-

'The reproductive performance of sows, a critical economic determinant in livestock production, mainly depends on ovarian physiological function and follicular development[1]. Granulosa cells (GCs) are important somatic cells in the ovaries[2]. The primary roles of GCs are impacting follicular development and taking part in the secretion of steroid hormones[3,4]. GC apoptosis has been recognized as the primary cause of follicular atresia[5,6]. In addition, GCs can also secrete steroid hormones such as estrogen (E2) and progesterone (P4) to regulate follicular maturation[7]. E2 can work together with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to enhance GCs' proliferation through autocrine signaling[8]. E2 also increases the synthesis of luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) and aromatase, thereby inhibiting GC apoptosis and promoting follicular development[9,10]. In contrast, P4 plays an important role in maintaining pregnancy, promoting full development of the genital tract, inhibiting estrus and ovulation, and decreasing cell apoptosis[11−15]. Steroid hormones secreted by GCs play important roles in determining follicular fate, positioning their functional analysis as a strategic approach to enhance female reproductive efficiency.

Nitric oxide (NO), a gaseous signaling molecule synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS), serves as a critical regulator of physiological and pathological processes through redox-dependent mechanisms[16−18]. NOS is expressed in mammalian ovaries[19,20]. Within this physiological context, NO regulates key reproductive processes, including hormone regulation[21−23], pregnancy maintenance, and labor[24]. Previous studies have revealed a concentration-dependent duality in NO's bioactivity[25]. At physiological levels, NO inhibits apoptosis and promotes follicular development[26,27], while supraphysiological concentrations trigger oocyte apoptosis and follicular atresia. However, the relevant mechanisms need to be further studied.

In the organism, high concentrations of NO may react with the superoxide anion (O2−) to produce the peroxynitrite anion (OONO−)[28,29]. Compared with NO, ONOO− demonstrates strong oxidative capacity, generating additional reactive species and exerting extensive tissue-damaging effects[30], These include promoting lipid peroxidation and nitration[31], inactivating enzymes[32], and impairing mitochondrial respiration via protein oxidation and nitration. In particular, oxidative stress reduces the synthesis of FSH-maintained GC steroid hormones, primarily E2, a critical ovarian response biomarker[33]. In addition, OONO− is considered to very readily mediate protein tyrosine nitration (PTN) in cells. PTN is a stable post-translational modification of proteins, which plays an important role in the occurrence of many diseases. This cellular toxicity primarily arises from ONOO−'s ability to nitrate tyrosine residues. Franco et al. found, in PC12 cells, that ONOO−-induced Hsp90 tyrosine nitration disrupts cellular functions: nitration at tyrosine 56 triggers apoptosis, while a modification at Residue 33 compromises mitochondrial activity[34,35]. The resulting formation of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) serves as a reliable biomarker for endogenous protein nitration.

Previous studies have demonstrated that OONO− induces DNA damage in GCs and inhibits DNA repair through MMP-2/MMP-9-mediated impairment of PARP1 activity, ultimately resulting in GC apoptosis[36]. However, the potential impact of accumulating ONOO− on GC's functions and steroid hormone secretion remains uncharacterized.

Therefore, this study employed the OONO− donor SIN-1 to treat GCs, utilizing RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to investigate OONO−-mediated alterations in GCs' physiological functions. The effects of OONO− on GCs' E2 secretion were assessed through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), combined with molecular analyses of the expression of E2 synthesis-associated proteins and genes. Furthermore, the NO scavenger cPTIO was applied to validate the functional role of OONO−.

-

Ovaries from non-pregnant sows were obtained from a slaughterhouse (Changzhou Erhualian Pig Production Cooperation, Jiangsu, China). The ovaries were preserved in sterile saline (0.9%) containing 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) within vacuum-sealed flasks and transported to the laboratory within 2 h. Follicles were morphologically classified under a surgical dissecting microscope (SZ40; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) into three categories according to established criteria: healthy follicles (H), early atretic follicles (EA), and progressively atretic follicles (PA)[37]. Briefly, healthy follicles have a pinkish-red coloration, dense vascularization, and clear follicular fluid, while EA follicles display reduced or absent surface vascularization with mildly turbid follicular fluid. The follicles of the PA group present a grayish-white appearance, no vascularization, and opaque follicular fluid.

Isolation, culture, and identification of porcine ovarian granulosa cells

-

Ovaries were transported to the laboratory to isolate GCs. Ovaries were rinsed with saline, a 75% ethanol solution, and saline containing 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S), all of which were rinsed two or three times to eliminate residual blood. Follicular fluid was aspirated using sterile syringes and transferred to enzyme-free centrifuge tubes. After centrifugation (1,500 g, 5 min), the supernatants were discarded, and the GCs were washed two or three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% P/S. Cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DEME/F) (WISENT, 319-085-CL) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega, FB-21-311892) and a 1% P/S solution. They were maintained in an incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Non-adherent cells were removed through replacement of the medium at 24 h. Immunofluorescence staining was performed according to Yousefi et al.[38]. Stained specimens were analyzed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 40C/CFL, Zeiss) after mounting.

When the GCs' confluency in a six-well plate reached 80% to 90% (about 5 × 105 cells/well), 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-200339) or carboxy-PTIO (cPTIO) (Beyotime Biotechnology, S1546) was added to the medium containing 5% serum for cell treatment. The treatment concentration of SIN-1 was determined by a CCK-8 experiment. cPTIO, a NO scavenger, was added to the medium at a concentration of 100 μM to treat GCs half an hour before the SIN-1 treatment. After treatment, the GCs were washed with PBS containing 1% P/S and collected for further experimental analysis.

CCK-8 assay

-

A CCK-8 assay was used to detect the cell viability of GCs subjected to different treatments. The assay was carried out in strict accordance with the instructions of the CCK-8 kit (Apexbio, K1018), and the specific steps were as follows: GCs were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured to 70%−80% confluency prior to treatment with SIN-1 at increasing concentrations (including 0, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1,000 μM). Treated cells were incubated for 24 h under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Following treatment, the culture medium was replaced with a freshly prepared CCK-8 working solution (10:1 ratio of culture medium to CCK-8 reagent; 100 μL per well). After a 2-h incubation period, absorbance measurements were conducted at 450 nm.

ELISA

-

Estrogen concentrations in the cell culture supernatants and follicular fluid were quantified using an ELISA kit (Nanjing Xin Fan Biology, XFP40451) following the manufacturer's protocol. The assay demonstrated a detection sensitivity of 1.83 pg/mL for E2, with the intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation maintained below 10% and 15%, respectively, ensuring analytical precision. The specific assay steps followed the ELISA kit's instructions.

Western blot analysis

-

Total protein was extracted using a radioimmunoprecipitation analysis (RIPA) lysis buffer (Apexbio, K1020). Protein concentrations were quantified with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Boster Bio, AR1189).

Protein lysates were normalized to equal concentrations by adjusting the volumes of the RIPA buffer and the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (Ncmbio, Suzhou, China), followed by denaturation at 100 °C for 10 min. Denatured samples were separated on 4%−20% Sure polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels (Genscript, Nanjing, China) and electrophoretically transferred to 45-μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1.5 h at ambient temperature prior to overnight incubation with primary antibodies (Table 1) at 4 °C. After three 5-min Tris-buffered saline–Tween (TBST) washes, the membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three additional TBST washes. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Biosharp, Hefei, China), and imaged with a ultrasensitive chemiluminescence gel imaging system (Bio-Rad). Band intensity quantification was performed using ImageJ.

Table 1. Primary antibodies.

Primary antibody Purpose Dilution Source Cat No. Cleaved Caspase-3 pAb WB 1:1,000 Cell Signaling #9661L β-actin pAb WB 1:5,000 Affinity #AF7018 CYP19A1 pAb WB 1:1,000 CST #14528 GAPDH pAb WB 1:10,000 Affinity #AF7021 FSHR pAb WB 1:1,000 Abclone A3172 CYP11A1 pAb WB 1:1,000 Santa A1713 HSD3β pAb WB 1:1,000 Santa sc-515120 STAR pAb WB 1:1,000 Santa sc-166821 3-Nitrotyrosine mAb WB 1:1,000 Abcam ab110282 RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

-

Total RNA was isolated from treated GCs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA purity and concentration were quantified using a nucleic acid protein assay on an ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Qualified RNA samples underwent reverse transcription using a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, R233-01). Synthesized cDNA was stored at −20 °C.

RNA-seq and bioinformatic analysis

-

After extraction of total RNA, poly(A) mRNA isolation was performed using Oligo (dT) beads. mRNA fragmentation was achieved through divalent cation-mediated cleavage at a high temperature. First-strand cDNA and second-strand cDNA were synthesized by reverse transcription using random primers. The purified double-stranded cDNA was then processed by repairing both ends and adding a dA-tailing in one reaction, followed by a T-A ligation to add adaptors to both ends. Adapter ligation DNA size selection was then performed using DNA Clean Beads. Each sample was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with P5 and P7 primers, and the PCR products were validated.

The differently indexed libraries were then multiplexed and loaded on an Illumina HiSeq/Illumina Novaseq/MGI2000 instrument for sequencing using a 2 × 150 paired-end (PE) configuration. Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2, identifying transcripts with an adjusted p-value of < 0.05, a false discovery rate (FDR) of ≤ 0.05, and an absolute log2 fold change (FC) of > 1 as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). To determine the biological pathways and functions of the DEGs, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed on the DEGs. The GO annotation tems were acquired through Goseq (v1.34.1), followed by implementation of GO functional enrichment analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

-

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed using synthesized cDNA templates with a kit (Vazyme, Q111-02/03). The system of the reaction mixture (total volume = 20 μL) is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Real-time qualitative PCR system.

Components Volume (μL) 2 × ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix 10 Forward primer 0.4 Reverse primer 0.4 50× ROX reference dye 0.4 cDNA template 2 Nuclease-free water 6.8 Quantitative PCRs were performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. Melt curve analysis was conducted through sequential incubations at 95 °C (15 s), 60 °C (60 s), and 95 °C (15 s). Information on the primers used in this study is shown in Table 3. The target genes' expression levels were normalized to GAPDH as an endogenous control and quantified via the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Table 3. Primer sequences used for real-time qualitative PCR.

Gene Sequence (5'–3') Accession number Forward primer Reverse primer CYP11A1 TCGCCTTTGAGTCCATCACC TCCGTCTCAGGTCCCAGTAG NM_214427.1 CYP19A1 GGGTCACAACAAGACAGGACT ACCTGGTATTGAAGATGTGTTTTT NM_214429.1 3βHSD ACAATCTTACAGGGCCACCC TGGCCTTTGACCCAGGTTAG XM_021088745.1 FSHR CGCGGTTGAACTGAGGTTTG GCAGGTTGTTGGCCTTTTCA XM_021085884.1 GAPDH GGCCGCACCACTGGCATTGTCAT AGGTCCAGACGCAGGATGGCG XM_003126531.5 Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were repeated at least three times (n ≥ 3). Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) with the data presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t-test were used to test the significance of the differences. All of the statistical analyses were verified by Tukey's post hoc test. Significance thresholds were established at p < 0.05 (significant) and p < 0.01 (extremely significant). Data visualization was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Prism 9.Ink, Boston, MA, USA).

-

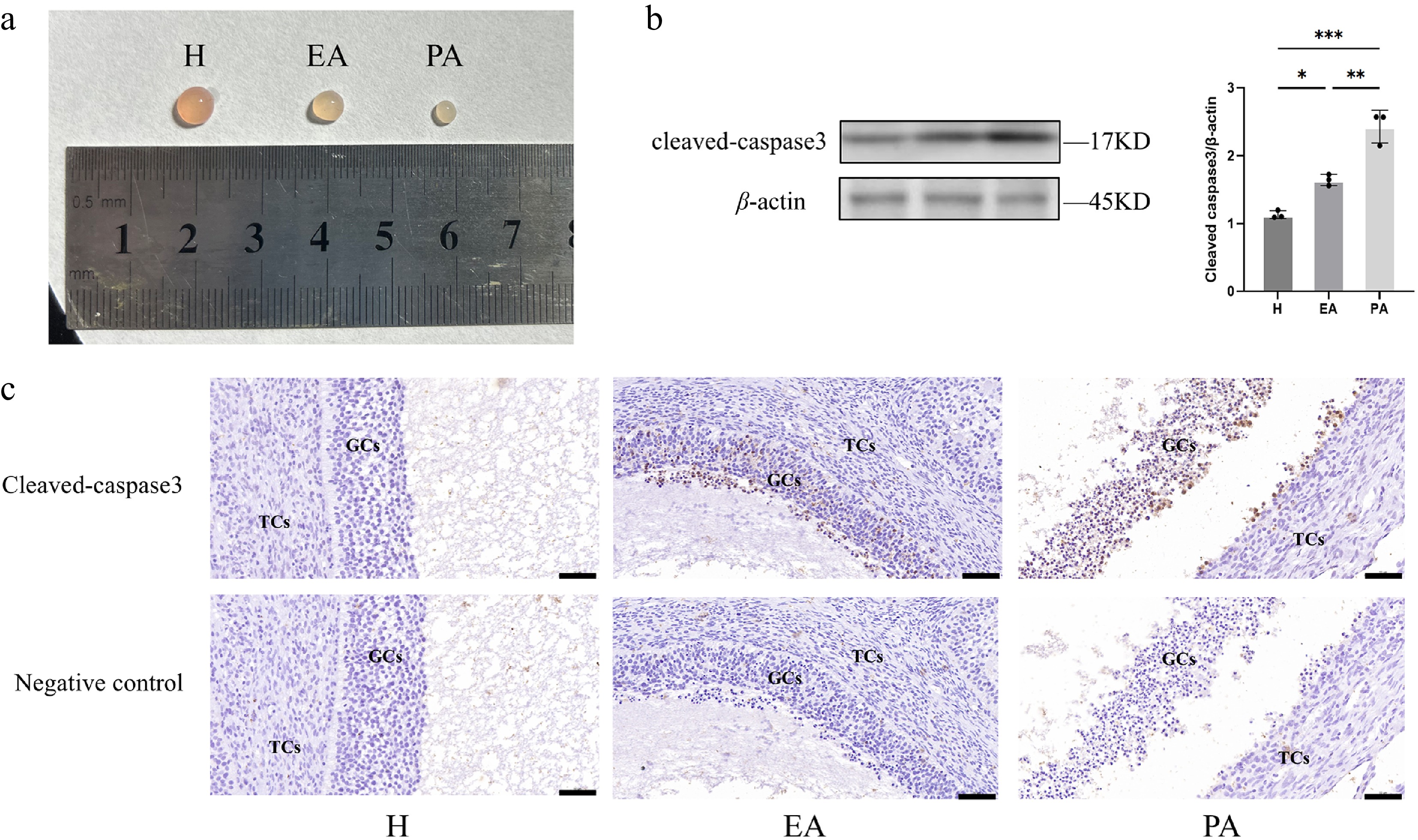

Follicles were classified into three distinct atresia stages, namely healthy (H), early atretic (EA), and progressively atretic (PA), according to established morphological criteria (Fig. 1a)[37]. Apoptotic activity in the GCs across follicular categories was assessed through Cleaved Caspase-3 detection via immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1b, the expression of Cleaved Caspase-3 was significantly increased in EA and PA follicles compared with the H group. In addition, the IHC results showed that the expression of Cleaved Caspase-3 in paraffin sections increased with follicular atresia (Fig. 1c). All these results suggested that GC apoptosis was associated with follicular atresia, and demonstrated the reliability of our classification for further experiments.

Figure 1.

Follicular morphometric classification and dynamics of GC apoptosis in porcine ovarian follicles. (a) Morphological characteristics distinguishing different types of follicles. (b) Western blot quantification of Cleaved Caspase-3 expression in GC populations. (c) Immunohistochemical staining of Cleaved Caspase-3 in paraffin-embedded follicular sections. H, healthy follicles; EA, early atretic follicles; PA, progressively atretic follicles. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 50 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The estrogen secretion level of granulosa cells decreased during follicular atresia

-

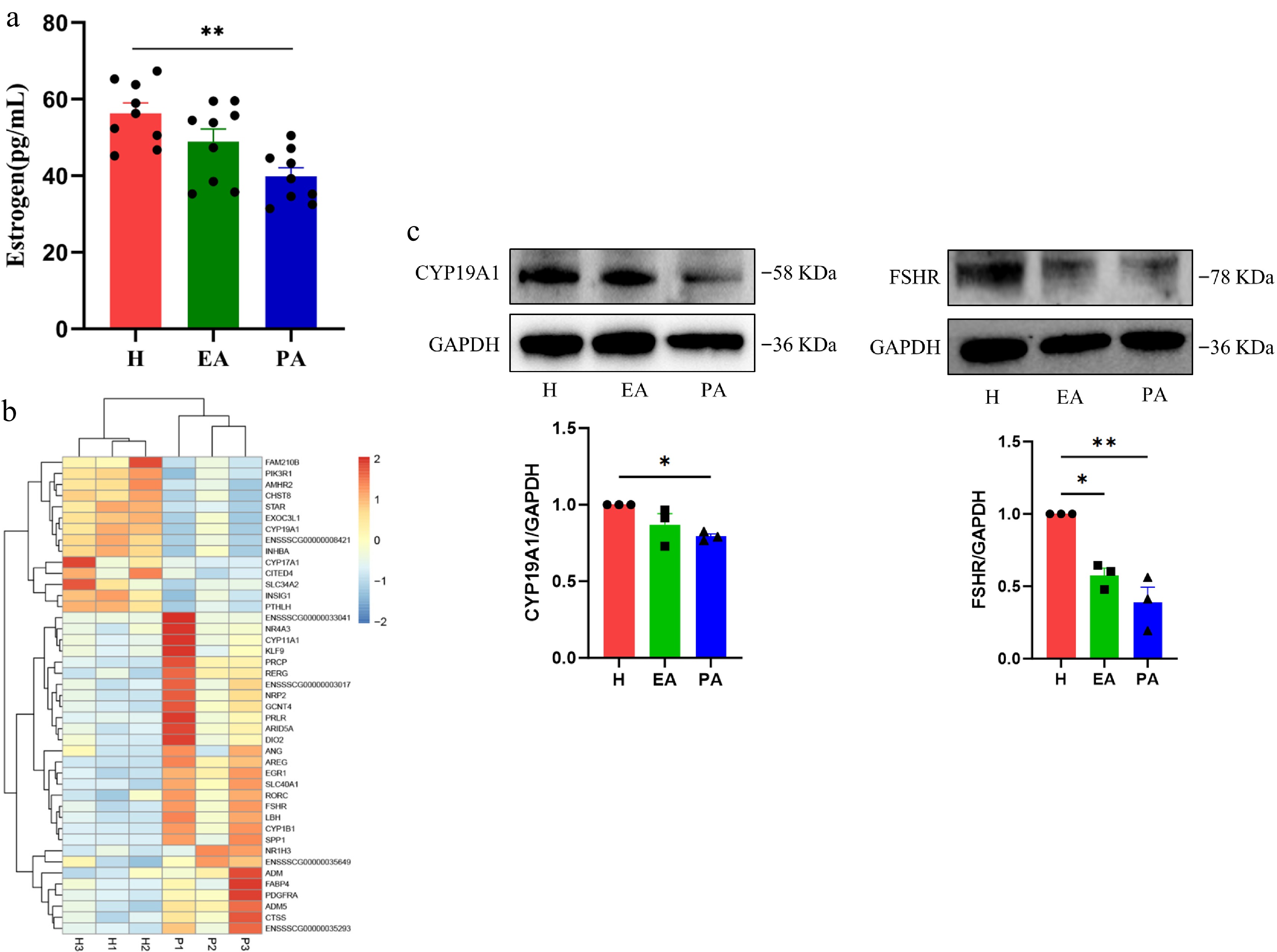

E2 secretion dynamics during follicular atresia were quantified through follicular fluid analysis using ELISA. PA follicles exhibited a reduction in E2 concentration compared with H follicles, while EA follicles showed an intermediate decrease that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2a). The RNA-seq data were then used to screen for GO functions containing the terms 'estrogen', 'steroid', and 'hormone', and the genes with significant differences (p < 0.05) were screened (Fig. 2b). The results showed that in PA, the expression levels of estrogen synthesis-related genes such as CYP19A1 and STAR were significantly decreased. The expression levels of steroid hormone secretion-related proteins in different classes of follicles were examined further. With follicular atresia, the expression of CYP19A1 and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) proteins decreased significantly (Fig. 2c). These results indicated that GCs diminished the capacity for E2 synthesis during follicular degeneration.

Figure 2.

Estrogen secretion levels in different types of follicles and the expression of hormone secretion-related genes and proteins in granulosa cells. (a) ELISA for estrogen in the follicular fluid of H, EA, and PA. (b) Heatmap of hormone secretion-related genes in granulosa cells of H and PA. Blue, downregulated genes; red, upregulated genes. (c) Western blotting analysis of hormone secretion-related proteins in granulosa cells from H, EA, and PA. H, healthy follicles; EA, early atretic follicles; PA, progressively atretic follicles. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Isolation and characterization of porcine ovarian GCs

-

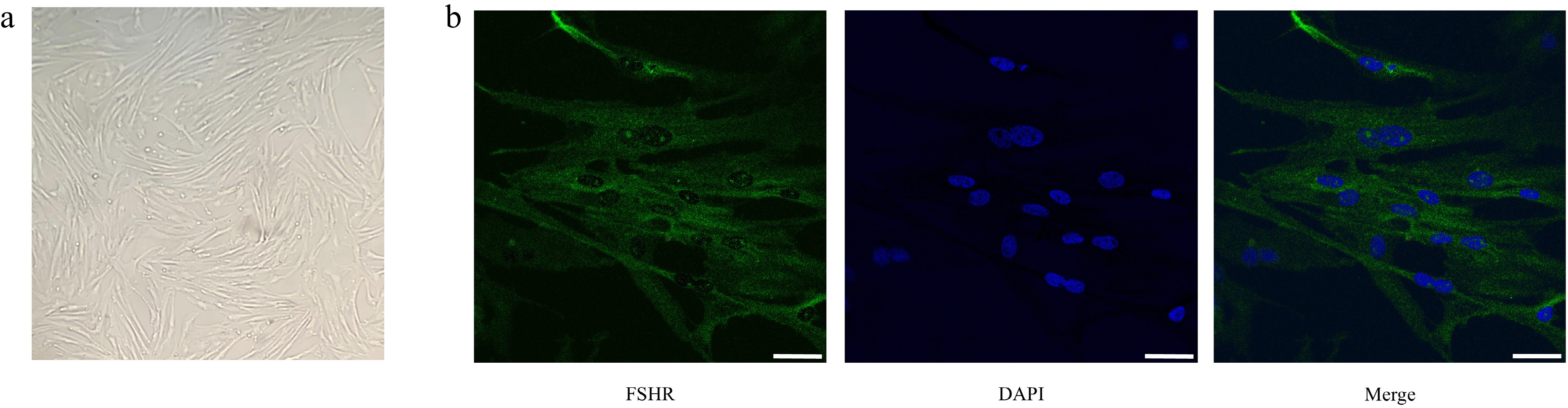

GCs were isolated from porcine ovaries and cultured for subsequent experiments. Inverted microscopy revealed a characteristic GC morphology, displaying uniform spindle-shaped cellular structures (Fig. 3a). To confirm cellular identity, immunofluorescence staining was performed for FSHR, a GC-specific marker. As shown in Fig. 3b, FSHR-specific green fluorescence co-localized with nuclear 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (blue). More than 90% of the cells in the random field of view were positive for FSHR expression, verifying successful isolation of high-purity GCs suitable for subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Morphological observation and purity identification of porcine follicular granulosa cells. (a) Observation of granulosa cells' morphology by inverted microscopy. (b) Immunofluorescence staining of FSHR. From left to right: FSHR fluorescence staining (green); nuclear DAPI staining (blue); merged image. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Concentration-dependent effects of OONO− on GCs' function

-

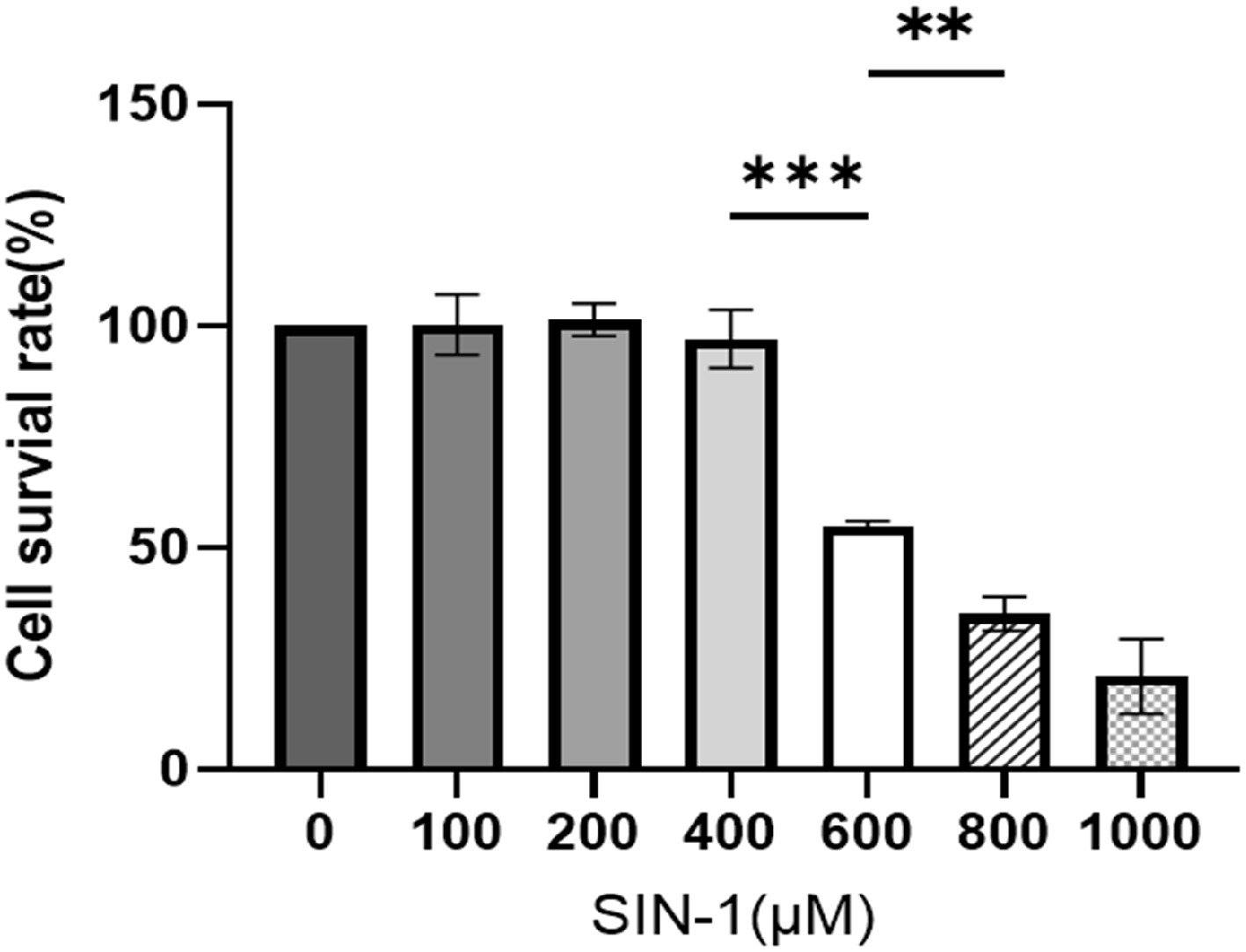

To evaluate OONO−-mediated effects on GCs' functionality, GCs were treated with SIN-1 (an OONO− donor). Previous experimental data revealed concentration-dependent decreases in GCs' viability following 24 h of exposure to SIN-1[36]. CCK-8 assays confirmed this trend (Fig. 4): 600 μM SIN-1 significantly reduced GCs' viability, while treatment with 800 μM decreased viability by over 50%. Three concentration-based experimental groups were selected for RNA-seq: (1) 0 μM (control), (2) 400 μM (pre-significance exposure level), and (3) 800 μM (> 50% viability loss). DEGs were screened according to the criteria of |log2FC| > 1, p < 0.05 and FDR ≤ 0.05, and subsequent GO analysis and KEGG analyses were performed.

Figure 4.

Cell survival rate of SIN-1-treated granulosa cells. Viability assessment via a CCK-8 assay following 24 h of exposure to SIN-1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

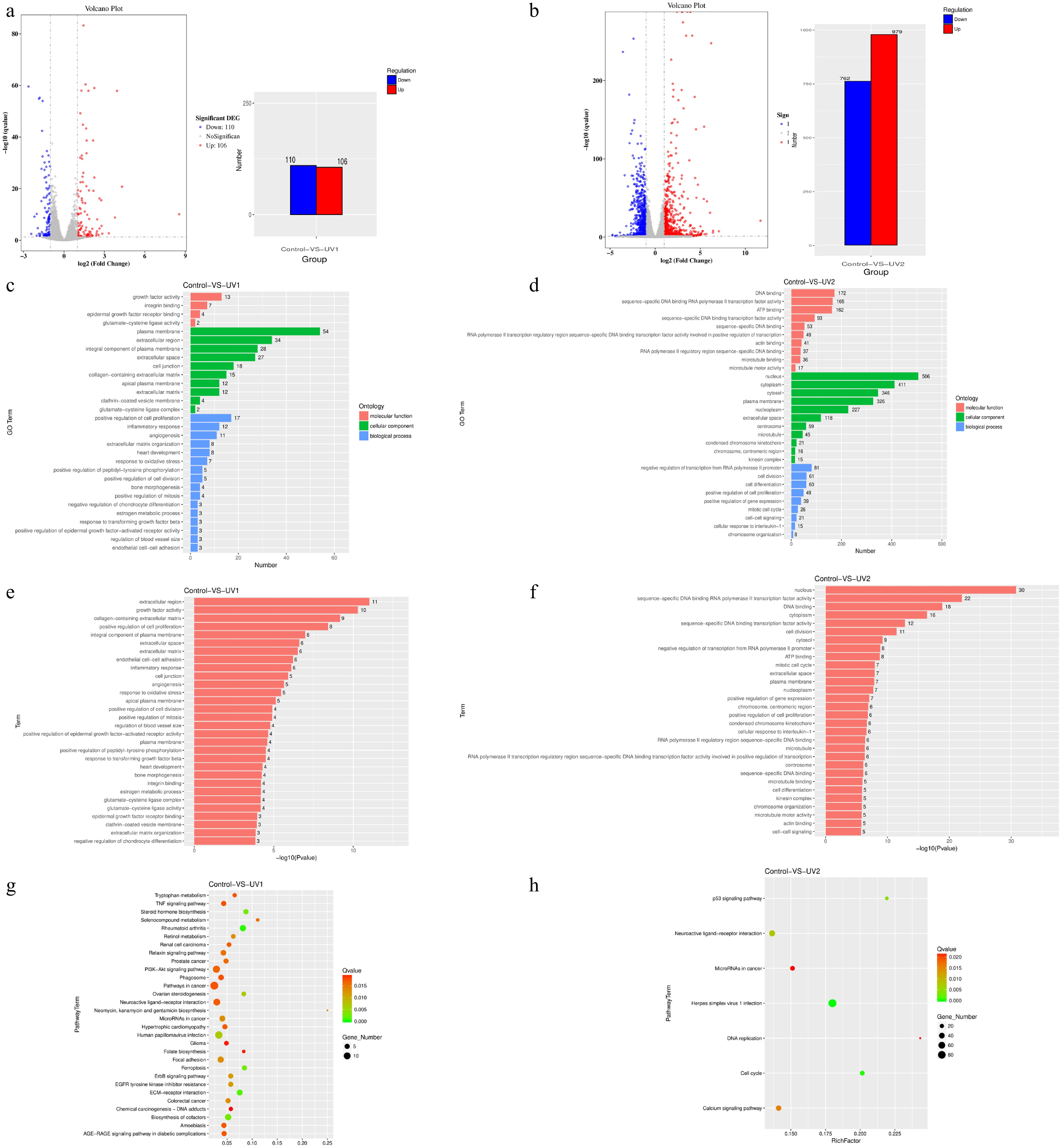

The volcano plot showed that a total of 110 genes were significantly downregulated (blue) and 106 genes were significantly upregulated (red) in the 400 μM SIN-1-treated group (Fig. 5a). Compared with the control group, 762 genes were significantly downregulated (blue) and 979 genes were significantly upregulated (red) in the 800 μM SIN-1-treated group (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Number of differentially expressed genes, and GO enrichment and KEGG enrichment of differentially expressed genes in each group after SIN-1 treatment. (a) Volcano plot and bar graph of the DEGs of the 400 μM SIN-1-treated and control groups. The bar graph shows that of all 216 DEGs, 110 of them were downregulated and 106 were upregulated. (b) Volcano plot and bar graph of the DEGs of the 800 μM SIN-1-treated and control groups. The bar graph shows that of all 1741 DEGs, 762 of them were downregulated and 979 were upregulated. For the visualization of the DEGs in the volcano plots. The horizontal coordinate is the fold change in expression in the control and SIN-1-treated groups, and the vertical coordinate is the statistical significance of the change in expression. Different colors indicate different classifications: blue (downregulation), red (upregulation), and gray (no significant difference). (c, d) GO enrichment analysis of DEGs in the control, 400 μM SIN-1-treated, and 800 μM SIN-1-treated groups. The vertical coordinate is the enriched GO term, and the horizontal coordinate is the number of DEGs in that term. Different colors are used to distinguish different enriched terms: blue (biological processes), green (cellular components), and red (molecular functions). (e, f) Statistical significance profiles of GO terms. The vertical coordinate is the enriched GO term and the horizontal coordinate is the p-value. (g, h) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the control, 400 μM SIN-1-treated, and 800 μM SIN-1-treated groups. The vertical coordinate indicates the name of the pathway, the horizontal coordinate indicates the enrichment factor, the dot size correlates with the quantity of DEGs, the color gradient indicates the q-value significance. Control, 0 μM SIN-1-treated group; UV1, 400 μM SIN-1-treated group; UV2, 800 μM SIN-1-treated group.

Functional annotation analysis prioritized the 30 most statistically enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways, with complete inclusion of all terms when the totals fell below 30. Comparative GO analysis of the DEGs between the control and SIN-1-treated groups revealed concentration-dependent functional divergence. Molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components were the three most gene-enriched terms. The 400 μM SIN-1 group exhibited predominant enrichment in extracellular regions, positive regulation of cell proliferation, and estrogen metabolic processes (Fig. 5c). In contrast, the 800 μM treatment group showed RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding and sequence-specific DNA binding RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity as the dominant functional categories (Fig. 5d). Figure 5e, f displays the p-values of the abovementioned GO-enriched terms.

The analysis of the significantly enriched pathways could then be used to understand the main metabolic pathways and signaling pathways associated with the DEGs. In the 400 μM SIN-1 treatment group, DEGs were predominantly enriched in the extracellular matrix (ECM)–receptor interaction, steroid hormone biosynthesis, ferroptosis, and ovarian steroidogenesis pathways (Fig. 5g). In addition, as shown in Fig. 5h, the 800 μM SIN-1 group exhibited predominant enrichment in the cell cycle, the P53 signaling pathway, and the calcium signaling pathway.

OONO− affected estrogen secretion in GCs

-

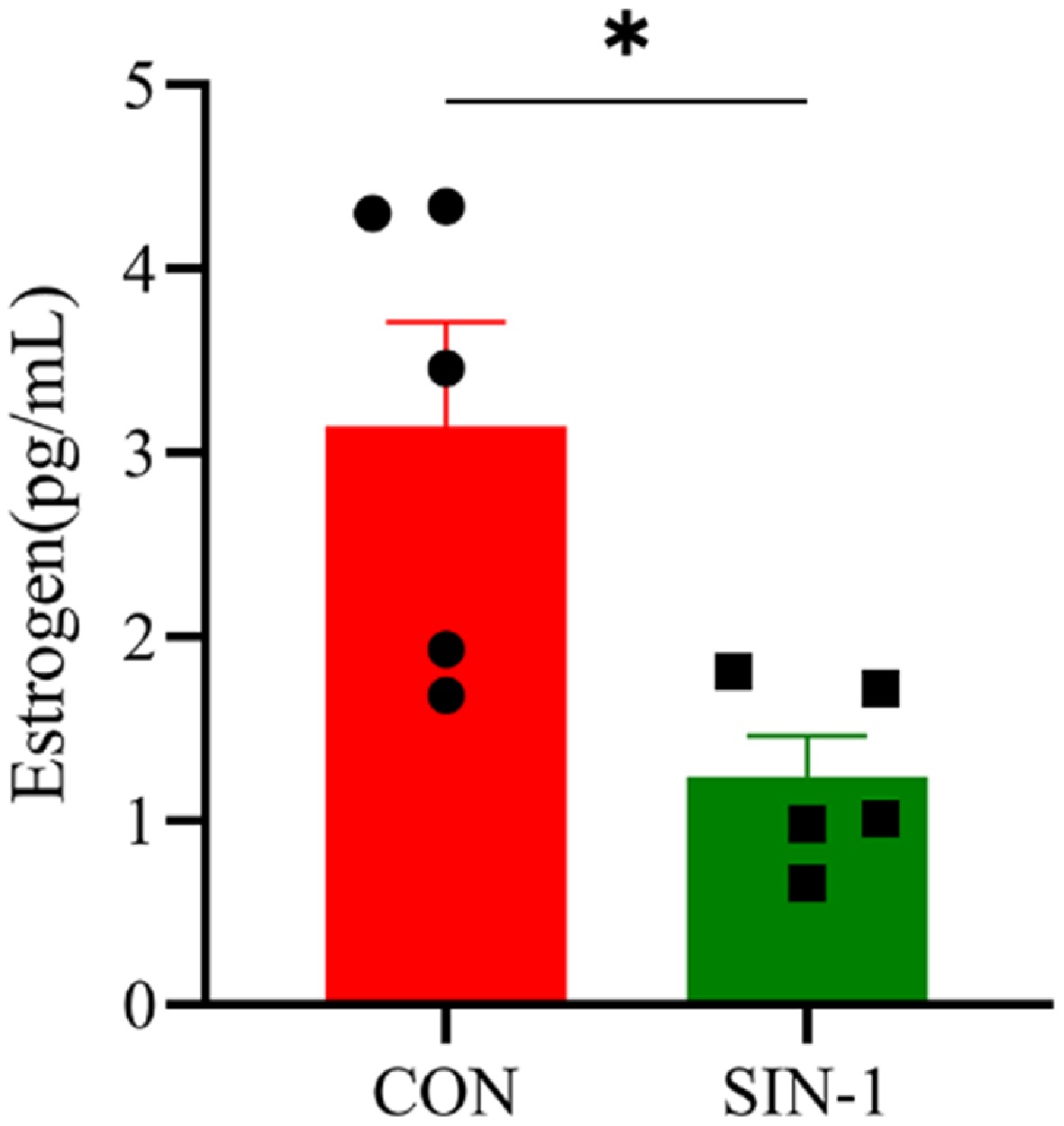

To investigate the effects of OONO− on GCs' steroidogenesis, GCs were treated with 400 μM SIN-1 in thesubsequent experiments. ELISA quantification of the supernatants demonstrated a reduction in E2 secretion in SIN-1-treated GCs compared with the untreated controls (Fig. 6). This suppression occurred despite maintaining cell viability, confirming direct inhibition of steroidogenic capacity rather than secondary cytotoxic effects.

Figure 6.

Hormone secretion levels in SIN-1-treated granulosa cells. Estrogen levels in the cell supernatants tested with an ELISA kit. CON, 0 μM SIN-1-treated group; SIN-1, 400 μM SIN-1 treatment group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

OONO− inhibited steroidogenic gene and protein expression in GCs

-

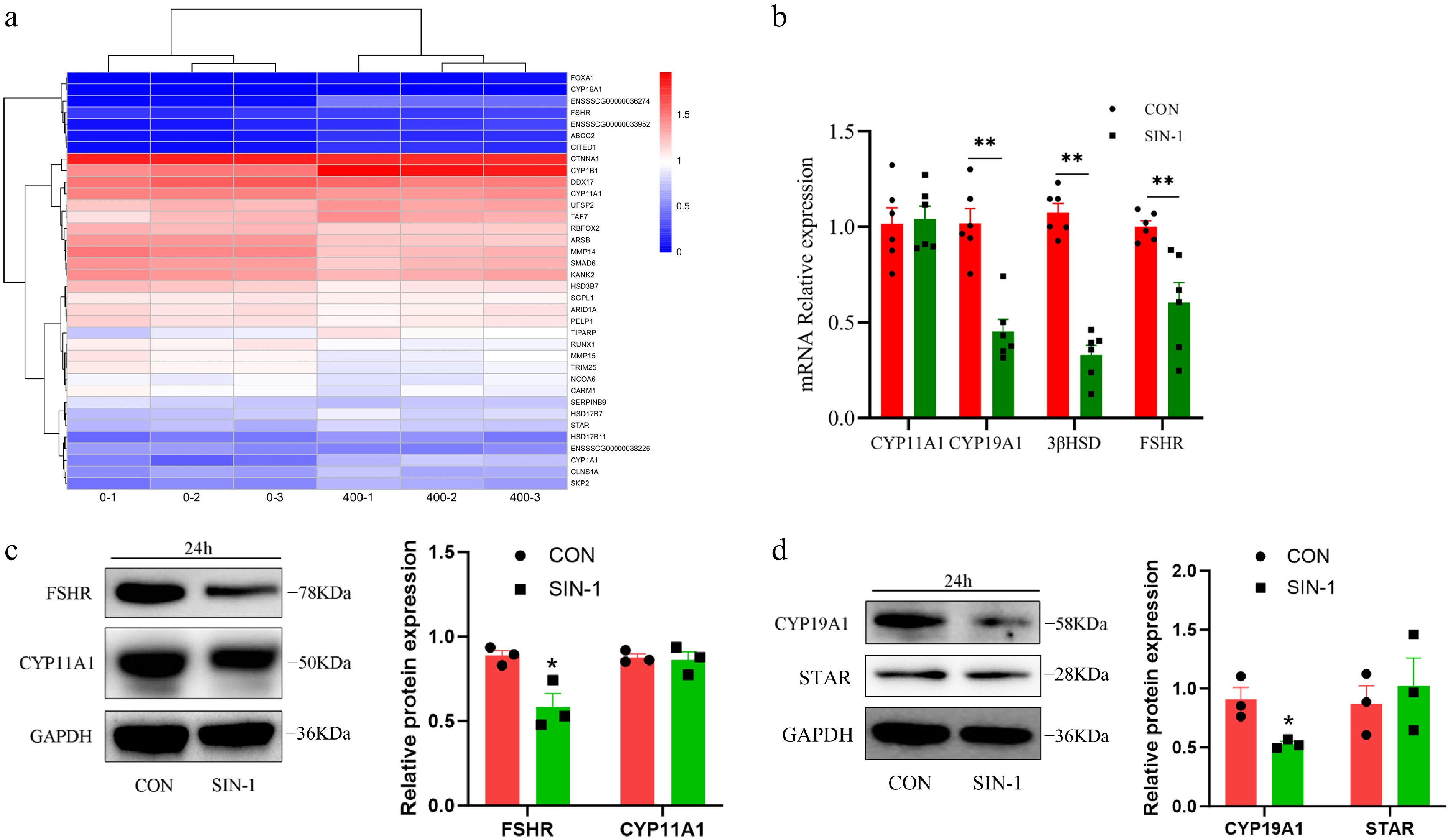

To further investigate the effect of OONO− on E2 secretion in GCs, the RNA-seq data were utilized to screen GO functions containing the terms 'estrogen', 'steroid', and 'hormone'. Significantly different (p < 0.05) genes were screened and a heatmap was made (Fig. 7a). Key steroidogenic genes including CYP11A1 and 3β-HSD were significantly suppressed. Targeted qPCR validation confirmed reductions in the expression of CYP19A1 and 3β-HSD following SIN-1 treatment (Fig. 7b). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the expression of CYP19A1, an E2 synthesis-related protein, was significantly decreased in the SIN-1-treated group, as well as FSHR (Fig. 7c, d). These results suggest that OONO− affected E2 synthesis-related genes and proteins in GCs, leading to a decrease in the E2 secretion capacity of GCs.

Figure 7.

Expression of hormone secretion-related genes and proteins in granulosa cells. (a) Heatmap of hormone secretion-related DEGs; 0-1, 0-2, and 0-3 are the control groups, whereas 400-1, 400-2, and 400-3 are the 400 μM SIN-1 treatment groups. Blue, downregulated genes; red, upregulated genes. (b) RT-PCR analysis of the relative expression of the mRNA of hormone secretion-related genes in granulosa cells. (c, d) Western blot analysis of hormone secretion-related proteins in granulosa cells. CON, control group; SIN-1, 400 μM SIN-1-treated group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

The NO scavenger alleviated the effects of OONO− on steroid hormone synthesis

-

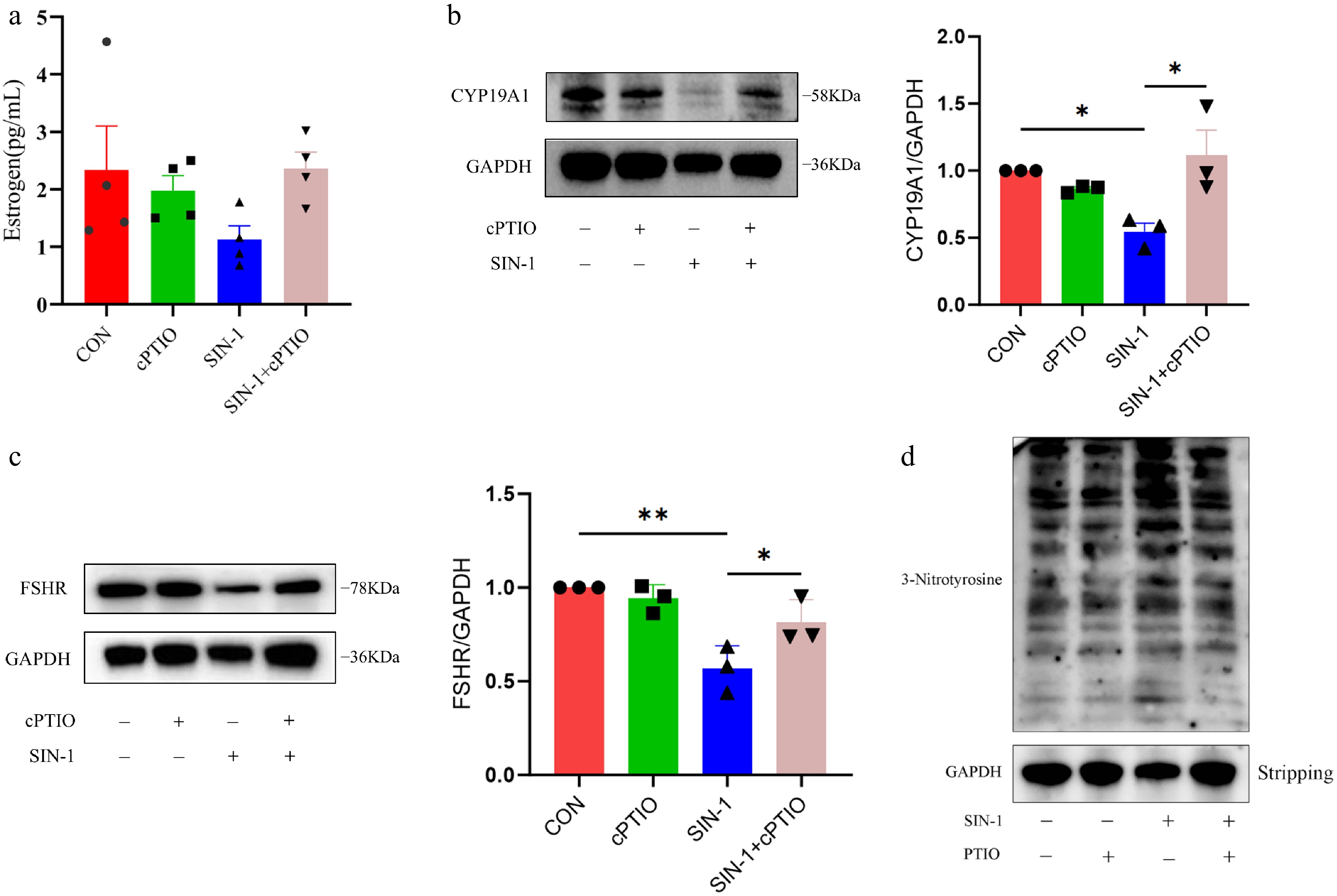

To confirm the specificity of ONOO− in disrupting GC steroidogenesis, cells were co-treated with SIN-1 (400 μM) and the NO scavenger cPTIO (100 μM). ELISA analysis demonstrated partial rescue of E2 secretion in the cPTIO+SIN-1 groups compared with SIN-1 alone (Fig. 8a). Western blot quantification demonstrated that cPTIO significantly alleviated SIN-1-induced suppression of CYP19A1 and FSHR expression (Fig. 8, c). Given the nitrating activity of OONO−, the tyrosine nitration levels in GCs were further evaluated. The results showed that the tyrosine nitration level of GCs was significantly increased after SIN-1 treatment, but the addition of cPITO inhibited this change (Fig. 8d). This further verified that the OONO− produced by SIN-1 inhibits the E2 secretion capacity of GCs.

Figure 8.

Levels of E2 secretion and hormone-related protein expression and overall nitroxylation in granulosa cells. (a) ELISA for estrogen levels in cell supernatants. (b, c) Western blot analysis of hormone secretion-related proteins in granulosa cells. (d) Western blot analysis of total nitroxylation in granulosa cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

-

Synthesis of E2 by ovarian GCs serves as a critical determinant of follicular competence and female reproductive performance. While prior work established ONOO− as a mediator of GC apoptosis, this study elucidates its novel role in disrupting steroidogenic function.

During follicular atresia, reduced E2 secretion by GCs was observed. It has also been previously shown that estrogen is essential for proper follicle development[39,40], and low estrogen levels may indicate follicular atresia[41]. This study demonstrated that follicular atresia was associated with significant reductions in both the protein and gene expression levels of E2 synthesis-related markers (CYP19A1, STAR, and 3β-HSD) in GCs. These changes are temporally correlated with the previously reported elevation of OONO− levels in GCs during follicular atresia[36], suggesting the potential regulatory role of OONO− in suppressing GC-mediated E2 secretion. To validate this hypothesis, exogenous OONO− administration was experimentally demonstrated to exert multifaceted inhibitory effects on E2 biosynthesis in GCs. Notably, NO acts as a precursor substance of OONO−, which may also be a possible mechanism by which NO affects the E2 secretion of GCs. It has also been previously shown that excessive NO inhibits the expression of the aromatase protein family[42−44].

Steroid hormones are mainly derived from cholesterol. Prior to hormone synthesis, cholesterol is transferred from the outside to the inside of the mitochondrion by StAR[45], and then the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone is mediated by CYP11A1[46,47], which is then acted upon by 3β-HSD to synthesize P4[48]. In addition to its own physiological functions, P4 is also a precursor for the synthesis of E2. CYP19A1 is a key gene in the process of synthesizing E2. Decreased expression of CYP19A1 greatly limits E2 synthesis in GCs[49]. This study demonstrated that OONO− significantly downregulates the expression of 3β-HSD and CYP19A1, which are key enzymes in E2 synthesis, thereby inhibiting E2 secretion in porcine ovarian GCs.

FSH is a glycoprotein hormone whose primary function in females is to promote follicular development and maturation, and acts synergically with luteinizing hormone (LH) to induce E2 secretion and ovulation in mature follicles. FSH acts primarily on GCs. FSHR in GCs is essential for follicular development and E2 secretion[50], and inhibition of FSHR expression directly affects the biological effects of FSH[51]. Previous studies have reported that FSH acts on FSHR in GCs, which, in turn, modulates the expression of CYP19A1-produced aromatase and stimulates the release of E2[52−54]. Zhou et al. found that exogenous peroxynitrite may cause tyrosine nitration and proteasome-mediated degradation of FSHR in KGN cells[55]. In this study, the data proved that exogenous addition of SIN-1 decreased the expression level of FSHR protein in GCs, which may be the result of OONO− affecting the expression of FSHR. OONO− inhibits FSHR expression, which may affect the production of aromatase by CYP19A1, and thus affect E2 secretion. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that SIN-1 elevated total nitration levels in GCs, while its potential induction of FSHR nitration awaits further experimental verification.

In recent years, high-throughput sequencing has been used for bioinformatic analysis in a variety of animals. To further investigate the effects of OONO− on GCs, RNA-seq was used to detect transcriptional differences between GCs in the control, 400 and 800 μM SIN-1-treated groups. GO function and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses allowed the identification of functional or metabolic pathways enriched by the DEGs, which led to speculation about the possible effects of OONO− on GCs. The analytical results revealed that the GO enrichment terms for DEGs under both the 400 and 800 μM treatments included positive regulation of cell proliferation, extracellular space, and the plasma membrane. This suggests that exposure to OONO− at both low and high concentrations alters the expression of GC genes related to proliferation, microenvironment modulation, and intercellular communication, ultimately impairing cellular functionality. In ovarian tissues, the proliferation of GCs is crucial for ovarian function, and impaired GC proliferation may cause follicular dysfunction and, in severe cases, even infertility in females[56]. The extracellular space and plasma membrane function mainly affect intercellular communication as well as the cellular microenvironment. The interactions between oocytes and GCs are very critical during follicular development, as the GCs will create a suitable microenvironment for oocyte development through gap junctions and provide the energy and nutrients required during oocyte development, and oocytes will, in turn, affect the function and differentiation of GCs. It has been found that peroxynitrite inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblasts[57]. NO, as a precursor substance of OONO−, is an important signaling molecule in living organisms and plays an important role in intercellular communication. Lillo et al. found that NO causes S-nitrosylation of the cardiac gap junction protein Connexin-43 (Cx43), which leads to arrhythmias in mice[58]. NO also has the potential to specifically affect Connexin-37 (Cx37), which affects gap junction intercellular communication in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)[59]. Studies have demonstrated that compromised GC functions—including impaired proliferation and dysregulated intercellular signaling—disrupt E2 secretion. This functional impairment may represent a mechanism through which OONO− suppresses E2 biosynthesis.

Notably, DEGs in the 800 μM SIN-1 treatment group exhibited significant enrichment in transcription-related pathways (including RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding and sequence-specific DNA binding RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity, etc.) compared with the 400 μM group. This suggests that excessive OONO− concentrations may shift cellular regulatory mechanisms from basic metabolic pathways to profound transcriptional-level interventions, potentially through disrupting transcription factor activity to orchestrate the overall regulation of gene expression, which could lead to aberrant epigenetic modifications.

The results of this study demonstrate that DEGs under the high-concentration SIN-1 treatment were primarily enriched in nucleus-, DNA-, and RNA-related functions and pathways compared with the low-concentration treatment, suggesting that higher SIN-1 concentrations may predominantly affect the regulation of genetic material. However, it remains unclear whether this phenomenon arises from cell-autonomous dysregulation of gene expression induced by cytotoxic effects or represents the specific actions of SIN-1 itself. This critical distinction will be systematically investigated in subsequent research.

-

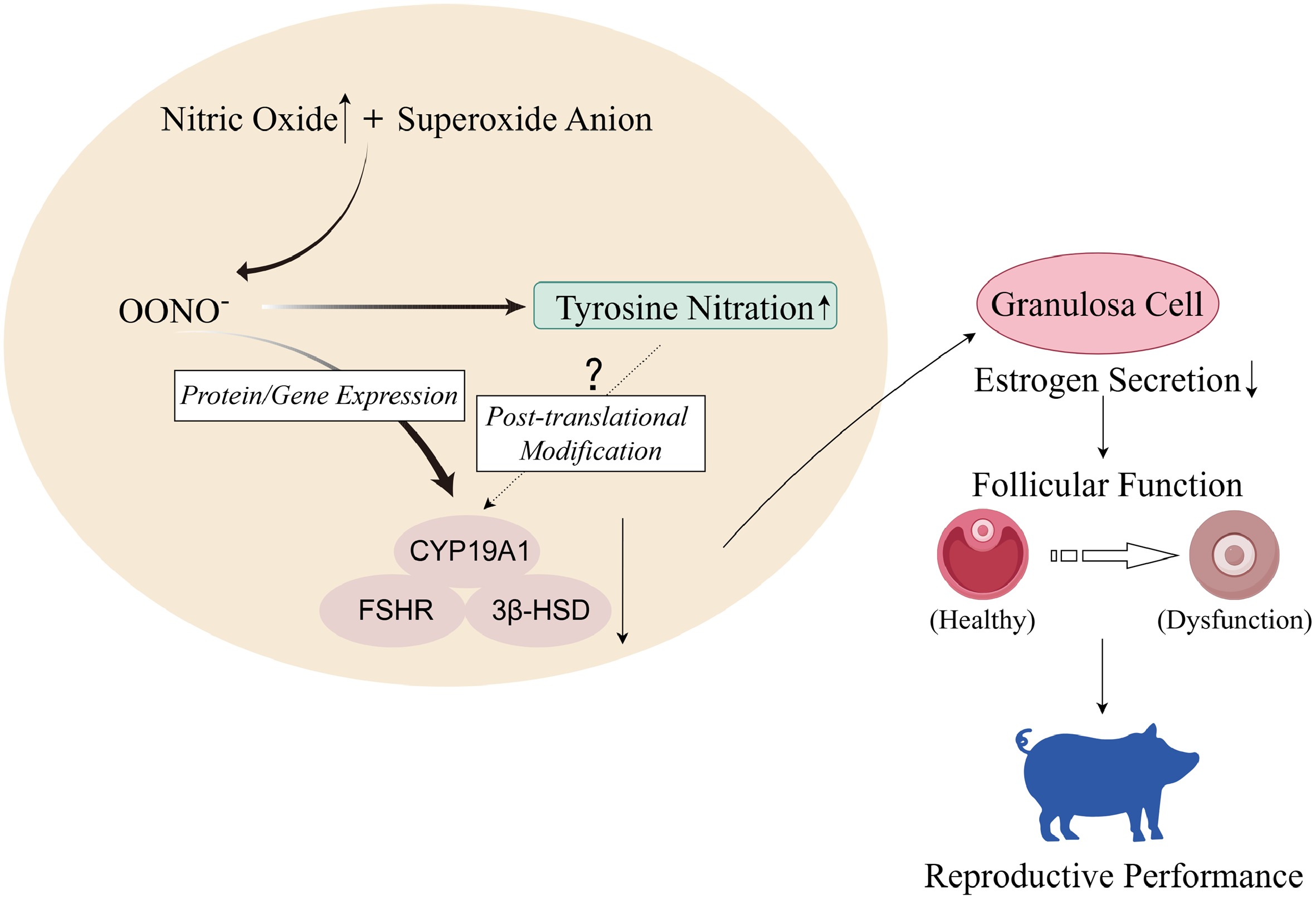

This study evaluated the effects of OONO− on GCs' function and E2 secretion. The RNA-seq results showed concentration-dependent alterations in GCs' functions and pathways. DEGs in GCs treated with 400 μM SIN-1 demonstrated significant enrichment in steroid hormone synthesis. Further studies revealed that the level of E2 secretion in GCs was decreased at this concentration, and the expression of key steroidogenic proteins and genes was also significantly reduced. In addition, the total nitrification level of GCs was significantly elevated, but the specific effects need to be explored further. In conclusion, these findings indicate that OONO− may impair GCs' function and inhibit E2 secretion via modulation of E2 synthesis-related genes and proteins (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

High concentrations of nitric oxide in organisms react with superoxide anions in reactive oxygen species (ROS) to generate peroxynitrite ions. In porcine ovarian GCs, OONO− inhibits gene and protein expression of CYP19A1, FSHR, and 3β-HSD, thereby inhibiting GCs' E2 secretion, leading to ovarian dysfunction and affecting sows' reproductive performance. In addition, OONO− will also increase the level of tyrosine nitration in GCs, but whether it will cause nitration of hormone synthesis-related proteins needs further experimental verification (figure created with Figdraw).

This study was financially supported by earmarked funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31972565, 32002183, and 31572403), Qinglan Project of Jiangsu Province, and the Science and Technology plan project of Jiangsu Vocational College Agriculture and Forestry (2021kj93).

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Nanjing Agricultural University, identification number: NJAULLSC2020052, approval date: 2020/6/15.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing – original draft: Zhang Y, Wei Q; investigation: Zhang Y, Lei K; formal analysis: Zhang Y, Lei K, Wang Z; data curation: Zhang Y, Lei K; methodology: Zhao F, Xing J, Zhu S, Li Y, Li S, Ding W, Wei Q; writing – review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and conceptualization: Wei Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The high-throughput sequencing data from Figure 5 have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The BioProject number is PRJNA1248181. This dataset can be accessed at https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1248181?reviewer=ejhrbrcc078m4vec1ajc6afrni)

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yue Zhang, Kun Lei

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Lei K, Wang Z, Zhao F, Xing J, et al. 2025. OONO− reduces the expression of steroidogenic genes and proteins to inhibit estrogen secretion in porcine ovarian granulosa cells. Animal Advances 2: e031 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0028

OONO− reduces the expression of steroidogenic genes and proteins to inhibit estrogen secretion in porcine ovarian granulosa cells

- Received: 06 February 2025

- Revised: 23 May 2025

- Accepted: 28 May 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: Granulosa cells (GCs), as critical somatic components of ovarian follicles, maintain female reproductive physiology through steroid hormone regulation and follicular development. To investigate the effects of the peroxynitrite anion (OONO−) on GCs' function and estrogen (E2) secretion in sows, GCs were treated with 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1, an OONO− donor), with subsequent validation using carboxy-PTIO (cPTIO, a NO scavenger) to confirm OONO−-specific effects. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) revealed that OONO−-induced transcriptional alterations in GCs, with Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses revealing significant pathway disruptions, including estrogen metabolism and cellular proliferation. The mechanism of the effect of OONO− on GCs' E2 secretion was further explored. The experimental data showed that OONO− inhibited E2 secretion by significantly downregulating key steroidogenic regulators (CYP19A1, 3β-HSD, and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor [FSHR]). In conclusion, this study indicated that OONO− impairs GCs physiological functions via molecular network dysregulation, leading to inhibited E2 secretion and affecting follicular development.

-

Key words:

- Granulosa cell /

- Peroxynitrite anion (OONO−) /

- Estrogen /

- Pig /

- E2 synthesis