-

Lakes and reservoirs, as vital freshwater resources, are crucial for supporting biodiversity and providing drinking water, while also sustaining various economic activities. However, extensive evidence suggests that the ecological integrity and water quality of these systems are deteriorating worldwide, particularly due to intensifying anthropogenic pressures such as agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and climate-induced changes in hydrological cycles[1−3]. These stressors lead to nutrient enrichment and the accumulation of organic contaminants, as noted by Suresh et al.[4]. Such environmental alterations not only affect the physical and chemical properties of water but can also exert toxic effects on microbial communities[5], thereby disrupting the ecological balance and functionality of these ecosystems[6].

Microorganisms are central to the ecological functioning of lakes and reservoirs. They drive key biogeochemical processes, including carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling[7], and help maintain nutrient balance and water quality[8,9]. Additionally, microorganisms form intricate food web interactions with phytoplankton, zooplankton, and benthic organisms, which are crucial for ecosystem stability. Furthermore, microbial diversity is a key determinant of ecosystem resilience and its ability to withstand external disturbances. Higher microbial diversity enhances functional redundancy within the ecosystem, allowing it to sustain fundamental biogeochemical processes, despite environmental fluctuations. However, microbial diversity is not static. It is significantly influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, nutrient availability, pH, and oxygen levels, as well as anthropogenic activities such as heavy metal pollution[10]. These factors can alter microbial community composition and functionality, potentially reducing resilience and disrupting ecosystem stability[11].

Moreover, dynamic changes in microbial community structure can serve as indicators of aquatic environmental health[2]. Different microbial taxa exhibit varied responses to environmental factors, rendering shifts in community composition valuable as 'early-warning indicators' for water quality changes in lakes and reservoirs. For instance, changes in the abundance of specific indicator microorganisms can reflect the worsening of eutrophication, or advancements in ecological restoration[12]. Meanwhile, pharmaceuticals such as antibiotics can select for resistant strains, further complicating the ecological balance[13]. Different bacterial taxa exhibit varying sensitivities to environmental drivers. As a result, the shifts in community structure can serve as early-warning signals for eutrophication, pollution events, or ecological recovery. This makes microbial monitoring a promising approach for supporting freshwater ecosystem management and restoration efforts at both local and global scales.

Despite growing interest in microbial ecology, current studies often focus on specific regions or individual water bodies. Few studies have investigated bacterial communities in both lakes and reservoirs across diverse geographic contexts, especially at the global scale. Moreover, lakes and reservoirs have significant differences in their hydrology, nutrient dynamics, and management regimes, potentially resulting in distinct microbial assemblages and ecological processes. Understanding these differences is essential for developing predictive models of microbial responses[14,15].

The aim of this research is to comprehensively analyze the global patterns of bacterial diversity in aquatic ecosystems, with a specific emphasis on the distinct differences between sediment and water samples. This study reveals the intricate relationships between environmental variables and bacterial communities by analyzing the factors influencing bacterial community structures across regions and habitats. The dominant bacterial phyla present across various samples are also examined. Meanwhile, by analyzing and comparing the core community compositions of water and sediment, we gain valuable insights into their unique microbial network structures. Overall, these findings provide new insights into the global microbial biogeography of lentic ecosystems and contribute to the scientific basis for microbial-based water quality monitoring and ecosystem management under changing environmental conditions.

-

The research was guided by the question: 'How do region, habitat, and biophysiocochemical factors influence the diversity and the structure of bacterial communities in lakes and reservoirs?'

The review protocol was adapted from a previously published paper written by Gao et al.[15]. A search string was derived from the research question, incorporating terms such as 'bacterial communities' or 'microbial communities' + 'reservoirs' or 'lakes' + 'amplicon'. Databases used in the literature search included PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and CNKI. Relevant subject areas and source types were chosen in each database to filter out irrelevant articles. All articles were then exported to EndNote, and duplicates were removed.

The search scope was narrowed according to the following criteria: (1) The literature must include data with at least two environmental factors when considering the multiple impacts of environmental factors on the bacterial diversity of lakes and reservoirs; (2) For papers including multiple experiments conducted in different locations and catchment environments, the different locations and catchment environments are considered as separate observations; (3) When multiple publications used the same data from the same study, the data were recorded only once; (4) Numerical data were directly extracted from the tables and supplementary files, while data presented in figures were extracted using Graphixy software. In the initial screening stage, a total of 4,854 studies were identified based on title and abstract review. After full-text assessment according to predefined inclusion criteria, 80 studies were finally included in the analysis.

Data extraction

-

To ensure the consistency and reliability of the analyzed data, a systematic data extraction approach was adopted. Given the diversity of methodologies across studies, particular attention was paid to data normalization and integration. In many cases, the provided sequence identifiers could not be easily matched to the entries in gene databases. Additionally, the studies revealed the differences in DNA extraction methods, sequencing depth, PCR amplification primers, and clustering similarity levels, making quantitative analysis with raw sequences unfeasible. Therefore, the analyses utilized bacterial relative abundance at the phylum level instead of raw sequence data.

Data extraction was performed for all articles based on several pre-established data fields. The main data extraction fields included: (1) the name and type of the sample analyzed (water/sediment); (2) the region and latitude/longitude of the analyzed sample; (3) the alpha diversity indices of the analyzed sample; (4) the relative abundance at the level of the bacterial phylum detected; and (5) the environmental parameters detected.

Statistical analyses

-

Missing data were input using the hotdeck function from the 'VIM' package in R (version 4.3.2), which fills in missing values based on similarities between individuals, thereby preserving data consistency and integrity. Statistical analyses to compare microbial diversity across different continents and habitats were conducted using SPSS software (version 26). Boxplots were generated using SPSS to visualize the distribution of Shannon and Chao 1 indices across different continents and habitats. To assess the differences in diversity indices between groups, independent samples t-tests were performed for comparisons between two groups (sediment vs water), and one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons across multiple continents. Additionally, post hoc tests were conducted to identify specific group differences following significant ANOVA results. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to explore the direct and indirect effects of multiple environmental factors on bacterial diversity. The SEM was constructed using the plspm package in R (version 4.3.2). The model consisted of five blocks of ecologically based latent variables: latitude; water quality parameters (including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity); nutrient factors (including NH4+-N, NO2–-N, NO3–-N, TN, and TP); chlorophyll a; and bacterial diversity indices (including Shannon and Chao 1). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to fit the model. All input variables were standardized prior to modeling, and path coefficients were assessed for significance at the 0.05 level.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed using the RDA function in the vegetarian R package, the community distance matrix, and the hydro chemical factors. In addition, a new water quality assessment method, the Bacterial Eutrophication Index (BEI) proposed by Ji et al.[16], classifies lake and reservoir eutrophication levels into six groups: Oligotrophic (BEI ≤ 0.25), Oligo-mesotrophic (0.25–0.3), Mesotrophic (0.3–0.35), Light eutrophic (0.35–0.65), Middle eutrophic (0.65–1.3), and Hyper eutrophic (> 1.3)[16]. This method complements traditional physical and chemical parameter assessments and highlights the close relationship between microbial communities and water quality. Microsoft Excel 2016 was used to calculate BEI values, and Origin software was used to plot the distribution of bacterial phyla in lake water and sediment, as well as across different nutrient levels[16]. The calculation formula for BEI is as follows:

$ BEI=\dfrac{Cyano\_A}{Actino\_A}\left(\dfrac{1}{-0.1065+0.09732T-0.00253{T}^{2}}\right) $ In this equation, Cyano_A and Actino_A represent the relative abundances of Cyanobacteria and Actinobacteria, respectively, while T denotes temperature.

A Mantel test was used to determine physical and chemical indicators and sampling geographical distance that were significantly correlated with community compositions.

-

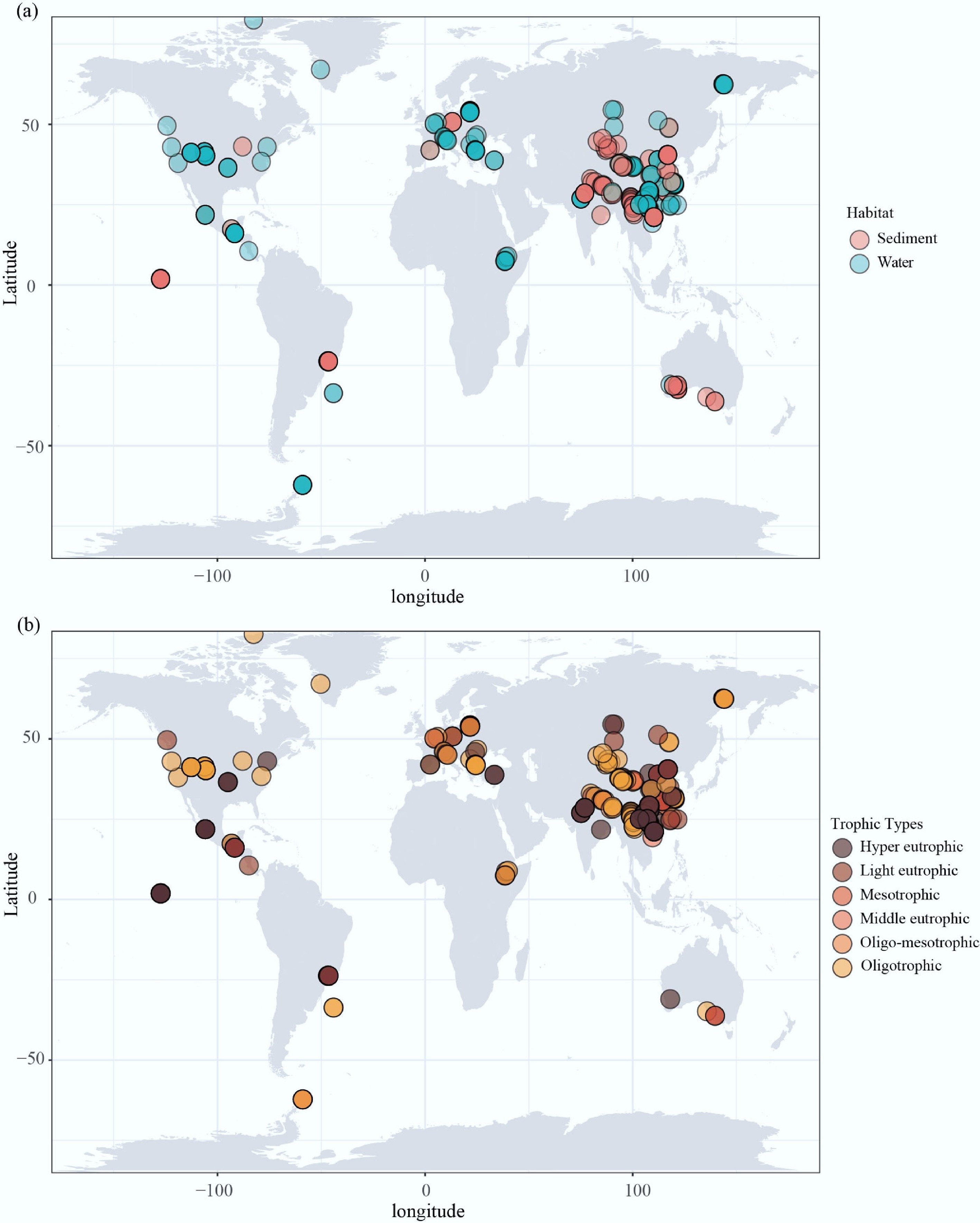

A total of 379 publicly available amplicon sequencing datasets from water and sediment samples were analyzed (Fig. 1a), encompassing a wide geographical distribution that covers six continents.

Figure 1.

Global distribution map of 379 selected lakes reservoirs. Global map showing locations, (a) sample types, and (b) trophic types of 379 lakes and reservoirs studied here.

This broad distribution provides a representative overview of global lakes and reservoirs. However, the dataset shows a clear geographical imbalance: more than 60% of the samples originated from Asia (n = 235), while fewer datasets were collected from North America (n = 65), Europe (n = 44), South America (n = 22), Africa (n = 7), and Oceania (n = 5). Among the countries, China had the highest number of surveys. While the dataset broadly represents global distribution, it is important to acknowledge the limited number of samples from Africa and Oceania, which may limit the resolution of microbial biogeographic patterns in these regions.

This disproportionate representation may introduce regional biases that affect the interpretation of microbial biogeographic patterns, particularly by overemphasizing trends prevalent in Asian lakes and reservoirs. To address potential biases caused by uneven sampling across regions, samples were grouped by continent in the data analysis, strengthening within-group comparisons to reduce the influence of high-sampling regions on global patterns. Additionally, latitude was introduced as a continuous geographical variable to capture large-scale biogeographical gradients and mitigate the effects of regional imbalances. While these methods cannot fully compensate for limitations arising from missing metadata (such as sampling season or methodological differences), they contribute to a more balanced and interpretable assessment of microbial diversity and its environmental drivers across global freshwater systems.

Regarding trophic status (Fig. 1b), lakes and reservoirs in North America are primarily classified as mesotrophic to oligotrophic. In contrast, European sites exhibit a broad trophic gradient ranging from oligotrophic to eutrophic, demonstrating substantial variability in nutrient status.

Variations in α-diversity across habitats and regions

-

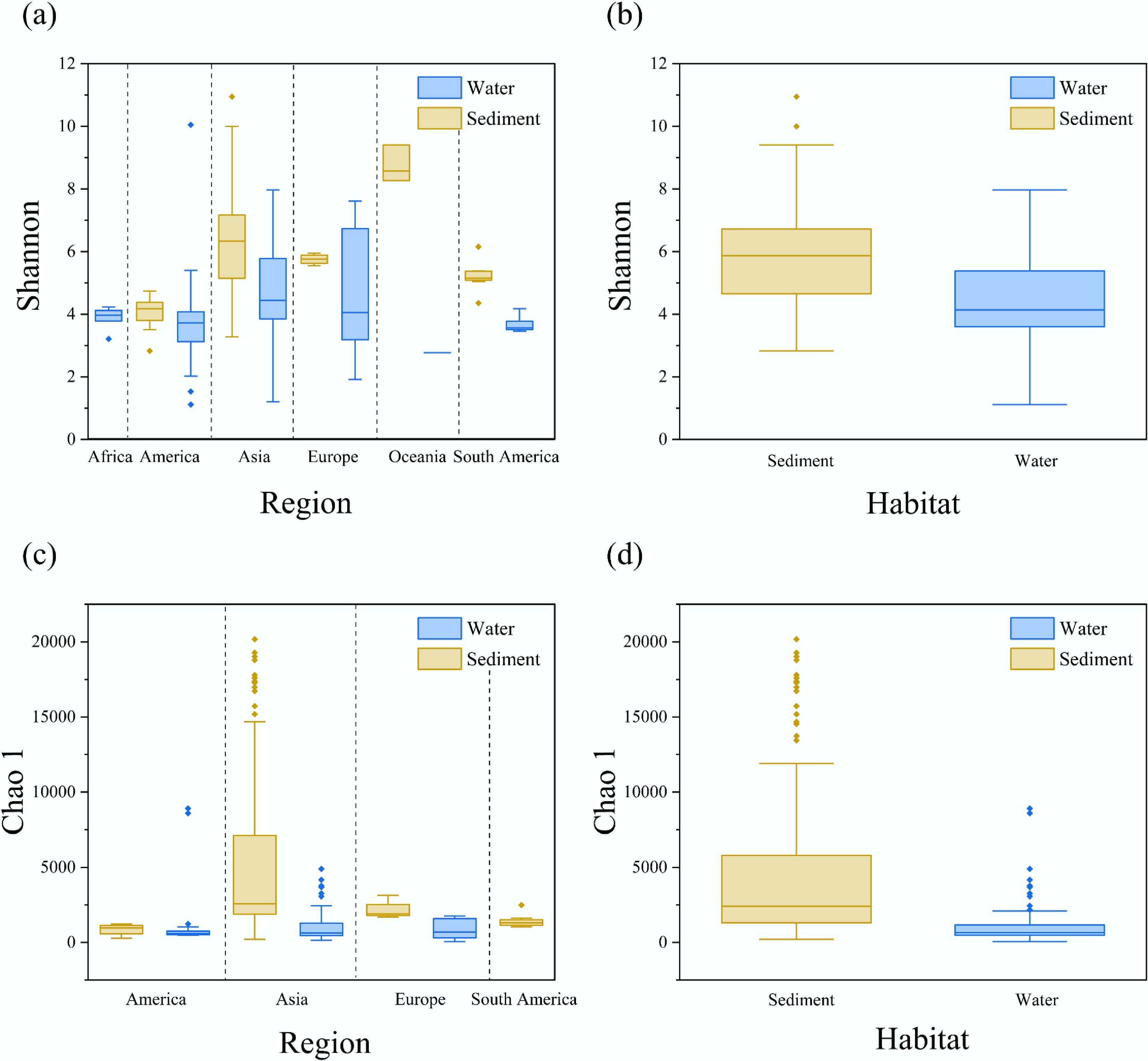

From the perspective of different habitats, Fig. 2a illustrates the distribution of Shannon indices in water (blue), and sediment (brown) samples across various regions. It is evident that sediment samples generally exhibit higher Shannon indices than water samples, indicating a relatively higher microbial diversity in sediments. Moreover, the variation in Shannon indices is more pronounced in sediment samples, reflecting greater heterogeneity in microbial communities. These observations are statistically supported: independent samples t-tests confirmed significant differences in both Shannon and Chao 1 indices between sediment and water samples (p < 0.05), suggesting a consistent pattern of higher bacterial diversity in sediments.

Figure 2.

Changes in α-diversity across habitats and regions. (a) Shannon index, and (c) Chao 1 index of bacterial communities in sediment and water habitats across different regions. An overall comparison of (b) Shannon index, and (d) Chao 1 index between sediment and water habitats, with sediment shown in brown, and water shown in blue.

Consistently, Fig. 2c shows that sediment samples also possess higher Chao 1 indices compared to water samples, further affirming greater species richness. The Chao 1 variation is especially pronounced in sediment samples, with some from Asia exceeding 20,000. This phenomenon is further supported by previous studies, which have shown that sediments tend to provide more stable microenvironments, and richer organic matter, fostering diverse microbial taxa[17,18]. Furthermore, Akinnawo and Vasistha reported that the complex physicochemical conditions of sediments, such as redox gradients, particle size heterogeneity, and organic content, create favorable niches for microbial colonization and survival[5,19].

Tukey HSD post hoc tests further reveal regional differences in microbial diversity. For sediment samples, significant differences in the Shannon index were found between Asia and America, and Oceania (p < 0.05). In water samples, Asia and America also showed significant differences (p < 0.05). These findings align with those of Zhi et al.[17], who emphasized that geographical variation and environmental factors shape bacterial distribution patterns across habitats[19]. Hydrodynamic conditions and nutrient availability may also contribute to observed patterns[20]. Cheng et al. found that bacterial diversity in aquatic ecosystems is closely related to nutrient levels and water movement, which varies across regions and habitats[20].

In summary, this study highlights clear habitat- and region-specific patterns in bacterial diversity. These findings underscore the importance of considering both habitat type and regional context when investigating microbial diversity and ecological functioning in lake and reservoir ecosystems.

Environmental drivers of bacterial α-diversity across habitats

-

The analysis based on Spearman analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1), Generalized Additive Models (GAM), and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) reveals distinct spatial and environmental response patterns of bacterial α-diversity in water and sediment ecosystems. As shown in Supplementary Figs S2 and S3, environmental gradients shape bacterial diversity through multiple non-linear pathways. In water samples, a distinct peak in the Chao 1 index was observed near 7 mg/L dissolved oxygen (DO) (Supplementary Fig. S3a). This is consistent with the findings of He et al. and Cai et al., which highlight the importance of oxygen availability in supporting metabolically versatile bacterial communities[21,22]. Moderate DO levels likely support both aerobic and facultative anaerobic taxa, whereas very high or very low DO levels may limit microbial diversity[23].

Temperature also had a significant effect on the Shannon index (p = 0.0006, GAM), a finding that was further supported by a significant positive correlation in the Spearman analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). The smoothed trend line indicated that Shannon diversity was relatively high at lower temperatures (below 25 °C) but declined as the temperature increased. This pattern likely reflects both direct and indirect effects of rising temperatures on bacterial communities. While moderate temperature increases can stimulate bacterial metabolic rates, excessively high temperatures may exceed the optimal growth range for many taxa, reducing community evenness and richness. Additionally, elevated temperatures reduce dissolved oxygen concentrations, particularly in bottom waters, leading to more reductive conditions in sediments. These anaerobic conditions promote the release of nutrients such as ammonium and phosphate through processes like iron reduction and organic matter mineralization[24,25]. The resulting changes in redox potential and nutrient availability can alter microbial niches, suppress sensitive or less competitive taxes, and ultimately reduce overall diversity.

Moreover, the observed turning point near 25 °C may indicate a threshold beyond which ecological functioning, such as nutrient retention or organic matter degradation, could be significantly disrupted. Traditional linear models often overlook such nonlinear or multi-threshold responses. In contrast, the use of generalized additive models (GAMs) in this study effectively captured complex relationships between diversity and environmental variables, highlighting the method's strength in ecological inference. The GAM-derived trends emphasize the need to consider nonlinear environmental effects when evaluating microbial stability in response to global warming.

Bacterial α-diversity in water remains relatively stable at low latitudes but decreases sharply above 60° latitude, a trend that is consistent with Wu et al. and Wang et al., who linked such declines to lower temperatures and primary productivity at high latitudes[9,26]. Similarly, Yuan et al. suggested that reduced nutrient availability and thermal constraints in cold regions can suppress microbial growth and richness[27].

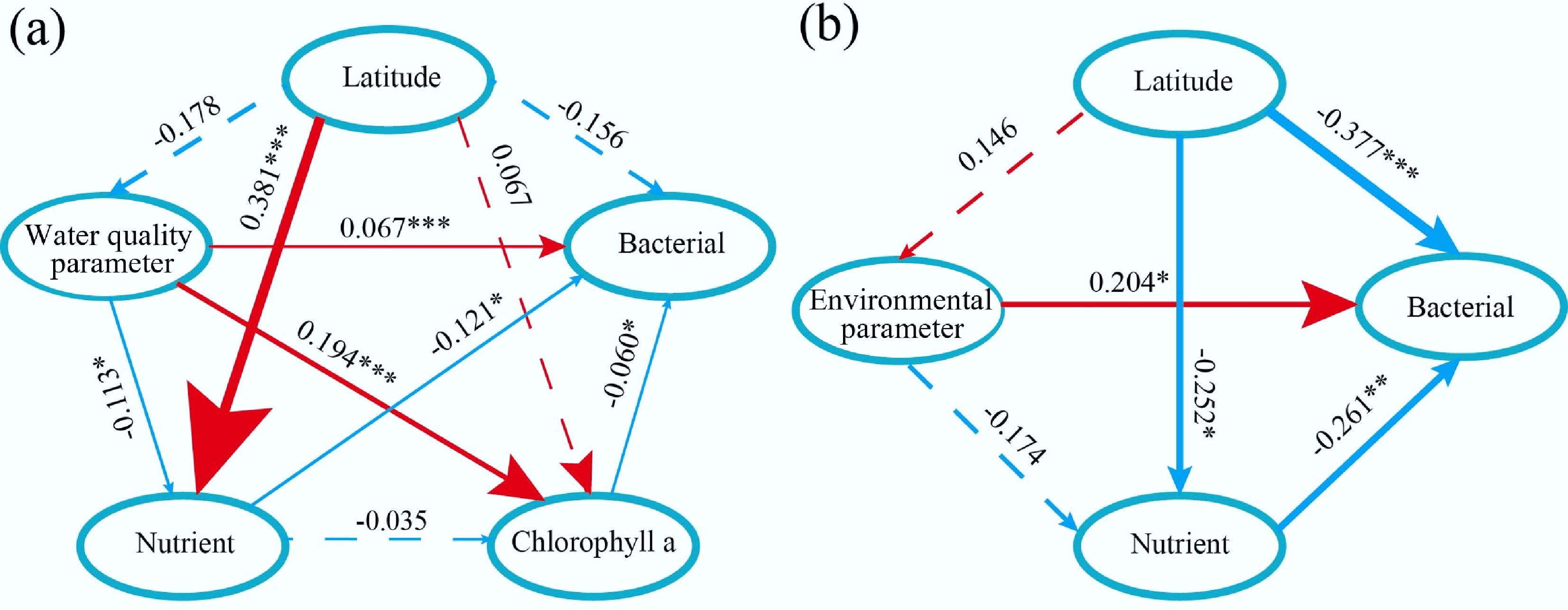

Nutrient levels, particularly TN and NO3–-N, have contrasting effects on bacterial diversity: they negatively influence diversity in water habitats but have a positive effect in sediments. The GAM results show a slight decline in the Shannon index with increasing nutrient concentrations in water, whereas the opposite trend is observed in sediments. This contrasting effect of nutrient levels on bacterial diversity between water and sediment habitats reflects differences in nutrient dynamics and ecological niches. In aquatic systems, elevated nutrient inputs—particularly TN and NO3–-N— favor the proliferation of taxa such as Cyanobacteria, which have a competitive advantage in nutrient-rich waters, and consequently reduce community evenness[28]. In contrast, in sediments, nutrients such as nitrogen compounds can enhance microbial diversity by supporting a variety of redox processes and metabolic pathways. This positive relationship has also been observed by Li et al., who noted that nitrogen-rich sediments support a broader range of functional microbial guilds, including nitrifiers, denitrifies, and anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria[1]. Therefore, the contrasting trends revealed by the GAM results highlight the importance of habitat-specific nutrient cycling in shaping bacterial community structure. Although SEM analysis of sediment reveals a negative path coefficient of –0.121 between nutrients and bacterial diversity (Fig. 3a), this finding is consistent with studies showing that excessive nutrient inputs favor dominant opportunistic taxa, reduce evenness, and suppress overall richness[29,30].

Figure 3.

Controlling factors of different bacterial communities. Partial least squares-path models illustrate the effects of different factors on bacterial diversity variation in (a) water, and (b) sediment. Red lines indicate positive effects, and blue lines indicate negative effects. Significance level, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The role of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) as a mediating variable is also highlighted. SEM analysis shows that the concentration of Chl-a affects bacterial diversity directly (path coefficient = –0.06). Phytoplankton, represented by Chl-a, contributes to microbial diversity through organic matter production, nutrient cycling, and oxygen fluctuations[31−33]. While moderate phytoplankton biomass supports diverse heterotrophic bacteria, high biomass or bloom decay may lead to hypoxia, thereby selecting for anaerobic taxa[34]. The structural equation model also revealed that water quality parameters exerted a significant positive effect on chlorophyll-a concentration (path coefficient = 0.194, p < 0.001).

Importantly, most relationships observed in GAM analysis are non-linear, suggesting threshold effects[35,36]. These dynamic responses underscore the interactive and non-linear nature of environmental controls over microbial community composition[37]. The reliability of the GAM models was confirmed through diagnostic checks of residuals and smoothing function convergence (Supplementary Fig. S4).

In sediment systems, latitude plays a central role in shaping bacterial diversity, with a strong direct effect (path coefficient = –0.377) as well as an indirect effect mediated through its influence on nutrient concentrations (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S5). This supports earlier findings that latitudinal gradients influence microbial assembly via temperature regimes, radiation input, and nutrient cycling[38−40]. Lakes in lower latitudes generally receive higher nutrient inputs and experience longer stratification periods, enhancing microbial productivity and biogeochemical cycling[41−43]. In contrast, high-latitude lakes tend to be nutrient-limited due to seasonal mixing, which reduces surface productivity. In addition, environmental parameters exert a significant positive direct effect (path coefficient = 0.240) on bacterial diversity in sediments. This may be attributed to the relatively stable and buffered environment that sediments provide[44], which reduces the volatility of environmental fluctuations and allows stronger selection by key geochemical variables.

Overall, bacterial α-diversity in both water and sediment ecosystems is shaped by complex, habitat-specific interactions with environmental factors. Water systems exhibit more variable and multi-level interactions (including indirect trophic pathways), while sediments are governed by fewer but stronger direct environmental controls, especially latitude, pH buffering, and nutrient load. These findings offer valuable insights into microbial biogeography and the resilience of microbial communities under changing environmental conditions.

Bacterial community compositional variation

-

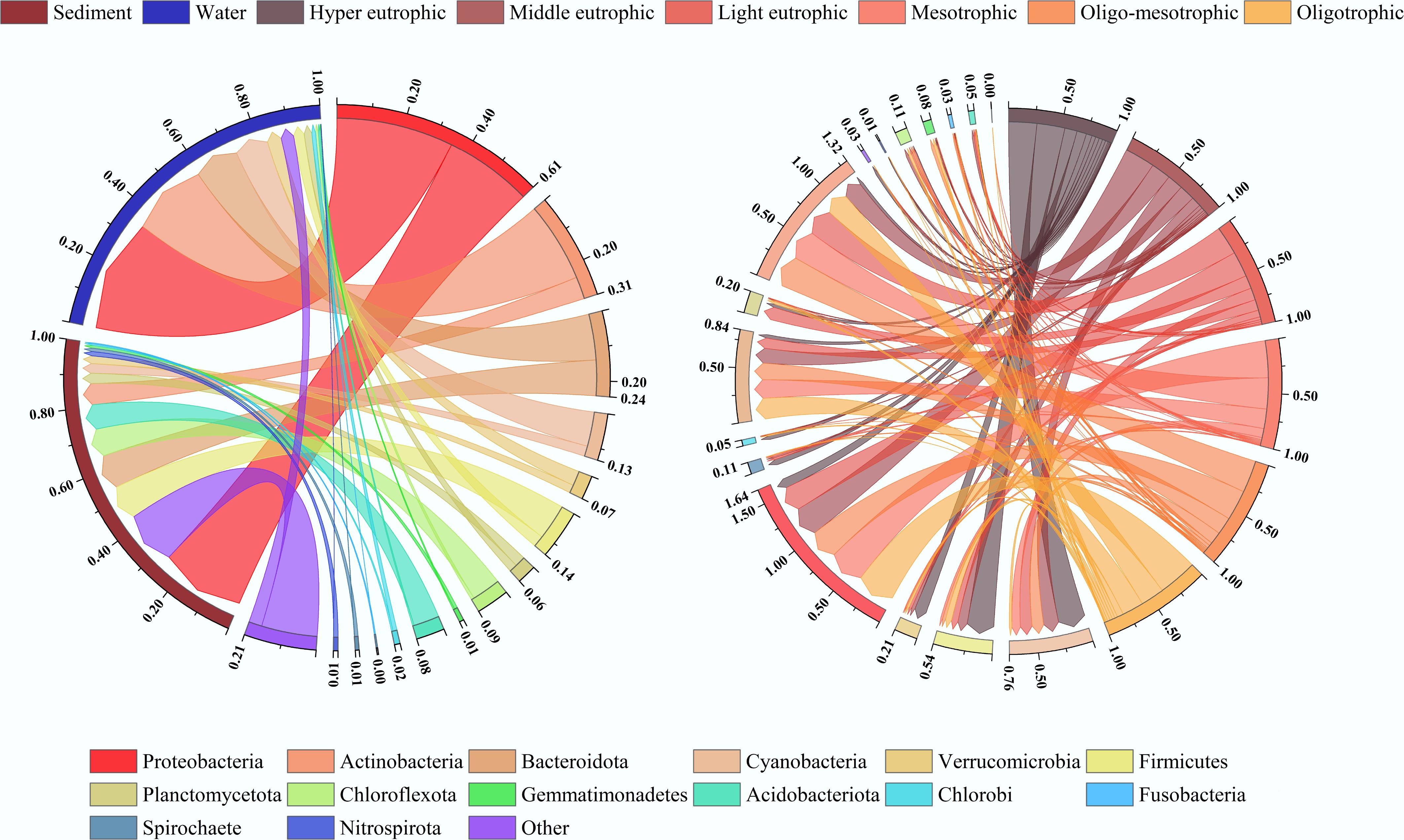

The phylum-level taxonomic composition of bacterial communities demonstrates clear habitat- and trophic state-specific patterns across all sampled environments (Fig. 4a). Overall, Proteobacteria (30.7%) was the most dominant bacterial phylum, which aligns with findings by Geng et al. and Wang et al., who highlighted that the metabolic versatility of Proteobacteria enables them to adapt to diverse ecological niches and nutrient conditions[45,46]. Their high relative abundance across water and sediment samples suggests strong ecological plasticity that allows them to persist in both oligotrophic and eutrophic states[26].

Figure 4.

Bacterial community compositional variation. (a) Distribution of bacterial phyla in water and sediment samples from lakes and reservoirs. (b) Distribution of bacterial phyla across different trophic types of lakes and reservoirs. The width of the lines in the figure reflects the relative abundances of bacterial phyla (summed to 100%).

In aquatic habitats, Actinobacteria (15.3%) and Cyanobacteria (6.7%) exhibit relatively high abundances, consistent with earlier studies by Yang et al.[47], which reported that these phyla thrive under conditions with sufficient light and nutrients. Figure 4b further illustrates that while Proteobacteria dominate across multiple trophic categories, Cyanobacteria and Actinobacteria are more prevalent in eutrophic states, reinforcing the observation by Wang et al. that the ability of Cyanobacteria to fix nitrogen and utilize high nutrient loads gives them a competitive advantage in nutrient-rich waters[46].

Other phyla, including Firmicutes (7.0%), Chloroflexota (4.7%), and Acidobacteriota (4.1%), although less abundant overall, display distinct habitat-specific preferences rather than being evenly distributed across environments. For instance, Firmicutes is often enriched in sediments rich in organic matter and characterized by relatively stable physicochemical conditions, consistent with its capacity to degrade complex organic substrates[8]. Chloroflexota, on the other hand, is commonly associated with anaerobic niches, reflecting its specialization in processes such as photoheterotrophic metabolism and anaerobic respiration[48]. Acidobacteriota is generally more abundant in moderately eutrophic environments. Thus, different phyla tend to be restricted to environments that align with their metabolic and physiological traits, rather than being broadly distributed across all lake and reservoir habitats.

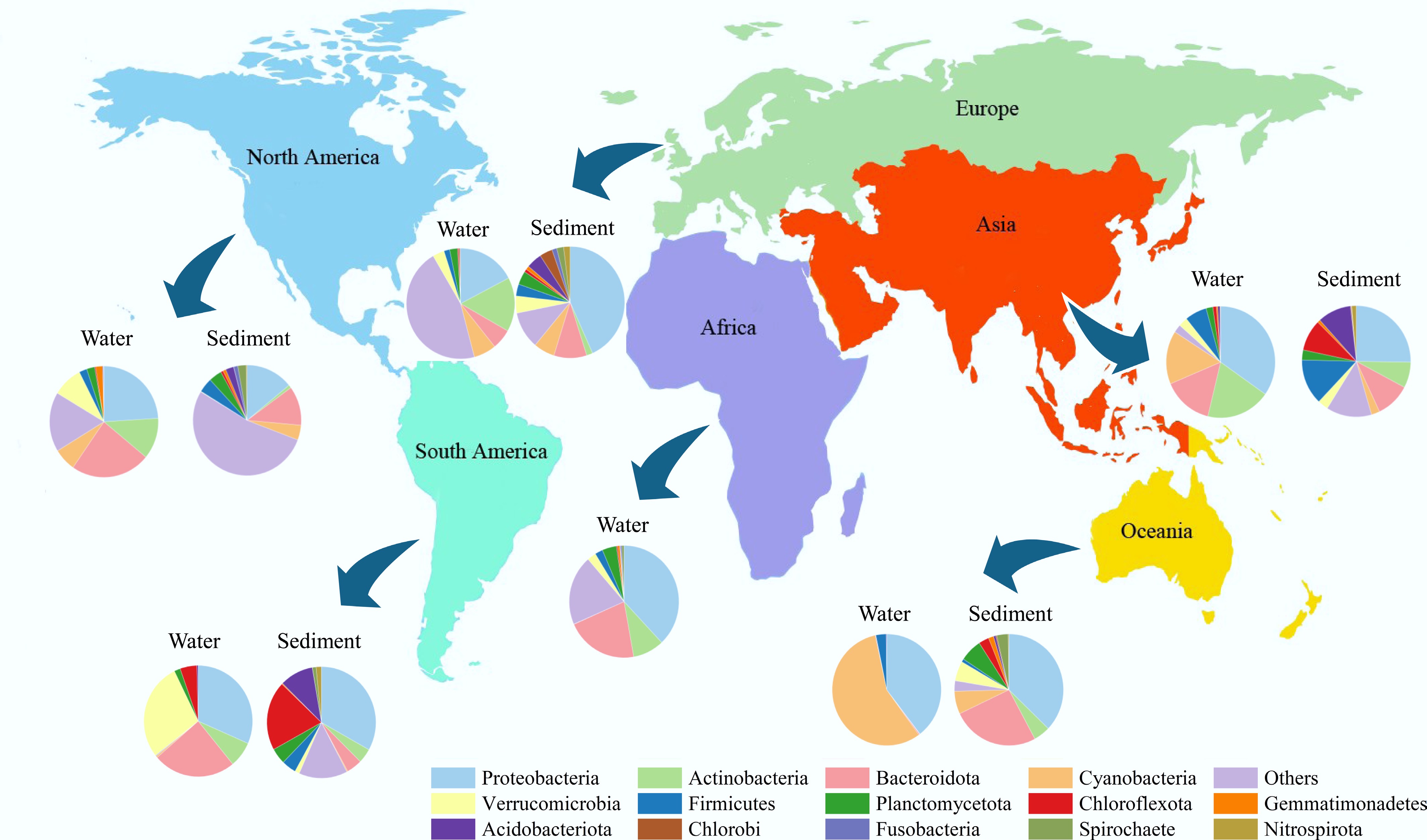

In addition, Fig. 5 shows that bacterial community structures across water and sediment samples vary substantially across continents, indicating notable spatial heterogeneity. This finding suggests that, beyond local trophic conditions, broader-scale geographic and environmental factors shape bacterial community composition. Such patterns align with the broader understanding that bacterial biogeography is driven by a complex interplay of nutrient availability, hydrological conditions, and regional environmental variability[45–47].

Figure 5.

Composition of bacterial communities in waters and sediments at the phylum level among regions.

Together, these results demonstrate that the dominant bacterial phyla adaptively occupy specific habitats and trophic states, driven by their metabolic traits and the local physicochemical conditions. The clear habitat-specific distribution and regional differences underscore the need to consider both local and large-scale drivers when studying microbial community assembly in aquatic ecosystems.

Multivariate analysis of environmental factors and bacterial communities

-

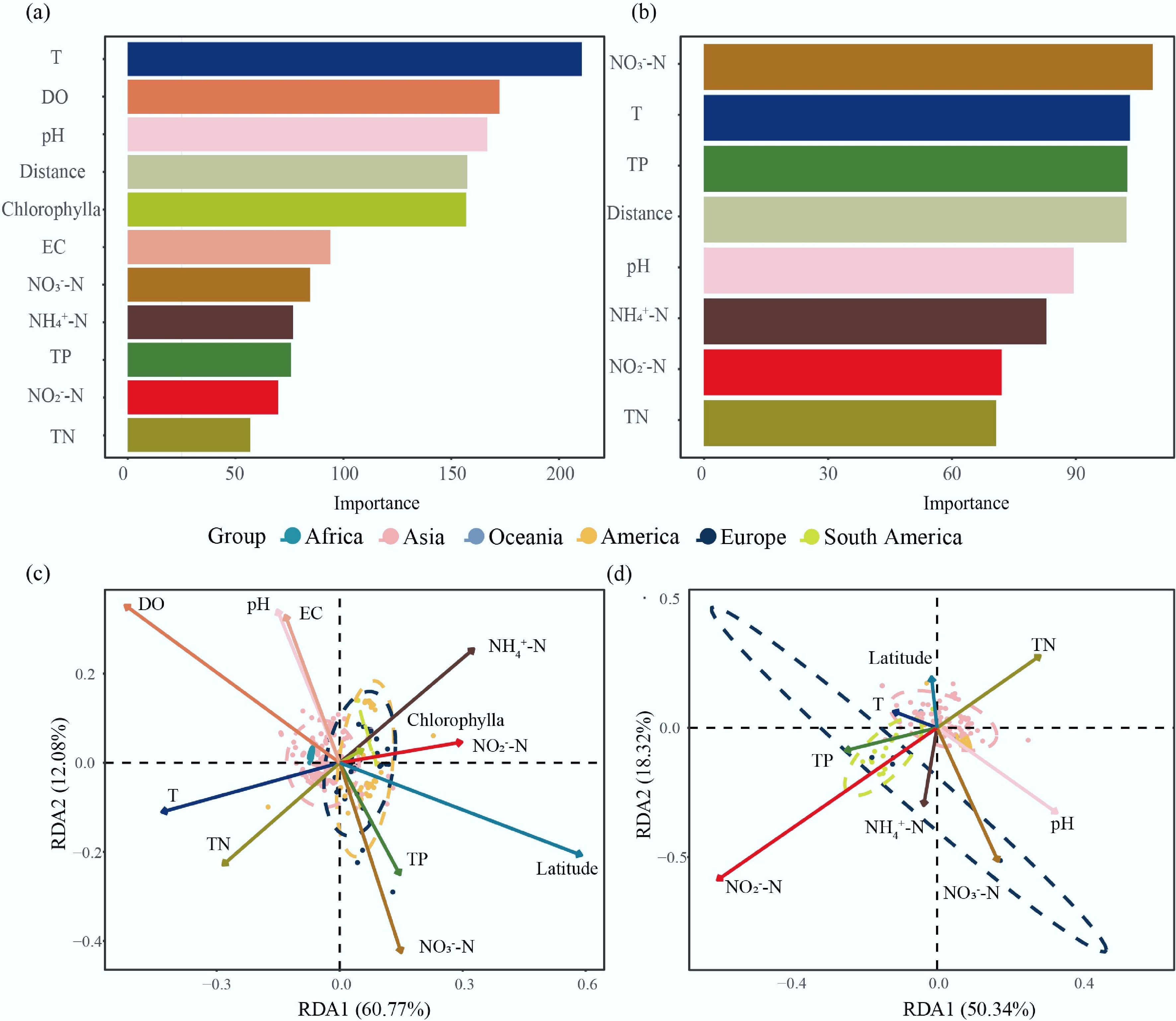

The results of the random forest analysis show significant differences in the key environmental factors influencing bacterial community structure in water and sediment. In the aquatic ecosystem (Fig. 6a), temperature (T) is the most important environmental factor affecting bacterial community structure, with an importance value close to 200, far surpassing other factors. DO and pH follow as the second and third most important factors, respectively. Distance factors and chlorophylla concentration also show considerable importance in sediment. In contrast, nutrient indicators, such as conductivity, nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N), ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), and TP, are of relatively lower importance, though they still contribute to the explanation of community structure. In contrast to the aquatic system, in the sediment ecosystem, the concentration of NO3–-N exhibits the highest importance value. Temperature and TP concentration rank second and third, respectively, also exhibiting high importance. Notably, pH plays a relatively minor role in the sediment system, which contrasts significantly with its role in the water system.

Figure 6.

The impact of environmental factors on bacterial community structure. Random forest models illustrate the ranking of variable importance for: (a) water, and (b) sediment samples. Redundancy analysis (RDA) plot showing the relationship between biogeochemical parameters and bacterial community composition in: (c) water, and (d) sediment. The vectors represent the biogeochemical variables, and their lengths and directions indicate the strength and direction of the correlations with the bacterial community. Abbreviations: T (temperature), DO (dissolved oxygen), EC (electric conductivity), NO3–-N (nitrate nitrogen), NH4+-N (ammonia nitrogen), TP (total phosphorus), NO2–-N (nitrite nitrogen), TN (total nitrogen).

RDA results presented in Fig. 6c show that the bacterial community structure in water is significantly influenced by environmental factors. The first and second axes of the RDA explain a total of 72.85% of the variation (with RDA1 explaining 60.77% and RDA2 explaining 12.08%). Key environmental drivers of the bacterial community structure in water include DO and latitude. Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH show a strong positive correlation. Although sampling points from different continents exhibit some clustering, overlaps are still observed between regions.

In contrast, the RDA results for the sediment bacterial community structure show that environmental factors explain a relatively lower proportion of the variation, with the first and second axes accounting for 68.66% of the total variation (RDA1: 50.34%, RDA2: 18.32%). Notably, the concentration of nitrite nitrogen (NO2–-N) has a high positive explanatory power for sediment bacterial community structure in South America, while TN shows a significant negative correlation.

Ecological networks of bacterial communities

-

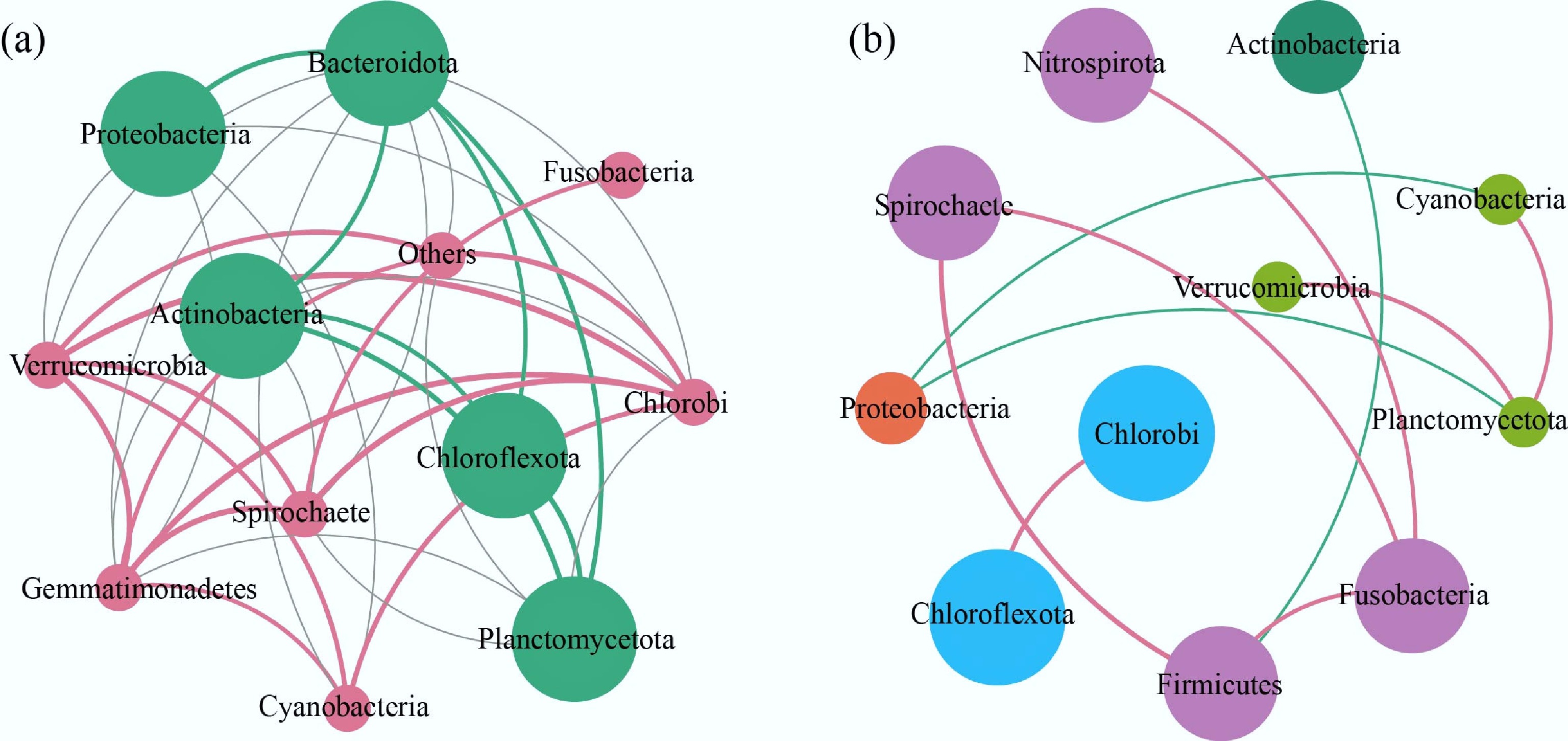

Figure 7 illustrates the complex interspecies relationships within bacterial communities in both water and sediment environments. The two habitats exhibit distinct levels of network complexity (Supplementary Fig. S6), with notably different topological characteristics that reflect their contrasting ecological dynamics.

Figure 7.

Bacterial co-occurrence network. (a) Water and (b) sediment bacterial networks across lakes and reservoirs. The thickness of the line is directly proportional to the correlation coefficient.

The comparative network analysis shows that the bacterial network is denser in the water system, with more nodes and edges, indicating higher network density and greater ecological connectivity. Such structural complexity suggests intensified ecological interactions, such as niche overlaps, cross-feeding, and competition among bacterial taxa in the water column. Several factors may contribute to this phenomenon. First, the water column typically represents a more open and dynamic system, where microbial communities are exposed to rapid and frequent environmental fluctuations (e.g., oxygen and nutrient pulses), which can increase the frequency and intensity of biotic interactions. Second, dispersal rates of bacteria are generally higher in aquatic environments due to water movement and mixing, facilitating opportunities for biotic interactions that promote network connectivity. Third, aquatic habitats tend to be dominated by copiotrophic, fast-growing taxa, which can respond quickly to resource availability and often form highly interactive networks[49]. Sun et al. similarly observed that denser microbial interactions in water imply overlapping niches and frequent resource competition[50].

In contrast, the sediment network is sparser, with fewer connections and a more modular structure. This pattern reflects the more stable, heterogeneous, and compartmentalized nature of sediment environments, where physical diffusion is slower and microhabitats are more spatially isolated. Under such conditions, microbial dispersal is limited, and community assembly is more strongly shaped by environmental filtering and niche specialization. Sediment bacteria are often slow-growing in anoxic or microoxic conditions, with narrower ecological niches and reduced interspecific competition, thereby contributing to a simpler and more modular network structure[51].

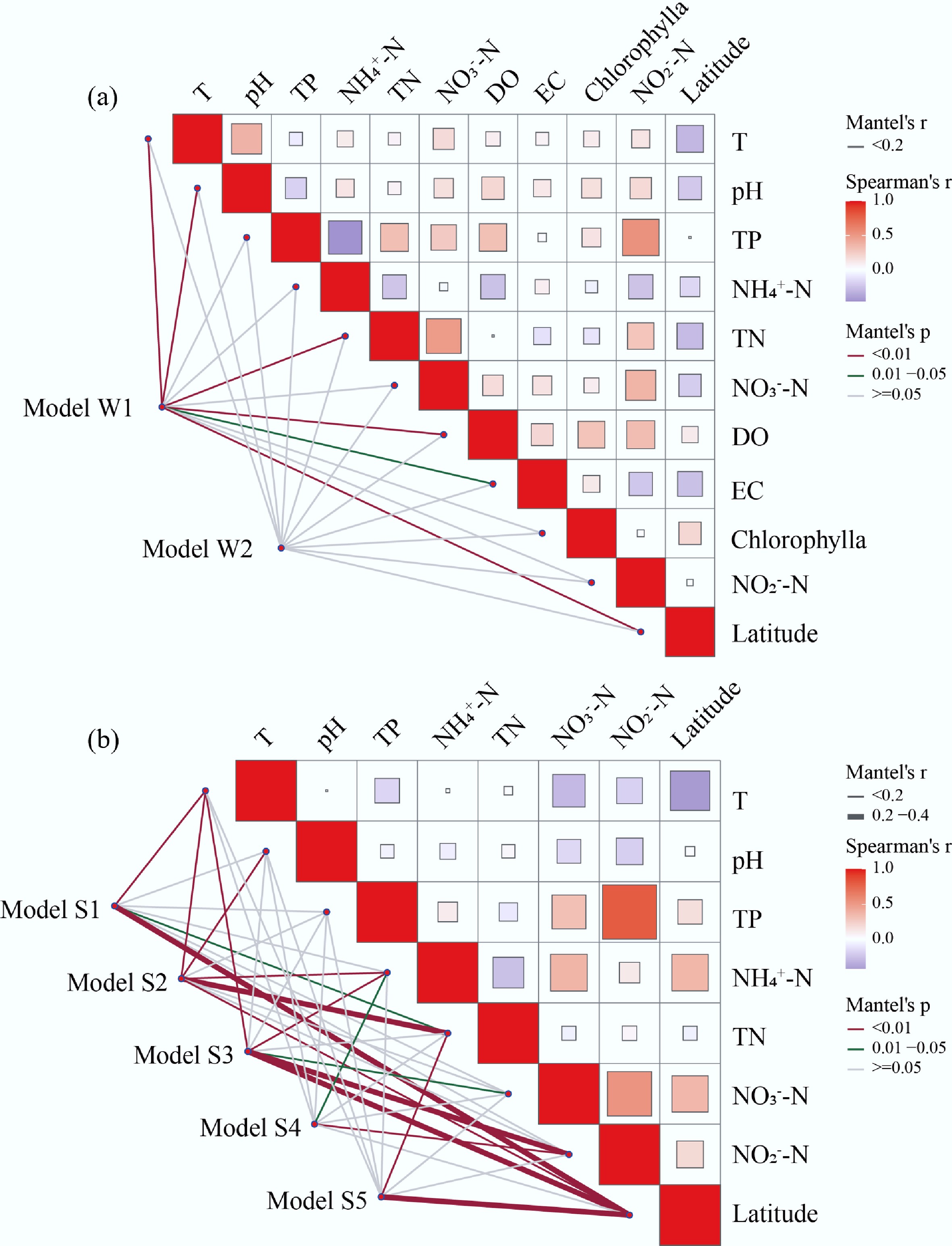

At the modular level, the water network modules show distinct environmental associations. Model W1, which mainly includes Spirochaete, Verrucomicrobia, and Gemmatimonadetes, displays strong correlations with temperature, pH, TN, DO, and latitude. These taxa are often linked to organic matter degradation, suggesting that Module W1 may play a key role in the carbon cycle. In contrast, Model W2, dominated by Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Chloroflexota, shows weaker environmental correlations, but may be involved in anaerobic metabolic pathways, consistent with the metabolic flexibility of these phyla[52].

In the sediment system, the network structure reveals modules with distinct biogeochemical functions and environmental sensitivities. For example, Model S1, containing Spirochaete, Nitrospira, and Verrucomicrobia, is likely involved in nitrogen cycling under hypoxic or anaerobic conditions, with Nitrospira serving as key nitrite oxidizers[53]. Model S2, including Cyanobacteria and Planctomycetes, may contribute to organic carbon assimilation, while Model S3, dominated by Chlorobi and Chloroflexota, likely plays a role in anaerobic sulfide degradation. Additionally, Model S4, mainly composed of Proteobacteria, could be a keystone group driving multiple biogeochemical cycles[54]. Notably, Model S5, dominated by Firmicutes and Fusobacteria, may represent bacteria capable of degrading complex organic molecules in sediment environments with fluctuating pH, highlighting the adaptability of these taxa to dynamic geochemical conditions. These distinct module-environment associations for both water and sediment networks are visually summarized in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Relationships between environmental variables and ecological networks within lakes reservoirs worldwide. Pairwise correlations of the variables are shown with a color gradient denoting Spearman's correlation coefficient. Spatial variables include latitude. Environmental variables include T, pH, DO, EC. Nutrient variables include TP, NH4+-N, TN, NO3–-N, NO2–-N. Biological variables include chlorophylla. The red lines represent significant correlations (p < 0.01) between bacterial community structures and environmental, spatial, biological, or nutrient variables, while the green lines indicate moderate correlations (0.01 ≤ p < 0.05), and the gray lines denote non-significant correlations (p ≥ 0.05) based on the Mantel test.

The varying associations between modules and environmental factors further highlight habitat-specific drivers of community assembly. In water, modules are more strongly influenced by temperature, pH, DO, and latitude, whereas in sediments, the network shows stronger links to latitude and nitrogen-related variables, such as TN and NO2–-N. This pattern supports the view that sediment bacterial communities are more strongly shaped by local geochemical gradients and spatial heterogeneity, resulting in distinct geographical distribution patterns.

In summary, these findings demonstrate that, while both aquatic and sedimentary bacterial communities maintain complex interspecies associations, their network structures, modular compositions, and functional roles differ markedly due to contrasting environmental dynamics and ecological interactions. The denser, highly connected water networks reflect a dynamic and competitive microbial environment, whereas the simpler sediment networks highlight the role of localized environmental filtering and functional specialization in structuring benthic microbial communities.

-

This study provides a comprehensive global analysis of bacterial diversity, distribution, controlling factors, and network structures across different habitats. The findings confirm that sediments generally harbor higher bacterial diversity than water due to stable conditions and organic matter accumulation. Geographical patterns in bacterial α-diversity are shaped by the combined effects of latitude and nutrient levels. Proteobacteria dominates across ecosystems, while Cyanobacteria thrive in eutrophic waters, reflecting habitat-specific distributions. Water microbial networks exhibit greater complexity and connectivity, whereas sediment networks are sparser due to niche differentiation. Overall, this study enhances the understanding of the mechanisms regulating microbial communities and highlights their implications for water quality.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0003.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision: Zhang H; investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft: Huang Y; validation, writing-review and editing: Liu X, Ma B, An S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was funded by the Shaanxi Outstanding Youth Science Foundation Project (Grant No. 2025JC-JCQN-019), supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20250855), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52270168, 52570213, and 52500012).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Bacterial diversity was higher in sediment than in water.

Proteobacteria were important across multiple environments.

Cyanobacteria were more common under eutrophic conditions.

The co-occurrence network in water is more complex than in sediment.

Biogeochemistry influences the composition of bacterial communities.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Spearman correlation coefficients for correlations between bacterial diversity indices and environmental variables.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Relationships between Shannon and biophysiochemical factors in lakes and reservoirs based on generalized additive models (GAM).

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Relationships between Chao 1 and biophysiochemical factors in lakes and reservoirs based on generalized additive models.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Generalized additive model diagnostic plot.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Direct, indirect, and total effects of controlling factors on bacterial communities in water and sediments.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Distribution of percentages for different model categories.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang H, Huang Y, Liu X, Ma B, An S. 2025. Exploring bacteria communities in lakes and reservoirs: a global perspective. Biocontaminant 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0003

Exploring bacteria communities in lakes and reservoirs: a global perspective

- Received: 04 July 2025

- Revised: 09 September 2025

- Accepted: 22 September 2025

- Published online: 31 October 2025

Abstract: Understanding bacterial biogeography is crucial for managing freshwater ecosystems. However, global comparisons of bacterial communities in lakes and reservoirs remain limited. This study synthesized bacterial community data from 247 water and 131 sediment samples across diverse geographic regions through a global literature review. Bacterial diversity and community structure were compared between water and sediment, aiming to identify key environmental drivers and biogeographical patterns. The present results show that sediment samples generally exhibit higher and more variable bacterial diversity than water samples. Generalized additive models revealed that total phosphate is negatively correlated with the diversity of bacterial communities in water. In sediments, the regulatory effect of total nitrogen on community richness is particularly significant. Structural Equation Modeling showed that latitude gradients and nutrient concentrations jointly drive geographical variation in bacterial α diversity. By constructing a global standardized database, the indicative role of core groups such as the Proteobacteria phylum in lakes and reservoirs with different nutrient levels has been established, while Cyanobacteria and Actinobacteria are enriched in eutrophic environments. The results of Random Forest analysis showed that temperature was the most important environmental factor affecting bacterial community structure in water, while nitrate nitrogen showed the highest importance in sediment. Network analyses further showed that bacterial communities in water formed more complex and interconnected networks than those in sediments. These findings reveal the global distribution patterns of bacterial communities in water and sediment habitats, offering new insights for ecosystem monitoring and microbial-based water quality management, on a global scale.