-

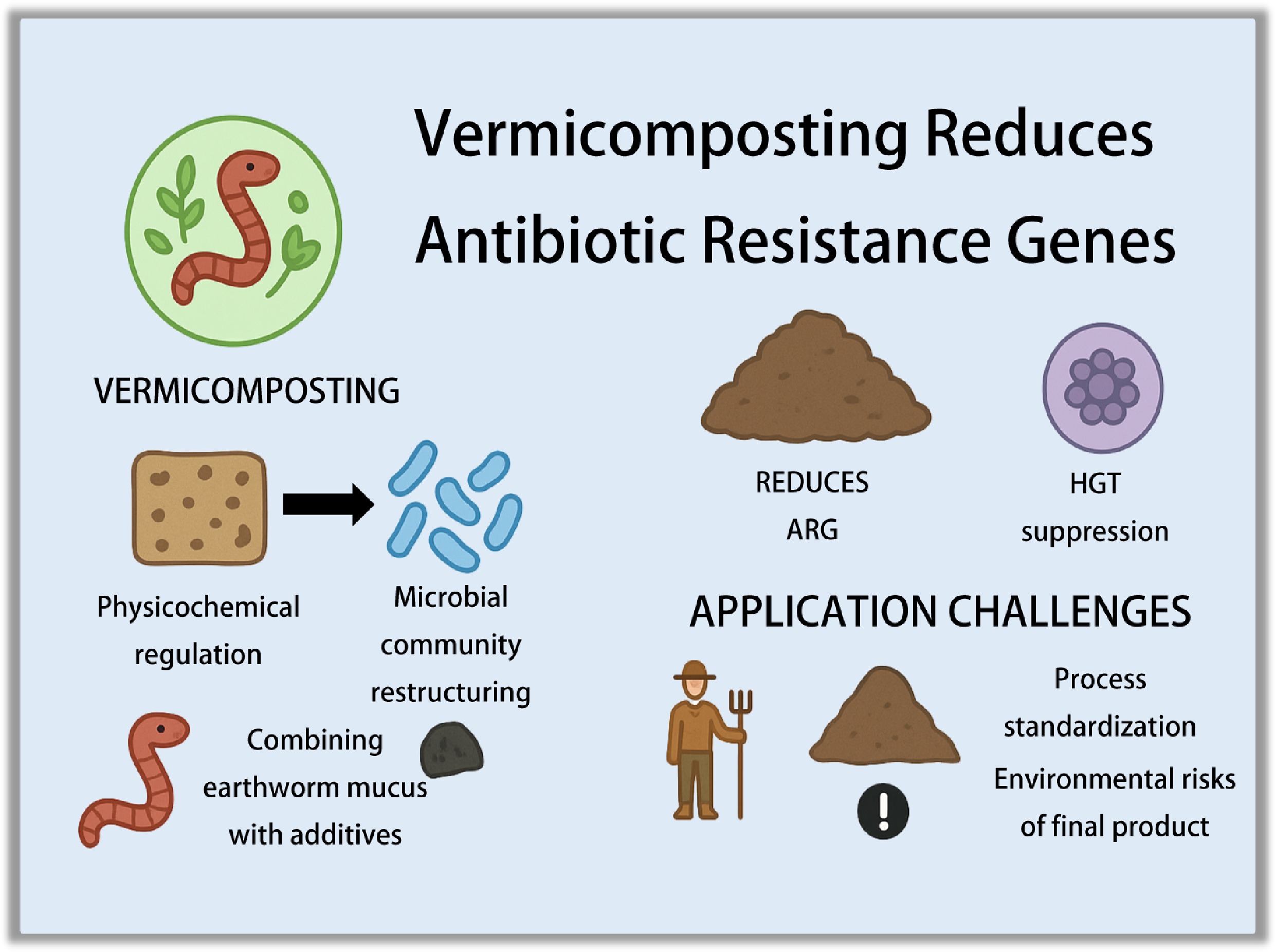

The World Health Organization (WHO) has repeatedly emphasized that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) ranks among the most serious threats to global public health and food safety[1]. Its increasing distribution poses systemic risks to human healthcare, animal welfare, and environmental sustainability[2]. Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent the genetic foundation for the transmission of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). These genes can be acquired through two primary pathways: vertical gene transfer (VGT), which is the inheritance from parent to offspring, and horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which involves the dissemination of genetic material between cells, facilitating the spread of ARGs across diverse bacterial populations[3]. This makes their environmental occurrence and evolution a significant focus of research. In the livestock and poultry industry, the use of antibiotics has led to the enrichment and persistence of various ARGs in animal manure, and the self-propagating nature of these genes presents an ongoing challenge. The use of manure on farmland without sufficient treatment constitutes a critical pathway for the transmission and dissemination of ARGs into soil, water environments, and the food chain[4]. This transmission route is illustrated in Fig. 1, which outlines how ARGs originating from livestock can persist in agricultural ecosystems and ultimately enter human bodies, highlighting the direct ecological and health risks. Consequently, the development of efficient, stable, and harmless treatment technologies to achieve significant ARG removal while simultaneously promoting the utilization of agricultural waste has become a key and urgent challenge in environmental and health sciences.

Figure 1.

Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARG) from livestock to humans through agricultural ecosystems. This figure illustrates how the use of antibiotics in livestock leads to the emergence and enrichment of ARGs in animal manure. The subsequent application of this manure as fertilizer facilitates the dissemination and persistence of ARGs in agricultural soils and crops. Ultimately, these ARGs can be transferred to human gut bacteria, completing the transmission chain and underscoring the associated ecological and public health risks.

Conventional composting can reduce ARG abundance. However, the removal efficiency is highly variable and influenced by factors such as feedstock composition, temperature, and microbial community dynamics, making stable and significant ARG reduction challenging[5]. This variability complicates achieving stable, significant reductions in ARG levels. More alarmingly, the composting process itself can promote the HGT of ARGs, such as tetG and sul1, due to microbial stress responses and the elevated activity of MGEs. This is critically evidenced by the rebound of intI1, which can surge by 31.4-fold during maturation, thereby exacerbating dissemination risks and potentially leading to ARG resurgence after composting[6]. In contrast, vermicomposting is a green bioaugmentation technology that relies on a powerful synergy between earthworms (e.g., Eisenia fetida, Eudrilus eugeniae) and microbial communities. Vermicomposting is a mesophilic, bio-oxidative process that leverages the synergistic action of earthworms and their associated microbial communities to stabilize and humify organic materials[7]. This process not only transforms livestock manure into high-value vermicast but also achieves multi-pathway, synergistic control of ARGs. This efficient and stable performance is underpinned by strict control of key parameters, including a C/N ratio of 25–30:1, a moisture content of 60%–80%, and a pH of 6.5–8.0[8]. Gómez-Brandón et al. reported that vermicomposting reduced aminoglycoside, MLSB, and tetracycline ARGs by about 3-, 10-, and 5-fold, while heavy metal resistance, MGE, and insertion-sequence genes dropped 9-, 24-, and 97-fold, respectively, relative to untreated raw materials[9]. Furthermore, vermicomposting enhances the humification of organic matter. The final product significantly improves soil structure, increases water and nutrient retention capacity, and provides sustained, adequate nutritional support for plants[10,11].

Recent research has highlighted the potential of vermicomposting to reduce ARGs. Results consistently demonstrate that this technology efficiently and stably reduces pathogenic bacteria and various typical ARGs in manure[10,12,13]. Even under exogenous tetracycline stress, vermicomposting significantly enhanced the removal of key antibiotic resistance genes, reducing the abundance of tet-ARGs to levels as low as 1.56 × 10−3 copies/16S rRNA, which is nearly an order of magnitude lower than in the non-stressed control group (1.57 × 10−2 copies/16S rRNA)[12]. To systematically evaluate the effects of various strategies, Table 1 summarizes and compares the advantages and disadvantages of different livestock manure composting technologies in degrading ARGs. A systematic understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms by which vermicomposting controls ARGs is essential for optimizing process parameters and promoting its standardized application in practice. Based on this premise, this review synthesizes recent advances in ARG pollution control via vermicomposting, focusing on its synergistic, multi-pathway removal mechanisms. It further explores the potential applications and current challenges of this technology in practical settings, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation and technical reference for ARG mitigation in agricultural waste recycling.

Table 1. The effects (advantages and disadvantages) of livestock manure composting technology on the ARGs degradation through various strategies

Strategies Effects Merits Limitations Removal rate Ref. Traditional compost Degrading effect on some ARGs Mature process, simple operation, low cost Efficiency depends on temperature and aeration; potential for HGT during cooling 50%–90% [14−16] Vermicomposting Significant removal of various ARGs, primarily via gut digestion by earthworms Mild process, high-quality product; effective gut-mediated suppression Slower process; limited effect on some persistent ARGs 70%–95% [17,18] Microbial agents compost Enhanced removal of specific ARGs via competitive inhibition by functional strains Targeted approach; can accelerate composting and improve maturity Efficacy depends on inoculant survival; potential risk from exogenous microbes 80%–95% [19−21] High-temperature pretreatment compost Drastically reduces initial ARG load

by eliminating host bacteriaHighly effective at initial pathogen and ARG inactivation High energy consumption does not prevent subsequent HGT during composting > 90% [22,23] -

Antibiotic resistance genes are widespread contaminants in livestock and poultry manure. Their environmental risk arises from the persistence of the genes, and their mobility. ARGs can be located on bacterial chromosomes or on MGEs such as plasmids, transposons, and integrons[24]. They exist in the environment as intracellular DNA (iDNA) and extracellular DNA (eDNA)[25]. These two forms facilitate the dissemination of ARGs among microbial communities via HGT.

Vermicomposting is highly effective at removing various types of ARGs, which is attributed to its synergistic, multi-pathway mechanisms[26]. As shown in Table 2, vermicomposting generally achieves higher removal rates for key ARGs and MGEs than conventional composting methods. For example, Li et al. found that after vermicomposting of cattle manure, the total abundance of ARGs and MGEs decreased by 53% and 52%, respectively, indicating that the process effectively suppresses the potential for gene transfer[12]. In another study, Guo et al. demonstrated the strong removal capacity of vermicomposting. Their research showed a 74.5% reduction in total ARG abundance, along with a 92% reduction in ARG-host bacteria and a 94% inhibition of resistant plasmid conjugation[10]. It is important to note that this removal effect is not solely due to the direct processing of waste by earthworms. Their excretions, such as vermicast, continue to reduce ARGs and pathogens. For instance, vermicast can reduce ARGs by over 60%, and potential pathogenic bacteria by 36% in cattle manure[17], demonstrating the sustained bioremediation potential of vermicomposting products.

Table 2. Removal of key ARGs and MGEs: vermicomposting versus conventional composting

Genes Vermicomposting removal Conventional composting removal Ref. Total ARGs 53% reduction 34%–41.7% reduction [27−29] tet-, sul-, erm- genes tet-genes 82% reduction tet-genes 73.4% reduction [16,29,30] sul-genes 4% reduction sul-genes 45.1% reduction erm-genes 78% reduction erm-genes 56% reduction MGEs 68% reduction 25% reduction [12,31] The removal of ARGs during vermicomposting is a complex, dynamic process. In the initial stages, the abundance of some ARGs may temporarily increase or fluctuate, as observed in traditional composting, where total ARG abundance can peak at 1,739.2 ppm on day[18]. This is often due to the alleviation of antibiotic selective pressure and intense microbial succession. However, as the process progresses, driven continuously by biological activities such as intestinal digestion, microbial regulation, and earthworm enzyme secretion, the substrate progressively matures. The abundance of ARGs generally shows a consistent decline, ultimately falling significantly below initial levels[32,33]. For example, vermicomposting achieves a 73.3% mean removal efficiency of total ARGs from raw manure, with the most effective farms achieving reductions of up to 97.89%[19]. This trend reflects an ecological succession from disturbance to stability within the system. Environmental factors, particularly temperature, play a crucial role in regulating composting efficiency and ARG removal. Studies indicate that 20°C is the optimal temperature for vermicomposting, as it results in the highest first-order kinetic coefficients for the removal of key ARGs such as qnrA (k = 0.0190 d−1), qnrS (k = 0.0330 d−1), and tetM (k = 0.0269 d−1), thereby achieving superior ARG removal efficiency while ensuring the final product possesses good biological stability[34]. Furthermore, the use of exogenous additives has shown synergistic effects. For instance, Yu et al. found that adding biochar increased earthworm biomass by improving the substrate's physicochemical properties, such as porosity, water retention, and nutrient availability, while simultaneously mitigating heavy metal stress through mechanisms like cadmium stabilization. This combined approach enhanced the degradation of organic matter in sludge and promoted the conversion of cadmium from an active state to a more stable form, thereby indirectly creating favorable conditions for ARG reduction[35].

Compared with traditional composting, which may only reduce total ARG abundance by 71.3% and faces challenges such as the 31.4-fold rebound of the intI1 gene during maturation, vermicomposting more effectively suppresses this initial rebound of specific ARGs, maintaining a consistent downward trend throughout the process[18]. This advantage can be attributed to the restructuring of the microbial community, the suppression of MGE activity, and improved regulation of environmental conditions induced by earthworms. Therefore, vermicomposting represents a promising biotechnological approach for controlling the environmental spread of ARGs.

-

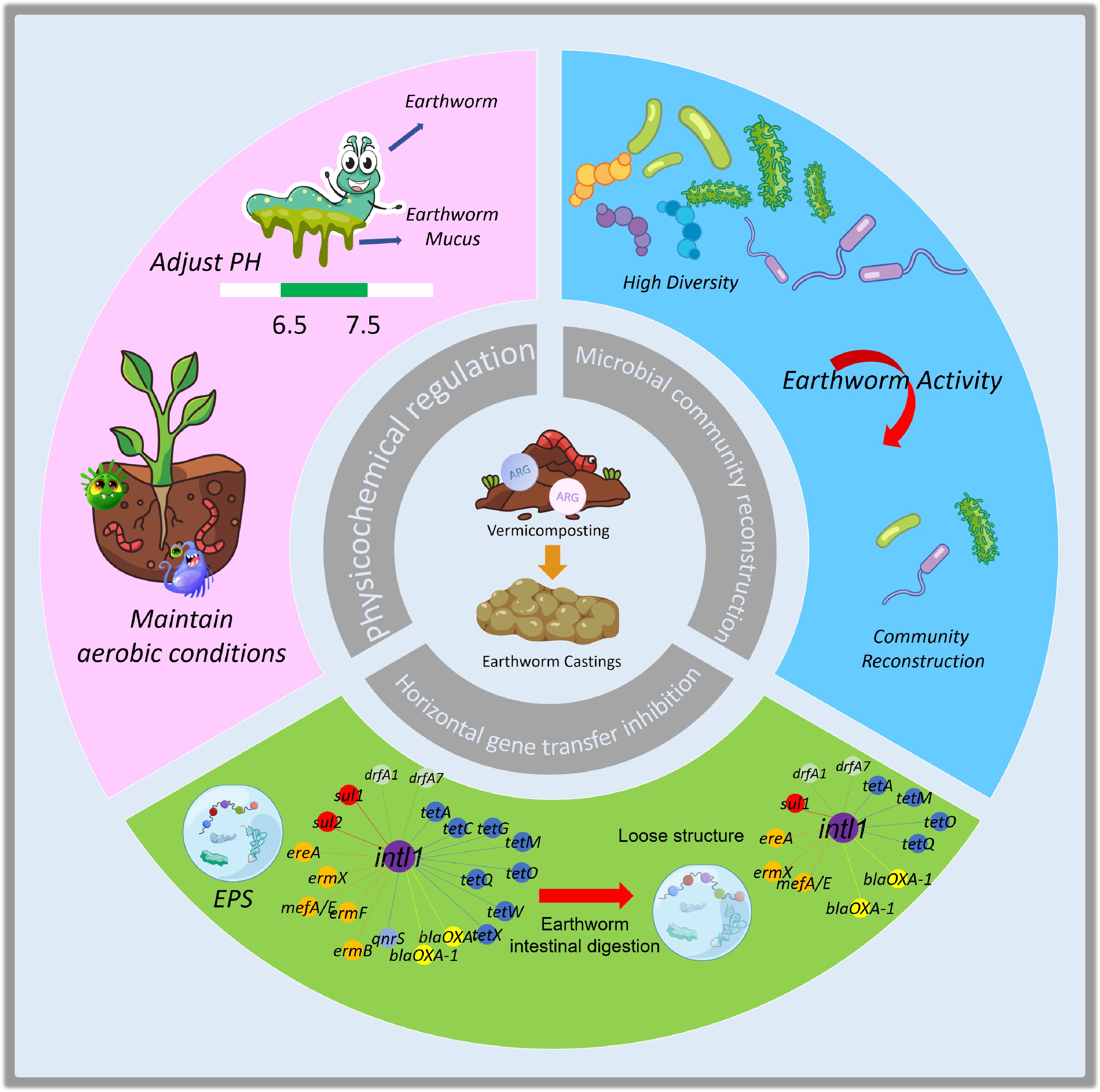

Earthworms reduce ARGs through a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Their life activities collectively reshape the substrate's microenvironment, microbial community, and gene transfer potential, forming an integrated system that effectively suppresses and removes ARGs. The interactions within this system are illustrated in Fig. 2, which delineates the specific mechanisms by which vermicomposting regulates the soil environment and inhibits horizontal gene transfer.

Figure 2.

Interconnected mechanisms of vermicomposting in suppressing ARGs. This schematic demonstrates the role of earthworms in mitigating risks posed by antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) through a series of physicochemical mechanisms that improve substrate conditions and disrupt the habitats of ARG hosts. Concurrently, earthworms drive the restructuring of microbial communities, transitioning the system from a state of high diversity to a stable, reconstructed condition that limits the availability of potential hosts for ARGs. Furthermore, they play a significant role in inhibiting horizontal gene transfer by suppressing mobile genetic elements and degrading extracellular DNA, thus obstructing critical pathways for ARG dissemination. Collectively, these integrated mechanisms establish a multi-tiered barrier against the propagation of ARGs.

Physical and chemical regulation: creating a microenvironment hostile to ARGs

-

Earthworms create an unfavorable microenvironment for ARGs by altering the substrate's physical structure and chemical properties. Through burrowing and feeding, they increase substrate porosity and improve aeration. This activity maintains a continuous aerobic state with higher oxygen partial pressure (pO2) than in traditional composting[36,37]. This aerobic condition suppresses the activity of many anaerobic bacteria that are potential ARG hosts, while promoting the growth and metabolism of aerobic microorganisms. This shift accelerates the degradation of residual antibiotics, thereby removing the primary selective pressure for ARG enrichment[38−40]. The earthworm gut acts as a key bioreactor, where physical grinding and enzymatic digestion directly disrupt host bacteria, while the unique gut microbiota and subsequent maturation in vermicast create a long-term inhibitory environment[41]. This environment continually suppresses pathogens and mobile genetic elements, and recent evidence suggests it may even regulate phage-mediated transduction by influencing phage-host interactions, thereby providing a robust barrier against the horizontal transfer of ARGs[42]. This mechanism is consistent with the growth of ARG-carrying pathogens, which form a biochemical barrier[43,44]. This multifaceted chemical regulation, working in concert with physical improvements, establishes the microecological foundation for ARG suppression.

Microbial community restructuring: targeting the host basis of ARGs

-

The profound restructuring of the microbial community by earthworms is a core biological mechanism for reducing ARGs[45,46]. This process directly targets the host bacteria of ARGs. First, the earthworm gut acts as an efficient "bioreactor". During digestion, it effectively suppresses or eliminates pathogenic bacteria[47], which are often key hosts for various ARGs. Direct reduction in host bacteria results in a decrease in the absolute abundance of iARGs. Second, earthworm activity strongly drives the succession and structural optimization of the broader microbial community in the substrate[48,49]. Multiple studies have shown that earthworm processing significantly alters the alpha diversity (including richness and evenness) and beta diversity of bacterial communities[50−52]. For instance, Uribe-Lorío et al. found that vermicomposting significantly altered the bacterial community of dairy cattle excreta, increased its diversity, and shifted the dominant populations toward strains with decomposition and nitrogen-fixing functions[48]. A key feature of this succession is the shift in the microbial community. The dominance of fast-growing r-strategists over slow-growing K-strategists[53]. Since many ARG host bacteria (e.g., Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Escherichia, and related genera) belong to r-strategists, this community shift directly reduces the proportion of resistant bacteria within the ecosystem.

Finally, the earthworm gut and its mucus promote the growth of specific functional microbial groups that can degrade pollutants[54]. These microbes efficiently break down organic pollutants, including antibiotics. For example, Lin et al. found that the degradation of tetracycline was significantly accelerated in systems with both E. fetida and Amynthas robustus (A. robustus) earthworms[55]. Through their competitive advantage, these functional microbial groups reduce the ecological niche available to ARG-carrying populations, thereby reinforcing the removal effect at the level of resource competition[56].

Suppression of HGT: a key pathway to blocking ARG dissemination

-

Even when the abundance of host bacteria is reduced, the dissemination of ARGs among residual populations via HGT remains a significant environmental risk[10,57,58]. Vermicomposting mitigates this risk through a key mechanism: inhibiting MGEs. This intervention undermines the vehicles and machinery essential for HGT (e.g., plasmid conjugation), leading to a marked reduction in conjugation frequency and overall ARG dissemination[42,50,59−61].

Conjugation requires close physical contact between donor and recipient cells. The intense microbial competition and limited nutrients within the earthworm gut create a stressful environment that hinders the formation of stable bacterial mating pairs[62]. This is supported by a recent microcosm study showing that the earthworm gut maintains a nutrient-rich, but highly competitive microenvironment, where bacterial abundances are 2–3 times higher than in bulk soil and microbial turnover is extremely rapid, creating conditions unfavorable for conjugation[62]. Furthermore, harsh gut conditions, including the presence of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), disrupt this process. It has been demonstrated that certain α-helical AMPs prevent the formation of mating aggregates by disintegrating donor-cell pili and membrane receptors that are essential for conjugation[63]. Therefore, the aerobic environment created by earthworm activity is less conducive to triggering conjugation compared to anaerobic or hypoxic conditions.

More importantly, the propagation of ARGs is highly dependent on MGEs, such as plasmids, integrons, and transposons[30]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the abundance of MGEs (e.g., intI1 and intI2) and ARG abundance during vermicomposting[42,64−68]. Metabolic activities in the earthworm gut can significantly reduce the abundance of these key MGEs, thereby disrupting the ARG dissemination chain at the vector level[50]. The suppression is likely associated with antimicrobial peptides from the earthworm gut and with induced microbial competitive pressure, which can interfere with integrase activity or compromise the stability of MGEs, consequently reducing the risk of ARG horizontal transfer[59,60]. Notably, exogenous additives can work synergistically with earthworms to enhance this suppression process.

-

The highly efficient removal of ARGs during vermicomposting results from the intrinsic life activities of earthworms, the biocatalytic functions of their secreted mucus, and the synergistic effects of exogenous additives. Specifically, earthworm mucus acts as a natural "bio-reaction interface" and "signaling regulator" playing unique roles in modulating microbial metabolism and promoting pollutant degradation[17,69−73]. Furthermore, its combination with functional materials such as biochar and clay minerals can further optimize the substrate microenvironment and enhance the immobilization and transformation of pollutants[72,74−78]. This approach establishes a multi-dimensional synergistic system for ARG control, improving the overall treatment efficiency and stability.

Biocatalytic and regulatory functions of earthworm mucus

-

Earthworm epidermal mucus is a complex mixture composed of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, and various bioactive molecules. During composting, it functions as both a biocatalyst and a microecological modulator[69]. The functional components in the mucus enhance ARG removal through several synergistic mechanisms. First, certain active constituents directly suppress resistant bacteria[44]. Intestinal mucus can directly disrupt the cell membrane integrity of resistant bacteria or inhibit their proliferation, thereby showing selective inhibition against some key ARG host bacteria within the phylum Firmicutes[79]. The coelomic fluid promotes the generation of free radicals and extracellular enzymes that damage the pathogen or directly degrade ARGs[17]. Substances contained in mucus, such as antimicrobial peptides and lysozymes, can effectively inhibit or directly kill pathogenic bacteria, thereby reducing the population of ARG hosts[70,71,73]. Second, the mucus activates nutrients and guides microbial metabolism. It significantly increases the concentrations of dissolved carbon and nitrogen in the substrate, thereby supplying labile carbon and nitrogen sources that stimulate microbial growth and elevate overall metabolic activity, as evidenced by a marked increase in dehydrogenase activity[80]. This enhanced microbial activity accelerates the degradation of selective agents such as residual antibiotics, indirectly reducing the driving force for ARG maintenance. However, it is noteworthy that this nutrient-rich environment may also favor HGT by supporting a larger and more active bacterial population, which could increase opportunities for cell-to-cell contact[30]. Nevertheless, vermicomposting systems appear to exert a net suppressive effect on ARGs, as earthworm activity concurrently restructures the microbial community and suppresses MGEs, ultimately leading to a significant reduction in overall ARG abundance despite nutrient enrichment.

More importantly, earthworm mucus actively regulates microbial group behaviors by interfering with bacterial communication systems. Lin et al.[81] were quantified in a related mechanistic study, in which exposure to earthworm coelomic fluid (ECF) resulted in significant downregulation of 1,106 bacterial genes and upregulation of 4,353 others, profoundly disrupting metabolic pathways essential for bacterial coordination and conjugation[68]. This molecular intervention effectively suppresses the horizontal transfer of ARGs. The potency of earthworm-derived compounds is further highlighted by research on ECF, which directly damages bacterial structure, induces oxidative stress, and degrades resistance genes. Experimental results show that ECF treatment (1.0 mg/mL) reduces multidrug-resistant E. coli populations by 3.5 log units within 12 h, increases intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) by 4.2-fold, and degrades over 90% of extracellular ARGs via its potent DNase activity[68]. The DNase in ECF non-selectively cleaves both chromosomal and plasmid DNA, with removal rates for specific plasmid-borne ARGs (aphA, KanR, tetA) reaching 51.8%, 42.3%, and 35.0%, respectively[68]. Critically, these disruptive effects at the molecular level translate into profound ecological consequences. Network analysis reveals that earthworm processing significantly weakens the co-occurrence between ARGs and the bacterial community. The topological coefficients of the ARG co-occurrence network were generally lower in earthworm excretion product (EP) groups than in the control, indicating reduced network complexity and clustering[17]. Furthermore, the inverse correlations between the microbiome and resistome networks increased following EP application, suggesting a facilitated separation of manure-derived ARGs from their potential bacterial hosts[17]. This directly disrupts bacterial communication and genetic material, while ecologically decoupling ARGs from their hosts provides a robust barrier against the dissemination of antibiotic resistance.

Synergistic enhancement mechanisms with functional additives

-

The combination of vermicomposting with specific exogenous additives enhances ARG removal and system stability through the combined effects of physical adsorption, chemical passivation, and biological regulation.

Biochar, with its large specific surface area, pore structure, and surface functional groups, effectively adsorbs and immobilizes antibiotics and heavy metals, significantly reducing their selective pressure on microorganisms. The study by Yu et al. demonstrated that the combined use of earthworms and biochar promoted sludge degradation and transformed cadmium from an active form to an inert state[35]. This enhancement in environmental stability was accompanied by a reduction in the abundance of heavy-metal resistance genes and ARGs. Sanchez-Hernandez et al. combined earthworm mucus with biochar and observed a significant increase in carboxylesterase (CE) activity in soil burrow walls at 0–12 cm depth. This suggests that biochar, as a carrier, may improve the efficacy and persistence of the active components in the mucus[78].

Clay minerals, such as zeolite and diatomite, complement earthworm activity through their excellent ion-exchange capacity and adsorption properties. The addition of these mineral materials improves substrate structure, promotes earthworm growth and reproduction, and enhances compost quality and ARG removal efficiency. They contribute by passivating heavy metals, adsorbing organic pollutants, and optimizing microbial community structure[77]. Gong et al. found that the addition of zeolite, bamboo biochar, and diatomite stimulated earthworm growth. This addition also led to increased organic matter degradation efficiency, a higher humification level, greater product maturity, and ultimately, a higher ARG removal rate[74]. Studies have shown that combinations of zeolite with vermicompost or silicon fertilizer can effectively reduce the bioavailability of heavy metals in contaminated soil and the risk of ARG transmission in the soil-plant system.

In summary, the synergistic use of earthworm mucus and functional additives constructs a multi-level ARG containment system. This system operates across scales, from molecular regulation to ecosystem management. The synergy achieved through biocatalysis, physical immobilization, chemical transformation, and microbial community guidance provide a promising technological pathway for the significant reduction of ARGs and the safe, resourceful utilization of agricultural waste.

-

Despite its potential to control ARG pollution, scaling up vermicomposting from laboratory research to large-scale application poses multiple challenges that require systematic investigation.

Core application challenges

-

First, standardizing and adaptively processing parameters is a significant challenge. Different earthworm species (e.g., Eisenia fetida vs Pheretima guillelmi) have different ecological functions and tolerances. Certain species may perish or lose efficacy under high antibiotic loads, leading to complete process failure in heavily contaminated manure. Key operational parameters such as stocking density, initial feedstock C/N ratio, moisture, and temperature significantly influence microbial community succession and metabolic activity, which in turn affect ARG removal efficiency. Extreme temperatures or excessive moisture can severely impair earthworm activity, undermining the system's stability[34]. Furthermore, agricultural wastes from different sources (e.g., livestock manure, municipal sludge) vary considerably in their physicochemical properties, pollutant profiles, and microbial backgrounds. This variability means that a single process model is unlikely to be universally applicable. Contradictory outcomes have been reported under high residual antibiotic conditions, where selective pressure may even enrich specific ARG subtypes despite vermicomposting[12]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop tailored process control guidelines for specific waste types to achieve efficient and stable ARG removal.

Second, the long-term environmental risks of the final product, vermicompost, are not yet fully understood. When vermicompost is applied to farmland as an organic fertilizer, the long-term fate and ecological behavior of any residual ARGs and resistant bacteria within the soil-crop system is unclear. A critical question is whether these residual genes can be "reactivated" under new environmental stresses, such as the application of other antibiotics or heavy metals, and then spread via HGT among native soil microorganisms. This issue must be addressed through long-term field monitoring and realistic ecological risk assessment.

Finally, scaling up the process and intensifying its efficiency presents engineering bottlenecks. Current vermicomposting practices are mostly small-scale and batch operated. Outdoor systems are also vulnerable to climatic constraints, such as seasonal temperature fluctuations and rainfall patterns, which can lead to inconsistent performance across regions. Mature solutions for maintaining large earthworm populations, efficiently collecting bioactive components like mucus, and implementing automated process monitoring remain underdeveloped. Moreover, high-throughput reactor designs that ensure uniform substrate processing and prevent earthworm escape or mortality are still lacking. The core engineering challenge is to design continuous, modular vermicomposting reactor systems that allow precise control of key parameters and lower operational costs, thereby enabling the transition from small-scale treatment to industrial applications.

Future research directions and perspectives

-

Future research in this field should advance from phenomenological observation to mechanistic understanding, from empirical operation to model-based prediction, and from single-technology application to systematic integration.

Elucidating molecular-level regulatory networks through multi-omics integration. Advancing beyond correlative observations requires a deeper interrogation of the molecular dialogues between earthworms and microbes. Future research should employ integrated multi-omics approaches to construct a functional map of these interactions. Metatranscriptomics can reveal how earthworm activity alters the expression profiles of microbial communities, particularly genes associated with conjugation and stress response. Concurrently, metabolomic profiling of earthworm casts and mucus can identify the key signaling molecules that modulate these microbial behaviors. The application of emerging techniques, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, holds promise for resolving the functional heterogeneity of microbial populations within the earthworm gut, potentially identifying specific taxa actively engaged in horizontal gene transfer. This systematic deconstruction of the molecular interplay will clarify the precise mechanisms by which vermicomposting disrupts the maintenance and dissemination networks of ARGs.

Developing AI-driven predictive models for process optimization. Building on mechanistic insights, future work should create computational models that simulate ARG dynamics. A specific approach involves using machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest or Neural Networks) trained on multi-omics datasets to predict ARG removal efficiency based on operational parameters (e.g., feedstock properties, earthworm density, temperature). Such models could identify critical thresholds for process failure and optimize conditions for maximum ARG reduction. Furthermore, integrating these models with sensor-based real-time monitoring of physicochemical parameters could enable adaptive process control, representing a significant advancement beyond current empirical approaches.

Engineering integrated processes with emerging biotechnology. For complex waste scenarios where conventional vermicomposting has limitations, future efforts should focus on developing smart, multi-stage systems that synergistically integrate vermicomposting with complementary technologies. A promising strategy involves the bioaugmentation of vermicomposting systems with functionally engineered microorganisms. CRISPR-based gene editing could be used to design specialized bacterial strains that secrete enzymes to degrade extracellular ARGs, which would be introduced to target the residual gene pool. A coherent treatment train would begin with a thermal pretreatment phase to eliminate pathogens and decompose antibiotic residues, thereby reducing the initial selective pressure. This would be followed by the core vermicomposting stage enhanced with biochar, which simultaneously supports earthworm health and immobilizes various co-pollutants. The process would culminate in a dedicated curing or polishing stage, employing targeted biological agents such as ARG-degrading enzymes or specialized phages to neutralize any remaining resistance elements. This systematic integration of sequential treatment stages creates a comprehensive engineering framework for achieving complete ARG management across diverse and challenging waste streams.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Bowen Li: investigation, formal analysis, writing − original draft; Yuanye Zeng: conceptualization, writing − review and editing; Zhonghan Li: writing − review and editing; Simeng Cheng: data curation; Siyi Hu: writing − review and editing; Fengxia Yang: conceptualization, supervision, writing − review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition, validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study was financially supported by Tianjin Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 23JCYBJC00250), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42277033), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Grant No. Y2024QC28), and Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province of China (Grant No. 202401AT070304).

-

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

-

Vermicomposting achieves efficient and stable removal of ARGs from livestock manure.

Vermicomposting employs synergistic physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms to suppress ARGs.

Combining vermicomposting with additives creates a multi-dimensional system for enhanced performance.

Earthworm mucus disrupts bacterial communication, and inhibits gene transfer via signaling molecules.

Future challenges include standardizing the process and evaluating long-term environmental risks for large-scale use.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Bowen Li, Yuanye Zeng

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li B, Zeng Y, Li Z, Cheng S, Hu S, et al. 2025. Mechanisms and challenges in reducing antibiotic resistance genes by vermicomposting. Biocontaminant 1: e024 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0021

Mechanisms and challenges in reducing antibiotic resistance genes by vermicomposting

- Received: 19 October 2025

- Revised: 14 November 2025

- Accepted: 25 November 2025

- Published online: 22 December 2025

Abstract: The global spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) poses a significant public health threat, necessitating effective control during livestock manure recycling. Vermicomposting emerges as a sustainable technology that consistently removes ARGs more effectively than traditional composting. This review elucidates the multi-pathway mechanisms behind ARG mitigation, focusing on earthworms' role in improving physicochemical conditions, reshaping microbial communities through functional succession that suppresses typical ARG hosts and limits potential host bacteria, while concurrently inhibiting horizontal gene transfer by blocking mobile genetic elements. Synergistic effects of combining earthworm mucus with additives, such as biochar, are also discussed. Future research should focus on process standardization, environmental risk assessment, and scaling through multi-omics and predictive modeling to advance this promising technology.