-

Bananas (Musa spp.) are among the most consumed fruits globally and serve as a vital staple food and cash crop in many tropical and subtropical regions[1]. They rank as the fourth most important food crop worldwide, following rice, wheat, and maize, and are essential for food security and income generation in low-income, food-deficit countries[2]. Despite their economic and nutritional importance, banana production faces significant threats from diseases, notably Fusarium wilt, also known as Panama disease. This disease is caused by the soil-borne fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc), which infects the plant's vascular system, leading to wilting and eventual death. The most virulent strain, Tropical Race 4 (TR4), poses a severe threat as it affects a broad range of banana cultivars, including the widely cultivated Cavendish variety, which constitutes about 50% of global banana production[3]. TR4 is particularly concerning due to its persistence in the soil for decades and its resistance to chemical treatments[4]. The pathogen has spread to multiple countries across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, threatening both local consumption and international trade[5].

Traditional control measures for Fusarium wilt, such as chemical fungicides and soil fumigants, have proven largely ineffective against TR4[6]. The pathogen's resilience and the lack of effective chemical controls necessitate alternative management strategies[7]. While some resistant banana cultivars have been developed, they often lack the agronomic traits and consumer preferences associated with the Cavendish variety[8]. Biological control agents, including certain strains of Pseudomonas, Trichoderma, and endophytic fungi, have shown promise in suppressing Fusarium wilt under field conditions, achieving control rates of up to 79%[9]. However, the efficacy of these agents can vary depending on environmental conditions and microbial community dynamics[6].

Recent research has highlighted the critical role of the plant microbiome—the community of microorganisms associated with plant tissues—in enhancing plant health and disease resistance[10]. In bananas, the rhizosphere and endophytic microbiota have been shown to significantly improve plant development and suppress soil-borne pathogens like Foc[11]. These beneficial microbes can promote plant growth, enhance nutrient uptake, and induce systemic resistance against pathogens[12]. Understanding and harnessing the banana microbiome offer a promising avenue for sustainable disease management strategies.

This review aims to explore the role of the banana microbiome in suppressing Fusarium wilt, and to examine how microbial communities can be harnessed for sustainable disease management. The composition and function of the banana microbiome, mechanisms of microbiome-mediated disease suppression, and biotechnological approaches to engineer the banana microbiome for enhanced disease resistance will be discussed. By integrating current research findings, this review seeks to provide insights into microbiome-based strategies for combating Fusarium wilt in bananas.

-

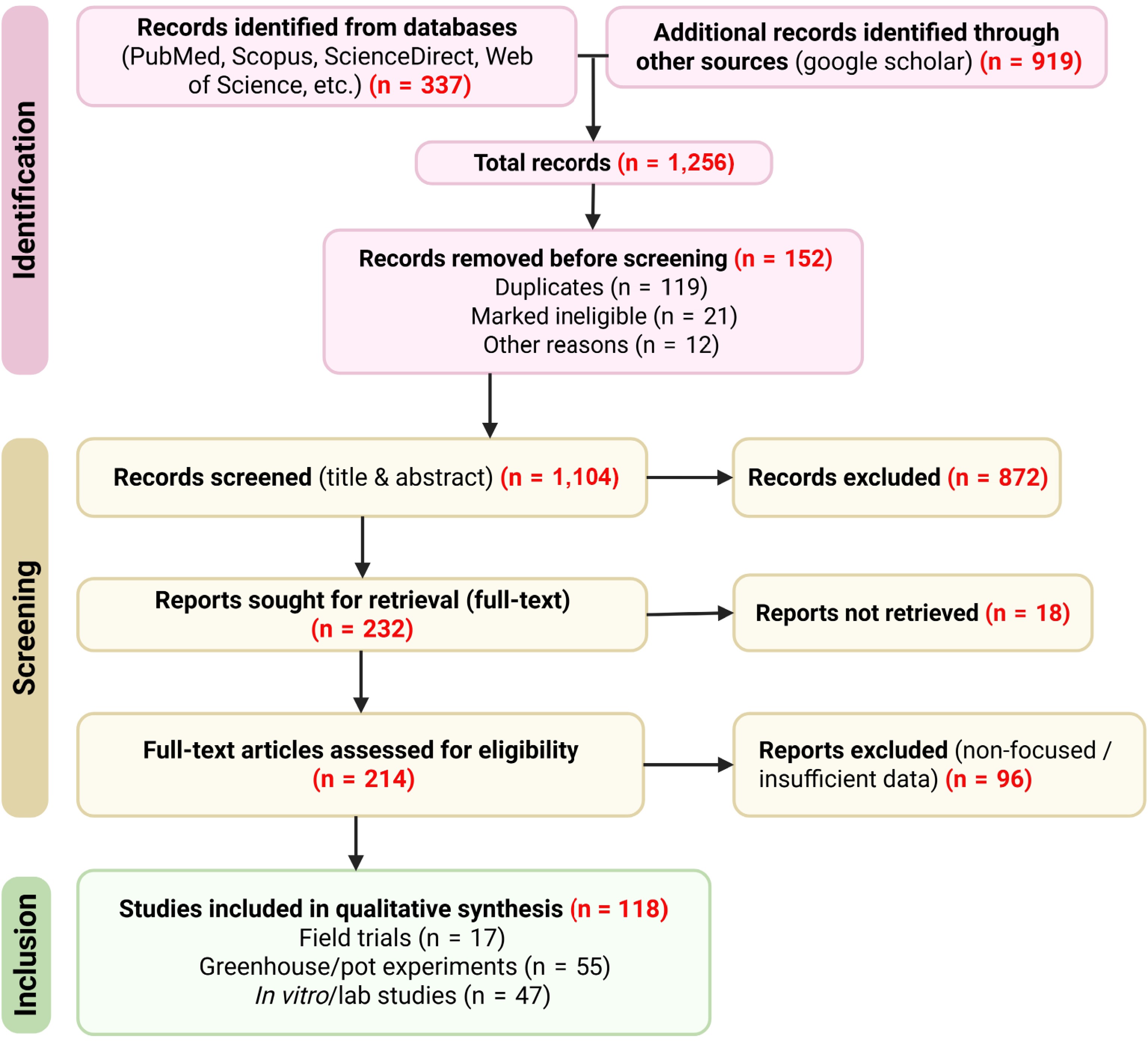

To ensure a comprehensive and unbiased overview of the banana microbiome and its role in suppressing Foc, a systematic literature search was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. Major databases including PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science were searched, complemented with Google Scholar to capture additional relevant studies. Search terms combined 'banana', 'Musa', 'Fusarium wilt', 'Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense', 'microbiome', 'endophytes', 'rhizosphere', 'biocontrol', 'biofertilizer', 'plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria', and 'mycorrhiza'. Records were screened in two stages. First, titles and abstracts were evaluated to exclude duplicates, reviews, and studies not directly addressing the banana microbiome or Fusarium wilt suppression. Second, full-text articles were assessed for eligibility based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) studies reporting experimental or field evidence of microbial associations with banana; (2) investigations on biocontrol or microbiome-based management strategies against Fusarium wilt; and (3) studies providing primary data on microbial mechanisms of disease suppression. Articles without sufficient methodological detail, unrelated microbial focus, or lacking relevance to banana-Fusarium wilt interactions were excluded. In total, 1,256 records were identified, of which 152 were removed prior to screening. After title and abstract screening, 232 articles were retained for full-text evaluation, resulting in 118 eligible studies. These comprised 17 field trials, 55 greenhouse or pot experiments, and 47 in vitro or laboratory studies (Table 1, Supplementary Tables S1, S2). The literature search included peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2025, covering recent advances in microbiome-mediated Fusarium wilt management in banana and related systems. The complete selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Field-based studies demonstrating microbiome-mediated suppression of Fusarium wilt of banana.

Microbiome Approach Key suppressive taxa/indicators Source of isolation Outcome Ref. Bacillus Biofertilizer amendment Sphingobium, Dyadobacter, Cryptococcus Rhizosphere Decreased F. oxysporum; sustained biocontrol effect [38] Piriformospora, Streptomyces Spatiotemporal application of biocontrol agents P. indica, S. morookaensis Roots, rhizosphere Enhanced growth, reduced Fusarium wilt incidence [39] Pseudomonas, Gemmatimonas, Sphingobium Crop rotation (chilli pepper–banana) Gemmatimonas, Penicillium, Mortierella Soil Decreased F. oxysporum; improved diversity [37] Aspergillus Green manure intercropping Aspergillus, reduced Fusarium Soil Reduced disease; changed fungal community [40] Pseudomonas, Bacillus Rotation crops (pepper/eggplant) Antagonistic core taxa Rhizosphere Legacy suppression of wilt [41] Burkholderia Pineapple–banana rotation + biofertilizer Burkholderia Soil Increased α-diversity; suppressed disease [42] Bacillus, Mortierella Microbial consortia application Functionally beneficial core/indicator OTUs Soil Reduced disease, enhanced microbial richness [43] Aspergillus fumigatus, Fusarium solani Pineapple residue incorporation A. fumigatus, F. solani Soil Reduced pathogen; increased antagonistic fungi [44] Pseudomonas spp. Endophyte and rhizosphere microbiome tracking Pseudomonas P8, S25, S36 Root, rhizosphere Suppressed pathogens, promoted beneficial microbes [45] Bacillus, Rhizosphere bacteria Consortia of native isolates Multiple Bacillus spp. Root, corm, rhizosphere Suppressed wilt; increased growth/yield [46] Bacillus High-throughput sequencing + isolate screening Chujaibacter, Bacillus, Sphingomonas Soil B. velezensis YN1910 effective biocontrol [47] Pseudomonas, Bacillus Soil metagenomics + greenhouse validation Pseudomonas enriched in suppressive soils Soil Confirmed suppressiveness via isolates [35] Pseudomonas, Trichoderma P. fluorescens and T. viride formulations Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf1, Trichoderma viride Tv-6 Rhizoplane of crops 80.6% disease reduction [48] Pseudomonas Powder/capsule formulations of P. fluorescens Pf1 Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf1 Rhizoplane of crops Increased yield; better than carbendazim [49] Pseudomonas Liquid P. fluorescens via drip irrigation Pseudomonas fluorescens 60% wilt reduction; 41%–89% nematode reduction [50] Trichoderma viride +

P. fluorescensSucker treatment + soil drenching Trichoderma viride + P. fluorescens Banana rhizosphere Effective combined control [36] Nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum EF-1α and IGS sequencing Nonpathogenic F. oxysporum Banana farm soil Evidence of horizontal gene transfer of pathogenicity genes [51] -

Banana plants host a wide array of microbial communities distributed across different plant compartments, including the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere[13]. The rhizosphere—the soil region directly influenced by root secretions—is a hotspot of microbial diversity and metabolic activity. Studies have shown that this zone is predominantly inhabited by bacterial phyla such as Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes, and fungal groups like Ascomycota and Basidiomycota[14]. The endosphere, comprising internal tissues like roots, corms, and pseudostems, supports endophytic microbes that often differ in structure and function from those in the surrounding soil. These endophytes can colonize banana plants asymptomatically and are integral to plant stress tolerance and immune modulation[12]. The phyllosphere, though less studied in banana, contains microorganisms residing on leaf surfaces that can impact photosynthesis, stress resilience, and resistance to foliar pathogens[15]. Together, these microbial habitats contribute to a dynamic plant–microbe interface essential for banana health and productivity.

Functional roles of beneficial microorganisms

-

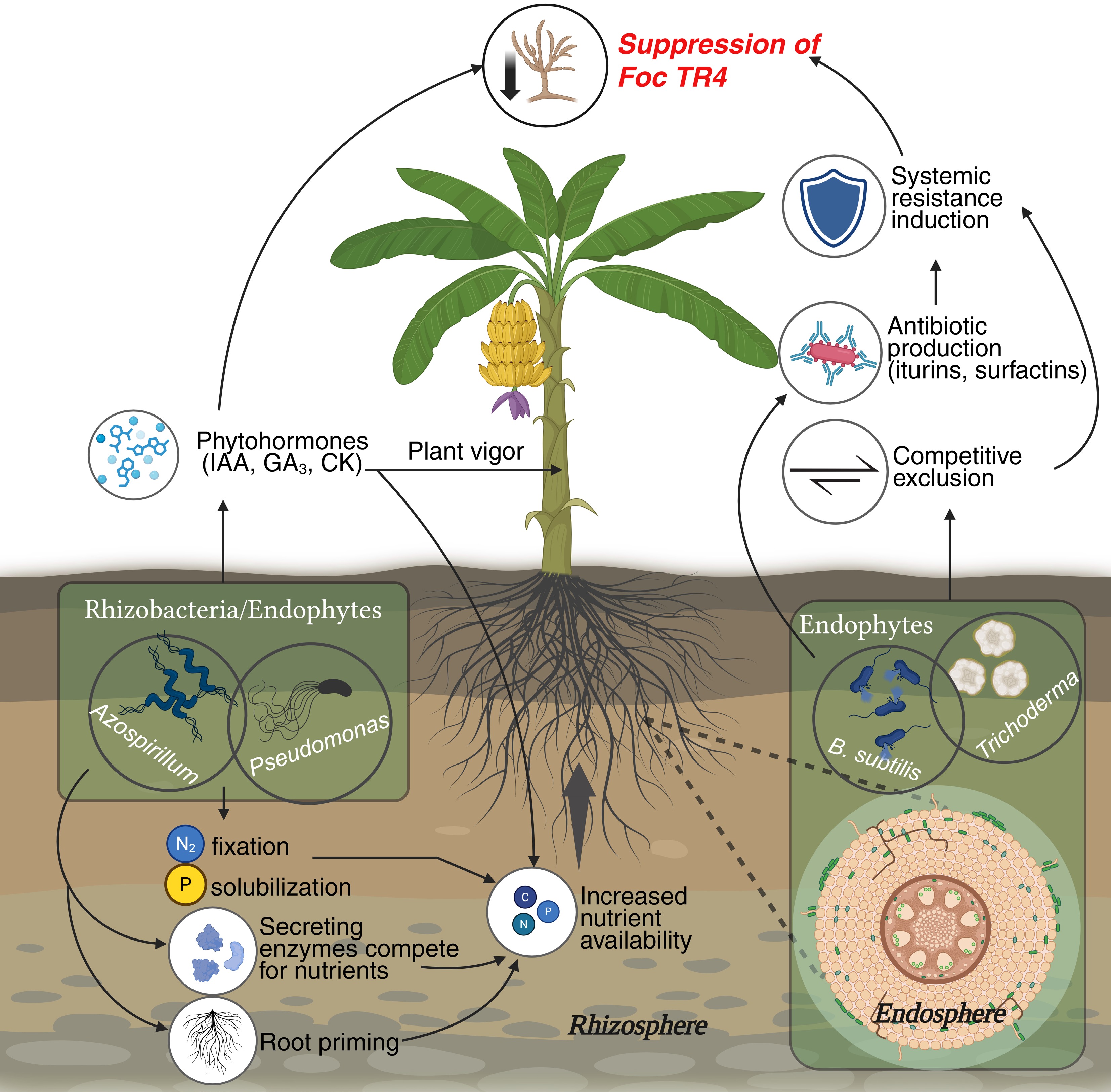

Beyond their presence, microbial communities play functional roles that directly support plant development and resilience. Many banana-associated microbes are involved in nutrient cycling, facilitating nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and mineral mobilization[16]. For instance, species of Azospirillum and Pseudomonas in the rhizosphere help convert atmospheric nitrogen into plant-usable forms, enhancing fertility and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers[17,18]. In addition, several rhizobacteria and endophytes act as plant growth promoters by producing phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellins, and cytokinins, which stimulate root growth and nutrient uptake[19]. Importantly, beneficial microbes also contribute to pathogen suppression. Through mechanisms like competitive exclusion, secretion of antibiotics (e.g., iturins, surfactins), and induction of systemic resistance, microbes such as Bacillus subtilis and Trichoderma spp. have been shown to mitigate Foc infections[20,21]. These ecosystem services highlight the banana microbiome's potential as a biological shield against biotic stressors. A holistic overview of the roles played by endosphere and rhizosphere microbes in the suppression of Foc TR4 is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of banana–microbiome interactions influencing Fusarium wilt resistance. Beneficial microbes such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Trichoderma colonize the rhizosphere and endosphere, enhancing nutrient uptake and triggering defense responses against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4 (Foc TR4). These interactions suppress pathogen growth through antibiosis, competition, biofilm formation, and activation of Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) in host tissues.

Factors shaping the microbial community structure

-

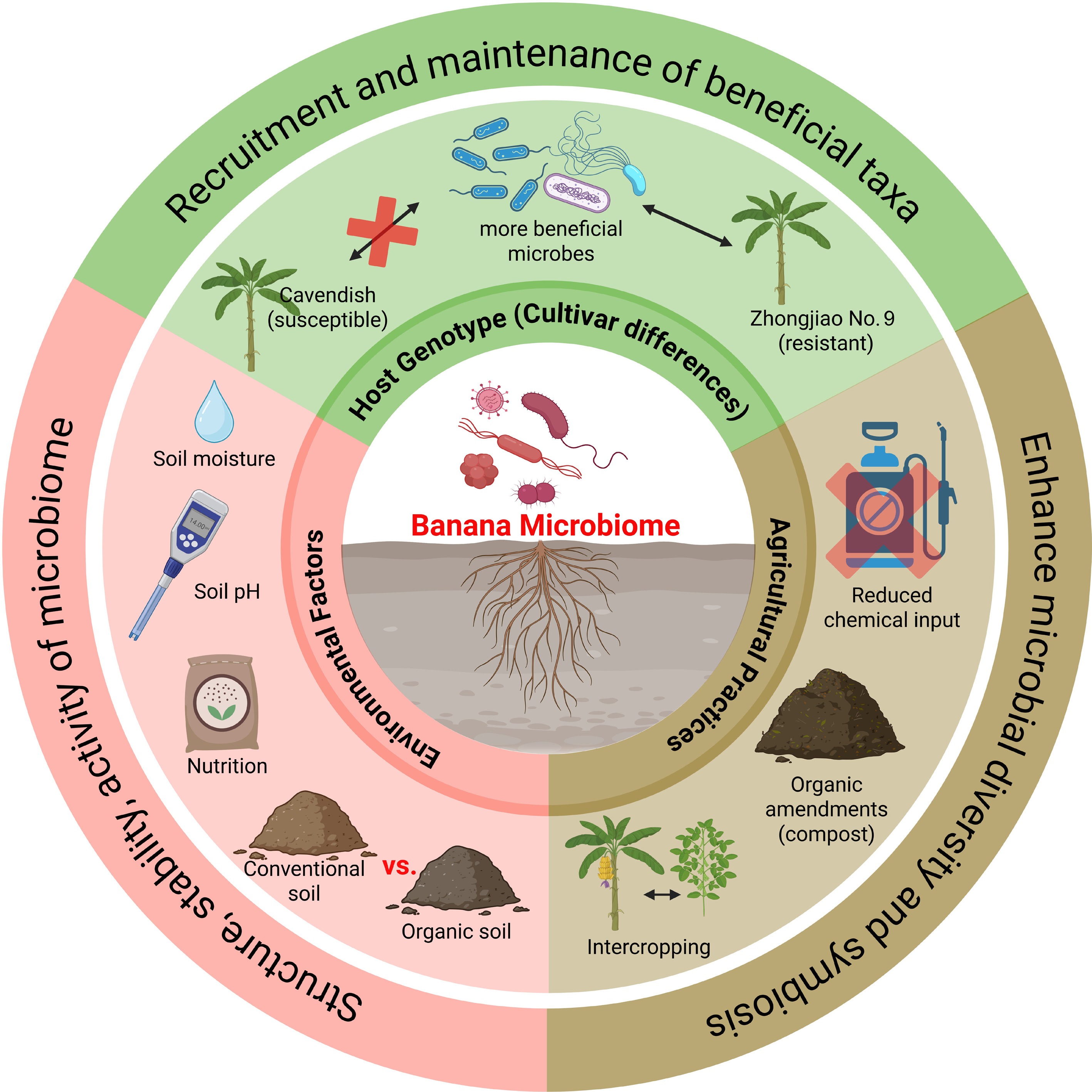

The composition and functionality of the banana microbiome are strongly influenced by host genotype, environmental conditions, and farming practices (Fig. 3). Banana cultivars differ in their ability to recruit and sustain beneficial microbial populations. For example, resistant varieties such as 'Zhongjiao No. 9' have been associated with a higher abundance of microbial taxa involved in disease suppression compared to susceptible varieties. Environmental factors—including soil pH, moisture, and nutrient status—further shape microbial communities, often determining their structure, stability, and activity[22]. Organic soils typically harbor more diverse and resilient microbial populations than conventionally managed soils, resulting in enhanced plant-microbe symbioses[23]. Additionally, agricultural management practices such as intercropping, organic amendments, and reduced chemical input positively affect microbial diversity and function.

Figure 3.

Determinants of banana microbiome composition and functionality. The banana microbiome is shaped by multiple interacting factors. Host genotype influences the recruitment and maintenance of beneficial microbial taxa, with resistant cultivars (e.g., Zhongjiao No.9) supporting more beneficial populations than susceptible ones (e.g., Cavendish). Environmental factors, including soil pH, moisture, nutrient availability, and soil management type (organic vs. conventional), strongly affect the structure, stability, and activity of microbial communities. Agricultural practices, such as reduced chemical inputs, organic amendments, and intercropping, further enhance microbial diversity and promote beneficial plant-microbe symbioses.

-

Beneficial microbes can outcompete Foc for colonization sites and essential nutrients in the rhizosphere and endosphere, effectively limiting pathogen establishment. Fast-growing genera such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus proliferate rapidly around banana roots, occupying niches that might otherwise be exploited by Foc[24]. For example, strains of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens have been shown to occupy ecological niches in the rhizosphere, outcompeting Foc for essential nutrients and attachment sites, thereby reducing pathogen establishment and proliferation[9]. This competitive exclusion is particularly effective when the microbial community is rich in copiotrophic species capable of rapidly utilizing root exudates[25].

Production of antifungal compounds

-

Many plant-associated microbes synthesize antifungal metabolites that directly inhibit the growth of Foc. For example, strains of Bacillus subtilis and Trichoderma harzianum have been shown to produce lipopeptides (e.g., iturins, fengycins), and peptaibols, respectively, that disrupt fungal membranes and suppress mycelial proliferation[20]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain Gxun-2, isolated from the banana rhizosphere, significantly inhibited Foc growth through the secretion of antimicrobial compounds, as demonstrated both in vitro and in planta[26]. In vitro and in planta assays have demonstrated significant inhibition zones and reductions in disease severity following the application of such microbial antagonists[27]. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) produced by rhizobacteria, such as hydrogen cyanide and 2,3-butanediol, also exhibit strong antifungal activity[28].

Induction of host systemic resistance (ISR)

-

Certain beneficial microbes can prime the banana plant's immune system through ISR, thereby enhancing resistance to Foc without directly targeting the pathogen. Rhizosphere-associated Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens activate ISR via jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling pathways, leading to the upregulation of defense-related genes[29]. Endophytic strains of Bacillus velezensis have been shown to upregulate defense-related enzymes such as peroxidases, chitinases, and β-1,3-glucanases while modulating ethylene signaling pathways via ACC deaminase activity[30]. This priming effect results in faster and stronger defense responses upon pathogen attack, including the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), pathogenesis-related proteins, and callose deposition[31,32].

Biofilm formation and root colonization

-

Biofilm formation by beneficial microbes enhances their persistence and protective functions in the rhizosphere. Bacillus velezensis, for instance, forms dense biofilms on banana root surfaces, creating a physical and biochemical barrier that impedes pathogen access[33]. These biofilms not only serve as a frontline defense against pathogen ingress but also facilitate horizontal gene transfer and cooperation among microbial consortia, further enhancing community resilience and antifungal activity[34].

-

The accumulated evidence strongly supports the concept that the banana microbiome can be functionally harnessed through bioinoculants (microbial formulations used either as biofertilizers or biocontrol agents) to mitigate Fusarium wilt. Rather than relying on single microbial agents or isolated agronomic tactics, emerging strategies focus on system-level interventions that promote the long-term establishment of suppressive microbial communities[9]. Field-based validation of microbial consortia—including strains of Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma, and others—has shown that microbiome assembly can be steered toward disease suppression through integrated practices[35,36]. These practices include targeted applications of indigenous microbes, crop rotation with hosts that support antagonistic taxa, and organic inputs that serve as prebiotics for beneficial organisms[37].

Additionally, adaptive microbiome management strategies are being refined to address site-specific constraints. This includes the use of regionally adapted biofertilizers, minimal tillage to preserve microbial niches, and phased microbiome transplantation approaches based on suppressive soil indicators[35]. Importantly, these interventions must be context-specific, as microbiome composition and functionality are influenced by cultivar genotype, soil type, and climatic conditions.

Field trials

-

Field studies have demonstrated the potential of microbiome manipulation to suppress Fusarium wilt of banana through diverse strategies. Several biofertilizer-based and cropping-system approaches have produced consistent disease reductions under field conditions. For instance, biofertilizers amended with Bacillus were shown to enrich beneficial taxa such as Sphingobium, Dyadobacter, and Cryptococcus in the rhizosphere, leading to sustained suppression of F. oxysporum[38]. Similarly, spatiotemporal applications of beneficial endophytes, including the root endophyte Piriformospora indica and the actinobacterium Streptomyces morookaensis, enhanced plant growth and reduced Fusarium wilt incidence[39]. Crop rotation practices also influenced microbiome composition. Rotating banana with chili pepper shifted soil communities toward Gemmatimonas, Penicillium, and Mortierella, which decreased Fusarium abundance and improved overall microbial diversity[37]. Intercropping with green manure further altered fungal communities, favoring Aspergillus over pathogenic Fusarium[40]. Rotations with pepper or eggplant enriched antagonistic rhizosphere taxa such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus, creating a lasting suppressive effect in subsequent banana crops[41]. Combining pineapple–banana rotation with biofertilizers increased soil α-diversity and populations of Burkholderia, which correlated with disease suppression[42]. The use of microbial consortia has also proven effective. Microbial consortia, such as those containing Bacillus and Mortierella, introduced functionally beneficial taxa that reduced Fusarium wilt while enhancing soil microbial richness[43]. Amendments such as pineapple residue promoted antagonistic fungi, including Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium solani, thereby lowering pathogen loads[44]. Targeted inoculation with Pseudomonas endophytes (strains P8, S25, S36) suppressed pathogens and enriched beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere[45]. Native Bacillus consortia applied to roots, corms, and rhizospheres not only controlled wilt but also improved yield performance[46]. High-throughput screening further identified Bacillus velezensis YN1910 as a potent biocontrol strain[47]. Metagenomic analyses supported these findings. Metagenomic analyses confirmed the suppressive role of Pseudomonas-enriched soils[35], and formulated biocontrol agents—such as Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf1 and Trichoderma viride Tv-6—achieved 60%–80% reductions in wilt incidence, often outperforming chemical fungicides[48−50]. Combined treatments of Trichoderma and Pseudomonas further enhanced control[36], while genetic studies revealed horizontal transfer of pathogenicity genes among F. oxysporum strains, underscoring the need for microbiome-based management to counteract pathogen evolution[51]. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of tailored microbial interventions, leveraging crop rotations, consortia, and bioformulations to build resilient, disease-suppressive agroecosystems (Table 1).

Greenhouse/pot experiments

-

Controlled greenhouse and pot trials have provided strong evidence that diverse microbial taxa can suppress Foc and promote banana growth (Supplementary Table S1). Beneficial endophytes such as Enterobacter, Kosakonia, Klebsiella, Burkholderia, and Serratia improved resistance through antifungal activity and rhizosphere enrichment[52−54]. Pseudomonas strains, notably P. fluorescens and P. aeruginosa, consistently reduced wilt incidence by inducing defense enzymes, detoxifying fusaric acid, and producing antifungal metabolites; their co-formulation with Bacillus further enhanced protection and yield[55,56].

Bacillus species such as B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens showed broad biocontrol potential, reducing disease by up to 68% via root colonization, lipopeptide production, and defense induction[57]. Streptomyces isolates also provided effective control through antifungal metabolite production and systemic resistance activation[58,59].

Among fungi, Trichoderma spp. remain the most successful biocontrol agents, achieving up to complete suppression in greenhouse trials and significantly reducing corm discoloration under field conditions[60,61]. Nonpathogenic Fusarium strains and endophytes such as Acremonium and Penicillium likewise induced host defenses and reduced wilt severity[62,63].

Mycorrhizal fungi (Glomus, Gigaspora) alleviated symptoms and improved yield, particularly when combined with Trichoderma or Pseudomonas[64,65]. Microbiome-based approaches revealed that repeated biofertilizer application or co-inoculation with diverse plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) reshaped rhizosphere communities toward suppressiveness[66].

Molecular studies further showed that beneficial microbes like T. asperellum upregulate plant defense genes, while 'vaccine' treatments with inactivated Foc mycelia enhance enzyme activity and resistance[67,68].

In vitro/lab studies

-

Extensive in vitro studies have identified diverse banana-associated microbes capable of suppressing Foc (Supplementary Table S2). Trichoderma species remain the most studied and effective antagonists, showing strong inhibition through mycoparasitism, metabolite production, and enzyme secretion. Strains such as T. reesei, T. viride, T. harzianum, and T. asperellum have achieved up to complete growth inhibition, with genetic studies confirming key roles for enzymes and regulatory genes in antifungal activity[69].

Actinobacteria, particularly Streptomyces spp., also display potent antagonism via production of antifungal metabolites such as fungichromin and antibiotic 210-A, with several strains maintaining stability under thermal or UV stress[70,71].

Among bacterial antagonists, Bacillus species—especially B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens—are consistently effective, producing enzymes, lipopeptides, and volatile compounds that inhibit Foc growth and spore germination[72]. Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. aeruginosa also exhibit strong inhibition, often enhanced when co-applied with resistance inducers such as β-aminobutyric acid[73].

Other microbes, including Serratia marcescens, Brevibacillus brevis, and Bacillus methylotrophicus demonstrate complementary antifungal activity. Fungal endophytes like Talaromyces, Eutypella, and Penicillium species, along with volatile-producing bacterial endophytes, further broaden the antifungal spectrum[74,75].

Emerging taxa such as Micromonospora, Tsukamurella, and Herbaspirillum from varied environments highlight the unexplored microbial diversity with potential to combat Foc[76,77].

-

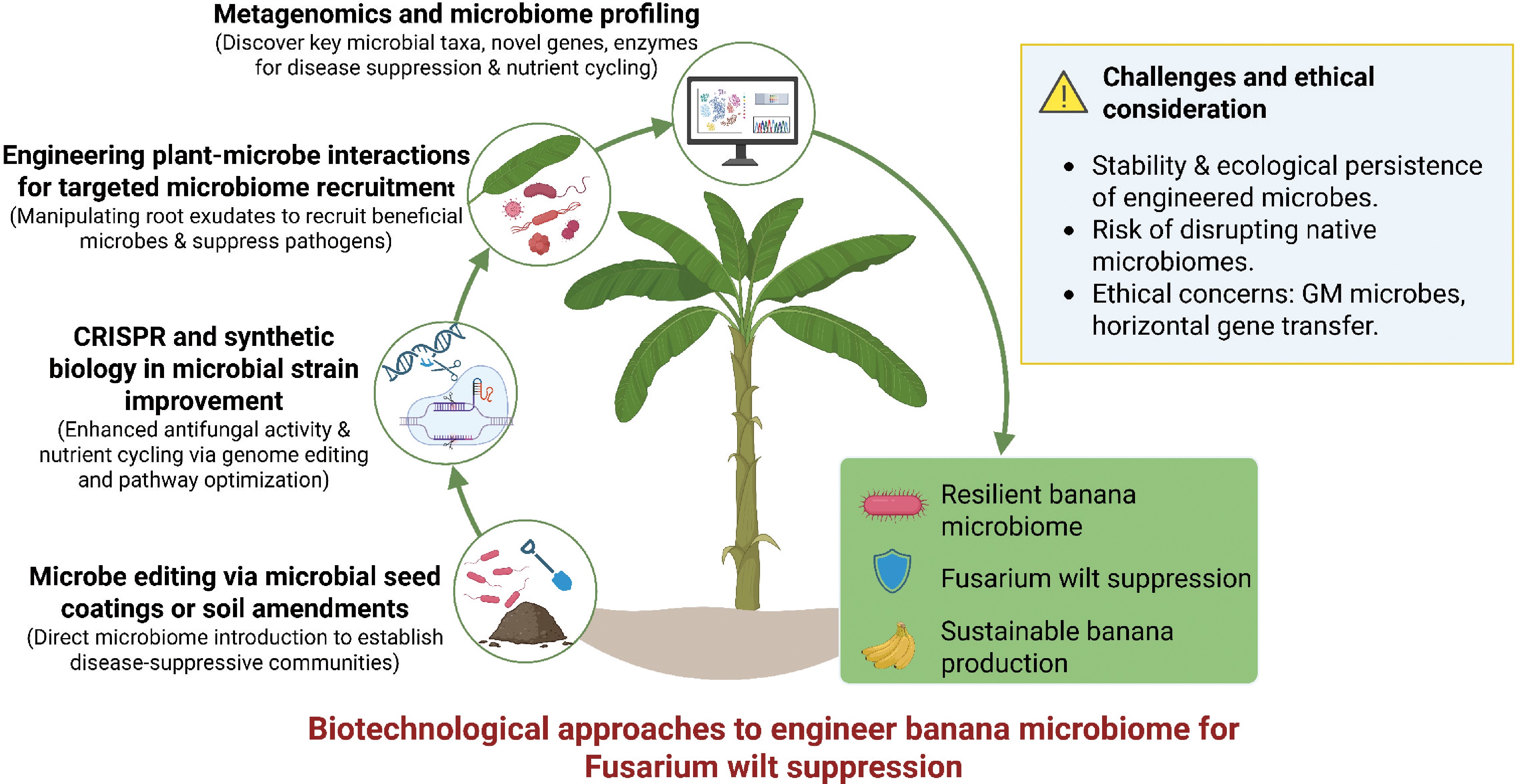

Biotechnological approaches offer promising avenues for engineering the banana microbiome to combat Fusarium wilt. These strategies leverage advancements in metagenomics, synthetic biology, and plant-microbe interaction studies to enhance the banana's natural defenses and promote sustainable production[78] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Biotechnological strategies for engineering the banana microbiome to combat Fusarium wilt. Metagenomics, CRISPR/synthetic biology, plant–microbe interaction engineering, and microbiome editing strategies converge to enhance disease resistance, suppress Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, and promote sustainable banana production, while addressing ecological and ethical considerations.

Metagenomics and microbiome profiling

-

Metagenomics and microbiome profiling are essential for identifying key microbial players in the banana endosphere and rhizosphere[78]. By employing high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rDNA, ITS, and other marker genes, researchers can characterize the bacterial and fungal communities associated with both healthy and Foc-infected banana plants[45,78]. These analyses reveal the composition, diversity, and functional potential of the banana microbiome, highlighting specific microbial taxa that are enriched in disease-suppressive soils or exhibit antagonistic activity against Foc[45,79]. For example, Pseudomonas spp. have been identified as key contributors to soil suppressiveness against banana Fusarium wilt[79]. Metagenomic studies can also uncover novel genes and pathways involved in disease suppression, nutrient cycling, and plant growth promotion, providing a foundation for targeted microbiome engineering strategies[80,81]. The use of metaproteomics, metatranscriptomics, and metagenomics can enhance lignolytic enzyme production by targeting lignin-degrading microbes[82].

CRISPR and synthetic biology in microbial strain improvement

-

CRISPR-Cas9 technology and synthetic biology approaches offer powerful tools for improving microbial strains with desirable traits for banana microbiome engineering[80]. CRISPR-Cas9 enables precise genome editing of beneficial bacteria and fungi, allowing researchers to enhance their antifungal activity, stress tolerance, and ability to colonize the banana rhizosphere[37,80]. For example, genes involved in the production of antifungal compounds, such as phenazines or pyrrolnitrin, can be overexpressed in Pseudomonas strains to enhance their biocontrol activity against Foc[79,83]. Similarly, synthetic biology can be used to engineer microbial strains with improved nutrient cycling capabilities, such as enhanced nitrogen fixation or phosphate solubilization, promoting banana growth and health[80]. By optimizing enzyme pathways, synthetic biology can predict the most appropriate pathway and improve enzyme activity[82].

Engineering plant-microbe interactions for targeted microbiome recruitment

-

Engineering plant-microbe interactions offers a promising strategy for targeted recruitment of beneficial microbes to the banana rhizosphere[42]. Plants release a variety of root exudates, including sugars, organic acids, and amino acids, which can selectively attract or repel specific microbial taxa[42,84]. By manipulating the composition of root exudates through genetic engineering or chemical elicitation, researchers can create a rhizosphere environment that favors the colonization of beneficial microbes and suppresses the growth of Foc[42,85]. For instance, the plant elicitor Isotianil can be used to induce resistance to banana Fusarium wilt[85]. Furthermore, understanding the spatial configuration of plant-microbe interactions can provide insights into metabolic-associated organization of these interactions[42].

Microbiome editing via microbial seed coatings or soil amendments

-

Microbiome editing via microbial seed coatings or soil amendments represents a direct approach to introduce beneficial microbes into the banana rhizosphere and establish a disease-suppressive microbiome[86]. Microbial seed coatings involve applying a mixture of beneficial bacteria and fungi to banana seeds or seedlings before planting, providing a head start for microbiome establishment[86,87]. Soil amendments, such as compost, biochar, or biofertilizers, can also be used to enrich the soil with beneficial microbes and improve soil health, creating a more favorable environment for banana growth and disease suppression[40,86]. Pineapple-banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application has shown success in suppressing banana Fusarium wilt disease[86]. Biochar, when combined with microbial inoculants, can also suppress plant diseases[88]. These interventions aim to create resilient microbial communities that can protect banana plants from Foc infection and promote sustainable production.

Challenges and ethical considerations

-

While microbiome engineering holds great promise for combating banana Fusarium wilt, several challenges and ethical considerations must be addressed[37,81,89]. One major challenge is ensuring the ecological persistence and stability of engineered microbes in the banana rhizosphere[81,89]. The banana microbiome is a complex and dynamic ecosystem, and introduced microbes may face competition from native microbes, or be negatively impacted by environmental factors[81,84]. Another concern is the potential disruption of native microbiomes and unintended consequences on soil health and ecosystem functioning[81,89]. Extensive field trials and ecological risk assessments are necessary to evaluate the long-term impacts of microbiome engineering strategies and ensure their safety and sustainability[81,89]. Additionally, ethical considerations surrounding the use of genetically modified microbes and the potential for horizontal gene transfer must be carefully evaluated[37,80]. A balanced approach that integrates agricultural innovation with ecological stewardship is essential to harness the full potential of microbiome engineering for sustainable banana production[42,89].

-

Engineered microbial consortia hold significant promise for revolutionizing banana production, building upon their established efficacy in other staple crops such as maize and wheat. In maize cultivation, multi-strain systems have demonstrated success in enhancing crop yield through functional complementarity. For instance, consortia containing Pseudomonas putida P7 and Paenibacillus favisporus B30, or Pseudomonas putida P45 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens B17, have been shown to improve maize yield under sub-humid rainfed conditions[90]. Beyond direct yield benefits, these microbial communities can influence various plant defense mechanisms and metabolic reprogramming, as observed in studies where microbial biostimulants modulated photoprotection, structural reinforcement, defense priming, systemic metabolic adjustments for growth and defense, and hormonal signaling in maize under field conditions[91]. Similarly, in wheat, beneficial rhizobacteria like Pseudomonas simiae WCS417 have been extensively studied for their ability to promote plant growth, enhance ISR, and provide biological control against pathogens, thereby contributing to increased wheat yields and disease suppression[92]. The effectiveness of such multi-strain consortia stems from their capacity to leverage diverse microbial functions, including nitrogen fixation, which is crucial for nutrient availability[93], antifungal activity, and immune priming, to achieve stable performance against diseases and improve overall crop productivity[92,94]. For example, Bacillus subtilis CF-3 produces volatile organic compounds with antifungal activity against pathogens like Monilinia fructicola, protecting fruit crops from disease[94]. The plant endo-microbiome, a diverse community of microorganisms living within plant tissues, further contributes to improved germination, vegetative growth, symbiosis nodule formation, host defense, and stress management, offering a broad spectrum of benefits for plant health[95].

Translating this proven potential to banana production, however, faces distinct challenges despite the technical feasibility. Long-term agricultural practices in banana fields, particularly the intensive use of inorganic fertilizers, can lead to soil acidification and an imbalance in microbial communities, favoring pathogenic bacteria such as Xanthomonadaceae and Foc, which causes banana wilt disease. This highlights a critical need for beneficial microbial interventions. While microbial inoculants can significantly mitigate soil degradation and enhance disease resistance, economic barriers remain substantial. High costs associated with the isolation, identification, and engineering of key microbial species, followed by their formulation and application, can be prohibitive for many farmers, especially in tropical regions where banana is predominantly grown[96,97]. Logistical difficulties in sourcing and distributing these specialized microbial products across diverse geographical areas further complicate widespread adoption. Regulatory inconsistencies across different jurisdictions also pose a significant hurdle, creating complex pathways for product approval and market entry[98]. Crucially, building farmer trust is paramount, as the success of microbiome-based strategies hinges on the consistent delivery of tangible benefits under variable field conditions. Farmers need reliable, context-specific products that demonstrably improve yields, reduce disease incidence, and enhance crop resilience. To enable successful scaling of microbiome-based strategies in banana production, supportive policy and logistical frameworks are essential, including subsidies to offset initial costs, streamlined regulatory pathways, robust extension services to educate farmers on proper application and expected benefits, and investments in local infrastructure for the production and distribution of microbial inoculants[99].

For banana farmers in developing regions, microbiome-based approaches offer a feasible and environmentally sustainable alternative to chemical control and resistant cultivar replacement. Locally produced bioinoculants and organic soil amendments can reduce input costs while improving soil health and disease resilience. Strengthening farmer awareness, extension support, and low-cost microbial formulation capacity will be essential for translating research advances into on-farm benefits and ensuring long-term adoption of microbiome-guided management strategies.

-

Despite the promising advances in microbiome-based disease management, several key challenges must be addressed before such strategies can be reliably deployed in large-scale banana production systems. One of the most pressing issues is the 'context-dependence of microbiome functionality'. The performance of bioinoculants and microbial consortia is often inconsistent across environments due to variation in soil physicochemical properties, climate, plant genotype, and existing microbial communities[100,101]. In banana systems, strains that show strong antagonistic activity under greenhouse or laboratory conditions often exhibit diminished efficacy in the field, underscoring the need for location-specific validation and formulation optimization[43].

Another major barrier is the 'lack of standardization in microbial product development'. The commercialization of bioinoculants suffers from variable strain quality, short shelf life, and regulatory complexity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where banana is a major crop[102]. Regulatory frameworks for microbial products differ widely across regions and often do not account for microbiome-level interventions, such as consortia or microbiome transplantation. Establishing internationally harmonized guidelines for microbial registration, safety, and field efficacy is critical for the wider adoption of microbiome-based technologies[17].

A further challenge lies in the 'ecological complexity and potential unintended consequences of manipulating microbiomes'. Introducing non-native microbes or heavily engineering existing ones could disrupt native microbial networks or select for resistant pathogens over time[103,104]. Although many microbial inoculants are generally regarded as safe, their long-term ecological impacts remain poorly understood, especially under polycropping or in biodiverse tropical systems like banana plantations[105].

The 'integration of plant breeding with microbiome science' remains underdeveloped but offers great potential. Most current breeding programs for banana prioritize disease resistance and agronomic traits, but few consider the plant's capacity to recruit and maintain beneficial microbiomes. Recent studies suggest that host genotype plays a crucial role in shaping rhizosphere and endosphere microbiota, with implications for disease resilience[106]. Incorporating microbiome-assembly traits into breeding targets could yield cultivars better suited to microbiome-assisted disease suppression. Looking ahead, future research should prioritize longitudinal field studies to evaluate the stability, adaptability, and legacy effects of microbiome interventions over multiple growing seasons. Most current studies are limited to short-term pot or greenhouse trials, which do not capture the dynamics of complex agroecosystems. Moreover, there is a need for more functional validation of key microbial taxa and genes identified through omics approaches. Integrating metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and ecological modeling will be essential to decipher the causal relationships between microbiome composition and disease outcomes[107,108].

The development of precision agricultural tools—such as microbiome diagnostics, microbial biosensors, and decision-support systems—could help tailor microbiome interventions to specific field conditions[109]. These innovations will be especially valuable in smallholder farming systems, where resources for intensive management are limited but disease pressure is high[110].

A consistent pattern in biocontrol research is that isolates of Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. tend to deliver more reliable outcomes than many other genera. For Bacillus, the ability to form endospores confers resilience under fluctuating soil conditions, and many strains produce a suite of lipopeptides (e.g., surfactin, fengycin, iturin) plus robust biofilm-forming abilities, which together promote stable root colonization and persistence[111]. For Pseudomonas, rapid rhizosphere colonization, production of siderophores and key antifungal secondary metabolites (such as 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol, phenazines), and induction of systemic resistance in the host plant give them a competitive advantage in root-microbe–pathogen interactions[112].

In contrast, many biocontrol trials fail to translate into consistent field-level success because of three inter-related constraints: (1) poor or inconsistent colonization of the target niche; (2) suppression of the inoculant's activity by the native soil microbiome or by unfavorable abiotic conditions (soil pH, temperature, moisture, nutrient status) that reduce metabolite production or root association; and (3) variability in formulation, carrier stability, timing and method of application which leads to unpredictable outcomes when scaling from controlled environments to complex field settings[113].

Recent research indicates microbial consortia (i.e., multiple strains or species) outperform single-strain applications. For example, a study on tomato deploying compatible microorganisms demonstrated that while individual strains may suppress one pathogen type, consortia achieved broad-spectrum control, maintained effectiveness across application methods, and reached protection levels equal to the best performing single strain[111]. In another field study with soybean, bacterial consortia more significantly modulated rhizosphere functional pathways, plant physiology, and yield than single inoculants[114]. The benefits of consortia derive from functional complementarity (e.g., combining nutrient-mobilisers, antibiosis producers, and ISR activators), ecological resilience (redundancy ensures at least one member remains active under adverse conditions), and synergistic interactions (biofilm co-formation, cross-feeding, niche expansion). Altogether, this evidence underscores the value of multi-strain or microbiome-based formulations over single-agent approaches when the goal is field-scale, stable disease suppression.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in understanding and exploiting the banana microbiome for disease control, realizing its full potential will require a multidisciplinary effort that bridges microbial ecology, plant breeding, biotechnology, agronomy, and policy. Building resilient, microbiome-informed agroecosystems offers a promising pathway toward sustainable management of Fusarium wilt and broader agricultural sustainability.

-

Fusarium wilt remains a major threat to global banana cultivation, with current control strategies offering limited and often unsustainable solutions. Growing evidence highlights the banana microbiome as a vital, yet underexploited, component of disease suppression. Beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere and endosphere—particularly taxa like Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Trichoderma—play crucial roles in reducing disease severity through diverse mechanisms. Practical interventions, including bioinoculants, organic amendments, intercropping, and microbiome transplantation, have shown promise in shifting microbial communities toward disease-suppressive states. Advances in metagenomics, synthetic biology, and microbiome-assisted breeding further expand the potential to engineer plant–microbe interactions for enhanced resistance. Importantly, microbiome-based strategies can complement, rather than compete with, traditional resistant-cultivar breeding programs. Integrating host genetic resistance with beneficial microbial consortia could stabilize defense expression under field variability and enhance the durability of resistance over time. However, realizing this potential requires overcoming context-specific variability, regulatory hurdles, and knowledge gaps in field-scale applications. Harnessing the banana microbiome through integrative, science-based approaches offers a sustainable path forward in the fight against Fusarium wilt. Continued research and innovation will be key to translating this potential into resilient, microbiome-informed banana production systems.

The authors express their gratitude to the funding agencies and projects that supported this work, including the National Key Research and Development Program (2024YFD1401103), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (Guike AB25069296), the project of the National Key Laboratory for Tropical Crop Breeding (SKLTCBQN202511 and NKLTCB202301), the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2023XDNY179), Hainan Province Youth Fund (324QN319), and the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-31).

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ali MM, Li X, Liu J; literature review: Ali MM, Su Z, Cheng X; draft manuscript preparation: Ali MM and Su Z; critical revision: Zheng Y, Zhang J, Li X, Liu J. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Muhammad Moaaz Ali, Zuxiang Su

- Supplementary Tables S1 Microbial taxa with demonstrated Fusarium wilt-suppressive effects in banana under greenhouse/pot experiments.

- Supplementary Table S2 Representative in vitro and laboratory-based studies identifying microbial taxa with antagonistic activity against Foc, the causal agent of Fusarium wilt in banana.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ali MM, Su Z, Cheng X, Zheng Y, Zhang J, et al. 2025. The banana microbiome: a hidden ally for sustainable management of Fusarium wilt. Fruit Research 5: e043 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0036

The banana microbiome: a hidden ally for sustainable management of Fusarium wilt

- Received: 24 September 2025

- Revised: 25 October 2025

- Accepted: 04 November 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Fusarium wilt, caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4 (Foc TR4), remains one of the most devastating threats to global banana cultivation. Conventional management strategies, including chemical treatments and resistant cultivars, have shown limited efficacy and scalability. Emerging evidence highlights the banana microbiome—comprising diverse bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere—as a critical ally in suppressing Foc through mechanisms such as competitive exclusion, antibiosis, biofilm formation, and systemic resistance induction. This review synthesizes recent findings on microbiome-mediated disease suppression, emphasizing the functional roles of key microbial taxa like Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Trichoderma that contribute to natural disease resistance. It also explores innovative strategies for harnessing these microbes via bioinoculants, crop rotation, organic amendments, and microbiome-based management. Advances in metagenomics and microbial community analysis offer promising tools to build disease-resilient agroecosystems. However, field variability, regulatory constraints, and ecological complexities remain key challenges. Overall, this review highlights how integrating ecological understanding with practical microbiome applications can support sustainable management of Fusarium wilt in banana systems.