-

Malnutrition remains a longstanding and persistent issue due to various factors, including local instability, uneven economic development across different regions, natural disasters, and specific physiological periods. Globally, there are approximately one billion humans subjected to different levels of malnutrition[1]. Pregnancy is an extremely special physiological state during which pregnant mothers are much more susceptible to malnutrition. Especially for women during late gestation, energy requirements are elevated due to the fast growth and development of the fetus[2]. Pregnant mothers who are carrying twins or multiple fetuses demand more nutrients[3], and possibly face more serious malnutrition resulting from the more severe negative energy balance[4]. Malnutrition during late gestation will cause or aggravate metabolic disorders in the body of pregnant mothers[5], inducing pre-eclampsia, hemorrhage, anemia, and insulin resistance which threaten maternal health and survival[6]. Furthermore, malnutrition during pregnancy also inhibits fetal growth and development[7,8], inducing low birthweight and birth length, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, abortion, birth defects, and even stillbirth[9]. Longitudinal investigations by the Dutch Hunger Winter (1944−1945) cohort revealed that maternal malnutrition during mid-late gestation phases, in contrast to early pregnancy exposure, was significantly associated with compromised neonatal anthropometric parameters, including cranial dimensions, parturition length, and body mass indices[10]. These defective pregnancy outcomes increase the morbidity and mortality of embryos and neonates[11].

Extensive physiological evidence documents that gestational endocrine orchestration drives metabolic reprogramming of macronutrient homeostasis (carbohydrate-lipid-protein axis), constituting a fundamental compensatory mechanism to counteract energetic deficit states during prenatal development[12,13]. The most classic method is facilitating the mobilization of body fat to provide energy for fetal growth and development. However, this physiological compensation paradoxically perturbs maternal metabolic equilibrium, manifesting through three hallmark alterations: elevated plasma-non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs), increased β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) concentrations, and concurrent development of hepatic lipid deposition[14,15]. Studies associated with malnutrition during gestation in humans and animal models however mainly belong to phenotypes. Little is known about the effect of malnutrition on metabolic changes in the fetuses. Malnutrition can result in alterations to insulin signaling, hepatic glucose production, and fat oxidation pathways, which can compromise both maternal and fetal health[16].

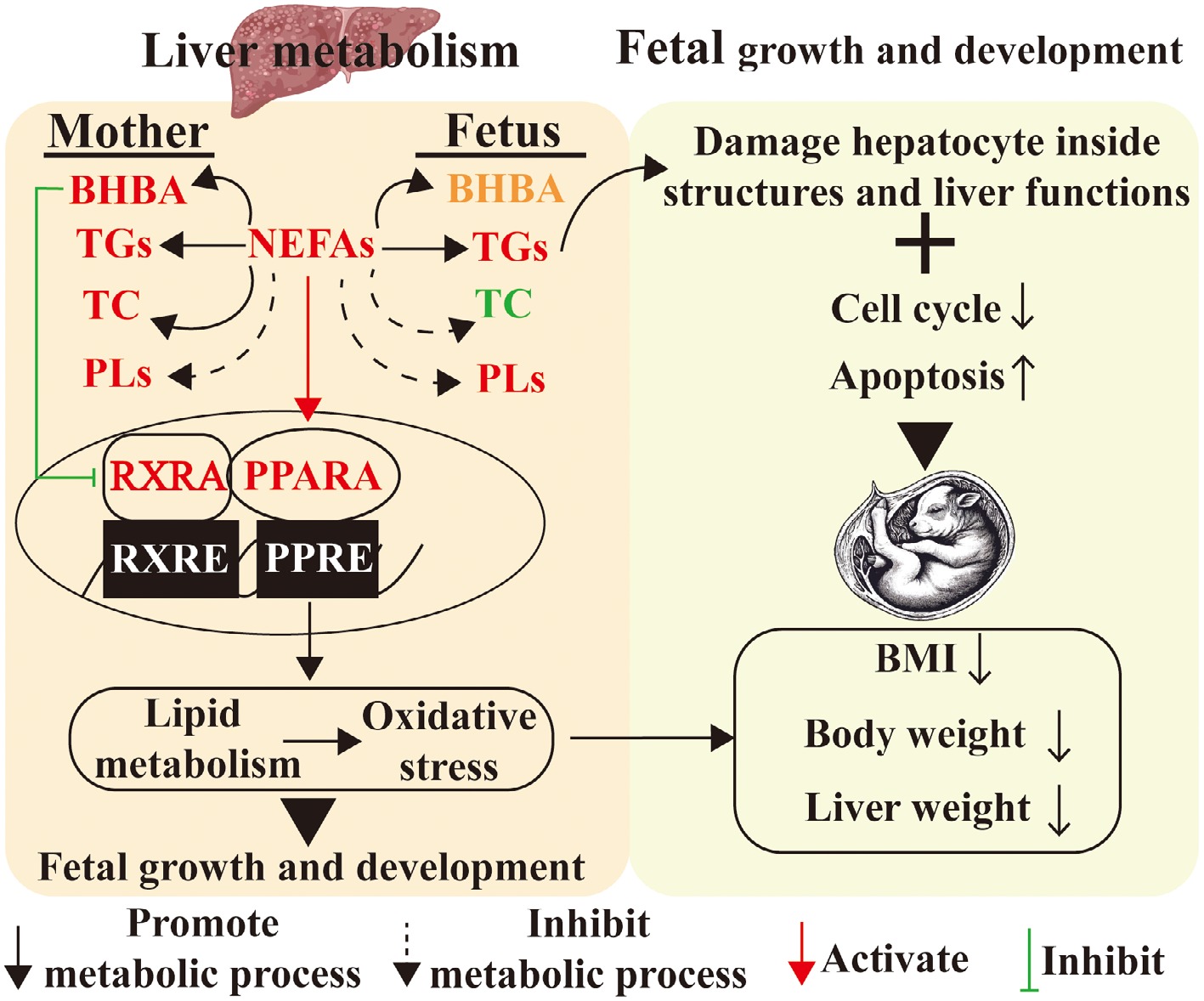

Complementing human cohort studies, experimental biological approaches employing developmental programming paradigms are increasingly elucidating the metabolic sequelae of perinatal nutritional deprivation. Rodent studies implementing 50% caloric restriction during mid-late gestation (gestational days 12.5-18.5) demonstrate transgenerational metabolic imprinting, with progeny exhibiting 25% reductions in neonatal body mass index[17,18]. In addition, malnutrition in late pregnancy leads to enhanced fatty acid oxidation and esterification as well as inhibited fatty acid synthesis and cholesterol and steroid synthesis both in maternal and fetal livers[19]. Combining in vivo pregnant sheep models and in vitro primary hepatocyte experiments reveal that metabolic changes are always accompanied by the occurrence of oxidative stress, which is closely related to many diseases[20]. The PPARA/RXRA signaling pathway, which regulates lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in the presence of nutrient deficiency, is activated by elevated substrate NEFAs and inhibited by the accumulation product BHBA[21]. Combined, these achievements fill in the gaps of metabolic changes and oxidative stress in maternal and fetal livers under conditions of malnutrition.

In this review, we highlight the effects of malnutrition on metabolic homeostasis and oxidative stress in maternal and fetal livers, as well as the potential regulated mechanisms. This will contribute to further studies on the integration of maternal and child nutrition, and the development of novel methods to restore metabolic homeostasis, mitigate oxidative stress, and improve maternal and fetal health.

-

Human studies have demonstrated that maternal body mass index predicts infant intrahepatocellular lipid storage, with hepatic fat doubling over the first 10–12 weeks of life, regardless of breastfeeding[22]. Simple anthropometric measures classify low birth weight, stunting (height deficit), or wasting (weight deficit) in early life stages, along with stature reduction or a suboptimal body mass index in adults[23]. Retrospective studies of cohorts exposed to malnutrition during prenatal and early postnatal life provide evidence supporting intergenerational effects. The Dutch 'Hunger Winter' of 1944–1945, which involved severe famine was particularly informative[24]. Maternal malnutrition during this critical developmental window predisposed progeny to multigenerational cardiometabolic perturbations including adiposity, elevated blood pressure, and dysglycemia persisting into later life stages.

In most cases, biomedical research cannot be carried out on human subjects directly due to ethical implications. Numerous animal experiments are extensively employed to investigate the biological interplay between maternal and neonatal nutritional dynamics[25,26]. Mice can reproduce rapidly, managed easily, fed with very low costs, and used for gene modification maturely, so mice are a popular and favored animal model which has been widely used to do research in biological and medical field. However, the mouse model is not perfect for human pregnancy. Because the mouse model has a small body size, low body weight, short pregnancy period (only 18−21 d), and large litter size (8−12 fetuses), which are greatly different from human beings. On the contrary, sheep models show similar body size, similar body weight, relatively long gestation, similar litter size number (mainly singleton and twins), and similar fetal size and fetal weight to human beings[27]. As ruminants, sheep rely on foregut fermentation where dietary carbohydrates are converted to volatile fatty acids as primary energy substrates − distinct from humans and non-ruminant primates that directly utilize glucose and dietary lipids[28]. Elevated urea levels in germ-free rat colons[29], experimentally cleansed human colons[28], and perfused sheep/goat colons[30] demonstrate that hindgut-entering urea is predominantly hydrolyzed to ammonia by epithelium-adherent bacteria. The resulting ammonia is primarily utilized for microbial protein synthesis or hepatic recycling to produce nonessential amino acids and urea. Therefore, even though sheep are ruminants and have a distinct digestive system, their hepatic metabolism is similar to human beings and sheep show similar phenotypes upon malnutrition during gestation. Therefore, sheep are an excellent model for human gestation and have been widely used to study mother–child nutrition[31]. Here, we synthesize findings from ovine, murine, porcine, and bovine models to elucidate hepatic lipid homeostasis mechanisms under nutritional deprivation.

-

Hepatic NEFAs are derived from dual pathways: exogenous intake and internal biosynthesis. When carbohydrates are abundant, the liver synthesizes NEFAs through de novo lipogenesis, converting excess glucose into fatty acids. This mechanism operates chiefly through transcriptional control systems. Elevated plasma insulin specifically triggers sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1C activation, with subsequent nuclear translocation driving fatty acid biosynthetic gene upregulation[32]. Concurrently, hepatic glucose overload initiates carbohydrate response element-binding protein nuclear translocation, a transcriptional driver upregulating core lipogenic genes (e.g., pyruvate kinase) to amplify citrate flux for fatty acid biogenesis[33].

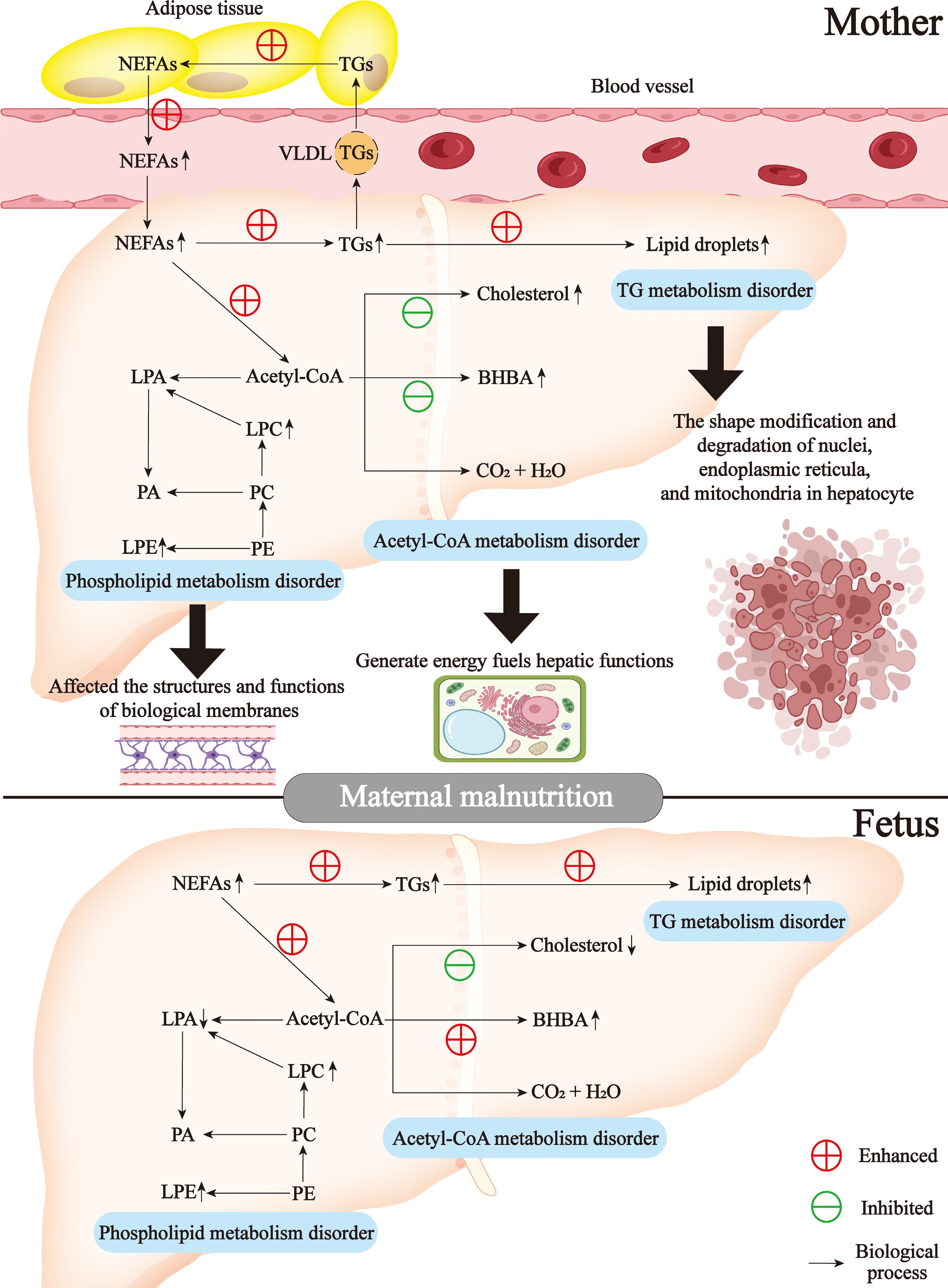

Beyond endogenous production, circulatory assimilation constitutes a major contributor to hepatic NEFAs accrual. In humans, plasma NEFAs are the primary source of liver triglycerides during fasting[34,35]. Interestingly, pregnant ewe malnutrition increased the levels of NEFAs both in the serum and in maternal and fetal livers[21] (Fig. 1). During fasting states, diminished circulating insulin concentrations activate lipolytic pathways in white adipose tissue, augmenting NEFAs reservoirs for hepatic uptake. NEFAs in circulation are predominantly bound to albumin[36] (Fig. 1). Hepatic NEFAs internalization encompasses albumin dissociation, transmembrane trafficking, cytosolic protein anchoring, and CoA-mediated esterification. NEFAs act not only as a local energy source during fasting but also as precursors for ketone genesis and cholesterol production. Interestingly, malnutrition induced an increased cholesterol level in maternal liver, but a decreased cholesterol level in fetal liver[19] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Lipid metabolism disorders in mother-child liver in response to malnutrition during late gestation. BHBA, β-hydroxybutyrate; NEFAs, non-esterified fatty acids; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; TGs, triglycerides; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

Within hepatocytes, NEFAs undergo metabolic conjugation with glycerol 3-phosphate via acyltransferase-driven pathways, generating triglycerides; alternatively, cholesterol serves as the sterol substrate for cholesteryl ester biosynthesis. These lipid species bifurcate metabolically: cytosolic lipid droplets storage vs VLDL-mediated export to systemic circulation[37] (Fig. 1). Excessive triglyceride genesis from NEFAs caused the accumulation of lipid droplets, which induced the shape modification and degradation of nuclei, endoplasmic reticula, and mitochondria in hepatocytes observed by transmission electron microscope[21] (Fig. 1). Other researchers also reported the distribution of lipid droplets in liver sections of pregnant ewes[14,15]. The shape alteration of nuclei, the derangement of endoplasmic reticula, and the vacuolation of mitochondria in hepatocytes of ewes with pregnancy toxemia are induced by malnutrition during advanced pregnancy[15]. NEFAs in the liver are also involved in the synthesis of complex lipids, including phospholipids. Interestingly, pregnant ewe malnutrition-induced upregulated levels of phospholipids including lysophosphatidyl choline and lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine both in maternal and fetal livers[19] (Fig. 1). Overall, mother-child liver NEFAs metabolism is tightly regulated by a network of interconnected transcriptional and signaling pathways, which remain an active area of research.

Mother-child hepatic fatty acid metabolism in maternal malnutrition

-

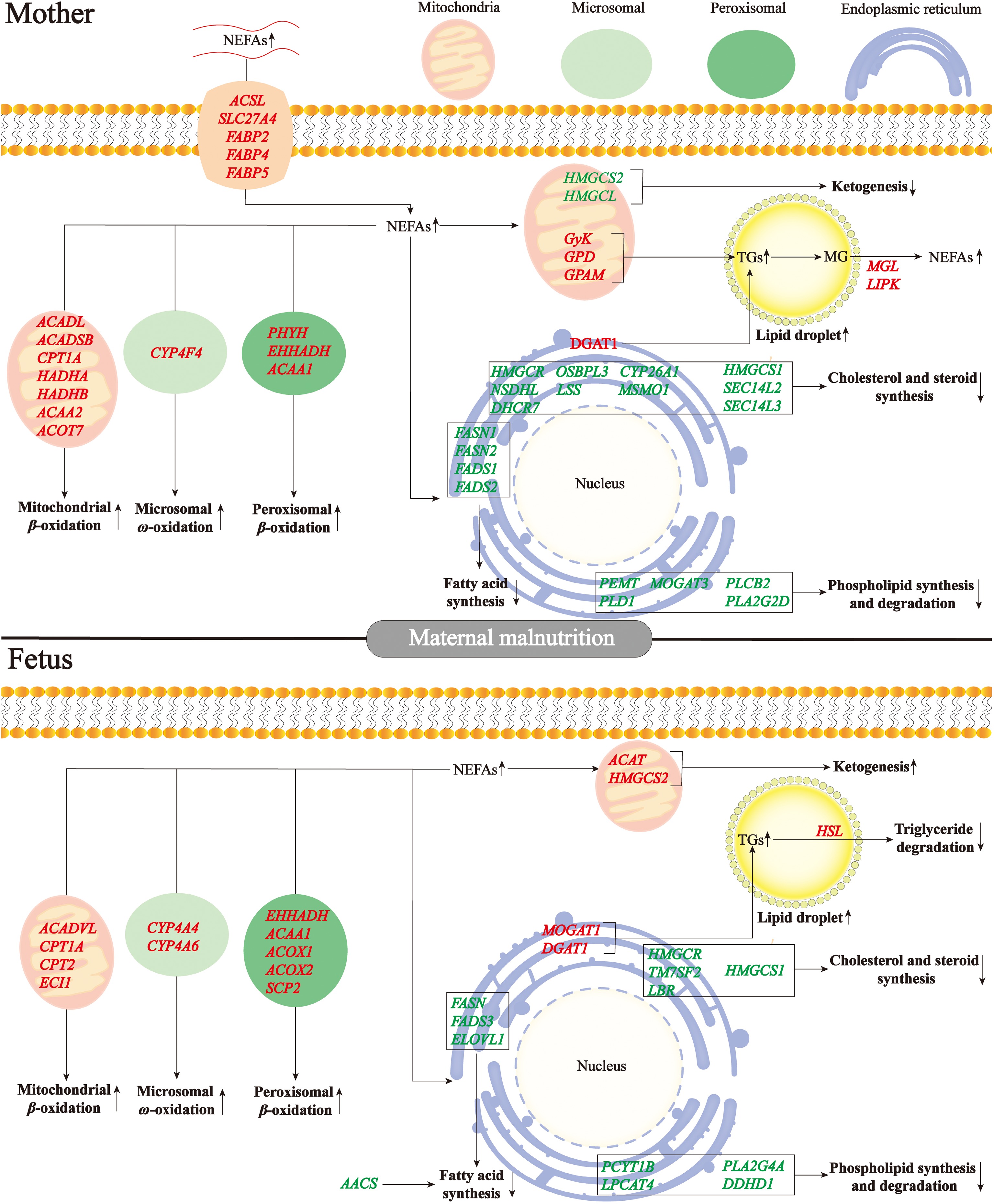

Although capable of passively traversing membranes, NEFAs predominantly undergo hepatic uptake via protein transporters[38]. Multiple transporters mediate long-chain fatty acids flux, notably membrane-bound fatty acid-binding protein, caveolin-1, and solute carriers (SLC27A1-6)[39]. Interestingly, undernutrition upregulated fatty acid transport genes (SLC27A4, FABP2, FABP4, and FABP5) in maternal liver[21], but didn't alter fatty acid transport-related genes in fetal liver[19] (Fig. 2). Hepatic NEFAs processing occurs through distinct systems. Mitochondrial β-oxidation serves as the dominant system, handling short- (< C4) to long-chain species (C4-C20), while peroxisomal oxidation specializes in very long/branched variants (C20-C26). Alternative fatty acid oxidation routes comprise endoplasmic reticulum-localized α/ω systems, catalyzed by CYP4A enzymes[40,41]. Undernutrition upregulated mitochondrial β-oxidation (ACADL, ACADSB, CPT1A, HADHA, HADHB, ACAA2, and ACOT7), peroxisomal β-oxidation (PHYH, EHHADH, and ACAA1), and microsomal ω-oxidation (CYP4F4) genes in maternal liver[21]. Meanwhile, mitochondrial β-oxidation (ACADVL, CPT1A, CPT2, and ECI1), peroxisomal β-oxidation (EHHADH, ACAA1, ACOX1, ACOX2, and SCP2), and microsomal ω-oxidation (CYP4A4 and CYP4A6) genes were upregulated in fetal liver[19]. Therefore, gestational maternal malnutrition elevated fatty acid oxidation in maternal-fetal hepatic systems (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed genes involved in lipid metabolism in mother-child liver in response to malnutrition during late gestation. MG, monoglyceride; NEFAs, non-esterified fatty acids; TGs, triglycerides.

Fatty acid synthase (FAS) serves as the principal rate-limiting enzyme in lipogenesis, modulated through diverse pathways[42]. Palmitate undergoes elongation/desaturation processing to yield various lipid derivatives. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase catalyzes acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, subsequently initiating a catalytic cascade culminating in palmitate formation. FAS is constitutively expressed and exhibited marked transcription-enzymatic upregulation in the hepatic tissue of obese rodents[43]. ACC/FAS transcriptional upregulation manifested in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease hepatic tissue[44]. Interestingly, mirroring ACC knockout phenotypes, systemic FAS ablation triggered embryolethality[45]. Malnutrition for sheep during late gestation downregulated fatty acid synthesis genes (FASN1, FASN2, FADS1, and FADS2) in maternal liver[21]. Concurrently, a significant downregulation of gene related-fatty acid synthesis was observed in fetal liver, including FASN, FADS3, and ELOVL1[19]. Therefore, maternal malnutrition during late gestation repressed fatty acid synthesis both in maternal and fetal livers (Fig. 2).

Mother-child hepatic acetyl-CoA metabolism in maternal malnutrition

-

During undernutrition, NEFAs ingurgitated by the liver can be broken down to generate acetyl-CoA through fatty acid oxidation, which is subsequently oxidized completely to CO2 and H2O via tricarboxylic acid cycle or incompletely oxidized to BHBA and cholesterol[46]. Ewe malnutrition during late pregnancy increased ketone body production and cholesterol synthesis and induced significant upregulation of BHBA and cholesterol contents in the liver and blood than normal. However, the genes linked to ketogenesis (HMGCS2 and HMGCL), cholesterol and steroid synthesis (CYP26A1, DHCR7, HMGCR, HMGCS1, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL, OSBPL3, SEC14L2, and SEC14L3) were downregulated in maternal liver[21] (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, ewe malnutrition enhanced ketone genesis (ACAT and HMGCS2), and inhibited cholesterol and steroid synthesis (TM7SF2, LBR, HMGCS1, and HMGCR) in fetal liver[19] (Fig. 2). In other models of malnutrition, including starved mice[47], ketotic dairy cows[48], and calorie-restricted pigs[49], genes associated with cholesterol synthesis were also reported to be decreased.

Mother-child hepatic TG metabolism in maternal malnutrition

-

In mammalian lipogenesis, > 90% of triacylglycerol synthesis occurs through the glycerol-3-phosphate pathway, initiating GPAM-mediated glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) acylation using acyl-CoA, followed by progressive esterification steps that ultimately form triacylglycerol through DGAT catalysis[50]. This three-step enzymatic cascade converts hydrophilic glycerol precursors into hydrophobic triglyceride through progressive fatty acid conjugation, with GPAM and DGAT serving as key flux-controlling nodes[51]. Clinical analyses reveal upregulated DGAT1 in fatty liver patients, potentially driving hypertriglyceridemia[52]. Murine studies demonstrate that DGAT1 ablation induces modest hepatic triglyceride reductions under low-fat conditions, with amplified lipid-lowering effects during high-fat feeding; these animals concurrently exhibit obesity resistance and enhanced insulin sensitivity[53]. Notably, in the sheep model, maternal malnutrition promoted triglyceride genesis both in maternal liver (GPAM and DGAT1), and in fetal liver (MOGAT1 and DGAT1)[19,21] (Fig. 2).

Adipocyte triglyceride catabolism is sequentially mediated by three lipolytic enzymes: Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) initiates lipid mobilization via rate-limiting hydrolysis of triglycerides to diacylglycerol, hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) subsequently processes diacylglycerol into monoglycerides, with monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) ultimately liberating glycerol and NEFAs through monoglycerides cleavage[54]. Interestingly, in the sheep model, maternal malnutrition upregulated triglyceride lipolysis genes both in maternal liver (MGL and LIPK)[21] and fetal liver (HSL)[19] (Fig. 2). Therefore, even though the upregulated lipolysis, the extremely enhanced triglyceride genesis upon undernutrition during late gestation caused the accumulation of lipid droplets both in maternal and fetal livers.

Mother-child hepatic phospholipid metabolism in maternal malnutrition

-

Hepatic NEFAs flux bifurcates into complex lipid biosynthesis through two key nodal intermediates: lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) undergoes acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases (AGPAT)-mediated endoplasmic reticulum membrane esterification to phosphatidic acid (PA), which subsequently diverges into CDP-diacylglycerol for specialized phospholipids/cardiolipin synthesis, or phosphohydrolase-processed diacylglycerol serving as the metabolic nexus for triglycerides and membrane phospholipids (PC/PE)[55,56]. Sheep undernutrition during late gestation induced the downregulation of genes involved in phospholipid degradation and synthesis (PEMT, MOGAT3, PLD1, and PLCB2D) in maternal liver, yet paradoxically increased lysophosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylethanolamine content in the liver[21]. This apparent contradiction likely originates from compensatory extrahepatic lysophospholipid synthesis in placental/adipose tissues with subsequent systemic release and hepatic uptake[57,58], thereby inducing transcriptional suppression of phospholipid metabolism genes through feedback regulation of accumulated products[59]. Meanwhile, a significant downregulation of genes associated with phospholipid degradation and synthesis was observed in fetal liver, including PCYT1B, LPCAT4, PLA2G4A, and DDHD1, yet paradoxically increased lysophosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylethanolamine content and reduced lysophosphatidic acid content in the liver[19]. Therefore, maternal malnutrition during late gestation repressed phospholipid synthesis and degradation both in maternal and fetal livers (Fig. 2).

-

During fetal development, maternal malnutrition may induce irreversible changes to the structure and function of fetal tissues, including cell number, cell type, and functional units, which will potentially change physiological function and susceptibility to related diseases during the offspring's later life. This process is called 'programming'[60], and maternal nutrition is associated with fetal programming[61]. While population-level analyses (n = 643,902) confirm developmental origins of metabolic programming through DOHaD mechanisms, experimental models crucially reveal maternal nutritional insults during adolescence induce fetal growth restriction via placental nutrient sensing dysregulation and epigenetic remodeling, establishing causal relationships obscured in human observational studies[62]. Malnutrition during late gestation significantly lowered fetal liver weight, and fetal body weight in a sheep model[19]. This was consistent with previous studies where maternal malnutrition had a detrimental influence on fetal development, especially in twin pregnancies[25,26]. Accumulating evidence from cross-species investigations (murine, lagomorph, and sheep models) have established that maternal malnutrition induced consistent patterns of growth restriction, with results revealing significant impairments in both fetal morphometric indices and hepatic organogenesis parameters[63−65].

Maternal malnutrition-induced lipid metabolism disorders inhibit fetal development

-

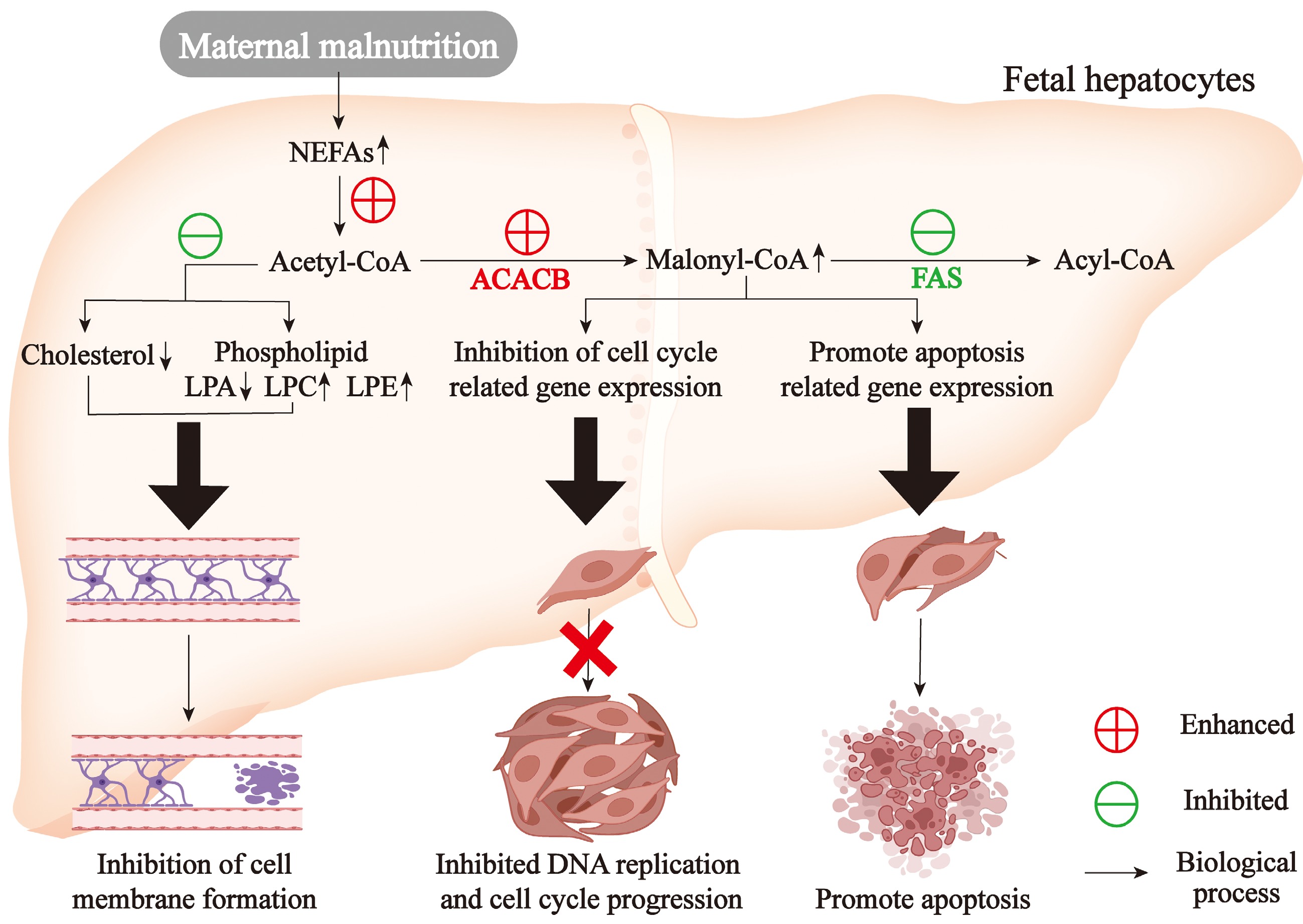

Cholesterol is essential for fetal development due to its critical role in cell proliferation and differentiation[66,67]. Fetal cholesterol requirements depend on maternal supply during early gestation but depend on its biosynthesis during late gestation[68]. Thus, maternal malnutrition during late gestation inhibited cholesterol and steroid synthesis in fetal liver which would slow down fetal development. In addition, phospholipids are essential components of biological membranes[69,70], so phospholipid metabolism disorders in fetal livers of undernourished mothers would possibly damage the membranes' permeability and threaten cell survival. The genes related to cell cycle and anti-apoptosis were significantly correlated with NEFAs and triglyceride content and the expression of genes linked to fatty acid de novo synthesis[19]. FAS inhibition could repress DNA replication and facilitate apoptosis in tumor cell lines[71]. FAS inhibition could accumulate malonyl-CoA and then induce apoptosis in breast tumor cells[72]. Interestingly, inhibition of FAS markedly enhanced cell apoptosis in the liver mouse[73]. However, FAS inhibition induced apoptosis in cancer cells via malonyl-CoA accumulation, its role in fetal hepatocytes remains speculative. In fetal livers of undernourished ewes, ACACB was upregulated while FAS was downregulated, which might cause the accumulation of malonyl-CoA and induced cell apoptosis[19]. Some studies also showed NEFAs could retard the progression cell cycle[74] and induce cell apoptosis. Further, triglyceride stack in fetal livers of undernourished mothers damaged hepatocyte inside structures and liver functions, inhibiting the development of the liver and even the whole body. Maternal malnutrition disrupted fetal hepatic lipid metabolism including cholesterol biosynthesis, phospholipid homeostasis, and fatty acid synthesis, and triglyceride metabolism, and these cascading metabolic disturbances collectively impaired cellular proliferation, membrane stability, and energy homeostasis, ultimately restricted fetal growth.

Molecular mechanisms of maternal malnutrition-associated fetal maldevelopment

-

Transcriptomic profiling in a sheep model revealed that late-gestation maternal malnutrition induces multi-layered dysregulation in fetal hepatic development: (1) Cell proliferation module: coordinated downregulation of 17 DNA replication genes (e.g., MCM complex members, POLA family) and 31 cell cycle regulators (CDK/cyclin/E2F axis), indicating G1/S checkpoint dysregulation; (2) Apoptosis-proliferation balance: suppressed anti-apoptotic factors (BCL2L1, BIRC5, SIVA1, and MAP4K4) synergized with replication stress, suggesting genomic instability. Mechanistically, RT-qPCR and immunoblotting confirmed translational repression of CDK1/6-CCNB1/E1 signaling hub[19]. Maternal malnutrition triggered multi-organ developmental constraints through transcriptional reprogramming. Coordinated suppression of cell cycle hubs (CCNE1/CDK1-6) and anti-apoptotic mediators (BCL2L1) synergized with caspase cascade activation (CASP3/8/9-BAX axis), quantitatively correlating with reduced liver/body weight[75]. Parallel transcriptional repression of G1/S transition regulators (CCND1/E2F cluster) revealed conserved PI3K-AKT pathway disruption across fetal thymic tissues[76]. Collectively, lipidomic reprogramming-induced replication fork stalling created a pro-apoptotic metabolic milieu and cell cycle arrest drove fetal growth restriction and maldevelopment (Fig. 3).

-

Lipid metabolism regulation is governed by interconnected signaling cascades. At its core lies the insulin receptor (IR) cascade, where IR activation initiates IRS1 phosphorylation followed by AKT activation, establishing a critical regulatory axis[77]. Complementing this pathway, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) exhibit isoform-specific metabolic governance: PPARA directs fatty acid uptake, transport, and β-oxidation, ketogenesis, and lipoprotein dynamics; PPARδ enhances substrate utilization through mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid desaturation pathways; PPARγ acts as a master regulator of adipogenesis, promoting triglyceride synthesis and lipid droplet formation to optimize insulin sensitivity[78]. This regulatory landscape is further enriched by synergistic interactions among key metabolic sensors. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) coordinates de novo lipogenesis through crosstalk with the PI3K-AKT signaling, while AMP-activated protein kinase α (AMPK) serves as an energy rheostat, phosphorylating downstream targets to restore metabolic equilibrium[79]. Concurrently, liver X receptor α (LXRα) modulates cholesterol homeostasis through transcriptional regulation[80]. Emerging evidence reveals that maternal nutritional status during gestation exerts lasting epigenetic effects on offspring metabolic programming by selectively activating or suppressing these lipid regulatory pathways.

Malnutrition regulates lipid metabolism through PPARA/RXRA signaling

-

The similarities and differences of lipid metabolism between maternal and fetal livers under the condition of malnutrition during late gestation based on transcriptomes exposure to the potential signal pathways involved in lipid metabolism disorders[81]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARA) signaling and retinol metabolism were enriched significantly by DEGs in maternal livers, implying that PPARA/retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRA) signaling pathway may be involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism. PPARA governs lipid metabolic networks through transcriptional control of multi-organellar oxidation systems (microsomal, peroxisomal, mitochondrial), lipid ligand trafficking, chain remodeling, and dynamic triglyceride/lipid droplet turnover[82,83]. Moreover, 9-cis-retonic acid, one of the metabolites in retinol metabolism, is an effective ligand for RXRA[84], and RXRA is the molecular chaperone of PPARA. 9-cis-retonic acid was able to intensify fatty acid oxidation in rat hepatocytes[85]. RXRA was required for PPARA and 9-cis-retonic acid could enhance PPARA action[86]. When PPARA and RXRA were activated by their ligands, respectively, they would combine to form heterodimers and enter nuclei to bind with PPRE and RXRE in the target genes and then regulate their expressional levels[87]. NEFAs were effective ligands to activate PPARA[88] and NEFAs content was significantly positively correlated with PPARA and fatty acid oxidation-related genes. While highly concentrated BHBA inhibited the mRNA and protein of HMGCS2[89,90], a key enzyme associated with ketogenesis. Moreover, BHBA contents were significantly negatively correlated with RXRA and fatty acid oxidation-related genes. Thus, Xue et al.[19] hypothesized that NEFAs might activate PPARA signaling and BHBA might inhibit RXRA signaling and then regulate lipid metabolism in maternal and fetal livers upon malnutrition. Therefore, they used different concentrations of NEFAs, BHBA, WY14643 (PPARA agonist), and 9-cis-retinoic acid (RXRA agonist) to treat primary hepatocytes isolated from sheep. The results confirmed that NEFAs could activate PPARA signaling and enhance fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis. BHBA suppresses RXRA signaling, reducing lipid oxidation and ketogenesis; Activation of the PPARA/RXRA axis enhances these catabolic processes while inhibiting triglyceride synthesis under elevated NEFAs conditions. Therefore, in maternofetal livers of ewe malnutrition, hepatic NEFAs levels elevated significantly which activated PPARA signaling and enhanced fatty acid oxidation. However, hepatic BHBA levels increased markedly in maternal livers which repressed the RXRA signaling pathway and inhibited ketogenesis. In contrast, in fetal livers of undernourished ewes, BHBA levels showed no significant changes which were not high enough to inhibit the RXRA signaling pathway and the down-stream ketogenesis.

Malnutrition regulates oxidative stress through PPARA/RXRA signaling

-

It is well-known that alterations in metabolic homeostasis can induce oxidative stress in the body. Oxidative stress has a high correlation with many diseases[91]. Sheep showed significantly decreased superoxide dismutase activity and glutathione reductase activity during pregnancy. Oxidative indicators were increased while antioxidant indicators were decreased in the blood, maternal livers, and fetal livers of undernourished ewes, revealing that malnutrition induced oxidative stress in maternofetal livers[81]. Some studies reported that NEFAs derived from lipolysis in adipose tissues induced ROS and oxidative stress[92,93]. Elevated NEFAs/BHBA concentrations induced hepatocellular oxidative-antioxidant imbalance, manifested by dose-dependent elevations in H2O2 and MDA levels coupled with reductions in CAT/SOD activities and TAC. These changes positively correlated with oxidative markers and inversely associated with antioxidant gene expression[81]. Further, primary hepatocyte assays confirmed these metabolites disrupt redox homeostasis, while PPARA/RXRA activation counteracts oxidative damage through enhanced antioxidant defenses[81]. Pharmacological PPARA activation (fenofibrate) similarly increased hepatic GSH/SOD while reducing MDA in murine models[94]. Interestingly, combined fasting and SOD knockout in mouse livers significantly increased both fatty acid synthesis capacity and triglyceride accumulation, indicating a critical regulatory role of oxidative stress in lipid metabolism[95]. Collectively, PPARA/RXRA-mediated metabolic regulation alleviates lipid disorder-associated oxidative stress through dual modulation of redox systems (Fig. 4). However, excessive PPARA/RXRA activation may disrupt hepatic metabolic homeostasis, but the specific mechanism still needs further exploration. Pharmacologically, PPAR agonists represent a potential therapeutic avenue for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Specifically, PPARA activation is anticipated to ameliorate the metabolic overload associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. However, clinical trials investigating fibrates (PPARA agonists) demonstrated suboptimal efficacy[96]. This outcome prompted the exploration of selective PPAR agonists, including saroglitazar (PPARA agonist)[97] and elafibranor (PPARA agonist)[98]. However, structural deviations in ligand recognition at PPARA/RXRA binding sites could induce off-target effects through aberrant activation of parallel signaling pathways.

-

Maternal undernutrition during late gestation triggers hepatic lipid dysregulation characterized by paradoxical activation of lipid turnover pathways. In maternal liver, this manifests as upregulated β-oxidation coupled with accelerated triglyceride turnover (enhanced synthesis/degradation), alongside suppressed sterol/phospholipid biosynthesis, and ketogenic capacity. Conversely, fetal hepatocytes exhibit similar triglyceride cycling intensification with concurrent β-oxidation/ketogenesis elevation, but more pronounced phospholipid and cholesterol synthesis deficits. These transgenerational metabolic disturbances impair fetal hepatic cell cycle progression through DNA replication inhibition, creating proliferative-apoptotic imbalance that culminates in developmental compromise. Mechanistically, malnutrition-induced NEFAs accumulation activates PPARA-driven lipid catabolism, whereas elevated BHBA suppresses RXRA-mediated metabolic coordination. This dual-target approach demonstrates therapeutic potential by: (1) Restoring hepatic lipid homeostasis through balanced anabolic/catabolic regulation; (2) Breaking the malnutrition-oxidative damage vicious cycle; and (3) Preserving developmental plasticity during critical gestational windows. Therefore, targeted activation of PPARA/RXRA signaling emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy to restore lipid homeostasis and mitigate oxidative damage, offering potential interventions for intrauterine malnutrition-associated developmental disorders.

-

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32402767), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1301102), Anhui Province Natural Science Foundation (2308085QC104), and AAU Introduction of High-level Talent Funds (RC392107).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study design and manuscript writing: Xue Y, Liu W, Jiao P; table developing and formatting: Lu H, Liu S, Zhuo Z, Liu W, Jiao P; manuscript revising: Xu Y, Lu H, Jiao P, Xue Y, Chen Y, Fan C, Cheng J, Mao S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Peng Jiao, Yun Xu, Huizhen Lu

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiao P, Xu Y, Lu H, Xu Y, Fan C, et al. 2025. Malnutrition during gestation induces lipid metabolic disorders in maternal and fetal livers and eventually affects fetal development. Animal Advances 2: e033 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0029

Malnutrition during gestation induces lipid metabolic disorders in maternal and fetal livers and eventually affects fetal development

- Received: 22 February 2025

- Revised: 13 June 2025

- Accepted: 18 June 2025

- Published online: 01 December 2025

Abstract: Malnutrition is common during gestation, which threats maternal health, survival, and fetal development. The mechanisms of malnutrition-induced metabolic disorders and fetal maldevelopment are however poorly understood. In recent years, numerous studies in human and animal models have filled the gaps in the field of mother-child metabolism regarding malnutrition during gestation. This review summarizes and analyzes the lipid metabolic disorders in maternal and fetal livers, as well as fetal maldevelopment in response to malnutrition during gestation, and the regulatory mechanisms involved. Malnutrition elevates fatty acid oxidation, esterification, and lipolysis while suppressing fatty acid, cholesterol, steroid synthesis, and phospholipid metabolism both in maternal and fetal livers. Intriguingly, ketogenesis is inhibited in maternal liver but enhanced in fetal liver. Maternal malnutrition induces fetal hepatic lipid metabolic dysregulation, which suppresses DNA replication machinery and disrupts cell cycle progression, thereby creating an imbalance between cellular proliferation and apoptosis, ultimately culminating in fetal maldevelopment. Under conditions of malnutrition, non-esterified fatty acids stimulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARA) signaling to upregulate fatty acid β-oxidation and ketogenesis, whereas β-hydroxybutyrate inhibits these metabolic processes through suppression of retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRA) signaling. Activation of PPARA/RXRA signaling pathway improves liver lipid metabolic homeostasis and alleviates oxidative stress. This review contributes to the research on mother-child nutritional metabolism and the development of novel strategies during gestation to advance the health of mother and offspring.

-

Key words:

- Mother-child nutrition /

- Lipid metabolism /

- Oxidative stress /

- PPARA/RXRA signaling