-

Environmental pollution and plastic waste have emerged as urgent issues of global importance, fuelled by many years of excessive consumption and overproduction[1]. Although petrochemical plastics are prized for their resistance and versatility, their longevity presents severe waste disposal issues, disturbing ecosystems and greenhouse gas emissions in the manufacturing process[2,3]. As a green substitute, polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) have attracted significant interest because they are biodegradable, biocompatible, and possess mechanical properties akin to polypropylene[4]. PHAs are produced by bacteria naturally as intracellular carbon and energy storage materials under carbon-rich but nutrient-limiting conditions, and provide functional and environmental benefits[5,6]. Conventional PHA production has typically relied on pure carbon substrates such as glucose, sucrose, maltose, starch, fatty acids, methanol, and alkanes[7]. However, carbon feedstocks alone account for nearly 50% of total production costs[8], making economical alternatives essential for industrial-scale feasibility. First-generation sugar-based feedstocks such as sugarcane, corn sugar, whey, palm oil, and vegetable oils have been extensively studied but are problematic for food security and food and energy market competition[9]. While potent as substrates, their congruence with world food demands makes large-scale utilization not sustainable. On the other hand, sugar-based agro-industrial residues present a more promising avenue. Waste streams like sugarcane bagasse, molasses of cane and beet, corn steep liquor, and fruit peels carry high concentrations of fermentable sugars that are compatible for microbial conversion into PHAs by organisms like Cupriavidus necator and Bacillus megaterium[10,11]. This use of by-products minimizes reliance on food crops, reduces substrate expense, and supports circular economy principles through valorizing waste. In addition, their structural variability allows them to have extensive applications, from packaging, textiles, and animal feed supplements to biomedical applications such as implants and drug delivery. Generally, renewable waste feedstocks are economically and environmentally friendly, facilitating sustainable PHAs production. Their incorporation not only enhances degradable plastics but also helps in conserving resources and minimizing environmental deterioration[12,13].

This review aims to highlight the application of sugar-rich feedstocks in the sustainable production of PHAs as biobased plastics.

-

Efficiency in PHAs biosynthesis varies with feedstock content, sugar type, and conditions of fermentation. Conveniently metabolizable substrates such as molasses, fruit juices, and corn steep liquor result in high yields in Cupriavidus necator and Bacillus megaterium. Lignocellulosic residues, however, need to be pre-treated, and results are determined by microbial tolerance to degradation by-products[12]. Furthermore, several studies revealed that pre-treatment is considered as an energy-sensitive and costly step as it converts lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars. The recalcitrant nature of biomass, having tough lignin, requires significant energy to break it down[14,15]. Microbial metabolism and biosynthesis of PHAs are highly dependent on sugar composition. Strains capable of utilizing mixed sugars broadly ferment well, while limited strains are poor. Inhibitory substances like organic acids, phenolics, and salts found in molasses or fruit waste can inhibit growth, and detoxification or microbial acclimation is needed. Optimal sugar concentration is crucial—suboptimal levels limit biomass, while excess may lead to osmotic stress or catabolite repression. Fermentation conditions such as pH, aeration, temperature, oxygen transfer, and C/N ratio control polymer accumulation, with nitrogen deficiency and carbon excess favouring PHAs storage. Fed-batch operations are frequently employed to maintain maximum sugar concentration[16,17]. Strain choice also matters. Effective strains degrade several sugars, are resistant to inhibitors, and store high levels of PHAs. Bacillus subtilis, B. cereus, Alcaligenes sp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa break down sucrose, glucose, and fructose, while B. megaterium can accommodate molasses variation. Tolerant strains such as Bacillus sp. BM37, Paracoccus sp., Halomonas, and C. necator perform well on sugar-rich residues[18−21].

Conversion of substrates through three sequential enzyme-catalyzed reactions

-

This pathway entails the conversion of substrates such as sugars or amino acids into acetyl-CoA, which is then followed by three consecutive enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The reversible condensation of acetyl CoA into acetoacetyl-CoA is catalyzed by B-Ketothiolase (PhbA). The intermediate is subsequently reduced by acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhbB) into d-(-)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, which requires NADPH. The polymerization is then catalyzed by P(3-HB) synthase (PhbC)[22]. Later on, the cycle is closed by acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase (AACS), which reconstitutes acetoacetyl-CoA and converts to acetyl-CoA, which then can feed into the citric acid cycle[23].

Conversion of substrates through β-oxidation intermediates produced from fatty acids

-

Bacteria such as Ralstonia eutropha (also known as Cupriavidus necator) have extracellular lipases and possibly extracellular polysaccharides that help in the formation of stable emulsions when cultivated on plant oils, thus making fatty acids more bioavailable[24,25]. During β-oxidation, enoyl-CoA molecules are either directed towards the PHAs precursor (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA through an (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (PhaJ), or 3-ketoacyl-CoA molecules are converted to (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA via a β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG).

Conversion of substrates through other pathways

-

The second route is through the 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP-CoA transferase (PhaG) enzyme conversion of the fatty acid biosynthesis intermediate (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-ACP into (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA[26]. Another well studied route is the utilization of propionic acid to produce (R)-3-hydroxyvaleryl-CoA. After the uptake of propionic acid, acyl-CoA synthetase catalyzes its conversion to propionyl-CoA. Aside from two molecules of acetyl-CoA, PhaA can also condense acetyl-CoA with propionyl-CoA to give ketovaleryl-CoA (Fig. 1). However, this reaction is mainly performed by two other 3-ketothiolase named BktB[27]. Ketovaleryl-CoA is eventually reduced to (R)-3-hydroxyvaleryl-CoA by PhaB.

Pre-treatment process of bagasse and molasses from sugar-based cultivated crops for PHAs production

-

Lignocellulosic biomass, which consists of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, is inherently resistant to microbial breakdown and, therefore, pre-treatment is an essential process for effective sugar production and subsequent PHAs production (Fig. 2). Efficient pre-treatment increases cellulose exposure, allowing as much as 90% of reducing sugars to be liberated for fermentation[28]. This mechanism is central to reducing production costs by maximizing sugar release, consequently enhancing yield, and economic viability of PHAs[29,30]. The increased fermentability of sugar-containing feedstocks is a result of their sucrose, glucose, and fructose, which are easily metabolized by PHAs-producing microorganisms like Cupriavidus necator and Bacillus megaterium with very high productivities[29,31,32]. For agro-industrial residues like sugarcane bagasse, pre-treatment plays a significant role in lignin removal, cellulose decrystallization, and solubilization of hemicellulose, enhancing porosity and enzymatic accessibility[33,34]. In contrast, sugarcane molasses, even if sucrose-rich, contains phenolics, heavy metals, and nitrogenous compounds that repress microbial growth, and PHA biosynthesis. Additionally, the majority of PHAs-producing strains do not have glycosyl hydrolases to metabolize sucrose directly, necessitating hydrolysis into glucose and fructose, and minimizing inhibitory compounds[35,36]. Depending on the application of acidic, alkaline, or enzymatic hydrolysis, additional impurities can occur, which have a detrimental effect on microbial efficiency[32]. Parallel challenges are found in beet molasses and fruit peels, whose pre-treatment guarantees the release of fermentable sugars, a balance of nutrients, and neutralization of inhibitors[37]. Generally, tailoring pre-treatment to the characteristics of each feedstock is required for the development of low-cost agro-industrial residues into consistent, sustainable substrates for industrially scaled PHAs production.

Acid pre-treatment

-

Acid pre-treatment is one of the most common approaches to enhance the hydrolysis efficiency of lignocellulosic biomass (Fig. 2). Dilute acid pre-treatment, in general carried out with 0.05%–5% acid solutions at 160–220 °C, for time periods ranging from seconds to several hours, solubilizes mainly hemicellulose and breaks lignin–polysaccharide bonds, thus increasing cellulose access to hydrolytic enzymes. It is a process of breakage of hemicellulose and amorphous cellulose into fermentable sugars, and optimization of process parameters needs to be carried out with care to achieve a high sugar yield while limiting the formation of inhibitory by-products. Acid hydrolysis is a conventional method of releasing fermentable sugars from the lignocellulosic structure in sugarcane bagasse processing, which is followed by mechanical washing and water leaching, for the removal of fine debris and surface waxes. Further staged dehydration reduces impurities before fermentation[38]. Unless efficiently removed, such impurities inhibit microbial metabolism and polymer biosynthesis, eventually lowering PHAs yield and overall process performance. Therefore, efficient substrate purification is of great importance in valorizing agro-industrial residues. Bagasse possesses the greatest promise, yielding 5.86 mg/mL PHAs[39]. Feedstock properties also determine treatment severity. Sugar-dominant, lignin-deficient feedstocks can tolerate mild conditions, whereas lignin-dominant materials are treated with severe conditions. Oladzad et al.[40] illustrated that DPC structural recalcitrance drives bioprocess yields. Hydrothermal and dilute acid pre-treatment (0.5% v/v H2SO4) at 80–140 °C for 60–90 min enhanced carbohydrate accessibility, and enzymatic hydrolysis was best performed at 120 °C for 90 min. This treatment enhanced total sugars by 55.02% with less inhibitors, and follow-up anaerobic digestion enhanced hydrogen, ethanol, and volatile fatty acids production by 59.75%, reiterating the significance of pre-treatment in bioprocessing efficacy. Concentrated acid pre-treatment, though efficient at milder conditions, is constrained by equipment corrosion and inhibitory lignin precipitates. The most common chemical used is sulfuric acid, whereas hydrochloric, phosphoric, and nitric acids are alternatives. Zhao et al.[34] described that 2% H2SO4 at 121 °C for 2 h obtained 85% solubilization of hemicellulose, and 16% lignin reduction. Dilute acid procedures are still favoured due to ease and economy[41,42], even though they create inhibitors like furfural, HMF, acetic acid, and phenolics, which negatively impact microbial fermentation as well as PHAs productivity[43,44]. Generally, dilute acid pre-treatment is seen to be the most efficient and scalable process of bagasse pre-treatment for PHAs production.

Alkaline pre-treatment

-

Alkaline pre-treatment, typically utilizing sodium hydroxide (NaOH), calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), potassium hydroxide (KOH), or ammonia (NH3) is prevalently applied to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass through selective lignin removal (Fig. 2). Adjustments of process conditions, such as alkali concentration, temperature (generally below 100 °C), and incubation time, can be made depending on feedstock composition and lignin levels. Low-lignin biomass is subjected to milder treatment, whereas high-lignin feedstocks need more concentrated alkali, or increased exposure time for effective delignification[45,46]. The pre-treatment has the added advantage of increasing the accessibility of cellulose while retaining fermentable sugars and generating fewer inhibitors than acid-based methods[47]. Some recent developments include oxidative alkaline systems, e.g., NaOH with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which enhance lignin degradation and efficiency in sugar conversion[48,49]. Yu et al.[50], for instance, indicated that treatment with 1% NaOH at 120 °C for 10 min eliminated 67.5% of the lignin in sugarcane bagasse, and NaOH–H2O2 blends further improved enzymatic digestibility. Whilst these benefits exist, one serious disadvantage of alkaline pre-treatment is that a considerable proportion of hemicellulose is still bound in the residual solids, and so is less available for sugar release than with dilute acid treatments. As a result, additional hemicellulolytic enzymes such as xylanase are usually added during subsequent hydrolysis to maximise overall carbohydrate recovery[51]. Generally, alkaline pre-treatment is still an economical and effective method for bagasse valorization, especially with the addition of enzymatic means for total carbohydrate utilization.

Organosolv pre-treatment

-

Organosolv pre-treatment utilizes organic solvents, with or without water and catalysts, to break down lignocellulosic biomass by splitting α- and β-aryl ether cross-linkages in lignin. Organosolv pre-treatment dissolves and ruptures lignin (Fig. 2), hence enhancing cellulose and hemicellulose susceptibility to enzymatic hydrolysis and, ultimately, sugar release for PHAs production[52]. Though water-soluble lignin residues are inhibitors of enzymes, the process considerably enhances biomass digestibility and enables one to recover lignin of high purity for industrial uses. Solvents can vary from the low-boiling alcohols (methanol, ethanol), to boiling components like ethylene glycol, glycerol, dimethyl sulfoxide, and phenolics[53]. Reactions are commonly at 100–250 °C, with increased temperatures (185–210 °C) producing organic acids that decrease the requirement for external catalysts, although mineral or organic acids might be added to further promote delignification and xylose recovery[54]. Organosolv divides biomass into three streams: purified cellulose, aqueous hemicellulose, and dry lignin[55]. Experiments validate its efficacy for sugarcane bagasse, with 45.3% lignin and 72.5% hemicellulose removal with 50% ethanol at 121 °C[56], and 75.5% lignin removal with 60% ethanol, and 5% NaOH at 180 °C[57]. Effective recovery of solvent is necessary for economic feasibility[58].

Steam explosion

-

Steam explosion is a green pre-treatment (Fig. 2) that utilizes high-pressure saturated steam (160–260 °C), and subsequent depression to break-down lignocellulosic biomass structure and enhance digestibility[59]. Two modes are predominant: batch, in which biomass is subjected to instant depressurization into a discharge vessel; and continuous, in which it is sent into a pressurized reactor through periodic opening of valves resulting in tiny explosions[60]. Whereas the operations vary, the two methods are based on explosive decompression with similar results. This process works best for sugarcane bagasse, allowing for fractionation and recovery of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose[61]. Silveira et al.[62] recorded 85% solubilization of hemicellulose in a 65 L reactor, whereas Zhang et al.[63] released 9.8 g/L xylose under hot water pre-treatment with acetyl support at 160 °C for 70 min. Moreover, steam explosion causes autohydrolysis, changing bagasse surface morphology and also enhancing enzymatic saccharification efficiency[64].

Biological pre-treatment

-

Biological pre-treatment is an eco-friendly process (Fig. 2) that employs certain cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic enzymes or microorganisms to break down lignocellulosic biomass[65]. This approach is less energy-intensive, and generates fewer inhibitory by-products than chemical and physical pre-treatment methods. However, its application in industries is constrained by the extended duration of biodegradation. Different microorganisms, such as fungi and bacteria, recovered from sources like soil and lignocellulosic residues, can be employed for the biological pre-treatment of feedstocks rich in sugars (Tables 1 & 2).

Hydrolysis pre-treatment

-

Hydrolysis pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass hydrolyzes hemicellulose and cellulose into fermentable sugar, and thereby enhances carbon supply for PHAs production. The enzymatic hydrolysis technique is used over acid treatment since it is eco-friendly, less inhibitor is produced, avoids corrosion issues, and provides near complete cellulose conversion with higher PHAs yield[66]. Enzymatic pre-treatment processes are tailored for sugar-rich feedstocks by adapting enzyme cocktails to the targeted carbohydrate content and accessibility of the substrate. In the case of sugarcane bagasse, molasses, or comparable feedstocks, the enzyme blend is designed to maximize fermentable sugar release while reducing inhibitory by-products[67]. Cellulase, composed of endoglucanases, exocellobiohydrolyases, and β-glucosidase, hydrolyzes cellulose to glucose[68]. Hemicellulose, being branched in nature, is hydrolyzed by enzymes like xylanases, arabinofuranosidase, and glucuronidase, releasing xylose, galactose, and arabinose[69]. Hydrolytic cellulases are formed by both bacteria (Streptomyces, Bacillus, Clostridium), and fungi (Trichoderma, Penicillium, Aspergillus)[70,71]. But due to slow microbial activity, commercial enzymes are normally employed for efficient hydrolysis.

Application of sugarcane, bagasse, and molasses for PHAs production

-

Sugarcane, a tropical perennial grass, ranks among the most cultivated plants in the world for sugar production, and constitutes a very good feedstock for microbial fermentation as it contains a high amount of sucrose combined with fermentable sugars like glucose and fructose. Due to these properties, it presents a promising raw material to produce PHAs (Table 1). Its benefits are in the form of high hectare yields, low culture costs, and rich by-products like molasses and bagasse, which improve the feasibility for large-scale synthesis of PHAs. Sugarcane molasses, being a sugar-refining by-product consisting of almost 50% sugars along with growth-promoting nutrients, is universally known to be a low-cost substrate and is also focused on improving sustainability through waste valorization. Chaudhry et al.[72] showed that Pseudomonas species were able to accumulate 20%–36% PHAs from molasses, whereas Bacillus megaterium produced 72.7 g/L cell mass with 42% PHAs content when grown on molasses[73]. Cupriavidus necator (DSM 545) and Burkholderia sacchari strains have also been effectively used utilizing molasses or sugarcane juice[74,75]. As C. necator cannot directly ferment sucrose, molasses hydrolysis by chemical, enzymatic, or mixed treatments is necessary. The efficiency of fermentation is subject to optimized conditions such as temperature, pH, and nutrient levels that have a substantial impact on yields. Albuquerque et al.[76], for instance, documented that reactor pH changes volatile fatty acid composition, with impacts on PHAs copolymer ratios. Strain variation also has its importance, and Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli yield 54% and 47% PHAs, respectively, from molasses fermentation under pH 7 and 35 °C[77]. Bacillus cereus, Alcaligenes sp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are also commonly employed due to their high sucrose, glucose, and fructose fermentation in minimal medium conditions[18].

Bioprocess advancements have enabled the use of sugar industry by-products, particularly molasses, for PHAs production. Low-grade molasses, a sucrose-rich syrup unsuitable for food, has shown promise as a cost-effective substrate[79]. Although production levels are not always competitive, several studies highlight its potential. Chaudhry et al.[72] documented Pseudomonas species utilizing molasses to produce PHAs with dry cell weight in the range of 7.02–12.53 g/L and with 20.63%–35.63% polymer content. Likewise, Kulpreecha et al.[73] showed Bacillus megaterium BA-019 grown on sugarcane molasses yielded 72.7 g/L cell weight with 42% PHB (the most common and well-characterized PHA), showing its potential for industrial-scale usage.

Albuquerque et al.[76] introduced a three-step procedure through molasses fermentation to organic acids, PHAs accumulation, and batch fermentation and obtained 30% PHAs of cell dry weight (CDW). Enterobacter cloacae also used molasses efficiently by reducing production costs[78]. Recombinant approaches broadened molasses' versatility, such as Ralstonia eutropha recombinantly engineered with Mannheimia succiniciproducens sucrose genes, which promoted sucrose growth but with low yield[80], while Jo et al.[81] improved poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)] and poly(3HB-co-lactate) production by recombinant R. eutropha expressing β-fructofuranosidase. Fermentations in the laboratory validated high yields, with Bacillus cereus SPV yielding 61% PHAs in flasks, and 51% in a 2 L fermenter[82], and Pseudomonas fluorescens A2a5 yielding 68.7% PHAs with 32 g/L biomass in a 5 L reactor[83]. Analogously, genetically engineered Klebsiella aerogenes containing R. eutropha genes had yields similar to wild strains, albeit with stability constraints[84].

Vinasse, another acidic pH and high-organic load by-product of the sugar industry, also favours PHAs production if pre-treated to remove polyphenolic inhibitors. Haloarchaea like Haloarcula marismortui and H. mediterranei effectively converted vinasse into 4.5–19.7 g/L PHAs[85,86], with mixing vinasse and molasses favouring PHB accumulation up to 56%[32]. Strain and substrate concentration have a significant effect on yields, varying from 0.60 g/L PHB in Bacillus megaterium using 4% molasses[87] to 59% PHB in Azotobacter vinelandii UWD using 5% molasses[88]. Halophiles eschew sterile conditions and produce PHBV without precursors, and discharge of saline effluent is an issue, partially resolved by desalination measures[89].

Sugarcane bagasse, a lignocellulosic sugar-processing by-product, is a rich feedstock for PHAs but must be pre-treated to release fermentable sugars and minimize inhibitors like furfural and acetic acid. Acid hydrolysis of bagasse at 120 °C allowed Burkholderia sp. to produce 3.26 g/L PHB[90], whereas Burkholderia cepacia grown on bagasse hydrolysate produced 53% CDW with 2.3 g/L 3HB[91]. In the same vein, Cupriavidus necator survived acid/heat-pre-treated bagasse hydrolysates upon inoculation at high density, yielding PHB at 57% CDW[92]. Tyagi et al.[38] proved that residual sugars in bagasse filtrate, optimally at 60% with yeast extract and salts at pH 7.0 ± 0.5, yielded 55% PHAs, proving the worth of non-lignocellulosic bagasse-derived media. Apart from PHB, co-polymer production has also been investigated; Lopes et al.[90] reported PHBV production when levulinic acid was supplemented during Burkholderia fermentations. Yu & Stahl[92] also demonstrated that toxicity in hydrolysates could be alleviated by dilution as well as inoculation with tolerant strains of C. necator. Bengtsson et al.[93] further reported a Tg of −10.3 and −14 °C for the PHAs produced from 53%–63% mol 3HV from molasses and synthetic VFA solutions, respectively. Taken together, these results establish that sugarcane bagasse, besides its traditional applications as fuel for boilers and raw material for papermaking, can be used as a cheap carbon source for sustainable PHAs production.

Table 1. Production of PHAs from sugarcane by-products.

By-product Concentration of

raw materialInitial treatment of raw material Microbe utilized with

inoculum concentrationPHAs yield (%) Ref. Molasses 80 g/L Acidic treatment Cupriavidus necator 11599 75.64 [35] Molasses 2−10 Not mentioned Enterobacter sp. SEL2 47.4−92.1 [36] Cane molasses + ammonium sulphate 20 g/L Not mentioned Bacillus megaterium BA-019 49.9−55.5 [73] Cane molasses + urea 20 g/L Not mentioned Bacillus megaterium BA-019 49.9–55.5 [73] Molasses 1% Alkaline/acidic pre-treatment; Hydrothermal pre-treatment Cupriavidus necator (DSM 545 strain); 40 mL 27.20 [75] Molasses Not mentioned Not mentioned Bacillus subtilis 62.2 [77] Molasses Not mentioned Not mentioned Escherichia coli 58.7 [77] Molasses 2%−10%

(at even intervals)Sulfuric acid treatment and Tricalcium phosphate treatment B. subtilis (2 mL) 21.09−54.1 [77] Molasses 2–10 Tricalcium phosphate treatment B. subtilis (2 mL) 21.1−54.1 [77] Molasses 2−10 Tricalcium phosphate treatment E. coli 21.1−54.1 [77] Molasses 0−8 Acidic treatment Enterobacter cloacae 36.0–51.8 [78] Molasses − Acidic treatment Enterobacter cloacae (2–16) 44.2–53.7 [78] Molasses 2−10 Not mentioned Bacillus cereus SPV 61.1 [82] Molasses + corn steep liquor 2%−5% Not mentioned Bacillus megaterium 18.3−49.12 [87] Molasses + corn steep liquor 4 or

1%−6%, 0%−6%Pretreated with activated

charcoal (1:1) for 2 hBacillus megaterium ATCC 6748 35 [93] Molasses + corn steep liquor 4% (w/w); 4% (v/v) 43 Molasses 1% Not mentioned Bacillus thuringiensis IAM12077 23.81 [95] Bagasse 1% Bacillus thuringiensis IAM12077 9.68 [95] Molasses 10 and 40.0 g/L Acidic treatment Pseudomonases aregunoisa NCIM No. 2948 62.44 [96] Molasses − Sulfuric acid treatment Bacillus thurigenisis HA1 61.6 [97] − − Cupriavidus necator DSM 428 24.33 [98] − − Mixed microbial culture 57.5 [99] Molasses 0.0–0.5 g/L Not mentioned Alcaligenes eutrophus DSM 545 18–26 [100] Molasses 2–10 Not mentioned Bacillus flexus strain AZU-A2 88.0 [101] Application of sugar beet and sugar beet molasses for PHAs production

-

Sugar beet, a temperate root crop, is one of the most concentrated sources of sucrose that can be tapped for microbial fermentation and production of PHAs[102]. The juice of sugar beet has been utilized as a substrate for Azotobacter lactus, resulting in a 66% yield of PHAs against 80% using pure sucrose[103]. Sugar beet pulp has also been used as a carbon source, with pulp sugars sustaining Paraburkholderia sacchari to yield 62.2 g/L PHB with 53.1% content, a yield of 0.27 g/g, and productivity of 1.7 g/(L·h)[104]. Like sugarcane, sugar beet molasses, a residual effluent of processing with 50%–60% fermentable sugars, and other organics, is nutrient-dense and inexpensive for PHAs production (Table 2)[88]. Microorganisms like Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus megaterium, and Cupriavidus necator B-10646 utilize beet-derived substrates effectively[37]. Molasses hydrolysis with β-fructofuranosidase supported C. necator in converting 88.9% sucrose to hexoses, which resulted in 80–85 g/L biomass and polymer compositions close to 80%, while copolymer P(3HB-co-3HV) was formed from precursors such as propionate and valerate. Azotobacter vinelandii UWD produced copolymers having β-hydroxyvalerate through β-oxidation processes. Beet molasses has stimulatory compounds, presumably amino-N compounds, that enhance PHAs accumulation over biomass growth, with trace peptone addition further enhancing yields[37,105]. Sugar beet wastewater has also been used as an inexpensive medium, with 4.05 g/L PHAs (41.79% biomass) production with 6% molasses and ammonium oxalate, illustrating dual advantage of polymer production and COD elimination[106]. Together, sugar beet and residues offer an environmentally friendly, economically feasible pathway towards industrial PHAs production.

Table 2. Production of PHAs from sugar beet by-products.

By-product Concentration of

raw materialInitial treatment of

raw materialMicrobe utilized with inoculum concentration PHA yield (%) Ref. Beet molasses 40% Acid and enzymatic

hydrolysisCupriavidus necator B-10646 wild strain 80 [37] Beet molasses 5% w/v Not mentioned Azotobacter cinelandii UWD 75–85 [88] Beet juice 1 L Not mentioned Alcaligenes latus (ATCC 29714) 38.66 [103] Cane molasses + beet molasses 3% Not mentioned Bacillus megaterium strain L9 41 [105] Beet molasses + sugar beet waste water 1%–15%

(with odd intervals)Not mentioned Bacillus megaterium AUMC b 272 27.20–32.92 [106] Beet molasses 5% w/v Not mentioned Azotobacter vinelandii UWD (4% w/v) 65–73 [107] Sugar beet pulp 6% Recombinant endoglucanase (rCKT3eng) Haloarcula sp. TG1 17.8 [108] Pressed sugar beet pulp Not mentioned Acidification Pseudomonas citronellolis 38 [109] Pseudomonas putida KT2440 31 Application of corn grain, stover, and steep liquor for PHAs production

-

Corn and its derivatives are cheap and available feedstocks for the production of PHAs (Table 3). Corn syrup, obtained as a result of starch hydrolysis, is mostly glucose, offering an inexpensive and reliable source of carbon for microbial fermentation, whereas corn steep liquor (CSL), a wet-milled by-product, is rich in nutrients and increases polymer yields[110]. Other corn-derived substrates, such as grain, stover, oil, and gluten, have also been tested for the synthesis of PHAs[111]. While dextrose from corn grain is available as a reliable feedstock, its utilization competes with use in foods. Microbial fermentations via strains like Bacillus megaterium convert corn syrup sugars to PHAs effectively, and yields can be enhanced by optimizing aeration, temperature, and nutrient ratios. de Mello et al.[112] obtained 62% PHB accumulation (11.64 g/L, 0.162 g/L·h), which was raised to 70% (14.17 g/L, 0.197 g/L·h) in an 8-L bioreactor with milled corn hydrolysate and crude glycerol using Cupriavidus necator. Chaijamrus & Udpuay[94] produced 43% PHB with 4% molasses and 4% CSL. Recombinant E. coli carrying PHAs synthase genes stored PHAs from hydrolyzed corn starch, soybean oil, and cheese whey by using β-oxidation inhibitors such as acrylic acid[113]. Photobacterium sp. TLY01 gave 53.89 g/L PHB on corn starch and glycerol[114] and Bacillus sp. CFR 256 on CSL 8.20 g/L PHAs (51.2% biomass) in 72 h[115]. Acid-hydrolyzed corn cobs yielded 35.84 g/L reducing sugars, sustaining Bacillus sp. BM 37 to yield 36.2% PHB[116], although Pseudomonas aeruginosa resulted in only 0.38% PHB[117]. Moreover, Halomonas mediterranei produced PHAs from extruded corn starch and rice bran[118].

Table 3. Comparison of PHAs yield through different sugar rich feedstocks utilizing various microbial strains.

Other sugar rich feedstocks Concentration/weight of

raw materialInitial treatment of

raw materialMicrobe utilized with inoculum concentration PHA yield (%) Ref. Hydrolyzed citrus pulp Not mentioned Dilute acid hydrolysis Bacillus sp. strain COL1/A6 54.6 [2] Corn cob hydrolyzate 0.2, 0.5, and 1 g Acid hydrolysis Bacillus spp. BM 37 36.16 [119] Apple pulp waste 1:3 v/v deionized water Not mentioned Pseudomonas citronellolis NRRL B-2504 30 [123] Apple pulp waste 1:3 v/v deionized water Not mentioned Co-culture of Cupriavidus necator DSM 428 and Pseudomonas citronellolis NRRL B-2504 52 [124] Apple pulp waste 1:3 v/v deionized water Not mentioned Co-culture of Cupriavidus necator DSM 428 and Pseudomonas citronellolis NRRL B-2504 48 [124] Banana peels 20 g Not mentioned Zobellella sp. DD5 34.38 [125] Corn oil waste 20–50 mg Acidic treatment Pseudomonas sp. strain DR2 Up to 37.34 [126] Coir pith 3% Hydrolysis Azotobacter beijerinickii 48.9 [127] Ground orange juicing waste 10 mL Gas chromatography Cupriavidus necator H16 73 [128] Jackfruit seed hydrolysate 0.2 mL Enzymatic hydrolysis Bacillus sphaericus NCIM 5149 49 [129] Oil palm empty fruit bunch Not mentioned Enzymatic hydrolysis B. megaterium R11 51.6 [130] Apricots 10 g Enzymatic hydrolysis Pseudomonas resinovorans 1.4 [131] Corn stover hydrolysates also worked well, with Paracoccus sp. LL1 producing 9.71 g/L with 72.4% PHAs accumulation[119]. Corn bran hydrolysates were poor performers[120]. CSL and milk whey were used as co-substrates by E. coli strains that exhibited good P(3HB) yields, with K1060 performing the best. Commercially, Metabolix Inc. opened a 50,000-ton/yr PHAs plant in Iowa in 2010 from corn syrup[121]. However, extensive dependence on first-generation corn feedstocks is not sustainable. Farming of corn is costly from an environmental viewpoint, and life-cycle analyses indicate PHAs from corn do not lessen eutrophication or smog impacts compared to petrochemical plastics[122,111]. Future sustainability is contingent on combining enhanced PHAs fermentation technologies with sustainable production of corn.

Application of fruit waste and juices for PHAs production

-

Fruit and juice processing wastes are plentiful sugar-containing feedstocks ideal for the production of PHAs[132]. They harbour fermentable sugars like glucose, fructose, and sucrose[133,134], and comprise apple pomace, grape must, orange peels, mango pulp, and pineapple juice. Their valorization not only solves waste issues but also minimizes the environmental impact of fruit processing operations. Microorganisms like Haloferax mediterranei and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are shown to be able to produce PHAs from such wastes[135,136]. The operation generally includes pre-treatment and hydrolysis to break down fermentable sugars for easy microbial accessibility[137]. Despite this, inhibitory metabolites like phenolics can prevent growth and biosynthesis, the effects of which can be reversed by detoxification or microbial consortia[138]. Solid-state and submerged fermentation are both viable, although better yields are typically obtained under submerged systems[139]. Record yields are 56% PHB from pineapple juice[140], and 75% PHAs from oil palm frond juice[141] (Table 3). Pre-treatment processes like enzymatic hydrolysis or acid treatment enhances yields[142,143]. Seasonal and spatial availability of fruits guarantees a renewable feedstock, while waste conversion to resource supports circular economy principles and sustainable development objectives[144].

Application of sugar maple sap and syrup for PHAs production

-

Sugar maple syrup and sap, as unconventional ones, are promising sugar-dense feedstocks for PHAs production. Maple sap has high sucrose content, while syrup, its concentration, has even higher sugar content, which makes both candidates for microbial fermentation[145]. Although less is known about them, their high concentration, and purity of sugars offer potential for effective PHAs synthesis. Yezza et al.[145] used maple sap and Alcaligenes latus to synthesize poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) to attain yields of up to 78% dry weight of cells. The PHB produced had chemical, thermal, and spectroscopic properties that were similar to commercial sucrose-derived PHB. Lokesh et al.[146] also found that sap from felled oil palm trunks (OPT), which contained 5.5% w/v fermentable sugar, was a cheap renewable source of carbon. With a termite gut isolate, Bacillus megaterium MC1 yielded 3.28 g/L of P(3HB), which is equivalent to 30 wt% of cell dry weight. Talebian-Kiakalaieh et al.[147] showed that Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 17759 was able to grow on sugar maple hydrolysate and produce 51% 3-hydroxybutyrate. The seasonal nature of maple sap and syrup availability brings with it opportunities and challenges for PHAs production. Utilizing these substrates can increase the economic worth of the maple industry, and offer renewable substitutes to traditional sugar feedstocks for bioplastic production.

-

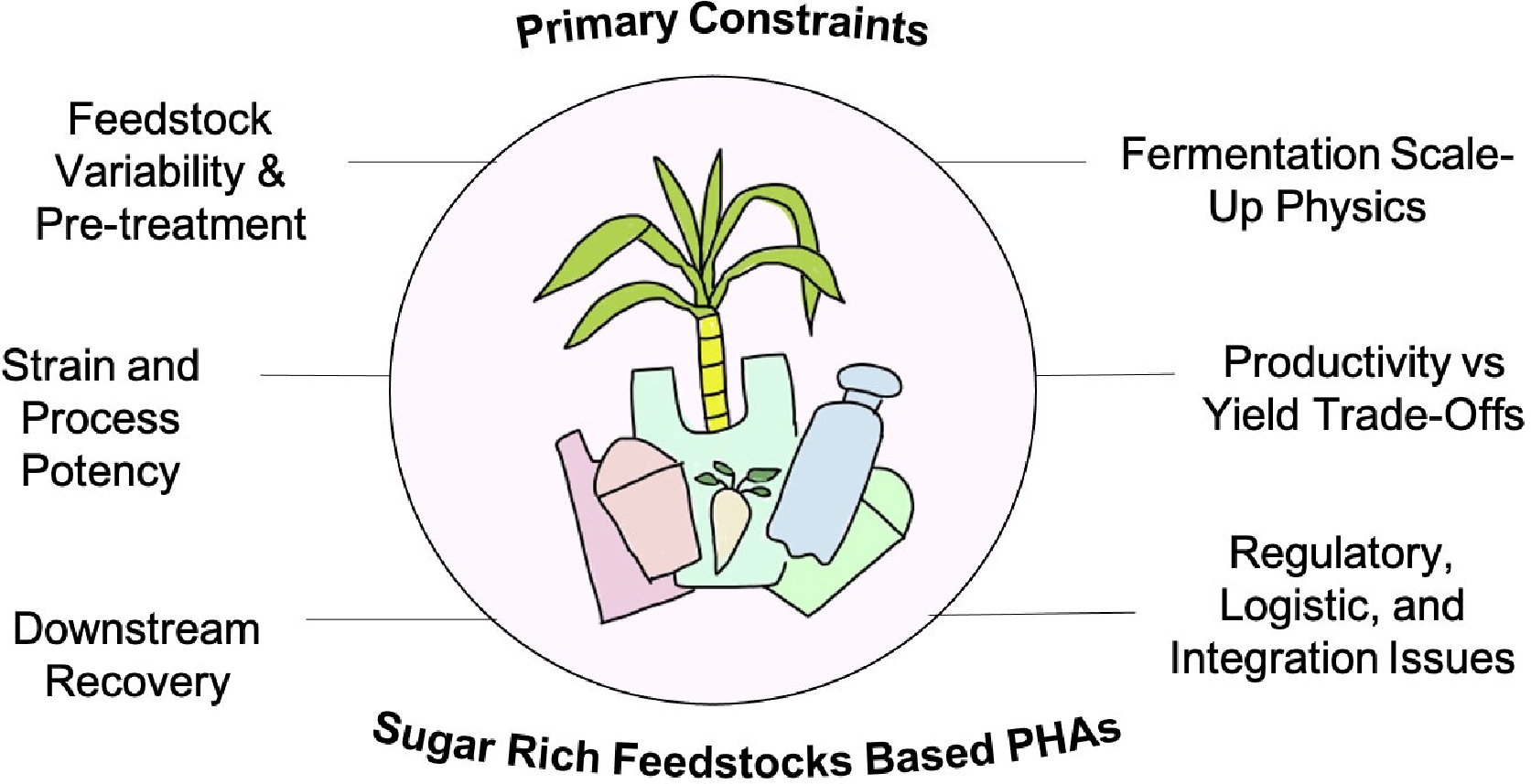

Scaling up laboratory results in the production of PHAs to industrial processes encounters serious economic, technical, and regulatory challenges. The cost-determining carbon substrates still contribute 30%–67% of the costs of production, and whereas laboratory work frequently employs pure glucose or sucrose, industrial viability hinges on the incorporation of low-cost, waste-derived feedstocks[30,148]. These residues are however accompanied by variability in sugar content, inhibitory substances, and nutrient imbalance, all contributing to decreased microbial efficiency and process stability. Industrial fermentation poses an added problem, where aeration, pH, temperature, and agitation are difficult to maintain uniformly in large-scale bioreactors, tending to result in metabolic diversion and decreased yields. Cost-saving measures like mixed microbial cultures, or open fermentation systems invite competition from unwanted microbes and degradation of PHAs. Sugar feedstocks such as molasses, bagasse, and vinasse have inconsistent composition and inhibitors and need uniform, low-cost pre-treatment to deliver consistent quality (Fig. 3). Non-optimized processes lower sugar yield and increase expense. Scale-up is confronted by oxygen transfer, mixing, and heat issues in achieving high-cell-density titres. Feedstock availability, waste valorization, regulation, and supply-chain integration complicate matters. PHA recovery is energy- and solvent-hungry, usually offsetting upstream expense, although new greener processes are untested at scale[149].

Downstream recovery exacerbates these problems; whereas solvent-based extraction is effective on a small scale, it is expensive, environmentally stressful, and less effective in bulk. Industrial purification hence requires new solutions that reconcile efficiency with sustainability. Lastly, ensuring product quality, safety, and environmental compliance is more challenging in the case of non-food-grade waste-based substrates. The elimination of such obstacles is critical for the commercialization of PHAs from potential laboratory materials to practicable industrial bioplastics[17,30].

-

PHAs have attracted considerable interest as eco-friendly substitutes for petrochemical plastics based on their similar material properties as well as their important environmental advantages[150]. Derived from sugar-based biomass, PHAs are biodegradable and can be degraded by microbes to water and carbon dioxide without leaving toxic residues[151,152]. In contrast to traditional plastics that last for centuries and result in plastic and microplastic pollution, PHAs biodegrade innocuously, lessening long-term environmental risks. Their application lowers landfilling, water pollution, and environmental persistence[153]. In addition, PHAs are not toxic and do not release toxic chemicals or microplastics upon decomposition[154]. Life-cycle analyses reveal that PHAs require lower energy and lower greenhouse gas emissions than traditional plastics. For example, the substitution of an equal weight of high-density polyethylene with PHA can save 2.9 kg of CO2 emissions, and 15 kg of emissions relative to polystyrene[155]. Such properties render PHAs an eco-friendly option for bioplastic manufacture and green material uses.

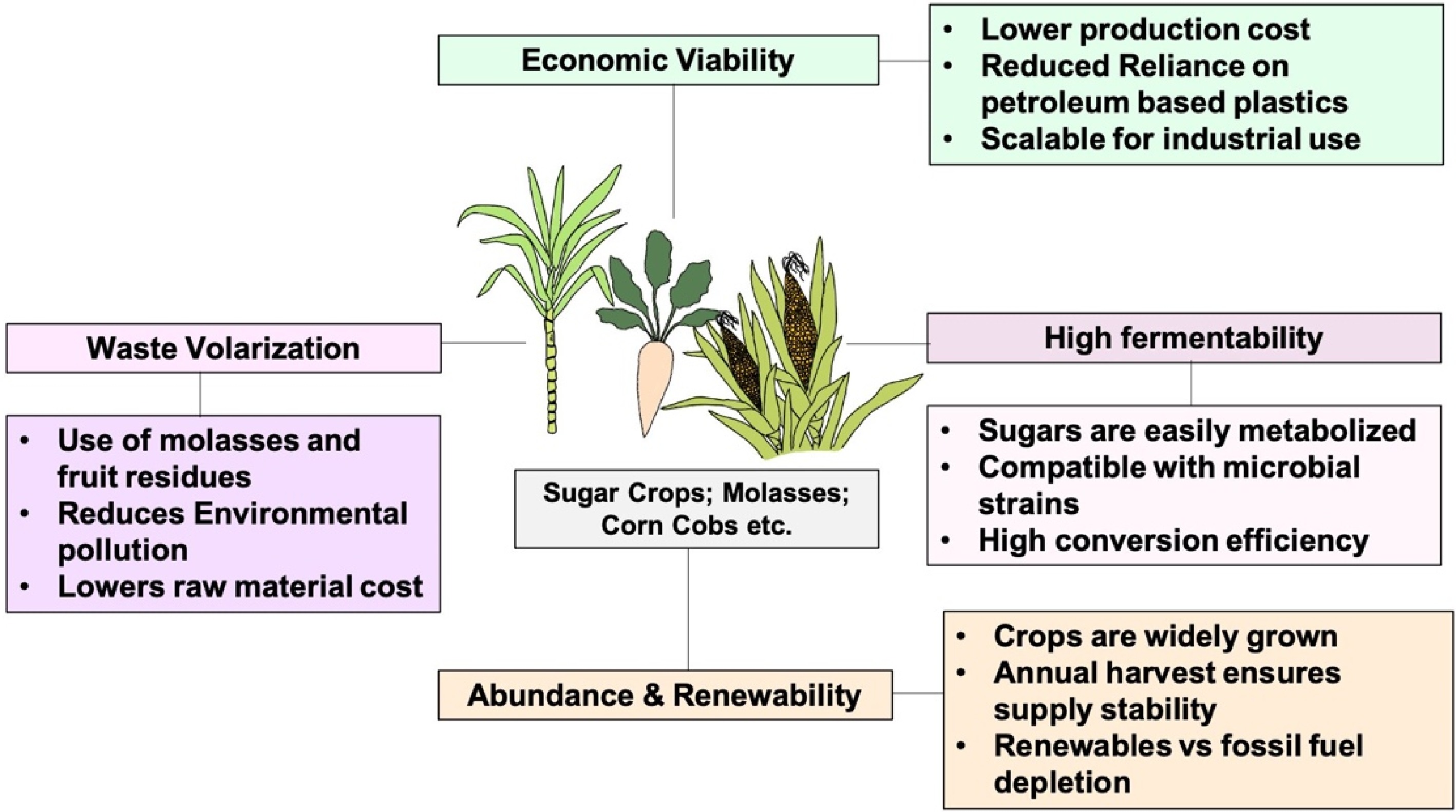

The sustainable source of PHAs from sugarcane, corn syrup, and similar carbohydrate-based feedstocks enhances the environmental status of PHAs by minimizing fossil fuel use and carbon footprints. Governments and industries seeking sustainable alternatives acknowledge PHAs as aligned with the principles of the circular economy, promoting resource efficiency and environmental care[156,157,13]. These benefits (Fig. 4) notwithstanding, economic limitations restrict their global adoption. High production expense, dictated in part by feedstock cost and accessibility, continues to be a stumbling block. Though sugarcane, corn syrup, and crop residues can be used as carbon substrates for microbial fermentation[152], challenges with food–feed competition, yield stability, and transport economics raise the cost of operations. Large-scale production entails technical limitations, especially fermentation and downstream processing, where big bioreactors need optimal oxygenation, pH regulation, and stable microbial growth to ensure productivity[158]. Downstream purification and separation are still costly, ranging from 30%–50% of overall costs[159]. Even though PHA prices have fallen from USD

${\$} $ ${\$} $ -

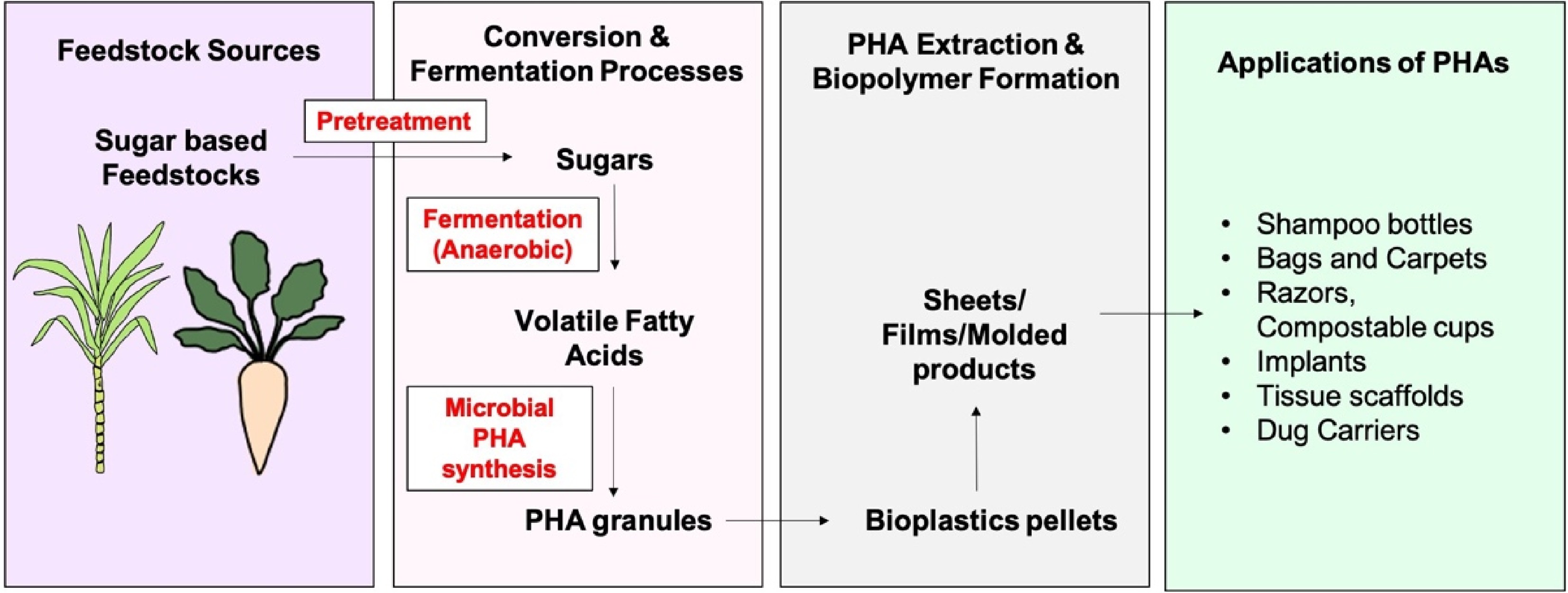

The conversion of agricultural residues and waste to value is increasingly being recognized (Fig. 5), as it de-prioritizes waste management infrastructure while recovering by-products as valuable resources in a closed loop[166]. PHAs play an important role by reducing plastic litter, improving resource efficiency, preventing climate change, and promoting circular economy measures[149]. Feedstocks like sugarcane bagasse, fruit peels, and molasses contribute carbon sources for microbial fermentation, lowering the dependence on virgin raw materials. Organic content in these wastes can be transformed into sugars and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) by anaerobic treatments[167]. But pre-treatment processes, although required to enhance accessibility, may increase expenditure and produce inhibitory compounds like furfural that lower PHAs yields[168]. Process parameter optimization and prevention of acidogenic inhibition are important to successful waste-to-PHAs conversion[169,170]. The major industrial uses of PHAs are in the packaging industry; e.g., poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (BIOPOL®) was used in shampoo bottles and cups[171], while poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH, Nodax™) is used in carpets and biodegradable bags[172]. Blending PHAs with natural fibres, such as sugarcane bagasse-reinforced PHB and PHBV composites, also found to have good mechanical and biodegradable properties[173,174]. In biomedical applications, PHAs find applications in drug delivery, implants, and tissue engineering[174,175]. PHB also possesses antimicrobial activity, inhibiting Vibrio infection in shrimp[176]. Some commercial activities involve Bio-on in Italy, which synthesizes PHAs polymers from sugar beet[177,155], and Bioextrax, which is producing PHAs from sugar beet feedstocks[178].

Figure 5.

Circular route of PHAs bioplastic production from sugar based feedstocks and its applications.

Agriculture is another prospective area. PHAs as mulches also help to improve water retention in the soil, minimize contamination, and increase yield[179]. In contrast to polluting polyethylene mulches that end up in landfills[180], degradable PHAs offer sustainable options[181]. They are best suited for films and coatings due to their low oxygen permeability, but their potential future applications can be PHAs-based growth bags. These bags reduce toxicity, minimize root deformities, and stimulate healthier plant development[182,183]. Due to their biodegradability and environmental friendliness, PHAs are suitable candidates for industrial and agricultural uses[149].

-

LCA is an extensive approach employed to assess the environmental effects of products, materials, or services throughout their life cycle, from the acquisition of raw materials to production, transportation, use, and waste. LCA is essential in researching PHAs, which are finding their way as eco-friendly substitutes to traditional plastics that remain in the environment as they are non-biodegradable[184]. PHAs, with origins in renewable sugar-based feedstocks, provide biodegradability, diversity, and lower dependence on fossil fuels, becoming central to sustainable material manufacture[22]. The majority of LCAs have turned their attention to the first-generation sugar feedstocks of corn glucose, sugarcane molasses, and sugar beet residues, considering environmental benefits and process hotspots, such as the energy-hungry chloroform-based extraction of PHAs. Interest is increasingly developing in second-generation waste-derived sugar substrates such as lignocellulosic hydrolysates, residues of food processing, and organic materials from wastewater, although few reports exist[185]. PHAs production from sugar sources continues to be expensive (USD

${\$} $ ${\$} $ -

PHAs produced from sugar feedstocks have adjustable mechanical properties, however these properties tend to vary from typical petrochemical plastics such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP)[186]. Homopolymers like PHB have high crystallinity (40%–70%), are rigid and brittle, with tensile strengths of 15 to 43 MPa, Young's modulus of 1–3.5 GPa, and elongation at break of 1%–15%, being susceptible to cracking when subjected to stress. Their hardness and restricted ductility are different from those of PE, PP, and other petroplastics. Monomer structure, chain length, and crystallinity are the factors controlling mechanical response, and these factors are further influenced by copolymerization or microbial fermentation to create medium-chain-length PHAs with softer and more flexible properties. Though less durable and thermally stable than high-performance petroplastics, these PHAs can retain favourable barrier properties, processability, and biodegradability. Thus playing a role in packaging, disposable items, and biomedical devices. Though copolymerization or blending strategies can enhance the flexibility and lower brittleness in sugar-rich feedstock-based PHA, the level of mechanical reliability as achieved in traditional plastics has not yet been attained. Since PHAs offer multifunctional biodegradable substitutes with added advantage towards eco-friendly product but its mechanical profiles need to be considered while using for specific applications[186].

-

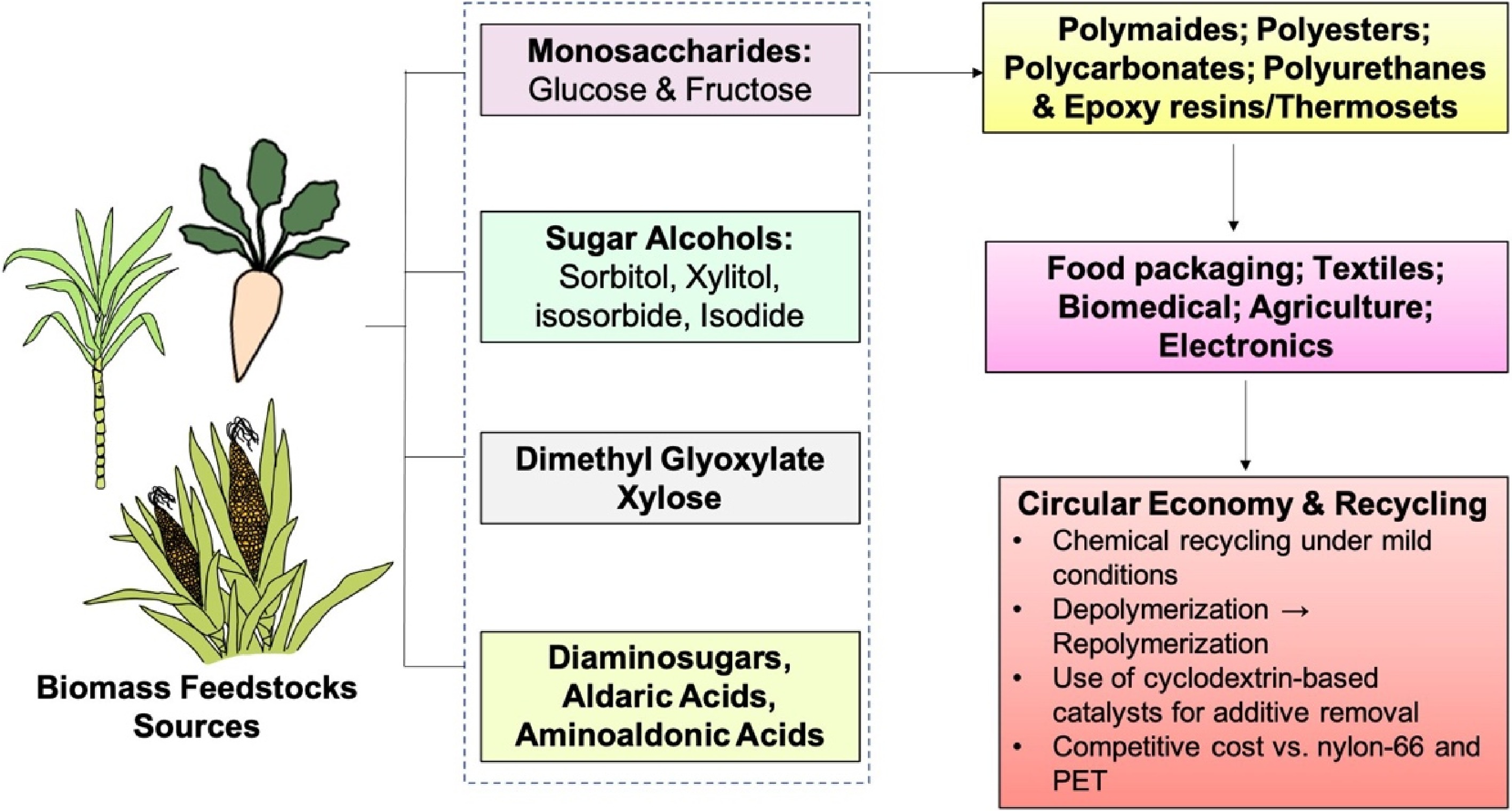

Polymers from sugar are a new generation of bioplastics with performance and environmental benefits compared to petroleum-based plastics[187]. Polyethylene furanoate (PEF), a product of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) derived from sugar, has a thermal behaviour comparable to polyethylene terephthalate (PET) but with ~10-fold reduced oxygen permeability (~0.0107 vs 0.114 barrer), thus best suited for food packaging[188]. Nonetheless, its application under pressurized conditions is limited by such disadvantages as brittleness and poor strain-hardening[189,190]. Sugars from biomass comprise of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and sugar alcohols, which are renewable, biodegradable, and versatile platforms for recyclable, high-performance polymers (Fig. 6) that overcome fossil-plastic limitations such as depletion of resources, environmental pollution, and carbon emissions[191,192].

Polyamides from diaminosugars, aldaric acids, and aminoaldonic acids have superior thermal and mechanical properties[191]. Polyamides from isosorbide possess tensile strength and thermal stability equivalent to or superior to typical nylons[193]. EPFL scientists accomplished catalyst-free conversion of xylose dimethyl glyoxylate into polyamides with 97% atom economy without harmful additives and maintaining toughness over recycling cycles[194]. Techno-economic studies indicate production costs are competitive with conventional nylons[195]. 2,5-Furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) from fructose is employed for the manufacture of polyethylene furanoate (PEF), having improved gas barrier properties compared to PET[196]. Sugar alcohols xylitol and sorbitol act as monomers for biodegradable polyurethanes and polycarbonates, imparting flexibility[197]. Isoidide- and isomannide-derived polymers synthesized at Duke University and the University of Birmingham exhibit tunable mechanical properties that vary from rubbery extensibility to nylon-like toughness because of stereochemical diversity[198].

Sugar monomers like sorbitol, glucose, and isosorbide have been combined with epoxy resins and thermosets to improve thermal stability and toughness[199]. Sugared furans offer petroleum-free renewable thermoset alternatives[200], and dynamic covalent chemistries allow for vitrimer-type thermosets with recyclability and re-shapability for use in the automobile and electronic industries[201,202]. Chemical modifications such as acetalization and etherification enable tuning of hydrophobicity, crystallinity, and rates of degradation. Their biocompatibility facilitates medical applications, and sugar polymers are able to condense into nanoparticles, micelles, and hydrogels for controlled drug delivery, including colon-specific release[203,204].

Cost and scalability are issues, but enzymatic and microbial production of sugar-based monomers, coupled with sugar biorefineries, increases feasibility. Recyclability tests show maintained tensile strength, and chemical recyclability under mild conditions[205]. Firms such as Bloom Biorenewables, a spin-off from EPFL, are working towards commercial-scale production. Sugar-based catalysts such as cyclodextrins improve upcycling and recycling by eliminating additives, maximizing yield and purity[206,207]. Generally, sugar-derived polymers such as polyamides, polyesters, polycarbonates, and epoxy resins provide adjustable functionality, recyclability, and compliance with circular economy doctrine, making them ideal for packaging, biomedical, and high-performance applications with prospects for sustainable reform of the plastics sector[208].

-

The application of PHAs have been reported in several areas, from daily use to specialized uses like in biomedicals. Research opportunities in PHAs production have been gaining speed with advancements in genome engineering techniques. Discovering alternative carbon sources is key to maintaining sustainable production methods. With the characteristics of renewability, abundance, microbial compatibility, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendly, the sugar rich feedstock have become essential for the sustainable and efficient production of PHAs with higher yields. These sugar-based substrates can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of PHAs compared to petroleum based substrates. Moreover, these also support the circular economy perspective by the creation of value-added products. The integration of these feedstocks in PHAs production processes through biotechnological tools have also impacted the existing agricultural practices and utilization of infrastructures in such processes. This shift results in more sustainable bioplastic manufacturing, compared to traditional ones. Additionally, since these feedstocks are obtained from waste/by-products of sugar-based crops, they are easily available in sufficient quantity, thus reducing the dependency on imported raw materials and supporting local economies. PHA production from these feedstocks is a positive and practical approach for the problem of plastic pollution and resource depletion, leading towards the attainment of sustainable development goals.

Though challenges still remain, the development in science has created further opportunities for the exploration of genetically engineered microbes in tailoring the properties of PHAs properties in several different fields such as packaging, biomedical devices, and agricultural films[209]. Another opportunity will be seen in the investigation of mixed culture fermentation systems and new bioreactor designs to maximize PHAs production from different feedstocks, such as agricultural waste and food waste in favour of waste valourization and circular economy approaches[210]. PHAs blends and composites with superior mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties also provide alternatives for environmental friendly plastics against conventional plastics. This will be driven by consumer and regulatory demand[211]. Interdisciplinary interactions and positive actions among academia, industry, and policy makers towards the adoption of these PHAs through these feedstocks will help in commercializing a green alternative product, reducing plastic pollution and promoting circular economy[212].

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, original writing, review and editing: Misra V, Mall AK. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data and information discussed are derived from previously published literature, which has been appropriately cited within the manuscript. No new datasets were created or analyzed during the preparation of this article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Varucha Misra, Ashutosh Kumar Mall

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Misra V, Mall AK. 2025. Exploiting sugar-rich feedstocks for sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate production. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0012

Exploiting sugar-rich feedstocks for sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate production

- Received: 13 August 2025

- Revised: 11 October 2025

- Accepted: 13 October 2025

- Published online: 15 December 2025

Abstract: Plastic pollution is an international issue, with petrochemical plastics promoting waste build-up, aquatic ecosystem impairment, and microplastic pollution. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) have gained a lot of attention as an alternative material owing to their similar mechanical characteristics to traditional plastics, together with biodegradability and ecological inertness. These bacterial biopolymers, which are polymerized by bacteria like Cupriavidus necator and Bacillus megaterium as intracellular carbon and energy stores, can be made from biotic feedstocks, aligning with circular economy and sustainability objectives. The main limitation to mass adoption is high production price, which is generally determined by substrate cost. Sugar-rich feedstocks such as sugarcane molasses, beet molasses, and corn syrup have the potential to cut costs by 30%–40% relative to glucose-based fermentation. The use of agro-industrial by-products not only reduces raw material expenses but also favours waste valorization as well as local economic advantages. The efficiency of production is greatly influenced by process parameters and feedstock properties, wherein optimization of pH, dissolved oxygen, and carbon-to-nitrogen ratios greatly improves yield and polymer quality. Additionally, PHAs blends and composites with enhanced thermal, mechanical, and barrier properties present suitable solutions for packaging and allied applications. With growing consumer consciousness and regulatory demands, PHAs from sugar feedstocks offer both economic and ecological benefits. Engineered microbial strains and inexpensive downstream processing are future work priorities for scalable and sustainable production. The present review examines the viability of using sugar-rich substrates as economically viable feedstocks to produce PHAs and their role in the development of sustainable bioplastics.

-

Key words:

- Sustainability /

- Circular economy /

- Bioplastics /

- Sugar rich feedstocks /

- Sugarcane /

- Sugar beet /

- Life cycle assessment /

- Polymers