-

Plant epidermal wax is a hydrophobic barrier that covers the plant surface, which plays a crucial role in plant growth, development, and stress responses to environmental challenges. It can effectively prevent non-stomatal water loss and maintain water balance, enhancing its resistance to drought. It can also resist the invasion of pathogens and pests by providing physical barriers and antibacterial components, thereby reducing the incidence of diseases. Additionally, it can reduce ultraviolet damage and maintain surface cleanliness and water resistance. Furthermore, it can affect the storage quality of fruits, extending their shelf life[1].

Wax synthesis occurs in four main stages, with the core processes taking place in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[1]. De novo fatty acid synthesis begins in the chloroplast stroma using acetyl-CoA as the starting material. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) then catalyzes the conversion of acetyl-CoA into malonyl-CoA, which undergoes sequential reactions via the fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex to synthesize the saturated fatty acids C16:0 and C18:0. These short-chain fatty acids are then activated into acyl-CoA by long-chain acyl-CoA synthase (LACS). C16/C18 acyl-CoA then enters the endoplasmic reticulum, where fatty acids can elongase complex (FAE) undergoes a four-cycle reaction to generate C20–C34 VLCFA-CoA. This complex comprises four key enzymes: the rate-limiting KCS enzymes, the KCR enzyme, the HCD enzyme, and the ECR enzyme. Subsequently, the wax component undergoes modification. VLCFAs-CoA generates derivatives via two pathways: In the decarboxylation pathway, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase produces aldehydes, which are then converted into alkanes by the CER1-CER3 complex. Arabidopsis cer1 mutants produce almost no alkanes, which can be converted into secondary alcohols and ketones. In the acyl reduction pathway, FAR catalyses the formation of primary long-chain alcohols. While WSD catalyzes the formation of wax esters, overexpression of WSD1 in Arabidopsis increases wax ester production threefold[2]. The flux of both pathways determines the proportion of wax components. The final wax products are transported to the epidermal surface.

The composition and regulation of plant cuticular wax are remarkably conserved across species and are centred on consistent metabolic foundations, key gene functions, and patterns of organ distribution. All plants utilize VLCFAs and their derivatives as the main constituents of wax, which primarily comprise alkanes, primary alcohols, fatty acids, and aldehydes. Certain species also synthesize wax esters or triterpenoid compounds (Tables 1−6). Wax components in wheat, rice, maize, apple, and citrus are similar. Alkanes predominantly range from C27 to C31, while primary alcohols are concentrated in the C28−C30 range. The core gene families that regulate wax biosynthesis also exhibit functional conservation, with their encoded key enzymes possessing functional orthologues across multiple species. KCSs mediate VLCFAs chain elongation, CER1 catalyses aldehyde decarboxylation to form alkanes[3,4], FARs participate in primary alcohol synthesis[5,6], and WSD1 mediates wax ester formation[2]. These genes perform consistent functions across wheat, rice, apple, and citrus. Furthermore, wax composition exhibits marked species specificity, which is an evolutionary outcome of plant adaptation to ecological niches and life cycles. For example, wheat stem wax contains unique β-diketones and their derivatives, which enhance plant drought tolerance, while maize leaf wax harbours distinctive alkyl hydroxycinnamate esters (AHCs), these components remain undetected in other species[7,8]. In apples and pears, fruits accumulate substantial liquid wax esters that impart surface greasiness, while citrus and tomato peel enrich triterpenoid compounds that are involved in water retention and extensibility regulation[9−11]. These specific compounds are not by-products of metabolism, but vital to the survival, reproduction, and adaptation of plants to their environment.

Plant cuticle is a key protective barrier for aerial organs, which are highly plastic and dynamically regulated by various endogenous and exogenous factors, among which plant hormones act as core endogenous regulators to modulate wax biosynthesis, composition, and deposition. Different hormones exhibit functionally differentiated regulation of wax, adapting to the requirements of different plants in various scenarios. This differentiation reflects both evolutionary conservation and species-specificity. For instance, ABA prioritizes enhancing wax hydrophobicity under drought and salinity stress by activating the VLCFAs pathway to prolong alkane synthesis. Ethylene (ETH) dynamically adjusts wax production during fruit ripening. It promotes alkane synthesis during the early stages of wax maturation and then accelerates wax ester degradation in the later stages[12]. GAs and BR focus on balancing growth and stress, maintaining cuticle thickness via the regulation of DELLA or BZR1 to accommodate organ elongation[13−15]. This functional differentiation ensures plant adaptability during vegetative growth, reproductive development, and environmental stress, and provides targets for agricultural production.

Table 1. Analysis of wax components and regulatory genes in tomato.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. Alkanes: C25–C33 (odd carbons) C29, C31 SlCER1/3, SlCER6, SlKCS8/SlKCS10, SIFIS1, SlCER1-1 [16−21] Primary alcohols: C22–C30 C26, C28, C30 SlFARs, SlLACS1, SlABCG11, SlWRKY33, SlbHLH51 [22−24] Fatty acids: C16–C30 C16:0, C18:0, C20:0 SlLACS1, SlFIS1, SlKCS1 [20−22,25] Triterpenoids α-Amyrin, β-amyrin, lupeol, taraxerol SlTTS1, SlMYB75, SIFIS1 [21,26,27] Other components Sugar esters (glucose esters, sucrose esters) − [16] Table 2. Analysis of wax components and regulatory genes in apple.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. Alkanes: C25–C33 (odd carbons) C29, C31 MdCER1, MdCER3, MdHDG5, MdERF2, MdSHN1 [28−32] Primary alcohols: C22–C30 (even carbons) C28, C30 MdMYB96, MdFAR1/MdFAR4 [33] Fatty acids: C16–C26 C16:0, C18:0 MdLACS2/MdLACS4, MdKCS1/MdKCS10, MdWRI4 [28,34] Triterpenoids Oleanolic acid. Ursolic acid, betulinic acid MdOSC1/MdOSC3/MdOSC4, MdCYP716A175, MdMYB16 [33,35,36] Wax esters (C22–C44) C32, C34, farnesyl linoleate MdLACS1, MdSHN2, MdWSD1, MdLACS2, MdNAC29, MdERF72 [33,37,38] Aldehydes: C28–C30 C30 MdCER1, MdDEWAX [28,39] Ketones C29 − − Table 3. Analysis of wax components, functions, and regulatory genes in citrus.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. Alkanes: C23–C34 (odd carbons) C27, C29, C31 CsCER1, CitKCS1/CitKCS12, CitWRKY28, CitKCS1/CitKCS12, CsMYB44, CsMYB96 [5,40,41] Primary alcohols: C22–C32 (even carbons) C22,C24,C30 CsKCS2/CsKCS20, CsCER4/FAR3, CsERF003, CsMYB102 [5,42] Fatty acids: C12–C28 C16, C18, C24, C26 CsKCS20, CitKCS1, CsKCS2/CsKCS3, CsLACS1, CsMYB7, CitNAC029 [40−42] Triterpenoids Lanosterol, lupenol, α-amyrin,

β-amyrin, corbigenCsMYB96, CsOSC1, CsCYP716A175, CsERF003, CsMYB30, CsSQS [42−44] Aldehydes: C24–C28 C26, C28 CsCER3, CsMYB102, CsCER3, MdNAC29, MdERF72 [13, 41,42] Table 4. Analysis of wax components, functions, and regulatory genes in maize.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. Alcohols: C16–C32 (even carbons) C32, C30 ZmCER4, ZmKCS12 [45−47] Aldehydes: C24–C32 (even carbons) C32, C30 ZmEREB46, ZmGL15, ZmCER2 [48,49] Alkanes: C23–C32 (odd carbons) C29, C31 ZmCER1, ZmFDL1 [50,51] Wax esters: C32–C44 (even carbons) C36, C38 ZmWSD11, ZmGL8 [45,52] Fatty acids: C20–C34 (even carbons) C24:0, C26:0, C28:0 ZmKCS3/ZmKCS19, ZmGPAT5 [47,50,53] Sterols: C27–C29 β-sitosterol (C29:1), campesterol (C28:1), stigmasterol (C29:2) ZmSMT1, ZmCYP51 [6,45,54] Alkyl hydroxycinnamates (AHCs): C16–C32

(even carbons)Alkyl coumarates (C20/C22), alkyl ferulates (C22/C24) ZmFHT, ZmFAR1/4/5 [45,55,56] ω-Hydroxy fatty acids (ω-OHFAs): C18–C32

(even carbons)18-hydroxyoleic acid (C18:1), C24/C26 ω-OHFAs ZmGPAT5, ZmCYP86A [45,50,53] Alkenes: C25–C33 (odd carbons) C29:1 alkene, C31:1 alkene ZmFAD2, ZmKCS20 [46,51] Table 5. Analysis of wax components, functions, and regulatory genes in rice.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. Primary alcohols: C22–C34 C28, C30 OSWSL5, OsPLS4, OsWSL4, OsGL1 [57−61] Fatty acids: C16–C34 C26, C28, C30 OsWSL4, OsABCG9, OsPLS4, OsWR1 [58,60−62] Alkanes: C23–C33 C27, C29, C31 OSWSL5, OsABCG9, OsPLS4, OsCER2 [60,62−64] Aldehydes: C28–C34 C30 and C32 OsABCG9, OsWSL2,OsWSL4 [57,61,62] Table 6. Analysis of wax components, functions, and regulatory genes in wheat.

Wax component Core components Regulatory genes Ref. β-diketones and their derivatives β-diketones, hydroxy-β-diketones TaW1, IW1, W3/W5 [65] Primary alcohols: C22–C35 C20, C22, C24, C26, C28 (general);

C31, C35 (leaf epidermis)TaFAR5 [7] n-Alkanes: C25–C35 C33 TaCER1-1A, TaCER1-6A, TaMYB96-2D/5D, TaWSD1, TaMYB60 [4,66,67] Wax esters (WE): C19–C50 C44 TaMIXTA-like, TaKCS6, TaFAR [68] Glycerides diacylglycerol (DG): C27–53, monoacylglycerol (MG): C31–C35, triacylglycerol (TG): C29–C73 DG: C47, C45. MG: C35, C31. TG: C48 TaGPAT, TaALDH7A1, TaALDH, TaDPP1, E2.3.1.158 [67] (O-Acyl)-1-hydroxy fatty acids (OAHFA): C31–C52 C48 TaACOT1-2-4, TaCYP704B1/CYP86 [67] Fatty acids: C16–C24 C16:0, C18:0, C18:1 TaMYB30, TaKCS [69] Aldehydes: C28–C32 C28, C30, C32 TaCER1, TaALDH [65,67] Other minor components: Ceramides (Cer), cholesterols (ChE), cardiolipins (CL) Cer: C29–C48, ChE: C46, CL: C65 − [67] -

ABA is the core stress-resistance hormone that enables plants to cope with abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and UV-B radiation. Its classical functions include inducing stomatal closure and activating stress-resistance genes to reduce water loss and oxidative damage[69]. Wax is a key barrier against non-stomatal water loss. ABA compensates for the limitations of stomatal closure by regulating wax synthesis, while wax maintains ABA homeostasis via feedback to alleviate stress signals, forming together a dual barrier for plant stress resistance[70,71].

The regulation of wax by ABA depends on dynamic responses to stress signals. Abiotic stresses such as drought can promote ABA synthesis by upregulating the expression of NCED genes AtNCED3 and TaNCED, which are rate-limiting enzymes in the synthesis of ABA[72]. ABA binds to cytoplasmic PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors, inducing conformational changes in the receptors and inhibiting PP2C phosphatases ABI1/ABI2[73]. This releases their suppression of the SnRK2.6/OST1 kinase[74]. Activated SnRK2 initiates the wax synthesis pathway by phosphorylating downstream TFs. R2R3-MYB family AtMYB96 can activate CER1 and CER3, and KCS2/6 to promote the synthesis of alkanes, as well as the elongation of very VLCFAs[75,76]. TaMYB96-2D/5D bind to the CAACCA motif of TaCER1-6A to promote C27−C33 alkanes[77].

The regulation of wax by ABA fundamentally involves optimizing physical barriers to match stress intensity. During mild drought, ABA prioritizes stomatal closure while maintaining wax thickness. During moderate to severe drought, ABA significantly enhances wax synthesis[78]. This network exhibits distinct functional specialization across plant species, with an ABA-MYB96-CER1 core pathway in Arabidopsis protecting leaf water retention, while in wheat, TaMYB96-TaCER1-6A regulates long-chain alkanes and enhances drought tolerance without reducing yield[76,77,79,80]. In watermelon, ABA and melatonin synergistically promote the synthesis of C29 and C31 alkanes, optimize the cuticle structure, and significantly reduce the rate of non-stomatal water loss[81]. Fruit crops focus on maintaining post-harvest quality. In sweet cherry, ABA treatment increases the expression of PaWSD1 and PaCER1, thickening the wax and cuticle layers and reducing fruit cracking by 40%[82]. In citrus fruits, ABA treatment can promote terpene accumulation but inhibit alcohol and fatty acid synthesis at low humidity, whereas the opposite was observed at high humidity[40, 83]. This dynamic regulation may be related to water retention and stabilization of epidermal structure during fruit ripening.

Normally, a drought tolerance gene is always ABA sensitive. While in apple, wax-related genes such as MdKCS2, MdDREB2A, are insensitive to ABA but enhance drought tolerance in plants, indicating that wax-mediated drought resistance is partially achieved through regulating non-stomatal water loss[84−86].

-

ETH is a hormone that regulates multiple aspects of plant development, including plant senescence and fruit ripening, as well as responses to biotic stresses[87]. Its core functions include promoting fruit softening, inducing abscission, and activating defence genes. Furthermore, wax plays a key role in determining the quality of fruit after harvest, with its content and structure directly influencing desiccation rates, susceptibility to pathogen infection, and the development of quality defects such as greasiness[88]. During the fruit ripening process, ETH can activate phosphatase and other enzymes related to fruit ripening, effectively promoting fruit ripening and changing the color, taste, and other quality characteristics of fruits[89,90]. Furthermore, the ETH receptor antagonist 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) competitively binds to ETH receptors, thereby blocking the effects of ETH on wax regulation to form an ETH-1-MCP antagonistic system. 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP), an ETH receptor inhibitor, can significantly regulate fruit cuticular wax metabolism by blocking the ethylene signaling pathway, thereby delaying fruit senescence and maintaining postharvest quality. It is widely used in the storage and preservation of fruits and vegetables, as it effectively retards postharvest senescence of fruits and notably improves storage quality. Specifically, 1-MCP reduces ETH-induced changes in wax components by inhibiting gene expression, with the core effects being a decrease in liquid wax content, maintenance of alkane proportions, and reduction of greasiness-related components.

ETH generally promotes the accumulation of total cuticular wax, primarily enhances the accumulation of very long-chain alkanes and aldehydes, and inhibits fatty acids and esters. Ethephon treatment increases the density and size of platelet-like cuticular wax crystals on lemon fruit peel, with the crystals extensively covering stomata[91]. In apple, the overexpression of the ETH-responsive factor MdERF2 upregulates key wax biosynthesis genes MdLACS2, MdCER6, and MdCER4, promoting the synthesis of primary alcohols and wax esters. This regulation induces tubular wax accumulation with surface folds and also accelerates apple wax melting to form a continuous wax coating[92].

1-MCP is an ETH receptor inhibitor, which can significantly affect fruit wax metabolism by blocking the ETH signaling pathway, thereby delaying fruit senescence and maintaining postharvest quality. Owing to these regulatory effects, 1-MCP is widely used in the storage and preservation of fruits and vegetables, which can effectively delay the post-harvest senescence of fruits and significantly improve the storage quality[93,94]. In apple, 1-MCP inhibits ethylene production and fruit softening by down-regulating the expression of genes MdKASs, MdCACs, and MdDCR1, it reduces the synthesis of short-chain alcohol linoleate esters and effectively inhibits the greasiness caused by the wax phase transition[95]. In pear, it inhibits the accumulation of fluid n-9 olefins such as C17 and C19, delays the increase in wax fluidity, and maintains the fruit firmness and the content of antioxidant substances. 1-MCP treatment can up-regulate the expression of genes such as PpCER1 and PpKCSs, promote the deposition of alkanes and fatty acids, delay wax degradation, and inhibit the increase in the fruit weight loss rate and decay rate[96−98]. In peach, 1-MCP upregulates PpaCER1 and PpaKCSs. This maintains the lamellar structure and high wax crystal content, reduces water loss and inhibits microbial invasion, thereby lowering rates of fruit weight loss and rot. Additionally, it maintains fruit firmness and ascorbic acid content, thereby improving post-harvest quality during cold storage[99]. In tomato, 1-MCP treatment can significantly delay the water loss of fruits and inhibit ETH production, alter the composition of epidermal wax and cutin, upregulate the expression of genes such as SlCER2-like1 and SlCER3, increase the content of alkanes and alcohols, and reduce the content of triterpenoids, thus decreasing the water loss rate of fruits[17]. In jujube, 1-MCP treatment or in combination with heat shock (HT) can increase the wax content, reduce epidermal microcracks, and extend the shelf life by upregulating the expression of genes such as FATB and FAB2[100].

1-MCP enhances the water retention capacity of fruits by regulating the structure and composition of the epidermis, and plays an important role in reducing postharvest water loss of fruits. However, whether 1-MCP regulates the cuticular wax metabolism through other pathways and its action mechanism in more types of fruits still needs further exploration and research to expand its application in the field of fruit preservation.

-

SA plays an active role in the plant defense system, deeply participating in the immune response and inducing plants to produce resistance against pathogens, thus enhancing the immunity of plants. In terms of its connection with cuticular wax, SA can affect the carbon chain length of cuticular wax by regulating the activity of β-oxidase, thereby influencing the structure and function of cuticular wax[101].

At the molecular level, SA binds to the cytosolic receptor NPR1, inducing the dissociation of NPR1 from dimers to monomers, which enter the nucleus to relieve inhibition of TFs[102]. Among these, the R2R3-MYB transcription factor CsMYB96 acts as a core hub. In citrus, CsMYB96 not only directly binds to the promoter of CsCBP60g to activate the SA synthesis pathway gene ICS1 but also targets and regulates key wax synthesis genes KCS6, CER1, and CER3 to promote VLCFAs elongation and alkane production, increasing C29/C31 alkanes content by 40%–50% and wax layer thickness in fruit wax[103]. In Arabidopsis, overexpression of WRKY70 showed significantly upregulated CER1 expression, with leaf alkane content increased by 25%–30%[104].

The cuticle formed by wax, as a physical barrier, influences the accumulation and signal transduction of SA. Mutants in wax synthesis-related genes gl1, gl3, and ttg1 lead to cuticle defects, thereby affecting systemic acquired resistance (SAR) that relies on SA accumulation, suggesting that wax defects may interfere with SA accumulation or signal perception in distal tissues[105]. Wax-deficient mutants acp4 and mod1 exhibit increased cuticle permeability, promoting preferential partitioning of SA into wax via transpirational pull rather than the apoplast. This results in insufficient SA accumulation in distal tissues and impedes synthesis of the SAR-inducing factor pipecolic acid, thereby compromising defense responses. High humidity can restore SA transport in wax-deficient mutants by reducing transpiration, reestablishing SAR competence. In SA-deficient sid2 mutants, enhanced stomatal aperture and reduced water potential are rescued by exogenous SA treatment, highlighting the role of SA in regulating stomatal behavior to compensate for wax defects. Under abiotic stress, SA optimizes wax components to balance hydrophobic water retention and epidermal extensibility. In the low-wax Brassica napus cultivar ZS9, SA treatment increases C30 aldehyde content and reduces secondary alcohol content in leaf wax, decreasing cuticle permeability and water loss rate compared to the control. While in the high-wax cultivar YY19, only the C29 secondary alcohol content is fine-tuned to avoid increased wax brittleness[106]. In tomato, under salt stress, SA induces the accumulation of C29 alkanes and C30 alcohols, reducing epidermal Na+ uptake and alleviating epidermal cracking via wax thickening[107]. Collectively, these findings reveal a synergistic defense network integrating wax barrier function, SA signaling, and humidity-mediated regulation.

Wax and SA exhibit synergistic effects in SAR, where wax ensures signal perception and SA mediates signal transduction, and they share regulatory pathways of genes like GL1. The cuticle, composed of wax, serves as a physical barrier, and its synthesis defects, such as gl1, gl3, and ttg1 mutants, increase plant susceptibility to pathogens and affect the accumulation of SA in distal tissues and the perception of systemic acquired resistance SAR signals[103,108].

-

JA and its derivatives are an important class of endogenous plant hormones. Their biosynthesis starts from linolenic acid and is finally generated through a series of enzymatic reactions involving lipoxygenase and other enzymes[109]. JA is not only an important signaling molecule for plants to resist mechanical damage, insect feeding, and pathogen infection[110]. It can induce the expression of insect-resistant related genes, synthesize defensive secondary metabolites, and enhance plant resistance, ensuring the survival of plants when they are attacked by external factors. The metabolic pathways of hormones and cuticular wax exhibit multi-dimensional commonalities in plant physiological regulation. Both processes rely on fatty acids as core substrates: wax synthesis depends on the elongation of VLCFAs, while JA depends on key enzymes like acyl-CoA synthetase (LACS)[111].

Cuticular wax serves as a physical barrier to reduce water loss and pathogen invasion, while JA acts as a signaling molecule to induce defense gene expression. In maize, ZmGL8 encodes the 3-ketoacyl reductase of the VLCFAs elongase complex; its normal expression diverts acyl-CoA to wax synthesis, generating components such as C29/C31 alkanes, leading to an insufficient supply of the JA precursor linolenic acid and maintaining low JA levels. gl8 mutants impair VLCFAs elongation, reducing total wax content with significant reduction in C29 alkanes and diverting excess precursors to the JA synthesis pathway[112]. In Arabidopsis, JA-activated WRKY70 preferentially binds to the promoter of the JA defense gene AtPR1 rather than AtCER1, further diverting resources to JA[104]. In synergistic regulation, citrus ERF transcription factor CsESE3 binds to the GCC-box element in the promoter of the JA synthesis gene CsPLIP1 to activate its expression, while indirectly activating wax synthesis genes CsLACS1, CsCER1, and CsCER6. Overexpression of CsESE3 in tomato increases C29/C31 alkane content by 1.2–1.8-fold and thickens the wax layer, breaking the traditional metabolic trade-off and achieving dual enhancement of JA chemical defense and wax physical barrier[112].

As the core chemical defense hormone for plants to cope with biotic stress, JA shares a lipid metabolic pathway with cuticular wax. Their regulatory relationship is complex, involving both trade-off effects due to lipid precursor competition and synergistic effects mediated by TFs in specific scenarios[111,112].

-

GAs are the core growth hormone regulating plant developmental processes such as stem elongation, seed germination, and fruit enlargement[113]. It is involved in the regulation of plant sex differentiation to promote the formation of male flowers, and also plays a key role in delaying leaf senescence and regulating plant responses to abiotic stresses such as drought. GAs can affect fruit quality by regulating wax biosynthesis and deposition[114].

At low concentrations, GAs significantly increase the mass of cuticular wax, with the strongest response observed in young fruit and reduced sensitivity in mature fruit[114]. The tomato FIS1 gene encodes GA2-oxygenase, which is responsible for GAs inactivation. fis1 leads to the accumulation of active GAs, thereby upregulating the expression of wax synthesis genes such as CYP86A69 and CERs. This increases the content of alkanes and alcohols, thickening the cuticle[21]. In apples, exogenous GAs can thicken the cuticle by optimizing the C29/C31 alkane ratio, thereby reducing post-harvest water loss and the incidence of rust disease[115]. Furthermore, GAs-mediated regulation exhibits concentration thresholds; in tomato, its promoting effect ceases at excessively high concentrations[114]. In lemon, GAs can inhibit key wax biosynthesis genes and reduce the accumulation of alkanes and aldehydes. This consequently leads to abnormal wax morphology and impaired barrier function. While in apples, GAs act as a regulator that improves self-pollination quality, promoting the thickening of the wax layer and enhancing the epidermal hydrophobic barrier. This reduces water loss during storage and indirectly improves fruit marketability. This difference may stem from the distinct functional priorities of GAs in different crops[90, 115].

GAs can enhance fruit hardness and extend shelf life by thickening the cuticle. It also improves drought tolerance, disease resistance, and resistance to fruit cracking by strengthening barrier function[21, 115]. This relationship provides a crucial model for elucidating the synergistic regulatory mechanisms between plant hormones and epidermal structure and has significant application value in crop breeding and cultivation management.

-

BRs are pleiotropic hormones regulating plant growth and development, and stress resistance. By integrating signal pathways and lipid metabolic networks, BRs precisely regulate the synthesis, structure, and function of cuticular wax[116,117].

In rice, BRs activate wax synthesis genes such as OsKCS1 and OsCER2 via the binding of OsBZR1 to respond to BRs. This maintains the C28/C30 primary alcohol ratio in seed, safeguarding the water balance during germination, and BRs lower the incidence of rice blast disease during the seedling stage[118]. In maize, under heat-drought stress, exogenous BRs improve structural and quality properties. BRs activate the expression of ZmKCS6 and ZmCER3, which thickens the leaf wax layer by 18%–22% and increases the content of C29 and C31 alkanes, thereby enhancing epidermal hydrophobicity. This reduces non-transpiratory water loss and inhibits the attachment of piercing-sucking pests, such as aphids[119].

-

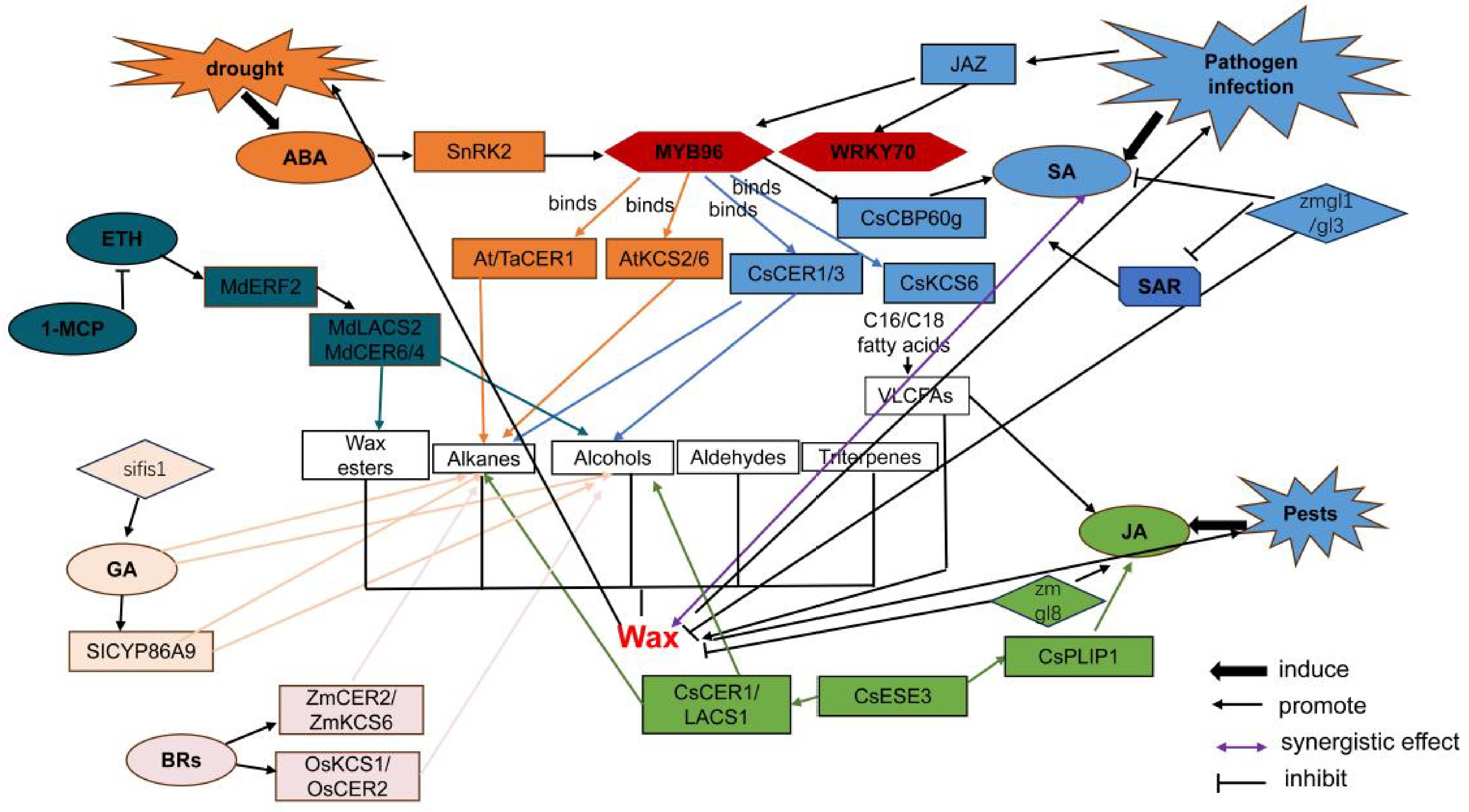

Stress-responsive hormones ABA and SA consistently promote alkane accumulation in species such as Arabidopsis, citrus, and wheat. ABA enhances the hydrophobic cuticular barrier primarily through the MYB96-CER1 regulatory module, thereby establishing a conserved mechanism for drought adaptation. In contrast, developmental hormones such as ETH and GAs predominantly modulate wax composition to improve fruit or organ quality. The MYB96 exhibits notable evolutionary conservation, with orthologs—including AtMYB96, CsMYB96, and TaMYB96 serving as central hubs in ABA/SA signaling pathways. These transcription factors directly activate wax biosynthetic genes such as CER1 and KCSs. Similarly, the CER1 family functions uniformly across species in catalyzing alkane formation, acting as key executors in hormone-mediated enhancement of cuticular hydrophobicity (Table 7). These findings further corroborate the conserved roles of core wax biosynthesis genes as established in the literature (Fig. 1).

Table 7. Hormonal responses and primary wax changes in various species.

Species Hormone response Major wax changes Key regulatory genes Arabidopsis thaliana ABA, SA, JA C29 alkane↑, drought tolerance↑ AtMYB96, AtCER1, AtWRKY70 Tomato ETH, GA, ABA Alkanes↑, wax ester dynamic changes SlCER1, SlFIS1, SlKCS Apple ETH, GA, ABA Primary alcohols↑, wax ester↑, optimised hydrocarbon ratio MdERF2, MdKCS2, MdMYB96 Citrus ABA, SA, ETH C29/C31 alkanes↑, triterpenes respond to humidity[75,77–79] CsMYB96, CsCER1, CitKCS Maize JA, BRs, ABA C29 alkane↑, JA-wax balance ZmGL8, ZmKCS6, ZmCER3 Rice BRs, ABA C28/C30 primary alcohol ratio remains stable OsBZR1, OsCER2, OsWSL Wheat ABA C27–C33 alkanes↑, enhanced drought tolerance TaMYB96, TaCER1-6A

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the molecular regulatory network involved in plant wax biosynthesis, hormone signaling, and systemic acquired resistance.

ABA drives wax synthesis by regulating MYB family TFs. In Arabidopsis, AtMYB96 directly binds to the promoters of wax synthesis genes, such as AtKCS6 and AtCER3[80,120]. This promotes the elongation of VLCFAs and the accumulation of alkanes, enhancing drought resistance. Although the function of CsMYB96 in citrus is primarily reported to be the regulation of SA synthesis, the conserved function of its homologues suggests potential involvement in ABA-mediated wax regulation. MYB96 may serve as the pivotal node in the cross-regulatory network that governs wax production. In maize wax-deficient mutants gl8, total wax content and ABA levels are negatively correlated under drought stress, which further demonstrates that ABA influences wax synthesis through resource allocation. There is a trade-off between JA and wax synthesis based on competition for the same precursors, VLCFAs. The ZmGL8 mutation in maize reduces total wax content by 42% while simultaneously upregulating phospholipase and desaturase genes. This promotes the release of the JA precursor C18:3 from the chloroplast membrane, thereby increasing JA levels by two to threefold[52,103,112,121]. Conversely, the citrus ERF transcription factor CsESE3 disrupts this trade-off by activating CsLACS1 and CsCER1-3 simultaneously to enhance wax accumulation, while also promoting JA synthesis via CsPLIP1. In Arabidopsis, wax mutants cer1 and kcs1 exhibit enhanced insect resistance dependent on SA rather than JA, demonstrating species specificity[111,112]. SA regulates wax via a cross-network of TFs. After SA treatment, it activates pathogenesis-related (PR) genes to enhance disease resistance, while binding to the W-box of KCS6 and CER3 promotes C29 alkane. In citrus, CsMYB96 promotes SA synthesis by activating CsCBP60g, which may suggest that wax is indirectly regulated via homologous function. Furthermore, the efficiency of the SA transport system decreases by 40%–50% in mutants atcer1 and atcer3, establishing a bidirectional regulatory relationship between wax and SA[102,103].

Research into specific species remains fragmented. Although studies have been conducted on species such as Arabidopsis, maize, and citrus, the conservation and specificity of hormone-wax regulation in major crops such as wheat and maize have not been validated through large-scale cohort studies. This prevents the formulation of a universal theoretical framework. The mechanism of post-translational modification remains unexplored, with reports solely indicating that the Arabidopsis thaliana F-box protein SAGL1 negatively regulates wax synthesis by ubiquitinating and degrading CER3. However, no studies have yet investigated how hormones modulate the activity of wax synthase enzymes, such as KCSs and CERs.

Existing research has clearly defined the regulatory framework of the key hormones that govern wax synthesis, composition, and function. However, there are still limitations in this subject area, with incomplete coverage of the hormonal regulatory system. Besides ETH, 1-MCP, GAs, and JA, the regulation of wax by ABA has only been documented in Arabidopsis and wheat, with limited systematic studies in fruits and vegetables. The roles of other hormones, such as GAs and BRs, remain largely unexplored. The complex characteristics of hormonal interactions affecting wax production include synergistic, antagonistic, and spatiotemporal specificity, yet systematic elucidation remains insufficient.

Future research should focus on cross-hormone regulation, with the aim of achieving breakthroughs in elucidating mechanisms, technological innovation, and translational application. In fundamental mechanism research, efforts should focus on constructing multi-hormone signaling networks. Using TFs as entry points, techniques such as Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) and yeast two-hybrid assays should be employed to identify core hubs in the cross-regulation of ETH, JA, and GAs. This should include verifying whether ERF family members respond simultaneously to signals from all three hormones, and clarifying their binding specificity towards genes such as CERs and KCSs.

Research on hormone-regulated wax provides a new avenue for sustainable agriculture. Regulating endogenous hormone levels or key gene expression can breed wax-enhanced crop cultivars with improved drought resistance, disease resistance, and postharvest preservation; exogenous hormone treatment, such as ABA, BR spraying, can serve as a green pest control method to reduce chemical pesticide use. In the future, with the integration of synthetic biology and precision agriculture, the hormone-wax regulatory network may play a core role in crop stress-resistant breeding and fruit quality improvement. Studies should be expanded to elucidate the mechanisms by which ABA and 1-MCP synergistically regulate wax production in jujube to enhance crack resistance and to investigate the role of auxin in delaying wax greasiness in apple. Regarding cross-hormone application strategies, precise protocols should be established that combine species-specific wax targets with hormone combinations. For jujubes prone to cracking, use a combination of JA pre-treatment and post-harvest 1-MCP: JA induces wax precursor synthesis, while 1-MCP maintains wax structure, thereby enhancing epidermal mechanical strength synergistically. For apples prone to greasiness, develop a low-concentration ETH and JA inhibitor dynamic regulation technique: apply low-concentration ETH early in storage to promote solid alkane synthesis, followed by JA inhibitors later to inhibit liquid ester accumulation. For fruits and vegetables requiring colour maintenance, such as lemons, use the 1-MCP and low-dose ABA combination. This can antagonize GAs, inhibit wax synthesis while preventing the excessive suppression of the ripening process. In crop breeding, gene editing can be used to modify genes at hormone cross-regulation nodes. For example, editing maize ZmGL8 reduces leaf wax synthesis to activate JA-mediated insect resistance while preserving stem wax content to maintain drought tolerance. This achieves synergistic insect and drought resistance. Precise regulatory schemes can be designed in cultivation practices by exploiting hormone crosstalk signals. For example, applying low concentrations of SA and ABA in tomato seedlings enhances stress tolerance in plants while reducing the incidence of multi-chambered fruit deformities. Furthermore, multi-omics technologies such as metabolomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics should be integrated to decipher the spatiotemporal regulatory effects of cross-hormones and establish optimal hormone concentration ratios.

In conclusion, current research has established a basic hormone-wax regulatory framework, but gaps in crosstalk mechanisms, species specificity, and post-translational modifications remain. Future work addressing these gaps will enable the hormone-wax network to drive crop stress resistance and postharvest preservation.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (Grant Nos 2024CXGC010903, 2023CXPT013), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD2301000), the National Industry Technology System of apple (CARS-27), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32472705, 32072539, 32302513), Young Talent of Lifting engineering for Science and Technology in Shandong (Grant No. SDAST2024QTA083) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant Nos ZR2022JQ14, ZR2022QC112).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gao HN, Jiang H; draft manuscript and figure preparation: Gao HN, Liu HT, Li MR, Fang SJ, Qi RH, Ge SF; manuscript revision: Jiang H, Li YY, Ge SF. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gao HN, Liu HT, Li MR, Fang SJ, Qi RH, et al. 2025. The relationship between plant hormones and cuticular wax. Plant Hormones 1: e023 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0023

The relationship between plant hormones and cuticular wax

- Received: 21 July 2025

- Revised: 03 October 2025

- Accepted: 10 October 2025

- Published online: 30 October 2025

Abstract: Plant cuticular wax is a hydrophobic lipid complex composed of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and their derivatives. It serves as a physical barrier against drought and pathogens, and also modulates agronomic traits such as fruit glossiness and postharvest preservation. The biosynthesis of wax involves sequential stages, including de novo fatty acid synthesis and VLCFA elongation, relying on key genes such as β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCSs) and ECERIFERUM1(CER1). Abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), gibberellins (GA), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and brassinosteroids (BRs) can regulate cuticular wax through a network of metabolic association, transcriptional crosstalk, and signal interaction. Metabolically, JA competes with wax for this precursor C16/C18 acyl-CoA. Transcriptionally, target conserved transcription Factors (TFs) such as MYB96 and BZR1, at the signal level, intersect at nodes like DELLA proteins. Each hormone exhibits differentiated functions, such as ABA for stress resistance, and ETH for fruit development. While individual hormone pathways have been clarified, gaps remain in understanding multi-hormone crosstalk and field application stability. This work provides targets for crop improvement.

-

Key words:

- Hormones /

- Wax /

- Resistance /

- Quality