-

Plant tissue culture and micropropagation techniques[1] exploit the totipotency of plant cells, enabling rapid propagation of organs, tissues, cells, or protoplasts under sterile conditions through controlled environmental factors[2]. Orchidaceae is one of the largest plant families in the world[3], accounting for over 90% of CITES-protected species[4]. Therefore, research on orchid tissue culture and rapid propagation holds significant scientific and societal value for orchid conservation[5], biotechnology, ecological protection, economic development, and cultural heritage[6,7].

First, orchid tissue culture and micropropagation technologies effectively overcome limitations of natural reproduction and enable efficient production[8]. Research shows that through sterile seeding (non-symbiotic germination[9]) or explant culture, millions of seedlings can be obtained within a few months, enhancing propagation efficiency by over a hundred times. For example, Phalaenopsis can be mass-produced through tissue culture, with an annual production exceeding hundreds of millions of plants[10]. Secondly, wild populations of traditional precious medicinal species such as D. officinale, Gastrodia elata, and Bletilla striata are facing depletion due to over harvesting[11]. Tissue culture technology has enabled the production of these medicinal orchids to replace wild collection, ensuring a stable supply of traditional medicinal raw materials[12]. Finally, orchids are central to the global ornamental plant trade, with an annual market value exceeding

${\$} $ Bibliometrics[15] integrates mathematics, statistics, and computational techniques to quantitatively analyze literature, aiming to uncover patterns in knowledge production, dissemination, and utilization, assess academic impact, predict disciplinary trends, and optimize knowledge management[16]. Its core task is to extract hidden patterns from literature through data modeling, providing support for scientific decision-making and resource management. CiteSpace[17], developed by Dr. Chaomei Chen's team at Drexel University, is a specialized tool for scientific literature visualization and analyzing knowledge networks[18]. It is widely used to identify research hotspots, developmental trends, collaboration networks, and knowledge structures[19]. Focusing on global research hotspots and trends in orchid tissue culture and micropropagation, including publication volume, contributing countries, keywords, and journal distribution. CiteSpace supports co-occurrence analysis of authors, institutions, countries, and keywords; co-citation analysis of literature, authors, and journals; bibliographic coupling; and detection of emerging[20]. This study employs CiteSpace to analyze literature from the Web of Science (WoS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases, focusing on global research hotspots and trends in orchid tissue culture and micropropagation, including publication volume, contributing countries, keywords, and journals provides a comprehensive summary reflection for future researchers working on orchid tissue culture.

-

This study retrieved journal articles published between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2025, from the WoS Core Collection and CNKI databases (excluding newspapers and conference papers). Advanced searches were conducted using Chinese keywords '兰科植物' '兰花' (Orchidaceae, orchids), and '组织培养和快速繁殖技术' (tissue culture and rapid propagation technology) for CNKI databases, and English keywords 'orchids', 'Orchidaceae', 'tissue culture technology', and 'rapid propagation technology' for WoS. Each record included the article title, authors, publication year, keywords, and other metadata. After filtering out irrelevant entries, 727 valid CNKI journal articles (exported in RefWorks format), and 560 valid WoS articles (exported as plain text files) were obtained. These datasets were then visualized using CiteSpace.

Data analysis and visualization

-

CiteSpace was used for literature visualization and statistical analysis of publication volume and high-frequency keywords. Visualization parameters were set as follows: time slicing from January 1, 2000 to June 30, 2025 with 1-year intervals; node selection based on the g-index; network size adjusted via the scaling parameter * k * (set to * k * = 10 for CNKI, and * k * = 15 for WoS to ensure comprehensive node representation). Cluster analysis was performed using the likelihood rate (LLR) algorithm.

-

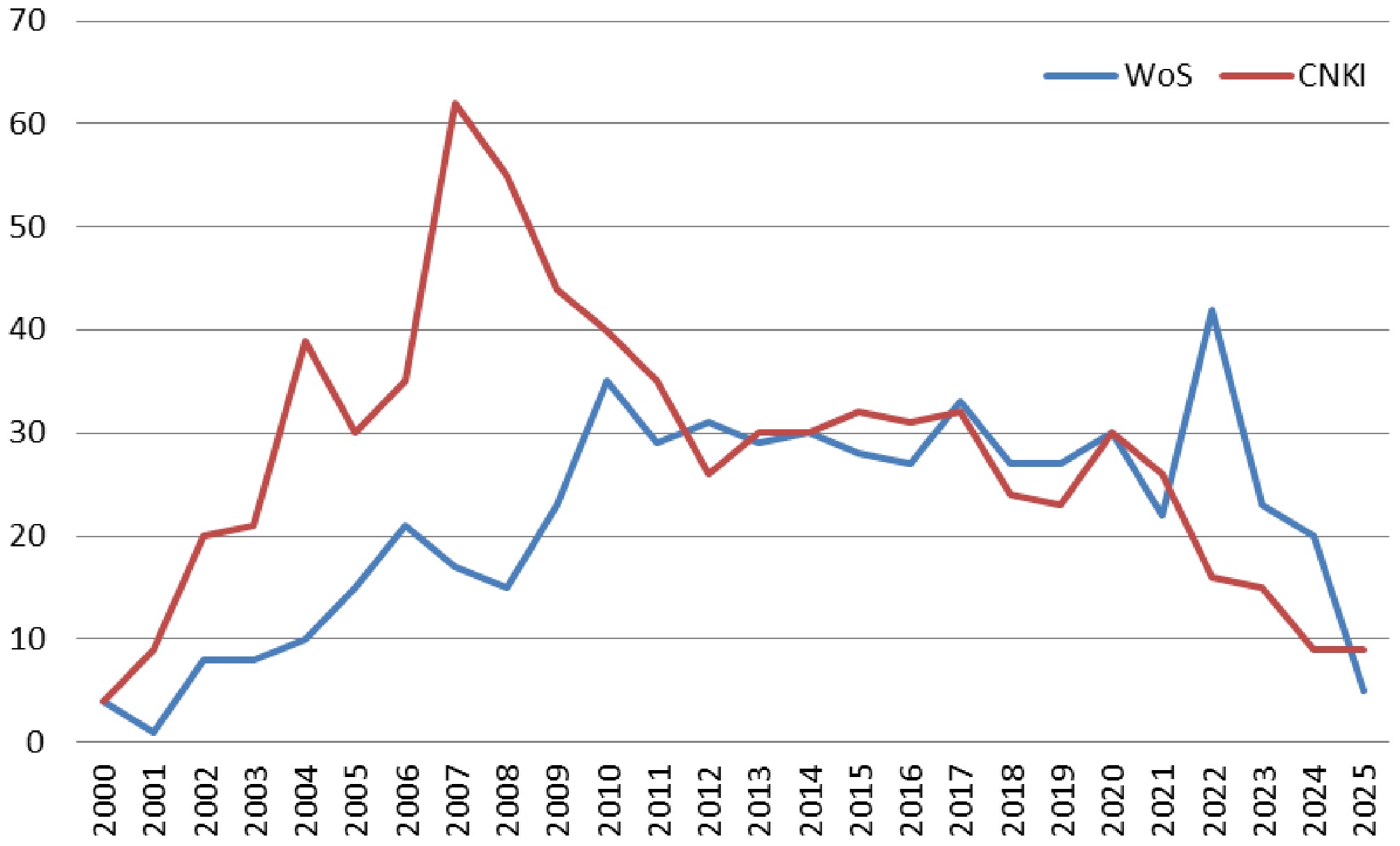

Annual publication volume serves as an indicator of research trends and scholarly interest in the field. CNKI literature can be divided into two phases (Fig. 1): the first phase (2000–2010) experienced a rapid surge, peaking in 2007, signaling the swift maturation of domestic research on orchids; the second phase (2011–2025) saw a stabilization in publication numbers, with annual publications fluctuating between 10 and 40 articles, reflecting a sustained but moderated level of interest. In contrast, WoS publications exhibited a consistent upward trend from 2000 to 2025, with research expanding from single-species studies to encompass a broader range of orchid taxa, highlighting the increasing global attention to this field[21].

Analysis of contributing countries

-

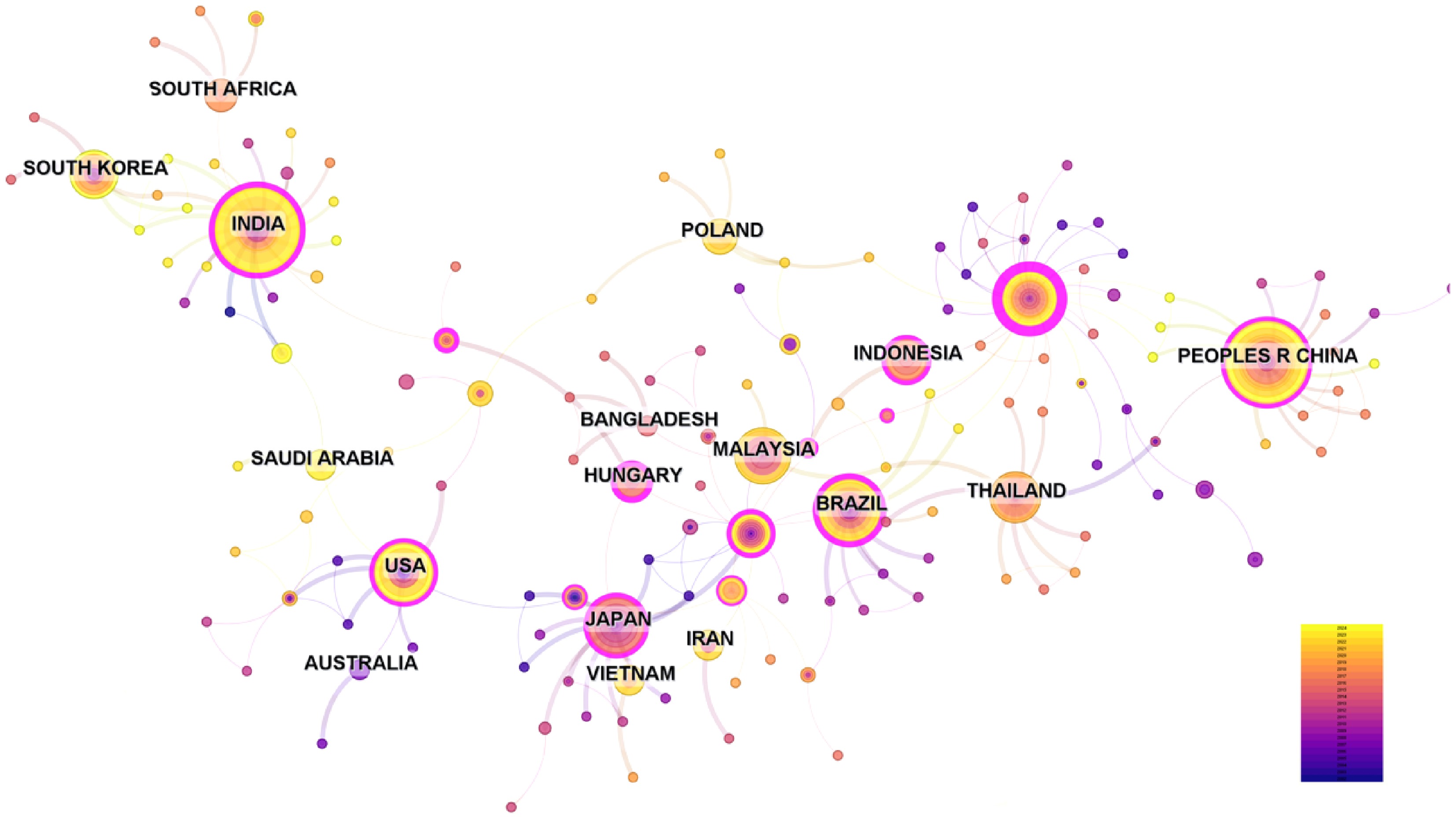

CiteSpace was used to analyze the national distribution of research contributions on orchid tissue culture in the WoS literature (Fig. 2). The analysis of 560 articles revealed contributions from multiple countries, including China, India, the United States, Japan, Brazil, and others. Notably, China contributes the highest number of publications, establishing a global research landscape centered on Chinese leader in orchid tissue culture research[22]. China's output significantly surpassed that of other nations, reflecting its strategic investments and resource advantages in plant biotechnology[23,24]. India ranked second, capitalizing on its rich orchid germplasm resources (e.g., wild Dendrobium and Phalaenopsis) and cost-effective labor to advance rapid propagation technologies for tropical orchids. While Brazil, Japan, and the United States contributed fewer publications, their research demonstrated distinct strengths: Brazil prioritized in vitro conservation techniques for Amazonian endemic species (e.g., Cattleya); Japan excelled in advanced cell engineering technologies, such as protocorm liquid culture and photoautotrophic tissue culture; and the United States emphasized foundational theoretical breakthroughs, including epigenetic regulation of somatic embryogenesis and symbiotic fungal and symbiotic molecular interaction mechanisms. This difference reflects distinct research evaluation systems, resource allocation mechanisms, and research cultures. China, driven by policy and market forces, tends to prioritize immediate application and industrial benefits of technology, while Western countries place greater emphasis on long-term knowledge accumulation and innovation in basic science.

Visualization of keyword co-occurrence networks

-

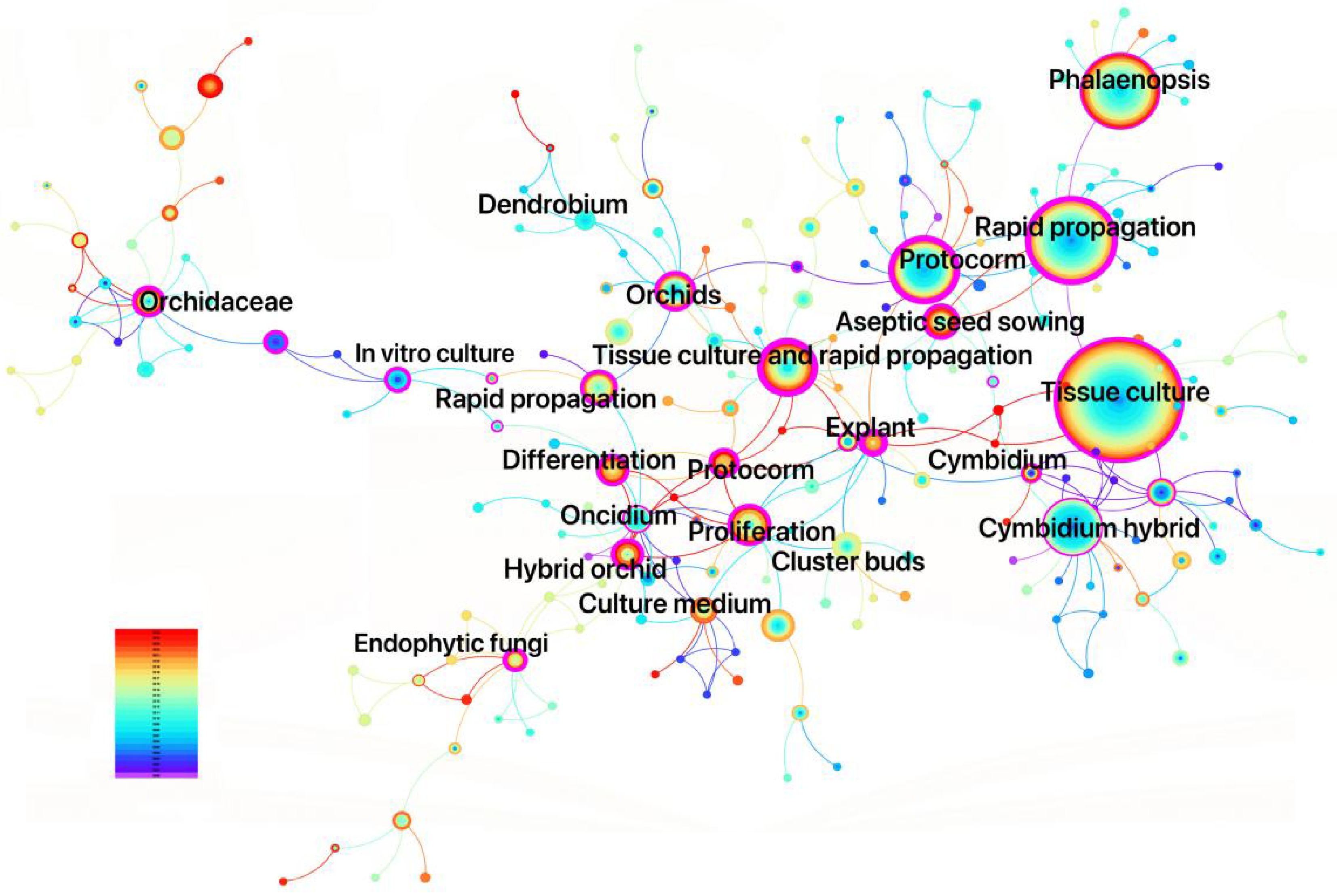

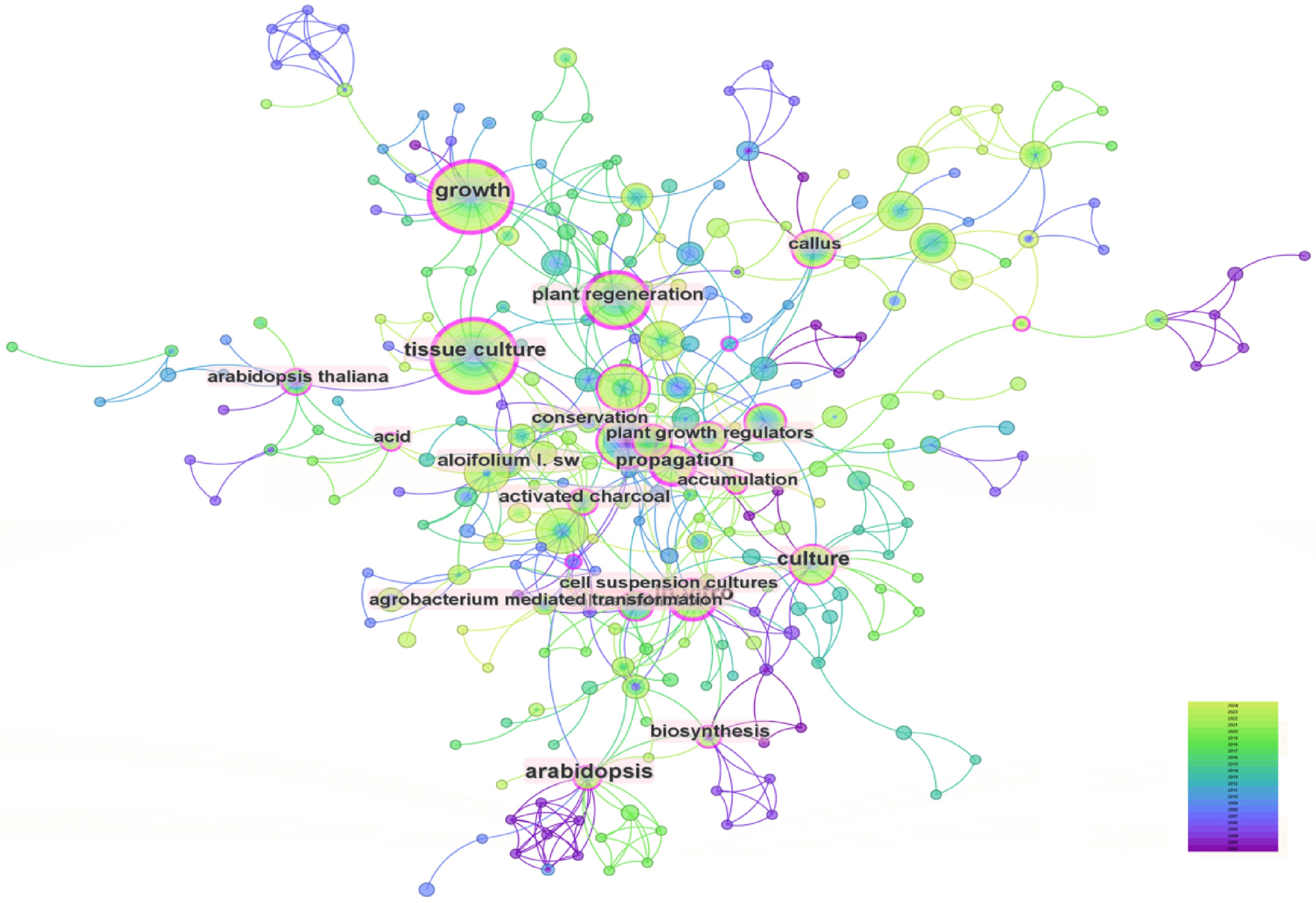

Keywords provide concise representations of research themes, and analyzing high-frequency keywords reveals hotspots, trends, and topic interrelations[25]. The co-occurrence network generated from CNKI literature (227 nodes, 288 links) exhibits low density (0.0112), indicating thematic fragmentation despite identifiable core clusters. High modularity (Q = 0.8043) and silhouette scores (S = 0.9445) confirm robust cluster separation and internal coherence. The keyword co-occurrence network for Orchidaceae tissue culture and rapid propagation research from 2000 to 2025 (Fig. 3) visualizes node size by keyword frequency and ring color by temporal distribution, where thicker rings represent higher frequency in specific time slices. High-frequency keywords include 'tissue culture', 'rapid propagation', 'Phalaenopsis', and 'Cymbidium hybridum' demonstrate strong thematic dominance and temporal continuity, reflecting a sustained domestic research emphasis on propagation systems for these economically significant species. This narrow focus, while commercially rational, has led to significant neglect of non-commercial and endangered orchid species, exacerbating conservation challenges and further underscores systemic imbalances.

For the WoS literature, keyword co-occurrence analysis revealed a network of 298 nodes and 571 links, with a low density (0.0129) reflecting a fragmented, multi-centered research landscape. Despite structural dispersion, high modularity and silhouette values confirm distinct thematic clustering (Fig. 4)[26]. 'Tissue culture' emerged as the central hub node, connecting subfields such as 'plant regeneration', 'growth', and 'somatic embryogenesis', highlighting its foundational role in the field. From this core, three major thematic extensions are evident. Technical optimization: keywords like 'callus induction' and 'protoplast isolation' highlight in-depth exploration of critical techniques such as cell dedifferentiation and protoplast isolation. Applied research: nodes such as 'secondary metabolites' and 'Agrobacterium-mediated transformation' reveal trends in leveraging tissue culture for medicinal compound synthesis and gene editing applications[27]. The pronounced focus on these areas highlights a clear convergence with biomedical and industrial applications, reflecting a research paradigm that is predominantly demand-driven. Theoretical intersection: keywords like 'cell suspension cultures' and 'biosynthesis' reflect ongoing efforts to elucidate molecular regulatory networks underlying plant regeneration. However, the relative conceptual isolation of these theoretical topics signifies a persistent disconnection between applied innovation and foundational mechanistic research. This divergence suggests that current scholarship may favour short-term applicative outcomes over deeper theoretical inquiry, a tendency that could constrain the emergence of transformative advances in the field.

Visualization of keyword clustering networks

-

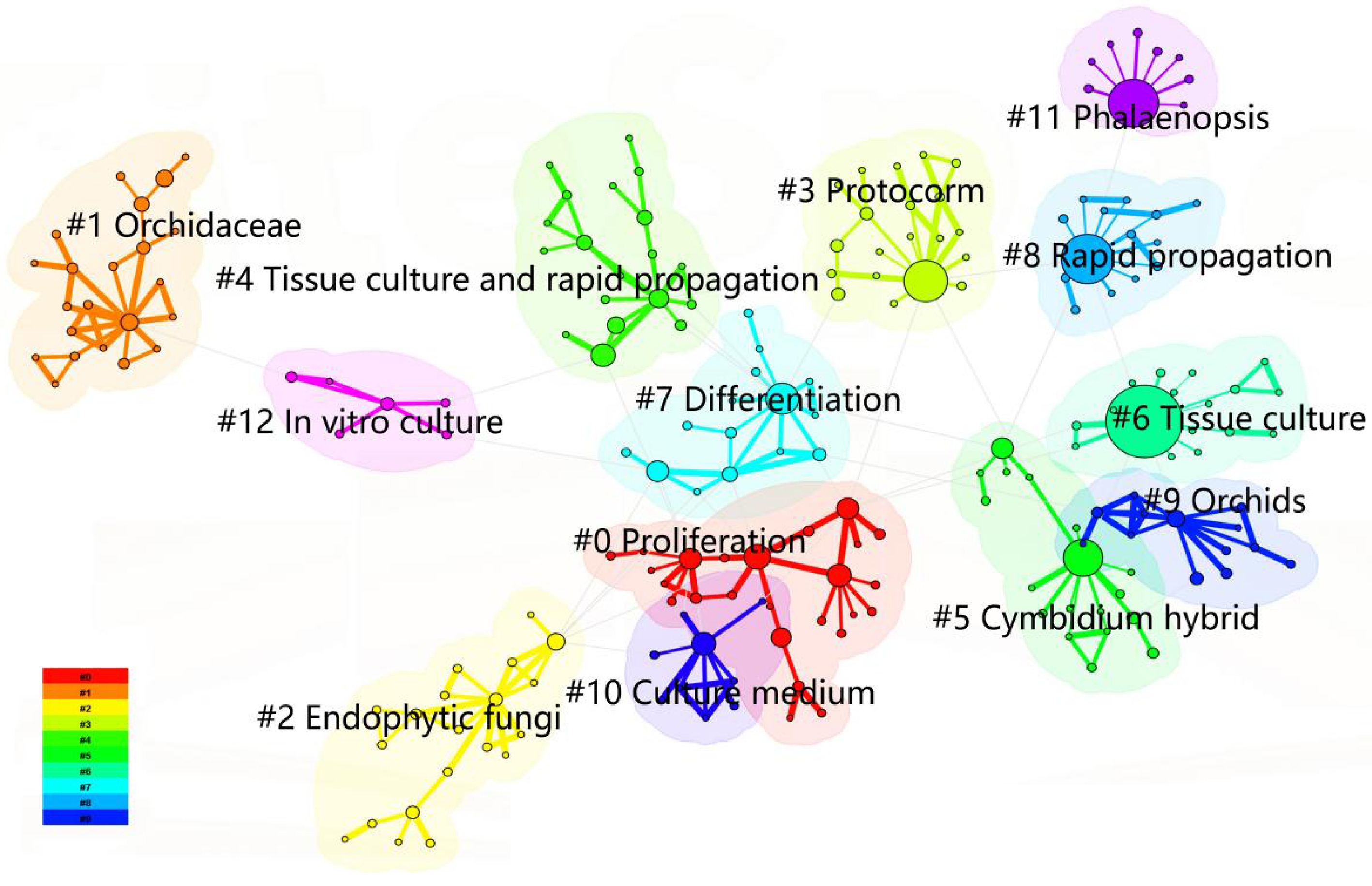

Keyword clustering provides a comprehensive synthesis of research themes by leveraging co-occurrence analysis, visually illustrating major research domains and the relationships between keywords. In CiteSpace, the analysis of orchid tissue culture research in CNKI yielded 13 clusters, with high modularity (Q = 0.8043) and silhouette (S = 0.9445) scores, indicating robust clustering validity and thematic coherence (Figs 5 and 6). Cluster labels, representing the thematic focus of each group, were automatically extracted from high-frequency keywords or phrases within each cluster and are sorted by size, with smaller numerical labels corresponding to larger clusters. The clusters include: #0 Proliferation (largest cluster), #6 Tissue culture, and #8 Rapid propagation, forming foundational technical clusters focused on optimizing common techniques such as culture medium formulations and explant treatments. #5 Cymbidium hybridum and #11 Phalaenopsis, representing species-specific research clusters that reflect distinct cultivation requirements for different orchids[28]. Other clusters, such as #2 Endophytic fungi, #3 Protocorm, #7 Differentiation, and #12 In vitro culture, highlight specialized subfields, including protocorm development, fungal symbiosis, and advanced biotechnological methods[29]. This clustering framework clearly delineates core themes and niche directions in orchids tissue culture research (Fig. 5).

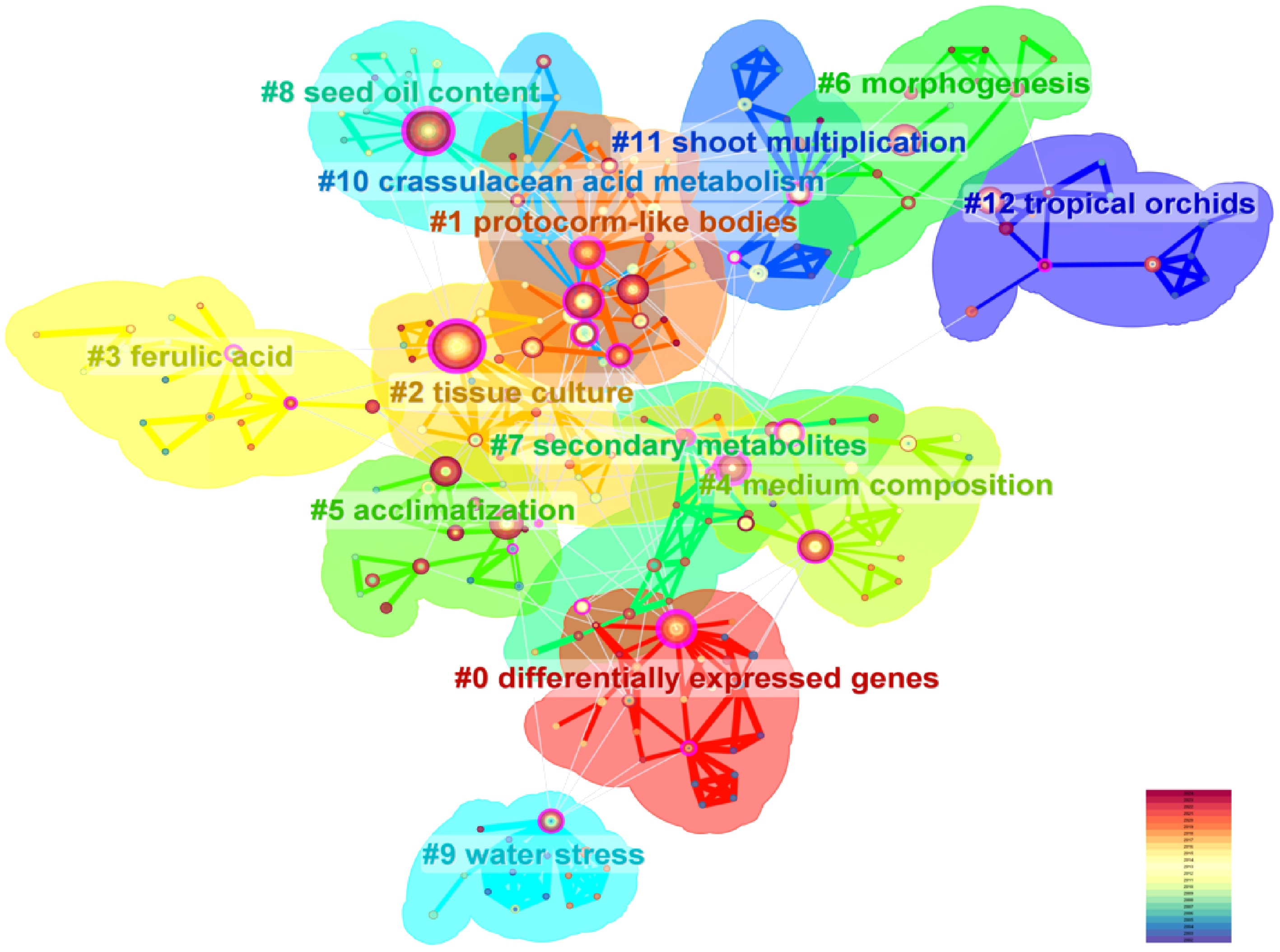

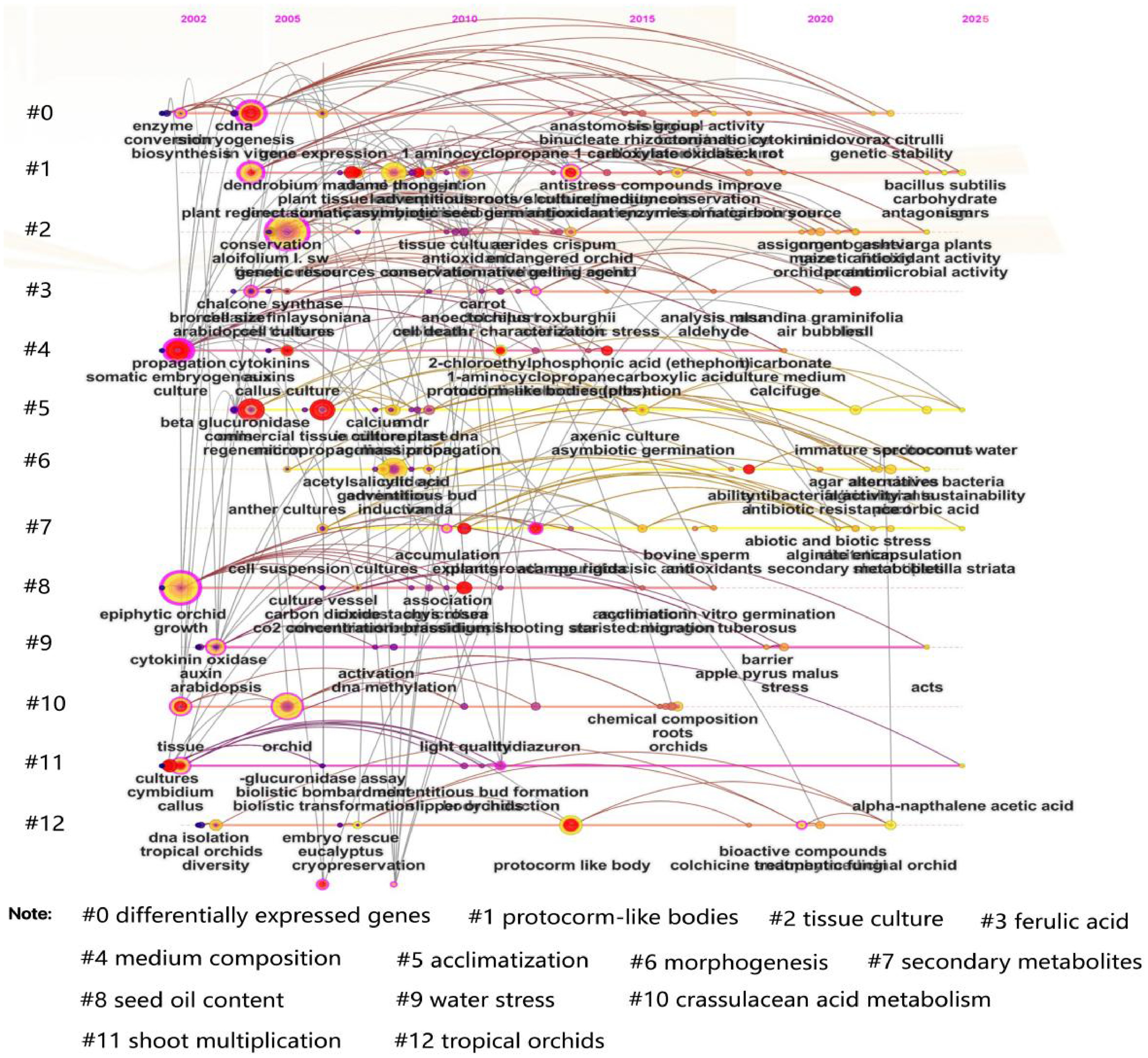

For the WoS literature, the clustering analysis yielded a Q value of 0.7816 and an S value of 0.9228, indicating highly significant clustering structures and strong thematic coherence. A total of 13 keyword clusters were identified, enabling the systematic categorization of research themes in orchid tissue culture and rapid propagation systems into three multi-tiered directions, which span from foundational techniques to cutting-edge applications (Fig. 6). Tissue Culture Technology Optimization and Standardization (#2, #4, #5, #11): Centered on #2 tissue culture and #4 medium composition, this theme focuses on optimizing culture medium formulations, environmental controls, and acclimatization protocols to establish standardized frameworks for industrial-scale orchid propagation[30]. Organogenesis and Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms (#0, #1, #6): The axis formed by #0 differentially expressed genes, #1 protocorm-like bodies, and #6 morphogenesis delves into molecular pathways regulating organ regeneration[31]. Transcriptomic approaches are employed to unravel signaling networks involving auxin and cytokinin during protocorm induction and bud/root differentiation[32]. To truly advance, the field must pivot toward use-inspired fundamental research: leveraging molecular insights to address challenges such as genetic erosion, somatic variation, and poor acclimatization success, thereby aligning laboratory innovation with sustainability and conservation outcomes. Secondary Metabolism and Functional Exploration (#3, #7, #8): Centered on #7 secondary metabolites and #3 ferulic acid, this theme investigates the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds in tissue culture systems, aiming to enhance functional applications[33] such as medicinal compound production and seed oil improvement. This clustering framework highlights the evolution of research from technical refinement to molecular mechanisms and applied biotechnology, reflecting the field's interdisciplinary depth and innovation-driven trajectory[34].

Visualization of keyword time-zone maps

-

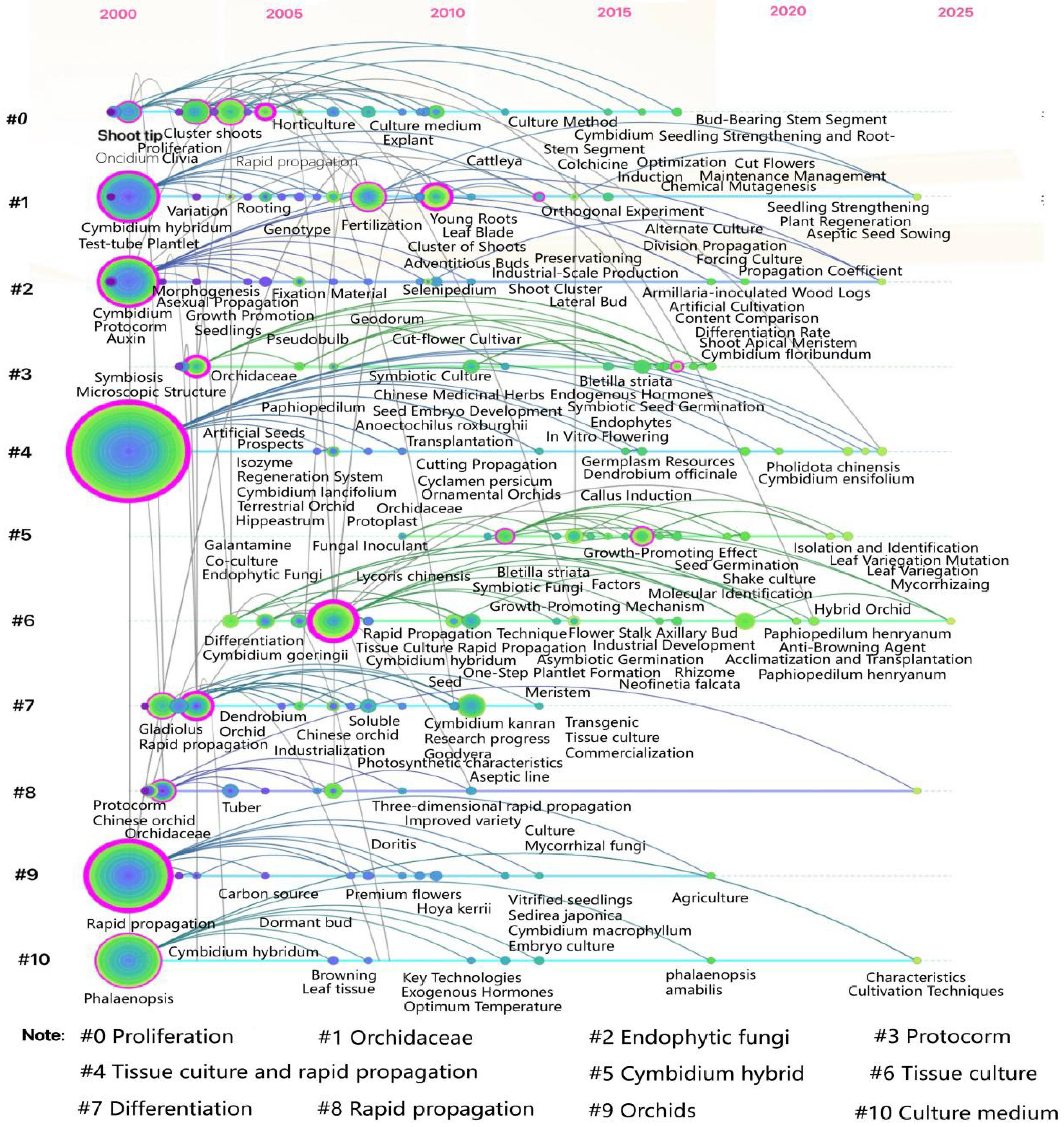

The time-zone map organizes nodes within the same cluster chronologically along a horizontal timeline, illustrating the historical progression of research themes. The CNKI literature time-zone map (Fig. 7) visualizes the evolution of core keywords in orchid tissue culture research from 2000 to 2025, with clusters arranged vertically by theme, and keywords progressing chronologically from left to right. The map highlights ten major clusters representing distinct research themes. Based on their temporal distribution, the development of orchid tissue culture research can be divided into three phases: Technical Foundation Period (2000–2010): Core clusters such as #4 Tissue Culture, #6 Rapid Propagation, and #11 In Vitro Culture dominated this phase. Keywords like 'MS medium', 'sterilization methods', and 'multiple shoot induction' indicate a focus on standardizing foundational techniques, including explant disinfection protocols and hormone ratio optimization[35]. Application Expansion Period (2011–2018): Key clusters like #1 Cymbidium hybridum, #10 Phalaenopsis, and #7 Rapid Propagation emerged. Keywords such as 'orthogonal experiments', 'industrial-scale seedling production', and 'rooting acclimatization' reflect efforts to refine rapid propagation technologies for economically significant species (e.g., C. hybridum, Phalaenopsis), and advance industrial applications[36]. Technical Deepening Period (2019–2025): Emerging clusters like #5 Endophytic Fungi, #8 Protoplast, and #12 Protocorm-like Bodies gained prominence[37]. Keywords such as 'mycorrhizal symbiosis', 'liquid suspension culture', and 'CRISPR' signal a shift toward molecular mechanisms and technological innovation[38], transforming tissue culture practices from empirical operations to mechanism-driven methodologies[39]. This temporal analysis underscores the field's progression from foundational standardization to industrial scalability and molecular-level innovation, driven by evolving research priorities and technological advancements[40].

By analyzing the timeline (Fig. 8), the development of orchid tissue culture technology can be divided into three phases: Technical Establishment Period (2000–2010): Observations of core clusters #2 tissue culture and #4 medium composition, alongside keywords like 'sterilization protocol', 'hormone ratio optimization', and 'rooting induction', reveal that foundational techniques (e.g., culture medium formulations, explant selection) were standardized during this phase[41]. Research focused on establishing sterile cultivation systems for orchids, characterized by early initiation, prolonged duration, and high keyword frequency[42]. Molecular Mechanism Exploration Period (2011–2018): Analysis of emerging clusters #0 differentially expressed genes and #1 protocorm-like bodies, combined with keywords such as 'somatic embryogenesis', 'auxin signaling', and 'WUSCHEL gene', highlights a shift toward molecular regulatory networks. This phase marked a transition from phenotypic observation to genetic regulation, driving advancements in the efficient induction of protocorm-like bodies (PLBs)[43]. Technological Integration Period (2019–2025): Core clusters #7 secondary metabolites and #12 tropical orchids, along with keywords like 'CRISPR', 'metabolic flux analysis', and 'artificial seed coating', demonstrate the integration of gene editing and metabolic engineering[44]. Research during this period prioritized industrial-scale propagation of tropical orchids and the synthesis of bioactive compounds, reflecting interdisciplinary innovation. This timeline underscores the evolution of orchid tissue culture research from foundational standardization to molecular exploration and cutting-edge technological convergence, driven by global scientific collaboration and methodological diversification.

Visualization of keyword burst maps

-

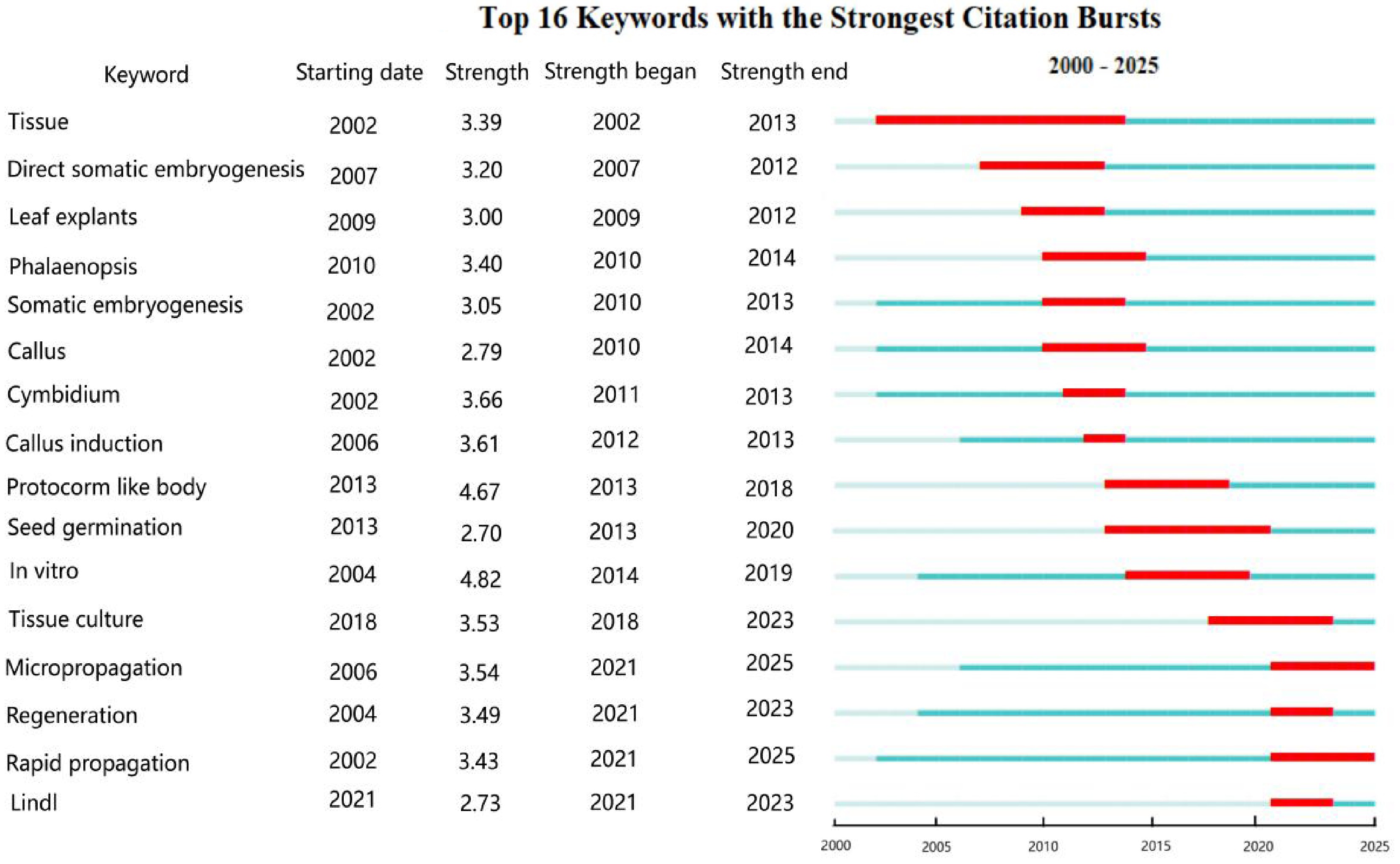

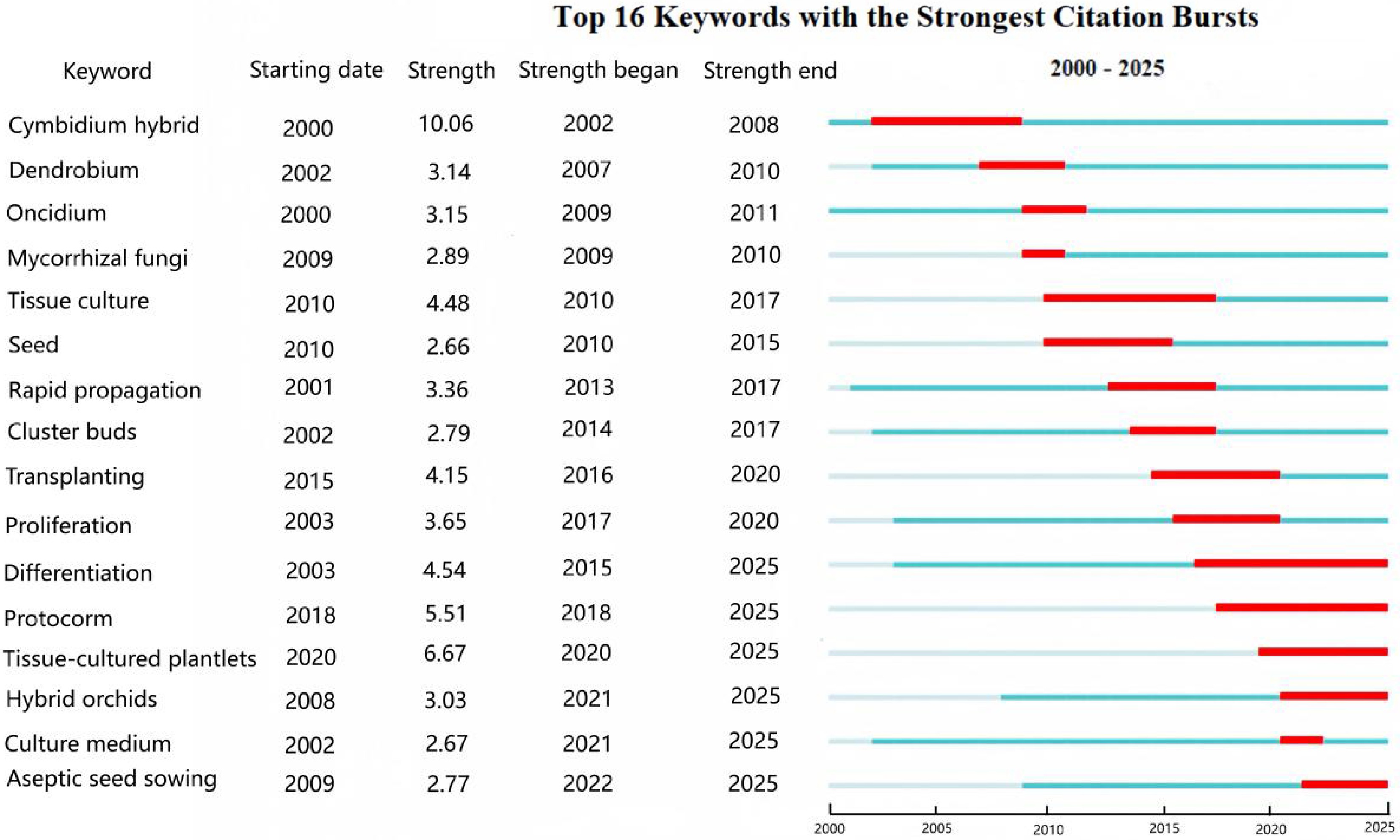

Using CiteSpace's burst detection function, keyword burst maps were generated to identify terms with significant citation frequency changes over specific periods, reflecting emerging or declining research hotspots. In the CiteSpace control panel, burst parameters were adjusted: γ = 0.8 (sensitivity threshold, with lower values detecting more bursts) and Minimum Duration = 2 (shorter durations display more keywords). For CNKI journal literature (Fig. 9), the evolution of research hotspots in orchid tissue culture exhibits characteristics of 'species-driven, middle stage, and technology-deepening': Species-Driven (2000–2010): Research hotspots focused on specific orchid species and fundamental techniques. Ornamental orchids (e.g., C. hybridum) emerged as a hotspot in 2004, driven by commercial demand. Medicinal orchids (e.g., D. officinale) surged in 2007, fueled by interest in bioactive compounds like Dendrobium polysaccharides[45]. Middle Stage (2010–2016): Research emphasis shifted toward optimization and scaling of propagation techniques. Keywords like tissue culture, seed, rapid propagation, cluster buds, transplanting, and proliferation dominated. This indicates researchers' efforts to enhance propagation efficiency and survival rates[46]. Technology-Deepening (2017–2025): Research deepened into tissue-level mechanisms and technical refinement. Differentiation and Protecorm emerged as high-strength hotspots, focusing on organ formation and early developmental mechanisms[47]. Tissue-cultured plantlets hold the highest burst strength (6.67) and continue through 2025, representing the absolute current research focus. This involves studies on the physiology, acclimatization, and scaled production of tissue-cultured seedlings. Aseptic seed sowing, as a fundamental yet critical technique, shows sustained relevance through its ongoing burst (2022–2025), highlighting its enduring application and research value[48].

Figure 9.

Keyword burst detection map of CNKI journals. A higher strength value correspond to greater magnitude of citation growth during the burst period (> 3.0 indicates strong bursts).

For the WoS literature, analysis of Fig. 10 reveals the evolution of research hotspots in orchid tissue culture technology. Foundational Stage (2002–2010): Early research focused on establishing fundamental systems, centering on callus induction and somatic embryogenesis to explore the differentiation potential of explants[49]. Key Technological Breakthrough and Application (2011–2017): Protocorm-like bodies (PLBs) is the most pivotal and active technology in orchid tissue culture (peak strength: 4.67)[50]. As the core pathway for orchid rapid propagation, PLB research dominated in 2013–2018 with exceptional intensity, establishing the cornerstone of rapid propagation techniques[51]. Seed germination and in vitro serve as descriptors of foundational techniques. These terms relate to a symbiotic germination and propagation[52], directly signaling the technology's transition toward scalability, efficiency enhancement, and practical deployment[53] (e.g., commercial seedling production, germplasm conservation). Recent and Current Hotspots (2018–2025): Tissue culture serves as a generalized, mature descriptor (strength: 3.53, 2018–2023), reflecting the technology's widespread adoption and deepening application[54], with techniques progressively extending to multiple species[55]. The triad of keywords—Micropropagation, Rapid propagation, and Regeneration—collectively emphasize commercialization and refinement of core technical processes. This phase prioritizes high-efficiency, low-cost production, marking the complete trajectory of orchid tissue culture from laboratory technique to industrial application, now extending to the entire Orchidaceae[56].

-

Historically, China's research on orchid tissue culture and rapid propagation has focused heavily on economically valuable species such as D. officinale, Phalaenopsis, and C. hybridum. These species, driven by high market demand and mature technologies (e.g., annual production of Dendrobium tissue-cultured seedlings exceeds one billion), dominate both research and industrial priorities[57]. However, this narrow focus exacerbates biodiversity crises. Over 62.3% of China's approximately 1,715 orchids are endangered, yet less than 8.2% receive research attention[58]. For example, many Cypripedium species lack tissue culture protocols, hindering wild population recovery[59]. Future research must shift toward endangered species (e.g., Paphiopedilum, Cypripedium) to balance commercialization with biodiversity conservation[60].

Impact of endophytic fungi on orchid tissue culture

-

Mycorrhizal symbiosis[61], a critical survival strategy for orchids in nature, involves endophytic fungi that play essential roles in seed germination, growth, and environmental adaptation[62]. Studying these fungi[63] enhances artificial propagation, commercial seedling production, and species reintroduction, supporting both conservation and sustainable utilization of orchids[64,65]. Future research in orchid tissue culture should delve into the mechanisms of mycorrhizal symbiosis and apply its beneficial components to artificial propagation and wild reintroduction.

Optimization of culture medium formulations for rapid propagation

-

To optimize the rapid propagation medium for orchids, the formulation should be meticulously designed according to the physiological requirements at distinct developmental stages[66]. During seed germination, a low-salt medium (e.g., 1/2 MS) reduces osmotic pressure to enhance nutrient absorption by immature embryos. Concurrently, 1–2 g/L activated charcoal should be added to adsorb phenolic compounds that inhibit germination, supplemented with 20–30 g/L sucrose or 10%–15% coconut water as carbon sources to mimic the carbohydrate supply from natural symbiotic fungi[67]. At the protocorm proliferation stage[68], a high–salt medium (e.g., full-strength MS) is required. This medium should incorporate cytokinins (e.g., 6-BA 0.5–2 mg/L), and low–concentration auxins (NAA 0.1–0.5 mg/L) to synergistically induce efficient protocorm multiplication[69]. The cytokinin-to-auxin ratio must be optimized through orthogonal design tailored to specific orchid species[70]. During bud differentiation and rooting phases, hormonal balance[71] should be adjusted by gradually reducing cytokinin levels (6–BA decreased to 0.1–0.5 mg/L) while increasing auxin proportions (e.g., NAA 0.5–1 mg/L or IBA 0.5–1 mg/L)[72]. Additionally, natural organic supplements significantly improve shoot vigor and rooting efficiency: 10%–15% coconut water provides cytokinin-like compounds, while 50–100 g/L banana homogenate supplies B vitamins and potassium[73]. The inclusion of 1–2 g/L activated charcoal effectively suppresses browning[74]. Further refinement of hormone combinations and additives based on orchid species and growth stages will substantially enhance the efficiency and adaptability of in vitro propagation systems[75].

Solutions to contamination, browning, and vitrification

-

In orchid tissue culture, contamination, browning, and vitrification are major bottlenecks hindering efficient propagation[76], requiring systematic prevention and targeted interventions. Contamination control[77] relies on rigorous sterilization and explant pretreatment: explants should be rinsed under running water, followed by sequential disinfection with 75% ethanol (30 s) and 0.1% HgCl2 or 2% sodium hypochlorite (8–15 min), then thoroughly washed 3–5 times with sterile water[78]. Aseptic protocols must include UV-sterilized operating environments, pre–running laminar flow hoods for 30 min, and operators wearing proper protective gear while minimizing air turbulence[79]. Browning suppression[80] focuses on inhibiting phenolic oxidation: add 1–2 g/L activated charcoal to the medium to adsorb toxic compounds[81]. Initiate cultures under dark conditions for seven to ten days to reduce light-induced oxidative stress[82]. For highly susceptible varieties, shorten subculture intervals to 20–25 d and employ low-salt media (e.g., 1/2 MS) to alleviate ionic stress[83]. Vitrification[84] mitigation addresses cytokinin excess, high humidity, or osmotic imbalance: Reduce cytokinin concentrations in the medium and increase agar concentration to lower water activity. Incorporate osmotic regulators (e.g., 3% sucrose). Optimize environmental parameters: elevate light intensity to 3,000–5,000 lux, maintain temperatures at 22–25 °C, and reduce humidity to 60%–70% to promote normal tissue lignification[85]. Tailoring these strategies to species–specific responses ensures robust and sustainable in vitro propagation systems[86,87].

Genetic stability and precision improvement in orchids

-

Genetic stability[88] and precision improvement of orchid Genes[89]: key research directions for enhancing propagation efficiency[90], stress resistance[91], and ornamental value[92]. In terms of genetic stability[93], orchids are prone to some clonal variation during prolonged tissue culture, manifested as chromosomal abnormalities, alterations in DNA methylation patterns, or transposon activation, leading to phenotypic divergence (e.g., flower color changes, stunted growth)[94]. To maintain genetic uniformity[95], optimized culture systems are critical: limit subculture cycles (typically ≤ 5 generations). Use low cytokinin concentrations (e.g., 6-BA ≤ 1 mg/L). Select apical meristems or protocorm tips as explants to minimize chimera formation[96]. Regularly monitor genetic variations using molecular markers (e.g., SSR, ISSR). For precision genetic improvement, modern biotechnologies such as targeted gene editing (CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs) or transgenic approaches[97] enable directional regulation of desired traits[98]. Future advancements will integrate multi–omics data (genome[99], spatial-temporal omics, transcriptome[100], metabolome[101]) with machine learning models to achieve precise genotype-to-phenotype predictions[102]. Coupled with automated tissue culture systems and phenomics platforms, this integration will accelerate the targeted breeding of superior traits, offering innovative strategies for orchid conservation and industrial-scale cultivation[103,104]. Future research in orchid tissue culture should promote the application of new technologies such as gene editing, multi-omics integration, and artificial intelligence in controlling genetic stability and precise trait improvement, thereby achieving a transition from empirical practices to mechanism-driven approaches.

-

Using CiteSpace for bibliometric analysis, this research represents the first integrated analysis of both English and Chinese mainstream databases on orchid tissue culture technology to systematically elucidate the development trajectory and global research landscape of orchid tissue culture technology from 2000 to 2025. The findings demonstrate that, despite considerable advances in propagation efficiency, breeding innovation, and industrial application, several challenges persist—including technical bottlenecks, limited market acceptance, and entrenched traditional perceptions. Current research remains disproportionately focused on a limited number of economically significant species, while effective tissue culture protocols are still lacking for the majority of endangered orchids, underscoring a substantial disparity between conservation imperatives and utilization efforts. Beyond tracing the evolutionary pathway from technical optimization to molecular mechanisms, this study also identifies critical research gaps and future priorities within a global comparative context. By integrating bibliometric insights with domain-specific expertise, this work establishes a forward-looking theoretical framework and methodological foundation for driving precision innovation, enhancing species conservation, and promoting the sustainable application of orchid tissue culture technology.

This work was supported by the Conservation and Utilization of Germplasm Resources and Genetic Improvement (304-72202202306).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data curation: Lan S, Fan X, Zhao X; formal analysis: Fan X, Zhang W; visualization: Fan X, Chen Y; providing suggestions and editing for the manuscript: Fan X, Zhao X; provided guidance: Liu ZJ, Lan S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fan X, Zhao X, Zhang W, Chen Y, Zhao X, et al. 2025. A CiteSpace-based bibliometric analysis of research hotspots and trends in orchid tissue culture. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e046 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0043

A CiteSpace-based bibliometric analysis of research hotspots and trends in orchid tissue culture

- Received: 11 August 2025

- Revised: 18 September 2025

- Accepted: 30 September 2025

- Published online: 11 December 2025

Abstract: Research on orchid tissue culture and rapid propagation technologies provides key solutions for improving propagation efficiency, expanding seedling production, and cultivating new varieties. However, in the field of orchid tissue culture and rapid propagation research, there is a lack of comprehensive, quantitative analyses, and data-driven studies. The bibliometric software CiteSpace was used to conduct a visual quantitative analysis of 1,287 publications (January 1, 2000, to June 30, 2025) in the Web of Science (WOS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database to address this gap. The results indicate that, since 2020, research has increasingly focused on economically valuable orchids such as Dendrobium officinale, Phalaenopsis spp., and Cymbidium hybridum. Current research hotspots center on the regulatory roles of endophytic fungi in tissue culture and rapid propagation, as well as on the systematic optimization of culture-medium formulations; in parallel, preventive and corrective strategies to address persistent bottlenecks—including contamination, browning, and vitrification—are being continuously refined. In recent years, the field has increasingly shifted toward molecular-level inquiry, emphasizing elucidation of the genetic and regulatory mechanisms underlying key traits, including the formation of floral color and fragrance, floral organ morphogenesis (e.g., MADS-box gene networks), and abiotic stress tolerance (e.g., drought and heat). This study seeks to provide theoretical foundations and methodological references for advancing tissue culture and rapid propagation techniques in orchids.

-

Key words:

- Orchidaceae /

- Tissue culture /

- Rapid propagation /

- CiteSpace.