-

In recent years, cases of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a fatal infection caused by the 'brain-eating amoeba' Balamuthia mandrillaris, gained significant attention on Chinese social media following reports of multiple infections among children in several provinces[1], predominantly linked to water-based recreational activities during the summer break[2]. In 2025, an outbreak of another 'brain-eating amoeba', Naegleria fowleri, was reported in Kerala, India, resulting in 69 confirmed cases and 19 fatalities, which heightened public concern in the region[3]. As of now, more than 33 countries worldwide have reported approximately 500 cases[4,5]. While the majority of cases have been reported in the United States[6], Mexico, Australia, and Pakistan[7], infections have also been documented across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania[8,9].

The pathogens involved are amoebae, free-living protists that are mostly harmless, while a subset can be lethal. Amoebae are single-celled protists capable of changing shape and moving via pseudopodia, allowing them to inhabit diverse environments such as water and soil. While most amoebae are harmless, some species can cause severe human diseases. For instance, Entamoeba histolytica is a parasitic amoeba responsible for amoebic dysentery, which can lead to severe intestinal and hepatic conditions. This infection remains a significant global health burden, particularly in regions with poor sanitation and limited access to safe drinking water[10,11].

Another pathogenic amoeba, Naegleria fowleri, commonly known as the 'brain-eating amoeba', causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis[12,13], which has a case fatality rate exceeding 98%[14]. Due to their significant public health impact, these amoebae have recently been designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as priority pathogens for research and control[15].

-

In addition to being pathogens themselves, amoebae can significantly influence the fate of other biocontaminants. As one of the oldest microbial predators in nature, amoebae feed on bacteria, fungi, and viruses through phagocytosis[16,17]. While most ingested microbes are eliminated within phagosomes via acidification, oxidation, and nutrient deprivation, certain bacteria, which are known as amoeba-resisting bacteria (ARB), can evade or resist these killing mechanisms. These ARBs can survive and replicate within amoebic trophozoites and cysts, eventually being released back into the environment[18−20]. Notably, ARBs include not only nonpathogenic bacteria but also human pathogens such as Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia, and Mycobacteria[21]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and L. pneumophila can not only survive within amoebae but also benefit from enhanced pathogenicity, as amoebae provide protection against disinfection treatments and facilitate their prolonged environmental persistence[22−24]. Beyond safeguarding fungi such as Cryptococcus neoformans through predation[25,26], amoebae also act as hosts for enteric viruses such as coxsackieviruses, human norovirus, and adenovirus, significantly enhancing their environmental persistence[27,28]. This ability turns amoebae into a 'Trojan horse', facilitating the survival, dissemination, and even the spread of antimicrobial resistance among pathogens in aquatic and soil ecosystems[29].

In addition, recent studies indicate that amoebae can serve as unexpected reservoirs of biocontaminants, including antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), underscoring their potential role in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. For instance, an investigation revealed that Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae collected from the topsoil of a forest park carried substantial levels of both ARGs, encompassing β-lactam, multidrug, and aminoglycoside among others, and metal resistance genes (MRGs), including those for elements such as Cu, As, Zn, and Hg[30]. Separately, another study isolated 24 amoeba strains from tap water, representing diverse phylogenetic groups, and demonstrated that these amoebae can act as vectors for bacteria, viruses, ARGs, and virulence factors[31]. Furthermore, certain amoebae have been shown to protect their internalized bacteria from disinfection, thereby complicating the removal of ARGs and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in drinking water systems[31,32]. Collectively, these findings illustrate that amoebae not only function as emerging pathogens but also significantly influence the persistence and spread of other biocontaminants.

-

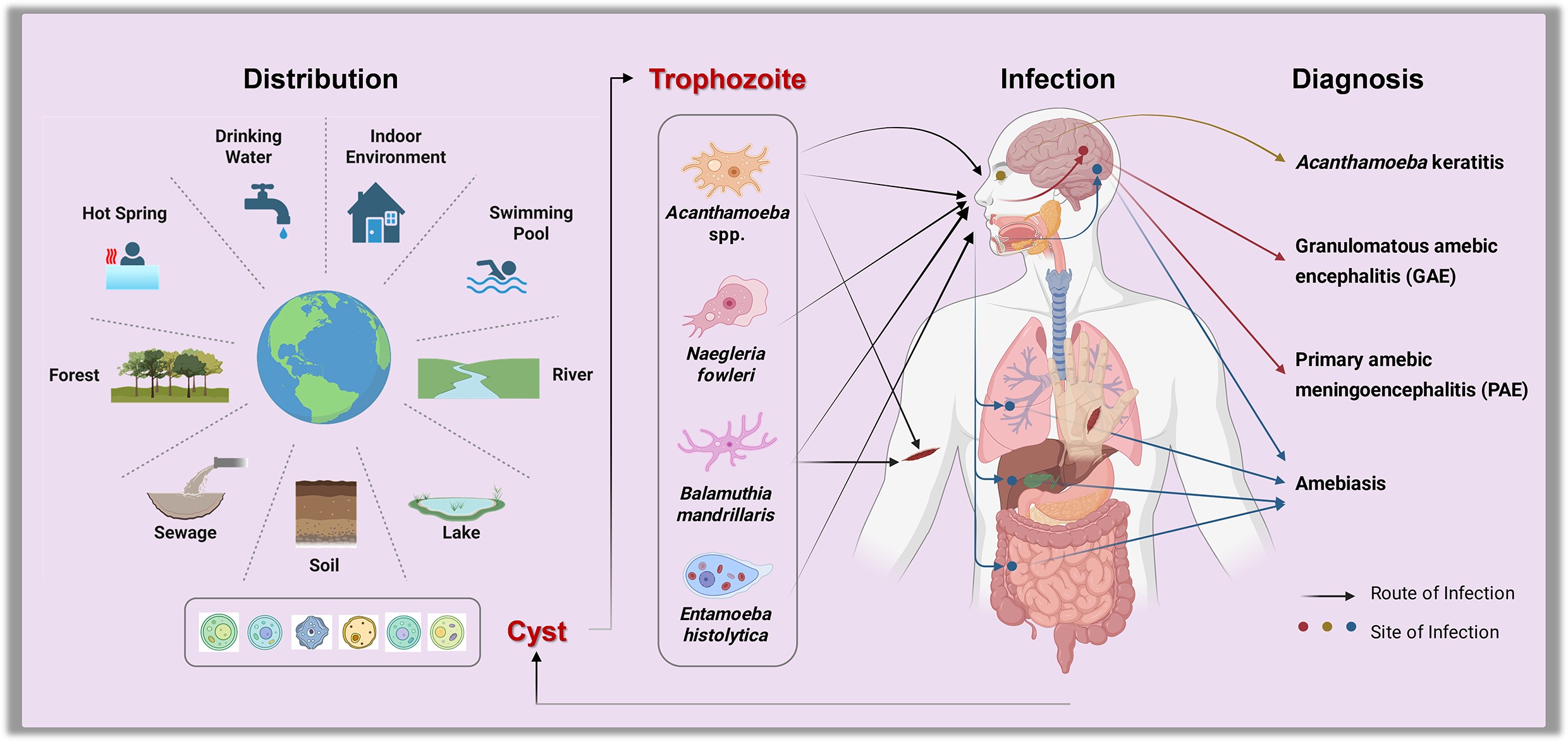

Amoebae are widely distributed in natural environments, such as soil, water, and air, due to their adaptability and resilience[19,33−35]. They not only thrive in natural water bodies such as lakes, rivers, and ponds, but also in human-made systems like drinking water distribution networks, swimming pools, sewage systems, and hot springs[36−41]. This broad environmental presence increases the risk of human exposure, potentially facilitating disease transmission.

Studies have frequently detected amoebae, including pathogenic species, such as Acanthamoeba spp. and N. fowleri, in treated drinking water supplies and recreational waters[42]. Consequently, common activities like swimming are exposure routes. The risks may be further amplified in some regions by specific religious and cultural practices, where rituals such as ceremonial bathing and the use of neti pots for nasal irrigation can serve as significant additional pathways for infection[43].

N. fowleri, which typically inhabits warm freshwater or polluted environments[43], invades the central nervous system by ascending from the nasal mucosa via the olfactory nerve, ultimately causing the severe inflammation characteristic of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis[14,44−46]. Similarly, A. castellanii and B. mandrillaris can cause granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) and Balamuthia amoebic encephalitis (BAE), respectively[47−49]. A. castellanii and B. mandrillaris can invade the human body through breaches in the skin or nasal passages and may subsequently disseminate to the brain, causing severe infections[50]. A. castellanii can infect the cornea and cause amoebic keratitis, a sight-threatening infection primarily associated with contaminated contact lenses that can result in blindness in severe cases[51−53].

The accurate scale of human exposure to amoebae is likely substantially underestimated. Prior to the widespread adoption of molecular techniques, traditional microscopy and culture methods were inadequate for confirming such cases, resulting in significant underdiagnosis[44,54,55]. Amoebic infections are prone to clinical misdiagnosis as other diseases, as amoebae in traditional microscopy are easily confused with yeast, macrophages, or other artifacts, thereby eliminating the impetus for molecular testing and substantially elevating misdiagnosis rates[56]. Given the ubiquity of amoebae across diverse environments[57], the actual exposure level is likely far greater than currently recognized. Together with historical diagnostic limitations, these factors indicate a significant burden of undiagnosed and underreported infections, highlighting a considerable underestimation of this public health threat.

-

The control of amoebae-related health risks presents significant challenges due to the remarkable resilience of these pathogens, particularly in their cyst forms, which allow them to survive conventional water treatment processes, including chlorination and filtration[32,58]. Notably, particular species, such as Acanthamoeba, have been reported to withstand chlorine concentrations as high as 100 mg/L for 10 min[59], while others, like Vermamoeba vermiformis, show high levels of chlorine tolerance, with studies indicating minimal inactivation even at a CT value of 35 (mg·min)/L[31]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that exposure to sublethal chlorine doses may even enhance the virulence of some amoebae, such as A. castellanii, by upregulating the expression of their virulence genes. Besides chemical disinfection, physical barriers such as membrane filtration can be compromised, as amoebae can use ultrafiltration membranes as growth interfaces, thereby contributing to biofouling[60]. In contrast, ultraviolet (UV) disinfection at conventional germicidal wavelengths (e.g., 254 nm) also shows limited effect against resistant cysts[32,61,62].

Given the limitations of traditional methods, advanced oxidation strategies show promising potential for effective inactivation. For instance, the FeP/persulfate system can achieve a 1-log reduction in amoebic spore viability and a more substantial 4-log reduction in the viability of intracellular bacteria housed within the spores[63]. Similarly, a MoS2/rGO composite utilizing piezocatalysis achieved a 4.18-log reduction in amoebic spores and a 5.02-log reduction in intracellular bacteria within 180 min[64]. Another innovative approach, a two-electron water oxidation strategy using BiSbO4 as an anode material, effectively inactivated amoeba spores and their intracellular bacteria, achieving inactivation rates of 99.9% and 99.999%, respectively[65].

Beyond end-point disinfection, source control is also an essential measure. Amoebae are predominantly found in biofilms within distribution pipe networks and point-of-use filters[41,66]. Therefore, physical removal through pipeline flow velocity adjustment and regular flushing, or chemical intervention, can be employed to address biofilm in distribution networks[67].

The threat posed by amoebae is compounded by environmental changes, particularly climate warming, which is anticipated to expand the geographical distribution of thermophilic species like N. fowleri, potentially increasing incidence in previously unaffected regions. This growing risk is underscored by the increase in fatal cases of primary amebic meningoencephalitis globally. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued guidelines in 2025 specifically for controlling N. fowleri in drinking-water systems, signaling increased international attention to amoeba-related public health risks and marking a critical step toward a coordinated global response. Ultimately, mitigating the risks from amoebae requires a multi-faceted approach that combines robust water safety plans—encompassing system assessment, operational monitoring, and management—with the adoption of advanced inactivation technologies and continued vigilance in the face of environmental change.

-

Amoebae represent a significant and evolving public health threat, necessitating an integrated One Health approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. Effective mitigation requires comprehensive strategies combining enhanced surveillance, rapid diagnostics, and targeted environmental interventions. Key priorities include understanding how global changes, such as climate shift and biodiversity loss, influence the geographic distribution and transmission dynamics of pathogenic amoebae. Genomic tools are critical for pathogen detection and for deciphering mechanisms of environmental adaptation and virulence evolution. Additionally, developing highly sensitive, rapid, and quantitative detection methods is essential to establish reliable early warning systems.

Despite growing awareness, critical knowledge gaps impede effective risk management and outbreak prevention:

(1) Ecological drivers: The precise ecological and environmental factors that facilitate the emergence and spread of pathogenic amoebae are poorly understood. Research is needed to elucidate how factors like climate change, land-use changes, and shifts in microbial communities affect the abundance and pathogenicity of amoebae in the environment.

(2) Control strategy: While amoebae are known for their general resilience, the effectiveness of disinfection strategies (e.g., chlorine, UV) can vary dramatically between different amoeba species and their life stages (trophozoites vs cysts). There is a significant lack of quantitative, species-specific data on inactivation rates for many pathogenic amoebae. This gap makes it challenging to establish science-based regulatory standards for water treatment that are guaranteed to be effective against all threatening species.

(3) Diagnostics and therapeutics: For many amoebic infections, especially those affecting the central nervous system, current diagnostic methods are often slow, inaccessible in low-resource settings, and can have high error rates[54−56]. Furthermore, the prognosis for infections like primary amebic meningoencephalitis and granulomatous amebic encephalitis remains poor, with mortality rates exceeding 97%. There is an urgent need to develop affordable, rapid point-of-care diagnostics and more effective, accessible therapeutic protocols.

(4) Microbial interactions: The role of amoebae as reservoirs and training grounds for other pathogens is a critical aspect of their public health threat. However, the full spectrum of these interactions across diverse environmental microbiomes and their contribution to the spread of antibiotic resistance genes remains poorly quantified. More research is needed to understand how these 'Trojan horse' dynamics impact the effectiveness of water safety plans and public health outcomes.

(5) Build an integrated surveillance network: Establish a coordinated surveillance and data-sharing system that integrates clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and wastewater management. This will create an end-to-end monitoring framework covering prevention, detection, diagnosis, and source tracing.

(6) Foster cross-disciplinary collaboration: Promote interdisciplinary cooperation under the One Health framework by systematically linking environmental microbiology, clinical medicine, and public health policy. This integrated approach will bridge preventive control, diagnosis, and treatment, forming a closed-loop management system.

(7) Strengthen public education and health awareness: Launch targeted public awareness campaigns focusing on high-risk periods like summer and high-risk activities (swimming, diving in warm freshwater lakes, rivers, and poorly maintained pools). Key messages should emphasize practical precautions: using nose clips to prevent water from entering, avoiding submersion of the head, and refraining from disturbing sediment in shallow areas. Engaging high-risk groups and healthcare providers can enhance early recognition and reduce exposure.

(8) Define future research priorities: Accelerate genomic studies to uncover virulence factors and ecological drivers of pathogens like N. fowleri, using whole-genome sequencing to track strains and identify targets for interventions. Clarify pathogenic mechanisms, including how amoebae invade the brain via the olfactory nerve and evade immune responses, and explore host-pathogen interactions to pinpoint host factors that increase susceptibility. Integrate environmental and clinical data to guide public health strategies.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zheng J, Shu L, Hu R, Shi Y, He Z; draft manuscript preparation: Zheng J, Shu L; manuscript revision: Hu R, Shi Y, He Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This material is based upon work supported by the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant No. 2023B1515020096), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42277382), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2023A1515011526), and the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (Grant Nos SML2024SP022, SML2024SP002).

-

The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Amoebae are emerging pathogens of significant public health concern.

Amoebae can serve as vectors for various biocontaminants, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and resistance genes.

Climate and environmental changes are amplifying human exposure to and infection by pathogenic amoebae.

A One Health approach is crucial for mitigating amoeba-related risks effectively.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng J, Hu R, Shi Y, He Z, Shu L. 2025. The rising threat of amoebae: a global public health challenge. Biocontaminant 1: e015 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0019

The rising threat of amoebae: a global public health challenge

- Received: 21 October 2025

- Revised: 17 November 2025

- Accepted: 21 November 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: Amoebae, single-celled protists capable of altering their shape and moving via pseudopodia, represent a growing public health threat worldwide. Free-living species such as Naegleria fowleri and Acanthamoeba spp. are of particular concern. Although often overlooked in conventional biosecurity research, these protozoa can survive extreme environmental conditions, including high pH, elevated temperatures, and high chlorine concentrations, making them resistant to standard water treatment approaches. Their widespread presence in both natural and engineered environments poses significant exposure risks through contaminated water sources, recreational water activities, and drinking water systems. While conventional disinfection methods show limited efficacy, emerging technologies and materials, such as novel chemical systems and piezo-catalytic composites, offer promising avenues for reducing amoeba viability. Nevertheless, a significant gap persists in the early detection and monitoring of these pathogens. Future research should prioritize the development of integrated strategies under the One Health framework, linking human health with environmental and ecological dimensions, while advancing innovative vector control measures to limit transmission. Given the rising global incidence of amoeba-related diseases, there is an urgent need for more proactive public health surveillance and intervention efforts.

-

Key words:

- Amoebae /

- Public health /

- Water safety /

- Pathogen transmission /

- Trojan horse