of resource-constrained farmers.

Planting

-

Potato planting methods vary by region: traditional 'Bung' and 'Lhose' are commonly used in the hills, while furrow and row planting dominate in the mid-hills and plains. Although these hill practices are effective, they tend to be labor-intensive[2]. The Bung method, in particular, holds indigenous value but lacks mechanical support. In contrast, the adoption of potato planters (Fig. 4) in the Terai region is driven by benefits like reduced labor, increased efficiency, better yield, government support, and access to credit, especially among larger commercial farmers. Additionally, semi-automatic and automatic tractor-mounted planters, which were previously limited in use, are now gaining traction in the Terai with support from NARC and PMAMP.

Figure 4.

Potato planter (adapted from Rajbansi[8]).

However, adoption remains limited in hill areas due to a lack of terrain-specific R&D, high machine costs, poor coordination, and minimal access to custom hiring services. Furthermore, no machinery currently exists for traditional methods like Bung, underscoring the urgent need for targeted innovation and localized tool development.

Weeding and intercultural operations

-

Weed control is vital in potato farming, as weeds compete for nutrients, water, and light, thereby reducing yield and quality. Despite its importance, the adoption of weeding and intercultural tools remains minimal. Manual methods, such as hoes and hand tools (Supplementary Fig. S1), continue to dominate across regions, primarily due to terrain challenges, economic constraints, and design limitations. While herbicides are moderately used in the Terai region, animal-drawn tools still persist in the mid-hills. In contrast, mechanized options such as mini-tillers and power weeders have seen limited adoption, and Custom Hiring Centers (CHCs) rarely provide potato-specific implements. In particular, power weeders have low uptake due to design limitations and the absence of region-specific adaptations. This restricts productivity and increases labor demands, placing a disproportionate burden on women and elderly farmers. Though some innovation exists, such as NAERC's manual dry-land weeder, its adoption remains low, largely due to limited dissemination, inadequate training, and poor availability.

Meanwhile, mulching with straw or plastic is emerging as an alternative weed control method. However, its wider use is hindered by factors such as high cost, labor intensity, environmental concerns, and management complexity. Furthermore, the lack of targeted research and development, field validation, and extension support has left intercultural operations largely manual. The absence of support for local tool design and production further restricts adaptation, while environmental concerns and knowledge gaps continue to hinder the adoption of sustainable alternatives such as biodegradable mulch. Therefore, advancing the adoption of effective weed management practices requires a multi-pronged approach: promoting the use of biodegradable mulches, enhancing farmer training, integrating eco-friendly practices, and developing affordable, locally designed tools through stronger collaboration between research institutions and grassroots-level fabricators.

Plant protection

-

Potato crops are highly susceptible to various biotic stresses, including insect pests, viral pathogens, bacteria, and fungi. Common insect pests include tuber moths, aphids, and cutworms, while major viral diseases comprise Potato Leaf Roll Virus, Potato Virus A, M, Y, and X, as well as Aucuba Mosaic Virus. Bacterial infections (e.g., wilt and brown rot), and fungal diseases (e.g., blight and wart) are also prevalent[9]. These stresses cause leaf curling, yellowing, tuber rot, and skin spotting, leading to significant losses in both yield and quality.

In Nepal, the availability of compact and affordable plant protection equipment has improved mechanization among smallholder farmers. Most rely on basic sprayers, such as compression, foot, and knapsack types (manual or battery-operated), as well as portable power sprayers to apply agrochemicals (Supplementary Fig. S2). Globally, advanced spraying technologies such as drones, boom sprayers, and electrostatic sprayers are widely adopted for their precision and efficiency. However, their use in Nepal remains limited due to high costs, lack of localized research and training, absence of national standards, and weak institutional support. Consequently, pesticide application often suffers from uneven coverage, overuse of chemicals, and increased health risks. Introducing advanced spraying systems and greenhouse fogging or misting technologies for True Potato Seed (TPS) production holds significant promise. Successful adoption, however, will require targeted research, local adaptation, and capacity building.

Irrigation and fertigation practices

-

Potatoes have shallow roots and are highly sensitive to water stress, which can lead to reduced yields and disorders like hollow heart and internal brown spots. Therefore, adequate and consistent irrigation is crucial for optimal growth. Traditional methods like flood irrigation and canal systems remain dominant, especially in rural and mountainous areas (Supplementary Fig. S3b and S3c). Meanwhile, modern techniques such as drip irrigation, sprinkler irrigation, and fertigation are gradually gaining ground among progressive farmers and commercial farms. However, high costs, limited technical support, and energy access issues hinder wider adoption. Although these modern systems hold promise for water-scarce regions, their technical and economic feasibility for potato cultivation requires in-depth research. To address this, government initiatives and donor-funded projects have started promoting micro-irrigation and fertigation, particularly in the Terai and mid-hill regions. Additionally, the use of mechanized pumps including electric, diesel, mini tiller-attached, and solar-powered models is growing in Nepal. The adoption of such machinery is driven by increasing water scarcity, a shift toward high-value crops, government subsidies, rising commercial crop production, improved farmer training, better access to technology and credit, and labor-saving benefits. Nonetheless, lack of long-term economic assessments, especially for solar irrigation systems in off-grid or water-scarce areas, has stalled broader uptake. Therefore, comprehensive feasibility studies are crucial for scaling sustainable irrigation technologies.

Harvesting

-

Potato harvesting in Nepal remains largely manual, relying on tools such as spades and hoes, which makes the process labor-intensive and physically demanding[10,11]. Mechanized harvesters such as four-wheel tractor-mounted digger, power tiller digger, and mini-tiller digger are gradually being introduced in the Terai and mid-hills, offering significant labor savings and efficiency gains. However, their adoption is limited due to high investment costs, limited availability of spare parts, topographical barriers, unsuitable cropping patterns (e.g., comb-structured beds), and insufficient training. Moreover, the hilly terrain and fragmented plots often do not support straight-bed planting, which most mechanical harvesters require. As a result, mechanization is largely confined to flatlands with straight-bed systems, while manual harvesting continues to dominate in hill areas and small plots. Currently, the following harvesting tools are in use across Nepal's various agro-ecological zones:

• Manual harvesting: Most common in hills, achieves a rate of 0.21 ropani/hour using a spade (Fig. 5a), requires 15 labor-hours/ropani, with very low tuber damage (< 1%).

Figure 5.

(a) Manual digging. (b) Mini tiller digger. (c) Collection of digger harvested potatoes. (d) Power tiller digger. (e) Four-wheel tractor attached potato digger (Image 'e' adapted from Bidari[13]).

• Mini tiller digger: Suitable for hills, has a field capacity of 1 ropani/h, requires around 5 labor-hours/ropani, causes minimal tuber damage, but necessitates straight bed planting (Fig. 5b).

• Power tiller diggers: Suitable for mid-hills and plains, covers 1–1.5 ropani/h, exposes ≥ 96% of tubers with ≤ 1% loss, and reduces labor by approximately 50% compared to manual harvesting (Fig. 5d).

• Four-wheel tractor digger: Effective in the Terai, digs two rows simultaneously, covers 0.23 ha/h, saves around 60% of labor, causes < 1% tuber skin damage, and about 7 kg/ha loss in small tubers (Fig. 5e)[12].

Despite these technological advancements, all mechanical diggers still require manual collection of exposed tubers, which reduces the overall labor-saving potential and prevents full mechanization. Additionally, the usability of these machines is influenced by factors such as bed structure, soil type, and operator skill. To close the mechanization gap, it is essential to promote slope-compatible machines, improve operator training, and encourage cooperative-based ownership models. These efforts should be reinforced through adaptive research and targeted investment in rural infrastructure to ensure sustainable and inclusive adoption.

Post-harvest processes

-

In Nepal, potato grading is predominantly carried out manually, based on size, shape, and color. The use of mechanized graders is rare due to their high cost and limited availability. The manual roller drum grader developed by NAERC (Supplementary Fig. S4) performs effectively for round-shaped potatoes but tends to cause bruising in elongated varieties. To address this, protective modifications such as foam lining and pipe coverings are recommended to reduce damage and enhance performance[7]. Despite their potential, mechanical graders have not yet been widely commercialized, primarily due to incompatibility with the diverse shapes of potatoes grown in Nepal. Similarly, traditional packaging and transportation methods such as wooden crates, jute bags, bamboo baskets, and manual porters dominate the potato value chain, especially in the hills. Transportation modes vary geographically, with tractors commonly used in the Terai and manual carriers in the hills.

Storage methods also differ depending on location and climate, ranging from pit and room-floor storage to Zero Energy Cool Chambers and cold storage facilities[10,14]. However, cold storage capacity remains limited to approximately 87,700 metric tons, with nearly 70% concentrated in the central region. This regional imbalance restricts year-round potato marketing and contributes to seasonal gluts and shortages[15]. Processing equipment such as peelers, slicers, and chip-making machines is becoming more common, although its use remains largely confined to urban markets. Overall, the modernization of Nepal's potato post-harvest system is constrained by high machinery costs, poor infrastructure, limited cold storage, and weak value chain integration. To reduce post-harvest losses and improve farmer incomes, it is essential to improve access to affordable technologies, strengthen rural transport networks, and promote decentralized storage solutions.

Agricultural structures for protected cultivation (seed production)

-

Virus-free, healthy seed tubers are vital for increasing potato yield. Since seed-borne diseases spread rapidly and lack effective chemical controls, the use of disease-free seeds, crop rotation, and regular field inspection is critical. In this context, protected cultivation structures such as screen houses are widely utilized in Nepal for pre-basic seed (PBS) production, offering a more cost-effective alternative to glasshouses[15]. Furthermore, advanced propagation techniques such as tissue culture, micro-propagation, and aeroponics or hydroponics are still under research and have not yet been widely adopted. The Potato Research Wing of NARC at NPRP, Lalitpur, is equipped with advanced laboratories and protected cultivation infrastructure, including tissue culture labs, growth chambers, and UV-treated irrigation systems[16,17] (Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition, institutions such as NARC and Kathmandu University have begun the limited implementation of aeroponic and Temporary Immersion System (TIS) technologies to produce high-quality, virus-free mini-tubers.

However, despite these efforts, broader adoption of such technologies beyond research institutions is constrained by high initial costs, technical complexity, and a shortage of trained personnel. Moreover, in rural areas, infrastructure and operational support for high-tech seed systems are still underdeveloped. Institutional fragmentation, inadequate policy backing, and limited public-private collaboration further hinder the scaling of protected cultivation systems. To address these challenges, future research should prioritize the development of affordable and efficient seed systems tailored to Nepal's diverse agro-ecological zones. Specifically, adaptive trials for aeroponics, cost-reduction strategies, technical training programs, and localized capacity-building initiatives are essential. Additionally, scaling these high-potential technologies will require targeted subsidies and stronger support mechanisms specifically designed to benefit rural farmers.

Cross-cutting constraints to mechanization adoption in potato farming

-

Table 2 presents the categorized bottlenecks and constraints in potato mechanization of Nepal. Additionally, cross cutting constraints are summarized as below:

Challenges of local agri-machinery and impacts on Nepal's R&D ecosystem

-

Locally developed agricultural machinery in Nepal faces low effectiveness due to a range of technical, operational, and systemic problems such as inconsistent performance, poor durability, lack of automation, and limited adaptability to diverse terrains. In addition, poor standardization, inadequate maintenance support, high production costs, and limited user training further hinder widespread adoption. These challenges reflect deeper flaws in Nepal's R&D ecosystem, including weak academia-industry-farmer linkages, underfunded research, limited innovation capacity, and overreliance on foreign models. Furthermore, fragmented institutional coordination, outdated educational curricula, cultural resistance to innovation, and inadequate infrastructure for product testing and refinement exacerbate these systemic weaknesses. Together, these interrelated challenges reflect a fragmented innovation pipeline that hinders the development of context-specific technologies, ultimately slowing agricultural modernization. Therefore, addressing these barriers requires a comprehensive approach, including strengthening institutional collaboration, increasing investment in research, integrating local knowledge systems, fostering participatory innovation, and enhancing policy frameworks and infrastructure. These reforms are essential to unlock Nepal's untapped R&D potential and drive sustainable progress in agricultural mechanization.

Impact of policy conflicts (import tariffs vs subsidies) on the agricultural machinery value chain

-

Nepal's dual strategy of low import tariffs and agricultural subsidies aims to promote mechanization. Initially, the 2010 Trade Policy offered minimal tariffs (1%) and VAT exemptions on machinery. However, concerns over misuse, particularly tractors being used for commercial transport rather than farming led to a 5% customs duty and a 13% VAT on four-wheel tractors (except power tillers and mini tiller) by 2017. Meanwhile, subsidies (ranging from 50% to 75%) expanded for machinery, fertilizers, crop insurance, and storage to support productivity and marginalized groups. Despite significant investment, the impact of tariff relief and financial incentives remains uneven due to weak enforcement, bureaucratic hurdles, favoritism, high costs, policy shifts, and lack of quality standards (e.g., engine HP issues in mini tillers).

Moreover, tariffs on raw materials (5%–30%) critically undermine local manufacturing. While subsidies are available for both local and imported machinery, high input costs make domestic production uncompetitive. As a result, subsidies disproportionately favor imports, discouraging local innovation, slowing adoption, increasing costs for farmers, and weakening the entire value chain i.e., from producers to repair services (Table 3). Ultimately, these policy misalignments raise reliance on imports, widen trade deficits, and stall sector growth. Therefore, aligning import tariffs, raw material duties, and subsidies is essential to unlock local capacity, improve farmer access, and ensure sustainable agricultural growth and resilience. A balanced policy mix includes reducing tariffs on non-domestically produced components and essential machinery, subsidizing inputs for local fabricators, enforcing quality standards, and shifting to outcome-based incentives to ensure inclusive sustainable mechanization.

Table 3. Policy conflict (import tariff vs subsidies) impact across the agricultural machinery value chain of Nepal.

Policy conflict impact Description Opportunities for alignment Import tariff level a) Agricultural machinery: 1%–5% (mostly1%) +VAT exemptions (except four wheel tractor and undefined machines).

b) Raw materials and spare parts: 5%–30%+ VAT + additional charges.Balanced policy mix:

a) Harmonize policies:

● Remove tariffs on raw materials and parts for agricultural machinery.

● Prioritize subsidies for local equipment.

● Offer performance-based manufacturer incentives (e.g. for durability, local jobs, sustainability).

b) Build local capacity:

● Invest in training and innovation hubs.

● Support joint ventures and tech transfer.

● Provide technical and financial aid to producers

● Establish quality standards and certifications

c) Targeted subsidies:

● Link subsidies to farm size, location, and income.

● Promote cooperatives using local machines.

● Subsidize raw materials for local fabricators.

● Apply outcome-based subsidiesSubsidies & incentives a) Subsidies for both imported and locally produced equipment (50%–75%).

b) Industrial incentives from mid-2022: 100% tax exemptions for 5 years from operations.Imported machines a) Positive impacts: enables affordable access to machinery, accelerating agricultural mechanization. Disruption across the value chain a) Raw material importer: import tariffs raise the cost of essential components and raw materials (e.g. steel, MS bar, engines, motor, bearings etc.), making local manufacturing less competitive. b) Local Manufacturers: despite tax breaks, high input costs and competition from subsidized imports hinder local production. c) Distributors/dealers: tariffs raise local machine prices, pushing dealers to prefer imports over domestic brands. d) Farmers: subsidies aid mechanization, but expensive local machines lead to import dominance and maintenance challenges.

e) Repair/service sector: inconsistent product mix (imported vs. local) complicates service and parts standardization, and raise maintenance expenses.Undermine strategic goals a) Import tariffs aim to protect local industry or generate revenue but raise costs for manufacturers reliant on imports, while untaxed assembled imports undercut them.

b) Agricultural subsidies boost mechanization but favoring imports over local products undermines domestic manufacturing growth.Stagnation of domestic industry a) Local manufacturers face high costs, limited finance, and unfair import competition.

b) Without strong domestic production, Nepal relies on imports, lacks local innovation, and suppresses job opportunities.Farmer-level impacts a) Affordability: subsidized imports can be costly for small farmers due to poor after-sales service and expensive parts.

b) Suitability: imported machines often mismatch Nepali terrain and small plots.

c) Maintenance: limited rural access to parts and repairs raises long-term costs.Macro-level effects a) Trade imbalance: import reliance drains foreign exchange.

b) Revenue vs development trade off: tariffs raise revenue but limit industry and farm growth.

c) Investor confidence: policy conflicts discourage agro-industry investment.Socio-cultural, labour dynamics, and demographic barriers

-

Potato farming is highly labor-intensive, requiring about 600 man-h/ha[5]. The agricultural workforce is aging and the number of female-headed households has significantly increased. For instance, the share of farmers aged 55–64 rose from 17.6% to 18.3%, and those 60+ increased from 11.4% to 13.7% between 2011/12 and 2021/22[1]. During the same period, male-headed farms decreased while female-headed farms rose from 19% to 32.4%. These changes have placed growing pressure on women, the elderly and even children to sustain farming operations. Simultaneously, rural labor shortages, rising labor costs, and a decline in animal traction have contributed to an increase in fallow land, particularly in hilly regions. Nepal's total arable land declined by 300,000 ha over the decade leading up to 2021[1]. While mechanization offers a potential solution to labor constraints, it may also deepen existing inequalities if not made accessible to women, smallholders, and marginalized groups.

Success stories of mechanization in potato cultivation

-

In Nepal, the use of machinery, especially potato planters and harvesters is a relatively new entrant in potato cultivation. Several successful cases of potato mechanization have emerged, serving as models for the future agricultural production. These examples highlighted the necessity of integrating machinery and supportive policies to enhance productivity and profitability in potato farming.

Example (1): Adoption of a potato planter and digger in the Bara district: Paras Thakur, a farmer from the Feta Rural Municipality, Bara has been using a tractor-mounted potato planter and digger for the past three years, with technical support from NARC. Recently, Mr. Thakur bought a potato planter machine with the partial municipal funding support. Recently, with partial funding support from his municipality, he purchased a potato planter. By offering custom hiring services to other farmers in the Parsa and Bara districts, he earned NRs 250,000 in just 15 d[18].

Example (2): Adoption of mini tillers in Dadeldhura: In the Dadeldhura district, the introduction of mini tillers significantly improved the efficiency of potato farming. Compared to traditional bullock-based methods, mechanized farming with mini tillers increased productivity, reduced costs, and boosted net profits per hectare. Mini tiller also lessened the labor burden, especially for women and demonstrated the financial viability and gender benefits of mechanized potato farming[19].

Example (3): Mechanization in the Kamal Rural Municipality, Jhapa: Under the PMAMP initiative, Kamal Rural Municipality adopted mechanized planters and harvesters, leading to remarkable improvements in efficiency and cost reduction. Planting time was reduced from one day to just 40 min per ropani, and production costs fell by 75%. Within a year, the area under potato cultivation doubled, and the number of participating farmers increased from 35 to 60. This example illustrates how government support and collective action can drive the successful adoption of mechanization in commercial potato farming[8].

These examples demonstrate the potential of mechanization to improve yields, reduce labor burdens, and promote sustainable growth in small-scale potato farming across Nepal. Continued investment in machinery, infrastructure, and supportive policies is essential to scale these successes and strengthen the agricultural sector.

-

The future of potato mechanization in Nepal depends on a variety of factors, including terrain, farm size, labor dynamics, and policy support. Implementing both short- and long-term strategies is essential to accelerate mechanization, improve farmer livelihoods, and strengthen national food security.

Short-term strategies

Promotion of public–private partnerships (PPPs) for sustainable mechanization

-

A coordinated approach among federal, provincial, and local governments, private companies, cooperatives, financial institutions, and NGOs/INGOs (e.g., CGIAR) is essential for effective agricultural mechanization. The government should create enabling policies, facilitate research and extension services, and provide training. Meanwhile, private actors should focus on importing, producing, and distributing validated technologies. Financial institutions must develop farmer-friendly credit systems. Pilot programs offering subsidized or rental machinery in key potato-growing areas such as Kavre, Makawanpur, Sindhupalchok, Ilam, and the Terai can support adaptation and demonstration.

Invest in R&D for small-scale, multi-functional technologies

-

Prioritize R&D of affordable and locally adapted tools, animal drawn implement and small machines suited for hills where full mechanization is challenging. For instance, farmers can use hiller/furrower attachments for ridge planting and equip mini tillers or walk-behind tractors with accessories for irrigation, spraying and harvesting that can increase utility and annual operating hours. Technologies must be climate-smart, gender-neutral, and integrated with agronomic practices tailored to Nepal's diverse topography.

Encourage land consolidation and cooperative farming

-

Fragmented landholding restricts mechanization. Promoting land consolidation and collective farming models can enhance machinery utilization and reduce costs through shared ownership and access.

Improve terraces and slope stability

-

In hill and mountain regions, investing in terrace improvement and slope stabilization can make mechanization feasible while also preventing soil erosion.

Adopt climate-resilient irrigation and weed control techniques

-

Dry areas require moisture-conserving irrigation methods like drip and sprinkler systems, along with biodegradable plastic or straw mulching. In the Terai, conventional systems such as canal irrigation, tube wells, and surface pumps should be modernized and expanded.

Targeted input availability and support

-

To promote mechanized potato farming, the government must ensure timely access to key inputs like quality seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Moreover, financial support through subsidies, tax incentives, soft credit, insurance, and extension services should be extended to farmers and cooperatives to encourage machinery adoption.

Development of community post-harvest centers and custom hiring aervices

-

The government should develop clear guidelines and enact a dedicated farm machinery law to regulate hire rates and operational standards for CHCs. Additionally, upgrading existing centers requires proper machine selection, transparent management, and trained operators. Decentralized, community or cooperative-based rental services can enhance smallholder access to costly equipment like potato planters and harvesters. Moreover, custom hiring models must be region-specific, with crop-based machinery packages tailored separately for hill and Terai areas.

Long-term strategies

Whole process mechanization package/integrated mechanized systems

-

Promote complete mechanization packages covering land preparation to post-harvest operations for potato farming. Coordinated use of implements such as seed bed formers, planters, weeders and harvesters ensures effective mechanization and supports the development of successful corporate farming models.

Post-harvest management to enhance mechanized potato supply chains

-

Strengthen the post-harvest segment to ensure quality preservation and reduce losses. Key interventions include: a) Enhancing farmers' capacity in harvesting, handling, grading, storage, cleaning, and the use of transport equipment; b) Improving packaging methods to maintain quality and marketability; c) Developing affordable, province-level cold storage facilities in both urban and rural markets to extend shelf life and improve farmers' bargaining power; d) Promoting multi-chamber cold storage systems in major market centers to minimize marketing losses.

Policy refinement and implementation

-

Review, refine, and update core agricultural machinery policies such as the Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Policy 2014, the Land Use Policy for Agriculture, and the Agri-Mech-Subsidy Working Modality 2016 to align with the federal governance structure. Develop clear, long-term policies that incentivize investment and scale up mechanization through subsidies, tax incentives, improved credit access, and training programs.

Machinery quality, safety, and standards

-

a) Empower NARC with a clear legal framework, enhanced testing facilities, and skilled personnel to formulate machinery standards and safety protocols; b) Enforce regulations to promote quality and safe machinery use; c) Subsidize and promote only government-certified machines; d) Prioritize research on human factors such as operator safety, comfort, and emissions; e) Strengthen the capacity of agricultural colleges and training centers to deliver education in modern mechanization.

Market linkages and value addition

-

Bridge the gap between mechanized farming and the supply chain by connecting farmers to processors and retailers, thereby boosting market access. Invest in local potato processing facilities to reduce imports and increase farmer incomes through value-added products like chips, fries, snack foods, and flour. Support R&D for processing-friendly potato varieties and make appropriate technologies accessible to smallholders to integrate them into the agro-industrial sector, fostering rural transformation.

Community engagement

-

Engage local communities to ensure mechanization initiatives are inclusive and relevant to local needs. Incorporating the perspectives of key stakeholders, especially regarding gender equity and social inclusion into technology design and promotion enhances adoption rates and ensures that equipment is useful to all, particularly women.

System improvement and technology integration

-

Focus on developing and distributing high-quality, early-generation seed potatoes to increase yields and reduce disease risk. Prioritize research on nutrient-rich, disease-resistant, and high-yielding varieties using advanced techniques such as hydroponics, aeroponics, and protected high-tech structures for Pre-Basic Seed (PBS) production. Ensure that adoption strategies are tailored to local economic capacities and infrastructure realities.

Support for local machinery manufacturing and service hubs

-

Encourage small-scale machinery manufacturing by revitalizing local artisans through modern tools and access to microfinance. Offer tax incentives and grants to reduce import dependence and support the production of tools suited to Nepal's diverse terrains. Promote collaboration with international firms for technology transfer, and establish service hubs and spare parts distribution networks in key potato-growing areas to ensure sustainability and reduce equipment downtime.

Infrastructure development

-

Enhance rural infrastructure such as farm roads, storage, processing facilities, irrigation systems, electrification, and communication networks to support mechanization and commercialization. Strengthen logistics and cold chain systems to connect hill farmers to wider value chains. Promote export-oriented branding and certification of surplus products targeting regional markets like India and Bangladesh.

Awareness and information campaigns

-

Strengthen extension networks to effectively disseminate validated mechanization practices through field demonstrations, workshops, exhibitions, and events at village, district, provincial, and national levels (e.g., Krishi Melas). Digitize custom hiring information (machine availability, rental rates, and services) using mobile apps, local media, and social platforms to increase accessibility for farmers.

Climate-smart and sustainable mechanization

-

Integrate mechanization with sustainable agricultural practices, including integrated pest, water, and fertilizer management, reduced tillage, and conservation agriculture. These approaches help ensure long-term productivity while minimizing environmental degradation.

Farmer cooperative models for equipment ownership

-

Promote cooperative models for the shared ownership and management of machinery. Establish machinery banks through farmer cooperatives to reduce individual investment burdens, improve access for smallholders, and support routine maintenance.

Skill development, training and capacity building

-

Provide comprehensive training on the operation, maintenance, and repair of mechanized equipment through partnerships with private sectors, cooperatives, and NGOs. Implement community-based Farmer Field Schools for practical training, e.g., calibration and safe use of sprayers. Develop specialized training programs for local technicians to support machinery upkeep.

Research and development

-

Collaborate with engineering universities and research institutes to develop terrain-specific mechanized equipment suitable for Nepal's hilly landscapes. Invest in innovation focused on automation, robotics, and precision agriculture technologies, including GPS, remote sensing, automated irrigation, drones, AI, IoT, and ICT, to modernize and optimize potato farming practices.

Recommended future farming scale system for mechanized production system in Nepal

-

Land fragmentation and small holdings hinder potato mechanization in Nepal. Sustainable farming requires minimum land scales tailored to topography, crop type, and infrastructure. Table 4 presents the recommended land scales matched to different farming systems along with feasible future mechanization strategies.

Table 4. Recommended land scales matched to different farming systems along with feasible future mechanization strategies.

Region Suggested land scale for farm Suitable farming systems Farming nature Appropriate mechanization Future strategy Mountain (high hills and Himalayas) # < 1 ha clustered smallholders

# Small-scale/

cooperative farmingOrganic crops, medicinal herbs, goat/yaks # Common in hill and mountain regions

# Fragmented terrain and limited arable land# Precision tools, solar dryers, drones, and terrain-smart tech

# Mini tillers, hand planters, compact harvesters

# Promotion of two-wheel tillage tractors

# Cooperative equipment sharing# Encourage group farming machinery rings for cost-sharing.

# Consolidate land cooperatives via agreements.Hill # 0.5–2 ha medium farms with terracing and pooling

# Small to medium scaleSemi-mechanized farming: vegetables, fruits, agroforestry, livestock Found in peri-urban and mid-hill regions # Mini tillers, small harvesters, power weeders, and cooperative hiring centers

# 15-35 HP tractors, small sprayers and semi-automatic planters

# Ridge formers, diggers, and basic graders# Promote custom hiring for mid-sized machinery.

# Expand extension services to promote machinery use.

# Expand small machinery use.Terai # 1–5 ha or more large farms

# Medium to large scaleCommercial mechanized farming of cereals and cash crops # Typically Terai or commercial enterprises

# Flat terrain, fertile soil, good infrastructureFull-scale mechanization: planters, irrigation, sprayers, harvesters, and automated grading/packaging # Develop mechanized farm clusters or agri-business zones.

# Promote PPPs to invest in infrastructure and value chains.

# Consolidate small plots via cooperatives or land leasing. -

Nepal's potato sector holds significant potential to enhance food security and improve rural livelihoods. Although widely cultivated, it remains heavily labor-intensive and under-mechanized, particularly in hilly and highland regions. Even as production steadily increases, Nepal continues to import large quantities of potatoes, underscoring inefficiencies and structural gaps in the domestic value chain.

While basic mechanization tools such as tractors, power tillers, planters, and diggers have gained traction in the Terai, many critical operations like seed cutting, weeding, harvesting, and post-harvest handling remain largely manual nationwide. Mechanization efforts are constrained by multiple structural barriers including fragmented landholdings, challenging terrain, limited research and development, weak policy frameworks, and inadequate infrastructure. Additional challenges such as poor-quality locally available machinery, conflicting tariffs and subsidies, insufficient operator training, and socio-demographic barriers, further hinder inclusive mechanization. Emerging technologies like protected cultivation and seed innovations offer considerable promise for boosting productivity and resilience. However, broader adoption requires context-specific adaptation, sustained investment, and strong institutional coordination.

Nevertheless, successful local initiatives have demonstrated the transformative potential of context-appropriate machinery, cooperative farming models, and targeted PPPs. Unlocking the sector's full potential will require a holistic and inclusive approach. Key priorities include investing in locally adapted equipment, strengthening repair and fabrication ecosystems, expanding cold storage and processing infrastructure, and advancing climate-resilient technologies. Equally important are policy alignment, inclusive training programs, and the integration of digital tools, including AI, IoT, and ICT, to drive equitable, sustainable, and resilient mechanization across Nepal's diverse agroecological zones.

This work was supported by grants from the Government of Nepal. The authors sincerely acknowledge the critical and constructive feedback provided by the anonymous reviewers, which greatly improved this manuscript.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conceptualization, design, literature review, and manuscript writing and editing: Khatri S; manuscript guidance and supervision: Shrestha S. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Imports of potatoes, Fiscal Year 2020/21[3].

- Supplementary Fig. S1 (a) Manual weeding. (b) Manual ridging.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 (a) Power sprayer. (b) Knapsack sprayer.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 (a) Mini tiller operated water pump. (b) Comb type bed structure. (c) Straight and long beds.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 NAERC developed manual potato grader.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 (a) and (b) Hi-tech structures.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Khatri S, Shrestha S. 2025. An overview on agricultural engineering technologies for potato farming in Nepal. Technology in Agronomy 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0010

An overview on agricultural engineering technologies for potato farming in Nepal

- Received: 17 February 2025

- Revised: 15 May 2025

- Accepted: 16 June 2025

- Published online: 29 October 2025

Abstract: Potato is a major food and cash crop in Nepal, with strong potential to enhance food security, livelihoods, and economic growth. However, its labor-intensive nature, rising production costs, and persistent labor shortages highlight the urgent need for agricultural engineering interventions. This paper presents an overview of agricultural engineering technologies for potato production in Nepal, focusing on the current production landscape, available technologies, major constraints, and strategies for promoting sustainable mechanization. Over the past decade, Nepal has made notable progress in agricultural mechanization, particularly in tillage, irrigation, and spraying, through the adoption of powered pumps, sprayers, tractors, and mini-tillers. Despite these advances, key potato farming tasks like planting, weeding, pest control, harvesting, and post-harvest handling remain mostly manual. Although some mechanized planting and harvesting have been introduced in the Terai region, using tractor-mounted equipment, the overall adoption of specialized potato machinery remains minimal. The limited uptake of mechanization is attributed to factors including difficult terrain, small landholdings, low investment capacity, limited repair services, traditional practices, and a lack of gender-sensitive and agroecology-specific tools. To address these barriers, future efforts should prioritize the development and deployment of lightweight, hill-compatible tools, and agroecology-based machinery. Promising options include row and picker wheel-type potato planters, seedbed formers, ridgers, inter-row cultivators, fertilizer spreaders, power weeders and sprayers, micro-irrigation systems (drip and sprinkler), low-cost diggers, and efficient post-harvest technologies for grading and processing. Moreover, the adoption and integration of smart farming technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), and controlled environment systems (e.g., hydroponics/aeroponics) in potato farming are recommended as key future research directions in Nepal.

-

Key words:

- Agricultural engineering /

- Holistic process /

- Nepal /

- Potato /

- Technologies /

- Constraints /

- Path ahead