-

Hepatic fibrosis is a response to, and usually follows long-term injury, including viral infection, autoimmune insult, alcohol abuse, metabolic disorder, toxicant damage, drug exposure, and cholestasis. It may eventually progress to irreversible and decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[1,2]. Pharmacological intervention is essential for reversing liver fibrosis. However, thus far, no drug has been approved[3].

Major challenges in drug development have prompted extensive studies on the pathology and mechanism of liver fibrogenesis. This pathological process is characterized by the continuous accumulation of fibrosis-related proteins, such as collagen type 1 alpha 1 (Col1a1) and collagen type 1 alpha 2 (Col1a2). These extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins can replace damaged liver tissue and form fibrous scars, ultimately leading to the development of liver fibrosis[4]. Various cell types significantly contribute to the generation of ECM, and activated HSCs are the main and direct sources and effectors. When liver diseases occur, hepatocytes are damaged first and release damage signals, activating Kupffer cells and recruiting other inflammatory cells[5]. Extracellular signals, including transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), drive the transformation of HSCs from quiescent phenotype into activated and fibrogenetic phenotype. Various intracellular events and signaling pathways, including TGFβ-SMAD signaling, signaling by PDGF and its receptor, hedgehog signaling, retinol metabolism, epigenetic changes, and receptor-mediated signaling, occur[6]. The involvement of these extracellular and intracellular pathways reveals the tremendous complexity of the processes of HSC activation and fibrosis development. Monotherapies are unable to target these complex signals and alleviate hepatic fibrosis. It seems logical that combination therapies that target distinct pathological signals would have substantially better efficacy[7].

Phenotype-based screening is an unbiased approach for identifying drug candidates for various diseases, especially those with complex pathogeneses, and those involving multiple targets. Natural products are the most valuable source for drug discovery and development, and plenty of drugs are developed from natural products. Nevertheless, natural products also present challenges in terms of drug development, such as weak pharmacological activity[8,9]. Identifying potentially efficacious drug combinations via phenotype-based screening of natural products is a promising approach for developing powerful treatments for liver fibrosis[7,10].

Silybin is a flavonoid compound extracted from milk thistle with various functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammation, and anti-apoptosis. Therefore, silybin is clinically used for the therapy of chronic liver diseases, such as alcohol-associated liver disease, drug-induced liver injury, as well as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease[11,12]. Since these injuries can progress into liver fibrosis, silybin could indirectly rescue hepatic fibrosis. Additionally, its antifibrotic effect has been evaluated in various animal models and cultured HSCs. However, its effect in inhibiting HSC activation was not so prominent so as to significantly improve to liver fibrosis[13,14].

In this study, the aim was to identify a combination regimen for the therapy of hepatic fibrosis. A collagen reporter-based screening system was used to identify drugs among hundreds of FDA-approved drugs that could be combined with silybin to treat liver fibrosis. Silybin and carvedilol were found to significantly synergistically suppress HSC activation and fibrosis development. Moreover, the dosage ratio between silybin and carvedilol was systematically evaluated, and a fixed-dose combination (50:1 for silybin and carvedilol) with strong synergy, was developed. This combination inhibited liver fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner. Mechanistically, they synergistically suppressed HSC activation by inhibiting Wnt4/β-catenin signaling. This study provides a perspective candidate combination regimen for liver fibrosis.

-

Silybin (XH2021012501) was purchased from Nanjing Xinhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Silybin capsules were obtained from Tasly Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Obeticholic acid (OCA, O10013) was purchased from Beijing Psaitong Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). TGFβ1 protein (Human, HY-P70543), Carvedilol (HY-B0006), actinomycin D (ActD, HY-17559), thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (HY-15924), 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, HY-D0940), and all the screened drugs were obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, USA). Tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (tBHP, M25623) was obtained from Mindray Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) was purchased from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Mineral oil (M8410) was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (Marlborough, USA).

Collagenase IV (C5138) and pronase E (P5147) were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich. Nycodenz (1002424) was purchased from Shanjin Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα, 300-01A) was obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, USA). A rabbit anti-collagen I/COL1A1 pAb (A1352), a rabbit anti-collagen III alpha 1/COL3A1 pAb (A3795), and a rabbit anti-α-Smooth Muscle Actin (ACTA2) mAb (A17910) were purchased from ABclonal Technology (Wuhan, China). β-Catenin Antibody (9562) and Phospho-β-Catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) Antibody (9561) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 (A-21206), Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (L3000015), and lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (13778150) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, USA).

RNAiso Plus reagent was purchased from TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). CCK-8 Cell Counting Kit (A311-01), HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (R222-01), ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q331-02), and Duo-Lite™ Luciferase Assay System (DD1205-01) were purchased from Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Rat WNT1, WNT2B, WNT4, WNT5A, WNT5B, WNT7A, WNT8A, WNT8B, and WNT11 ELISA Kits were purchased from Xinyu Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture and treatment

-

Human HepG2 cells and human HEK293T cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Human LX-2 cells were purchased from Wuhan Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China). Rat HSC-T6 cells were purchased from the Central South University Advanced Research Center (Changsha, China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Apoptosis was triggered by ActD (0.4 μM) and TNFα (20 ng/mL) for 12 h, as previously described[15]. Inflammation was triggered by incubation with TNFα (100 ng/mL) for 3 h[16]. Oxidative stress was caused by incubation with tBHP (600 μM) for 4 h[17]. LX-2 cells and HSC-T6 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 24 h to establish a model of HSC activation.

To evaluate the effects of silybin on apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and HSC activation, cells were treated with 10, 20, or 50 μM silybin.

Analysis of cell viability by the MTT assay

-

Cells were grown in 96-well plates, and cell viability was determined by an MTT assay. The cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT for 3 h. Afterward, the formazan was extracted from the pelleted cells with 150 μL of DMSO for 10 min. The amount of formazan was then determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm.

Detection of ROS with a fluorescent probe

-

Cells were inoculated in copolymerized microplates and incubated with 10 μM H2DCFDA at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min. Images were immediately taken using a laser confocal microscope after the culture medium was discarded. Six to eight fields were randomly selected from each group, and the fluorescence signals were analyzed with ImageJ. To quantitatively analyze the effect of silybin on oxidative stress, the cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution and incubated with 10 μM H2DCFDA solution at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min. The fluorescence signal was measured immediately using a multifunctional microplate reader at Ex/Em = 488/525 nm, and the number of viable cells was determined with the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay following the manufacturer's protocol.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT−qPCR)

-

Total RNA was extracted from tissue and cells using RNAiso Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was precipitated by washing with 75% ethanol and then dissolved in DEPC water. cDNA was obtained through reverse transcription using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR. ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix was used for RT‒qPCR on a CFX Connect Fluorescence Quantitative PCR instrument. The mRNA expression levels of the target genes were normalized to those of GAPDH[18]. The primers (Invitrogen) used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Drug screening based on COL1A1-luciferase reporter gene activity

-

The empty pEZX-FR03-hygro plasmid and PEZX-FR03-Hygro-COL1A1-WT plasmid were constructed by Qingke Biotech (Beijing, China). LX-2 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a white 96-well cell culture plate with a clear bottom (WP96-4WCSSH, αplus). After 18 h of cell culture, the cells were transfected with the COL1A1 reporter gene plasmid at a concentration of 0.1 μg of plasmid per well. After 6 h of transfection, the cells were treated with the drug for 12 h, after which the Duo-Lite™ Luciferase Assay System was used to measure the luminescence[18].

pHSCs isolation and treatment

-

pHSCs were isolated by pronase/collagenase digestion followed by density gradient centrifugation with Nycodenz and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. The purity of the HSCs was detected by autofluorescence. Twenty four h after seeding, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After isolation from the rats, the cells were cultured on plastic dishes for 3 d for spontaneous activation until they acquired a myofibroblast-like phenotype. Cells that were cultured for one day, which maintain a non-proliferative and quiescent phenotype, were used as the negative control[19]. They were then treated with the individual or combined silybin (25 μM), and carvedilol (10 μM) for 12 h. RT‒qPCR or immunofluorescence was conducted to examine the in vitro activation of the HSCs.

Immunofluorescence assay

-

Cells in a confocal microplate were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, followed by blocking with 5% BSA solution at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight and incubated with secondary antibody at 37 °C for 1 h. After the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, an LSM700 laser confocal microscope was used for cell imaging.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

-

Supernatants from pHSC were concentrated using an ultra-filtration centrifuge tube (10 kDa, UFC8010, Millipore, Boston, USA). The retentate (concentrated supernatant) was collected for further analysis. Protein levels of Wnt ligands in pHSC supernatants were measured using the Rat Wnt ligand ELISA Kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids and cell transfection

-

Negative control siRNA, Wnt2b siRNA, Wnt4 siRNA and Wnt11 siRNA were obtained from Yike Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Transfection with siRNA was performed using lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Wnt4-Rattus norvegicus_pcDNA3.1(+)-N-eGF plasmid was obtained from Genscript Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). HEK293T cells were plated at 1 × 106 cells in 10-cm cell culture dish, and the transfection Wnt4 plasmid was performed with Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell conditioned medium was collected 48 h after transfection unless stated otherwise.

Animals and treatment

-

Male C57BL/6J mice, aged 8 weeks and weighing 20–22 g, were obtained from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China). The temperature was maintained at 20 ± 2 °C, and the relative humidity was 50% ± 10%; the animals were housed on a 12 h day‒night cycle and given free access to food and water. All the animal experiments performed in the study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University.

Effect of silybin on CCl4-induced acute liver injury. To evaluate the effect of silybin on liver injury, mice were orally administered 50 or 150 mg/kg silybin or 5 mg/kg OCA for 5 consecutive days. At 0.5 h after drug administration on the 4th d, the mice were intraperitoneally injected with CCl4 (1 mL/kg). Twenty-four hours later, the animals were sacrificed.

Effect of different dose ratios of silybin and carvedilol on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. To determine the optimal dose ratio of silybin and carvedilol for improving liver fibrosis, mice were intraperitoneally injected with CCl4 (0.1 mL/kg), twice a week for 6 weeks. From the 3rd week, the mice were orally administered silybin and carvedilol alone or together for 4 weeks. The doses of silybin were 50, 75, and 100 mg/kg. The dose of carvedilol was 2 mg/kg. At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed.

Effect of the optimal ratio of silybin and carvedilol on CCl4-caused fibrosis. To validate the combination at the optimal ratio (100 mg/kg silybin and 2 mg/kg carvedilol) for alleviating liver fibrosis, following the same procedure above, we injected mice intraperitoneally with CCl4 (0.1 mL/kg), twice a week for 6 weeks. From the 3rd week, the mice were orally administered 100 mg/kg silybin and 2 mg/kg carvedilol alone or together for 4 weeks. At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed.

Effect of fixed doses of silybin and carvedilol on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. To investigate the effects of fixed doses of silybin and carvedilol on liver fibrosis, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with CCl4 (0.1 mL/kg), twice a week for 6 weeks. From the 3rd week, the mice were orally administered a combination of silybin and carvedilol for 4 weeks. The dose ratio of silybin and carvedilol was fixed at 50:1. The combination doses were as follows: 102 mg/kg (silybin 100 mg/kg and carvedilol 2 mg/kg), 153 mg/kg (silybin 150 mg/kg and carvedilol 3 mg/kg), and 204 mg/kg (silybin 200 mg/kg and carvedilol 4 mg/kg). OCA at 1.5 mg/kg was used as a positive control. At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed.

Serum biochemical analysis

-

Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were measured using an enzyme detector in accordance with a kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (JianCheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Histological analysis

-

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver sections was performed for histopathological evaluation. Sirius Red staining and Masson's trichrome staining of liver sections were performed for assessment of liver fibrosis by an experienced pathologist blinded to the experiments. Histopathological changes, including hepatocellular edema, necrosis, increased mitotic figures, steatosis, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and fibroblast proliferation, were evaluated based on a semi-quantitative scoring system (0−3), adapted from previous studies. Liver fibrosis was graded based on the established Ishak scoring system[20]. The total histology score was calculated as the sum of all individual item scores.

Western blot (WB) analysis

-

The protein samples were separated on the basis of their molecular weights using SDS−PAGE. Afterward, the separated protein bands on the gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane via semidry transfer. The membrane was subsequently treated with 5% BSA blocking solution. The membrane was subsequently incubated with specific primary antibodies and the corresponding secondary antibodies. Finally, chemiluminescence substrate was added for development, and the signals were visualized using an imaging system for qualitative and semiquantitative analysis of the target protein.

RNA-seq analysis

-

pHSCs were obtained from rats and cultured in vitro for 3 d. After subsequent processing, cell samples were collected. After total RNA was extracted and purified, oligo (dT) magnetic beads were used to enrich mRNA, and an rRNA removal kit was used to remove ribosomal RNA. The purified mRNA was fragmented at high temperature into short fragments, which were subsequently used as templates to synthesize cDNA. First, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers, and then double-stranded cDNA was synthesized under the action of DNA polymerase I and RNase H. Double-stranded cDNA was purified and subjected to end repair, the addition of an A tail, and the ligation of sequencing adapters. Fragments of the ligated products were selected by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the target-sized fragments were recovered and amplified by PCR for library construction. Quality control of the library was performed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and the qualified libraries were sequenced on the BGISEQ-500 sequencing platform. DNA nanoball (DNB) technology and combined probe anchor polymerization (cPAS) sequencing principles were used for high-precision, highly reproducible, and wide dynamic-range quantitative analysis of gene expression at the whole-transcriptome level.

Analysis of the combined effect index

-

By using CompuSyn software for analysis, the combination index (CI) value was obtained. A CI value of 0.90 < CI < 1.10 indicated that two substances had an additive effect, whereas a CI value less than 0.90 indicated a synergistic effect. Moreover, the smaller the CI value was, the stronger the synergistic effect[21].

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The data are expressed as the means ± SEMs. Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using a two-tailed Student's t-test, while comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Newman‒Keuls post hoc analysis. p value < 0.05 indicated that the differences were statistically significant.

-

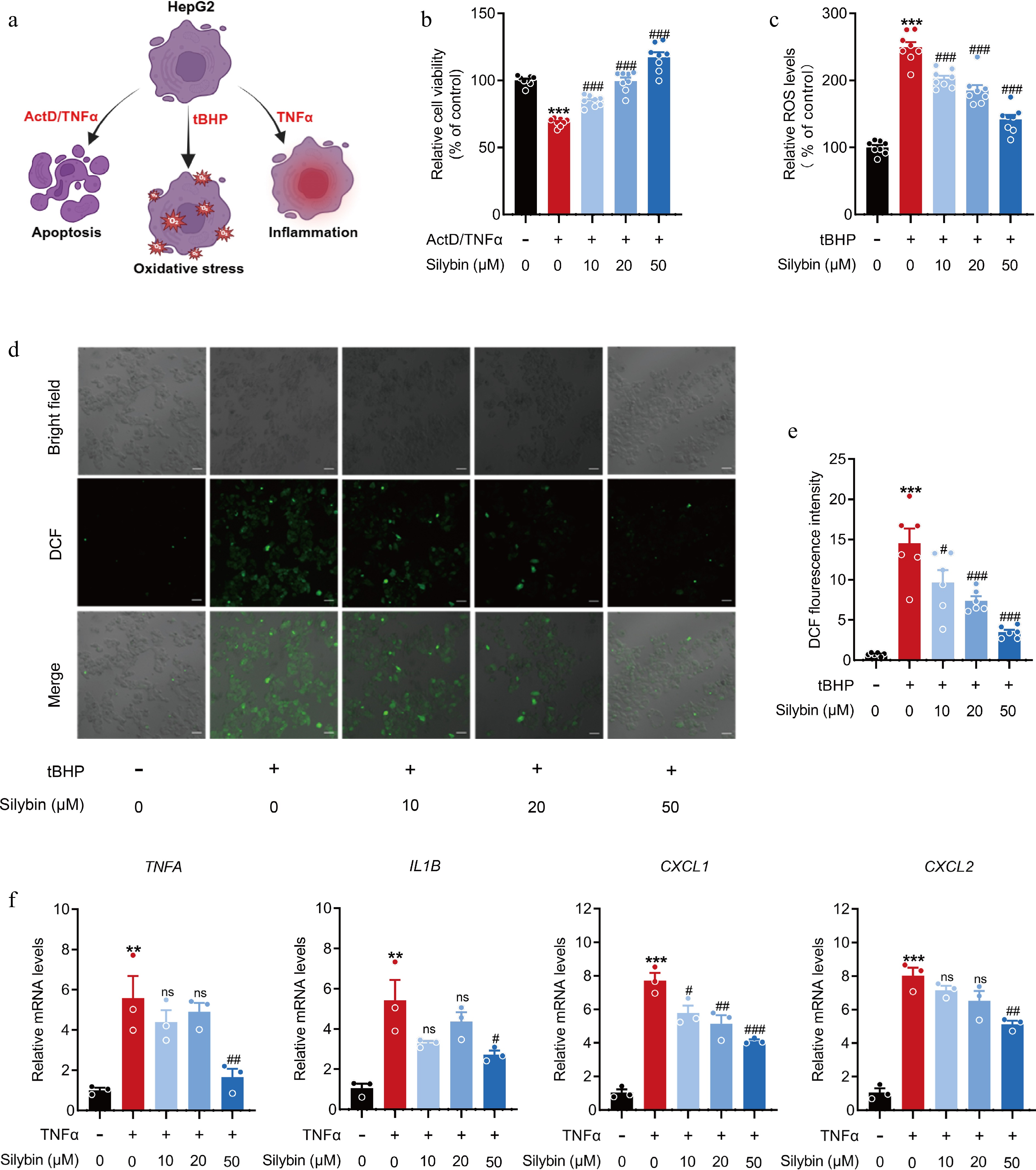

Silybin is a famous hepatoprotective herbal drug and is widely used for the therapy of various liver diseases. Metabolic disorders, hepatocellular apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response are central hallmarks of hepatic injuries[11]. The intension was to characterize the hepatoprotective effect of silybin (Fig. 1a). Hepatocellular apoptosis was triggered by incubation with ActD/TNFα, which caused a robust reduction in cell viability. Treatment with 10, 20, or 50 μM silybin significantly restored cell viability (Fig. 1b), supporting the strong antiapoptotic effect of silybin. Hepatocellular oxidative stress was triggered by incubation with tBHP, which markedly increased ROS levels. Treatment with silybin significantly reduced the intracellular ROS concentration in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). Image analysis and semiquantitative analysis of ROS levels also visually supported the antioxidant effect of silybin (Fig. 1d & e). The inflammatory response was caused by treatment with TNFα, which manifested as increases in the mRNA expression of TNFA, IL1B, CXCL1, and CXCL2. As might be expected, treatment with silybin, ranging from 10 to 50 μM, markedly inhibited the mRNA expression of the abovementioned inflammation response-related genes (Fig. 1f), demonstrating the favorable anti-inflammatory effect of silybin. Cytotoxicity has been assessed for all concentrations of silybin used in above treatments, thus ensuring that the observed effects were not attributable to compromised cell viability (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Additionally, we previously provided solid evidence of the ability of silybin to reduce lipid accumulation[22]. Taken together, the above results indicate that silybin has antiapoptotic, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects, exhibiting a systematic description of the ability and characteristic of silybin in treating liver diseases.

Figure 1.

Effects of silybin on hepatocellular apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidation. (a) Scheme on the characterization about the hepatoprotective effect of silybin. (b) Relative cell viability detected by MTT (n = 8). (c) Relative ROS levels (n = 8). (d), (e) Representative immunofluorescence images of ROS (d, scale bar, 50 μm) and average fluorescence intensity (e, n = 6). (f) Relative mRNA levels of TNFA, IL1B, CXCL1, CXCL2 in HepG2 cells (n = 3). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs control, and # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

Suboptimal attenuation of HSC activation and collagen deposition by silybin

-

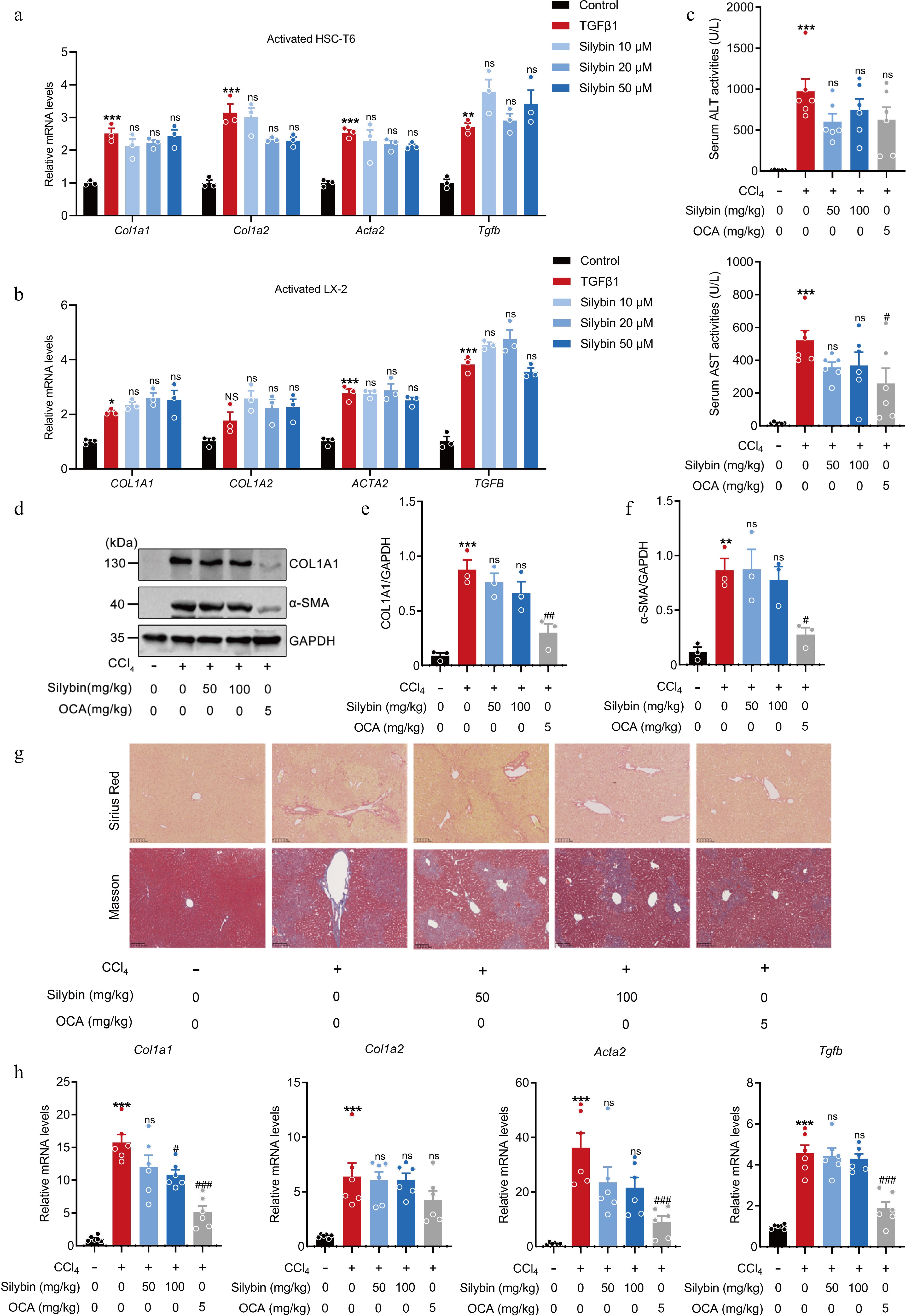

Crosstalk between hepatocytes and HSCs promotes the progression of acute or chronic liver diseases to fibrosis. Injury of hepatocytes promotes the transformation of HSCs from quiescent phenotype into activated phenotype, key drivers of fibrosis[4]. To clarify the underlying effect of silybin on fibrosis, its effect on HSC activation were investigated. Both human-derived LX-2 cells and rat-derived HSC-T6 cells were treated with TGFβ1 and incubated with 10 to 50 μM silybin. Similarly, silybin (10, 20 and 50 μM) was verified to be non-cytotoxic to HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells prior to investigation (Supplementary Fig. S1b, S1c). However, the mRNA expressions of COL1A1, COL1A2, α-smooth muscle actin (encoded by ACTA2), and TGFB were marginally inhibited by silybin (Fig. 2a, b).

Figure 2.

Effect of silybin on HSC activation and hepatic collagen deposition. (a), (b) Relative mRNA expressions of COL1A1, COL1A2, ACTA2, and TGFB in HSC-T6 cells (a, n = 3), and LX2 cells (b, n = 3) treated with TGFβ1. (c) Serum ALT and AST levels (n = 6). (d) Representative Western blot images, and (e), (f) semi-quantification of COL1A1 and α-SMA proteins in liver tissues (n = 3). (g) Representative Sirius Red and Masson staining of liver tissues (n = 6, scale bar, 100 μm). (h) Relative mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, Acta2, and Tgfb in liver (n = 6). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs control, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

These results demonstrate that silybin fails to directly inhibit HSC activation. However, some previous studies have demonstrated that silybin can rescue liver fibrosis[23]. The possible effect of silybin on HSC activation was further tested in mice. The results of serum biochemical analyses indicated that treatment with silybin produced only a modest reduction in serum ALT and AST levels (Fig. 2c), but the effect of it failed to achieve statistical significance. Assessment of COL1A1 and α-SMA protein levels in the liver tissue revealed that silybin did not exert a significant effect on these major protein components of collagen deposition in the acutely injured liver and was markedly weaker than that of OCA (Fig. 2d−f). Masson and Sirius Red staining of liver tissues revealed that intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 led to conspicuous collagen deposition, manifested as collagen staining radiating from the central vein to the periphery and the distribution of a large amount of collagen within the liver lobules. However, silybin administration slightly alleviated this pathological change (Fig. 2g). Consistent with these findings, CCl4 injection caused distinct increases in the mRNA expressions of Col1a1, Col1a2, Acta2, and Tgfb. Silybin administration at 50 and 100 mg/kg slightly reduced the expression of these mRNAs (Fig. 2h). The above results hint that the weak antifibrotic efficacy of silybin might be derived mainly from its effects on hepatocellular oxidative stress, inflammation, or cell death.

The combination of silybin and carvedilol synergistically inhibits HSC activation

-

Silybin has long been used as a remedy for liver fibrosis and other liver diseases[11]. However, the abovementioned results demonstrate that the antifibrotic effect of silybin is significantly weaker than its hepatoprotective effect. Drug combinations can provide advantages over monotherapies in the treatment of chronic and multifactorial diseases, including liver fibrosis[7]. Considering the characteristics of silybin against liver diseases, the development of a combination regimen involving silybin for the treatment of liver fibrosis was proposed.

A COL1A1-luciferase reporter gene system was developed to evaluate HSC activation, and the combination index (CI) based on the luminescence, was calculated to elucidate the potential synergistic effect of silybin combined with other drugs (Fig. 3a). Silybin was combined with 397 FDA-approved drugs, and eight of the combinations showed potential additive or synergistic effects against liver fibrosis (Fig. 3b). The drugs used in combination with silybin and their CI values are as follows: carvedilol (CI = 0.13), aceclofenac (CI = 0.46), valsartan (CI = 0.47), manidipine (CI = 0.51), D-mannitol (CI = 0.66), cilnidipine (CI = 0.77), clobetasol (CI = 0.86), and desonide (CI = 0.91) (Fig. 3c). The combination of silybin and desonide showed an additive effect in inhibiting HSC activation, and the others showed synergistic effects. The combination of silybin and carvedilol had the most potent inhibitory effect and the strongest synergistic effect on HSC activation (Fig. 3d). These effects were further tested by measuring the protein expression of COL1A1 and COL3A1, which are other main collagen components of the ECM. Their protein levels were slightly reduced by either silybin or carvedilol alone. However, their levels were significantly reduced by the combination therapy (Fig. 3e–h). Additionally, incubation of pHSCs with silybin combined with carvedilol significantly inhibited the transcription of Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2 (Fig. 3i). Notably, effect on cell viability was excluded for concentration combinations of 10 μM silybin with 10 μM carvedilol and 25 μM silybin with 10 μM carvedilol in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S1d). These results collectively indicate that the combination of silybin and carvedilol significantly and synergistically inhibits HSC activation.

Figure 3.

Silybin and carvedilol synergistically inhibit HSC activation. (a) Scheme about the screening system of drug combinations based on COL1A1 luciferase reporter. (b) Inhibition ration of COL1A1 luciferase by combined silybin and FDA-approved drugs. Red dots represent synergistic drugs, blue dots represent additive drugs, black dots represent non-synergistic drugs. (c) CI values by representative drugs and silybin on COL1A1 luciferase activity. (d) Relative COL1A1 luciferase activity by carvedilol and silybin in LX-2 (n = 5). (e)−(h) Representative images of immunofluorescent staining and semi-quantitative analysis of COL1A1 (e), (f) and COL3A1 (g), (h) in pHSCs (n = 6, scale bar, 50 μm). (i) Relative mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Acta2 in pHSCs (n = 3). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, *** p < 0.001 vs control, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

Effects of different dose ratios of silybin and carvedilol on HSC activation and fibrosis development

-

Preliminary screening and subsequent verification confirmed that silybin and carvedilol have synergistic inhibitory effects on HSC activation. The strength of the synergistic effect is also determined by the dose ratio between the components. Their dose ratio with optimal synergistic effect was then evaluated in cultured cells and animals.

The dose ratio between silybin and carvedilol was set from 1:8 to 8:1. Specifically, 10 μM silybin was combined with 1.67, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 μM carvedilol. Moreover, 10 μM carvedilol was combined with 1.67, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 μM silybin. CI values less than 0.3, which indicated strong synergy, were calculated for the dose ratio of silybin (10 μM) to carvedilol of from 1:1 to 1:8. Moreover, as the carvedilol dose increased, the inhibitory and synergistic effects significantly increased (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, CI values less than 0.1, which indicated extremely strong synergy, were calculated when the dose ratio of carvedilol (10 μM) to silybin was from 1:1 to 1:8. Similarly, as the silybin dose increased, the inhibitory and synergistic effects significantly increased (Fig. 4c, d).

Figure 4.

Evaluation on the dosage ratio between silybin and carvedilol to significantly synergistically inhibit HSC activation and fibrosis development. (a) Relative COL1A1 reporter luciferase activities, and (b) the CI values by combined silybin (10 μM) and carvedilol (1.67−80 μM) (n = 5). (c) Relative COL1A1 reporter luciferase activities, and (d) the CI values by combined carvedilol (10 μM) and silybin (1.67−80 μM) (n = 5). (e) Mouse experiment procedure scheme. (f) Serum ALT and AST levels (n = 6). (g) Representative images of H&E, Sirius Red, and Masson staining of liver sections (n = 6, scale bar, 100 μm). (h) Pathological injury scores on H&E staining of liver sections (n = 6). Liver fibrosis analysis by (i) CVF, and (j) Ishak scores of the Masson staining of liver sections (n = 6). (k) mRNA levels of fibrotic genes (n = 6). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs control, # p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01,### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

The optimal dose ratio for antifibrotic effects was further evaluated in animals with liver fibrosis. The mice were orally administered silybin or carvedilol alone, or their combination. The dose of carvedilol was 2 mg/kg, while the doses of silybin were 50, 75, and 100 mg/kg (Fig. 4e). As expected, combined treatment with silybin and carvedilol caused reductions in serum ALT and AST levels. Moreover, the most significant reductions were observed in mice treated with 2 mg/kg carvedilol and 100 mg/kg silybin (Fig. 4f). Additionally, H&E staining revealed that many inflammatory cells aggregated and obvious hepatocyte death occurred in the livers of mice treated with CCl4. These pathological changes were obviously ameliorated by the combination therapy. Moreover, superior improvements were observed in animals administered with 2 mg/kg carvedilol and 100 mg/kg silybin (Fig. 4g, h). In line with these results, Masson and Sirius Red staining further confirmed that combined treatment with 2 mg/kg carvedilol and 100 mg/kg silybin resulted in the strongest synergistic decrease in collagen content (Fig. 4g). Quantitative collagen volume fraction (CVF), and Ishak scoring system analysis following Masson staining supported the antifibrotic effects of the combination treatment (Fig. 4i, j). Correspondingly, the combination of silybin and carvedilol significantly suppressed the mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2 (Fig. 4k).

The combination of silybin and carvedilol synergistically ameliorates liver fibrosis

-

The abovementioned results show that the combination of silybin and carvedilol has an antifibrotic effect and reveal the optimal doses for fibrosis treatment. The antifibrotic effect of this combination at the optimal ratio was further validated (Fig. 5a). The results of serum biochemical analyses indicated that the efficacy of the combination therapy was superior to that of either drug alone (Fig. 5b), demonstrating that the synergistic effect of the combination in protecting the liver was stable. The hepatoprotective effect of the combination therapy was validated by pathological analysis. Combination therapy significantly alleviated pathological features, including hepatocellular necrosis and the inflammatory response, while monotherapy had only marginal effects (Fig. 5c, d). Pathological analysis by Masson and Sirius Red staining of liver sections intuitively revealed the synergistic effect of the combination treatment on collagen disposition (Fig. 5c). Additionally, CVF and Ishak scoring system analysis of the Masson staining results quantitatively supported the effects of these compounds in reducing the levels of ECM components and liver fibrosis (Fig. 5e, f). To specifically assess the effect of the combination regimen on fibrosis, the mRNA expression of various pro-fibrotic genes were further analyzed. The combination regimen markedly suppressed the hepatic mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2 (Fig. 5g). The synergistic effect of silybin and carvedilol was comprehensively evaluated by calculating CI values for various indicators, including serum levels of transaminases, the hepatic expression of pro-fibrotic genes, pathological injury scores and the hepatic collagen volume fraction. All the CI values were less than 0.7, which indicated a strong synergistic effect (Fig. 5h).

Figure 5.

Combined silybin and carvedilol significantly attenuates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. (a) Mouse experiment procedure scheme. (b) Serum ALT and AST levels (n = 6). (c) Representative images of H&E, Sirius Red, and Masson staining of liver sections (n = 6, scale bar, 100 μm). (d) Pathological injury scores on H&E staining of liver sections (n = 6). Liver fibrosis analysis by (e) CVF, and (f) Ishak scores on Masson staining of liver sections (n = 6). (g) The mRNA levels of fibrotic genes (n = 6). (h) CI values of above indicators. Results are present as Mean ± SEM, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs control, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the combination of 100 mg/kg silybin and 2 mg/kg carvedilol has a stable synergistic effect on alleviating liver fibrosis, providing a reference for the subsequent development of drug combinations for liver fibrosis.

A fixed-dose combination of silybin and carvedilol dose-dependently ameliorates liver fibrosis

-

Fixed-dose combinations, which contain two or more active components in a single dose form, increase the likelihood of treatment adherence[24]. To further evaluate the potential of the combination of silybin and carvedilol, the dose‒dependent effect of a fixed-dose drug combination on liver fibrosis was systematically explored (Fig. 6a). The drug combination dose-dependently reduced serum AST and ALT levels. Moreover, the combination at a high dose strongly decreased their levels to a greater extent than OCA, suggesting an excellent hepatoprotective effect of the combination (Fig. 6b). Its hepatoprotective effect against fibrosis was confirmed by histological analysis. H&E staining of liver sections revealed obvious alleviation of hepatocellular injury in response to the combination treatment (Fig. 6c, d). Masson and Sirius Red staining clearly revealed a dose-dependent reduction in the ECM area. Moreover, more marked reductions were observed for the medium- and high-dose combinations than for OCA (Fig. 6c, e & f). Similarly, the combination therapy dose-dependently reduced the hepatic mRNA levels of pro-fibrotic genes, including Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2. Notably, the inhibitory effects of all these doses were superior to those of OCA, suggesting an outstanding antifibrotic effect of the combination therapy (Fig. 6g). These results collectively indicate that the fixed-dose (50:1) combination of silybin and carvedilol alleviates liver fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

A fixed-dose combination of silybin and carvedilol attenuates liver fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner. (a) Mouse experiment procedure scheme. (b) Serum ALT and AST levels (n = 6). (c) Representative images of H&E, Sirius Red, and Masson staining of liver tissues (n = 6, scale bar, 100 μm). (d) Pathological injury scores on H&E staining of liver tissues (n = 6). Liver fibrosis analysis by (e) CVF, and (f) Ishak scores on Masson staining of liver sections (n = 6). (g) The mRNA levels of fibrotic genes (n = 6). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, *** p < 0.001 vs control, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

The combination of silybin and carvedilol ameliorates fibrosis by regulating Wnt signaling

-

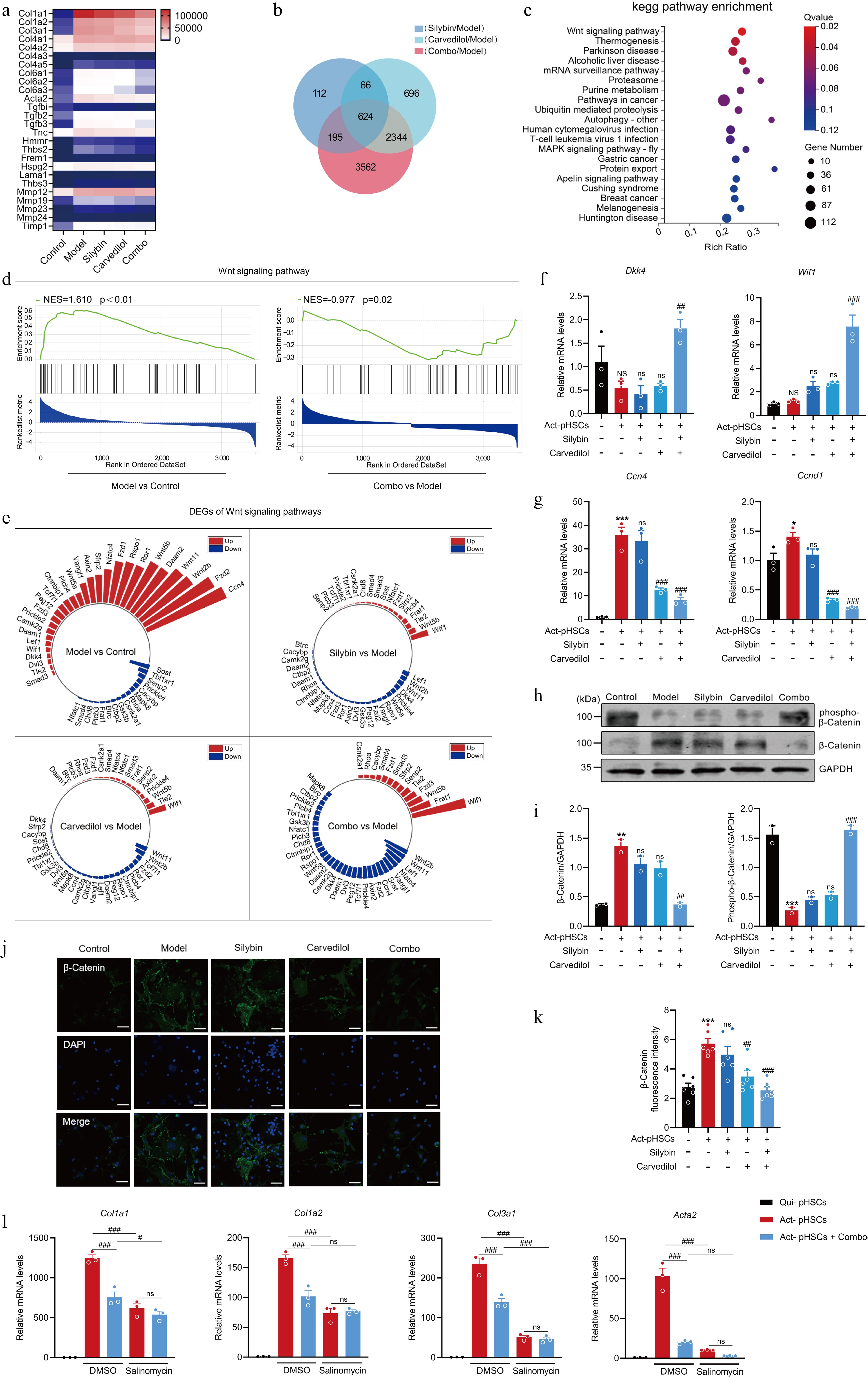

The underlying mechanism through which the combination of silybin and carvedilol suppresses HSC activation and alleviates liver fibrosis was subsequently explored via transcriptomic studies. To visualize the expression dynamics of signature fibrogenetic genes, a heatmap analysis was performed on a panel of markers of HSC activation and ECM deposition, such as Col1a1, Col1a2, and Acta2. As depicted in Fig. 7a, the model group (activated HSCs) exhibited a marked upregulation of these pro-fibrogenic genes, compared to the control group (quiescent HSCs). Treatment with either silybin, carvedilol, or their combination (combo) effectively reversed this activation signature, with the combination therapy showing the most potent inhibitory effects. In the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, compared to the control group, the ECM-receptor interaction, Wnt signaling pathways, and TGF-β signaling etc., were enriched in the model group. Furthermore, both Wnt and ECM-receptorinteraction pathway were enriched in combo group when compared to the model group (Supplementary Fig. S2). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) specifically in the combination therapy-treated group (excluding those associated with individual treatment with either silybin or carvedilol) were significantly enriched in pathways involved in HSC activation (Fig. 7b). Among these pathways, the Wnt pathway exhibited the highest enrichment score, encompassing 44 DEGs (Fig. 7c). Similarly, GSEA, by the hallmark Wnt signaling gene set, revealed a significant up-regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway in activated HSCs (NES = 1.610, p < 0.01). Conversely, the GSEA plot for the comparison between the combo groups and the model group demonstrated a significant down-regulation of the same pathway (NES = −0.977, p = 0.02, Fig. 7d). Notably, 44 Wnt signaling-related DEGs above changes by comparative analysis between the model group and the control group, together with each treatment group and the model group, revealed that the combination of silybin and carvedilol synergistically suppressed the Wnt signaling pathway (Fig. 7e). In addition, the mRNA expression of the Wnt inhibitory factors Wnt inhibitory factor-1 (Wif1) and Dickkopf-1 (Dkk1), were significantly upregulated by the combination treatment (Fig. 7f). Specifically, the mRNA expression of genes downstream of the Wnt signaling pathway, such as Ccn4 and Ccnd1, was significantly downregulated by the combination treatment (Fig. 7g). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling is reported to be activated during fibrosis development, and HSC activation, while inhibition of this pathway is proven to reverse HSC activation[25]. In the canonical Wnt pathway, β-catenin is the essential molecule that mediates Wnt signaling. The protein expression of β-catenin was increased in activated HSCs but was suppressed by the combination treatment. A significant downregulation of phosphorylated β-catenin was detected in activated HSCs, indicating activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway during HSC activation. Critically, treatment with the combination restored the level of phosphorylated β-catenin in activated HSCs. (Fig. 7h–k). These results demonstrate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is closely associated with HSC activation and is suppressed by the combination of silybin and carvedilol. The contribution of Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulation to the inhibition of HSC activation by the combination therapy was then investigated. Salinomycin is a potent inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The effect of the combination treatment on HSC activation was evaluated in the presence or absence of salinomycin. As expected, in the absence of salinomycin, the combination treatment significantly decreased the mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2. However, in the presence of salinomycin, the combination failed to alter the mRNA levels of the abovementioned pro-fibrotic genes (Fig. 7l), suggesting that the combination inhibited HSC activation by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Taken together, these findings suggest that silybin and carvedilol cooperatively suppress Wnt/β-catenin signaling to inhibit HSC activation.

Figure 7.

Silybin and carvedilol synergistically inhibits HSC activation by regulating the Wnt signaling pathway. (a) Heatmap of the expression of signature HSC activation-related genes across different treatment groups. (b) Venn diagram of DEGs in response to mono- and combination therapies. (c) KEGG pathway enrichment of combo-specific DEGs. (d) GSEA of Wnt signaling pathway. (e) Radial plot of Wnt signaling-related DEGs across inter-group comparisons. (f) The mRNA levels of Wif1 and Dkk1 in pHSCs (n = 3). (g) The mRNA levels of target genes in Wnt signaling in pHSCs (n = 3). (h)–(k) Western blot analysis (h, i, n = 2), immunofluorescence (j, k, n = 6) analysis and the quantification analysis of β-Catenin in pHSCs. (l) The mRNA expression of pro-fibrotic genes in pHSCs by the combination in the presence or absence of salinomycin (n = 3). Results are present as Mean ± SEM, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, and NS, no significance, vs control, #p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA.

Silybin and carvedilol synergistically inhibit the expression of Wnt4 to suppress HSC activation

-

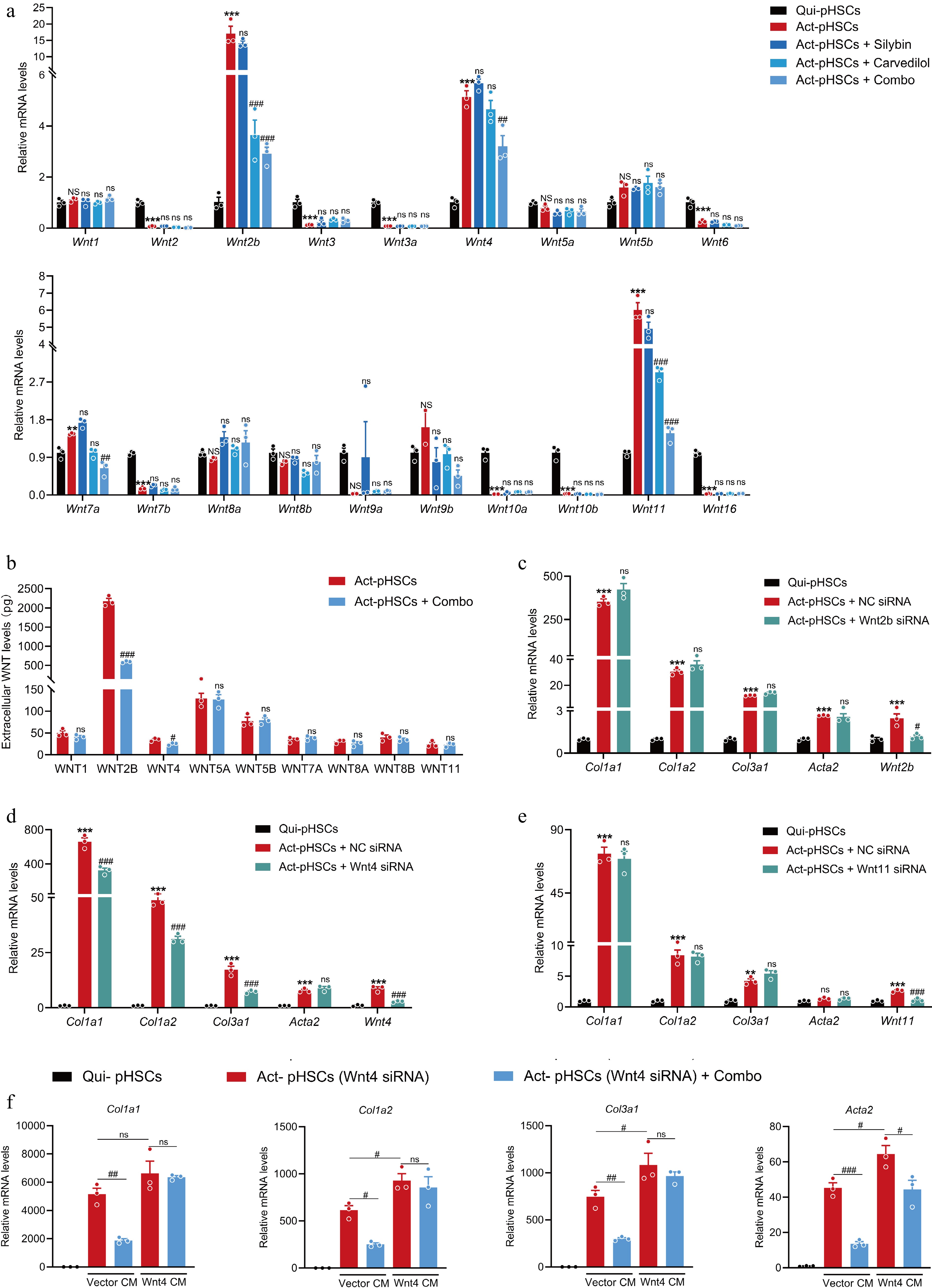

Wnt ligands, which initiate the Wnt signaling pathway, are identified as critical drivers of HSC activation. The effect of individual or combined silybin and carvedilol on all members of the Wnt ligand family was then evaluated. Transcriptional analysis revealed that silybin and carvedilol synergistically decreased the mRNA levels of Wnt2b, Wnt4, and Wnt11 in activated pHSCs (Fig. 8a). Additionally, analysis of extracellular Wnt proteins revealed that this combination significantly decreased the WNT2B and WNT4 levels, confirming that the combination robustly curtails the expression of these Wnt ligands (Fig. 8b). Potential roles of WNT2B, WNT4, and WNT11 on driving HSC activation were then evaluated via a loss-of-function approach. Knockdown of Wnt4 in activated pHSCs significantly inhibited the mRNA expressions of pro-fibrogenic genes, including Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Acta2, hinting that Wnt4 is a driver of HSC activation (Fig. 8c–e). Meanwhile, carvedilol alone did not exhibit a significant effect on Wnt4 protein expressions (Supplementary Fig. S3). It was then supposed that Wnt4 might mediated the effect of combined silybin and carvedilol. HEK293T cells were transfected with vector or Wnt4 overexpression plasmid, and the conditioned medium (CM) was collected and subjected to pHSCs with Wnt4 knocked down. In HSCs incubated with Wnt4 CM, treatment with the combination failed to suppress the expressions of Col1a1, Col1a2, and Col3a1. These results indicated that the combination suppressed the expression of various collagens in a Wnt4-dependent manner. In addition, the combination also inhibited the mRNA expression of Acta2 in HSCs incubated with Wnt4 CM, although in a weaker degree than that in HSCs incubated with Vector CM. This result hints that the combination inhibits Acta2 expression in a manner that partially depends on Wnt4 (Fig. 8f).

Figure 8.

The combination of silybin and carvedilol inhibits HSC activation by suppressing WNT4. (a) The mRNA expression of 19 Wnt ligands in pHSCs treated with individual or combined silybin and carvedilol (n = 3). (b) Extracellular protein levels of main Wnt ligands in pHSCs (n = 3). mRNA expression of pro-fibrotic genes in pHSCs treated with either (c) Wnt2b siRNA, (d) Wnt4 siRNA or (e) Wnt11 siRNA (n = 3). (f) The mRNA expression of pro-fibrotic genes in pHSCs (Wnt4 knocked down) incubated with conditioned medium collected from HEK293T cells transfected with Vector plasmid (Vector CM) or Wnt4-overexpressing plasmid (Wnt4 CM) (n = 3). Results are presented as Mean ± SEM, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs control, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01,### p < 0.001, and ns, no significance, vs model, as assessed with ANOVA or t-test.

-

Liver fibrosis results from diverse causes, such as alcohol abuse, viral infections, and steatotic liver disease. The multifactorial pathogenesis presents a formidable challenge to the development of antifibrotic drugs. To date, there is still no approved therapy for this disease[3]. Since drug combinations can provide profound advantages over monotherapies, they are promising strategies for treating chronic and multifactorial diseases[7]. In this study, a combination of silybin and carvedilol was developed for the therapy of liver fibrosis. A fixed-dose combination (50:1 for silybin and carvedilol in vivo) synergistically inhibited HSC activation and fibrosis development by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Thus, this study provides a promising drug candidate for liver fibrosis therapy.

There are approximately 850 million patients with liver fibrosis worldwide in 2024, and the number is still on the rise. Moreover, if not fully resolved, liver fibrosis might further progress to liver cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Many attempts have been made to reduce the burden of liver fibrosis. However, there is still a lack of safe and effective chemical or biological agents. Given the large patient population, and the crucial point of reversibility, the development of liver fibrosis drugs is both urgent and necessary[26].

The pathophysiology of liver fibrosis is complex. It is a dynamic process in which the liver repeatedly suffers damage, and the repair process becomes uncontrolled, resulting in abnormal deposition of excessive ECM and the formation of scar tissue. HSCs are the core cells that execute and drive this process. Various chronic liver injuries directly or indirectly activate HSCs, causing a transformation from a quiescent phenotype to an activated one. Activated HSCs are the main source of pathological ECM, especially the abnormal, excessive deposition of collagen I and III fibers. Moreover, the activation of HSCs results in positive feedback through autocrine and paracrine signaling circuits, continuously amplifying inflammatory and fibrotic signals[4]. Therefore, drugs targeting HSCs to treat liver fibrosis are constantly being developed, but these drugs often fail to achieve a balance of HSC activation inhibition and liver protection, thus causing side effects due to their intrinsic mechanisms. For example, pirfenidone, a TGF-β signaling inhibitor, might cause significant increases in ALT and AST levels[27]. Therefore, although the involvement of various signaling pathways, including the TGF-β/Smad, PDGF, PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, Notch, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, in liver fibrosis has been confirmed, the development of safe and effective drugs for treating liver fibrosis remains challenging[6].

Since multiple pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to liver fibrosis, the use of a single target or single drug is unlikely to be sufficient to alleviate its pathology. Thus, it is not difficult to understand why monotherapies show limited efficacy in preserving liver function. As the success of monotherapies appears to be limited, combination therapies seem to be a logical approach to successful treatment. Mechanistically, they provide advantages such as enhanced efficacy, the ability to overcome resistance, improved pharmacokinetics, or reduced adverse effects[7]. The advantages of combination therapies are expected to be more conspicuous for multifactorial and chronic diseases. Additionally, fixed-dose combinations, which contain two or more functional components in a single dose form, could further increase the likelihood of treatment adherence[24]. Indeed, drug combinations for various liver diseases have recently attracted increasing attention. The combination of tropifexor and cenicriviroc, the combination of selonsertib, GS-0976, and GS-9764, and several others have been assessed in clinical trials[28,29]. With respect to liver fibrosis, we have proposed a combination strategy based on the limitations of the biological functions of specific targets, such as the combination of an FXR agonist and an apoptosis inhibitor[30,31]. It is well accepted that synergy between drugs is rare and highly context dependent. Rational drug combinations of pairs with synergistic effects could be developed via either target-based drug design and combination or phenotype-based combination screening. The former approach requires synergistic targets, which requires time-consuming validation. However, the latter is a reproducible and unbiased approach for the discovery of drug combinations.

Natural products are reliable and productive sources of drug discovery. Their use in traditional medicine provides insights into their efficacy and safety. Owing to these advantages, most approved drugs are inspired by natural products. Despite these successes, their uses in drug development have decreased because of several challenges. One challenge is the identification of the bioactive compounds among abundant components, and another challenge is their relatively weak activities[32−34]. According to the typical theory of compatibility in traditional Chinese medicine, a typical self-contained prescription is composed of medicines that play the roles of monarch, minister, assistant, and envoy. This theory suggests that powerful pharmacological efficacy might be achieved for natural products when they are paired with others[35]. Silybin is a natural active compound that has definite protective effects against fatty liver disease, chronic viral hepatitis, drug/toxic liver injury, etc.[11]. However, its ability to inhibit HSC activation and fibrosis development remains substantially limited.

Hence, a combination regimen leveraging the hepatoprotective benefits of silybin and synergistically enhanced direct antifibrotic effects through combination with other drugs was employed in this study. FDA-approved drugs were selected for screening because their established safety profiles enable drug repurposing, thus bypassing early-stage development and accelerating research while reducing both costs and failure risks. Finally, through screening 397 FDA-approved drugs, we found that the combination of silybin with carvedilol is an effective combination for fibrosis. Carvedilol is commonly used in clinical settings for the treatment of hypertension, angina pectoris, and chronic heart failure[36]. In the field of liver diseases, it has become a first-line treatment for portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis[37]. Carvedilol alone has a marginal effect on HSC activation and proliferation and, ultimately, fibrosis development. Surprisingly, it significantly inhibited HSC activation and fibrosis development when it was combined with silybin. This combination demonstrated pronounced synergistic efficacy against HSC activation and fibrosis development compared with individual monotherapies. The strength of the synergistic effect also depends on the dose ratio of the two drugs. The optimal dose ratio of silybin to carvedilol was also evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the optimal ratio with the strongest synergistic effect was determined. This combination showed excellent efficacy in alleviating HSC activation and liver fibrosis and was superior to OCA.

The quest for effective antifibrotic therapies has increasingly shifted towards combinatorial strategies and drug repurposing to overcome the limitations of single-target agents, such as those observed with silybin monotherapy above. Recent investigations have explored combinations such as pirfenidone with andrographolide to enhance anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic benefits for liver fibrosis of biliary atresia[38], or sodium alginate combined with oxymatrine ameliorates CCl4-induced chemical hepatic fibrosis in mice[39]. Meanwhile, the repurposing of statins is linked to reduced odds of liver fibrosis among individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes[40]. The present study contributes to this evolving landscape by introducing a novel combination of silybin and carvedilol. This strategy is distinct in its synergistic targeting of liver injury and multi-pathway dysregulation in HSC activation. Unlike other antifibrotic drug combinations, both silybin and carvedilol are clinically available drugs. Their safety has been validated in many patients. In addition, no obvious drug‒drug interactions were detected between them (data not shown). These properties suggest that this combination could be rapidly entered into clinical trials. Notably, in contrast to repurposed drugs with single primary mechanisms, silybin offers multiple advantages of natural active ingredients for lipid metabolism management and potent hepatoprotective activity, which was found to synergize powerfully with carvedilol for attenuating liver fibrosis. This level of mechanistic insight, combined with the favorable safety profiles of both constituents, positions the silybin–carvedilol combination as a uniquely promising and translatable therapeutic approach for hepatic fibrosis.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a classical pathway involved in liver physiology and pathology. Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled receptors on the cell membrane and LRP coreceptors, inhibiting the degradation of β-catenin and causing it to accumulate in the cytoplasm and enter the nucleus. It then binds to TCF/LEF transcription factors, initiating the transcription of various target genes. This signaling is closely associated with, and activated in, liver fibrosis. β-Catenin mediates the transcription of various pro-fibrotic genes, thus directly promoting the activation and proliferation of pHSCs[41−43]. The combination of silybin and carvedilol can significantly reduce the expression of β-catenin in activated pHSCs and simultaneously increase the transcription of the Wnt inhibitors Wif-1 and Dkk4. These findings reveal that the combination can comprehensively inhibit Wnt signaling. Moreover, the combination inhibits HSC activation and fibrosis development by modulating the Wnt signaling pathway, as confirmed by the loss of antifibrotic effects in the presence of salinomycin.

Wnt signaling is triggered by the association between Wnt ligands and their receptors in the membrane. Nineteen Wnt ligands have been identified in humans. They activate different signal pathways and are endowed with variant functions. Wnt3a and Wnt5a were demonstrated to serve as triggers to HSC activation and liver fibrosis[42,44]. Additionally, Wnt4 was significantly upregulated during the activation of HSCs, which was supposed to contribute to HSC activation[45]. In this study, solid evidence that Wnt4 was a trigger of HSC activation is provided. Moreover, silybin and carvedilol synergistically inhibit the expression of Col1a1, Col1a2, and Col1a3 via cooperatively suppressing Wnt4 expression and downstream β-catenin signaling. They also partially inhibit the expression of Acta2 via suppressing Wnt4/β-catenin signaling, however other molecular mechanisms need further exploration. Additionally, the direct binding targets and synergistic mechanism in suppressing Wnt4/β-catenin signaling and HSC activation remain unclear and need further study[46,47].

-

In summary, owing to the complexity of the pathological mechanisms of liver fibrosis, and the limitations in the pharmacological efficacy of monotherapies, a combination regimen was proposed here. A fixed-dose combination of silybin and carvedilol was developed to treat liver fibrosis. They significantly and synergistically inhibit HSC activation and fibrosis development by suppressing Wnt4/β-catenin signaling, although they marginally directly inhibit fibrosis when used alone. Since both silybin and carvedilol are approved for use, this study provides a clinically available regimen for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

-

All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines provided by the Animal Care Committee. All the animal experiments performed in the study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (LACUC Issue No: 2022-06-026, approval date: 2022.06.26).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang H, Hao H, Wang G; data collection: Chen A, Zhu X, Jiang H, Gong M, Cui S; analysis and interpretation of results: Chen A, Jiang H; draft manuscript preparation: Chen A, Zhu X; manuscript revision and editing: Wang H, Hao H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (2022YFA1303800 and 2021YFA1301300); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373946, 82073926, 82321005, 82530122, and 81930109); Major Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (BG2024045); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20253058); Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation (G20582017001); the Project of State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University (SKLNMZZ202402); and the Project Program of Basic Science Research Center Base (Pharmaceutical Science) of Yantai University (P202404).

-

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

-

#Authors contributed equally: An Chen, Xiaochai Zhu, Houzhe Jiang

- Supplementary Table S1 Primers sequences.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Cell viability of hepatocytes and HSCs treated with silybin and/or carvedilol.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Effect of carvedilol treatment on WNT4 protein levels in pHSCs.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Pharmaceutical University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen A, Zhu X, Jiang H, Gong M, Cui S, et al. 2025. Combination of silybin and carvedilol synergistically alleviates liver fibrosis by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Targetome 1(1): e009 doi: 10.48130/targetome-0025-0009

Combination of silybin and carvedilol synergistically alleviates liver fibrosis by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling

- Received: 24 October 2025

- Revised: 14 November 2025

- Accepted: 17 November 2025

- Published online: 15 December 2025

Abstract: Liver fibrosis is a chronic and multifactorial liver disease that usually involves long-term hepatic injury, and is triggered mainly by hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) activation. Due to the complexity of liver fibrosis pathophysiology, the efficacy of monotherapies is limited. To overcome this limitation, the development of combination regimens has emerged as a potentially powerful strategy for treating liver fibrosis. In this study, a combination regimen involving silybin, a natural compound widely used for various liver diseases, with powerful antifibrotic efficacy was identified. The effects of 397 FDA-approved drugs in combination with silybin were evaluated using the COL1A1 luciferase reporter. Among the pairs of drugs, silybin and carvedilol had the strongest synergistic inhibitory effect on HSC activation. This synergistic effect was further validated in primary hepatic stellate cells (pHSCs) in vitro, and in CCl4-treated mice in vivo. The ratio with the strongest synergistic and inhibitory effects was systemically evaluated to identify the optimal fixed-dose combination (50:1 for silybin and carvedilol in vivo). This combination regimen significantly inhibited CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner. Mechanistically, combined silybin and carvedilol inhibited HSCs activation through synergistically suppressing Wnt4/β-catenin signaling. This study provides a clinically feasible combination regimen with powerful synergistic and inhibitory effects on liver fibrosis.

-

Key words:

- Silybin /

- Carvedilol /

- Fixed-dose combination /

- Hepatic stellate cell /

- Liver fibrosis /

- Wnt signaling pathway